All pediatrics

seminars

For

6

th

stage

Content

Topics:

Page:

Acute Diarrhoea in Children

3

The edematous child

18

Pyrexia of unknown origin

27

Vaccination

30

Acute respiratory infection

51

ARI control and prevention

57

Neonatal emergencies

62

Seminar1

: Acute Diarrhoea in Children

Welcome to the module on Management of Acute Diarrhoea (AD) in Children!

Diarrhoeal disease remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality amongst children in

low and middle income countries.

Most deaths result from the associated shock, dehydration and electrolyte imbalance.

In malnutrition, the risk of AD, its complications and mortality are increased.

How to use this module:

This module aims to address deficiencies in the management of AD and dehydration in

children that we identified during a clinical audit.

We suggest that you start with the learning objectives and try to keep these in mind as

you go through the module slide by slide, in order and at your own pace.

Print-out the diarrhoea SDL answer sheet. Write your answers to the questions (Q1, Q2

etc.) on the sheet as best you can before looking at the answers.

Repeat the module until you have achieved a mark of >20 (>80%).

You should research any issues that you are unsure about. Look in your textbooks,

access the on-line resources indicated at the end of the module and discuss with your

peers and teachers.

Finally, enjoy your learning! We hope that this module will be enjoyable to study and

complement your learning about AD from other sources.

Learning Outcomes:

By the end of this module, you should be competent in the management of acute diarrhoea

/ dehydration.

In particular you should be able to:

Describe when to use oral and parenteral fluids and what solutions to use

Identify the malnourished child and adjust management accordingly

Describe when antibiotic treatment is indicated and the adverse effects of the overuse

of antibiotics

Describe the use of zinc in AD

Definition of AD:

There is a wide range of normal stool patterns in children which makes the precise

definition of AD difficult

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), AD is the passage of loose* or

watery stools, three times or more in a 24 hour period for upto14 days

In the breastfed infant, the diagnosis is based on a change in usual stool frequency and

consistency as reported by the mother

AD must be differentiated from persistent diarrhoea which is of >14 days duration and

may begin acutely. Typically, this occurs in association with malnutrition and/or HIV

infection and may be complicated by dehydration

*Takes the shape of the container

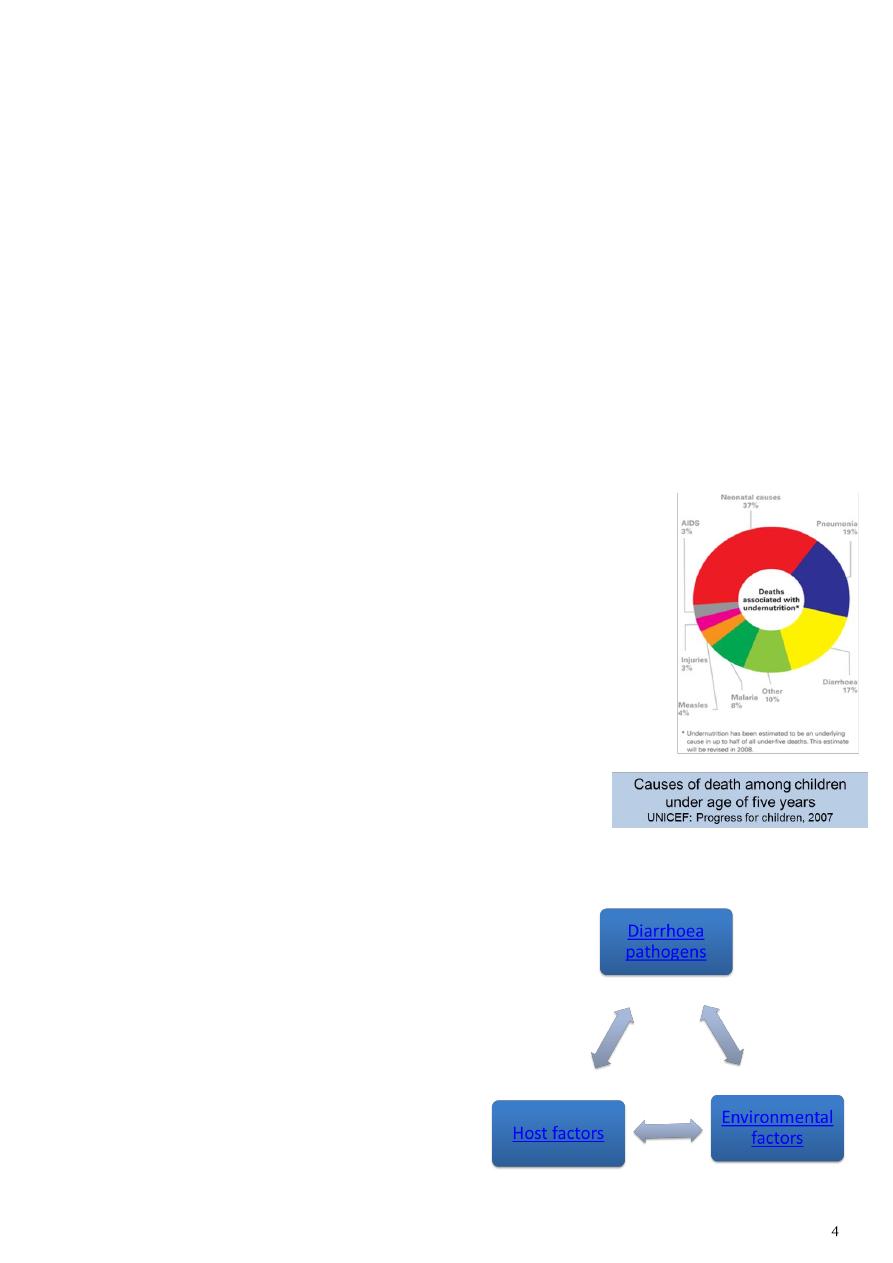

The burden of diarrhoeal disease:

Despite the fact that diarrhoea can be prevented, about 2

billion cases of diarrhoea occur globally every year in

children under 5 years

About 2 million child deaths occur due to diarrhoea every

year

More than 80% of these deaths are in Africa and South Asia

Diarrhoea is the third most common cause of death (see

diagram)

In Nigeria, diarrhoea causes 151,700 deaths of children

under five every year,* the second highest rate in the world

after India

* UNICEF/WHO, Diarrhoea: Why children are still dying and

what can be done, 2009

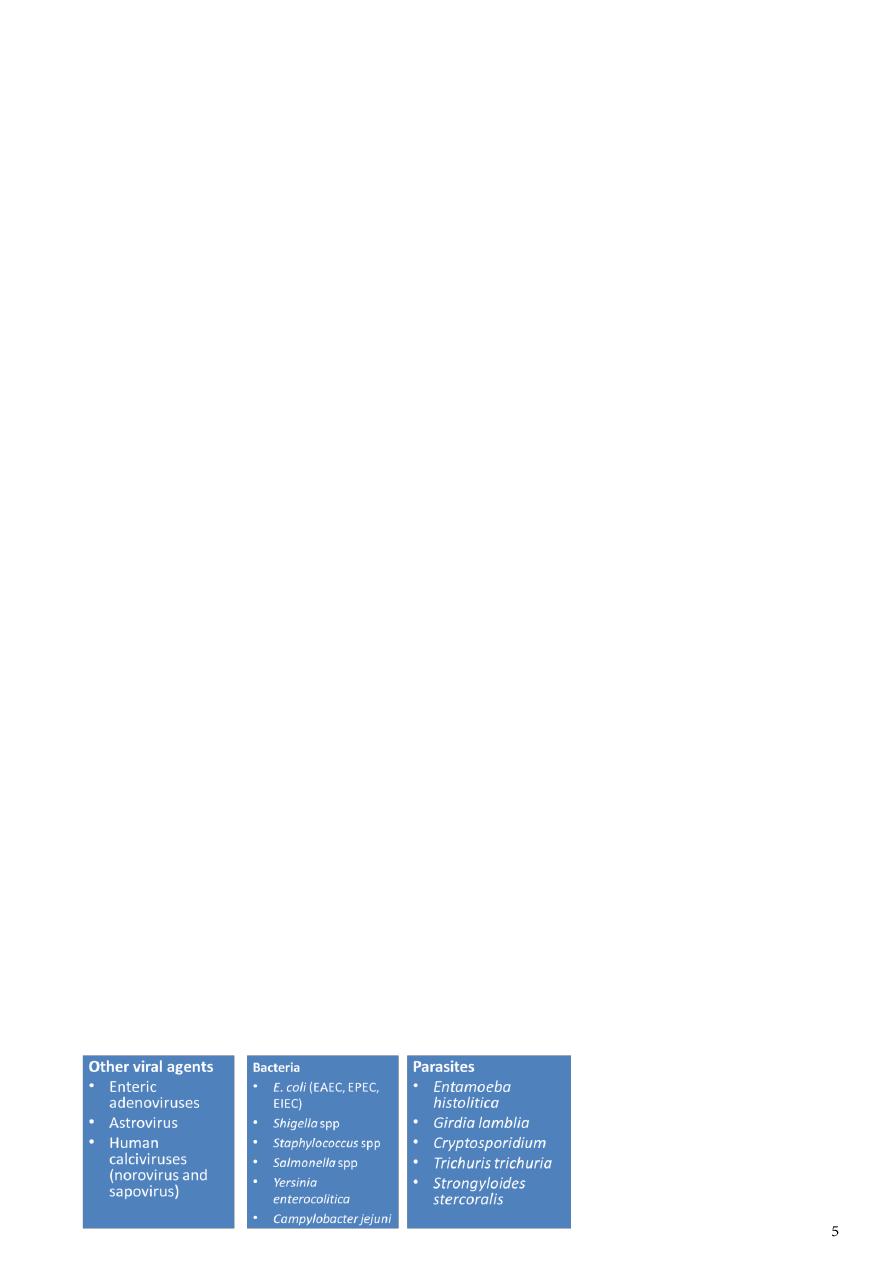

Causes and risk factors for AD:

Microbial, host and environmental factors

interact to cause AD

Click on the boxes to find out more

Host factors:

Biological factors increase susceptibility to AD:

Age: The incidence of AD peaks at around age 6-11 months, remains high through 24

months and then decreases

Failure to get immunised against rotavirus

Failure of measles vaccination; measles predisposes to diarrhoea by damage to the

intestinal epithelium and immune suppression

Malnutrition is associated with an increased incidence, severity and duration of diarrhea

Behavioral factors increase the risk of AD:

Not breastfeeding exclusively for 6 months

Using infant feeding bottles: they easily become contaminated with diarrhoea

pathogens and are difficult to clean

Not washing hands after defecation, handling faeces or before handling food

Environmental factors:

These include:

Seasonality: The incidence of AD has seasonal variation in many regions

o In temperate climates, viral diarrhoea peaks during winter whereas bacterial

diarhoea occurs more frequently during the warm season

o In tropical areas, viral and bacterial diarrhoeal occur throughout the year with

increased frequency during drier, cooler months.

Poor domestic and environmental sanitation especially unsafe water

Poverty

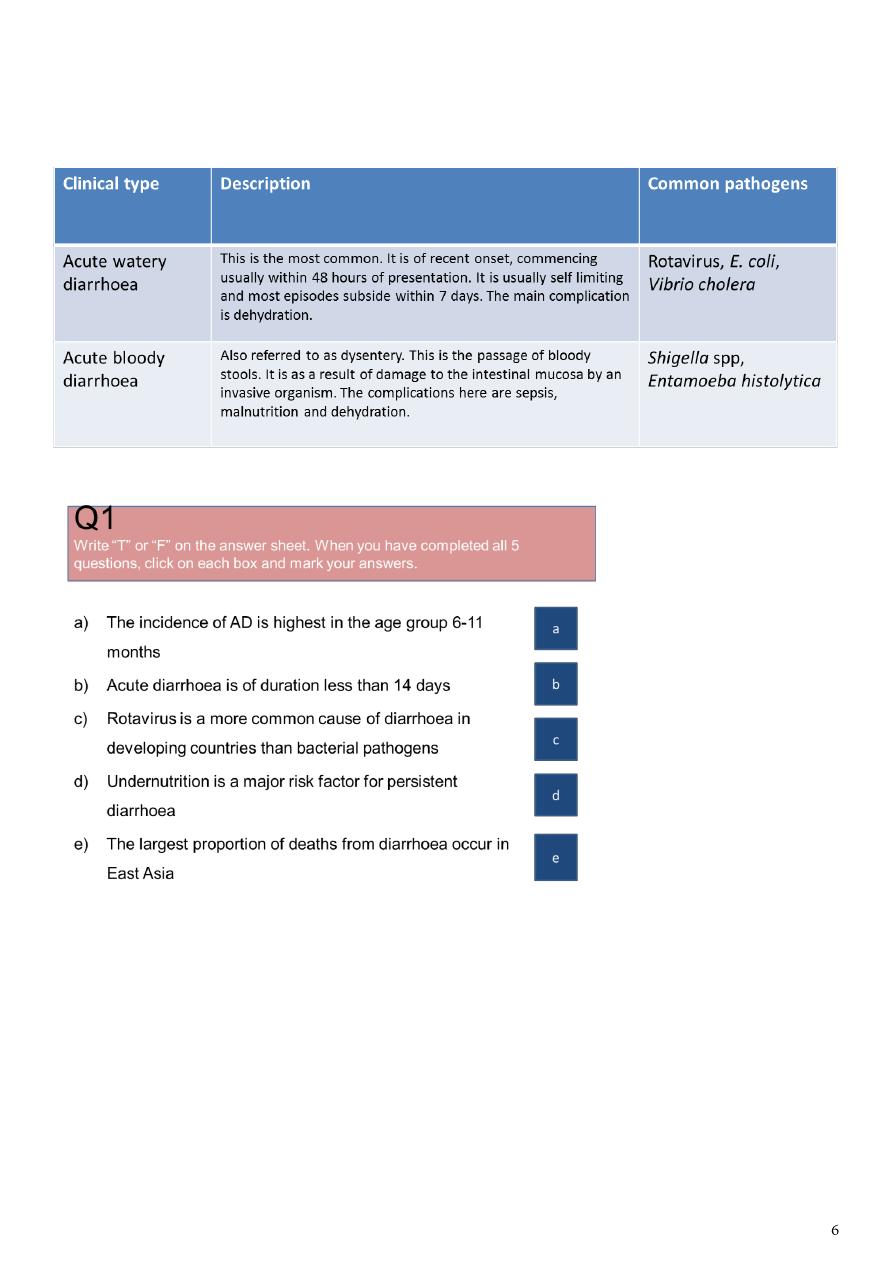

Common causes of AD:

More than 20 viruses, bacteria and parasites have been associated with acute diarhoea

Worldwide, rotavirus is the commonest cause of severe dehydrating diarrhoea causing

0.6 million deaths annually, 90% of which occur in developing countries

The incidence of specific pathogens varies between developed and developing countries

In developed countries, about 40% of AD cases are due to rotavirus and only 10-20% are

of bacterial origin while in developing countries, 50-60% are caused by bacteria while

15-25% are due to rotavirus

Clinical types of AD:

There are 2 main clinical types of AD

Each is a reflection of the underlying pathology and altered physiology

Answer to Q1a

This statement is True.

The incidence of diarrhoea is highest in age group 6-11 months. This is likely to be

associated with declining levels of antibodies acquired from the mother, lack of active

immunity in the infant and the introduction of complementary foods that may be

contaminated with diarrhoeal pathogens.

Answer to Q1b

This statement is True

Diarrhoea that begins acutely and lasts less than 14 days is called acute diarrhoea

Diarrhoea lasting longer than 14 days is persistent diarrhoea

Answer to Q1c

This statement is False

Bacterial pathogens cause most cases of diarrhoea in developing countries

Bacteria are responsible for 50-60% of cases of AD while rotavirus is responsible for 15-

25% cases

Answer to Q1d

This statement is True.

