1

Fifth stage

Ophthalmology

Lec- خيرمن

هللا

د.نزار حديد

28/11/2015

BACTERIAL KERATITIS

Pathogenesis

A host of bacteria may infect the cornea.

• Staphylococcus epidermidis

• Staphylococcus aureus

• Streptococcus pneumoniae

• Coliforms

• Pseudomonas

• Haemophilus

Some are found on the lid margin as part of the normal flora. The conjunctiva and cornea are

protected against infection by:

• blinking

• washing away of debris by the flow of tears;

• entrapment of foreign particles by mucus;

• the antibacterial properties of the tears;

• the barrier function of the corneal epithelium (Neisseria gonnorrhoea is the only

organism that can penetrate the intact epithelium).

Predisposing causes

of bacterial keratitis include:

• keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eye);

• a breach in the corneal epithelium (e.g. following trauma);

• contact lens wear;

• prolonged use of topical steroids.

2

Symptoms and signs

These include:

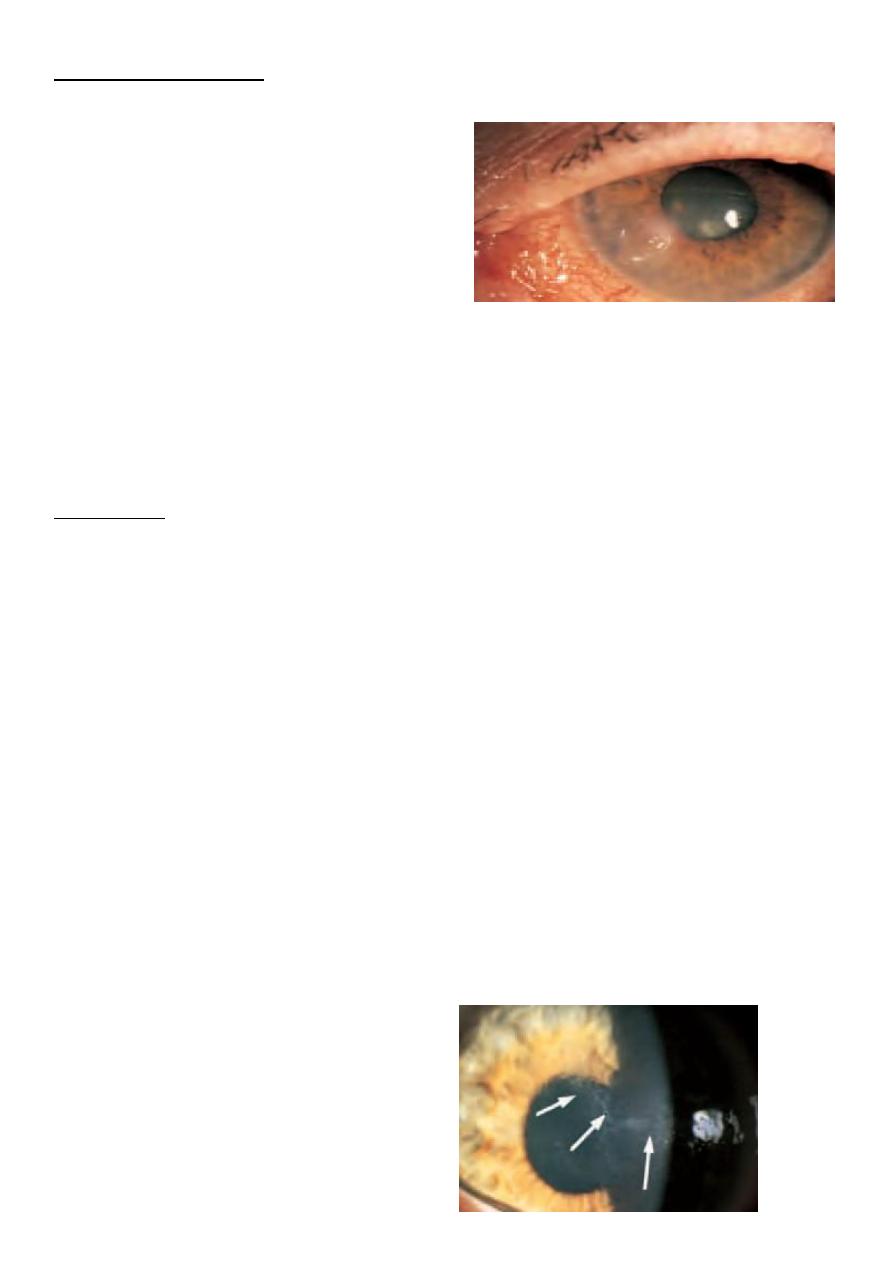

• pain, usually severe unless the cornea is

anaesthetic;

• purulent discharge;

• ciliary injection;

• visual impairment (severe if the visual

axis is involved);

• hypopyon sometimes (a mass of white cells collected in the anterior chamber; see pp.

91–92);

• a white corneal opacity which can often be seen with the naked eye

Treatment

Scrapes are taken from the base of the ulcer for Gram staining and culture. The patient is

then treated with intensive topical antibiotics often with dual therapy (e.g. cefuroxime

against Gram +ve bacteria and gentamicin for Gram —ve bacteria) to cover most organisms.

The use of fluoro- quinolones (e.g. Ciprofloxacin, Ofloxacin) as a monotherapy is gaining

popularity. The drops are given hourly day and night for the first couple of days and reduced

in frequency as clinical improvement occurs. In severe or unresponsive disease the cornea

may perforate. This can be treated initially with tissue adhesives (cyano-acrylate glue) and a

subsequent corneal graft. A persistent scar may also require a corneal graft to restore vision.

ACANTHAMOEBA KERATITIS

This freshwater amoeba is responsible for infective keratitis. The infection is becoming

more common due to the increasing use of soft contact lenses. A painful keratitis with

prominence of the corneal nerves results. The amoeba can be isolated from the cornea (and

from the contact lens case) with a scrape and cultured on special plates impregnated with

Escherichia coli. Topical chlorhexidine, polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) and

propamidine are used to treat the condition.

