Topographic &Applied anatomy

of the anterior abdominal wall

&surgical incisions

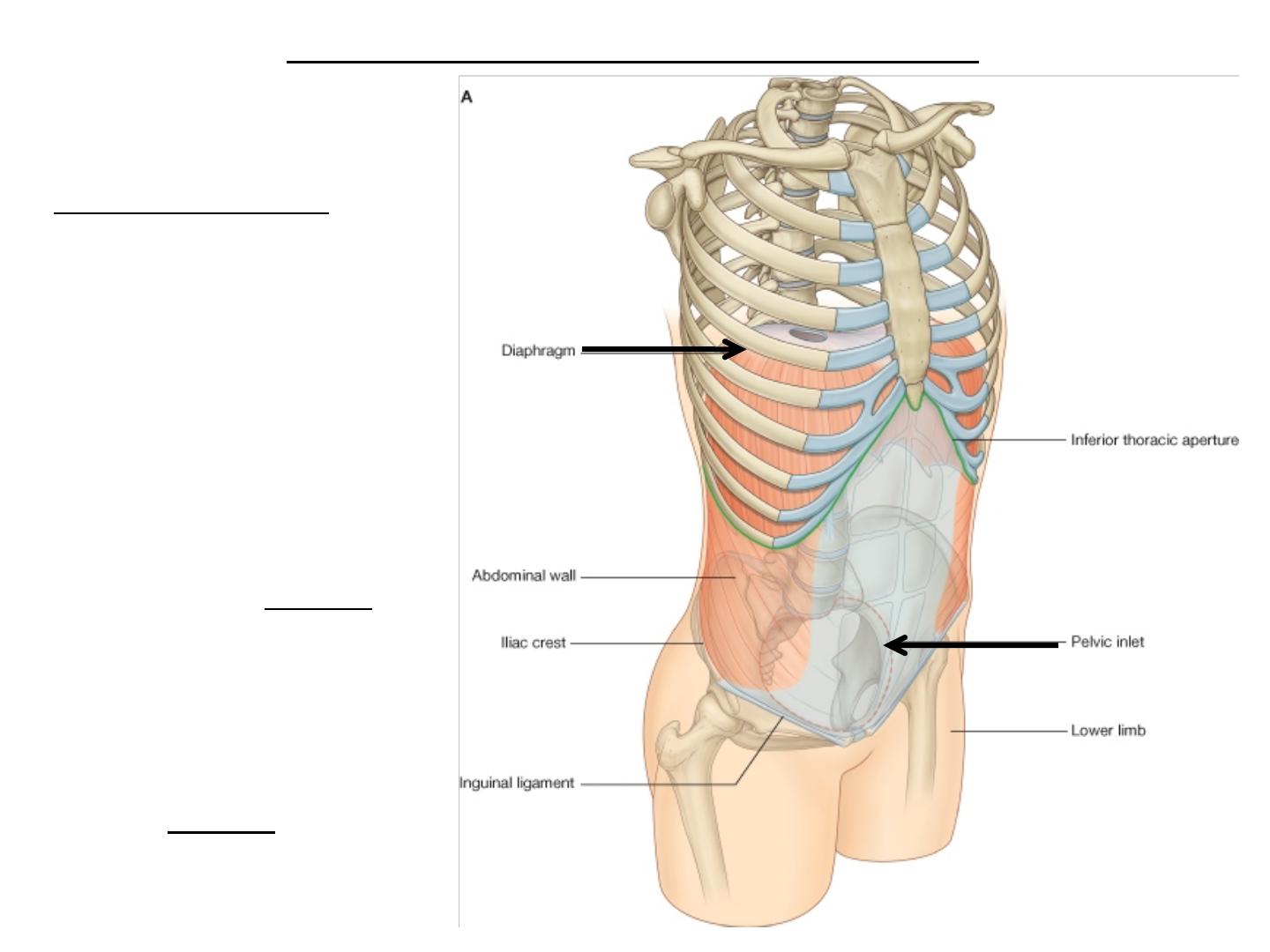

Basic Anatomy

The abdomen is

the region of the

trunk that lies

between the

diaphragm above

and

the inlet of the

pelvis below.

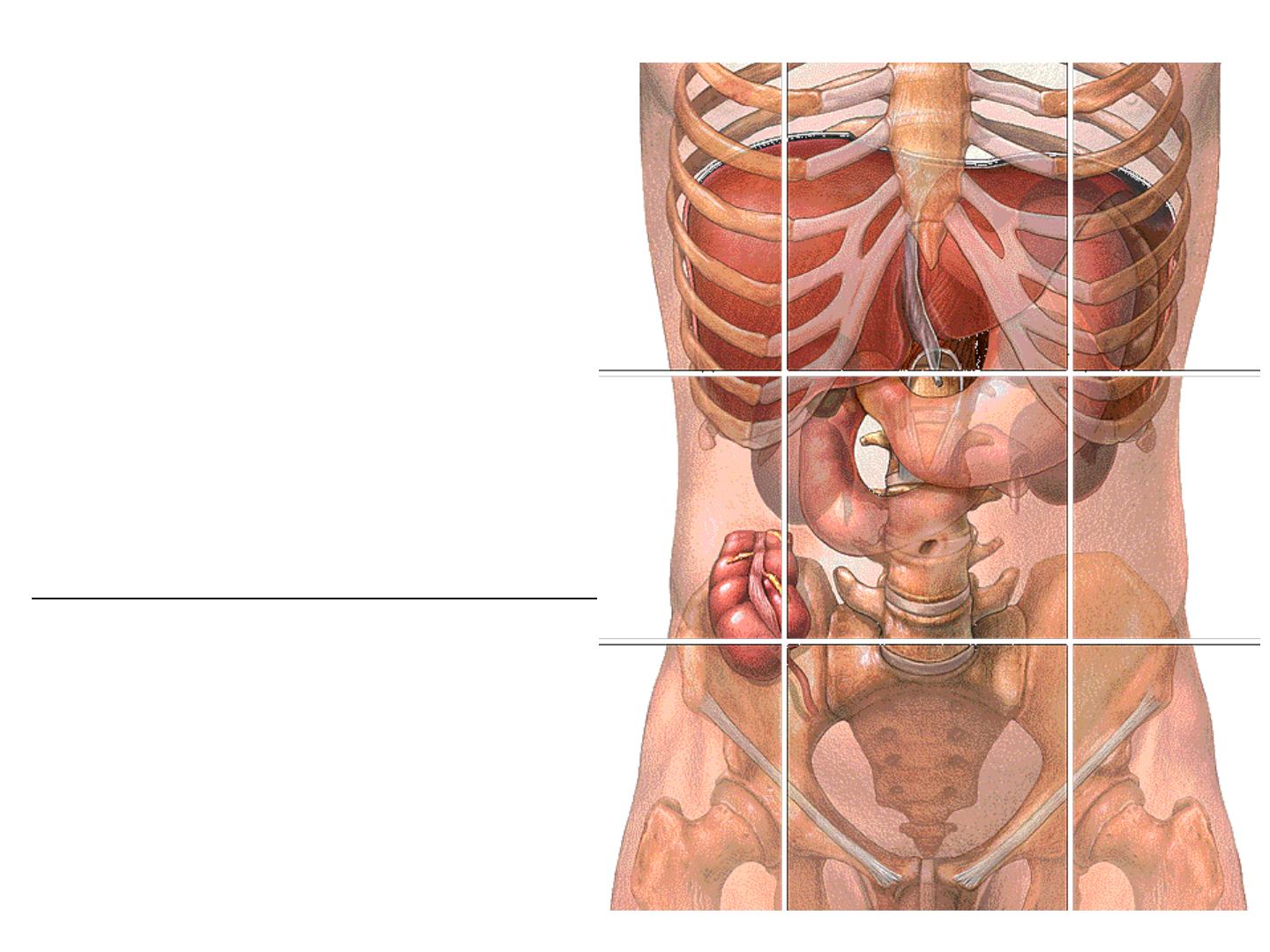

● Extent of the abdominal cavity

The cavity is

larger than the

wall so it extend

up

to the

thoracic cavity

and

down

to the

pelvis

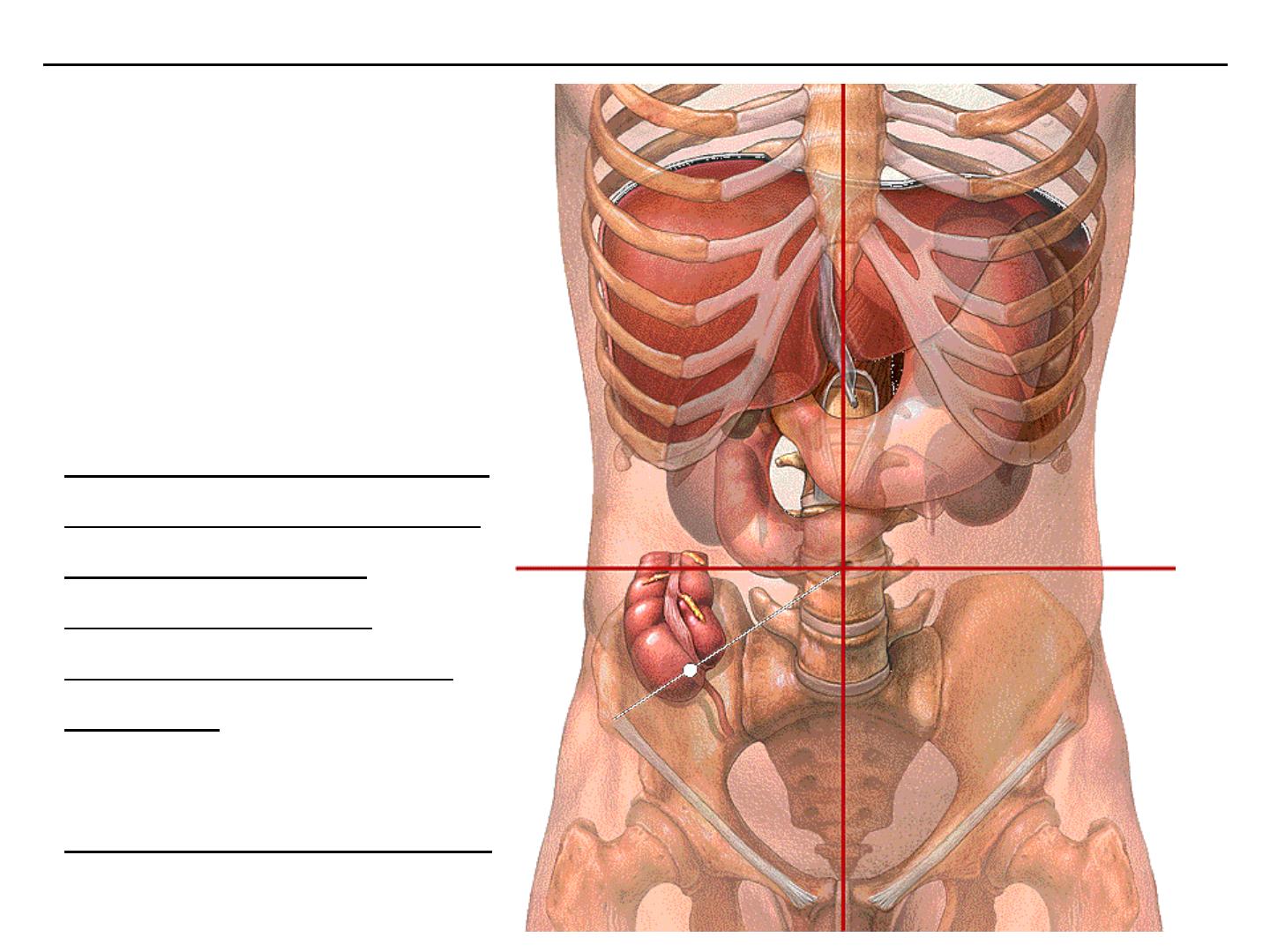

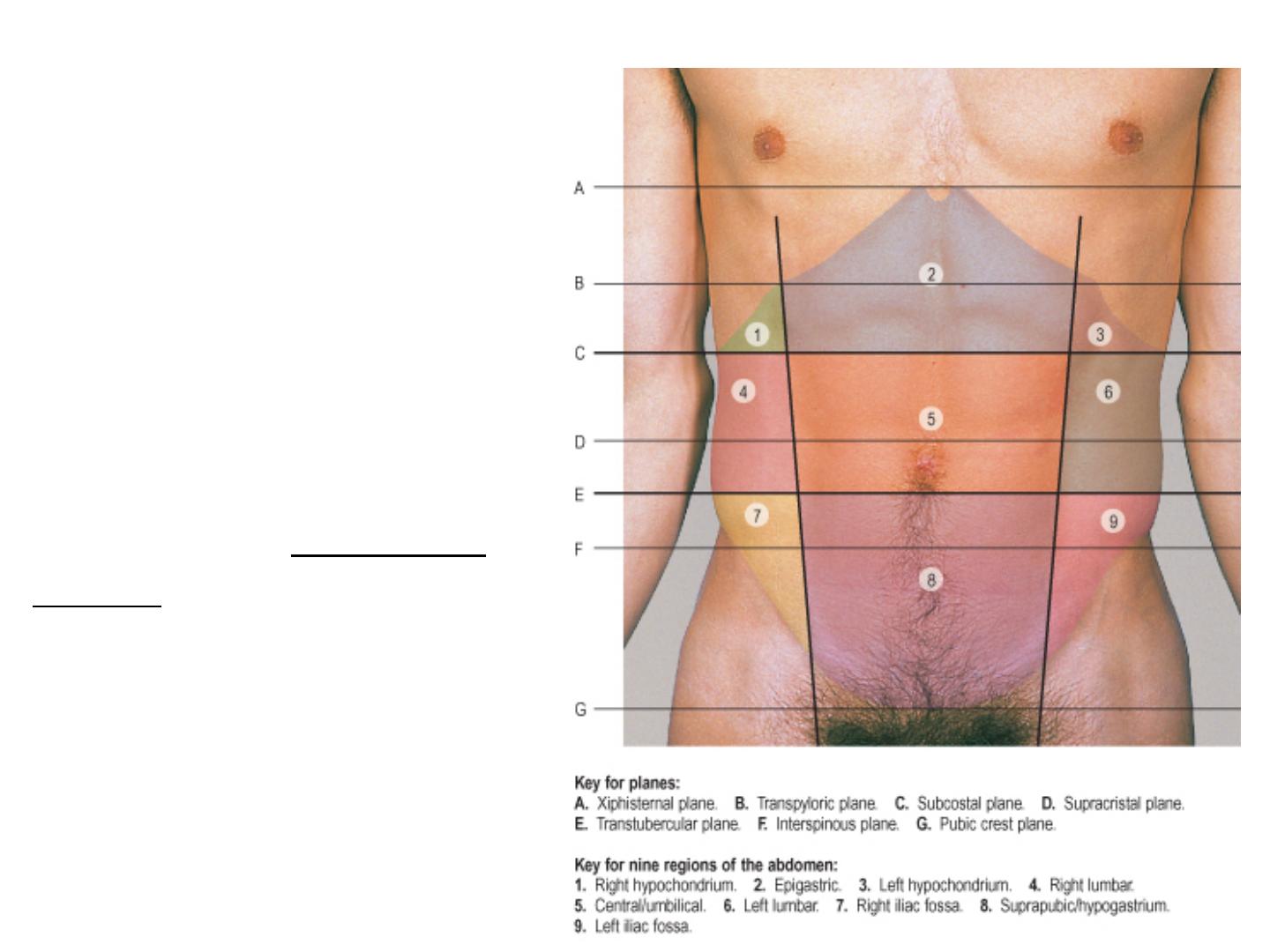

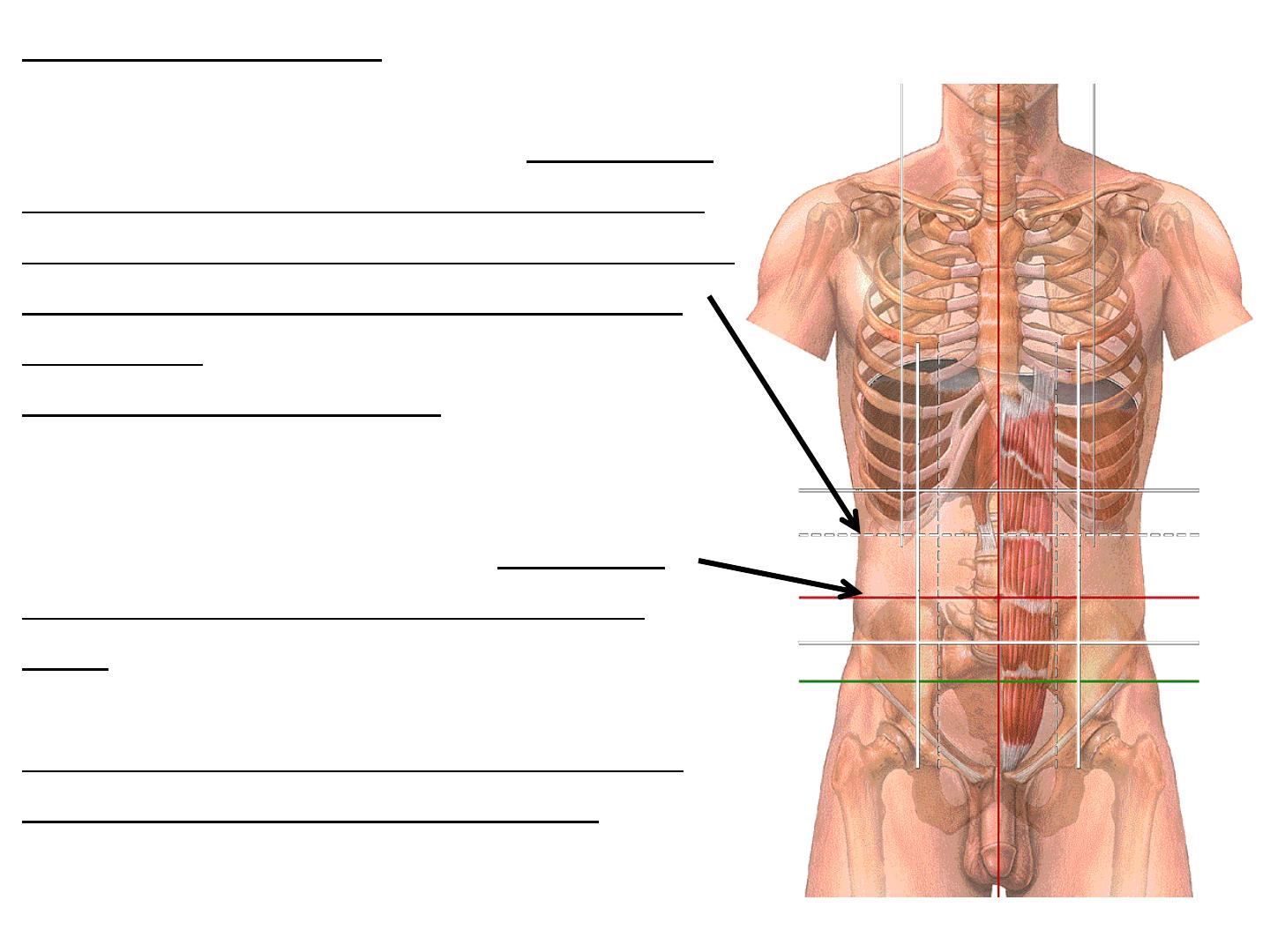

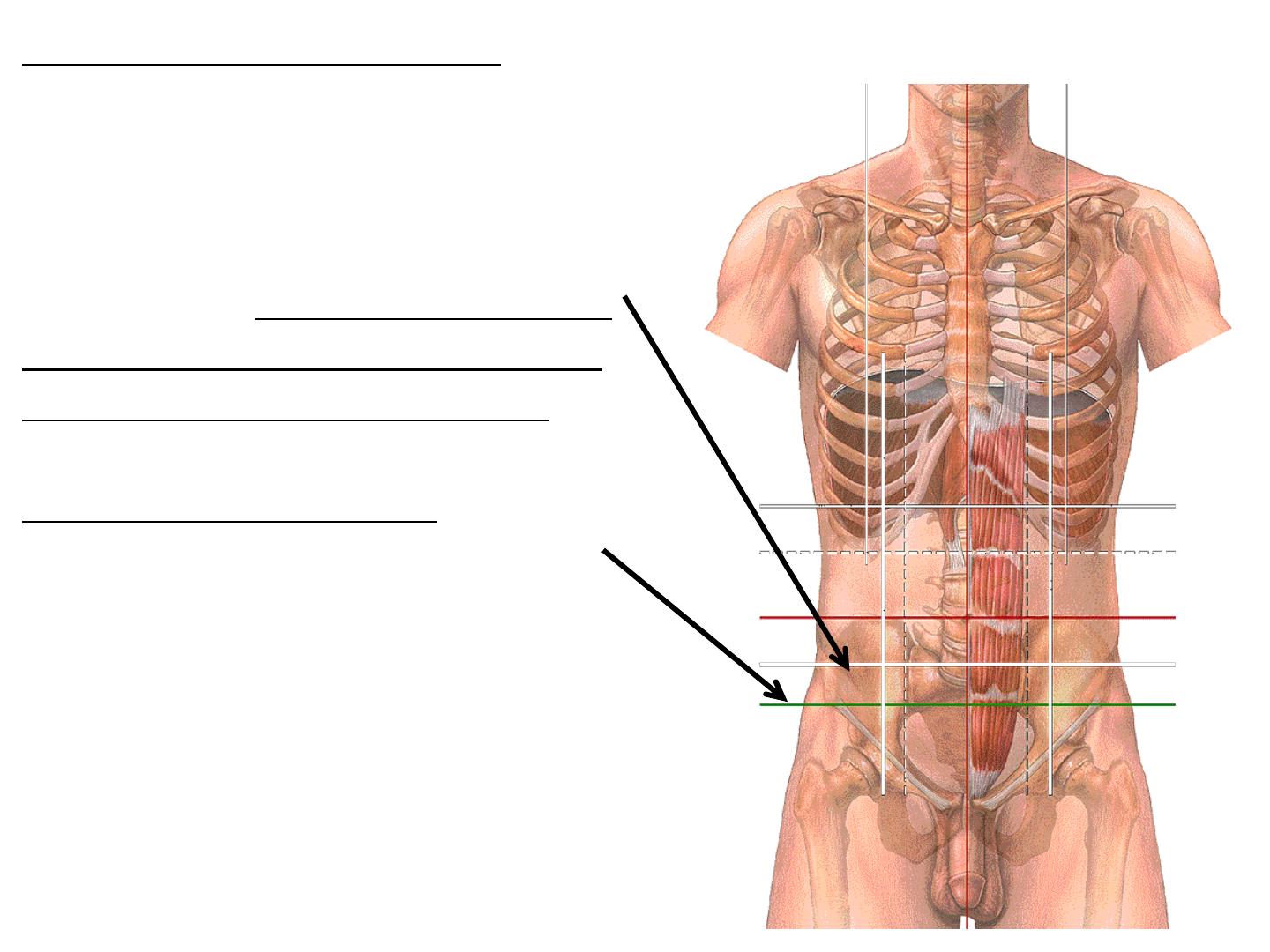

● Topography of the anterior abdominal wall; Planes and regions

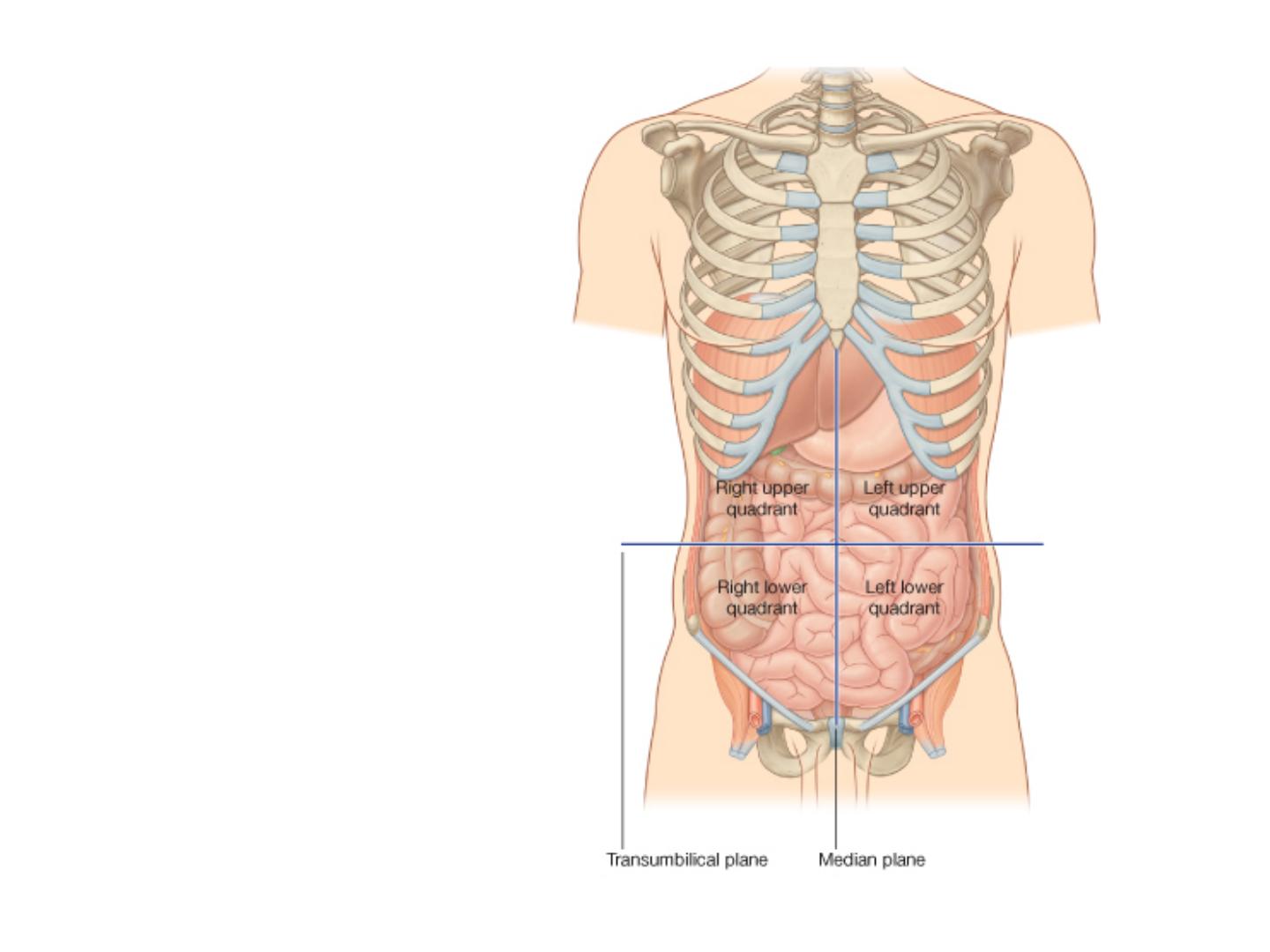

Four-quadrant pattern

For the simple four-

quadrant topographical

pattern a

horizontal transumbilical

plane passes through the

umbilicus and the

intervertebral disc

between vertebrae LIII

and LIV,

intersects with

the vertical median plane

Four-quadrant pattern

to form four quadrants-

the

right upper

,

left

upper

,

right lower

, and

left

lower

quadrants.

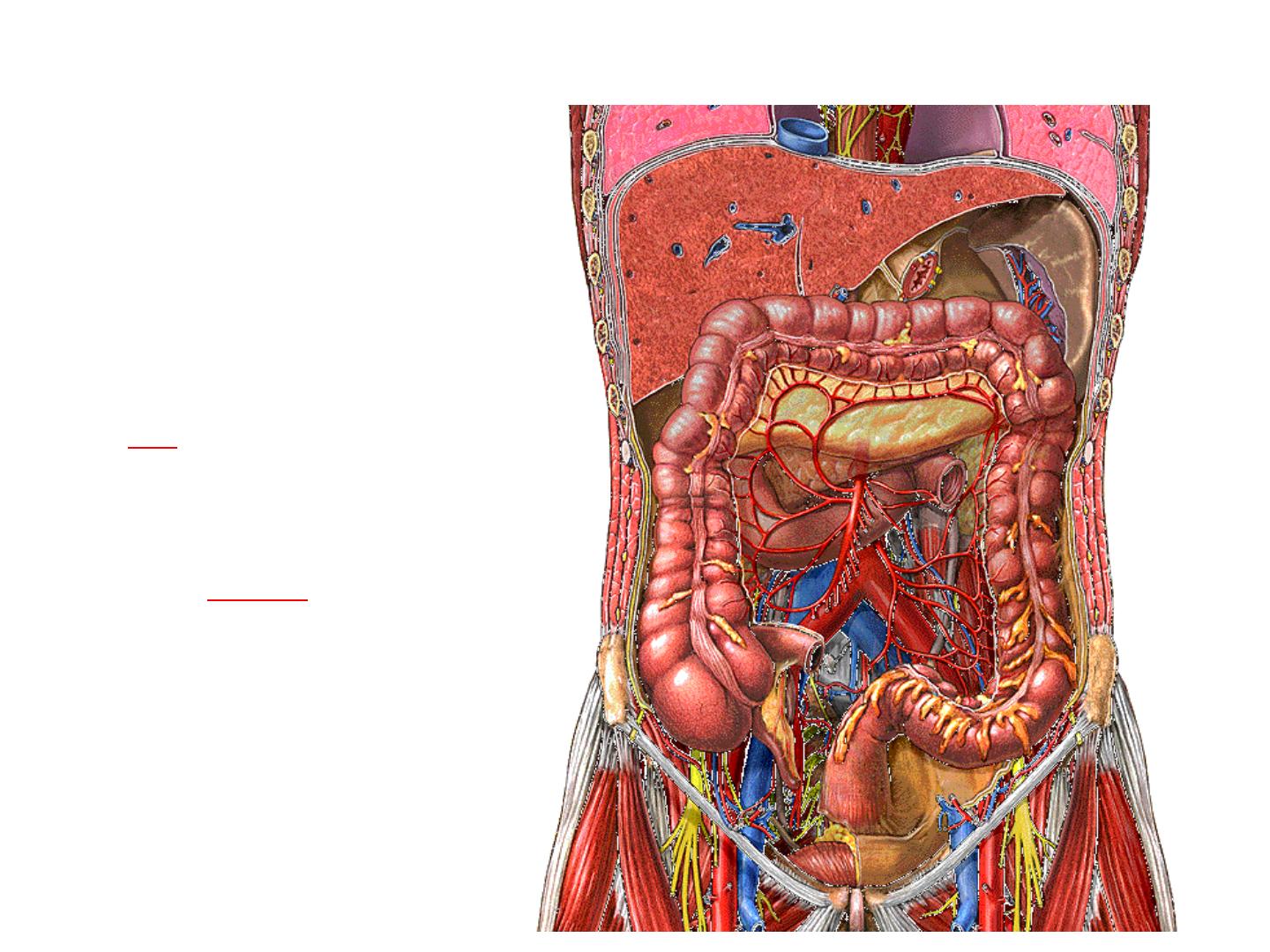

ABDOMINAL PLANES AND

REGIONS

The abdomen can be

divided by a number of

imaginary horizontal and

vertical lines drawn

using the skeletal

landmarks of the thorax

and abdomen. These

lines can be used to

define certain abdominal

'planes'. These planes are

of value in defining

approximate vertebral

levels and the positions of

some relatively fixed

intra-abdominal

structures.

VERTICAL PLANES

In addition to the midline,

which passes through the

xiphisternal process and the

pubic symphysis,

there are two paramedian

planes which are projected from

the midclavicular line. This line

passes through the midpoint of

the clavicle, crosses the costal

margin just lateral to the tip of

the ninth costal cartilage, and

passes through a point mid way

between the anterior superior

iliac spine and the symphysis

pubis.

HORIZONTAL PLANES

The xiphisternal plane

runs horizontally through the

xiphoid processes at the level of

the ninth thoracic vertebra.

The transpyloric plane

lies midway between the

suprasternal notch of the

manubrium and the upper border

of the pubic symphysis. It usually

lies at the level of the body of the

first lumbar vertebra near its lower

border and meets the costal

margins at the tips of the ninth

costal cartilages.

The linea semilunaris crosses

the costal margin on the

transpyloric plane.

The hilum of both kidneys,

the origin of the superior

mesenteric artery, the

termination of the spinal

cord, the neck, adjacent body

and head of the pancreas,

and the confluence of the

superior mesenteric and

splenic veins as they form the

hepatic portal vein may all lie

in this plane.

The subcostal plane

is a line joining the lowest point of the

costal margins. It usually lies at the level

of the body of the third lumbar vertebra,

the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery

from the aorta, and the third part of the

duodenum.

The supracristal plane joins the highest

point of the iliac crest on each side. It

usually lies at the level of the body of the

fourth lumbar vertebra, and marks the

level of bifurcation of the abdominal

aorta.

On the posterior abdominal surface, is

used to perform lumbar puncture at the

L4-5 or L5-S1 intervertebral level, which

is safely below the termination of the

spinal cord.

The transtubercular plane

joins the tubercles of the iliac crests

and usually lies at the level of the

body of the fifth lumbar vertebra

near its upper border. It indicates, or

is just above, the confluence of the

common iliac veins and marks the

origin of the inferior vena cava.

The interspinous plane

joins the centres of the anterior

superior spines of the iliac crests. It

passes through either the

lumbosacral disc, or the sacral

promontory, or just below them,

depending on the degree of lumbar

lordosis, sacral inclination and

curvature.

ABDOMINAL REGIONS

The abdomen can be divided into

nine regions by the subcostal and

transtubercular planes and the two

midclavicular planes. These regions

are used in practice for descriptive

localization of the position of a mass

or the localization of a patient's pain.

They may also be used in the

description of the location of the

abdominal viscera.

The nine regions thus formed are:

epigastrium;

right and left hypochondrium;

central or umbilical;

right and left lumbar;

hypogastrium or suprapubic;

right and left iliac fossa.

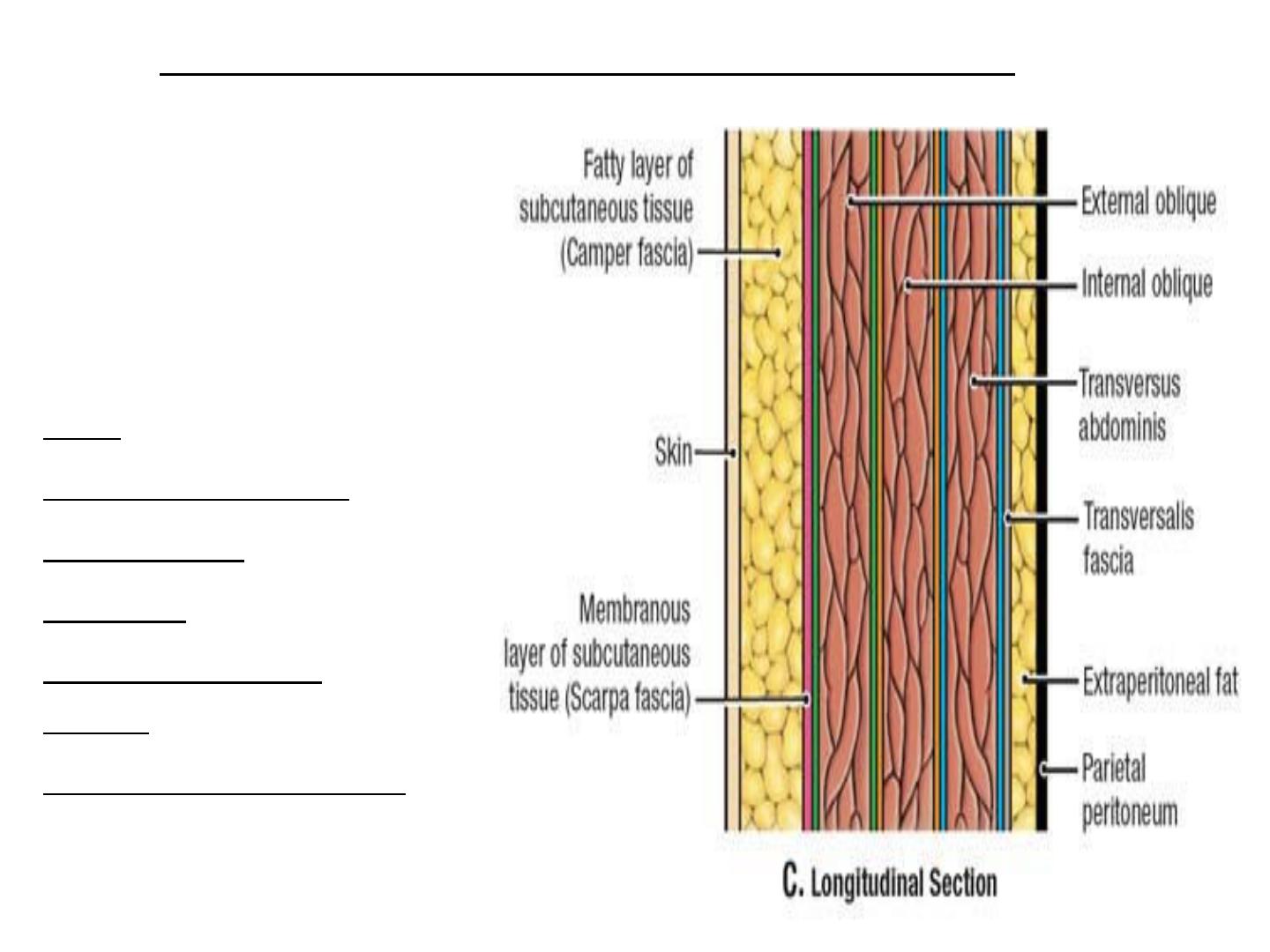

The anterior

abdominal wall is

made up of;

skin,

superficial fascia,

deep fascia,

muscles,

extraperitoneal

fascia, and

parietal peritoneum.

