1

Fifth stage

Psychiatry

Lec-9

.د

ال

ه

ا

م

20/11/2016

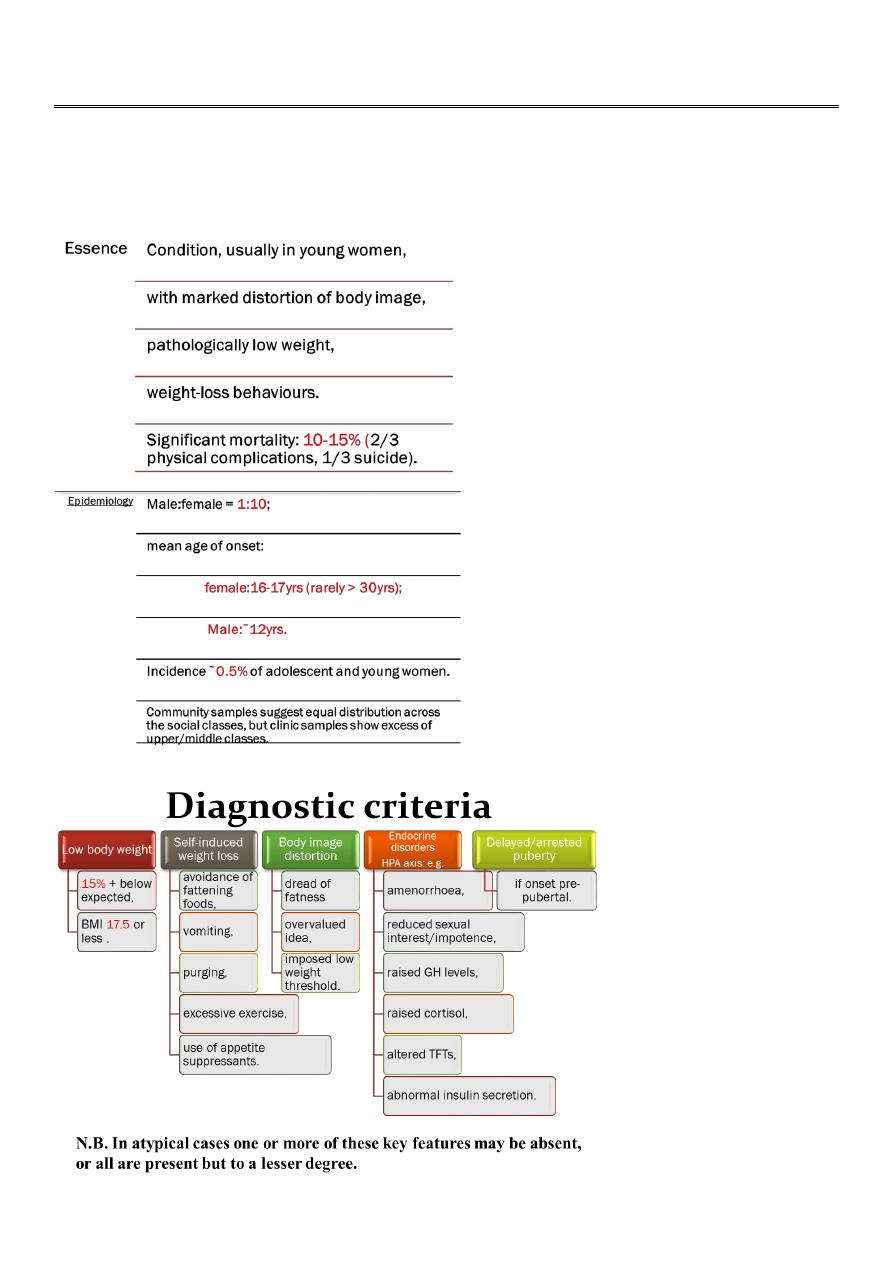

Eating disorder

Anorexia nervosa

2

Aetiology

• Genetic.