3

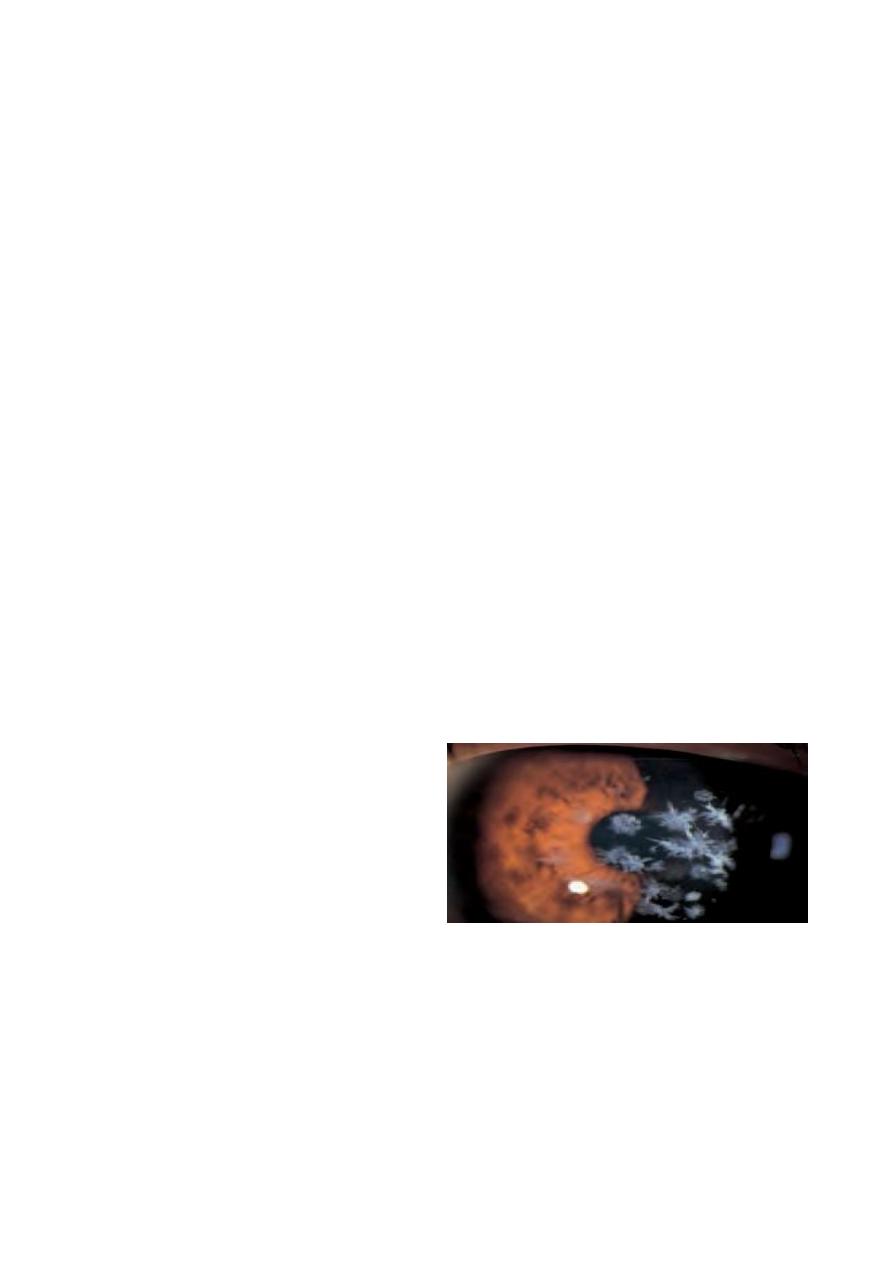

FUNGAL KERATITIS

more common in warmer climates. It should be considered in:

• lack of response to antibacterial therapy in corneal ulceration;

• cases of trauma with vegetable matter;

• cases associated with the prolonged use of steroids.

The corneal opacity appears fluffy and satellite lesions may be present. Liquid and solid

Sabaroud’s media are used to grow the fungi. Incubation may need to be prolonged.

Treatment requires topical antifungal drops such as pimaricin 5%.

INTERSTITIAL KERATITIS

This term is used for any keratitis that affects the corneal stroma without epithelial

involvement. Classically the most common cause was syphillis, leaving a mid stromal scar

with the outline (‘ghost’) of blood vessels seen. Corneal grafting may be required when the

opacity is marked and visual acuity reduced.

Corneal dystrophies

These are rare inherited disorders. They affect different layers of the cornea and often affect

corneal transparency. They may be divided into:

• Anterior dystrophies involving the epithelium. These may present with recurrent

corneal erosion.

• Stromal dystrophies presenting with visual loss. If very anterior they may cause

corneal erosion and pain.

• Posterior dystrophies which affect the endothelium and cause gradual loss of vision

due to oedema. They may also cause pain due to epithelial erosion.

4

Disorders of shape

KERATOCONUS

This is usually a sporadic disorder but may occasionally be inherited. Thinning of the centre

of the cornea leads to a conical corneal distortion. Vision is affected but there is no pain.

Initially the associated astigmatism can be corrected with glasses or contact lenses. In severe

cases a corneal graft may be required.

