Hussien Mohammed Jumaah

CABM

Lecturer in internal medicine

Mosul College of Medicine

2016

learning-topics

CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

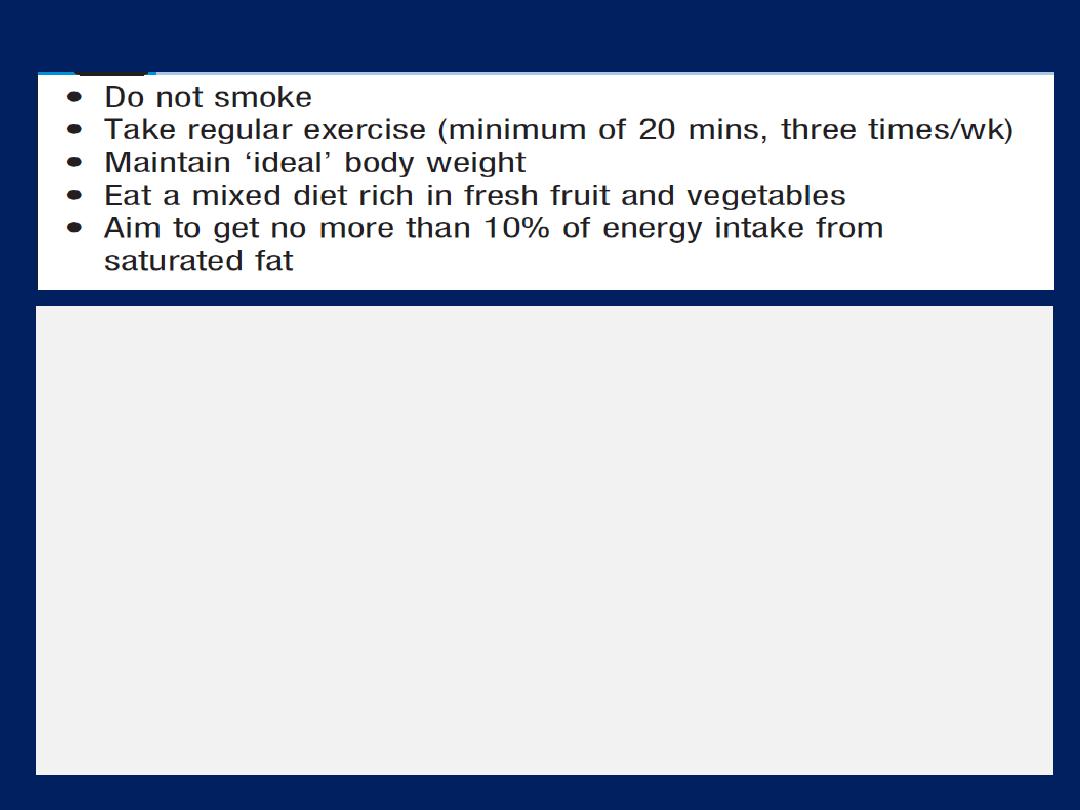

In the UK, one-third of men and one-quarter of women

will

die

as a result of ischaemic heart disease(IHD).

In 20% of adults, a patent foramen ovale is Found. The

atria and ventricles are separated by the

annulus

fibrosus

, which forms the skeleton for the atrioventricular

(AV) valves and which

electrically insulates

the atria from

the ventricles.

The right ventricle (RV) is roughly triangular in shape The

RV sits anterior to, and to the right of, the left ventricle

(LV). The LV is more conical in shape and in cross-section is

nearly circular.

The LV myocardium is normally around 10 mm thick

(c.f. RV of 2–3 mm) because

it pumps blood at a higher pressure.

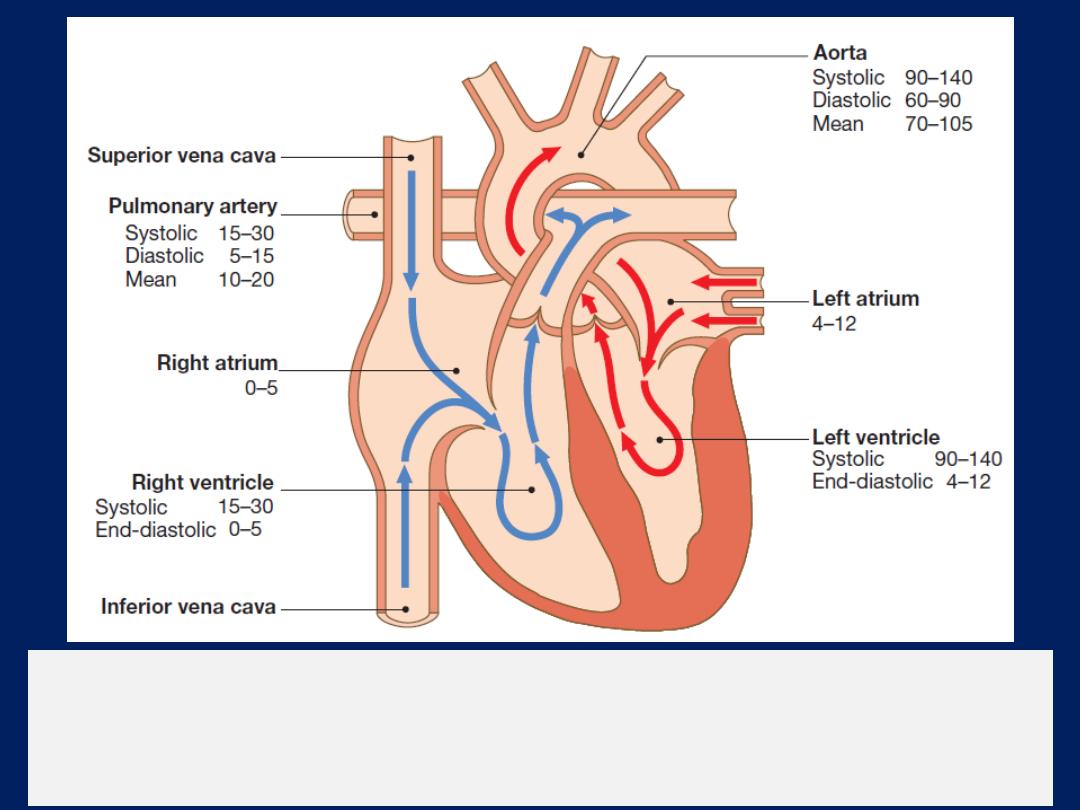

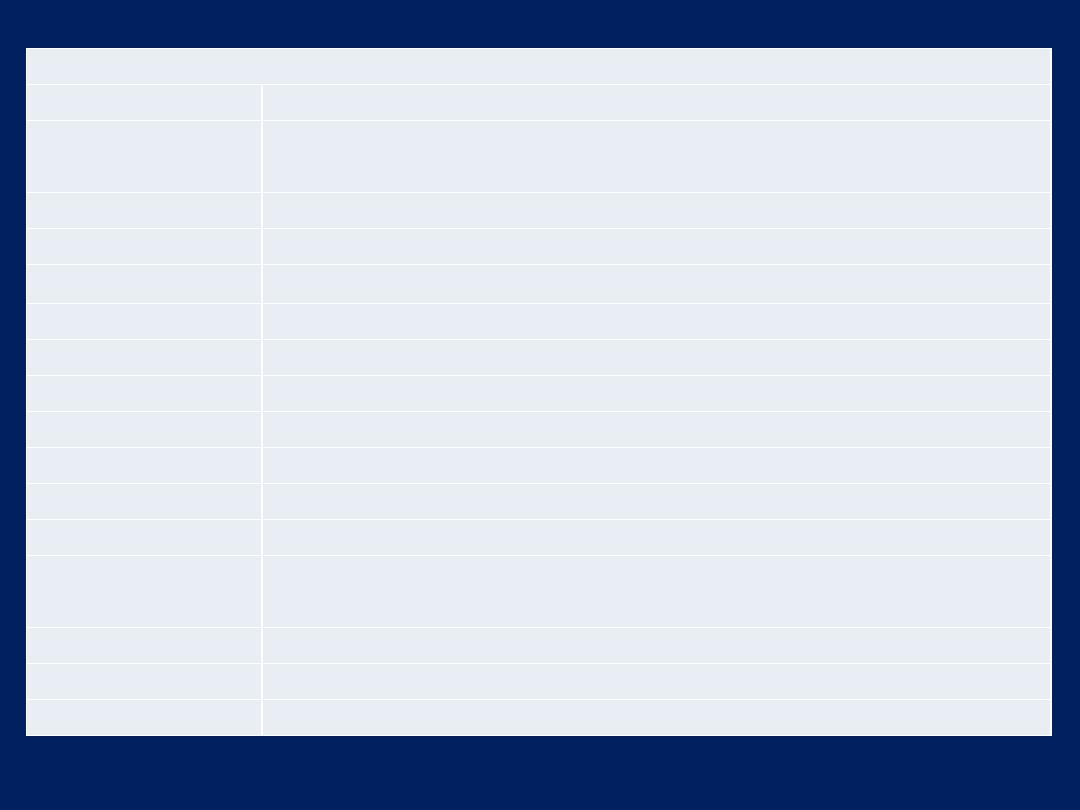

Direction of blood flow through the heart.

The blue arrows show deoxygenated

blood moving through the right heart to the lungs. The red

arrows show oxygenated blood moving from the lungs to the systemic circulation.

The normal pressures are shown for each chamber in mmHg.

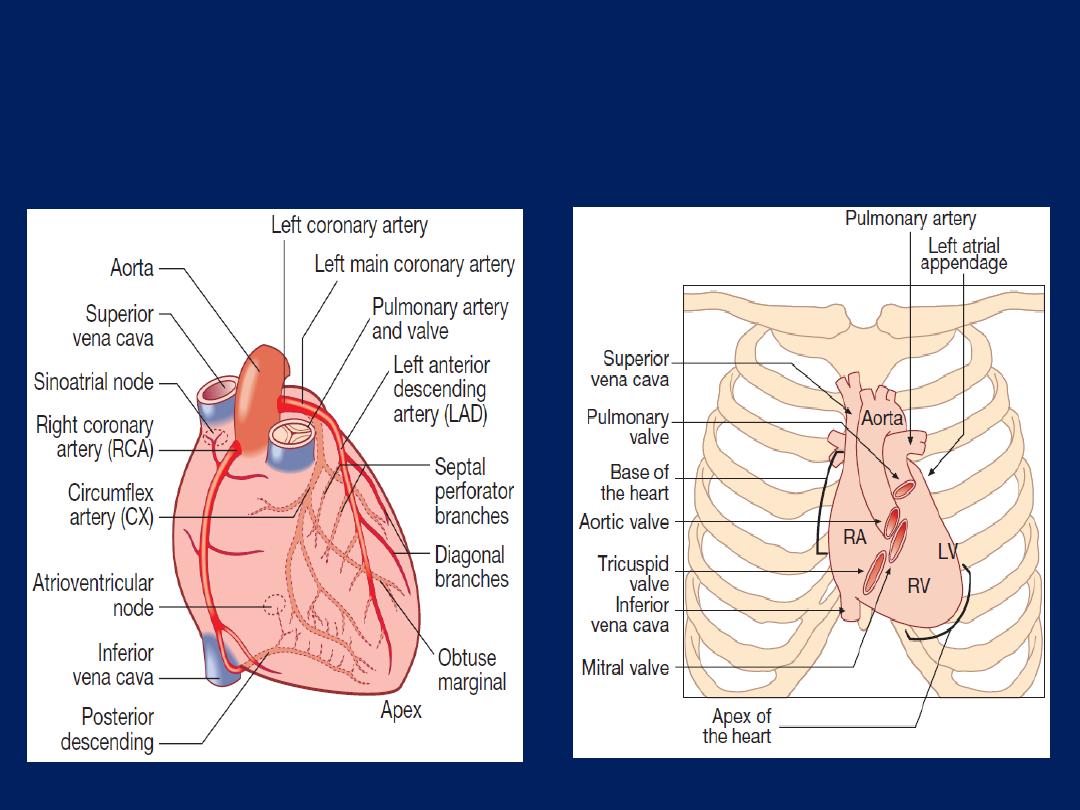

Surface anatomy of

the heart.

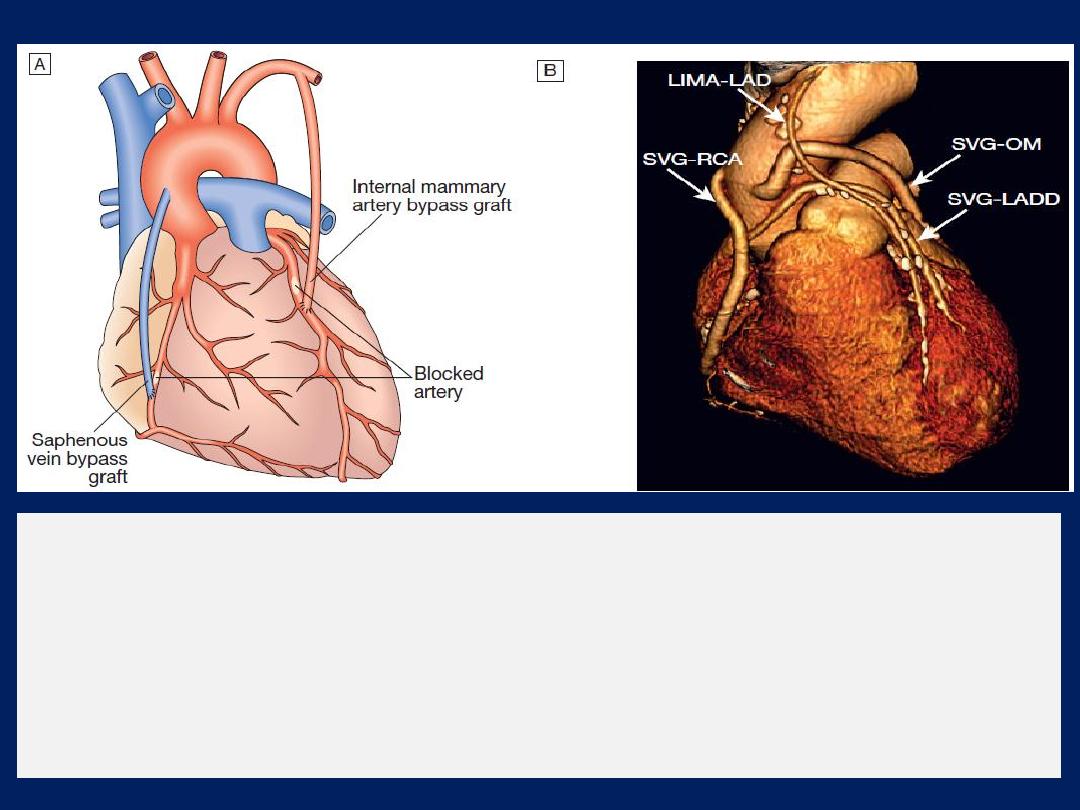

The coronary arteries.

anterior view.

The coronary circulation

The left main and right coronary arteries arise from the

left and right sinuses of the aortic root, distal to the aortic

valve . Within 2.5 cm of its origin, the left main

coronary artery divides into the left anterior descending

artery (LAD), which runs in the anterior interventricular

groove, and the left circumflex artery (CX), which runs

posteriorly in the atrioventricular groove.

The LAD gives branches to supply the anterior part of the

septum , the anterior, lateral and apical walls of the LV.

The CX supply the lateral, posterior and inferior segments

of the LV.

The right coronary artery (RCA) runs in the right

atrioventricular groove, supply the RA, RV and

inferoposterior aspects of the LV.

The posterior descending artery runs in the posterior

interventricular groove and supplies the inferior part of

the interventricular septum. This vessel is a branch of the

RCA in approximately 90% of people (

dominant right

system) and is supplied by the CX in the remainder

(

dominant left system

). The RCA supplies the sinoatrial

(SA) node in about 60% and the AV node in about 90%.

Abrupt occlusions in the RCA, result in infarction of the

inferior part of the LV and often the RV. Occlusion of the

left main coronary artery is usually fatal. The venous

system follows the coronary arteries but drains into the

coronary sinus in the atrioventricular groove, and then to

the RA. The lymphatic system drains into vessels that

travel with the coronary vessels and then into thoracic duct.

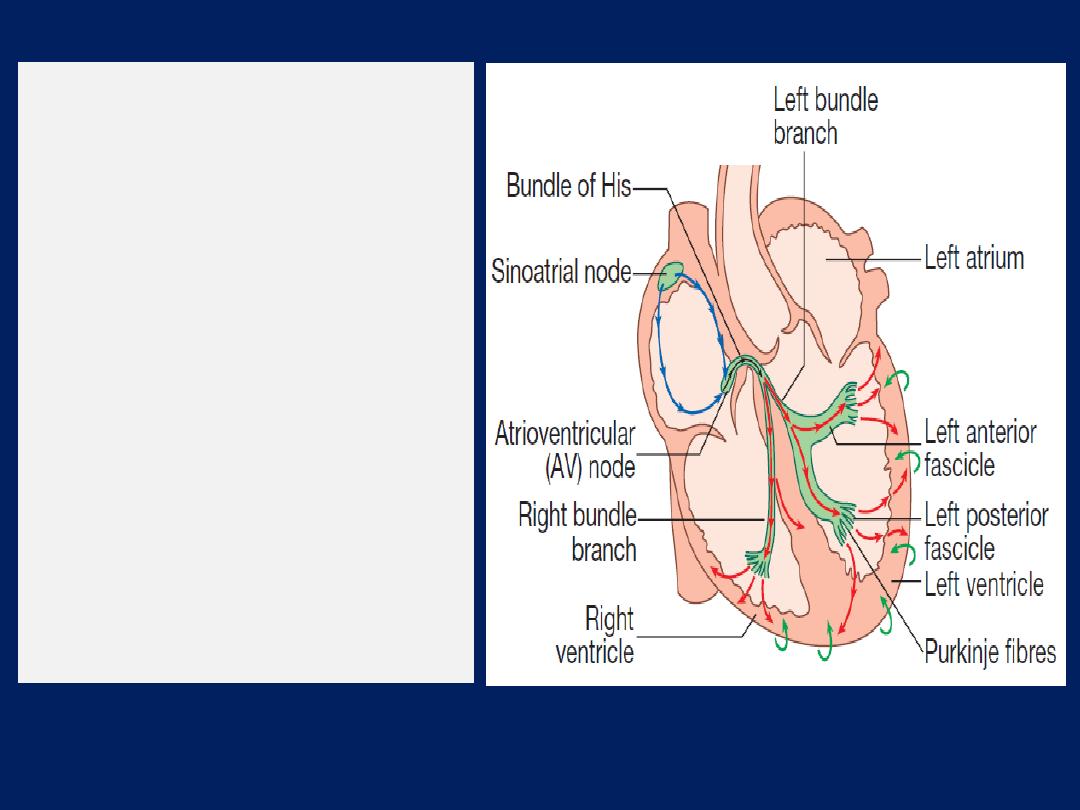

Conducting system of the heart

The SA node is situated at the junction of SVC and RA . It

comprises specialized atrial cells that depolarise at a rate

influenced by the autonomic nervous system and by

circulating catecholamines.During normal (sinus) rhythm,

wave propagates through both atria via atrial myocytes to

the AV node conduct relatively slowly producing a

necessary time delay between atrial and ventricular

contraction. The His–Purkinje system extending from the

AV node into right and left bundle branches passing along

the septum and into the respective ventricles, the anterior

and posterior fascicles of the left bundle, and the smaller

Purkinje fibres that ramify through the myocardium.

His–Purkinje conduct very rapidly and

allow

near-

simultaneous depolarisation of the entire myocardium.

The cardiac conduction

system.

Depolarisation starts

in the sinoatrial node and

spreads through the atria

(blue arrows), and then

through the atrioventricular

node (black arrows).

Depolarisation then spreads

through the bundle of His and

the bundle branches to reach

the ventricular muscle (red

arrows).

Repolarisation

spreads from epicardium

to

endocardium (green arrows).

Nerve supply of the heart

The heart is innervated by

sympathetic

(from the cervical

sympathetic chain , supply muscle fibres in the atria ,

ventricles and the electrical conducting system, β

1

-

adrenoceptors mediate positive inotropic and chronotropic

effects, whereas β

2

-adrenoceptors predominate in vascular

smooth muscle and mediate vasodilatation),

and parasympathetic

fibres . Parasympathetic pre-

ganglionic fibres and sensory fibres reach the heart through

the vagus nerves. Cholinergic nerves supply the AV and SA

nodes via muscarinic (M2) receptors.

Under resting conditions, vagal inhibitory activity

predominates and the heart rate is slow.

Adrenergic stimulation, associated with exercise, emotional

stress, fever and so on, causes the heart rate to increase.

Myocardial contraction

Myocardial cells (myocytes) branches and interdigitates

with adjacent cells.

The basic unit of contraction is the sarcomere . Actin

filaments are attached at right angles to the Z-lines and

interdigitate with thicker parallel myosin filaments.

The cross-links between actin and myosin molecules

contain myofibrillar adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase),

which breaks down adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to

provide the energy for contraction .

The extent to which the sarcomere can shorten determines

stroke volume of the ventricle. The force of cardiac muscle

contraction, or inotropic state, is regulated by the influx

of calcium ions through ‘slow calcium channels’.

Cardiac output

is the product of stroke volume and heart

rate. Stroke volume is the volume of blood ejected in each

cardiac cycle, and is dependent upon end-diastolic volume

and pressure (preload), myocardial contractility and

systolic aortic pressure (afterload).

Starling’s Law of the heart

:

Stretch of cardiac muscle (from increased end-diastolic

volume) causes an increase in the force of contraction,

producing a greater stroke volume

The contractile state of the myocardium is controlled

by neuro-endocrine factors, such as adrenaline and can be

influenced by inotropic drugs and their antagonists.

Blood flow

Blood passes from the heart through the large central

elastic arteries into muscular arteries before encountering

the resistance vessels, and ultimately the capillary bed,

where there is exchange of nutrients, oxygen and waste

products of metabolism.

The central arteries,

such as the

aorta, are predominantly composed of elastic tissue with

little or no vascular smooth muscle cells. When blood is

ejected, the compliant aorta expands to accommodate the

volume of blood before the elastic recoil sustains blood

pressure (BP) and flow following cessation of cardiac

contraction.

This‘Windkessel effect’

(Windkessel when loosely

translated from German to English means 'air chamber‘)

prevents

excessive rises in systolic BP whilst sustaining diastolic BP,

thereby maintaining coronary perfusion.

Windkessel vessels e.g. aorta, common carotid, subclavian,

and pulmonary arteries and their larger branches).

Since the rate of blood entering these elastic arteries

exceeds that leaving them due to the peripheral resistance

there is a net storage of blood during systole which

discharges during diastole. The pulsatile flow of blood

during systole converted into continuous flow due to elastic

recoiling of the vessel during diastole and maintaining

coronary perfusion. These benefits are lost with

progressive arterial stiffening , a feature of ageing and

advanced renal disease as the arteriosclerosis, lead to

fragmentation and loss of elastin and the elastic arteries

become less compliant, The reduction in the Windkessel

effect results in increased pulse pressure and elevated

systolic pressure for a given stroke volume.

Passing down the arterial tree, vascular smooth

muscle cells progressively play a greater role until the

resistance arterioles are encountered. Although all

vessels contribute, the resistance vessels (diameter

50–200 μm) provide the greatest contribution to systemic

vascular resistance, with small changes in radius

having a marked influence on blood flow; resistance

is proportional to the fourth power of the radius

(Poiseuille’s Law).

The tone of these resistance vessels is tightly regulated by

humoral, neuronal and mechanical factors.

Coronary blood vessels receive sympathetic and parasympathetic

innervation.

Stimulation

of α- adrenoceptors causes vasoconstriction;

stimulation

of

β

2

-adrenoceptors causes vasodilatation; the predominant

effect of sympathetic stimulation in coronaries is vasodilatation.

Parasympathetic stimulation (muscarinic) also causes dilatation of

normal coronaries.

As a result

of vascular regulation, an atheromatous narrowing in a

coronary artery does not limit flow, even during exercise, until the

cross-sectional area of the vessel is reduced by at least 70%.

In addition

, systemic and locally released vasoactive substances

influence tone; vasoconstrictors include noradrenaline (norepinephrine),

angiotensin II and endothelin-1, whereas adenosine, bradykinin,

prostaglandins and nitric oxide are vasodilators.

Resistance to blood flow rises with

viscosity

and is mainly influenced

by red cell concentration (haematocrit).

Endothelial function

The endothelium

plays a vital role in

the control of vascular

homeostasis.

It synthesises

and releases many vasoactive

mediators that cause vasodilatation, including nitric oxide,

prostacyclin and vasoconstriction, including endothelin-1

and angiotensin II. A balance exists contributes to the

maintenance and regulation of vascular tone and BP.

Damage to the endothelium may disrupt this balance and

lead to vascular dysfunction, tissue ischaemia and

hypertension.

The endothelium also has a major influence on key

regulatory steps in the

recruitment

of inflammatory cells

and on the

formation and dissolution

of thrombus.

The endothelium also stores and

releases von

Willebrand

factor, which promotes thrombus formation by linking

platelet adhesion to denuded surfaces.

In contrast, once

intravascular thrombus forms, tissue

plasminogen activator is rapidly released from adynamic

storage pool within the endothelium to induce fibrinolysis

and thrombus dissolution.

These processes are critically involved in the development

and progression of atherosclerosis, and endothelial

function and injury are seen as central to the pathogenesis

of many cardiovascular disease states.

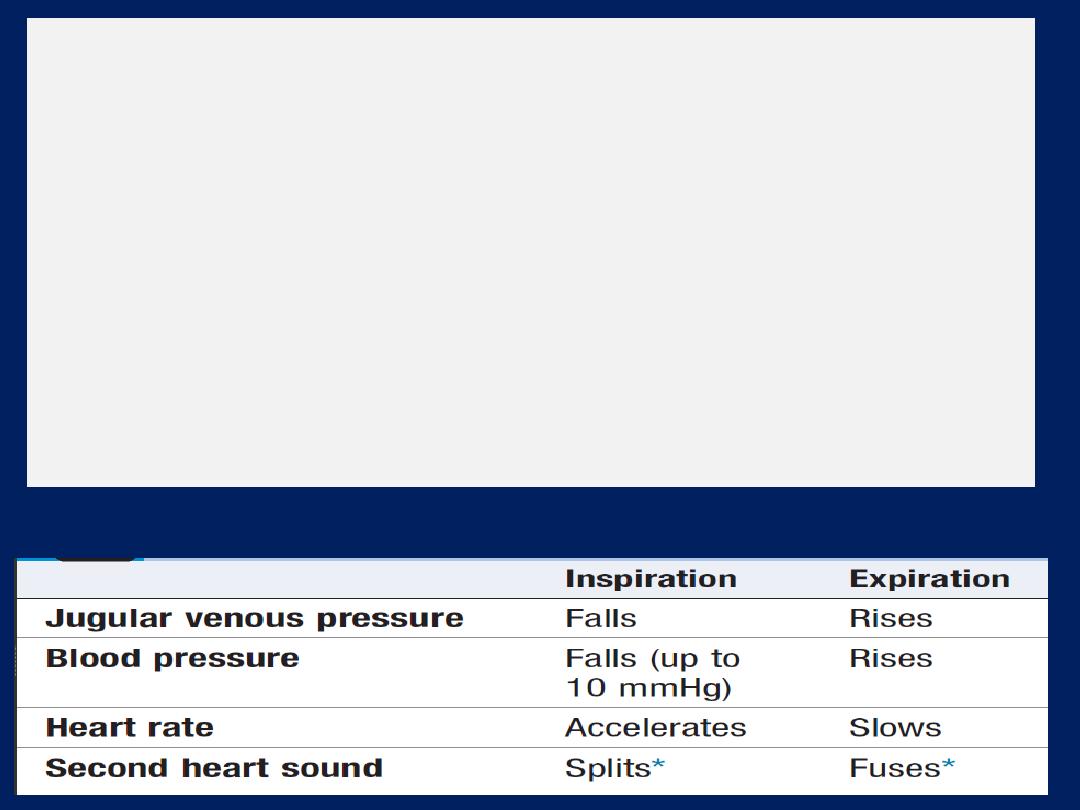

Effects of respiration

There is a fall in intrathoracic pressure during inspiration

that tends to promote venous flow into the chest, producing

an increase in the flow of blood through the right heart.

However, a substantial volume of blood is sequestered in

the chest as the lungs expand; the increase in the

capacitance of the pulmonary vascular bed usually exceeds

any increase in the output of the right heart and therefore

there is a reduction in the flow of blood into the left heart

during inspiration. In contrast, expiration is accompanied by

a fall in venous return to the right heart, a reduction in the

output of the right heart, a rise in the venous return to the

left heart (as blood is squeezed out of the lungs) and an

increase in the output of the left heart .

Pulsus paradoxus

exaggerated fall in BP during inspiration, characteristic

of cardiac tamponade and severe airways obstruction. In

airways obstruction, due to accentuation of the change in

intrathoracic pressure with respiration. In tamponade,

compression of the right heart prevents the normal

increase in flow through the right heart on inspiration,

exaggerates the usual drop in venous return to the left

heart and produces a marked fall in BP

(> 10 mmHg fall).

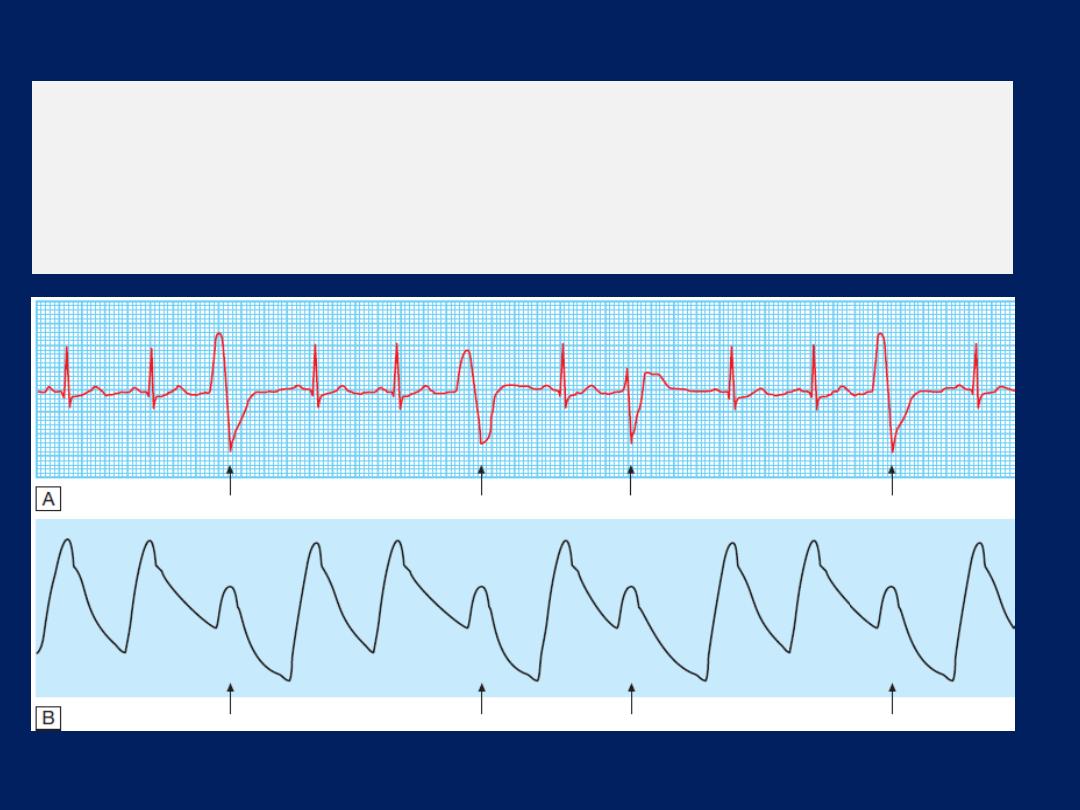

Haemodynamic effects of respiration

INVESTIGATION OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Basic tests, such as electrocardiography, chest X-ray and

echocardiography, can be performed in an outpatient

clinic or at the bedside.

Procedures such as cardiac catheterisation, radionuclide

imaging, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) require specialised facilities.