Undernourished children are at higher risk of suffering more frequent, severe and

prolonged episodes of diarrhoea

Answer to Q1e

This statement is False

East Asia and Pacific, South Asia and Africa are home to 9%, 38% and 46% respectively of

child deaths from diarrhoea

The rest of the world contributes only 7%

Clinical scenarios:

You will now work through a series of cases of AD

You will learn how to assess and manage children according to the latest WHO

guidelines

Start with scenario A. Try to answer the questions yourself before clicking on the

answers

WHO guideline for the classification of dehydration:

There are other established guidelines. Click here to see details

Other guidelines used to assess dehydration due to AD:

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines (NICE/UK)

ESPGHAN guidelines

These classify patients into

o minimal or no dehydration

o mild to moderate dehydration

o severe dehydration

o AAP guideline classifies patients as mild (3-5%), moderate (6-9%) and severe (>10%)

dehydration

Various scoring systems (Fortini et al., Gorelick et al.) proposed for assessment of child

with dehydration, but there is limited evidence to support their use particularly in

developing countries

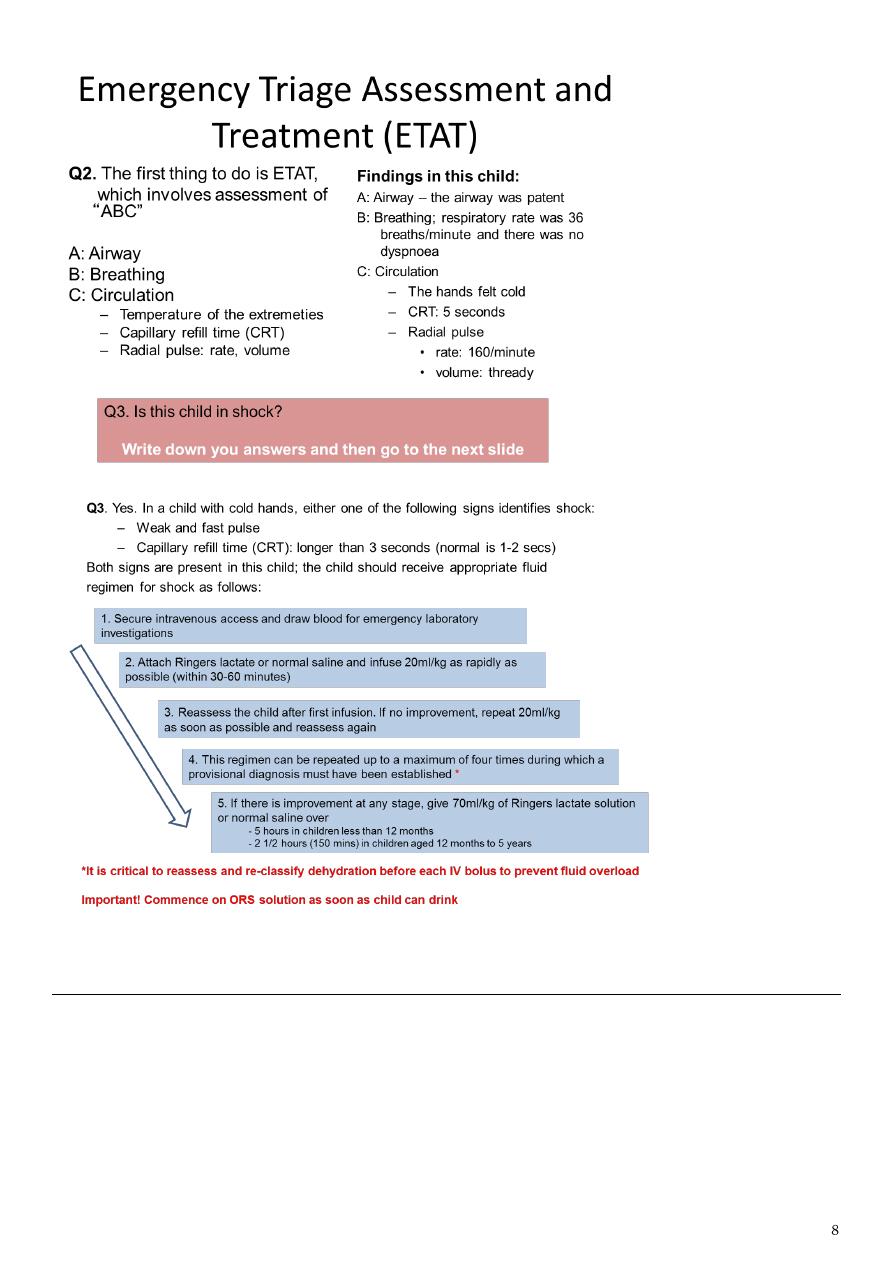

Treatment of severe dehydration:

Q5: Children with severe dehydration require rapid IV rehydration followed by oral

rehydration therapy

Q6: For IV rehydration, Ringer’s lactate (also called Hartmann’s solution) is

recommended. If not available, normal saline can be used

Q7: Give 100ml/kg of fluid as shown below:

aRepeat if the radial pulse is still very weak or not detectable

Answer: Q10a

This statement is False. The appropriate treatment is use of oral rehydration fluid. IV

infusion is only recommended for children with shock or severe dehydration. Even when a

child with some dehydration can not tolerate oral fluids, it is advisable to give oral fluids

through a nasogastric tube.

Answer: Q10b

This statement is True. WHO/UNICEF recommends the new improved oral rehydration

solution which has reduced concentration of sodium and glucose (LO-ORS). LO-ORS reduces

the risk of hypertonicity, reduces stool output, shortens the duration of diarrhoea and

reduces the need for intravenous fluids.

– Give the child 75ml/kg of ORS in the first 4 hours

– Show the mother how to give ORS solution, a teaspoonful every 1-2 minutes for child

under 2 years

– If the child vomits, wait 10 minutes, then resume giving ORS solution more slowly

– Monitor the child to be sure child is taking ORS solution

– Check child’s eyelids; if they become puffy, stop ORS solution

– Reassess the child after 4 hours, checking for signs of dehydration

– Teach the mother how to prepare ORS solution at home

– Advise on breastfeeding, for those still breastfeeding, and adequate feeding

– If no dehydration, teach the mother the rules of home treatment

Answers: Scenario D

Q11:

This child has acute bloody diarrhoea also called dysentery

Most episodes are due to Shigella spp

The diagnostic signs of dysentery are frequent loose stools with visible red blood

Other findings in the history or on examination may include

– Abdominal pain

– Fever

– Convulsions

– Lethargy

– Dehydration

– Rectal prolapse

Q12:

All children with severe dysentery require antibiotic treatment for 5 days

– Give an oal antibiotic to which most strains of shigella in your localiity are

sensitive

– Examples of antibiotics to which shigella strains can be sensitive are ciprofloxacin

and other fluoroquinolones

Also manage any dehydration

Ensure breastfeeding is continued for childen still breastfeeding and normal diet for older

childen

Follow-up the child

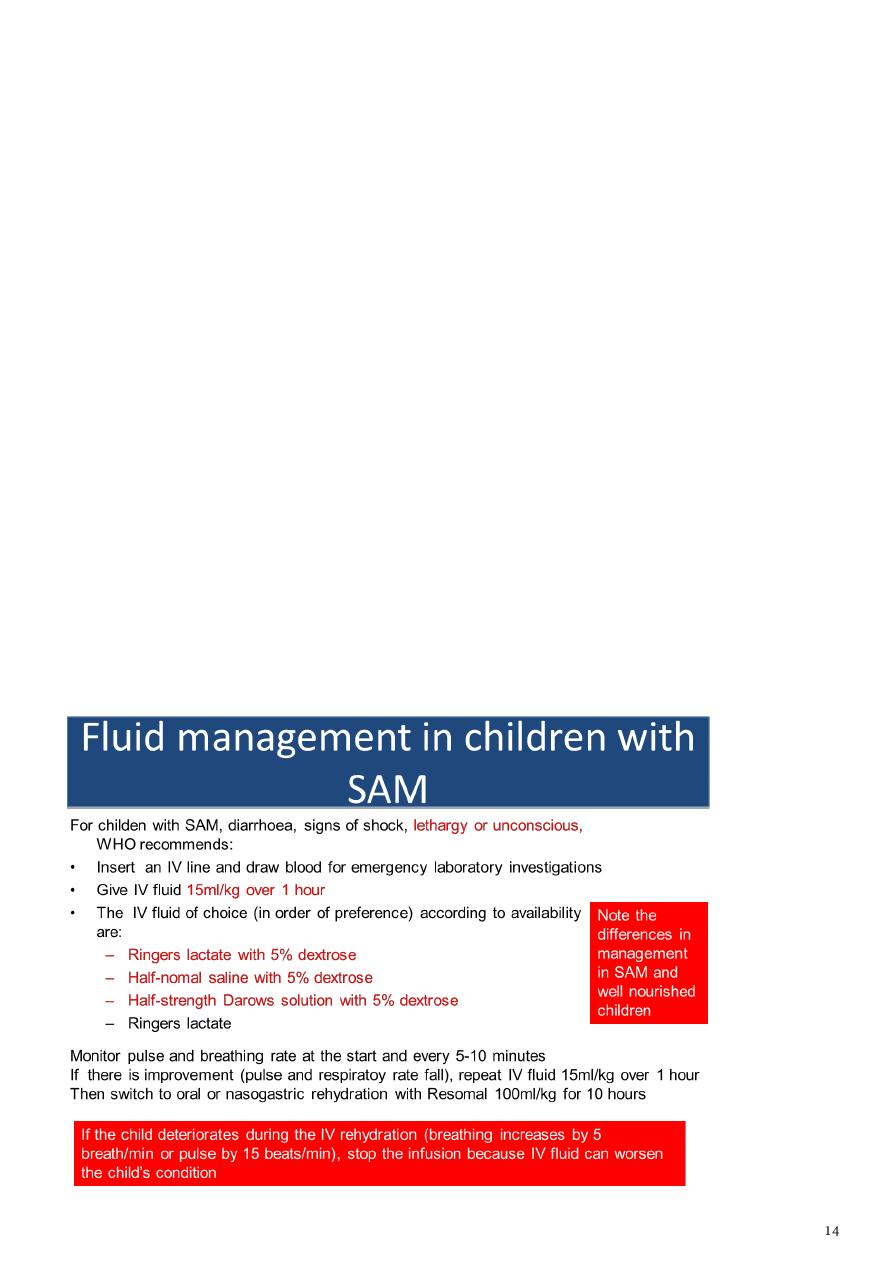

Answer: scenario E - Fluid management in children with SAM

Q13: The child has severe acute malnutrition: SAM

Q14: No. Dehydration is difficult to diagnose in SAM and it is often over diagnosed. The

doctor’s choice of IV normal saline, amount of fluid and rapidity of given IV fluid were all

incorrect and may have caused the child’s deterioration

Q15: The pathophysiological mechanisms that affect fluid management are:

• Although plasma sodium may be very low, total body sodium is often increased due

to

– increased sodium inside cells

– additional sodium in extracellular fluid if there is nutritional oedema

– reduced excretion of sodium by the kidneys

• Cardiac function is impaired in SAM

This explains why treatment with IV fluids can result in death from sodium overload and

heart failure.

• The correct management is reduced sodium oral rehydration fluid (ORF; e.g.

ReSoMal) given by mouth or naso-gastric tube if necessary. The volume and rate of

ORF are much less for malnourished than well-nourished children (see next slide)

IV fluids should be used only to treat shock in children with SAM who are also lethargic or

have lost consciousness!

End of clinical scenarios

The next few slides are on how to assess nutritional status, indications for laboratory

investigations, rational use of antibiotics and usage of zinc

Assessment of nutritional status:

• Assessment of nutritional status is important in children with

diarhoeal disease to identify those with severe acute malnutrition

(SAM)

• This is because abnormal physiological processes in SAM markedly

affect the distribution of sodium and therefore directly affect

clinical management

• In patients with SAM, although plasma sodium may be very low,

total body sodium is often increased due to:

– increased sodium inside cells as a result of decrease activity of sodium pumps

– additional sodium in extracellular fluid if there is nutritional oedema

– reduced excretion of sodium by the kidneys

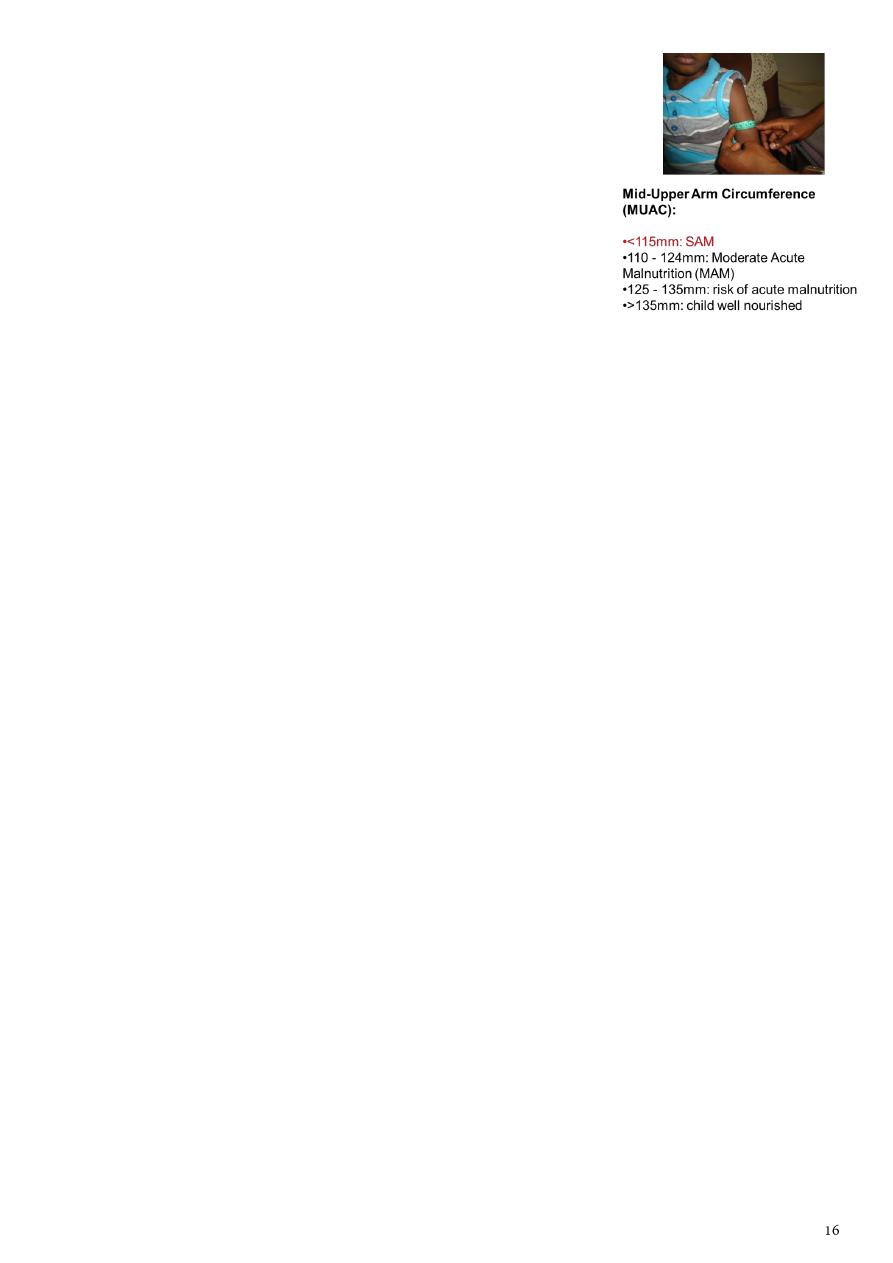

Methods of nutritional assessment:

Nutritional assessment can be done by:

• Looking for visible signs of severe wasting such as

muscle wasting and reduced subcutaneous fat

• Looking for other signs of malnutrition: angular

stomatitis, conjuctival and palmar pallor, sparse and

brittle hair, hypo- and hyperpigmentation of the skin

• Looking for nutritional oedema (pitting oedema of both feet)

• Use of anthropometry such as Weight-for-Height z-score (WHZ; < -3.0) or Mid-Upper

Arm Circumference (MUAC < 11.5cm in children aged 6-60 months)

MUAC: recommended for nutritional assessment in dehydration:

• MUAC is widely used in community screening of malnutrition because it is easy to

perform, accurate and quick

• MUAC is measured using Shakir’s strip or an inelastic

tape measure placed on the upper arm midway between

acromion process and olecranon

• Dehydration reduces weight; MUAC was less affected by

dehydration than WFLz score in a recent study*

Laboratory investigations:

AD is usually self-limiting and investigations to identify the

infectious agent are

not required

A. Indications for stool microscopy, culture and sensitivity

• Blood and mucus in the stool

• High fever

• Suspected septicaemic illness

• Diagnosis of AD is uncertain

B. Indications for measurement of Urea and Electrolytes

• Severe dehydration or shock

• Children on IV fluid

• Children with severe malnutrition

• Suspected cases of hypernatreamic dehydration

Rational use of antibiotics:

• Even though bacterial pathogens are the commonest cause of AD in developing

countries, there should be cautious and rational use of antibiotics to discourage

development of microbial resistance, avoid side effects and reduce cost

• Antibiotics should be used for:

– Severe invasive bacterial diarrhoea eg Shigellosis

– Cholera

– Girdiasis

– Suspected or proven sepsis

– Immunocompromised children

Zinc and diarrhoea:

• Zinc deficiency is common in developing countries and zinc is lost during diarrhoea

• Zinc deficiency is associated with impaired electrolyte and water absorption,

decreased brush border enzyme activity and impaired cellular and humoral immunity

• Treatment with zinc reduces the duration and severity of AD and also reduces the

frequency of further episodes during the subsequent 2-3 months

• WHO recommends that children from developing countries with diarrhoea be given

zinc for 10-14 days

– 10mg daily for children <6 months

– 20 mg daily for children >6 months

How can we prevent diarrhoeal disease?

