Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

1

The Enterobacteriaceae are a large, heterogeneous group of gram-

negative rods whose natural habitat is the intestinal tract of humans

and animals. The family includes many genera (Escherichia, Shigella,

Salmonella, Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Serratia, Proteus, and others).

Some enteric organisms, eg, Escherichia coli, are part of the normal

flora and incidentally cause disease, while others, the salmonellae and

shigellae, are regularly pathogenic for humans.

The Enterobacteriaceae are facultative anaerobes or aerobes, ferment

a wide range of carbohydrates, possess a complex antigenic structure,

and produce a variety of toxins and other virulence factors.

The family Enterobacteriaceae have the following characteristics:

They are gram-negative rods, either motile with peritrichous flagella

(Bacilli with many flagella all over their surface) or nonmotile.

They grow on peptone (water-soluble protein derivatives) or meat

extract media without the addition of sodium chloride or other

supplements; grow well on MacConkey agar (MacConkey agar is

a culture medium designed to grow Gram-negative bacteria and

differentiate them for lactose fermentation); grow aerobically and

anaerobically (are facultative anaerobes); ferment rather than oxidize

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

2

glucose, often with gas production; are catalase-positive, oxidase-

negative, and reduce nitrate to nitrite; and have a 39–59% G + C DNA

content. Examples of biochemical tests used to differentiate the

species of Enterobacteriaceae are presented in Table 15–1.

The major groups of Enterobacteriaceae are described in here, while

specific characteristics of salmonellae, shigellae, are discussed

separately in another lecture.

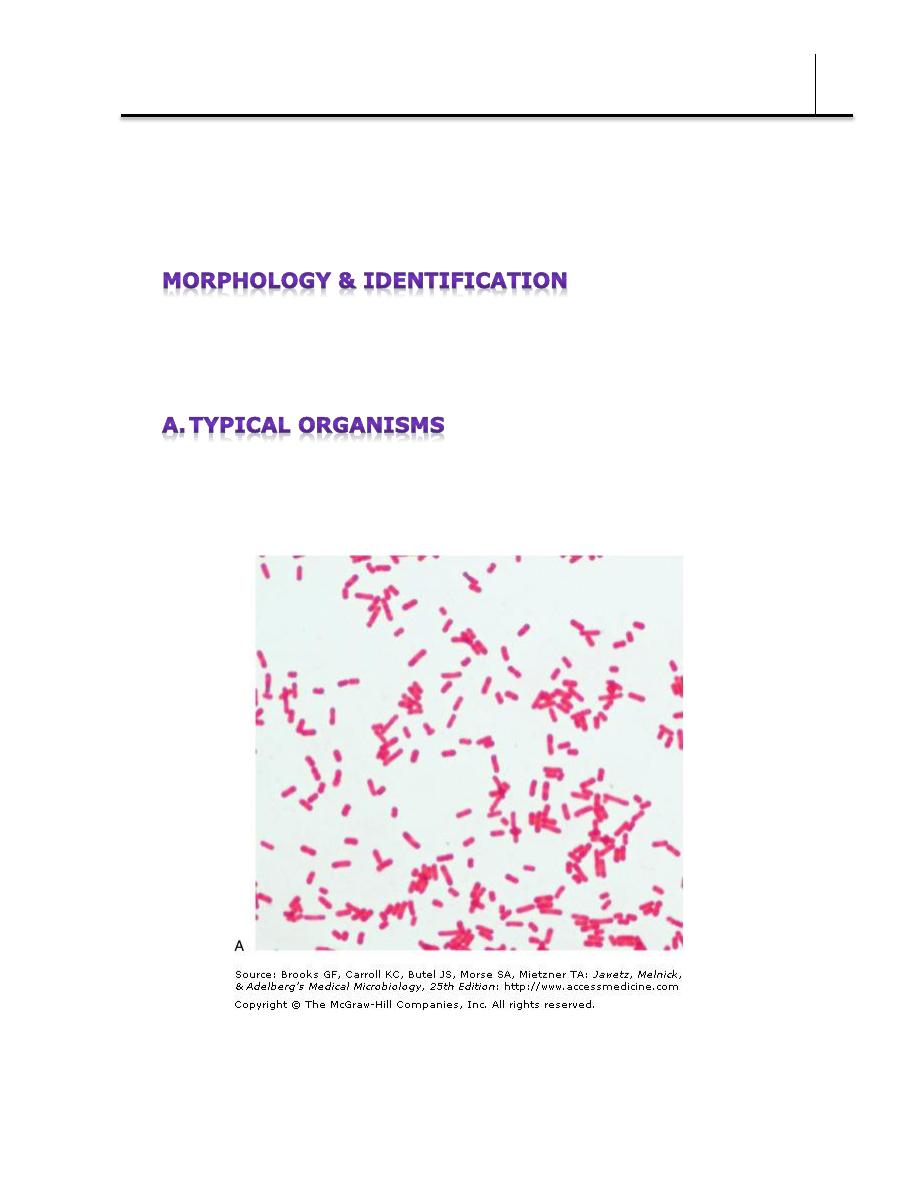

The Enterobacteriaceae are short gram-negative rods. Capsules are

large and regular in Klebsiella, less so in Enterobacter, and uncommon

in the other species.

