PNEUMONIA

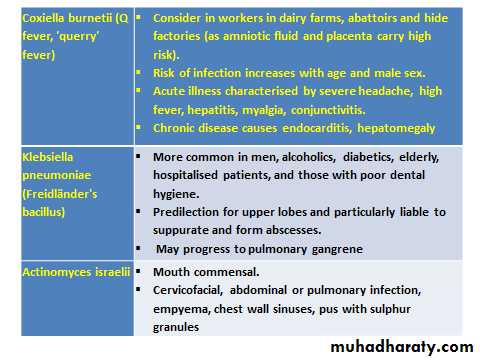

Dr.Redha 2012Pneumonia is defined as an acute respiratory illness associated with recently developed radiological pulmonary shadowing which may be segmental, lobar or multilobar.The context in which pneumonia develops is highly suggestive of the likely organism(s) involved; therefore, pneumonias are usually classified as community- or hospital-acquired, or those occurring in immunocompromised hosts. 'Lobar pneumonia 'is a radiological and pathological term referring to homogeneous consolidation of one or more lung lobes, often with associated pleural inflammation; bronchopneumonia refers to more patchy alveolar consolidation associated with bronchial and bronchiolar inflammation often affecting both lower lobes.

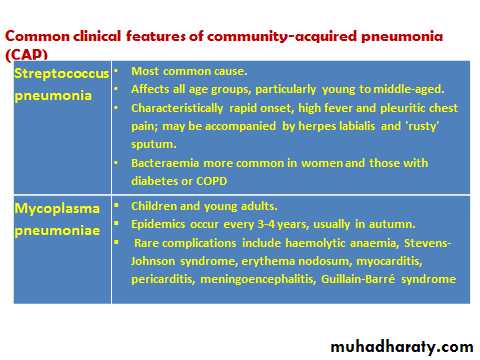

COMMUNITY-ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA (CAP)

UK figures suggest that an estimated 5-11/1000 adults suffer from CAP each year, accounting for around 5-12% of all lower respiratory tract infections.

The incidence varies with age, being much higher in the very young and very old, in whom the mortality rates are also much higher.

World-wide, CAP continues to kill more children than any other illness.

Most cases are spread by droplet infection and occur in previously healthy individuals but several factors may impair the effectiveness of local defenses and predispose to CAP (see below).

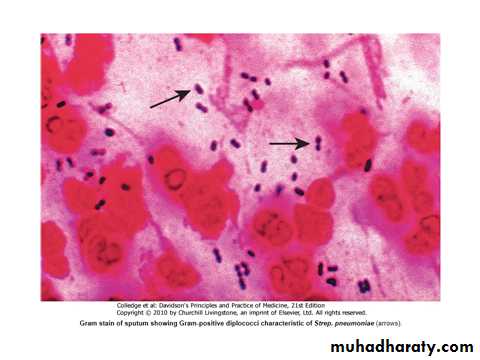

Strep. pneumonia (Fig.below) remains the most common infecting agent, and thereafter, the likelihood that other organisms may be involved depends on the age of the patient and the clinical context.

Viral infections are an important cause of CAP in children, and their contribution to adult CAP is increasingly recognised.

Factors that predispose to pneumonia

• Cigarette smoking• Upper respiratory tract infections

• Alcohol

• Corticosteroid therapy

• Old age

• Recent influenza infection

• Pre-existing lung disease

• HIV

• Indoor air pollution

Clinical features

Pneumonia usually presents as an acute illness in which systemic features such as fever, rigors, shivering and vomiting predominate (see Box below).

The appetite is usually lost and headache is common.

Pulmonary symptoms include breathlessness and cough, which at first is characteristically short, painful and dry, but later accompanied by the expectoration of mucopurulent sputum.

Rust-coloured sputum may be seen in patients with Strep. pneumoniae infection, and the occasional patient may report haemoptysis.

Pleuritic chest pain may be a presenting feature and on occasion may be referred to the shoulder or anterior abdominal wall.

Upper abdominal tenderness is sometimes apparent in patients with lower lobe pneumonia or if there is associated hepatitis.

Less typical presentations may be seen at the extremes of age.

Clinical signs reflect the nature of the inflammatory response.

Proteinaceous fluid and inflammatory cells congest the airspaces, leading to consolidation of lung tissue (which takes on the appearance of liver on a cut surface: phases of red, then grey hepatisation).

This improves the conductivity of sound to the chest wall and the clinician may hear bronchial breathing and whispering pectoriloquy

Crackles are often also detected.

Differential diagnosis of pneumonia

Pulmonary infarction

Pulmonary/pleural TB

Pulmonary oedema (can be unilateral)

Pulmonary eosinophilia

Malignancy: bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma

Rare disorders: cryptogenic organising pneumonia/bronchiolitis obliterans

organising pneumonia (COP/BOOP)

Investigations

The objectives are to exclude other conditions that mimic pneumonia (Box above), assess the severity, and identify the development of complications.