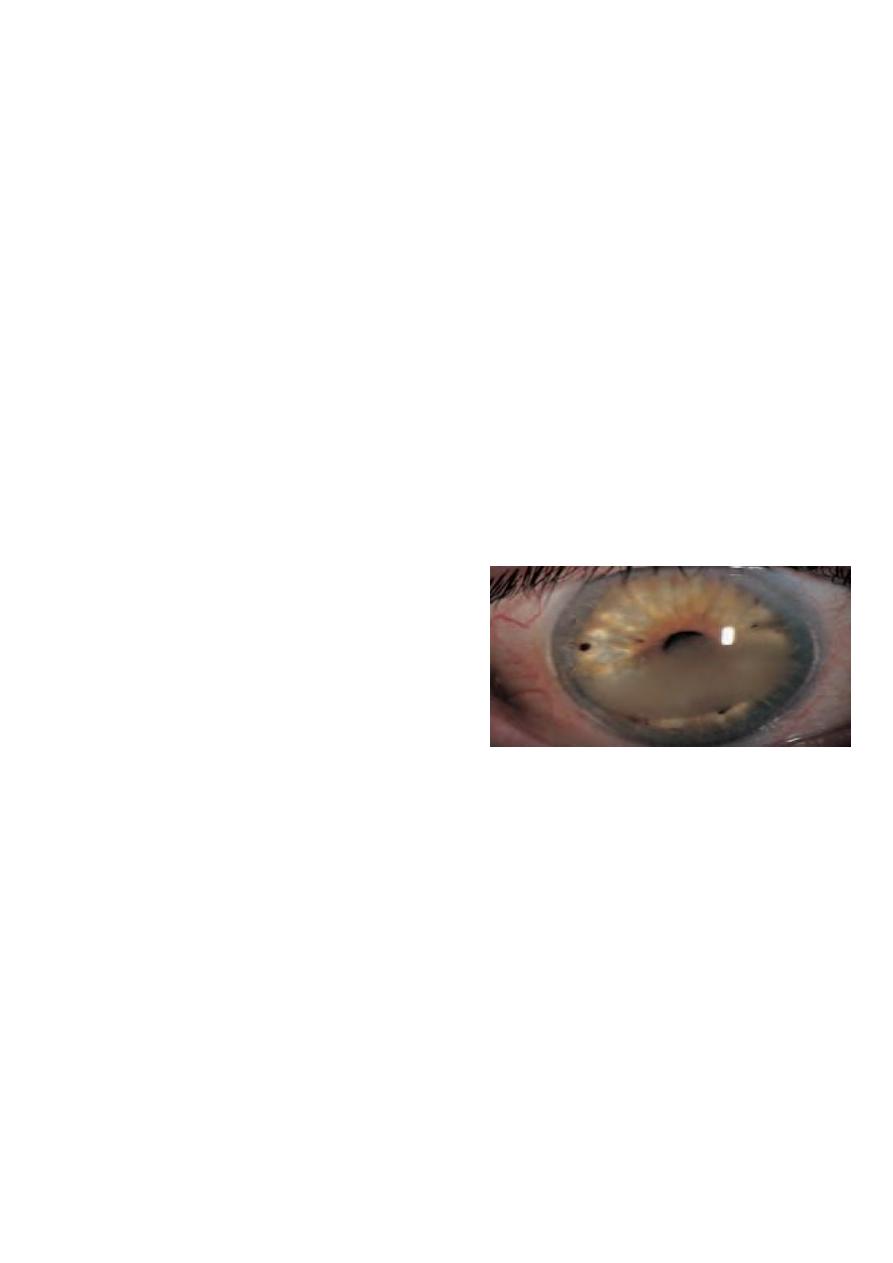

Central corneal degenerations

- BAND KERATOPATHY

the subepithelial deposition of calcium phosphate in the exposed part of the cornea. It is

seen in eyes with chronic uveitis or glaucoma. It can also be a sign of systemic

hypercalcaemia as in hyperparathyroidism or renal failure. and may cause visual loss or

discomfort if epithelial erosions form over the band. If symptomatic it can be scraped off

aided by a chelating agent such as sodium edetate.The excimer laser can also be effective in

Degenerative Changes of Cornea

Keratoconus:

القرنية المخروطية

• Progressive coning of corneal due to thinning of inf. Paracentral stroma.

