Hussien Mohammed Jumaah

CABM

Lecturer in internal medicine

Mosul College of Medicine

2016

learning-topics

Respiratory disease

Normal breath sounds originate

mainly from the rapid

turbulent airflow in the larynx, trachea and main bronchi.

The acinus

is the gas exchange unit of the lung and

comprises branching respiratory bronchioles and clusters

of alveoli. Here the air makes close contact with the blood

in the pulmonary capillaries

(gas-to blood distance < 0.4 μm)

, and

oxygen uptake and CO

2

excretion occur.

The alveoli are lined

with flattened epithelial cells

(type I pneumocytes) and a few, more cuboidal,

type II pneumocytes. The latter produce surfactant, which is

a mixture of phospholipids that reduces surface tension

and counteracts the tendency of alveoli to collapse under

surface tension. Type II pneumocytes can divide to

reconstitute type I pneumocytes after lung injury.

The volume

of the lungs at the end of a

tidal (‘normal

’)

breath out is called the functional residual capacity (FRC).

At this volume, the

inward

elastic recoil of the lungs

(resulting from elastin fibres and surface tension in the alveolar lining fluid)

is balanced by the

resistance

of the chest wall

to inward

distortion from its resting shape, causing negative pressure

in the pleural space.

Elastin fibres allow the lung to be easily distended at

physiological lung volumes, but collagen fibres cause

increasing stiffness as full inflation is approached so that, in

health, the maximum inspiratory volume is limited by the

lung (rather than the chest wall).

With in the lung, the weight of tissue compresses the

dependent regions and distends the uppermost parts, so a

greater portion of an inhaled breath passes to the basal

regions, which also receive the greatest blood flow as a

result of gravity. Elastin fibres in alveolar walls maintain

small airway patency by radial traction on the airway walls.

Even in health, however, these small airways narrow during

expiration because they are surrounded by alveoli at higher

pressure, but are prevented from collapsing by radial

elastic traction. In emphysema, loss of

alveolar walls leaves the small airways unsupported,

and their collapse on expiration causes air trapping and

high end-expiratory volume

Control of breathing

The respiratory motor neurons in the posterior medulla are

the origin of the respiratory cycle. Their activity is

modulated by multiple external inputs :

• Central chemoreceptors

in the ventrolateral medulla

sense the pH of the CSF and indirectly stimulated by a rise

in arterial PCO

2

.

• The carotid bodies

sense hypoxaemia but are mainly

activated by arterial PO

2

values below 8 Kpa (60 mmHg)

also sensitised to hypoxia by raised arterial PCO

2

.

• Muscle spindles

in the respiratory muscles sense changes in

mechanical load.

• Vagal sensory fibres

from the lung may be stimulated by stretch,

by inhaled toxins or by disease processes in the interstitium.

• Cortical

(volitional) and

limbic

(emotional) influences can override

the automatic control of breathing.

The pulmonary circulation in health operates at low

pressure

(24/9 mmHg),

can accommodate large increases in

flow with minimal rise in pressure, such as during exercise.

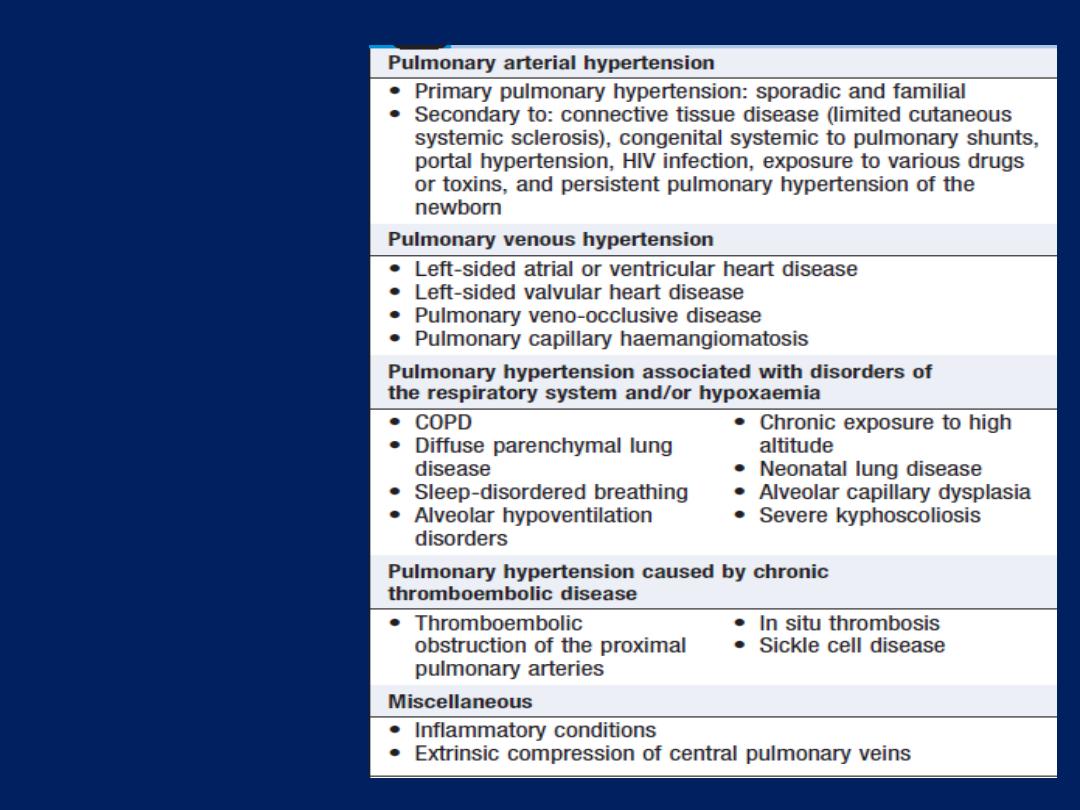

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) occurs when vessels are

destroyed by emphysema, obstructed by thrombus, involved

in interstitial inflammation or thickened by pulmonary

vascular disease. The RV responds by hypertrophy,

with right

axis deviation and P pulmonale on the ECG

. PH with hypoxia and

hypercapnia is associated with salt and water retention

(‘cor pulmonale’), with elevation JVP and peripheral

oedema. This is thought to result mainly from a failure of

the hypoxic and hypercapnic kidney to excrete sufficient

salt and water. hypoxia constricts pulmonary arterioles

and airway CO

2

dilates bronchi, helping to maintain good

regional matching of ventilation and perfusion.

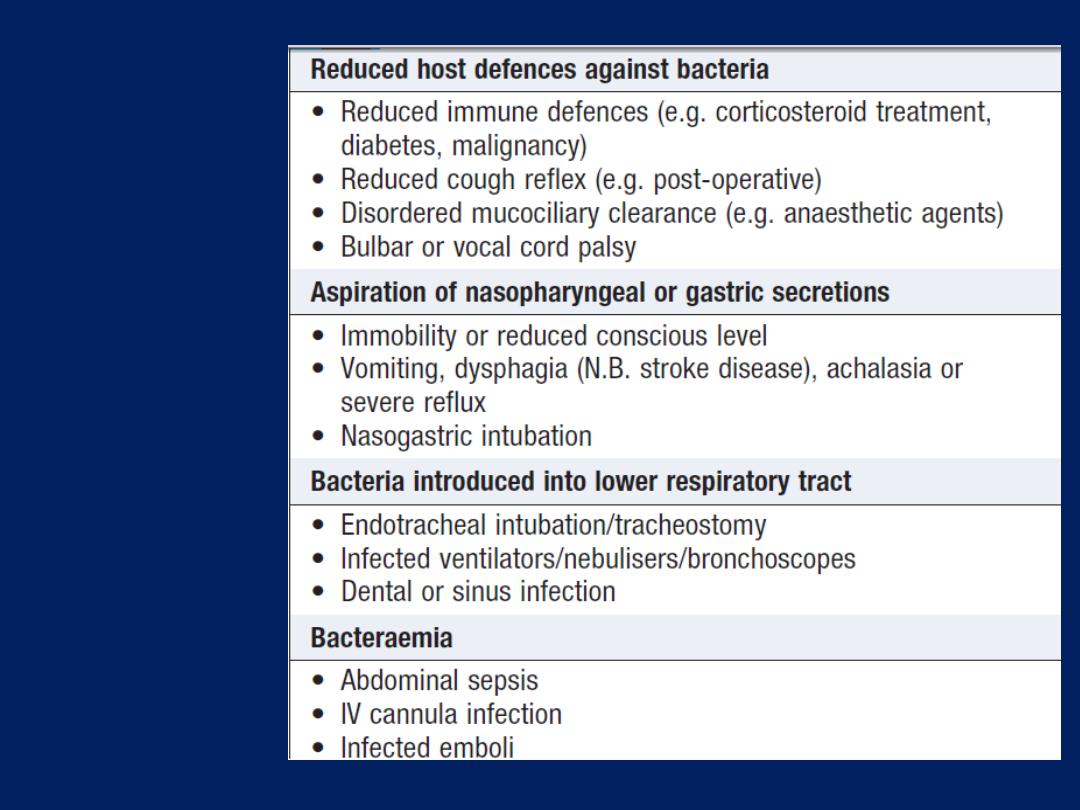

Lung defences

Upper airway defences

Large airborne particles are trapped by nasal

hairs

, and

smaller particles settling on the mucosa are cleared

towards the oropharynx by the columnar

ciliated

epithelium which covers the turbinates and septum .

During cough, expiratory

muscle

effort against a closed

glottis results in high intrathoracic pressure, which is

then released explosively.

The flexible posterior

tracheal wall

is pushed inwards by

the high surrounding pressure, which reduces tracheal

cross-section and thus maximises the airspeed to achieve

effective expectoration.

The larynx also acts as a

sphincter

, protecting the

airway during swallowing and vomiting.

Lower airway defences

The sterility, are maintained by cooperation between the

innate and adaptive immune responses .

The innate

response is characterised by a number of defence

mechanisms. Inhaled matter is trapped in airway mucus

and cleared by the mucociliary escalator. Cigarette smoke

increases mucus secretion but reduces mucociliary clearance

and predisposes towards lower respiratory tract infections.

Defective mucociliary transport is also a feature of

Kartagener’s, Young’s syndrome , which are characterised

by repeated sino-pulmonary infections and bronchiectasis.

Airway secretions contain antimicrobial peptides

(defensins ,IgA and

lysozyme),

antiproteinases and antioxidants, assist with the

opsonisation and killing of bacteria, and the regulation of the

powerful proteolytic enzymes

secreted by inflammatory cells.

In particular, α

1

-antiproteinase (A1Pi) regulates

neutrophil elastase, and deficiency of this may be

associated with premature emphysema. Macrophages

engulf microbes, organic dusts. They are unable to digest

inorganic agents, such as asbestos or silica, which lead to

their death and the release of powerful proteolytic

enzymes that cause parenchymal damage. Neutrophil

numbers in the airway are low, but the pulmonary

circulation contains a marginated pool that may be

recruited rapidly in response to bacterial infection. This

may explain the prominence of lung injury in sepsis

syndromes and trauma.

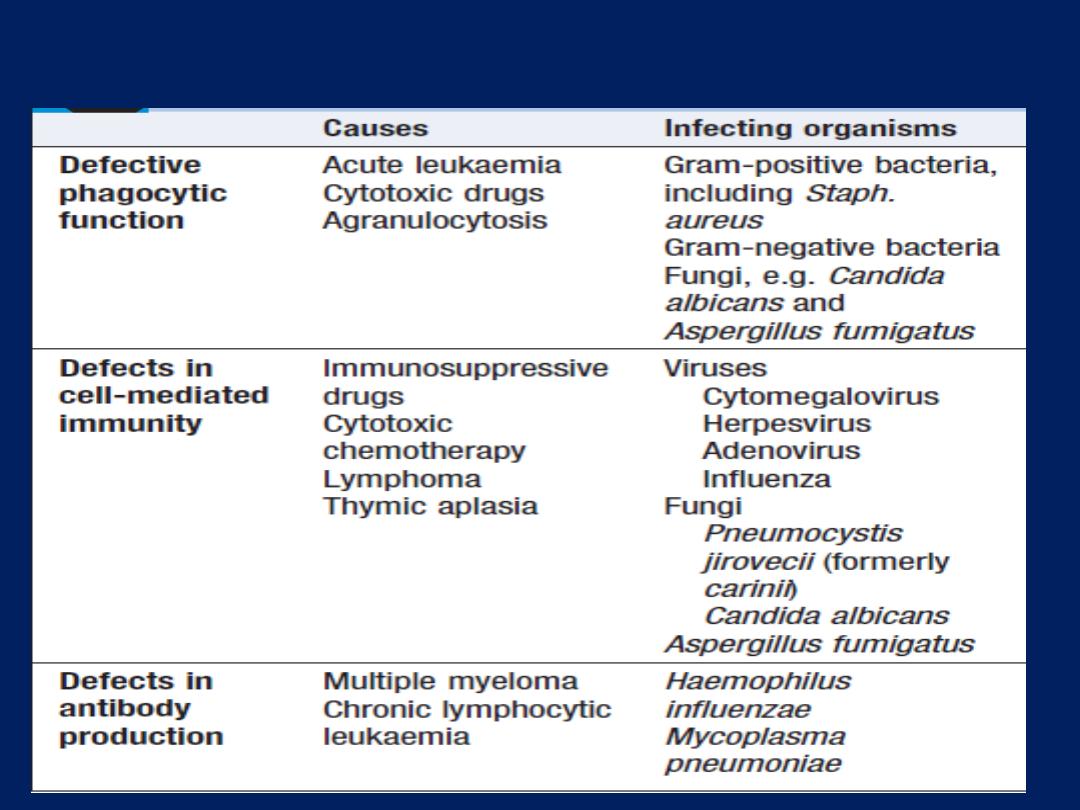

Adaptive immunity

is

characterised by the specificity of the response and the

development of memory. Lung dendritic cells facilitate

antigen presentation to T and B lymphocytes.

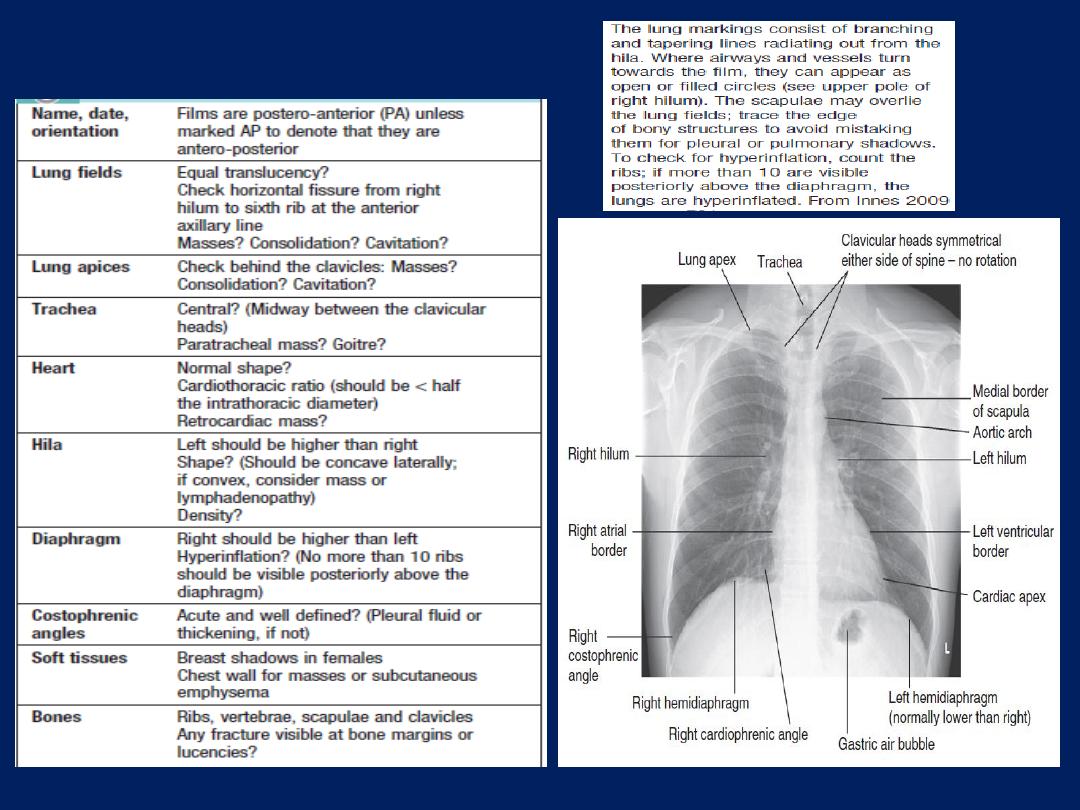

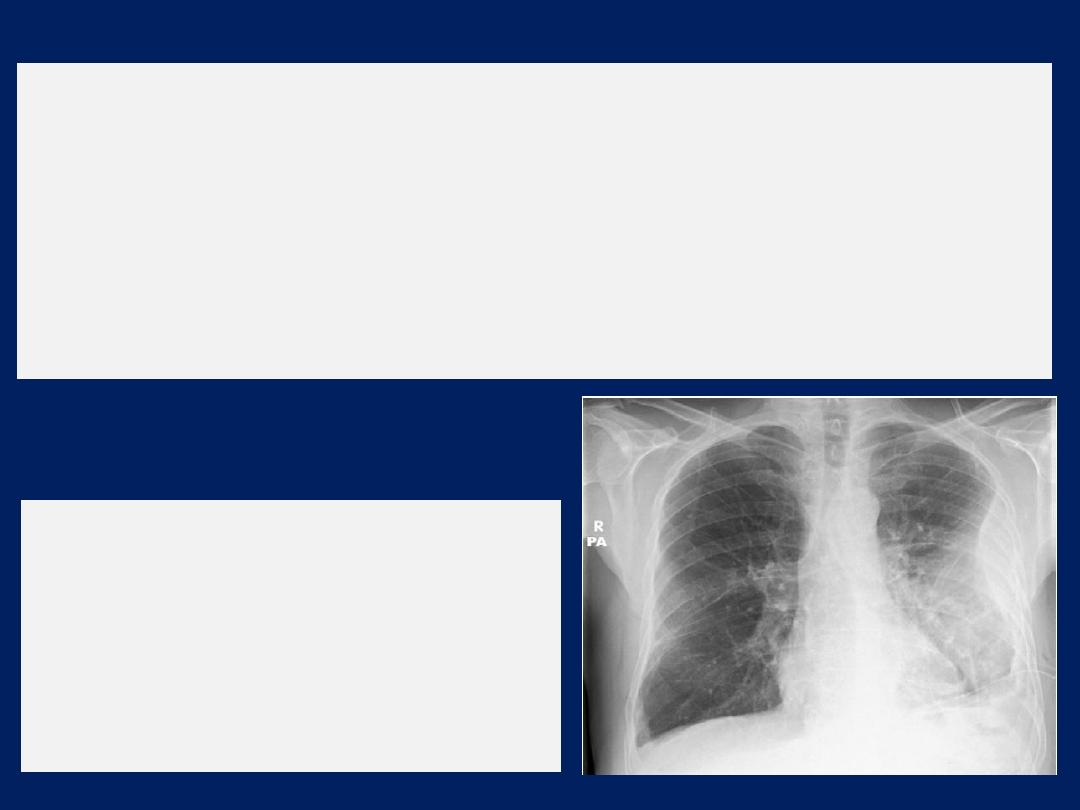

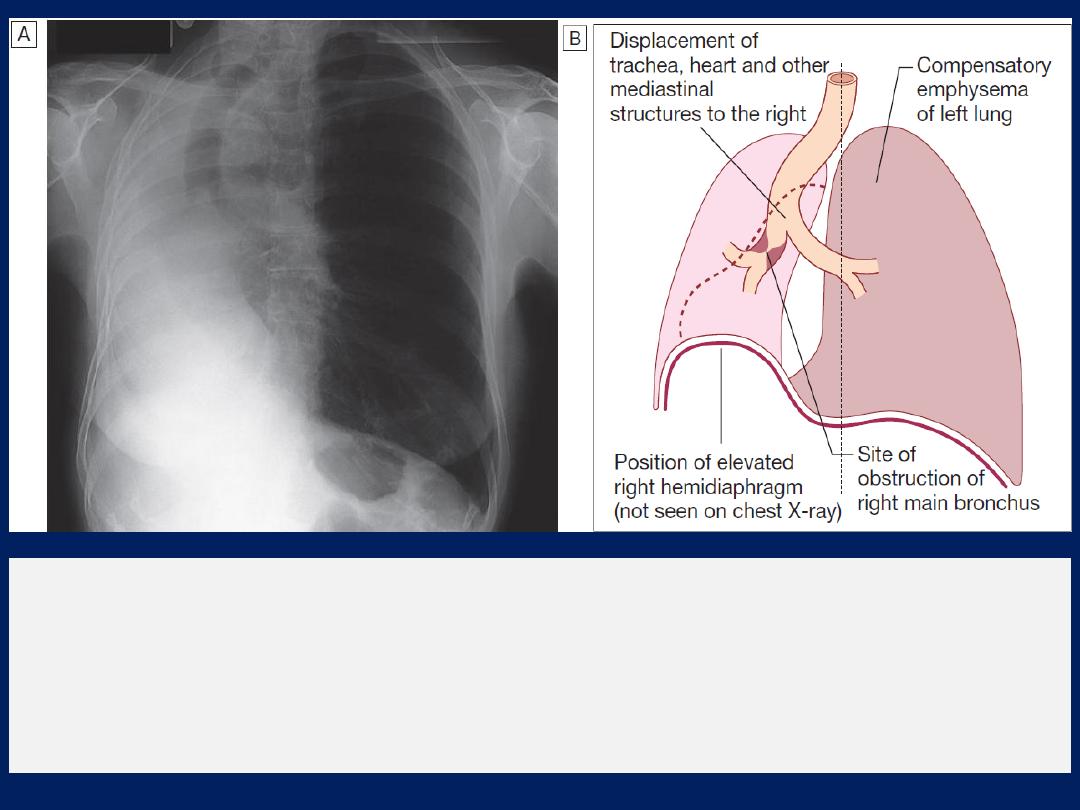

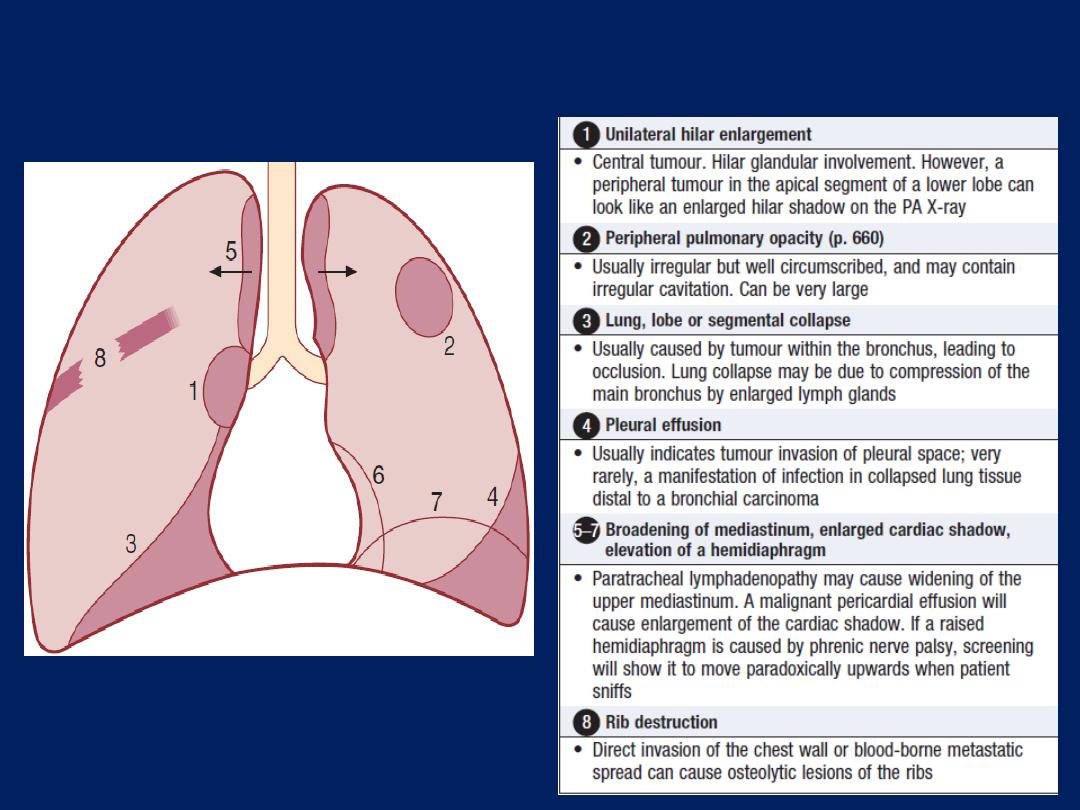

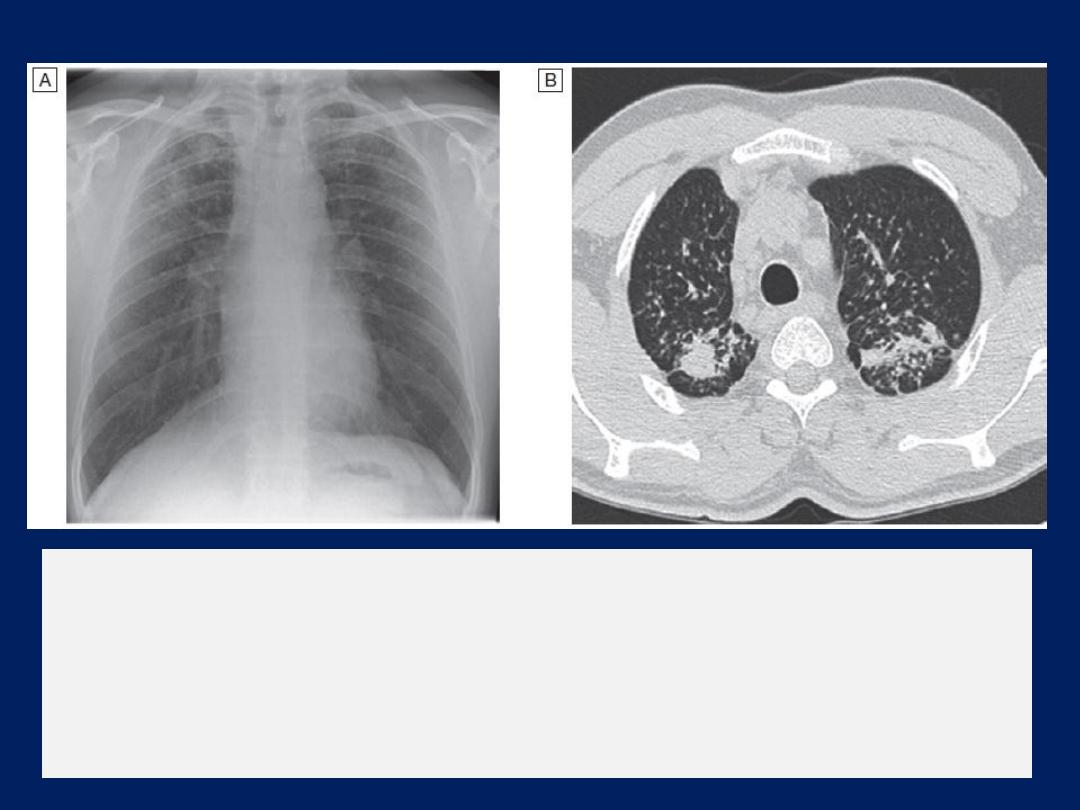

The ‘plain’ chest X-ray

A postero-anterior (PA) film provides information on the

lung , heart, mediastinum, vascular structures and thoracic

cage. Additional information may be obtained from a

lateral

film, particularly if pathology is suspected

behind

the heart shadow or deep in the diaphragmatic sulci. Air

bronchogram means that proximal bronchi are patent.