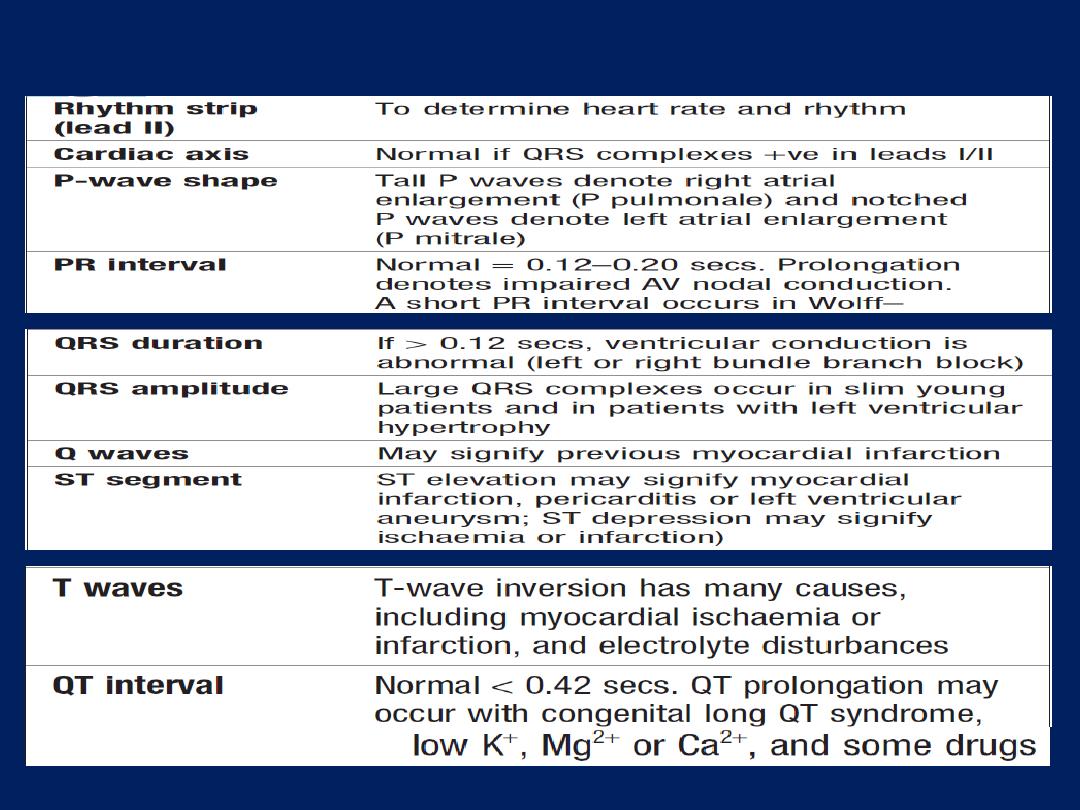

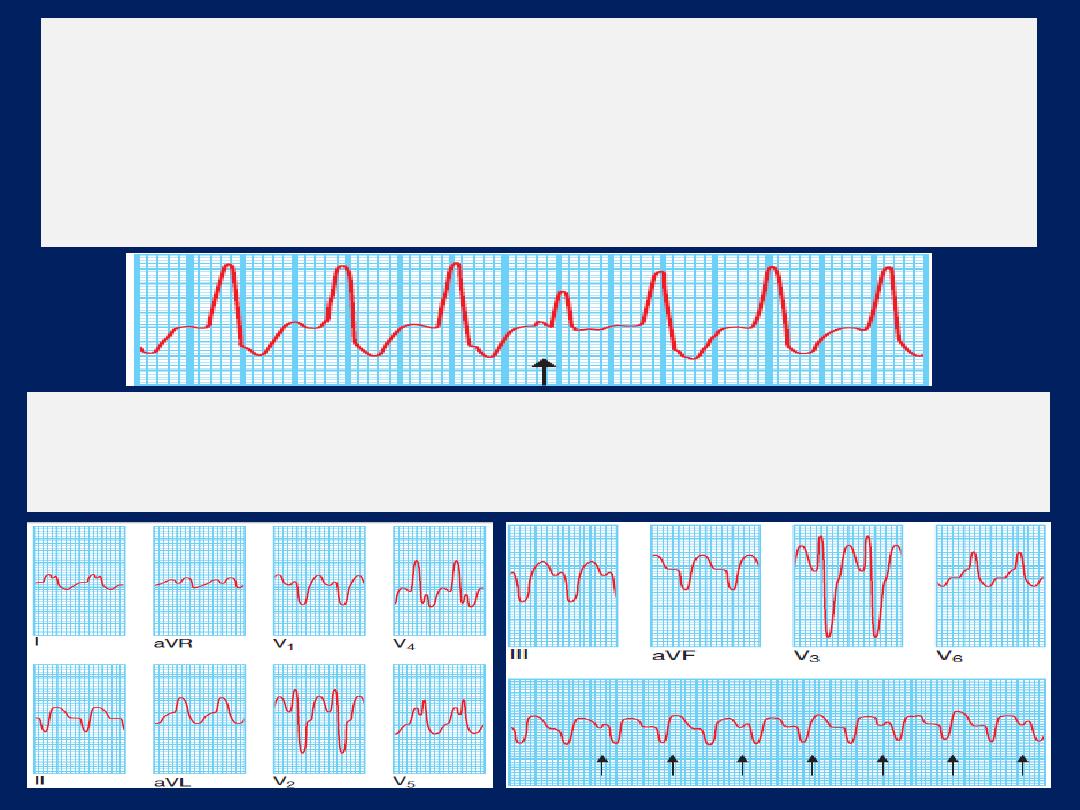

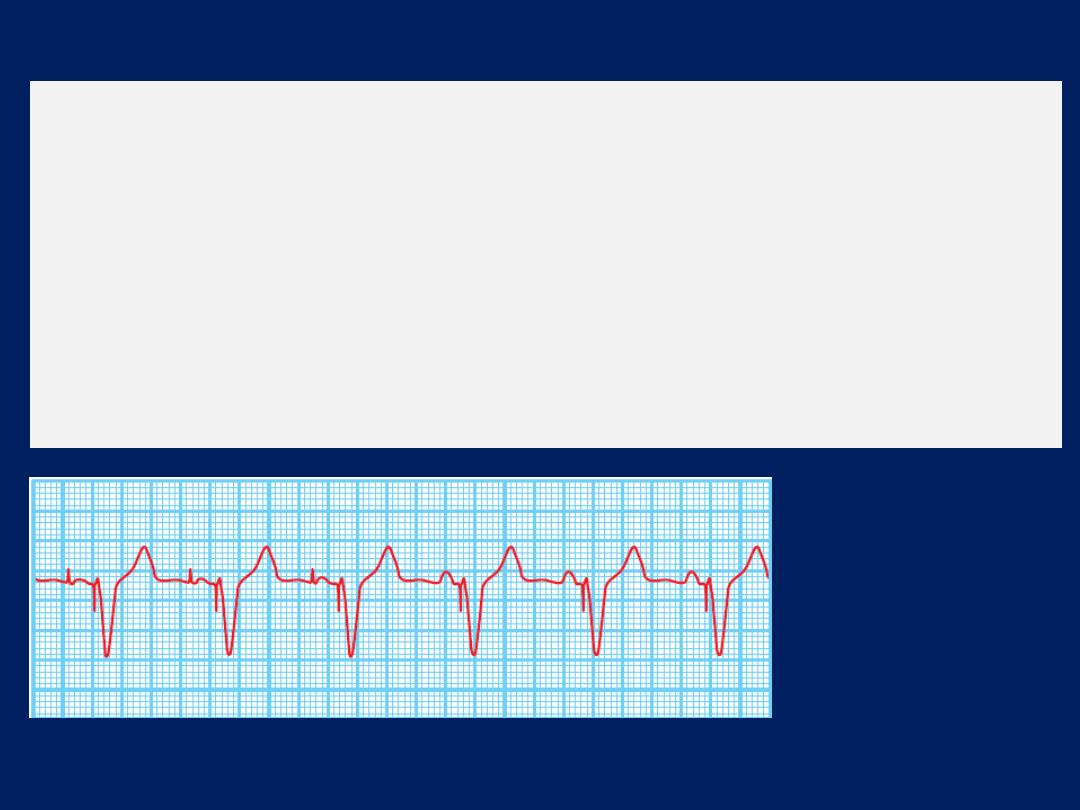

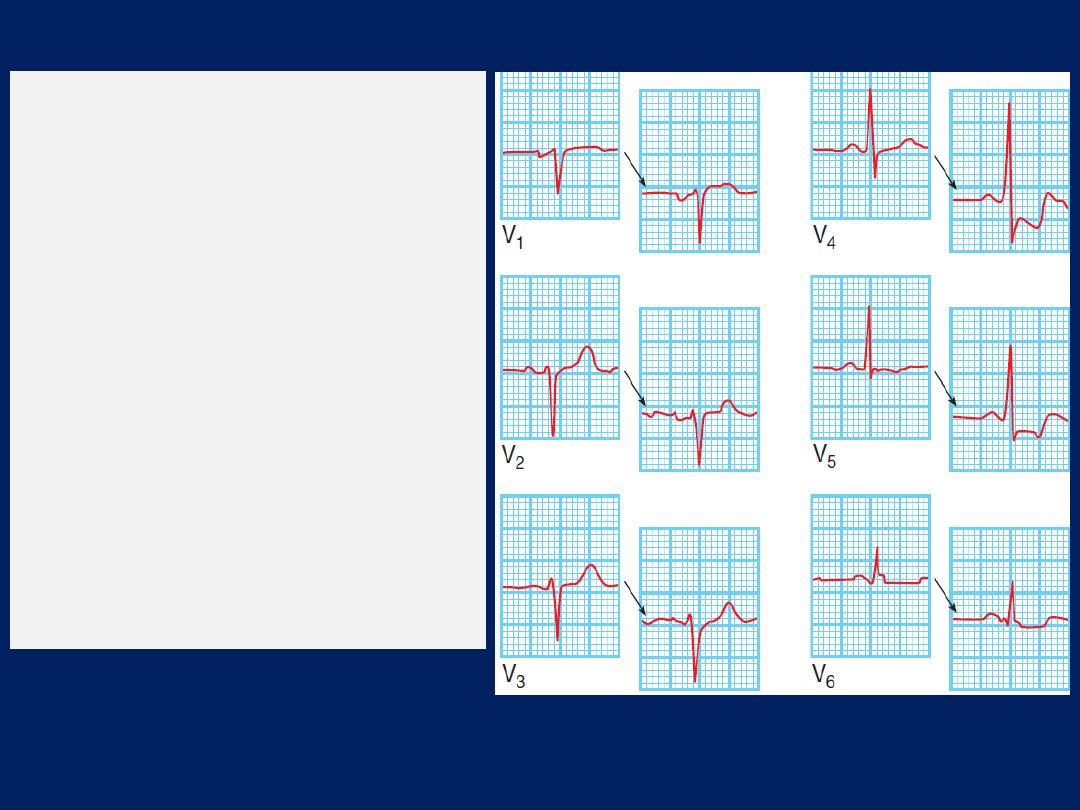

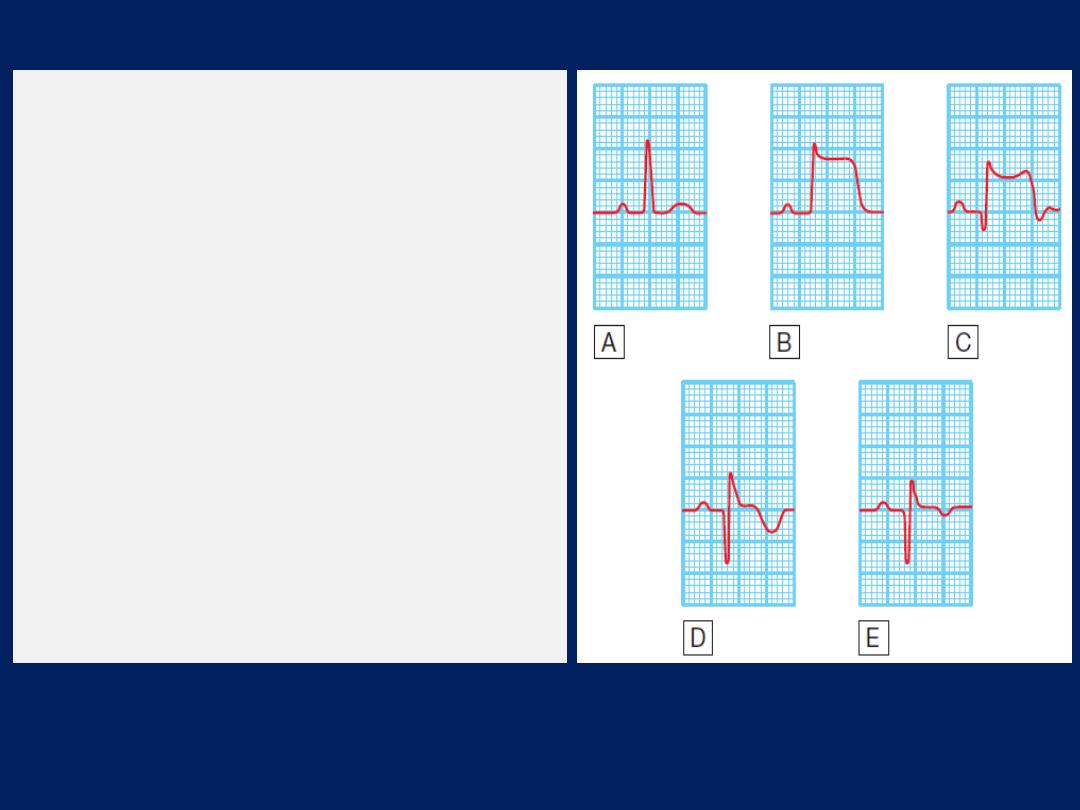

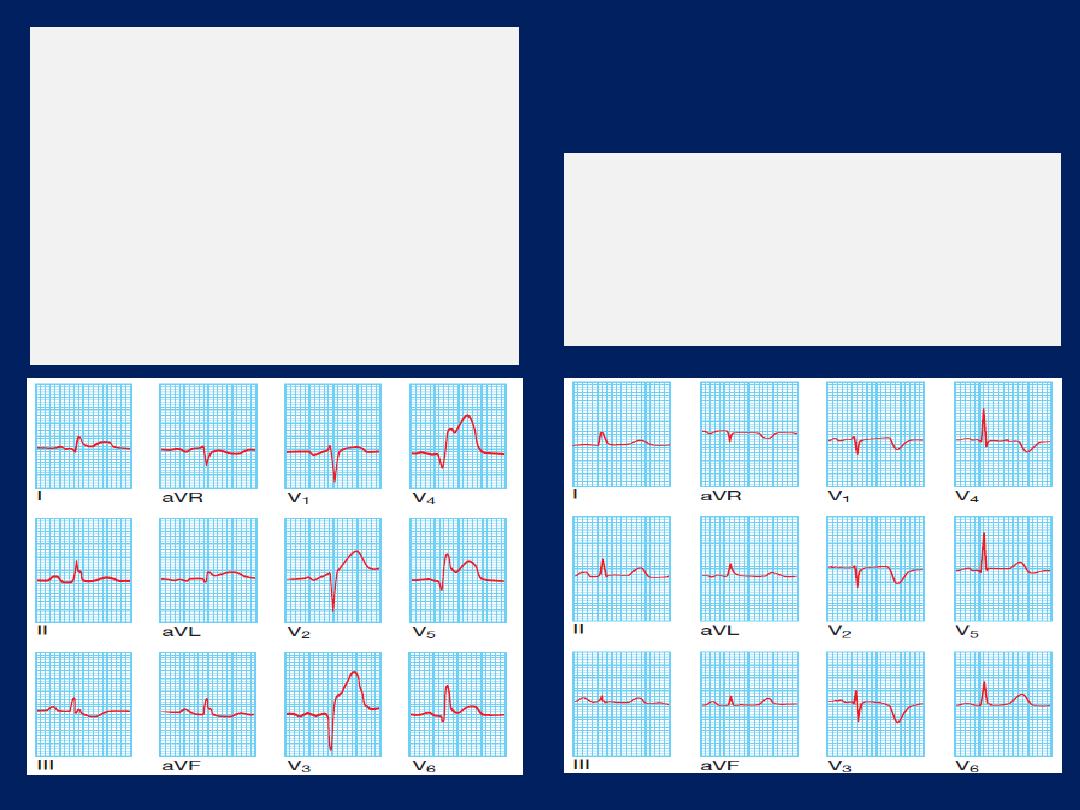

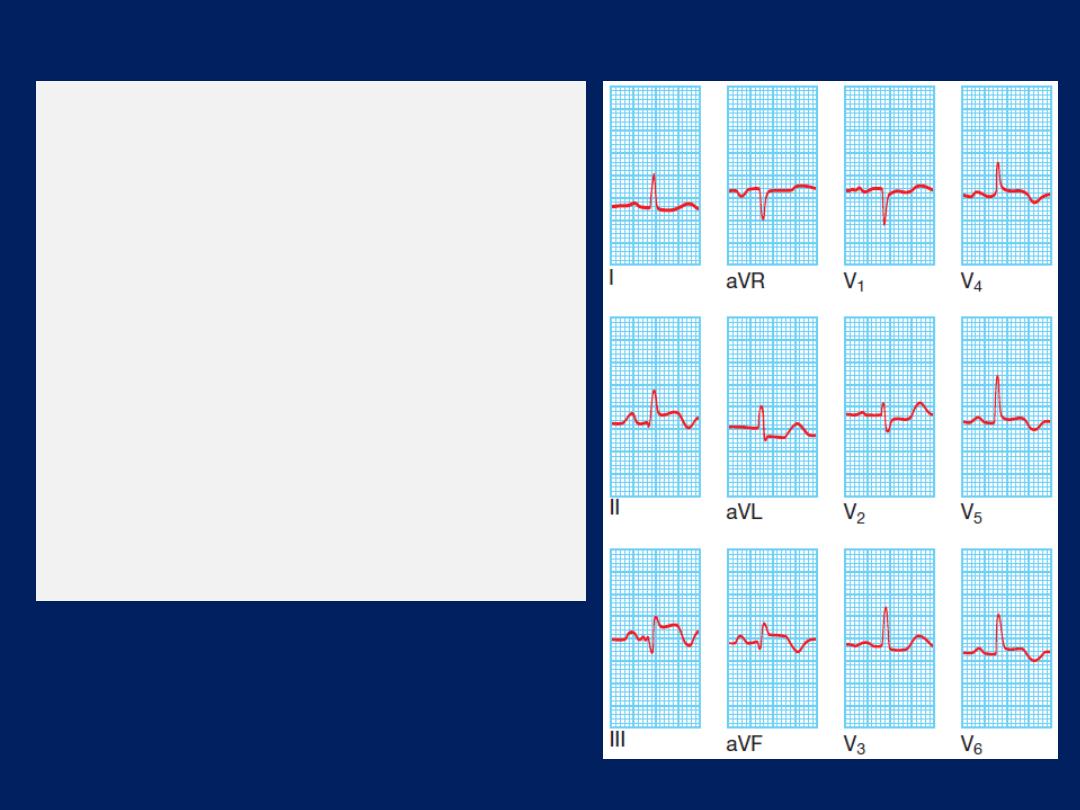

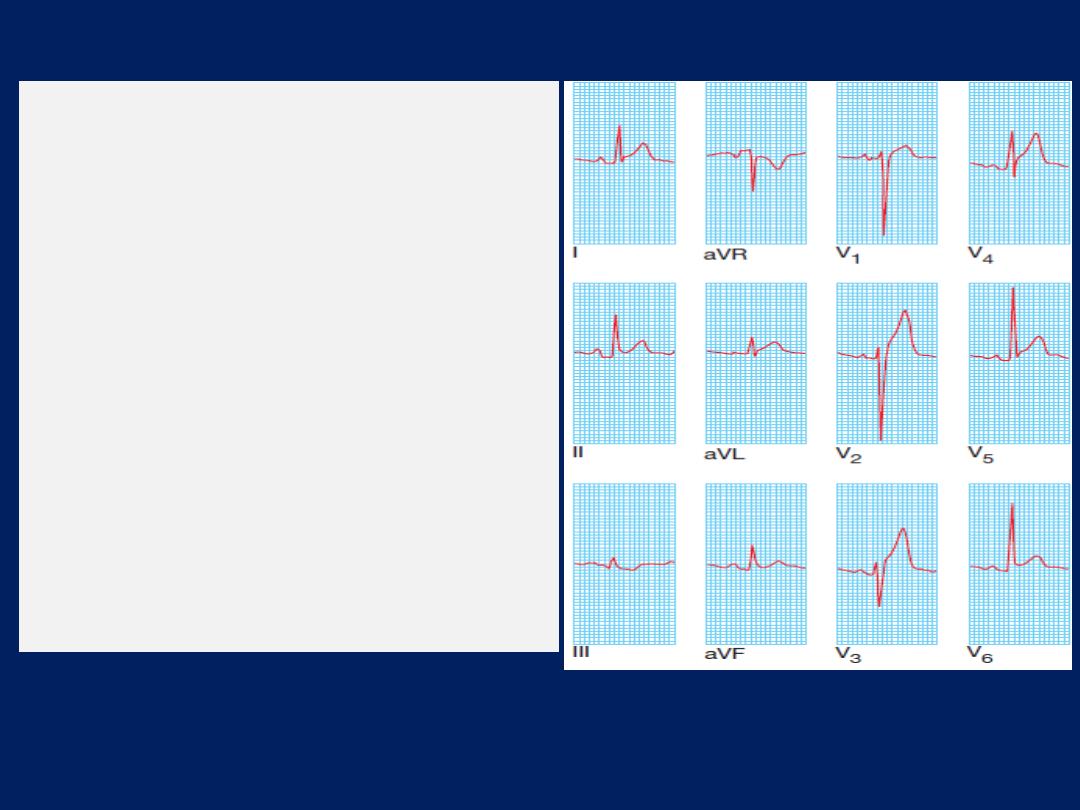

ECG, Leads V1 and V2 lie over the RV, V3 and V4 over

the interventricular septum, V5 and V6 over the LV .

The Depolarisation of the interventricular septum occurs

first and moves from left to right; this generates a small

initial negative deflection in lead V6 (Q wave) and an

initial positive deflection in lead V1 (R wave).

How to read a 12–lead ECG

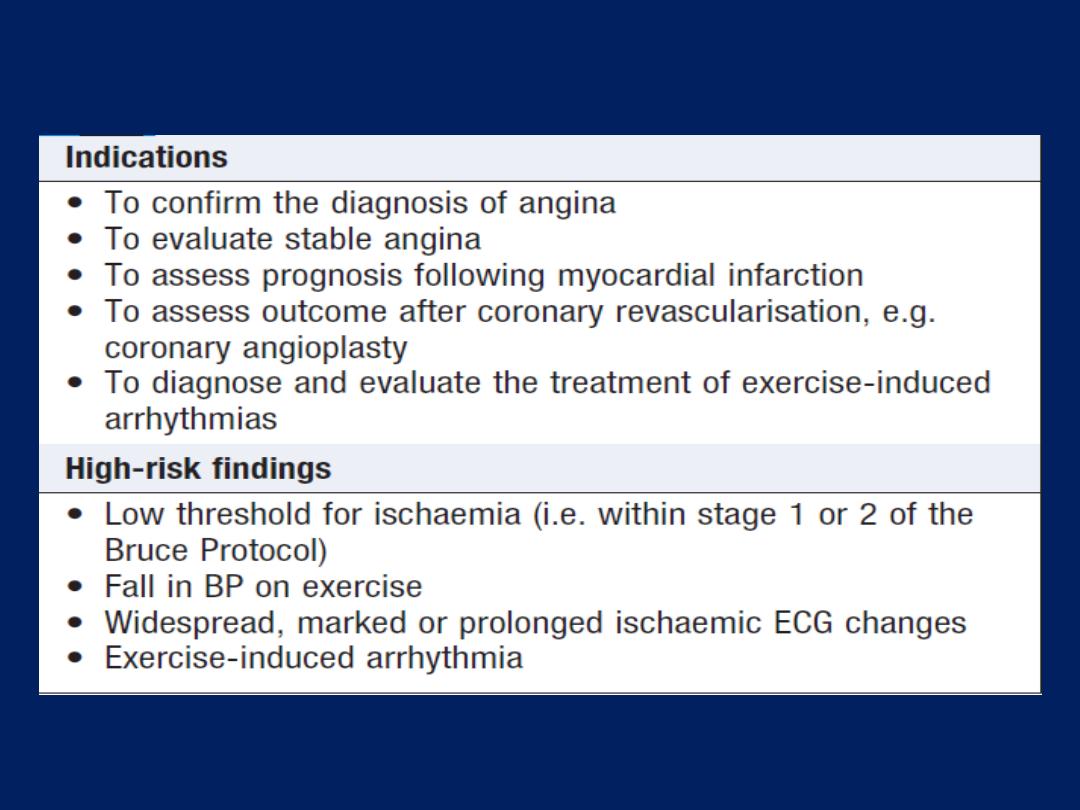

Exercise (stress) ECG

Used to detect myocardial ischaemia during physical stress

and is helpful in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease

(CAD). A 12-lead ECG is recorded during exercise on a

treadmill or bicycle ergometer. The limb electrodes are

placed on the shoulders and hips rather than the wrists

and ankles. The Bruce Protocol is the most commonly used.

BP is recorded and symptoms assessed throughout the test.

A test is ‘

positive

’ if anginal pain occurs, BP falls or fails to

increase, or ST shifts of >1 mm . It is an unreliable

screening tool because, in low-risk (e.g. asymptomatic

young or middle-aged women), an abnormal response is

more likely to represent a false positive. Stress testing is

contraindicated in the presence of ACS , decompensated

heart failure and severe hypertension.

Exercise testing

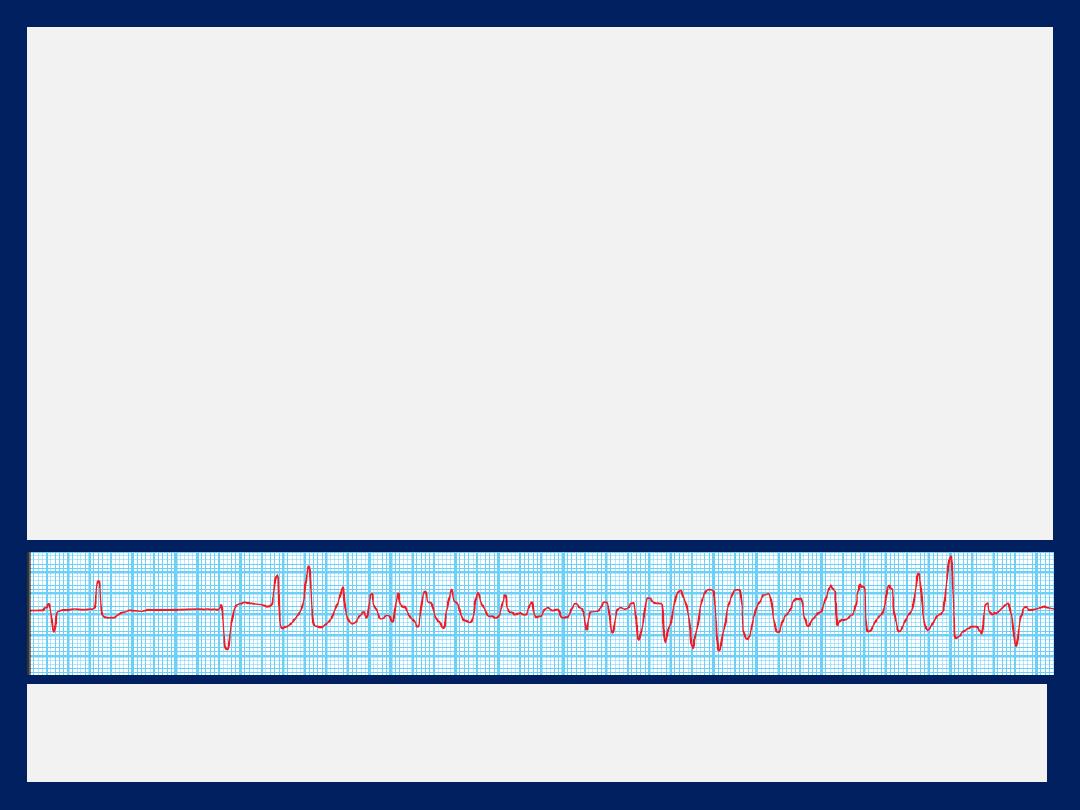

Ambulatory ECG

Continuous (ambulatory) ECG recordings

using a portable

recorder , record between 1 - 7 days. Principally used in the

investigation of suspected arrhythmia, such as those with

intermittent palpitation, dizziness or syncope, can also be

used to assess rate control in atrial fibrillation, sometimes

used to detect transient myocardial ischaemia. With some

devices, the recording can be transmitted to hospital via

telephone.

Implantable ‘loop recorders’

resemble leadless pacemaker ,

implanted subcutaneously, have a lifespan of 1–3 years and

are used to investigate patients with infrequent but

potentially serious symptoms, such as syncope.

Cardiac biomarkers

Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP)

This is

a 32-amino acid peptide and is

secreted by the LV along

with an inactive

76-amino acid N-terminal fragment

(NT- proBNP).

The latter is diagnostically more useful, as it has a longer

half-life, elevated in LV systolic dysfunction,

aid

the

diagnosis , prognosis and response to therapy of failure.

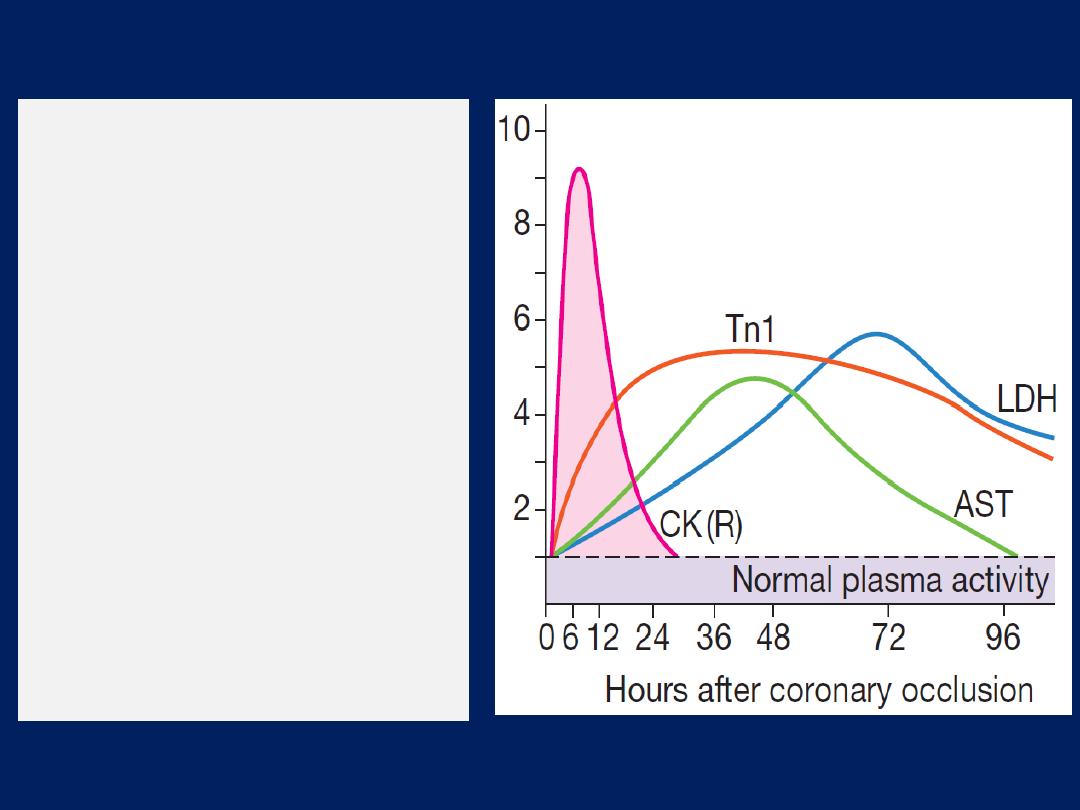

Troponin I and troponin T

are cardiac muscle proteins

released during myocyte damage, and represent the

cornerstone of the diagnosis of acute MI. However, modern

assays are extremely sensitive and can detect very low

levels of myocardial damage, such as : pulmonary embolus,

septic shock and pulmonary oedema. The diagnosis of MI

therefore relies on the clinical presentation.

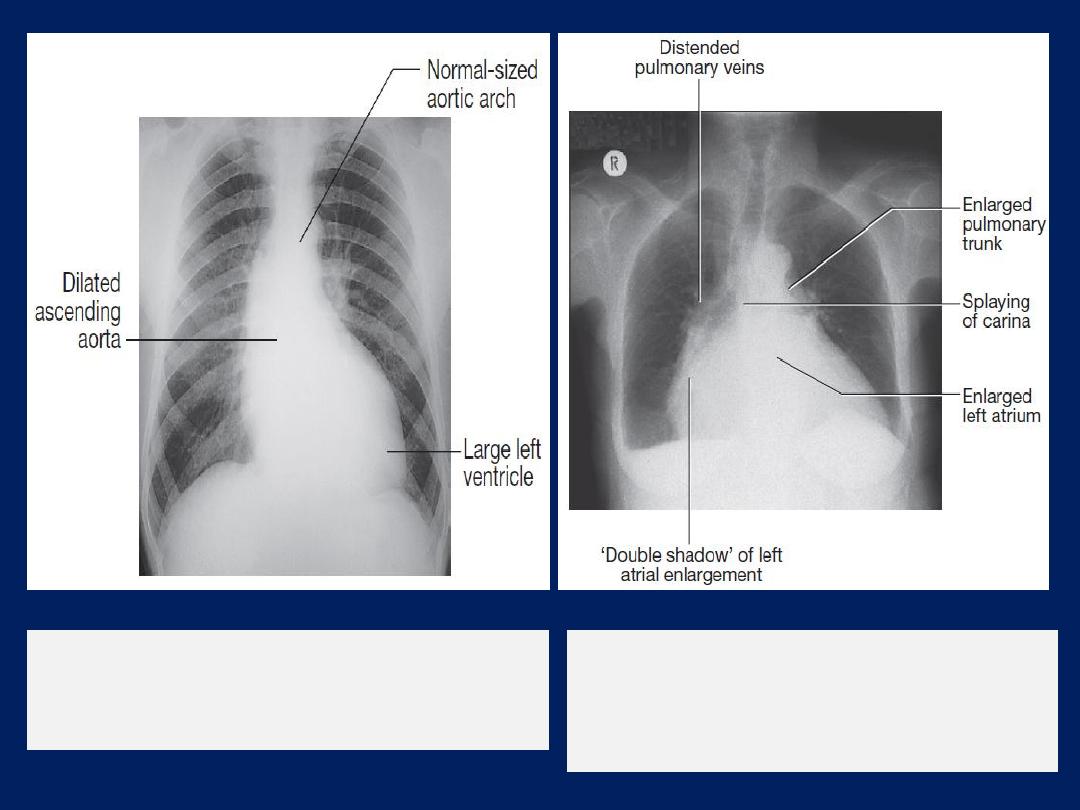

Chest X-ray

‘ Cardiomegaly’

is the term used to describe an enlarged

cardiac silhouette where the ‘cardiothoracic ratio’ is >0.5.

(comparing the maximum width of the cardiac outline with the maximum internal

transverse diameter of the thoracic cavity).

It can be caused by chamber dilatation, especially left

ventricular dilatation, or by a pericardial effusion.

Artefactual

cardiomegaly may be due to a mediastinal

mass or pectus excavatum and cannot be reliably

assessed from an AP film. Cardiomegaly is not a sensitive

indicator of left ventricular systolic dysfunction since the

cardiothoracic ratio is normal in many affected patients

(false-negative) and also lacks specificity with many

patients with apparent cardiomegaly having normal

echocardiograms (false-positive).

Left atrial dilatation

results in prominence of the left atrial

appendage, creating the appearance of a straight left

heart border, a double cardiac shadow to the right of the

sternum, and widening of the angle of the carina as the

left main bronchus is pushed upwards .

• Right atrial enlargement

projects from the right heart

border towards the right lower lung field.

• Left ventricular dilatation

causes prominence of the left

heart border and enlargement of the cardiac silhouette.

• Left ventricular hypertrophy

produces rounding of the

left heart border.

• Right ventricular dilatation

increases heart size, displaces

the apex upwards and straightens the left heart border.

Chest X-ray

of a patient with mitral

stenosis and regurgitation indicating

enlargement of the LA and prominence of

the pulmonary artery trunk.

Chest X-ray

of a patient with aortic

regurgitation, left ventricular enlargement

and dilatation of the ascending aorta.