• Usually bilateral but may be asymmetrical

• Start in teens age (puberty), more in females.

• Associations:

1- Vernal catarrh

2- Atopic dermatitis

3- Down syndrome

4- Turner syndrome

5- Marfan syndrome

6- Ehler Danlos Syndrome

5

Present

: Progressive blurring of vision (irregular myopic astigmatism & corneal opacities).

O/E:

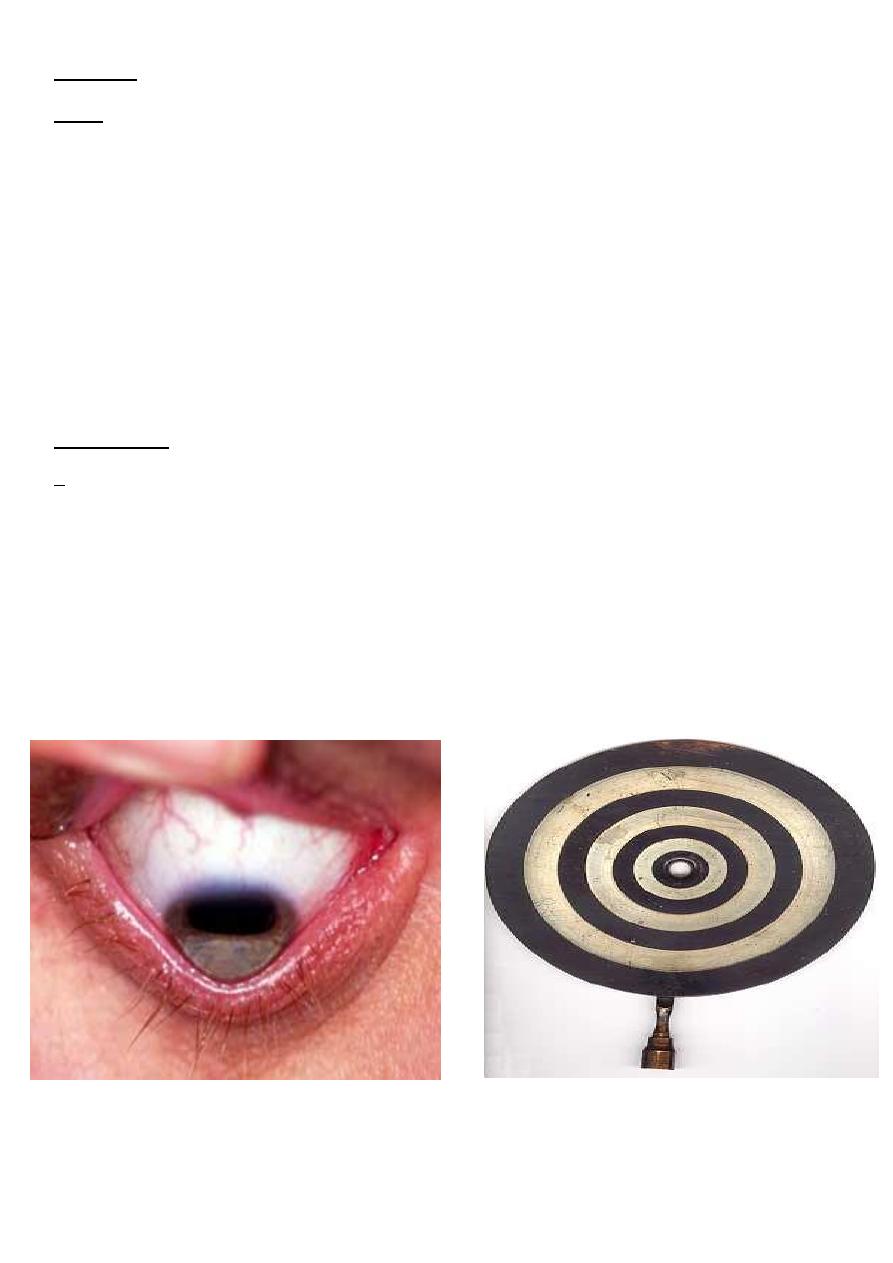

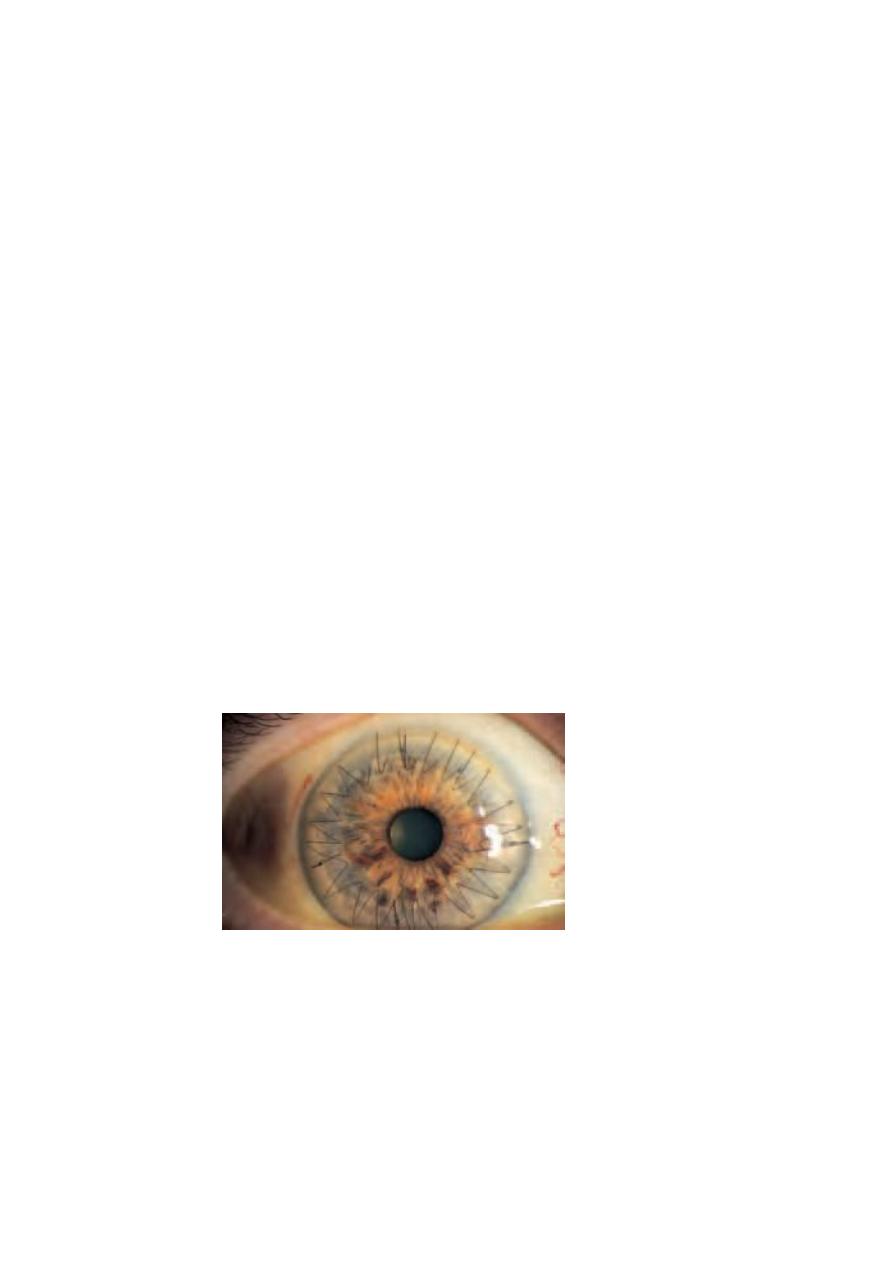

1. Thinning & forward bowing of inf. Paracentral cornea stroma (slit lamp ex.)

2. Brownish ring (Fleischer) around the base of cone due to hemosiderin deposit.

3. Distortion of the corneal light reflection (placido disc).

4. Altered ophthalmoscopic & retinoscopic light reflexes.

5. Munson’s sign (indentation of the lower lid by the conical corneal when patient looks

downward).