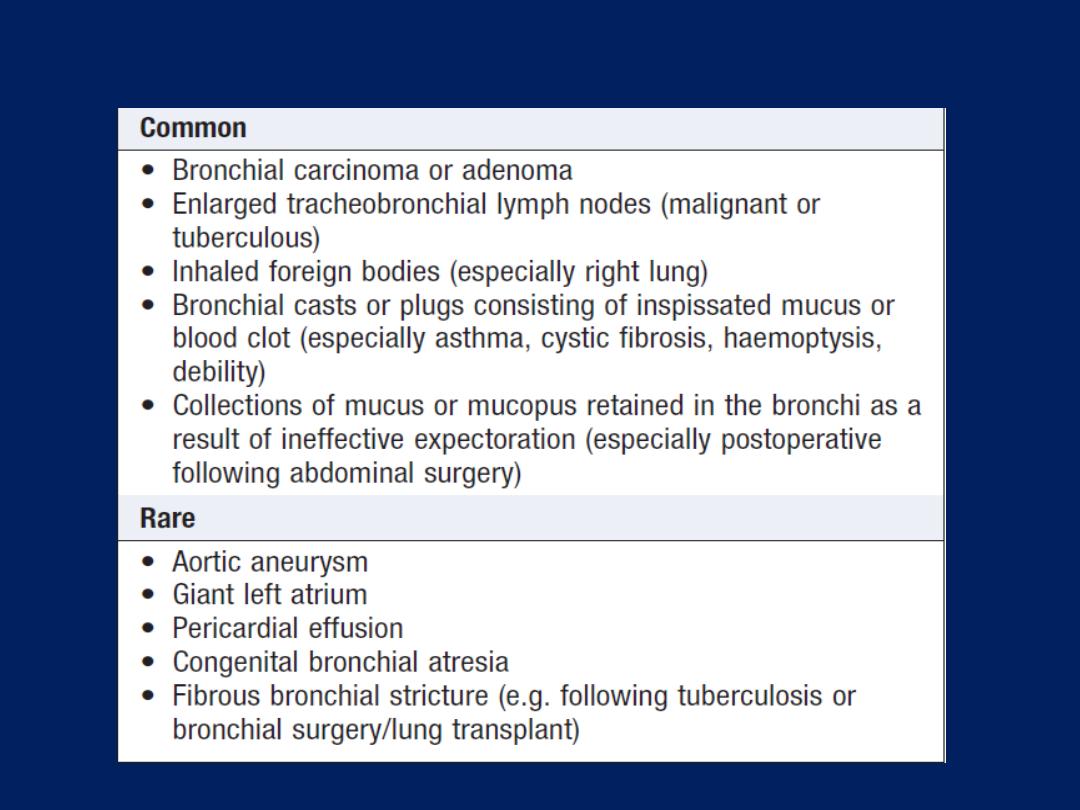

Collapse (implying obstruction of the lobar bronchus) is

accompanied by loss of volume and displacement of the

mediastinum towards the affected side .

The presence of

ring shadows

(thickened bronchi seen end-

on),

tramline shadows

(thickened bronchi seen side-on) or

tubular shadows

(bronchi filled with secretions) suggests

bronchiectasis

,

but

CT is a much more sensitive.

How to interpret CX-ray

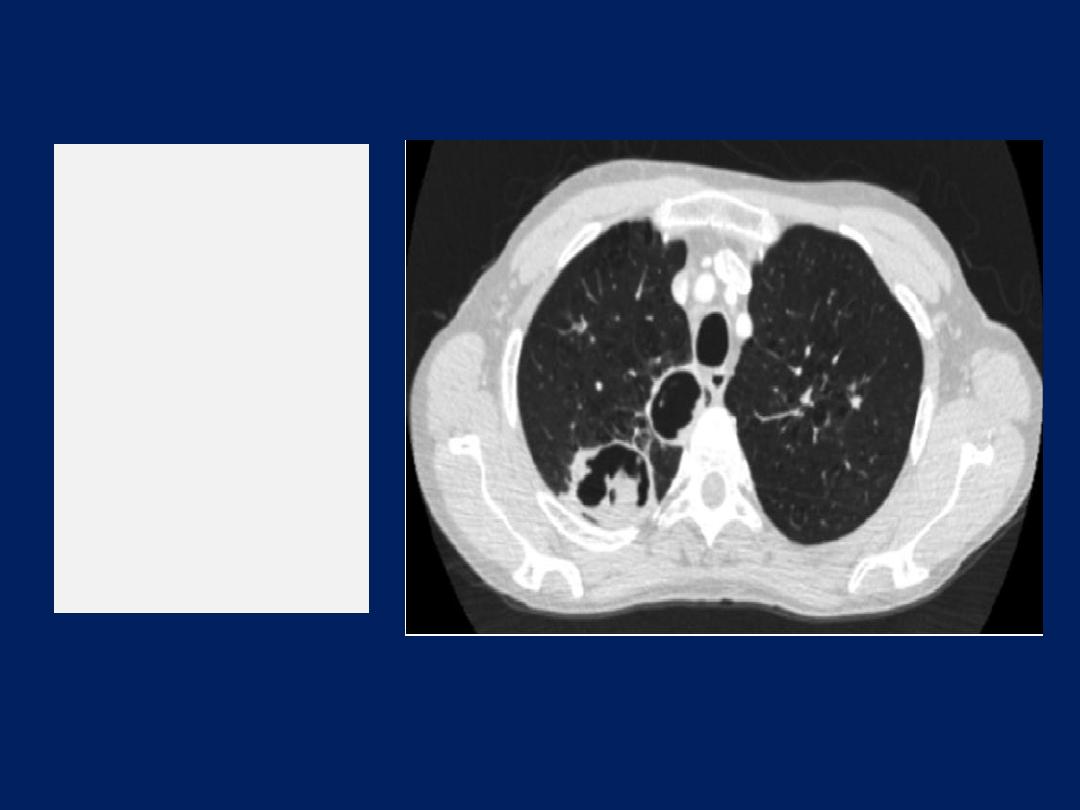

Computed tomography (CT)

CT and High-resolution CT (HRCT) provides images of the

pulmonary parenchyma , identifying bronchiectasis and

assessing type and extent of emphysema , mediastinum,

pleura and bony structures. CT is superior to chest

radiography in determining the position and size of a

pulmonary lesion and whether calcification or cavitation is

present. It is now routinely used in the assessment of patients

with suspected lung cancer and facilitates guided

percutaneous needle biopsy.

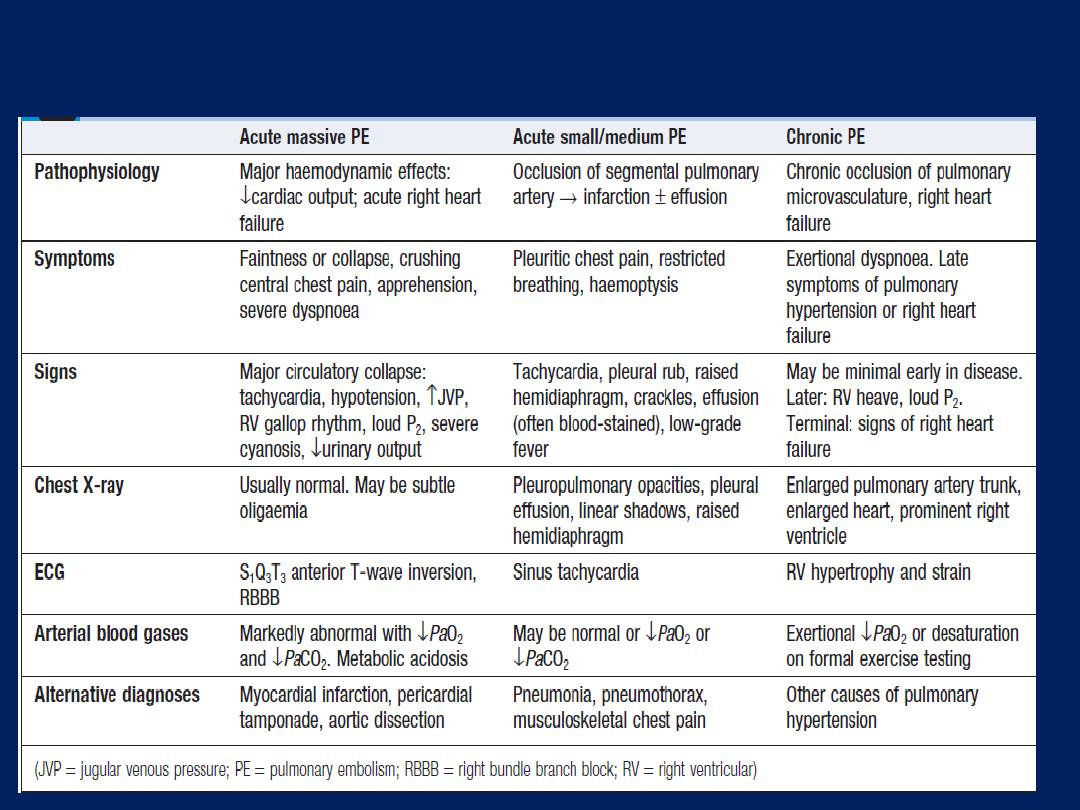

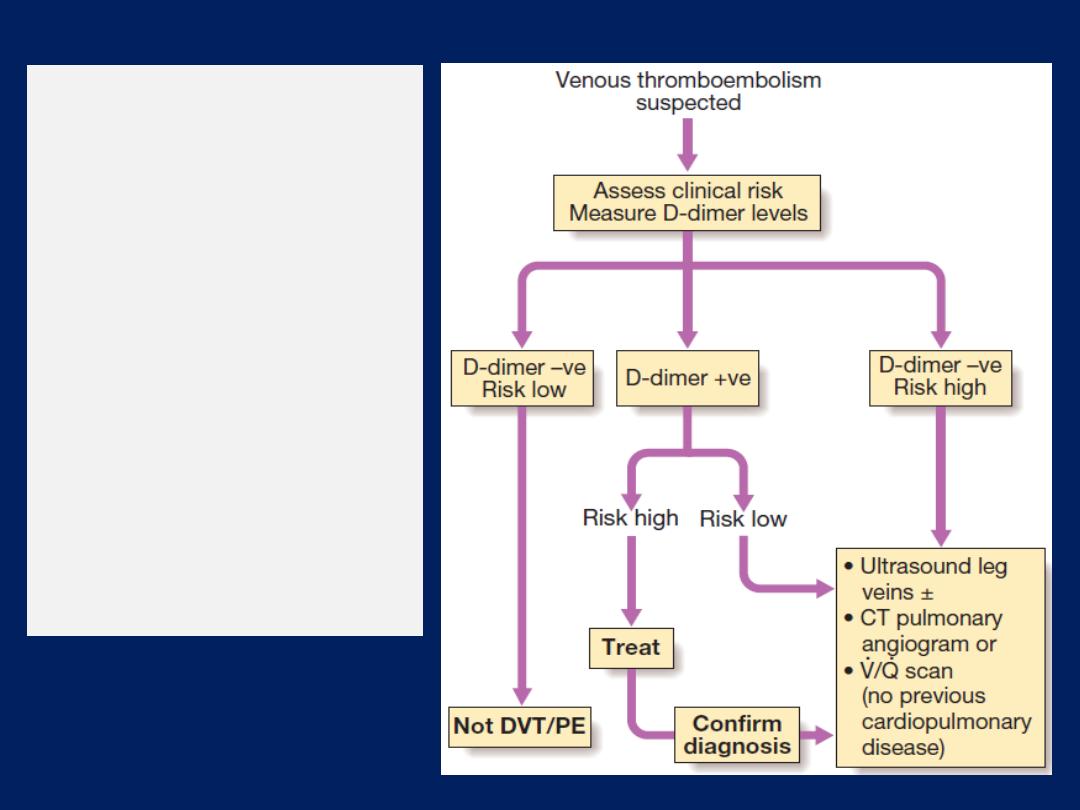

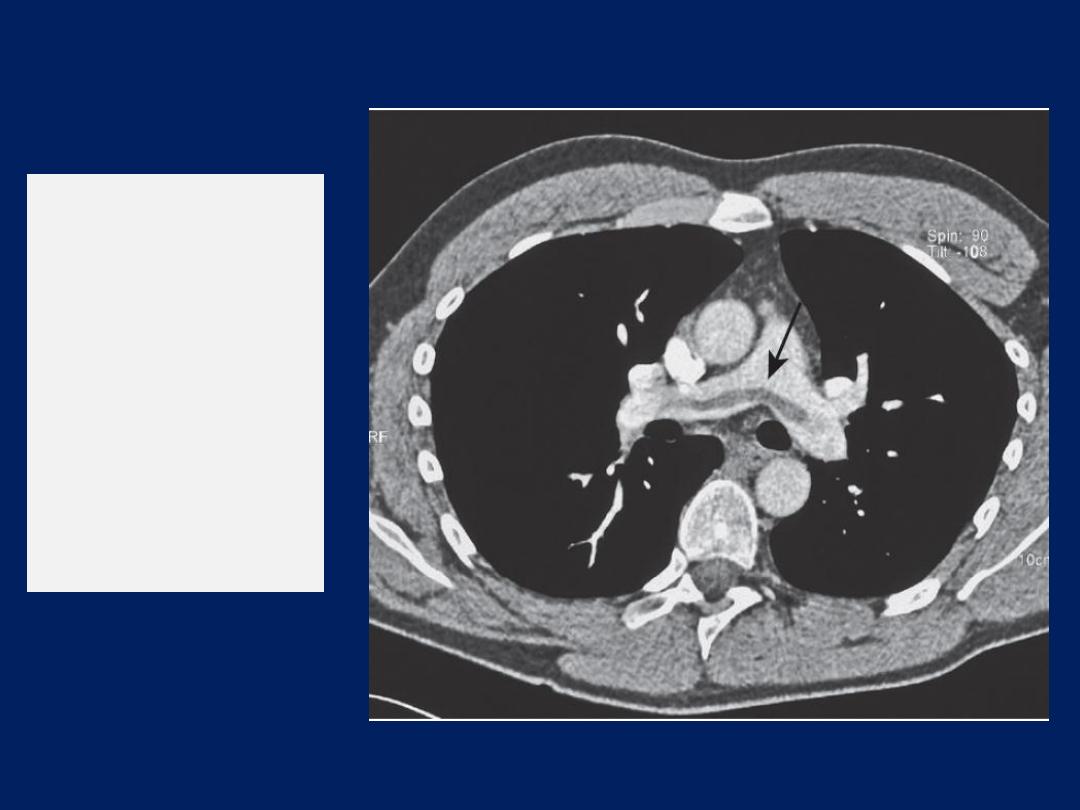

CT pulmonary angiography

(CTPA) the investigation

of

choice in

the diagnosis of pulmonaryTE , has largely

replaced the radioisotope-based ventilation–perfusion

scan, although the latter continues to provide useful

information in the pre-operative lung resection.

In pulmonary hypertension,

Doppler

assessment of tricuspid

regurgitant jets allows accurate non-invasive measurement

of pulmonary artery pressure in most cases.

Right heart

cath

used in the investigation of pulmonary hypertension.

Positron emission tomography (PET)

is useful in the

investigation of pulmonary nodules, mediastinal nodes and

metastatic disease in lung cancer. The negative predictive

value is high; however, the positive predictive value is poor.

Ultrasound

Used to assess the pleural space for pleural fluid. It also

allows direct visualisation of the diaphragm and solid

organs such as the liver, spleen and kidneys, thereby

allowing safe pleural aspiration, biopsy and intercostal

chest drain insertion, also be used to guide needle biopsy

of superficial lymph node or chest wall masses.

Endoscopic examination

Laryngoscopy

The larynx may be inspected directly with a fibreoptic

laryngoscope. Left-sided lung tumours may involve the left

recurrent laryngeal nerve, paralysing the left vocal cord

and leading to a hoarse voice and a ‘bovine’ cough.

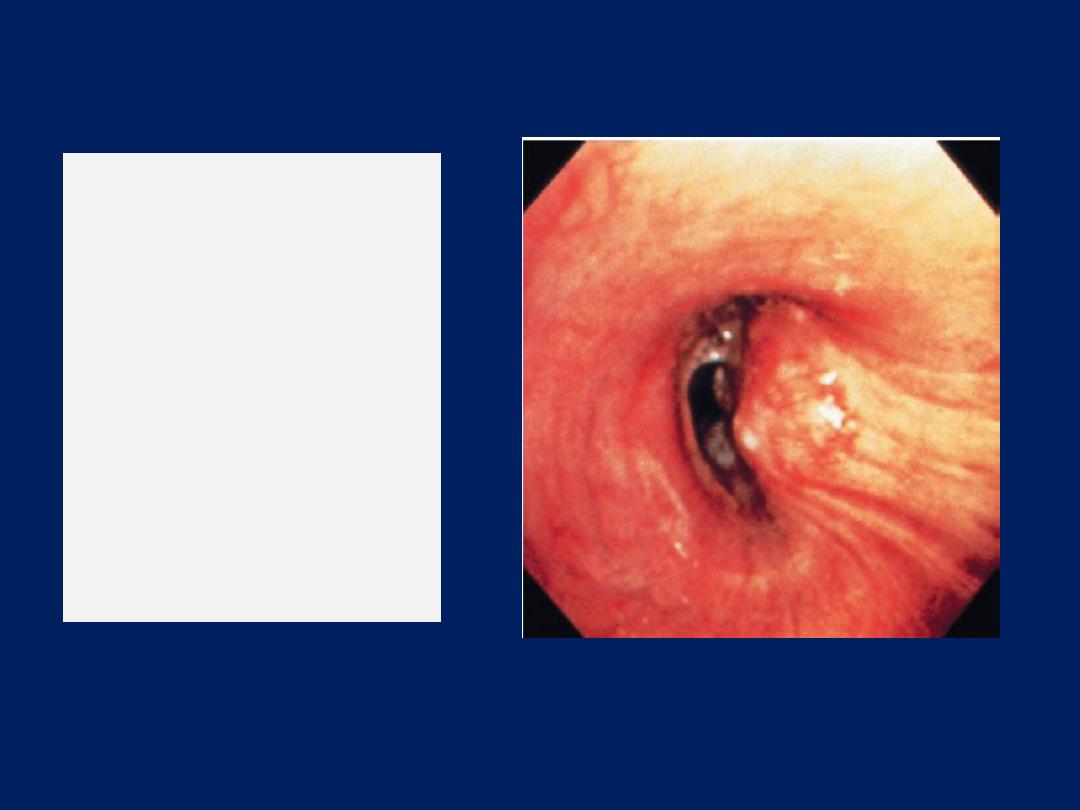

Bronchoscopy

The trachea and the first 3–4 generations of bronchi may

be inspected using a flexible bronchoscope. Flexible

bronchoscopy is usually performed under local anaesthesia

with sedation, on an outpatient basis. Abnormal tissue in the

bronchial lumen or wall can be biopsied, and bronchial

brushings, washings or aspirates can be taken for

cytological or bacteriological examination.

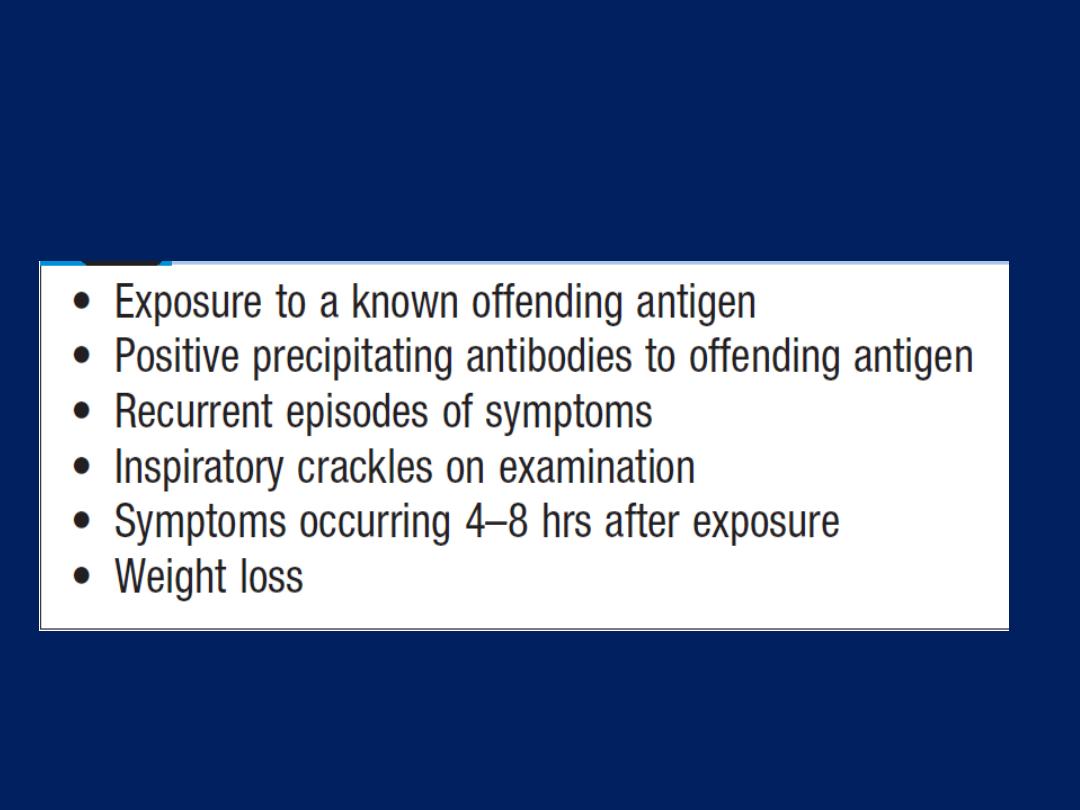

Small biopsy specimens of lung tissue, taken by forceps

passed through the bronchial wall (transbronchial

biopsies), may be helpful in the diagnosis of

bronchocentric disorders such as sarcoid, hypersensitivity

pneumonitis and malignancy, but are generally too small

to be of diagnostic value in other diffuse parenchymal

pulmonary disease . Transbronchial needle aspiration

(TBNA) may be used to sample mediastinal lymph nodes

and to stage lung cancer.

Rigid bronchoscopy

requires general anaesthesia and is

reserved for specific situations, such as massive

haemoptysis or removal of foreign bodies .

Endobronchial laser therapy and endobronchial stenting

may be easier with rigid bronchoscopy.

Assessment of the mediastinum

The sampling of mediastinal lymph nodes is essential in

the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer and may

confirm the diagnosis of tuberculosis or sarcoidosis.

Endobronchial ultrasound

(EBUS), using a specialised

bronchoscope, allows directed needle aspiration from

peribronchial nodes. Lymph nodes down to the main

carina can also be sampled using a

mediastinoscope

passed through a small incision at the suprasternal notch

under general anaesthetic.

Lymph nodes in the lower mediastinum may be

biopsied via the oesophagus using

endoscopic

ultrasound

(EUS), an oesophageal endoscope equipped

with an ultrasound transducer and biopsy needle.

Investigation of pleural disease

Core biopsy

of the pleura, guided by either

ultrasound

or CT, has largely replaced the traditional ‘blind’ method

of pleural biopsy using an Abram’s needle.

Thoracoscopy

, which involves the insertion of an

endoscope through the chest wall, facilitates biopsy

under direct vision.

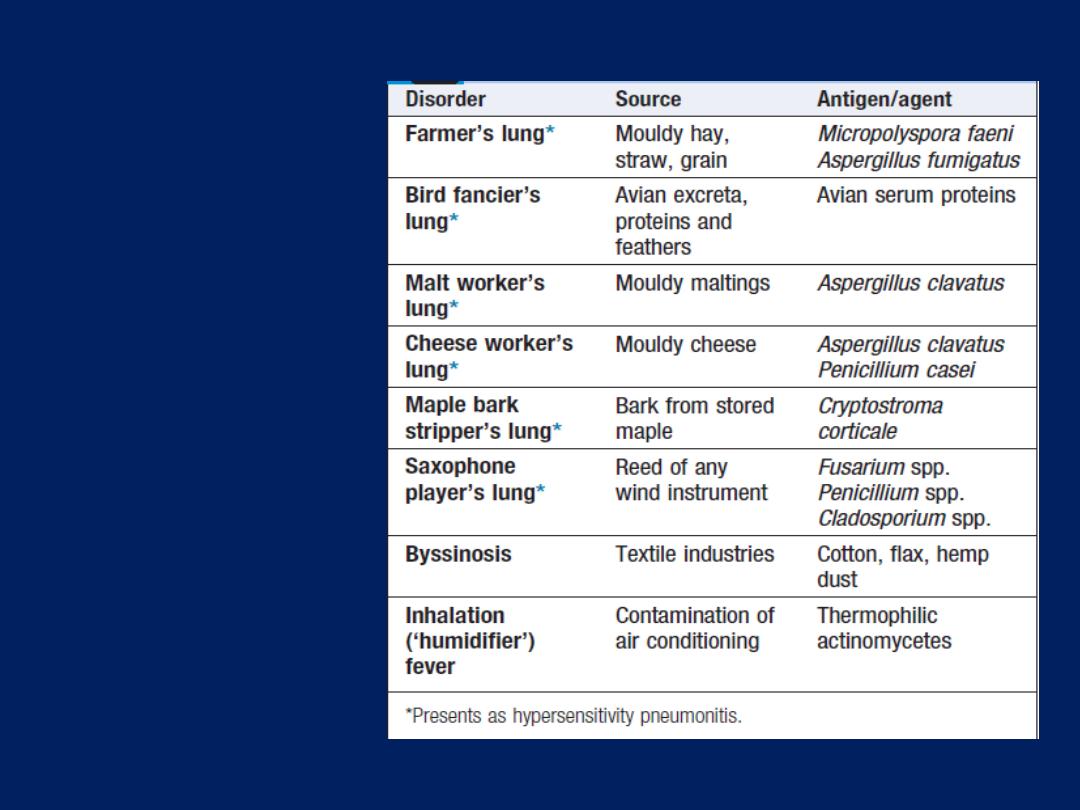

Immunological and serological tests

The presence of pneumococcal antigen (revealed by

counter- immunoelectrophoresis) in sputum, blood or

urine may be of diagnostic importance in pneumonia.