• concordance rates MZ:DZ = 65%:32%,

• female siblings: 6-10%

• Adverse life events

• no excess of childhood physical or sexual abuse (compared to psychiatric

controls)

• Psychodynamic models

• Biological

Psychodynamic models:

• Family pathology

• enmeshment,

• rigidity,

• overprotectiveness,

• lack of conflict resolution,

• weak generational boundaries.

• Individual pathology

• disturbed body image (due to dietary problems in early life,

• parents preoccupation with food,

• lack of a sense of identity).

3

• Analytical model

• regression to childhood,

• fixation on the oral stage,

• escape from the emotional problems of adolescence.

Biological:

• Hypothalamic dysfunction

• cause or consequence.

• Neuropsychological deficits

• reduced vigilance,

• attention,

• visuospatial abilities,

• associative memory (correct with weight gain).

• Brain imaging CT:

• pseudoatrophy sulcal widening and ventricular enlargement (correct with

weight gain).

• Functional imaging: unilateral temporal lobe hypoperfusion perhaps related to

visuospatial problems/body image distortion.

Differential diagnosis:

• Chronic debilitating physical disease

• Brain tumours

• GI disorders (e.g. Crohn's disease, malabsorption syndromes)

• Loss of appetite (may be secondary to drugs e.g. SSRIs, amfetamines)

• Depression/OCD (features of which may be associated)

