1

Lecture 3

Replication:Virus Growth Cycle

Viruses multiply only in living cells. The host cell must provide the energy and synthetic

machinery and the low-molecular-weight precursors for the synthesis of viral proteins

and nucleic acids. The viral nucleic acid carries the genetic specificity to code for all the

virus-specific macromolecules in a highly organized fashion.

Soon after interaction with a host cell, the infecting virion is disrupted and its measurable

infectivity is lost. This phase of the growth cycle is called the eclipse period; followed by

an interval of rapid accumulation of infectious progeny virus particles. In some cases, as

soon as the viral nucleic acid enters the host cell, the cellular metabolism is redirected

exclusively toward the synthesis of new virus particles and the cell will be destroyed.

After the synthesis of viral nucleic acid and viral proteins, the components assemble to

form new infectious virions (from modest numbers to more than 100,000 particles)

during (from 6–8 hours (picornaviruses) to more than 40 hours (some herpesviruses).

Abortive infections fail to produce infectious progeny, either because the cell may be

nonpermissive and unable to support the expression of all viral genes or because the

infecting virus may be defective, lacking some functional viral gene.

A latent infection may ensue, with the persistence of viral genomes, the expression of no

or a few viral genes, and the survival of the infected cell. In other cases, the metabolic

processes of the host cell are not altered significantly, although the cell synthesizes viral

proteins and nucleic acids, and the cell is not killed.