● Layers of the anterior abdominal wall.

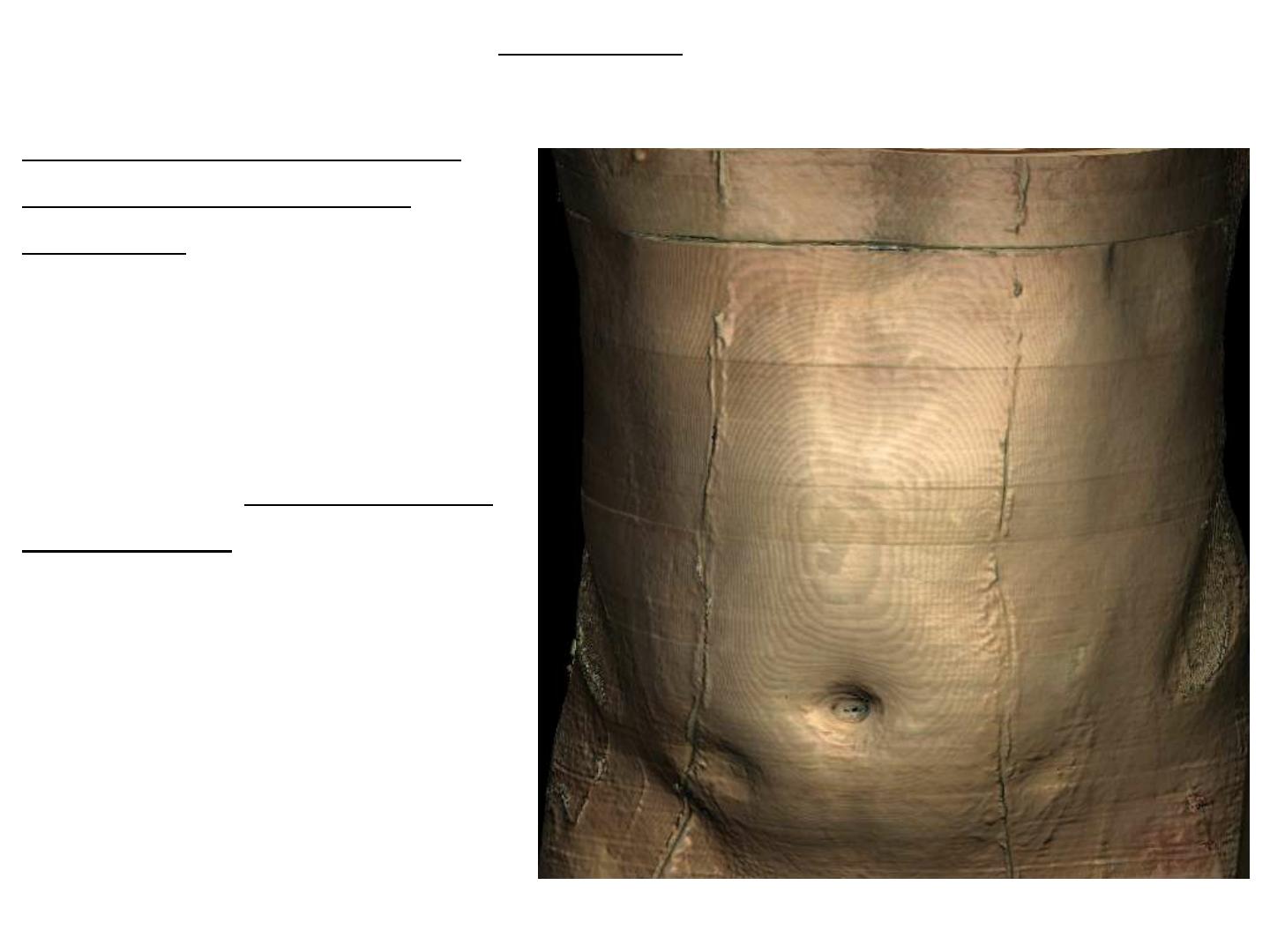

●The skin

۩The skin is loosely

attached to the underlying

structures except at the

umbilicus, where it is

tethered to the scar tissue.

۩The natural lines of

cleavage in the skin are

constant and run downward

and forward almost

horizontally around the

trunk.

۩The umbilicus is a scar

representing the site of

attachment of the umbilical

cord in the fetus; it is situated

in the linea alba.

Clinical Notes

Surgical Incisions

All surgical incisions should be made in the lines of cleavage where

the bundles of collagen fibers in the dermis run in parallel rows. An

incision along a cleavage line will heal as a narrow scar, whereas one

that crosses the lines will heal as wide scars.

Infection of the Umbilicus

In the adult, the umbilicus often receives scant attention in the shower

and is consequently a common site of infection.

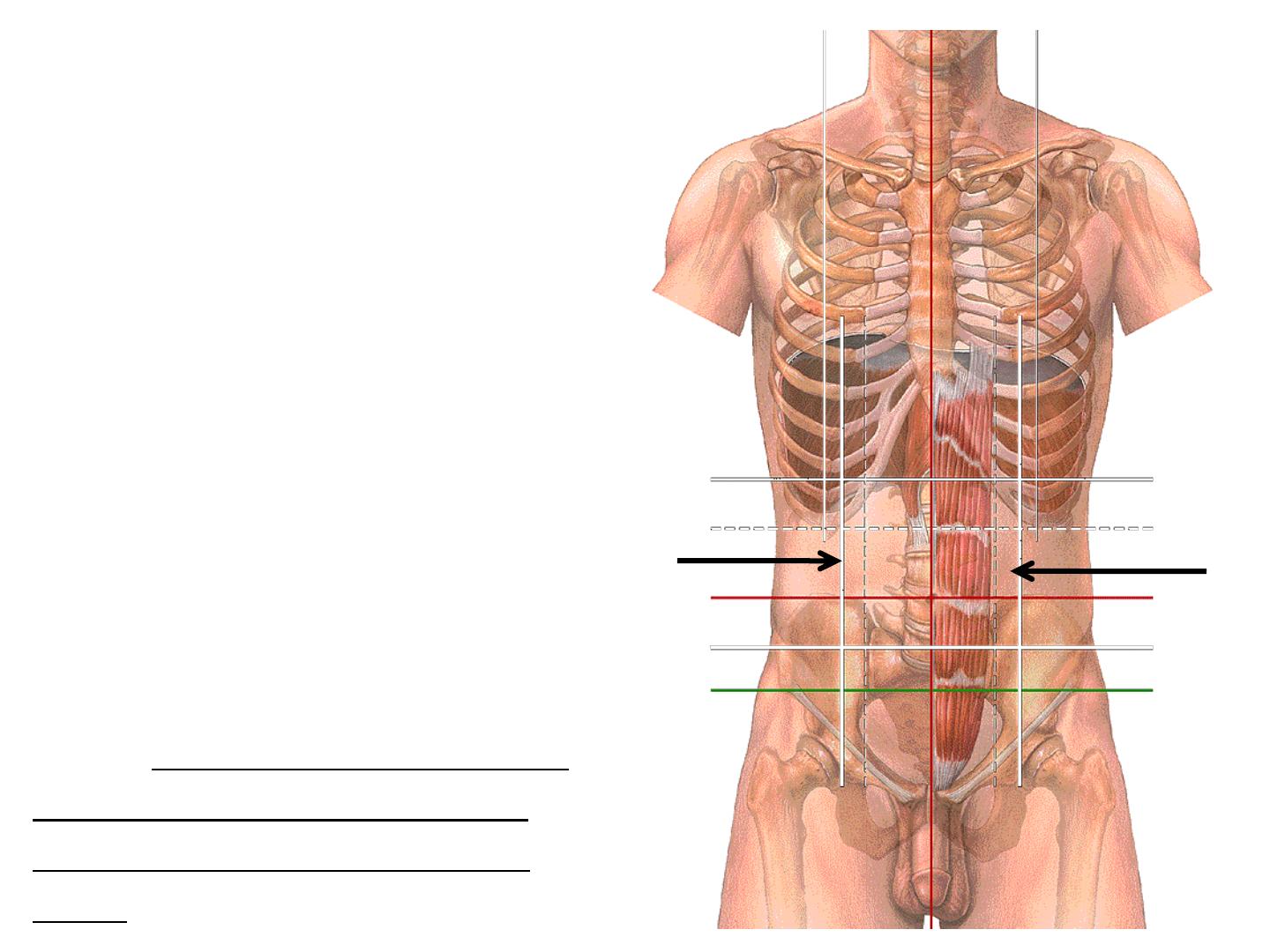

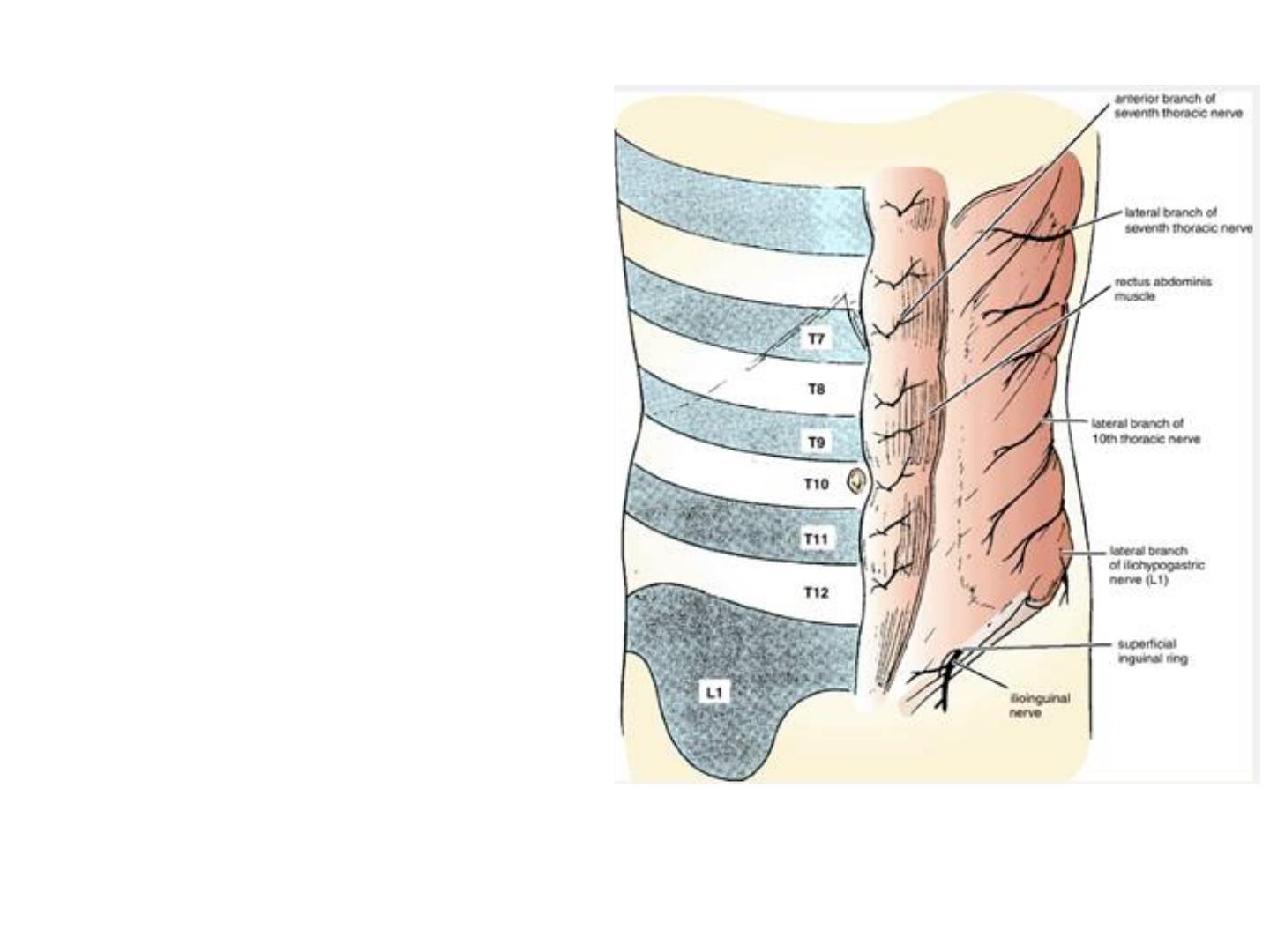

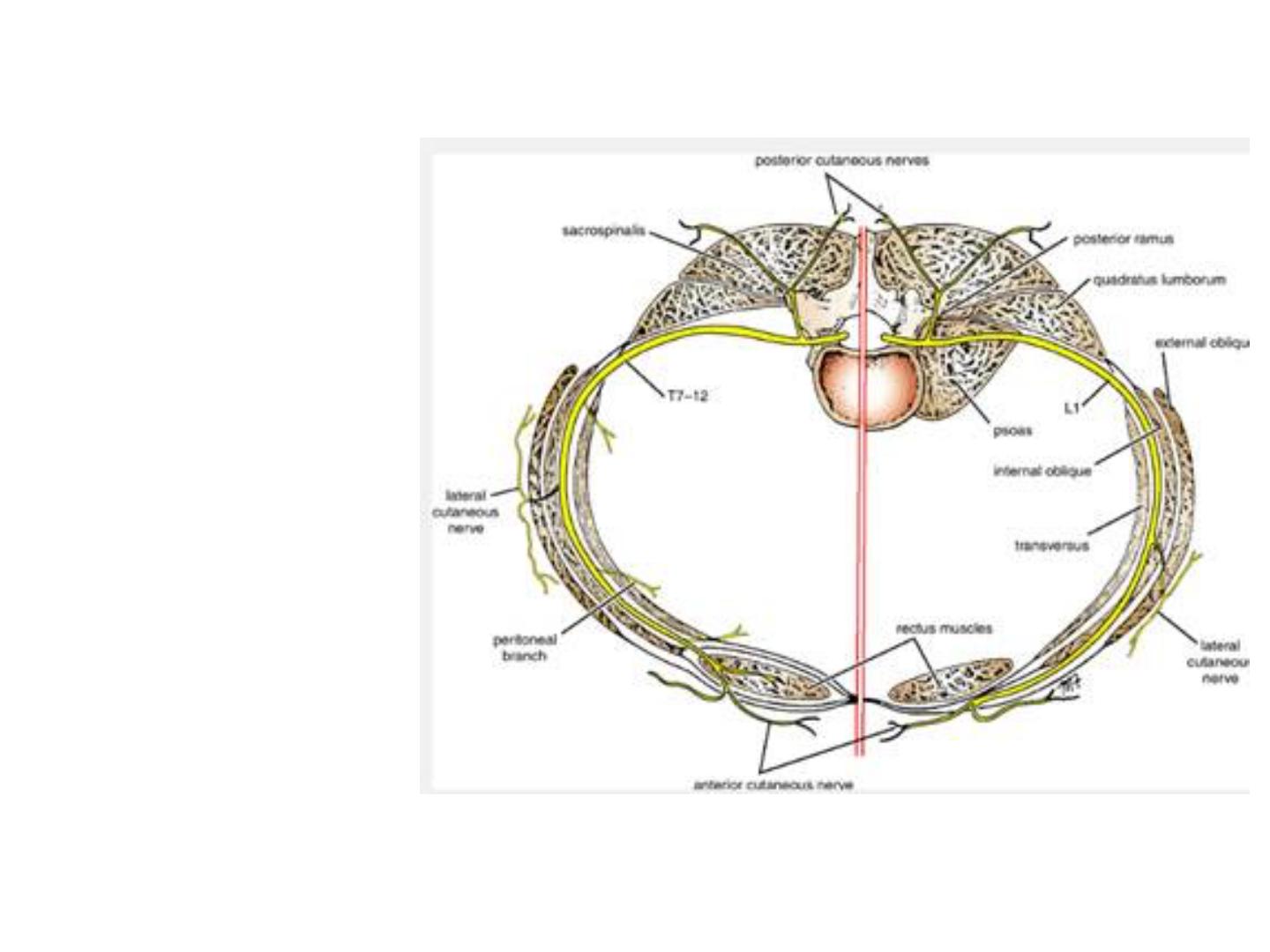

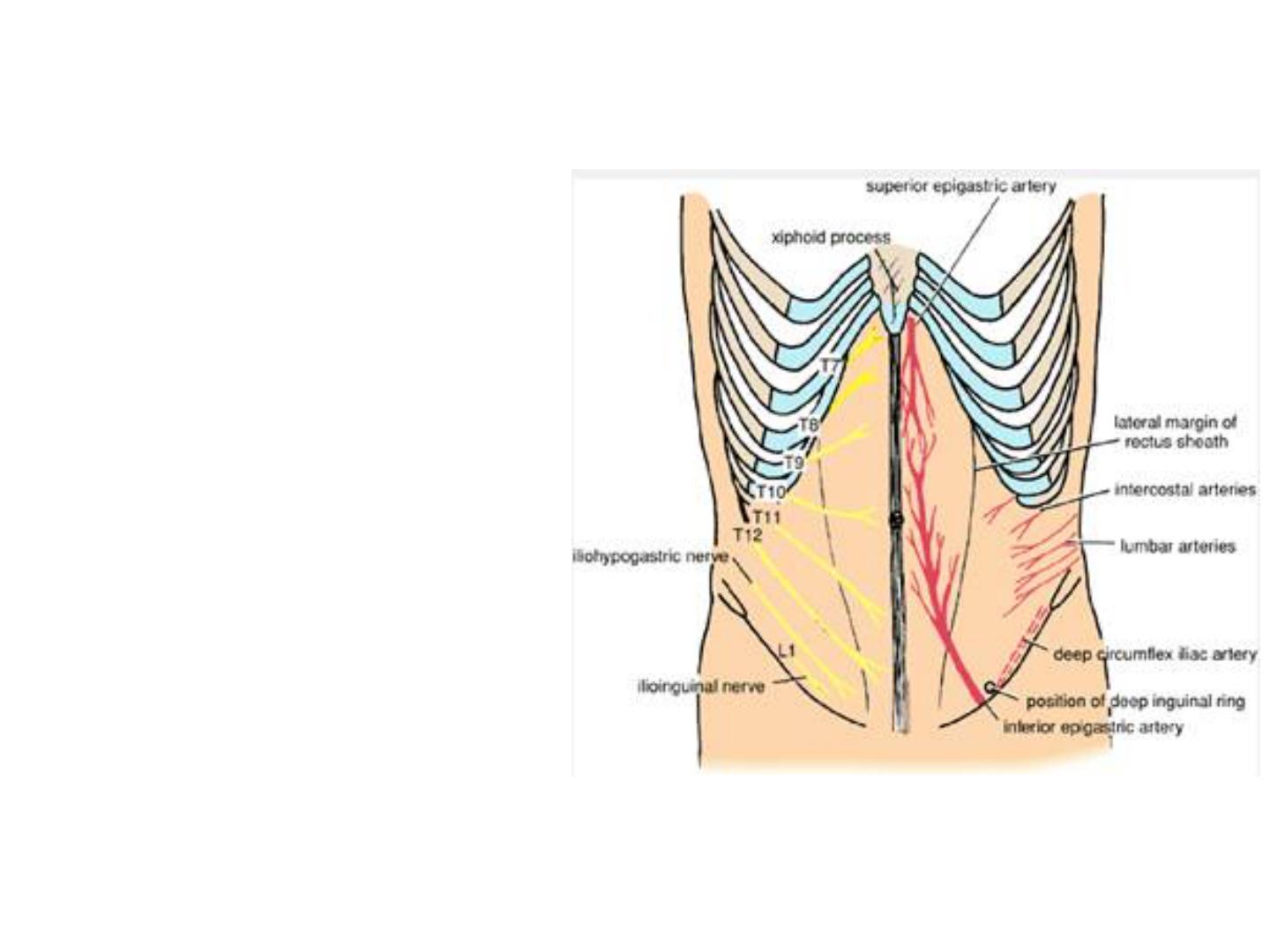

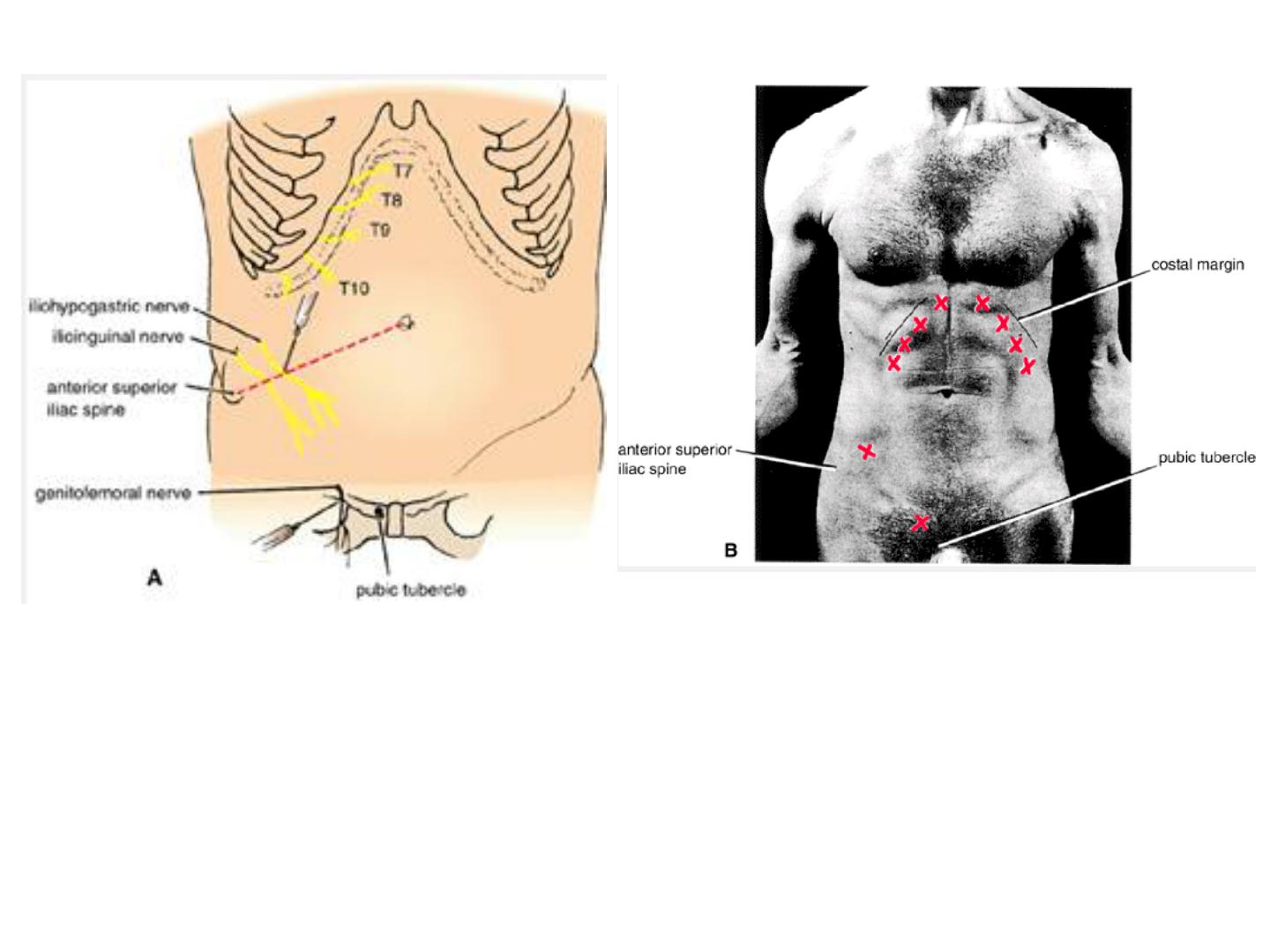

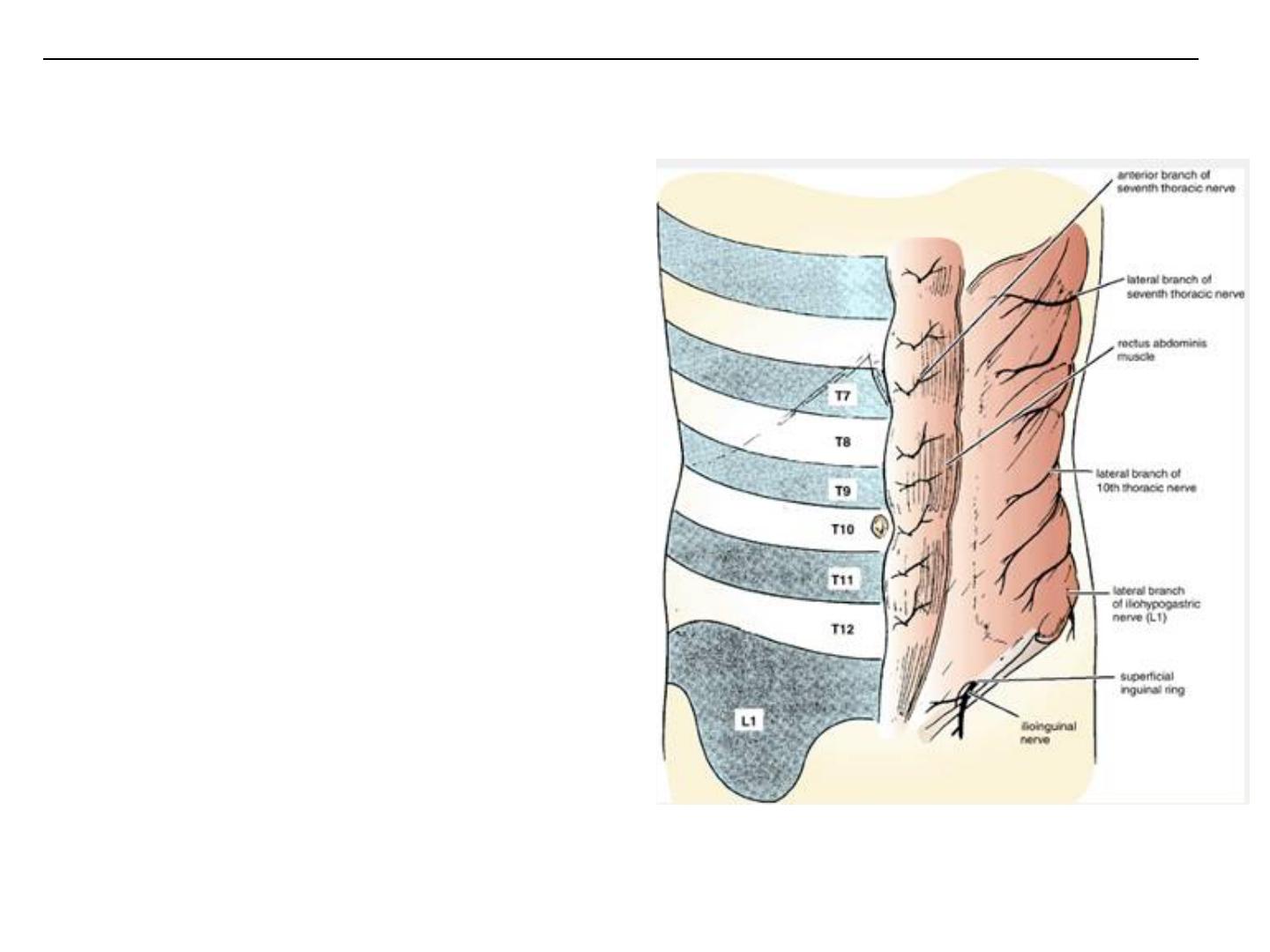

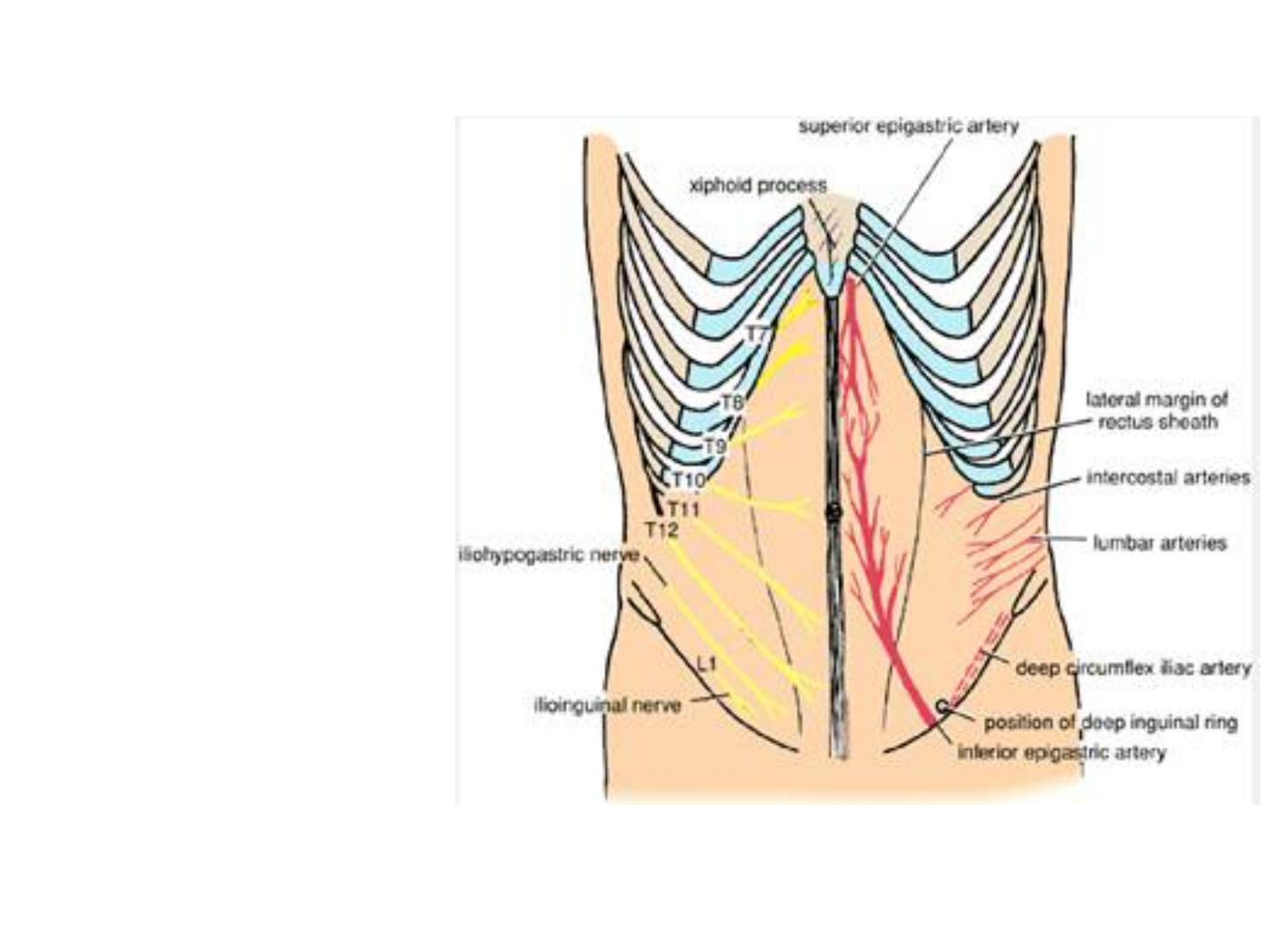

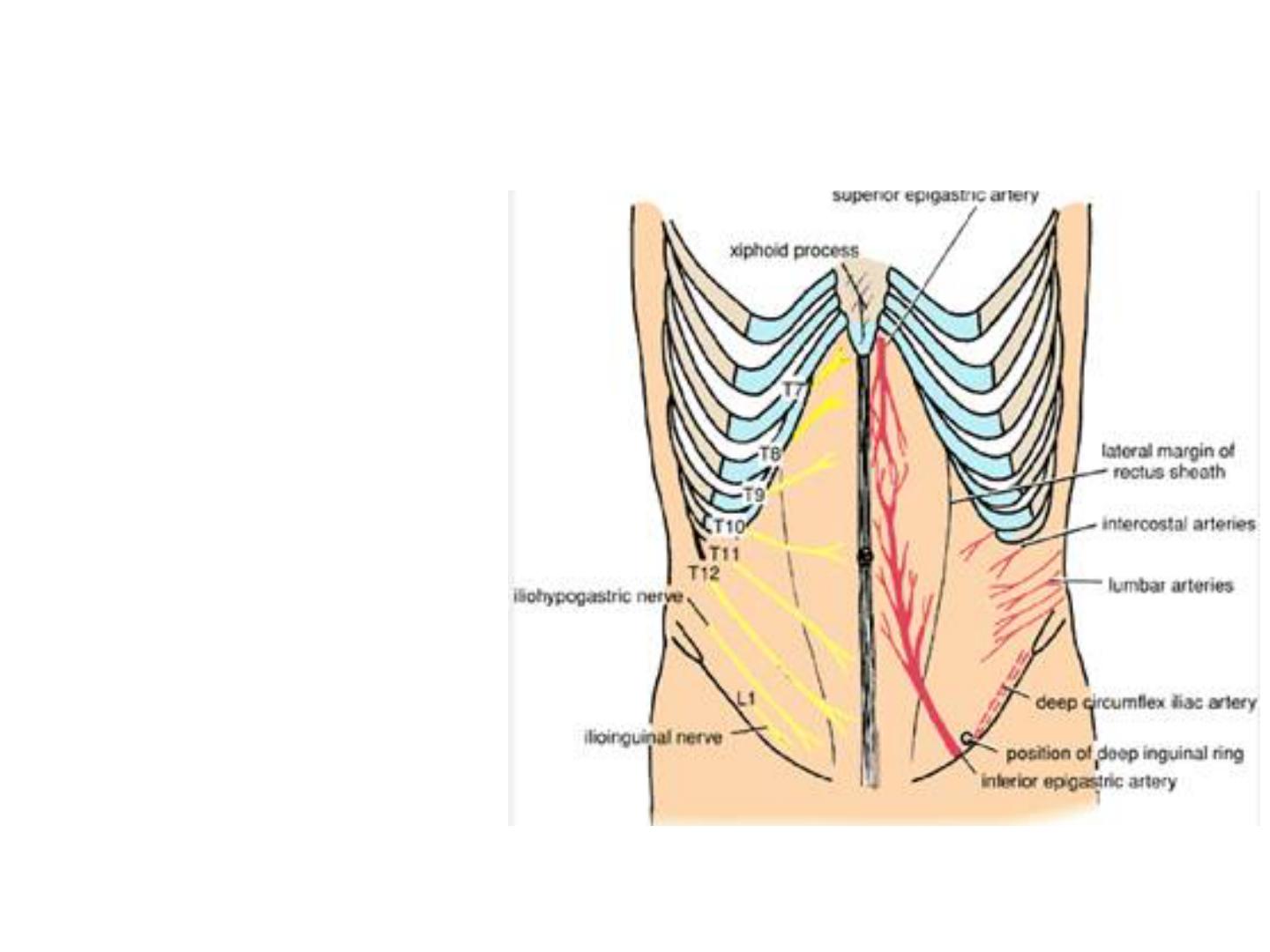

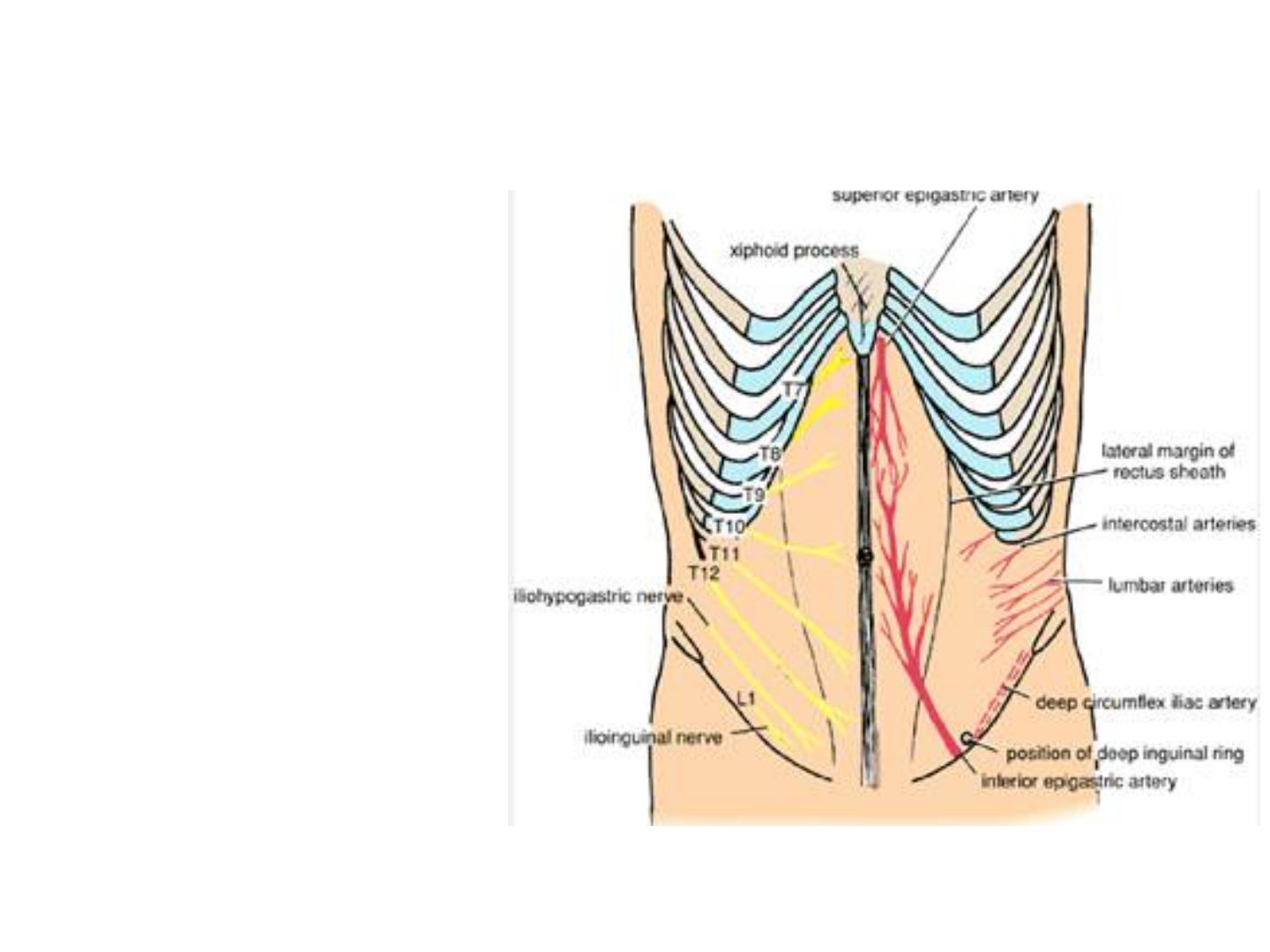

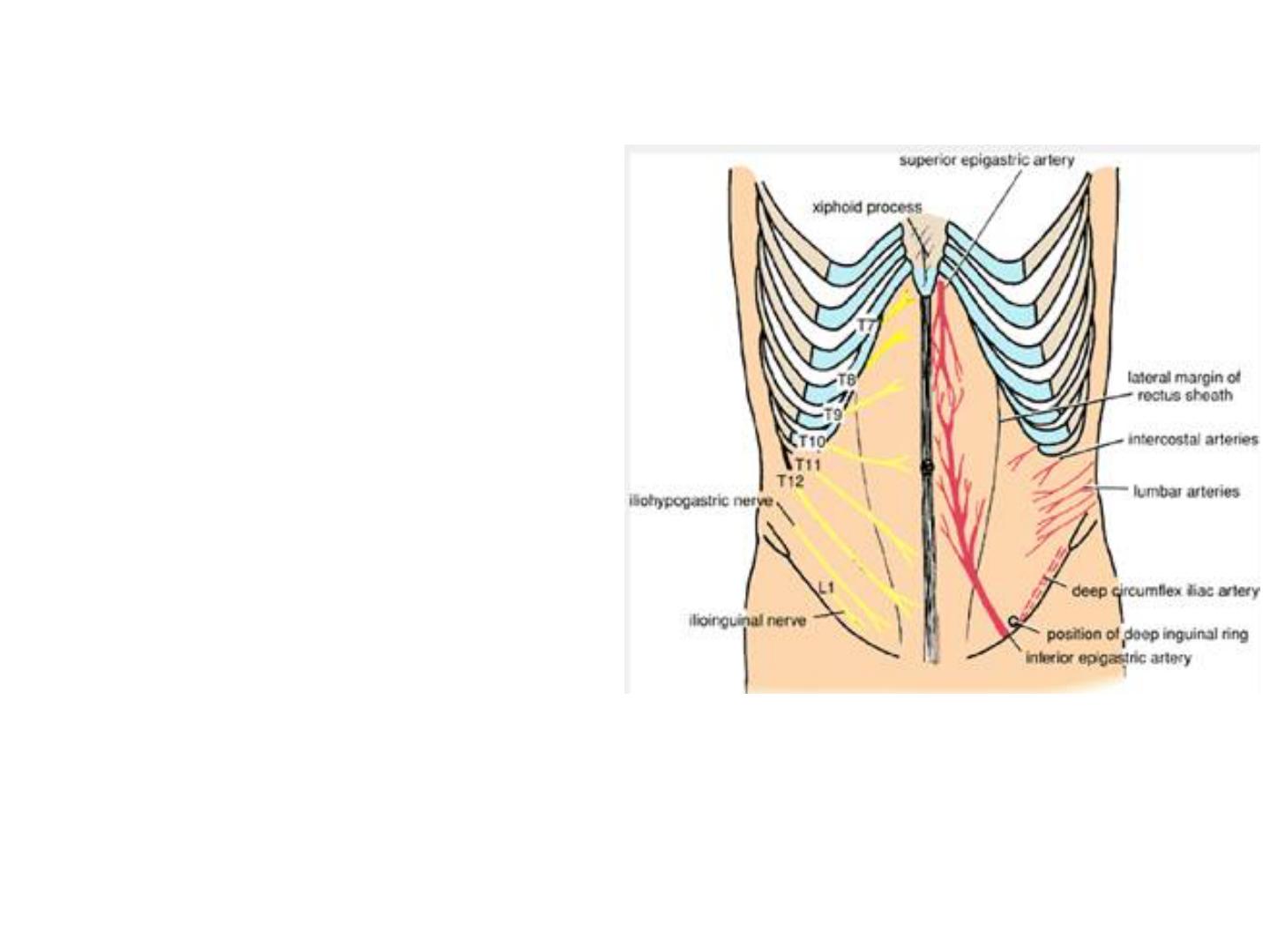

Nerve Supply

The cutaneous nerve supply to the

anterior abdominal wall is derived

from the anterior rami of the lower

six thoracic and the first lumbar

nerves .