4

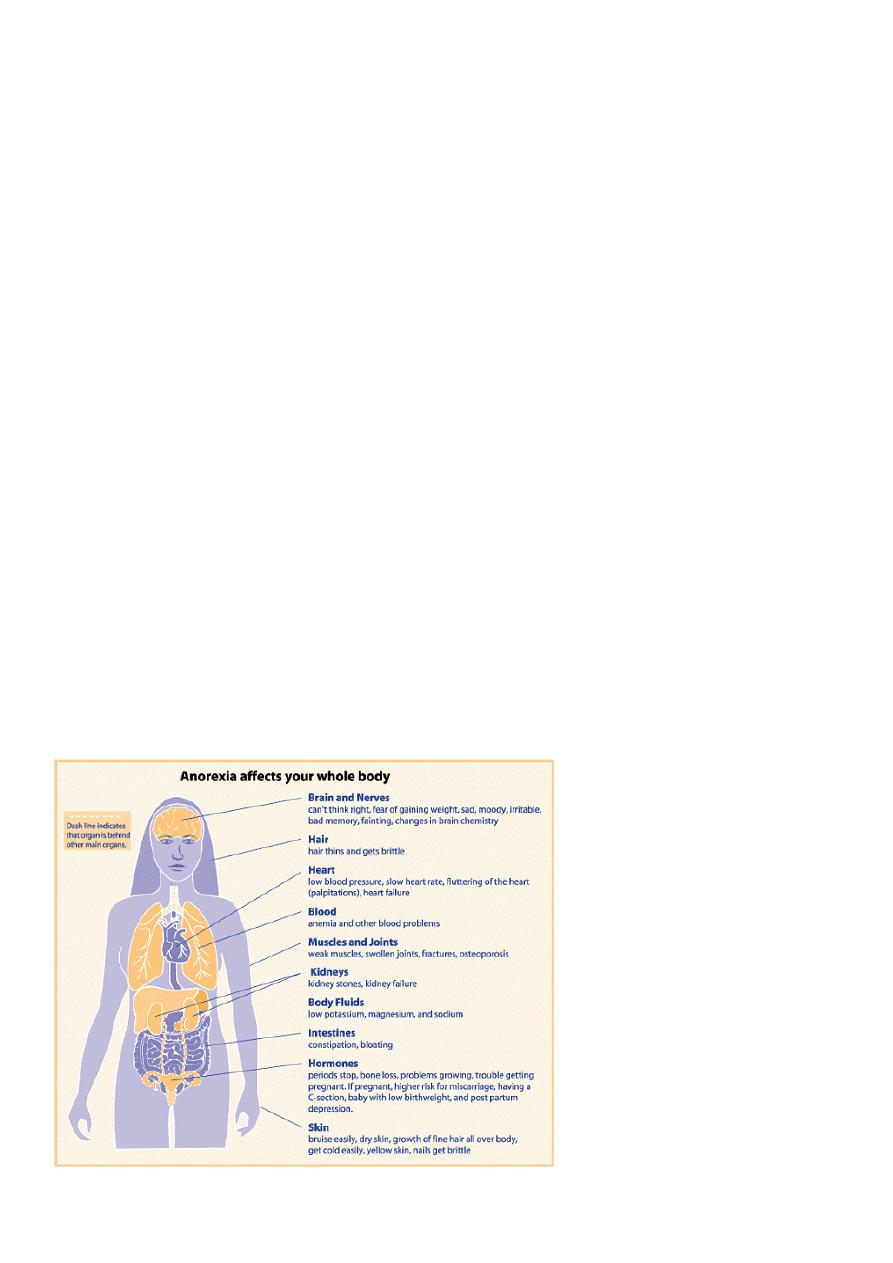

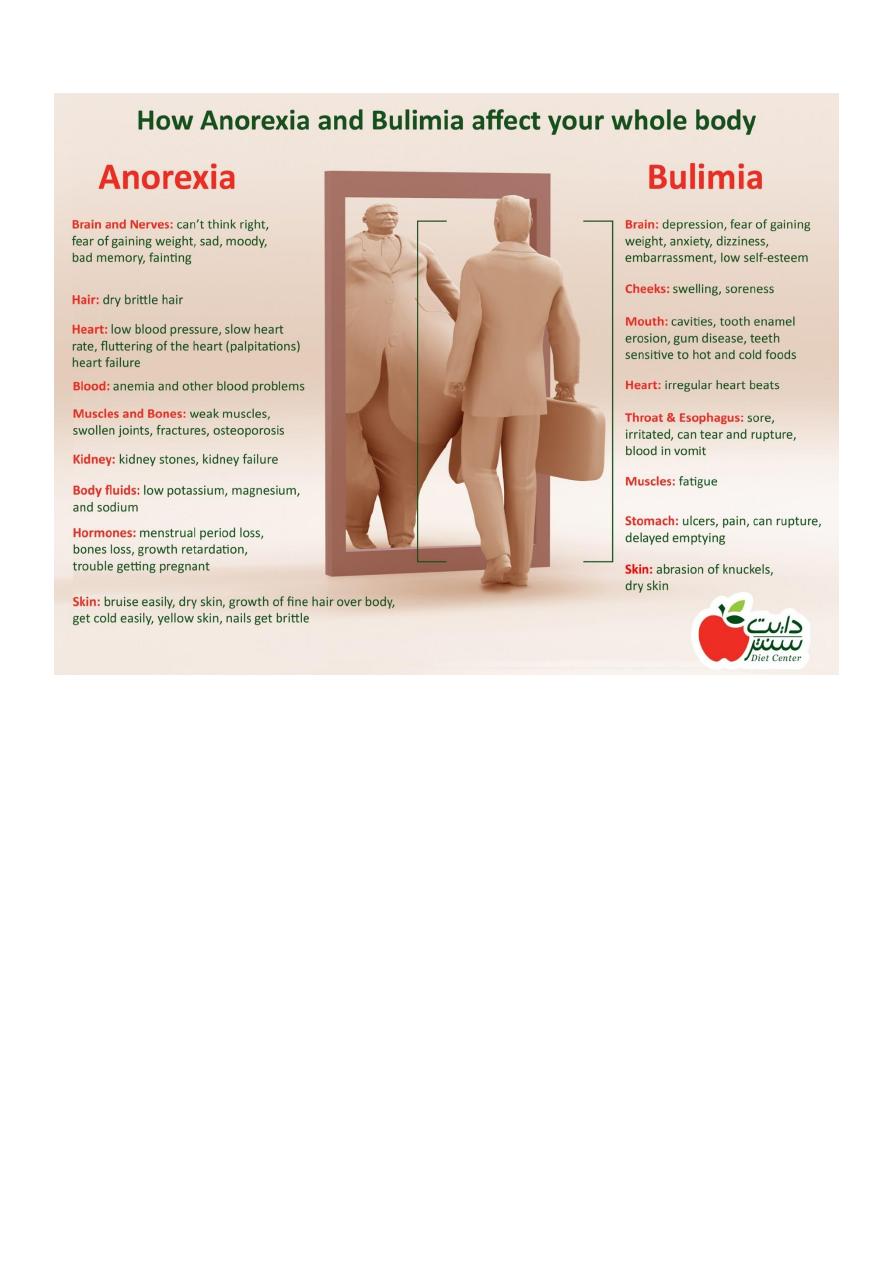

Physical consequences:

• Oral

• Dental caries.

• Cardiovascular

• Hypotension;

• prolonged QT;

• arrhythmias;

• cardiomyopathy.

• Gastrointestinal

• Prolonged GI transit (delayed gastric emptying, altered antral motility, gastric

atrophy, decreased intestinal mobility);

• constipation.

• N.B. Prokinetic agents may accelrrate gastric emptying and relieve gastric

bloating, which can accelerate resumption of normal eating habits.

• Renal

• Renal calculi.

• Reproductive

• Infertility;

• low birth-weight infant.

• Dermatological

• Dry scaly skin

• brittle hair (hair loss);

• lanugo (fine downy) body hair.

• Neurological

• Peripheral neuropathy;

• loss of brain volume: ventricular enlargement, sulcal widening, cerebral

atrophy, (pseudoatrophy”corrects with weight gain).

5

• Hematologic

• Anaemia;

• leucopaenia;

• thrombocytopaenia.

• Endocrine and metabolic

• Hypokalemia;

• hyponatremia;

• hypoglycemia;

• hypothermia;

• altered thyroid function;

• hypercortisolaemia;

• amenorrhea;

• delay in puberty;

• arrested growth;

• osteoporosis.

Cardiac complications

• The most common cause of death (mortality rate 10%).

• Findings may include

• Significant bradycardia (30-40bpm)

• Hypotension (systolic <70 mmHg)

• ECG changes (sinus bradycardia, ST-segment elevation, T wave flattening, low

voltage, and right axis deviation) may not be clinically significant unless there