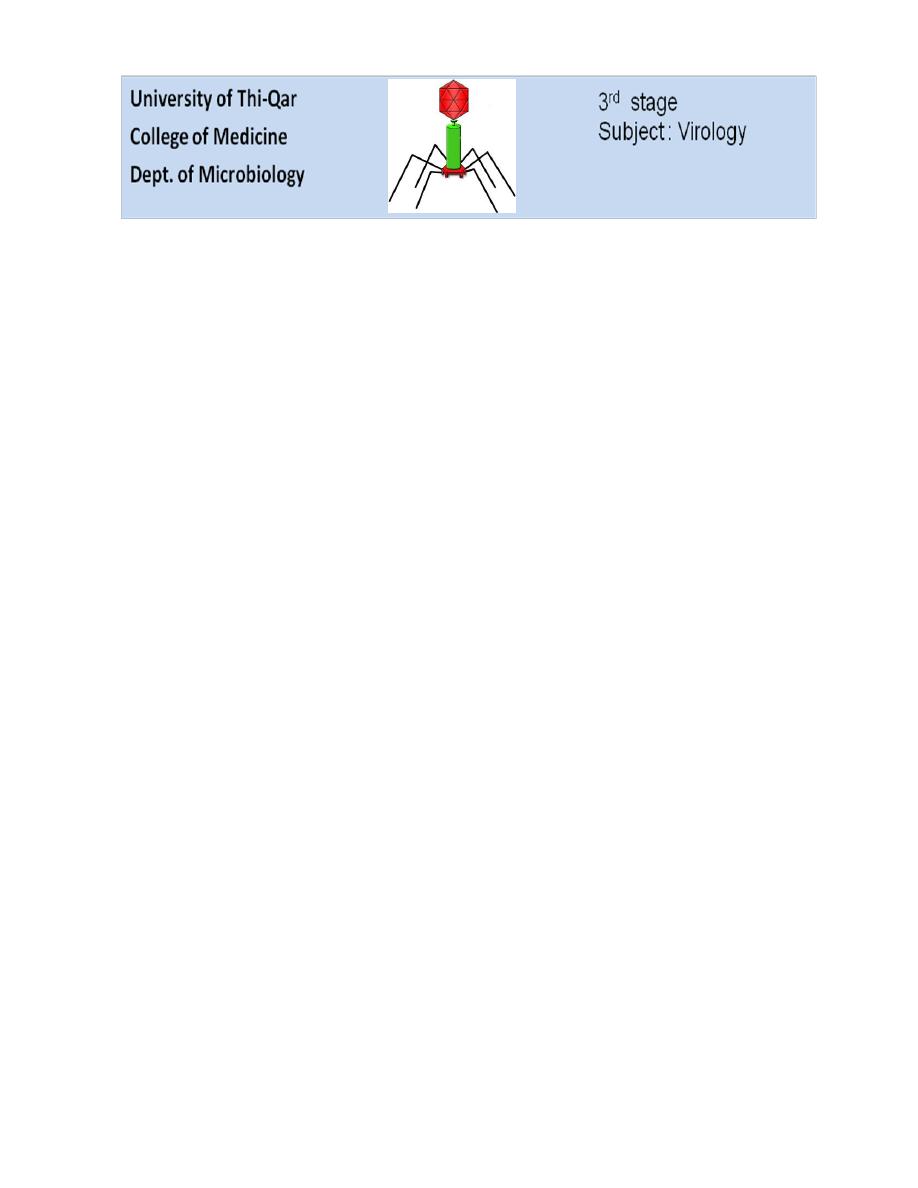

General Steps in Viral Replication Cycle

The steps in viral infection are

1. Attachment

2. Penetration

3. Uncoating

2

4. Gene expression and Synthesis of viral components

5. Assembly

6. Release

VIRAL

LIFE

CYCLE

ATTACHMENT

PENETRATION

HOST

FUNCTIONS

ASSEMBLY

(MATURATION)