The thoracic nerves are the lower

five intercostal and the subcostal

nerves;

the first lumbar nerve is

represented by the iliohypogastric

and the ilioinguinal nerves.

The dermatome of T7 is located in

the epigastrium over the xiphoid

process. The dermatome of T10

includes the umbilicus, and that of L1

lies just above the inguinal ligament

and the symphysis pubis.

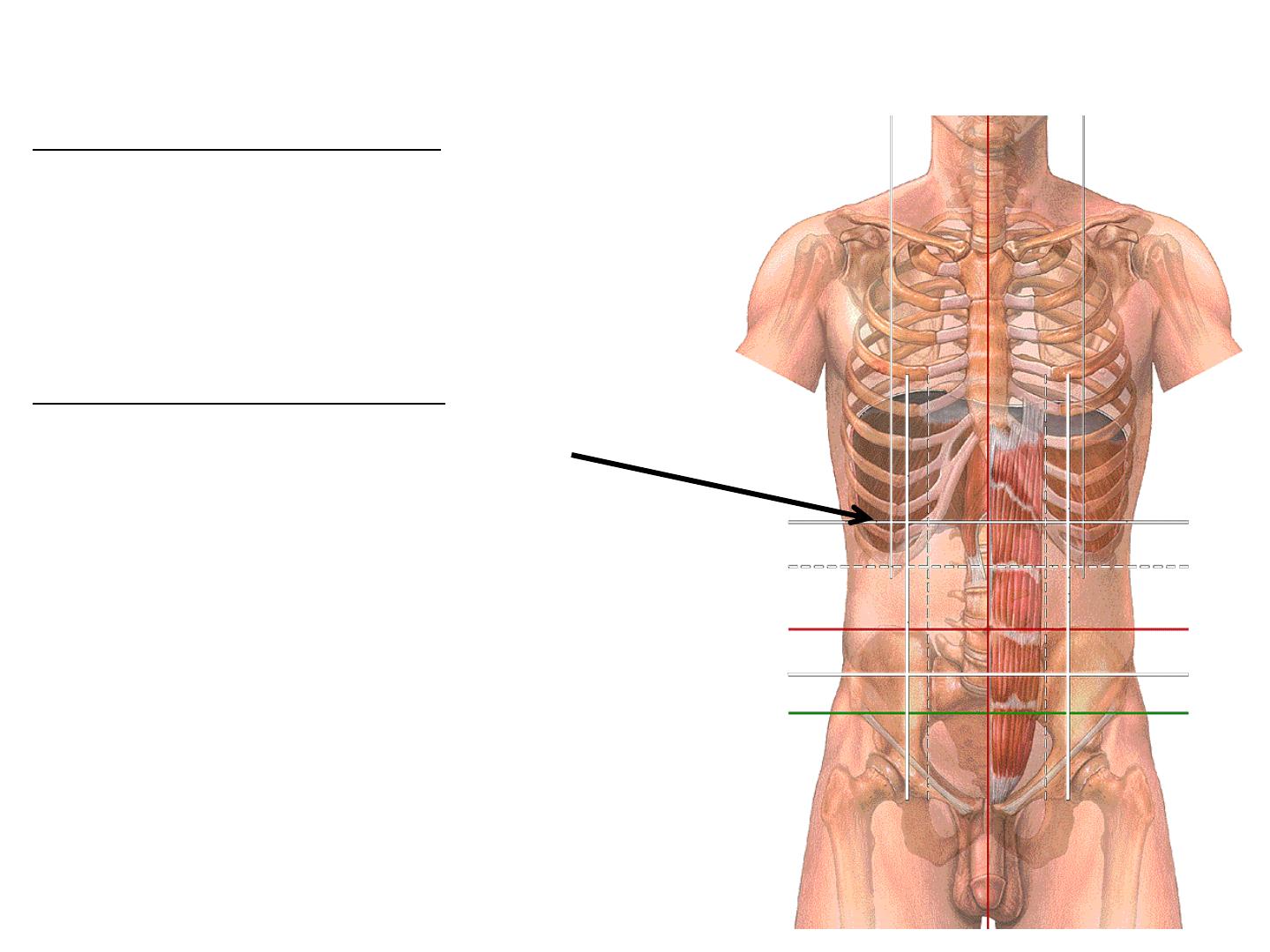

Dermatomes and distribution of

cutaneous nerves on the anterior

abdominal wall.

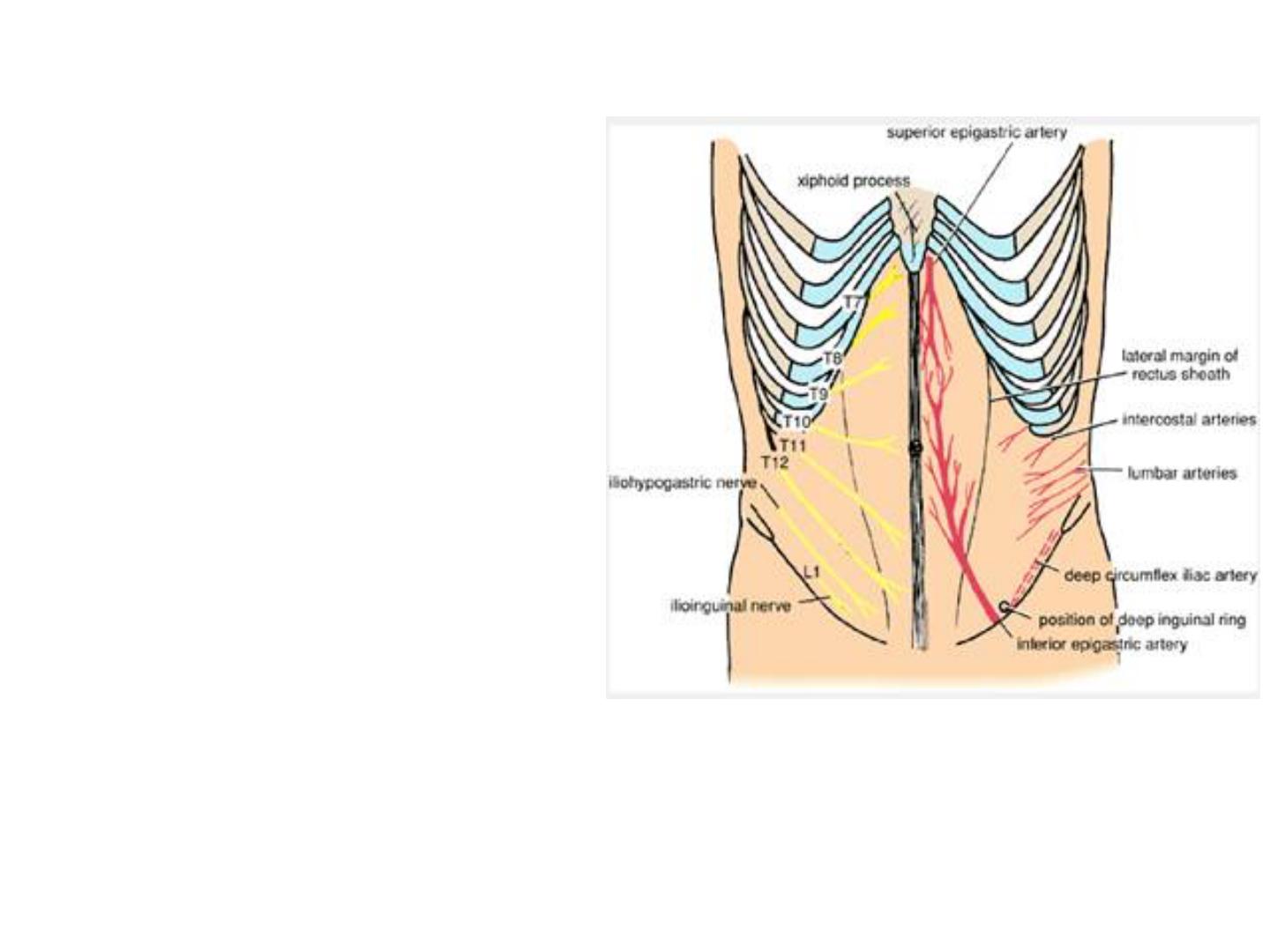

Blood Supply

Arteries

The skin near the midline is

supplied by branches of the

superior and the inferior

epigastric arteries.

The skin of the flanks is supplied

by branches of the intercostal,

the lumbar, and the deep

circumflex iliac arteries .

The skin in the inguinal region is

supplied by the superficial

epigastric, the superficial

circumflex iliac, and the

superficial external pudendal

arteries, branches of the femoral

artery.

segmental innervation of the anterior

abdominal wall (left) and arterial supply

to the anterior abdominal wall (right).

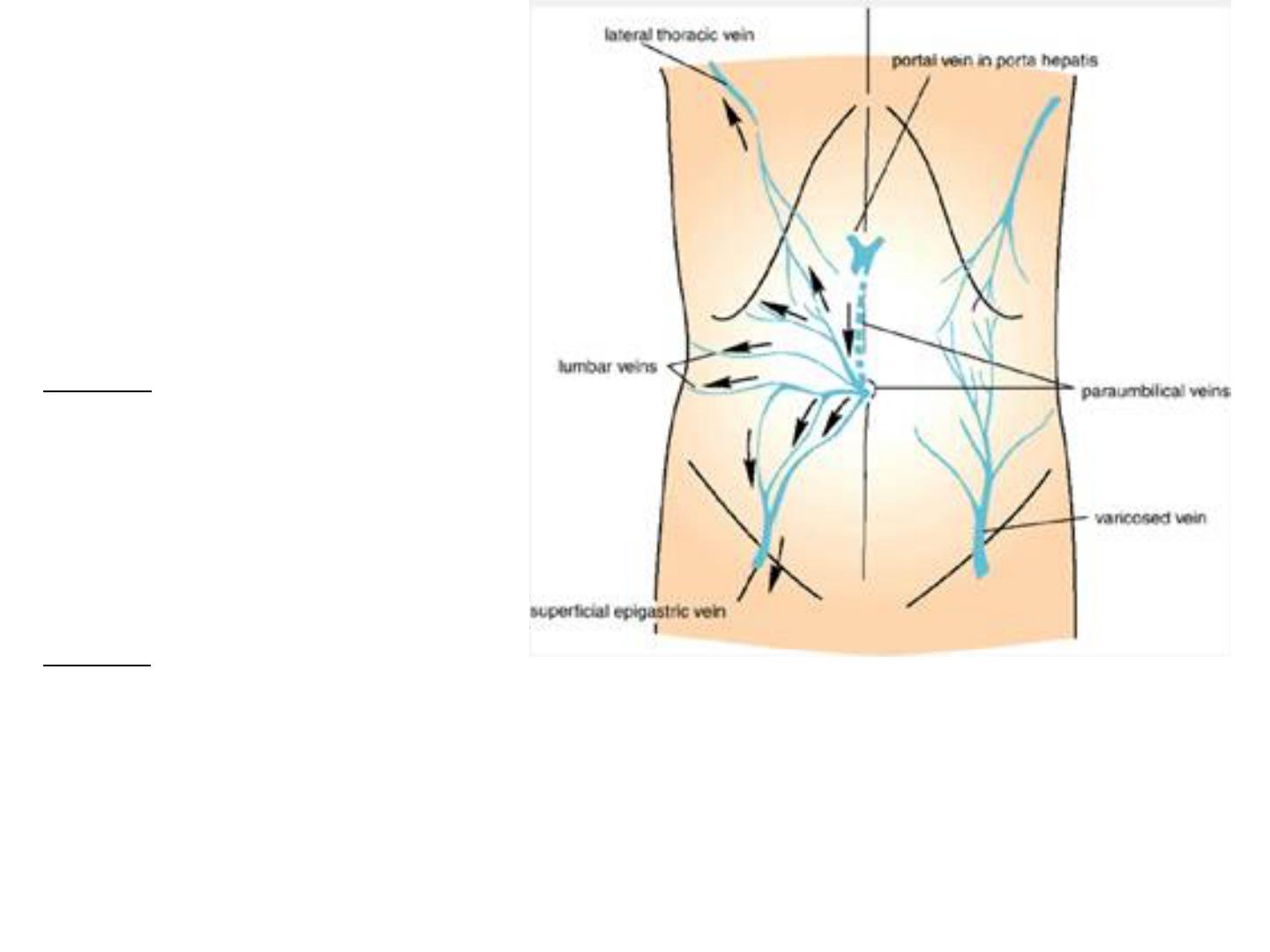

Blood Supply

Veins

The venous

drainage passes

above mainly into the

axillary vein via the

lateral thoracic vein

and

below into the femoral

vein via the superficial

epigastric and the

great saphenous veins.

On the left are anastomoses between systemic veins

and the portal vein via paraumbilical veins. Arrows

indicate the direction taken by venous blood when the

portal vein is obstructed. On the right is an enlarged

anastomosis between the lateral thoracic vein and the

superficial epigastric vein. This occurs if either the

superior or the interior vena cava is obstructed.

● Applied anatomy of the anterior abdominal wall, and surgical incision

Incisions of the Abdominal Wall

Principles

Three requirements for a proper

abdominal incision:

●accessibility

●extensibility

●security

The following rules should be

observed where they apply:

●The incision should be adequate:

long enough for good exposure and

for room to work, but short enough

to avoid unnecessary complications.

●Skin incisions should follow

Langer's lines where possible.

●Incisions parallel with existing

scars should be avoided.

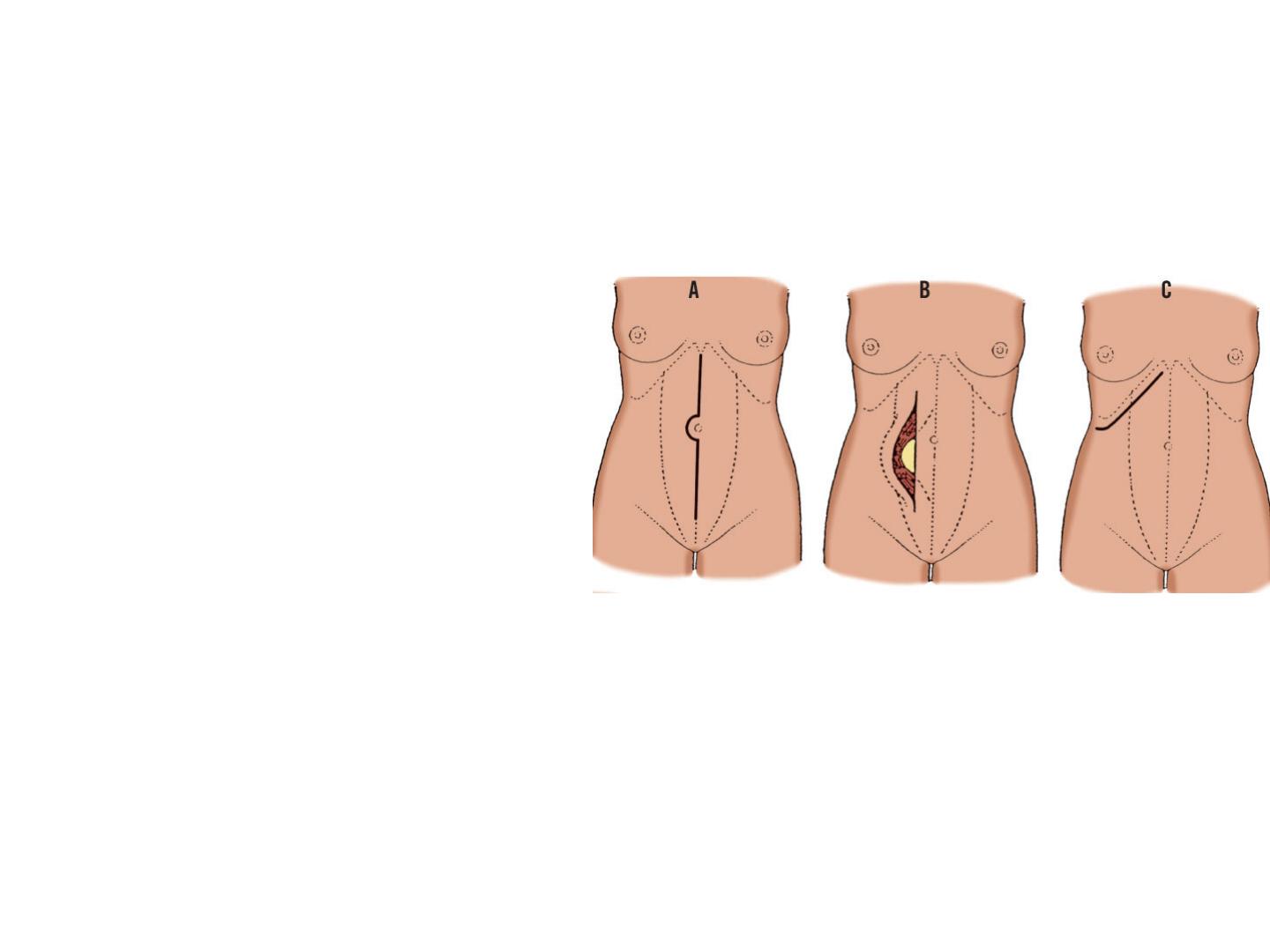

A, Midline (linea alba) incision. B,

Paramedian (rectus) incision with muscle

retraction. C, Subcostal incision.

●Muscles should be split

in the direction of their

fibers rather than

transected. An exception

is the rectus muscle,

which may be transected

because it has a

segmental nerve supply.

There is no risk of

denervation.

●The openings formed

through the different

layers of the abdominal

wall should not be

superimposed.

●Cutting of nerves should

be avoided wherever

possible.

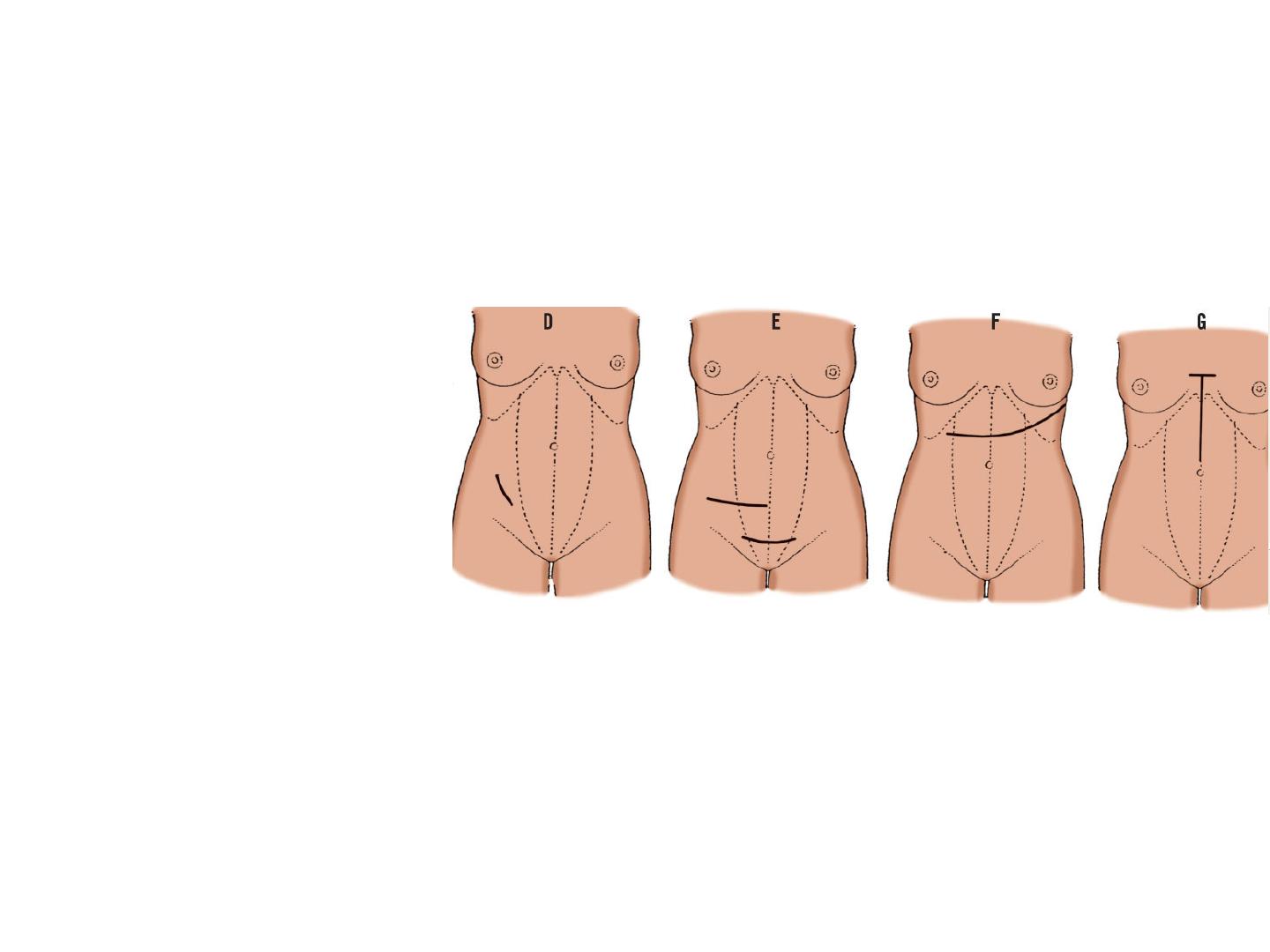

D, McBurney incision. E, Transverse abdominal

incision. F and G, Two types of thoracoabdominal

incisions.

●Muscles and

abdominal organs

should be retracted

toward, not away

from, their

neurovascular supply.

●Drainage tubes

should be inserted in

separate small

incisions, not in the

main incision. They

may weaken the

wound.

●Cosmetic

considerations must

be given close

attention.

H, Paramedian (rectus) incision with muscle

splitting. I, Pararectus incision. J, "Hockey

stick" (thoracoabdominal) incision.

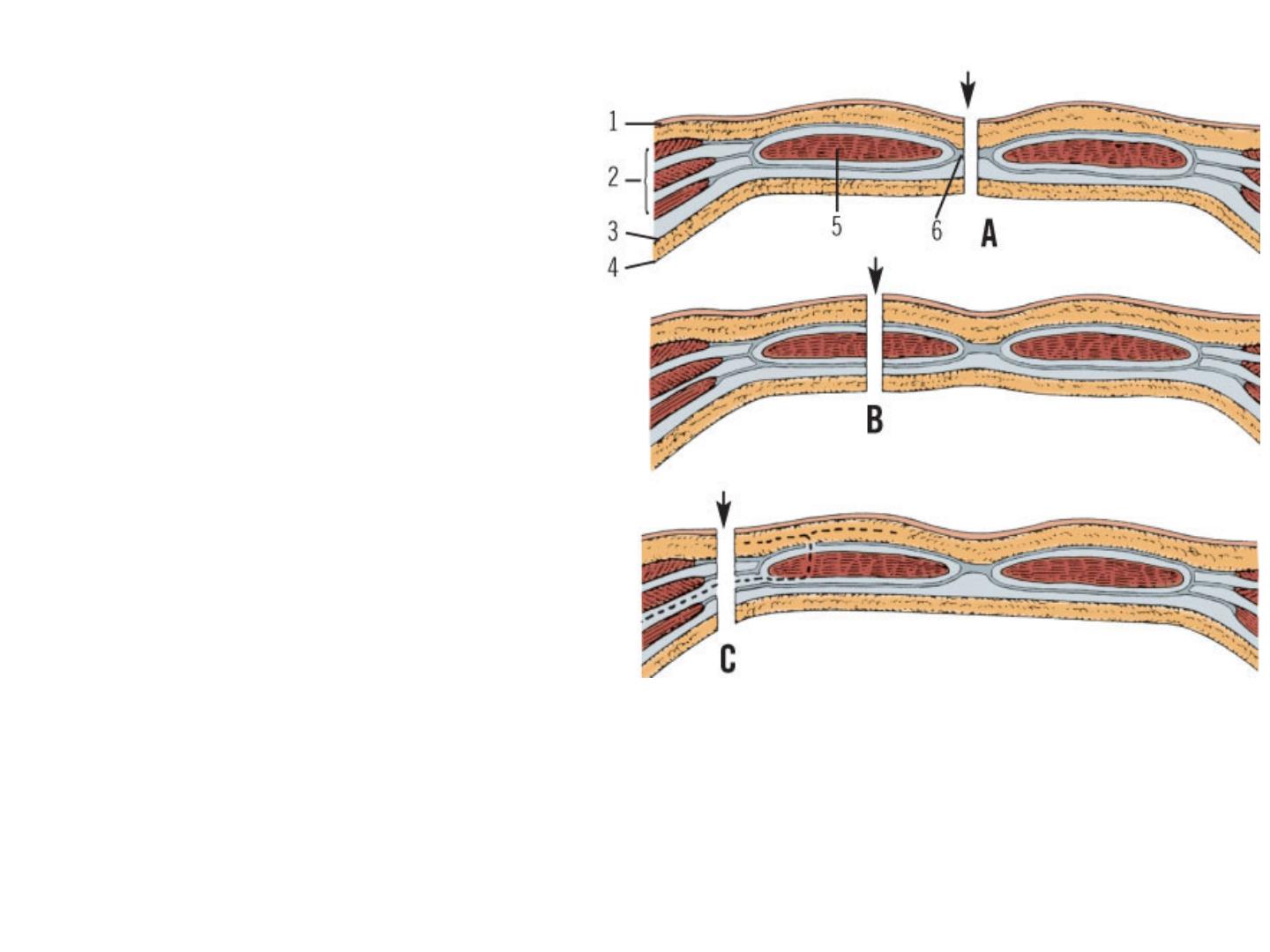

Vertical

Incisions

Upper midline incisions

of the linea alba and the

transversalis fascia may

reveal abundant and

well-vascularized fat in

the upper midline. We

suggest that incisions of

the peritoneum be made

slightly to the left of the

midline to avoid the

ligamentum teres in the

edge of the falciform

ligament. If the

ligamentum teres is

encountered, it may be

ligated and divided.

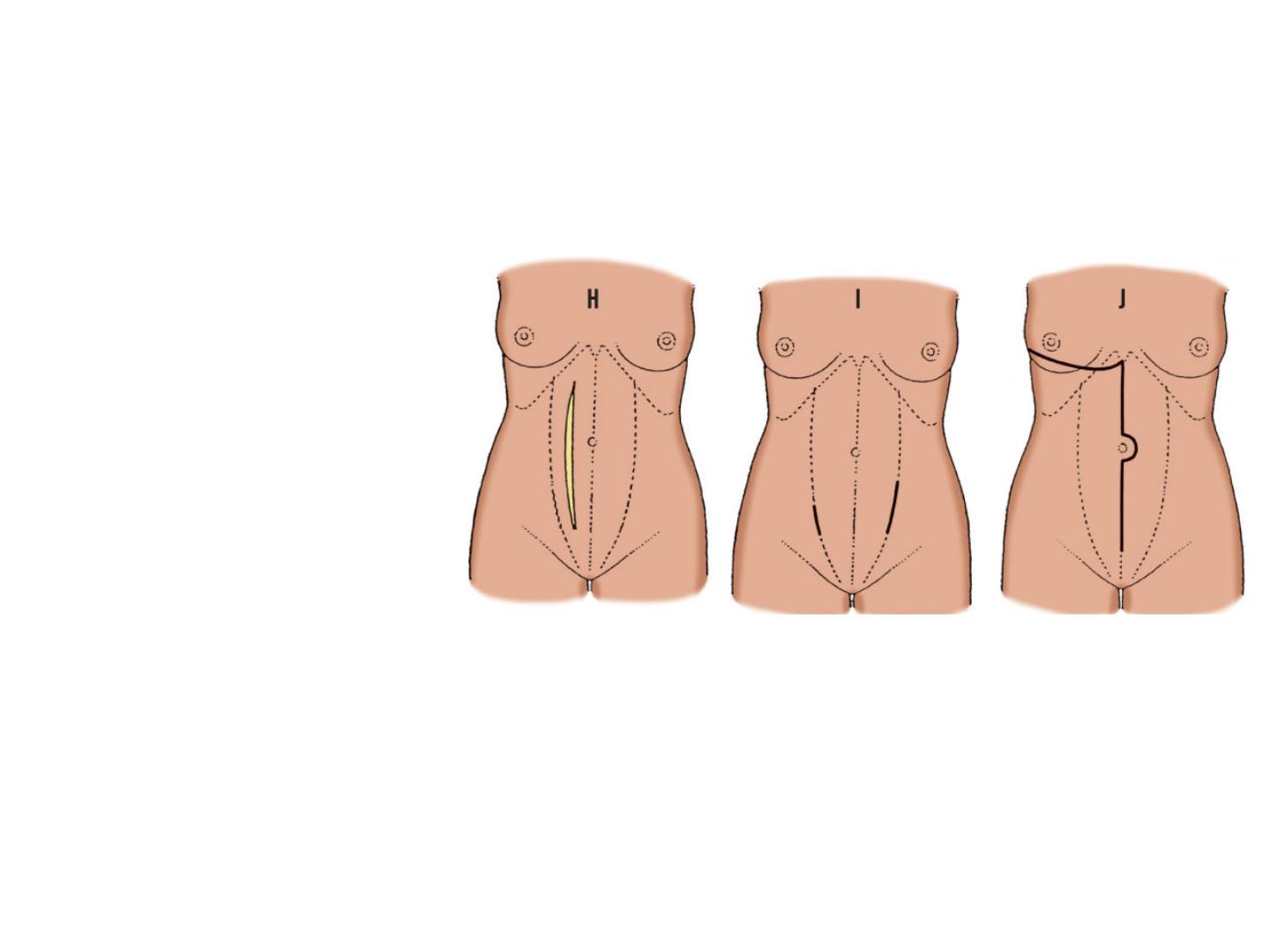

Vertical incisions. A, Incision through linea alba. B,

Incision through rectus muscle (paramedian), splitting

muscle. C, Incision lateral to rectus sheath (pararectus).

Segmental nerves to rectus muscle (dashed line) will be

cut. 1, Skin; 2, Three flat muscles and their aponeuroses;

3, Transversalis fascia; 4, Peritoneum; 5, Rectus

abdominis muscle; 6, Linea alba.

Upper Midline Incision

An upper midline

incision can be enlarged

upward by removal of the

xiphoid process and

upward extension of the

peritoneal opening.to

provide access to the

upper margin of the liver,

vena cava, and hepatic

veins, as well as the

gastroesophageal

junction.

A downward

continuation of an upper

midline incision is

always an available

option.

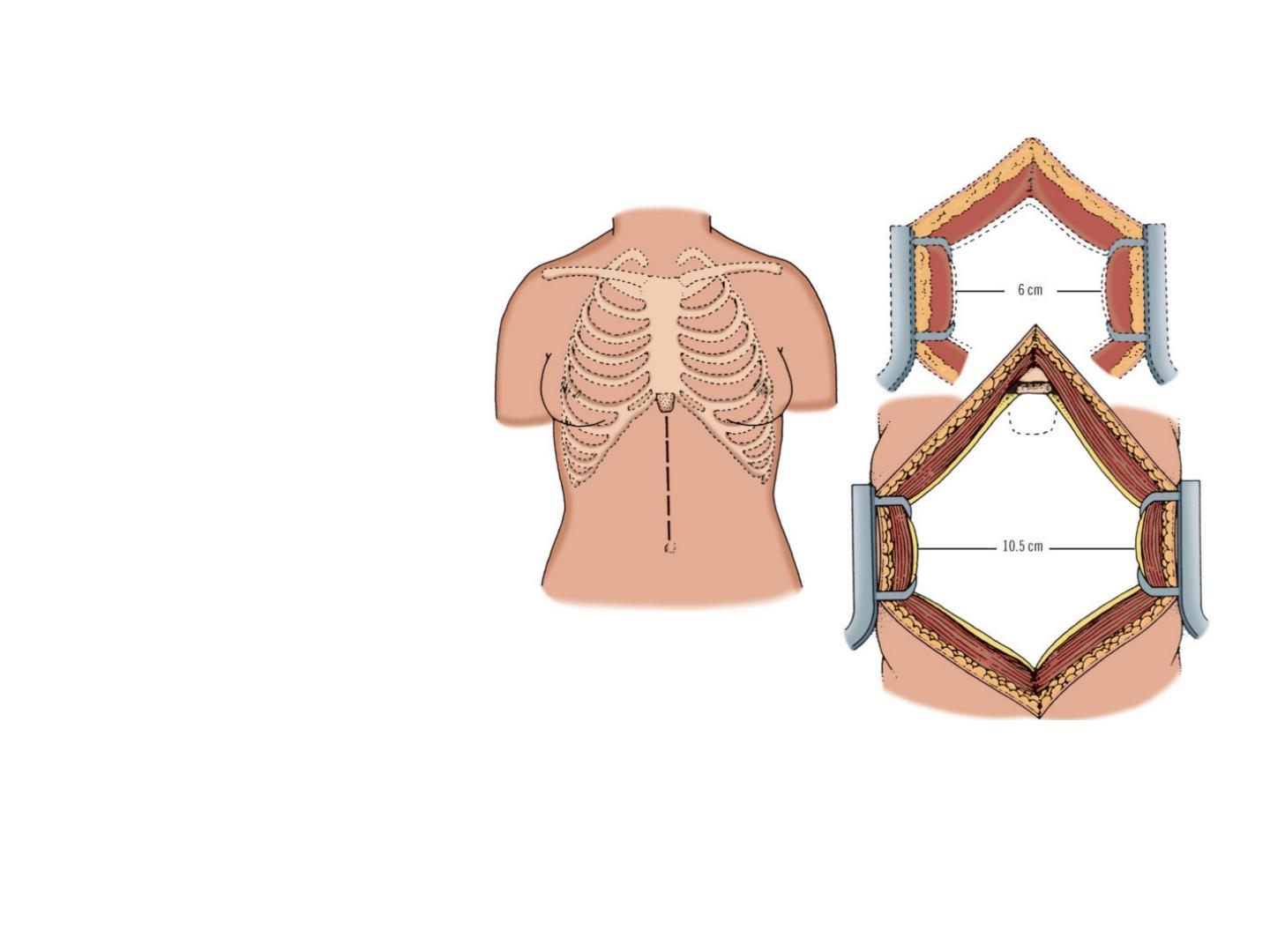

Increased abdominal exposure by excision of xiphoid

process. Left, Upper midline abdominal incision.

