مالحظت

:

قسم من الساليداث منقىلت نصا من

بعط الكتب المعتبرة في أمراض الجهاز

الهضمي والكبد

ACUTE UPPER GI-BLEEDING

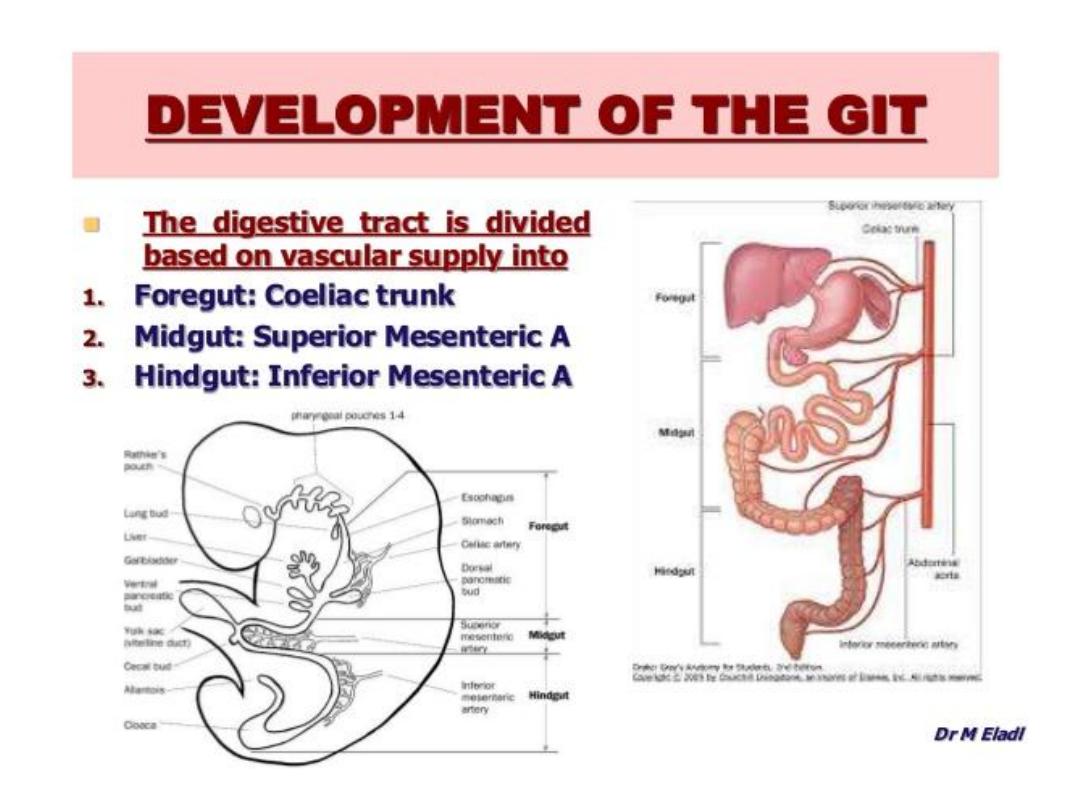

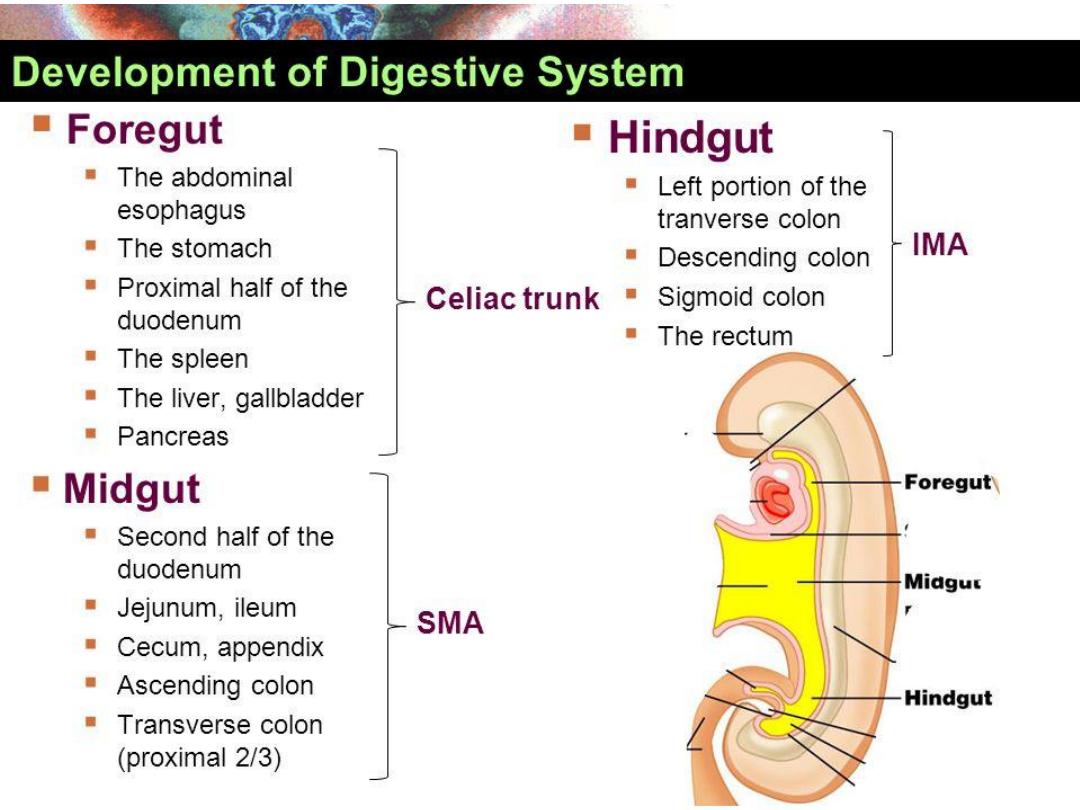

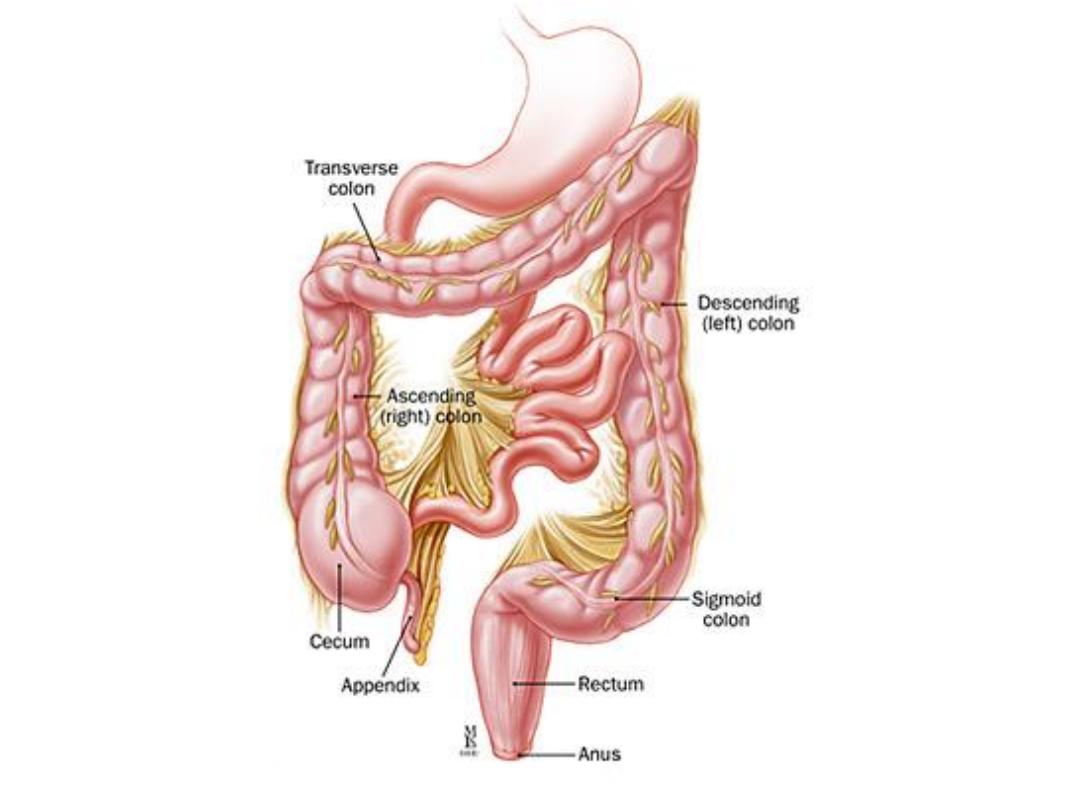

BOUNERIES FORE, MID AND HAND

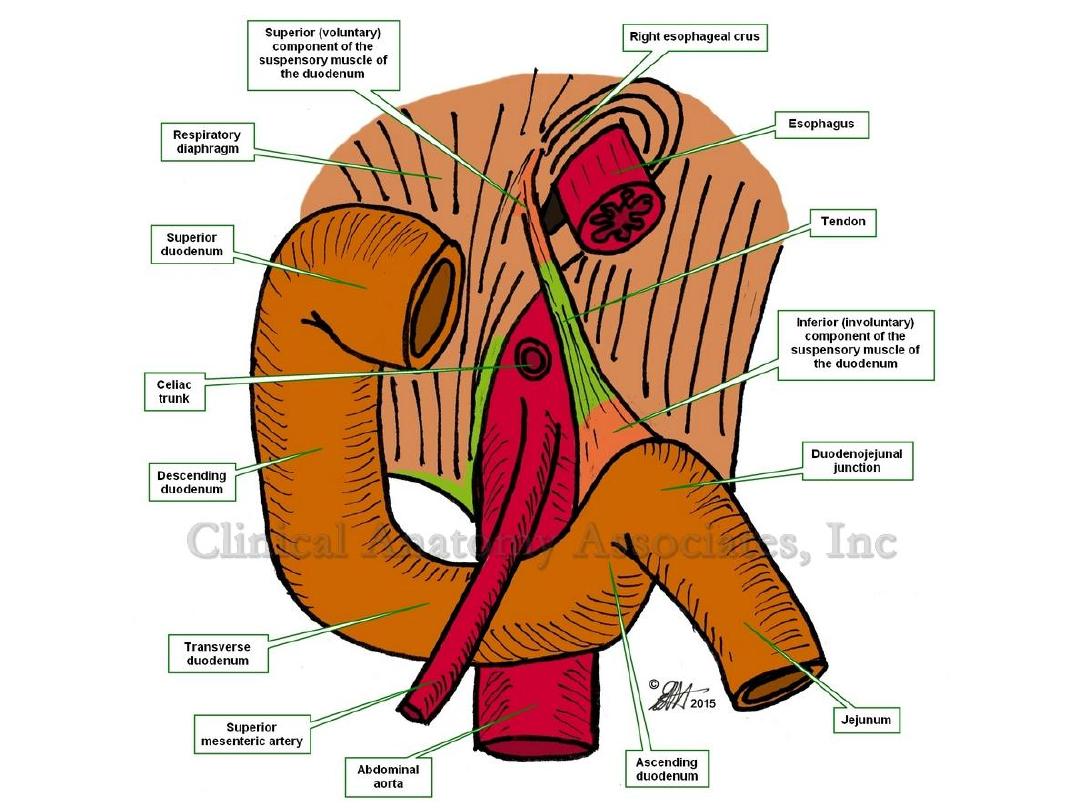

GUT BLOOD SUPPLY

Foregut:

Coeliac Trunk (T12).

Midgut:

Superior mesenteric artery ( at L1 level).