Transcription

REPLICATION

RELEASE

UNCOATING

Translation

MULTIPLICATION

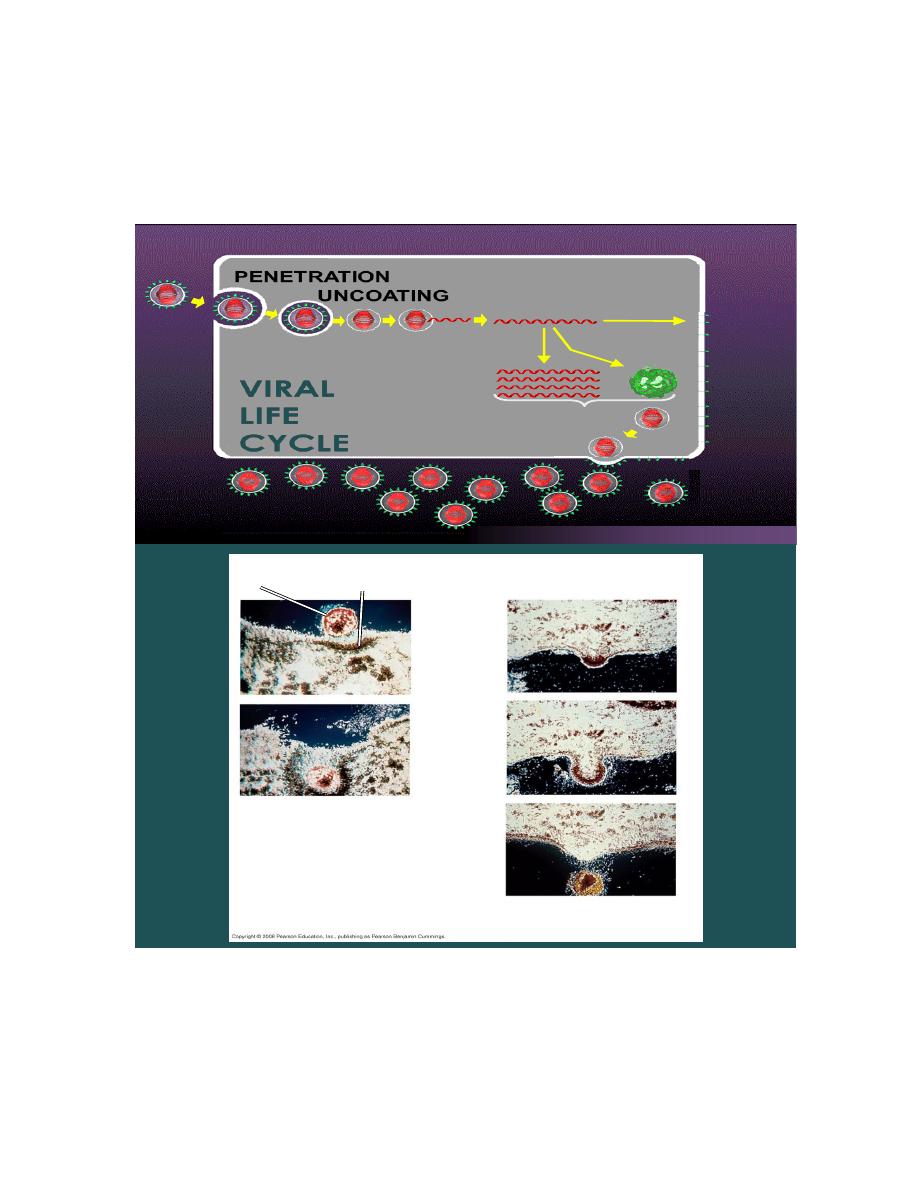

HIV

Membrane of

white blood cell

HIV entering a cell

0.25 µm

New HIV leaving a cell

The reproductive cycle of HIV, the retrovirus that causes AIDS

3

1- Attachment )Adsorption( interaction of a virion with a specific receptors generally

glycoproteins on the surface of a cell. In some cases the virus binds protein sequences

(eg, picornaviruses) and in others oligosaccharides (eg, orthomyxoviruses and

paramyxoviruses). For example,

A- HIV virus binds to the CD4 receptor on cells of the immune system,

B- Rhinoviruses bind ICAM-1,

C- Epstein-Barr virus recognizes the CD21 receptor on B cells.

Not all cells in a susceptible host will express the necessary receptors; for example,

poliovirus is able to attach only to cells in the central nervous system and intestinal tract

of primates. Each susceptible cell may contain up to 100,000 receptor sites for a given

virus. The attachment step may initiate irreversible structural changes in the virion.

Attachment

27

2- Penetration or Entry: After binding, the cell membrane invaginates around the

adsorped virus particle, the virus particle is then engulfed by the cell. In some systems,

this is accomplished by receptor-mediated endocytosis, with uptake of the ingested virus

particles within endosomes. There are also examples of direct penetration of virus

particles across of or fusion of the virion envelope with the plasma membrane.

3-Uncoating: occurs shortly after penetration. The protein coat of virus is removed by

the host cell enzymes. After that, the genome may be released as free nucleic acid

(picornaviruses) or as a nucleocapsid (reoviruses). The infectivity of the parental virus is

lost at the uncoating stage.

4

Penetration

u

and

ncoating

4- Gene expression and synthesis of viral components: The essential point in viral

replication is that specific mRNAs must be transcribed from the viral nucleic acid for

successful expression and duplication of genetic information. Once this accomplished,

viruses use cell components to translate the

mRNA

In DNA viruses

mRNA can be formed using the host’s own RNA polymerase to

transcribe directly from the viral DNA .

In RNA viruses , the host polymerase does not work from RNA molecules...therefore

they produce their mRNA by several different routes:

1- In ds RNA viruses: one strand is first transcribed by viral polymerase into mRNA.

2- In ss RNA viruses....there are three routes to the formation of mRNA:

A- If the ss RNA virus has the same base sequence as that required (+ve sense(….it

can be used directly as mRNA

B- B-If the strand has not the same base sequence as that required for translation (-ve

sense(…it must be transcribed into a positive sense strand which can then act as

mRNA.

C- In reverse transcribed RNA (RT(, the positive sense ss is first made into a

negative sense ss DNA using the viral reverse transcriptase enzyme.

5

Once viral mRNA has been formed, translation occurs in the host cytoplasm using host

ribosome to synthesize viral proteins......At this phase, the virus components appear as

separate NA and a separate protein coats.