6. Acute hydrops=stromal oedema due to rupture descemet membrane.

Nowadays ,it is mostly diagnosed by corneal topography examination during the preoprative

assessment of refractive surgery

Treatment

:

1- Corneal Collagen Cross-linking, in early cases to arrest the disease

2- Glasses

3- Contact lenses (Rigid)

4- Intra-stromal corneal rings

5- Penetrating keratoplasty or Lamellar keratoplasty..in advanced cases or corneal scarring

Munson’s sign Placido disc

treating these patients by ablating the affected cornea. The lesion is then more likely to

occupy the 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock positions of the limbal cornea.

6

Peripheral corneal degenerations

- CORNEAL THINNING

A rare cause of painful peripheral corneal thinning is Mooren’s ulcer, a condition with an

immune basis. Corneal thinning or melting can also be seen in collagen diseases such as

rheumatoid arthritis and Wegener’s granulomatosis. Treatment can be difficult and both sets

of disorder require systemic and topical immunosuppression. Where there is an associated

dry eye it is important to ensure adequate corneal wetting and corneal protection (see pp.

59–60).

- LIPID ARCUS

This is a peripheral white ring-shaped lipid deposit, separated from the limbus by a clear

interval. It is most often seen in normal elderly people (arcus senilis) but in young patients it

may be a sign of hyperlipidaemia. No treatment is required.

Corneal grafting

Donor corneal tissue can be grafted into a host cornea to restore corneal clarity or repair a

perforation. Donor corneae can be stored and are banked so that corneal grafts can be

performed on routine operating lists. The avascular host cornea provides an immune

privileged site for grafting,

with a high success rate. Tissue can be HLA-typed for grafting of vascular- ized corneae at

high risk of immune rejection although the value of this is still uncertain. The patient uses

steroid eye drops for some time after the operation to prevent graft rejection. Complications

such as astigmatism can be dealt with surgically or by suture adjustment.

7

GRAFT REJECTION

Any patient who has had a corneal graft and who complains of redness, pain or visual loss

must be seen urgently by an eye specialist, as this may indicate graft rejection. Examination

shows graft oedema, iritis and a line of activated T-cells attacking the graft endothelium.

Intensive topical steroid application in the early stages can restore graft clarity.