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

3

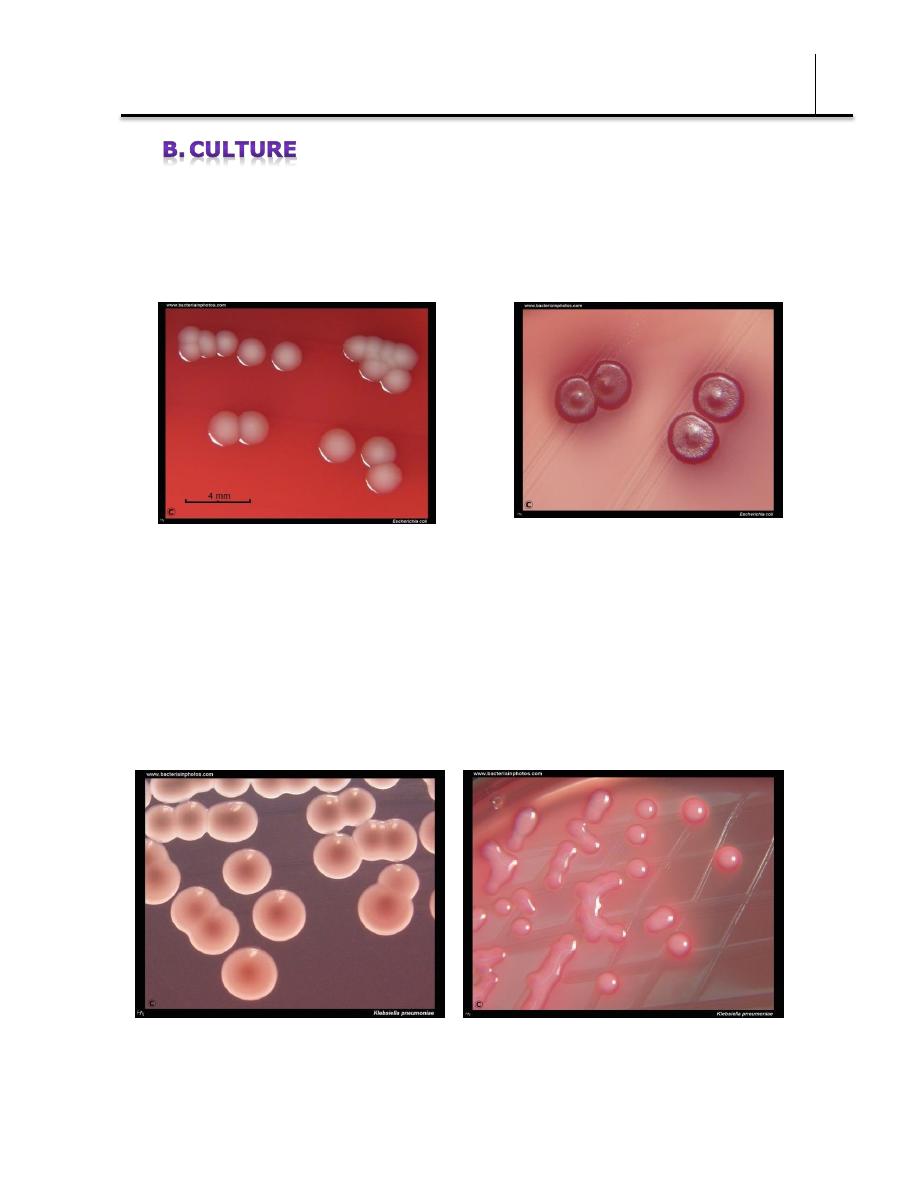

E coli and most of the other enteric bacteria form circular, convex,

smooth colonies with distinct edges. Some strains of E coli produce

hemolysis on blood agar.