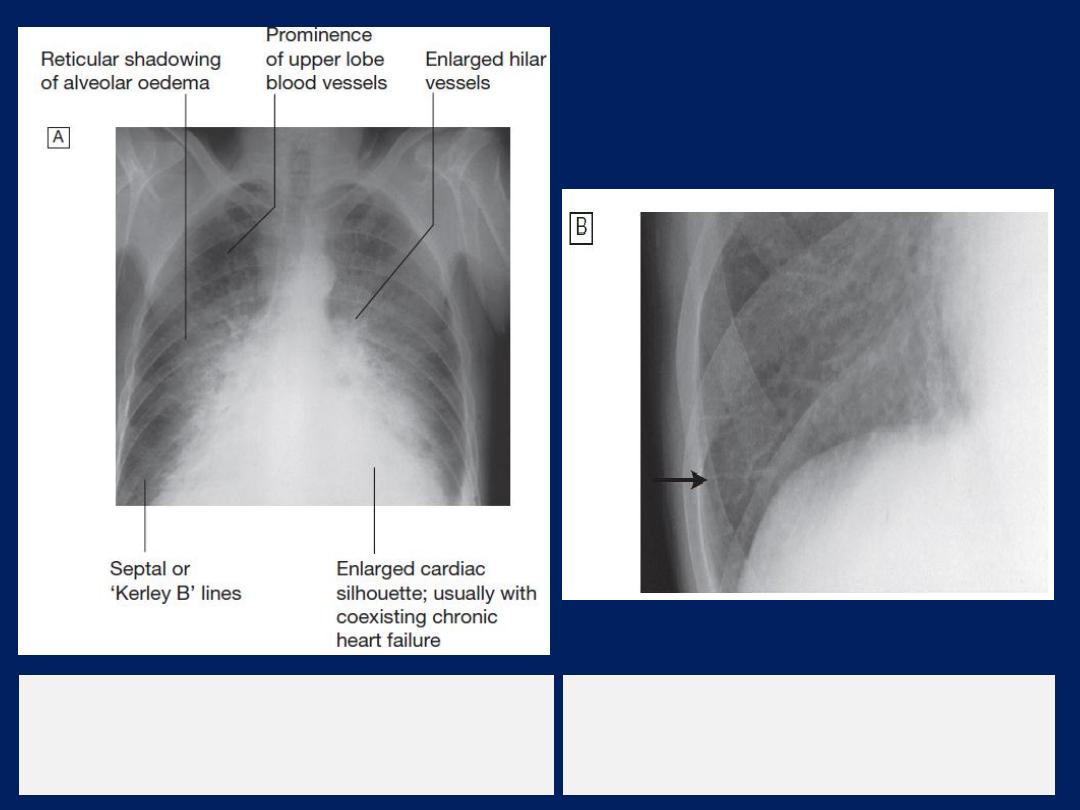

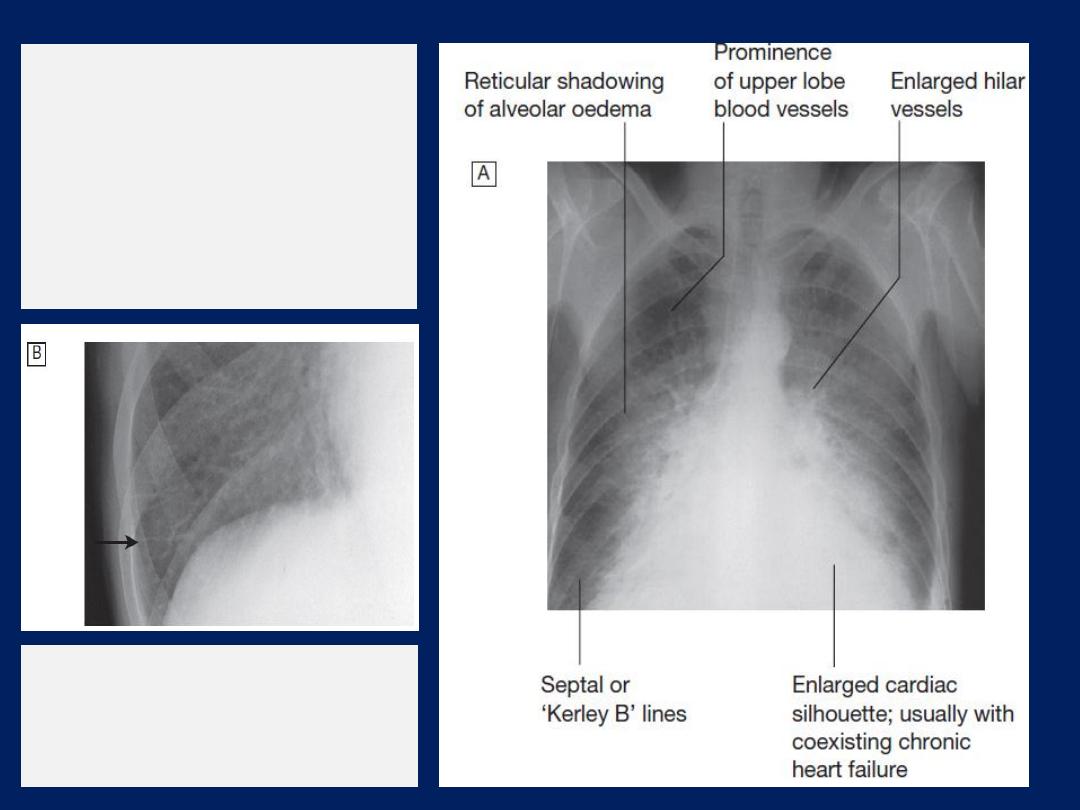

Radiological features of heart failure.

A

Chest X-ray of a patient with pulmonary

oedema.

Radiological features of heart failure.

B

Enlargement of lung base showing

septal or ‘Kerley B’ lines (arrow).

Echocardiography (echo)

This permits the rapid assessment of cardiac structure and

function ,wall thickness and ejection fraction.

Doppler echocardiography

This depends on the Doppler principle that sound waves

reflected from moving objects, such as RBC. The speed and

direction of blood, can be detected in the heart chambers

and great vessels. Can be used to detect valvular

regurgitation, where the direction of blood flow is

reversed, and to detect high pressure gradients associated

with stenosed valves. For example, the normal

resting

systolic flow velocity

across the

aortic

valve is 1 m/sec; in

the presence of aortic stenosis, this is increased as blood

accelerates through the narrow orifice.

In severe

stenosis,

the peak aortic velocity may be increased to 5 m/sec .

An estimate of the

pressure gradient

across a valve or

lesion is given by the modified Bernoulli equation:

Advanced techniques

include three-dimensional echo,

intravascular US (defines vessel wall abnormalities and

guides coronary intervention), intracardiac US (provides

high-resolution images) and tissue Doppler imaging

(quantifies myocardial contractility and diastolic function).

Bernoulli equation

Common indications for echocardiography

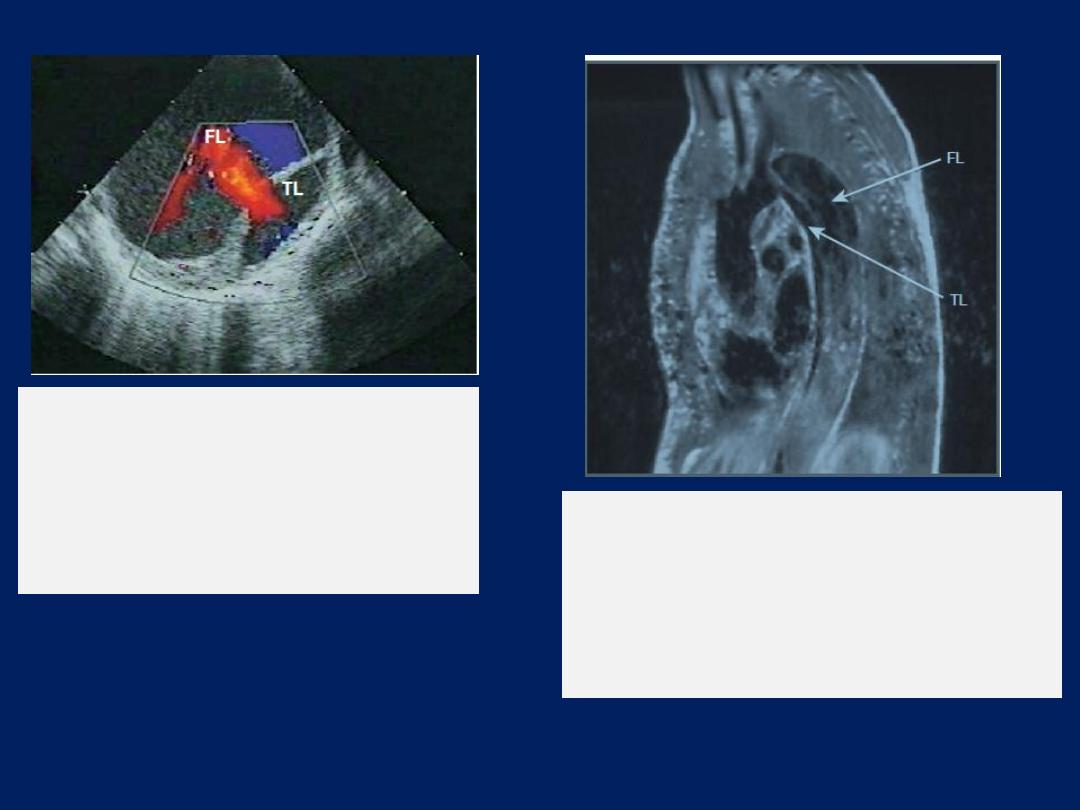

Transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE)

overweight or has obstructive airways disease, structures

that are difficult to visualise in transthoracic views, such as

the left atrial appendage, pulmonary veins, thoracic

aorta and interatrial septum, TOE uses an endoscope-like

ultrasound probe which is passed into the oesophagus

under light sedation and positioned behind the LA. This

produces high-resolution images, which makes the technique

particularly valuable for investigating patients with

prosthetic (especially mitral) valve dysfunction, atrial

septal defect, aortic dissection, infective endocarditis

(vegetations that are too small to be detected by

transthoracic echo) and systemic embolism (intracardiac

thrombus or masses).

Stress echocardiography

Is used to investigate patients with CAD who are

unsuitable for exercise stress testing, such as those with

mobility problems or pre-existing bundle branch block.

A two-dimensional echo is performed before and after

infusion of a moderate to high dose of an inotrope,

such as dobutamine.

Myocardial segments with poor perfusion become ischaemic

and contract poorly under stress, showing as a wall motion

abnormality on the scan. Low-dose dobutamine can induce

contraction in ‘hibernating’ myocardium; such patients may

benefit from bypass surgery or PCI .

Computed tomographic imaging

Imaging chambers, great vessels, pericardium, and

mediastinal structures and masses.

Contrast scans

are

very useful for imaging aortic dissection , pulmonary

arteries and branches in suspected pulmonary embolism .

Some centres use it for quantification of coronary artery

calcification, which may serve as an index of CV risk.

However, modern

multidetector

scanning allows non-

invasive coronary angio with a resolution approaching that

of conventional angio and at a lower radiation.

CT coronary angiography

is particularly useful in the

initial assessment of chest pain and a low or intermediate

likelihood of disease, since its negative predictive value is

very high. Modern volume scanners are also able to assess

myocardial perfusion, often at the same sitting.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI requires no ionizing radiation ,used to image the heart,

lungs and mediastinal structures. It provides better

differentiation of

soft tissue

structures than CT but is poor

at demonstrating calcification. It needs to be ‘gated’ to the

ECG, allowing the scanner to produce moving images of the

throughout the cardiac cycle. Very useful for imaging the

aorta, including suspected

dissection

. It is also useful for

detecting

infiltrative

conditions affecting the heart.

Quantification of blood flow across

regurgitant or stenotic

valves. It is also possible to analyse regional wall motion in

patients with suspected CAD or cardiomyopathy.

The RV

is difficult to assess using echo because of its

retrosternal position but is readily visualised with MRI.

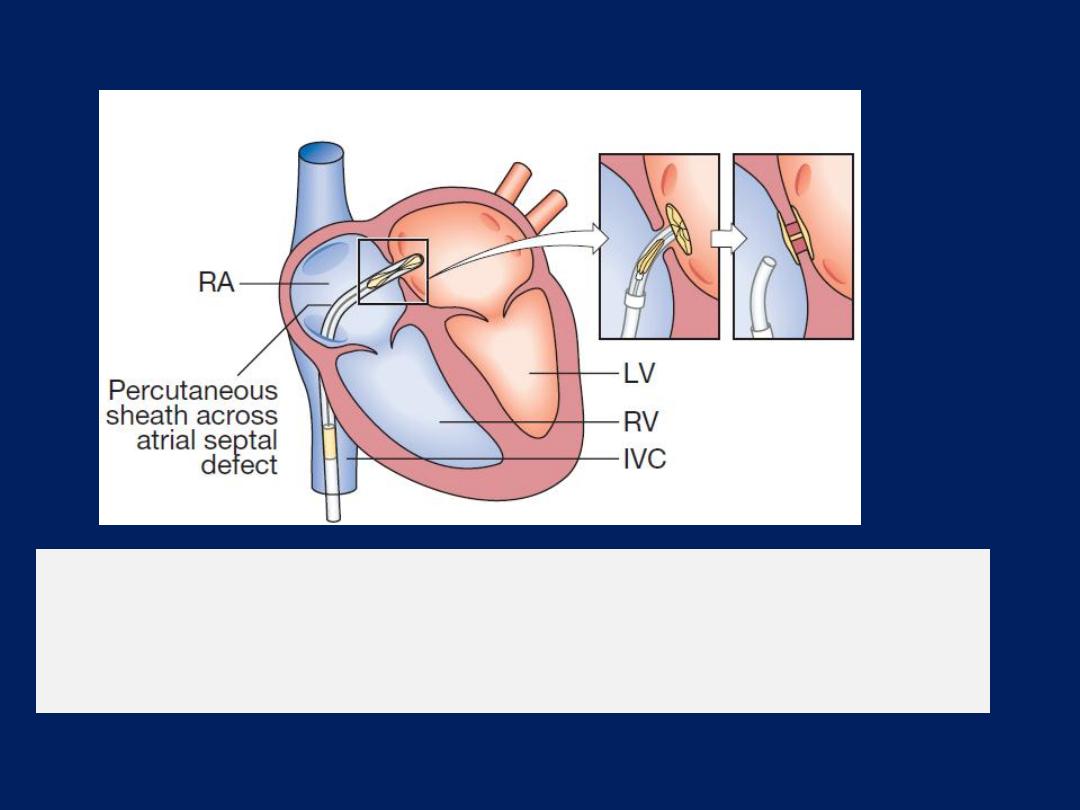

Cardiac catheterisation

This involves passage of catheter via a vein or artery into the heart

under X-ray guidance, which allows the measurement of

pressure

and

oxygen

saturation in the cardiac chambers and great vessels, and the

performance of

angiograms

by injecting contrast media into a

chamber or blood vessel.

Left heart catheterisation

is a day case procedure and is

relatively safe, with serious complications occurring in < 1 in 1000

cases. Usually via the radial artery, to allow catheterisation of the

aorta (

aortography

defines the size of the aortic root and thoracic

aorta, and can help quantify aortic regurgitation).

Left

ventriculography

to determine the size and function of the LV and to

demonstrate mitral regurgitation.

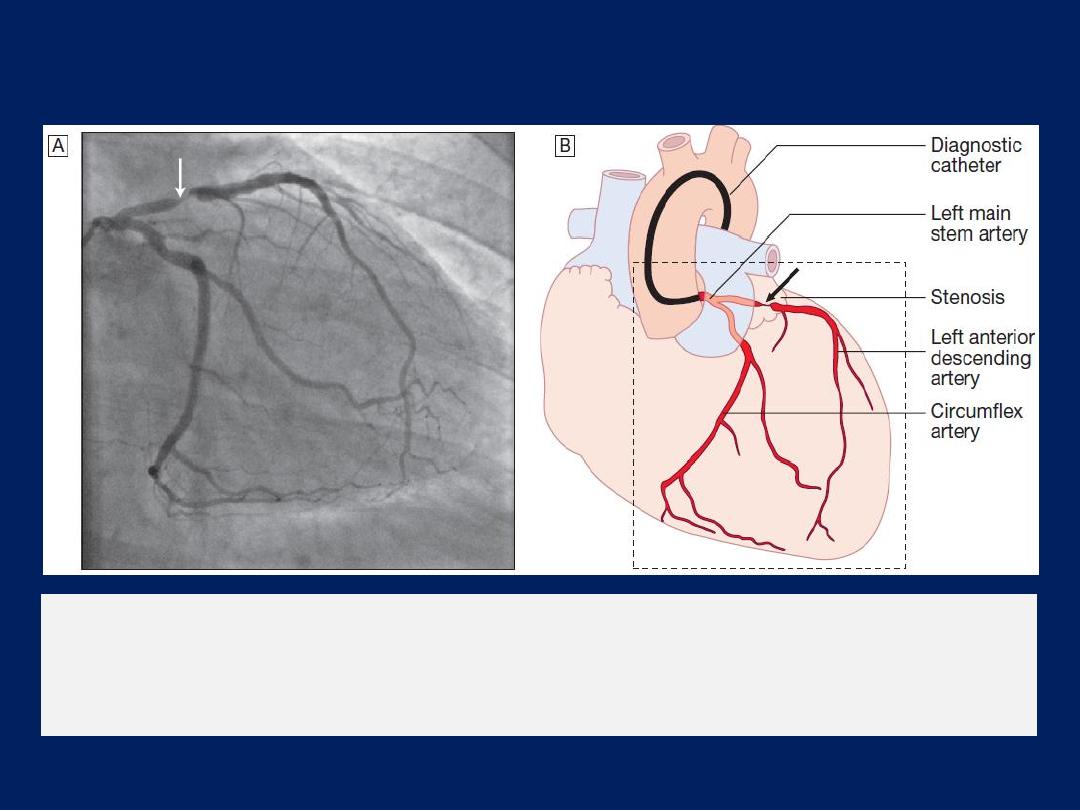

Coronary angiography

in which the left and right coronary arteries

are selectively cannulated and imaged, providing information about

the extent and severity of coronary stenoses, thrombus and

calcification and permits planning of PCI and CABG .

Right heart catheterisation

is used to assess right

heart and pulmonary artery pressures, and to detect

intracardiac shunts by measuring oxygen saturations. For

example, a step up in oxygen saturation from 65% in the

RA to 80% in the pulmonary artery is indicative of a large

left-to-right

shunt

that might be due to a VSD .

Cardiac output

can also be measured using thermodilution

techniques.

Left atrial pressure

can be measured directly

by puncturing the interatrial septum from the RA. For most

purposes, however, a satisfactory approximation can be

obtained by ‘wedging’ Swan– Ganz balloon catheter , to

monitor ‘wedge’ in a branch of the pulmonary artery as a

guide to left filling pressure in critically ill patients .

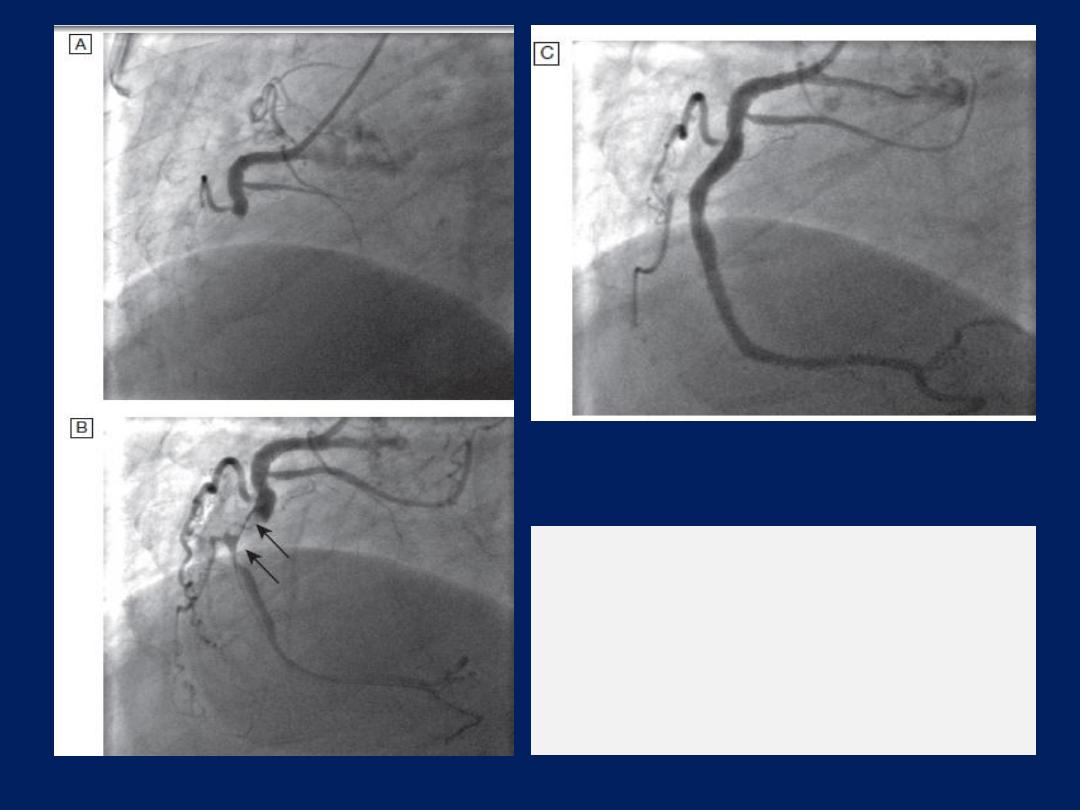

The left anterior descending and circumflex

coronary arteries with

a stenosis in the left anterior descending vessel.

A

Coronary artery

angiogram.

B

Schematic of the vessels and branches

Electrophysiology study (EPS)

Patients with known or suspected arrhythmia investigated

by percutaneous placement of electrode catheters into the

heart via the femoral and neck veins.

EPS performed to evaluate patients for catheter ablation,

normally done during the same procedure.

Radionuclide imaging

Non-invasive gamma-emitting radionuclides study cardiac

function .

Two techniques are available,

although their use is

declining due to the availability of equivalent or superior

imaging that have lower or no exposure to radiation.

Blood pool imaging

The isotope is injected IV. A gamma camera detects the

amount of radiation-emitting blood in the heart at different

phases of the cardiac cycle, permitting the calculation of

ventricular

ejection fractions

and assessment

size and

shape

of the cardiac chambers.

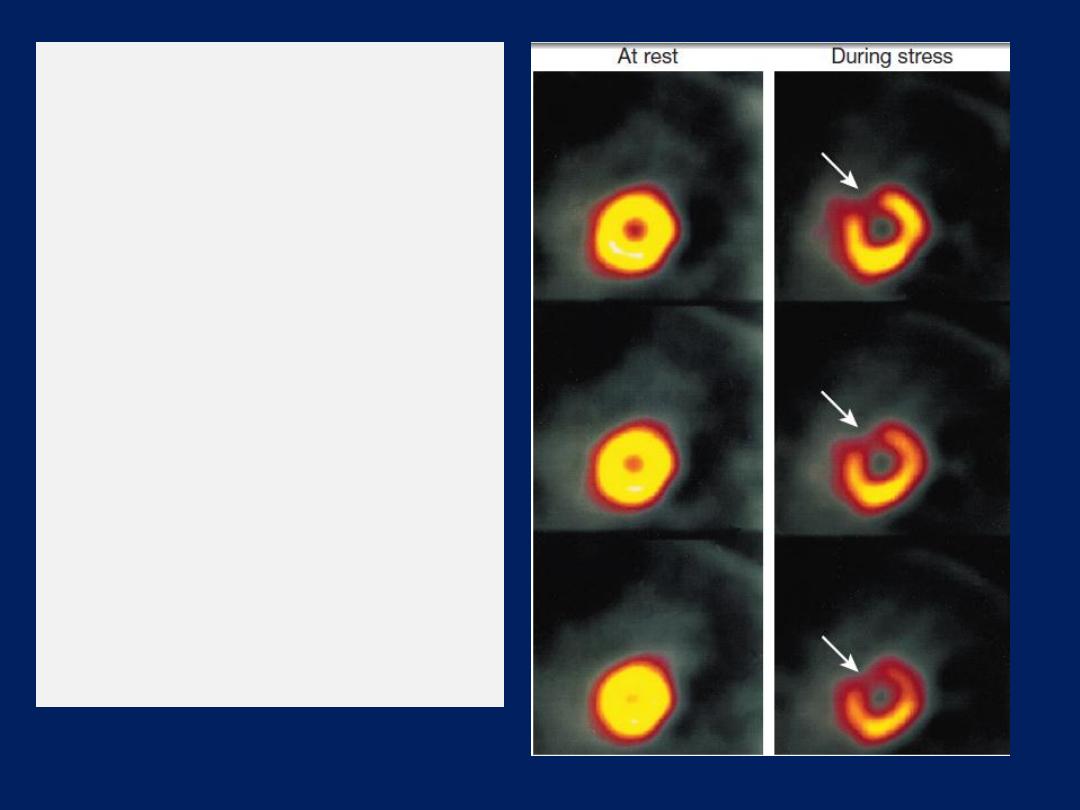

Myocardial perfusion imaging

A dministration of an IV radioactive isotope, such as

99

technetium

tetrofosmin to obtain scintiscans of the

myocardium at rest and during stress . More sophisticated

quantitative information is obtained with positron emission

tomography

(PET),

which can also be used to assess

myocardial metabolism, but this available in a few centres

PRESENTING PROBLEMS IN CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

A close relationship

between symptoms and exercise is the

hallmark of heart disease.

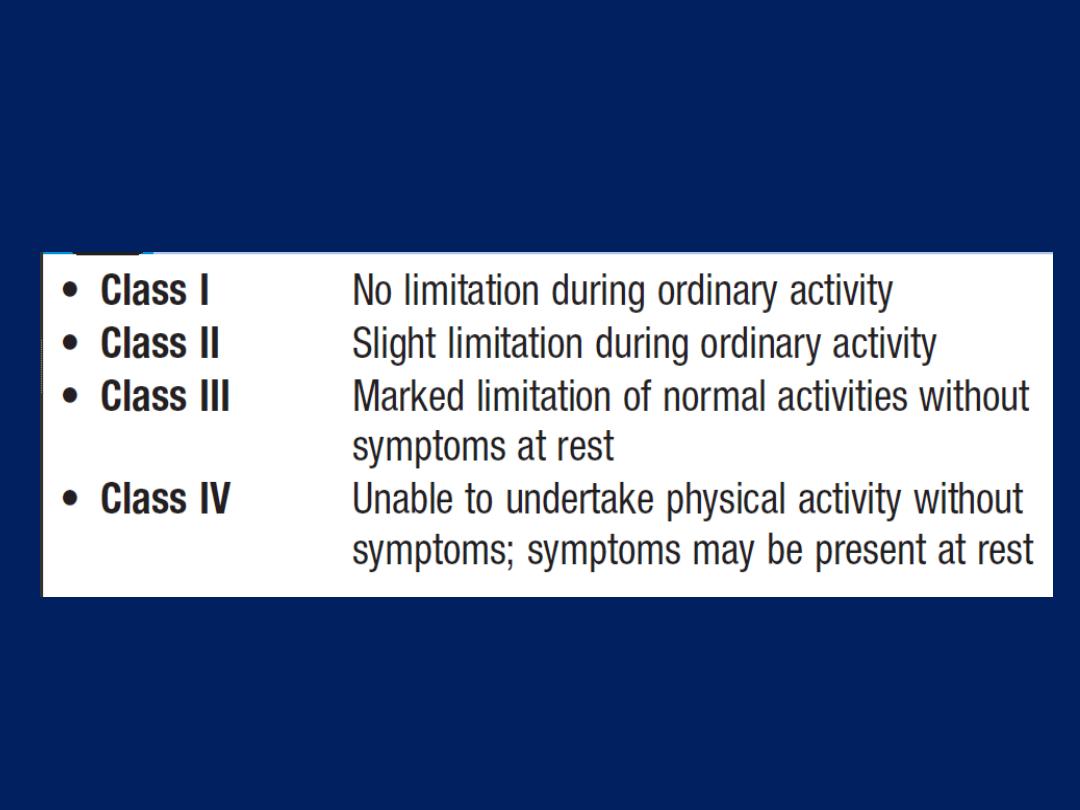

The New York Heart Association

(NYHA)

functional classification is used

to grade disability .

Pain that occurs after rather than during exertion is usually

musculoskeletal or psychological in origin.

The pain of MI typically takes several minutes or longer to

develop; similarly, angina builds up gradually .

The pain of :

aortic dissection, pneumothorax , or massive pulmonary

embolism is usually very sudden or instantaneous in onset.

New York Heart Association (NYHA)

functional classification

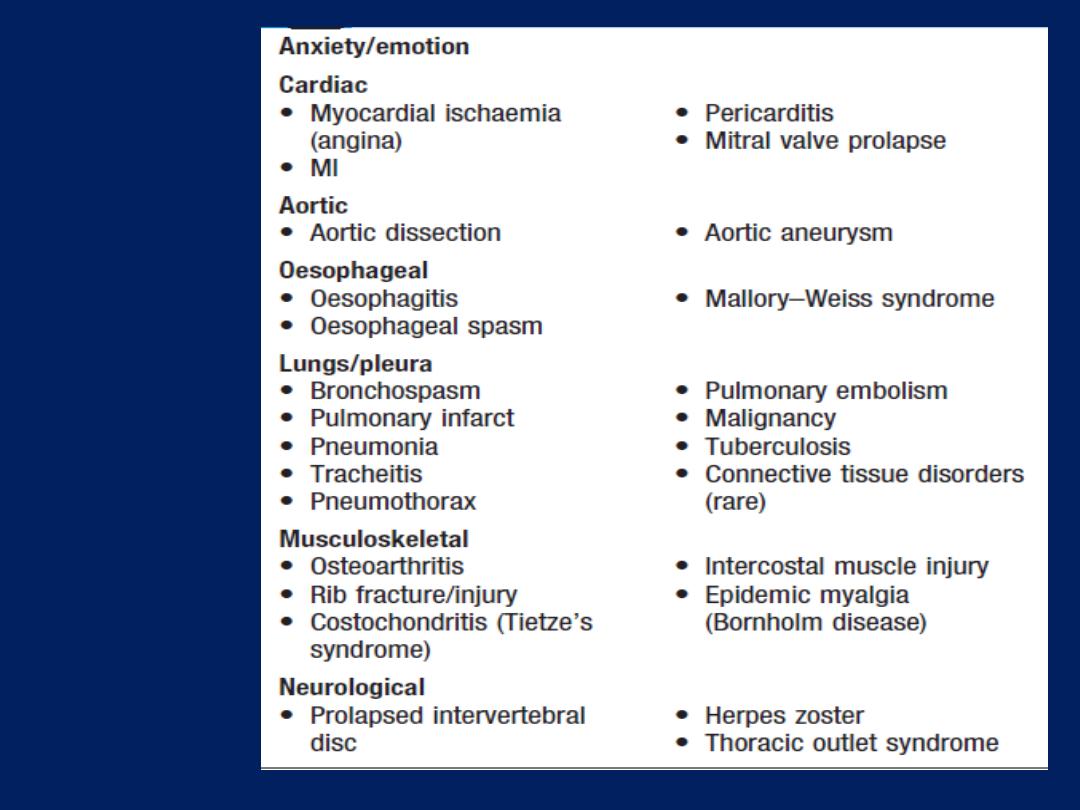

Common

causes of

chest pain

Chest pain

Characteristics of cardiac pain

• Site.

Cardiac pain is typically located in the centre

of the chest because of the derivation of the nerve

supply to the heart and mediastinum.

• Radiation

.

Ischaemic cardiac pain may radiate to the

neck, jaw, and upper or even lower arms. Occasionally,

experienced only at the sites of radiation or in the back.

Pain situated over the left anterior chest and radiating

laterally is unlikely to be due to ischaemia and may

have many causes, including pleural or lung disorders,

musculoskeletal problems and anxiety.

• Character.

Cardiac pain is typically dull, constricting,

choking or ‘heavy’, squeezing, crushing, burning or aching

but not sharp, stabbing, pricking, can be described as

breathlessness. Patients often emphasise that it is a

discomfort rather than a pain. They typically use

characteristic hand gestures (e.g. open hand or clenched

fist) when describing ischaemic pain .

• Provocation

.

Anginal pain occurs

during (not after)

exertion, promptly relieved (<5 minutes) by rest, may be

precipitated or exacerbated by emotion , exertion, large

meal or in a cold wind. In crescendo or unstable angina,

similar pain may be precipitated by minimal exertion or

at rest. The increase in venous return or preload induced

by lying down may also be sufficient to provoke pain in

vulnerable patients (decubitus angina).

The pain of MI

may be preceded by a period of stable or

unstable angina but often occurs de novo.

Pleural or pericardial pain

described as a ‘sharp’ or

‘catching’ sensation , exacerbated by breathing, coughing

or movement. Pain associated with a specific movement

(bending,stretching,turning) is likely to be

musculoskeletal

.

• Onset

.

The pain of MI typically takes several minutes or

longer to develop; similarly, angina builds up gradually in

proportion to the intensity of exertion.

The pain of aortic dissection, massive pulmonary

embolism or pneumothorax is usually very sudden or

instantaneous in onset.

Pain that occurs after rather than during exertion is usually

musculoskeletal or psychological in origin.

• Associated features.

The pain of MI, massive pulmonary

embolism or aortic dissection is often accompanied by

autonomic disturbance, including sweating, nausea and

vomiting.

Breathlessness, due to pulmonary congestion arising from

transient ischaemic left ventricular dysfunction, is often a

prominent and occasionally the dominant feature of MI or

angina (

angina equivalent

). Breathlessness

may also accompany any of the respiratory causes

of chest pain and can be associated with cough, wheeze or

other respiratory symptoms. Gastrointestinal disorders, such

as gastrooesophageal reflux, peptic ulceration or biliary

colic, may present with chest pain but effort-related

‘indigestion’ is usually due to heart disease.

Myocarditis and pericarditis

Pain is characteristically felt retrosternally, to the left of

the sternum, or in the left or right shoulder, and typically

varies in intensity with movement and the phase of

respiration. The pain is described as ‘sharp’ and may

‘catch’the patient during inspiration, coughing or lying

flat; there may be a history of a prodromal viral illness.

Mitral valve prolapse

Sharp left-sided chest pain that is suggestive of a

Musculoskeletal problem may be a feature of prolapse .