Influenza viruses can be detected in throat swab

samples by fluorescent antibody techniques.

In blood, high or rising antibody titres to specific

organisms (Legionella, Mycoplasma, Chlamydia or viruses)

may eventually clinch a diagnosis suspected on clinical

grounds but early diagnosis of Legionella is best done by

urine antigen testing. Precipitating antibodies may indicate

a reaction to fungi such as Aspergillus or to antigens

involved in hypersensitivity pneumonitis . Total levels of IgE,

and levels of IgE directed against specific antigens, can be

useful in assessing the contribution of allergy to respiratory

disease.

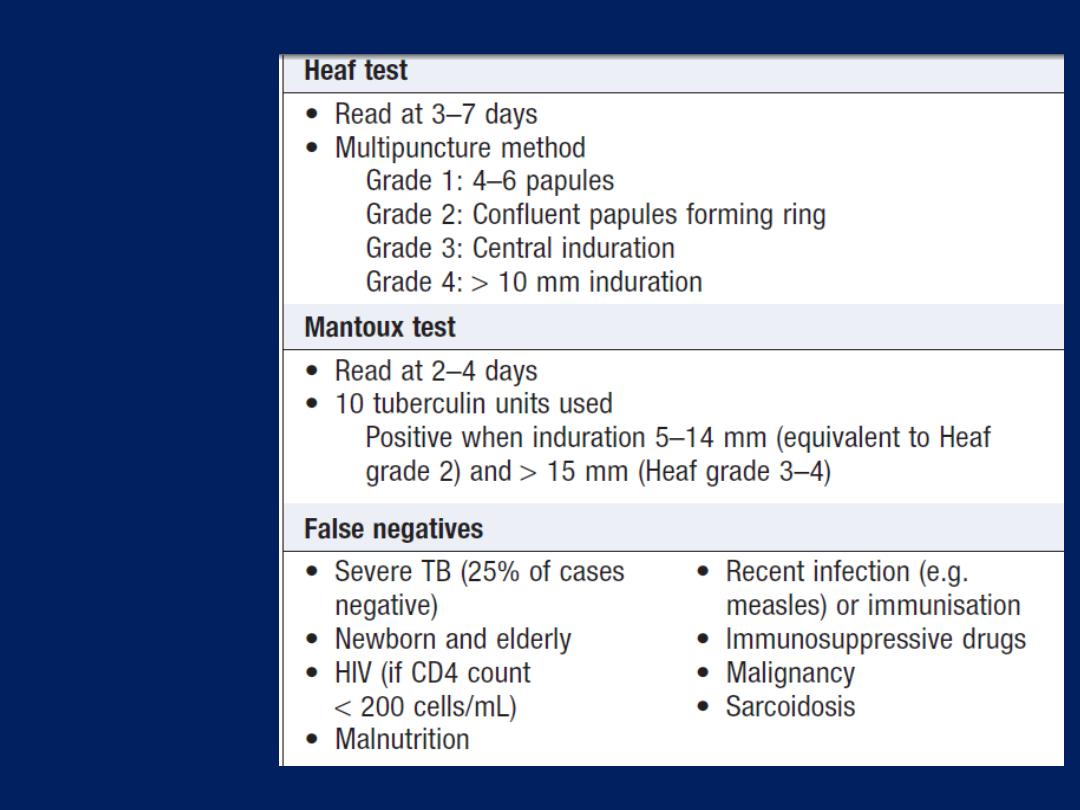

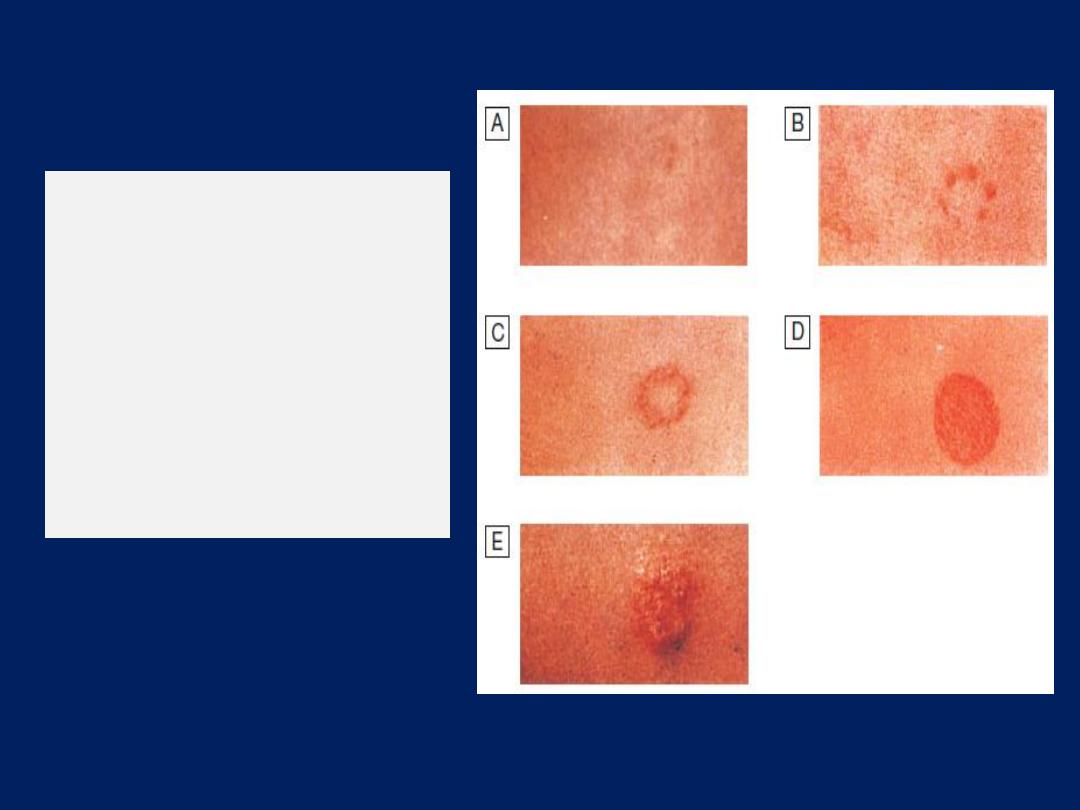

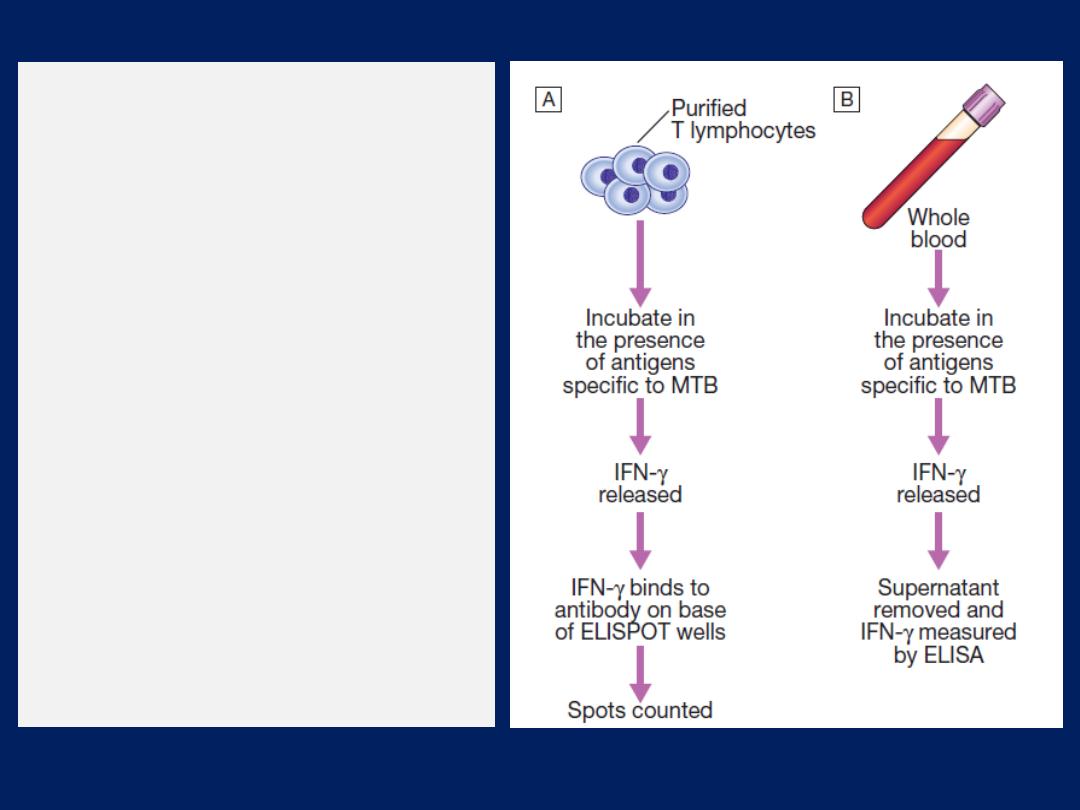

Skin tests

The tuberculin test may be of value in the diagnosis of

tuberculosis. Skin hypersensitivity tests are useful in the

investigation of allergic diseases

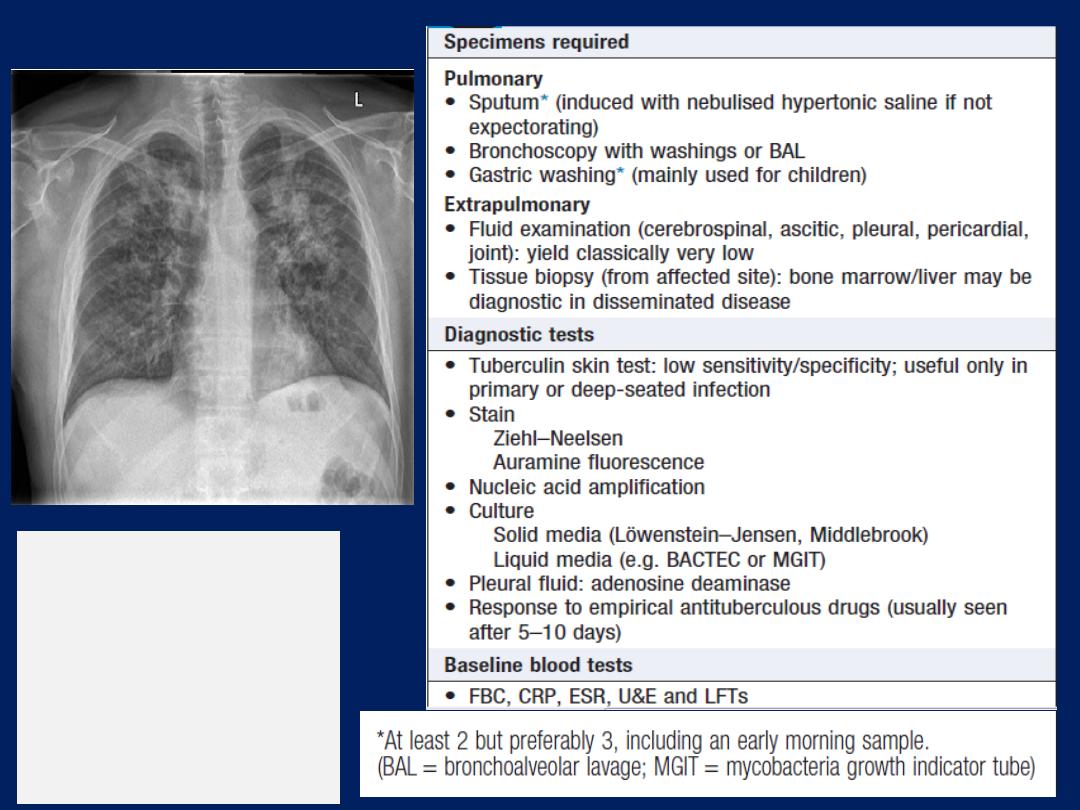

Microbiological investigations

Sputum, pleural fluid, throat swabs, blood, and bronchial

washings and aspirates can be examined for bacteria,

fungi and viruses. The use of hypertonic saline to induce

expectoration of sputum is useful in facilitating the

collection of specimens for microbiology.

Histopathology and cytology

Biopsies of pleura, lymph node or lung often allows a

‘tissue diagnosis’ to be made, in suspected malignancy or

interstitial lung disease. Important causative organisms,

such as M. tuberculosis, Pneumocystis jirovecii or fungi, may

be identified in bronchial washings, brushings or

transbronchial biopsies.

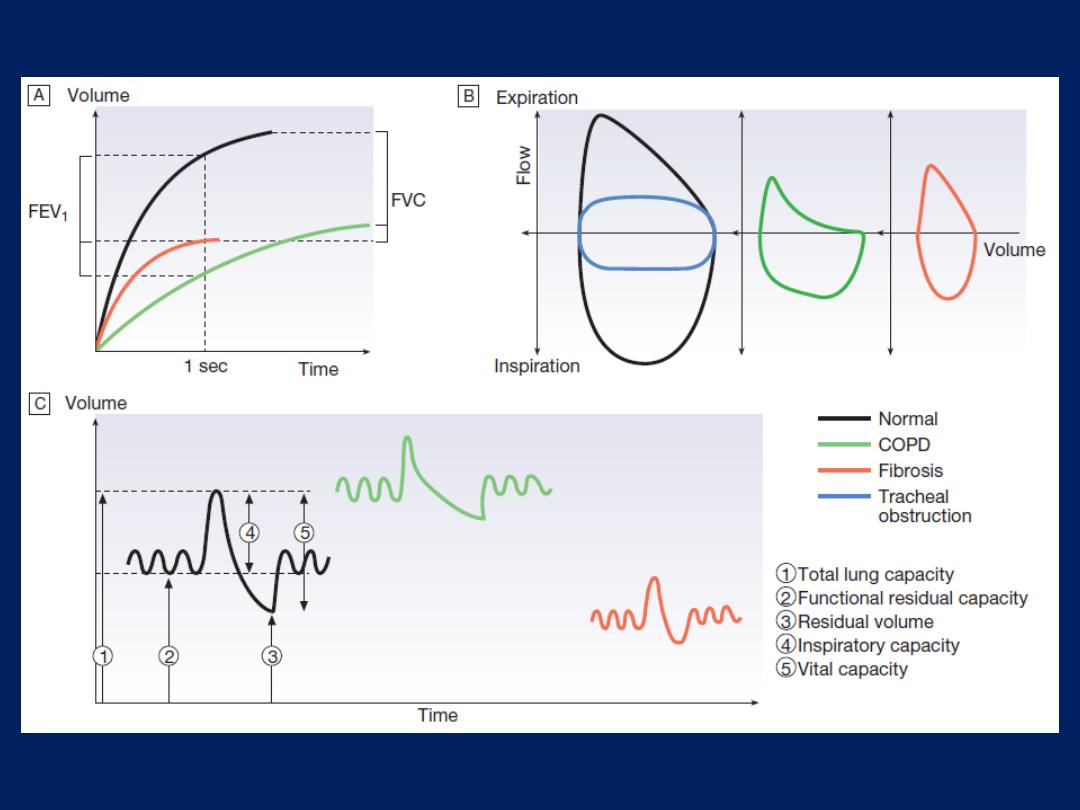

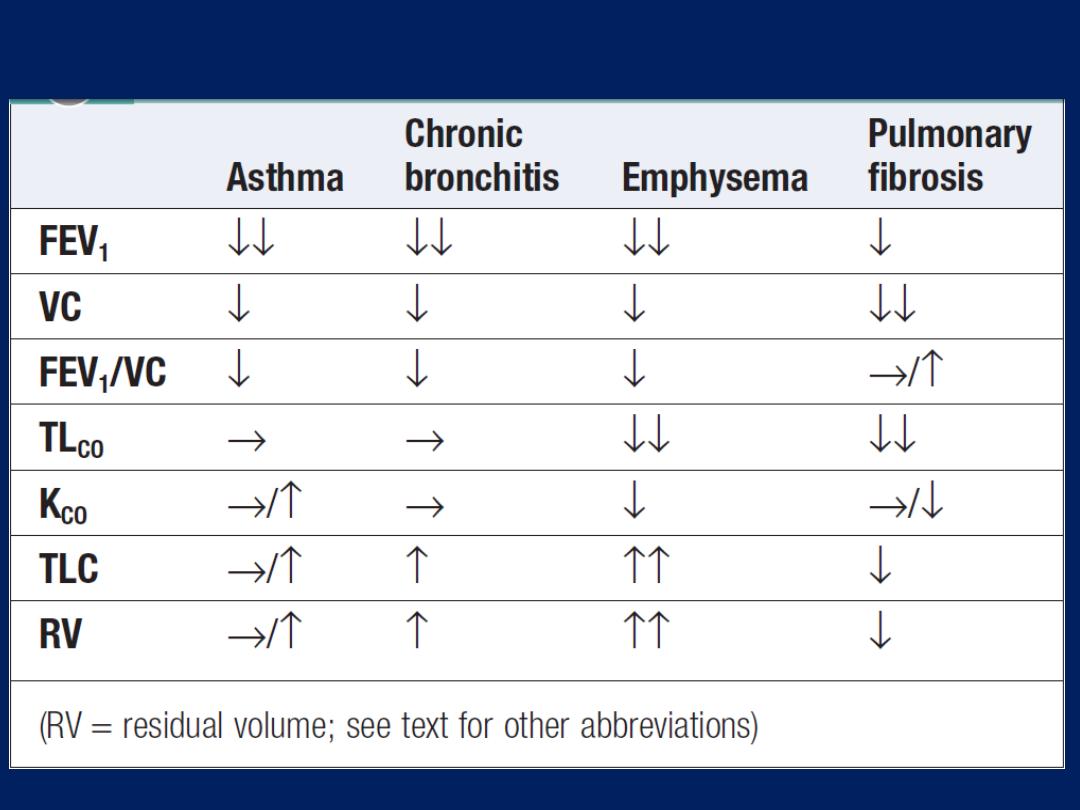

Respiratory function testing

Used to aid diagnosis, assess functional impairment, and monitor

treatment or progression of disease. Airway narrowing, lung

volume and gas exchange capacity are quantified and compared

with normal values adjusted for age, gender, height and ethnic

origin. In diseases characterised by airway narrowing (e.g.

asthma, bronchitis and emphysema), maximum expiratory flow is

limited by dynamic compression of small intrathoracic airways,

some of which may close completely during expiration, limiting

the volume that can be expired (‘

obstructive

’ defect).

Hyperinflation of the chest results, and can become extreme if

elastic recoil is also lost due to parenchymal destruction, as in

emphysema.

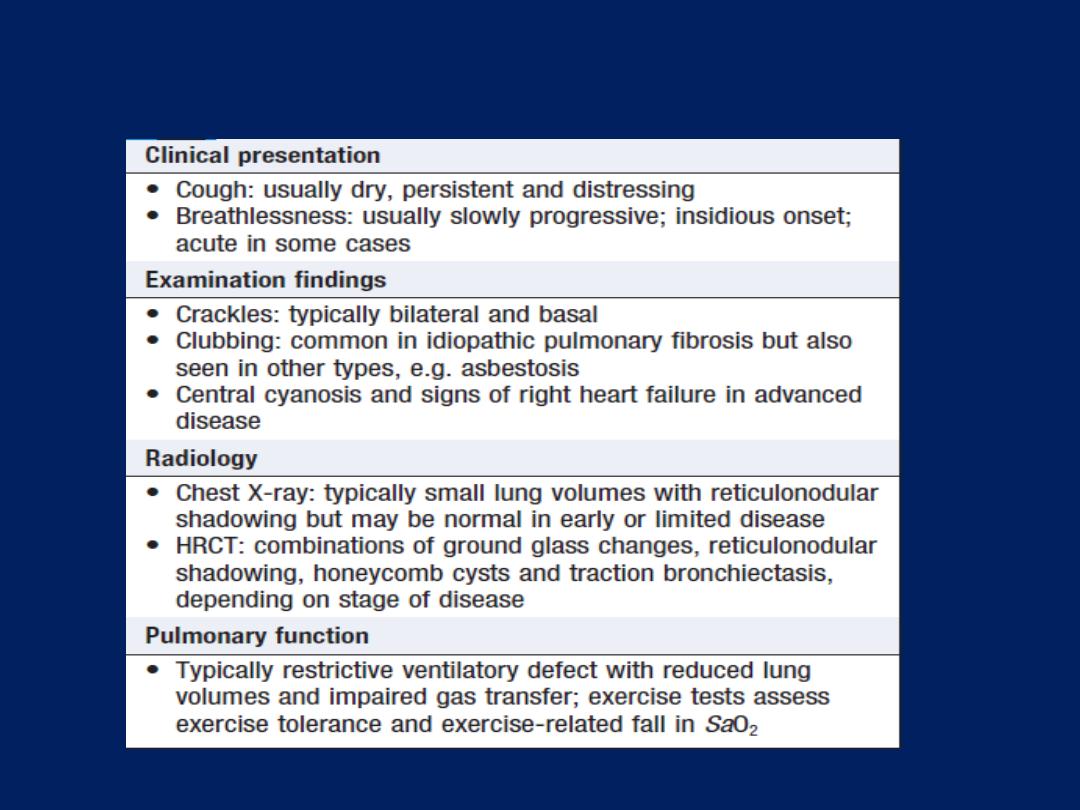

In contrast

, diseases that cause interstitial

inflammation and/or fibrosis lead to

progressive loss of lung

volume

(‘

restrictive

’ defect) with normal expiratory flow rates.