Hindgut:

Inferior mesenteric artery (L3)

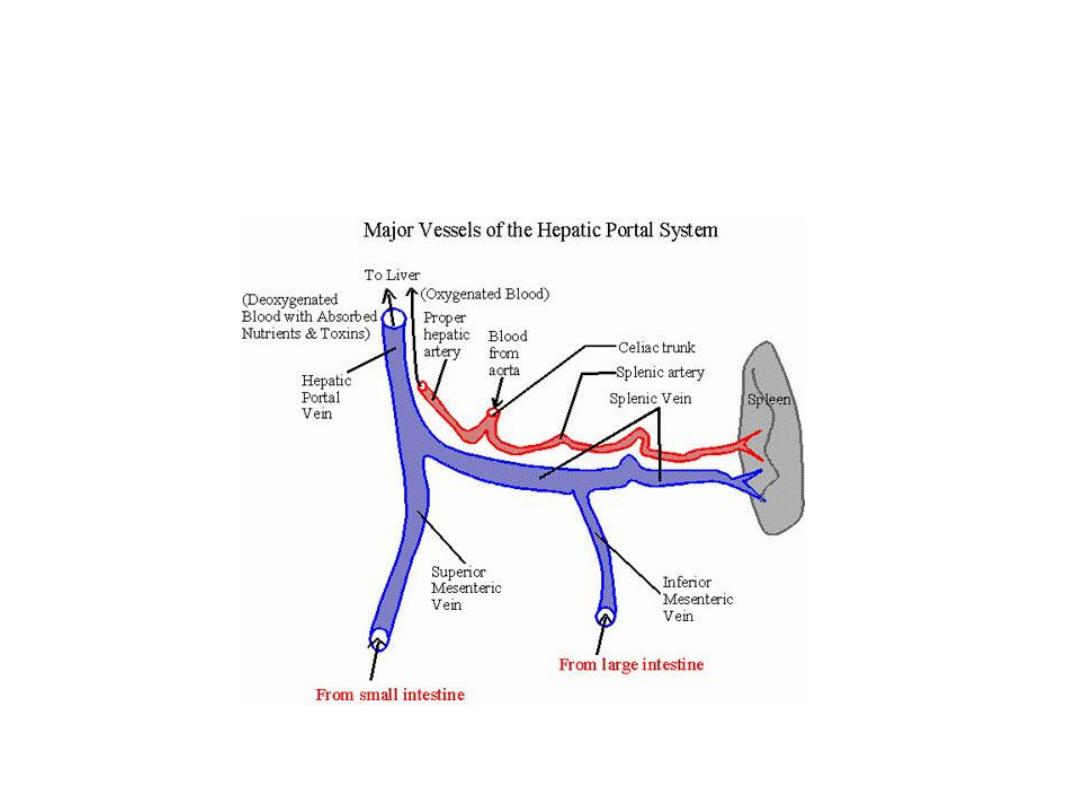

Portal vein anatomy

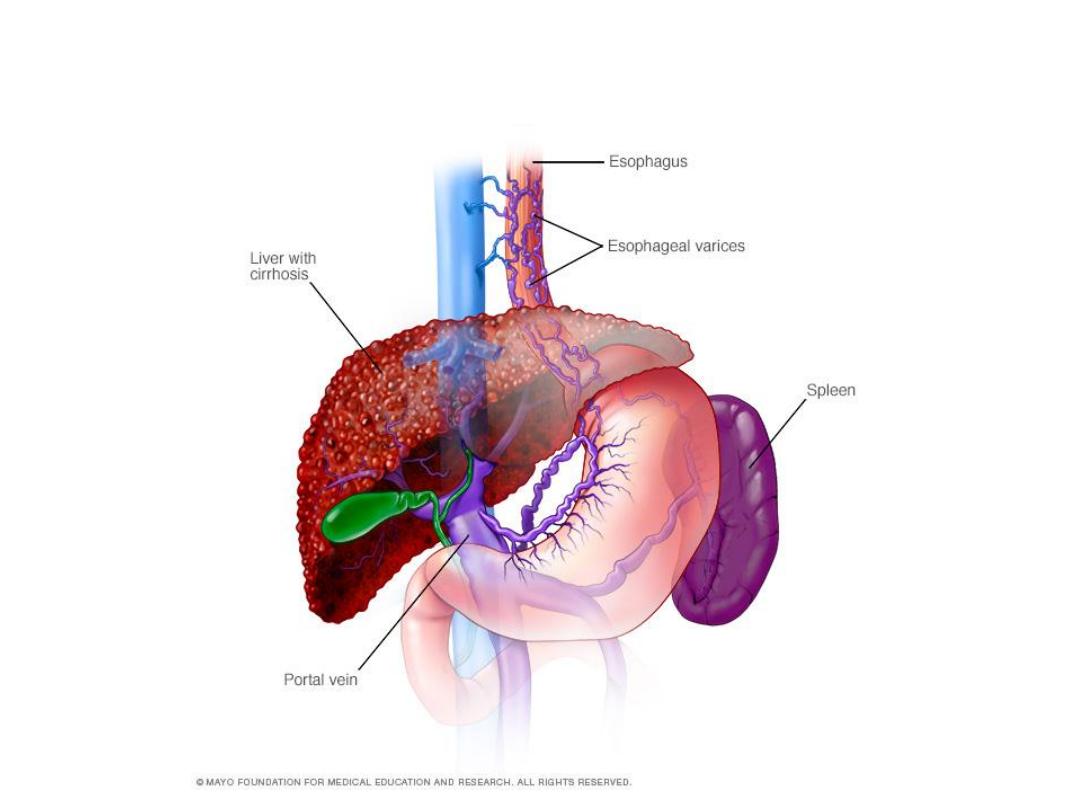

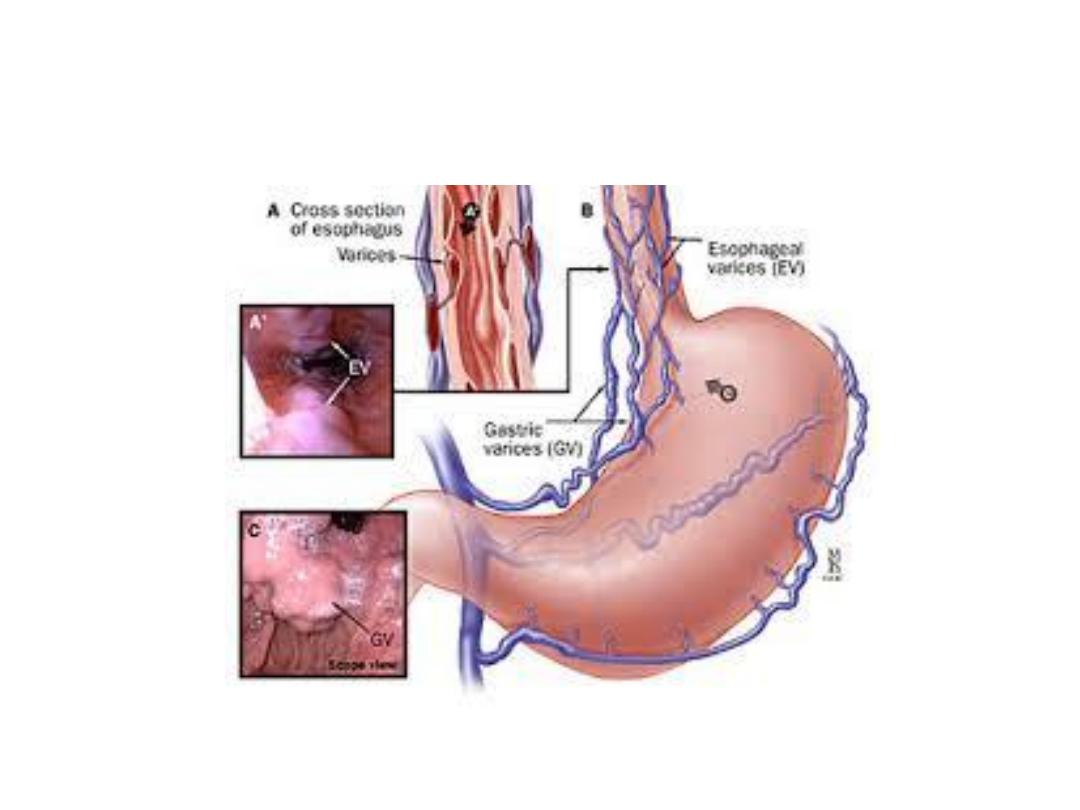

Varices formation

Mechanism of varices formation

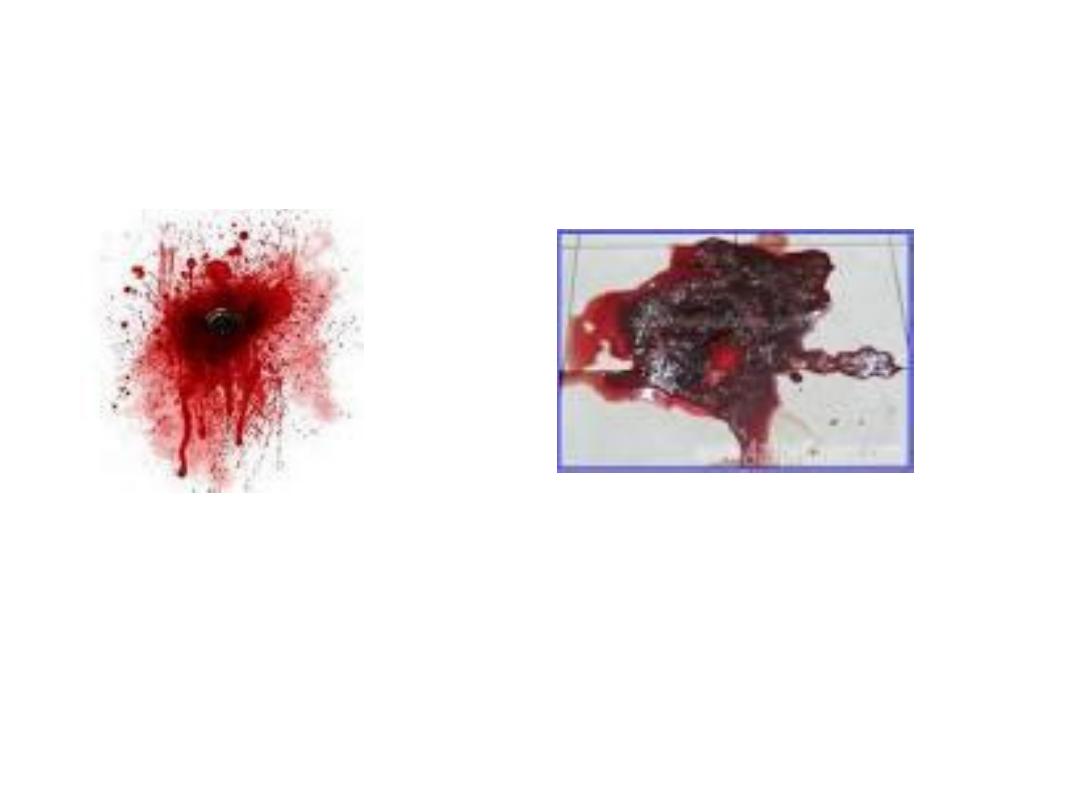

HEMATEMESIS

CAFFEE GROUND

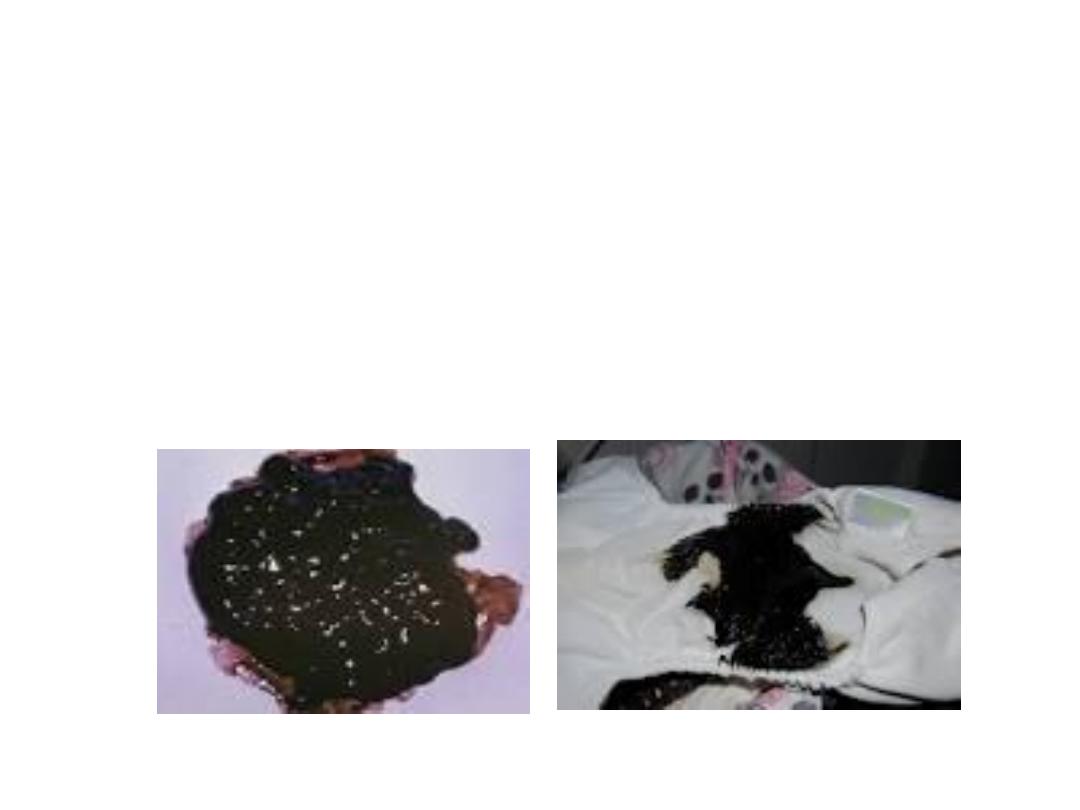

MELENA STOOL

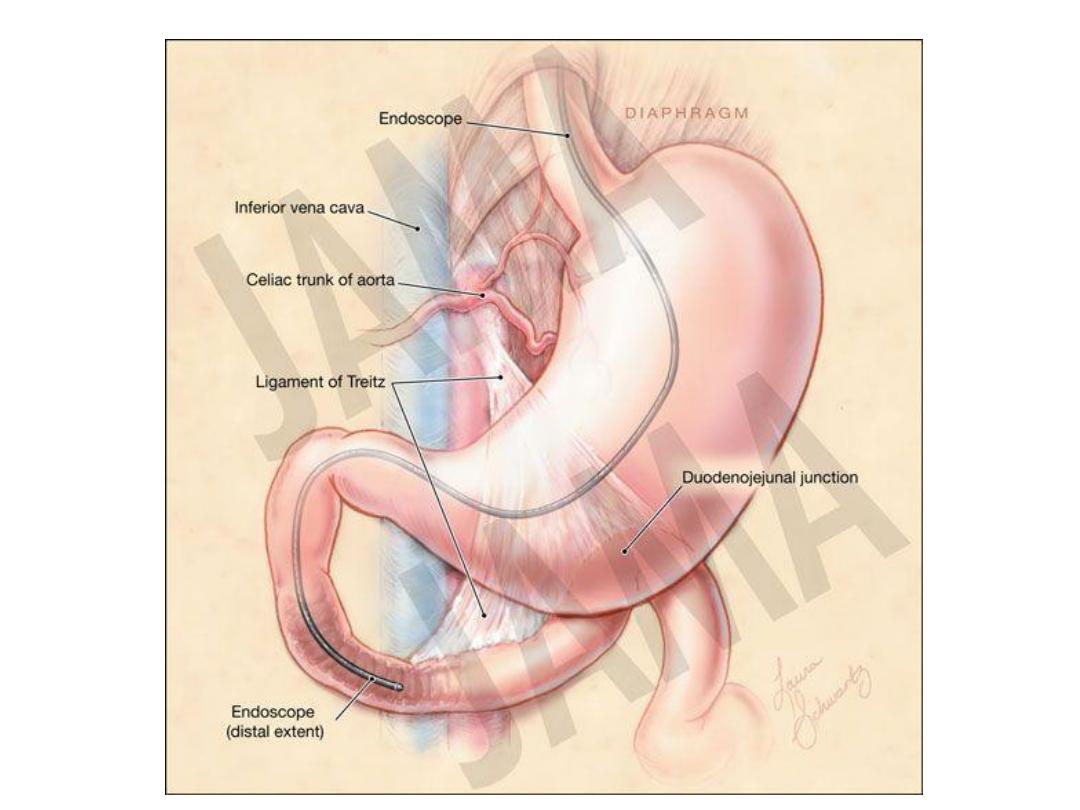

The majority of melena (black, tarry stool) originates

proximal to the ligament of Treitz (90 percent), though

it may also originate from the oropharynx, small bowel,

or right colon. Melena may be seen with variable

degrees of blood loss, being seen with as little as 50 mL

of blood

Hematochezia

Hematochezia (red or maroon blood in the

stool) is usually due to lower GI bleeding.

However, it can occur with massive upper GI

bleeding, which is typically associated with

orthostatic hypotension.

Factors that are predictive of a bleed coming from

an upper GI source included

A. A patient-reported history of melena

B. Melenic stool on examination

C. Blood or coffee grounds detected during nasogastric

lavage

D. A ratio of blood urea nitrogen to serum creatinine

greater than 30

On the other hand

, the

presence of blood clots in the

stool

made an upper GI source less likely