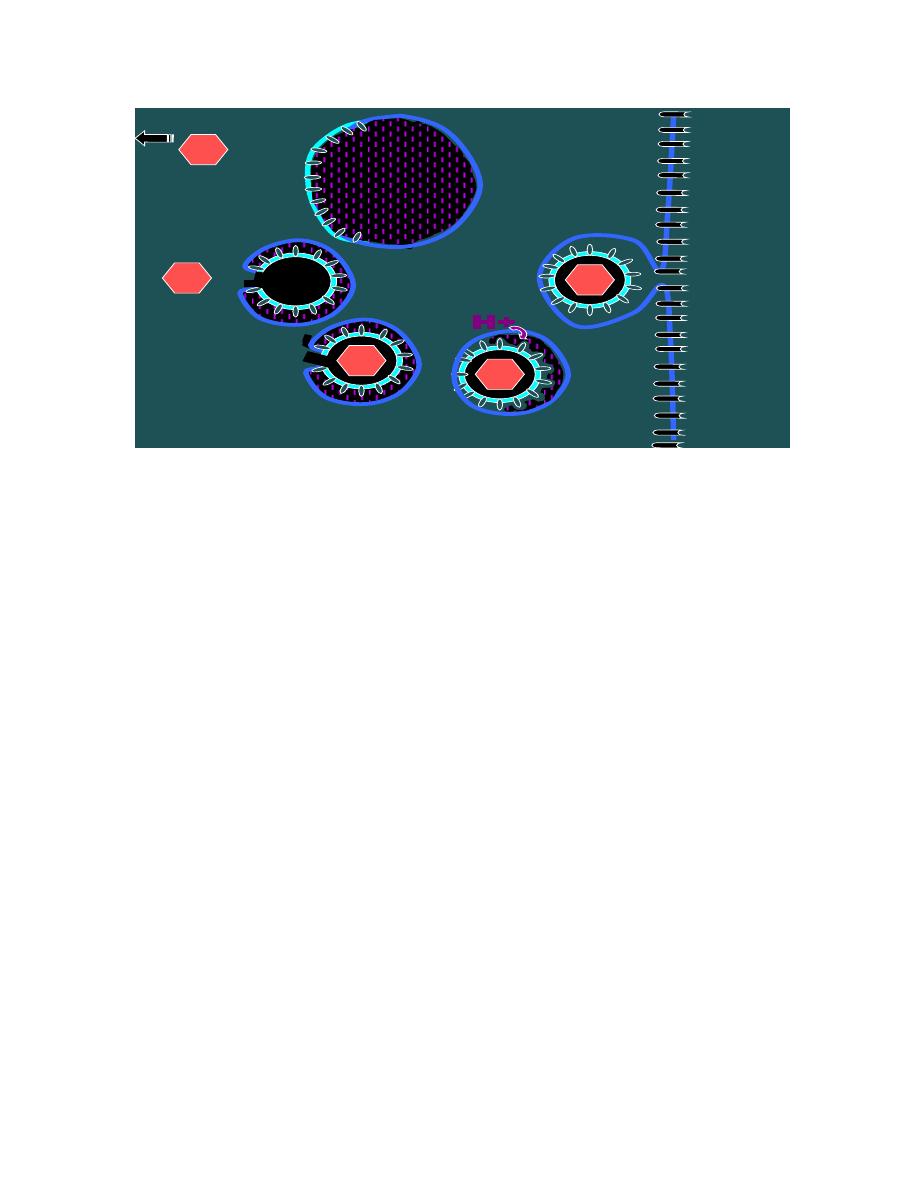

5- Assembly: viral NA enters into a capsid to be assembled into mature infective virus

)virion(

6- Release: the virus is released from the cell either in a dramatic burst (poliovirus(

or in a steady stream from the cell structure (Herpesvirus and myxovirus(

.

6

Morphogenesis and Release

Newly synthesized viral genomes and capsid polypeptides assemble together to form

progeny viruses. In general, non enveloped viruses accumulate in infected cells, and the

cells eventually lyse and release the virus particles.