This involves intervention at two levels:

• Primary prevention (to reduce disease transmission)

– Rotavirus and measles vaccines

– Handwashing with soap

– Providing adequate and safe drinking water

– Environmental sanitation

• Secondary prevention (to reduce disease severity)

– Promote breastfeeding

– Vitamin A supplementation

– Treatment of episodes of AD with zinc

Seminar2

: The edematous child

Oedema is a common presenting problem in paediatrics. It is defined as accumulation of

excess interstitial fluid and could be localised or generalised. Oedema results from either

excess salt and water retention of from increased transfer of fluid across the capillary

membranes. As such, it could be a presentation of mild conditions such as insect bite

reaction to more serious conditions such as glomerulonephritis, hepatic and cardiac

disease. Understanding the pathophysiology of oedema is important in the clinical

approach and management of this condition in children.

Contents

– Causes of oedema

– Clinical approach

– Investigations

– Management

CAUSES OF OEDEMA

Oedema results when there is:

1) Increased hydrostatic pressure

• acute nephritic syndrome, acute tubular necrosis, cardiac failure

2) Decreased plasma oncotic pressure (hypoproteinaemic states)

• nephrotic syndrome, chronic liver failure, protein losing enteropathy, protein

• caloric malnutrition

3) Increased capillary leakage

• insect bite, trauma, allergy, sepsis, angio-oedema

4) Impaired lymphatic flow

• lymphatic obstruction (tumour), congenital lymphoedema

5) Impaired venous flow

• hepatic venous outflow obstruction, superior/inferior vena cava obstruction

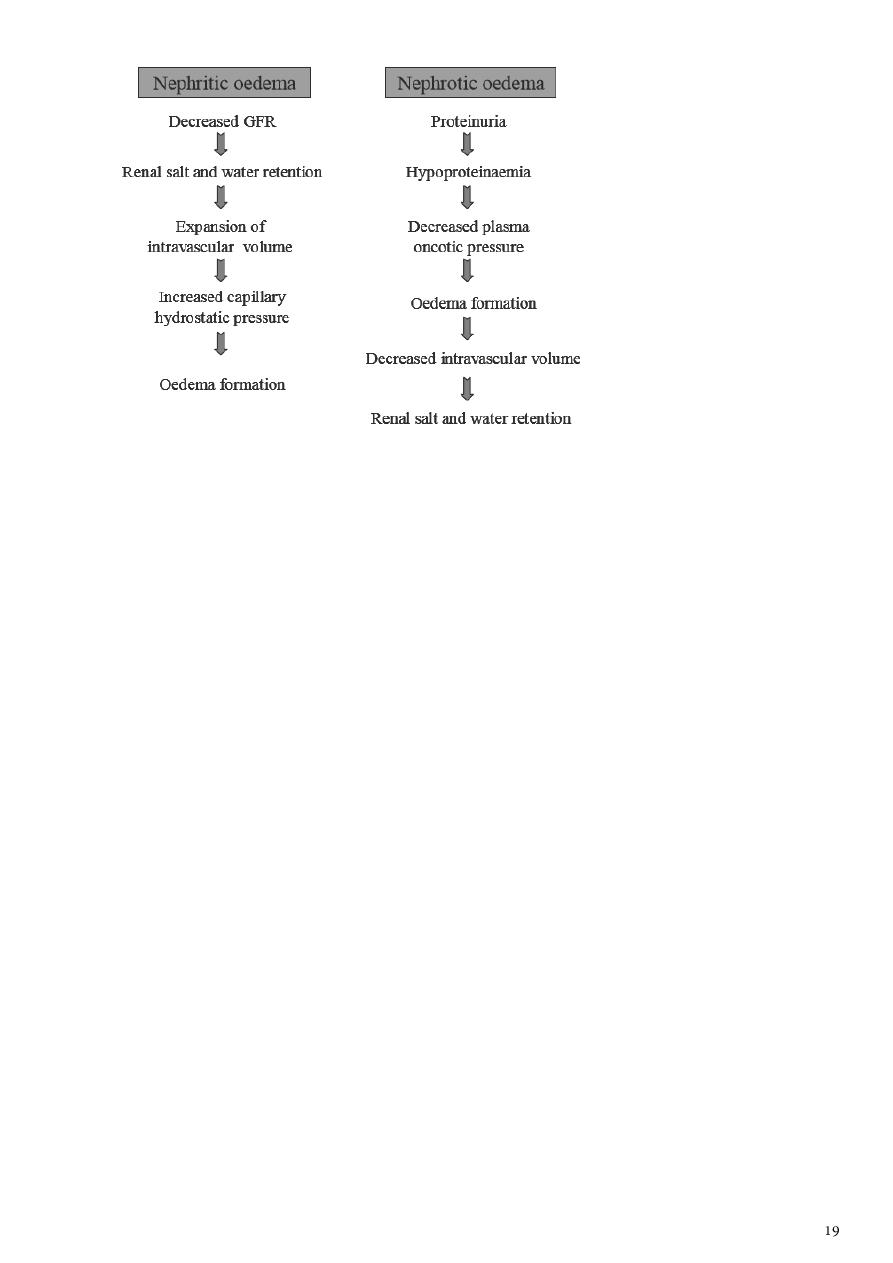

Mechanism of oedema formation in renal disease

Oedema formation between nephritic and nephrotic syndrome is markedly different.

Understanding oedema formation in these two conditions is important to differentiate the

two, as their management is entirely different

As such, a child with nephritic oedema will have symptoms and signs of

intravascular fluid overload such as orthopnoea, cardiomegaly, raised jugular venous

pressure, pulmonary congestion and hepatomegaly.

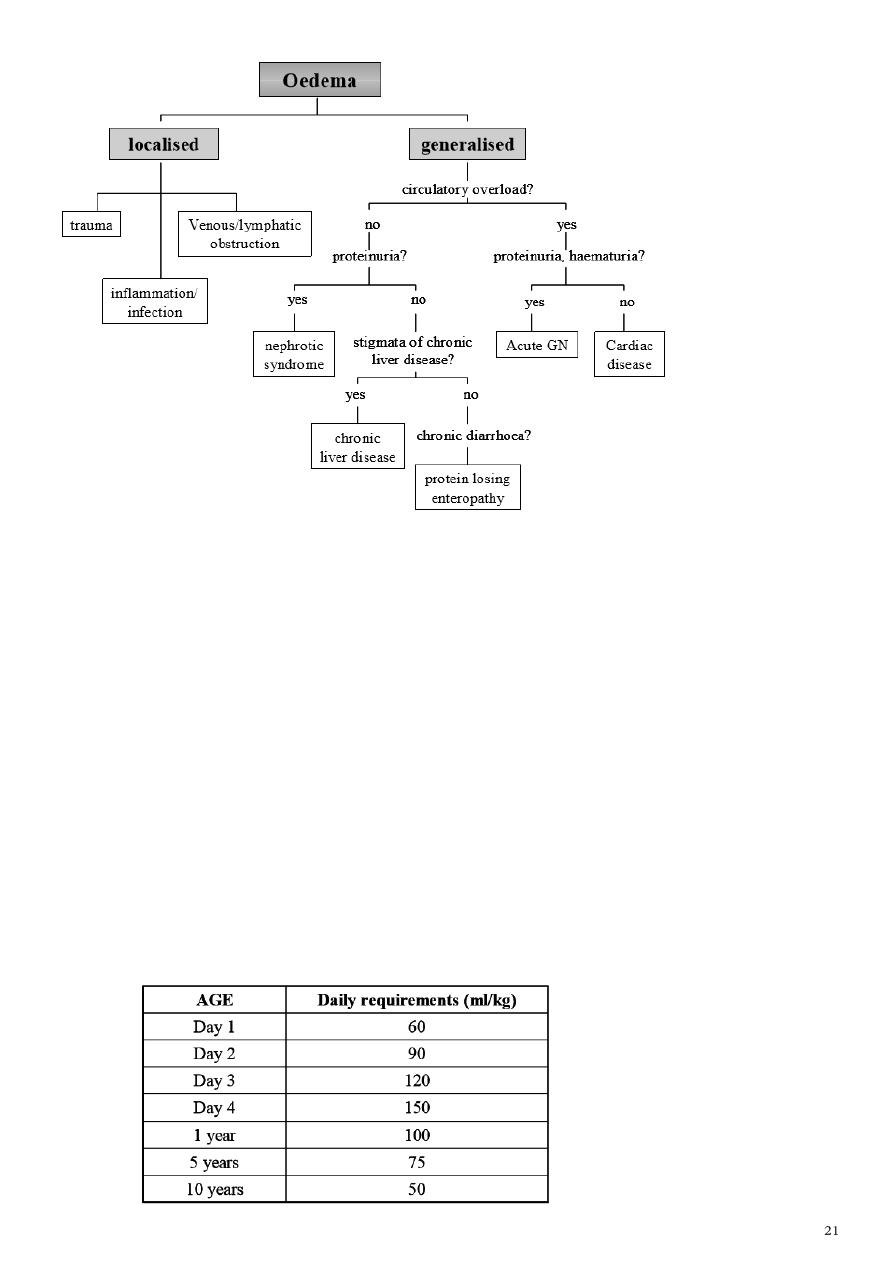

CLINICAL APPROACH TO AN OEDEMATOUS CHILD

1. Confirm oedema.

2. Assess distribution of oedema: Localised versus generalised. In generalised oedema, look

for dependent areas such as pretibial, sacral, scrotal, vulval oedema other than peri-orbital

oedema and ascites.

3. Detailed history and physical examination to assess severity, associated complications and

underlying cause of the oedema (algorithm . A) Localised oedema

i. History of trauma, insect bite or infection ii. Peripheral lymphoedema in newborn –

to exclude Turner’s syndrome iii. Acute oedema of the face and neck – to exclude superior

vena cava obstruction syndrome

B) Generalised oedema

i. Renal disease (most common cause in children) - gross haematuria, oliguria,

hypertension, cardiomegaly, pulmonary oedema to suggest acute glomerulonephritis. Frothy

urine suggests nephrotic syndrome. Absence of circulatory congestion differentiates

nephrotic syndrome from nephritic syndrome. - signs and symptoms of chronic renal

insufficiency such as anaemia, growth retardation and uraemic symptoms such as nausea and

vomiting - exclude secondary causes such as post-infectious glomerulonephritis, systemic

lupus erythematosus, Henoch Schonlein purpura nephritis.

ii. Liver disease - stigmata of chronic liver disease such as jaundice, palmar erythema,

clubbing, pruritic rash - hepatosplenomegaly with gross ascites in the absence of jaundice to

exclude portal vein thrombosis - previous operation scar such as Kasai porto-enterostomy

iii. Allergic reactions - oedema usually mild, commonly periorbital - history of

allergen exposure such as medications, animal dander, food preservatives and colouring -

associated rashes such as urticaria - assess for Stevens-Johnson reaction - if recurrent

oedema, consider C1 esterase deficiency

iv. Cardiac disease - symptoms of congestive cardiac failure such as decreased effort

tolerance, orthopnoea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea and signs such as cardiomegaly,

gallop rhythm, lung crepitations and turgid liver - assess for underlying cause such as

structural heart disease, cardiomyopathy and myocarditis Note: oedema in cardiac disease

often denotes a late sign in small children

v. Protein losing enteropathy - history of chronic diarrhoea, steatorrhoea and recurrent

abdominal pain - detailed dietary history for possible milk allergy and gluten

hypersensitivity - consider coeliac disease and inflammatory bowel disease in northern

Indians and Caucasians - assess for complications of anaemia, malnutrition and vitamin

deficiency states

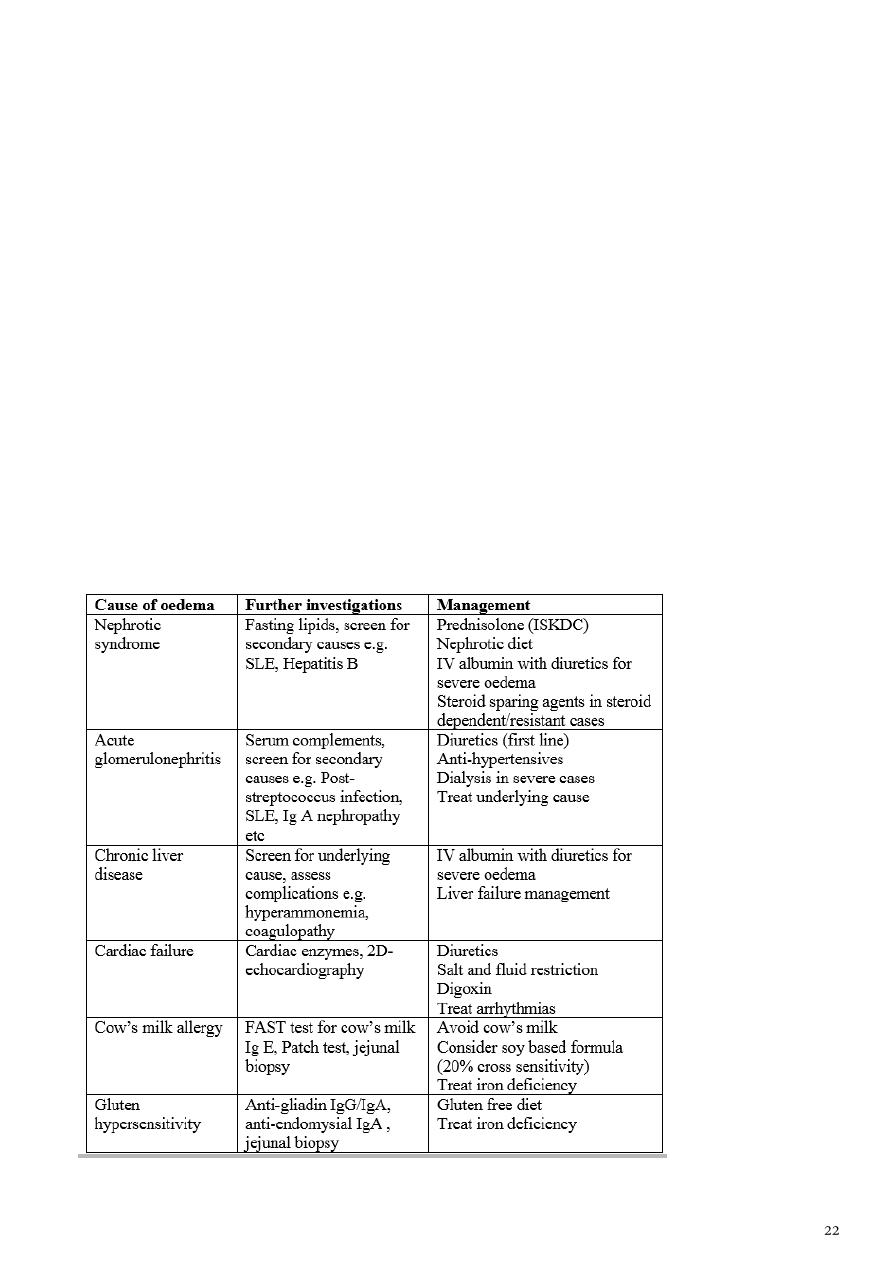

4. Investigations

Basic investigations could be conducted at the general practice set-up to delineate the

major causes of oedema and assess its severity. They include:

a) Urine dipstick and microscopy - proteinuria, haematuria and casts are indicative of

renal disease

b) Renal function test - raised serum urea and creatinine are indicative of renal disease

c) Full blood count - normochromic normocytic anaemia suggest chronic disease -

hypochromic microcytic anaemia suggest iron deficiency from occult gastrointestinal

bleeding i.e. cows milk allergy - megaloblastic anaemia suggest vitamin B12 and folate

deficiency from small bowel disease

d) Liver function test - hypoalbuminaemia in the absence of circulatory overload

suggests hypoproteinaemic states - hyperbilirubinaemia and transaminitis suggest liver

disease

e) Chest X-ray and electrocardiogram - cardiomegaly with prominent perihilar

vascular markings/upper lobe diversion and left ventricular hypertrophy confirms

intravascular fluid overload

Further investigations are indicated upon specialist referral depending on the most

likely cause.