Factors

associated with severe bleeding included

1. red blood detected during nasogastric lavage.

2. Tachycardia, syncope, shock. presence of frankly

bloody emesis suggests moderate to severe

bleeding

3. or a hemoglobin level of less than 8 g/dL.

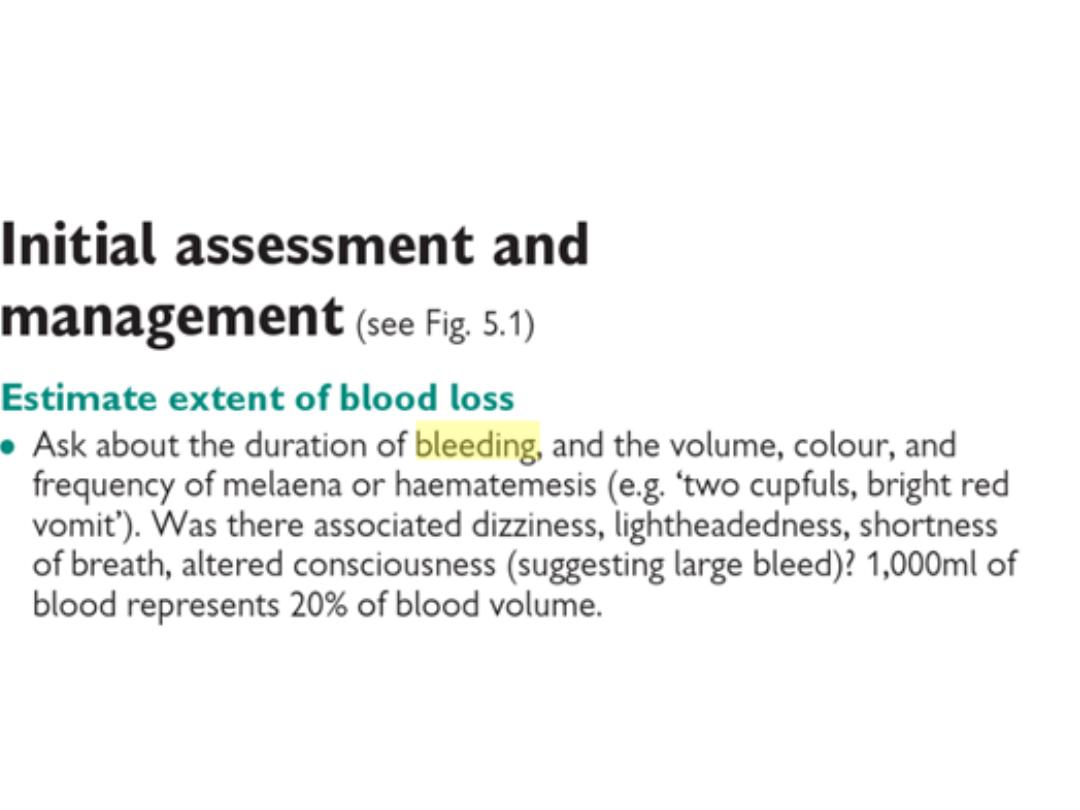

INITIAL EVALUATION

— The initial evaluation of a

patient with a suspected clinically significant acute

upper GI bleed includes a

history

,

physical

examination

,

laboratory tests

, and in some cases,

nasogastric lavage

. The goal of the evaluation is to

assess the severity of the bleed, identify potential

sources of the bleed, and determine if there are

conditions present that may affect subsequent

management. The information gathered as part of

the initial evaluation is used to guide decisions

regarding triage, resuscitation, empiric medical

therapy, and diagnostic testing.

Past medical history

— Patients should be asked about prior episodes of

upper GI bleeding, since up to 60 percent of patients with a history of an

upper GI bleed are bleeding from the same lesion . In addition, the patient's

past medical history should be reviewed to identify important comorbid

conditions that may lead to upper GI bleeding or may influence the patient's

subsequent management.