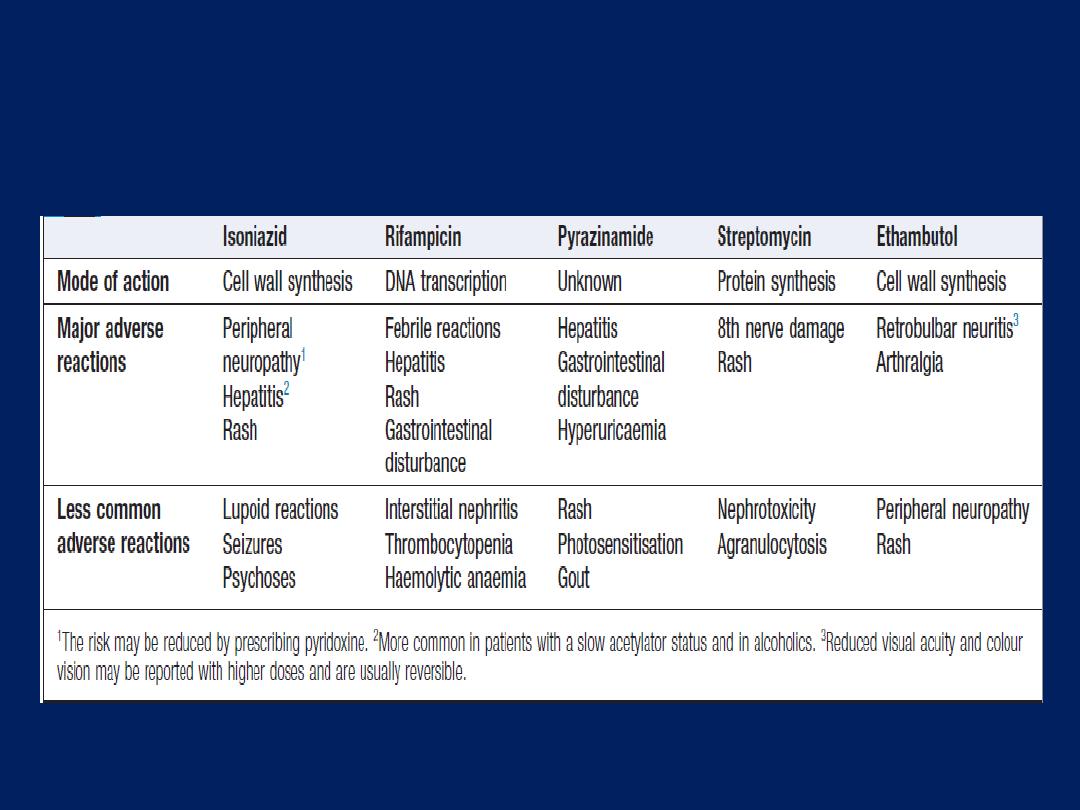

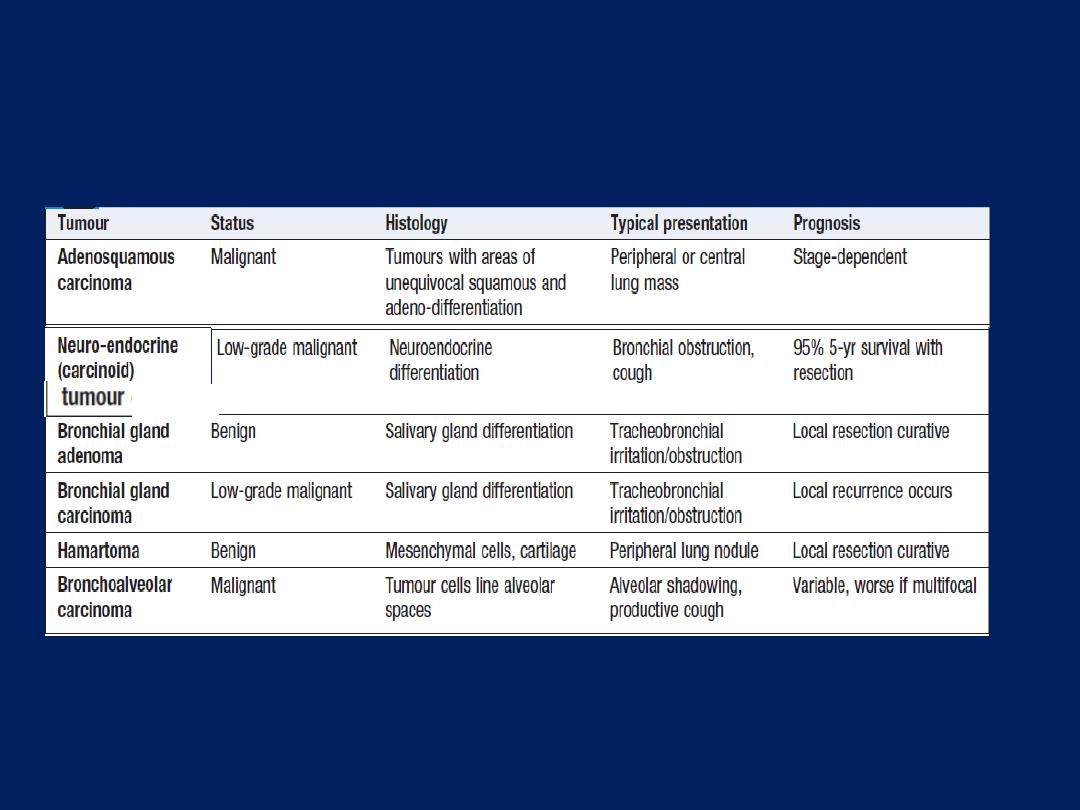

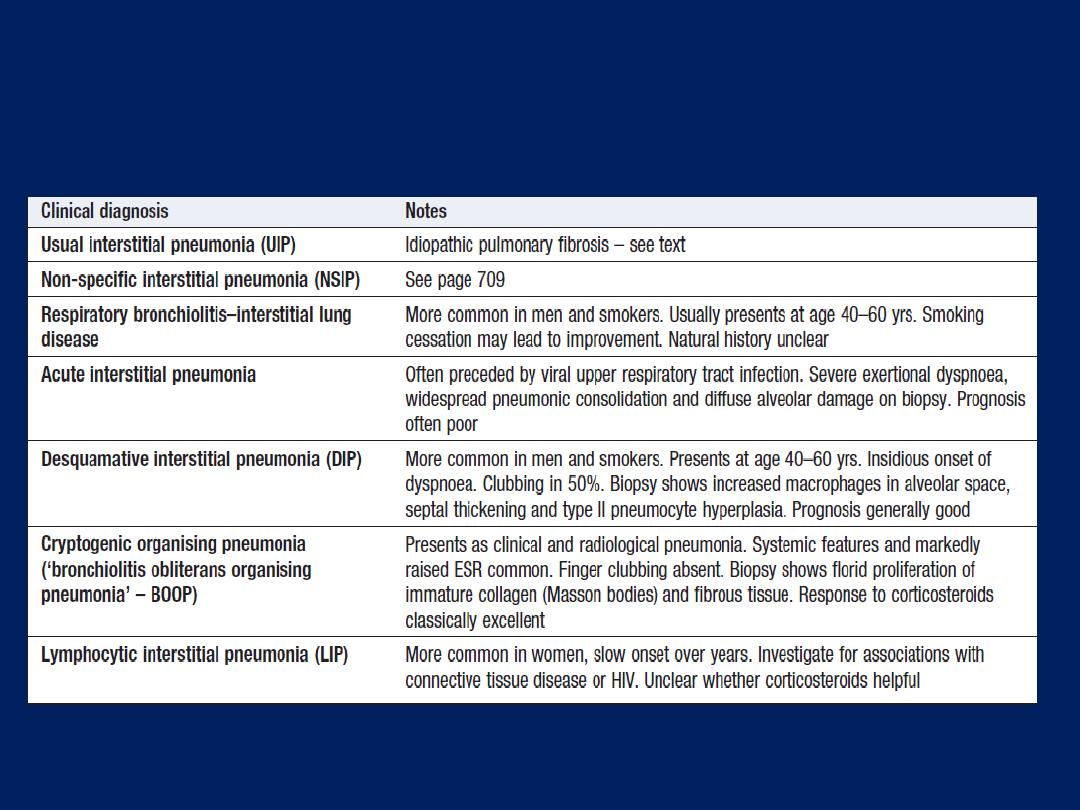

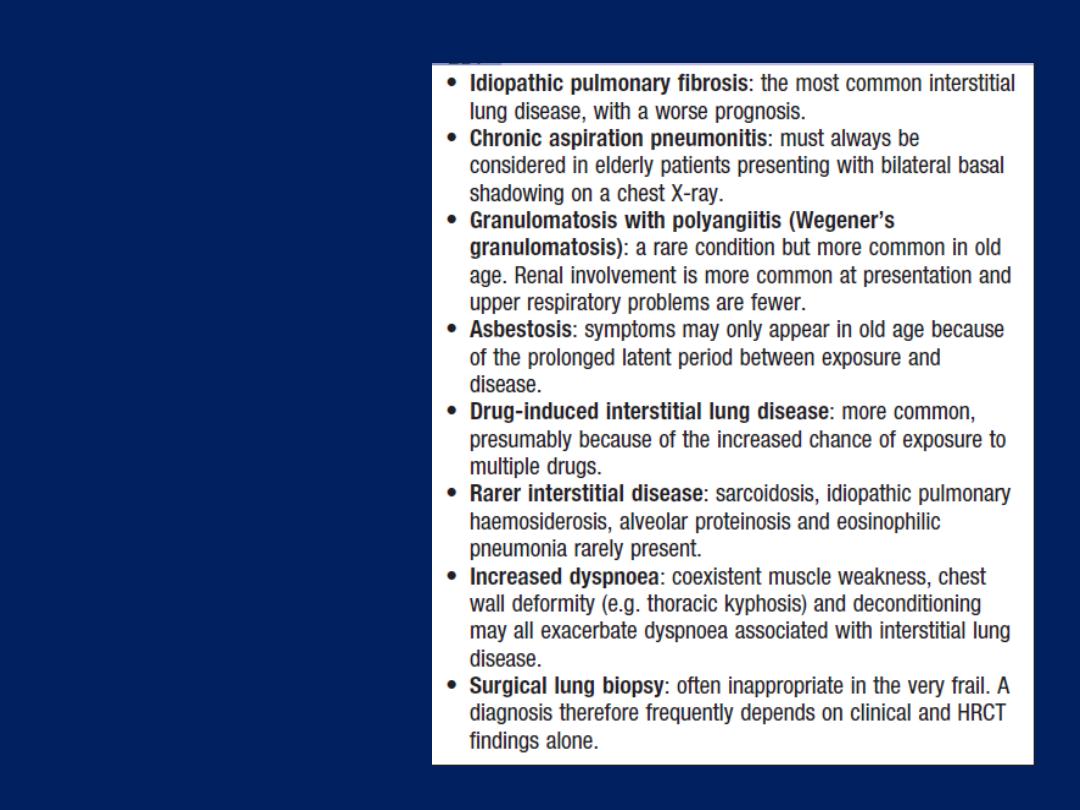

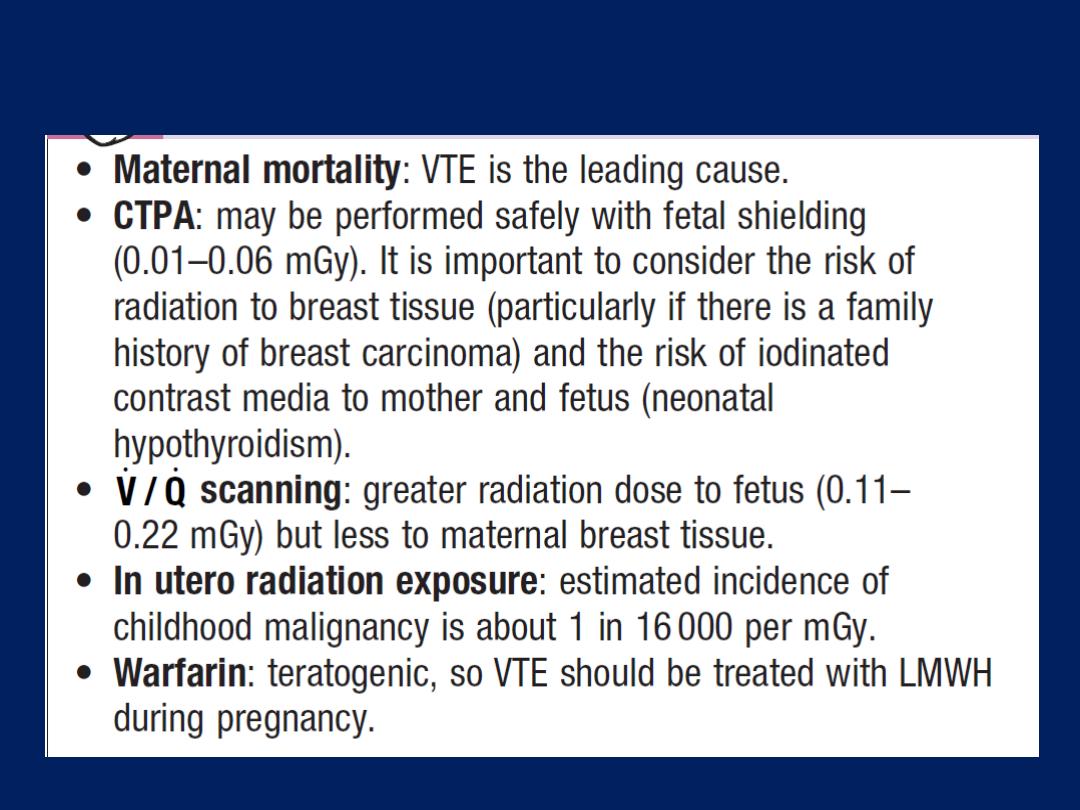

FIG.

Respiratory function tests in health and disease.

A

Volume/time traces from forced expiration in a normal subject, in

COPD and in fibrosis.

COPD

causes slow, prolonged and limited

exhalation. In

fibrosis,

forced expiration results in rapid expulsion

of a reduced forced vital capacity (FVC). Forced expiratory volume

(FEV

1

) is reduced in both diseases but is disproportionately reduced,

compared to FVC, in COPD.

B

The same data plotted as flow/volume loops. In COPD, collapse

of intrathoracic airways limits flow, particularly during mid- and late

expiration. The blue trace illustrates large airway obstruction, which

particularly limits peak flow rates.

C

Lung volume measurement. Volume/time graphs during quiet

breathing with a single maximal breath in and out. COPD causes

hyperinflation with increased residual volume.

Fibrosis

causes a proportional reduction in all lung volumes.

Measurement of airway obstruction

Airway narrowing is assessed by asking patients to blow

out as

hard

and as

fast

as they can into a peak flow

meter or a spirometer. Peak flow meters are cheap and

convenient for home monitoring of peak expiratory flow

(PEF) in the detection and monitoring of asthma, but results

are effort-dependent. More accurate and reproducible

measures are obtained by inhaling fully, then exhaling at

maximum effort into a spirometer.

The forced expired volume in 1 second (FEV

1

) is the volume

exhaled in the first second, and the forced vital capacity

(FVC)

is the

total volume exhaled.

FEV

1

is disproportionately reduced in airflow obstruction,

resulting in FEV

1

/FVC ratios of < 70%. In this situation,

spirometry should be repeated following inhaled short-

acting β

2

-adrenoceptor agonists (e.g. salbutamol); a

large improvement in FEV

1

(

over 400 mL

) and variability

in peak flow over time are features of asthma .

To distinguish large

airway narrowing (e.g. tracheal

stenosis or compression)

from small

airway narrowing,

flow/volume loops are recorded using spirometry.

These display flow in relation to lung volume (rather than

time) during maximum expiration and inspiration, and the

pattern of flow reveals the site of airflow obstruction

Lung volumes

Tidal volume and vital capacity (VC – the maximum

amount of air that can be expelled from the lungs after

the deepest possible breath) can be measured by

spirometry. Total lung capacity (TLC – the total amount of

air in the lungs

after

taking the deepest breath possible)

can be measured by asking the patient to rebreathe an

inert non-absorbed gas (usually

helium

) and recording how

much the test gas is diluted by lung gas. This measures

the volume of intrathoracic gas that mixes with tidal

breaths. Alternatively, lung volume may be measured

by body

plethysmography

, which determines the

pressure/volume relationship of the thorax. This method

measures total intrathoracic gas volume, including

poorly ventilated areas such as bullae.

Transfer factor

To measure the capacity of the lungs to exchange gas,

patients inhale a test mixture of 0.3% carbon monoxide,

which is taken up

avidly by haemoglobin

in pulmonary

capillaries.

After a short breath-hold, the

rate of disappearance

of

CO into the circulation is calculated from a sample of

expirate, and expressed as the TLCO or carbon monoxide

transfer factor.

Helium is also included in the test breath to allow

calculation of the volume of lung examined by the test

breath. Transfer factor expressed per unit lung volume is

termed KCO.

How to interpret respiratory function abnormalities

Arterial blood gases and oximetry

The measurement of hydrogen ion concentration, PaO

2

and PaCO

2

, and derived bicarbonate concentration in an

arterial blood sample is essential to assess the degree

and type of respiratory failure, and for measuring acid–

base status. Interpretation of results is made easier by

blood gas diagrams ,which indicate whether any

acidosis or alkalosis

is due to acute or chronic respiratory

derangements of PaCO

2

, or to metabolic causes.

Pulse oximeters with finger or ear probes measure the

difference in absorbance of light by oxygenated and

deoxygenated blood to calculate its oxygen saturation

(SaO

2

). This allows non-invasive continuous assessment

of oxygen saturation in patients, which is useful in

assessing hypoxaemia and its response to therapy.

Exercise tests

Resting measurements may be unhelpful in early disease

or in patients complaining only of exercise-induced

symptoms. Exercise testing with spirometry before and

after can help demonstrate exercise-induced asthma.

Walk tests include the self-paced

6-minute walk

and

the externally paced incremental ‘

shuttle

’ test, where

patients walk at increasing pace between two cones

10 m apart. These provide simple, repeatable assessments

of disability and response to treatment.

Cardiopulmonary bicycle exercise testing, with measurement

of metabolic gas exchange, ventilation and ECG changes, is

useful for quantifying exercise limitation and detecting occult

CV or respiratory limitation in a breathless patient.

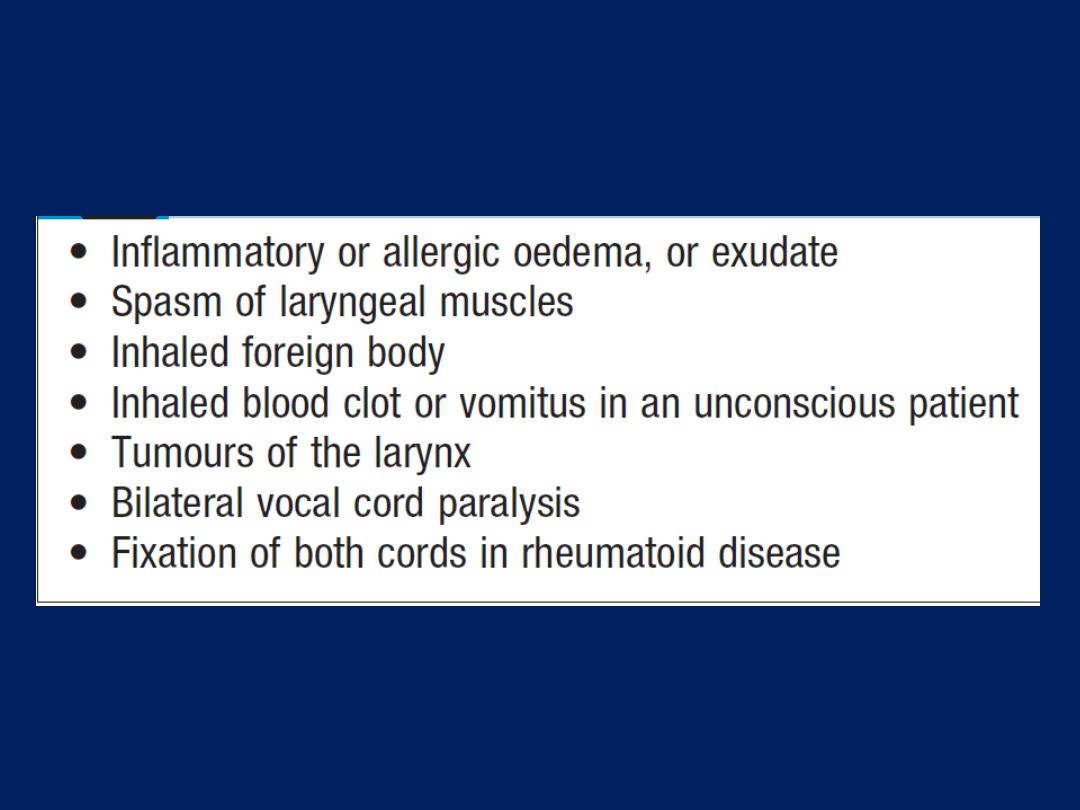

PRESENTING PROBLEMS IN RESPIRATORY DISEASE

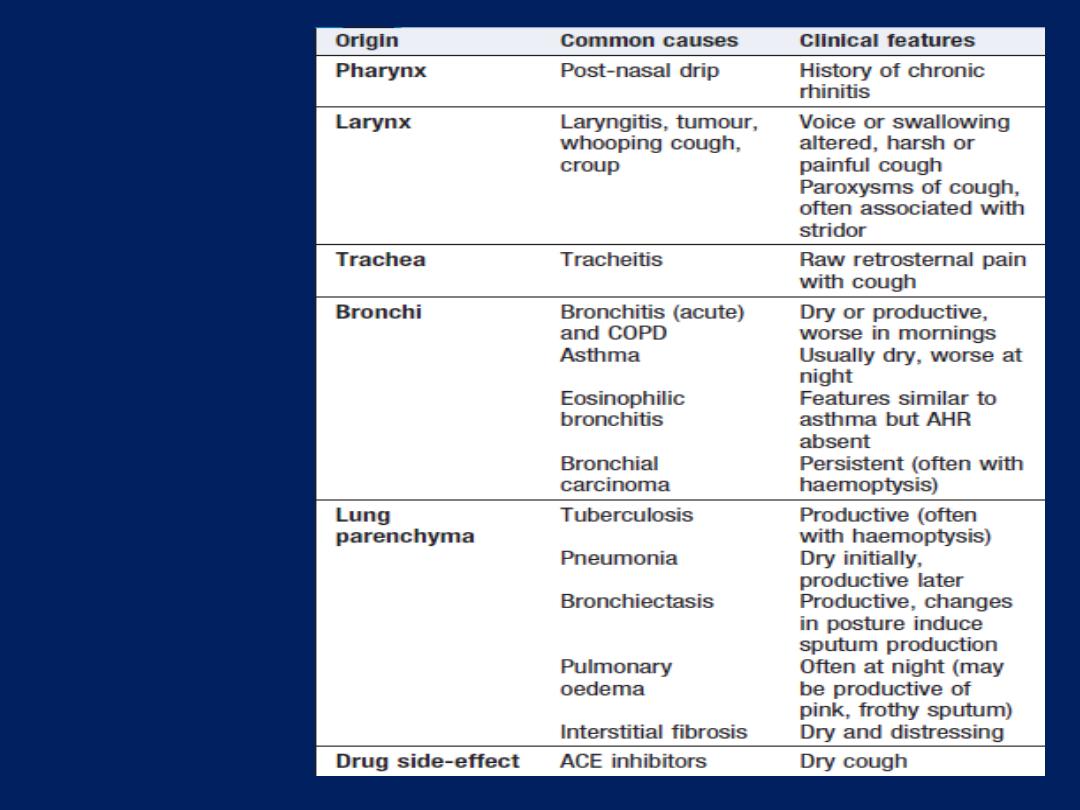

Cough

Caused by stimulation of sensory nerves in the mucosa of

the pharynx, larynx, trachea and bronchi. Cough reflex

induced by changes in air temperature or exposure to

irritants. The explosive quality of a normal cough is lost in

patients with respiratory muscle paralysis or vocal cord

palsy. Paralysis of a single vocal cord gives rise to a

prolonged, low-pitched, inefficient ‘bovine’ cough

accompanied by hoarseness. Coexistence of an

inspiratory noise (stridor)

indicates partial obstruction of

a major airway (e.g. laryngeal oedema, tracheal tumour,

scarring, compression or inhaled foreign body) and

requires urgent investigation and treatment.

Cough

AHR =

airway hyper-reactivity

Causes of cough

Acute

transient cough is most commonly caused by viral

lower respiratory tract infection, post-nasal drip resulting

from rhinitis or sinusitis, aspiration of a foreign body, or

throat-clearing secondary to laryngitis or pharyngitis ,

pneumonia, aspiration, congestive heart failure or

pulmonary embolism.

Chronic

cough present more of a challenge, especially

when physical examination, chest X-ray and lung function

studies are normal

. In this context, it is most often

explained by cough-variant asthma, post-nasal drip

secondary to nasal or sinus disease, or gastro-

oesophageal reflux with aspiration, diagnosis of the latter

may require ambulatory oesophageal pH monitoring or a

prolonged trial of anti-reflux therapy

ACE inhibitors cause chronic cough in 10% -15%.

Bordetella pertussis infection in adults can also result in

protracted cough.

While most patients with a bronchogenic carcinoma have

an abnormal chest X-ray on presentation, fibreoptic

bronchoscopy or thoracic CT is advisable in most adults

(especially smokers) with otherwise unexplained cough of

recent onset, as this may reveal a small endobronchial

tumour or unexpected foreign body. In a small percentage

of patients, dry cough may be the presenting feature of

interstitial lung disease.

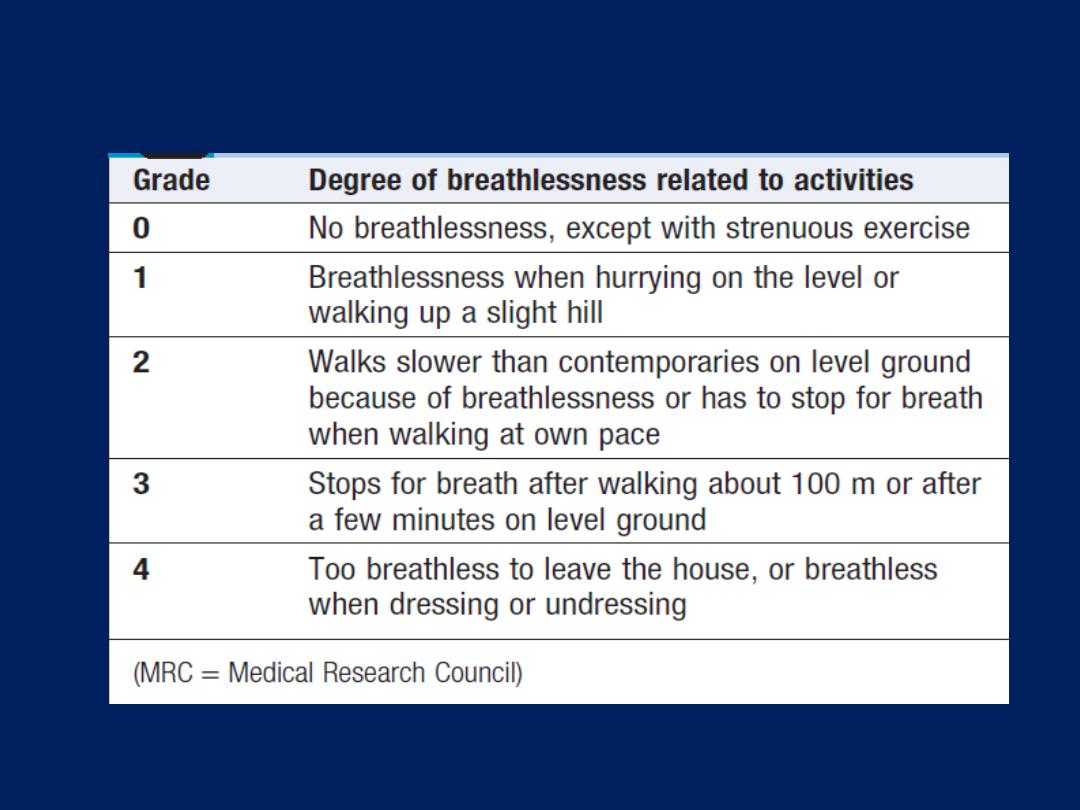

Breathlessness

The feeling of an uncomfortable need to breathe. It is

unusual

among sensations, as it has no defined receptors,

no localised representation in the brain.

Pathophysiology

Respiratory diseases can stimulate dyspnoea by:

• stimulating intrapulmonary sensory nerves (e.g.

pneumothorax, interstitial inflammation and pulmonary embolus)

• increasing the mechanical

load

on the respiratory muscles (e.g.

airflow obstruction or pulmonary fibrosis)

• causing hypoxia, hypercapnia or acidosis, which stimulate

chemoreceptors.

In cardiac failure

,

pulmonary congestion reduces compliance and

can also obstruct the small airways. Reduced cardiac output also limits

oxygen supply to the skeletal muscles, causing early lactic acidaemia

and further stimulating breathing via the central chemoreceptors.

Differential diagnosis

Chronic exertional breathlessness

Key questions include:

How is your breathing at rest and overnight?

In

COPD,

there is a fixed, structural limit to maximum

ventilation, and a tendency for progressive hyperinflation

during exercise. Breathlessness is mainly apparent

when

walking

, and patients usually report minimal

symptoms at rest and overnight. Orthopnoea

, however,

is

common in COPD, as well as in heart disease, because

airflow obstruction is made worse by cranial displacement

of the diaphragm by the abdominal contents when

recumbent, so many patients choose to sleep propped up.

In contrast

, patients with significant

asthma

are often

woken from their sleep by breathlessness with chest

tightness and wheeze.

How much can you do on a good day?

