Fifth stage

PediatricLec. 1

د. اوس

8/3/2017

Acute Gastroenteritis inChildreninfections of the gastrointestinal tract

caused by bacterial, viral, or parasitic pathogens

Many of these infections are foodborne illnesses

The most common manifestations are diarrhea and vomiting, which can also be associated with systemic features such as abdominal pain and fever.

Diarrheal disorders in childhood account for a large proportion (9%) of childhood deaths, with an estimated 0.71 million deaths per year globally,

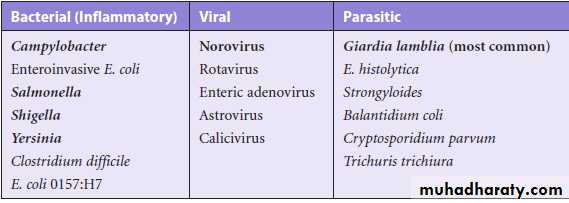

ETIOLOGY OF DIARRHEA

Gastroenteritis is the result of infection acquired through the fecal–oral route or by ingestion of contaminated food or waterGastroenteritis is associated with poverty, poor environmental hygiene, and development indices.

PATHOGENESIS OF INFECTIOUS DIARRHEA

1- noninflammatory diarrhea through enterotoxin production by some bacteria, destruction of villus (surface) cells by viruses, adherence by parasites, and adherence and/or translocation by bacteria2- Inflammatory diarrhea is usually caused by bacteria that directly invade the intestine or produce cytotoxins

Risk factors for diarrhea

Lack of exclusive breastfeeding (0-5 mo)

No breastfeeding (6-23 mo)

Underweight,stunted,wasted

Vitamin A deficiency

Zinc deficiency

Crowding (>8 persons/kitchen)

Indoor air pollution

Unwashed hands

Poor water quality

Inappropriate excreta disposal

Acute diarrhea is defined as the abrupt onset of 3 or more loose stools per day and lasts no longer than 14 days

Consider the following to determine the source/cause of the patient’s diarrhea:

HISTORY

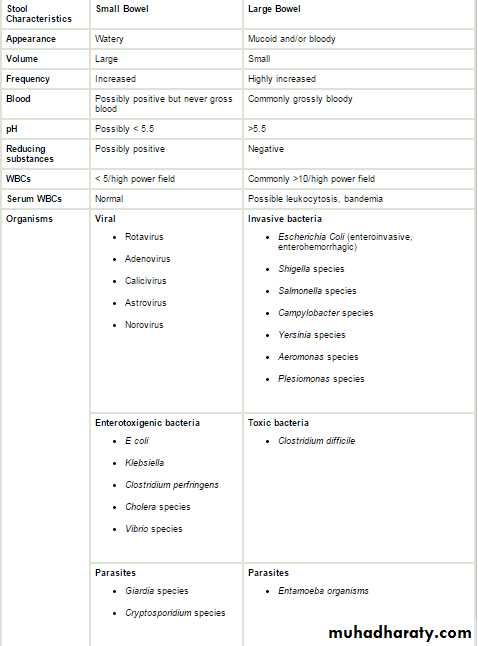

Stool characteristics (eg, consistency, color, volume, frequency)Although nausea and vomiting are nonspecific symptoms, they indicate infection in the upper intestine,,(vomiting proceed diarrhea in rota virus infection)

Fever suggests an inflammatory process(inflammatory diarrhea) but also occurs as a result of dehydration or coinfection (e.g., urinary tract infection, otitis media)called also parenteral diarrhea(etiology outside the G.I system

Severe abdominal pain, tenesmus and bloody diarrhoea indicate involvement of the large intestine and rectum.