Algorithm 1: Clinical approach and assessment of an oedematous child

MANAGEMENT

Subsequent management of oedema is dependent on the primary cause and its

severity. What you can do

A) Localised oedema

Management

1. Insect bite reaction ------->Anti-histamine, anti-inflammatory

(topical steroid)

2. Local infection -------> Incision and drainage, wound dressing, antibiotics

B) Generalised oedema

General measures

a) Dietary management

sodium restriction to 2 grams/m2/day

fluid restriction to 2/3 maintenance depending on severity of oedema

b) Diuretic therapy

i. Loop diuretics

- Frusemide (Lasix)

1-5 mg/kg/dose 6-8 hourly (IV/IM/PO)

- Bumetanide (Burinex)

0.02-0.1 mg/kg/dose 12-24 hourly (PO) 0.1-0.2 mg/kg/dose 8-12 hourly (IV/IM)

Note: higher doses are required in acute glomerulonephritis or chronic renal

impairment

Side effects- hyponatremia, hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis

ii. Hydrochlorothiazide

- 1 mg/kg/dose 12-24 hourly (PO)

iii. Spironolactone

- used in combination with loop diuretics/ thiazides for potassium sparing effects

0-10 kg: 6.25 mg/dose 12 hourly (PO)

11-20 kg: 12.5 mg/dose 12 hourly (PO)

21-40 kg: 25 mg/dose 12 hourly (PO)

> 40 kg: 25 mg/dose 8 hourly (PO)

SPECIFIC MANAGEMENT UPON SPECIALIST REFERREL

CONCLUSION

Oedema can be due to

increased hydrostatic pressure

decreased plasma oncotic pressure

increased capillary leakage

impaired lymphatic flow

impaired venous flow

This could be a manifestation of a mild or a serious medical conditions such as renal, hepatic

or cardiac diseases. Early recognition of oedema and prompt diagnosis of the underlying

cause is important. Initial assessment and stabilisation of patient should be instituted prior to

specialist referral.

An approach to a child with oedema

Oedema: accumulation excess interstitial fluid

Increased hydrostatic pressure

Acute nephritic syndrome

Congestive cardiac failure

Decreased plasma oncotic pressure

Protein calorie malnutrition, Nephrotic syndrome; protein loosing enteropathy

Increased capillary leakage

Allergy, sepsis, angiooedema.

Impaired venous flow

Vanacaval obstruction, hepatic vein obstruction

Impaired lymphatic flow

Congenital lymphedema, Wuchereria bancrofti infection

Examples for formulation of questions

Localized oedema

Insect bite; trauma; skin infections

Kwashiorkar (bilateral pedal)

Superior vanacaval obstruction

Lymphatic obstruction

Orthostatic

Generalized oedema

Renal: periorbital; hematuria; hypertension; symptoms of collagen disease

(rash, joint pain); frothy urine; symptoms of uraemia (vomiting, nausea, pallor),

convulsion, low urine output.

Cardiac: orthopnoea, joint pain; palpitation; giddiness; fainting episodes; bluish

episodes;

Protein energy malnutrition: low calorie and protein in the diet for long;

precipitating factors (persistent diarrhea, chronic illnesses)

Hepatic: Jaundice; ascites; prominent abdominal veins; neonatal umbilical sepsis;

spleenomegaly; purpura

Collagen diseases: fever, rash, joint pain, pallor

First case:

4 year old girl, who recently recovered from a sore

throat, was brought to the OPD with symptoms of

swelling of both feet. Physical examination reveals

edema around the eyes and the ankle. A routine

urinalysis reveals the following results.

Urine examination

Chemical/Physical Analysis Color:Yellow’ Blood:Moderate;Clarity:Hazy;pH:6.5

Glucose:Negative;Protein:300mg/dL;Ketones:Negative

Specific Gravity:1.015 ;Nitrite:Negative

Microscopic Analysis

20-50 RBC/hpf

10-20 WBC/hpf

2-5 RBC casts/hpf

2-5 Granular casts/hpf

What is the most likely diagnosis?

Second case

5 year male child

Swelling first noticed around eyes.

No history of shortness of breath; fever; cough; jaundice;

umbilical infection; no dark colored urine.

Height: 110cms; Wt: 18kg; liver not enlarged; Ascites

present

The most likely diagnosis is

Third case

12 year male from Pokhara; arrived after traveling by bus

for 12 hours.

History of fever

Upper abdominal pain

Dark colored urine

No past history of sore throat, rash, joint pain diarrhea,

trauma.

Comfortably lying flat in bed

Oral temp: 40C

Respiratory rate: 28.min

Bilateral pedal edema, non tender

Absence of Jaundice

Weight: 38 Kg.

Chest: normal

Abdomen: Tender R hypo. No free fluid

Normal blood count

Urine: routine normal

Liver function: normal

X-ray chest: normal

What causes we have excluded?

Increased hydrostatic pressure?

Decreased plasma oncotic pressure?

Increased capillary leakage?

Impaired venous flow?

Impaired lymphatic flow?

Bilateral edema and tender R hypochondrium.

Ultrasound of the abdomen:

Thickened Gall Bladder wall

Mucocoele

Third case :Final diagnosis and pathophysiology

Edema: increased hydrostatic pressure due to gravitational effect from prolonged leg

hanging.

R. Hypochondrium pain and fever: cholecystitis and mucocele of gall bladder

(ultrasound supported)

Edema subsided on the next day after admission.

Fourth case

5 year male child

Swelling started from limb : one month

No history of cough, shortness of breath, cyanosis, jaundice,

dark colored urine, umbilical infection.

Persistent diarrhea +.

Irritable; wt: 12 kg; Ht: 100cms. Serum protein: 1.5G/dL;

Urine normal

What is the diagnosis?

Seminar3

: Pyrexia of unknown origin

Children having fever >38.3 C prolonged of at least 8 days duration and initial 3-7 days of

hospital or outpatient; history and physical examination and basic investigations as

CBC,ESR, x ray,urine test,stool,test, within this 8 days, without reaching to the diagnosis for

the source or the cause of fever, are considered as having PUO. About 5-15% of cases with

fever considered as having PUO. PUO is usually caused by common problems but with

unusual presentations.

Aetiology;

The most common causes are

1.infections 30-40%

2. malignancy 20-30%,As Leukemia, Lymphoma, solid tumors, Willm and neuroblastoma,

bone tumors

3.connective tissue disorders 10-15% AS juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, SLE.

Miscellaneous causes;

l. drug fever

2.Kawasaki disease

3.HIV

4.Infamatory bowel disease

5. Factitious fever (MAUNCHAUSEN OF PROXY).

INFECTIONS INCLUDES

BACTEREMIA IN CHILDREN UNDER 2 YEAR

UTI, rare to be the cause as easy to diagnose it

INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

CAT SCRACH DISEASE

TUBERCULOSIS

EB-VIRUS INFECTION

TYPHOID FEVER

BRUCELLOSIS

SARCOIDOSIS

TULEREMIA

TOXOPLASMOSIS

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------common

suggestions of PUO or prolonged fever in children if not resolve within 3-5 days ,is to think

of EB VIRUS ,KAWASAKI DISEASE, OR UTI.

Approach for diagnosis of FUO OR PUO

Good history and physical examinations are critical components of evaluation of febrile

child and frequently result in detection of the underlying cause .

History

Fever characteristics as duration pattern, rigor, sweating, timing as at night in TB, and in

lymphoma . its response to antipyretics and after response; how is the child appears;

usually viral will be normal but in bacterial pt looks toxic and ill.

Rash

Rash may be present with fever and the study of the type of the rash as petechial or

maculopapular. Bacterial or viral infection may cause maculopapular or petechial or

urticarial rash or and its distribution may help us in diagnosis. Palpable purpura may be

seen in vasculitis. Vesicles in viral infections.

Accompanying symptomatology;

Inflammatory or malignancy or vasculitis may result in multisystemic involvement such as

cough and shortness of breath due to to carditis, pleuritis.GI symptoms CNS symptoms and

joint features .

Arthralgia in joint septic infection and in leukemia and in rheumatoid arthritis, lyme disease,

Bone pain in leukemia and SLE .

GI symptoms as in Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis.

CNS features as confusion and seizures as in bacterial endocarditis, cerebral abscess,

tuberculous meningitis.

Urinary symptoms as frequency and dysuria.

Poor growth and anorexia as in chronic disease opposing bacterial infection, as acute state.

Immunization status .

Drug history

Past history; as sickle cell disease increase possibility of infection.

Exposure to causative agent as travel to malarial area or contact typhoid fever

or TB patient. Or exposed to a cat scrach.

Psychological history ;incase of factitious fever mother may create the fever as by heating

the thermometer, or give some drugs as she want to stay in the hospital.

Physical examination

Confirm the temperature

Toxic child is more likely to have bacterial infection. Most well appearing children do not

have bacterial infection

BP,PULSE RATE ,RR,ARE CRUCIAL FOR THE STASTUS OF THE PATIENT.

COMPLETE PHYSICAL EXAMINATION FOR LYMPHNODES AND APPEARANCE AND PALLOR

AND SKIN AND NAIL AND ORGANOMEGALY AND ABDOMEN ,CVS,RESPIRATORY

S,CNS,LOCOMOTOR SYSTEM., WILL NARROW THE LIMIT OF POSSIBLE CAUSES FOR THE

FEVER.

INVESTIGATIONS

More extensive lab investigations are needed like blood culture,liver function ,kidney

function test,thyroid function as in hyperthyroidism, ,serology for viral infections or

bacterial,CTscan of abdomen or brain or the chest or pelvis, Us STUDY AND CXR. Etc…

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Most of the cases finally can be diagnosed for the cause of fever, but still few cases may not

find the cause and the child remits with time called ;( Fever without source ) FWS.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Seminar4

: Vaccination

The immune system is a complex network of specialized organs and cells protects the body

from destruction by foreign agents and microbial pathogens , degrades and removes

damaged or dead cells, and exerts a surveillance function to prevent the development and

growth of malignant cells. The immune system is composed of immune cells and central and

peripheral lymphoid structures. The immune cells move throughout the body, searching for

and destroying foreign substances but avoiding cells regarded as self.

Natural immunity:

It is not produced by the immune response. This type of immunity is present at birth and

appears to be present in all members of a species.

Acquired immunity:

It develops after birth as a result of exposure to an antigen, thereby activating the immune

response. Acquired immunity can be either active or passive, depending on whether the

immune response took place in the host or a donor.

Differences of immune system of children and adult

The normal human no fully active immune system at birth because of immaturity. It relies

instead on passively transferred antibodies from the mother. This maternal antibody slowly

decreases in concentration and for all practical purposes, has waned by 1 year.

The infant own production of antibody begins to be meaningful at 7 or 8 months of age when

the total of maternal and infant antibody is low. One has waned and the other is not up to

full strength. This is age when many of the infectious disease processes of infancy begin /e.g.

otitis media, pneumonia.

Vaccination

Administration of a substance to a person with the purpose of preventing a disease

Traditionally composed of a killed or weakened microorganism

Vaccination works by creating a type of immune response that enables the memory cells

to later respond to a similar organism before it can cause disease

Early History of Vaccination

Pioneered India and China in the 17th century

The tradition of vaccination may have originated in India in AD 1000

Powdered scabs from people infected with smallpox was used to protect against the

disease

Smallpox was responsible for 8 to 20% of all deaths in several European countries in the

18th century

In 1721 Lady Mary Wortley Montagu brought the knowledge of these techniques from

Constantinople (now Istanbul) to England

Two to three percent of the smallpox vaccinees, however, died from the vaccination

itself

Benjamin Jesty and, later, Edward Jenner could show that vaccination with the less

dangerous cowpox could protect against infection with smallpox

The word vaccination, which is derived from vacca, the Latin word for cow.

Era of Vaccination

English physician Edward Jenner

observed that milkmaids stricken with a viral disease called cowpox were rarely victims

of a similar disease, smallpox

Jenner took a few drops of fluid from a pustule of a woman who had cowpox and

injected the fluid into a healthy young boy who had never had cowpox or smallpox

Six weeks later, Jenner injected the boy with fluid from a smallpox pustule, but the boy

remained free of the dreaded smallpox.

In those days, a million people died from smallpox each year in Europe alone, most of

them children.

Those who survived were often left with blindness, deep scars, and deformities

In 1796, Jenner started on a course that would ease the suffering of people around the

world for centuries to come.

By 1980, an updated version of Jenner vaccine lead to the total eradication of smallpox.

Early History of Vaccination

In 1879 Louis Pasteur showed that chicken cholera weakened by growing it in the

laboratory could protect against infection with more virulent strains

1881 he showed in a public experiment at Pouilly-Le-Fort that his anthrax vaccine was

efficient in protecting sheep, a goat, and cows.

In 1885 Pasteur developed a vaccine against rabies based on a live attenuated virus

A year later Edmund Salmon and Theobald Smith developed a (heat) killed cholera

vaccine.