Noting ‘breathless on exertion’ is not enough; the

approximate distance the patient can walk on the level

, along with capacity to climb inclines or stairs. In mild

asthma, the patient may be free of symptoms and signs

when well. Gradual, progressive loss of exercise capacity

over months and years, is typical of COPD.

Relentless, progressive breathlessness , present at rest, often

accompanied by a dry cough, suggests interstitial fibrosis

Impaired left ventricular function can cause chronic

exertional breathlessness, cough and wheeze. A history of

angina, hypertension or myocardial infarction raises the

possibility of a cardiac cause. The chest X-ray may show

cardiomegaly, ECG and echo may provide evidence of left

ventricular disease. Measurement of arterial blood gases

may help, as, in the absence of an intracardiac shunt or

pulmonary oedema, the PaO

2

in cardiac disease is

normal and the PaCO

2

is low or normal.

Did you have breathing problems in childhood or at

school? A history of childhood wheeze increases

the likelihood of asthma, although this history may be

absent in late-onset asthma. A history of atopic allergy

also increases the likelihood of asthma.

Do you have other symptoms along with your

breathlessness?

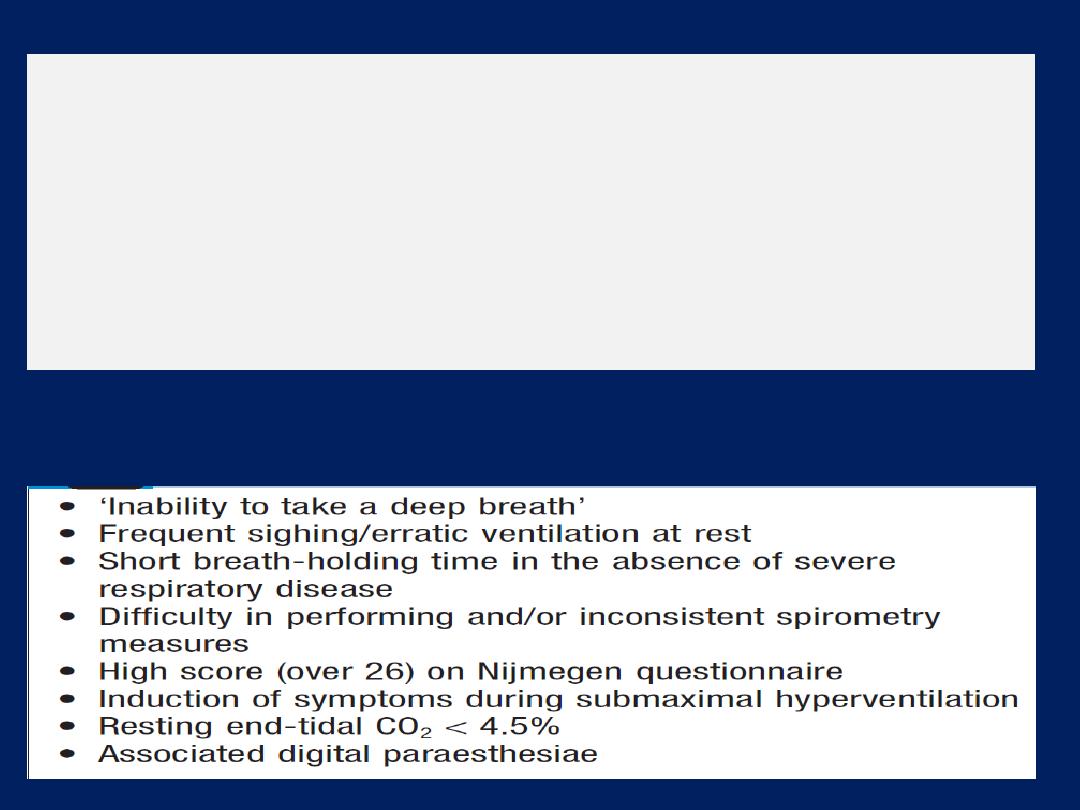

Digital or perioral paraesthesiae and a feeling that ‘I

cannot get a deep enough breath in’ are typical features

of psychogenic hyperventilation. Additional symptoms

include lightheadedness, central chest discomfort or even

carpopedal spasm due to acute respiratory alkalosis.

Psychogenic breathlessness rarely disturbs sleep,

frequently occurs at rest, may be provoked by stressful

situations and may even be relieved by exercise. The

Nijmegen questionnaire can be used to score some of the

typical symptoms of hyperventilation. Arterial blood gases

show normal PO

2

, low PCO

2

and alkalosis.

Pleuritic chest pain with chronic breathlessness,

particularly if it occurs in more than one site over time,

should raise suspicion of thromboembolic disease.

Morning headache is an important symptom in patients

with breathlessness, as it may signal the onset of carbon

dioxide retention and respiratory failure.

Factors suggesting psychogenic hyperventilation

Acute severe breathlessness

This is one of the most common and dramatic medical

emergencies. The history and a rapid but careful

examination will usually suggest a diagnosis , confirmed

by investigations, chest X-ray, ECG and blood gases.

History

Establish the rate of onset and severity and whether

cardiovascular symptoms (chest pain, palpitations,

sweating and nausea) or respiratory symptoms

(cough,

wheeze, haemoptysis, stridor)

are present. A previous history of

LV ventricular failure, asthma or COPD is valuable. In the

severely ill patient, it may be necessary to obtain the

history from accompanying witnesses. In children, the

possibility of inhalation of a foreign body or acute

epiglottitis should always be considered.

Clinical assessment

• level of consciousness

• degree of central cyanosis

• evidence of anaphylaxis (urticaria or angioedema)

• patency of the upper airway

• ability to speak (in single words or sentences)

• cardiovascular status (heart rate and rhythm, blood

pressure and degree of peripheral perfusion).

Pulmonary oedema is suggested by pink, frothy sputum

and bi-basal crackles.

Asthma or COPD by wheeze and prolonged expiration;

pneumothorax by a silent resonant hemithorax; and

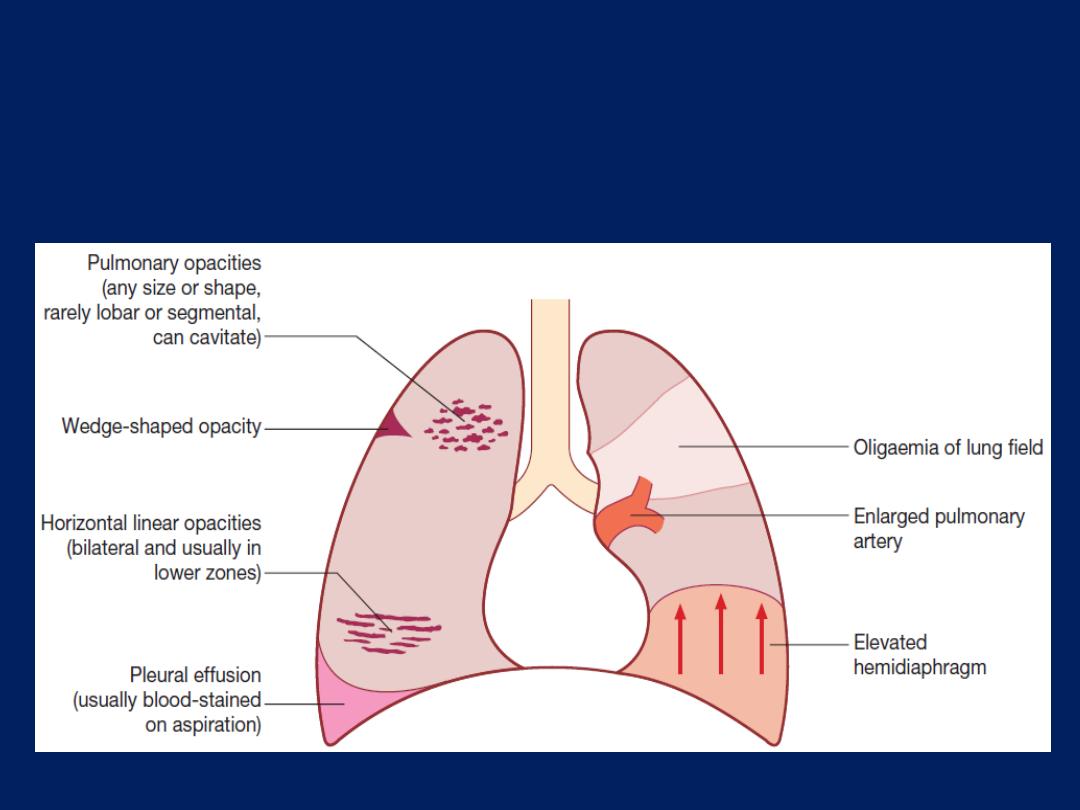

pulmonary embolus by severe breathlessness with

normal breath sounds. Leg swelling may suggest cardiac

failure or, if asymmetrical, venous thrombosis.

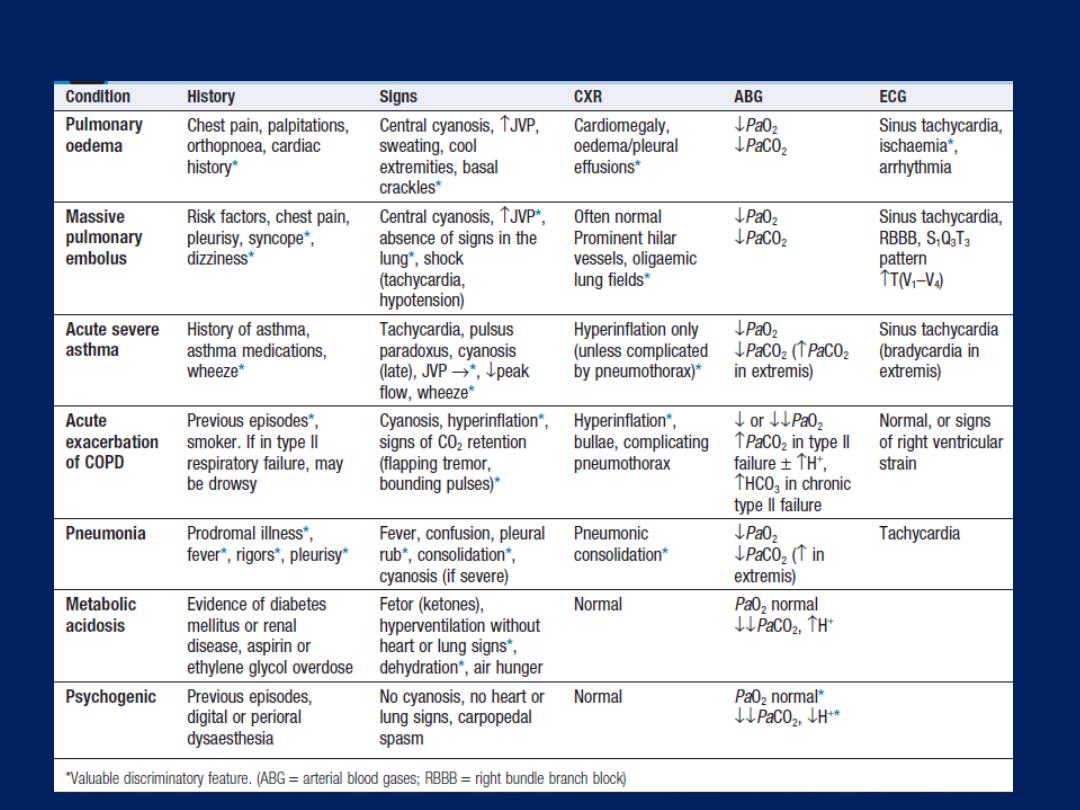

System

Acute dyspnoea

Chronic exertional

dyspnoea

Cardiovascular

*Acute pulmonary oedema

Chronic heart failure

Myocardial ischaemia (angina

equivalent)

Respiratory

*Acute severe asthma

*Acute exacerbation of COPD

*Pneumothorax

*Pneumonia

*Pulmonary embolus

ARDS

Inhaled foreign body (especially in children)

Lobar collapse

Laryngeal oedema (e.g. anaphylaxis)

*COPD

*Chronic asthma

Bronchial carcinoma

Interstitial lung disease

(sarcoidosis, fibrosing alveolitis,

extrinsic allergic alveolitis,

pneumoconiosis)

Chronic pulmonary

thromboembolism

Lymphatic carcinomatosis (may

cause intolerable

breathlessness)

Large pleural effusion(s)

Others

Metabolic acidosis (e.g. diabetic

ketoacidosis, lactic acidosis, uraemia,

overdose of salicylates, ethylene glycol

poisoning)

Psychogenic hyperventilation (anxiety or

panic-related)

Severe anaemia

Obesity

Deconditioning

Causes of breathlessness

Differential diagnosis of acute breathlessness

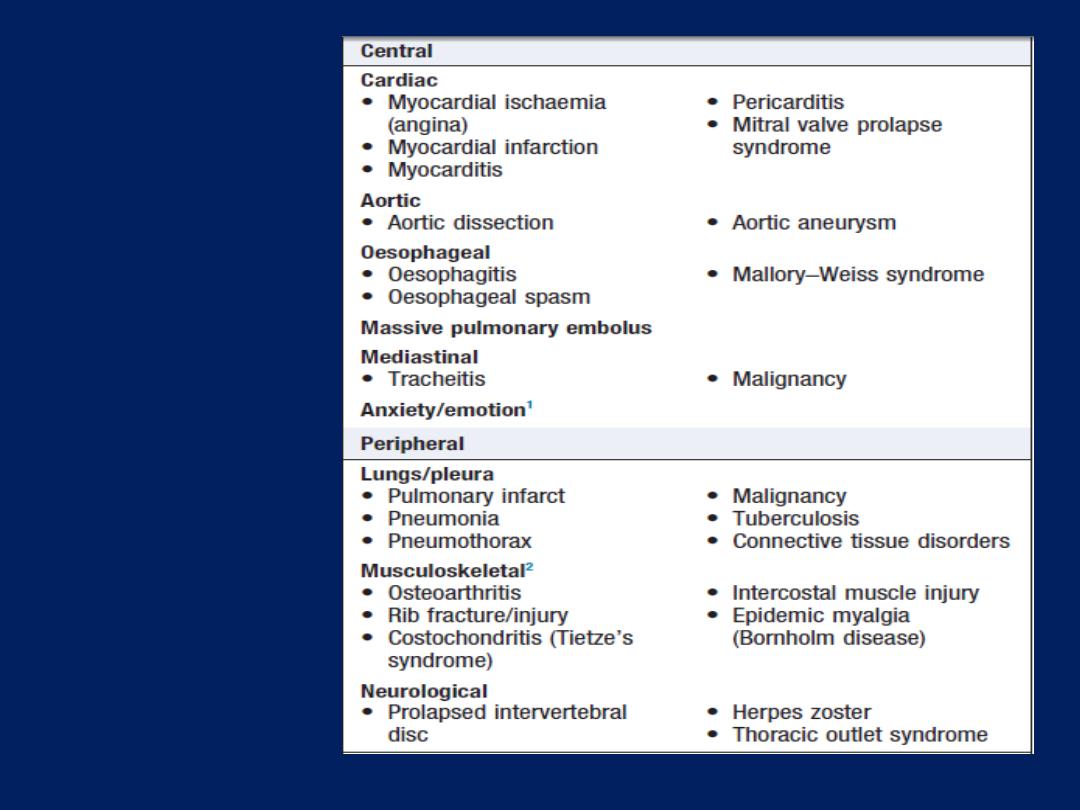

Chest pain

Pleurisy, a sharp chest pain aggravated by deep

breathing or coughing, feature of pulmonary infection or

infarction; malignancy. On examination, rib movement may

be restricted and a pleural rub may be present.

Malignant involvement of the chest wall or ribs can cause

gnawing, continuous local pain. Central chest pain suggests

heart disease but also occurs with tumours affecting the

mediastinum, oesophageal disease or disease of the

thoracic aorta . Massive pulmonary embolus may cause

ischaemic cardiac pain, as well as severe breathlessness.

Tracheitis produces raw upper retrosternal pain,

exacerbated by the accompanying cough.

Musculoskeletal chest wall pain is usually exacerbated by

movement and associated with local tenderness.

Differential

diagnosis of

chest pain

1 May also cause peripheral

chest pain.

2 Can sometimes cause

central chest pain.

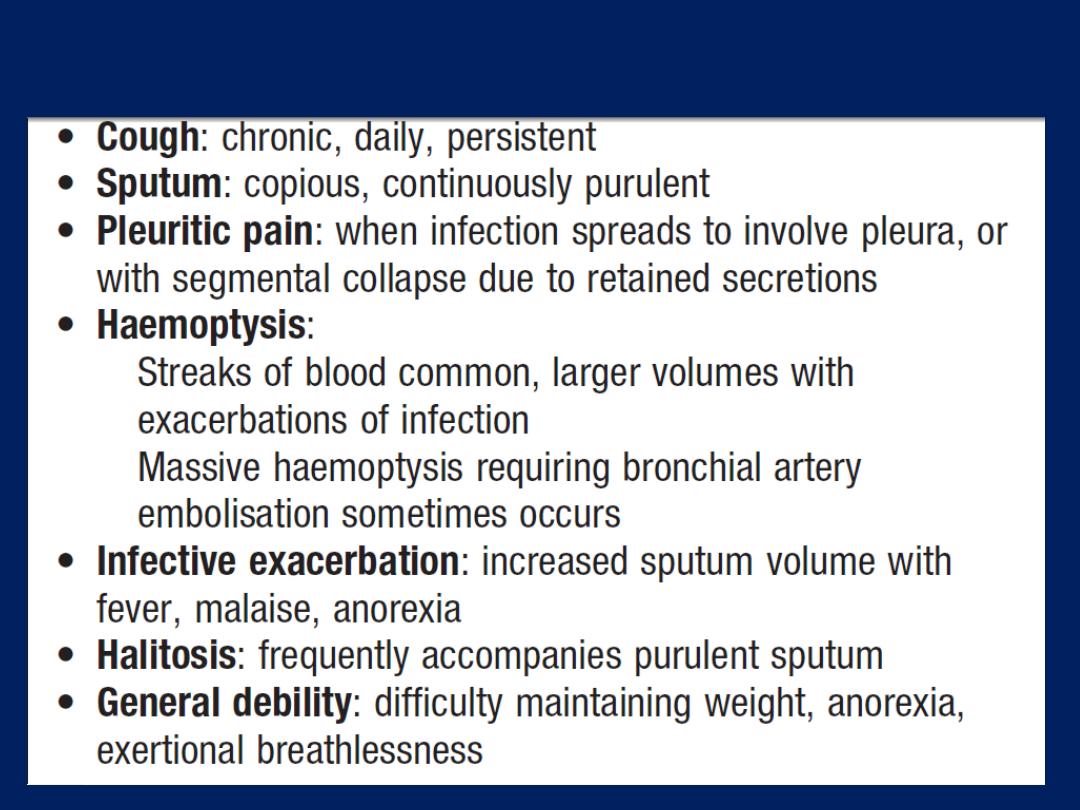

Haemoptysis

Coughing up blood, irrespective of the amount, is an

alarming symptom and patients nearly always seek

medical advice. Care should be taken to establish that it is

true haemoptysis and not haematemesis, or gum or

nose bleeding. Many episodes of haemoptysis remain

unexplained, even after full investigation, and are likely to

be due to simple bronchial infection. A history of

repeated small haemoptysis, or blood-streaking of

sputum, is highly suggestive of bronchial carcinoma.

Fever, night sweats and weight loss suggest tuberculosis.

Pneumococcal pneumonia often causes ‘rusty’-coloured

sputum but can cause frank haemoptysis, as can all

suppurative pneumonic infections, including lung abscess .

Bronchiectasis and intracavitary mycetoma can cause

catastrophic bronchial haemorrhage, and in these patients

there may be a history of previous tuberculosis or

pneumonia in early life, pulmonary thromboembolism is a

common cause and should always be considered. Physical

examination may reveal clues. Clubbing suggests bronchial

carcinoma or bronchiectasis; other signs of malignancy, such

as cachexia, hepatomegaly and lymphadenopathy, should

be sought. Fever, pleural rub and signs of consolidation; a

minority with pulmonary infarction also have unilateral leg

swelling or pain suggestive of DVT . Rashes, haematuria

and digital infarcts point to an underlying vasculitis, which

may be associated with haemoptysis.

Bronchial disease

• Carcinoma* • Bronchiectasis* • Acute bronchitis* • Bronchial

adenoma • Foreign body

Parenchymal disease

Tuberculosis* • Suppurative neumonia • Parasites (e.g. hydatid

disease, flukes) • Lung abscess • Trauma • Actinomycosis • Mycetoma

Lung vascular disease

Pulmonary infarction* • Goodpasture’s syndrome • Polyarteritis

nodosa • Idiopathic pulmonary haemosiderosis

Cardiovascular disease

• Acute left ventricular failure* • Mitral stenosis • Aortic aneurysm

Blood disorders

• Leukaemia • Haemophilia • Anticoagulants

*More common causes

Causes of haemoptysis

Management

In severe acute haemoptysis, the patient should be nursed

upright (or on the side of the bleeding, if this is known),

given high-flow oxygen and resuscitated as required.

Bronchoscopy in the acute phase is difficult bronchial

tree. If radiology shows an obvious central cause, then rigid

bronchoscopy under general anaesthesia may allow

intervention to stop bleeding; however, the source often

cannot be visualised. Intubation with a divided

endotracheal tube may allow protected ventilation of the

unaffected lung to stabilise the patient. Bronchial

arteriography and embolisation , or even emergency

surgery, can be life-saving in the acute situation.

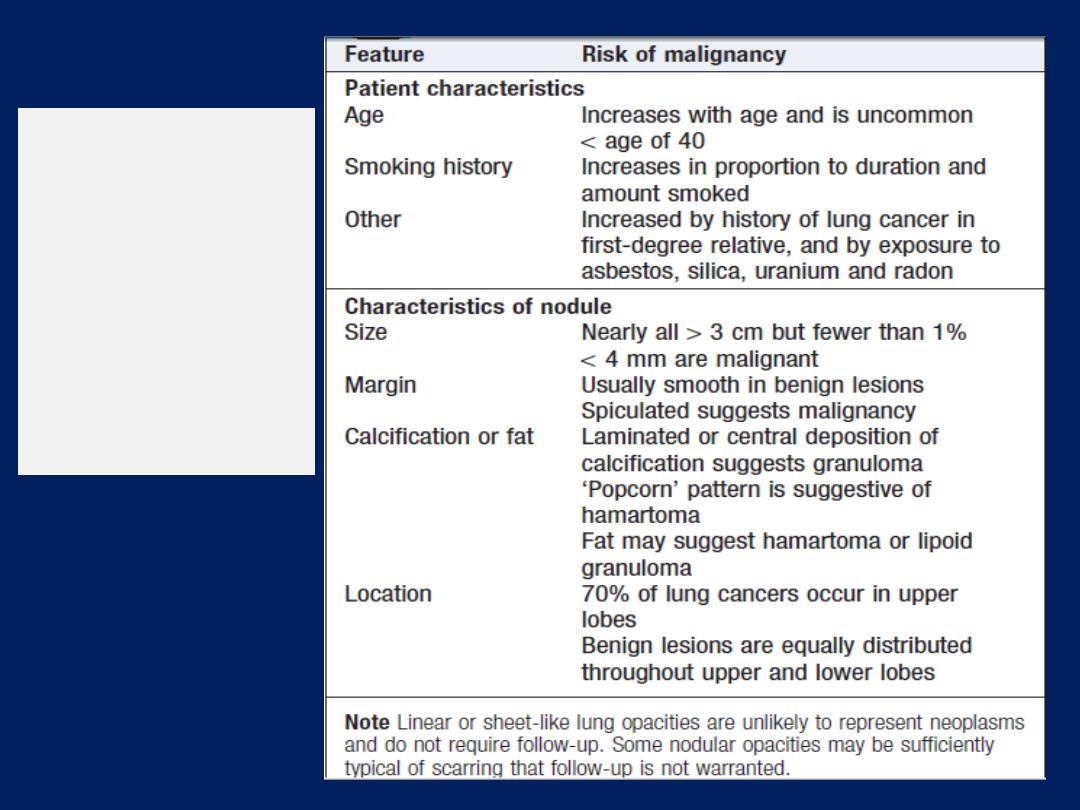

The incidental pulmonary nodule

The incidental finding of a rounded opacity measuring up

to 3 cm in diameter is common. Majority are benign

(unchanged over 2 years). Otherwise, the likelihood of

malignancy is assessed by considering the characteristics

of the patient, age, smoking history , history of prior

malignancy, and the appearance of the nodule in terms of

its size, margin, density and location . Ther are invariably

beyond the vision of the bronchoscope , endoscopic

bronchoscopic ultrasound may overcome this . Tissue is most

commonly obtained using percutaneous needle biopsy

under ultrasound or CT guidance, complicated by

pneumothorax in 20%, this technique should only be

contemplated with an FEV1 of >35% predicted.

Haemorrhage into the lung or pleural space, air embolism

and tumour seeding are rare. PET scanning provides useful

information about nodules of at least 1 cm in diameter, high

metabolic activity is strongly suggestive of malignancy,

while an inactive ‘cold’ nodule is benign . False-positive may

occur with some infectious or inflammatory nodules, and

false-negative results with neuro-endocrine tumours and

bronchiolo-alveolar cell carcinomas. Where tissue biopsy is

contraindicated and the lesion is too small to be assessed

by PET, interval thoracic CT may be considered. The period

between scans is based upon the average tumour doubling

time . However, there is risk of radiation exposure. If the

nodule is highly likely to be malignant and the patient is

fit, the best option may be to proceed to surgical resection.