are frequent arrhythmias (QT prolongation may indicate increased risk for

arrhythmias and sudden death).

• Echocardiogram may reveal decreased heart size, decreased left ventricular

mass (with associated abnormal systolic function), and mitral valve prolapse

(without significant mitral regurgitation). These changes reflect physiological

response to malnutrition and will recover on refeeding.

6

Amenorrhoea

• Included in the diagnostic criteria, due to

• hypothalamic dysfunction (hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis)

• low levels of FSH and LH,

• low levels of oestrogen (reversion to the prepubertal state occurs)

• LH response to GnRH blunted leading to amenorrhea.

• Consequences include

• Reduced fertility,

• multiple small follicles in the ovaries,

• decreased uterine volume, and atrophy.

• Note: amenorrhea can persist (in 5-44% of cases) even after recovery and return to

normal weight.

Osteopenia:

• Both cortical and trabecular bone are affected, and osteopenia persists despite

oestrogen therapy. Contributing to bone loss are

• low levels of progesterone

• decreased IGF-1 levels.

• Treatment

• No specific treatment exists; however, 1000-1500 mg/d of dietary calcium and

400 IU of vitamin D is recommended to prevent further bone loss and

maximize peak bone mass.

• Exercise and HRT, although of benefit in adult women, may be harmful for

adolescents with anorexia nervosa (causing premature closure of bone

epiphysis).