Right, Usual exposure of about 6 cm (broken lines),

and 10-11 cm exposure obtained after excision of

xiphoid process (solid lines).

Feasible extensions include the following:

Lower Midline Incision

The linea alba is

narrow and more difficult

to identify below.

Remember that the

bladder must always be

decompressed by

catheterization prior to

surgery.

Rectus (Paramedian)

Incision

It does not destroy muscle

tissue or nerves. The

rectus muscle should be

retracted laterally to

prevent tension on vessels

and nerves.

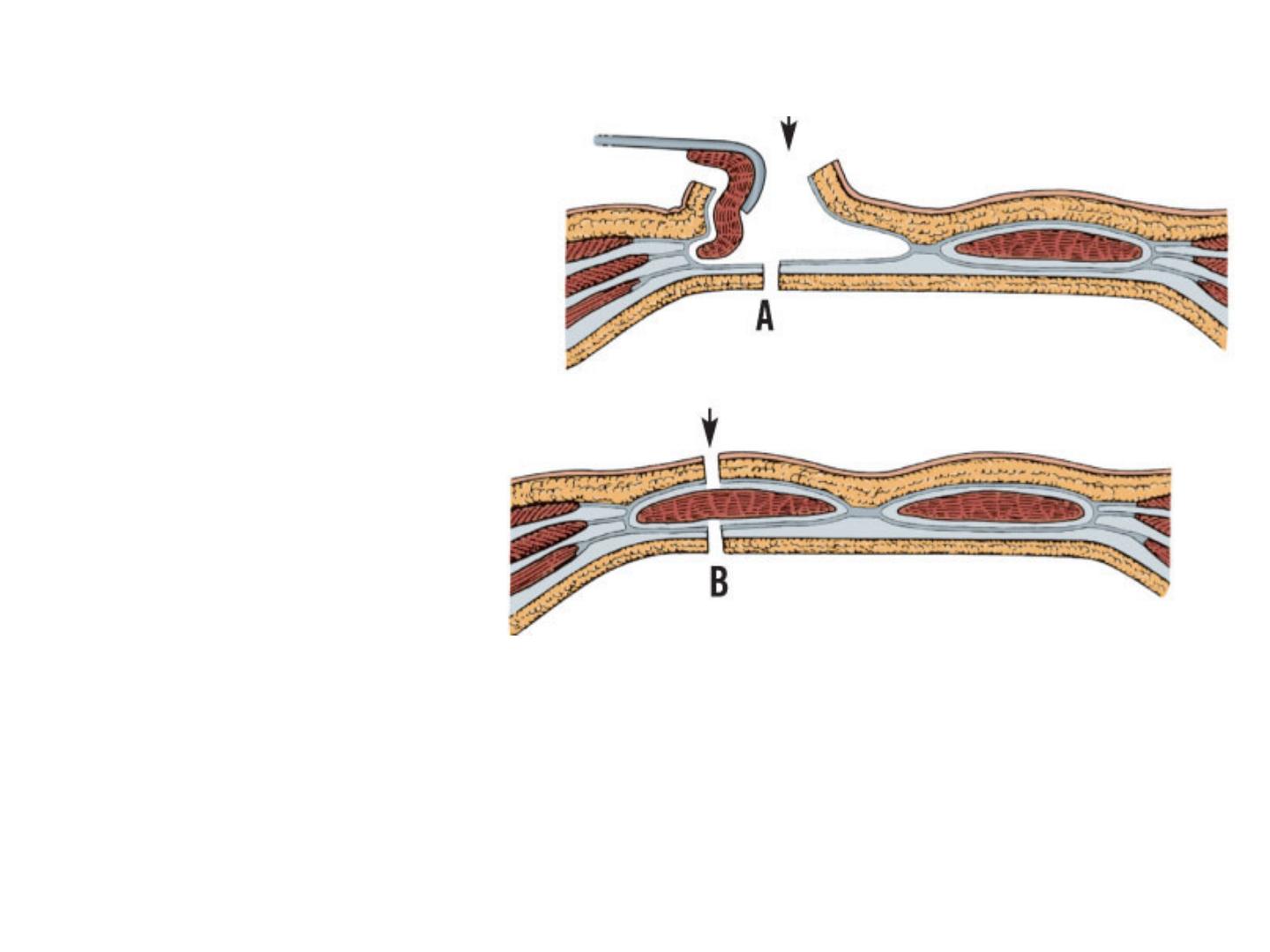

Incision through the rectus sheath without muscle

splitting. A, Lateral retraction of rectus muscle

following incision of anterior layer of sheath. B,

Release of traction allows intact muscle to bridge

incision through sheath

Transverse Incisions

In transverse incision, both

the rectus sheath and

muscle are incised.

Upper Abdominal

Transverse Incision

The rectus muscle is

transected during an upper

abdominal transverse

incision.

Lower Abdominal

Transverse Incision

Both rectus abdominis

muscles are incised, and

perhaps also right or left

flat muscles.

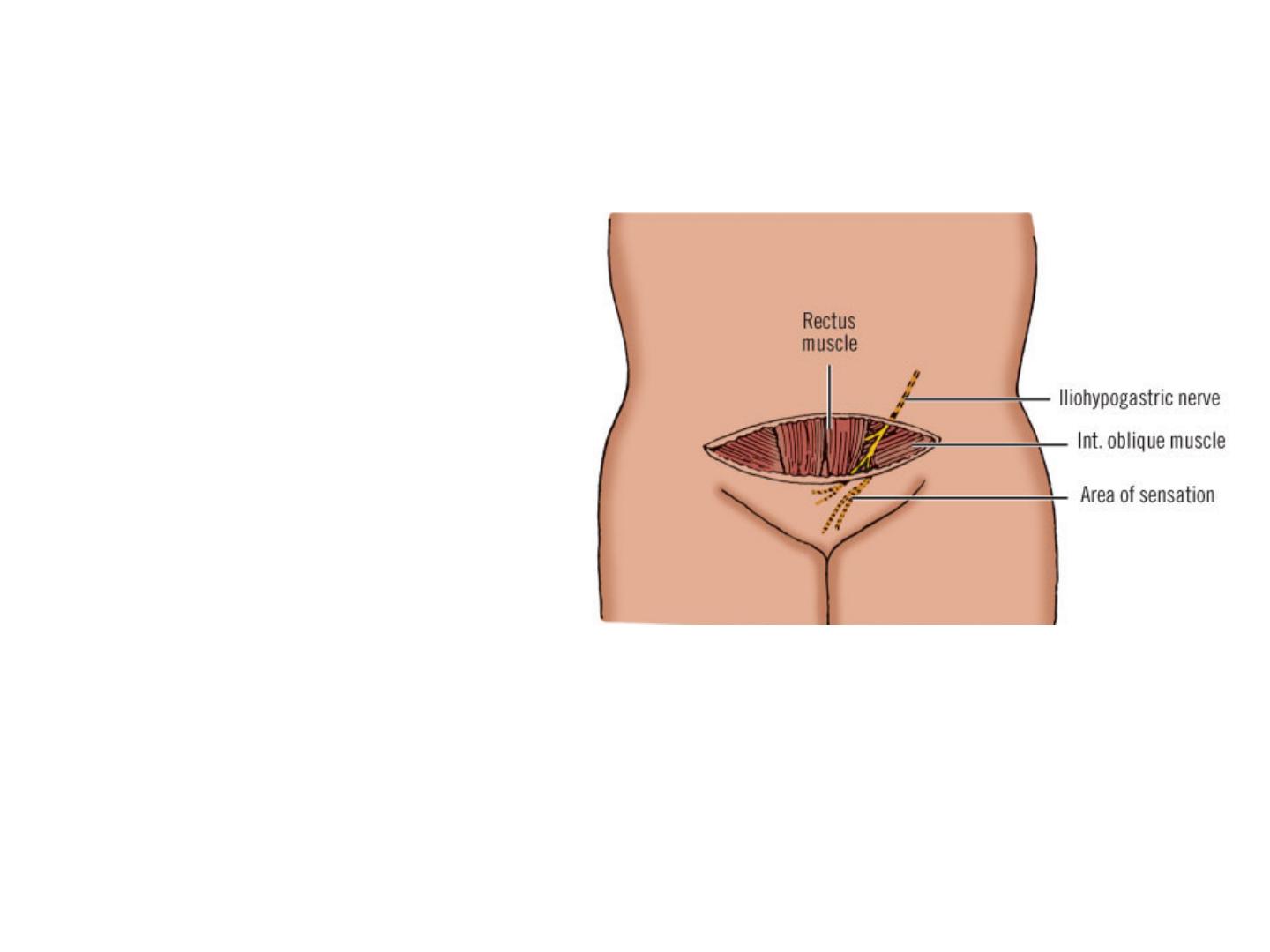

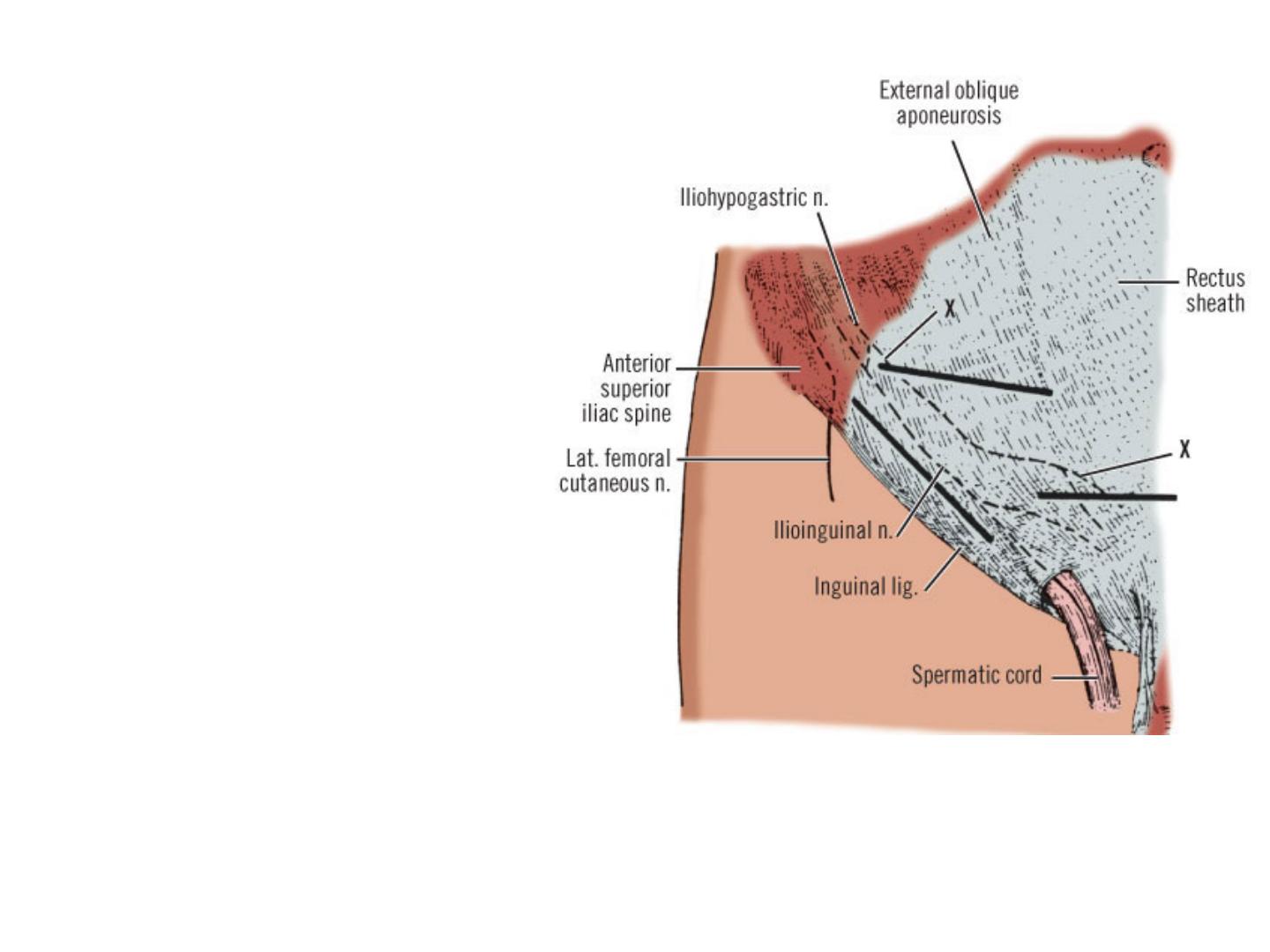

Pfannenstiel transverse abdominal incision

showing iliohypogastric nerve between internal

oblique muscle and external oblique

aponeurosis just lateral to border of rectus

muscle

Pfannenstiel Incision

The Pfannenstiel

transverse abdominal

incision is made

horizontally just above

the pubis. The

iliohypogastric nerve

must be identified and

protected.

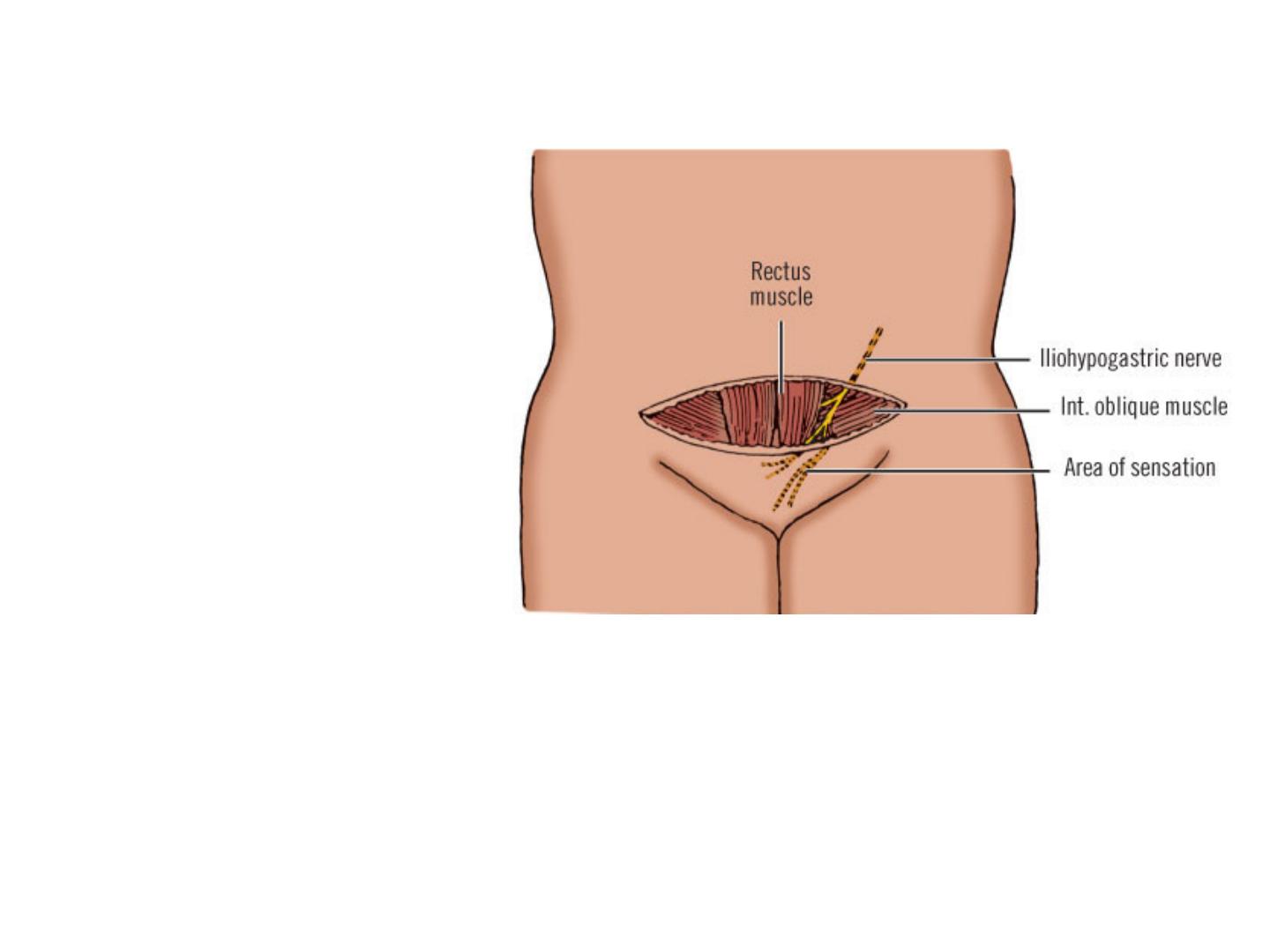

Pfannenstiel transverse abdominal incision

showing iliohypogastric nerve between internal

oblique muscle and external oblique aponeurosis

just lateral to border of rectus muscle.

Oblique Incisions

Subcostal Incision

The incision should extend

laterally no farther than necessary

in order to avoid cutting

intercostal nerves.

McBurney (Gridiron) Incision

The McBurney (gridiron)

incision starting 4 cm medial to

the right anterosuperior spine and

extending downward on a line

from the spine to the umbilicus.

The iliohypogastric nerve, deep to

the internal oblique muscle, must

be identified and preserved.

Right or Left Lateral Oblique

(Kocher)

This is an oblique incision from

the tip of the right or left 10th rib

to the pubic crest.

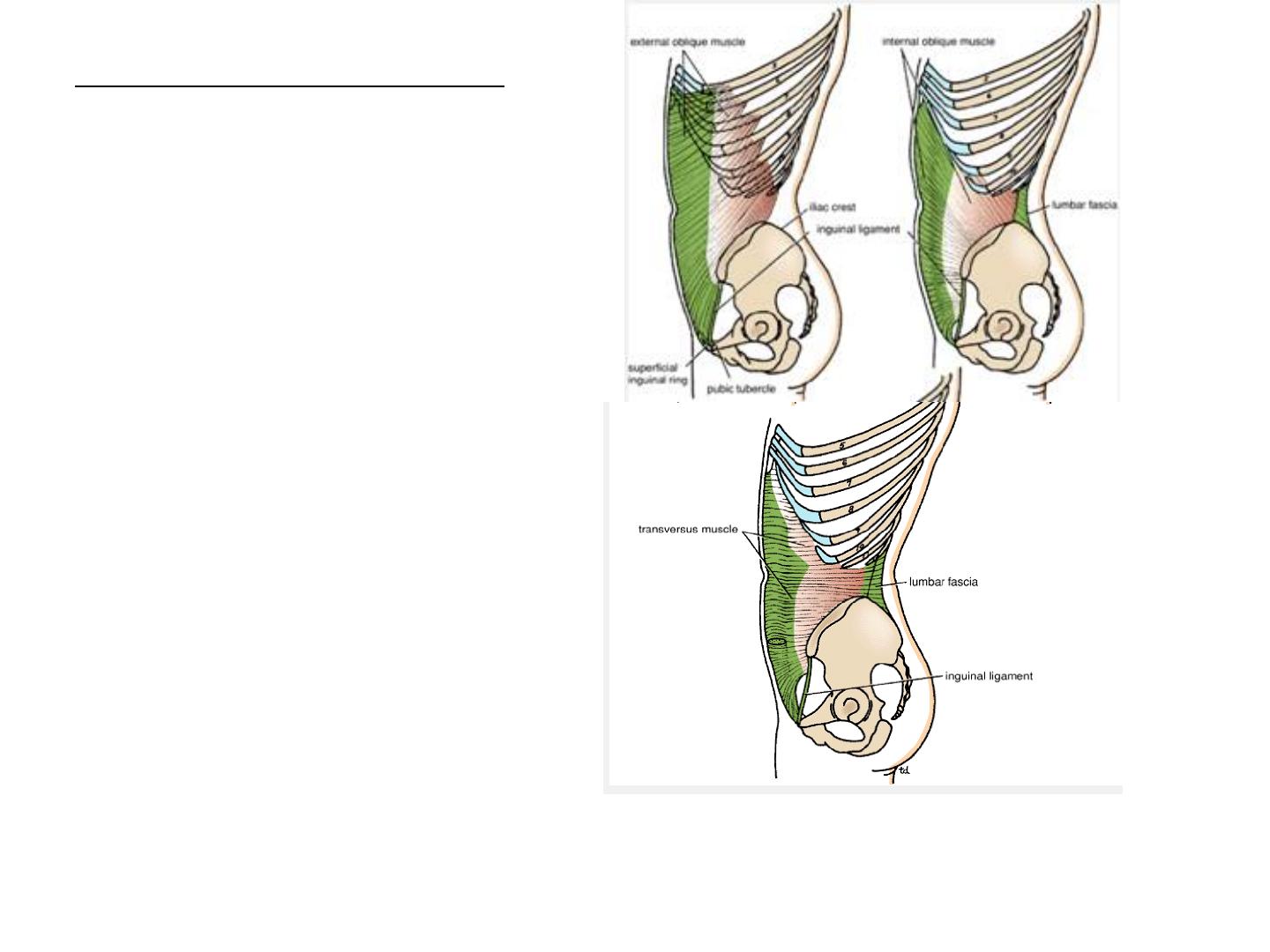

Courses of the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal

nerves.

Oblique Incision

The oblique incision

is the one most

frequently used by

urologists.

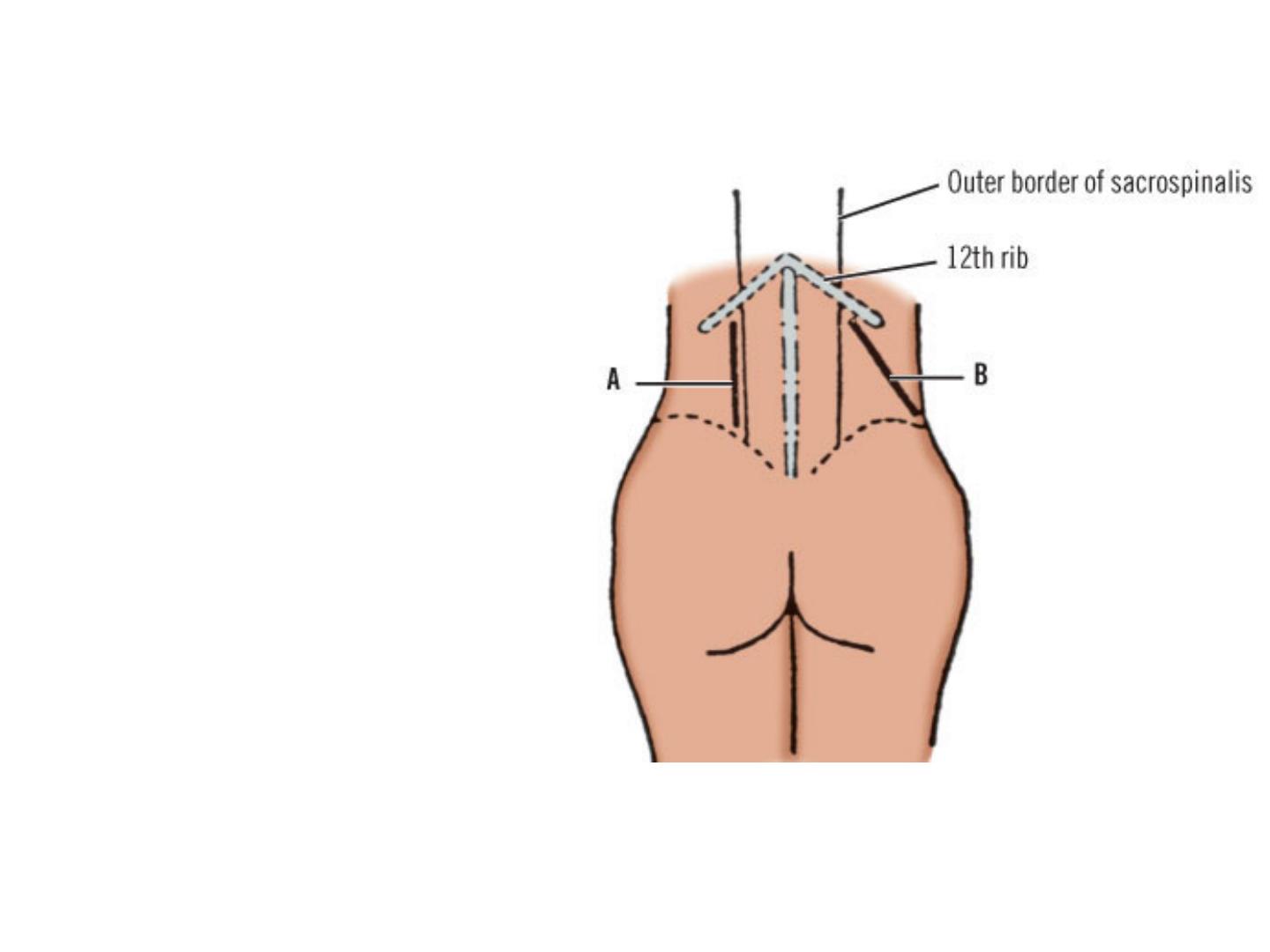

Posterior approaches to kidney. A, Vertical

incision. B, Oblique incision.

•Incisions of the Posterior (Lumbar) Abdominal Wall

Vertical Incision

The vertical incision

proceeds along the

lateral border of the

sacrospinalis from the

12th rib to the iliac

crest in a

perpendicular

orientation.

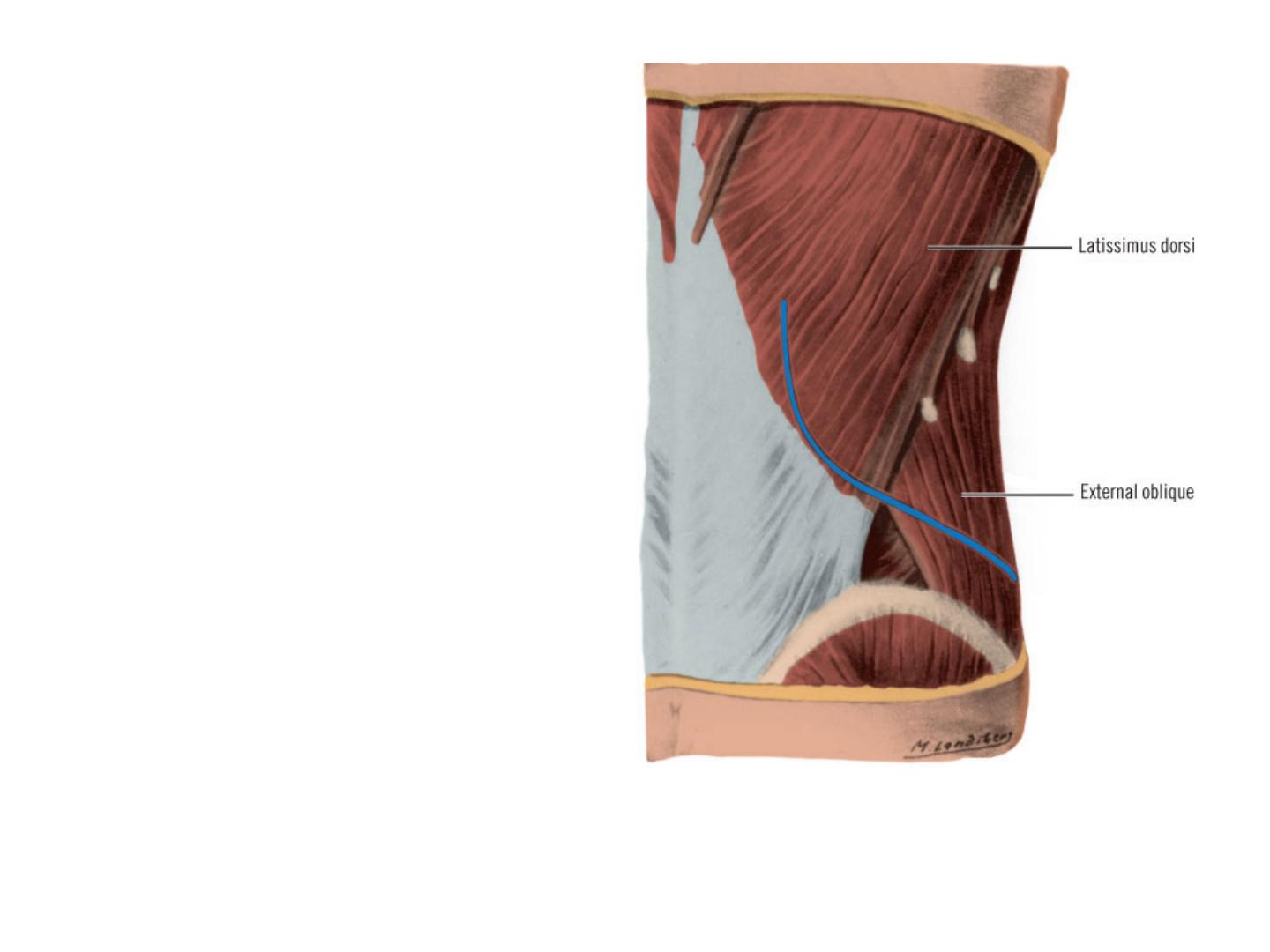

First layer of muscles to divide in lumbar

approach to kidney. Incision shown in blue.

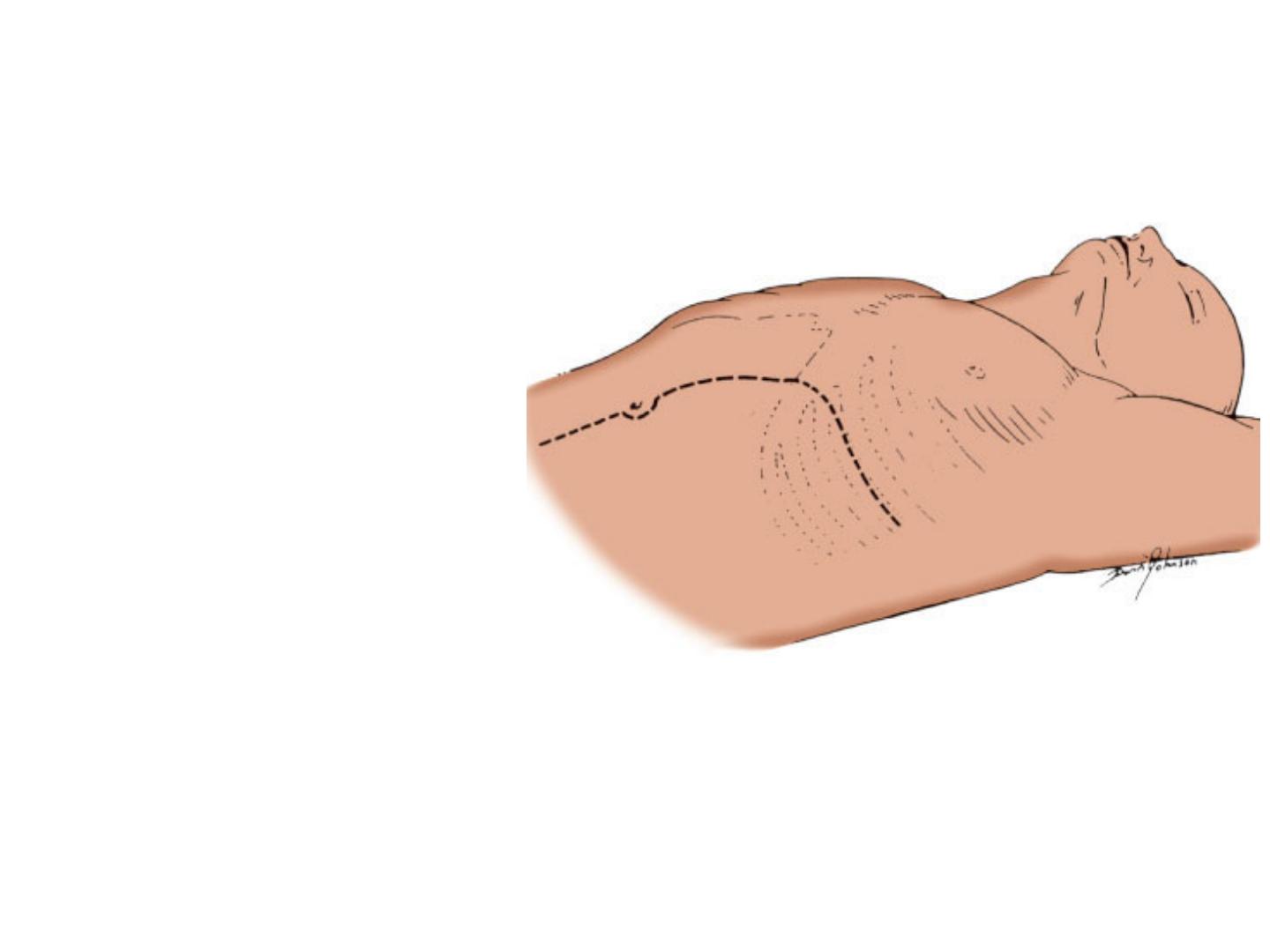

Thoracoabdominal

Incisions

In the more commonly

used left thoracoabdominal

approach, the incision

extends from a point on the

posterior axillary line near

the inferior angle of the

scapula and runs in the

seventh or eighth

intercostal space. It then

crosses the costal margin

and rectus muscle

obliquely in a line toward

the umbilicus. The incision

then continues down the

linea alba toward the pubis.

Seventh or eighth intercostal space incision

crosses costal margin obliquely and extends

down midline to the pubis.