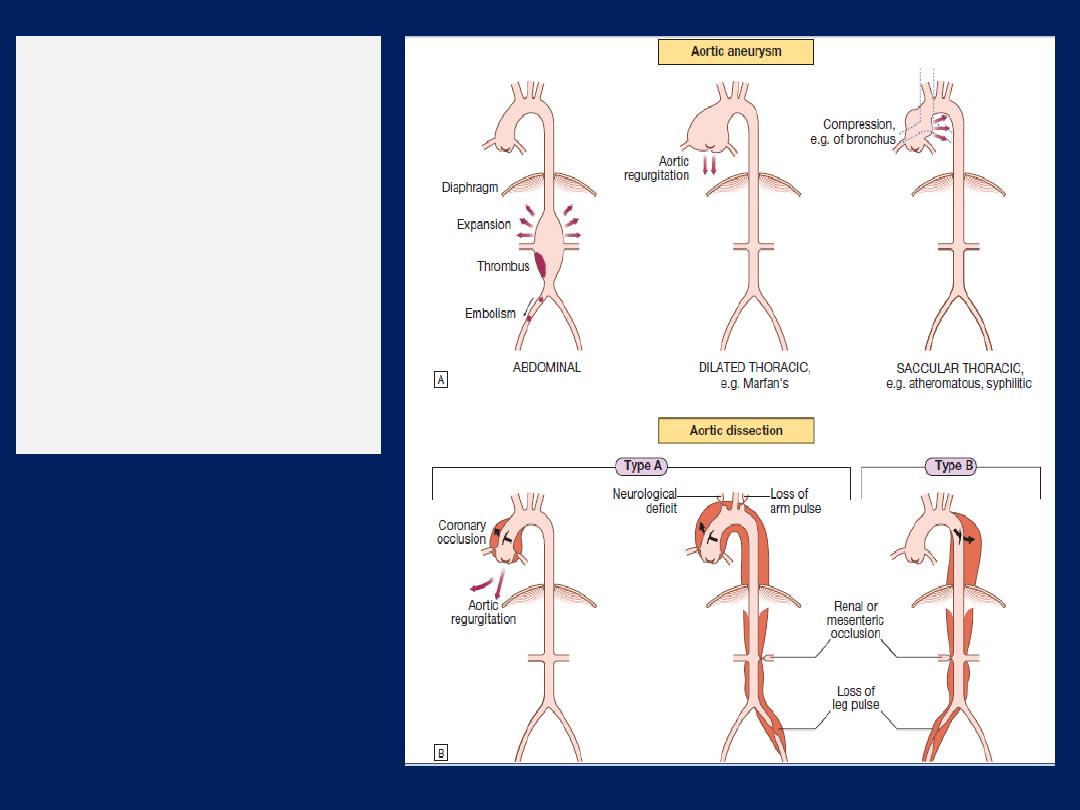

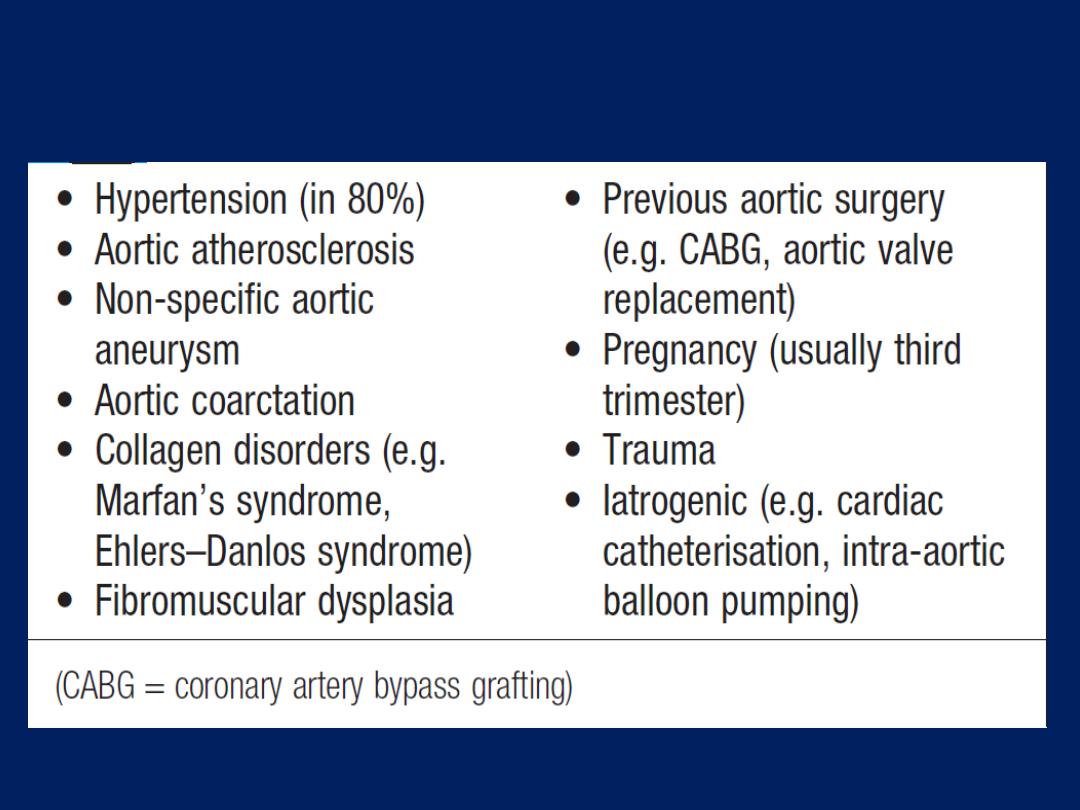

Aortic dissection

This pain is severe, sharp and tearing, is often felt in or

penetrating through to the back, typically very abrupt in

onset .The pain follows the path of the dissection.

Oesophageal pain

This can mimic the pain of angina very closely, is sometimes

precipitated by exercise and may be relieved by

nitrates. However, it is usually possible to elicit a history

relating chest pain to supine posture or eating, drinking

or oesophageal reflux. It often radiates to the

interscapular region and dysphagia may be present.

Bronchospasm

Patients with reversible airways obstruction, such as

asthma, may describe exertional chest tightness that is

relieved by rest. This may be difficult to distinguish from

ischaemic chest tightness. Bronchospasm may be associated

with wheeze, atopy and cough .

Musculoskeletal chest pain

This is a common problem that is very variable in site

and intensity but does not usually fall into any of the

patterns described above. The pain may vary with

posture or movement of the upper body and is sometimes

accompanied by local tenderness over a rib or costal

cartilage. There are numerous causes, including arthritis,

costochondritis, intercostal muscle injury and Coxsackie viral

infection (epidemic myalgia or Bornholm disease). Many

minor soft tissue injuries are related to everyday activities,

such as driving, manual work and sport.

Initial evaluation of suspected cardiac pain

A careful history is crucial in determining whether pain

is cardiac or not. Although the physical findings and

subsequent investigations may help to confirm the

diagnosis, they are of more value in determining the

nature and extent of any underlying heart disease,

the risk of a serious adverse event, and management.

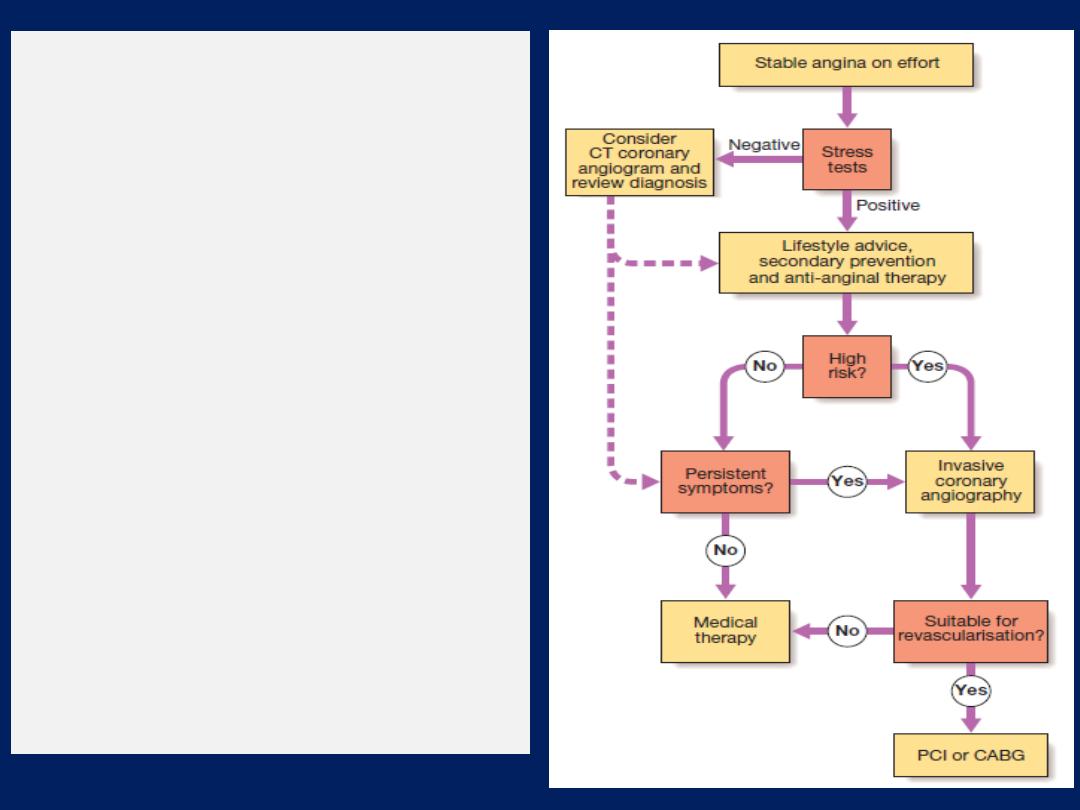

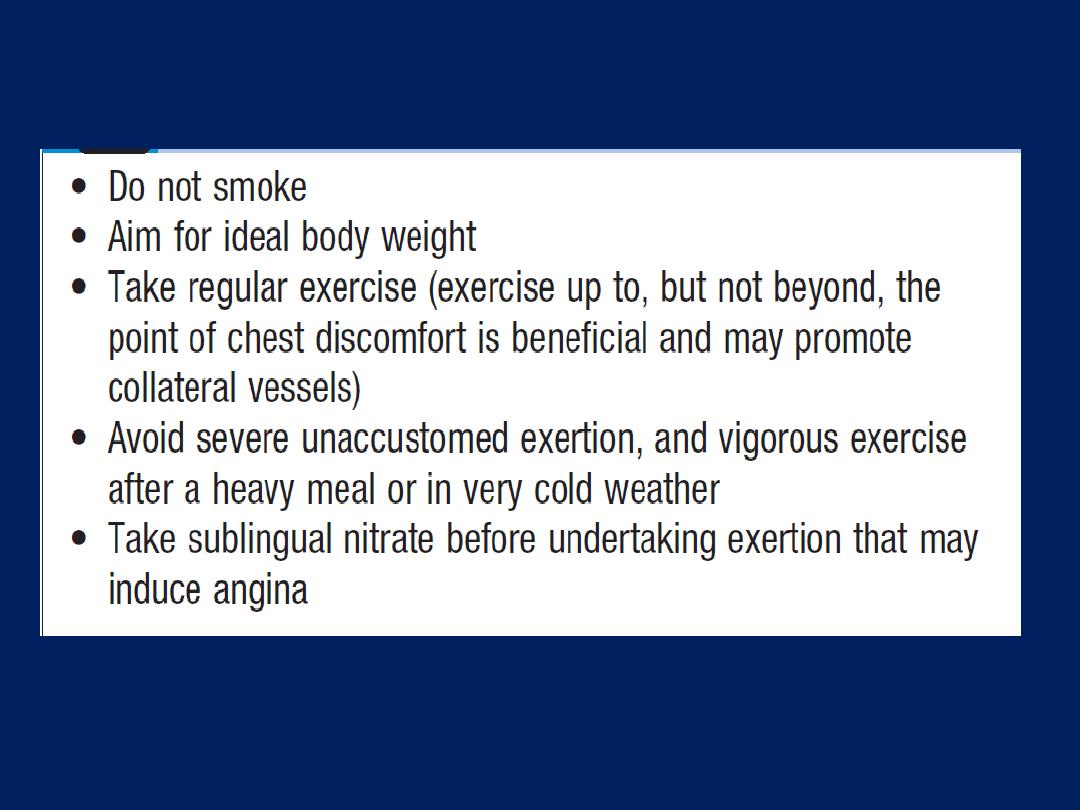

Stable angina

Effort-related chest pain is the hallmark of angina

pectoris or ‘choking in the chest’ . The reproducibility,

predictability and relationship to physical exertion (and

emotion) of the chest pain are the most important features.

The duration of symptoms should be noted because patients

with recent-onset angina are at greater risk than those with

long-standing and unchanged symptoms.

Physical examination is often normal but may reveal

evidence of risk factors (e.g. xanthoma, left ventricular

dysfunction (e.g. dyskinetic apex beat, gallop rhythm),

manifestations of arterial disease (e.g. bruits, signs of

peripheral vascular disease) and conditions that

exacerbate angina (e.g. anaemia, thyroid disease).

Stable angina is usually a symptom of CAD but may be a

manifestation of other forms of heart disease, aortic valve

disease and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

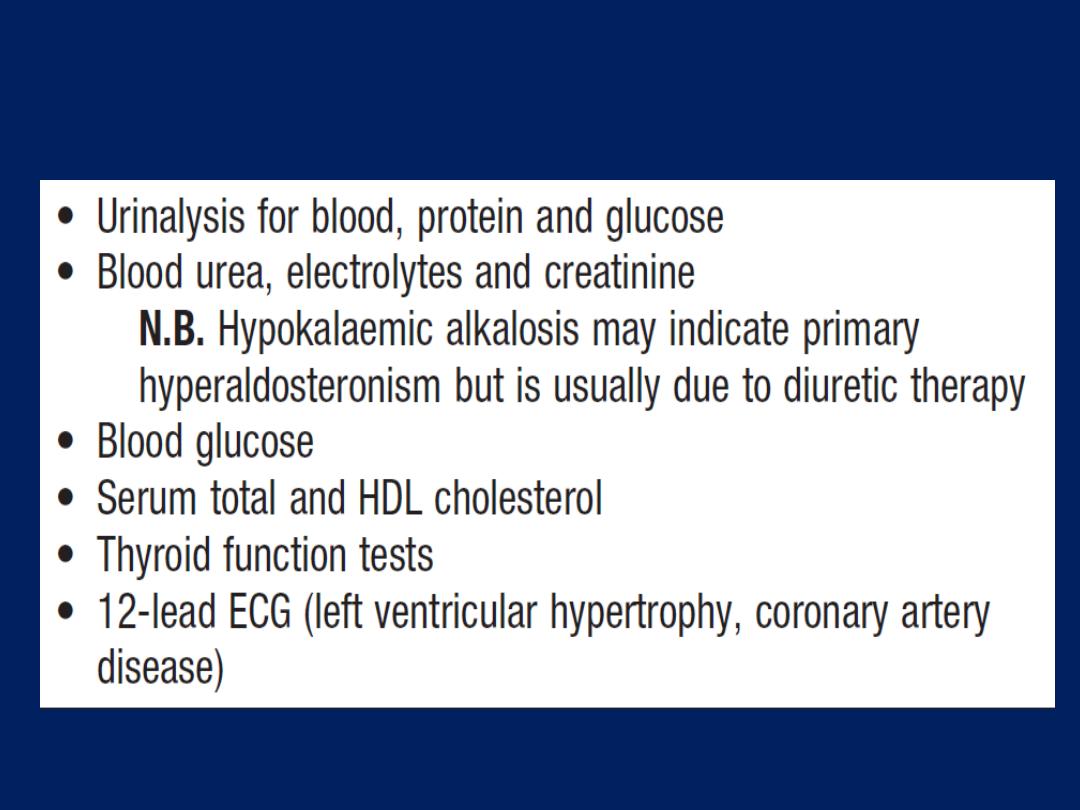

Investigations

A full blood count, fasting blood glucose, lipids, thyroid

tests and ECG. Exercise testing may confirm the diagnosis

and also identify high-risk patients .CT angiography is very

useful to exclude the presence CAD where doubt exists.

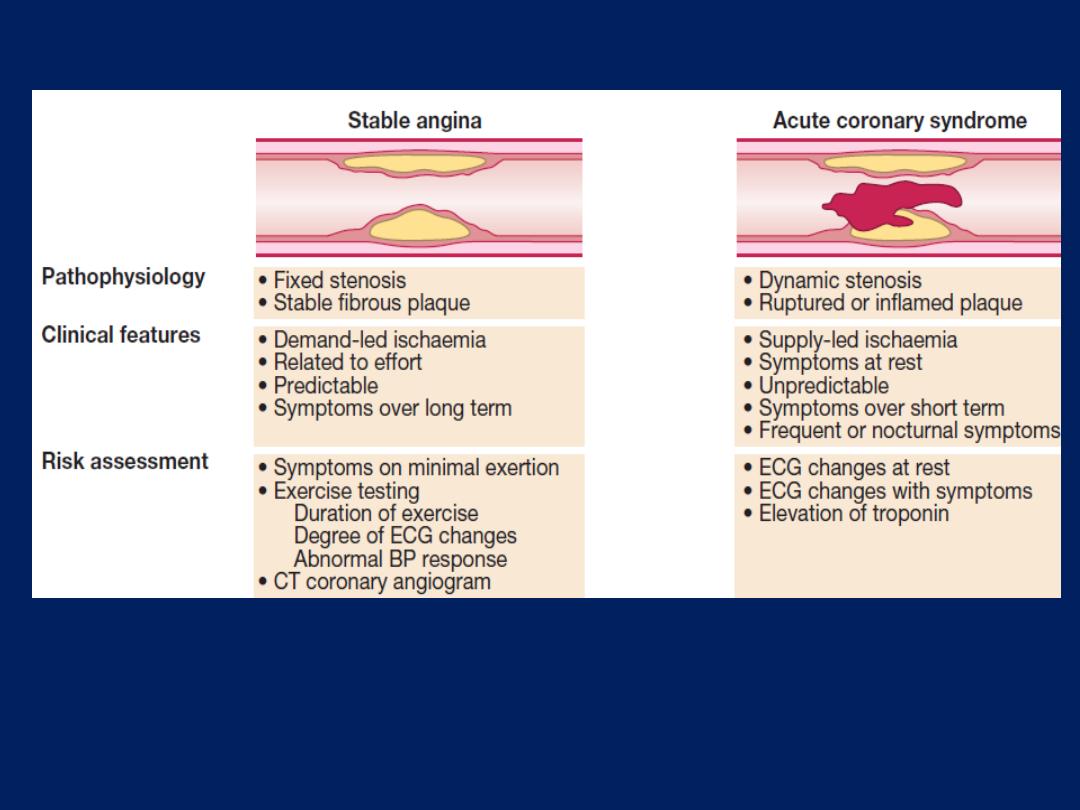

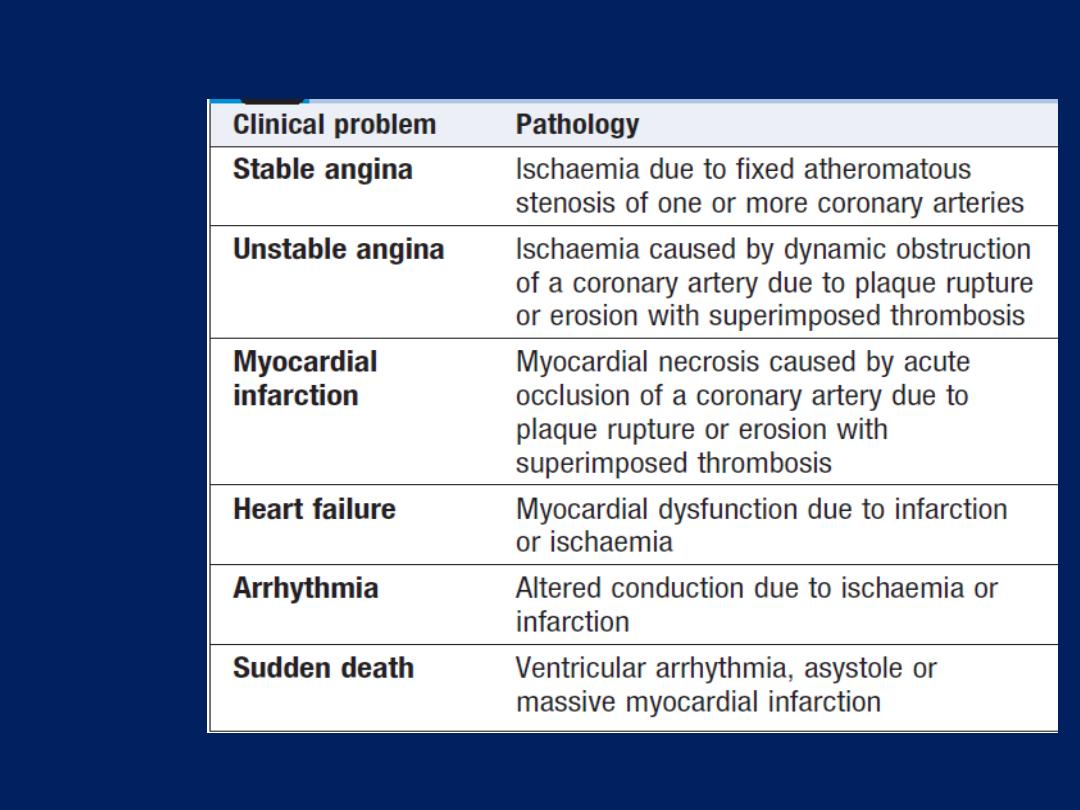

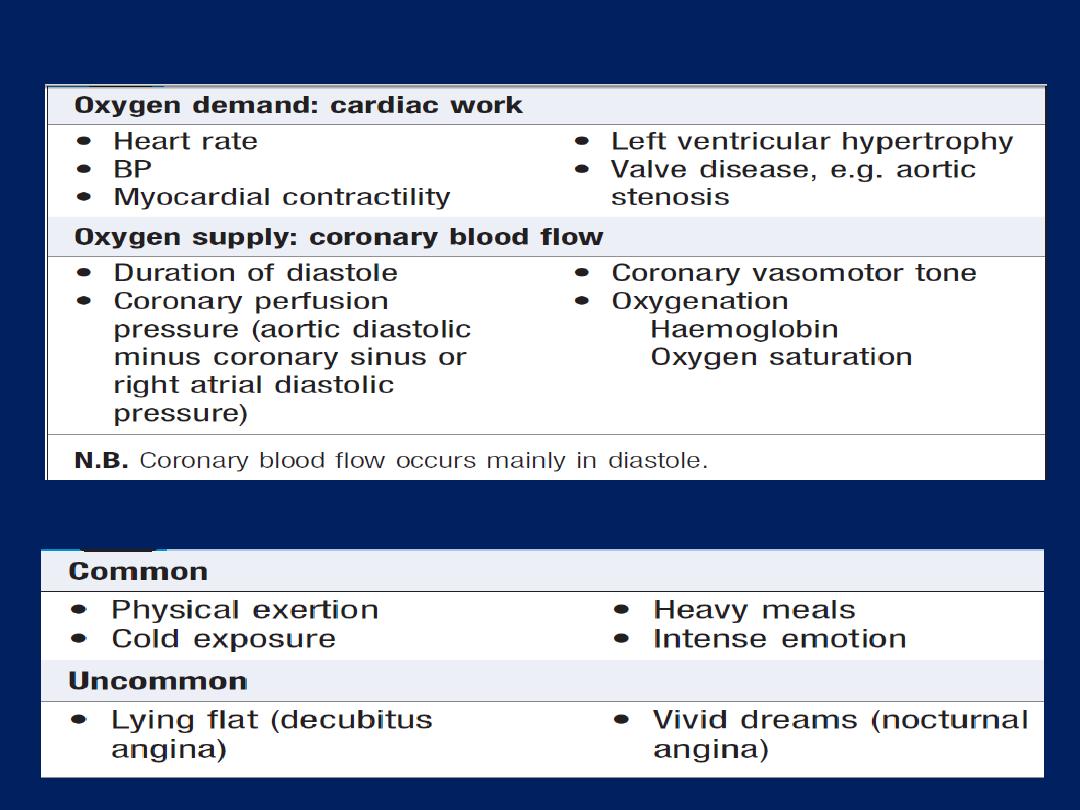

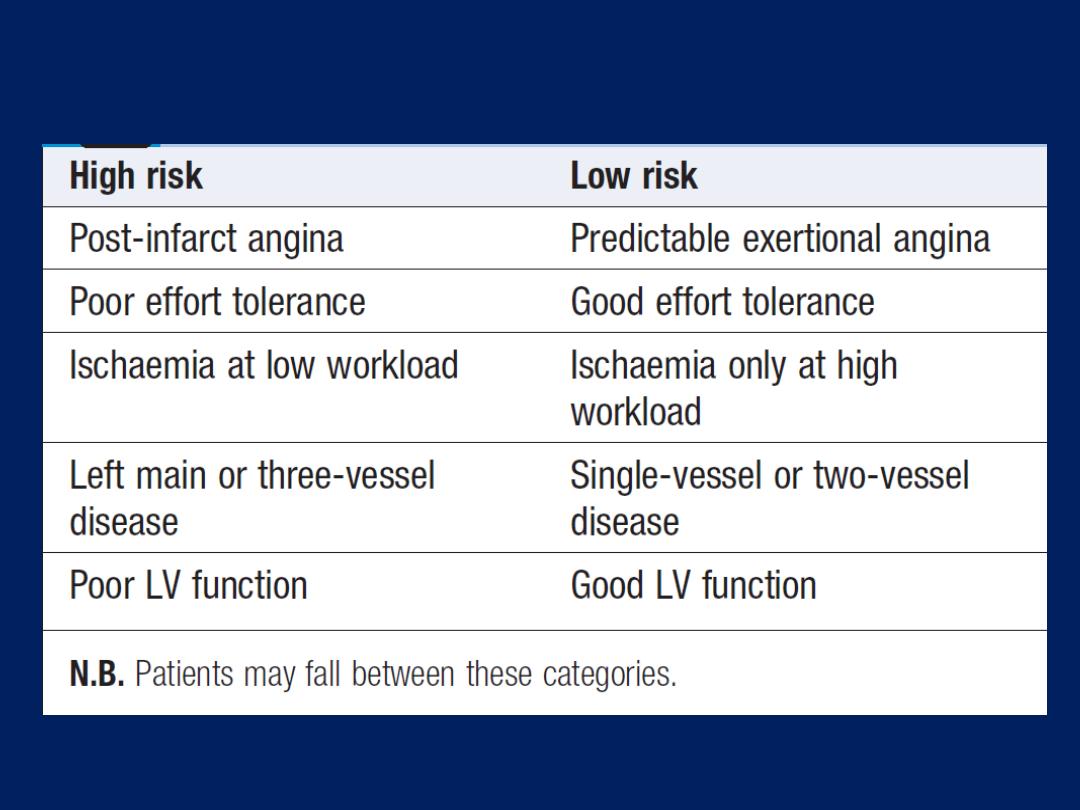

Pathophysiology, clinical features and risk assessment of

patients with stable or unstable coronary heart disease.

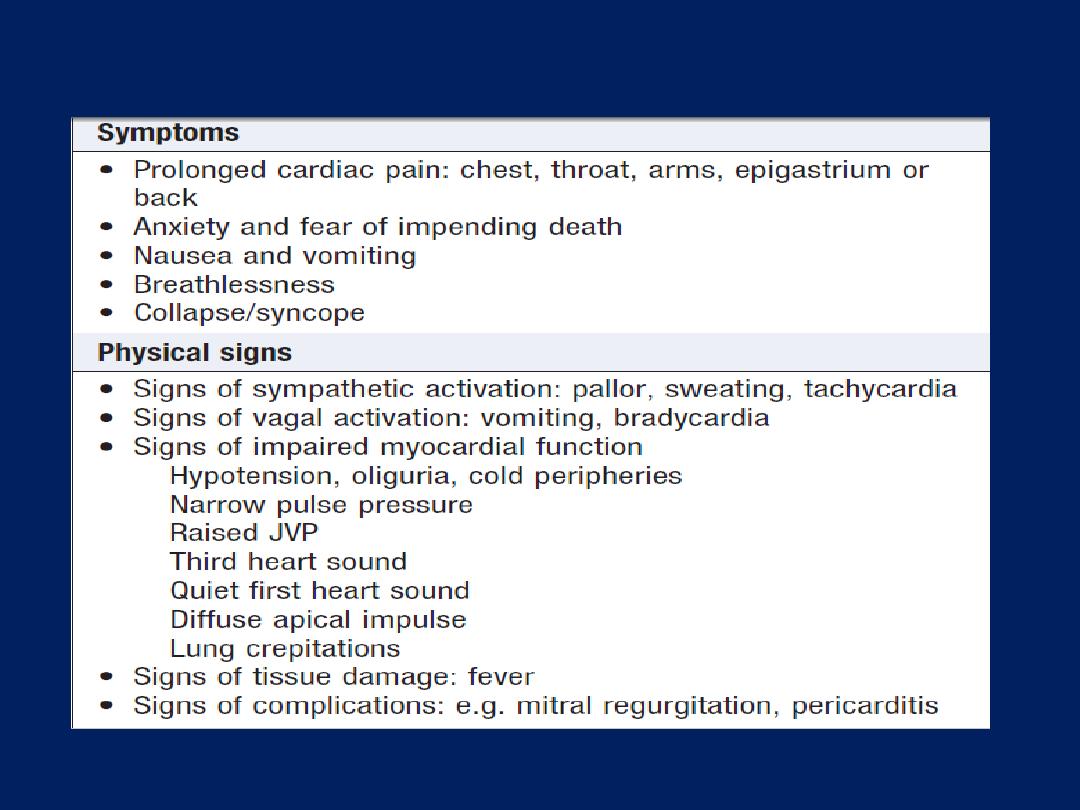

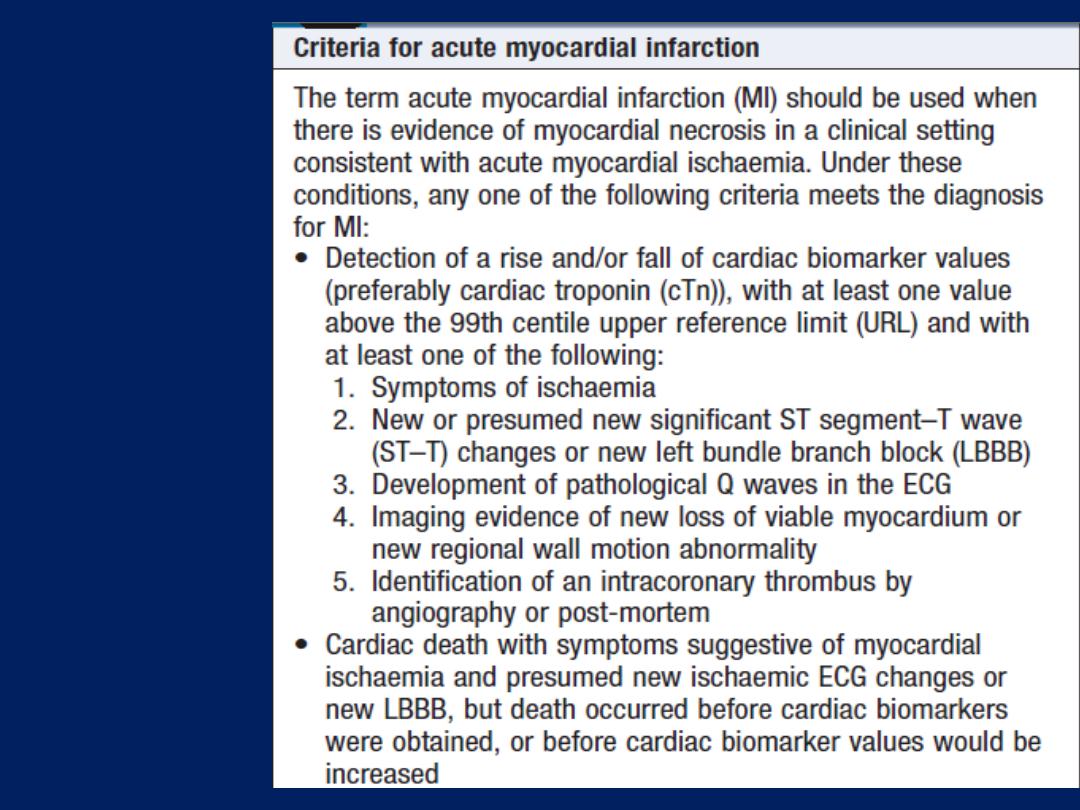

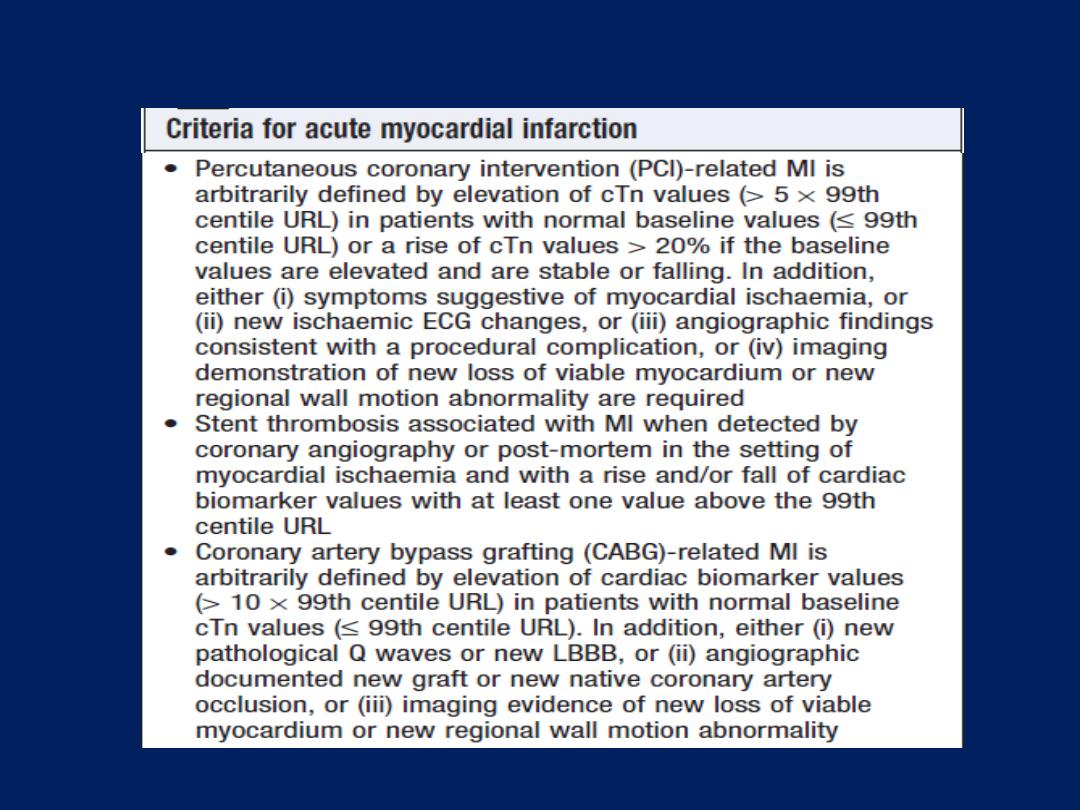

Acute coronary syndromes (ACS)

Prolonged

,

severe

chest pain may be due to unstable

angina (recent-onset limiting, rapidly worsening or

crescendo angina, and angina at rest) or acute MI; known

collectively as the ACS. Although there may be a history of

chronic stable angina, an episode is often the first

presentation of CAD . Patients presenting with symptoms

consistent with an ACS require

urgent

evaluation because

there is a high risk of avoidable complications, such as

sudden death and MI. Signs of haemodynamic

compromise (hypotension, pulmonary oedema), ECG

(The most

useful method of initial triage )

ST changes and biochemical markers

of cardiac damage, such as CK, myoglobin , elevated

troponin I or T,

are

powerful indicators of short-term risk.

Repeated ECG are valuable, particularly during an

episode of pain . Plasma troponin should be measured at

presentation and, if normal, repeated 6–12 hours after

the onset.

If the

pain has not recurred, troponin not

elevated and no new ECG changes, the patient may be

discharged from hospital.

Physical examination

may reveal signs of important

comorbidity, such as peripheral or cerebrovascular

disease, autonomic disturbance (pallor or sweating) and

complications (arrhythmia or heart failure).