7

Physical signs

• loss of muscle mass

• dry skin

• brittle hair and nails

• callused skin over interphalangeal joints (Russell sign)

• anaemia

• hypercarotinemia (yellow skin and sclera)

• fine, downy, lanugo body hair

• eroded tooth enamel

• peripheral cyanosis

• hypotension

• bradycardia

• hypothermia

• atrophy of the breasts

• swelling of the parotid and submandibular glands

• swollen tender abdomen (intestinal dilatation due to reduced motility and

constipation)

• peripheral neuropathy

8

Assessment

• Full psychiatric history

• Establish the context in which the problems have arisen (to inform

development of a treatment plan).

• Confirm the diagnosis of an eating disorder.

• Assess risk of self-harm/suicide.

• Commonly reported psychiatric symptoms

• Concentration/memory/decision-making problems

• Irritability

• Depression

• Low self-esteem

• Loss of appetite

• Reduced energy

• Insomnia

• Loss of libido

• Social withdrawal

• Obsessiveness regarding food

• Full medical history

• Focus on the medical complications of altered nutrition .

• Detail weight changes, dietary patterns, and excessive exercise.

• Symptoms commonly elicited on systemic enquiry

• General physical health concerns

• Amenorrhoea

• Cold hands and feet

• Weight loss

• Constipation

• Dry skin

• Hair loss

9

• Headaches

• Fainting or dizziness

• Lethargy

Physical examination

• Determine weight and height (calculate BMI).

• Assess physical signs of starvation and vomiting .

• Routine and focused blood tests.

• ECG (and Echocardiogram if indicated).

Blood tests:

• FBC

• Hb usually normal or elevated (dehydration); if anaemic, investigate further.

• Leucopaenia and thrombocytopaenia seen.

• ESR

• Usually normal or reduced; if elevated, look for other organic cause of weight

loss.

• U&Es

• Raised urea and creatinine (dehydration),

• hyponatraemia (excessive water intake or SIADH neurogenic diabetes

insipidus, affecting 40%, may be treated with vasopressin, but is reversible

following weight gain),

• hypokalaemic /hypochloraemic metabolic alkalosis (from vomiting),

• metabolic acidosis (laxative abuse).

• hypocalcaemia,

• hypophosphataemia,

• hypomagnesaemia.

11

• Glucose

• Hypoglycaemia (prolonged starvation and low glycogen stores).

• LFTs

• Minimal elevation.

• TFTs

• Low T3/T4,

• increased rT3

• (euthyroid sick syndrome, an adaptive mechanism; hormonal replacement not

necessary; reverts to normal on re-feeding).

• Albumin/total protein

• Usually normal.

• Cholesterol

• May be dramatically elevated (starvation), secondary to decreased T3 levels,

• low cholesterol binding globulin,

• leakage of intrahepatic cholesterol.

• Endocrine

• Hypercortisolaemia,

• Increase GH levels,

• Decrease LHRH,

• Decrease LH,

• Decrease FSH,

• Decrease oestrogens,

• Decrease progestogens.

11

Management

Most patients will be treated as outpatients.

• A combined approach is better:

• Pharmacological

• Fluoxetine (especially if there are clear obsessional ideas regarding food);

• previously TCAs or chlorpromazine used for weight gain.

• Psychological

• Family therapy (more effective in early onset),

• individual therapy (behavioural therapy = CBT; may improve long-term

outcome).

• Education

• Nutritional education (to challenge overvalued ideas),

• self-help manuals (bibliotherapy).

• Hospital admission should only be considered if there are serious medical problems .

• Compulsory admission may be required: feeding is regarded as treatment

• (Note: Ethical issue regarding patient‘s right to die vs. their ˜right to

treatment).

• Criteria for admission to hospital

• Inpatient management may be necessary for patients with significant medical or

psychiatric problems:

• Extremely rapid or excessive weight loss that has not responded to outpatient

treatment.

• Severe electrolyte imbalance (life-threatening risks due to hypokalaemia or

hyponatraemia).

• Serious physiological complications, e.g. temperature < 36°C; fainting due to

bradycardia (PR < 45 bpm) and/or marked postural drop in BP.

• Cardiac complications or other acute medical disorders.

• Marked change in mental status due to severe malnutrition.

• Psychosis or significant risk of suicide.