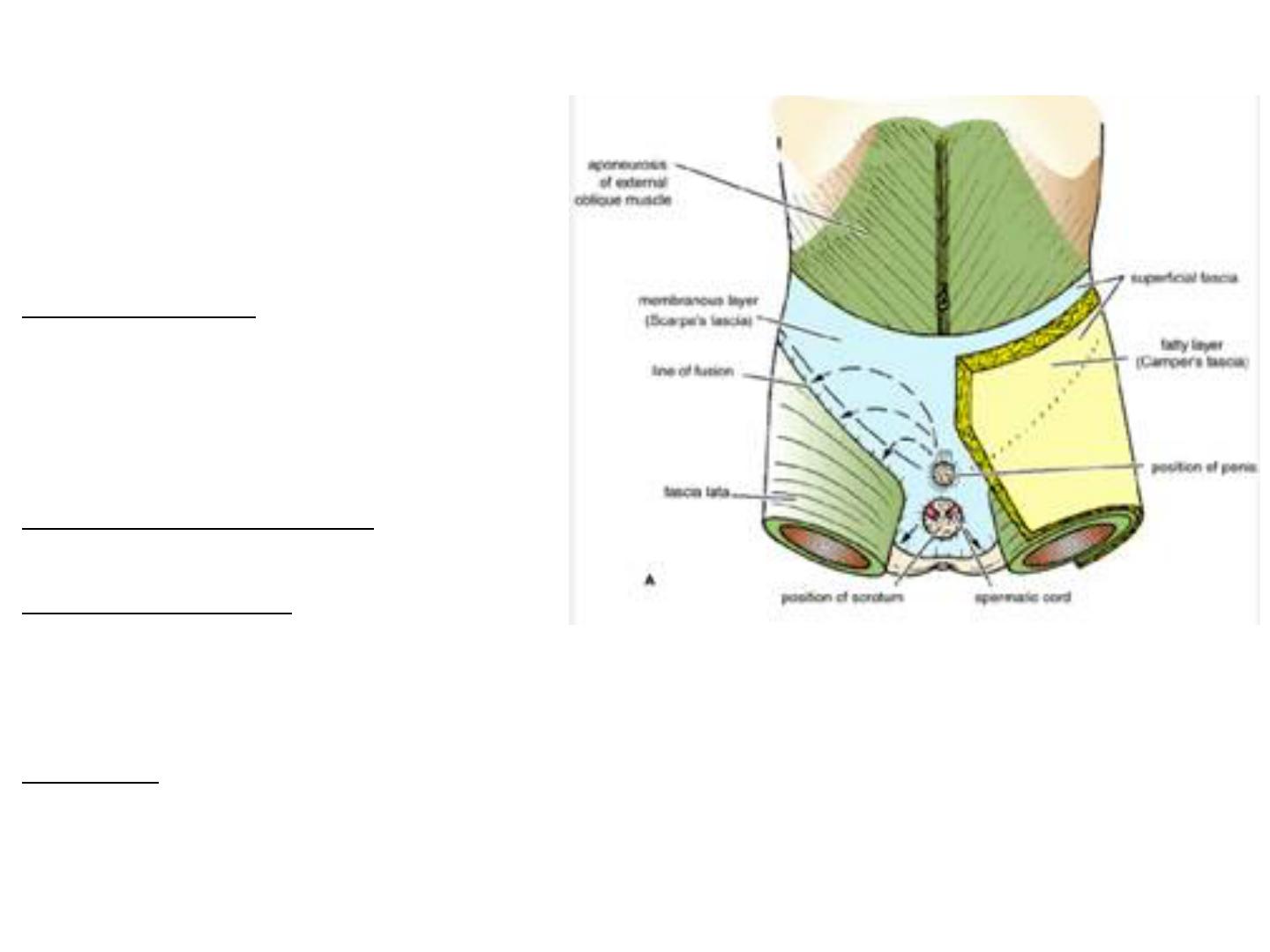

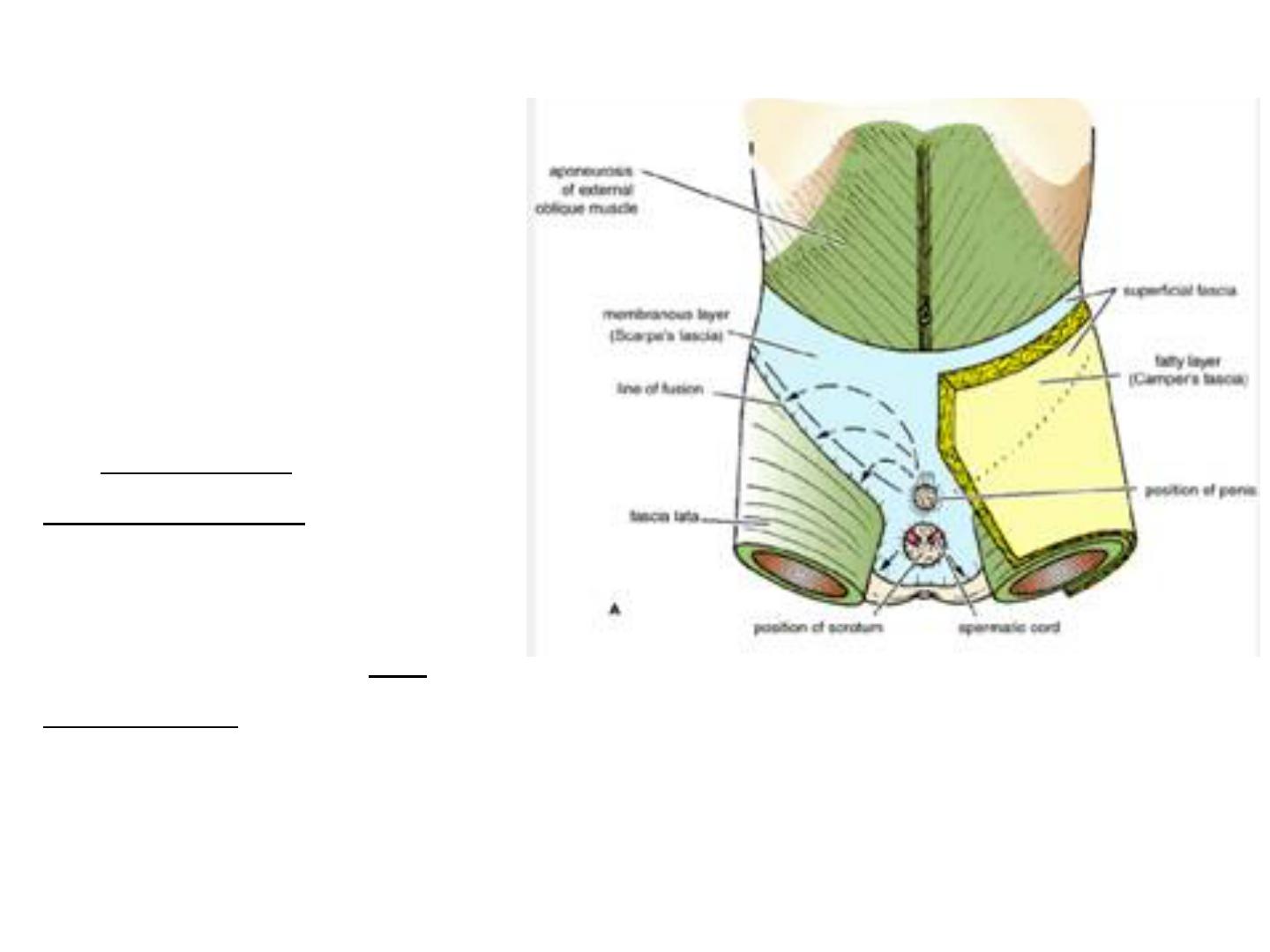

Superficial Fascia

The superficial fascia is divided

into a superficial fatty layer

(fascia of Camper) and a deep

membranous layer (Scarpa's

fascia).

The fatty layer is continuous with

the superficial fat over the rest of

the body and may be extremely

thick (3 in. [8 cm] or more in obese

patients).

The membranous layer is thin

and fades out

laterally and above, where it

becomes continuous with the

superficial fascia of the back and

the thorax, respectively.

Inferiorly, the membranous layer

passes onto the front of the thigh,

where it fuses with the deep fascia

one fingerbreadth below the

inguinal ligament.

Arrangement of the fatty layer and the

membranous layer of the superficial fascia

in the lower part of the anterior abdominal

wall. Note the line of fusion between the

membranous layer and the deep fascia of the

thigh (fascia lata).

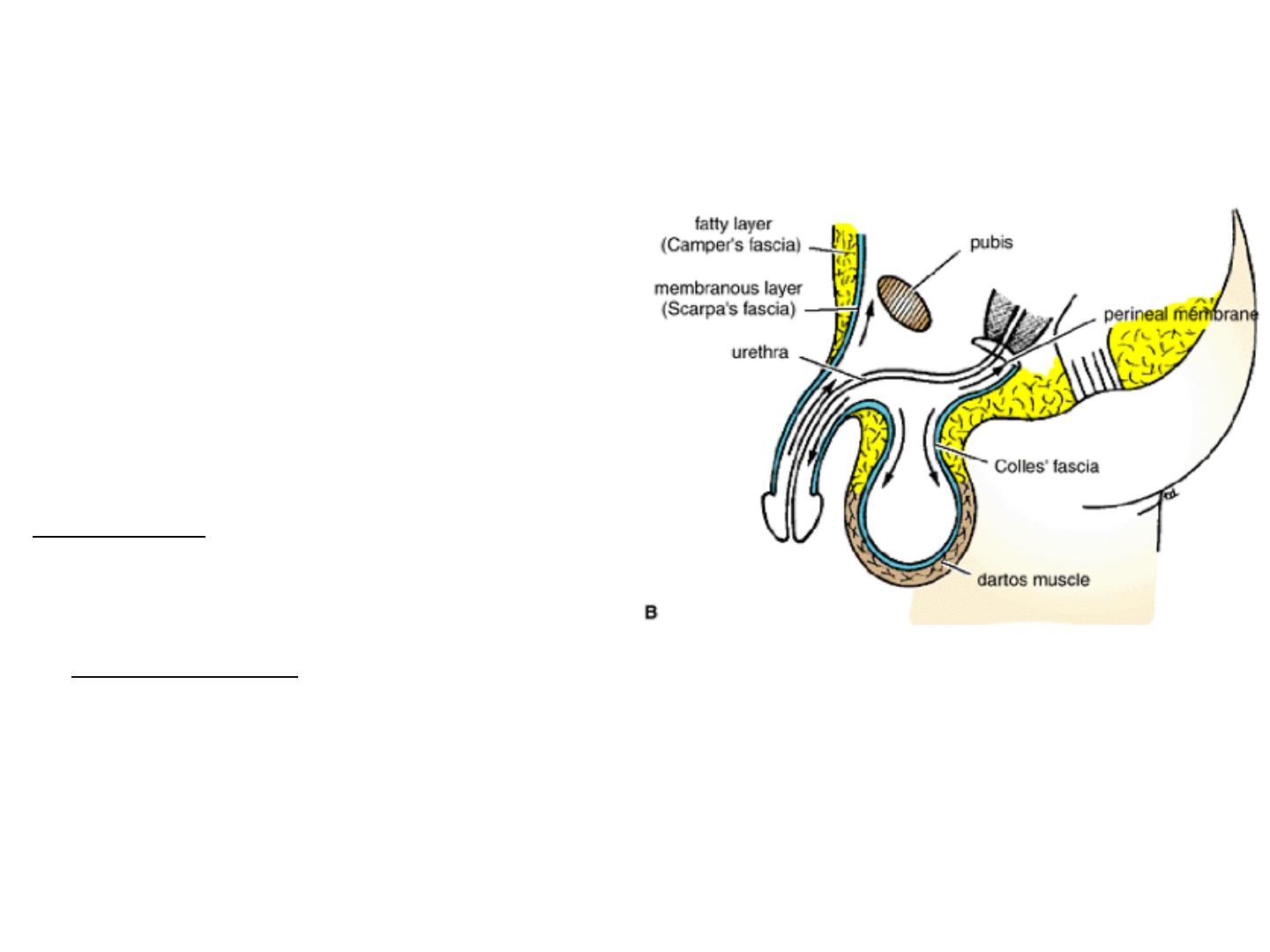

In the midline inferiorly, the

membranous layer of fascia is not

attached to the pubis but forms a

tubular sheath for the penis (or

clitoris). Below in the perineum, it

enters the wall of the scrotum (or

labia majora). From there it passes to

be attached on each side to the

margins of the pubic arch; it is here

referred to as Colles' fascia.

Posteriorly, it fuses with the perineal

body and the posterior margin of the

perineal membrane.

In the scrotum, the fatty layer of

the superficial fascia is represented

as a thin layer of smooth muscle, the

dartos muscle. The membranous

layer of the superficial fascia persists

as a separate layer.

Note the attachment of the

membranous layer to the posterior

margin of the perineal membrane.

Arrows indicate paths taken by

urine in cases of ruptured urethra.

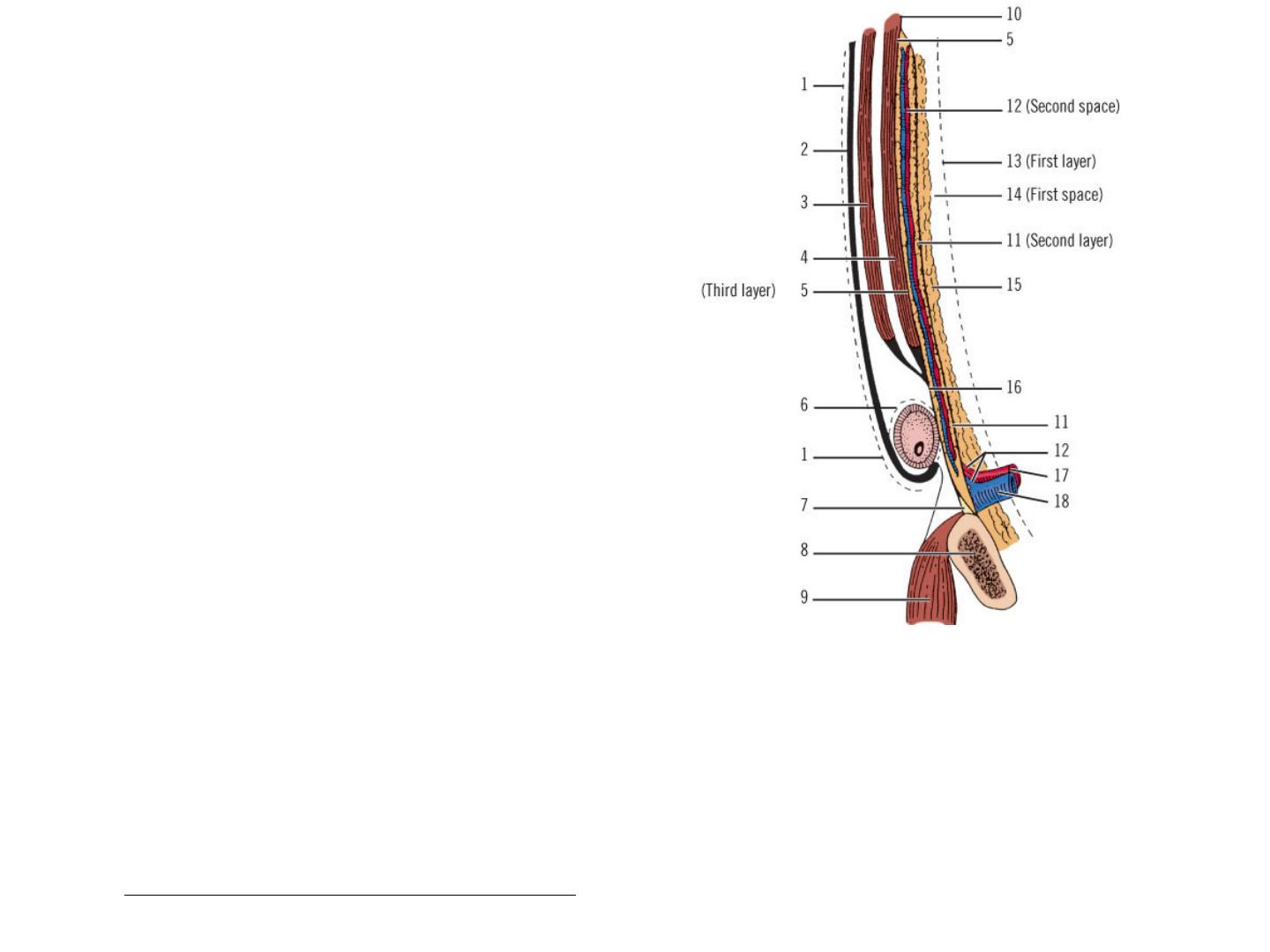

Spaces and Fossae

Space of Bogros

Fat and other connective tissue, either

thick or thin, lies within a space between

the peritoneum and the posterior lamina

of the transversalis fascia that is called the

space of Bogros. A triangular space with

the following boundaries:

Lateral: Iliac fascia

Anterior: Transversalis fascia

Medial: Parietal peritoneum

Highly diagrammatic representation of the layers of the abdominal wall and inguinal area. 1,

External oblique fascia (fascia of Gallaudet); 2, External oblique aponeurosis; 3, Internal

oblique muscle; 4, Transversus abdominis muscle and its aponeurosis; 5, Transversalis fascia

anterior lamina (third layer); 6, External spermatic fascia; 7, Cooper's ligament; 8, Pubic bone;

9, Pectineus muscle; 10, Possible union of transversalis fascia laminae; 11, Transversalis

fascia posterior lamina (second layer); 12, Vessels (second space); 13, Peritoneum (first

layer); 14, Space of Bogros (first space); 15, Preperitoneal fat; 16, Transversus abdominis

aponeurosis and anterior lamina of transversalis fascia; 17, Femoral artery; 18, Femoral vein.

Superficial Perineal Cleft

This potential space lies between Colles' membranous fascia of

the perineum and the muscle fascia of the superficial perineal

pouch. The superficial pouch contains the ischiocavernosus

and bulbospongiosus muscles and erectile bodies, etc. The

superficial pouch covers the more deeply situated urogenital

diaphragm. The superficial perineal cleft is present in the

scrotum or the labia majora and is continuous with the

potential space deep to the fascia of Scarpa of the anterior

abdominal wall.

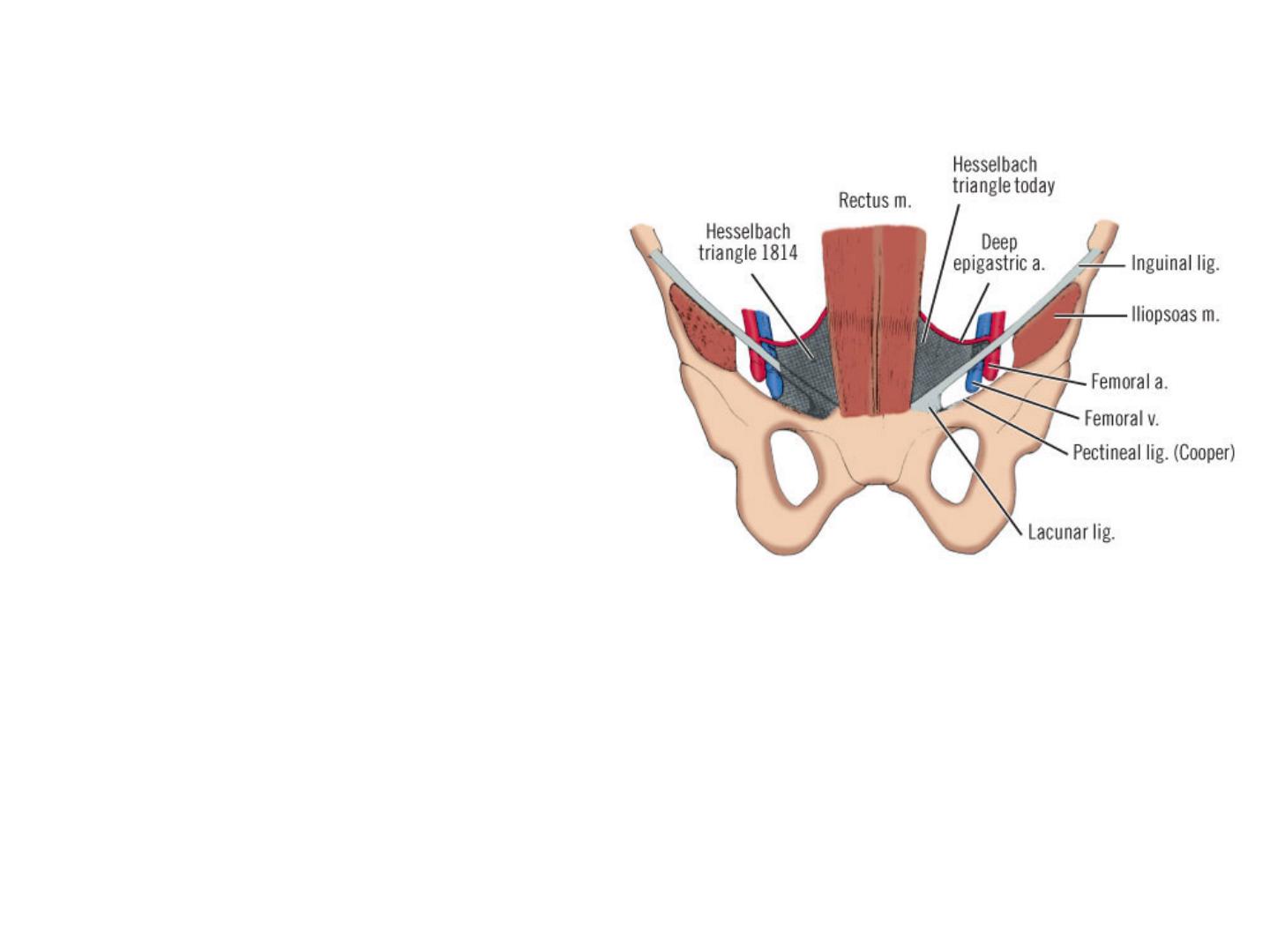

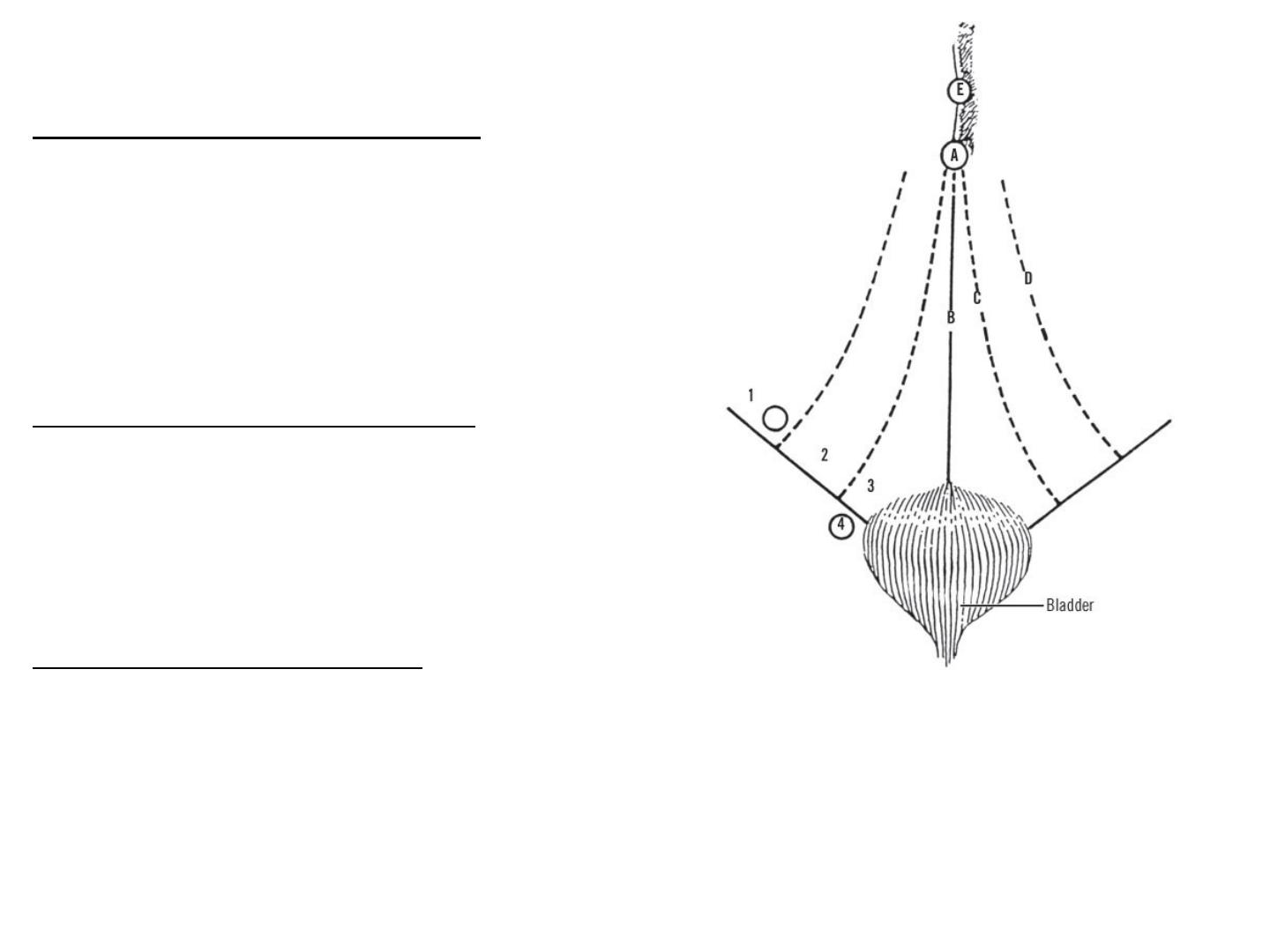

Hesselbach's Triangle

Hesselbach's triangle is

defined as having the

inferior (deep) epigastric

vessels as its superior or

lateral border, the lateral

edge of the rectus

abdominis muscle as its

medial border, and the

inguinal ligament as its

inferolateral border.

Most direct inguinal

hernias and external

supravesical inguinal

hernias occur in this area.

Hesselbach triangle as originally described

(left) and as accepted today (right). Note

that part of supravesical fossa lies within

triangle.

Fossae of the Lower Anterior

Abdominal Wall

The posterior surface of the

anterior abdominal wall above

the inguinal ligament is divided

into three shallow fossae.

Located on either side of the

midline, these fossae are

marked by the obliterated

embryonic urachus, extending

from the dome of the bladder to

the umbilicus (median

umbilical ligament). Laterally,

the fossae are separated by the

medial umbilical ligaments

(obliterated umbilical arteries)

and the lateral umbilical

ligaments (inferior or deep

epigastric arteries).

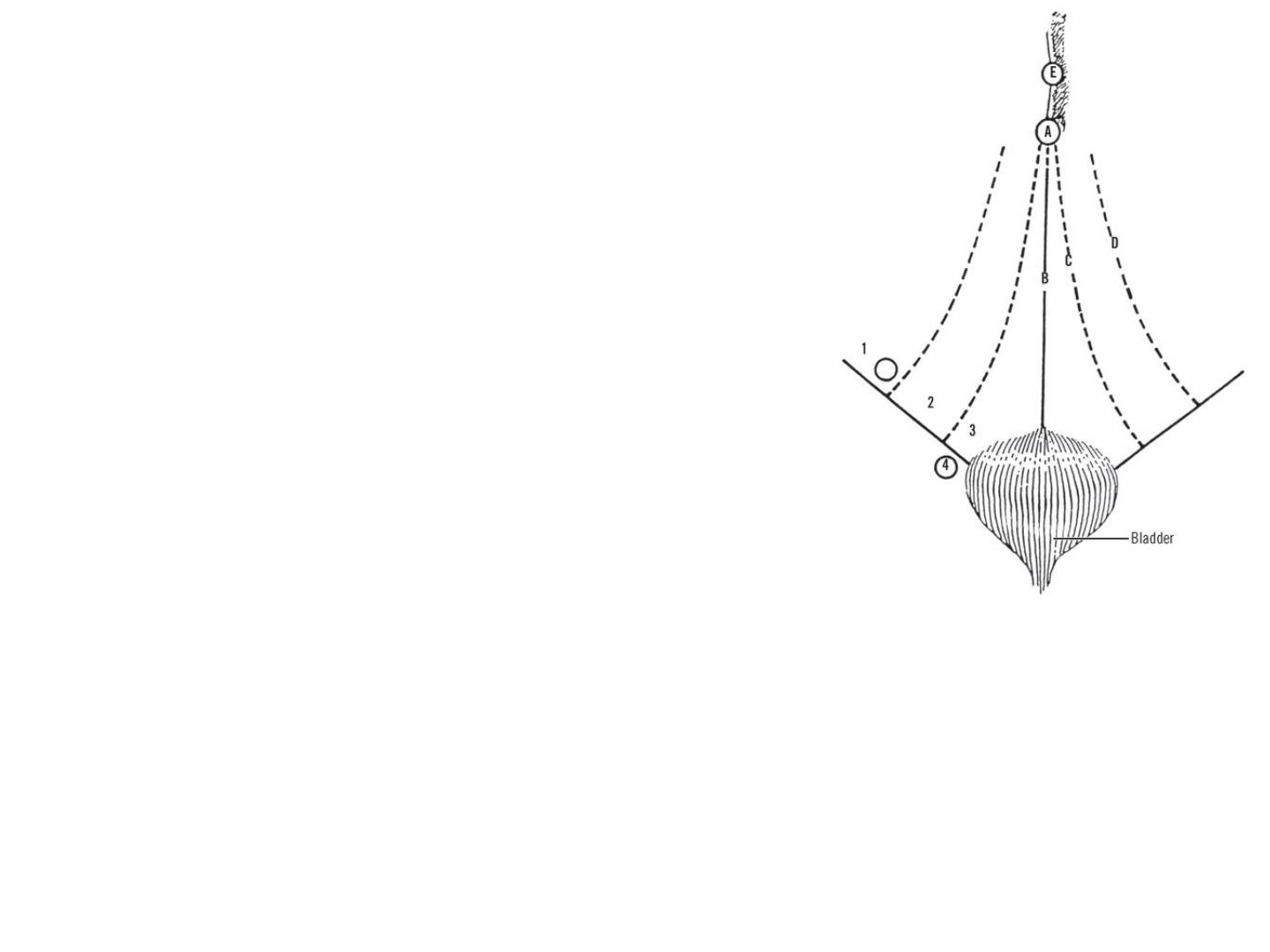

Fossae of anterior abdominal wall and their

relation to sites of groin hernias. A, Umbilicus.

B, Median umbilical ligament (obliterated

urachus). C, Medial umbilical ligament

(obliterated umbilical arteries). D, Lateral

umbilical ligament containing inferior (deep)

epigastric arteries. E, Falciform ligament.

The fossae are as follows:

The lateral inguinal fossae ,

lateral to the inferior epigastric

arteries, contain the internal

inguinal rings. They are the

site of indirect inguinal

hernias.

The medial inguinal fossae,

between the inferior epigastric

arteries and the medial

umbilical ligaments, are the

site of direct inguinal hernias.

The supravesical fossae,

between the medial and

median umbilical ligaments,

are the site of external

supravesical hernias.

Sites of possible hernias: 1, Lateral fossa

(indirect inguinal hernia); 2, Medial fossa

(direct inguinal hernia); 3, Supravesical fossa

(supravesical hernia); 4, Femoral ring (femoral

hernia).

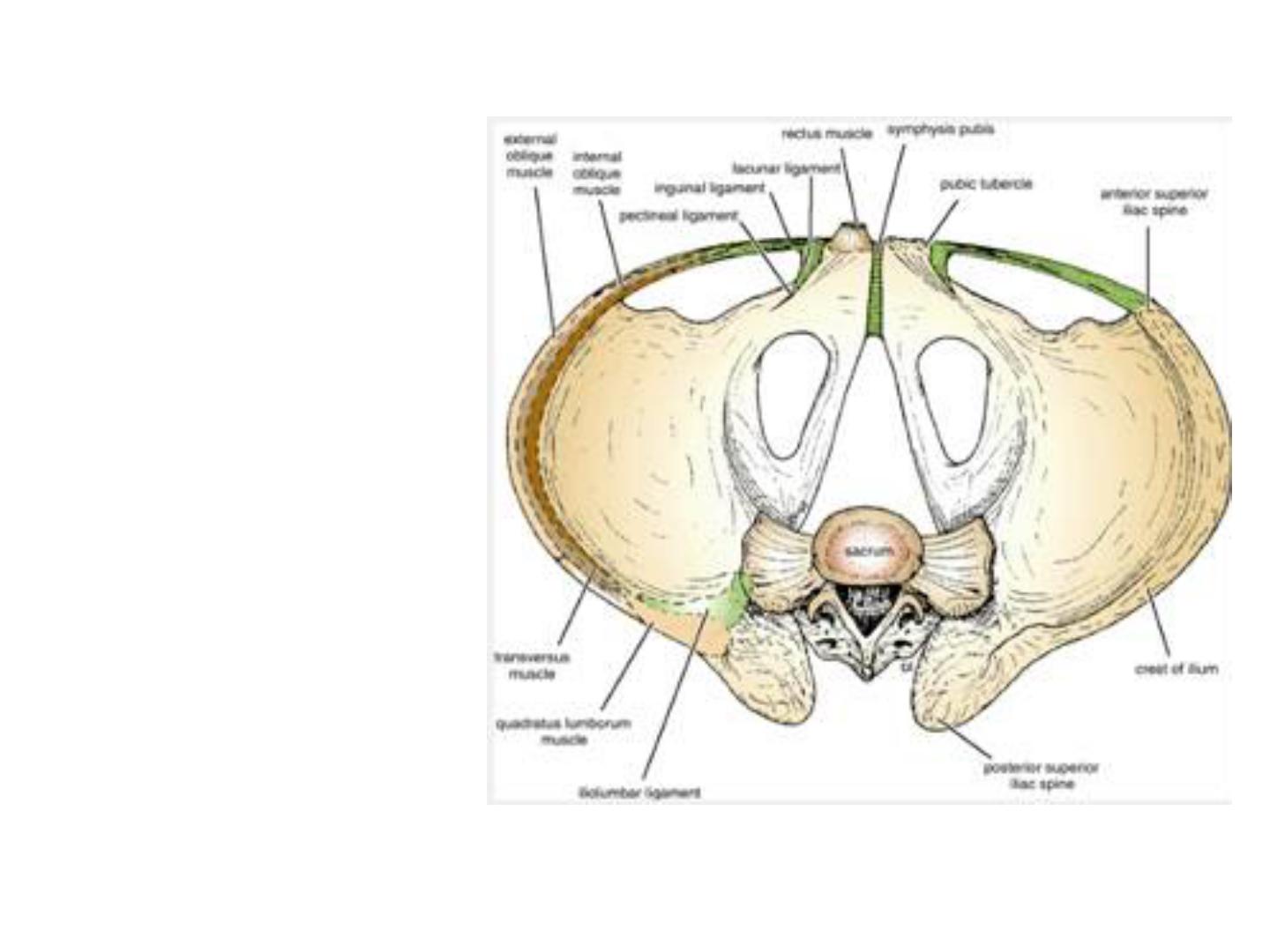

Spaces between the Inguinal Ligament and the Iliopectineal Line

Between the inguinal ligament and the

superior pubic ramus is a space organized

into three compartments: neuromuscular,

vascular, and femoral canal. The most

lateral of these is the neuromuscular. This

area contains the iliopsoas muscle, the

femoral nerve, and the lateral femoral

cutaneous nerve.

The femoral nerve may pierce the iliacus

muscle. It may be found between the

femoral artery and vein. Part of the nerve

may be a fellow traveler with the superior

gluteal nerve to supply the rectus femoris

and vastus lateralis. Or the femoral nerve

may be found deep in the iliacus muscle.

Medial to the area containing the iliopsoas

muscle, the femoral nerve, and the lateral

femoral cutaneous nerve is the vascular

compartment which contains the femoral

artery and vein.

Clinical Notes

Membranous Layer of Superficial Fascia and the Extravasation of

Urine

The membranous layer of the superficial fascia is important clinically because

beneath it is a potential closed space that does not open into the thigh but is

continuous with the superficial perineal pouch via the penis and scrotum. Rupture

of the penile urethra may be followed by extravasation of urine into the scrotum,

perineum, and penis and then up into the lower part of the anterior abdominal

wall deep to the membranous layer of fascia. The urine is excluded from the thigh

because of the attachment of the fascia to the fascia lata.

Deep Fascia

The deep fascia in the anterior abdominal wall is merely a thin layer of

connective tissue covering the muscles; it lies immediately deep to the

membranous layer of superficial fascia.