Over the next 20 years killed typhoid and plague vaccines were developed

In 1927 the bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG vaccine) against tuberculosis vere developed

Since Jenner's time, vaccines have been developed against more than 20 infectious diseases

•

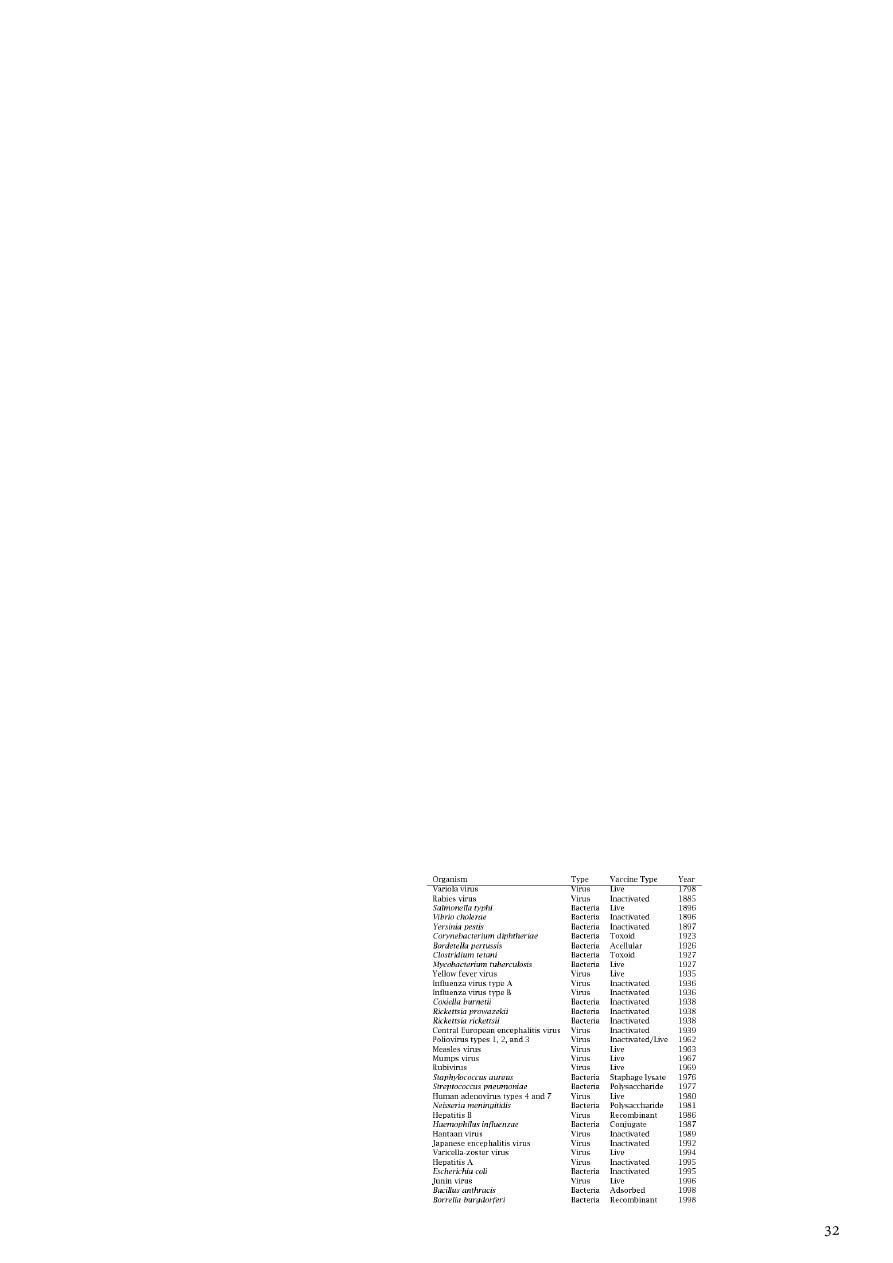

The date of introduction of first generation of vaccines for use in humans*

–

1798 Smallpox

–

1885 Rabies

–

1897 Plague

–

1923 Diphtheria

–

1926 Pertussis

–

1927 Tuberculosis (BCG)

–

1927 Tetanus

–

1935 Yellow Fever

•

After World War II

–

1955 Injectable Polio Vaccine (IPV)

–

1962 Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV)

–

1964 Measles

–

1967 Mumps

–

1970 Rubella

–

1981 Hepatitis B

Vaccination Today

Vaccines have been made for only 34 of the more than 400 known pathogens that are

harmful to man.

Immunization saves the lives of 3 million children each year, but that 2 million more lives

could be saved if existing vaccines were applied on a full-scale worldwide

Human Vaccines against pathogens

Type of Vaccination

Live Vaccines

• Characteristics

• Able to replicate in the host

• Attenuated (weakened) so they do not cause disease

• Advantages

• Induce a broad immune response (cellular and humoral)

• Low doses of vaccine are normally sufficient

• Long-lasting protection are often induced

• Disadvantages

• May cause adverse reactions

• May be transmitted from person to person

Subunit Vaccines

• Relatively easy to produce (not live)

• Classically produced by inactivating a whole virus or bacterium

• Heat

• Chemicals

• The vaccine may be purified

• Selecting one or a few proteins which confer protection

• Bordetella pertussis (whooping cough)

• Create a better-tolerated vaccine that is free from whole microorganism cells

Subunit Vaccines: Polysaccharides

• Polysaccharides

• Many bacteria have polysaccharides in their outer membrane

• Polysaccharide based vaccines

• Neisseria meningitidis

• Streptococcus pneumoniae

• Generate a T cell-independent response

• Inefficient in children younger than 2 years old

• Overcome by conjugating the polysaccharides to peptides

• Used in vaccines against Streptococcus pneumoniae and

Haemophilus influenzae.

Subunit Vaccines: Toxoids

• Toxins

• Responsible for the pathogenesis of many bacteria

• Toxoids

• Inactivated toxins

• Toxoid based vaccines

• Bordetella pertussis

• Clostridium tetani

• Corynebacterium diphtheriae

• Inactivation

• Traditionally done by chemical means

• Altering the DNA sequences important to toxicity

Subunit Vaccines: Recombinant

• The hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccine

• Originally based on the surface antigen purified from the blood of chronically

infected individuals.

• Due to safety concerns, the HBV vaccine became the first to be produced using

recombinant DNA technology (1986)

• Produced in bakers’ yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae)

• Virus-like particles (VLPs)

• Viral proteins that self-assemble to particles with the same size as the native

virus.

• VLP is the basis of a promising new vaccine against human papilloma virus (HPV)

• Merck

• In phase III

Genetic Vaccines

• Introduce DNA or RNA into the host

• Injected (Naked)

• Coated on gold particles

• Carried by viruses

• vaccinia, adenovirus, or alphaviruses

• bacteria such as

• Salmonella typhi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis

• Advantages

• Easy to produce

• Induce cellular response

• Disadvantages

• Low response in 1st generation

Type of Vaccination

Live attenuated Vaccine

OPV

Measles

Rubella

Mumps

BCG

Varicella Vaccine

Inactivated organism or their products

Diphtheria

Tetanus

Pertussis( whole cell/acellular)

Hepatits Avaccine

Hepatitis B

Pneumococcal Polysaccharide vaccine

Influenza

IPV

Hib

Passive Immunity

Transfer of antibody produced by one human or other animal to another

Transplacental most important source in infancy

Temporary protection

Sources of Passive Immunity

Almost all blood or blood products

Homologous pooled human antibody (immune globulin)

Homologous human hyperimmune globulin

Heterologous hyperimmune serum (antitoxin)

IMMUNOGLOBULIN PREPARETION

Normal human Ig.

Normal human Ig is an antibody-rich fraction, obtained from a pool of at least 1000 donors.

The preparation should contain at least 90% intact IgG; it should be as free as possible from

IgG aggregates; all IgG sub-classes should be present; there should be a low IgA

concentration; the level of antibody against at least two bacterial species and two viruses

should be ascertained

Normal human Ig used to prevent measles in highly susceptible individuals and to provide

temporary protection /up to 12 weeks/ against hepatitis A infection.

Live vaccines should not normally be given for 12 weeks after an injection of normal human

Ig.

· Specific human Ig.

These preparations are made from the plasma of patient who have recently recovered from

an infection or are obtained from individuals who have been immunized against a specific

infection.

The advantages of Ig-s are:

1. freedom from hepatitis B

2. concentration of the antibodies into a small volume for intramuscular use.

3. stable antibody content, if properly stored.

Vaccine Preventable Diseases

An infectious disease for which an effective preventive vaccine exists.

If a person dies from it, the death is considered a vaccine-preventable death.

FULLY IMMUNIZED CHILD

A child who received

One dose of BCG,

Three doses of DPT and OPV,

One dose of measles

before one year of age.

This gives a child the best chance for survival.

Control

Reduction of prevalence or incidence of disease to lower acceptable level.

Elimination

Eradication of disease from a large geographic region or political jurisdiction

Either reduction of infectious disease’s prevalence in regional population to zero or

reduction of global prevalence to a negligible amount.

Eradication

Termination of all transmissions of infection by extermination of infectious agent

through surveillance and containment.

Reduction of infectious disease’s prevalence in global host population to zero.

EXPANDED PROGRAMME ON IMMUNISATION (EPI)

EPI launched in 1974

Build on smallpox infrastructure

Targeted 6 diseases

EPI progressively adopted by all countries

Universal by early 1098s

Addition to EPI

Yellow fever in 1988

• For endemic countries only : 33 in Africa, 11 in S. America.

• Given with measles vaccine

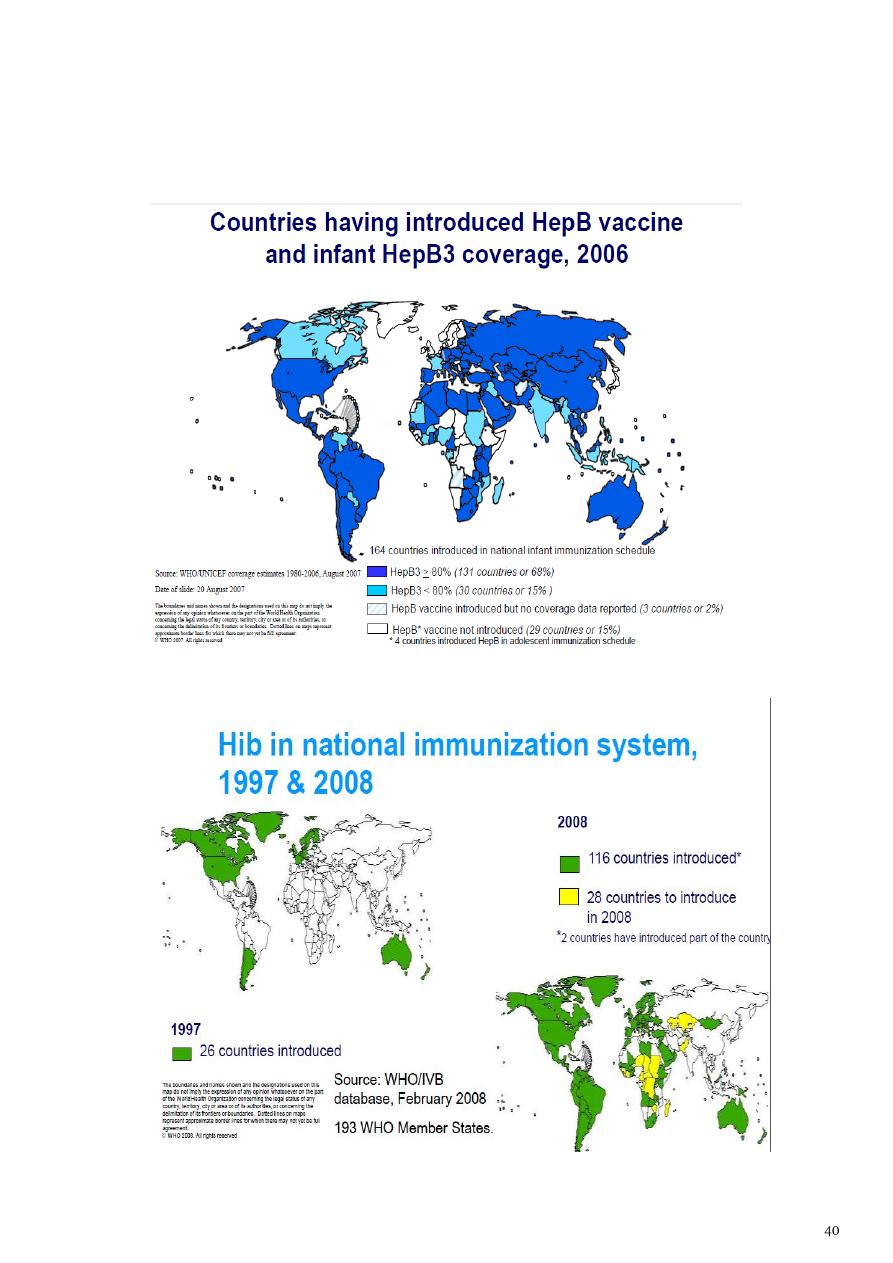

Hepatitis B in 1992

• In high seroprevalence countries by 1995

• In all countries by 1997

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib)

• 1998 : based on disease burden and capacity

• 2006 : all countries. ( lack of data should not be obstacle)

COMPONENTS of program

1. Immunization of pregnant women against tetanus.

2. Immunization of children in their first year of life against 6 VPDs.

3) Immunisation in preterm infants

All vaccines except Hepatitis B

If BW < 2Kg & mother HBsAg negative :- postpone till baby attaines 2kg wt or 2 mths

of age.

If BW < 2Kg & mother HBsAg positive :- give vaccine + immunoglobulin.

4) Children receiving corticosteroids

Children receiving corticosteroids at the dose of 2 mg/kg/day for more than 14 days

should not receive live virus vaccines until steroid has been discontinued for at least

1 month.

Tetanus toxoid

Intramuscular – upper arm – 0.5 ml

Pregnancy – 2 doses - 1

st

dose as early as possible and second dose after 4 weeks of

first dose and before 36 weeks of pregnancy

Pregnancy – booster dose (before 36 weeks of pregnancy) – If received 2 TT doses in

a pregnancy within last three years. Give TT to woman in labour, if she has not

received TT previously

TT booster for both boys and girls at 10 years and 16 years

No TT required between two doses in case of injury

BCG

At birth or as early as possible till one year of age

0.1 ml (0.05ml until one month of age)

Intra-dermal

Left upper arm

Hepatitis B

Birth dose – within 24 hours of birth

0.5 ml

Intramuscular

Antero-lateral side of mid-thigh

Rest three doses at 6 weeks, 10 weeks and 14 weeks

OPV

Zero dose – within first 15 days of birth

2 drops

Oral

First, second and third doses at 6, 10 and 14 weeks with DPT-1, 2 and 3

OPV booster with DPT booster at 16-24 months

DPT

Three primary doses at 6, 10 and 14 weeks with OPV-1, 2 and 3

0.5 ml

Intra-muscular

Antero-lateral side of mid-thigh

One booster at 16-24 m with OPV booster (antero-lateral side of mid-thigh) and

second booster at 5-6 years (upper arm)