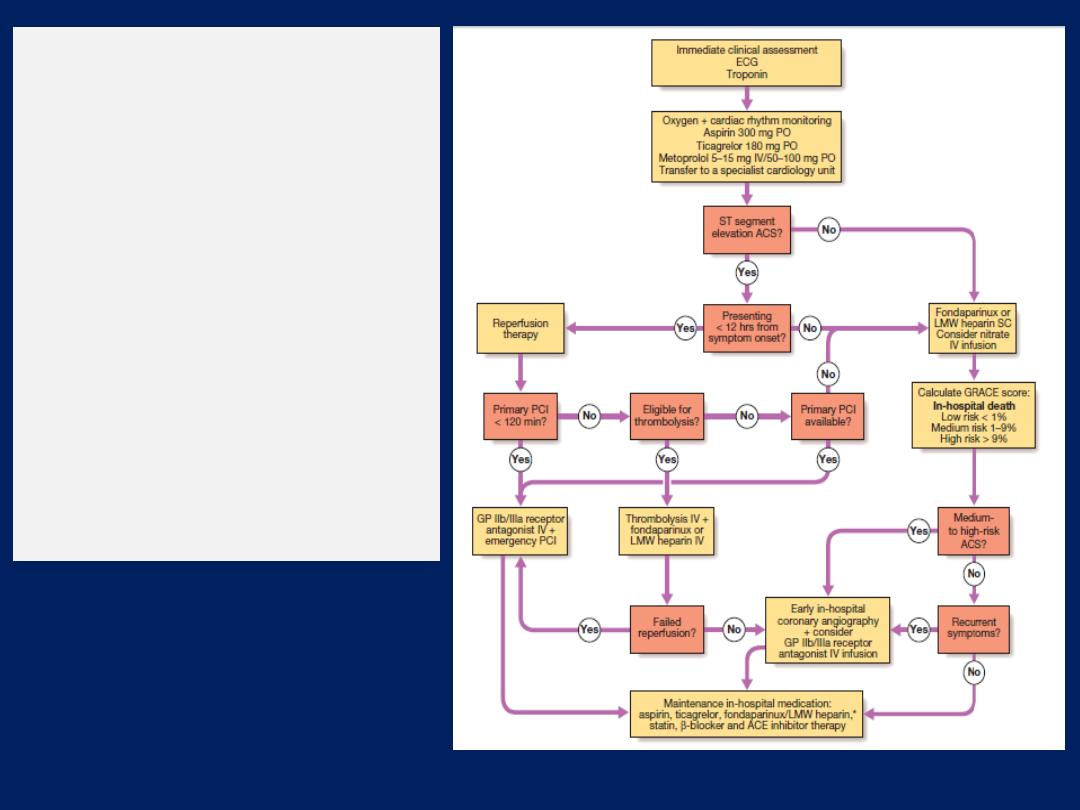

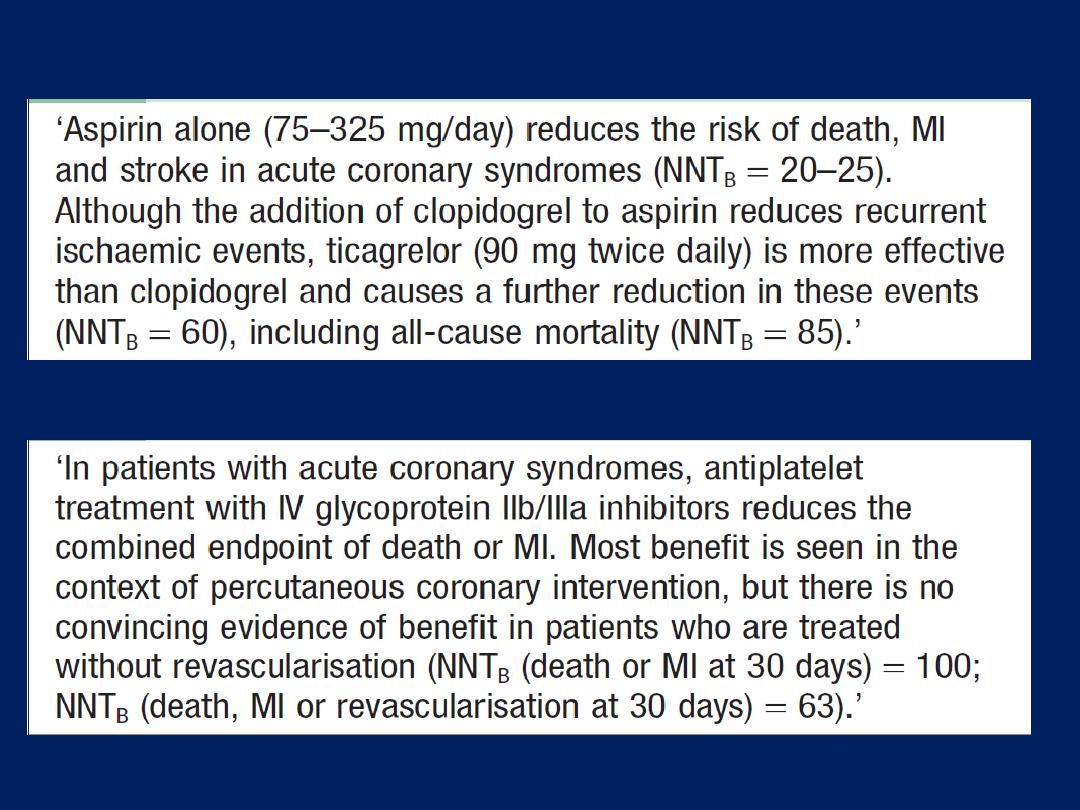

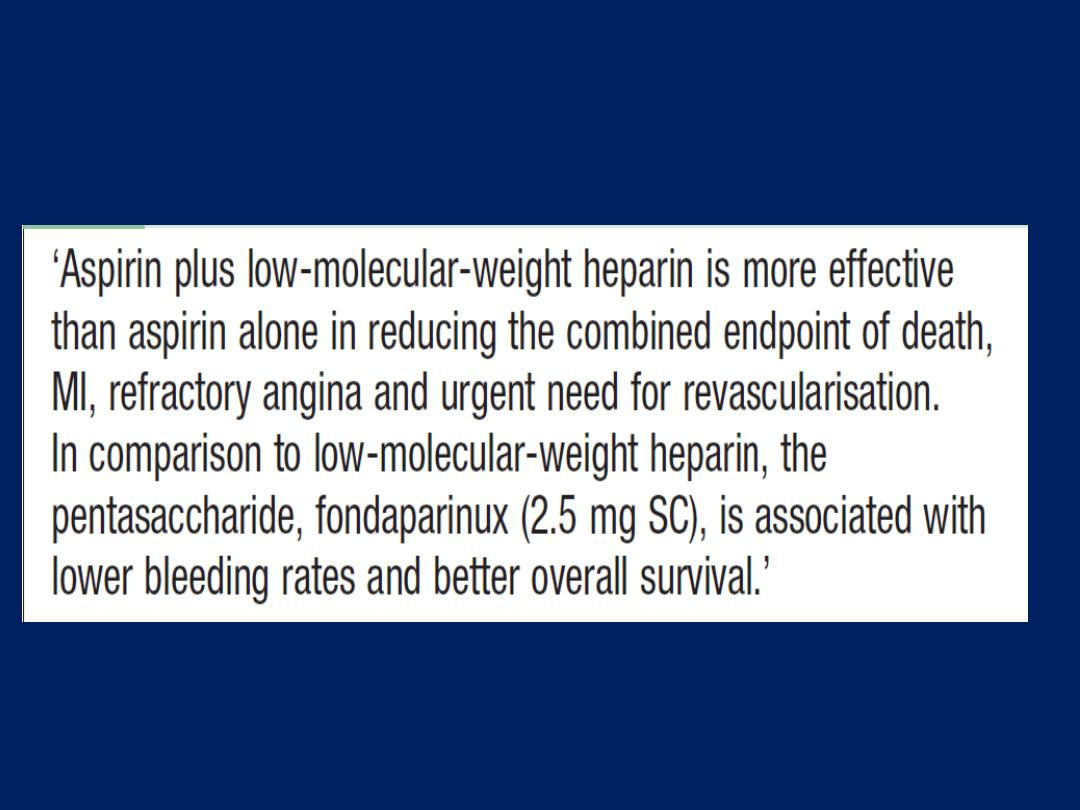

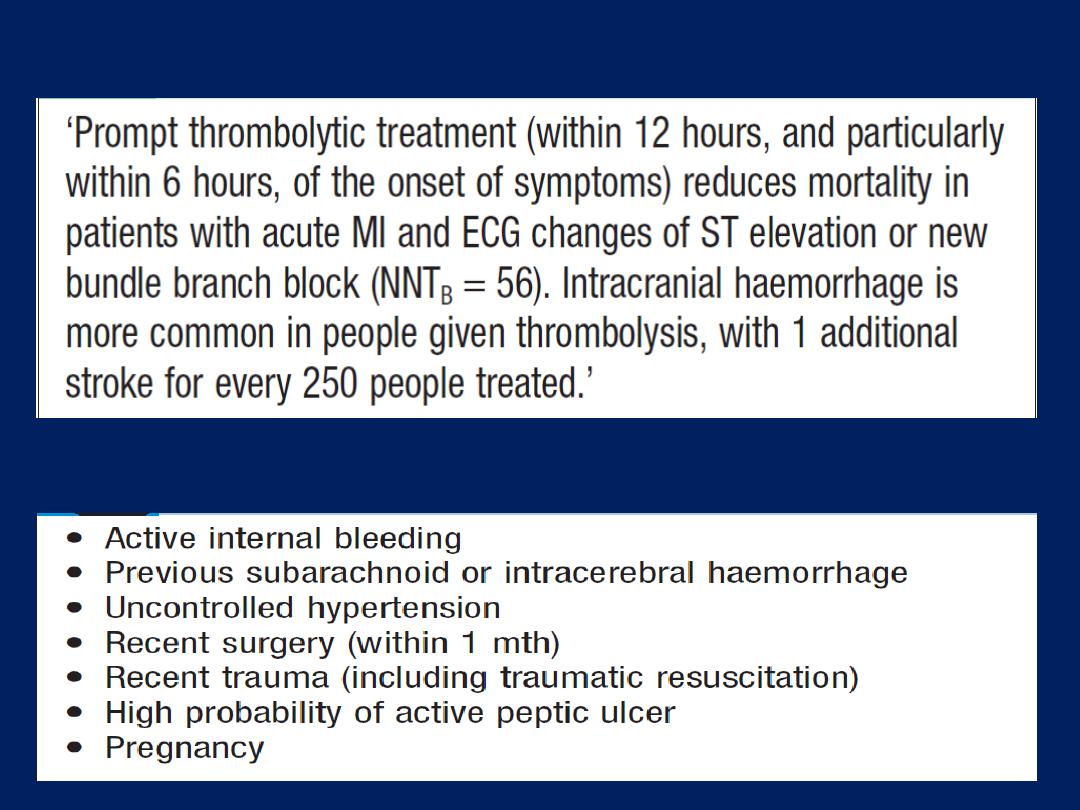

Summary of treatment for

acute coronary syndrome

(ACS). *Not required

following PCI. Amended

from SIGN 93. For details

of the GRACE score, (ACE =

angiotensin-converting

enzyme; GP =

glycoprotein; LMW = low

molecular weight;

PCI = percutaneous

coronary intervention).

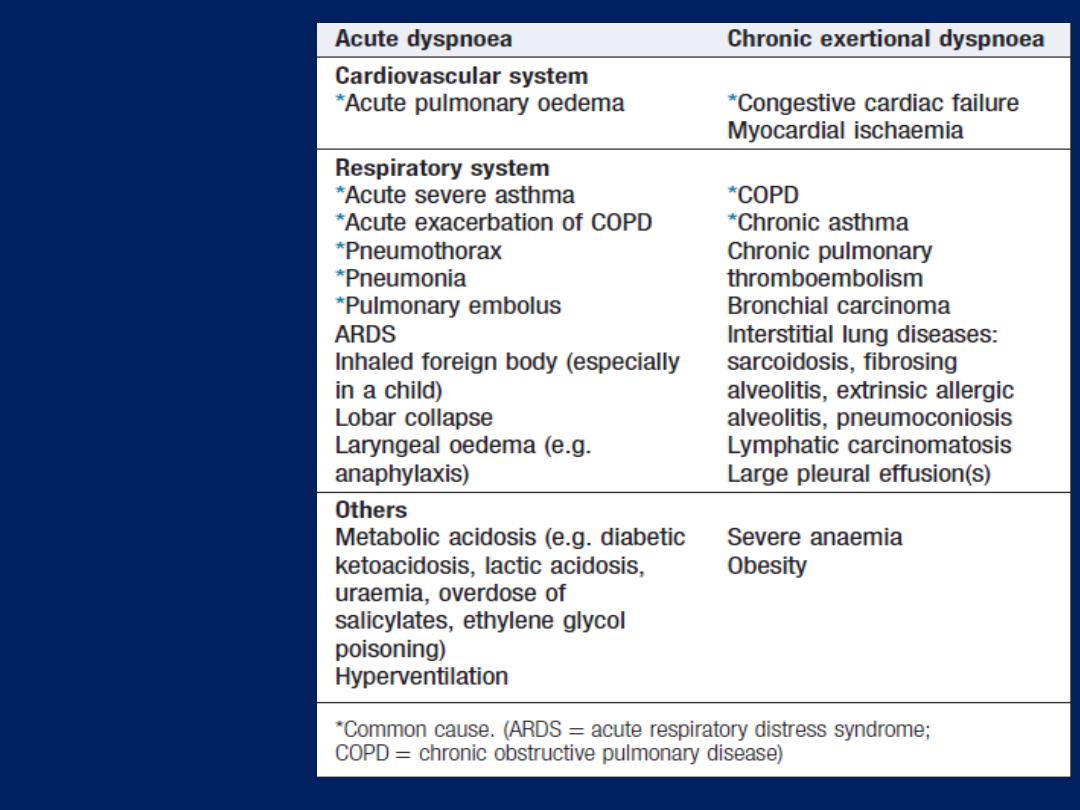

Breathlessness (dyspnoea)

Dyspnoea of cardiac origin may vary in severity from an

uncomfortable awareness of breathing to a frightening

sensation of ‘fighting for breath’. The sensation of

dyspnoea originates in the cerebral cortex.

There are several causes of cardiac dyspnoea:

acute left heart failure,

chronic heart failure,

arrhythmia and

angina equivalent .

Breathlessness (dyspnoea)

Acute left heart failure

May be triggered by a major event, such as MI, in a

previously healthy heart, or by a relatively minor event,

such as atrial fibrillation, in a diseased heart. An increase

in the LV-diastolic pressure causes the pressure in the LA,

pulmonary veins and pulmonary capillaries to rise.

When

the hydrostatic pressure of the pulmonary capillaries

exceeds the oncotic pressure of plasma (25–30 mmHg),

fluid moves from the capillaries into alveoli. This stimulates

respiration through a series of autonomic reflexes,

producing rapid shallow respiration.

Congestion of the bronchial mucosa may cause

wheeze

(cardiac asthma).

Breathlessness (dyspnoea) – cont’d

Acute pulmonary oedema

is a terrifying experience

because of the sensation of ‘fighting for breath’. Sitting

upright or standing may provide some relief by helping

to reduce congestion at the apices of the lungs.

The patient may be unable to speak and is typically

distressed, agitated, sweaty and pale.

Respiration is rapid, with recruitment of accessory muscles,

coughing and wheezing. Sputum may be profuse, frothy

and blood-streaked or pink.

Extensive crepitations and rhonchi are usually audible

and there may also be signs of right heart failure.

Breathlessness– cont’d Chronic heart failure

Is the most common cardiac cause of chronic dyspnoea.

Symptoms may first present on moderate exertion, such as

walking up a steep hill, and may be described as a

difficulty in ‘catching my breath’. As failure progresses,

the dyspnoea is provoked by less exertion and, ultimately,

the patient may be breathless walking from room to room,

washing, dressing or trying to hold a conversation.

• Orthopnoea.

Lying down increases the venous return to

the heart and provokes breathlessness. Patients may prop

themselves up with pillows to prevent this.

• Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea.

In severe heart failure,

fluid shifts from the interstitial tissues into the circulation within 1–2

hours of lying down. Pulmonary oedema supervenes, causing the

patient to wake and sit upright, profoundly breathless.

Cheyne–Stokes respiration.

This cyclical pattern of

respiration is due to impaired responsiveness of the

respiratory centre to carbon dioxide and occurs in severe

left ventricular failure. The pattern of slowly diminishing

respiration, leading to apnoea, followed by progressively

increasing respiration and hyperventilation, may be

accompanied by asensation of breathlessness and panic

during the period of hyperventilation. The Cheyne–Stokes

cycle length is a function of the circulation time.

The condition can also occur in diffuse cerebral

atherosclerosis, stroke or head injury, and may be

exaggerated by sleep, barbiturates and opiates.

Breathlessness – cont’d

Arrhythmia

Usually only does so if the heart is structurally abnormal,

such as with the onset of atrial fibrillation in mitral stenosis.

Angina equivalent :

Breathlessness is a common feature of

angina. Patients will sometimes describe chest tightness as

‘breathlessness’.

However, myocardial ischaemia may also induce true

breathlessness by provoking transient left V dysfunction or

heart failure.

When

breathlessness is the dominant or sole feature of

myocardial ischaemia, it is

known as ‘angina equivalent’.

Some causes

of dyspnoea

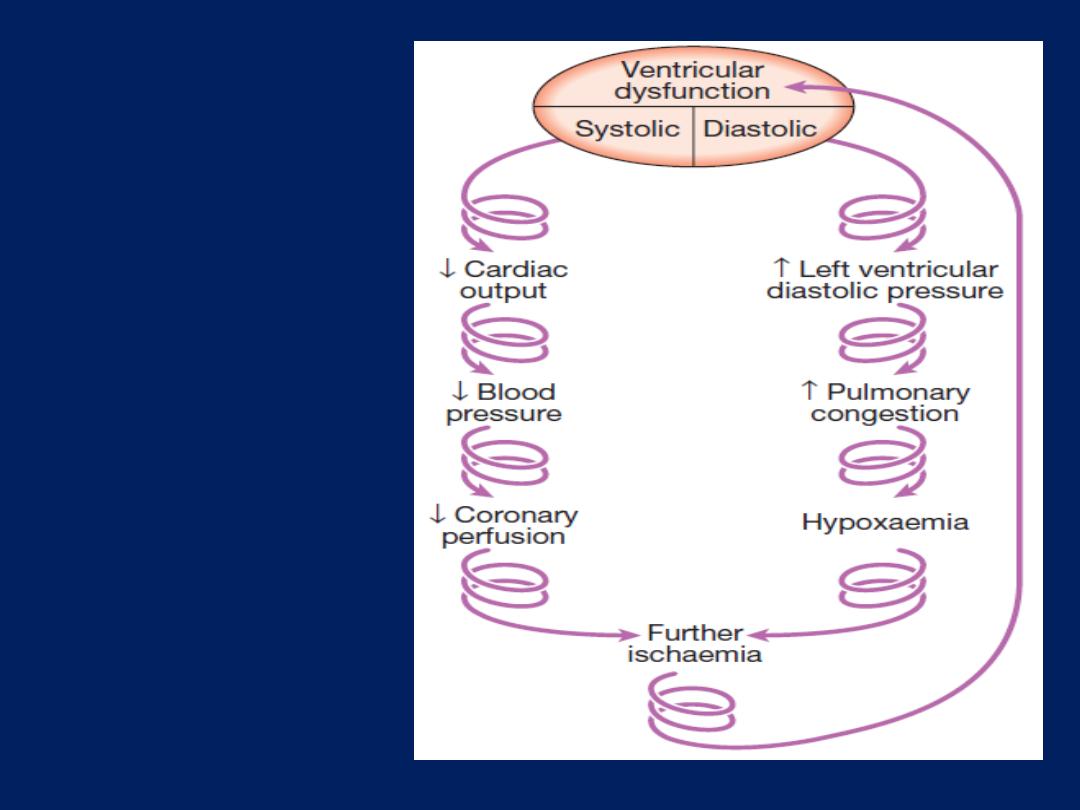

Acute circulatory failure (cardiogenic shock)

‘Shock’ is used to describe the clinical syndrome that

develops when there is critical impairment of tissue

perfusion due to some form of acute circulatory failure.

There are numerous causes of shock.

Myocardial infarction

Shock in acute MI is due to left ventricular dysfunction

in more than 70% of cases. However, it may also be due

to infarction of the RV and a variety of mechanical

complications, including tamponade (due to infarction and

rupture of the free wall), an acquired VSD (due to

infarction and rupture of the septum) and

acute mitral regurgitation (due to infarction or rupture

of the papillary muscles).

Severe myocardial systolic dysfunction causes a fall

in cardiac output, BP and coronary perfusion pressure.

Diastolic dysfunction causes a rise in left ventricular

end-diastolic pressure, pulmonary congestion and

oedema, leading to hypoxaemia that worsens myocardial

ischaemia. This is further exacerbated by peripheral

vasoconstriction.

These factors combine to create the

‘downward spiral’ of cardiogenic shock.

Hypotension,

oliguria, confusion and cold, clammy peripheries are the

manifestations of a low cardiac output, whereas

breathlessness, hypoxaemia, cyanosis and inspiratory

crackles at the lung bases are typical features of

pulmonary oedema. A chest X-ray may reveal signs of

pulmonary congestion when clinical examination is normal.

The downward

spiral of

cardiogenic

shock.

If necessary, a Swan– Ganz catheter can be used to

measure the pulmonary artery wedge pressure and to

guide fluid replacement.

The findings can be used to categorise patients with acute

MI into four haemodynamic subsets. Those with

cardiogenic shock should be considered for immediate

coronary revascularisation.

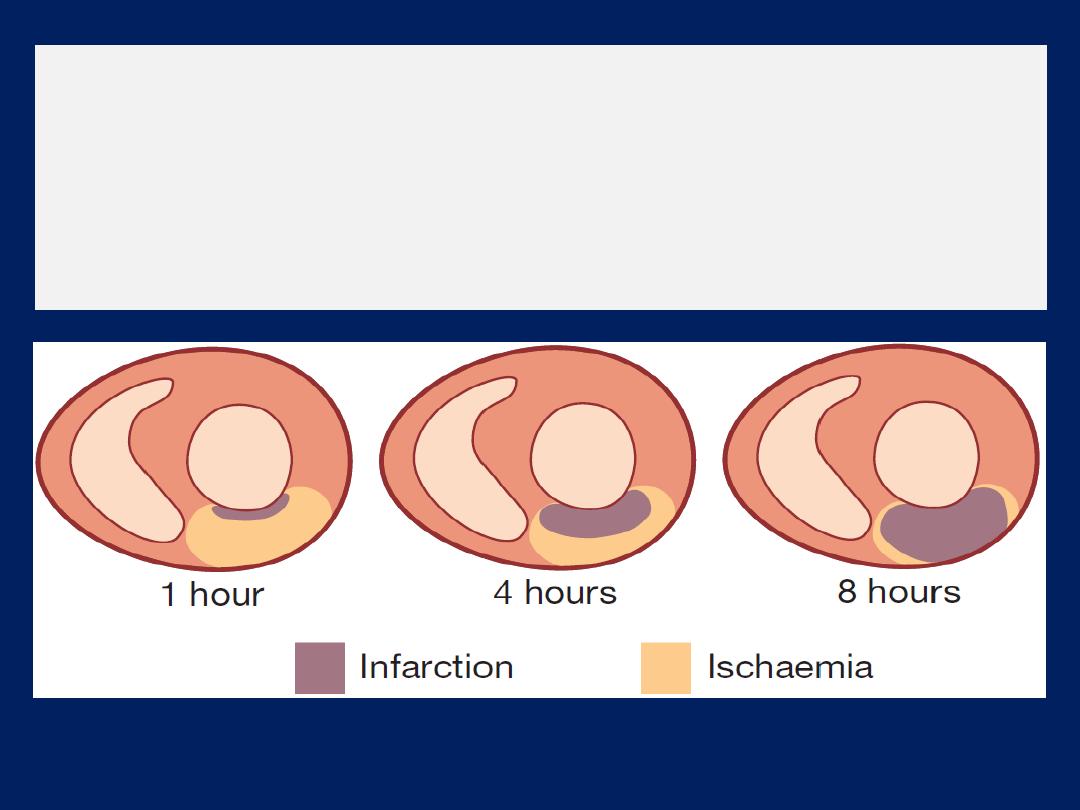

The viable myocardium surrounding a fresh infarct

may contract poorly for a few days and then recover.

This phenomenon is known as

myocardial stunning

and means that acute heart failure should be treated

intensively because overall cardiac function may

subsequently improve.

Acute circulatory failure (cardiogenic shock) – cont’d

Acute massive pulmonary embolism

This may complicate leg or pelvic vein thrombosis and

usually presents with sudden collapse. Bedside echo may

demonstrate a small, underfilled, vigorous LV with a dilated

RV; it is sometimes possible to see thrombus in the right

ventricular outflow tract or main pulmonary artery.

CT pulmonary angio usually provides a definitive diagnosis.

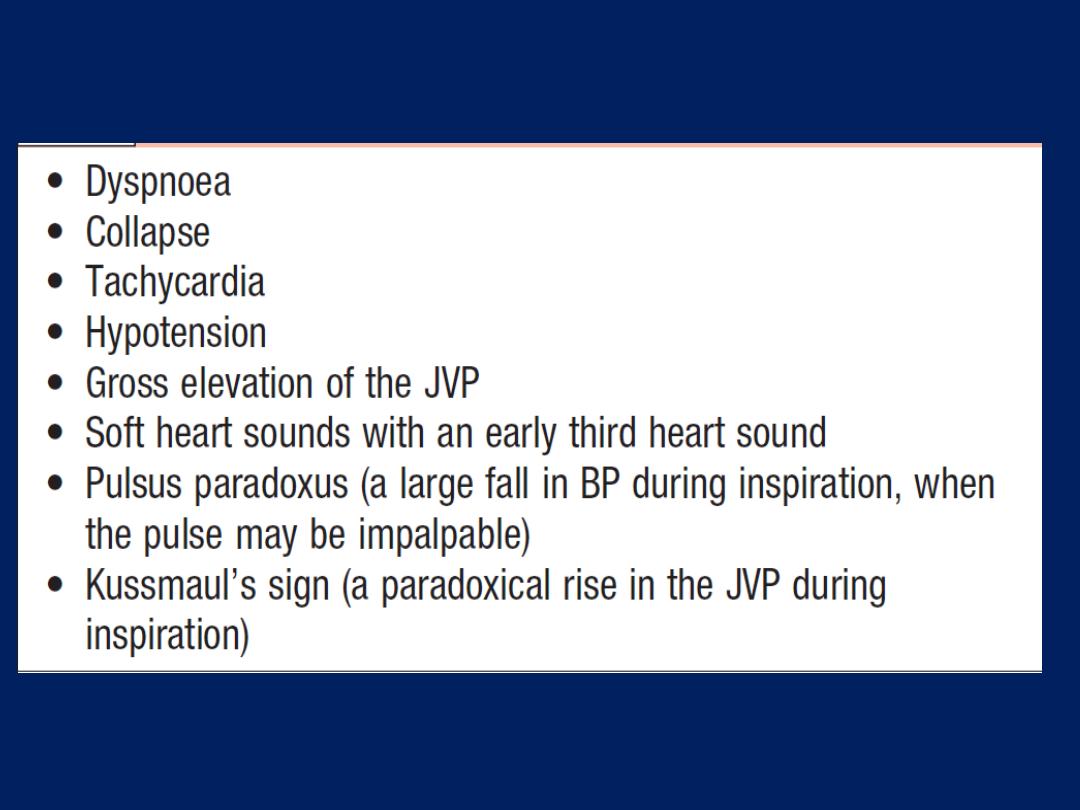

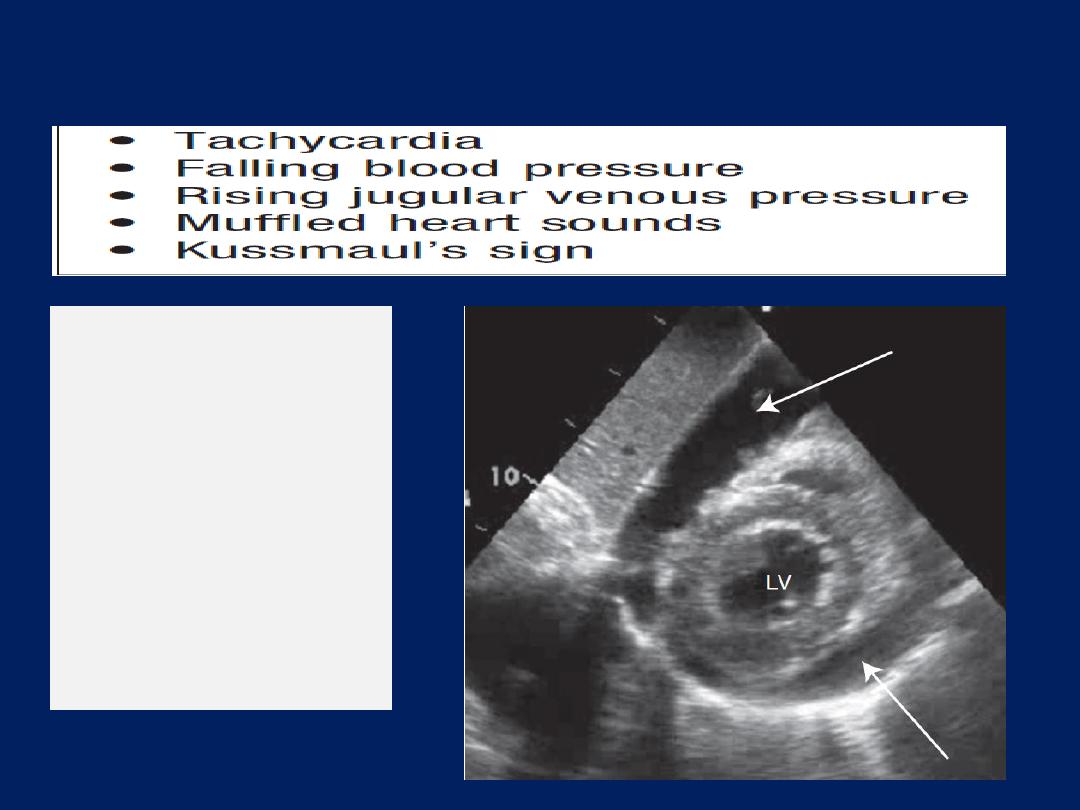

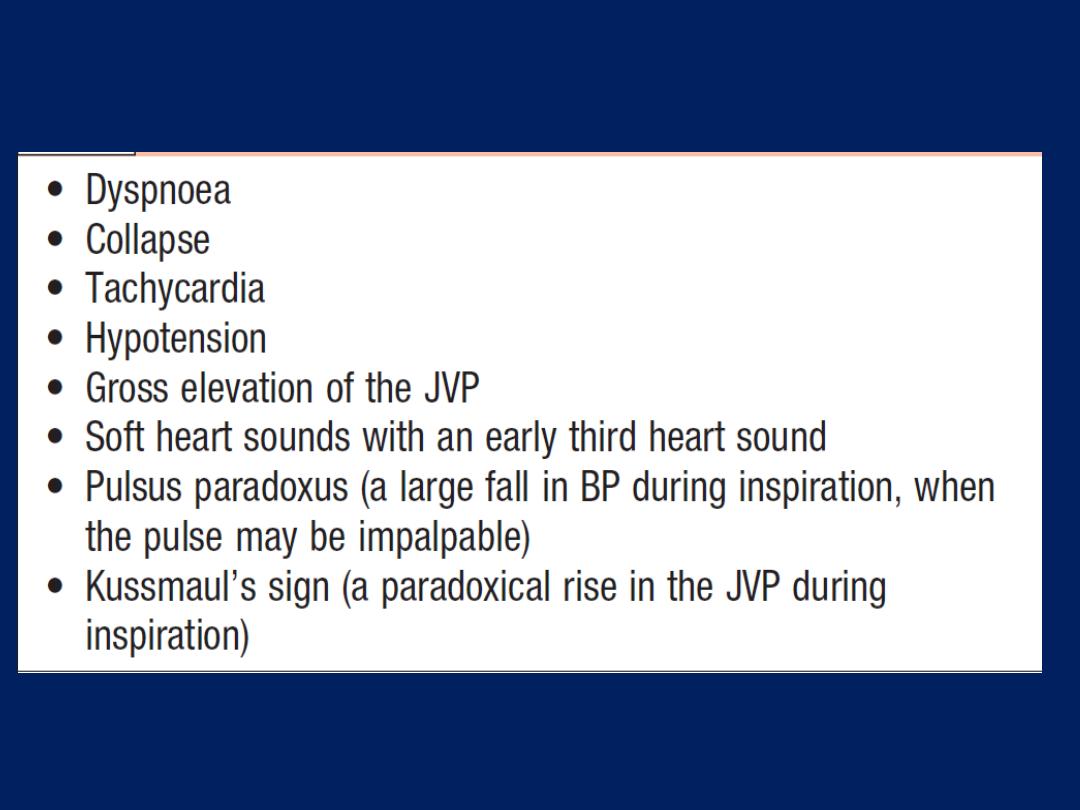

Cardiac tamponade

This is due to a collection of fluid or blood in the pericardial

sac, compressing the heart; the effusion may be small <100

mL. Sudden deterioration may be due to bleeding into the

pericardial space. Tamponade may complicate any form

of pericarditis but can be caused by malignant disease.

Other causes

include trauma and rupture of the free wall

of the myocardium following MI. An ECG may show

features of the underlying disease, such as pericarditis or

acute MI. When there is a large pericardial effusion, the

ECG complexes are small and there may be electrical

alternans: a changing axis with alternate beats caused by

the heart swinging from side to side in the pericardial fluid.

A chest X-ray shows an enlarged globular heart but can

look normal.

Echo is the best way of confirming the diagnosis and helps

to identify the optimum site for aspiration of the fluid.

Prompt recognition of tamponade is important because the

patient usually responds dramatically to percutaneous

pericardiocentesis or surgical drainage.