Food ingestion history (eg, raw/contaminated foods, food poisoning)

Use of child daycare (common pathogens: rotavirus, astrovirus, calicivirus;Campylobacter, Shigella, Giardia, and Cryptosporidium species [spp])

Water exposure (eg, swimming pools, marine environment)

Camping history (possible exposure to contaminated water sources)

Travel history (common pathogens affect specific regions; also consider rotavirus and Shigella, Salmonella, and Campylobacter spp regardless of specific travel history, as these organisms are prevalent worldwide)

Animal exposure (eg, young dogs/cats: Campylobacter spp; turtles:Salmonella spp)

Predisposing conditions (eg, hospitalization, antibiotic use, immunocompromised state)

Rotavirus infection

typically begins after an incubation period of <48 hr with mild to moderate fever as well as vomiting, followed by the onset of frequent, watery stools. All 3 symptoms are present in about 50-60% of cases. Vomiting and fever typically abate during the 2nd day of illness, but diarrhea often continues for 5-7 days. The stool is without gross blood or white blood cells. Dehydration may develop and progress rapidly, particularly in infants. The most severe disease typically occurs among children 4-36 mo of age. Malnourished children and children with underlying intestinal disease, are particularly likely to acquire severe rotavirus diarrheaCholera

Cholera is a rapidly dehydrating diarrheal disease that can lead to death, if appropriate treatment is not provided immediatelyThe disease is caused by Vibrio cholerae, a gram-negative comma-shaped bacillus, subdivided into serogroups by its somatic O antigen

Large inocula of bacteria are required for severe cholera to occur; however, for persons whose gastric barrier is disrupted, a much lower dose is required

Most cases of cholera are mild or inapparent. Among symptomatic cases, around 20% develop severe dehydration that can rapidly lead to death. Following an incubation period of 1 to 3 days

Diarrhea can progress to painless purging of profuse rice-water stools (suspended flecks of mucus) with a fishy smell, which is the hallmark of the disease. Vomiting with clear watery fluid is usually present at the onset of the disease

Stool examination reveals few fecal leukocytes and erythrocytes because cholera does not cause inflammation. Dark-field microscopy may be used for rapid identification of typical “darting motility

Rehydration is the mainstay of therapy ,, Doxycycline (adults and older children): 300 mg given as a single dose

Erythromycin 12.5 mg/kg/dose 4 times a day ? 3 days

BLOODY DIARRHEA

Causes of bloody diarrhoea (real or apparent) in infants and children Infants aged <1 year1- Intestinal infection (shigella, salmonella, E-coli, campylobacter, Yersinia and Clostridium difficile) And Entamoeba histolytica

2- Infant colitis(Cow’s milk colitis)—non specific allergic colitis

3- rare causes like Intussusception, Malrotation and volvulus

Infants aged >1 year

1- Intestinal infection

2- Inflammatory bowel disease

3- Juvenile polyp

4- rare causes Intussusception , Malrotation and volvulus and Henoch-Schönlein purpura

5-Recent antibiotic use raises suspicion for antibiotic-associated colitis and Clostridium difficile colitis.

Shigella

Shigella causes an acute invasive enteric infection clinically manifested by diarrhea that is often bloody

The term dysentery is used to describe the syndrome of bloody diarrhea with fever, abdominal cramps, rectal pain, and mucoid stools

Bacillary dysentery is a term often used to distinguish dysentery caused by Shigella from amoebic dysentery caused by Entamoeba histolytica

Four species of Shigella are responsible for bacillary dysentery: S. dysenteriae (serogroup A), S. flexneri (serogroup B), S. boydii (serogroup C), and S. sonnei (serogroup D).

Most children never progress to the stage of bloody diarrhea, but some have bloody stools from the outset

The most common complication of shigellosis is dehydration

Neurologic findings are among the most common extraintestinal manifestations of bacillary dysentery, occurring in as many as 40% of hospitalized children. Enteroinvasive E. coli can cause similar neurologic toxicity. Convulsions, headache, lethargy, confusion, nuchal rigidity, or hallucinations may be present before or after the onset of diarrhea