Measles

At 9 completed months to 12 months

Give up to 5 years if not received at 9-12 months age

Second dose at 16-24 months (select states after catch-up campaign) – Measles

Containing Vaccine

0.5 ml

Sub-cutaneous

Right upper arm

Along with Vitamin A (1

st

dose) – 1ml (1 lakh IU) - oral

Constraints

Illiteracy

Non uniform coverage

Poor implementation

Poor monitoring

High drop outs

Declining coverage in some major states

Over reporting

Poor injection safety

Reorientation of staff being not carried out

Vacany of staff at field level not filled

Poor surveillance of vaccine preventable diseases

Poor vaccine logistics

Poor maintainance of equipments

Extra ordinary emphasis on polio vaccine

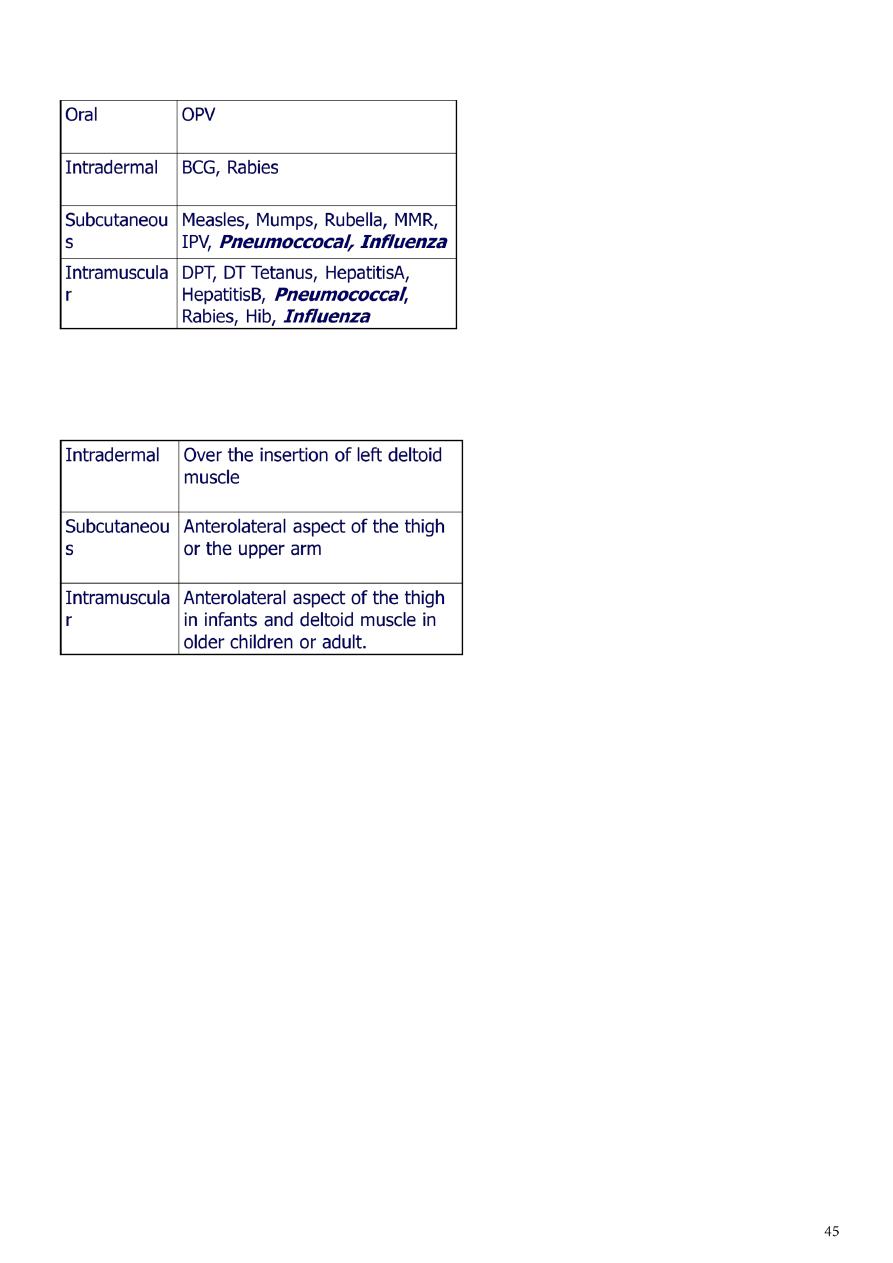

Route of Administration

Site of Administration

Who should not be vaccinated?

Allergy

Fever

HIV infection

Immunodeficiency

IG administration

Neurological disorder

Prematurity

Reactions to Previous vaccine

Simultaneous administration of Vaccines

Thrombocytopenia

Allergy

A. Allergic Reactions to Egg-related antigens

1. Yellow fever and influenza vaccines do contain egg proteins and rarely induce

immediate allergic reactions. Skin testing is recommended before

administration with an history of allergic to egg

2. MMR- Even those with severe hypersensitivity are at low risk of anaphylaxis.

B. Antibiotic-induced allergic reaction

Delayed type local reaction 48-96 hours afterwards and is usually minor

IPV and OPV – streptomycin, neomycin and polymyxin B

MMR and varicella vaccine-neomycin

C. Gelatin- MMR, Varicella vaccine

Fever

Low-grade fever or mild illness is not a contraindication for vaccination

Children with moderate or severe febrile illnesses can be vaccinated as soon as they

are recovering and no longer acutely ill

Vaccination in Pregnancy

Risk to a developing fetus from vaccination of the mother during pregnancy is mostly

theoretical

Only smallpox vaccine has ever been shown to injure a fetus

The benefits of vaccinating usually outweigh potential risks

Inactivated vaccines

– Routine (influenza)

– Vaccinate if indicated (hep B, Td, mening, rabies)

– Vaccinate if benefit outweighs risk (all other)

– Live vaccine – do not administer

– Exception is yellow fever vaccine

HIV Infection

No BCG

OPV is Contraindicated

– in household contact, in recipient ( asymptomatic or symptomatic)

– IPV for these children and household contacts

MMR vaccination should be considered for all asymptomatic and to all symptomatic

HIV-infected persons who do not have evidence of severe immunosuprresion or

measles immunity

Pneumococcal vaccine, Hib, DTP (or DTaP), Hepatitis B vaccine, Influenza vaccines are

all indicated

Immunosupression

No live viral vaccines and BCG. IPV for these patients, their siblings and their

household contacts

No live vaccine (except varicella) until six months after immunosuppressive therapy

Neurological disorder

Progressive developmental delay or changing neurological findings (e.g. infantile

spasm) - defer pertussis immunization

Personal history of convulsions

Recent seizures - defer pertussis immunization

Conditions predisposing to seizures or neurological deterioration (e.g. tuberous

sclerosis) - defer pertussis immunization

Reactions

Severe Reactions to DTP

– Insonable cry lasting more than 3 hrs with 48 hrs of dose

– Seizure with 3 days

– Severe local reactions

– Family hx of adverse event

Not a contraindication, but consider carefully the benefits and risks, if need to

vaccinate can use acellular DTP for less reactions

GBS with 6 weeks after a dose of DTP

– Again based on risks and benefits for further dose of DTP and risk of GBS

recurrence.

Contraindication for further dose of DTP

– encephalopathy within 7 days of a dose of DTP

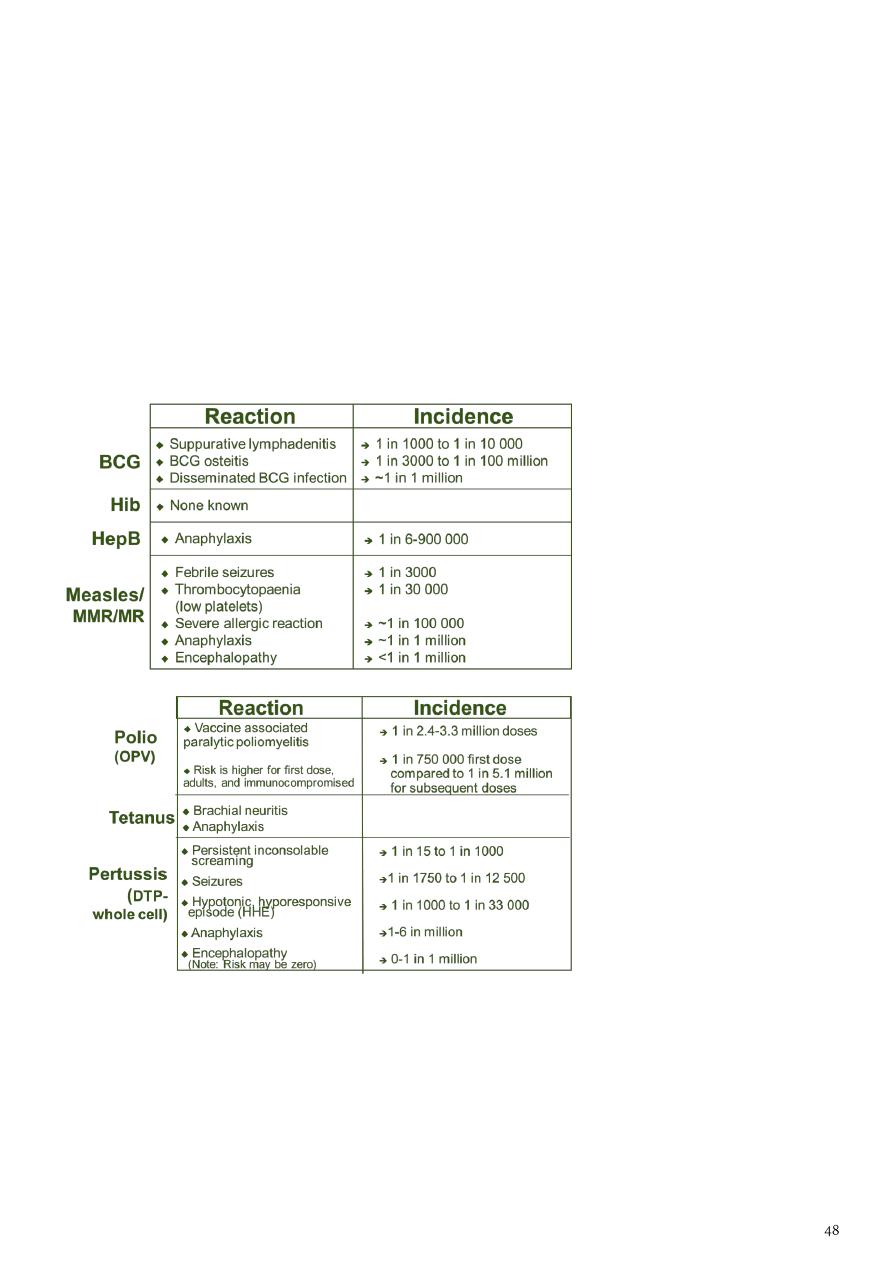

VACCINE REACTIONS

Common, minor reactions

– vaccine stimulates immune system

– settle on their own

– warn parents and advise how to manage

Rare, more serious reactions

– anaphylaxis (serious allergic reaction)

–

vaccine specific reactions

RARE, MORE SERIOUS REACTIONS

Simutaneous administration of Vaccine

A theoretical risk that administration of multiple live virus vaccine: OPV, MMR, and

varicella ) within 28 days of one another if not given on the same day will result in a

sub optimal immune response

No data to substantiate this

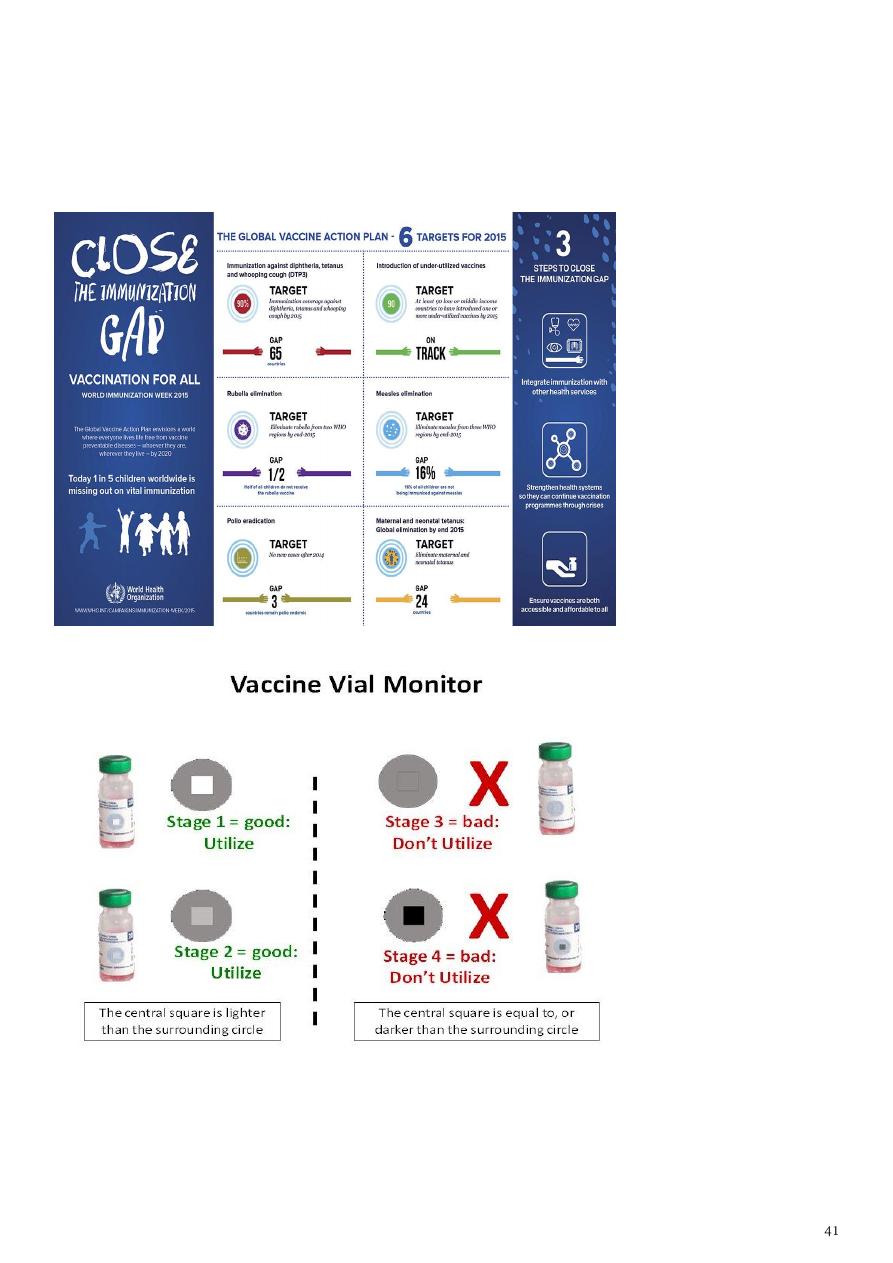

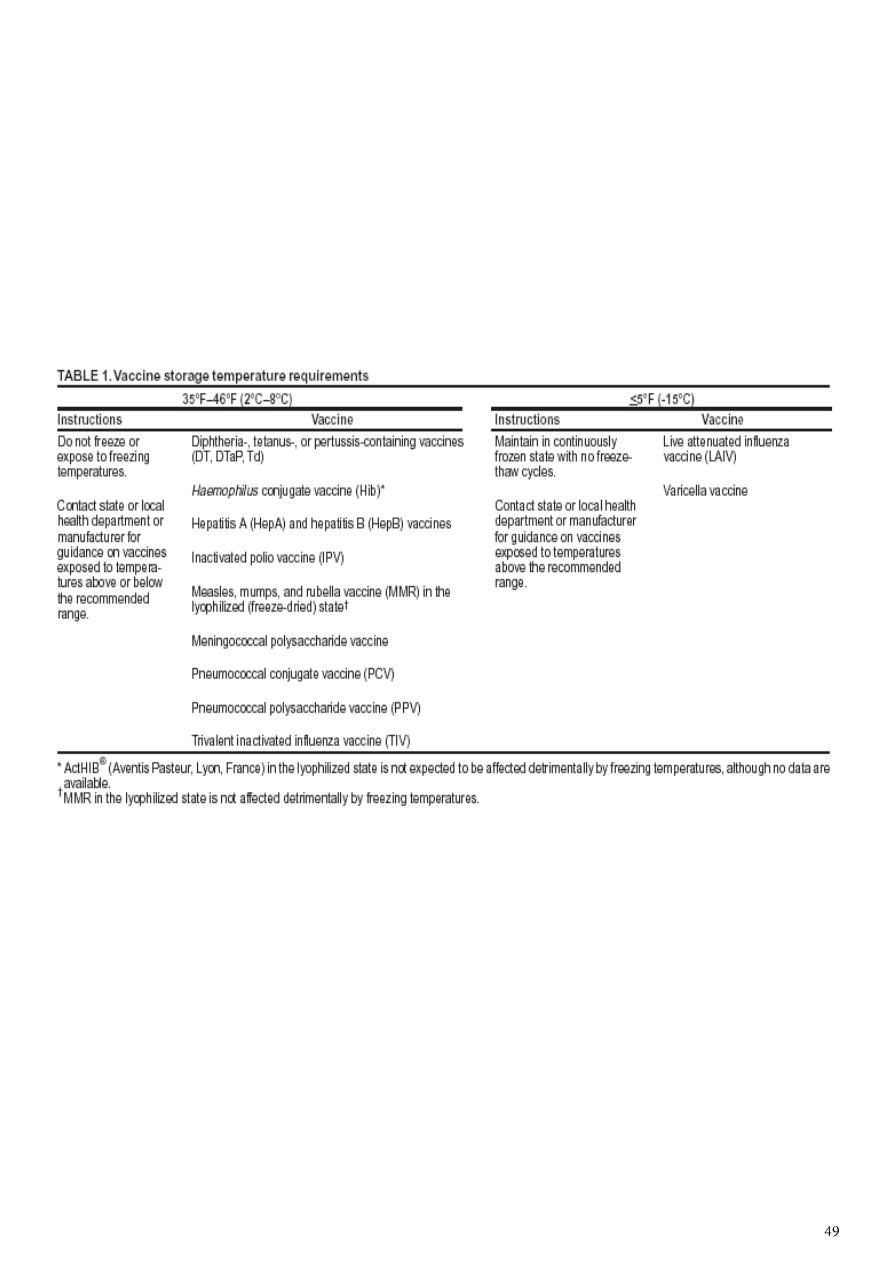

Vaccine Cold Chain

Maintaining proper vaccine temperatures during storage and handling to preserve

potency

The success of efforts against vaccine-preventable diseases is attributable in part to

proper storage and handling of vaccines.