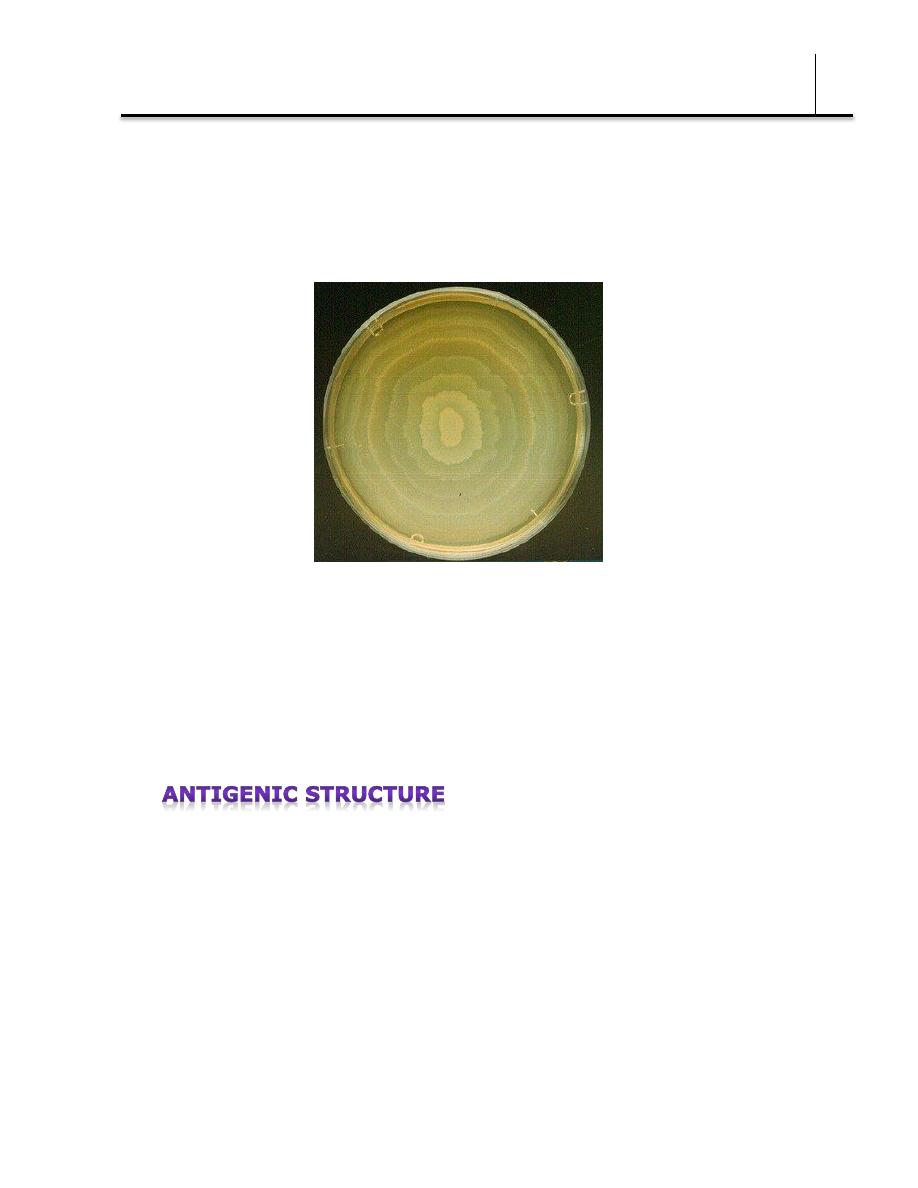

Klebsiella colonies are large and very mucoid and tend to unite with

prolonged incubation.

Klebsiella pneumoniae on Endo agar.

Large, mucous colonies after 24 hours of

cultivation in aerobic atmosphere, 37°C.

Mucous,

lactose

positive

colonies

of Klebsiella pneumoniae on MacConkey

agar. Cultivation 37°C, 24 hours.

Escherichia coli cultivated on blood agar.

Cultivation 24 hours in an aerobic atmosphere,

37°C. Colonies are without hemolysis but many

strains isolated from infections are beta-hemolytic

Escherichia coli cultivated on

MacConkey agar. Lactose positive

colonies. Cultivation 24 hours in an

aerobic atmosphere, 37°C.