12

• Failure of outpatient treatment (e.g. inability to break the cycle of disordered eating

or engage in effective outpatient psychotherapy).

• Admission should not be viewed as punishment by the patient and the goals of

inpatient therapy should be fully discussed with the patient (and their family):

• Addressing physical and/or psychiatric complications.

• Development of a healthy meal plan.

• Addressing underlying conflicts (e.g. low self-esteem, planning new coping

strategies).

• Enhancing communication skills.

Risks of re-feeding

• With re-feeding, cardiac decompensation may occur, especially during the first 2 wks

(when the myocardium cannot withstand the stress of an increased metabolic

demand).

• Symptoms include excessive bloating, oedema, and, rarely, congestive cardiac

failure (CCF).

• To limit these problems:

• Measure U&Es and correct abnormalities before re-feeding.

• Recheck U&Es every 3 days for the first 7 days and then weekly during re-

feeding period.

• Attempt to increase daily caloric intake slowly by 200-300 kcal every 3-5 days

until sustained weight gain of 1-2 pounds per week is achieved.

• Monitor patient regularly for development of tachycardia or oedema.

13

Prognosis

• If untreated, this condition carries one of the highest mortality figures for any

psychiatric disorder (10-15%).

• If treated, “rule of thirds” (1/3 full recovery, 1/3 partial recovery, 1/3 chronic

problems).

• Poor prognostic factors include:

• chronic illness

• late age of onset

• bulimic features (vomiting/purging)

• anxiety when eating with others

• excessive weight loss

• poor childhood social adjustment

• poor parental relationships

• male sex

Bulimia nervosa

Epidemiology

• Incidence 1-1.5% of women,

• mid-adolescent onset,

• presentation in early 20s.

14

Aetiology

• Similar to anorexia nervosa,

• also evidence for associated personal/family history of obesity,

• family history of affective disorder and/or substance misuse.

• Possible dysregulation of eating, related to serotonergic mechanisms

(?supersensitivity of 5HT2C secondary to decrease“5HT).

Diagnostic criteria

• Persistent preoccupation with eating

• Irresistible craving for food

• Binges episodes of overeating

• Attempts to counter the fattening effects of food (self-induced vomiting, abuse of

purgatives, periods of starvation, use of drugse e.g. appetite suppressants, thyroxine,

diuretics)

• Morbid dread of fatness, with imposed low weight threshold

N.B. In atypical cases, one or more of these features may be absent.

