1

D. Rasha Pathology L4

GRANULOMATOUS DISEASES

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease of unknown cause characterized by noncaseating

granulomas in many tissues and organs. Sarcoidosis presents many clinical patterns, but

bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy or lung involvement is visible on chest radiographs in

90% of cases. Eye and skin lesions are next in frequency .Since other diseases, including

mycobacterial or fungal infections and berylliosis, can also produce noncaseating (hard)

granulomas, the histologic diagnosis of sarcoidosis is made by exclusion.

Etiology and Pathogenesis.

Although the etiology of sarcoidosis remains unknown, several

lines of evidence suggest that it is a disease of disordered immune regulation in

genetically predisposed individuals exposed to certain environmental agents.”

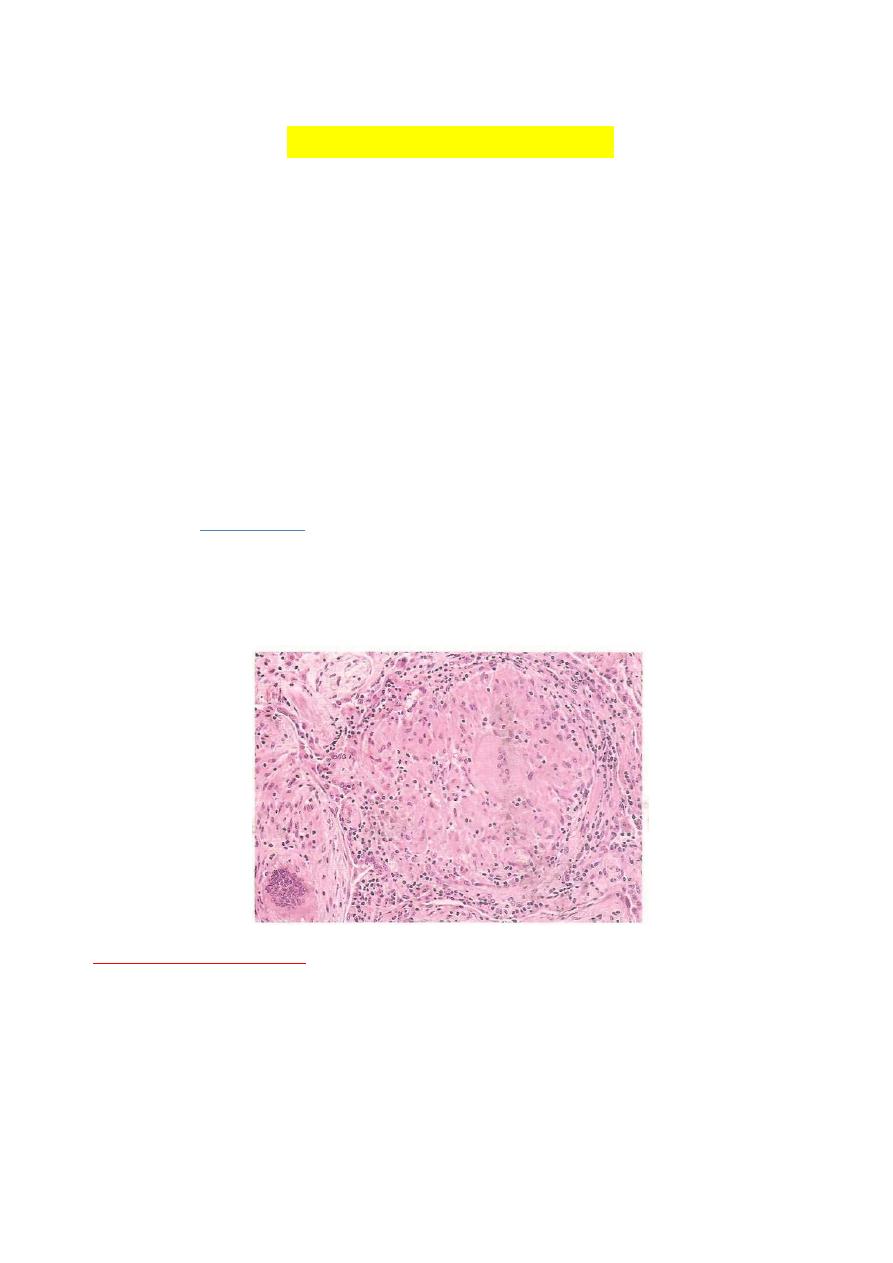

Morphology.