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

4

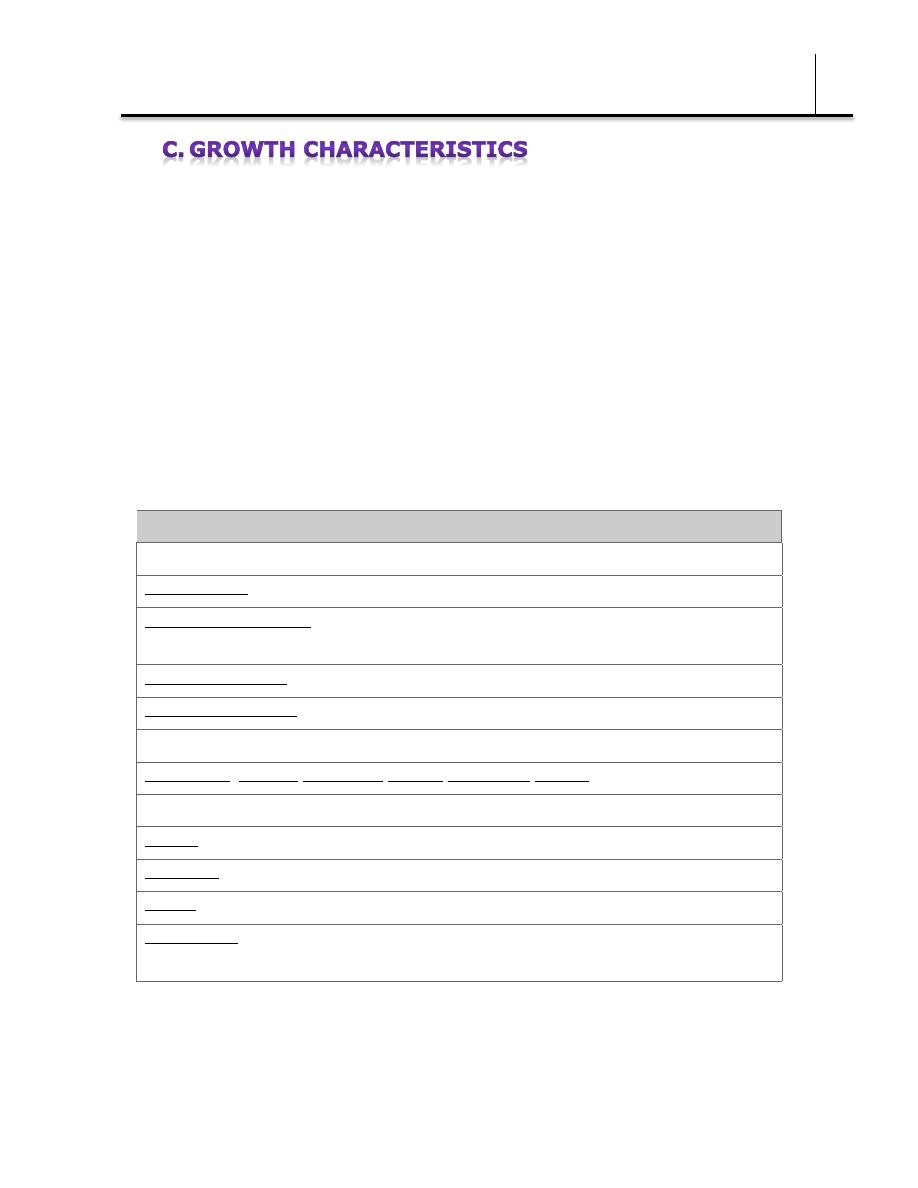

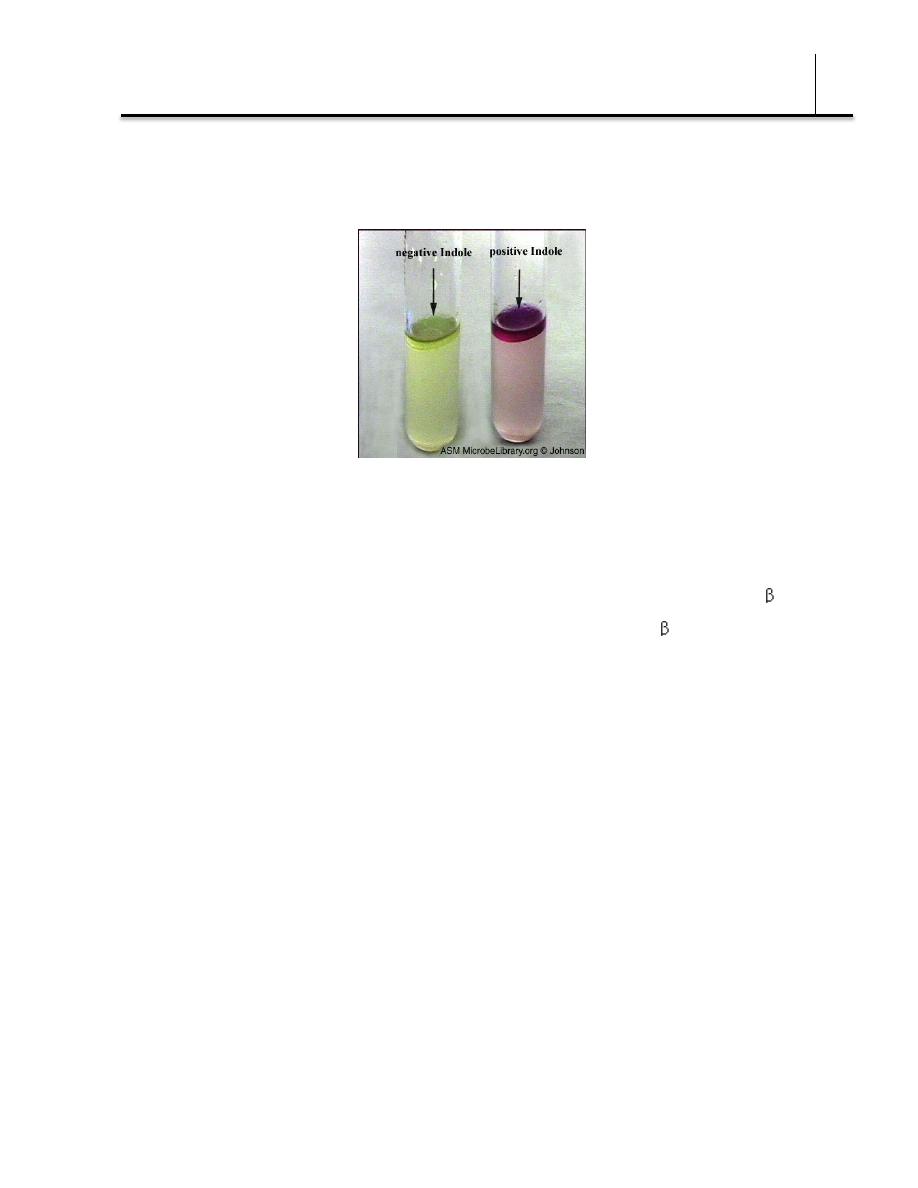

Carbohydrate fermentation patterns and the activity of amino acid

decarboxylases and other enzymes are used in biochemical

differentiation (Table 15–1). Some tests, eg, the production of indole

from tryptophan, are commonly used in rapid identification systems.

Culture on "differential" media that contain special dyes and

carbohydrates (eg, eosin-methylene blue [EMB], MacConkey, or

deoxycholate medium) distinguishes lactose-fermenting (colored) from

nonlactose-fermenting colonies (nonpigmented) and may allow rapid

presumptive identification of enteric bacteria (Table 15–2).

Table 15–2 Rapid, Presumptive Identification of Gram-Negative Enteric Bacteria

Lactose fermented rapidly

Escherichia coli: metallic sheen on differential media; motile; flat, nonviscous colonies

Enterobacter aerogenes: raised colonies, no metallic sheen; often motile; more viscous

growth

Enterobacter cloacae: similar to Enterobacter aerogenes

Klebsiella pneumoniae: very viscous, mucoid growth; nonmotile

Lactose fermented slowly

Edwardsiella, Serratia, Citrobacter, Arizona, Providencia, Erwinia

Lactose not fermented

Shigella species: nonmotile; no gas from dextrose

Salmonella species: motile; acid and usually gas from dextrose

Proteus species: "swarming" on agar; urea rapidly hydrolyzed (smell of ammonia)

Pseudomonas species (see Chapter 16): soluble pigments, blue-green and fluorescing;

sweetish smell

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

5

1. Escherichia—E coli typically produces positive tests for indole,

lysine decarboxylase, and mannitol fermentation and produces gas

from glucose.

The

amino

acid

tryptophan

is

found

in

nearly

all

proteins.

Positive Indole: Bacteria that contain tryptophanase can hydrolyse tryptophan to its metabolic

products (indole, pyruvic acid, ammonia) This will form a layer of red color on the surface

An isolate from urine can be quickly identified as E coli by its

hemolysis on blood agar. Over 90% of E coli isolates are positive for -

glucuronidase using the substrate 4-methylumbelliferyl- -glucuronide

(MUG). Isolates from anatomic sites other than urine, with

characteristic properties (above plus negative oxidase tests) often can

be confirmed as E coli with a positive MUG test.