Common causes

• Bronchial carcinoma • Single metastasis • Localised

pneumonia • Lung abscess • Tuberculoma • Pulmonary

infarct

Uncommon causes

• Benign tumours • Lymphoma • Arteriovenous malformation

• Hydatid cyst • Bronchogenic cyst • Rheumatoid nodule •

Pulmonary sequestration • Pulmonary haematoma •

Wegener’s granuloma • ‘Pseudotumour’ – fluid collection in

a fissure • Aspergilloma (usually surrounded by air ‘halo’)

Causes of pulmonary nodules

Clinical and

radiographic

features

distinguishing

benign from

malignant

nodules

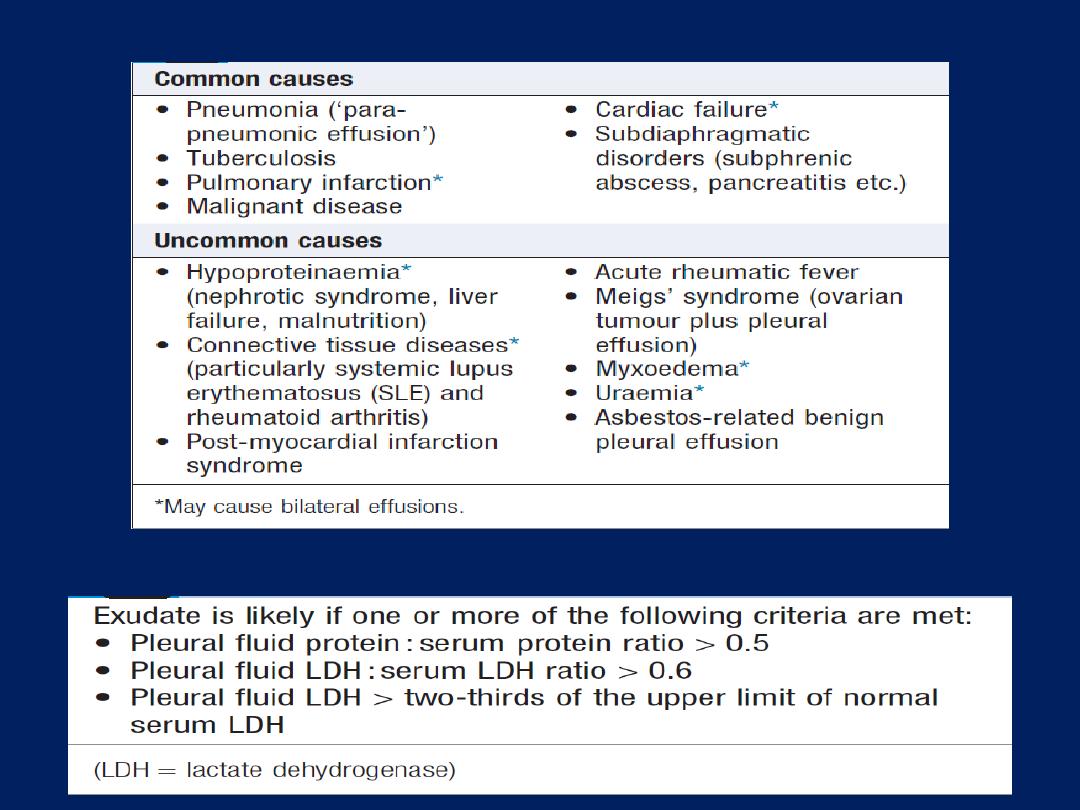

Pleural effusion

The accumulation of serous fluid within the pleural

space.The accumulation of frank pus is termed empyema ,

that of blood is haemothorax, and that of chyle is a

chylothorax. In general, pleural fluid accumulates as a

result of either increased hydrostatic pressure or

decreased osmotic pressure (‘transudative’ effusion, as

seen in cardiac, liver or renal failure), or from increased

microvascular pressure due to disease of the pleura or

injury in the adjacent lung (‘exudative’ effusion).

The causes of the majority of pleural effusions are

identified by a thorough history, examination and

relevant investigations.

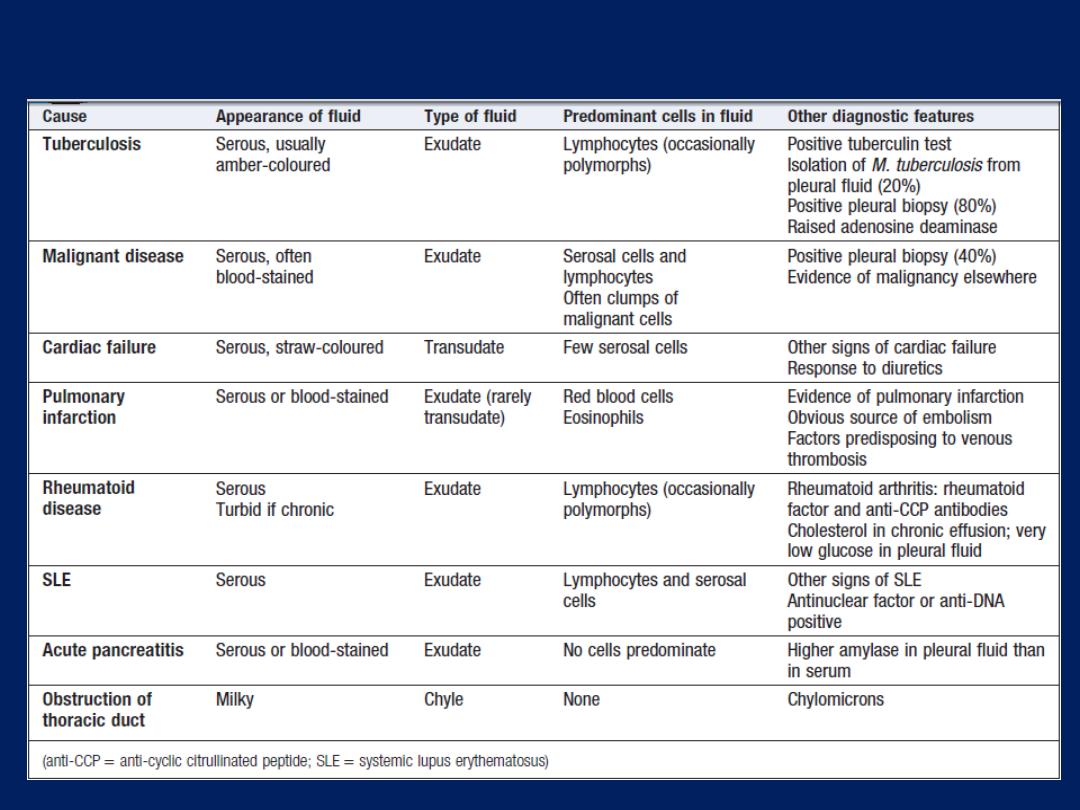

Causes of pleural effusion

Light’s criteria

Pleural effusion: main causes and features

Clinical assessment

Symptoms (pain on inspiration and coughing) and signs

of pleurisy (a pleural rub) often precede the effusion,

especially in pneumonia, pulmonary infarction or

connective tissue disease. However, when breathlessness is

the only symptom, depending on the size and rate of

accumulation, the onset may be insidious.

Investigations

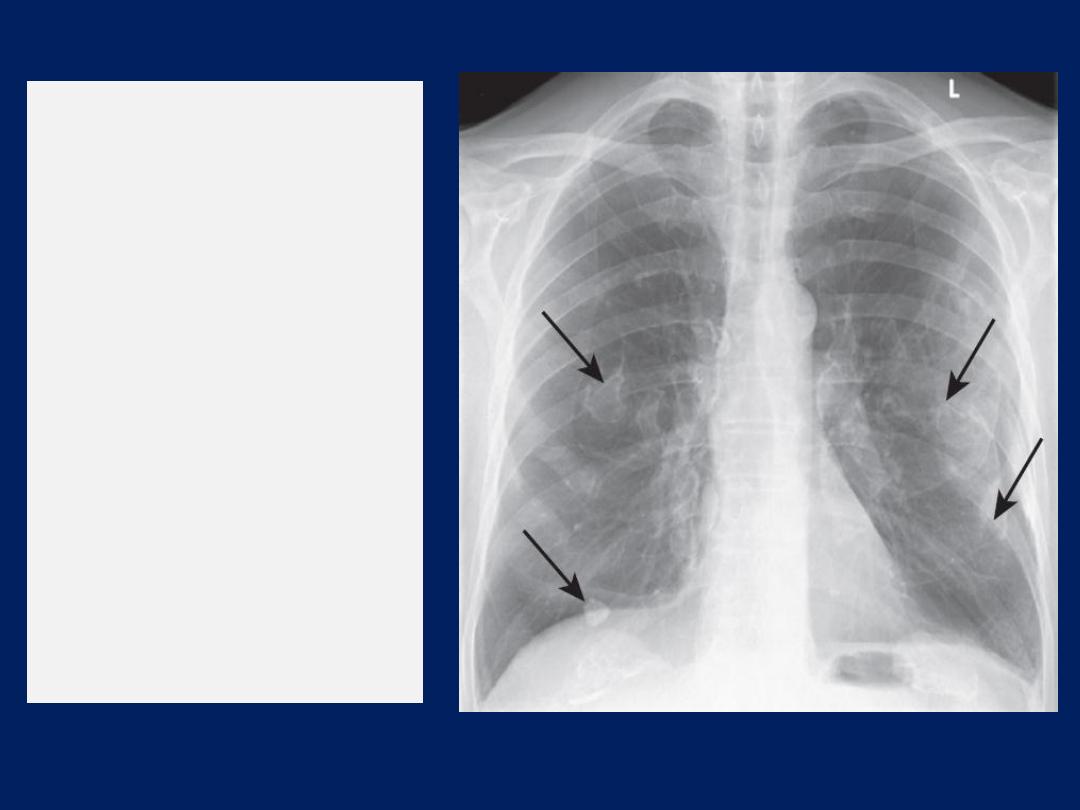

Radiological investigations

The classical appearance is a curved shadow at the lung base,

blunting the costophrenic angle and ascending towards the axilla .

Fluid appears to track up the lateral chest wall. In fact, fluid

surrounds the whole lung at this level, but casts a radiological

shadow only where the X-ray beam passes tangentially across the

fluid against the lateral chest wall. Around 200 mL of fluid is

required to be detectable on a PA chest X-ray.

Pleural fluid below the lower lobe (‘subpulmonary effusion’)

simulates an elevated hemidiaphragm. Pleural fluid

localised within an oblique fissure may produce a rounded

opacity that may be mistaken for a tumour.

Ultrasound is more accurate than plain chest X-ray

for determining the presence of fluid. CT scanning is

indicated where malignant disease is suspected.

Pleural aspiration and biopsy

In some conditions (e.g. left ventricular failure), it should

not be necessary to sample fluid unless atypical features

are present. However, in most other circumstances,

diagnostic sampling is required. Simple aspiration provides

information on the colour and texture of fluid may

immediately suggest an empyema or chylothorax.

The presence of blood is consistent with pulmonary

infarction or malignancy, traumatic tap. Biochemical

analysis allows classification into transudate and exudates.

The predominant cell type and cytological examination is

essential. A low pH suggests infection , rheumatoid arthritis,

ruptured oesophagus or advanced malignancy. Ultrasound-

or CT-guided biopsy provides tissue for pathological and

microbiological analysis. Where necessary,

video-assisted

thoracoscopy allows visualisaton and direct guidance of a biopsy .

Management

Therapeutic aspiration may be required to palliate breathlessness but

removing more than 1.5 L at a time is associated with a small risk of

re-expansion pulmonary oedema. Pleural effusion

Should never

be

drained to dryness before diagnosis, as biopsy may be precluded

until further fluid accumulates. Treatment of the underlying cause.

Empyema

This is a collection of pus in the pleural space, which

may be as thin as serous fluid or so thick that it is

impossible to aspirate, even through a wide-bore needle.

Microscopically, neutrophil leucocytes are present in large

numbers. An empyema may involve the whole pleural

space or only part of it (‘loculated’ or ‘encysted’

empyema) and is usually unilateral. It is always

secondary to infection in a neighbouring structure, usually

the lung, most commonly due to the bacterial pneumonias

and tuberculosis. Over 40% of patients with community-

acquired pneumonia develop an associated pleural

effusion (‘para-pneumonic’ effusion) and about 15% of

these become secondarily infected.

Other causes are infection of a haemothorax following

trauma or surgery, oesophageal rupture, and rupture of

a subphrenic abscess. Both pleural surfaces are covered

with a thick, shaggy, inflammatory exudate and if the

condition is not adequately treated, pus may rupture into

a bronchus, causing a bronchopleural fistula and

pyopneumothorax, or track through the chest wall with the

formation of a subcutaneous abscess or sinus,

so-called empyema necessitans.

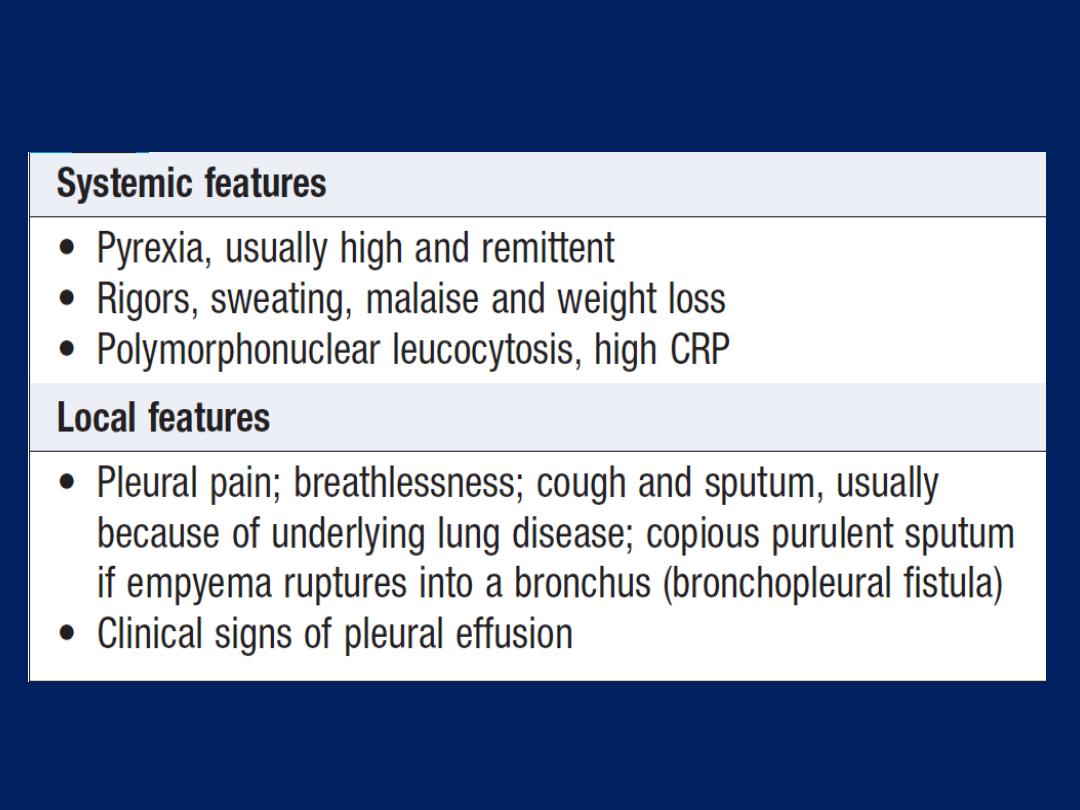

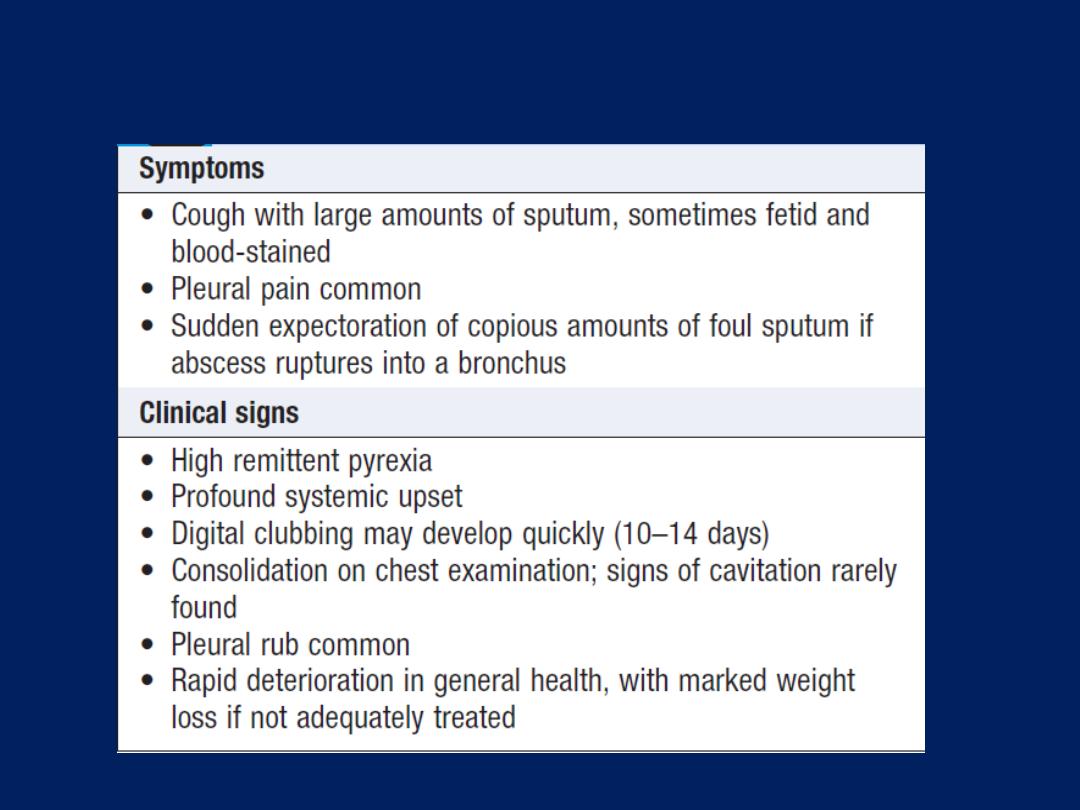

Clinical assessment

An empyema should be suspected in patients with

pulmonary infection if there is severe pleuritic chest pain or

persisting or recurrent pyrexia, despite appropriate

antibiotic treatment.

Clinical features of empyema

Investigations

Chest X-ray appearances may be indistinguishable from

pleural effusion, although pleural adhesions may confine the

empyema to form a ‘D’-shaped shadow against the inside of

the chest wall .When air is present as well as pus

(pyopneumothorax), a horizontal ‘fluid level’ marks the

air/liquid interface. Ultrasound shows the position of the

fluid, the extent of pleural thickening. CT provides

information on the pleura, underlying lung parenchyma and

patency of the major bronchi.

Ultrasound or CT is used to identify the optimal site for

aspiration. If the fluid is thick and turbid pus, empyema is

confirmed. Other features are a fluid glucose of less than

3.3 mmol/L

(60 mg/ dL),

LDH of >

1000 U/L,

or a fluid pH < 7.0 .

However, pH measurement should be avoided if pus is

thick, as it damages blood gas machines. The pus is

frequently sterile on culture if antibiotics have already

been given. The distinction between tuberculous and

non- tuberculous disease can be difficult and often

requires pleural biopsy, histology and culture.

Chest X-ray

showing a ‘D’-shaped

shadow in the left mid-zone,

consistent with an empyema. In this

case, an intercostal chest drain has

been inserted but the loculated

collection of pus remains.

Management

An empyema will only heal if infection is eradicated

and the empyema space is obliterated, allowing

apposition of the visceral and parietal pleural layers.

This can only occur if re-expansion of the compressed

lung is secured at an early stage by removal of all the pus

from the pleural space. When the pus is sufficiently thin,

this is most easily achieved by the insertion of a wide-bore

intercostal tube into the most dependent part of the

empyema space. If the initial aspirate reveals turbid fluid

or frank pus, or if loculations are seen on ultrasound, the

tube should be put on suction (

−5 to −10 cm H

2

O) and

flushed regularly with 20 mL normal saline.

A ppropriate antibiotic should be given for 2–4 weeks.

Empirical antibiotic treatment

(e.g. IV co-amoxiclav or cefuroxime

with metronidazole)

should be used if the organism is unknown.

Intrapleural fibrinolytic therapy is of no benefit. An

empyema can often be aborted if these measures are

started early, but if the intercostal tube is not providing

adequate drainage, for example, when the pus is thick or

loculated, surgical intervention is required to clear the

cavity of pus and break down adhesions.

Surgical ‘decortication’ may be required if gross

thickening of the visceral pleura is preventing re-

expansion of the lung. Surgery is also necessary if a

bronchopleural fistula develops.

Despite the availability of antibiotics, empyema remains

a significant cause of morbidity and mortality.

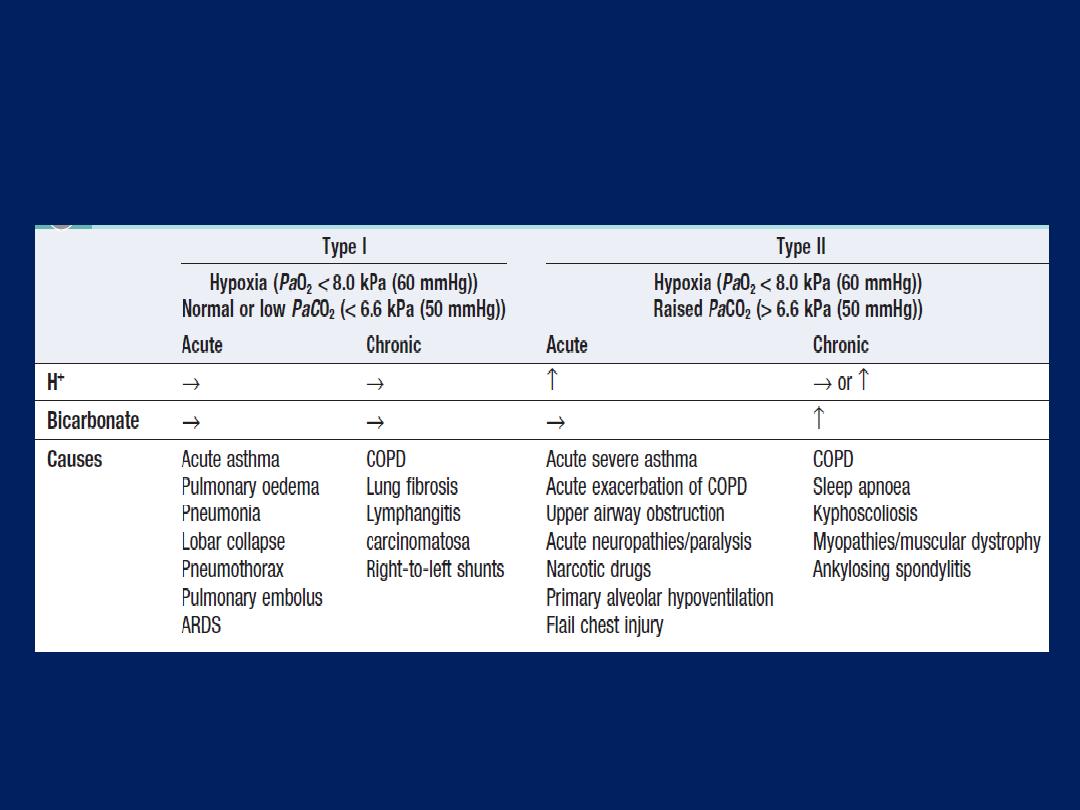

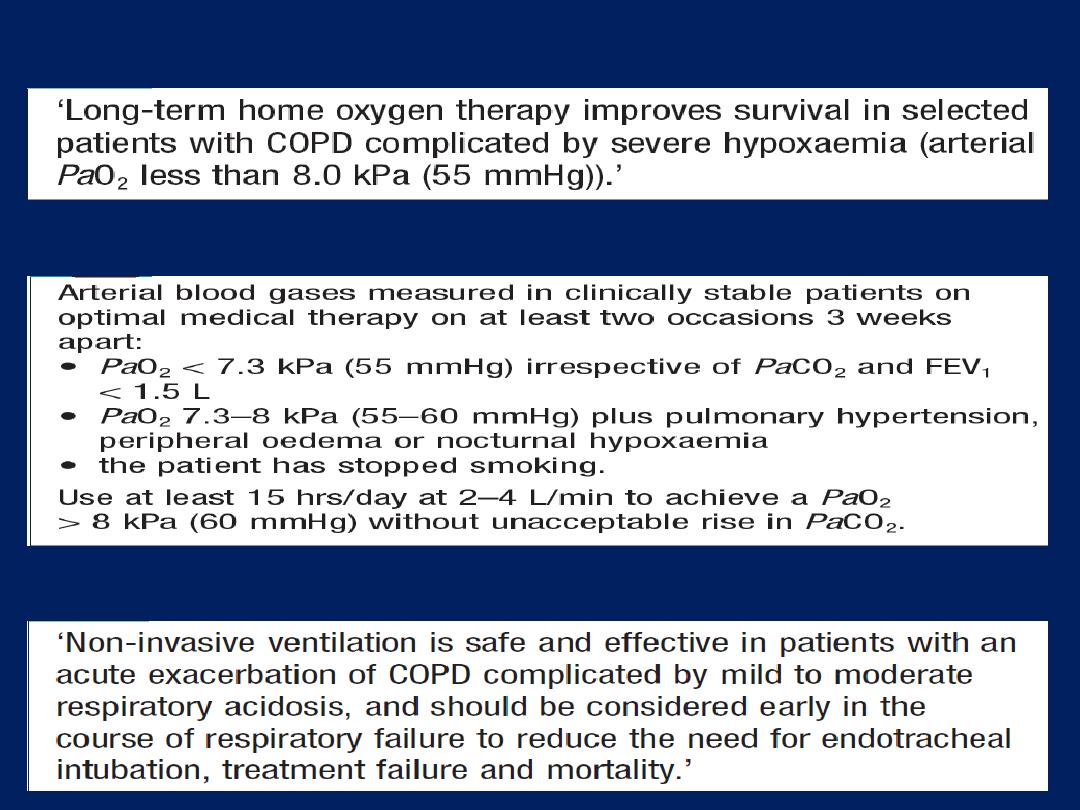

Respiratory failure

Pulmonary gas exchange fails to maintain normal arterial

oxygen and carbon dioxide levels. Its classification into

types I and II is defined by the absence or presence of

hypercapnia (raised PaCO

2

).

Pathophysiology

When disease impairs ventilation of part of a lung (e.g.

in asthma or pneumonia), perfusion of that region

results in hypoxic and CO

2

-laden blood entering the

pulmonary veins. Increased ventilation of neighbouring

regions of normal lung can increase CO

2

excretion,

correcting arterial CO

2

to normal, but cannot augment

oxygen uptake because the haemoglobin flowing

through these regions is already fully saturated.

Admixture of blood from the underventilated and normal

regions thus results in hypoxia with normocapnia, which is

called ‘type I respiratory failure’.

Diseases causing this include all those that impair

ventilation locally with sparing of other .