Potential bleeding sources suggested by a patient's past medical history

include:

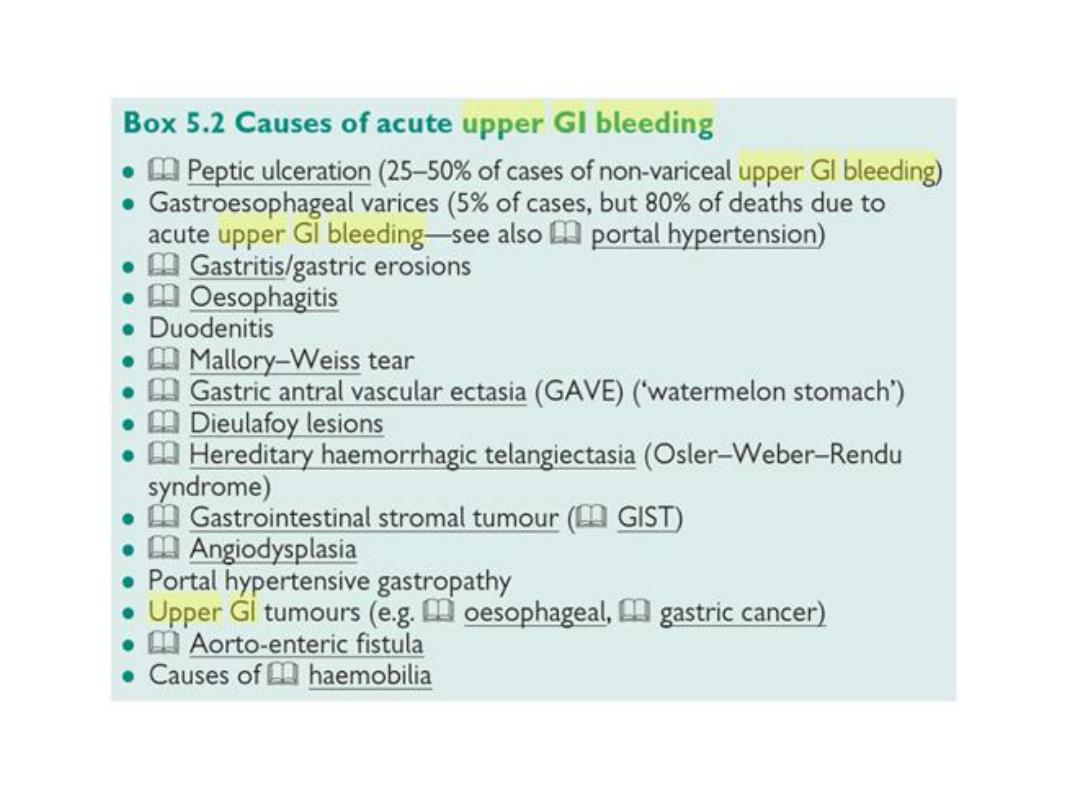

●Varices or portal hypertensive gastropathy in a patient with a history of liver

disease or alcohol abuse

●Aorto-enteric fistula in a patient with a history of an abdominal aortic

aneurysm or an aortic graft

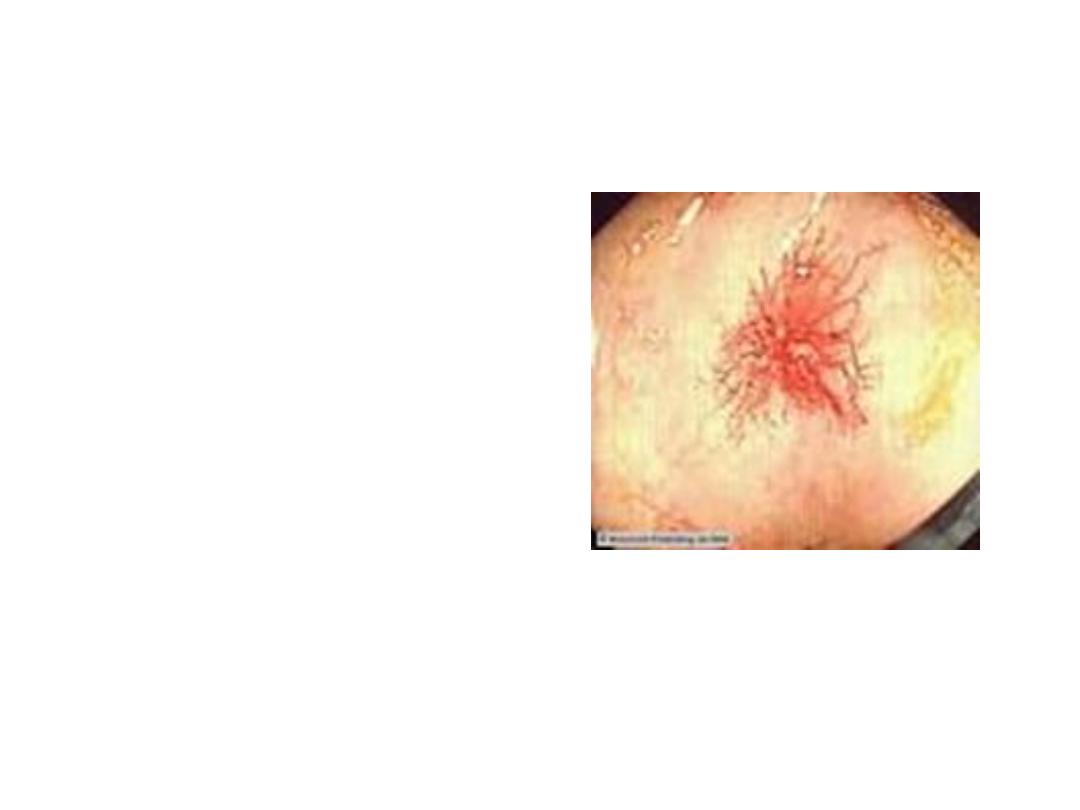

●Angiodysplasia in a patient with renal disease, aortic stenosis, or hereditary

hemorrhagic telangiectasia

●Peptic ulcer disease in a patient with a history of

Helicobacter pylori

,

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAIDs) use, or smoking

●Malignancy in a patient with a history of smoking, alcohol abuse, or

H.

pylori

infection

●Marginal ulcers (ulcers at an anastomotic site) in a patient with a

gastroenteric anastomosis

Medication history

— A thorough medication history

should be obtained, with particular attention paid to

drugs that:

●Predispose to peptic ulcer formation, such as

aspirin and other NSAIDs.

●Promote bleeding, such as antiplatelet agents (eg,

clopidogrel) and anticoagulants

●May alter the clinical presentation, such as bismuth

and iron, which can turn the stool black

.

Symptom assessment

— Patients should be asked about

symptoms as part of the assessment of the severity of the

bleed and as a part of the evaluation for potential bleeding

sources. Symptoms that suggest the bleeding is severe

include orthostatic dizziness, confusion, angina, severe

palpitations, and cold/clammy extremities.

Specific causes of upper GI bleeding may be suggested by

the patient's symptoms :

●Peptic ulcer: Epigastric or right upper quadrant pain

●Esophageal ulcer: Odynophagia, gastroesophageal reflux,

dysphagia

●Mallory-Weiss tear: Emesis, retching, or coughing prior to

hematemesis

●Variceal hemorrhage or portal hypertensive gastropathy:

Jaundice, weakness, fatigue, anorexia, abdominal distention

●Malignancy: Dysphagia, early satiety, involuntary weight

loss, cachexia

Physical examination

— The physical examination is

a key component of the assessment of hemodynamic

stability. Signs of hypovolemia include:

●

Mild to moderate hypovolemia

: Resting tachycardia.

●

Blood volume loss of at least 15 percent

: Orthostatic

hypotension (a decrease in the systolic blood pressure

of more than 20 mmHg and/or an increase in heart

rate of 20 beats per minute when moving from

recumbency to standing).

●

Blood volume loss of at least 40 percent:

Supine

hypotension.

Examination of the stool color may provide a clue to the

location of the bleeding, but it is not a reliable indicator.

In a series of 80 patients with severe hematochezia

(red or maroon blood in the stool), 74 percent had a

colonic lesion, 11 percent had an upper GI lesion, 9

percent had a presumed small bowel source, and no

site was identified in 6 percent . Nasogastric lavage

may be carried out if there is doubt as to whether a

bleed originates from the upper GI tract.

The presence of abdominal pain, especially if severe and

associated with rebound tenderness or involuntary

guarding, raises concern for perforation. If any signs of an

acute abdomen are present, further evaluation to exclude a

perforation is required prior to endoscopy.

Finally, as with the past medical history, the physical

examination should include a search for evidence of

significant comorbid illnesses

.

Laboratory data

— Laboratory tests that should be obtained

in patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding include a

complete blood count, serum chemistries, liver tests, and

coagulation studies. In addition, serial electrocardiograms and

cardiac enzymes may be indicated in patients who are at risk

for a myocardial infarction, such as older adults, patients with a

history of coronary artery disease, or patients with symptoms

such as chest pain or dyspnea

.

The initial hemoglobin in patients with acute upper GI bleeding

will often be at the patient's baseline because the patient is

losing whole blood. With time (typically after 24 hours or more)

the hemoglobin will decline as the blood is diluted by the influx

of extravascular fluid into the vascular space and by fluid

administered during resuscitation. It should be kept in mind that

overhydration can lead to a falsely low hemoglobin value. The

initial hemoglobin level is monitored every two to eight hours,

depending upon the severity of the bleed.

Patients with acute bleeding should have

normocytic

red blood cells

. Microcytic red blood cells or iron

deficiency anemia suggest chronic bleeding. Because

blood is absorbed as it passes through the small bowel

and patients may have decreased renal perfusion,

patients with acute upper GI bleeding typically have an

elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN)-to-creatinine or

urea-to-creatinine ratio (>20:1 or >100:1, respectively)

[The higher the ratio, the more likely the bleeding is

from an upper GI source

Nasogastric lavage

— Whether all patients with suspected

acute upper GI bleeding require nasogastric tube (NGT)

placement is controversial, in part because studies have failed

to demonstrate a benefit with regard to clinical outcomes

More often, NGT lavage is used when it is unclear if a patient

has ongoing bleeding and thus might benefit from an early

endoscopy. In addition, nasogastric tube lavage can be used to

remove particulate matter, fresh blood, and clots from the

stomach to facilitate endoscopy.

he presence of red blood or coffee ground material in the

aspirate also confirms an upper GI source of bleeding and

predicts whether the bleeding is caused by a lesion at increased

risk for ongoing or recurrent bleeding However, lavage may not

be positive if bleeding has ceased or arises beyond a closed

pylorus. The presence of nonbloody bilious fluid suggests that

the pylorus is open and that there is no active upper GI bleeding

distal to the pylorus.

We suggest that patients only undergo NGT lavage

if particulate matter, fresh blood, or clots need to be

removed from the stomach to facilitate endoscopy

.

All patients with hemodynamic instability (shock, orthostatic

hypotension) or active bleeding (manifested by

hematemesis, bright red blood per nasogastric tube, or

hematochezia) should be admitted to an intensive care unit

for resuscitation and close observation with automated

blood pressure monitoring, electrocardiogram monitoring,

and pulse oximetry.

A table outlining the emergency management of acute

severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding is provided.

Other patients can be admitted to a regular medical ward,

though we suggest that all admitted patients with the

exception of low-risk patients receive electrocardiogram

monitoring. Outpatient management may be appropriate for

some low-risk patients.

General support

— Patients should receive

supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula and should

receive nothing per mouth. Two large caliber (16 gauge

or larger) peripheral intravenous catheters or a central

venous line should be inserted and placement of a

pulmonary artery catheter should be considered in

patients with hemodynamic instability or who need close

monitoring during resuscitation

.

Elective endotracheal intubation in patients with ongoing

hematemesis or altered respiratory or mental status may

facilitate endoscopy and decrease the risk of aspiration.

Fluid resuscitation

— Adequate resuscitation and

stabilization is essential prior to endoscopy to minimize

treatment-associated complications. Patients with active

bleeding should receive intravenous fluids (eg, 500 mL of

normal saline or lactated Ringer's solution over 30 minutes)

while being typed and cross-matched for blood transfusion.

Patients at risk of fluid overload may require intensive

monitoring with a pulmonary artery catheter.

If the blood pressure fails to respond to initial resuscitation

efforts, the rate of fluid administration should be increased.

Blood transfusions

— The decision to initiate blood transfusions

must be individualized.

The approach is to initiate blood

transfusions if the hemoglobin is <7 g/dL (70 g/L) for most

patients (including those with stable coronary artery

disease), with a goal of maintaining the hemoglobin at a level

≥7 g/dL (70 g/L).

However, our goal is to maintain the

hemoglobin at a level of ≥9 g/dL (90 g/L) for patients at increased

risk of suffering adverse events in the setting of significant

anemia, such as those with unstable coronary artery disease. We

do not have an age cutoff for determining which patients should

have a goal hemoglobin of ≥9 g/dL (90 g/L), and instead base the

decision on the patient's comorbid conditions. However, patients

with active bleeding and hypovolemia may require blood

transfusion despite an apparently normal hemoglobin.