EXAMINATION

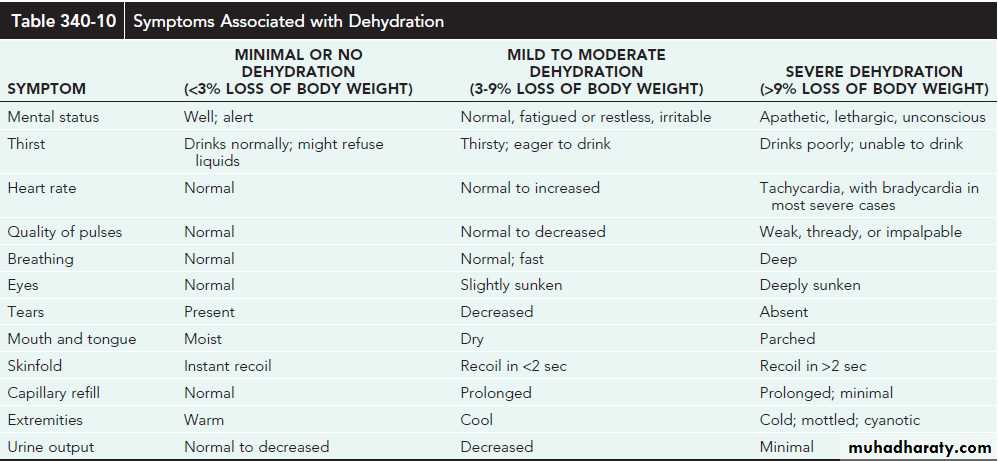

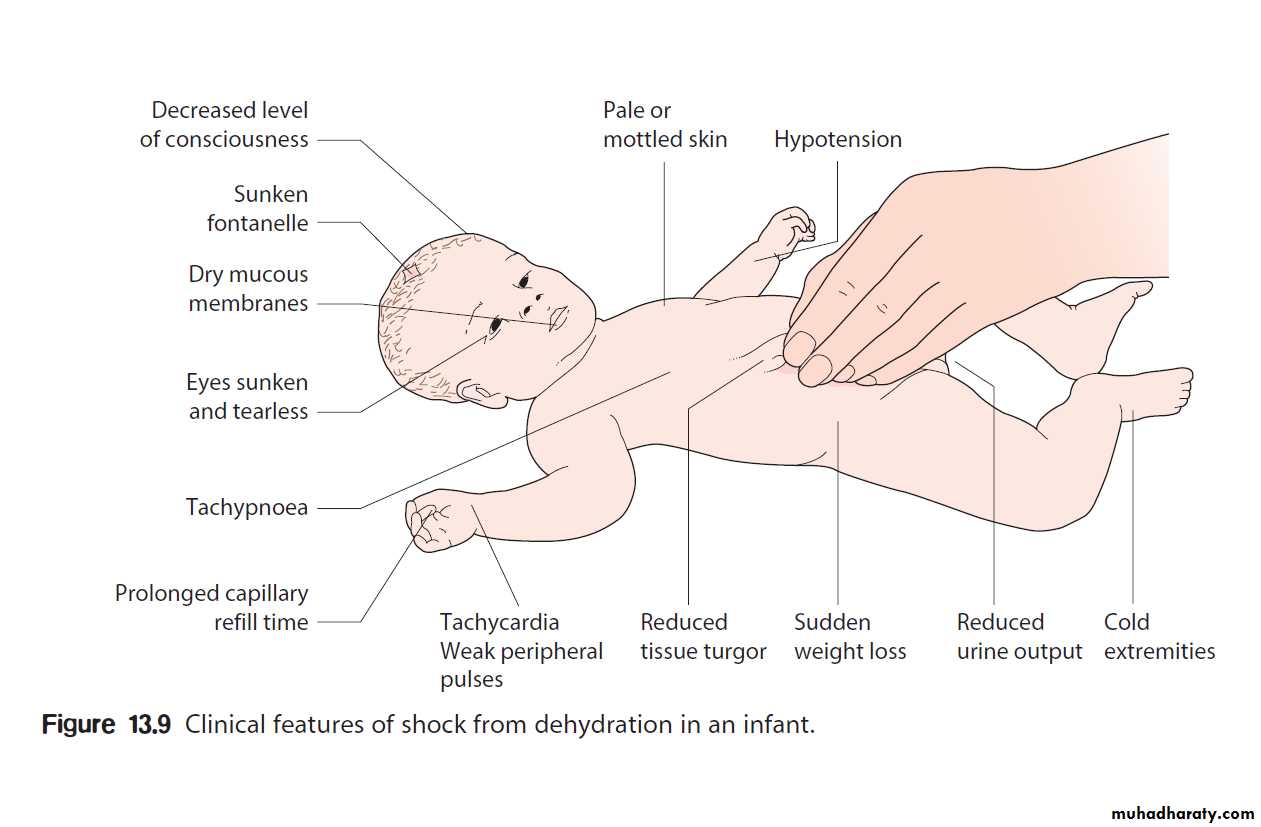

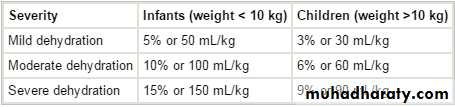

Assessing the degree of dehydration and acidosis

Investigations

1-Stool ExaminationA-Microscopic examination of the stool: Fecal leukocytes and RBC indicate bacterial invasion of colonic mucosa, stool microscopy must include examination for parasites causing diarrhea, such as G. lamblia and E. histolytica

B- Stool culture is required if the child appears septic, if there is blood or mucus in the stools or the child is immunocompromised.It may be indicated following recent foreign travel, if the diarrhoea has not improved by day 7 or the diagnosis is uncertain

3- Plasma electrolytes, urea, creatinine and glucose should be checked if intravenous fluids are required or there are features suggestive of hypernatraemia.

4- If antibiotics are started, a blood culture should be taken.

5- urinalysis to exclude UTI (parenteral diarrhea)