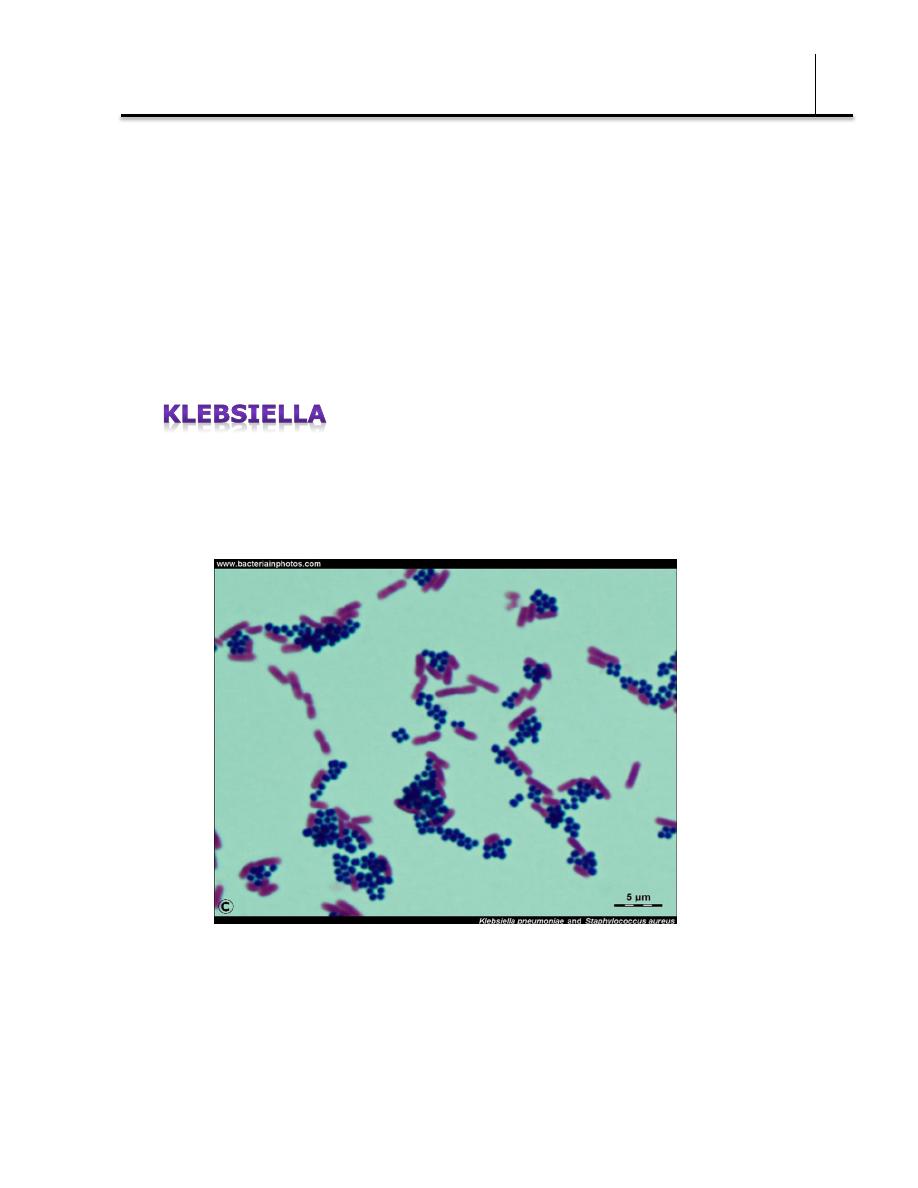

2. Klebsiella-Enterobacter-Serratia group—

Klebsiella

species

exhibit mucoid growth, large polysaccharide capsules, and lack of

motility, and they usually give positive tests for lysine decarboxylase

and citrate. Serratia produces DNase, lipase, and gelatinase.

Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Serratia usually give positive Voges-

Proskauer reactions.