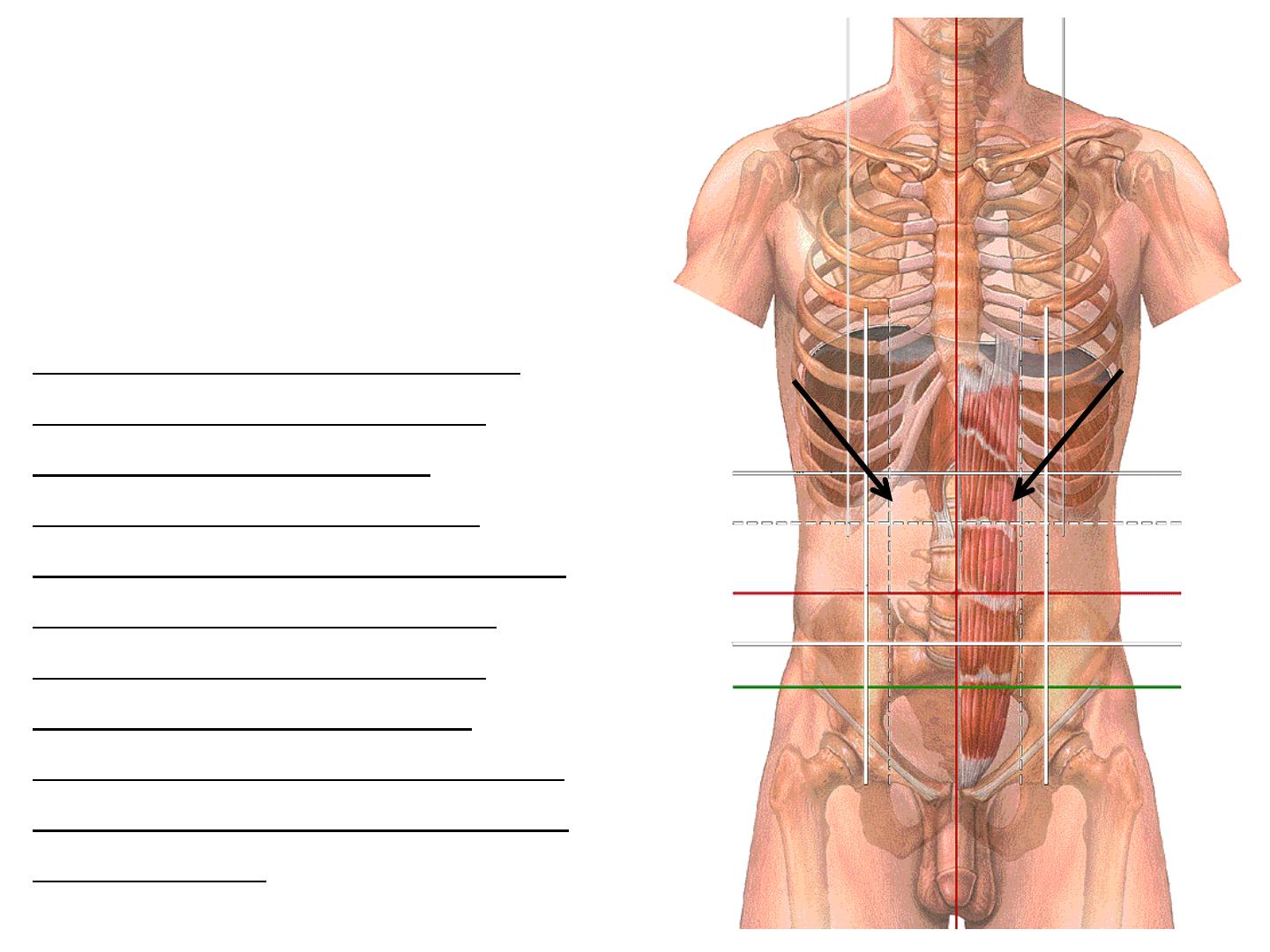

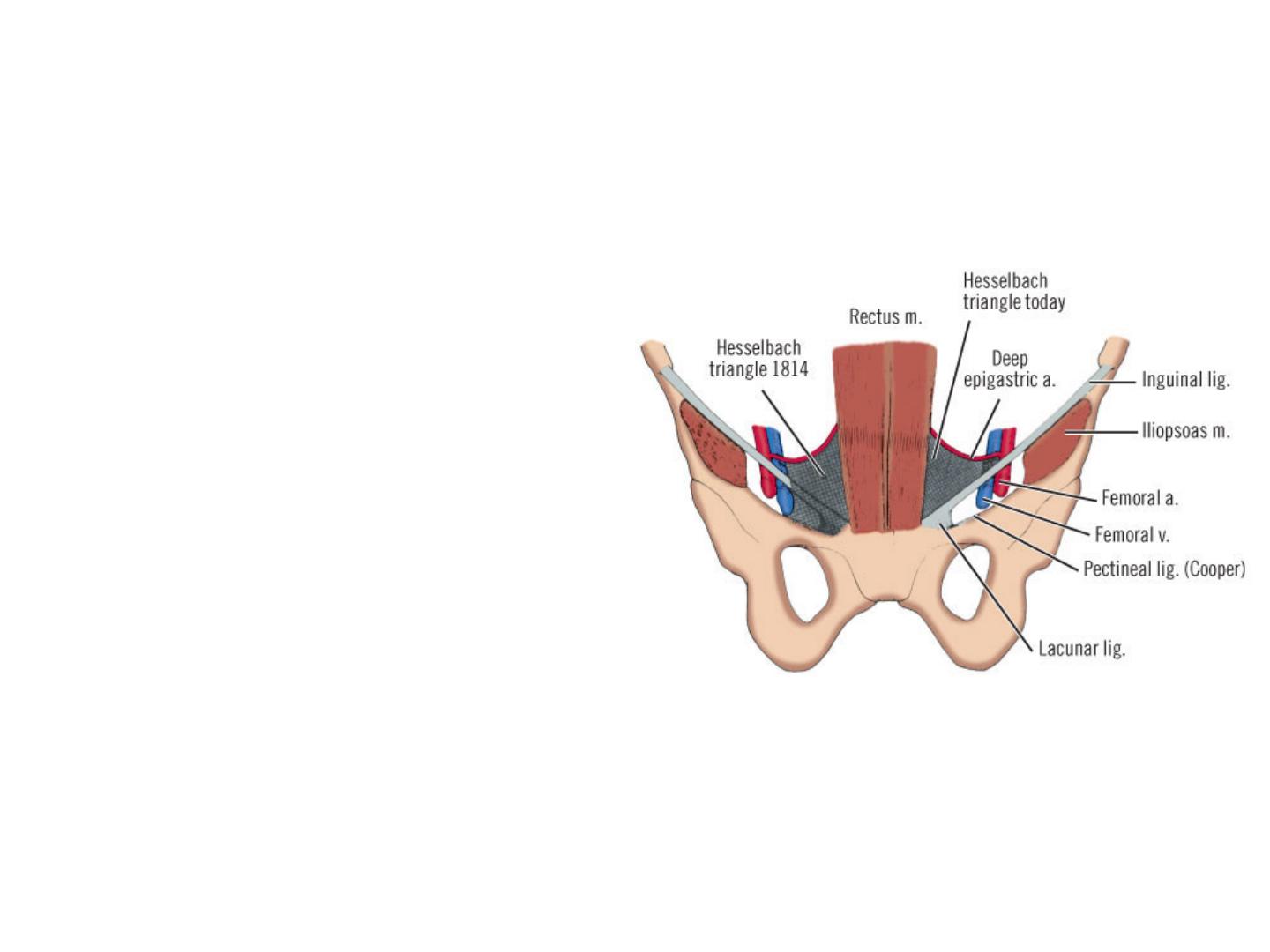

● Muscle arrangements

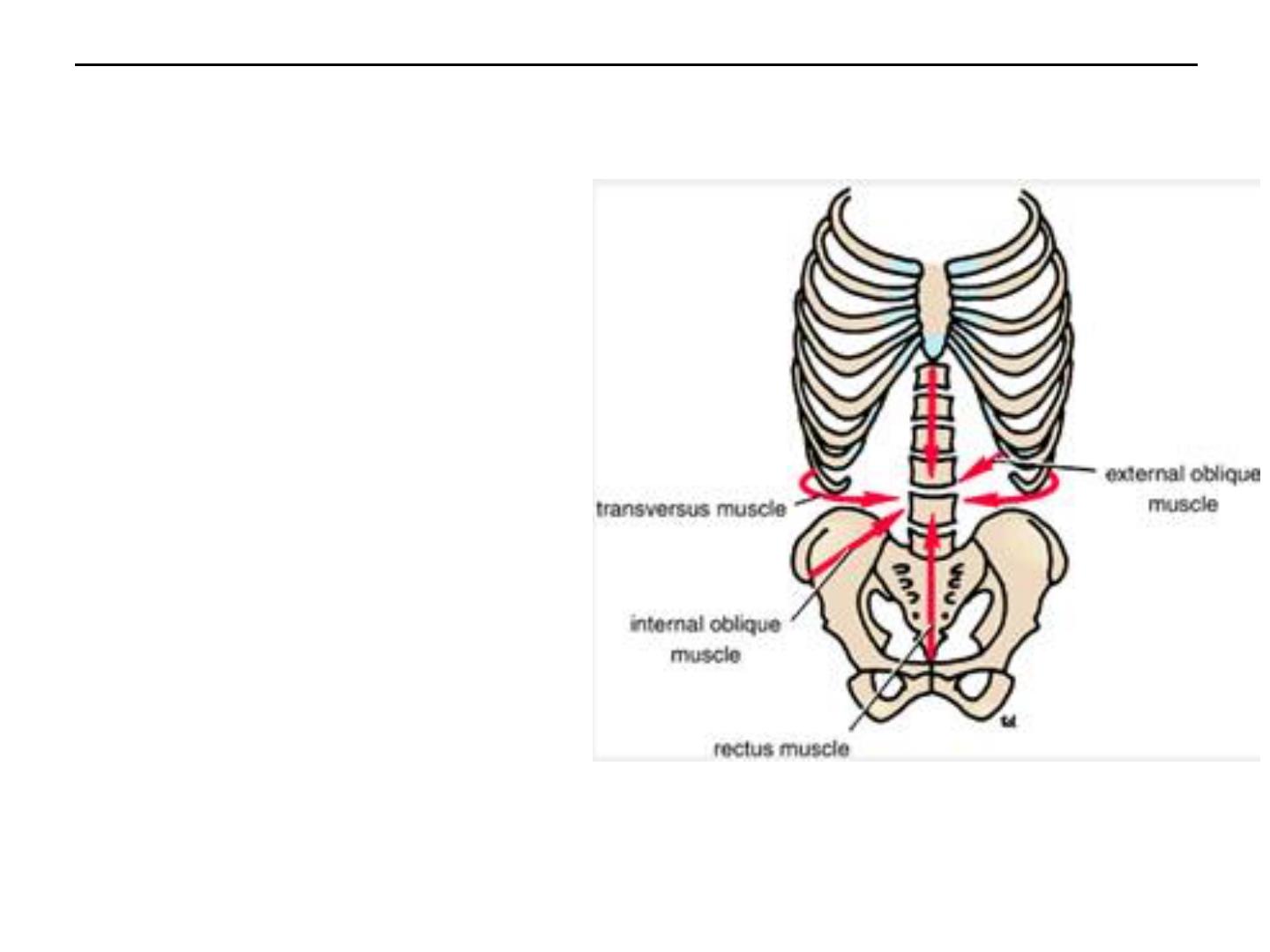

Muscles of the Anterior

Abdominal Wall

The muscles of the

anterior abdominal wall

consist of three broad thin

sheets that are aponeurotic

in front; from exterior to

interior they are

the external oblique,

internal oblique, and

transversus.

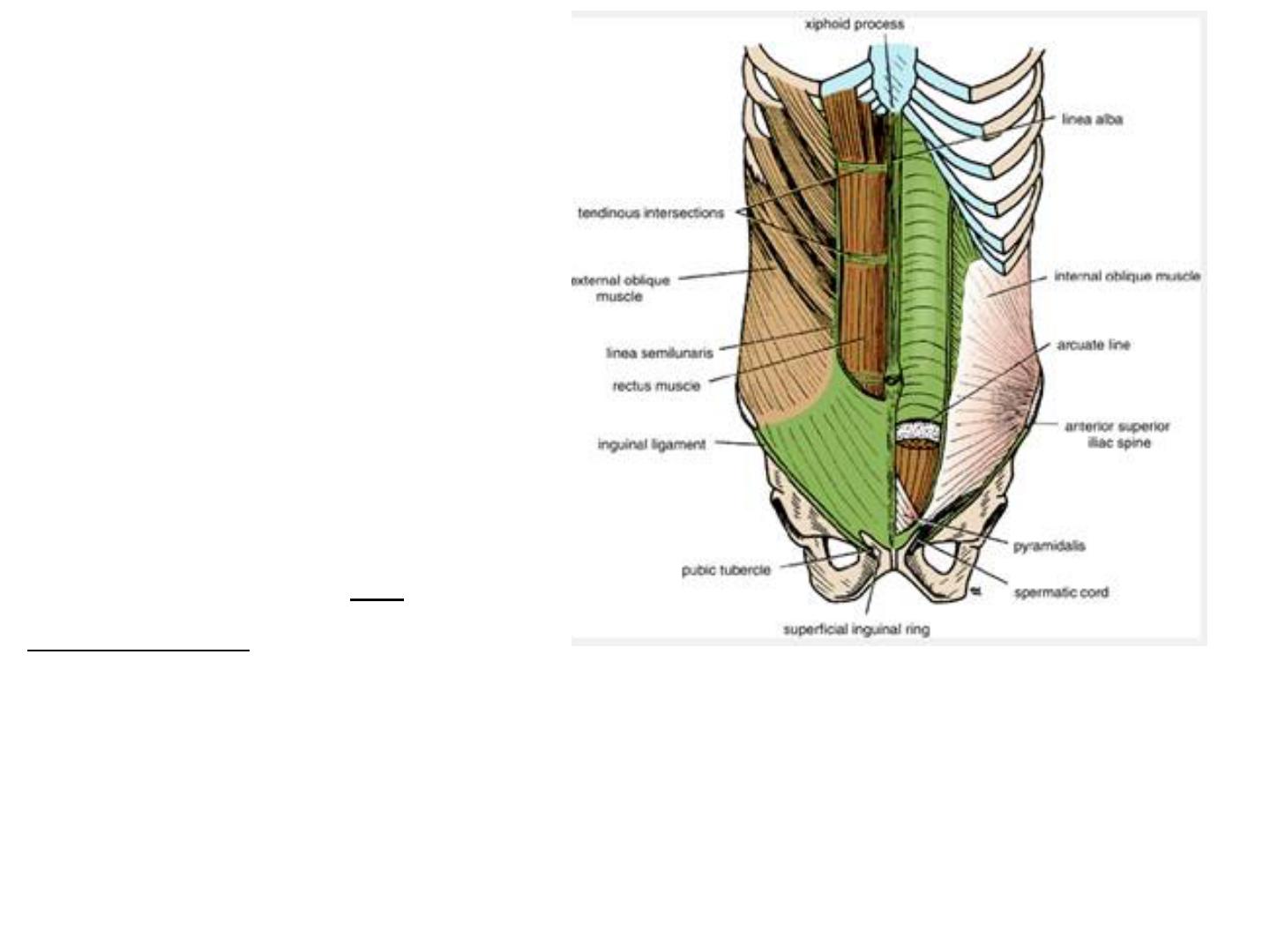

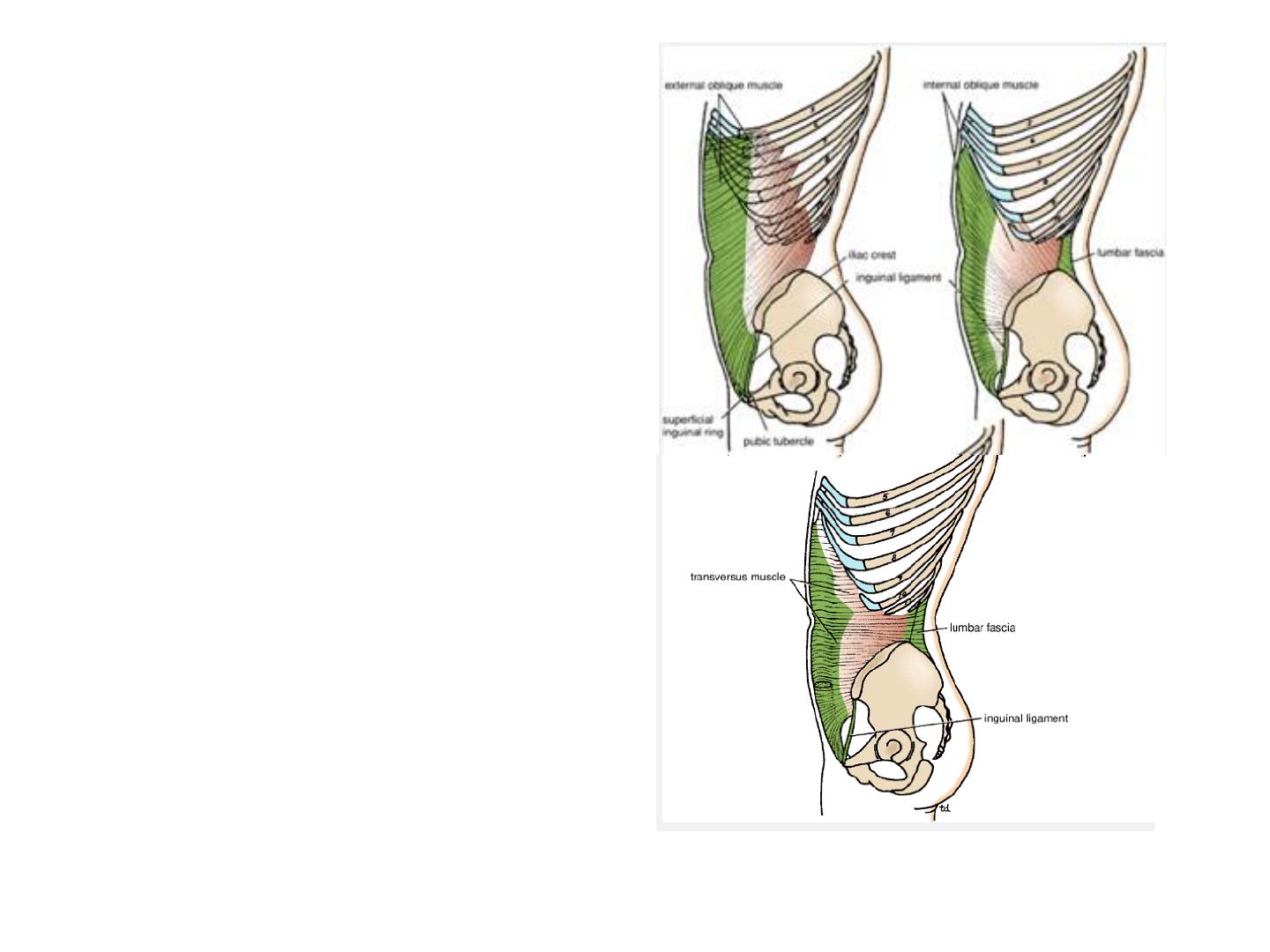

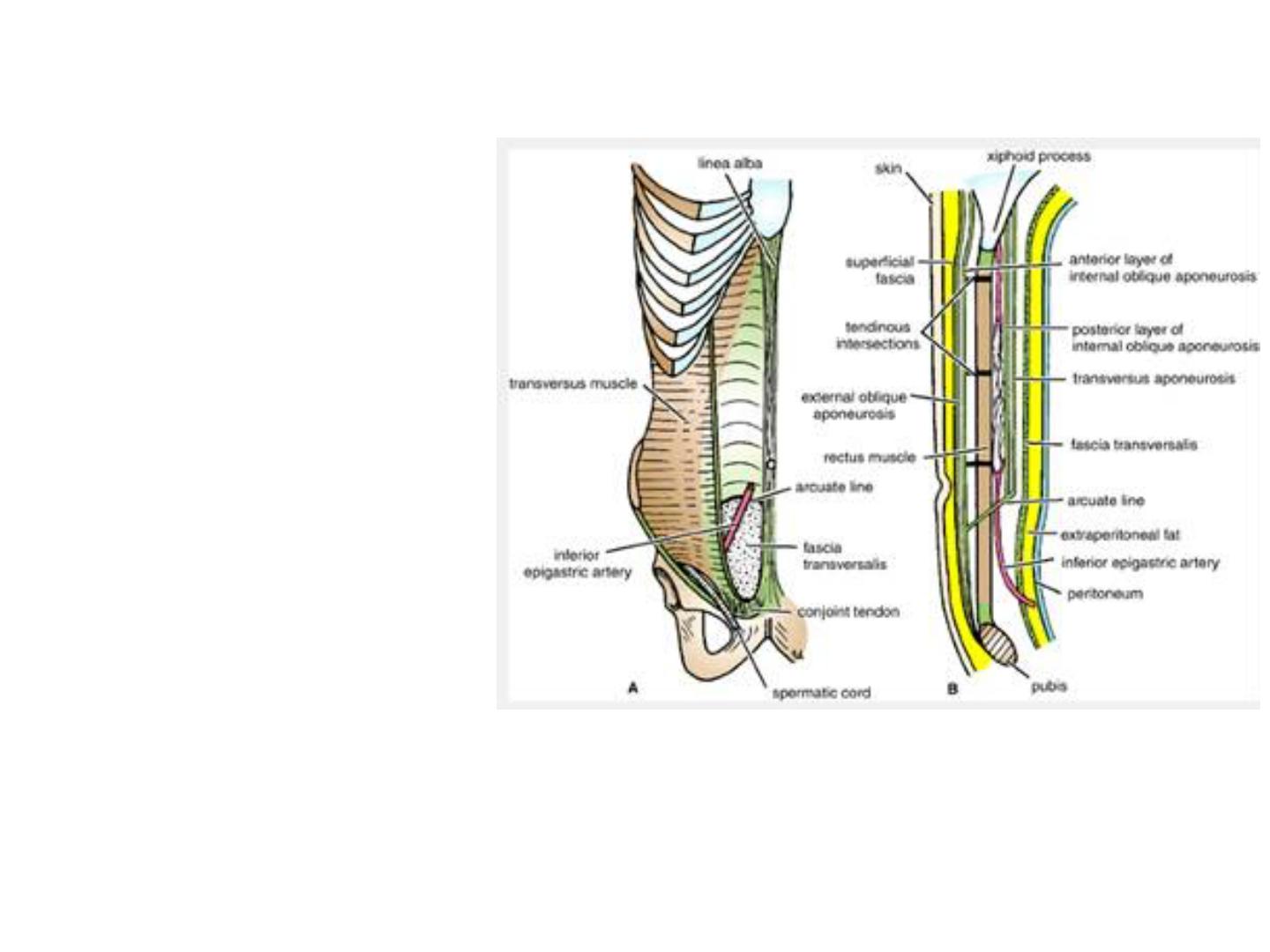

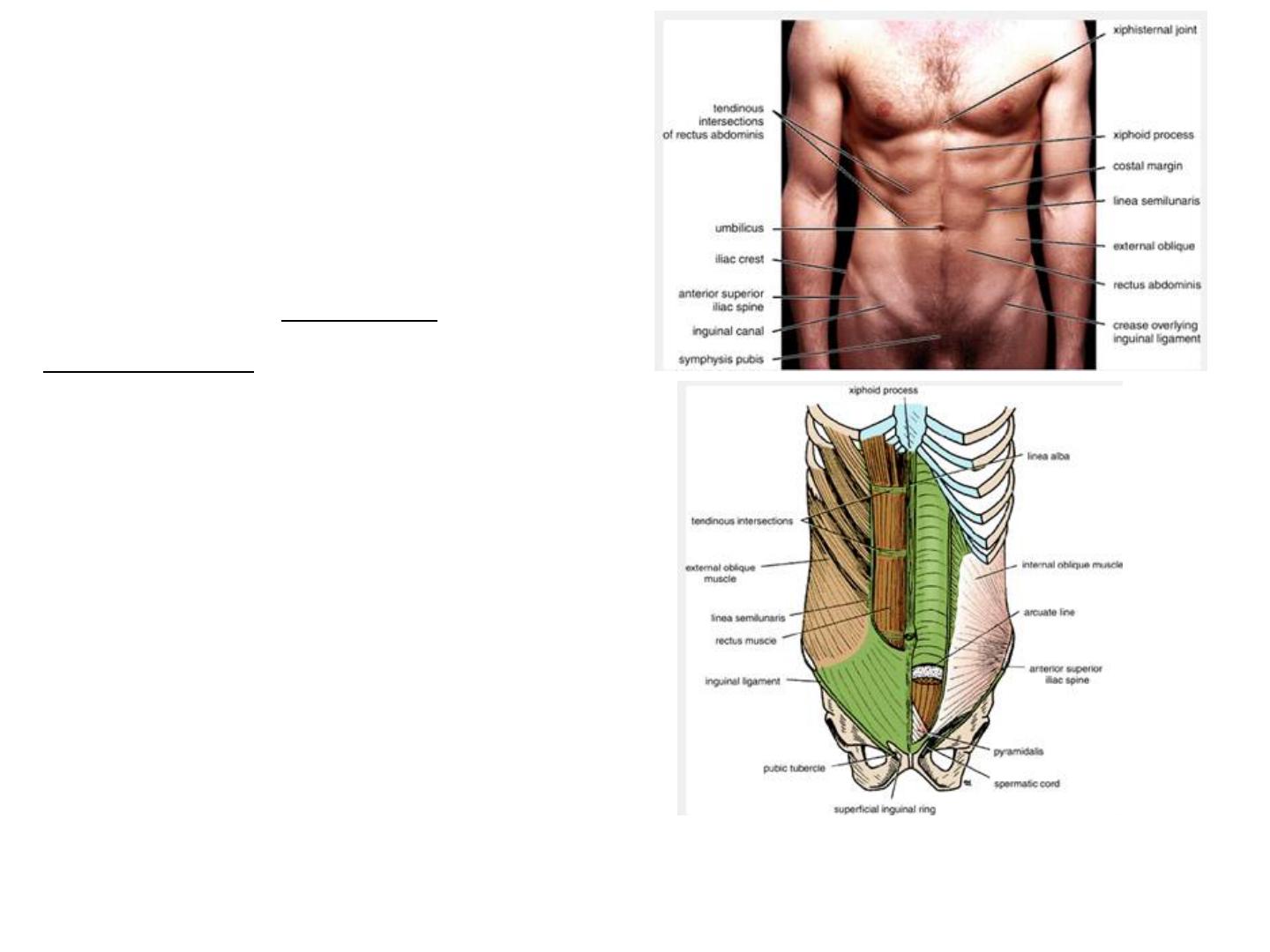

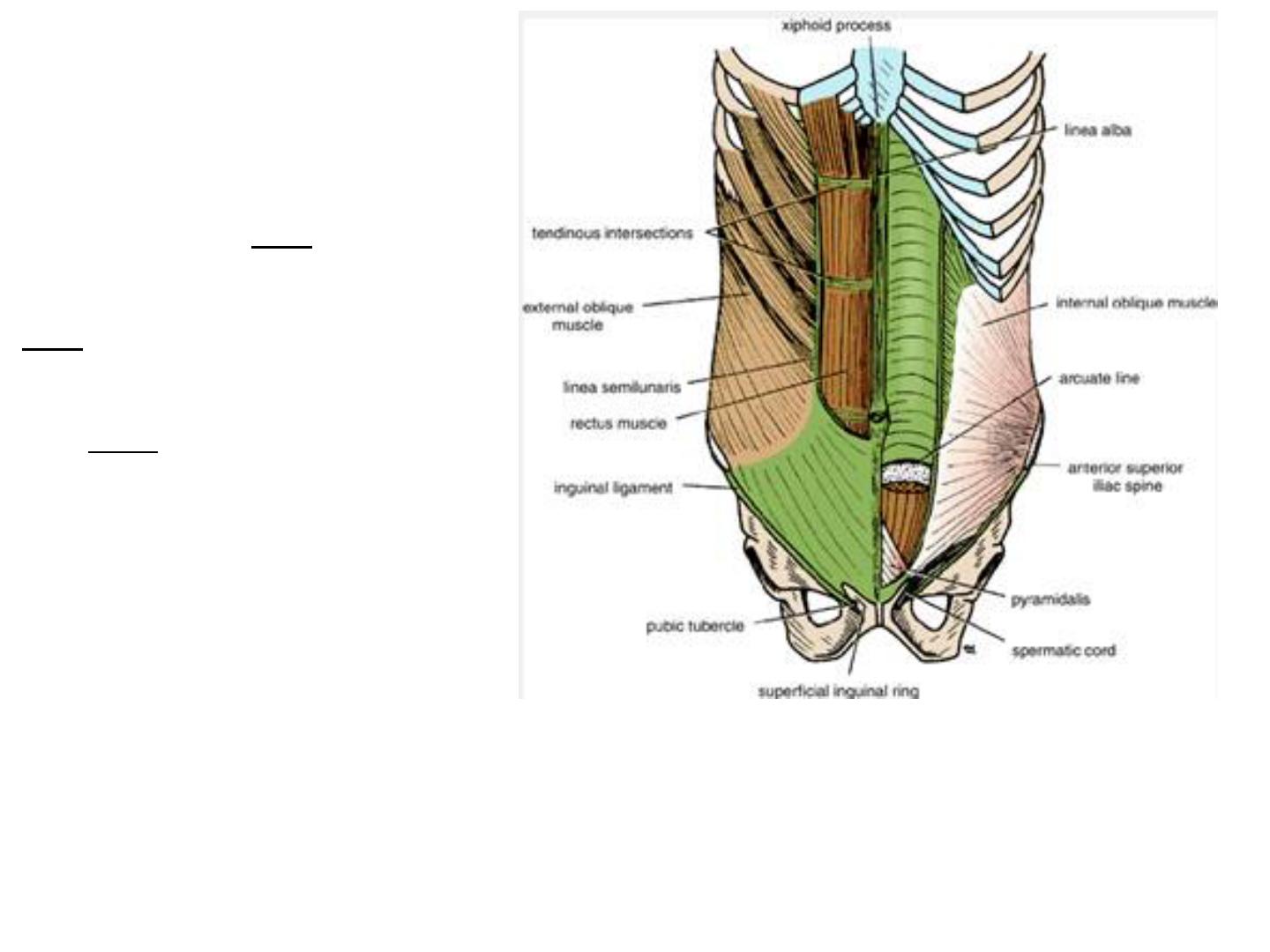

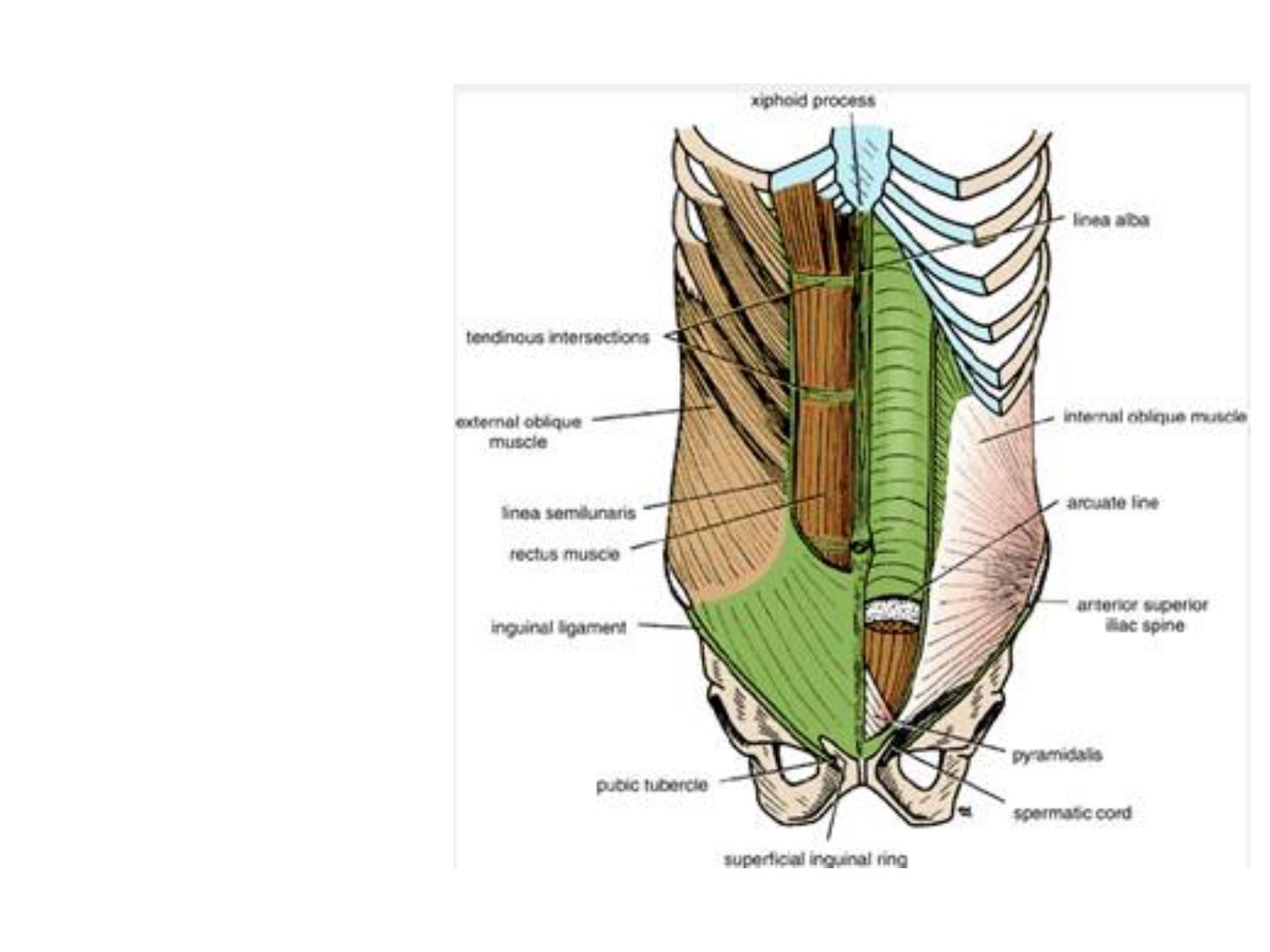

External oblique, internal oblique, and transversus

muscles of the anterior abdominal wall.

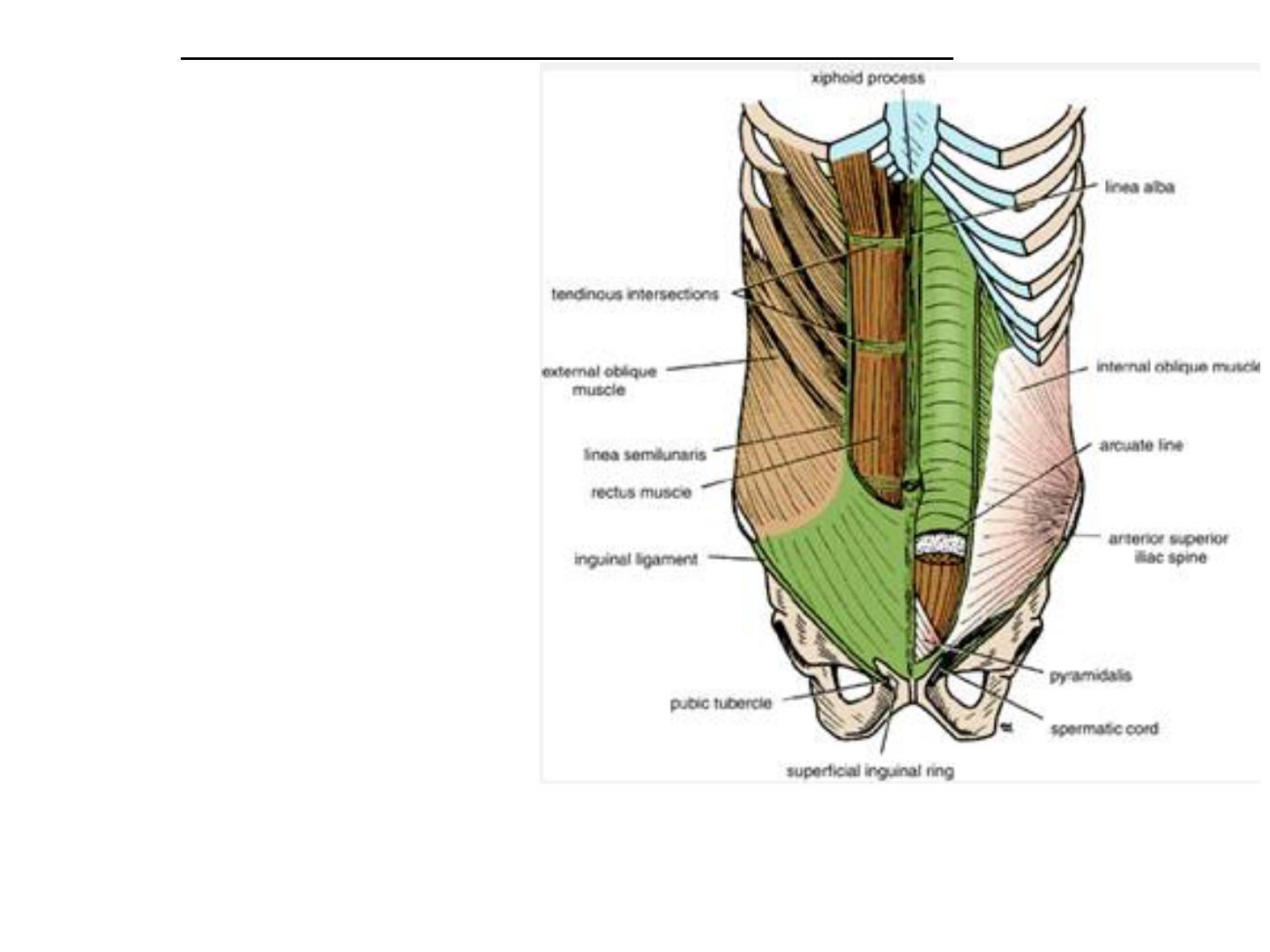

Muscles of the Anterior

Abdominal Wall

On either side of the

midline anteriorly is, in

addition, a wide vertical

muscle, the rectus

abdominis. As the

aponeuroses of the three

sheets pass forward, they

enclose the rectus

abdominis to form the

rectus sheath. The lower

part of the rectus sheath

might contain a small

muscle called the

pyramidalis.