SCLERA

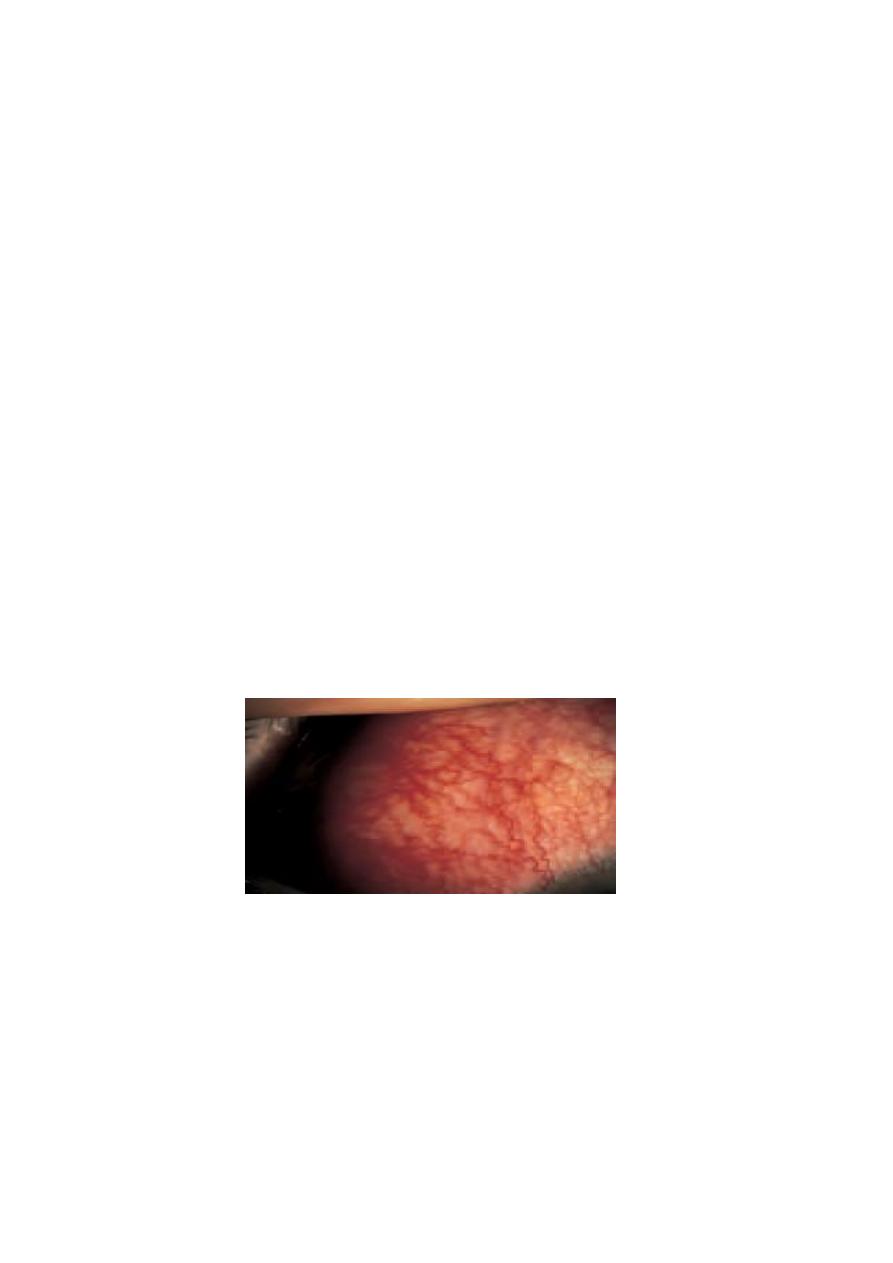

- EPISCLERITIS

This inflammation of the superficial layer of the sclera causes mild discomfort. It is rarely

associated with systemic disease. It is usually self-limiting but as symptoms are tiresome,

topical anti-inflammatory treatment can be given. In rare, severe disease, systemic non-

steroidal anti-inflammatory treatment may be helpful.

- SCLERITIS

This is a more severe condition than episcleritis and may be associated with the collagen-

vascular diseases, most commonly rheumatoid arthritis. It is a cause of intense ocular pain.

Both inflammatory areas and ischaemic areas of the sclera may occur. Characteristically the

affected sclera is swollen. The following may complicate the condition:

• scleral thinning (scleromalacia), sometimes with perforation;

• keratitis;

• uveitis;

• cataract formation;

• glaucoma.

Treatment may require high doses of systemic steroids or in severe cases cytotoxic therapy

and investigation to find any associated systemic disease.

8

Scleritis affecting the posterior part of the globe may cause choroidal effusions or simulate a

tumour.

• Avoid the unsupervised use of topical steroids in treating ophthalmic conditions since

complications may be serious.

• In contact lens wearers a painful red eye is serious; it may imply an infective keratitis.

• Redness, pain and reduced vision in a patient with corneal graft suggests rejection and

is an ophthalmic emergency

B

R