It is particularly important to avoid overtransfusion in patients

with suspected variceal bleeding, as it can precipitate worsening

of the bleeding. Transfusing patients with suspected variceal

bleeding to a hemoglobin >10 g/dL (100 g/L) should be avoided.

A randomized trial suggests that using a lower hemoglobin

threshold for initiating transfusion improves outcomes. In the

trial, 921 adults with acute upper GI bleeding were assigned to

either a restrictive transfusion strategy (transfusion only when

the hemoglobin fell to <7 g/dL [70 g/L]) or a liberal transfusion

strategy (transfusion when the hemoglobin fell to <9 g/dL

Patients with active bleeding and a low platelet

count (<50,000/microL) should be transfused with platelets.

Patients with a coagulopathy that is not due to cirrhosis

(prolonged prothrombin time with INR >1.5) should be transfused

with fresh frozen plasma (FFP)

.

Acid suppression

— Patients admitted to the hospital with

acute upper GI bleeding are typically treated with a proton

pump inhibitor (PPI). Some opinions suggest that patients

with acute upper GI bleeding be started empirically on an

intravenous (IV) PPI (eg,omeprazole 40 mg IV twice daily

but not H2 blockers). It can be started at presentation and

continued until confirmation of the cause of bleeding

.

But other opinions regard the use of PPI only if nonvariceal bleeding is

confirmed endoscopically.

So both opinions are correct

PPIs may also promote hemostasis in patients with

lesions other than ulcers. This likely occurs because

neutralization of gastric acid leads to the stabilization of

blood clots

Prokinetics

—

Both

have been

studied in patients with acute upper GI bleeding. The

goal of using a prokinetic agent is to improve gastric

visualization at the time of endoscopy by clearing the

stomach of blood, clots, and food residue. We suggest

that erythromycin be considered in patients who are

likely to have a large amount of blood in their stomach,

such as those with severe bleeding. A reasonable dose is

3 mg/kg intravenously over 20 to 30 minutes, 30 to 90

minutes prior to endoscopy

.

Somatostatin and its analogs

— Somatostatin, or its

analog octreotide, is used in the treatment of variceal

bleeding and may also reduce the risk of bleeding due to

nonvariceal causes . In patients with suspected variceal

bleeding, octreotide is given as an intravenous bolus of

20 to 50 mcg, followed by a continuous infusion at a rate

of 25 to 50 mcg per hour.

Octreotide is not recommended for routine use in

patients with acute nonvariceal upper GI bleeding, but it

can be used as adjunctive therapy in some cases. Its

role is generally limited to settings in which endoscopy

is unavailable or as a means to help stabilize patients

before definitive therapy can be performed

.

Antibiotics for patients with cirrhosis

— Bacterial

infections are present in up to 20 percent of patients with

cirrhosis who are hospitalized with gastrointestinal bleeding;

up to an additional 50 percent develop an infection while

hospitalized. Such patients have increased mortality.

Multiple trials evaluating the effectiveness of prophylactic

antibiotics in cirrhotic patients hospitalized for bleeding

suggest an overall reduction in infectious complications and

possibly decreased mortality. Antibiotics may also reduce the

risk of recurrent bleeding in hospitalized patients who bled

A reasonable conclusion from these

.

varices

from esophageal

data is that patients with cirrhosis who present with acute

or other causes) should be

varices

upper GI bleeding (from

given prophylactic antibiotics, preferably before endoscopy

There is no role for tranexamic acid in the treatment of upper

GI bleeding

, since the current standard of care is to treat

patients with proton pump inhibitors and endoscopic therapy

(if indicated).

Anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents

— When

possible, anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents

should be held in patients with upper GI bleeding.

However, the thrombotic risk of reversing

anticoagulation should be weighed against the risk of

continued bleeding without revers

As a general rule, we obtain surgical and interventional

radiology consultation if endoscopic therapy is unlikely to be

successful, if the patient is deemed to be at high risk for

rebleeding or complications associated with endoscopy, or if

there is concern that the patient may have an aorto-enteric

fistula. In addition, a surgeon and an interventional radiologist

should be promptly notified of all patients with severe acute

upper GI bleeding

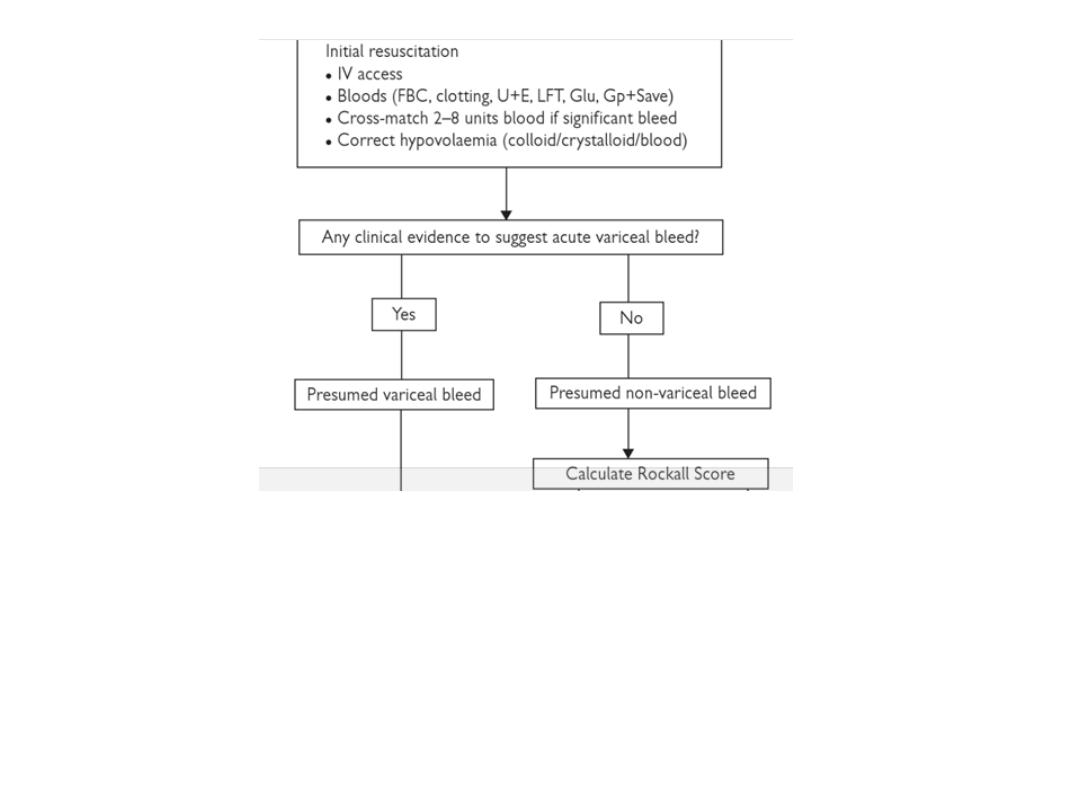

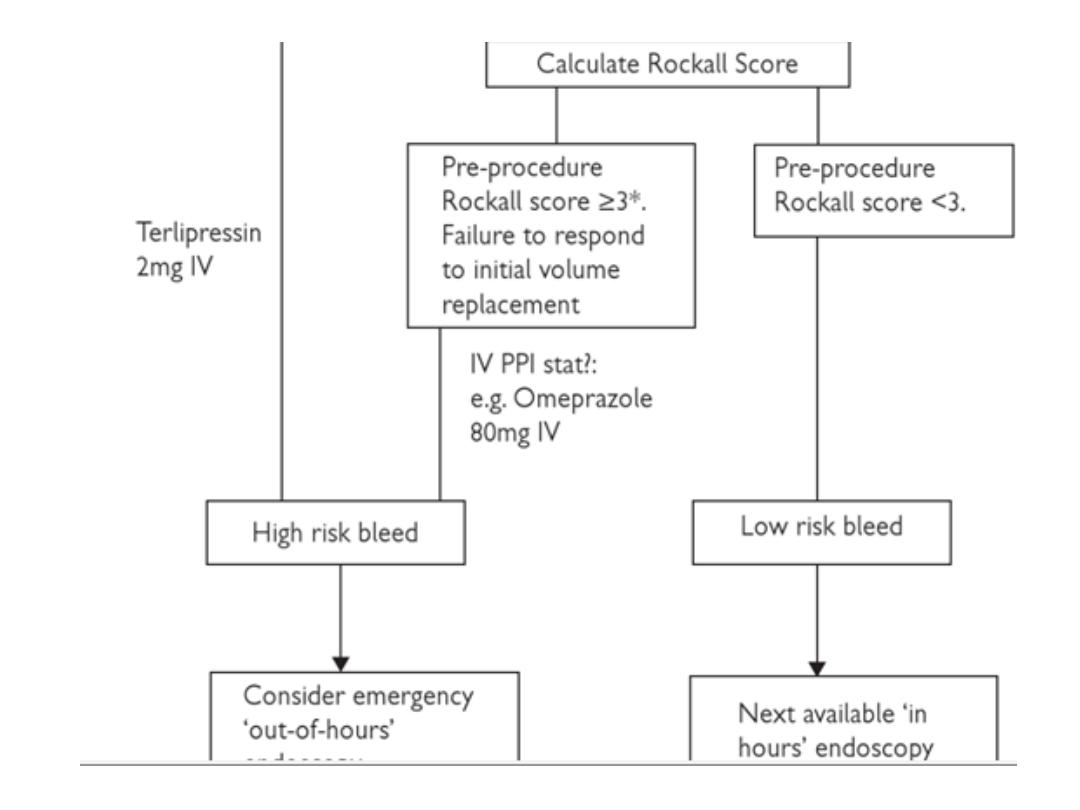

SUMMARY OF INITIAL APPROACH

TO A PATIENT WITH AUGIB

in the next 2 slides

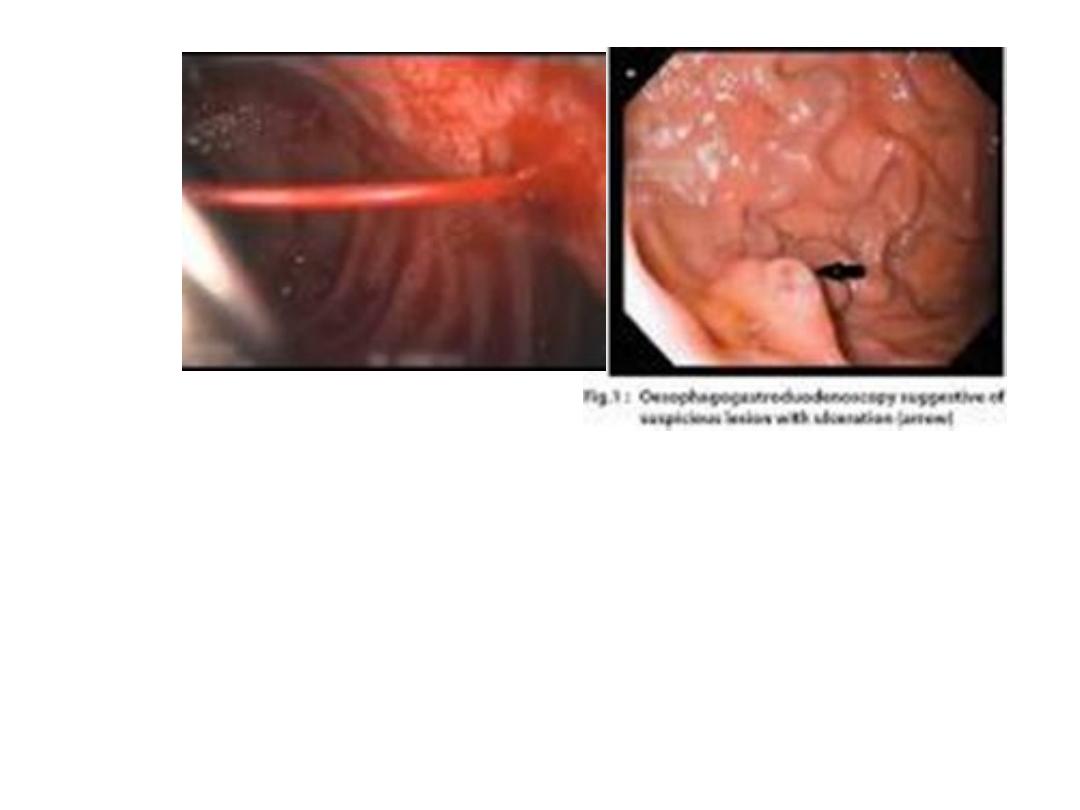

Upper endoscopy

— Upper endoscopy is the diagnostic

modality of choice for acute upper GI bleeding. Endoscopy has

a high sensitivity and specificity for locating and identifying

bleeding lesions in the upper GI tract. In addition, once a

bleeding lesion has been identified, therapeutic endoscopy can

achieve acute hemostasis and prevent recurrent bleeding in

most patients. Early endoscopy (within 24 hours) is

recommended for most patients with acute upper GI bleeding,

though whether early endoscopy affects outcomes and

resource utilization is unsettled.