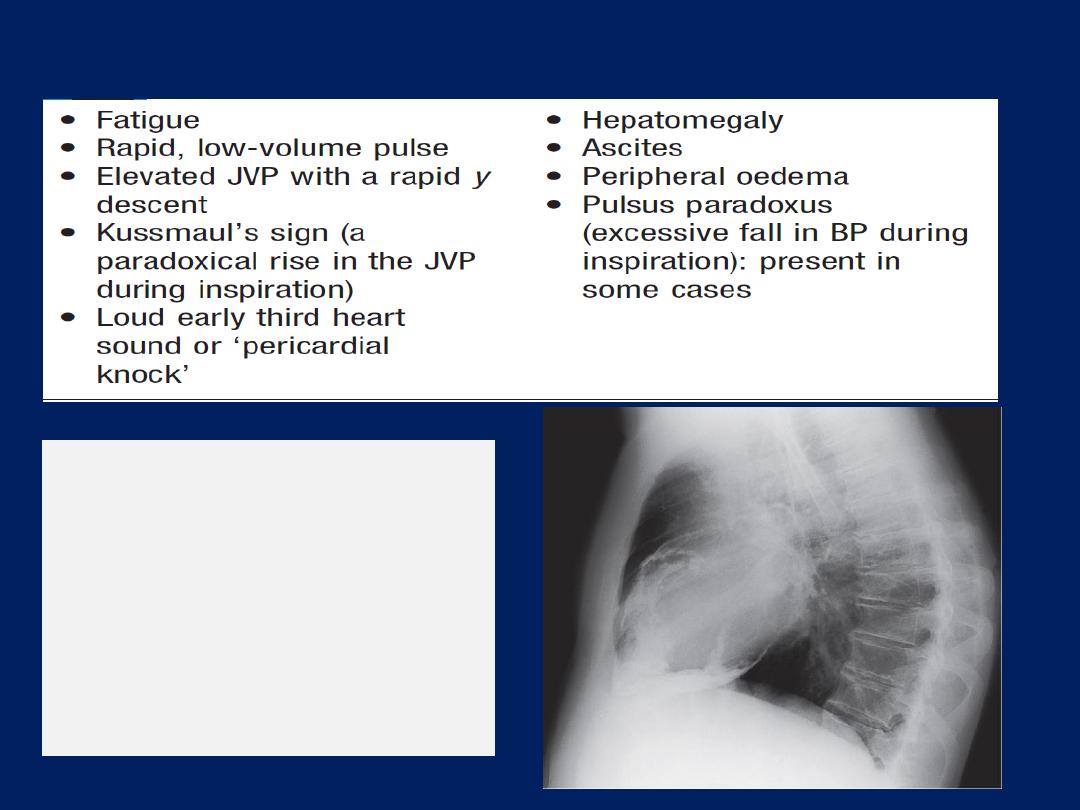

Clinical features of pericardial tamponade

Acute circulatory failure (cardiogenic shock) – cont’d

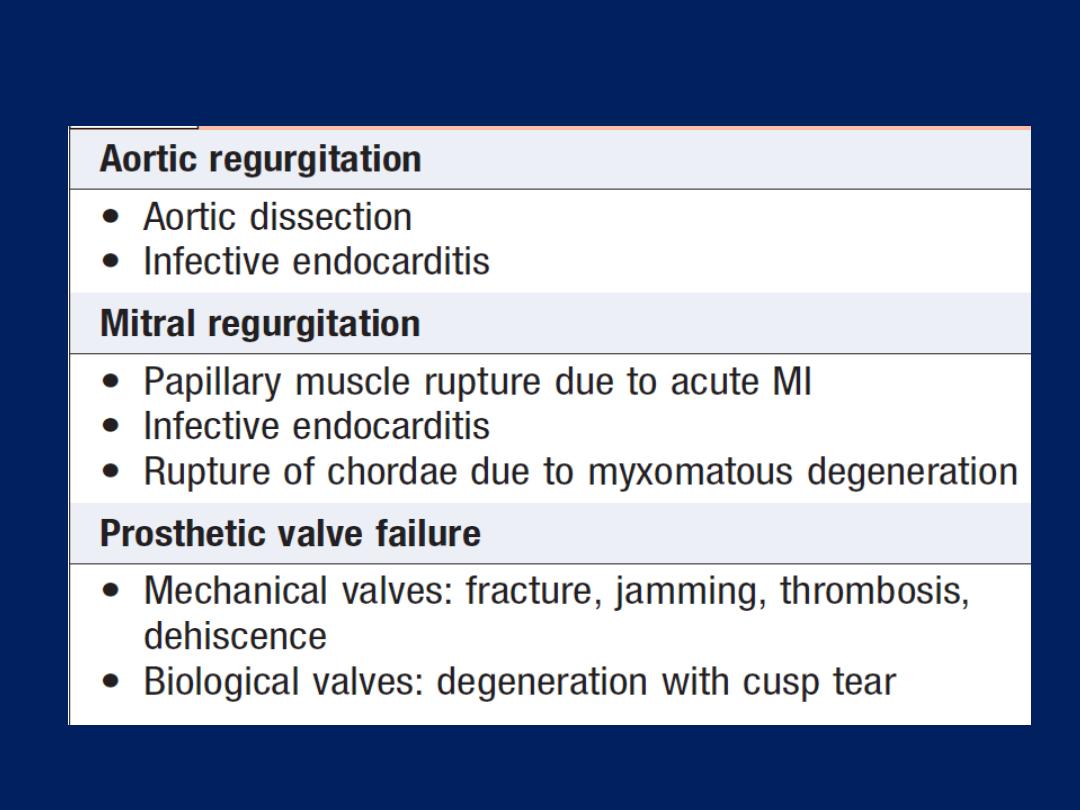

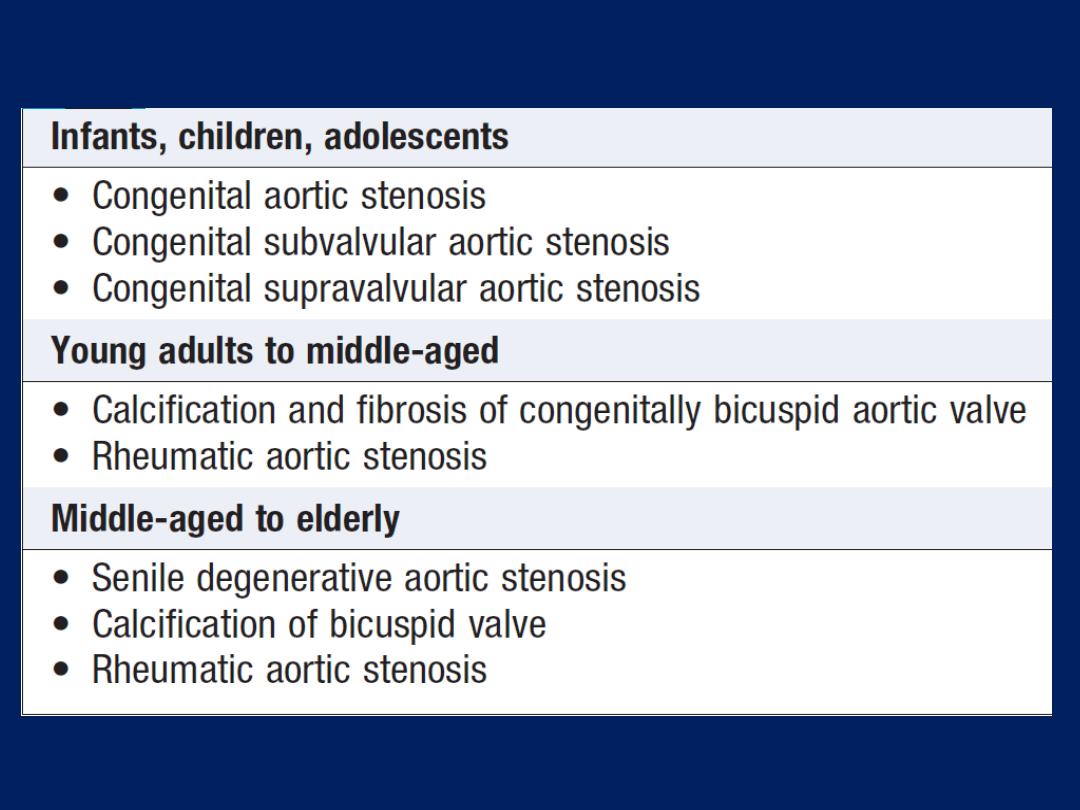

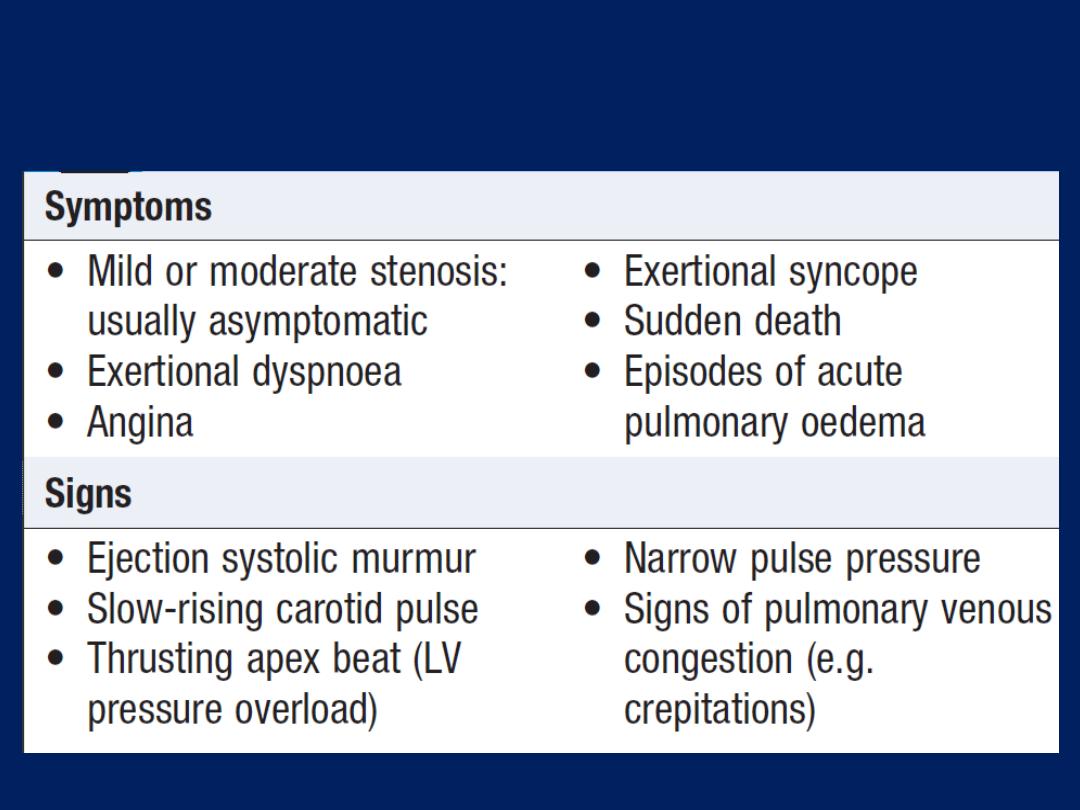

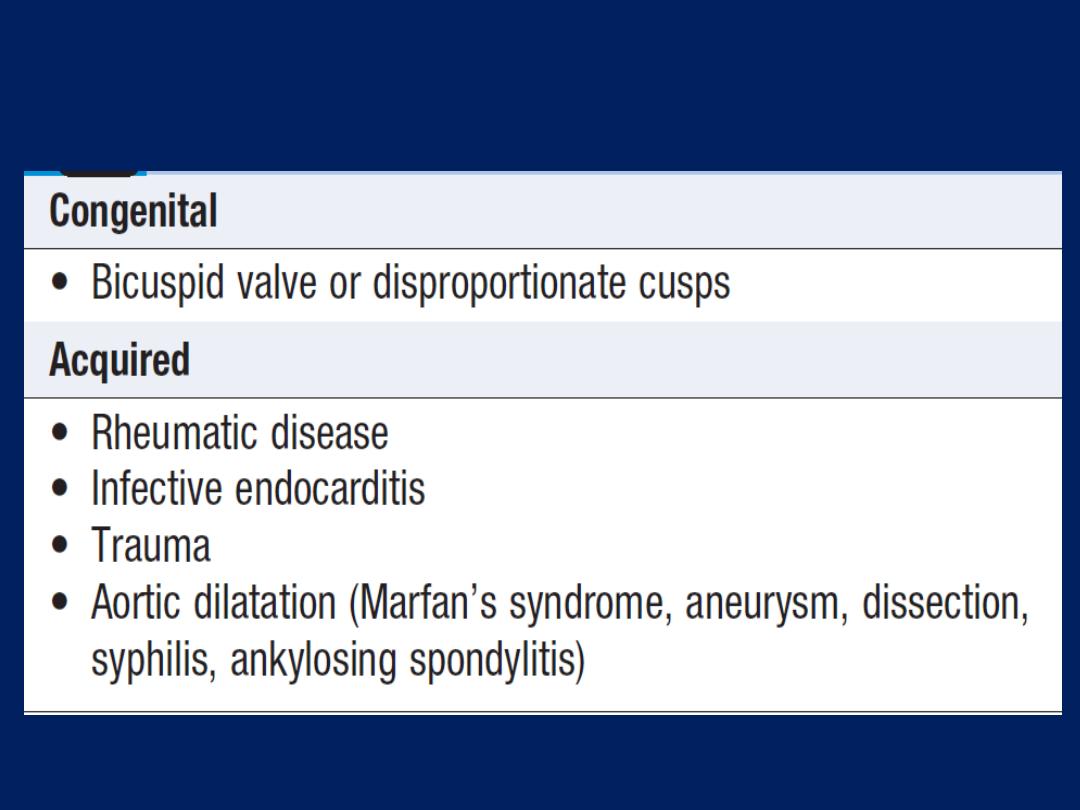

Valvular heart disease

Acute left ventricular failure and shock may be due to

the sudden onset of aortic, mitral regurgitation or prosthetic

valve dysfunction . Murmurs are often unimpressive because

there is usually a tachycardia and a low cardiac output.

Transthoracic echo will establish the diagnosis in most cases;

however, transoesophageal echo is sometimes required,

especially in prosthetic mitral valves. Patients with acute

valve failure usually require cardiac surgery.

Aortic dissection may lead to shock by causing aortic

regurgitation, coronary dissection, tamponade .

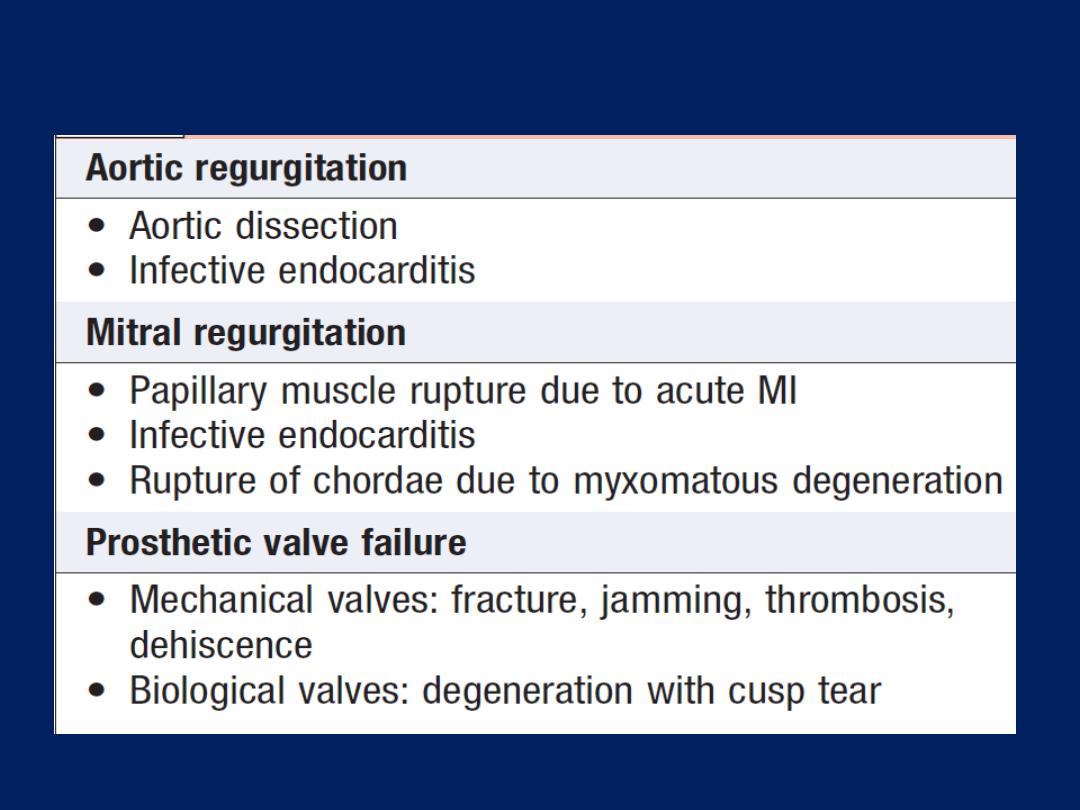

Causes of acute valve failure

Heart failure

Heart failure describes the clinical syndrome that develops

when the heart cannot maintain adequate output, or can

do so only at the expense of elevated ventricular filling

pressure. In mild to moderate forms of heart failure,

cardiac output is normal at rest and only becomes

impaired when the metabolic demand increases during

exercise or some other form of stress. In practice, heart

failure may be diagnosed when a patient with significant

heart disease develops the signs or symptoms of a low

cardiac output, pulmonary congestion or systemic

venous congestion. Almost all forms of heart disease can

lead to heart failure.

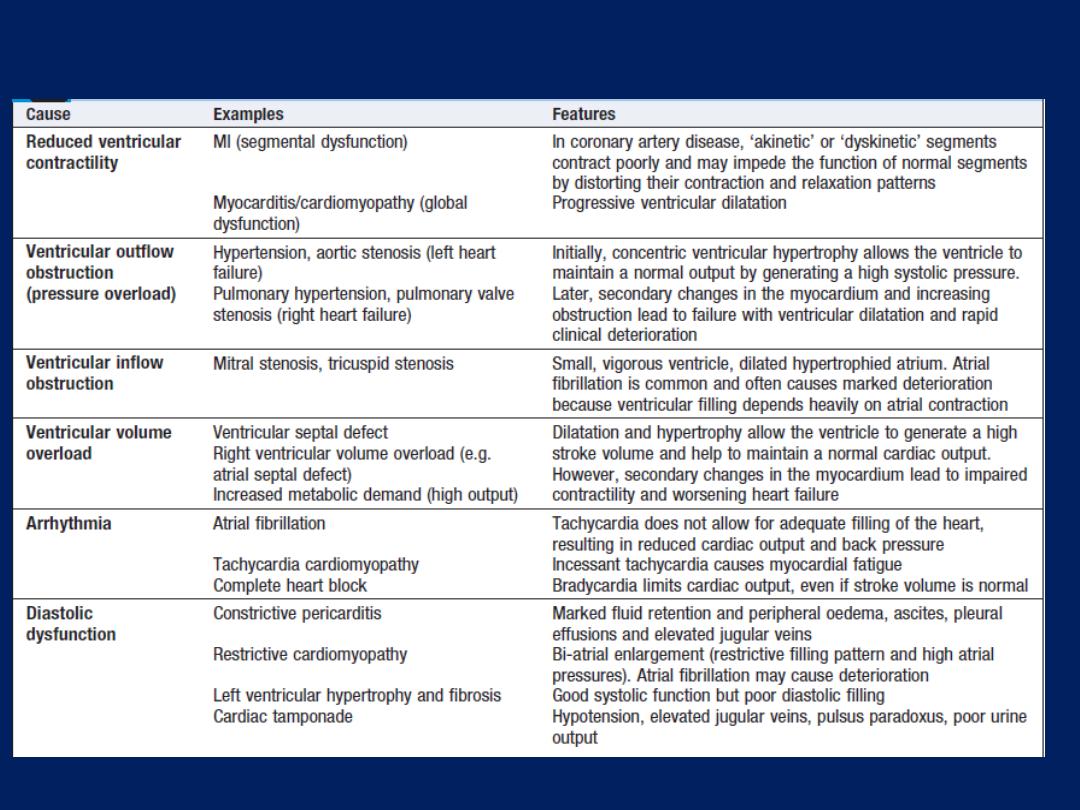

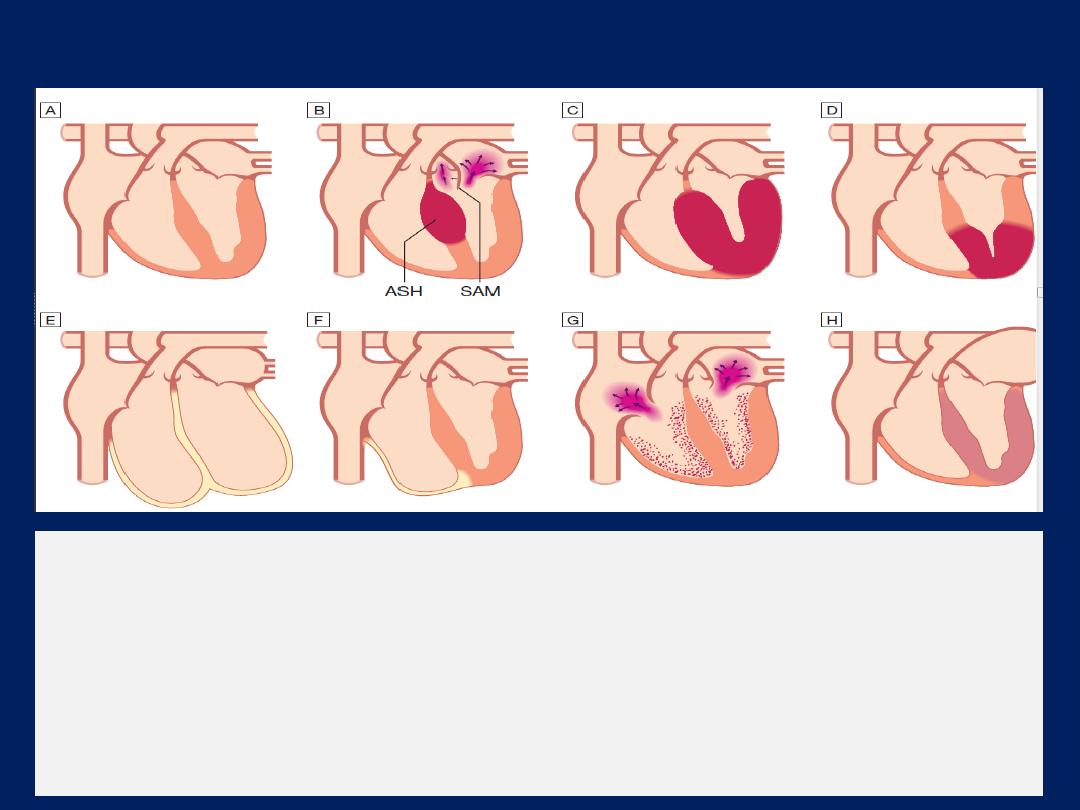

Mechanisms of heart failure

Mechanisms of heart failure

Cause

Reduced ventricular contractility

In coronary artery disease,

‘akinetic’ or ‘dyskinetic’ segments contract poorly and may impede the

function of normal segments by distorting their contraction and

relaxation patterns.

Myocarditis/cardiomyopathy

Global dysfunction and progressive ventricular dilatation.

Ventricular

outflow

obstruction (pressure overload)

a. Hypertension, aortic stenosis (left heart failure)

b. Pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary valve stenosis (right failure).

Initially, concentric ventricular hypertrophy allows the ventricle to

maintain a normal output by generating a high systolic pressure.

Later, secondary changes in the myocardium and increasing

obstruction lead to failure,ventricular dilatation and rapid deterioration

Mechanisms of heart failure – cont’d

Cause

Ventricular

inflow

obstruction

a. Mitral stenosis

b. tricuspid stenosis

Small, vigorous ventricle, dilated hypertrophied atrium. Atrial

fibrillation is common ,

often causes marked deterioration because ventricular filling

depends on atrial contraction.

Ventricular volume overload

a. Ventricular septal defect.

b. Right ventricular volume overload (e.g. atrial septal defect).

c.

Increased metabolic demand (high output).

Dilatation and hypertrophy allow the ventricle to generate a high

stroke volume and help to maintain a normal cardiac output.

However, secondary changes in the myocardium lead to impaired

contractility and worsening heart failure

Mechanisms of heart failure – cont’d

Cause

Arrhythmia

a. Atrial fibrillation :

Tachycardia does not allow for adequate filling

of the heart, resulting in reduced output and back pressure.

b. Tachycardia cardiomyopathy :

Incessant tachycardia causes

myocardial fatigue

c. Complete heart block :

Bradycardia limits cardiac output, even if

stroke volume is normal

Diastolic dysfunction

a. Constrictive pericarditis :

Marked fluid retention , peripheral

oedema, ascites, pleural effusions and elevated jugular veins

b. Restrictive cardiomyopathy :

Bi-atrial enlargement (restrictive

filling pattern and high atrial pressures). AF cause deterioration

c. Left ventricular hypertrophy and fibrosis,Cardiac tamponade :

Good systolic function but poor diastolic filling.Hypotension,

elevated jugular veins, pulsus paradoxus, poor urine output.

The most common aetiology is CAD and MI. Untreated

heart failure carries a poor prognosis; approximately

50% with severe failure due to left V- dysfunction will die

within 2 years, because of pump failure or malignant V-

arrhythmias.

Pathophysiology

Cardiac output is determined by preload (volume and

pressure of blood in the ventricles at the end of diastole),

afterload (volume and pressure of blood in the ventricles

during systole) and myocardial contractility; this is the

basis of

Starling’s Law.

The fall in cardiac output can occur because of impaired

systolic contraction, impaired diastolic relaxation, or both.

This activates counterregulatory neurohumoral mechanisms

that, in normal physiological circumstances, would support

cardiac function but, in the setting of impaired ventricular

function, can lead to a deleterious increase in both afterload

and preload . A vicious circle may be established because

any additional fall in cardiac output will cause further

neurohumoral activation and increasing peripheral vascular

resistance. Stimulation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone

system leads to vasoconstriction, sodium and water

retention, and sympathetic nervous system activation.

This is mediated by angiotensin II, a potent constrictor

of arterioles, in both the kidney and the systemic circulation.

Activation of the sympathetic nervous system may

initially sustain cardiac output through increased

myocardial contractility (inotropy) and heart rate

(chronotropy).

Prolonged sympathetic stimulation

also

causes

negative effects, including cardiac myocyte

apoptosis, hypertrophy and focal myocardial necrosis.

Sympathetic stimulation

also causes

peripheral

vasoconstriction

and

arrhythmias. Sodium and water

retention is promoted by the release of aldosterone,

endothelin-1

(a potent vasoconstrictor peptide with marked effects on the renal

vasculature)

and antidiuretic hormone (ADH).

Natriuretic

peptides

are released from the atria in response to atrial

stretch, and act as physiological antagonists to the fluid-

conserving effect of aldosterone.

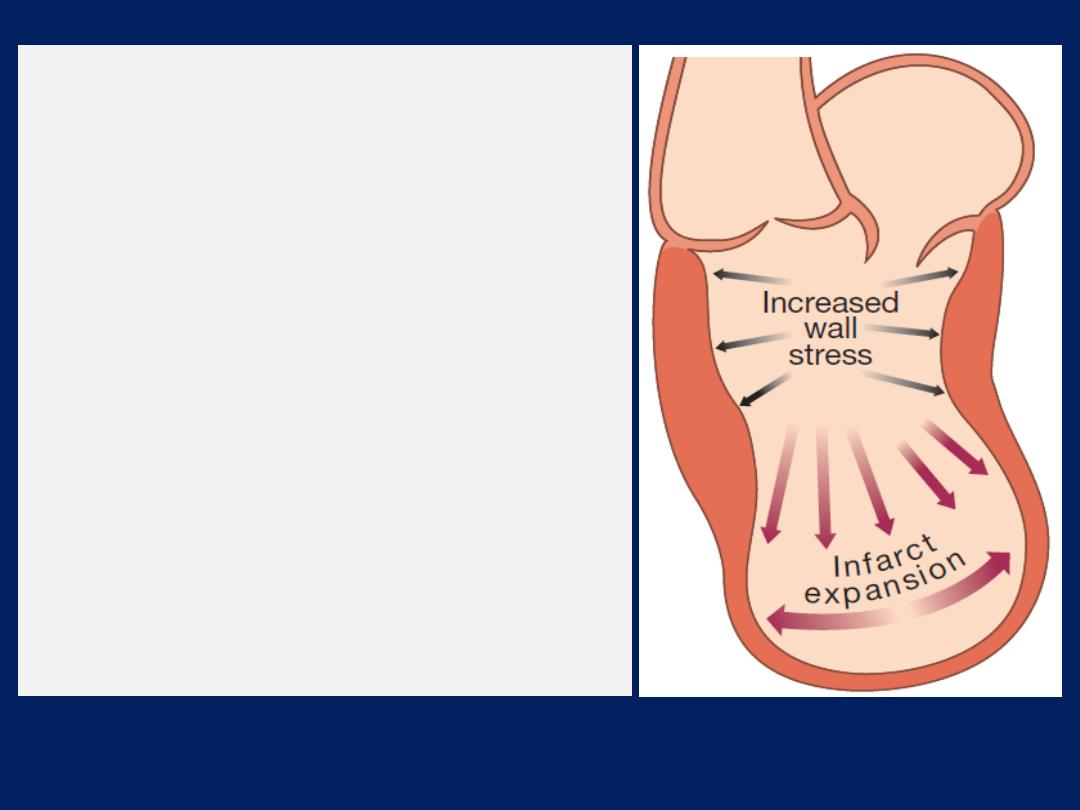

After MI,

cardiac contractility is impaired and neurohumoral

activation causes hypertrophy of non-infarcted segments,

with thinning, dilatation and expansion of the infarcted

segment

(remodelling).

This leads to further deterioration in ventricular function

and worsening heart failure.

Pulmonary and peripheral oedema occurs because of

high left and right atrial pressures, respectively; this

is compounded by sodium and water retention, caused

by impairment of renal perfusion and by secondary

hyperaldosteronism.

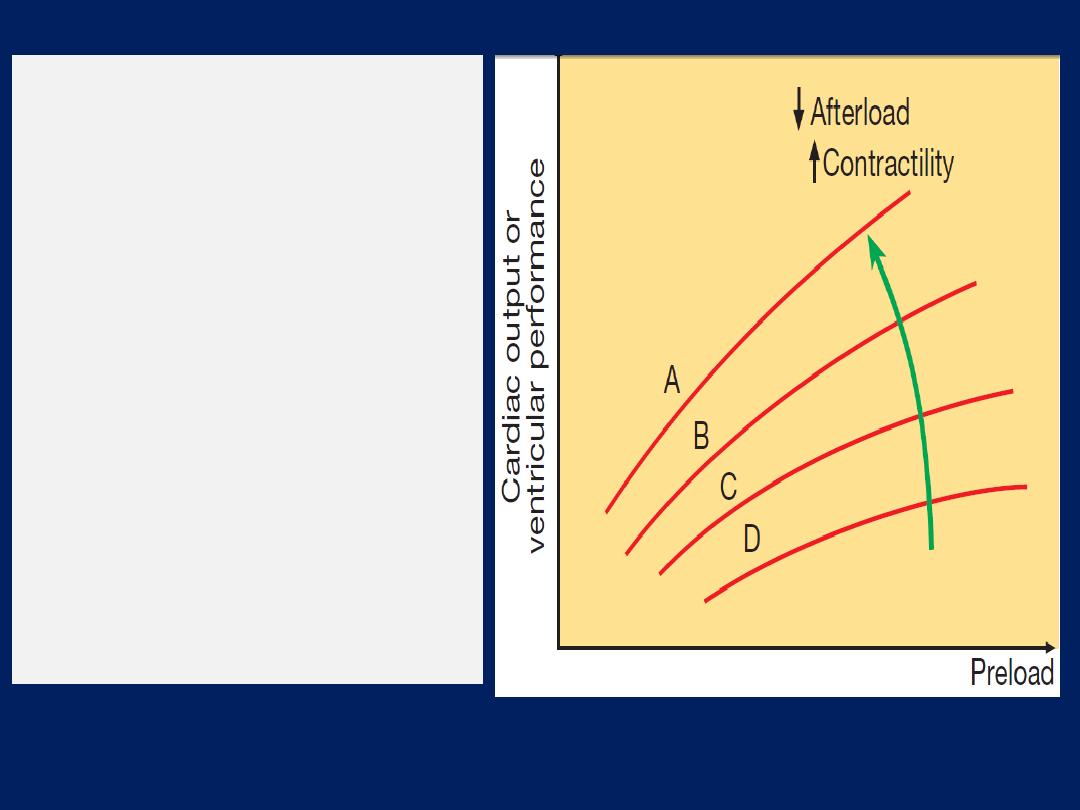

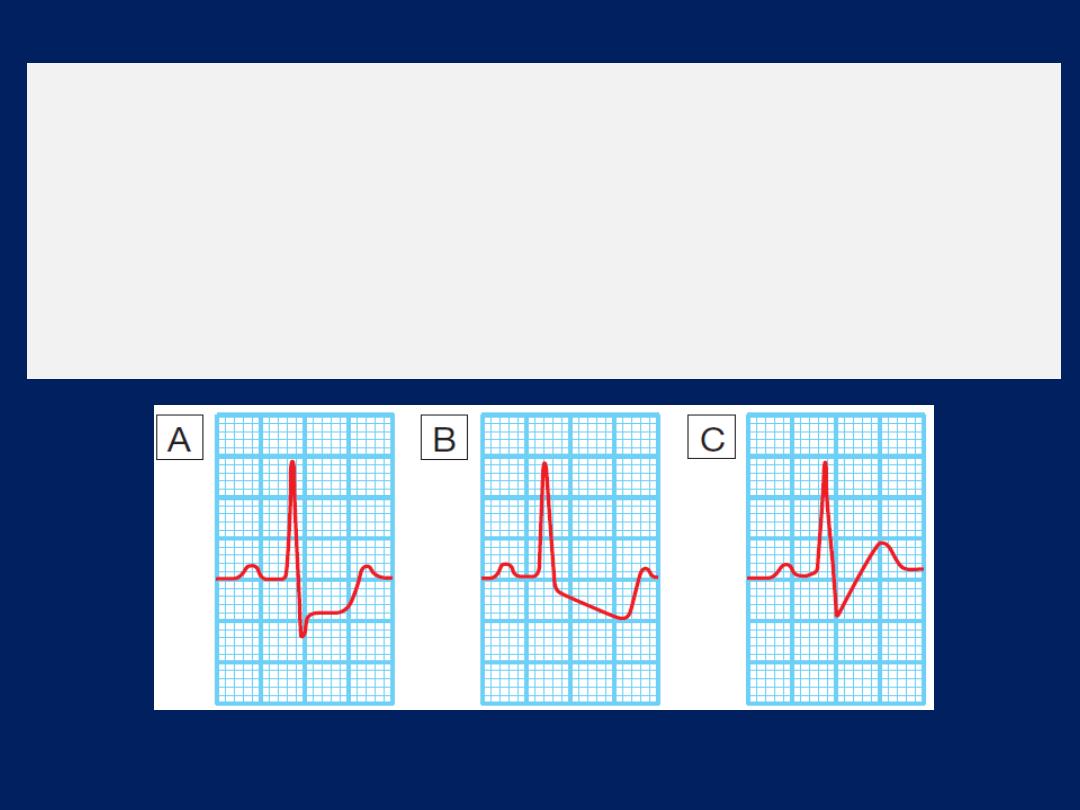

Starling’s Law

.

Normal (A), mild (B),

moderate (C) and severe (D) heart

failure. Ventricular performance is

related to the degree of

myocardial

stretching.

An increase in

preload (end-diastolic volume,

end-diastolic pressure, filling

pressure or atrial pressure) will

therefore enhance function; however,

overstretching

causes marked

deterioration.

In heart failure, the curve moves to

the right and becomes flatter.

An increase

in myocardial

contractility

or a reduction

in

afterload will shift the curve upwards

and to the left (

green arrow).

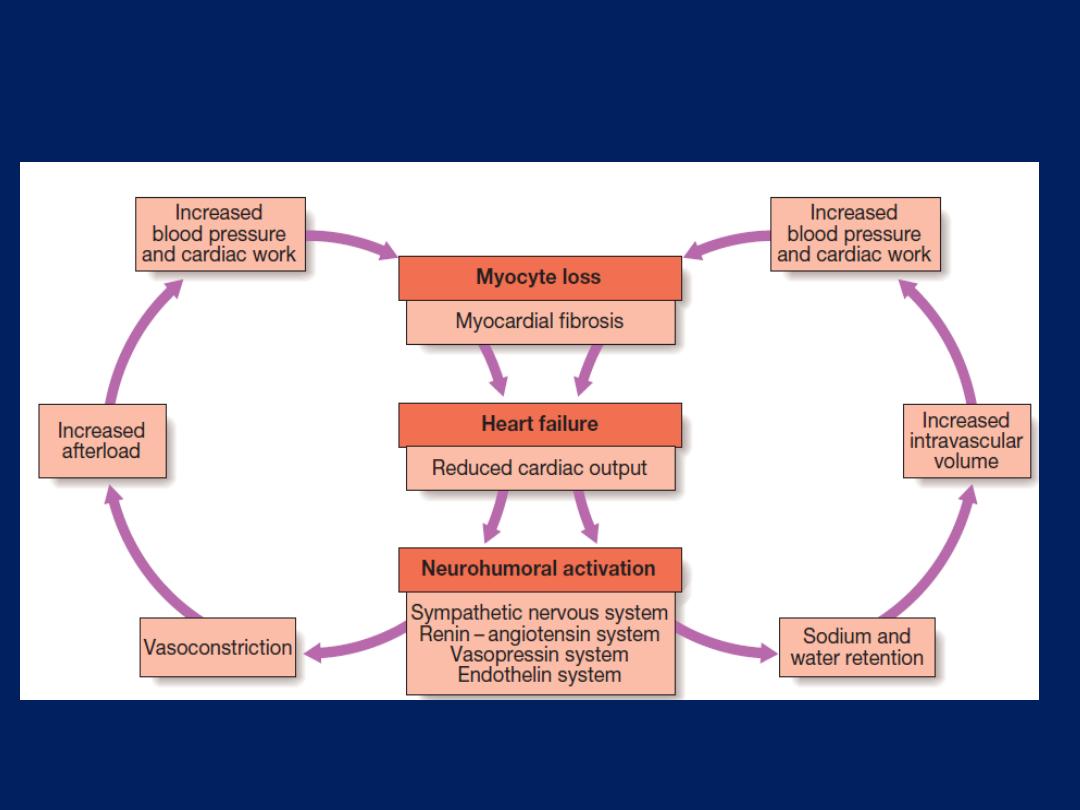

Neurohumoral activation and compensatory mechanisms in heart

failure. There is a vicious circle in progressive heart failure.