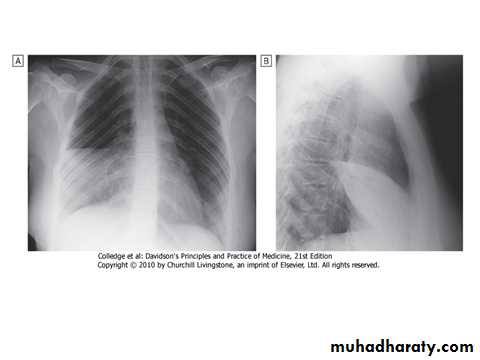

A chest X-ray:

Usually provides confirmation of the diagnosis. In lobar pneumonia, a homogeneous opacity localized to the affected lobe or segment usually appears within 12-18 hours of the onset of the illness (Fig. above). Radiological examination is helpful if a complication such as :Parapneumonic effusion.

Intrapulmonary abscess formation .

Empyema is suspected.

Many cases of CAP can be managed successfully without identification of the organism, particularly if there are no features indicating severe disease.

A full range of microbiological tests :

Should be performed on patients with severe CAP (Box below).

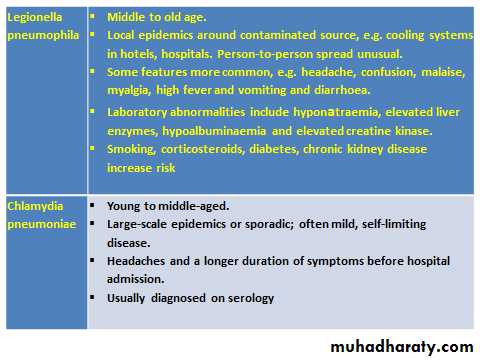

The identification of Legionella pneumophila has important public health implications and requires notification.

In patients who do not respond to initial therapy, microbiological results may allow its appropriate modification.

Microbiological investigations in patients with CAP

i- All patients

• Sputum: direct smear by Gram (see Fig. 19.30) and Ziehl-Neelsen stains. Culture and antimicrobial sensitivity testing

• Blood culture: frequently positive in pneumococcal pneumonia

• Serology: acute and convalescent titres for Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, Legionella, and viral infections. Pneumococcal antigen detection in serum or urine

• PCR: Mycoplasma can be detected from swab of oropharynx

With severe community-acquired pneumonia

The above tests plus consider:

•Tracheal aspirate, induced sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage, protected brush specimen or

percutaneous needle aspiration. Direct fluorescent antibody stain for Legionella and viruses

• Serology: Legionella antigen in urine. Pneumococcal antigen in putum and blood. Immediate

IgM for Mycoplasma

• Cold agglutinins: positive in 50% of patients with Mycoplasma

ii- Selected patients

• Throat/nasopharyngeal swabs: helpful in children or during nfluenza epidemic

• Pleural fluid: should always be sampled when present in more than trivial amounts, preferably with ultrasound guidance

Pulse oximetry :

provides a non-invasive method of measuring arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) and monitoring response to oxygen therapy. An arterial blood gas is important in those with SaO2 < 93% or with features of severe pneumonia, to identify ventilatory failure or acidosis.

The white cell count:

may be normal or only marginally raised in pneumonia caused by atypical organisms, whereas a neutrophil leukocytosis of more than 15 × 109/L favours a bacterial Aetiology. A very high (> 20 × 109/l) or low (< 4 × 109/l) white cell count may be seen in severe pneumonia.

Urea and electrolytes and liver function tests should also be checked.

The C-reactive protein (CRP) is typically elevated.

Assessment of disease severity

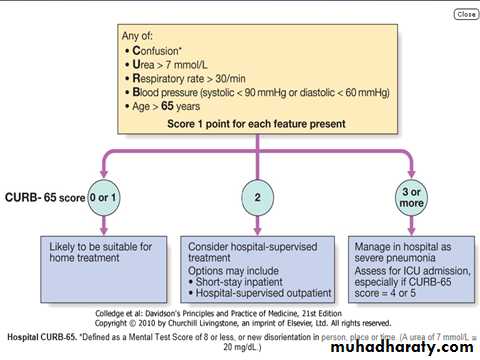

This is best assessed by an experienced clinician; however, the CURB-65 scoring system helps guide antibiotic and admission policies, and gives useful prognostic information (Fig. later).

Management

The most important aspects of management include oxygenation, fluid balance and antibiotic therapy. In severe or prolonged illness, nutritional support may be required.1-Oxygen

Oxygen should be administered to all patients with tachypnoea, hypoxaemia, hypotension or acidosis with the aim of maintaining the PaO2 ≥ 8 kPa (60 mmHg) or SaO2 ≥ 92%.

High concentrations (≥ 35%), preferably humidified, should be used in all patients who do not have hypercapnia associated with COPD.

Assisted ventilation should be considered at an early stage in those who remain hypoxemic despite adequate oxygen therapy.

NIV may have a limited role but early recourse to mechanical ventilation is often more appropriate (Box below).