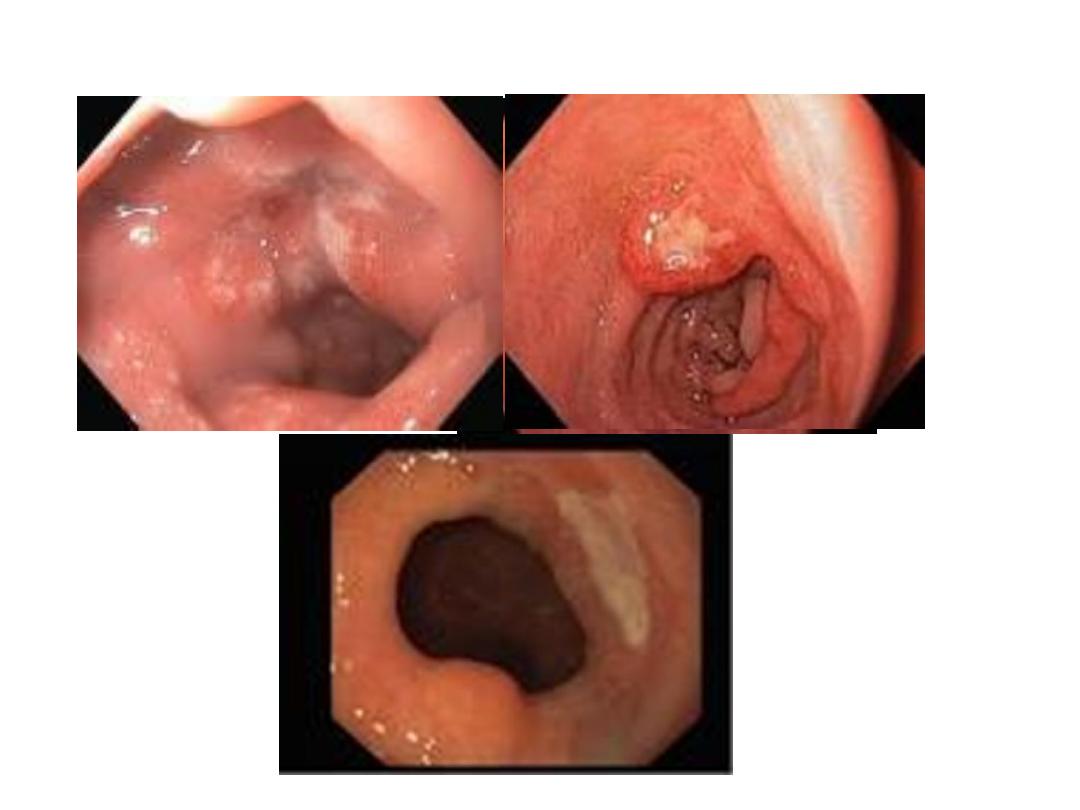

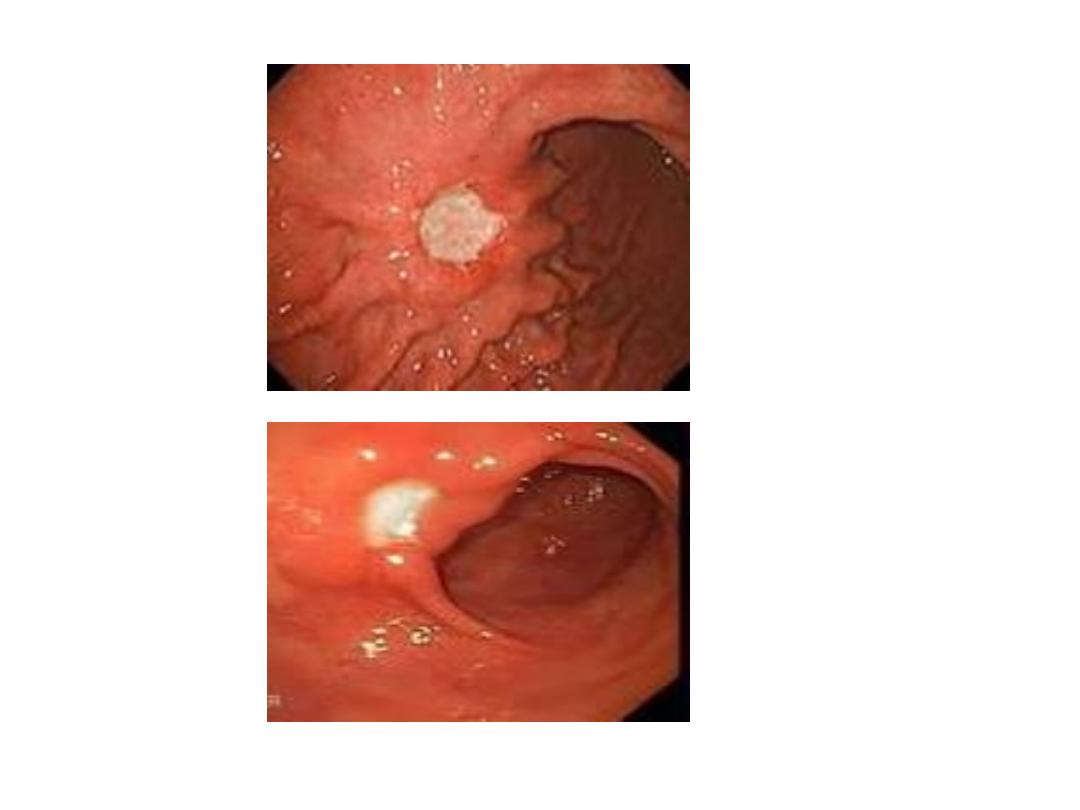

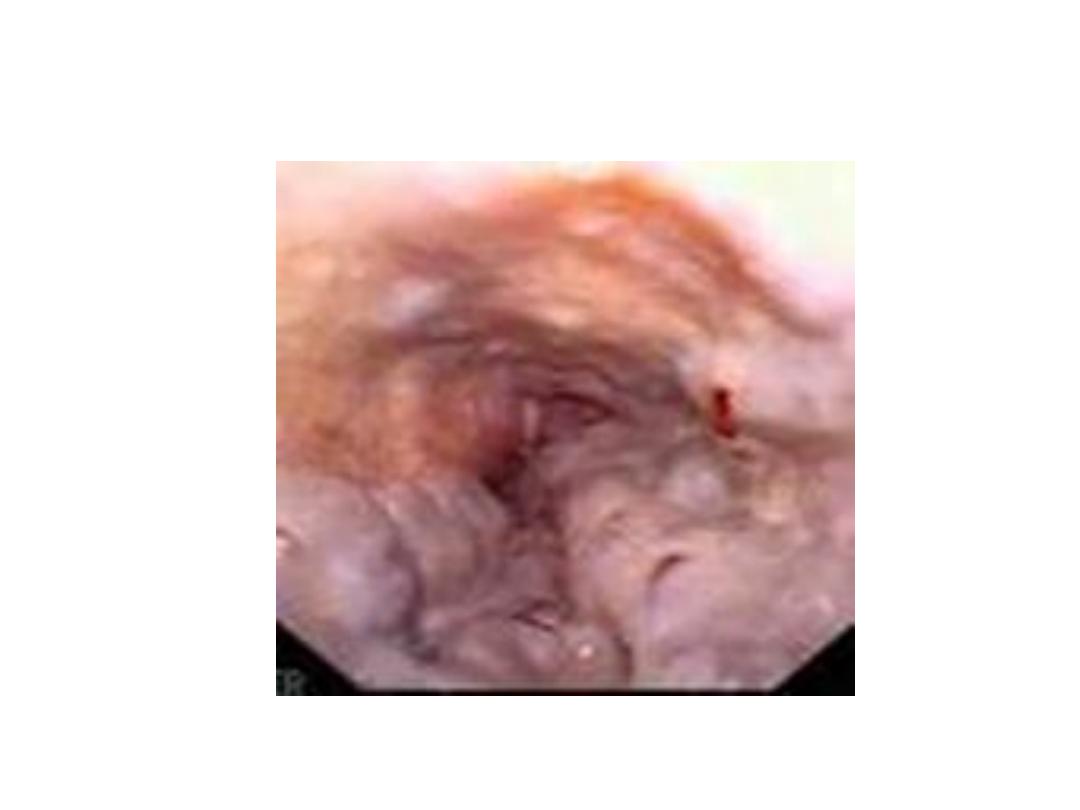

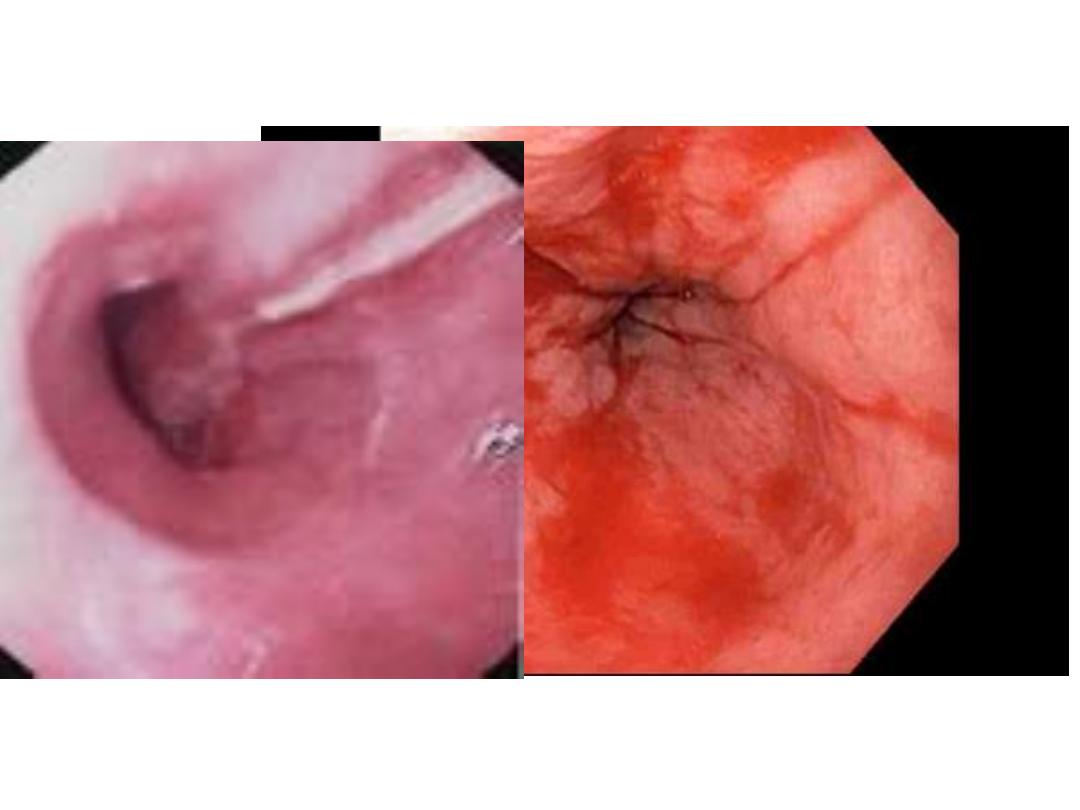

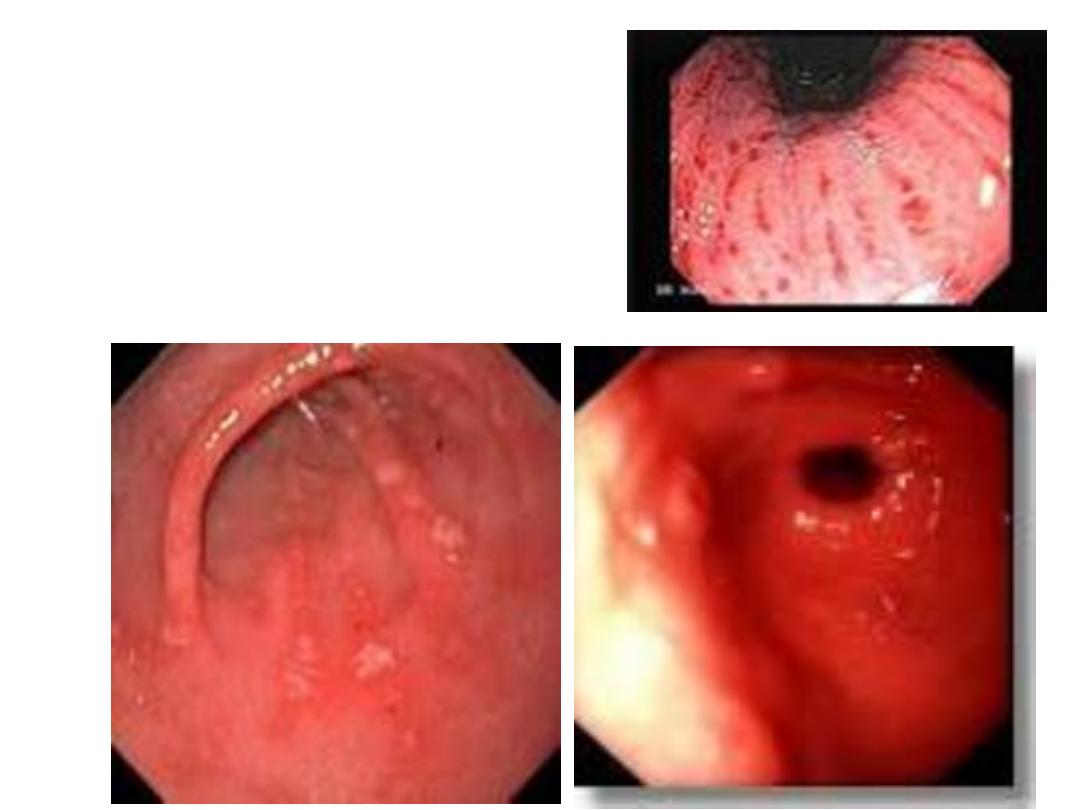

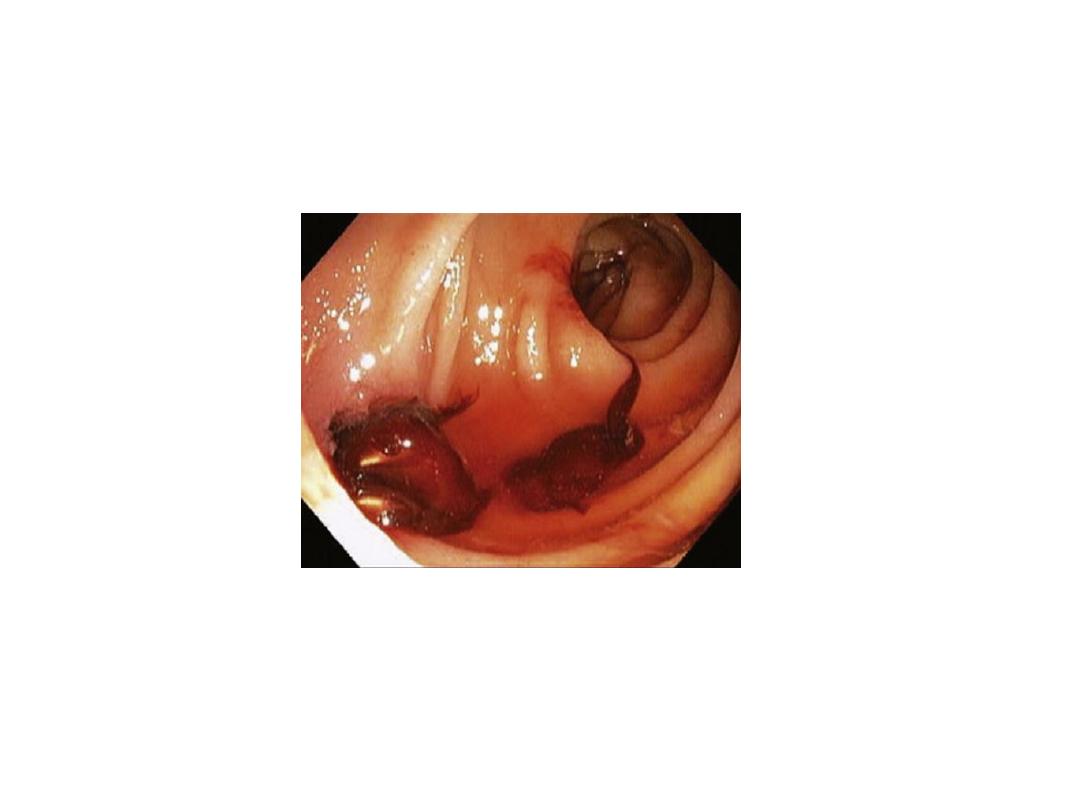

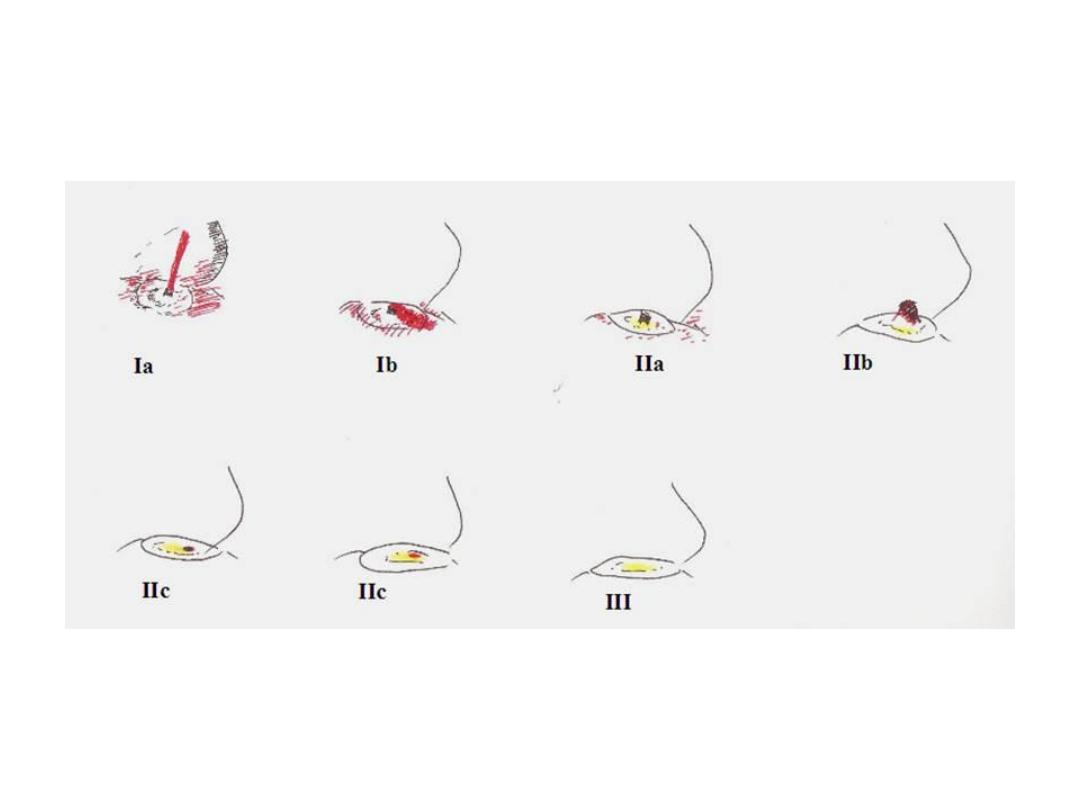

Endoscopic findings in patients with peptic ulcers may be

described using the Forrest classification . Findings include

spurting hemorrhage (class Ia) , oozing hemorrhage (class

Ib), a nonbleeding visible vessel (class IIa) , an adherent clot

(class IIb) , a flat pigmented spot (class IIc), and a clean ulcer

base (class III). The endoscopic appearance helps determine

which lesions require endoscopic therapy

Endoscopy

Offer endoscopy to

unstable

patients with severe acute

upper gastrointestinal bleeding immediately after

resuscitation.

Offer endoscopy within 24 hours of

admission to all other patients with upper

gastrointestinal bleeding

.

Types of lesion

Description

Rebleeding rate

Type I: Active bleeding

Ia

Spurting artery

55-100%

Ib

Oozing

Type II: Recent bleed

IIa

Non bleeding vessel

40-50%

IIb

Adherent clot

20-30%

IIc

Haemetinic spots (red or black spot)

10%

Type III: Lesions without bleeding

III

Clean base

<5%

FORREST CLASSIFICATION

مهم

Risks of endoscopy

— Risks of upper endoscopy include

aspiration, adverse reactions to conscious sedation,

perforation, and increasing bleeding while attempting

therapeutic intervention. Patients need to be hemodynamically

stable prior to undergoing endoscopy

.

Other diagnostic tests

— Other diagnostic tests for acute

upper GI bleeding include angiography, which can detect active

bleeding, deep small bowel enteroscopy, and rarely,

intraoperative enteroscopy .

Upper GI barium studies

are contraindicated in the setting of acute upper GI bleeding

because they will interfere with subsequent endoscopy

,

angiography, or surgery. There is also interest in using wireless

capsule endoscopy for patients who have presented to the

emergency department with suspected upper GI bleeding. An

esophageal capsule (which has a recording time of 20 minutes)

can be given in the emergency department and reviewed

immediately for evidence of bleeding

.