Exposure of vaccines to temperatures outside the recommended ranges can affect

potency adversely, thereby reducing protection from vaccine-preventable diseases

Recommended Storage Temperatures

Table 5: Vaccination Schedule for Infants and Children 2012

Age Type of vaccine

0

-1 Week OPV0 dose , HepB1 , BCG

2 Months OPV1 , PENTA1,ROTA1

4 Months OPV2 , TETRA1,ROTA2

6 Months OPV3 , PENTA2,ROTA3

9 Months Measles + VIT A

15 Months MMR (Measles , Mumps , Rubella)

18 Months TETRA2, OPV First Booster dose + VIT A

4-6 Years DPT , OPV Second Booster dose + MMR2

Table 6: National Immunization Schedule for Infants and Children 2015

Age Type of vaccine

0-1 Week HepB1 , BCG + OPV0dose

2 Months HEXA 1,ROTA1 ,PREV13-1+OPV1

4 Months HEXA2,ROTA2,PREV13-2 + OPV2

6 Months HEXA3,ROTA3,PREV13-3 + OPV3

9 Months Measles + VIT A

15 Months MMR(Measles , Mumps , Rubella)

18 Months PENTA (DTP+IPV+Hib ) OPV + VIT A

4-6 Years TETRA (DTaP +IVP ) + OPV + MMR

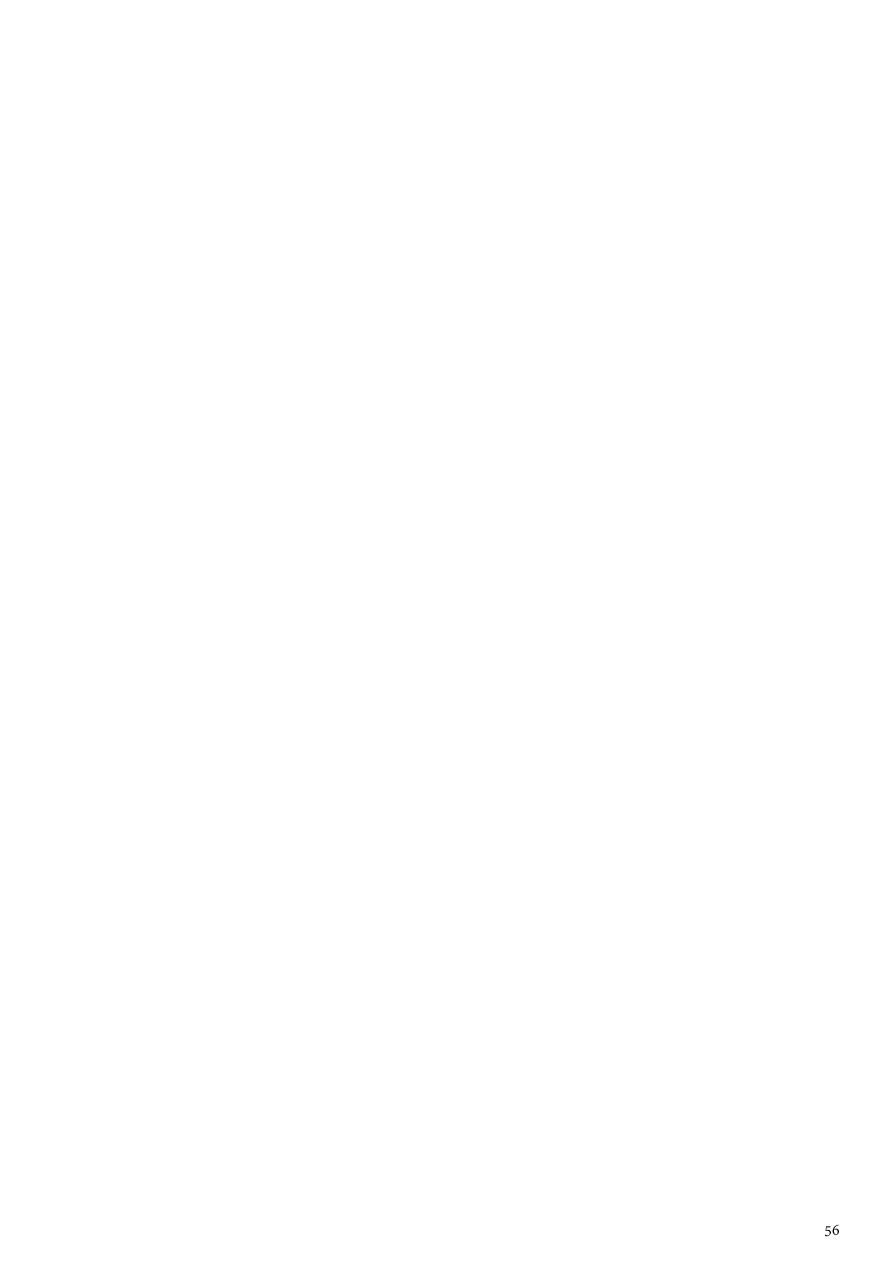

Seminar5

: Acute respiratory infection

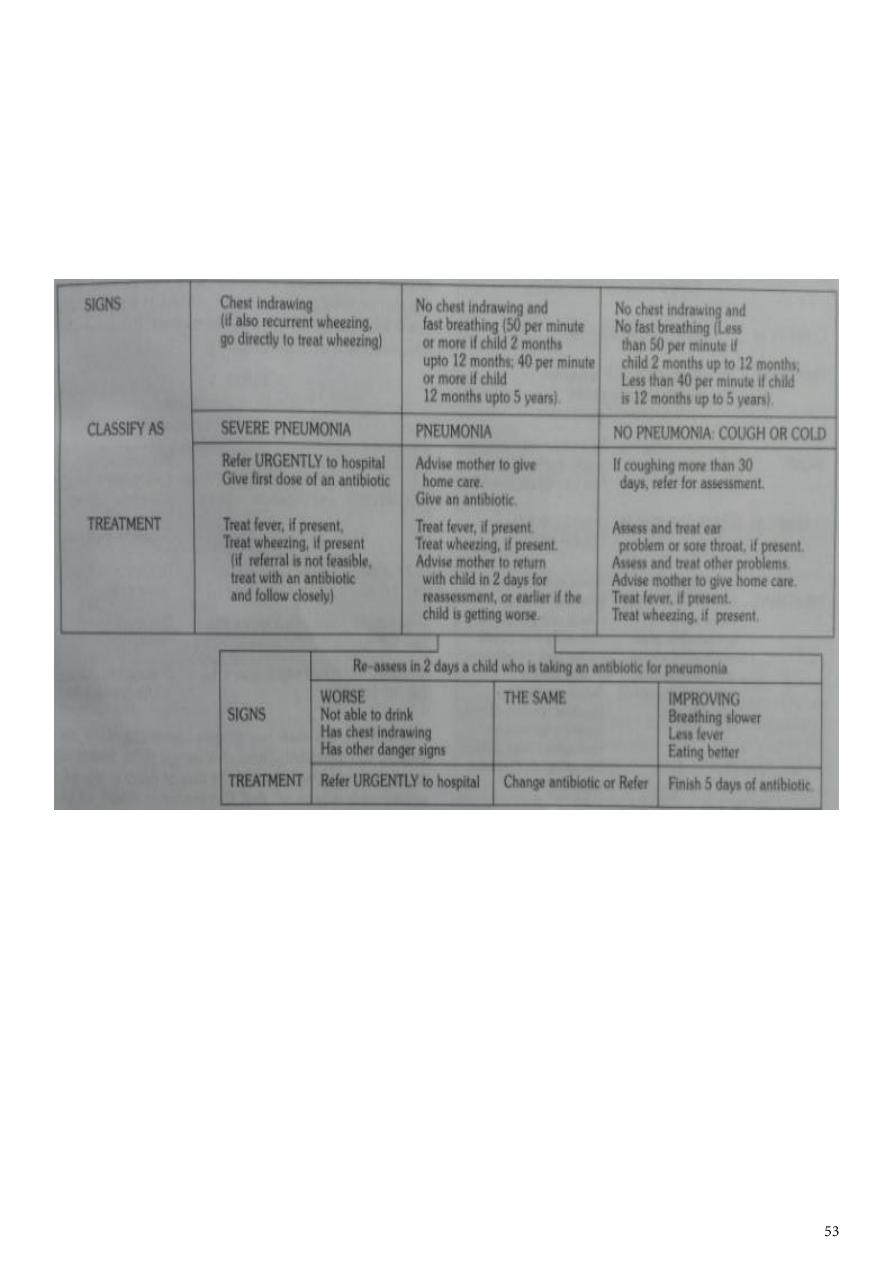

CLASSIFICATION

CHILD AGED 2 MONTHS TO 5 YEARS

Classifying the illness means making decisions about the type and severity of disease. The

sick child should be put into one of the four classifications:

VERY SEVERE DISEASE

SEVERE PNEUMONIA

PNEUMONIA(not severe)

NO PNEUMONIA

1. VERY SEVERE DISEASE

The danger signs and possible causes are:

a) Not able to drink: A child who is not able to drink could have severe pneumonia or

bronchiolotis, septicaemia, throat abscess, meningitis or cerebral malaria.

b) Convulsions, abnormally sleepy or difficult to wake: A child with these signs may have

severe pneumonia resulting in hypoxia, sepsis, cerebral malaria or meningitis. Meningitis

can develop as a complication of pneumonia or it can occur on its own.

c) Stridor in calm child: If a child has stridor when calm, the child may be in danger of life

threatening obstruction of the air-way from swelling of larynx, trachea or epiglottis.

d) Severe malnutrition: A severely malnourished child is at high risk of developing and dying

from pneumonia. In addition, the child may not show typical signs of the illness.

2. SEVERE PNEUMONIA

The most important signs to consider when deciding if the child has pneumonia are the

child’s respiratory rate, and whether or not there is chest indrawing may not have fast

breathing if the child becomes exhausted, and if the efforts needed to expand the lungs is

too great.

In such cases , chest indrawing maybe the only sign in a child with severe pneumonia. A

child with chest indrawing is at higher risk of pneumonia than a child with fast breathing

alone.

A child classified as having severe pneumonia also has other signs such as;

. Nasal flaring, when the nose widens as the child breaths in

. Grunting, the short sounds made with the voice when the child has difficulty in breathing

and

. Cyanosis, a dark bluish or purplish coloration of the skin caused by hypoxia

Children who have chest indrawing and a first episode of wheezing often have severe

pneumonia, however with recurrent wheezing do not have severe pnuemonia.

3. Pneumonia (not severe)

A child who has fast breathing and no chest indrawing is classified as having pneumonia(not

severe). Most children are classified in this category if they are brought early for treatment.

Fever , cough, tachpnoea, crackles , signs of consolidation , and constitutional symptoms

are the general clinical features seen in a patient suffering with pneumonia.

4. No pneumonia: cough or cold

Most children with a cough or difficult breathing do not have any danger signs

or signs of pneumonia ( chest indrawing or fast breathing). These children have

a simple cough or cold. They are classified as having ‘no pneumonia: cough or

cold’. They do not need any antibiotic. Majority of such cases are viral infections

where antibiotics are not effective. Normally a child with cold will get better

within 1-2 weeks.

MANAGEMENT OF PNEUMONIA IN A CHILD AGED 2 MONTHS UPTO 5 YEARS

Classifying illness of young infant

Infants less than 2 months of age are referred to as young infants. They have special

characteristics that must be considered when their illness is classified. They can become

sick and die very quickly from bacterial infections, are much less likely to cough with

pneumonia, and frequently have only non specific signs such as poor feeding, fever or

hypothermia.

1) Further mild chest indrawing is normal in young infants because their chest wall bones

are soft. The presence of these characteristics means that they will be classified and treated

differently from older children.

2) Many of the cases may have added risk factor of low birth weight. Such children are very

susceptible to temperature changes and even in tropical climates, death due to cold stress

or hypothermia are common.

3) In young infants the cut off point for fast breathing is 60 breaths per minute. Any

pneumonia in young infants is considered to be severe.

Some of the danger signs of very severe disease are:

a. convulsions, abnormally sleepy or difficult to wake: a young infant with

these signs may have hypoxia from pneumonia, sepsis or meningitis.

Malaria infection is unusual in children of this age, so antimalarial

treatment is not advised.

b. Stridor when calm: infections causing stridor viz diphtheria, bacterial

tracheitis, measles or epiglottitis are rare in young infants. A young infant

who has stridor should be classified as having very severe disease.

c. Stopped feeding well : a young infant who stops feeding well(i.e takes less

than half of the usual amount of milk) may have a serious infection and

should be classified as having very severe disease.

d. wheezing: it is uncommon in infants and is usually associated with

hypoxia.

e. Fever or low body temperature: fever(38 degree or more) is uncommon in

young infants and more often means a serious bacterial infection. It may

be the only sign of serious bacterial infection. Sometimes infection can

cause hypothermia.