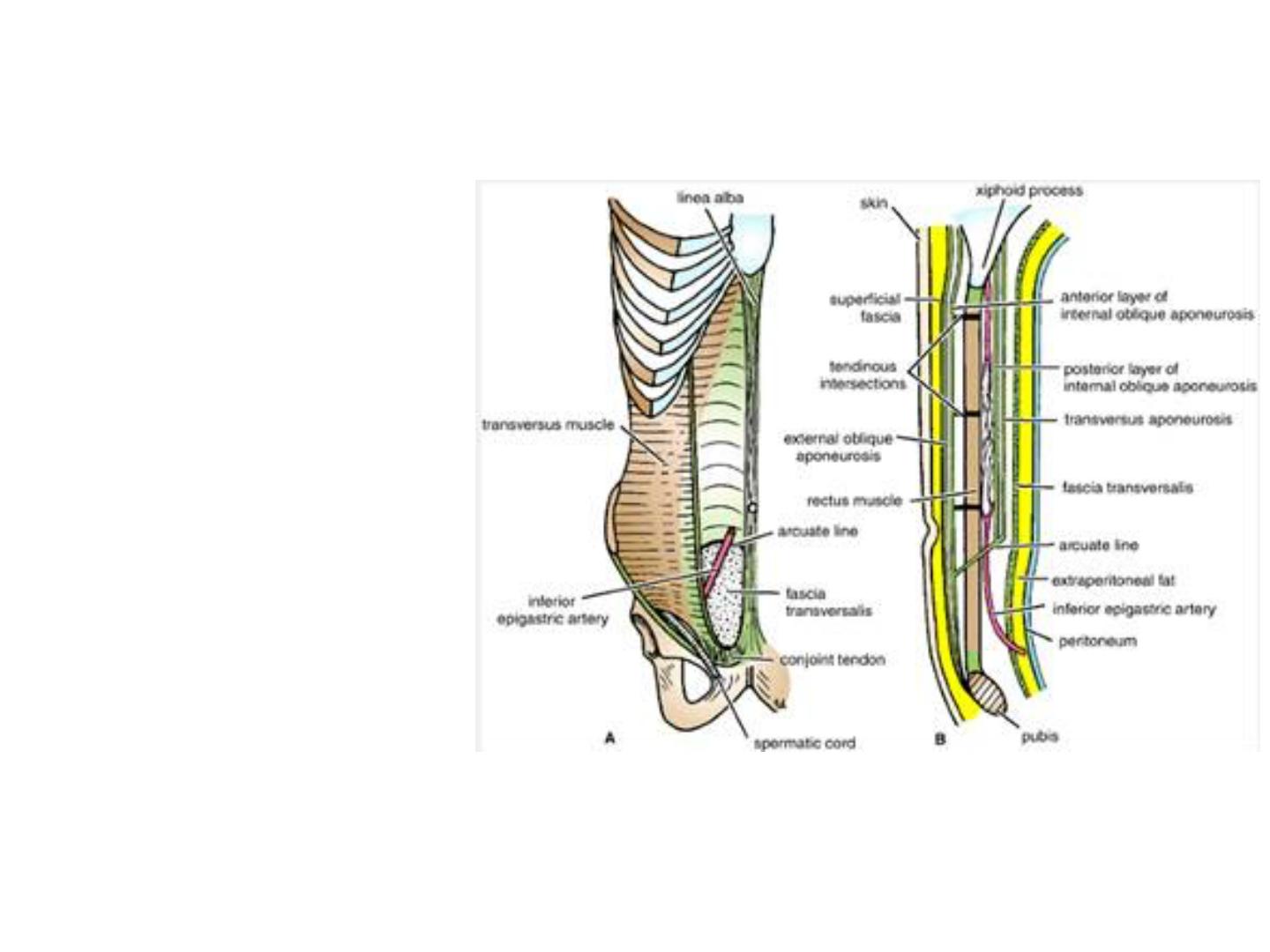

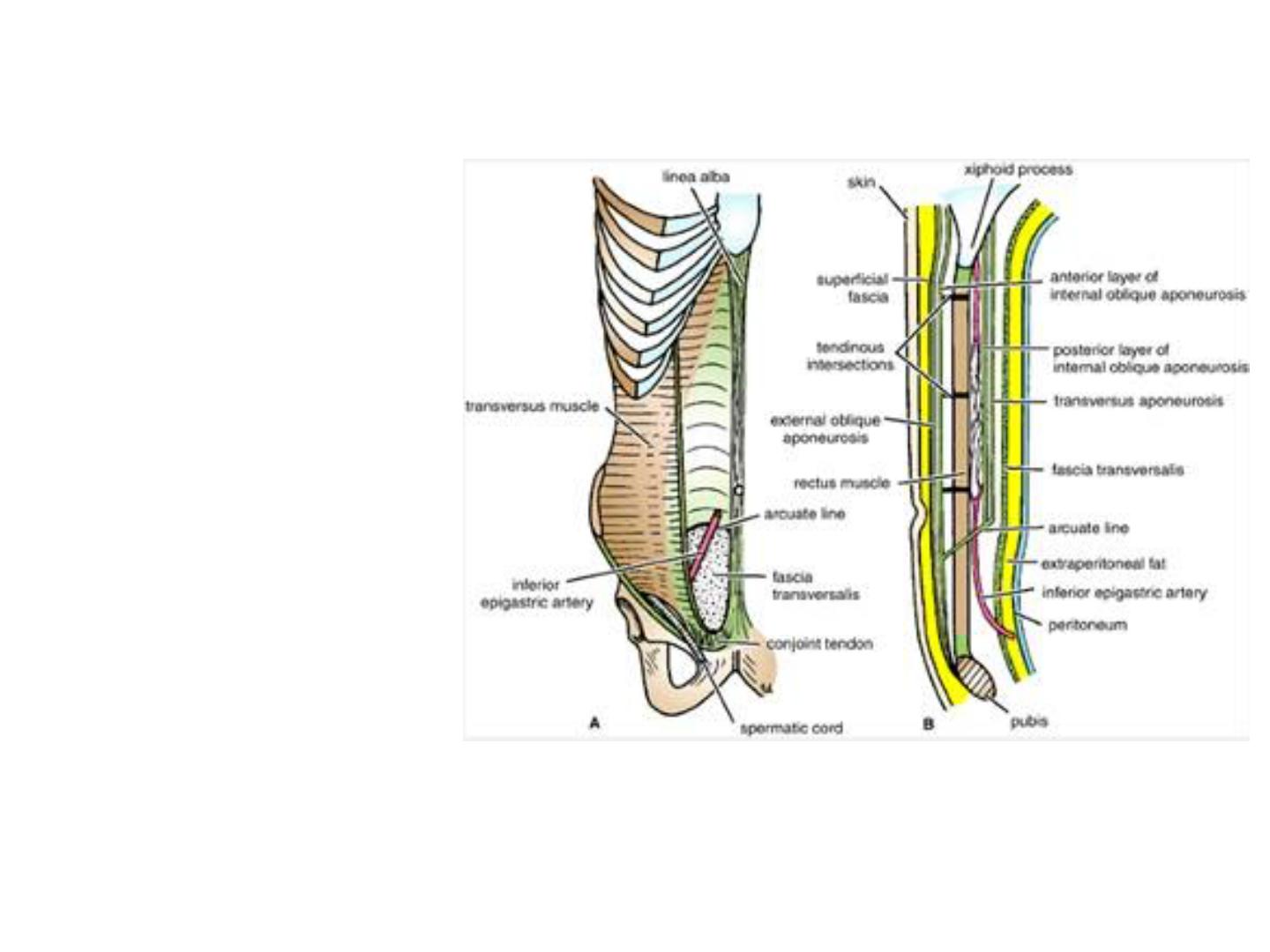

Anterior view of the rectus abdominis muscle and

the rectus sheath. Left: The anterior wall of the

sheath has been partly removed, revealing the

rectus muscle with its tendinous intersections.

Right: The posterior wall of the rectus sheath is

shown. The edge of the arcuate line is shown at

the level of the anterior superior iliac spine.

External Oblique

The external oblique

muscle is a broad,

thin, muscular sheet

that arises from the

outer surfaces of

the lower eight ribs

and fans out to be

inserted into the

xiphoid process, the

linea alba, the pubic

crest, the pubic

tubercle, and the

anterior half of the

iliac crest.

•

Double click to add text

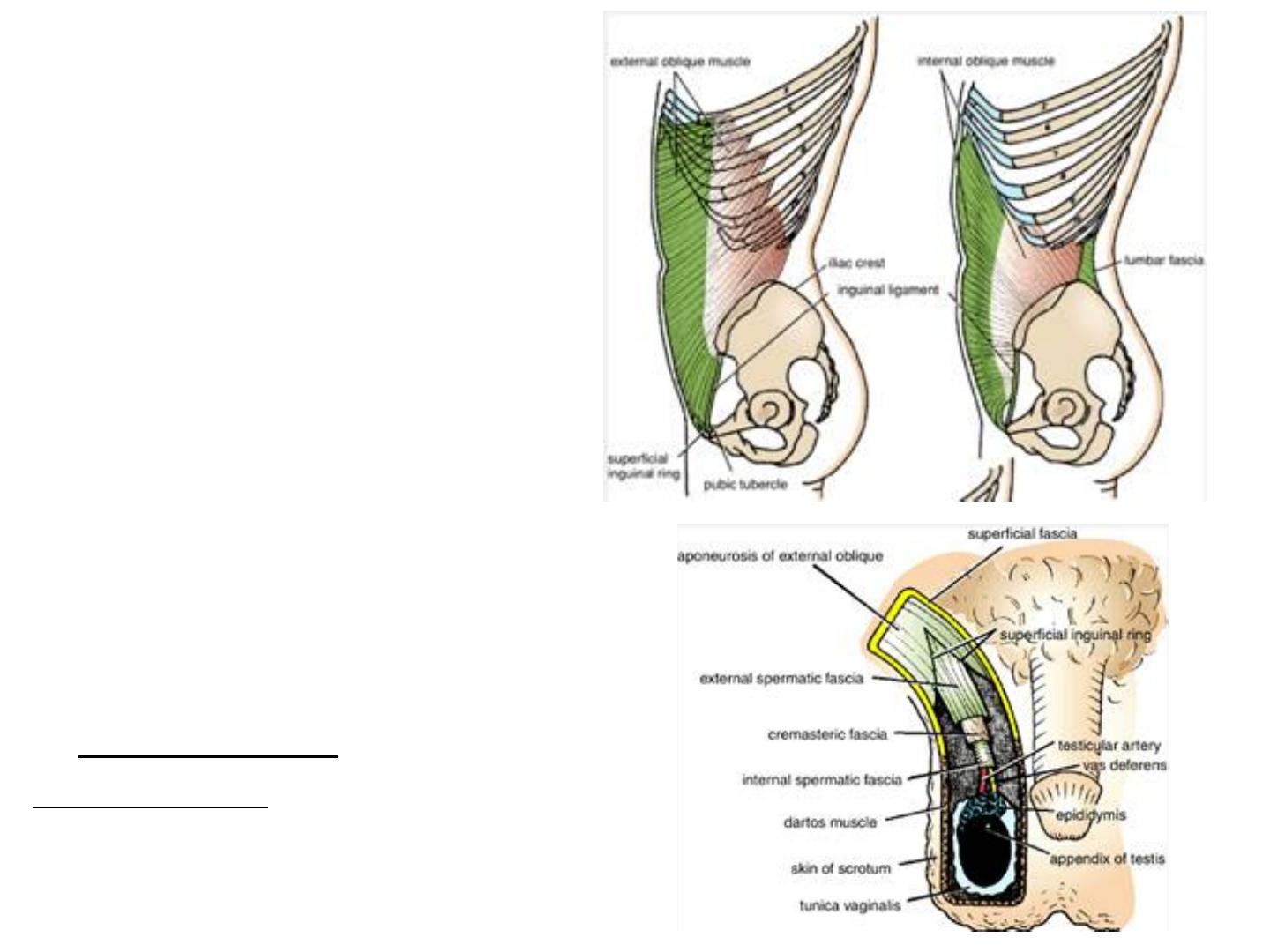

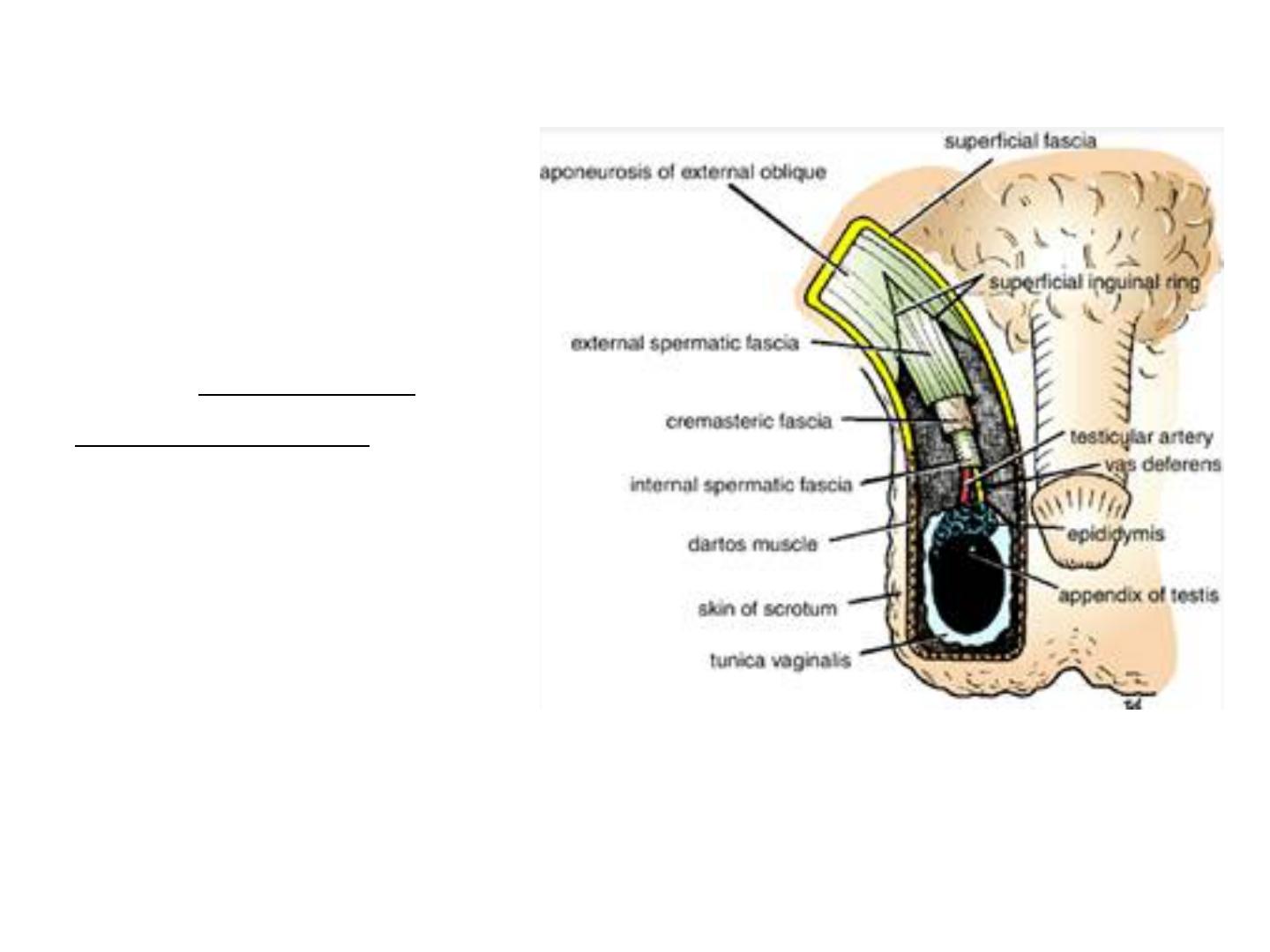

Most of the fibers are

inserted by means of a

broad aponeurosis. Note

that the most posterior

fibers passing down to

the iliac crest form a

posterior free border.

A triangular-shaped

defect in the external

oblique aponeurosis lies

immediately above and

medial to the pubic

tubercle. This is known

as the superficial

inguinal ring.

The spermatic cord (or

round ligament of the

uterus) passes through

this opening and

carries the external

spermatic fascia (or

the external covering

of the round ligament

of the uterus) from the

margins of the ring.

Between the anterior

superior iliac spine

and the pubic tubercle,

the lower border of the

aponeurosis is folded

backward on itself,

forming the inguinal

ligament.

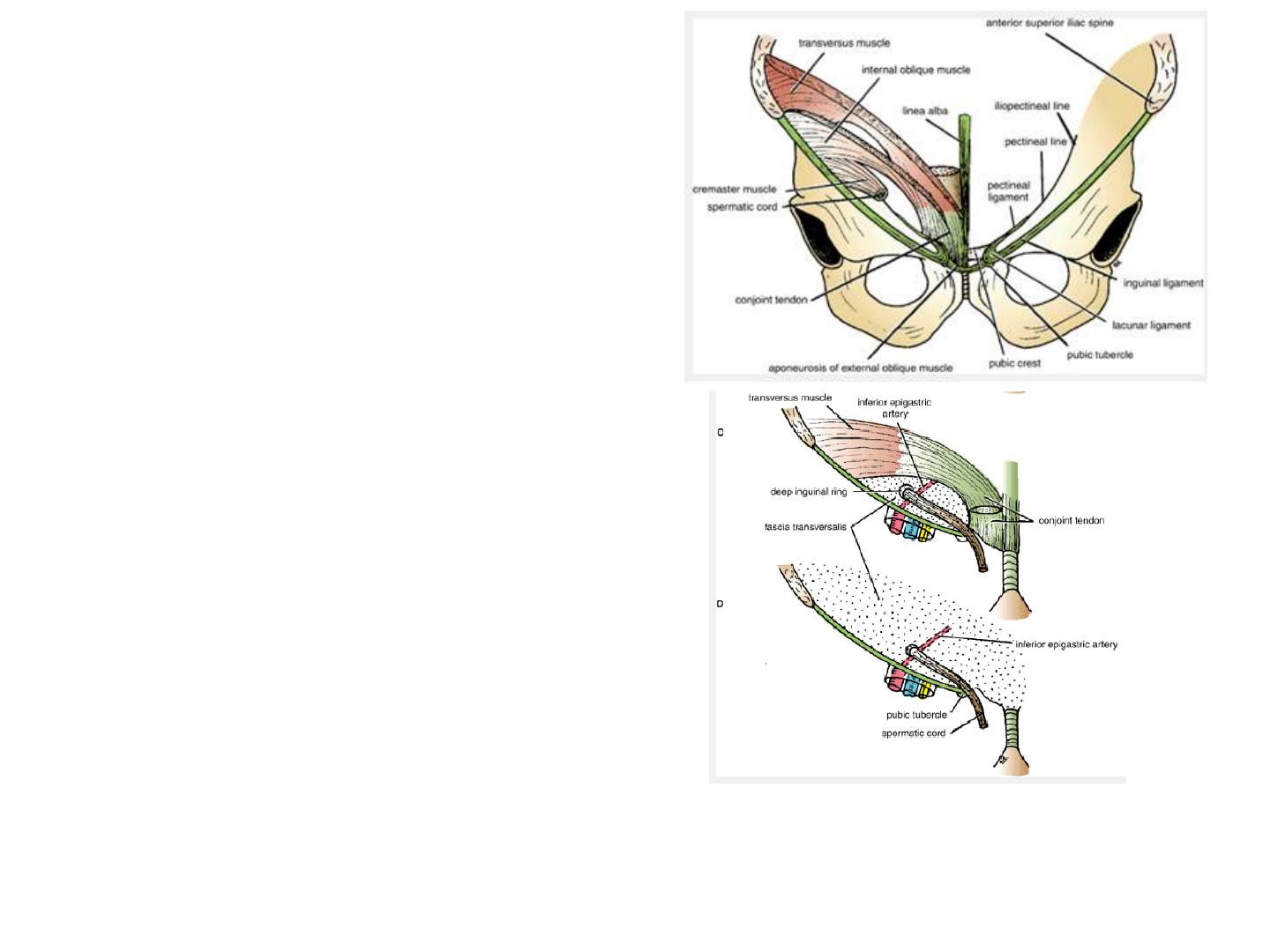

From the medial end of

the ligament, the lacunar

ligament extends

backward and upward to

the pectineal line on the

superior ramus of the

pubis.

Its sharp, free

crescentic edge

forms the medial

margin of the

femoral ring. On

reaching the

pectineal line, the

lacunar ligament

becomes

continuous with a

thickening of the

periosteum called

the pectineal

ligament.

The lateral part of the

posterior edge of the

inguinal ligament

gives origin to part of

the internal oblique

and transversus

abdominis muscles.

To the inferior

rounded border of the

inguinal ligament is

attached the deep

fascia of the thigh, the

fascia lata.

A. Arrangement of the fatty layer and the

membranous layer of the superficial fascia

in the lower part of the anterior abdominal

wall. Note the line of fusion between the

membranous layer and the deep fascia of the

thigh (fascia lata).

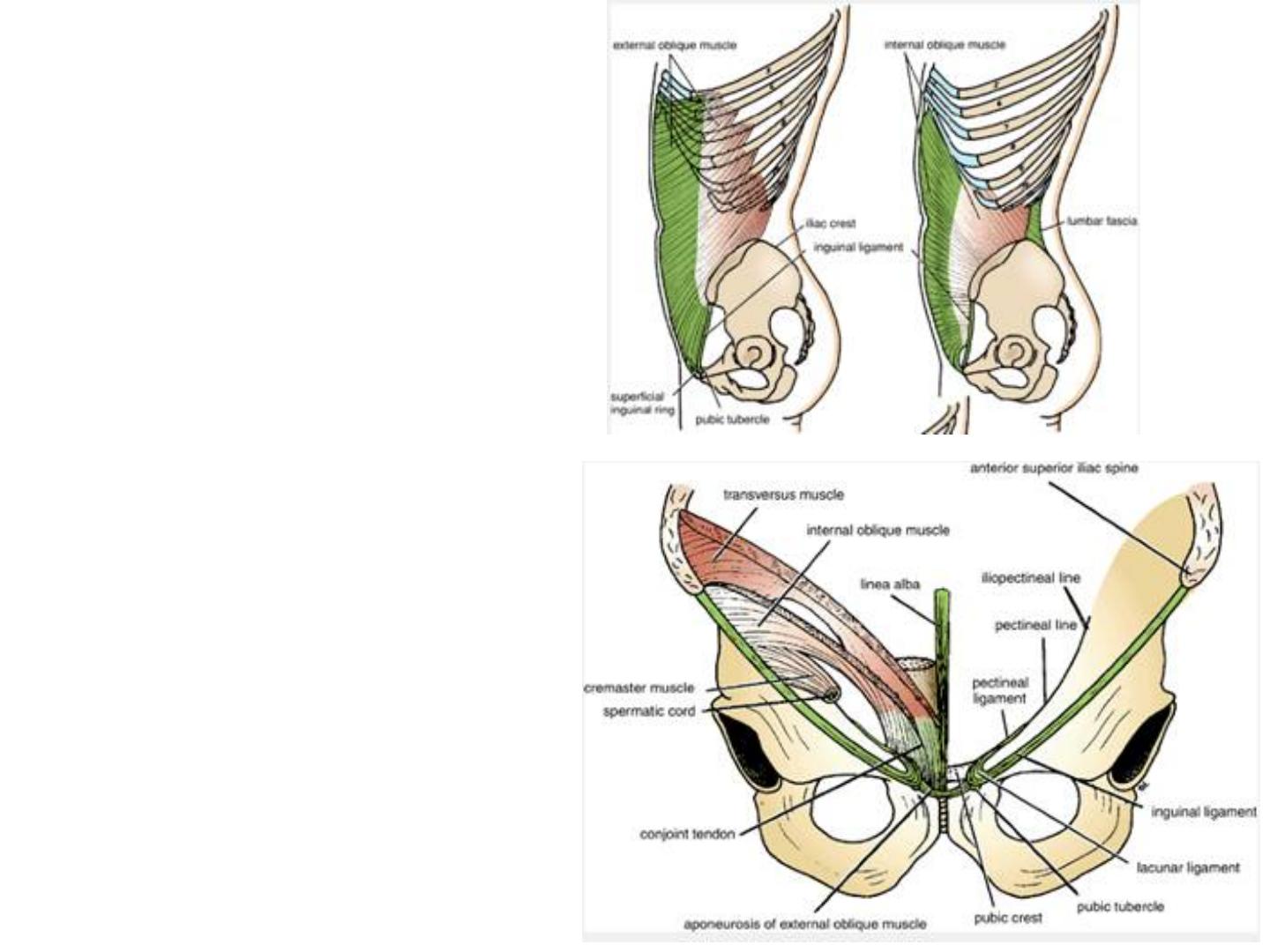

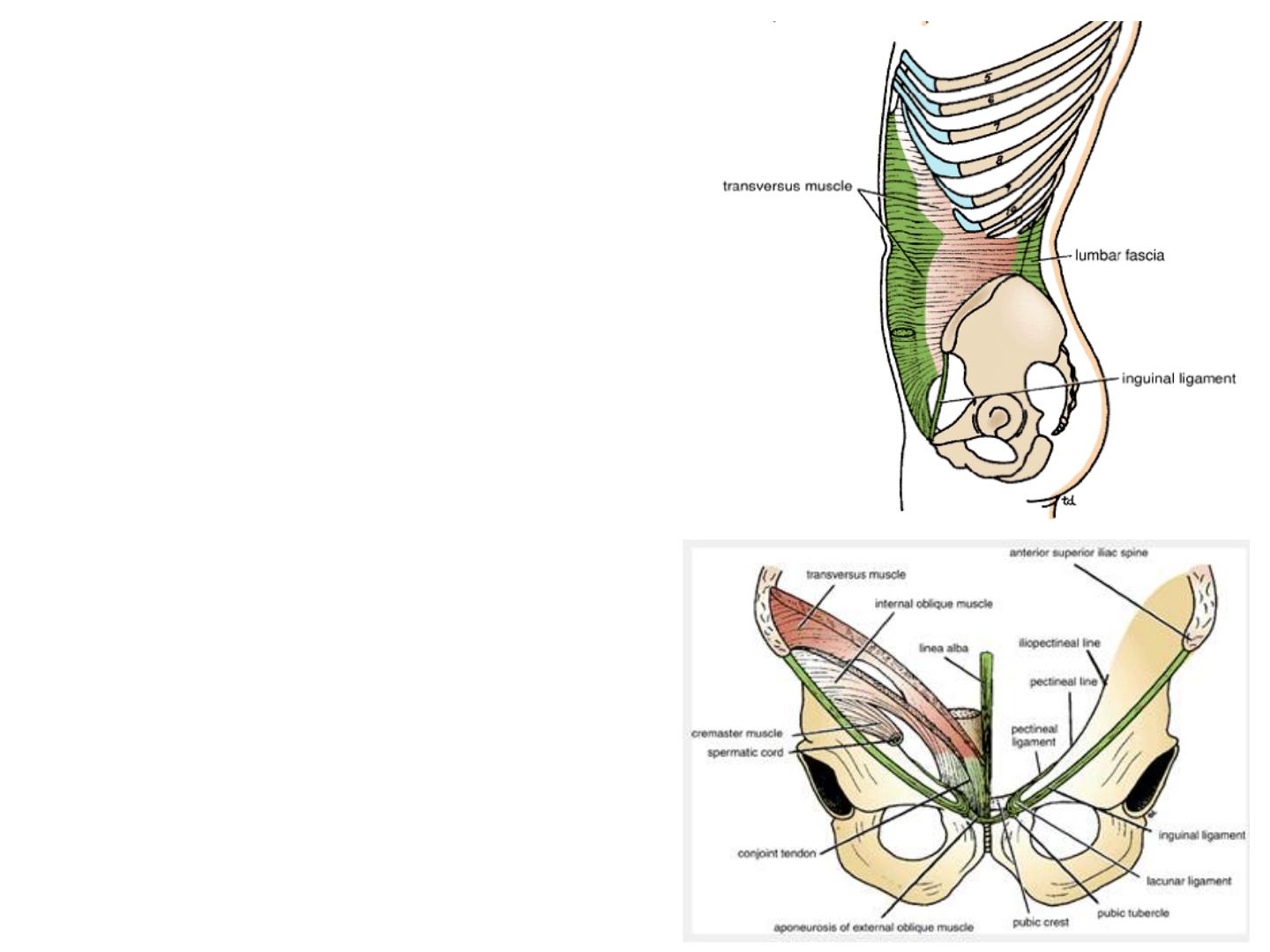

Internal Oblique

The internal oblique muscle is

also a broad, thin, muscular sheet

that lies deep to the external

oblique; most of its fibers run at

right angles to those of the

external oblique.

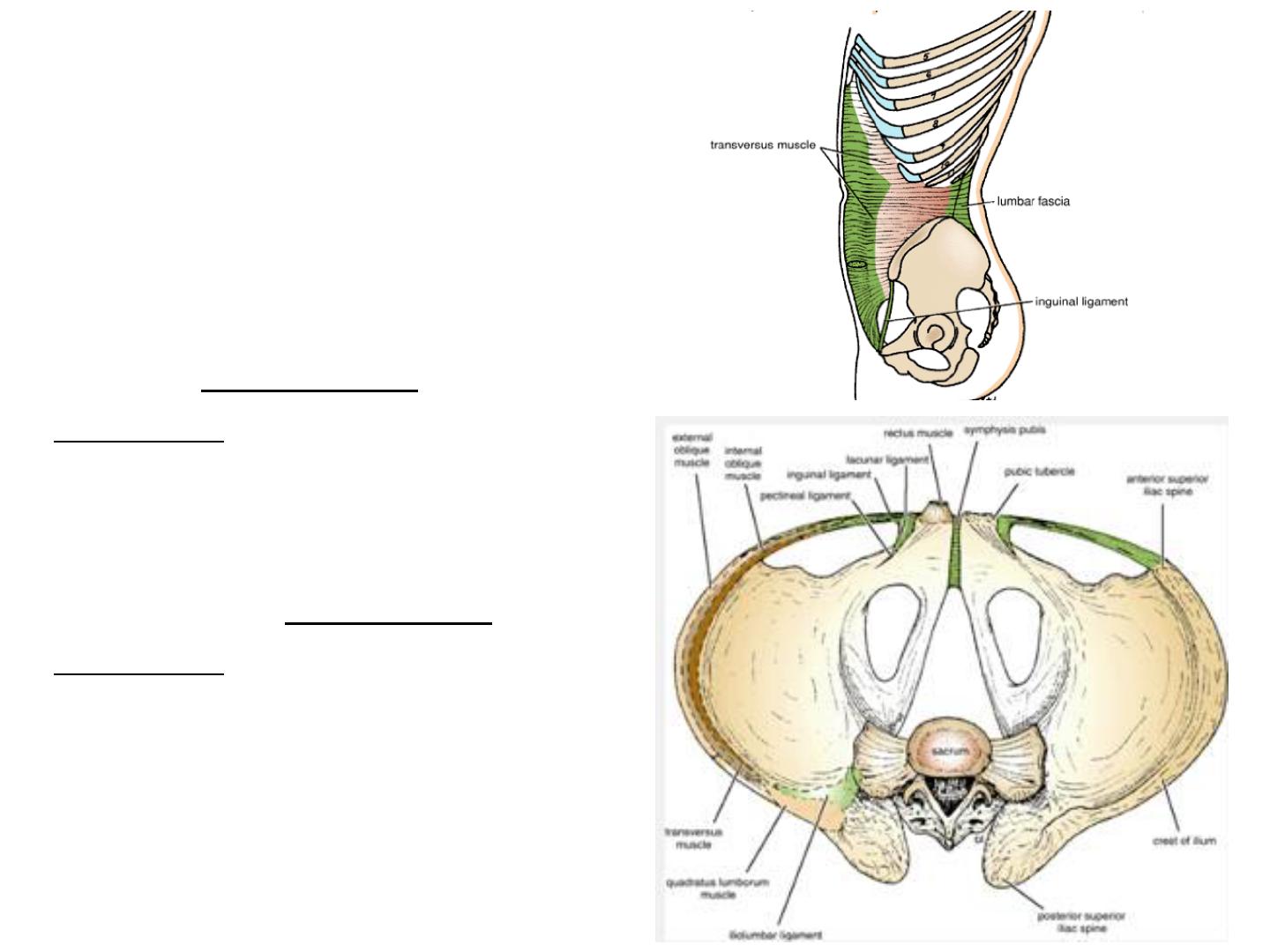

It arises from the lumbar fascia,

the anterior two thirds of the

iliac crest, and the lateral two

thirds of the inguinal ligament.

The muscle fibers radiate as they

pass upward and forward. The

muscle is inserted into the lower

borders of the lower three ribs

and their costal cartilages, the

xiphoid process, the linea alba,

and the symphysis pubis.

The internal oblique

has a lower free border

that arches over the

spermatic cord (or

round ligament of the

uterus) and then

descends behind it to be

attached to the pubic

crest and the pectineal

line. Near their

insertion, the lowest

tendinous fibers are

joined by similar fibers

from the transversus

abdominis to form the

conjoint tendon.

The conjoint tendon is attached

medially to the linea alba, but it

has a lateral free border.

As the spermatic cord (or

round ligament of the uterus)

passes under the lower border of

the internal oblique, it carries

with it some of the muscle fibers

that are called the cremaster

muscle. The cremasteric fascia

is the term used to describe the

cremaster muscle and its fascia.

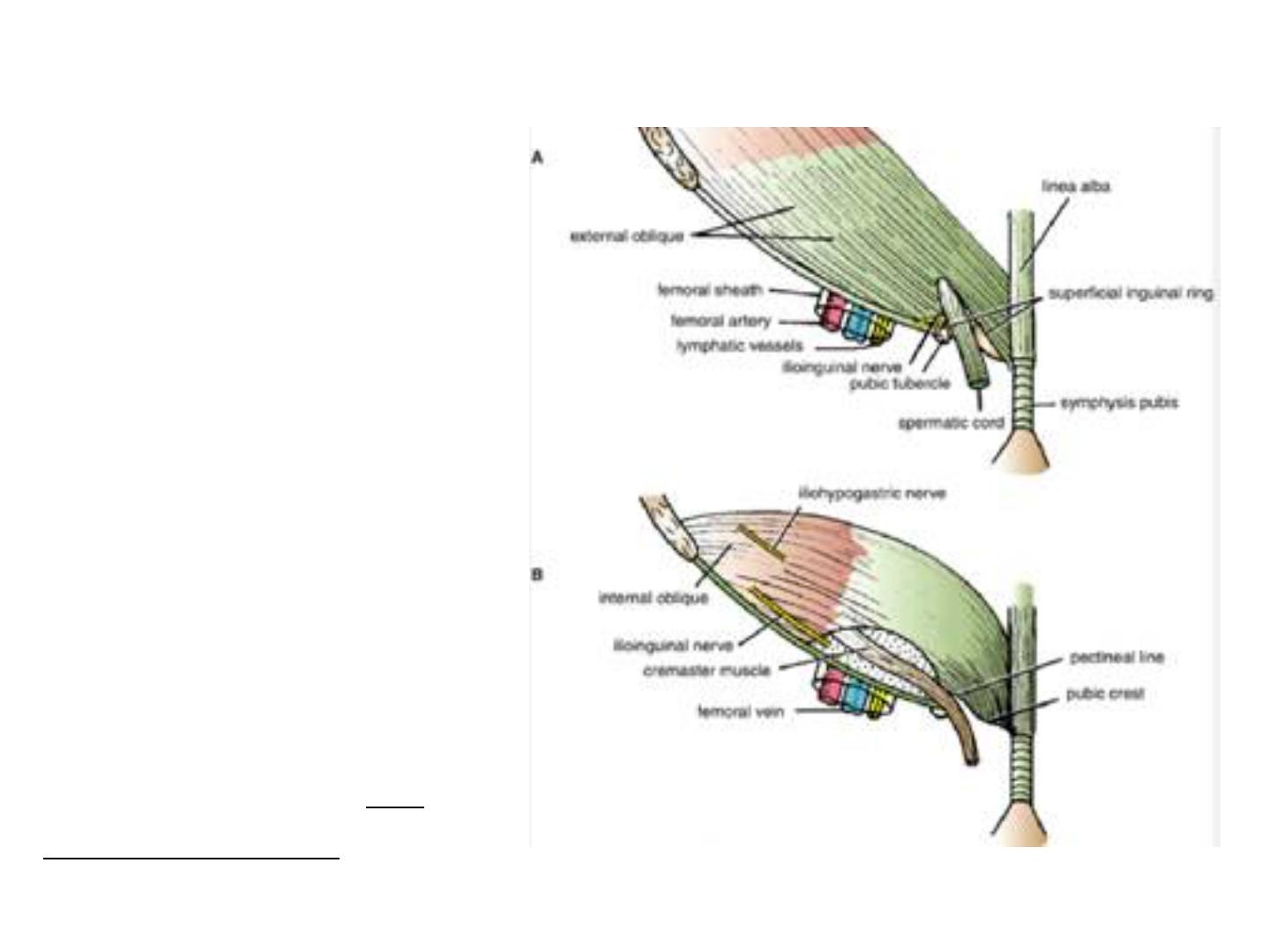

(D). Note that the anterior wall of the canal is formed by the

external oblique and the internal oblique and the posterior wall is

formed by the fascia transversalis and the conjoint tendon. The

deep inguinal ring lies lateral to the inferior epigastric artery.

Transversus

The transversus muscle is a thin

sheet of muscle that lies deep to the

internal oblique, and its fibers run

horizontally forward.

It arises from the deep surface of

the lower six costal cartilages

(interdigitating with the

diaphragm), the lumbar fascia,

the anterior two thirds of the

iliac crest, and the lateral third of

the inguinal ligament. It is

inserted into the xiphoid process,

the linea alba, and the symphysis

pubis. The lowest tendinous fibers

join similar fibers from the internal

oblique to form the conjoint

tendon, which is fixed to the pubic

crest and the pectineal line.

Note that the

posterior border

of the external

oblique muscle

is free, whereas

the posterior

borders of the

internal oblique

and transversus

muscles are

attached to the

lumbar

vertebrae by the

lumbar fascia.

Rectus Abdominis

The rectus abdominis is a

long strap muscle that

extends along the whole

length of the anterior

abdominal wall. It is

broader above and lies

close to the midline, being

separated from its fellow

by the linea alba. The

rectus abdominis muscle

arises by two heads, from

the front of the symphysis

pubis and from the pubic

crest.

It is inserted into the fifth,

sixth, and seventh costal

cartilages and the xiphoid

process.

When it contracts, its

lateral margin forms a

curved ridge that can be

palpated and often seen

and is termed the linea

semilunaris. This extends

from the tip of the ninth

costal cartilage to the

pubic tubercle.

Anterior view of the rectus abdominis muscle and the rectus sheath. Left: The anterior wall of

the sheath has been partly removed, revealing the rectus muscle with its tendinous intersections.

Right: The posterior wall of the rectus sheath is shown. The edge of the arcuate line is shown at

the level of the anterior superior iliac spine.

The rectus abdominis

muscle is divided into

distinct segments by three

transverse tendinous

intersections: one at the

level of the xiphoid process,

one at the level of the

umbilicus,

and one halfway between

these two. These

intersections are strongly

attached to the anterior wall

of the rectus sheath. The

rectus abdominis is

enclosed between the

aponeuroses of the external

oblique, internal oblique,

and transversus, which form

the rectus sheath.

Anterior view of the rectus abdominis muscle and the

rectus sheath. Left: The anterior wall of the sheath has

been partly removed, revealing the rectus muscle with

its tendinous intersections. Right: The posterior wall of

the rectus sheath is shown. The edge of the arcuate line

is shown at the level of the anterior superior iliac spine.

Pyramidalis

The pyramidalis

muscle is often

absent. It arises by its

base from the

anterior surface of

the pubis and is

inserted into the linea

alba. It lies in front

of the lower part of

the rectus abdominis.

Nerve Supply of Anterior Abdominal Wall Muscles

The oblique and transversus

abdominis muscles are

supplied by the lower six

thoracic nerves and the

iliohypogastric and

ilioinguinal nerves (L1).