مهم جدا

Factors associated with rebleeding identified in a meta-

analysis included:

●Hemodynamic instability (systolic blood pressure less than

100 mmHg, heart rate greater than 100 beats per minute)

●Hemoglobin less than 10 g/L

●Active bleeding at the time of endoscopy

●Large ulcer size (greater than 1 to 3 cm in various studies)

●Ulcer location (posterior duodenal bulb or high lesser gastric

curvature).

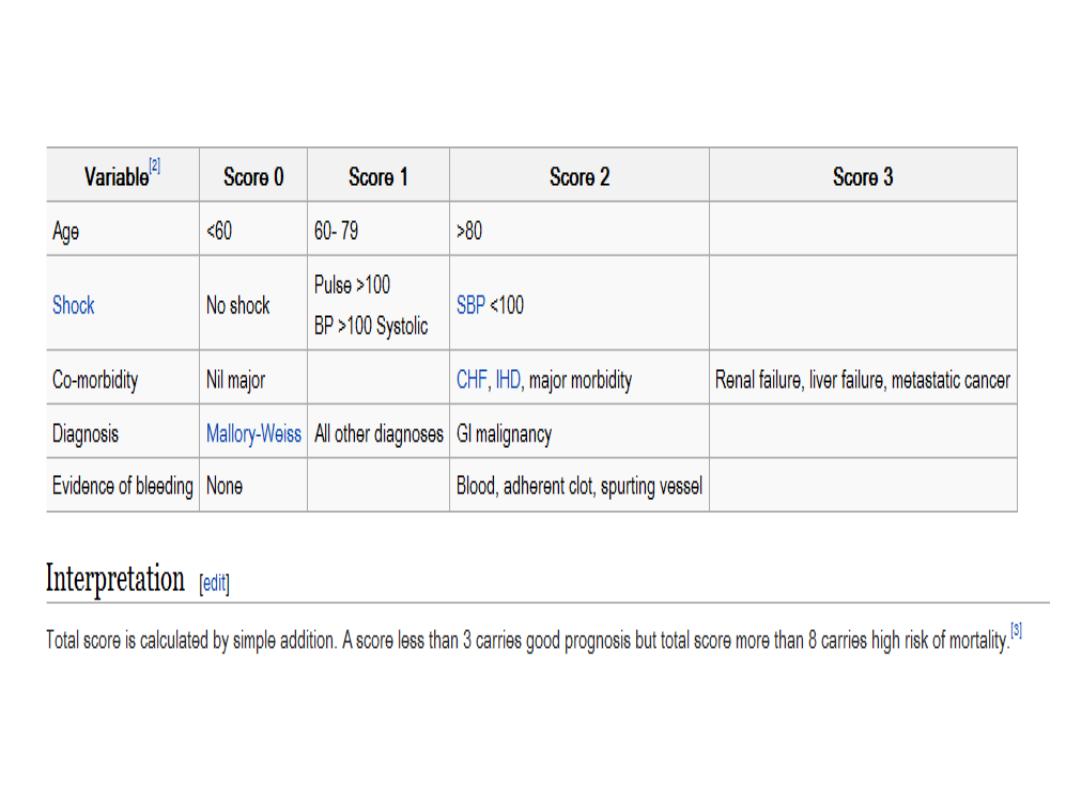

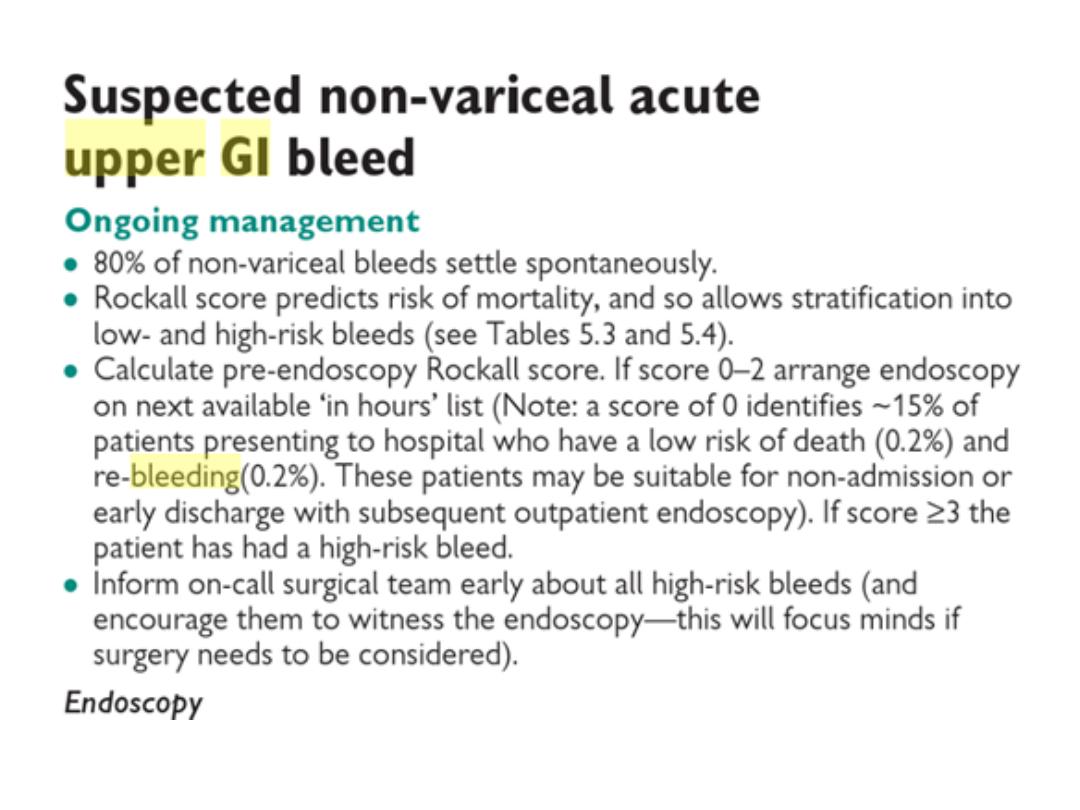

Risk scores

Many

risk factors

are known to influence the

outcome in UGIB setting.

Age.

Comorbidities.

Presence of shock.

Endoscopic diagnosis.

Haemoglobin values at the time.

Ulcers’ size.

Stigmata of recent haemorrhage.

And need for a blood transfusion have all been

described as significant risk factors for

rebleeding and death

In order to stratify the risk of complications, rebleeding,

need of clinical intervention or death, several clinical

scores are in use.

The two most important scoring system for such

assessment are :

The Glasgow Blatchford score:

(Urea, Hb, SBP,

others): is a screening tool to assess the likelihood

that a patient with an acute upper gastrointestinal

bleeding (UGIB) will need to have medical

intervention such as a blood transfusion or

endoscopic intervention.

The full Rockall score:

incorporates clinical and

endoscopic variables, has been validated to predict

mortality.Consider early discharge for patients with a

pre-endoscopy Blatchford score of 0

.

Diagrammatic representation of the

various type of Forrest lesions

Managing non-variceal bleeding

Endoscopic treatment

Do not use adrenaline as monotherapy for the

endoscopic treatment of non-variceal upper

gastrointestinal bleeding.

For the endoscopic treatment of non-variceal

upper gastrointestinal bleeding, use one of the

following:

1. a mechanical method (for example, clips) with

or without adrenaline

2. thermal coagulation with adrenaline

3. fibrin or thrombin with adrenaline.

Proton pump inhibitors

Do not offer acid-suppression drugs (proton

pump inhibitors or H2-receptor antagonists)

before endoscopy

to patients with suspected

non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Offer proton pump inhibitors to patients with

non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding and

stigmata of recent haemorrhage shown at

endoscopy

.

Managing variceal bleeding مهم

Offer

terlipressin

to patients with suspected variceal

bleeding at presentation. Stop treatment

after definitive haemostasis has been achieved, or after 5

days, unless there is another indication for its use.

Offer

prophylactic antibiotic therapy

at presentation to

patients with suspected or confirmed variceal bleeding.

Gastric varices

1. Endoscopic injection of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate to

patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding from gastric

varices.

2. TIPS if bleeding from gastric varices is not controlled by

endoscopic injection of Nbutyl-

2-cyanoacrylate

.

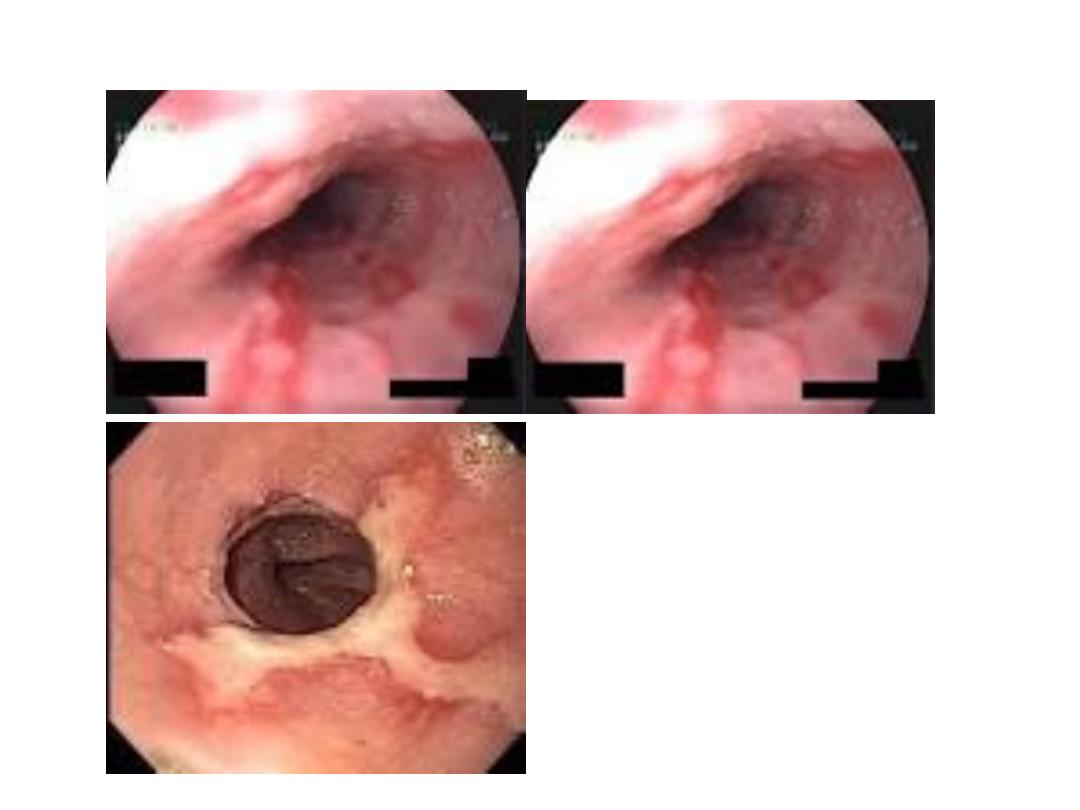

Oesophageal varices(NICE GUIDELINE)

1. band ligation in patients with upper gastrointestinal

bleeding from oesophageal varices.

2. Consider transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic

shunts (TIPS) if bleeding from oesophageal varices is not

controlled by band ligation

.

Other criteria used for predicating risk of upper

gastrointestinal bleeding and mortality are the

Rockall score

(utilises clinical and endoscopic

criteria) and

Glasgow Blatchford

(utilises clinical

and laboratory parameters) score. The Rockall

Score is particular useful for predicting mortality

whereas the Glasgow Blatchford score is good for

predicting early discharge or requiring for hospital

admission.