Arterial hypoxia with hypercapnia

(

type II

respiratory

failure) is seen in

conditions that cause generalised,

severe ventilation–perfusion mismatch, leaving insufficient

normal lung to correct PaCO

2

, or a disease that

reduces total ventilation. The latter includes not just

diseases of the lung but also disorders affecting any

part of the neuromuscular mechanism of ventilation.

How to interpret blood gas abnormalities in

respiratory failure

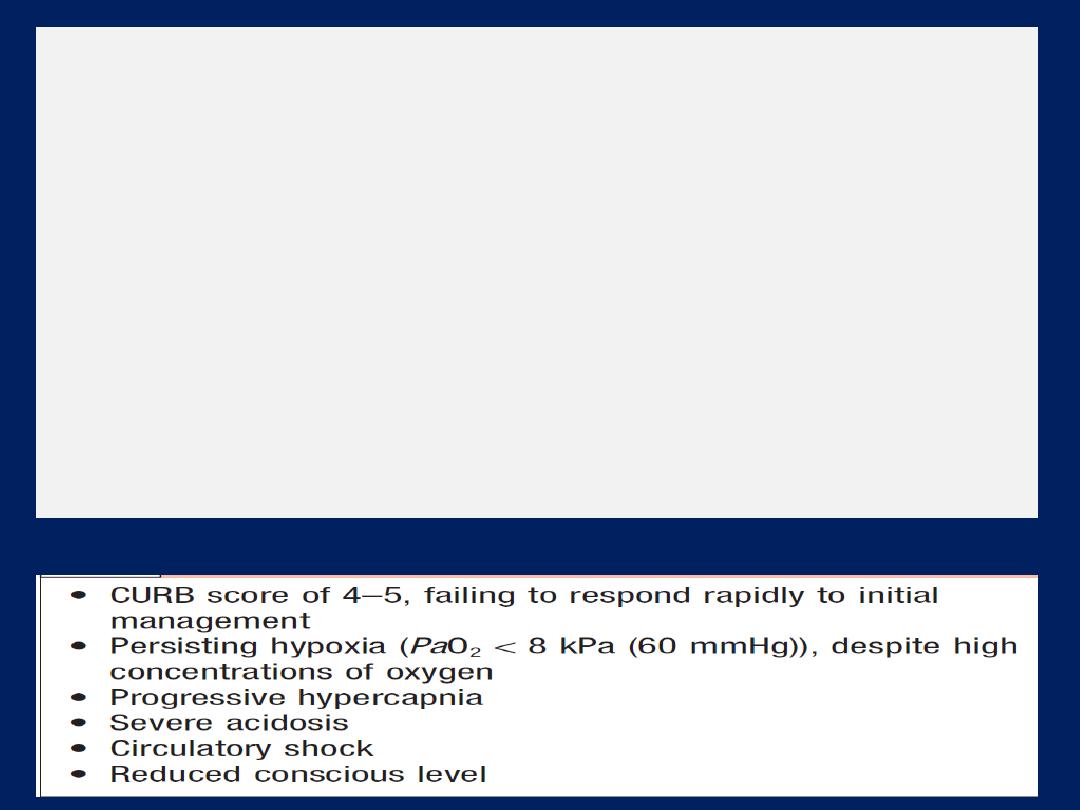

Management of acute respiratory failure

Prompt diagnosis and management of the underlying

cause is crucial. In type I, high concentrations of oxygen

(40–60% by mask) will usually relieve hypoxia by

increasing the alveolar PO

2

in poorly ventilated lung units.

Occasionally, however (e.g. severe pneumonia affecting

several lobes), mechanical ventilation may be needed to

relieve hypoxia. Patients who need high concentrations of

oxygen for more than a few hours should receive

humidified oxygen. Acute type II is an emergency. It is

useful to distinguish between patients with high ventilatory

drive (rapid respiratory rate and accessory muscle

recruitment) who cannot move sufficient air, and those with

reduced or inadequate respiratory effort.

In the former, particularly if inspiratory stridor is present,

acute upper airway obstruction from foreign body

inhalation or laryngeal obstruction (angioedema,

carcinoma or vocal cord paralysis) must be considered, as

the Heimlich manoeuvre , immediate intubation or

emergency tracheostomy may be life-saving.

More commonly, the problem is in the lungs, with

severe COPD or asthma, acute respiratory distress

syndrome (ARDS) arising from a variety of insults or

occasionally tension pneumothorax . In all such cases, high

concentration (e.g. 60%) oxygen should be administered,

pending a rapid examination of the respiratory

system and measurement of arterial blood gases.

Patients with tension pneumothorax, and air should be

aspirated from the pleural space and a chest drain

inserted as soon as possible. Patients with generalised

wheeze, scanty breath sounds bilaterally or a history of

asthma or COPD should be treated with nebulised

salbutamol 2.5 mg with oxygen, repeated until

bronchospasm is relieved. Failure to respond to initial

treatment, declining conscious level and worsening

respiratory acidosis (H+ > 50 nmol/L (pH < 7.3), PaCO

2

> 6.6 kPa (50 mmHg)) on blood gases are all indications

that supported ventilation is required .

A small percentage of patients with severe COPD and

type II respiratory failure develop abnormal

tolerance to raised PaCO

2

and may become dependent

on hypoxic drive to breathe. In these patients only, lower

concentrations of oxygen (

24–28% by Venturi mask)

should be

used to avoid precipitating worsening respiratory

depression . Regular monitoring of arterial blood gases is

important. Patients with acute type II failure who have

reduced drive or conscious level may be suffering from

sedative poisoning, CO

2

narcosis or a primary failure of

neurological drive

(e.g. following intracerebral haemorrhage or

head injury). History from a witness may be invaluable, and reversal

of specific drugs with (for example) opiate antagonists is

occasionally successful, but should not delay intubation and

supported mechanical ventilation.

Chronic and ‘acute on chronic’ type II respiratory failure

The most common cause of chronic type II respiratory

failure is severe COPD. Although PaCO

2

may be

persistently raised, there is no persisting acidaemia

because the kidneys retain bicarbonate, correcting arterial

pH to normal. This

‘compensated’

pattern, which may also

occur in chronic neuromuscular disease or kyphoscoliosis,

is maintained until there is a further acute illness such as an

exacerbation of COPD which precipitates an episode of

‘acute on chronic’ respiratory failure, with acidaemia and

initial respiratory distress followed by drowsiness and

eventually coma.

These patients have lost their chemo-sensitivity to elevated

PaCO

2

, and so they may paradoxically depend on

hypoxia for respiratory drive, and are at risk of respiratory

depression if given high concentrations of oxygen

– for example, during ambulance transfers or in emergency

departments. Moreover, in contrast to acute severe

asthma, some patients with ‘acute on chronic’ type II

due to COPD may not be distressed, despite being critically

ill with severe hypoxaemia, hypercapnia and acidaemia.

Physical signs of CO

2

retention (confusion, flapping

tremor, bounding pulses , warm periphery and so on) can

be helpful if present, they may not be, so arterial blood

gases are mandatory in the assessment of initial severity

and response to treatment.

Management

The principal aims of treatment in acute on chronic type

II

respiratory failure are to achieve

a safe PaO

2

(> 7.0

kPa (52 mmHg))

without

increasing PaCO

2

and acidosis,

while identifying and treating the precipitating condition.

In these patients, it is not necessary to achieve a

normal PaO

2

; even a small increase will often have

a greatly beneficial effect on tissue oxygen delivery,

since their PaO

2

values are often on the steep part of

the oxygen saturation curve .The risks of worsening

hypercapnia and coma must be balanced against

those of severe hypoxaemia, which include potentially

fatal arrhythmias or severe cerebral complications.

Patients who are conscious and have adequate

respiratory drive may benefit from non-invasive

ventilation (NIV), which has been shown to reduce the need

for intubation and shorten hospital stay. Patients who are

drowsy and have low respiratory drive require an urgent

decision regarding intubation and ventilation, as this is

likely to be the only effective treatment, even though

weaning off the ventilator may be difficult in severe

disease. Respiratory stimulant drugs, such as doxapram,

tend to cause unacceptable distress due to increased

dyspnoea, and have been largely superseded by

intubation and mechanical ventilation in patients with CO

2

narcosis, as they provide only minor and transient

improvements in arterial blood gases.

Initial assessment

Patient may not appear distressed,

despite being critically ill

• Conscious level (response to

commands, ability to cough)

• CO

2

retention (warm periphery,

bounding pulses, flapping tremor)

• Airways obstruction (wheeze,

prolonged expiration, hyperinflation,

intercostal indrawing, pursed lips)

• Cor pulmonale (peripheral oedema,

raised JVP, hepatomegaly, ascites)

• Background functional status and

quality of life

• Signs of precipitating cause

Investigations

• Arterial blood gases (severity of

hypoxaemia, hypercapnia,

acidaemia, bicarbonate)

• Chest X-ray

Management

• Maintenance of airway

• Treatment of specific precipitating cause

• Frequent physiotherapy ± pharyngeal

suction

• Nebulised bronchodilators

• Controlled oxygen therapy

Start with 24% Venturi mask

Aim for a PaO

2

> 7 kPa (52 mmHg)

(a

PaO

2

< 5 (37 mmHg) is dangerous)

• Antibiotics if evidence of infection

• Diuretics if evidence of fluid overload

Progress

• If PaCO

2

continues to rise or a safe PaO

2

cannot be achieved without severe

hypercapnia and acidaemia, mechanical

ventilatory support may be required

Assessment and management of ‘acute on chronic’ type II

respiratory failure

Home ventilation for chronic respiratory failure

NIV is of great value in spinal deformity, neuromuscular

disease , central alveolar hypoventilation and cystic

fibrosis. Morning headache (due to elevated PaCO

2

) and

fatigue are common symptoms. In the initial stages,

ventilation is insufficient for metabolic needs only during

sleep, when there is a physiological decline in ventilator

drive. Over time, however, CO

2

retention becomes

chronic, with renal compensation of acidosis.

Treatment by home-based NIV overnight is often

sufficient to restore the daytime PCO

2

to normal, and to

relieve fatigue and headache. In advanced disease ,

daytime NIV may also be required.

Lung transplantation

Established treatment for carefully selected patients with

advanced lung disease unresponsive to medical treatment .

Single-lung

transplantation may be used for selected for

advanced emphysema or lung fibrosis. This is

contraindicated

in chronic bilateral pulmonary infection,

such as cystic fibrosis and bronchiectasis, because the

transplanted lung is vulnerable to cross-infection in the

context of post-transplant immunosuppression and for these

individuals

bilateral-lung

transplantation is the standard

procedure.

Combined heart–lung

transplantation is still

occasionally needed for advanced congenital heart disease

such as Eisenmenger’s syndrome, and is preferred by some

surgeons for the treatment of primary pulmonary

hypertension unresponsive to medical therapy.

The prognosis is improving steadily with modern

immunosuppressive drugs: over 50% 10-year survival in

some UK centres. However, chronic rejection resulting in

obliterative bronchiolitis continues to afflict some recipients.

Corticosteroids are used to manage acute rejection, but

drugs that inhibit cell-mediated

immunity specifically, such

as ciclosporin, mycophenolate and tacrolimus are

used to prevent chronic rejection.

Azithromycin, statins and total lymphoid irradiation are

employed to treat obliterative bronchiolitis, but late organ

failure remains a significant problem. The major factor

limiting is the shortage of donor lungs. To improve organ

availability, techniques to recondition the lungs in vitro after

removal from the donor are being developed.

OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASES

Asthma

A chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways, in which

many cells and cellular elements play a role. The chronic

inflammation is associated with airway hyper-

responsiveness that leads to recurrent episodes of

wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness and coughing,

particularly at night and in the early morning. Associated

with wide spread but variable airflow obstruction that is

often reversible, spontaneously or with treatment. Although

the development and course of the disease, and the

response to treatment, are influenced by genetic

determinants, the rapid rise in prevalence implies that

environmental factors are critically important.

To date, studies have explored the potential role of indoor

and outdoor allergens, microbial exposure, diet, vitamins,

breastfeeding, tobacco smoke, air pollution and obesity

but no clear consensus has emerged.

Pathophysiology

Airway hyper-reactivity (AHR) –in response to triggers

that have little or no effect in normal individuals – is

integral to the diagnosis of asthma. The relationship

between atopy (the propensity to produce IgE) and asthma

is well established, and in many individuals there is a clear

relationship between sensitisation and allergen exposure, as

demonstrated by skin prick reactivity or elevated serum

specific IgE. Common examples of allergens include house

dust mites, pets such as cats and dogs, pests such as

cockroaches, and fungi.

Inhalation of an allergen into the airway is followed by an

early and late-phase bronchoconstrictor response .

Allergic mechanisms are also implicated in some cases of

occupational asthma . In cases of aspirin-sensitive asthma,

the ingestion of salicylates results in inhibition of the cyclo-

oxygenase enzymes, preferentially shunting the metabolism

of arachidonic acid through lipoxygenase pathway with

resultant production of asthmogenic cysteinyl

leukotrienes

. In exercise-induced asthma, hyperventilation

results in water and heat loss from the respiratory mucosa,

which triggers mediator release. In persistent asthma, a

chronic and complex inflammatory response ensues, influx

of inflammatory cells, transformation of airway structural

cells, and

secretion of cytokines, chemokines and growth factors.

Although asthma is predominantly characterised by airway

eosinophilia, neutrophilic inflammation predominates in

some patients, while, in others, scant inflammation is

observed: so-called ‘pauci-granulocytic’ asthma.

With increasing severity and chronicity, remodelling of the

airway may occur, leading to fibrosis of the airway wall,

fixed narrowing of the airway and a reduced response to

bronchodilator medication.

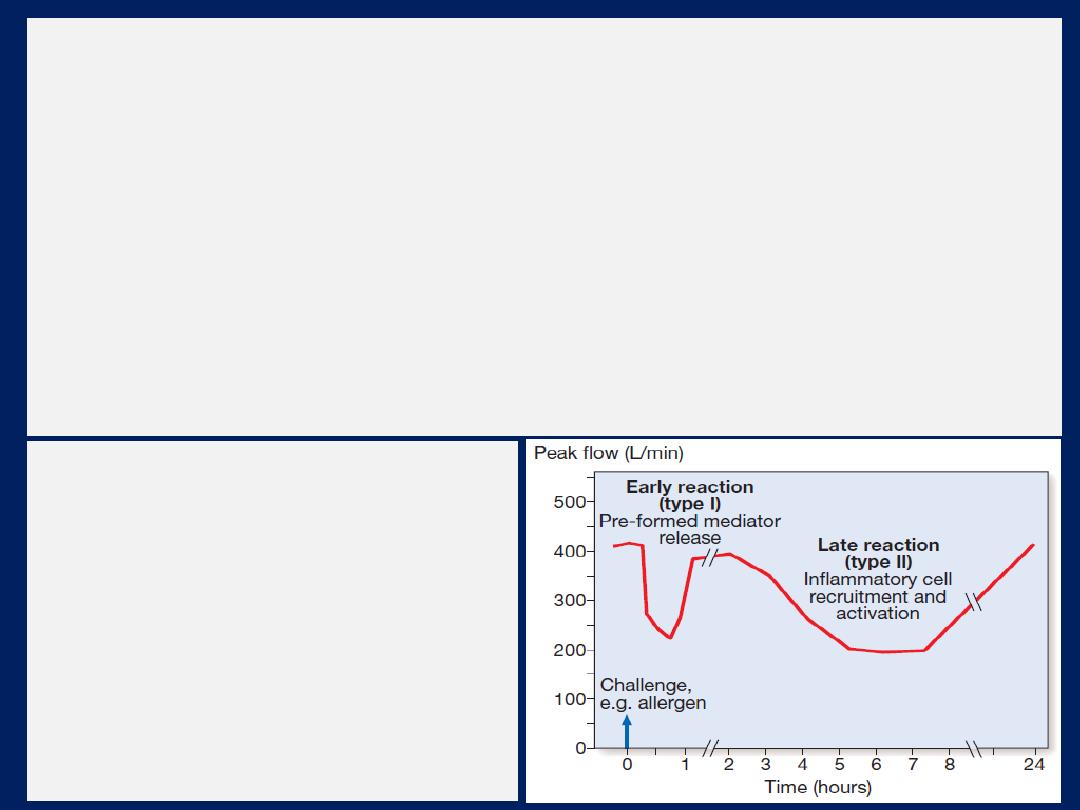

Changes in peak flow

following allergen challenge.

A similar

biphasic

response is

observed following a variety of

different challenges.

Occasionally, an isolated late

response is seen with no early

reaction.

Clinical features

Typical symptoms include recurrent episodes of wheezing,

chest tightness, breathlessness and cough. Asthma is

commonly mistaken for a cold or chest infection .

Classical precipitants include exercise, particularly in cold

weather, exposure to airborne allergens or pollutants,

and viral upper respiratory tract infections. An inspection

for nasal polyps and eczema should be performed. Rarely,

vasculitic rash may suggest Churg–Strauss syndrome .

Patients with mild intermittent asthma are usually

asymptomatic between exacerbations. Individuals with

persistent asthma report ongoing breathlessness and

wheeze, with symptoms fluctuating over the course of one

day, or from day to day or month to month.

Asthma characteristically displays a diurnal pattern,

with symptoms and lung function being

worse in the

early morning.

Particularly when poorly controlled,

symptoms such as cough and wheeze disturb sleep and

have led to the term ‘nocturnal asthma’. Cough may be

the dominant symptom in some, and the lack of wheeze or

breathlessness may lead to a delay in diagnosis ‘cough-

variant asthma’. Some patients with asthma have a similar

inflammatory response in the upper airway. Careful

enquiry should be made as to a history of sinusitis, sinus

headache, a blocked or runny nose, and loss of sense of

smell. Particular enquiry should be made about potential

allergens, such as exposure to a pet cat, guinea pig,

rabbit or horse, pest infestation, exposure to moulds.

In some circumstances, the appearance of asthma is

triggered by medications. Beta-blockers, even when

administered topically as eye drops, may induce

bronchospasm, as may aspirin and other NSAIDs. The

classical aspirin sensitive patient is female and presents in

middle age with asthma, rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps.

Aspirin sensitive patients may also report symptoms

following alcohol (in particular, white wine) and foods

containing salicylates. Other medications implicated include

the oral contraceptive pill, cholinergic agents and

prostaglandin F2α.

Betel nuts contain arecoline, which is

structurally similar to methacholine and can aggravate asthma.

Aminority of patients develop severe form of asthma, and this

appears to be more common in women. Allergic triggers are less

important and airway neutrophilia predominates.

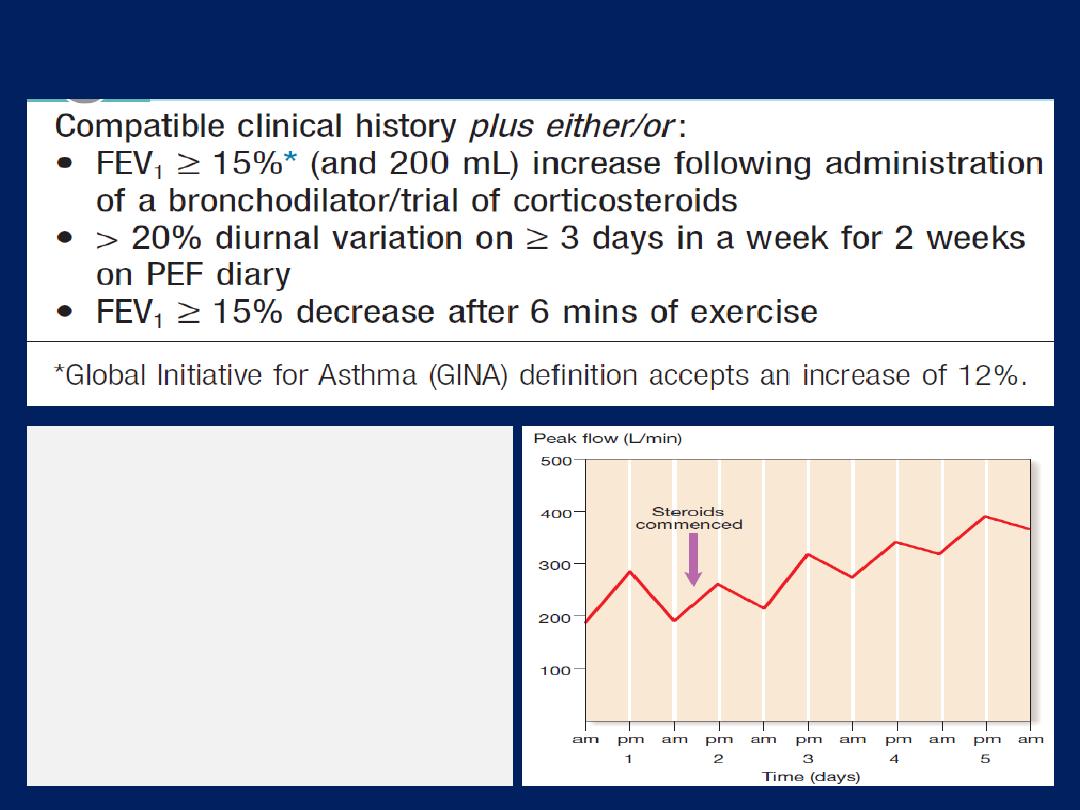

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is predominantly clinical. Supportive

evidence is provided by the demonstration of variable

airflow obstruction, preferably by using spirometry to

measure FEV

1

and VC. This identifies the obstructive

defect, defines its severity, and provides a baseline for

bronchodilator reversibility . If spirometry is not available,

a peak flow meter may be used. Patients should be

instructed to record peak flow readings after rising in the

morning and before retiring in the evening.

A diurnal variation in PEF of more than 20% (the

lowest values typically being recorded in the morning) is

considered diagnostic, and the magnitude of variability

provides some indication of disease severity .

A trial of corticosteroids (e.g. 30 mg daily for 2 weeks)

may be useful in establishing the diagnosis, by

demonstrating an improvement in either FEV

1

or PEF.

It is not uncommon for patients whose symptoms

are suggestive of asthma to have normal lung function.

In these circumstances, the demonstration of AHR by

challenge tests may be useful to confirm the diagnosis.

AHR is sensitive but non-specific:

it has a

high negative predictive value

but positive results

may be seen in other conditions, such as COPD,

bronchiectasis and cystic fibrosis. When symptoms are

predominantly related to exercise, an exercise challenge

may be followed by a drop in lung function.

• Measurement of allergic status:

the presence of atopy

may be demonstrated by skin prick tests. Measurement

of total and allergen-specific IgE. Blood eosinophilia.

• Radiological examination:

chest X-ray appearances are

often normal or show hyperinflation of lung fields.

Lobar collapse may be seen if mucus occludes a large

bronchus and, if accompanied by the presence of flitting

infiltrates, may suggest that asthma has been complicated

by allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis .

• Assessment of eosinophilic airway inflammation:

an induced sputum eosinophil count of greater than 2% or

exhaled breath nitric oxide concentration (FENO) may

support the diagnosis but is non-specific.

How to make a diagnosis of asthma

Serial recordings PEF

Note the sharp overnight fall

(

morning dip

) and subsequent

rise during the day. Following

the introduction of

corticosteroids, there is an

improvement in PEF rate and

loss of morning dipping.

Management

The goal of treatment should be to obtain and maintain

complete control , but aims may be modified according to

the circumstances and the patient. Unfortunately, majority

of individuals with asthma report suboptimal control.

Whenever possible, patients should be encouraged to

take responsibility for managing their own disease.

A full explanation of the nature of the condition, the

relationship between symptoms and inflammation and, if

appropriate, the use of PEF.

Avoidance of aggravating factors

This is particularly important in occupational asthma but

also be relevant in atopic, removing or reducing exposure

to antigens, such as a pet, may effect improvement.

House dust mite exposure may be minimised by

replacing carpets with

floorboards

and using mite

impermeable bedding

. Many patients are sensitised to

several ubiquitous aeroallergens, making avoidance

strategies largely impractical.

Measures to reduce fungal exposure and eliminate

cockroaches

may be applicable and medications known to

precipitate or aggravate asthma should be avoided.

Smoking

cessation is important, as not only encourages

sensitisation, but also induces a relative corticosteroid

resistance in the airway.

The stepwise approach to the management of asthma

Step 1:

Occasional use of inhaled short-acting β

2

-

adrenoreceptor agonist bronchodilators

For patients with mild intermittent asthma (symptoms

less than once a week for 3 months and fewer than two

nocturnal episodes per month), it is usually sufficient to

prescribe an inhaled short-acting β

2

-agonist, such as

salbutamol or terbutaline, to be used as required.

Metered-dose inhaler remains the most widely prescribed.

Step 2:

Introduction of regular preventer therapy

Regular anti-inflammatory therapy (inhaled corticosteroids

(ICS), beclometasone, budesonide , fluticasone or

ciclesonide) started in addition to inhaled β

2

-agonists taken

on an as-required basis for any patient who:

• has experienced an exacerbation in the last 2 years

• uses inhaled β2-agonists three times a week or more

• reports symptoms three times a week or more

• is awakened by asthma one night per week.

For adults, a reasonable starting dose is 400 μg

beclometasone dipropionate (BDP) or per day although

higher doses may be required in smokers. Alternative less

effective preventive agents, chromones, leukotriene receptor

antagonists, and theophyllines.

Step 3:

Add-on therapy

If a patient remains poorly controlled, a thorough review

should be undertaken of adherence, inhaler technique and

ongoing exposure to modifiable aggravating factors.

A further increase in the dose of ICS may benefit some

patients but, in general, add-on therapy should be

considered in adults taking 800 μg/day BDP

(or equivalent).

Long-acting β

2

-agonists (LABAs), such as salmeterol and

formoterol

(duration of action of at least 12 hours),

represent the first

choice of add-on therapy. They have consistently been

demonstrated to improve asthma control and to reduce the

frequency and severity of exacerbations when compared

to increasing the dose of ICS alone. Fixed combination

inhalers of ICS and LABAs have been developed; more

convenient, increase compliance and prevent using a LABA

as monotherapy – the latter may be accompanied by an

increased risk of life-threatening attacks or asthma death.

The onset of action of formoterol is similar to that of

salbutamol such that, in carefully selected patients, a fixed

combination of budesonide and formoterol may be used as

both rescue and maintenance therapy.