Histologically,

all involved tissues show the classic noncaseating granulomas,

each composed of an aggregate of tightly clustered epithelioid cells, often with Langhans

or foreign body type giant cells. Central necrosis is unusual. With chronicity, the

granulomas may become enclosed within fibrous rims or may eventually be replaced by

hyaline fibrous scars.

PULMONARY INFECTIONS:

Respiratory tract infections are more frequent than infection of any other organ. The

vast majority are upper respiratory tract infections caused by viruses (common cold,

pharyngitis) but bacterial, viral, mycoplasmal, fungal infections of the lung (pneumonia)

still account enormous amount of morbidity and are responsible sixth of all deaths in the

United States. Pneumonia very broadly defined as any infection of the lung parenchyma

(although the same term is used for many interstitial lung diseases that are not infectious

in origin, such as interstitial pneumonia).

2

Pulmonary defense mechanisms:

pneumonia result when these defense mechanisms are

impaired or whenever the resistance of the host in general is lowered.

Factors that affect general resistance include

chronic diseases, immunologic deficiency

diseases and treatment with immunosuppressive agents.

The clearing mechanisms can be interfered with by many factors, such as the following:

Loss or suppression of the cough reflex, as a result of coma, anesthesia,

neuromuscular disorders, drugs, or chest pain.

Injury to the mucociliary apparatus, by either impairment of ciliary function or

destruction of ciliated epithelium, due to cigarette smoke, inhalation of hot or

corrosive material, viral diseases, or genetic disturbances.

Interference with the phagocytic or bactericidal action of alveolar macrophages by

alcohol, tobacco smoke.

Accumulation of secretions in conditions such as cystic fibrosis and bronchial

obstruction.

COMMUNITY-ACQUIRED ACUTE PNEUMONIAS

Community-acquired pneumonias may be bacterial or viral. Often, the bacterial infection

follows an upper respiratory tract viral infection. Bacterial invasion of the lung

parenchyma causes the alveoli to be filled with an inflammatory exudate, thus causing

consolidation (“solidification”) of the pulmonary tissue. Many variables, such as the

specific etiologic agent, the host reaction, and the extent of involvement, determine the

precise form of pneumonia. Predisposing conditions include extremes of age, chronic

diseases (congestive heart failure, COPD, and diabetes), congenital or acquired immune

deficiencies, and decreased or absent splenic function (sickle cell disease or post

splenectomy, which puts the patient at risk for infection with encapsulated bacteria such

as pneumococcus). First we describe pneumonias caused by various organisms and then

the morphologic and clinical features common to most pneumonias.

Streptococcus Pneumonia:

Streptococcus pneumonia, is the most common cause of community-acquired acute

pneumonia. Examination of Gram-stained sputum is an important step in the diagnosis of

acute pneumonia. The presence of numerous neutrophils containing the typical Gram-

positive diplococci supports the diagnosis of pneumococcal pneumonia.

Haemophilus Influenzae

Huemophilus influenzae is a pleomorphic, Gram-negative organism that is a major cause

of life-threatening acute lower respiratory tract infections and meningitis in young

children. In adults, it is a very common cause of community-acquired acute pneumonia.

3

Staphylococcus Aureus

Staphylococcus aureus is an important cause of secondary bacterial pneumonia in

children and healthy adults. Staphylococcal pneumonia is associated with a high incidence

of complications such as lung abscess and empyema.

Legionella pneumophila:

This transmitted by contaminated drinking water. Legionella pneumonia is common in

individuals with some predisposing condition such as ‘cardiac, renal, immunologic, or

hematologic disease. Transplant recipients are particularly susceptible.