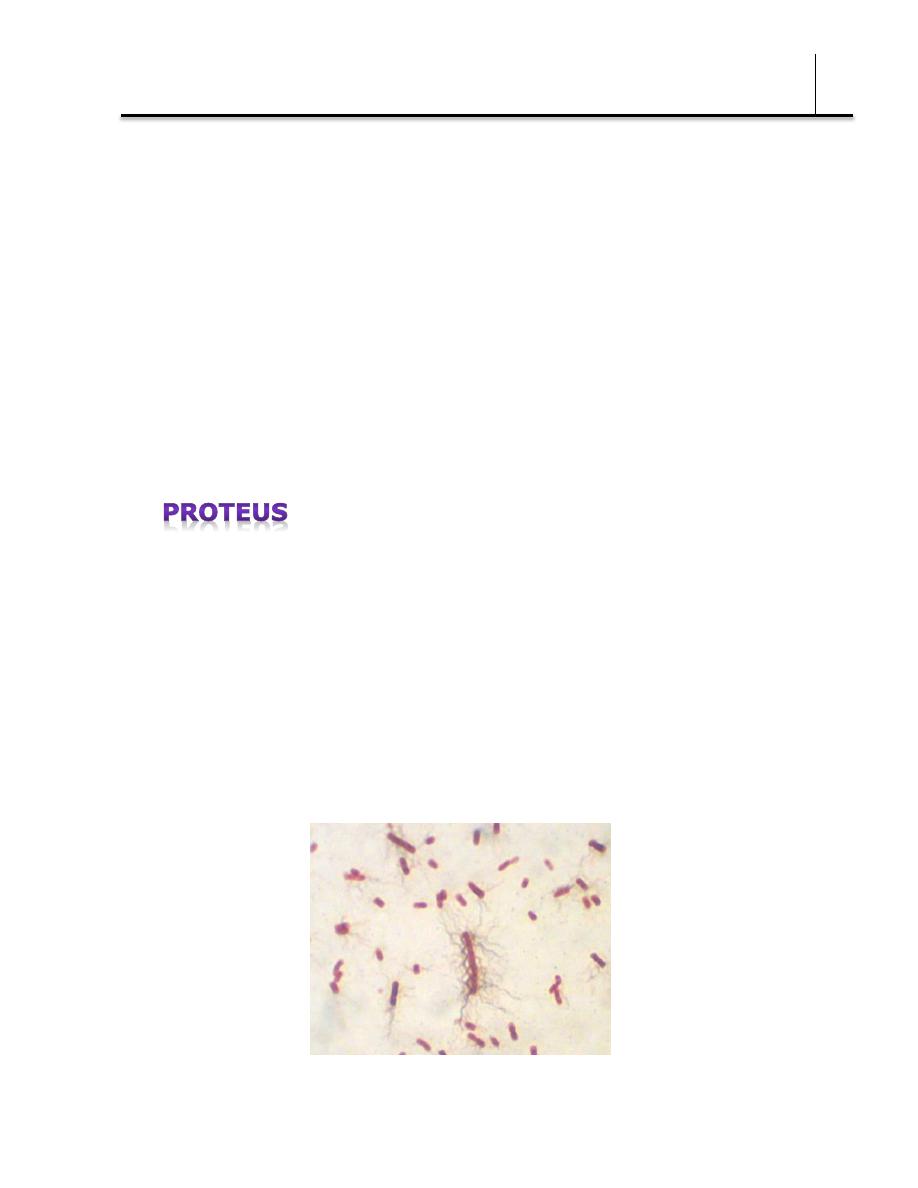

3. Proteus-Morganella-Providencia group—The members of this

group deaminate phenylalanine, are motile, grow on potassium

cyanide medium (KCN), and ferment xylose.

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

6

Proteus species move very actively by means of peritrichous flagella,

resulting in "swarming" on solid media unless the swarming is inhibited

by chemicals, eg, phenylethyl alcohol or CLED (cystine-lactose-

electrolyte-deficient) medium.

swarming growth of P. mirabilis inoculated centrally onto a blood agar plate is incubated

overnight @ 37 degrees celcius.

Copyright © 2013, MicrobLog: Microbiology Training Log

Proteus species and Morganella morganii are urease-positive.

The Proteus-Providencia group ferments lactose very slowly or not at

all. Proteus mirabilis is more susceptible to antimicrobial drugs,

including penicillins, than other members of the group.

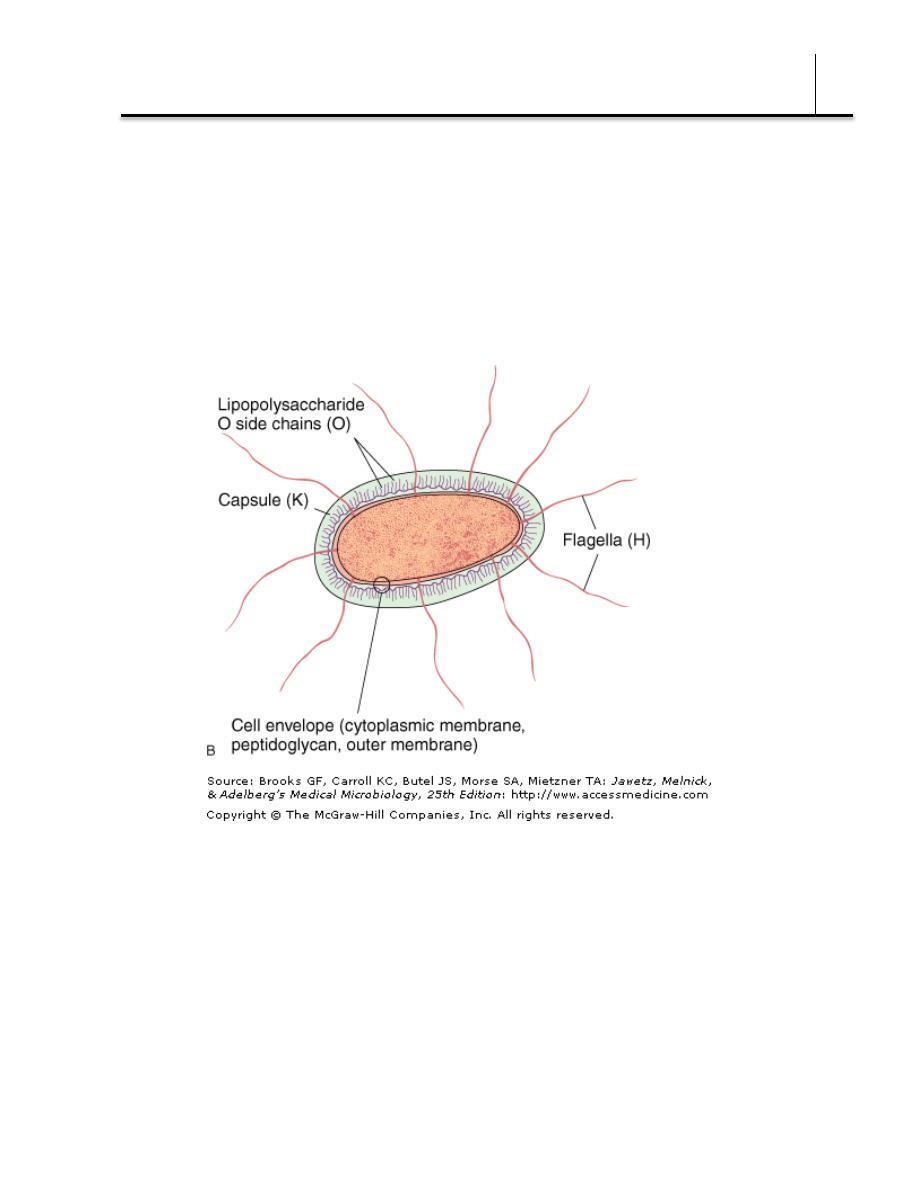

Enterobacteriaceae have a complex antigenic structure. They are

classified by more than 150 different heat-stable somatic O

(lipopolysaccharide) antigens, more than 100 heat-labile K (capsular)

antigens, and more than 50 H (flagellar) antigens .