Oral leukotriene receptor antagonists (e.g. montelukast

10 mg

daily

) are generally less effective than LABA as add-on

therapy, but may facilitate a reduction in the dose of ICS

and control exacerbations. Oral theophyllines may be

considered in some patients but their unpredictable

metabolism, propensity for drug interactions and prominent

side-effects limit their widespread use.

Step 4:

Poor control on moderate dose of inhaled steroid

and add-on therapy: addition of a fourth drug

In adults, the dose of ICS may be increased to 2000 μg

BDP/BUD (or equivalent) daily. A nasal corticosteroid

preparation should be used in patients with prominent

upper airway symptoms.

Oral therapy with leukotriene receptor antagonists,

theophyllines or a slow-release β

2

- agonist may be

considered. If the trial of add-on therapy is ineffective, it

should be discontinued. Oral itraconazole may be

contemplated in patients with allergic bronchopulmonary

aspergillosis.

Step 5:

Continuous or frequent use of oral steroids

At this stage, prednisolone therapy (usually administered

as a single daily dose in the morning) should be

prescribed in the lowest amount necessary to control

symptoms. Patients on long-term corticosteroid tablets

(> 3 months) or receiving more than three or four courses

per year will be at risk of systemic side-effects .

Osteoporosis can be prevented in this group by giving

bisphosphonates . In atopic patients, omalizumab, a

monoclonal antibody directed against IgE, may prove

helpful in reducing symptoms and allowing a reduction in

the prednisolone dose. Steroid-sparing therapies, such as

methotrexate, ciclosporin or oral gold, may be considered.

Step-down therapy

Once asthma control is established, the dose of inhaled

(or oral) corticosteroid should be titrated to the lowest

dose at which effective control of asthma is maintained.

Decreasing the dose of ICS by around 25–50% every 3

months is a reasonable strategy for most patients.

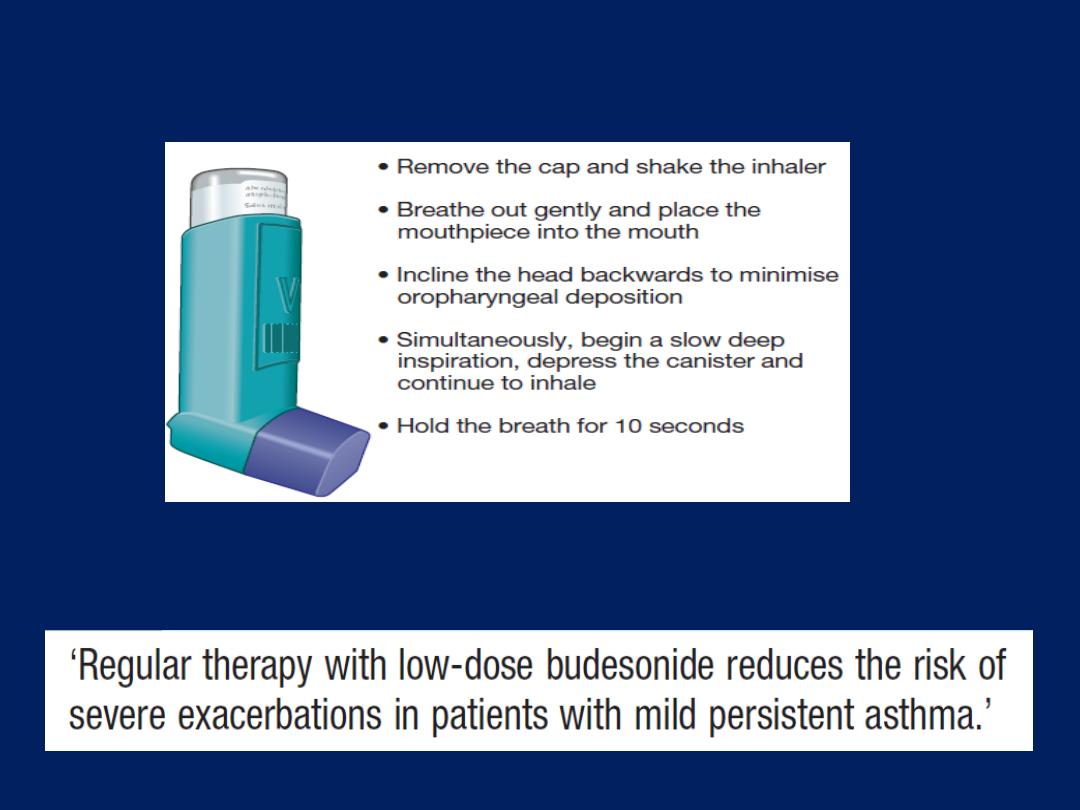

How to use a metered-dose inhaler.

Inhaled corticosteroids and asthma

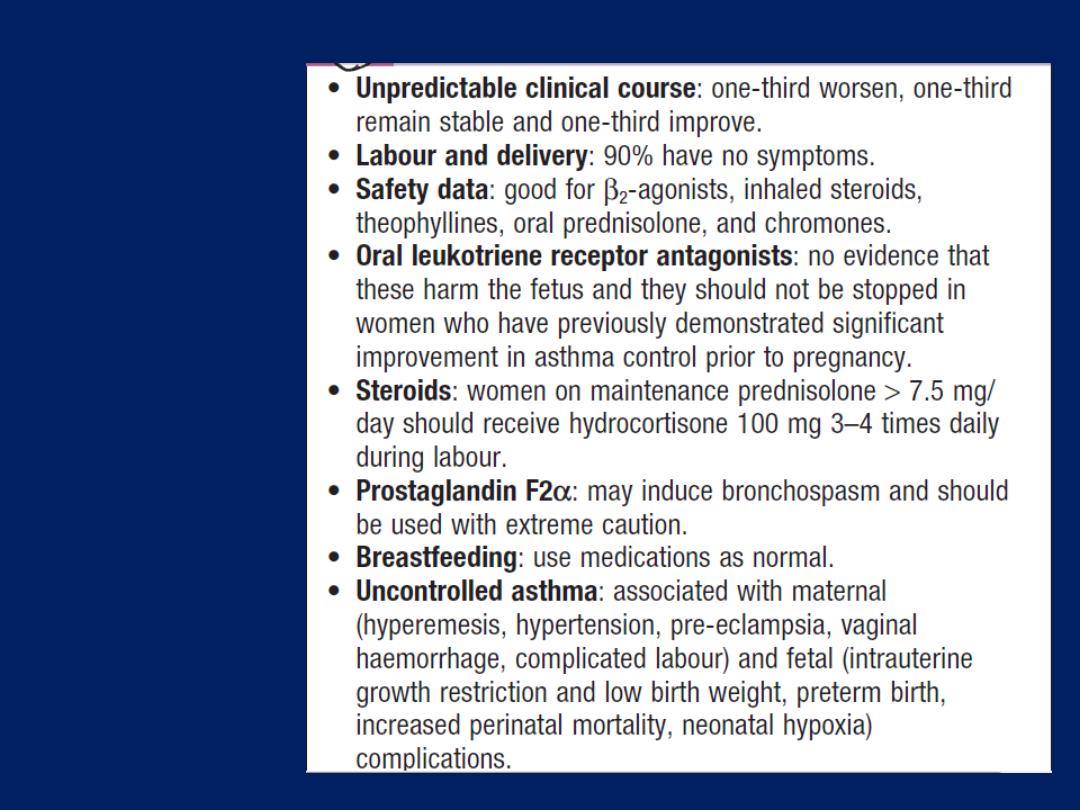

Asthma in

pregnancy

Exacerbations of asthma

The course may be punctuated by exacerbations.

Exacerbations are most commonly precipitated by viral

infections, but moulds , pollens and air pollution are also

implicated. Most attacks are characterised by a gradual

deterioration over several hours to days but some appear

to occur with little or no warning: so-called brittle asthma.

Management of mild to moderate exacerbations

Doubling the dose of ICS does not prevent an impending

exacerbation. Short courses of ‘rescue’ oral corticosteroids

(prednisolone 30–60 mg daily)

are often required to regain control.

Tapering to withdraw treatment is not necessary, unless

given for more than 3 weeks.

Indications for ‘rescue’ courses include:

• symptoms and PEF progressively worsening day by day,

with a fall of PEF < 60% of the patient’s personal best

recording

• onset or worsening of sleep disturbance by asthma

• persistence of morning symptoms until midday

• progressively diminishing response to an inhaled

bronchodilator

• symptoms sufficiently severe to require treatment with

nebulised or injected bronchodilators.

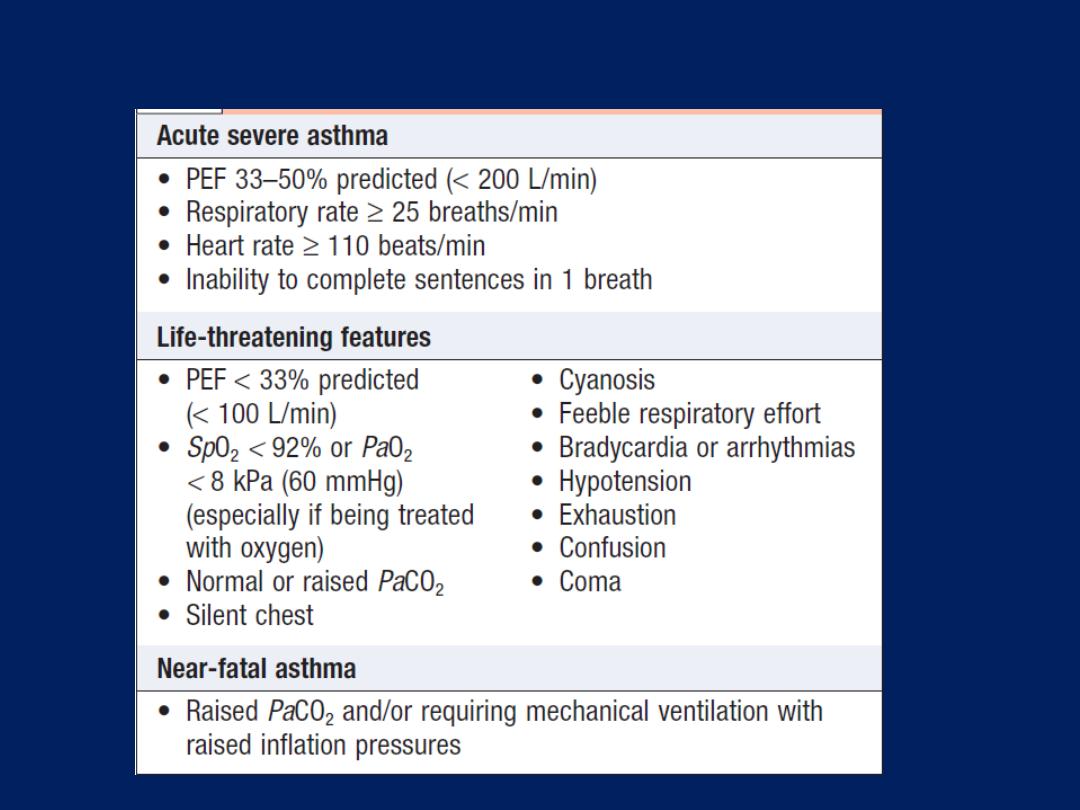

Management of acute severe asthma

Measurement of PEF is mandatory, unless the patient is too

ill to cooperate.

Arterial blood gas analysis is essential to determine the

PaCO

2

, a normal or elevated level being particularly

dangerous. A chest X-ray is not immediately necessary,

unless pneumothorax is suspected.

Treatment includes the following measures:

• Oxygen.

High concentrations (humidified if possible)

should be administered to maintain the oxygen saturation

above 92% in adults. Failure to achieve appropriate

oxygenation is an indication for assisted ventilation.

• High doses of inhaled bronchodilators.

Short-acting

β

2

-agonists are the agent of choice.

In hospital, they are most conveniently given via a

nebuliser driven by oxygen, but delivery of multiple

doses of salbutamol via a metered-dose inhaler through a

spacer device provides equivalent bronchodilatation and

can be used in primary care. Ipratropium bromide

provides further bronchodilator therapy and added to

salbutamol in acute severe or life-threatening attacks.

• Systemic corticosteroids.

These reduce the inflammatory

response and hasten the resolution of an exacerbation.

They can usually be administered orally as prednisolone,

but IV hydrocortisone in patients who are vomiting.

Potassium supplements may be necessary, as repeated

doses of salbutamol can lower serum potassium.

If patients fail to improve, a number of further options

may be considered. Intravenous magnesium may

provide additional bronchodilatation in patients whose

presenting PEF is below 30% predicted.

Some patients appear to benefit from the use of

intravenous aminophylline but cardiac monitoring is

recommended.

PEF should be recorded every 15–30 minutes and

then every 4–6 hours. Pulse oximetry should ensure that

SaO

2

remains above 92%, but repeat arterial blood

gases are necessary if the initial PaCO

2

measurements

were normal or raised, the PaO

2

was below 8 kPa (60

mmHg), or the patient deteriorates.

Immediate assessment of acute severe asthma

Prognosis

The outcome from acute severe asthma is generally good.

Death is fortunately rare. Failure to recognise the severity,

contributes to delay in delivering appropriate therapy and

to under-treatment.

Prior to discharge, patients should be stable on discharge

medication

(nebulised therapy should have been discontinued for at least 24

hours)

and the PEF should have reached 75% of predicted.

The acute attack should prompt a look for and avoidance

of any trigger factors, the delivery of asthma education

and the provision of a written self-management plan.

The patient should be offered an appointment with a GP

or asthma nurse within 2 working days of discharge, and

follow-up at a specialist hospital clinic within a month.

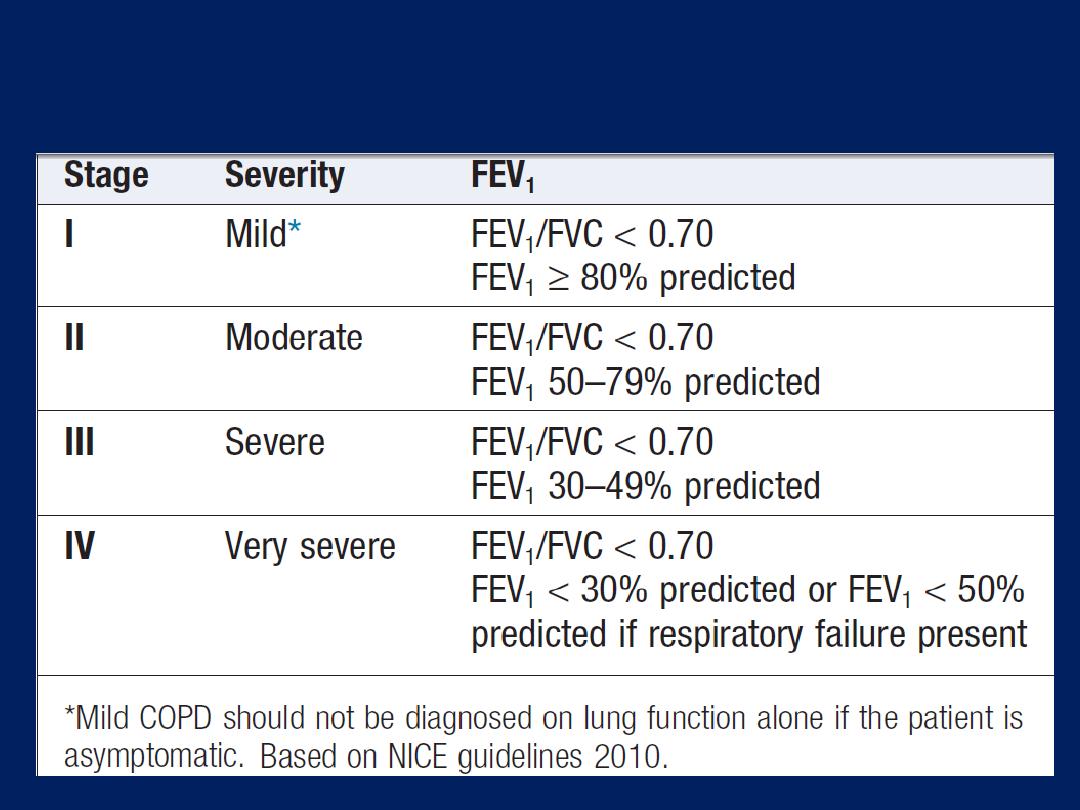

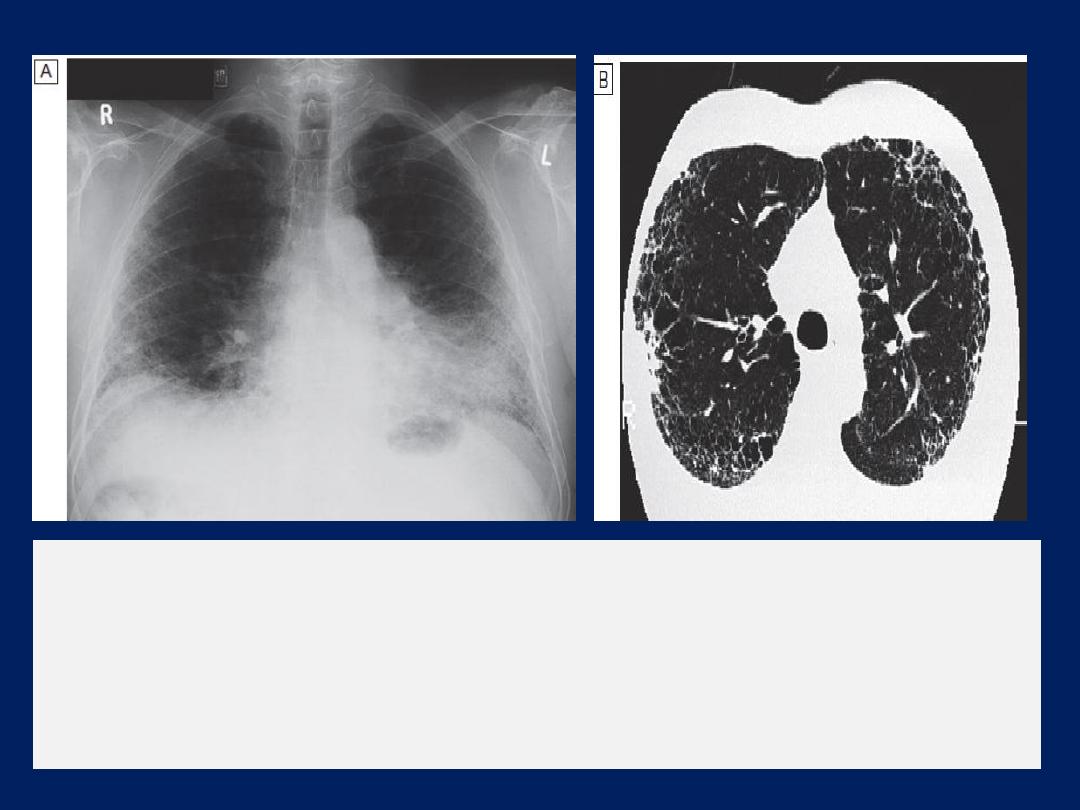

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

COPD is a preventable and treatable disease

characterised by persistent airflow limitation that is

usually progressive, and associated with an enhanced

chronic inflammatory response in the airways and the lung

to noxious particles or gases.

Exacerbations and comorbidities contribute to

the overall severity in individual patients. Related

diagnoses include

chronic bronchitis

(cough and sputum

on most days for at least 3 months, in each of 2

consecutive years) and

emphysema

(abnormal

permanent enlargement of the airspaces distal to the

terminal bronchioles, accompanied by destruction of

their walls and without obvious fibrosis).

Extra-pulmonary effects

Weight loss and skeletal muscle dysfunction. Commonly

associated comorbid conditions include cardiovascular,

cerebrovascular disease, the metabolic syndrome,

osteoporosis, depression and lung cancer.

Epidemiology and aetiology

The prevalence is directly related to the prevalence of

tobacco smoking. By 2020, it is forecast to represent the

third most important cause of death worldwide. Cigarette

smoking represents the most significant risk factor, the risk

relates to the amount and the duration of smoking. It is

unusual to develop COPD with <10 pack years

(1 pack year =

20 cigarettes/day/year)

and not all smokers develop the condition,

suggesting that individual susceptibility factors are important.

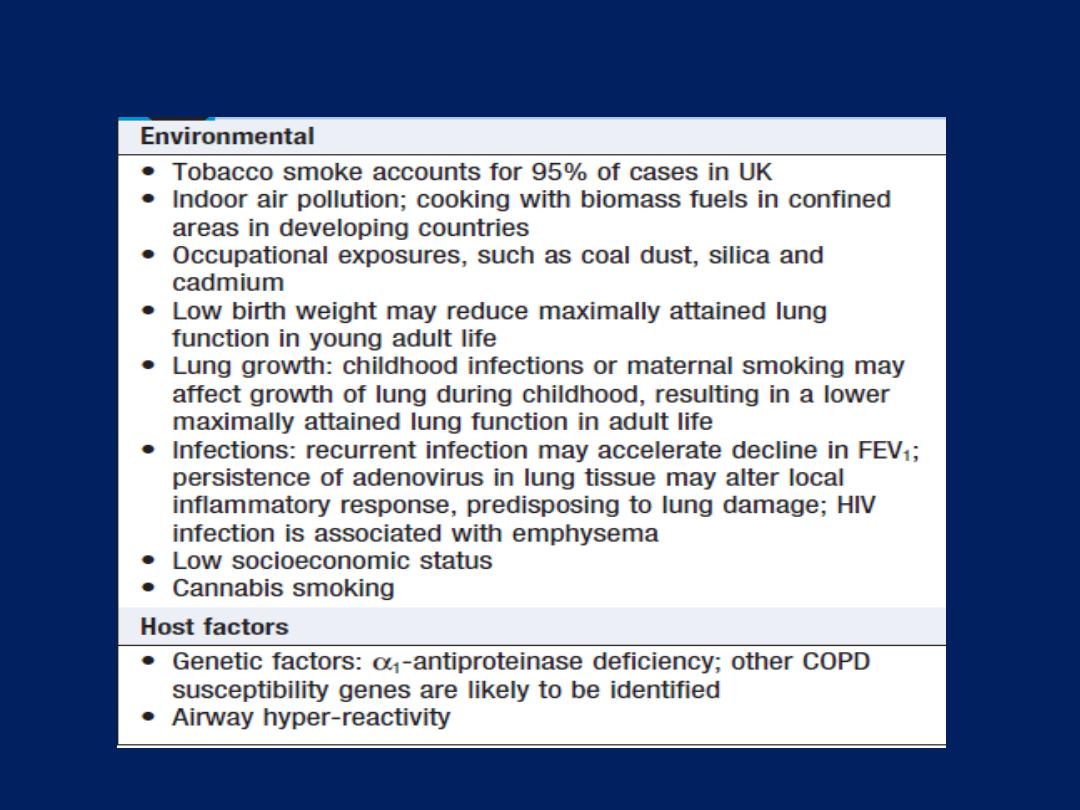

Risk factors for development of COPD

Pathophysiology

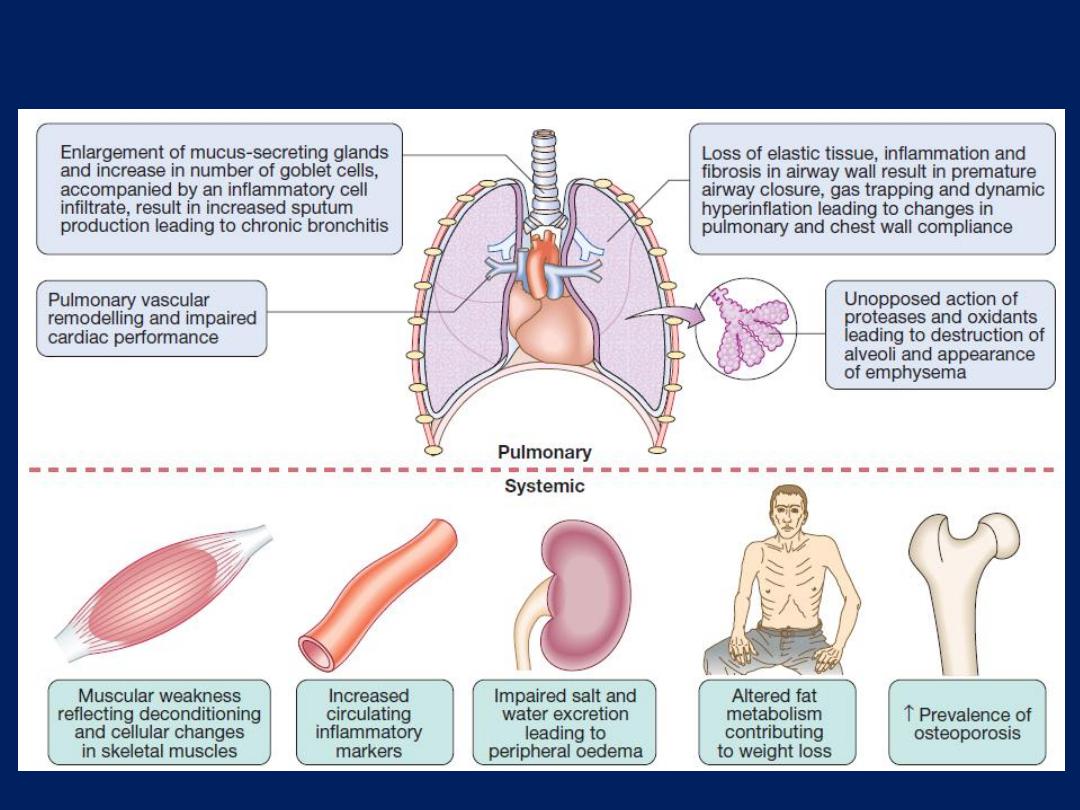

COPD has both pulmonary and systemic components.

The presence of airflow limitation, combined with

premature airway closure, leads to gas trapping and

hyperinflation, reducing pulmonary and chest wall

compliance. Pulmonary hyperinflation also flattens the

diaphragmatic muscles and leads to an increasingly

horizontal alignment of the intercostal muscles, placing the

respiratory muscles at a mechanical disadvantage. The

work of breathing is therefore markedly increased, first on

exercise, when the time for expiration is further shortened,

but then, as the disease advances, at rest.

Emphysema , classified by the pattern of the enlarged

airspaces as centriacinar, panacinar or paraseptal.

The pulmonary and systemic features of COPD.

Clinical features

COPD should be suspected in any patient > 40 years