6- XTAG GPP is an FDA-approved gastrointestinal pathogen panel using multiplexed nucleic acid technology that detects Campylobacter,C. difficile, toxin A/B, E. coli 0157, enterotoxigenic E. coli, Salmonella,Shigella, Shiga-like toxin E. coli, norovirus, rotavirus A, Giardia, and Cryptosporidium

7- Enzyme immunoassay for rotavirus or adenovirus antigens

Treatment

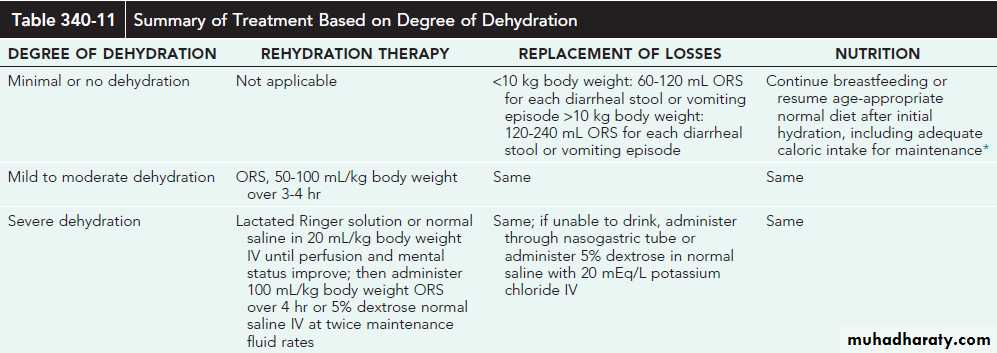

ORS

The low-osmolality World Health Organization (WHO) oral rehydration solution (ORS) containing 75 mEq of sodium, 64 mEq of chloride, 20 mEq of potassium, and 75 mmol of glucose per liter, with total osmolarity of 245 mOsm/L, is now the global standard of care and more effective than home fluids, including decarbonated soda beverages, fruit juices, and tea. These are not suitable for rehydration or maintenance therapy because they have inappropriately high osmolalities and low sodium concentrations.

Oral rehydration should be given to infants and children slowly, especially if they have emesis. It can be given initially by a dropper, teaspoon, or syringe, beginning with as little as 5 mL at a time .The volume is increased as tolerated.