O antigens are the most external part of the cell wall

lipopolysaccharide and consist of repeating units of polysaccharide.

Some O-specific polysaccharides contain unique sugars. O antigens are

resistant to heat and alcohol and usually are detected by bacterial

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

7

agglutination. Antibodies to O antigens are predominantly IgM.

While each genus of Enterobacteriaceae is associated with specific O

groups, a single organism may carry several O antigens. E coli may

cross-react with some Providencia, Klebsiella, and Salmonella species.

Occasionally, O antigens may be associated with specific human

diseases, eg, specific O types of E coli are found in diarrhea and in

urinary tract infections.

K antigens are external to O antigens on some but not all

Enterobacteriaceae. Some are polysaccharides, including the K

antigens of E coli; others are proteins. K antigens may interfere with

agglutination by O antisera, and they may be associated with virulence

(eg, E coli strains producing K1 antigen are prominent in neonatal

meningitis, and K antigens of E coli cause attachment of the bacteria

to epithelial cells prior to gastrointestinal or urinary tract invasion).

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

8

Klebsiellae form large capsules consisting of polysaccharides (K

antigens) covering the somatic (O or H) antigens and can be identified

by capsular swelling tests with specific antisera. Human infections of

the respiratory tract are caused particularly by capsular types 1 and 2;

those of the urinary tract, by types 8, 9, 10, and 24.

H antigens are located on flagella and are denatured or removed by

heat or alcohol. They are preserved by treating motile bacterial

variants with formalin. Such H antigens agglutinate with anti-H

antibodies, mainly IgG. The determinants in H antigens are a function

of the amino acid sequence in flagellar protein (flagellin). Within a

single serotype, flagellar antigens may be present in either or both of

two forms, called phase 1 , and phase 2.

The organism tends to change from one phase to the other; this is

called phase variation. H antigens on the bacterial surface may

interfere with agglutination by anti-O antibody.

There are many examples of overlapping antigenic structures between

Enterobacteriaceae and other bacteria. Most Enterobacteriaceae share

the O14 antigen of E coli. The type 2 capsular polysaccharide of

Klebsiella is very similar to the polysaccharide of type 2 pneumococci.

Some K antigens cross-react with capsular polysaccharides of

Haemophilus influenzae or Neisseria meningitidis. Thus, E coli

O75:K100:H5 can induce antibodies that react with H influenzae type

b.

The antigenic classification of Enterobacteriaceae often indicates the

presence of each specific antigen. Thus, the antigenic formula of an E

coli may be O55:K5:H21; that of Salmonella Schottmülleri is

O1,4,5,12:Hb:1,2.

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

9

Many gram-negative organisms produce bacteriocins. These high-

molecular-weight bactericidal proteins are produced by certain strains

of bacteria active against some other strains of the same or closely

related species. Their production is controlled by plasmids. Colicins are

produced by E coli, marcescens by Serratia, and pyocins by

Pseudomonas. Bacteriocin-producing strains are resistant to their own

bacteriocin; thus, bacteriocins can be used for "typing" of organisms.

Most gram-negative bacteria possess complex lipopolysaccharides in

their cell walls. These substances, cell envelope (cytoplasmic

membrane, peptidoglycan, outer membrane) endotoxins, have a

variety of pathophysiologic effects that are summarized in Chapter 9.

Many gram-negative enteric bacteria also produce exotoxins of clinical

importance. Some specific toxins are discussed in subsequent sections.

E coli is a member of the normal intestinal flora. Other enteric bacteria

(Proteus, Enterobacter, Klebsiella) are also found as members of the

normal intestinal flora but are considerably less common than E coli.

The enteric bacteria are sometimes found in small numbers as part of

the normal flora of the upper respiratory and genital tracts. The enteric

bacteria generally do not cause disease, and in the intestine they may

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

10

even contribute to normal function and nutrition.

The bacteria become pathogenic only when they reach tissues outside

of their normal intestinal or other less common normal flora sites. The

most frequent sites of clinically important infection are the urinary

tract, biliary tract, and other sites in the abdominal cavity, infections of

the blood stream, prostate gland, lung, bone, meninges can also be

present. When normal host defenses are inadequate—particularly in

infancy or old age, in the terminal stages of other diseases, after

immunosuppression, or with indwelling venous or urethral catheters—

localized clinically important infections can result, and the bacteria

may reach the bloodstream and cause sepsis.

The clinical manifestations of infections with E coli and the other

enteric bacteria depend on the site of the infection and cannot be

differentiated by symptoms or signs from processes caused by other

bacteria.

1. Urinary tract infection—E coli is the most common cause of

urinary tract infection and accounts for approximately 90% of first

urinary tract infections in young women. The symptoms and signs

include urinary frequency, dysuria, hematuria, and pyuria. Flank pain

is associated with upper tract infection. None of these symptoms or

signs is specific for E coli infection. Urinary tract infection can result in

bacteremia with clinical signs of sepsis.

Most of the urinary tract infections that involve the bladder or kidney

in an otherwise healthy host are caused by a small number of O

antigen types that have specifically elaborated virulence factors that

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

11

facilitate colonization and subsequent clinical infections. These

organisms are designated as uropathogenic E coli. Typically these

organisms produce hemolysin, which is cytotoxic and facilitates tissue

invasion. Those strains that cause pyelonephritis (from Greek pyelum,

meaning "renal pelvis", pyelonephritis is an inflammation of the renal

parenchyma, calyces, and pelvis) express K antigen and elaborate a

specific type of pilus, P fimbriae, which binds to the P blood group

antigen (note: P blood group system, classification of human blood

based on the presence of any of three substances known as the P, P1,

and Pk antigens on the surfaces of red blood cells. These antigens are

also expressed on the surfaces of cells lining the urinary tract, where

they have been identified as adhesion sites for Escherichia coli

bacteria, which cause urinary tract infections.).