Types of heart failure

Left, right and biventricular heart failure

Left-sided heart failure.

There is a reduction in left

ventricular output

increase in left atrial and

pulmonary venous pressure. An acute increase in left

atrial pressure causes pulmonary congestion or

pulmonary oedema; a more gradual increase in left atrial

pressure, as occurs with mitral stenosis, leads to reflex

pulmonary vasoconstriction, which protects the patient

from pulmonary oedema. This increases pulmonary

vascular resistance and causes pulmonary hypertension,

which can, in turn, impair right ventricular function.

Right-sided heart failure.

There is a reduction in right

ventricular output

increase in right atrial

and systemic venous pressure.

Causes of

isolated

right heart failure include chronic lung

disease (cor pulmonale), pulmonary embolism and

pulmonary valvular stenosis.

Biventricular heart failure.

May develop because the

disease process, such as dilated cardiomyopathy or

ischaemic heart disease, affects both ventricles or

because disease of the left heart leads to chronic

elevation of the left atrial pressure, pulmonary

hypertension and right heart failure.

Diastolic and systolic dysfunction

Heart failure may develop as a result of impaired

myocardial contraction (systolic dysfunction) but can also

be due to poor ventricular filling and high filling pressures

stemming from abnormal ventricular relaxation (diastolic

dysfunction). The latter is caused by a stiff, noncompliant

ventricle and is commonly found in patients with left

ventricular hypertrophy.

Systolic and diastolic dysfunction often coexist, particularly

in patients with CAD .

High-output failure

A large arteriovenous shunt, beri-beri, severe anaemia or

thyrotoxicosis can occasionally cause heart

failure due to an excessively high cardiac output.

Acute and chronic heart failure

Heart failure may develop suddenly, as in MI, or gradually,

as in progressive valvular heart disease. The term

‘compensated heart failure’ is sometimes used to describe

the condition of those with impaired cardiac function, in

whom adaptive changes have prevented the development

of overt heart failure. A minor event, such as an

intercurrent infection or development of atrial fibrillation,

may precipitate overt or acute heart failure .Acute left

heart failure occurs, either de novo or as an acute

decompensated episode, on a background of chronic heart

failure: so-called acute-on- chronic heart failure.

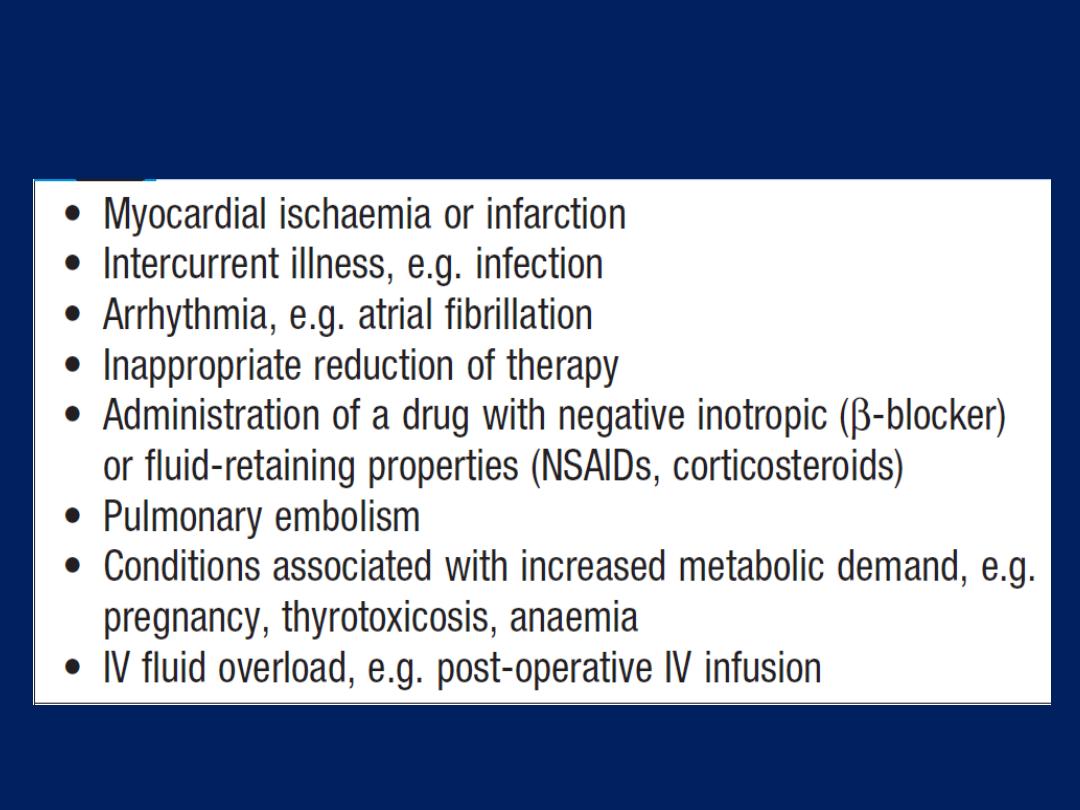

Factors that may precipitate or aggravate

heart failure in pre-existing heart disease

Clinical assessment

Acute left heart failure

Acute de novo left ventricular failure presents with

a sudden onset of dyspnoea at rest that rapidly

progresses to acute respiratory distress, orthopnoea and

prostration. The precipitant, such as acute MI, is often

apparent from the history. The patient appears agitated,

pale and clammy. The peripheries are cool to the touch and

the pulse is rapid. Inappropriate bradycardia or excessive

tachycardia should be identified promptly, as this may be

the precipitant for the acute episode of heart failure.

The BP is usually high because of sympathetic nervous

system activation, but may be normal or low if the patient is

in cardiogenic shock.

JVP is usually elevated, particularly with associated fluid

overload or right heart failure. In acute de novo heart

failure,

there has been no time for

ventricular dilatation

and the apex is not displaced. A ‘gallop’ rhythm, with a

third heart sound, is heard quite early in the development

of acute left sided heart failure.

A new systolic murmur

may signify

acute mitral regurgitation or ventricular septal

rupture. Auscultatory findings in pulmonary oedema are

crepitations at the lung bases, or throughout the lungs if

pulmonary oedema is severe. Expiratory wheeze often

accompanies this. Acute-on-chronic heart failure will have

additional features of long-standing heart failure ,

precipitants, respiratory tract infection or inappropriate

cessation of diuretic medication, should be identified.

Chronic heart failure

Commonly follow a relapsing and remitting course. Low

cardiac output causes fatigue, listlessness , poor effort

tolerance; the peripheries are cold and the BP is low. To

maintain perfusion of vital organs, blood flow is diverted

away from skeletal muscle and this may contribute to

fatigue and weakness. Poor renal perfusion leads to

oliguria and uraemia. Pulmonary oedema due to left heart

failure presents with inspiratory crepitations over the lung

bases. In contrast, right heart failure produces a high JVP

with hepatic congestion and dependent peripheral

oedema. In ambulant, the oedema affects the ankles,

whereas, in bed-bound patients, it collects around the

thighs and sacrum. Ascites or pleural effusion may occur .

Chronic heart failure is sometimes associated with

marked weight loss (cardiac cachexia), caused by

a combination of :

anorexia and impaired absorption due to

gastrointestinal congestion,

poor tissue perfusion due to a low cardiac output,

and skeletal muscle atrophy due to immobility.

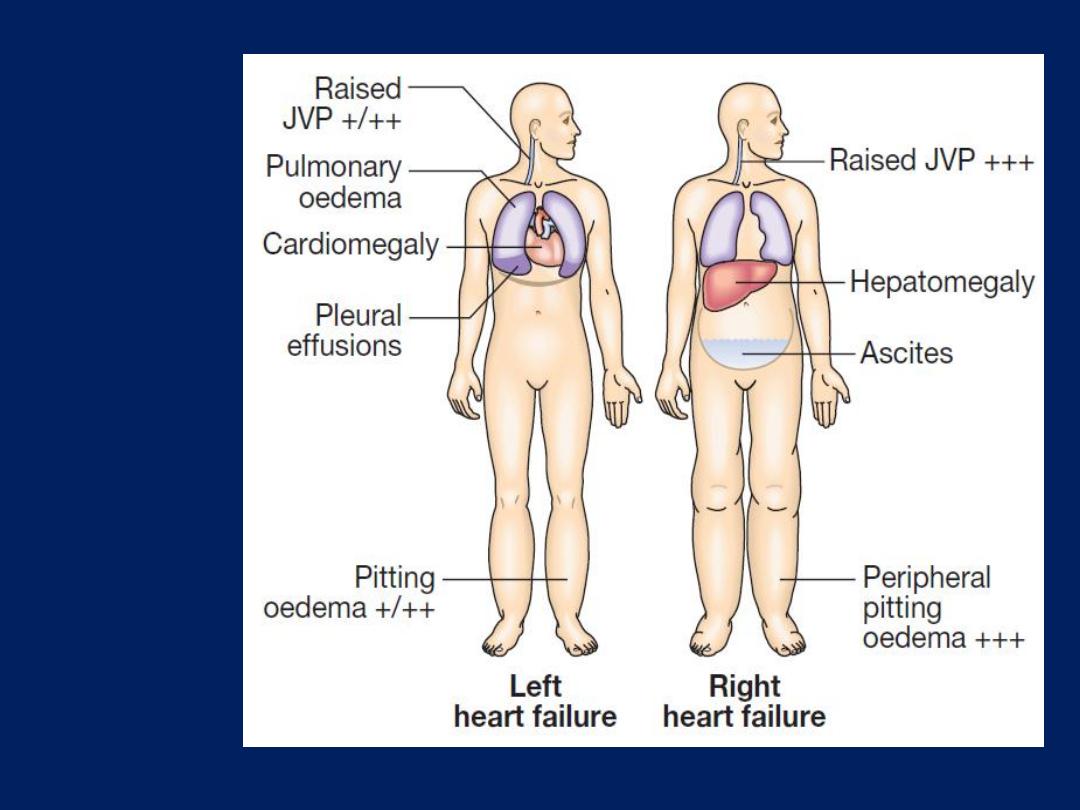

Clinical

features of

left and

right heart

failure.

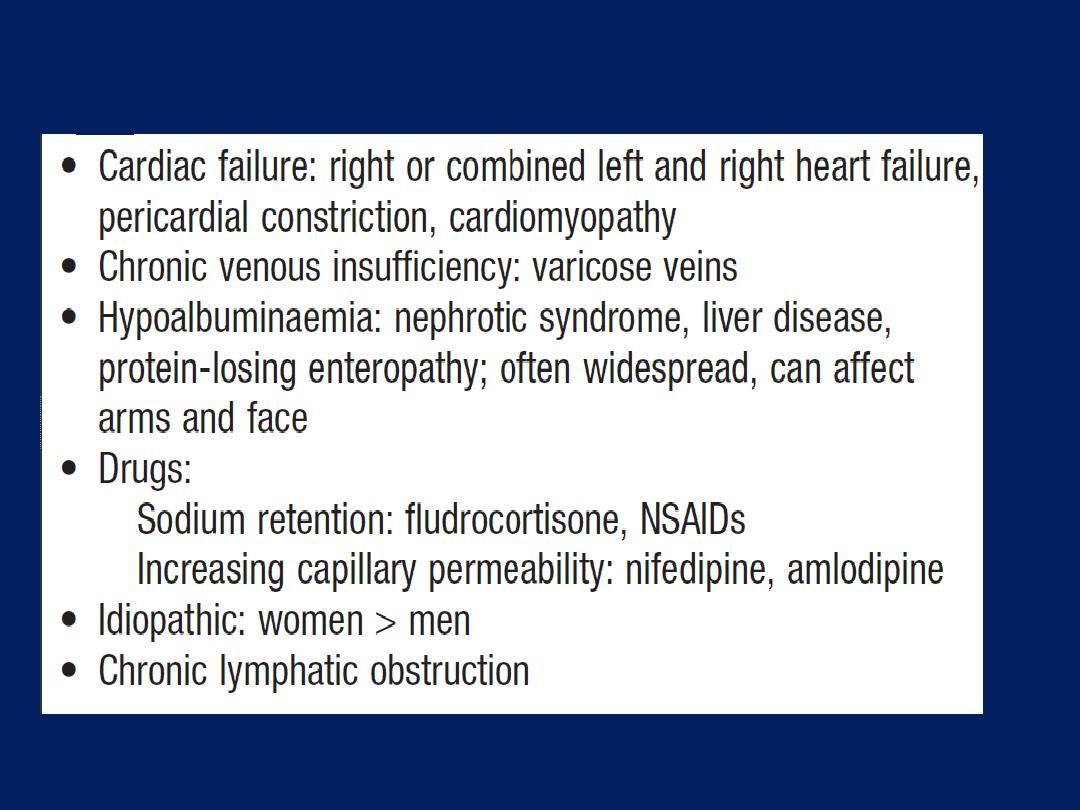

Differential diagnosis of peripheral oedema

Complications of heart failure

In advanced heart failure, the following may occur:

• Renal failure

is caused by poor renal perfusion due

to low cardiac output and may be exacerbated by

diuretic, ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers

• Hypokalaemia

may be the result of treatment with

potassium-losing diuretics or hyperaldosteronism caused by

activation of the renin–angiotensin system and impaired

aldosterone metabolism due to hepatic congestion.

• Hyperkalaemia

may be due to the effects of drugs

in particular the combination of ACE inhibitors or ARB

mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. These effects are

amplified if there is renal dysfunction.

• Hyponatraemia

is a feature of severe failure and is a

poor prognostic sign. It may be caused by diuretic,

inappropriate water retention due to high ADH secretion.

• Impaired liver function

is caused by hepatic venous

congestion, which frequently cause mild jaundice and

abnormal liver function tests; reduced synthesis of clotting

factors can make anticoagulant control difficult.

• Thromboembolism

.

VTE may occur due to the effects

of a low cardiac output and enforced immobility.

Systemic emboli occur in patients with atrial fibrillation or

flutter, or with intracardiac thrombus complicating conditions

such as mitral stenosis, MI or left ventricular aneurysm.

• Atrial and ventricular arrhythmias

are very common

and may be related to electrolyte changes (e.g.

hypokalaemia, hypomagnesaemia), the underlying

cardiac disease, and the pro-arrhythmic effects of

sympathetic activation. Atrial fibrillation occurs in

approximately 20% of patients with heart failure and

causes further impairment of cardiac function.

Sudden death occurs in up to 50% with heart failure and

is often due to a ventricular arrhythmia. Frequent

ventricular ectopic beats and runs of non-sustained

ventricular tachycardia are common findings and

are associated with an adverse prognosis.

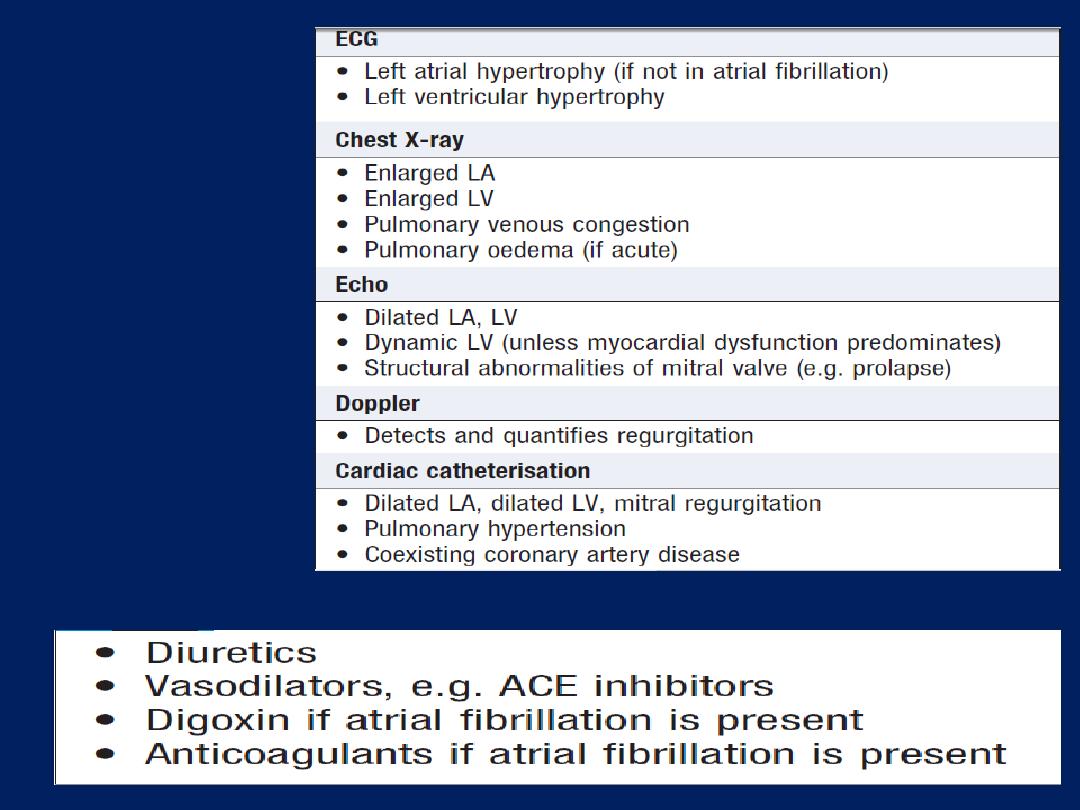

Investigations

Serum urea, creatinine and electrolytes, haemoglobin,

thyroid function, ECG and chest X-ray. Brain natriuretic

peptide (BNP) is elevated in heart failure and is a marker

of risk; it is useful in the investigation of patients with

breathlessness or peripheral oedema.

Echocardiography is very useful and should be considered

in all patients with heart failure in order to:

• determine the aetiology

• detect unsuspected valvular disease, such as mitral

stenosis

• identify patients who will benefit from long-term

drug therapy, e.g. ACE inhibitors .

Chest X-ray

High pulmonary venous pressure in left-sided heart

failure first shows on the chest X-ray . as an abnormal

distension of the upper lobe pulmonary veins

(with the patient in the erect position). The vascularity

of the lung fields becomes more prominent, and the

right and left pulmonary arteries dilate. Subsequently,

interstitial oedema causes thickened interlobular septa

and dilated lymphatics. These are evident as horizontal

lines in the costophrenic angles (

septal or ‘Kerley B’

lines). More advanced changes due to alveolar oedema

cause a hazy opacification spreading from the hilar

regions, and pleural effusions.

Radiological features

of heart failure.

A

Chest X-ray of

a patient with

pulmonary oedema.

B

Enlargement of lung

base showing septal or

‘Kerley B’ lines (arrow).

Management of acute pulmonary oedema

This is an acute medical emergency:

• Sit the patient up to reduce pulmonary congestion.

• Give oxygen (high-flow, high-concentration).

Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation

(continuous positive

airways pressure (CPAP) of 5–10 mmHg)

by a tight-fitting facemask

results in a more rapid clinical improvement.

• Administer nitrates, IV glyceryl trinitrate

(10–200 μg/min or

buccal glyceryl trinitrate 2–5 mg, titrated upwards every 10 minutes),

until clinical

improvement occurs or systolic BP falls to < 110 mmHg.

• Administer a loop diuretic, furosemide

(50–100 mg IV).

The patient should initially be kept rested, with continuous

monitoring of rhythm, BP and pulse oximetry.

• Intravenous opiates must be used sparingly in distressed

patients, as they may cause respiratory depression and

exacerbation of hypoxaemia and hypercapnia.

•

If these measures prove ineffective,

inotropic agents

may be required to augment cardiac output, particularly

in hypotensive patients. Insertion of an intra-aortic

balloon pump may be beneficial in patients with acute

cardiogenic pulmonary oedema and shock.

Management of chronic heart failure

1. General measures

Education of patients. Some may need to weigh themselves

daily, as a measure of fluid load, and adjust their diuretic.

Treat the underlying cause (e.g. CAD ) is important.

2. Drug therapy

Cardiac function can be improved by increasing

contractility, optimising preload or decreasing afterload.

Drugs that reduce preload are appropriate in patients with

high end-diastolic filling pressures and evidence of

pulmonary or systemic venous congestion.

Those that reduce afterload or increase myocardial

contractility are more useful in patients with signs and

symptoms of a low cardiac output.

Diuretic therapy

In heart failure, diuretics produce an increase in urinary

sodium and water excretion , reduces preload and

improves pulmonary and systemic venous congestion. It may

also reduce afterload, leading to a fall in ventricular wall

tension and increased cardiac efficiency.

Although a fall in preload tends to reduce cardiac output,

the ‘Starling curve’ in heart failure is flat, so there may be

a substantial and beneficial fall in filling pressure with little

change in cardiac output . Nevertheless, excessive diuretic

may cause an undesirable fall in cardiac output, especially

in patients with a marked diastolic component. This leads to

hypotension, lethargy and renal failure.

In some patients with severe chronic heart failure,

oedema may persist, despite oral loop diuretic therapy.

In such patients, an intravenous infusion of furosemide

(5–10 mg/ hr) may initiate a diuresis. Combining a loop

with a thiazide diuretic (e.g.

bendroflumethiazide 5 mg daily

) may

prove effective, but this can cause an excessive diuresis.

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists,

such as

spironolactone and eplerenone, are of particular benefit

in patients with heart failure with severe left ventricular

systolic dysfunction. They may cause hyperkalaemia,

particularly when used with an ACE inhibitor.

They

improve longterm clinical outcome in

patients with

severe heart failure or heart failure following acute MI.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition therapy

ACE inhibition therapy

interrupts the vicious circle of

neurohumoral activation that is characteristic of moderate

and severe heart failure by preventing the conversion of

angiotensin I to angiotensin II, thereby preventing peripheral

vasoconstriction, activation of the sympathetic nervous

system ,

and

salt and water retention due to aldosterone

release.

These drugs

also prevent

the undesirable activation of the

renin–angiotensin system caused by diuretic . In moderate

and severe heart failure, ACE inhibitors can produce a

substantial improvement in effort tolerance and in mortality.

Beta-adrenoceptor blocker therapy

Counteract the deleterious effects of enhanced

sympathetic stimulation and reduces arrhythmias and

sudden death. When initiated in standard doses, they may

precipitate acute-on-chronic heart failure, but when given

in small incremental doses (e.g. bisoprolol started at a

dose of 1.25 mg daily, and increased gradually over a

12-week period to a target maintenance dose of 10 mg

daily), they can increase ejection fraction, improve

symptoms, reduce hospitalisation and reduce mortality in

patients with chronic heart failure . Betablockers are

more

effective at

reducing mortality than ACE inhibitors

:

relative risk reduction of 33% versus 20%, respectively.

They can also improve outcome and prevent the onset of

overt heart failure in patients with poor residual left

ventricular function following MI.

ACE inhibitors can cause symptomatic hypotension

and impairment of renal function, especially in patients

with bilateral RAS or preexisting renal disease. An increase

in serum potassium concentration. Short-acting ACE

inhibitors can cause marked falls in BP, particularly in the

elderly or when started in the presence of hypotension,

hypovolaemia or hyponatraemia. In stable patients without

hypotension (systolic BP > 100 mmHg), ACE inhibitors can

usually be safely started.

However, in other patients, it is usually advisable to

withhold diuretics for 24 hours before starting treatment

with a small dose of a long-acting agent, preferably given

at night.

Renal function and serum potassium must be monitored and

should be checked 1–2 weeks after starting therapy.

Angiotensin receptor blocker therapy

Act by blocking the action of angiotensin II on the heart,

peripheral vasculature and kidney. They produce beneficial

haemodynamic changes that are similar to the effects of

ACE inhibitors but are generally better tolerated. They have

comparable effects on mortality and are a useful

alternative for patients who cannot tolerate ACE inhibitors.

ARBs are normally used as an alternative to ACE

inhibitors, but the two can be combined in patients with

resistant or recurrent heart failure.

Vasodilator therapy

These drugs are valuable in chronic heart failure,

when

ACE inhibitor or ARB drugs are contraindicated (e.g. in

severe renal failure). Venodilators, such as nitrates,

reduce preload, and arterial dilators, such as

hydralazine, reduce afterload .Their use is limited by

pharmacological tolerance and hypotension.

Ivabradine

Ivabradine inhibit the

I

f

inward current in the SA node,

resulting in reduction of heart rate.

It reduces hospital admission and mortality rates in

patients with heart failure due to moderate or severe left

ventricular systolic impairment.

In trials, its effects were most marked in patients with a

relatively high heart rate (over 77/min), so ivabradine is

best suited to patients who cannot take β-blockers or in

whom the heart rate remains high despite β-blockade.

It is ineffective in patients in atrial fibrillation.

Digoxin

Digoxin can be used to provide rate control in

patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation. In

patients with severe heart failure (NYHA class III–IV ) ,

digoxin reduces the likelihood of hospitalisation for heart

failure, although it has no effect on long-term survival.

Amiodarone

This is a potent anti-arrhythmic drug that has little negative

inotropic effect and may be valuable in patients with poor

left ventricular function.

It is only effective in the treatment of symptomatic

arrhythmias, and

should not

be used as a preventative

agent in asymptomatic patients.

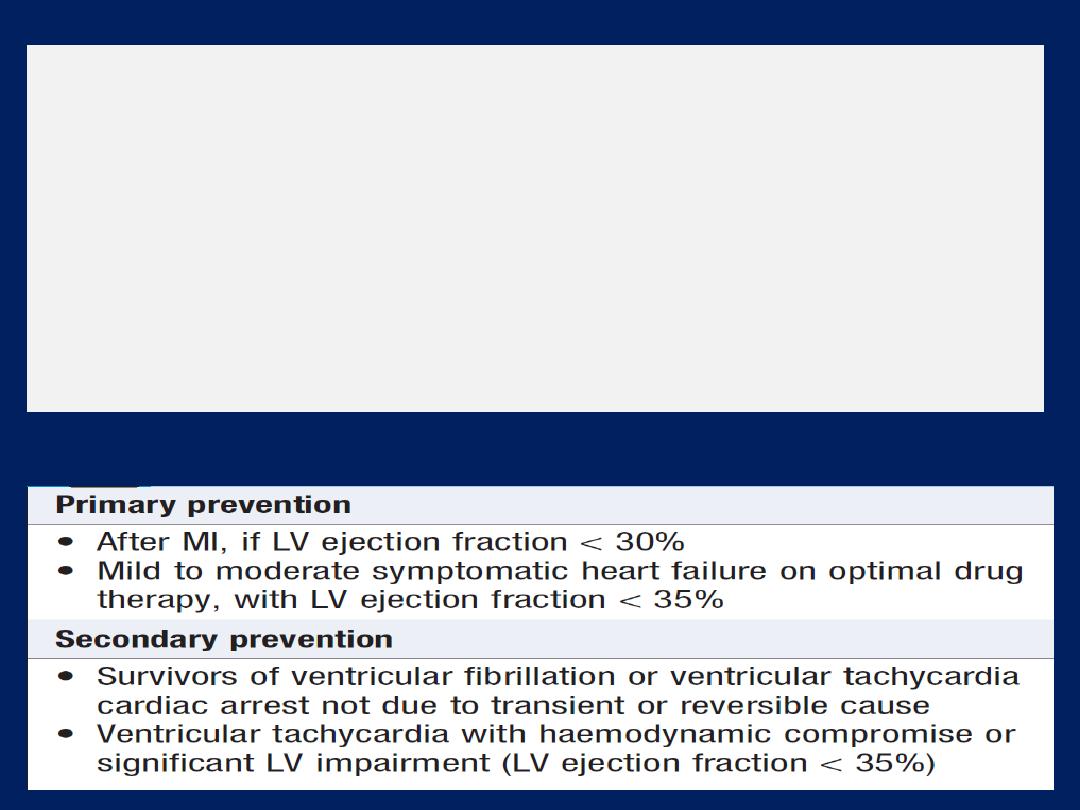

3. Implantable cardiac defibrillators

and

resynchronisation therapy

Patients with symptomatic ventricular arrhythmias and

heart failure have a very poor prognosis. Irrespective of

their response to anti-arrhythmic therapy, all should be

considered for implantation because it

improves survival .

In patients

with marked

intraventricular conduction delay,

prolonged depolarisation may lead to uncoordinated left

ventricular contraction. When this is associated with severe

symptomatic heart failure,

cardiac resynchronisation

should be considered. Here, both the LV and RV are paced

simultaneously to generate a more coordinated left

ventricular contraction and improve cardiac output. This is

associated with improved

symptoms and survival.

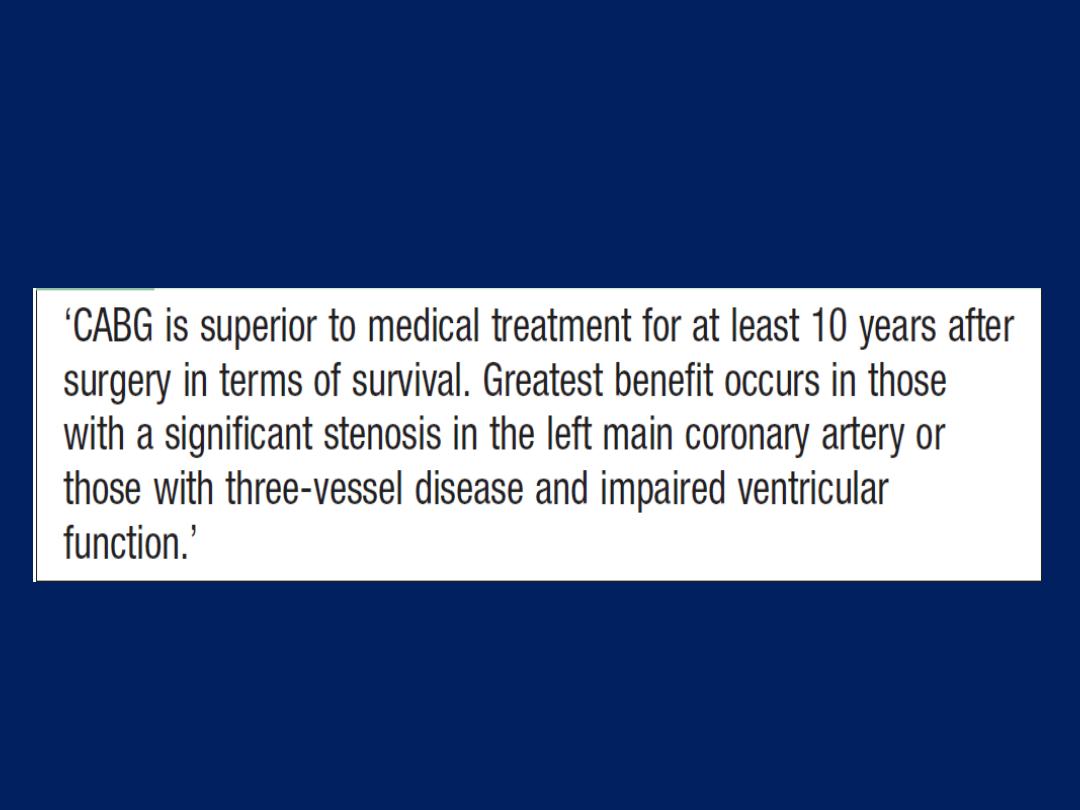

4. Coronary revascularisation

Coronary artery bypass surgery or percutaneous

coronary intervention may improve function in

areas of the myocardium that are ‘hibernating’

because of inadequate blood supply, and can be

used to treat carefully selected patients with heart

failure and coronary artery disease.

If necessary, ‘

hibernating

’ myocardium can be

identified by stress echocardiography and

specialized nuclear or MR imaging.

5. Heart transplantation

Cardiac transplantation is an established and successful

treatment for patients with

intractable

heart failure.

CAD and dilated cardiomyopathy are the most common

indications.

The introduction of ciclosporin for immunosuppression has

improved survival, which is around 80% at 1 year. The use

of transplantation is limited by the efficacy of modern

drug and device therapies, as well as the availability of

donor hearts, so it is generally reserved for young patients

with severe symptoms despite optimal therapy.

Conventional heart transplantation is contraindicated

in patients with pulmonary vascular disease due

to long-standing left heart failure, complex congenital

heart disease (e.g. Eisenmenger’s syndrome) or primary

pulmonary hypertension because the RV of the donor

heart may fail in the face of high pulmonary vascular

resistance.

However,

heart–lung transplantation can be

successful in patients with Eisenmenger’s syndrome.

Lung transplantation has been used for primary

pulmonary hypertension.

Although

cardiac transplantation usually produces a

dramatic improvement in the recipient’s quality of life,

serious complications may occur:

Complications

• Rejection

. In spite of routine therapy with ciclosporin A,

azathioprine and corticosteroids, episodes of rejection are

common and may present with heart failure, arrhythmias;

cardiac biopsy is often used to confirm the diagnosis before

starting treatment with high-dose corticosteroids.

• Accelerated atherosclerosis

.

Recurrent heart failure is

often due to progressive atherosclerosis in the coronary

arteries of the donor heart.

Angina is rare because

the

heart has been denervated.

• Infection.

Opportunistic infection with organisms such as

cytomegalovirus or Aspergillus remains a major cause of

death in transplant recipients.

6. Ventricular assist devices (VADs)

• as a bridge to cardiac transplantation

• potential long-term therapy

• short-term restoration therapy following a potentially

reversible insult, e.g. viral myocarditis.VADs assist cardiac

output by using pulsatile pump that, in some cases, is

implantable and portable. They withdraw blood through

cannulae inserted in the atria or apex and pump it into the

pulmonary artery or aorta. They unload the ventricles and

to provide support to the pulmonary and systemic

circulations. Their application is limited by high

complication rates (haemorrhage, systemic embolism,

infection, neurological and renal sequelae), although some

improvements in survival and quality of life have been

demonstrated in patients with severe heart failure.