Enveloped viruses mature by a budding process. Virus-specific envelope glycoproteins

are inserted into cellular membranes; viral nucleocapsids then bud through the membrane

at these modified sites and in so doing acquire an envelope. Enveloped viruses are not

infectious until they have acquired their envelopes. Therefore, infectious progeny virions

typically do not accumulate within the infected cell.

Viral maturation is sometimes an inefficient process. Excess amounts of viral

components may accumulate and be involved in the formation of inclusion bodies in the

cell. As a result of the profound deleterious effects of viral replication, cellular cytopathic

effects eventually develop and the cell dies. Virus-induced mechanisms may regulate

apoptosis, Programmed Cell Death that makes cells undergo self-destruction. Some virus

infections delay early apoptosis, which allows time for the production of high yields of

progeny virus. Additionally, some viruses actively induce apoptosis at late stages which

would facilitate spread of progeny virus to new cells.

Modes of Transmission of Viruses

Viruses may be transmitted in the following ways:

(1) Direct transmission from person to person by contact. The major means of

transmission may be by droplet or aerosol infection (eg, influenza, measles, smallpox);

the fecal-oral route (eg, enteroviruses, rotaviruses, infectious hepatitis A); sexual contact

(eg, hepatitis B, herpes simplex type 2, human immunodeficiency virus); hand-mouth,

hand-eye, or mouth-mouth contact (eg, herpes simplex, rhinovirus, Epstein-Barr virus);

or by transfusion of contaminated blood (eg, hepatitis B, human immunodeficiency

virus).

(2) Transmission from animal to animal, with humans an accidental host. Spread may be

by bite (rabies) or by droplet or aerosol infection from rodent-contaminated quarters (eg,

arenaviruses, hantaviruses).

(3) Transmission by an arthropod vector (togaviruses, flaviviruses, and bunyaviruses).

Emerging Viral Diseases

.

7

Combinations of factors contribute to disease emergence include:

(1) Environmental changes (deforestation, damming or other changes in water

ecosystems, flood or drought, famine nstarvatio

)

).

(2) Human behavior (sexual behavior, drug use, outdoor recreation).

(3) Socioeconomic and demographic phenomena (war, poverty, population growth and

migration, urban decay).

(4) Travel and commerce (highways, international air travel).

(5) Food production (globalization of food supplies, changes in methods of food

processing and packaging);

(6) Health care (new medical devices, blood transfusions, organ and tissue

transplantation, drugs causing immunosuppression, widespread use of antibiotics);

(7) Microbial adaptation (changes in virulence, development of drug resistance, cofactors

in chronic diseases).

(8) Public health measures (inadequate sanitation and vector control measures, lack of

trained personnel in sufficient numbers).

Examples of emerging viral infections in different regions of the world include Ebola

virus, Nipah virus, hantavirus pulmonary disease, HIV infection, dengue hemorrhagic

fever, West Nile virus, Rift Valley fever, and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (the

latter a prion disease).

Because the numbers of available human donor organs cannot meet the needs of all

waiting patients, xenotransplantation of nonhuman primate and porcine organs is

considered an alternative. Concerns exist about the potential accidental introduction of

new viral pathogens from the donor species into humans.