The rectus muscle is

supplied by the lower six

thoracic nerves.

The pyramidalis is supplied

by the 12th thoracic nerve.

Name of Muscle

Origin

Insertion

Nerve Supply

Action

External oblique

Lower eight ribs

Xiphoid process, linea

alba, pubic crest, pubic

tubercle, iliac crest

Lower six thoracic

nerves and

iliohypogastric and

ilioinguinal nerves (L1)

Supports abdominal

contents; compresses

abdominal contents;

assists in flexing and

rotation of trunk; assists

inforced expiration,

micturition, defecation,

parturition, and

vomiting

Internal oblique

Lumbar fascia, iliac crest,

lateral two thirds of

inguinal ligament

Lower three ribs and

costal cartilages, xiphoid

process, linea alba,

symphysis pubis

Lower six thoracic

nerves and

iliohypogastric and

ilioinguinal nerves (L1)

As above

Transversus

Lower six costal

cartilages, lumbar fascia,

iliac crest, lateral third of

inguinal ligament

Xiphoid process linea

alba, symphysis pubis

Lower six thoracic

nerves and

iliohypogastric and

ilioinguinal nerves (L1)

Compresses abdominal

contents

Rectus abdominis

Symphysis pubis and

pubic crest

Fifth, sixth, and seventh

costal cartilages and

xiphoid process

Lower six thoracic

nerves

Compresses abdominal

contents and flexes

vertebral column;

accessory muscle of

expiration

Pyramidalis (if present) Anterior surface of pubis Linea alba

12th thoracic nerve

Tenses the linea alba

Table 4-1 Muscles of the Anterior Abdominal Wall

Fascia Transversalis

The fascia transversalis

is a thin layer of fascia

that lines the transversus

abdominis muscle and is

continuous with a

similar layer lining the

diaphragm and the

iliacus muscle.

The femoral sheath

for the femoral vessels

in the lower limbs is

formed from the fascia

transversalis and the

fascia iliaca that covers

the iliacus muscle.

Clinical Notes

Abdominal Muscles, Abdominothoracic Rhythm, and Visceroptosis

The abdominal muscles contract and relax with respiration, and the

abdominal wall conforms to the volume of the abdominal viscera. There

is an abdominothoracic rhythm. Normally, during inspiration, when the

sternum moves forward and the chest expand, the anterior abdominal

wall also moves forward. If, when the chest expands, the anterior

abdominal wall remains stationary or contracts inward, it is highly

probable that the parietal peritoneum is inflamed and has caused a

reflex contraction of the abdominal muscles.

The shape of the anterior abdominal wall depends on the tone of its

muscles. A middle-aged woman with poor abdominal muscles who has

had multiple pregnancies is often incapable of supporting her abdominal

viscera. The lower part of the anterior abdominal wall protrudes

forward, a condition known as visceroptosis. This should not be confused

with an abdominal tumor such as an ovarian cyst or with the excessive

accumulation of fat in the fatty layer of the superficial fascia.

Extraperitoneal Fat

The extraperitoneal

fat is a thin layer of

connective tissue

that contains a

variable amount of

fat and lies

between the fascia

transversalis and

the parietal

peritoneum.

Parietal Peritoneum

The walls of the

abdomen are

lined with

parietal

peritoneum. This

is a thin serous

membrane and is

continuous below

with the parietal

peritoneum lining

the pelvis.

Clinical Notes

Abdominal Pain

Muscle Rigidity and Referred Pain

Sometimes it is difficult for a physician to decide whether the muscles of the

anterior abdominal wall of a patient are rigid because of underlying

inflammation of the parietal peritoneum or whether the patient is voluntarily

contracting the muscles because he or she resents being examined or because

the physician's hand is cold. This problem is usually easily solved by asking the

patient, who is lying supine on the examination table, to rest the arms by the

sides and draw up the knees to flex the hip joints.

A pleurisy involving the lower costal parietal pleura causes pain in the

overlying skin that may radiate down into the abdomen. Although it is unlikely

to cause rigidity of the abdominal muscles, it may cause confusion in making a

diagnosis unless these anatomic facts are remembered.

It is useful to remember the following:

Dermatomes over:

•The xiphoid process: T7

•The umbilicus: T10

•The pubis: L1

Anterior Abdominal Nerve Block

Area of Anesthesia

The area of anesthesia is the skin of the anterior abdominal wall. The nerves of the

anterior and lateral abdominal walls are the anterior rami of the 7th through the 12th

thoracic nerves and the first lumbar nerve (ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves).

Indications

An anterior abdominal nerve block is performed to repair lacerations of the anterior

abdominal wall.

Procedure

The anterior ends of intercostal nerves T7 through T11 enter the abdominal wall by

passing posterior to the costal cartilages. An abdominal field block is most easily

carried out along the lower border of the costal margin and then infiltrating the nerves

as they emerge between the xiphoid process and the 10th or 11th rib along the costal

margin.

The ilioinguinal nerve passes forward in the inguinal canal and emerges through the

superficial inguinal ring. The iliohypogastric nerve passes forward around the

abdominal wall and pierces the external oblique aponeurosis above the superficial

inguinal ring. The two nerves are easily blocked by inserting the anesthetic needle 1 in.

(2.5 cm) above the anterior superior iliac spine on the spinoumbilical line.

Anterior abdominal wall nerve blocks. T7 though T11 are blocked (X) as they emerge

from beneath the costal margin. The iliohypogastric ilioinguinal nerves are blocked by

inserting the needle about 1 in. (2.5 cm) above the anterior superior iliac spine on the

spinoumbilical line (X). The terminal branches of the genitofemoral nerve are blocked

by inserting the needle through the skin just lateral to the pubic tubercle and infiltrating

the subcutaneous tissue with anesthetic solution (X).

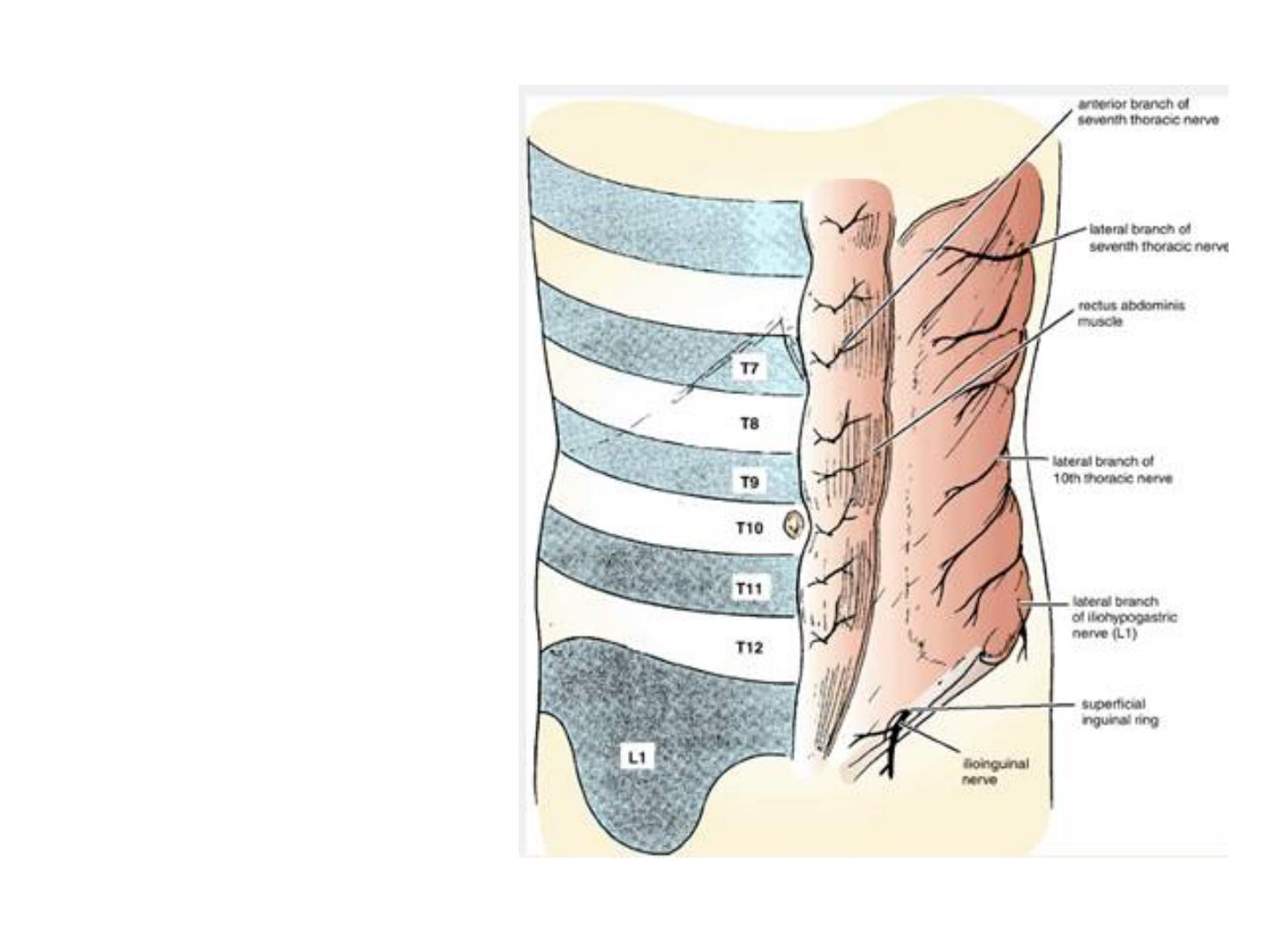

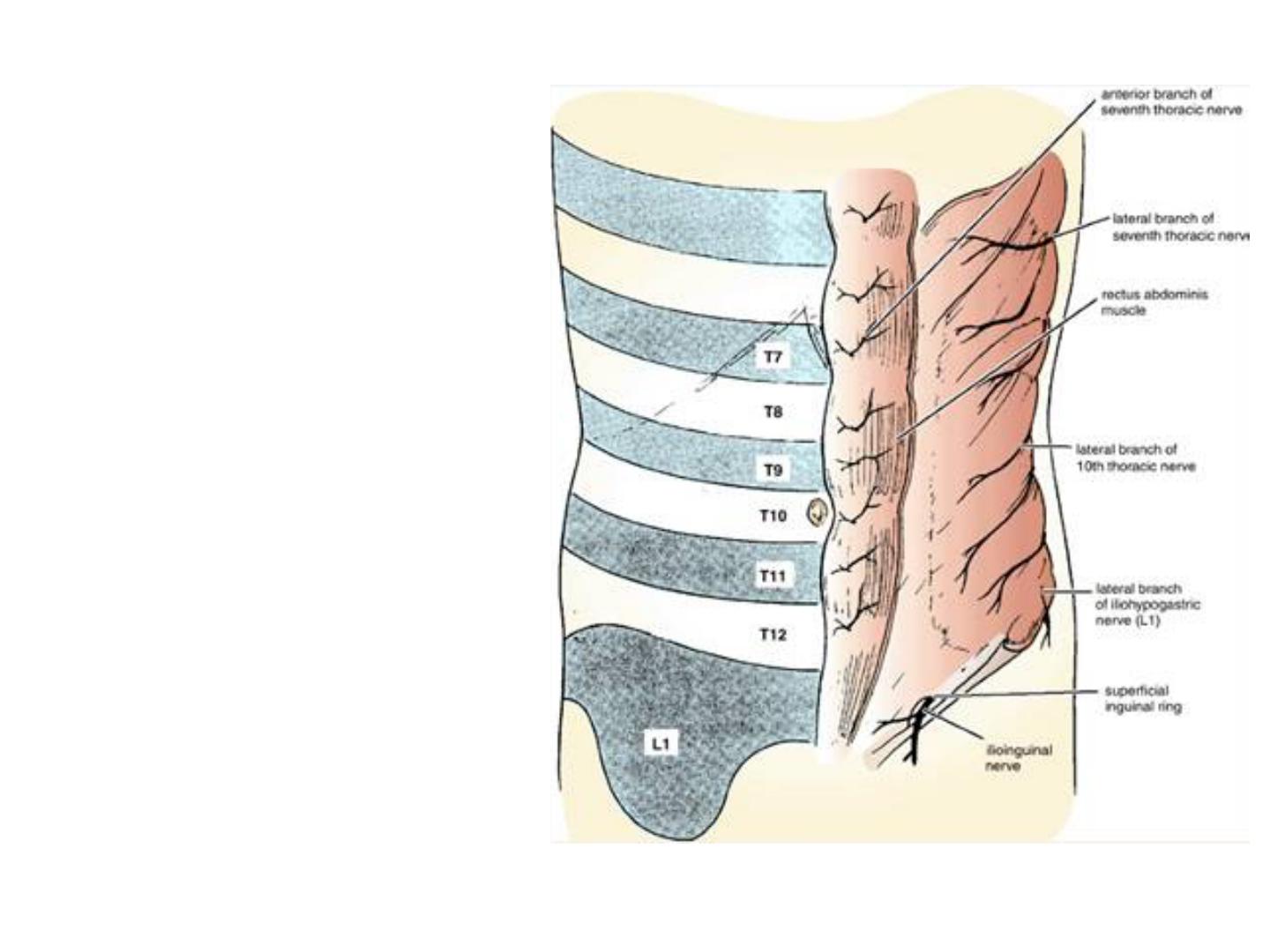

● The neurovascular supply of the anterolateral abdominal wall

The nerves of the anterior

abdominal wall are the anterior

rami of the lower six thoracic

and the first lumbar nerves.

They pass forward in the interval

between the internal oblique and

the transversus muscles. The

thoracic nerves are the lower five

intercostal nerves and the

subcostal nerves, and the first

lumbar nerve is represented by

the iliohypogastric and

ilioinguinal nerves, branches of

the lumbar plexus. They supply

the skin of the anterior

abdominal wall, the muscles, and

the parietal peritoneum.

Dermatomes and distribution of cutaneous

nerves on the anterior abdominal wall.

Nerves of the Anterior Abdominal Wall

The lower six thoracic

nerves pierce the

posterior wall of the

rectus sheath to supply

the rectus muscle and

the pyramidalis (T12

only). They terminate

by piercing the

anterior wall of the

sheath and supplying

the skin.

first lumbar nerve has a

similar course, but it does

not enter the rectus

sheath. It is represented

by the iliohypogastric

nerve, which pierces the

external oblique

aponeurosis above the

superficial inguinal

ring,

and by the ilioinguinal

nerve, which emerges

through the ring. They

end by supplying the skin

just above the inguinal

ligament and symphysis

pubis.

The dermatome of

T7 is located in

the epigastrium

over the xiphoid

process that of

T10 includes the

umbilicus, and that

of L1 lies just

above the inguinal

ligament and the

symphysis pubis.

For the

dermatomes of the

anterior abdominal

wall.

Arteries of the Anterior Abdominal Wall

The superior epigastric

artery, one of the

terminal branches of the

internal thoracic artery,

enters the upper part of

the rectus sheath between

the sternal and costal

origins of the diaphragm.

It descends behind the

rectus muscle, supplying

the upper central part of

the anterior abdominal

wall, and anastomoses

with the inferior

epigastric artery.

The inferior epigastric

artery is a branch of the

external iliac artery just

above the inguinal

ligament. It runs upward

and medially along the

medial side of the deep

inguinal ring. It pierces

the fascia transversalis to

enter the rectus sheath

anterior to the arcuate

line. It ascends behind the

rectus muscle, supplying

the lower central part of

the anterior abdominal

wall, and anastomoses

with the superior

epigastric artery.

The deep circumflex iliac

artery is a branch of the external

iliac artery just above the

inguinal ligament. It runs upward

and laterally toward the

anterosuperior iliac spine and

then continues along the iliac

crest. It supplies the lower lateral

part of the abdominal wall.

The lower two posterior

intercostal arteries, branches of

the descending thoracic aorta,

and the four lumbar arteries,

branches of the abdominal aorta,

pass forward between the muscle

layers and supply the lateral part

of the abdominal wall.

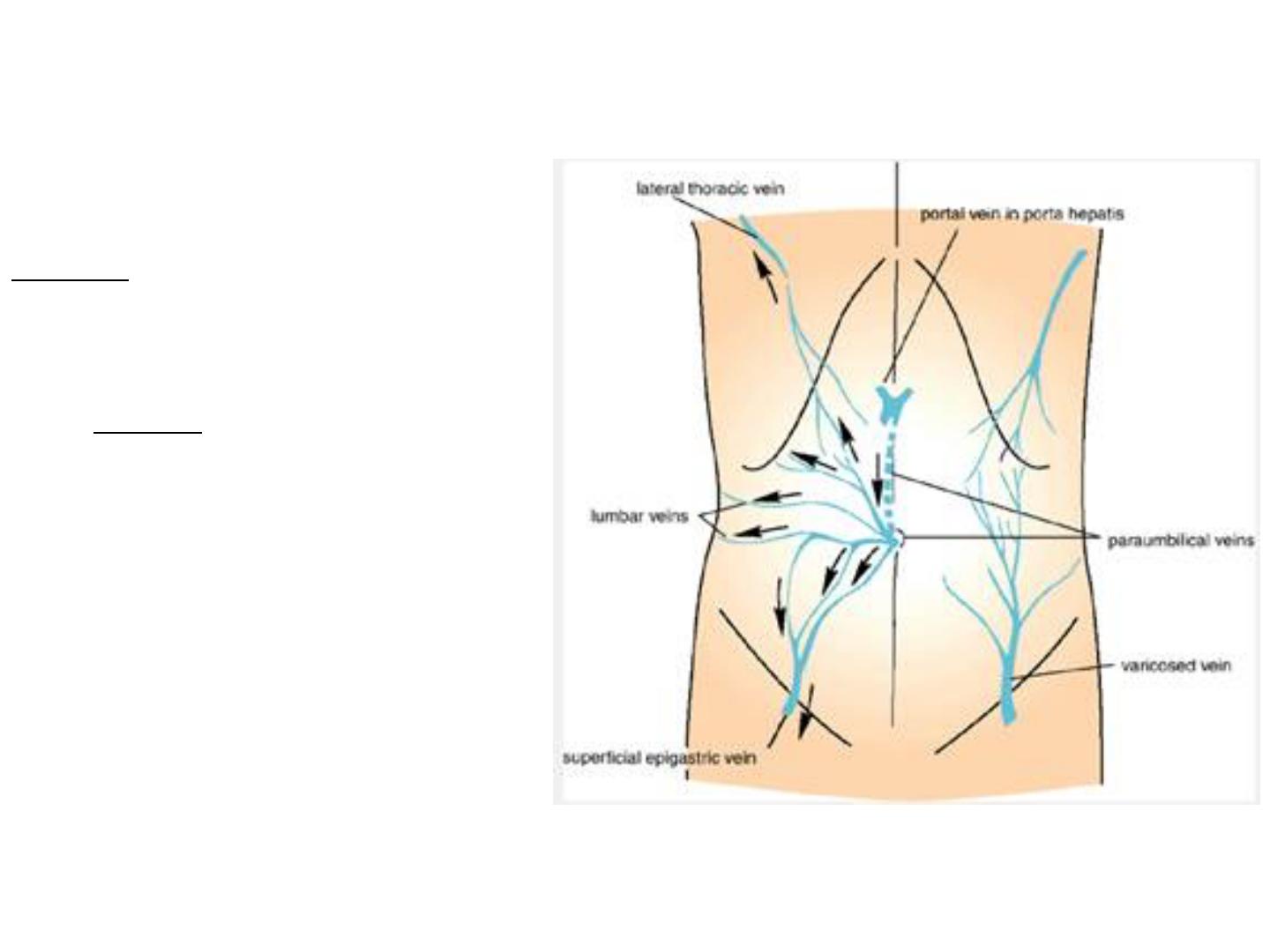

Veins of the Anterior Abdominal Wall Superficial

Veins

The superficial veins form a

network that radiates out

from the umbilicus.

Above, the network is

drained into the axillary vein

via the lateral thoracic vein

and, below, into the femoral

vein via the superficial

epigastric and great

saphenous veins. A few

small veins, the

paraumbilical veins, connect

the network through the

umbilicus and along the

ligamentum teres to the

portal vein. This forms an

important portal/systemic

venous anastomosis.

Clinical Notes

Portal Vein Obstruction

In cases of portal vein obstruction, the superficial veins around

the umbilicus and the paraumbilical veins become grossly

distended. The distended subcutaneous veins radiate out from the

umbilicus, producing in severe cases the clinical picture referred

to as caput medusae.

Deep Veins

The deep veins of the abdominal wall, the superior epigastric,

inferior epigastric, and deep circumflex iliac veins, follow the

arteries of the same name and drain into the internal thoracic

and external iliac veins. The posterior intercostal veins drain

into the azygos veins, and the lumbar veins drain into the

inferior vena cava.

Clinical Notes

Caval Obstruction

If the superior or inferior vena cava is obstructed, the venous

blood causes distention of the veins running from the anterior chest

wall to the thigh. The lateral thoracic vein anastomoses with the

superficial epigastric vein, a tributary of the great saphenous vein

of the leg. In these circumstances, a tortuous varicose vein may

extend from the axilla to the lower abdomen.

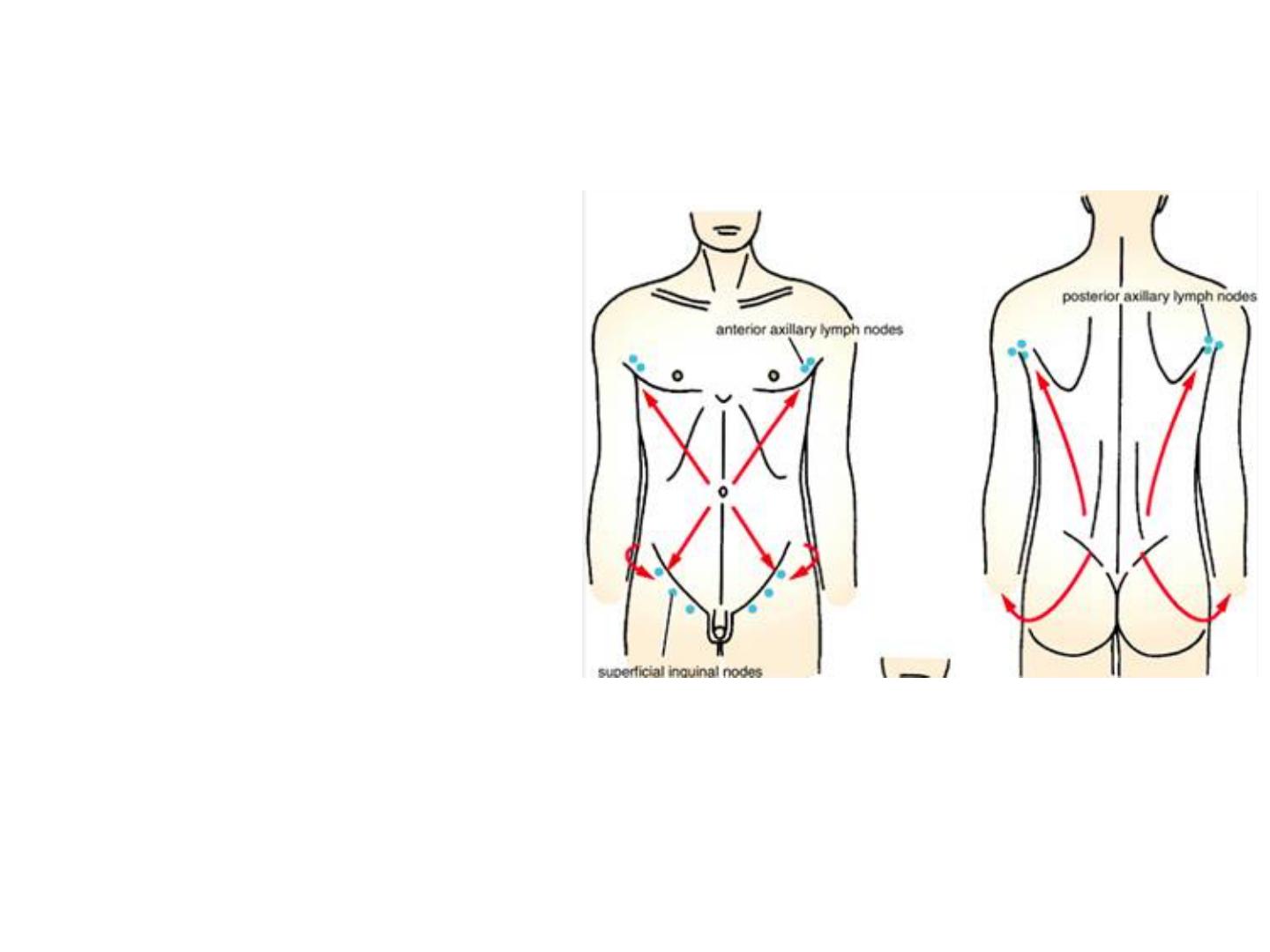

Lymph Drainage of the Anterior Abdominal Wall

Superficial Lymph Vessels

The lymph drainage of the skin of

the anterior abdominal wall above

the level of the umbilicus is upward

to the anterior axillary (pectoral)

group of nodes, which can be

palpated just beneath the lower

border of the pectoralis major

muscle. Below the level of the

umbilicus, the lymph drains

downward and laterally to the

superficial inguinal nodes. The

lymph of the skin of the back above

the level of the iliac crests is

drained upward to the posterior

axillary group of nodes, palpated on

the posterior wall of the axilla;

below the level of the iliac crests, it

drains downward to the superficial

inguinal nodes.

Lymph drainage of the skin of the

anterior and posterior abdominal walls.

Clinical Notes

Skin and Its Regional Lymph Nodes

For example, it is possible to find a swelling in the groin (enlarged

superficial inguinal node) caused by an infection or malignant

tumor of the skin of the lower part of the anterior abdominal wall or

that of the buttock.

Deep Lymph Vessels

The deep lymph vessels follow the arteries and drain into the

internal thoracic, external iliac, posterior mediastinal, and para-

aortic (lumbar) nodes.

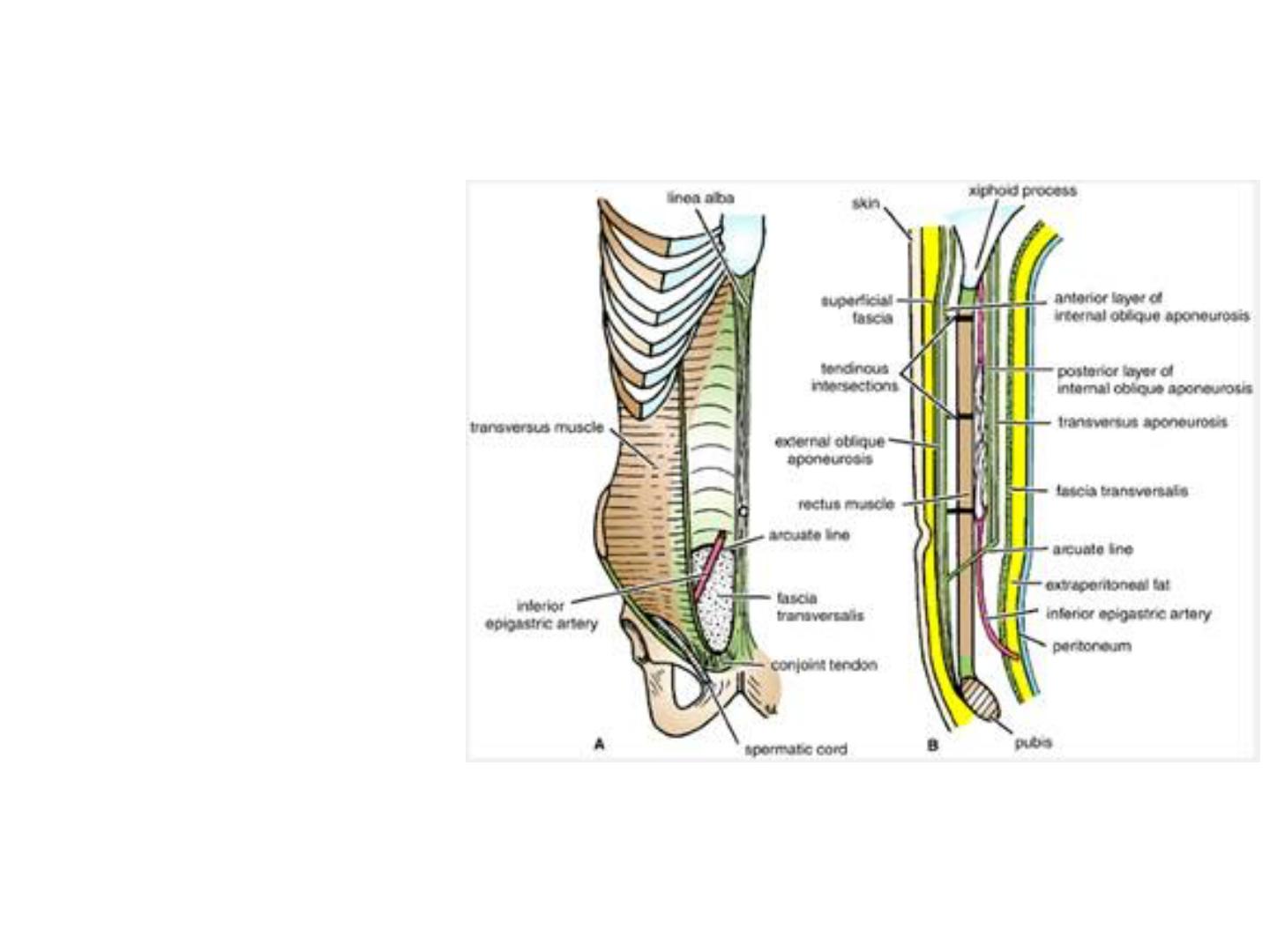

●The formation of the rectus sheath.

Anterior view of the rectus abdominis muscle and the rectus sheath. Left: The anterior

wall of the sheath has been partly removed, revealing the rectus muscle with its

tendinous intersections. Right: The posterior wall of the rectus sheath is shown. The

edge of the arcuate line is shown at the level of the anterior superior iliac spine.

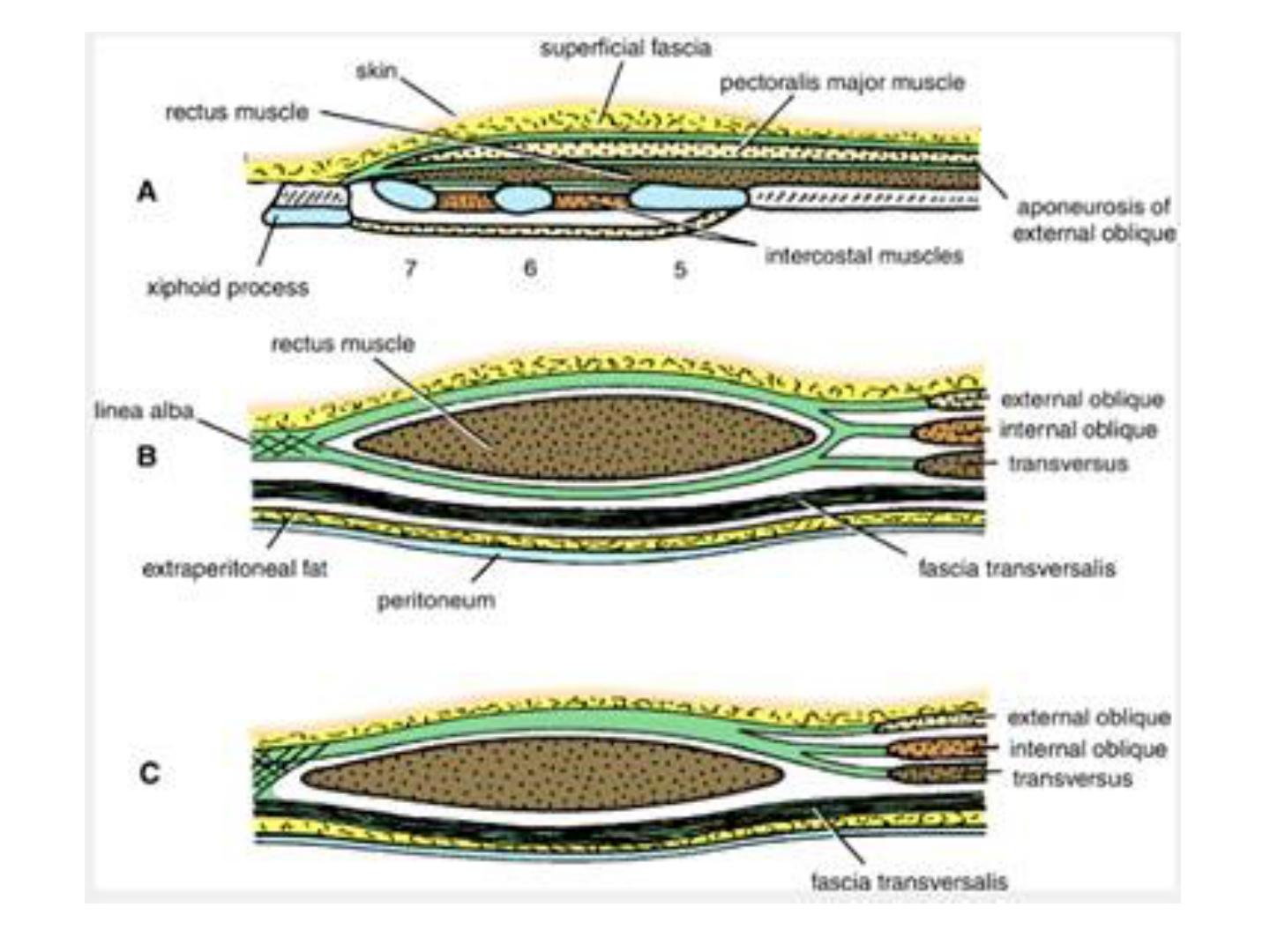

Rectus Sheath

The rectus sheath is a long

fibrous sheath that encloses the

rectus abdominis muscle and

pyramidalis muscle (if present)

and contains the anterior rami

of the lower six thoracic nerves

and the superior and inferior

epigastric vessels and lymph

vessels. It is formed mainly by

the aponeuroses of the three

lateral abdominal muscles.

For ease of description the rectus sheath is considered at three levels

•Above the costal margin, the anterior wall is formed by the aponeurosis of the external

oblique. The posterior wall is formed by the thoracic wall that is, the fifth, sixth, and seventh

costal cartilages and the intercostal spaces.

•Between the costal margin and the level of the anterior superior iliac spine, the

aponeurosis of the internal oblique splits to enclose the rectus muscle; the external oblique

aponeurosis is directed in front of the muscle, and the transversus aponeurosis is directed

behind the muscle.

•Between the level of the anterosuperior iliac spine and the pubis, the aponeuroses of all

three muscles form the anterior wall. The posterior wall is absent, and the rectus muscle lies

in contact with the fascia transversalis.

The posterior wall has a free, curved lower border called the arcuate line. At this site, the

inferior epigastric vessels enter the rectus sheath and pass upward to anastomose with the

superior epigastric vessels.

The rectus sheath is separated from its fellow on the opposite side by a fibrous band

called the linea alba. This extends from the xiphoid process down to the symphysis pubis

and is formed by the fusion of the aponeuroses of the lateral muscles of the two sides. Wider

above the umbilicus, it narrows down below the umbilicus to be attached to the symphysis

pubis.

The posterior wall of the rectus sheath is not attached to the rectus abdominis muscle. The

anterior wall is firmly attached to it by the muscle's tendinous intersections.

Clinical Notes

Hematoma of the Rectus Sheath

Hematoma of the rectus sheath is uncommon but important. It

occurs most often on the right side below the level of the

umbilicus. The source of the bleeding is the inferior epigastric

vein or, more rarely, the inferior epigastric artery. These vessels

may be stretched during a severe bout of coughing or in the

later months of pregnancy, which may predispose to the

condition. The cause is usually blunt trauma to the abdominal

wall, such as a fall or a kick.

● The “new” description of the anterior abdominal wall.

The arrangement of aponeuroses of the flat muscles of the anterolateral abdominal

wall:

1. The aponeurosis of each flat abdominal muscle is bilaminar.

2.Six laminae are formed, three pass anterior and three pass posterior to the rectus

abdominis down to the level of the umbilicus.

3. There are intramuscular and intermuscular fiber exchanges within the bilaminar

aponeurosis of the external and internal oblique muscles.

4. Intramuscular exchange of superficial and deep fibers within the aponeurosis of

conralateral external oblique muscle. Fibers of right external oblique aponeurosis

which run deep on the right side, running superficially on the left side.

5. Intermuscular exchange of fibers between aponeuroses of contralateral external

and inernal oblique muscles. Fibers of the right external oblique aponeurosis

blending with fibers of the left internal oblique aponeurosis.

6. Below the umbilicus there is gradual transition of the fibers from the posterior to

the anterior layer of the rectus sheath, rather than a sudden posterior to anterior

transition of the fibers at the arcuate line.

7. The formation of digastrics muscles.

8. The linea alba is a line of decussation rather than a line of insertion of the fibers

of the aponeuroses.

● Functional anatomy of the anterior abdominal wall

The oblique muscles laterally flex and

rotate the trunk. The rectus abdominis

flexes the trunk and stabilizes the

pelvis, and the pyramidalis keeps the

linea alba taut during the process.

The muscles of the anterior and

lateral abdominal walls assist the

diaphragm during inspiration by

relaxing as the diaphragm descends so

that the abdominal viscera can be

accommodated.

The muscles assist in the act of

forced expiration that occurs during

coughing and sneezing by pulling down

the ribs and sternum. By contracting

simultaneously with the diaphragm,

with the glottis of the larynx closed,

they increase the intra-abdominal

pressure and help in micturition,

defecation, vomiting, and parturition.