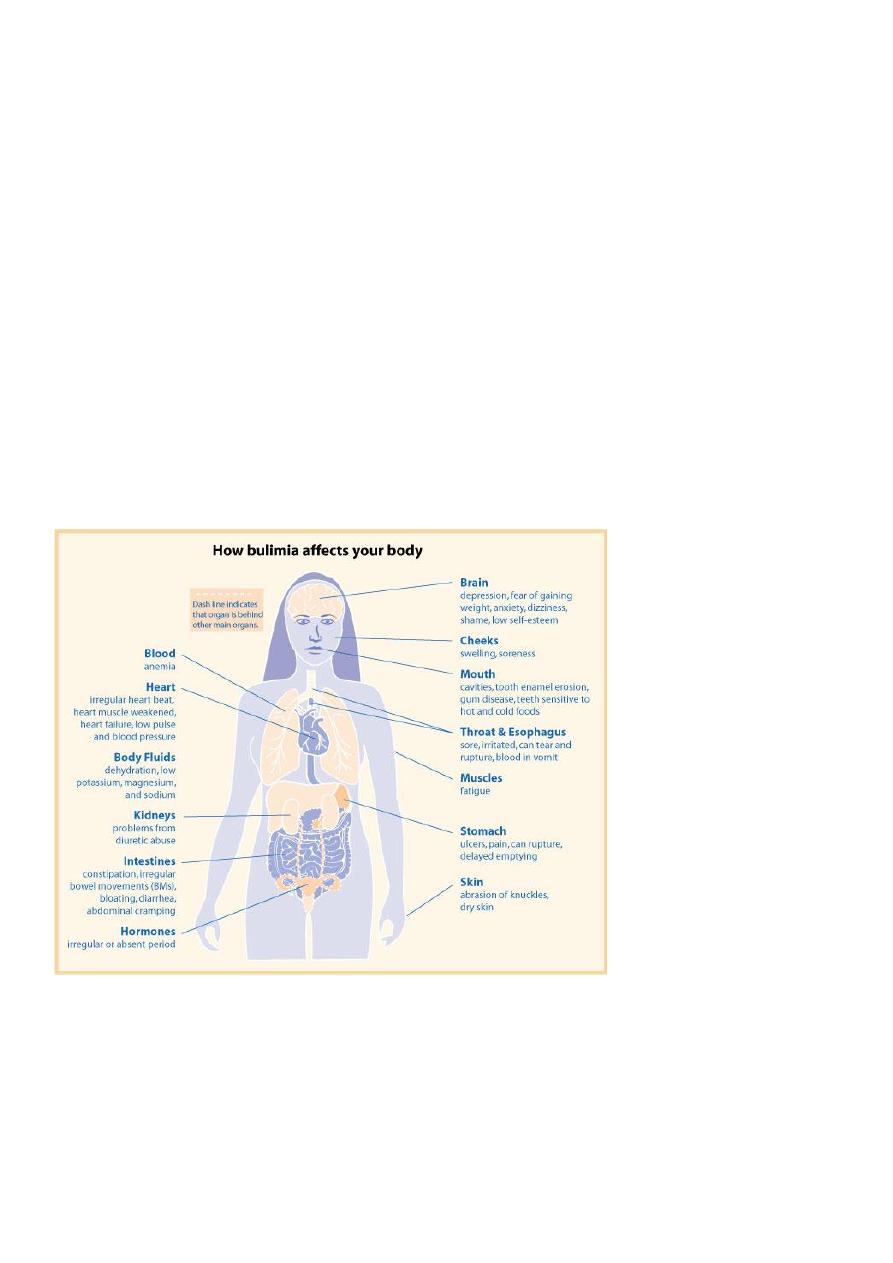

Physical signs

• May be similar to anorexia nervosa ; but tend to be less severe.

• Specific problems related to “purging “include:

• Arrhythmias

• Cardiac failure (sudden death)

• Electrolyte disturbances (decrease K

+

, decrease Na

+

, decrease Cl

-

, metabolic

acidosis [laxatives] or alkalosis [vomiting])

• Oesophageal erosions

• Oesophageal/gastric perforation

• Gastric/duodenal ulcers

• Pancreatitis

• Constipation/steatorrhea

15

• Dental erosion

• Leucopaenia/lymphocytosis.

Differential diagnosis

• Upper GI disorders (with associated vomiting)

• Brain tumours

• Personality disorder

• Depressive disorder

• OCD

• Drug-related increased appetite

• Other causes of recurrent overeating (e.g. menstrual-related syndromes, Kleine-Levin

syndrome.

16

Comorbidity

• Anxiety/mood disorder

• Multiple dyscontrol behaviours e.g.:

• Cutting/burning

• Overdose

• Alcohol/drug misuse

• Promiscuity

• Other impulse disorders

Treatment

• General principles

• Full assessment (as for anorexia nervosa).

• Usually managed as an outpatient.

• Admission only for suicidality, physical problems, extreme refractory cases, or

if pregnant (due to increased risk of spontaneous abortion).

• Combined approaches improve outcome.

• Pharmacological

• Most evidence for high-dose SSRIs (fluoxetine 60mg) long-term treatment

necessary (>1yr).

• Psychotherapy

• Best evidence for CBT.

• IPT may be as effective long-term, but acts less quickly.

• Guided self-help is a useful first step (e.g. bibliotherapy), with education and

support often in a group setting.

Prognosis

Generally good, unless there are significant issues of low self-esteem or evidence of severe

personality disorder.

17