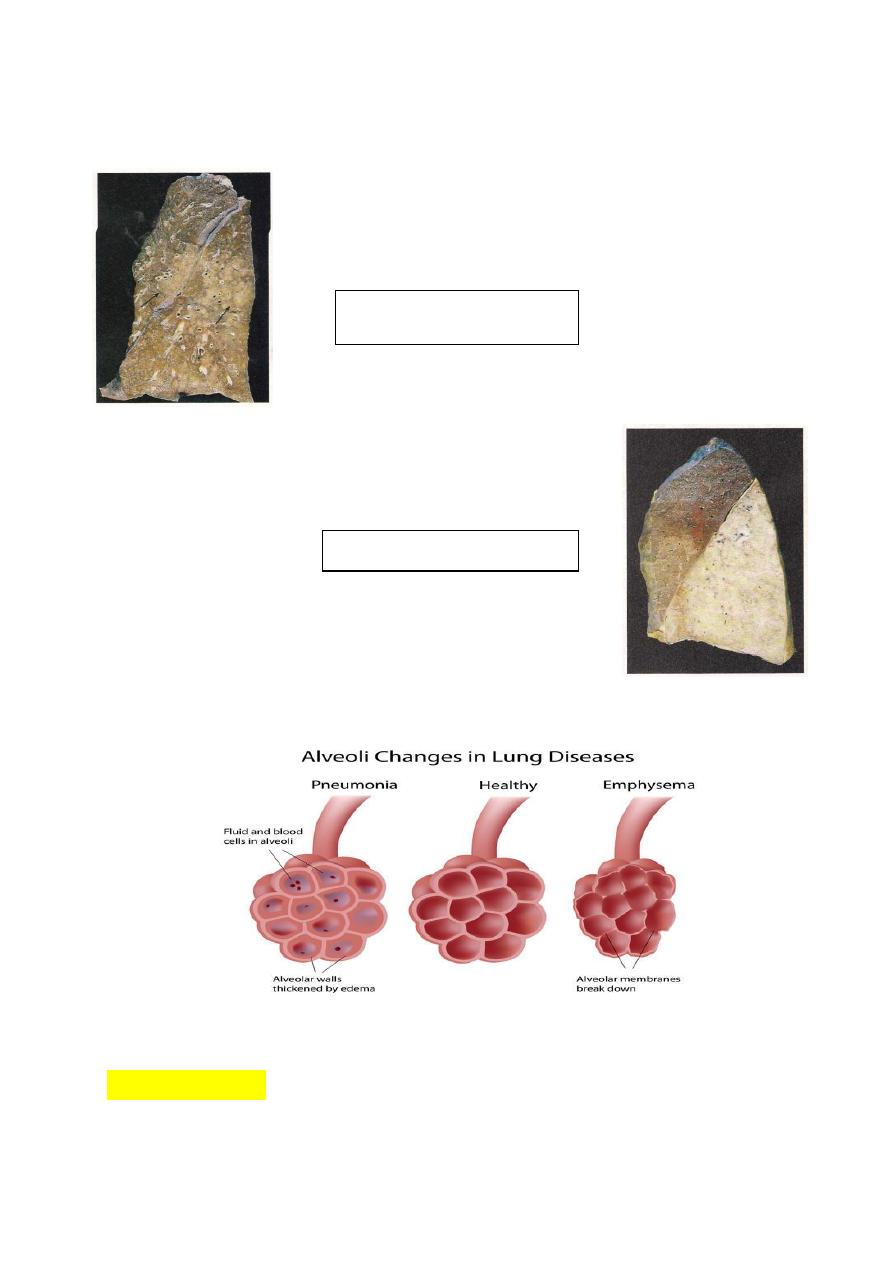

Morphology.

Bacterial pneumonia has two

gross

patterns of anatomic distribution: lobular

bronchopneumonia and lobar pneumonia. Patchy consolidation of the lung is the

dominant characteristic of bronchopneumonia. Lobar pneumonia is an acute bacterial

infection resulting in fibrinosuppurative consolidation of a large portion of lung or of an

entire lobe.