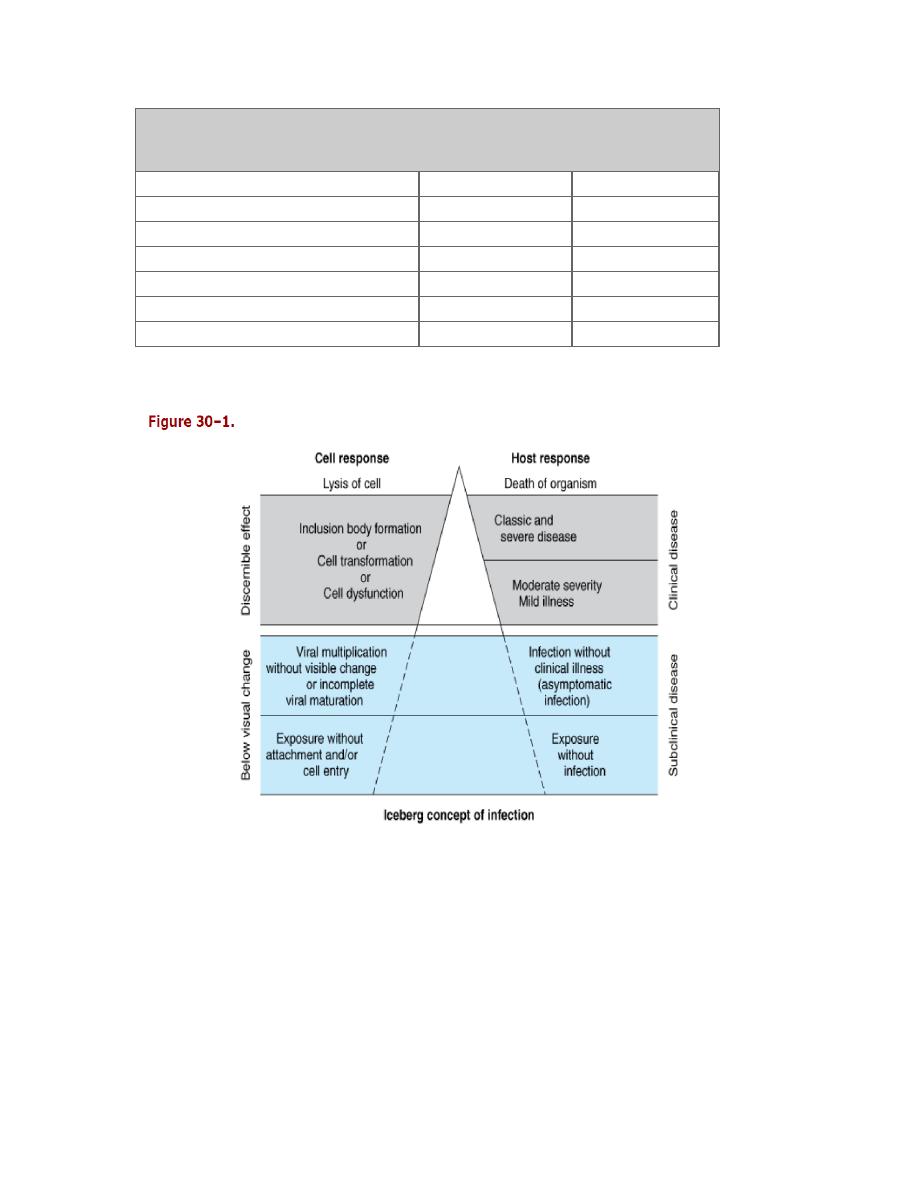

Principles of Viral Diseases

Viral disease is some abnormality that results from viral infection of the host organism.

Viral infections that fail to produce any symptoms in the host are said to be inapparent

(subclinical). In fact, most viral infections do not result in the production of disease

(Figure 30–1).

Important principles that pertain to viral disease include the following:

(1) Many viral infections are subclinical.

(2) The same disease may be produced by a variety of viruses.

(3) The same virus may produce a variety of diseases.

(4) The outcome in any particular case is determined by both viral and host factors and is

influenced by the genetics of each.

Viral virulence in intact animals should not be confused with cytopathogenicity for

cultured cells; viruses highly cytocidal in vitro may be harmless in vivo, and, conversely,

noncytocidal viruses may cause severe disease.

8

Table 30–1. Important Features of Acute Viral Diseases.

Local Infections

Systemic Infections

Specific disease example

Respiratory (rhinovirus) Measles

Site of pathology

Portal of entry

Distant site

Incubation period

Relatively short

Relatively long

Viremia

Absent

Present

Duration of immunity

Variable—may be short Usually lifelong

Role of secretory antibody (IgA) in resistance Usually important

Usually not important