Oral rehydration can also be given by a nasogastric tube if needed; this is not the usual route.

Limitations to oral rehydration therapy include shock, an ileus, intussusception, carbohydrate intolerance (rare), severe emesis, and high stool output (>10 mL/kg/hr)

DEHYDRATION (total body deficit of sodium and water)

The following children are at increased risk of dehydration:Infants, particularly those under 6 months of age or those born with low birthweight.

If they have passed ≥6 diarrhoeal stools in the previous 24 h

If they have vomited three or more times in the previous 24 h

If they have been unable to tolerate (or not been offered) extra fluids

If they have malnutrition

Infants are at particular risk of dehydration because they have a greater surface area to weight ratio than older children, leading to greater insensible water losses (300 ml/m2 per day, equivalent in infants to 15–17 ml/kg per day). They have higher basal fluid requirements (100–120 ml/kg per day, i.e. 10–12% of bodyweight) and immature renal tubular reabsorption. In addition, they are unable to obtain fluids for themselves when thirsty.

Hypernatraemic dehydration ( sodium concentration >150 mEq/L)

Infrequently, water loss exceeds the relative sodium loss and plasma sodium concentration increases (hypernatraemic dehydration). This usually results from high insensible water losses (high fever or hot, dry environment)or from profuse, low-sodium diarrhea. The extracellular fluid becomes hypertonic with respect to the intracellular fluid, which leads to a shift of water into the extracellular space from the intracellular compartment. Signs of extracellular fluid depletion are therefore less per unit of fluid loss, and depression of the fontanelle, reduced tissue elasticity and sunken eyes are less obvious. This makes this form of dehydration more difficult to recognise clinically , particularly in an obese infant.It is a particularly dangerous form of dehydration as water is drawn out of the brain and cerebral shrinkage within a rigid skull may lead to jittery movements, increased muscle tone with hyper reflexia, altered consciousness, seizures and multiple, small cerebral haemorrhages.

If the serum sodium concentration is lowered rapidly, there is movement of water from the serum into the brain cells to equalize the osmolality in the 2 compartments . The resultant brain swelling manifests as seizures or coma.

Because of the associated dangers, hypernatremia should not be corrected rapidly. The goal is to decrease the serum sodium by <12 mEq/L every 24 hr-- The fluid deficit should be replaced over at least 48 h and the plasma sodium measured regularly

Isonatraemic dehydration (sodium 135-150 meq/l)

the losses of sodium and water are proportional and plasma sodium remains within the normal range

Most common type

Hyponatraemic dehydration: (serum sodium level <135 mEq/L)

When children with diarrhoea drink large quantities of water or other hypotonic solutions, there is a greater net loss of sodium than water, leading to a fall in plasma sodium (hyponatraemic dehydration). This leads to a shift of water from extra- to intracellular compartments. The increase in intracellular volume leads to an increase in brain volume, which may result in convulsions, whereas the marked extracellular depletion leads to a greater degree of shock per unit of water loss. Thisform of dehydration is more common in poorly nourished infants in developing countries.

Severe dehydration (TREATMENT)

Phase 1 : focuses on emergency management. Severe dehydration is characterized by a state of hypovolemic shock requiring rapid treatment. Initial management includes placement of an intravenous or intraosseous line and rapid administration of 20 mL/kg of an isotonic crystalloid (eg, lactated Ringer solution, 0.9% sodium chloride). Additional fluid boluses may be required depending on the severity of the dehydration. The child should be frequently reassessed to determine the response to treatment. As intravascular volume is replenished, tachycardia, capillary refill, urine output, and mental status all should improve. If improvement is not observed after 60 mL/kg of fluid administration, other etiologies of shock (eg, cardiac, anaphylactic, septic) should be considered. Hemodynamic monitoring and inotropic support may be indicated.Phase 2: focuses on deficit replacement, provision of maintenance fluids, and replacement of ongoing losses. Maintenance fluid requirements are equal to measured fluid losses (urine, stool) plus insensible fluid losses. Normal insensible fluid loss is approximately 400-500 mL/m2 body surface area and may be increased by factors such as fever and tachypnea.