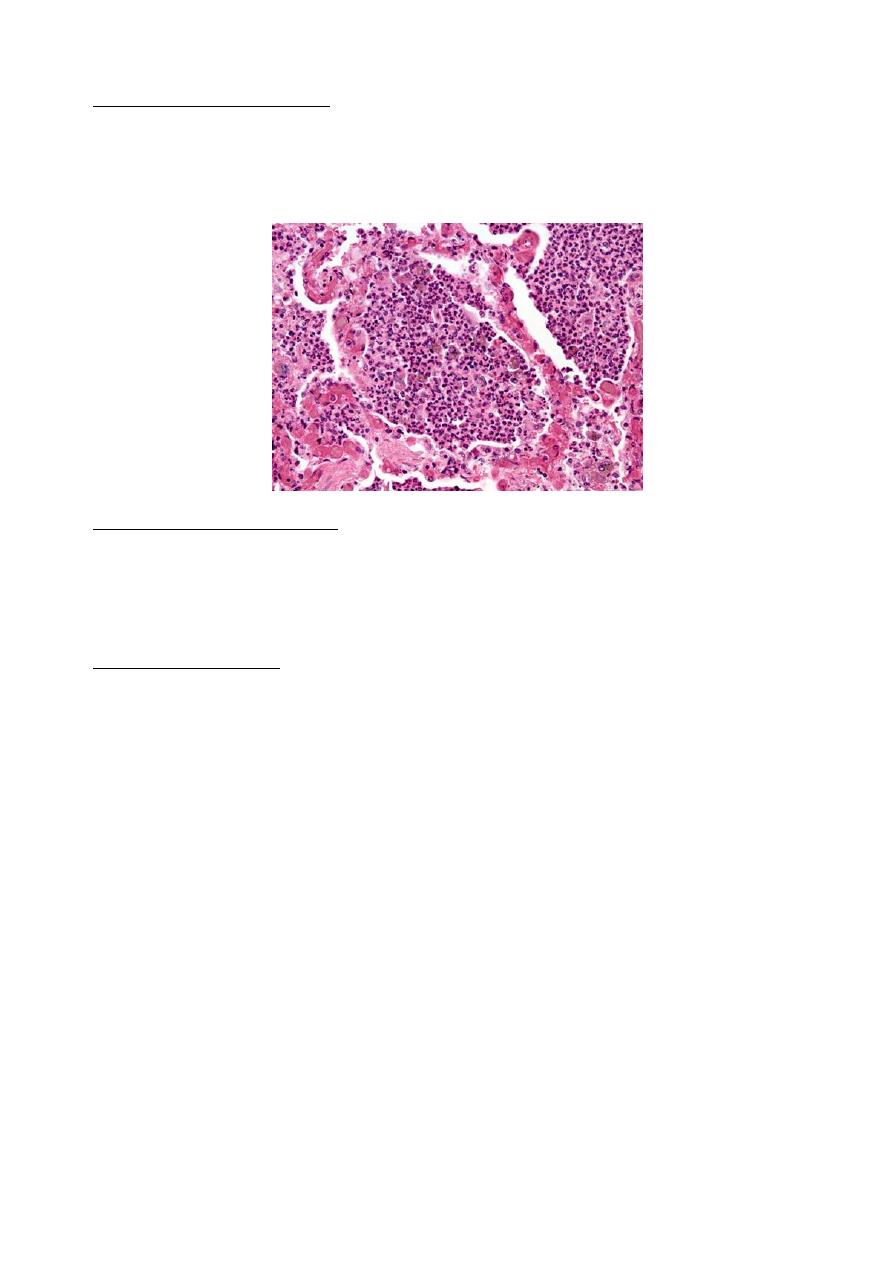

In lobar pneumonia

, four stages of the inflammatory response have classically been

described: congestion, red hepatization, gray hepatization, and resolution. Present-day

effective antibiotic therapy frequently slows or halts the progression.

In the first stage of congestion:

Heavy, boggy, and red lung.

Intraalveolar fluid with few neutrophils.

Presence of numerous bacteria.

4

The stage of red hepatization:

Massive confluent exudation with red cells (congestion).

Neutrophils and fibrin filling the alveolar spaces.

Liver like consistency of the affected lobe (firm, red, and airless).

The stage of grey hepatization:

Disintegration of red cells.

Persistence of fibrinosuppurative exudates.

Grayish brown dry surfaces.

The stage of resolution:

-

the exudates undergoes progressive enzymatic digestion of the inflammatory exudates

produce a granular, semifluid debris that is resorbed, ingested by macrophages, coughed

up, or organized.