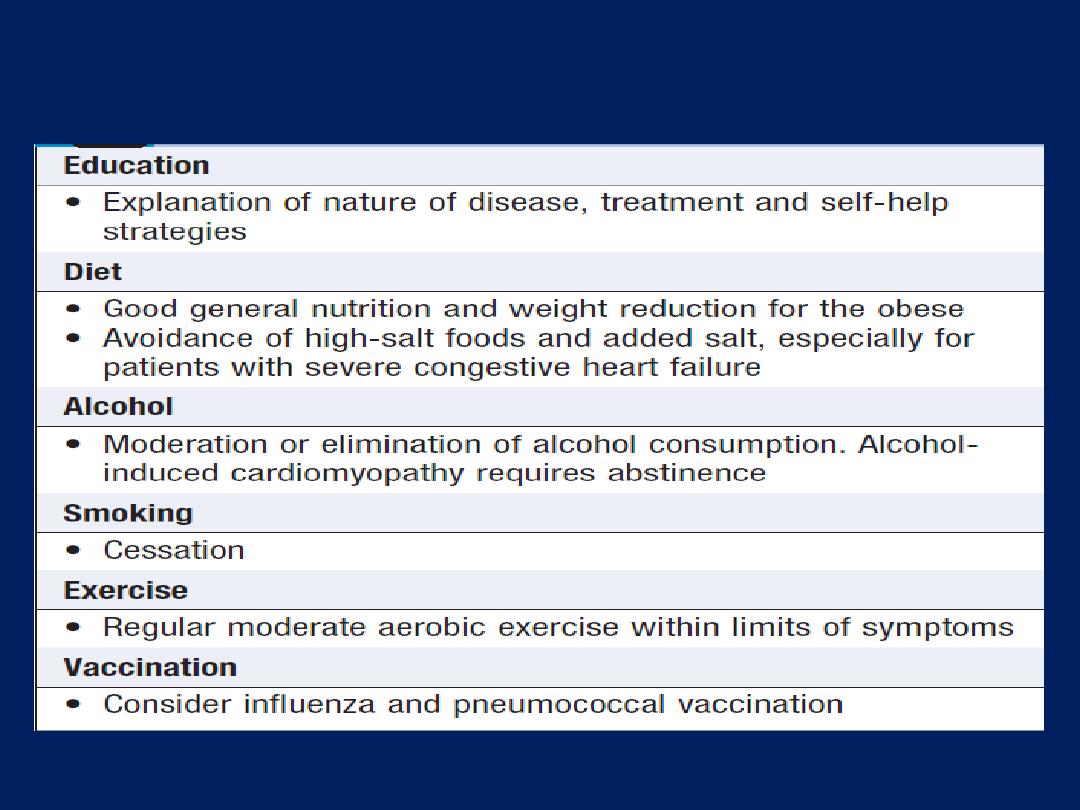

General measures for the management of heart failure

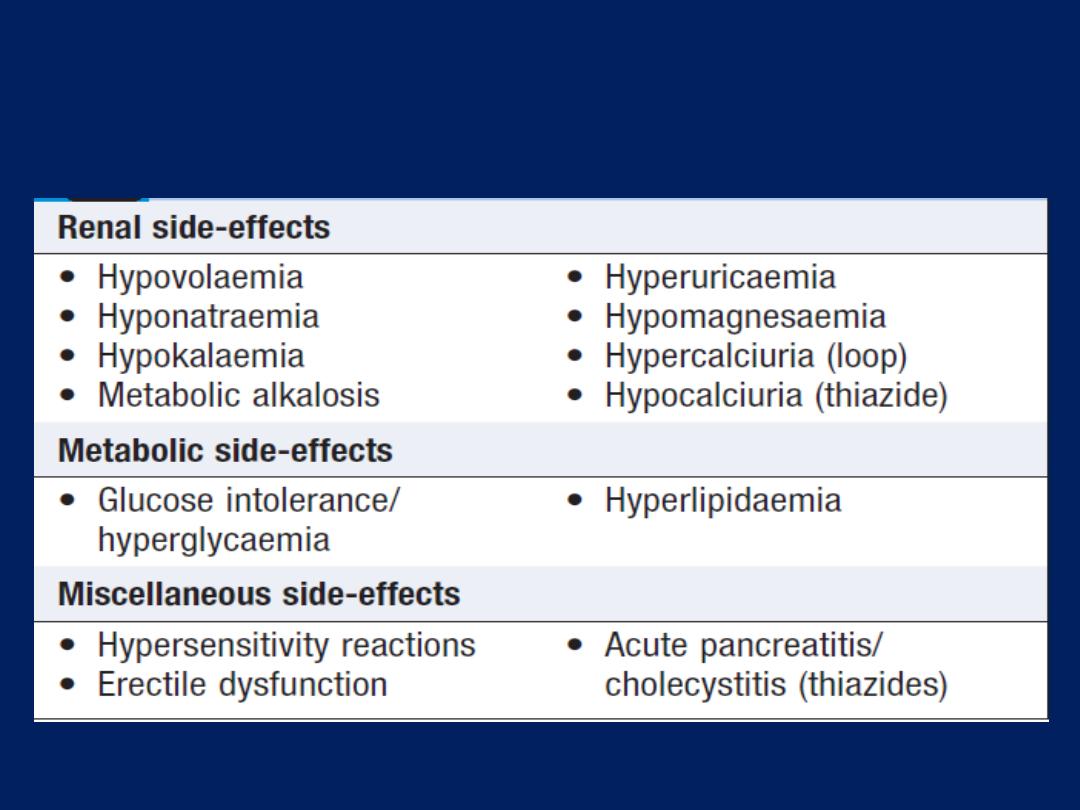

Adverse effects of loop-acting and thiazide

diuretics

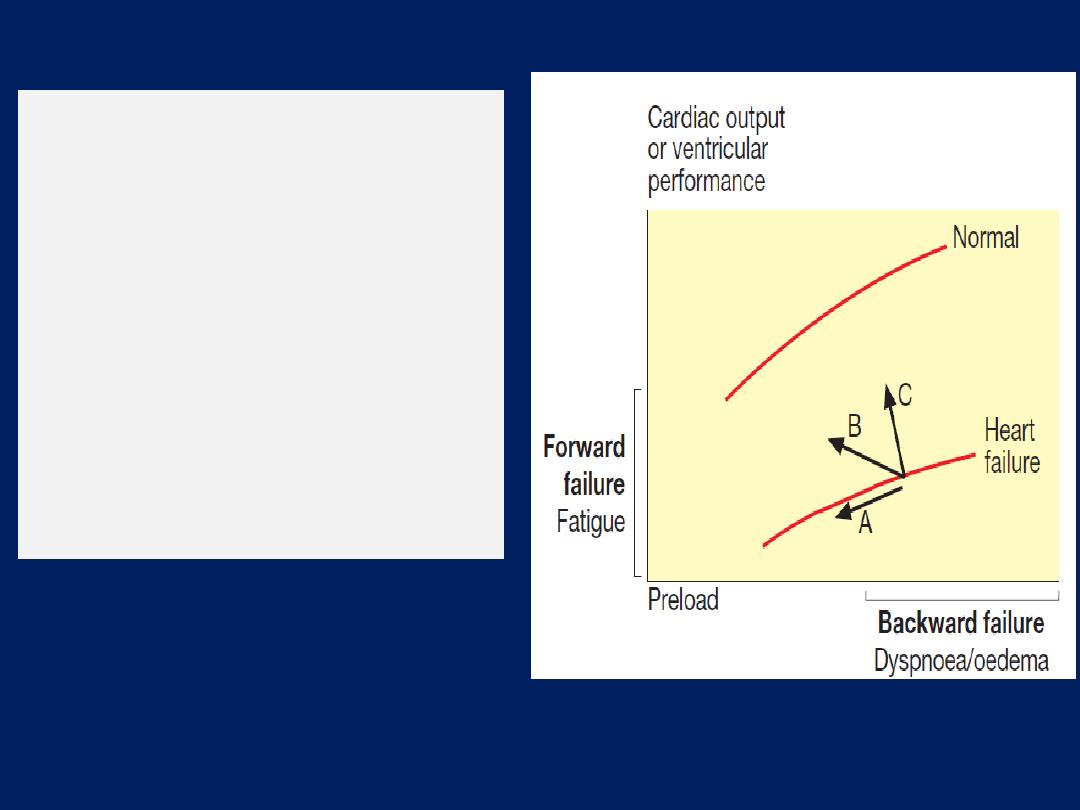

The effect of treatment on

ventricular performance

curves in heart failure.

(A)

Diuretics and

venodilators

(B)

Angiotensin converting

enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

and mixed vasodilators

(C)

Positive inotropic agents

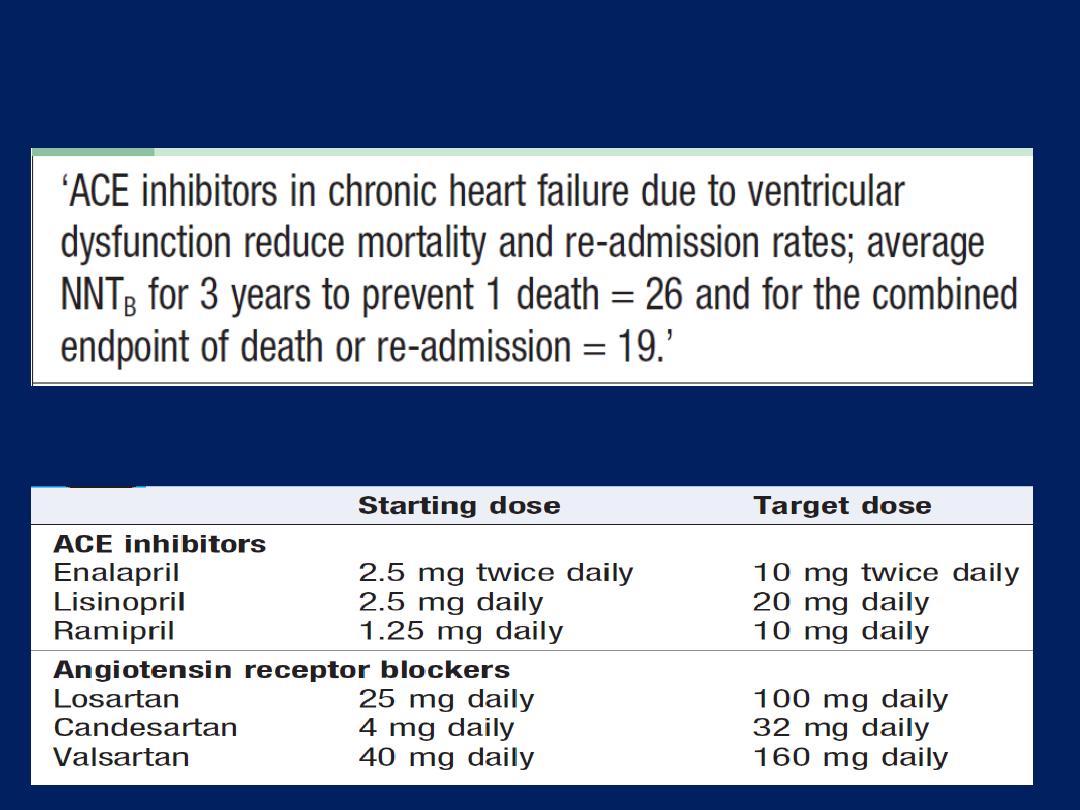

ACE inhibitors and treatment of chronic heart failure

ACE inhibitor and ARB dosages in heart failure

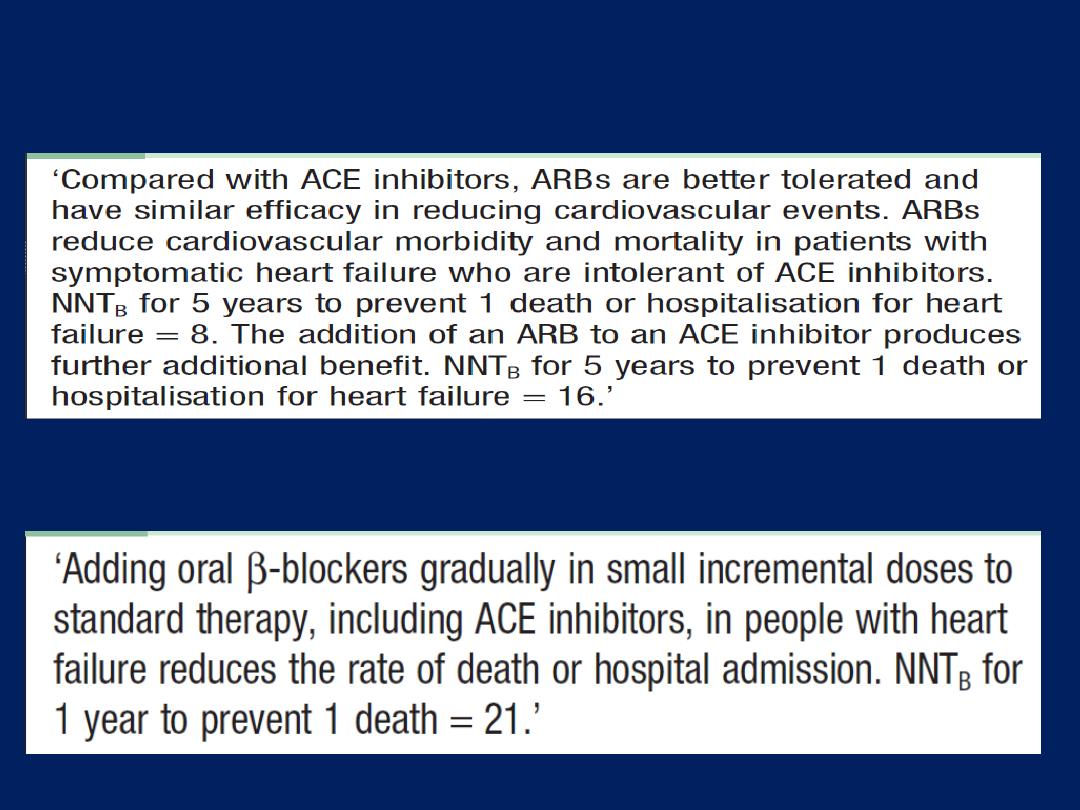

Angiotensin receptor blockers and chronic heart failure

Beta-blockers and treatment of chronic heart failure

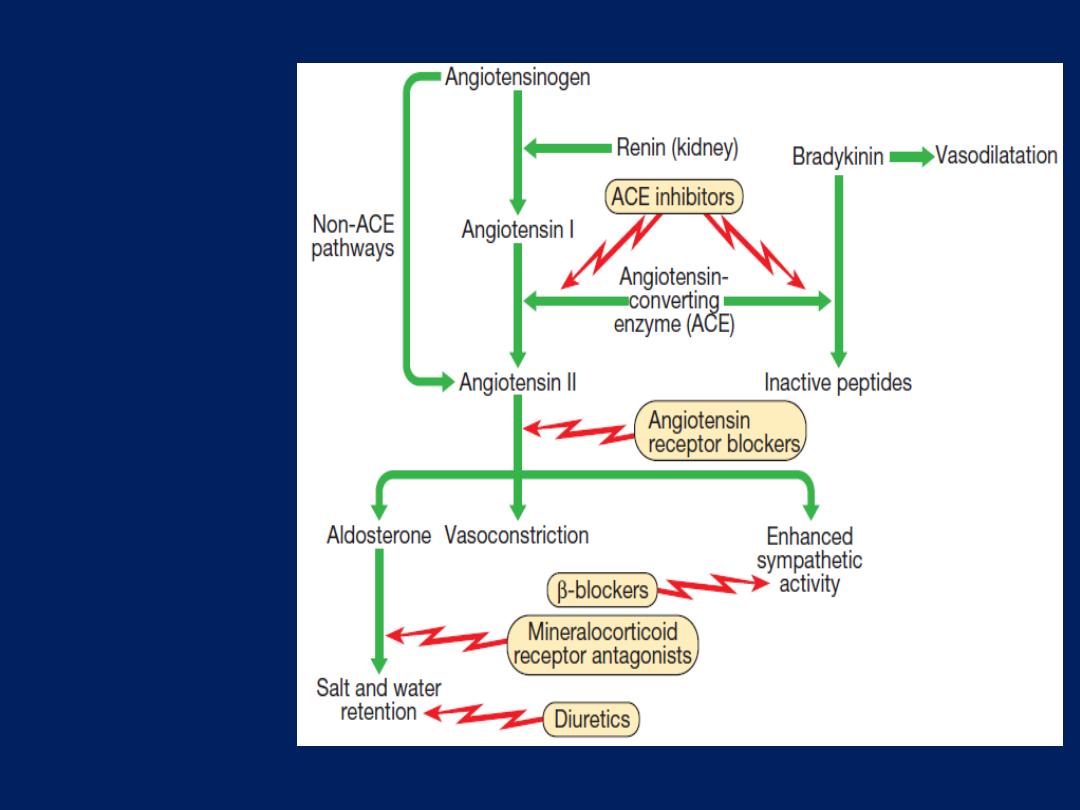

Neurohumor

al activation

and sites of

action of

drugs used

in

the treatment

of heart

failure.

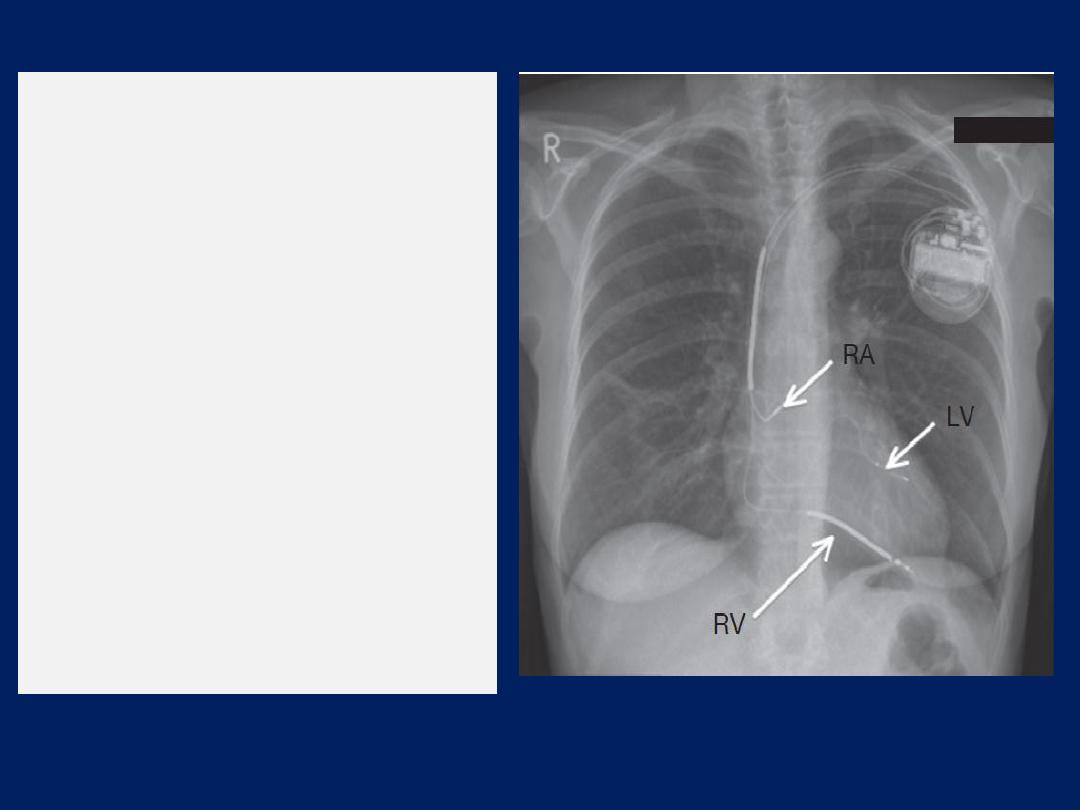

Chest X-ray of a biventricular

pacemaker and defibrillator

(cardiac resynchronisation

therapy).

The right ventricular lead (RV)

is in position in the ventricular

apex and is

used for

pacing

and defibrillation.

The left ventricular lead (LV) is

placed via the coronary sinus,

and the right atrial lead (RA) is

placed in the right atrial

appendage;

both are used

for

pacing only.

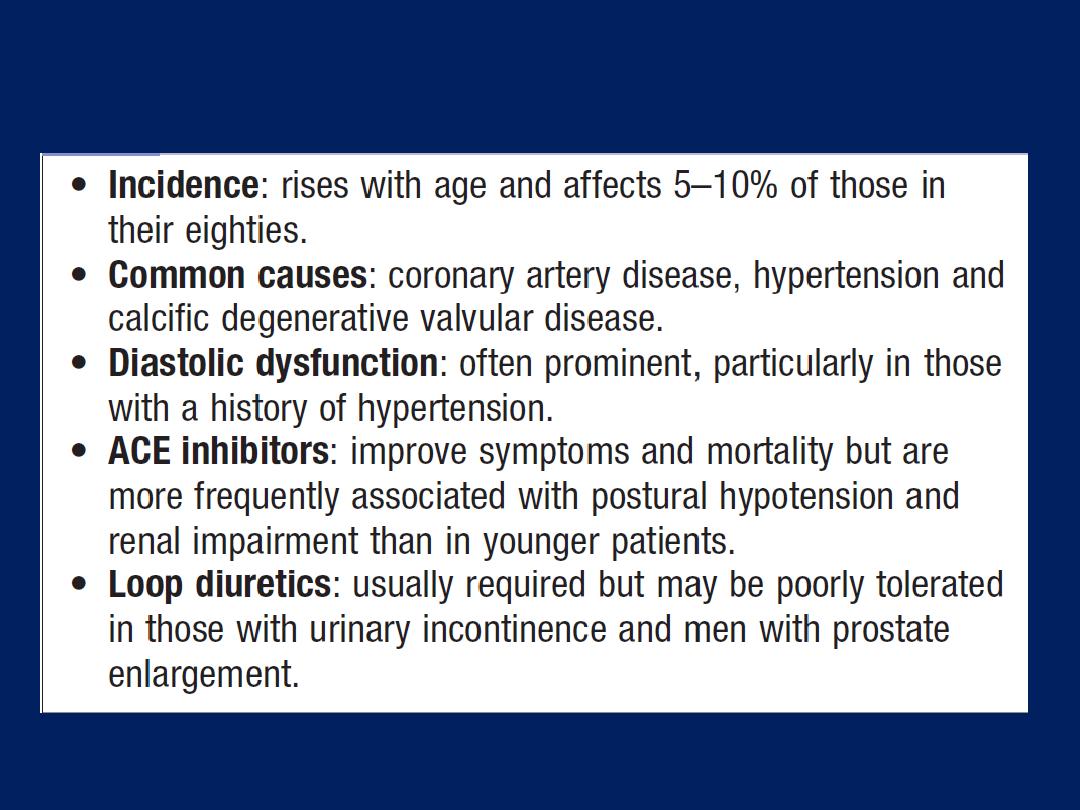

Congestive cardiac failure in old age

Syncope and presyncope

The term ‘syncope’ refers to sudden loss of consciousness

due to reduced cerebral perfusion.

Presyncope

refers to lightheadedness in which the individual thinks

he or she may black out. Syncope affects around 20% of

the population at some time and accounts for more than

5% of hospital admissions. Dizziness and presyncope are

very common in old age . Symptoms are disabling,

undermine confidence and independence, and can affect

an individual’s ability to work or to drive.

There are three principal mechanisms that underlie

recurrent presyncope or syncope:

• cardiac syncope

due to mechanical cardiac dysfunction

or arrhythmia

• neurocardiogenic syncope,

abnormal autonomic reflex

causes bradycardia and/or hypotension

• postural hypotension,

in which physiological

peripheral vasoconstriction on standing is impaired,

lead to hypotension.

Loss of consciousness can also be caused by non-cardiac

pathology, such as

epilepsy, cerebrovascular ischaemia or hypoglycaemia .

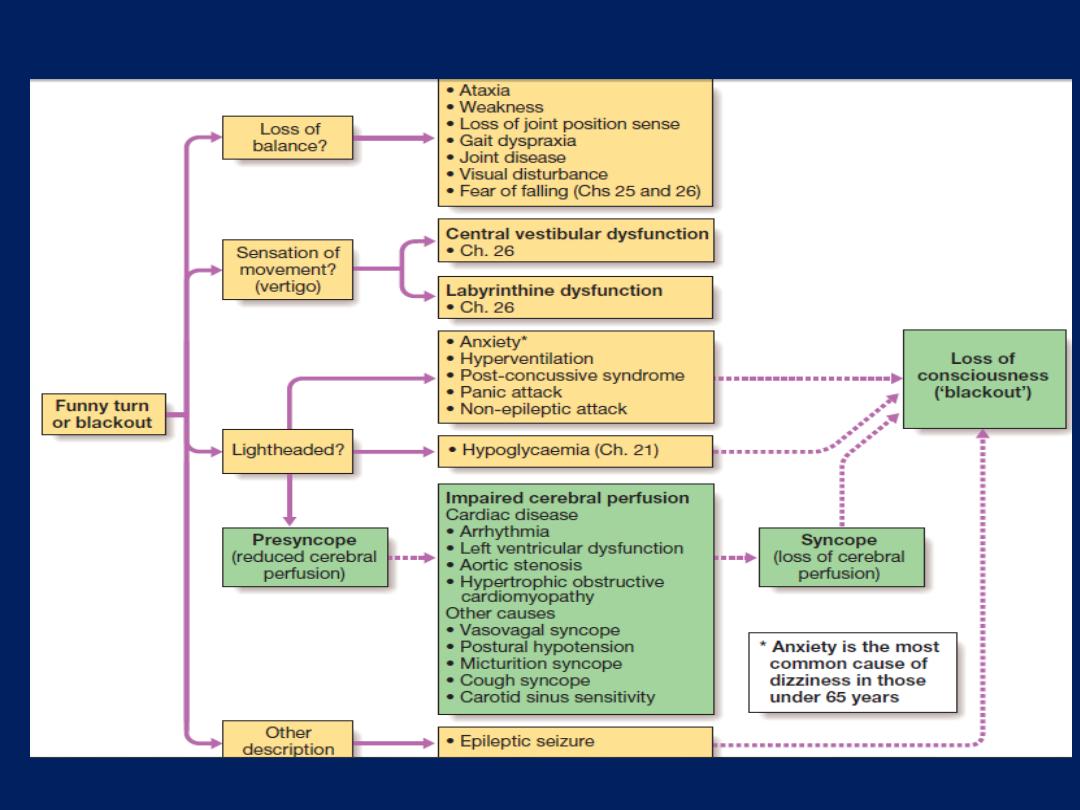

The differential diagnosis of syncope and presyncope.

Differential diagnosis

History-taking, from the patient or a witness, is the key

to establishing a diagnosis. Attention should be paid to

potential triggers (e.g. medication, exertion, posture), the

victim’s appearance (e.g. colour, seizure activity), the

duration of the episode and the speed of recovery .

Cardiac syncope is usually sudden but can be

associated with premonitory lightheadedness, palpitation

or chest discomfort. The blackout is usually brief and

recovery rapid.

Neurocardiogenic syncope will often be associated with

a situational trigger, and the patient may experience

flushing, nausea and malaise for several minutes

afterwards.

Patients with seizures do not exhibit pallor, may have

abnormal movements, usually take more than 5 minutes

to recover and are often confused. A history of rotational

vertigo is suggestive of a labyrinthine or vestibular

disorder .The pattern and description of the patient’s

symptoms should indicate the probable mechanism and

help to determine subsequent investigations.

Postural hypotension is normally obvious from the

history, with presyncope or, less commonly, syncope,

occurring within a few seconds of standing.

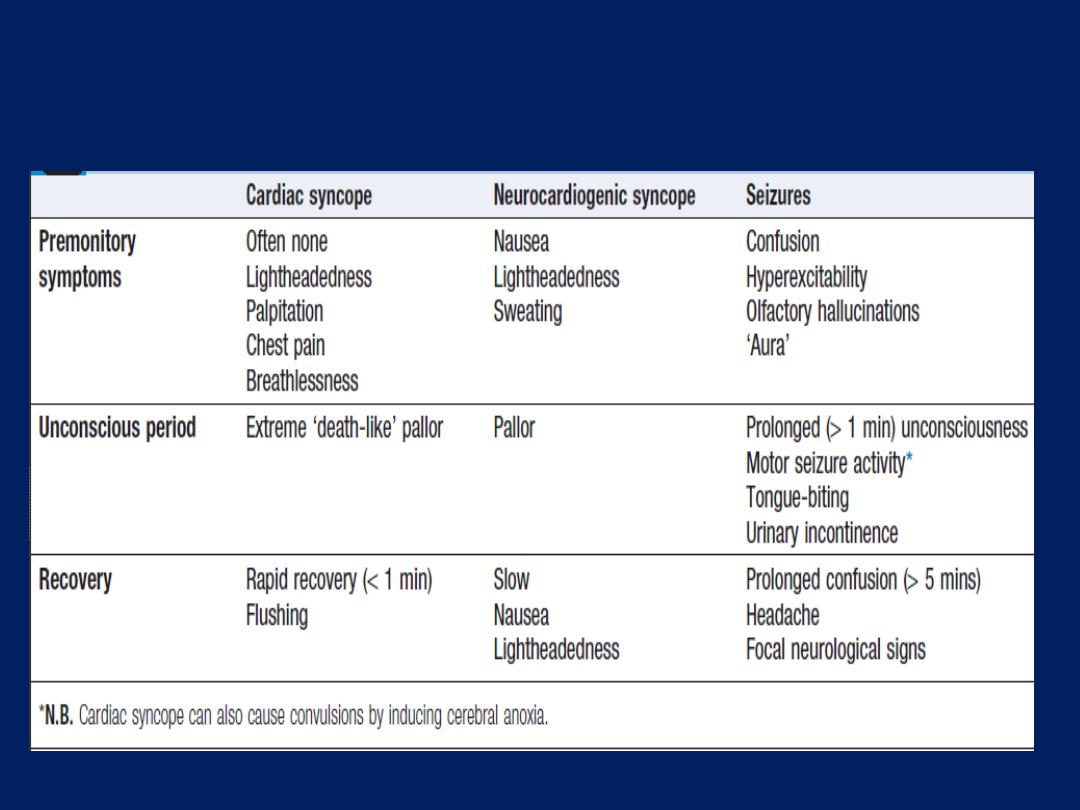

Typical features of cardiac syncope, vasovagal

syncope and seizures

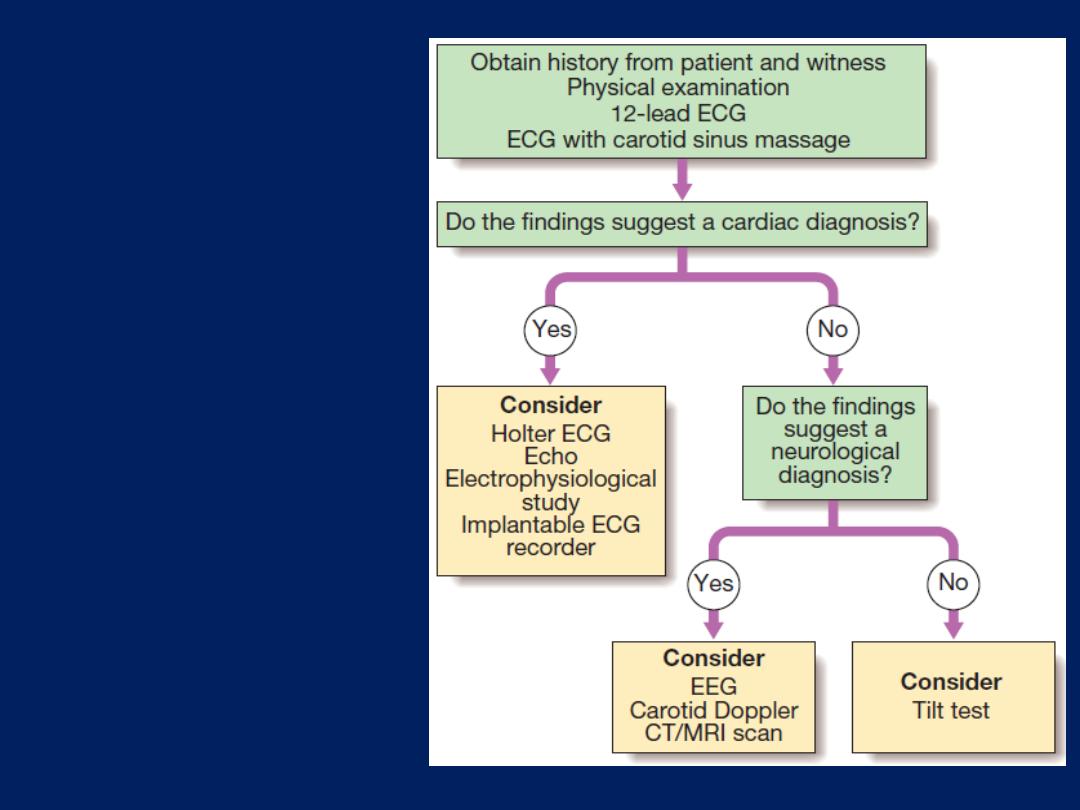

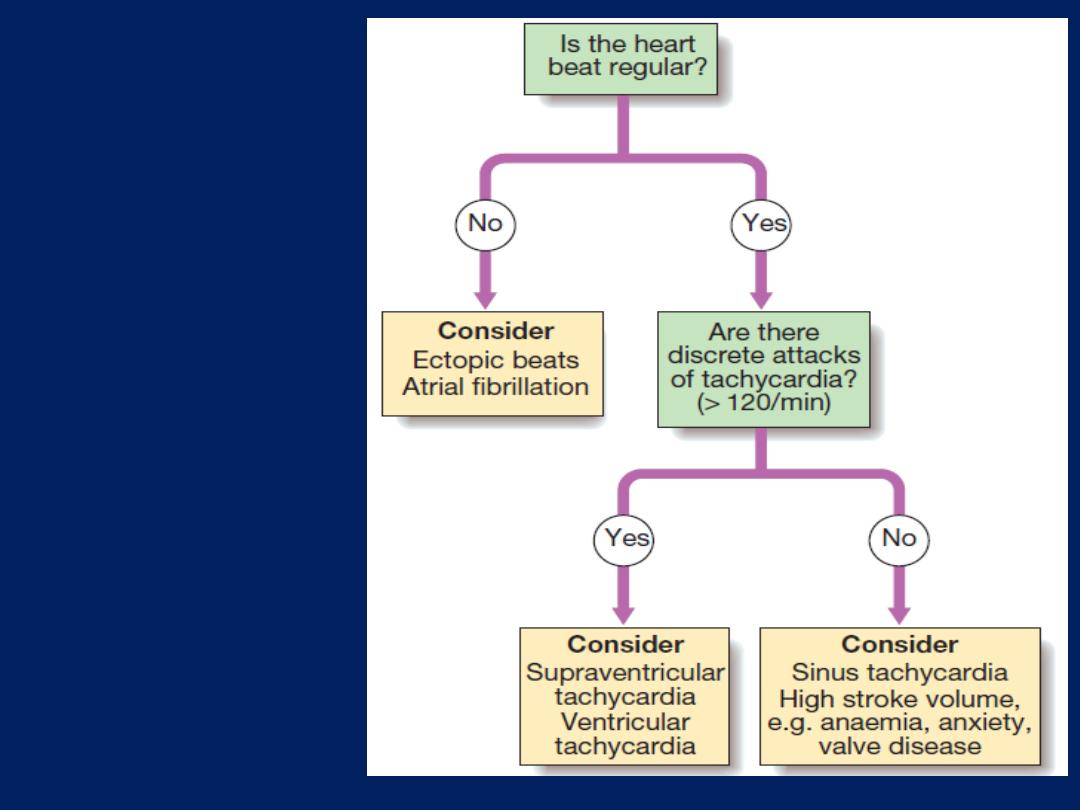

A simple guide to