Indications for referral to ITU

CURB score 4-5 failing to respond rapidly to initial management

Persisting hypoxia (PaO2 < 8 kPa (60 mmHg)) despite high concentrations of oxygen

Progressive hypercapnia

Severe acidosis

Circulatory shock

Reduced conscious level

2-Fluid balance

Intravenous fluids should be considered in those with severe illness, in older patients and in those with vomiting.

Otherwise, an adequate oral intake of fluid should be encouraged.

Inotropic support may be required in patients with circulatory shock .

3-Antibiotic treatment

Prompt administration of antibiotics improves outcome.

The initial choice of antibiotic is guided by clinical context, severity assessment, local knowledge of antibiotic resistance patterns, and at times epidemiological information, e.g. during a mycoplasma epidemic (Box below).

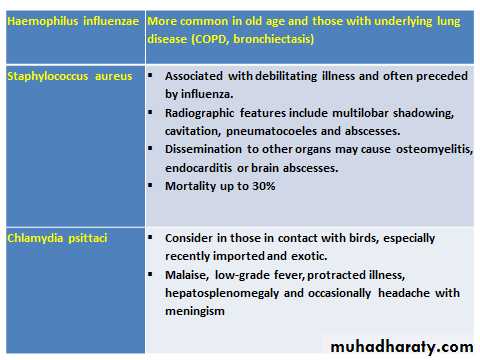

In most patients with uncomplicated pneumonia a 7-10-day course is adequate, although treatment is usually required for longer in patients with Legionella, staphylococcal or Klebsiella pneumonia.

Oral antibiotics are usually adequate unless the patient has severe illness, impaired consciousness, loss of swallowing reflex or malabsorption.

Antibiotic treatment for CAP*

Uncomplicated CAP

Amoxicillin 500 mg 8-hourly orally. If patient is allergic to penicillin

Clarithromycin 500 mg 12-hourly orally or erythromycin 500 mg 6-hourly orally

If Staphylococcus is cultured or suspected

Flucloxacillin 1-2 g 6-hourly i.v. plus clarithromycin 500 mg 12-hourly i.v.

If Mycoplasma or Legionella is suspected

Clarithromycin 500 mg 12-hourly orally or i.v. or Erythromycin 500 mg 6-hourly orally or i.v. plus rifampicin 600 mg 12-hourly i.v. in severe cases

Severe CAP

Clarithromycin 500 mg 12-hourly i.v. or erythromycin 500 mg 6-hourly i.v. plus co-amoxiclav 1.2 g 8-hourly i.v. or ceftriaxone 1-2 g daily i.v. or cefuroxime 1.5 g 8-hourly i.v. or Amoxicillin 1 g 6-hourly i.v. plus flucloxacillin 2 g 6-hourly i.v.

4-Treatment of pleural pain

It is important to relieve pleural pain, in order to allow the patient to breathe normally and cough efficiently. For the majority, simple analgesia with paracetamol, co-codamol or NSAIDs is sufficient.In some patients, opiates may be required but these must be used with extreme caution in patients with poor respiratory function.

5-Physiotherapy

Physiotherapy may be helpful to assist expectoration in patients who suppress cough because of pleural pain or when mucus plugging leads to bronchial collapse

Prognosis

Most patients respond promptly to antibiotic therapy. However, fever may persist for several days and the chest X-ray often takes several weeks or even months to resolve, especially in old age.

Delayed recovery suggests either that a complication has occurred (Box below) or that the diagnosis is incorrect (see DDX).

Alternatively, the pneumonia may be secondary to a proximal bronchial obstruction or recurrent aspiration.

The mortality rate in adults managed at home is very low (< 1%); hospital death rates are typically between 5 and 10%, but may be as high as 50% in severe illness.

Complications of pneumonia

Para-pneumonic effusion-common

Empyema

Retention of sputum causing lobar collapse

DVT and pulmonary embolism

Pneumothorax, particularly with Staph. aureus

Suppurative pneumonia/lung abscess

ARDS, renal failure, multi-organ failure

Ectopic abscess formation (Staph. aureus)

Hepatitis, pericarditis, myocarditis, meningoencephalitis

Pyrexia due to drug hypersensitivity

Discharge and follow-up

The decision to discharge a patient depends on home circumstances and the likelihood of complications.

A chest X-ray need not be repeated before discharge in those making a satisfactory clinical recovery.

Clinical review should be arranged around 6 weeks later and a chest X-ray obtained if there are persistent symptoms, physical signs or reasons to suspect underlying malignancy.

Prevention

The risk of further pneumonia is increased by smoking, so current smokers should be advised to stop.

Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination should be considered in selected patients (Box below).

Because of the mode of spread (see Box), Legionella pneumophila has important public health implications and usually requires notification to the appropriate health authority.

In developing countries, tackling malnourishment and indoor air pollution, and encouraging immunisation against measles, pertussis and Haemophilus influenzae type b are particularly important in children

Influenza and pneumococcal vaccines in old age:

'Influenza vaccine reduces the risk of influenza and death in elderly people.‘

'Polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccines do not appear to reduce the incidence of pneumonia or death but may reduce the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease.'

END