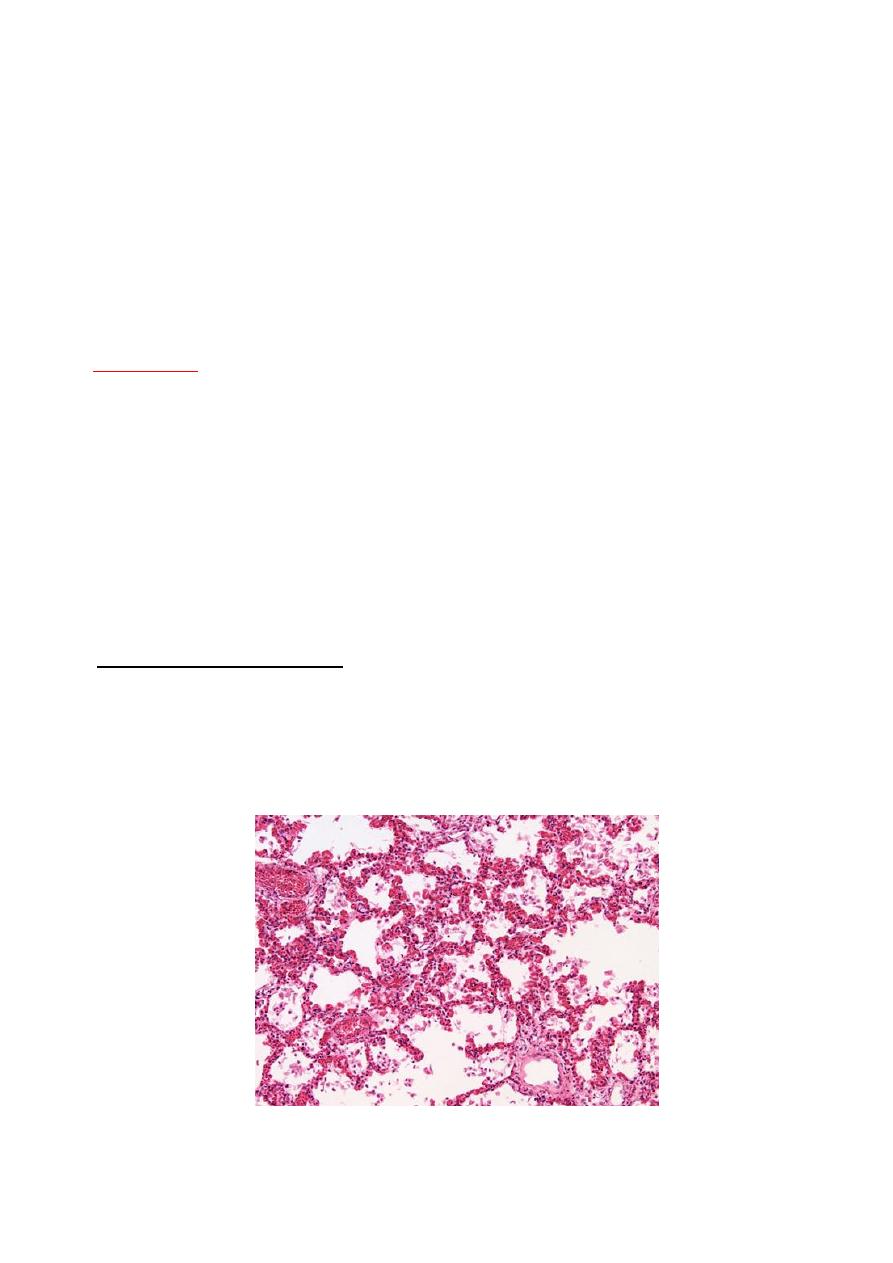

Bronchopneumonia:

They are consolidated areas of acute supportive inflammation. The consolidation may be

patchy through one lobe , multilobular, or bilateral. Well-developed lesions are usually 3

to 4 cm in diameter, dry granular, gray red to yellow.

Histologically.

Suppurative, neutrophil- rich exudates that full the bronchi, bronchioles,

and adjacent alveolar spaces.

COMPLICATIONS:

1. abcess formation.

2. Empyema.

3. Organization of the exudates.

4. Bacterial dissimination.

5

C/F: high fever, productive cough, may have hemoptysis.

RX: antibiotic therapy.

Mubark A. Wilkins

Bronchopneumonia

Lobar pneumonia