Alternatively, daily fluid requirements may be roughly estimated as follows:

Less than 10 kg = 100 mL/kg

10-20 kg = 1000 + 50 mL/kg for each kg over 10 kg

Greater than 20 kg = 1500 + 20 mL/kg for each kg over 20 kg

Severe dehydration by clinical examination suggests a fluid deficit of 10-15% of body weight in infants and 6-9% of body weight in older children. The daily maintenance fluid is added to the fluid deficit. In general, the recommended administration is one half of this volume administered over 8 hours and administration of the remainder over the following 16 hours. Continued losses (eg, emesis, diarrhea) must be promptly replaced.

If the child is isonatremic (130-150 mEq/L), the sodium deficit incurred can generally be corrected by administering the fluid deficit plus maintenance as 5% dextrose in 0.45-0.9% sodium chloride. Potassium (20 mEq/L potassium chloride) may be added to maintenance fluid once urine output is established and serum potassium levels are within a safe range.

Enteral Feeding and Diet Selection

Continued enteral feeding in diarrhea aids in recovery from the episode, and a continued age-appropriate diet after rehydration is the norm.

Once rehydration is complete, food should be reintroduced while oral rehydration is continued to replace ongoing losses from emesis or stools and for maintenance. Breastfeeding or non diluted regular formula should be resumed as soon as possible. Foods with complex carbohydrates (rice, wheat, potatoes, bread, and cereals), lean meats, yogurt, fruits, and vegetables are also tolerated

Fatty foods or foods high in simple sugars (juices, carbonated sodas) should be avoided.

Zinc Supplementation

Zinc administration for diarrhea management can significantly reduce all cause mortality by 46% and hospital admission by 23%. Also reduce duration and severity of diarrhea

All children older than 6 mo of age with acute diarrhea in at-risk areas should receive oral zinc (20 mg/day) in some form for 10-14 days during and continued after diarrhea.

Additional Therapies

The use of probiotic nonpathogenic bacteria for prevention and therapy of diarrhea has been successful in some settingsSaccharomyces boulardii is effective in antibiotic-associated and in C. difficile diarrhea, and there is some evidence that it might prevent diarrhea in daycare centers. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG is associated with reduced diarrheal duration and severity, which reduction is more evident in cases of childhood rotavirus diarrhea

Antimotility agents (loperamide) are contraindicated in children with dysentery and probably have no role in the management of acute watery diarrhea in otherwise healthy children.

Because persistent vomiting can limit oral rehydration therapy, a single sublingual dose of an oral dissolvable tablet of ondansetron (4 mg 4-11 yr and 8 mg for children older than 11 yr [generally 0.2 mg/kg]) may be given.However, most children do not require specific antiemetic therapy;careful oral rehydration therapy is usually sufficient.

Antibiotic Therapy

antibiotic therapy in select cases of diarrhea related to bacterial infections can reduce the duration and severity of illness and prevent complicationsAlthough these agents are important to use in specific cases, their widespread and indiscriminate use leads to the development of antimicrobial resistance.

PREVENTION

1- Promotion of Exclusive Breastfeeding (administration of no other fluids or foods for the 1st 6 mo of life)2- Improved Complementary Feeding Practices

3- Rotavirus Immunization

4- Improved Water and Sanitary Facilities and Promotion of Personal and Domestic Hygiene

5- Improved Case Management of Diarrhea.

Complications (Extraintestinal Manifestations of Enteric Infections)

1- Focal infections from systemic spread of bacterial pathogens, including vulvovaginitis, urinary tract infection, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, meningitis, pneumonia, hepatitis, peritonitis, chorioamnionitis, soft-tissue infection, and septic thrombophlebitis

2- Reactive arthritis

3- Guillain-Barré syndrome

4- Glomerulonephritis

5- Immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy

6- Erythema nodosum

7- Hemolytic uremic syndrome: Escherichia coli O157:H7

8- Hemolytic anemia