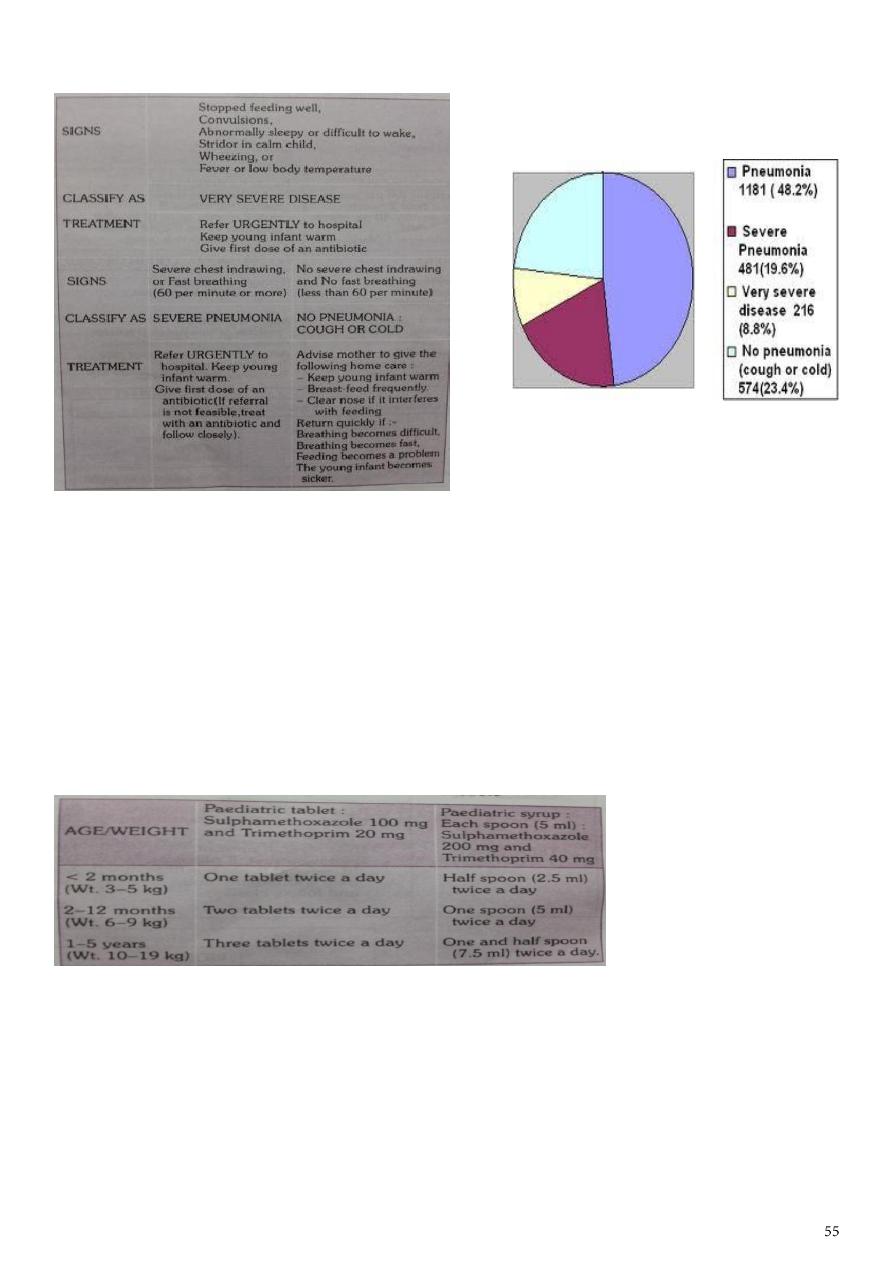

CLASSIFICATION AND MANAGEMENT OF ILLNESS IN YOUNG INFANTS

Treatment

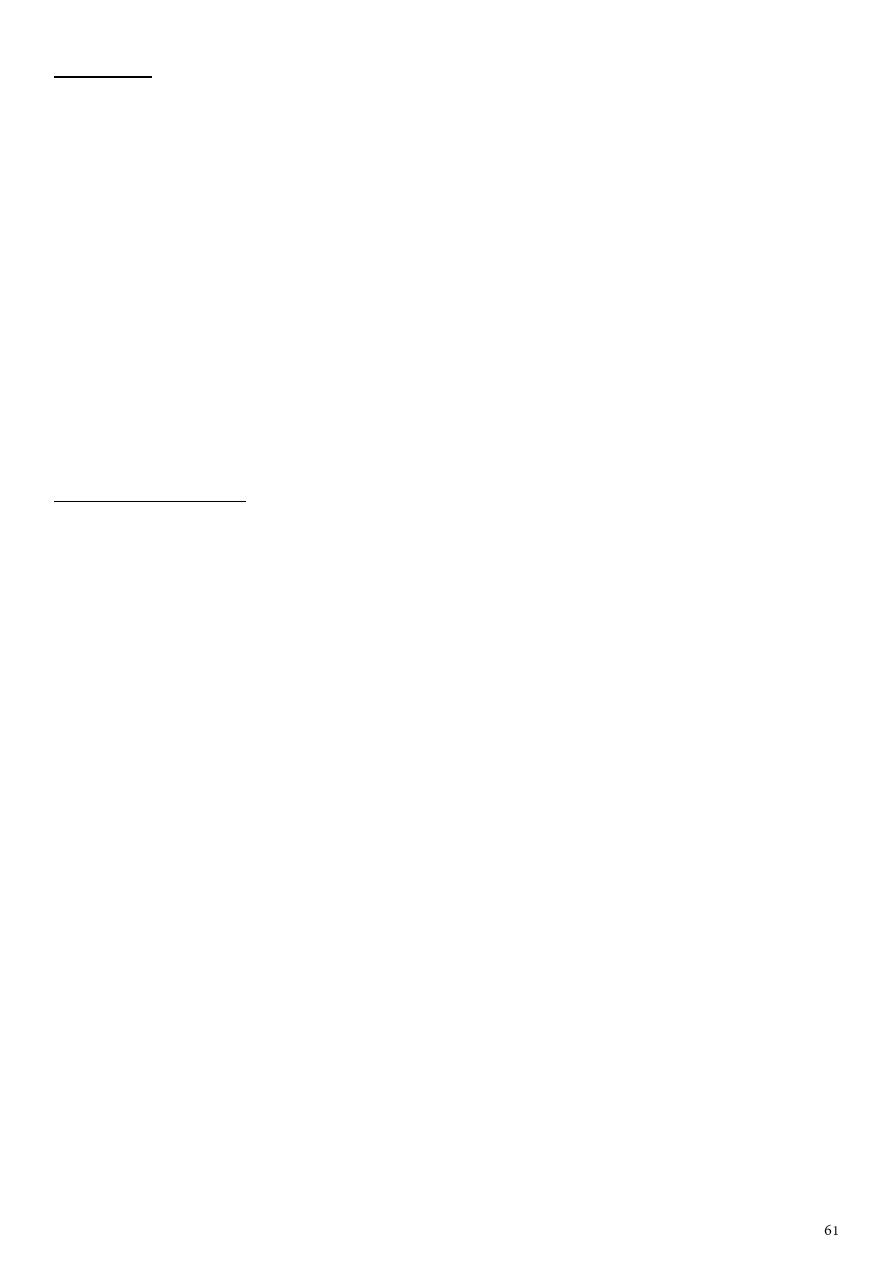

A. TREATMENT FOR CHILDREN AGED 2 MONTHS UPTO 5 YEARS

.PNEUMONIA (child with cough and fast breathing)

cotrimoxazole is the drug of choice for the treatment of pneumonia. Cure rates are 95%. It

is less expensive with few side effects and can be used safely by health workers at the

peripheral health facilities and at home by the mothers.

The condition of the child should be assessed after 48 hours.

Cotrimoxazole should be continued for another 3 days in children who show

improvement in clinical condition.

If there is no improvement in the condition then it should be continued for 48 hours

and then reassesed.

If at 48 hours or earlier the condition worsens, the child should be hospitalised

immediately.

Severe pneumonia (chest indrawing)

Children with severe pneumonia should be treated as inpatients with intramuscular

injections of benzylpenicilline(after test dose) ampicillin or chloramphenicol.

The condition of the child must be monitored everyday and reviewed after 48hrs for

antibiotic therapy.

Antibiotic therapy must be given for a minimum of 5 days and continued for atleast 3 days

after the child gets well.

Very severe disease

-Children with signs of very severe disease are in imminent danger of death and should be

treated in a health facility, with provision of oxygen therapy and intensive monitoring.

-Chloramphenicol IM is the doc in all such cases. Treat for 48 hrs ,if conditons improve

switch over to oral chloramphenicol. It should be given for a total of 10 days.

-If condition worsens or does not improve after 48hrs switch to IM injections of cloxacillin

and gentamicin.

B. PNEUMONIA IN YOUNG INFANTS UNDER 2 MONTHS OF AGE

The treatment in these condition is basically the same.

1.The child must be hospitaised.

2.Treatment with cotrimoxazole maybe started by the health worker before referring the

child.

3. If pneumonia is suspected in the child should be treated with IM injection of

bezylpenicilline or ampicillin, along with injection gentamycin.

Besides antibiotics, therapy for the associated conditions if any, must be instituted

immediately. The child must be kept warm and dry. Breast feeding must be promoted

strongly as the child who is not breast fed is at a much higher risk of diarrhoea.

Management of AURI (no pneumonia)

-> Many children with presenting symptoms of cough, cold and fever do not have

pnenumonia and do not require treatment with antibiotics.

->They are not recommended as majority of cases are caused by viruses and antibiotics are

not effective, they increase resistant strains and cause side effects while providing no

clinical benefit, and are wasteful expenditure.

->Symptomatic treatment and care at home is generally enough for such cases.

Seminar6

: ARI control and prevention

ARI control

Improving the primary medical care services and developing better methods for early

detection , treatment and prevention of acute respiratory infection is the best way to

control ARI

mortality rate due to pneumonia is reduced if treated correctly

Education of mothers about pneumonia because compliance with treatment and

seeking proper care when child suffers determine outcome of the disease

WHO recommendation for management of ARI

Clinical assesment

History taking and management are very important

1)age

2)feeding habits

3)fever

4)convulsions

5)irregular breathing

6)history of treatment during the illness

7)activity

Physical examination

1:count the breaths in one minute

Breathing count depends on the age of the child

Count respiratory rate for a minute

Fast breathing is present when RR is

-60 breaths /min or more in a child less than two months of age

-50/min or more in child aged 2months upto 12 months

-40 breaths/min or more in a child aged 12 months upto 5 years

Chest indrawing

Look for chest indrawing when child breaths IN

Child has indrawing if the lower chest wall goes in when the child breaths IN

Occurs when the effort required to breath in ,is much greater than normal

Stridor

Harsh noise while breathing IN is stridor

Occurs due to narrowing of trachea ,larynx or epiglottis

These conditions often called croup

Wheeze

A child with wheeze makes a soft whistling noise

OR

shows signs that breathing OUT is difficult

This is due to narrowing of the air passages

Fever

Check for body temperature

Cyanosis

Sign of hypoxia

Malnutrition

If malnutrition is present its high risk and case fatality rates are higher

In severely malnourished:

1) children with pneumonia, fast breathing and chest indrawing may not be evident

2)Impaired or absent response to hypoxia and a weak or absent cough reflex

3)Careful evaluation and mangement

ARI control programmes

ARI control in children

• ARI is an episode of acute symptoms & signs resulting from infection of

any part of respiratory tract & related structures

• Constitutes 22-66% of outpatients & 12-45% of inpatients

• The aim of the program is to identify children with ARI at the community

level by training the field workers to recognize easily & reliably identifiable

clinical signs of ARI & early reference

WHO protocol comprises 3 steps:

1. Case finding & Assessment

2. Case Classification

3. Institution of appropriate therapy

Step 1: Case finding & Assessment

• Cough & difficult breathing in children < 5 years age

• Fever is not an efficient criteria

Step 2: Case Classification

• Children grouped into 2:

Infants < 2months & Older children

• Specific signs to be looked: In younger children like feeding difficulty,

lethargy, hypothermia, convulsions

In infants < 2 months

• Pneumonia is diagnosed if RR 60/min with other clinical signs

• All should be hospitalized

• All should receive IV medications

• Minimum duration of 10 days

• Combination of Ampicillin & Gentamicin

Step 3:Institution of appropriate therapy

Antibiotics

Prevention of ARI

Breastfeeding infants exclusively (no other food or drinks, not even water)

for the first six months breast milk has excellent nutritional value and it

contains the mother’s antibodies which help to protect the infant from

infection.

Avoiding irritation of the respiratory tract by indoor air pollution, such as

smoke from cooking fires; avoid the use of dried cow dung as fuel for

indoor fires.

Immunization of all children with the routine Expanded Programme on

Immunization

Feeding children with adequate amounts of varied and nutritious food to

keep their immune system strong.

control the spread of respiratory bacteria by educating parents to avoid

contact as much as possible between their children and patients who have

ARIs.

people with ARIs should cough or sneeze away from others, hold a cloth

to the nose and mouth to catch the airborne droplets when coughing or

sneezing

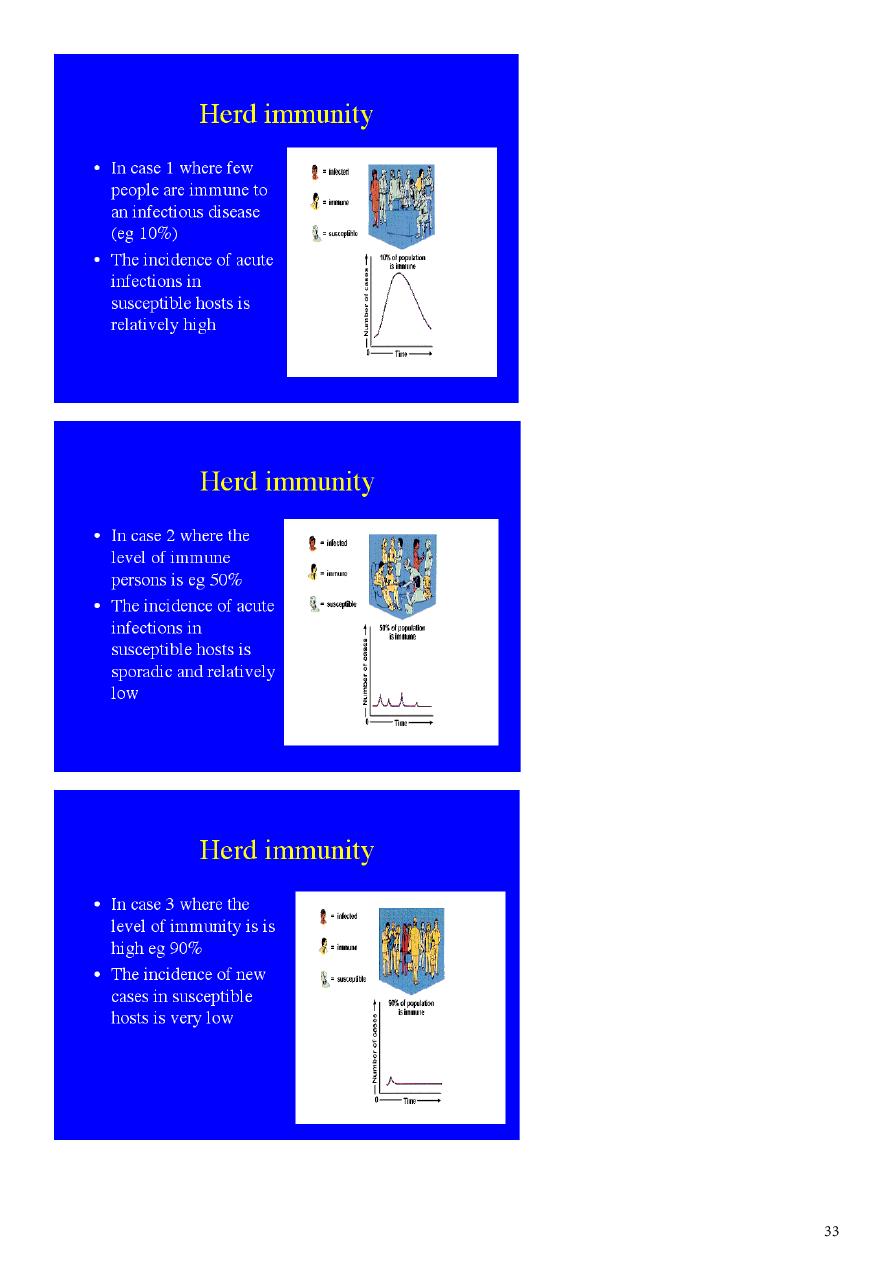

Immunization also increases control, by reducing the reservoir of

infection in the community and increasing the level of herd immunity

Immunization

Measles vaccine

Pneumonia is a serious complication of measles

Reducing the incidence of measles helps reduce death from pneumonia

Live attenuated vaccine

Freeze dried product

0.5ml dose subcutaneously also effective intramuscularly

Schedule :9 th month

HIB vaccine

Haemophilus influenza B most important cause of death due to meningitis and

pneumonia in developing countries

Available for more than a decade

Expensive

Included in the immunization schedule

combined preparation with DPT and poliomyelitis

Three or four doses are given dependin on type of vaccine

Schedule : 6 ,10, 14 weeks booster dose 12-18 months

Vaccine is not offered to children more than 24 months

Pneumococcal vaccine

A)ppv23: polysaccharide non conjugate vaccine containing capsular antigen of 23

serotypes against this infection

Children under two years and immunocompromised do not respond well to this

vaccine

Select groups –sickle cell disease ,chronic heart disease , DM, organ transplants etc

Dose -0.5ml

Administration – intramuscular in the deltoid

Pcv-7: pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

New vaccine suitable for infants and toddlers

It is included in the immunization schedule

Induces a t- cell dependent immune response

Prevents pneumococcal pneumonia and meningitis moderately effective against

otitis media

dose- 1)6,10,14 weeks ,booster after 12 months

OR

2)2, 4,6 months and booster after 12 months

administration-intramuscular

Seminar7

: Neonatal emergencies