2. E coli-associated diarrheal diseases—E coli that cause diarrhea

are extremely common worldwide. These E coli are classified by the

characteristics of their virulence properties (see below), and each

group causes disease by a different mechanism. The small or large

bowel epithelial cell adherence properties are encoded by genes on

plasmids.

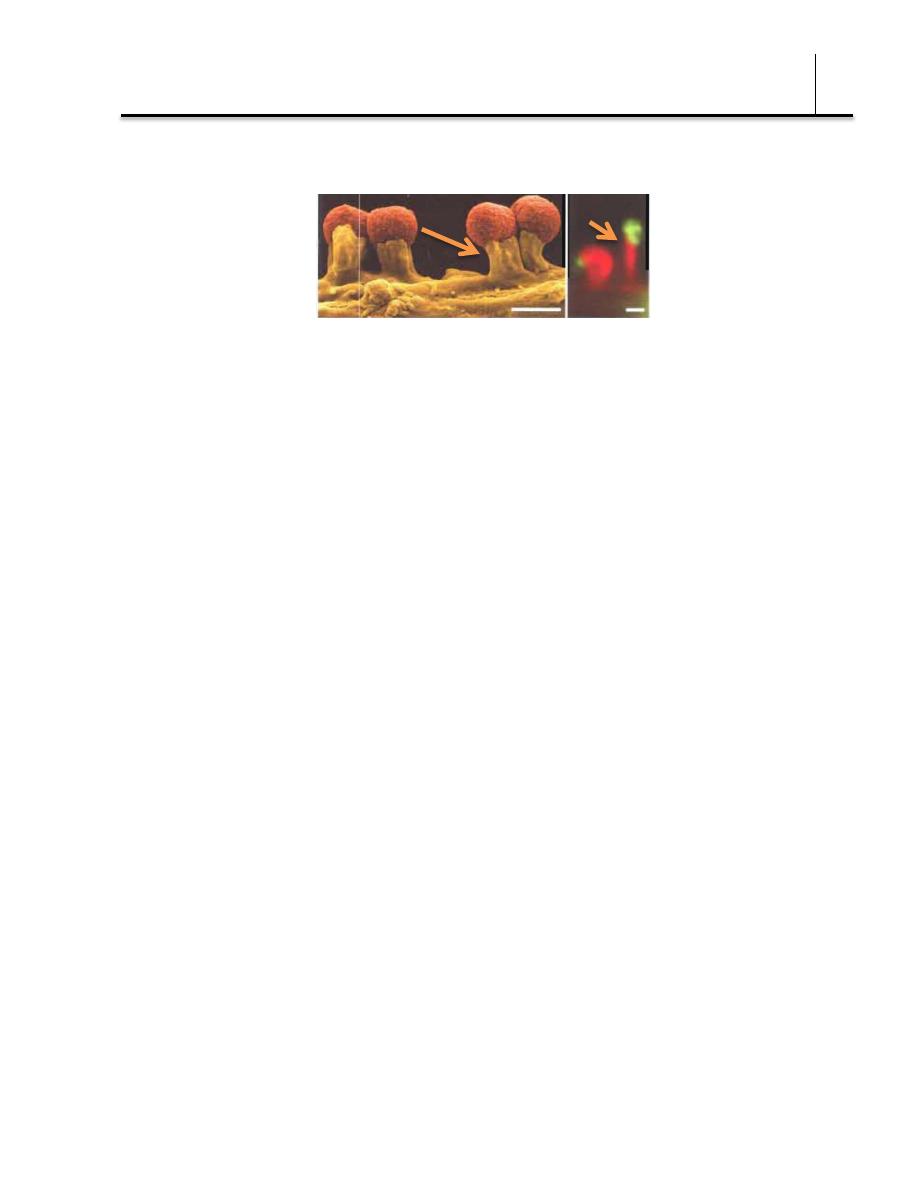

1) Enteropathogenic E coli (EPEC) is an important cause of

diarrhea in infants, especially in developing countries. EPEC

previously was associated with outbreaks of diarrhea in nurseries

in developed countries. EPEC adhere to the mucosal cells of the

small bowel. There is loss of microvilli (effacement “shortening

or thining of tissue”), formation of filamentous actin pedestals or

cup-like structures, and, occasionally, entry of the EPEC into the

mucosal cells.

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

12

formation of a raised, pedestal-like structure beneath the bacterium that characterizes

this lesion (© Deibel et al., 1998)

Lesions are characterized by a localized loss of microvilli and intimate

adherence of bacteria to the cell surface followed by recruitment of the

cellular actin assembly machinery to sites of bacterial attachment,

resulting in the formation of actin-rich pseudopod-like structures

termed pedestals to which the bacteria intimately adhere.

Characteristic lesions can be seen on electron micrographs of

small bowel biopsy lesions.

The result of EPEC infection is sever, watery diarrhea, vomiting,

and fever, which is usually self-limited but can be chronic. EPEC

diarrhea has been associated with multiple specific serotypes of

E coli; strains are identified by O antigen and occasionally by H

antigen typing. Tests to identify EPEC are performed in reference

laboratories. The duration of the EPEC diarrhea can be shortened

and the chronic diarrhea cured by antibiotic treatment.

2) Enterotoxigenic E coli (ETEC) is a common cause of

"traveler's diarrhea" and a very important cause of diarrhea in

infants in developing countries. ETEC colonization factors specific

for humans promote adherence of ETEC to epithelial cells of the

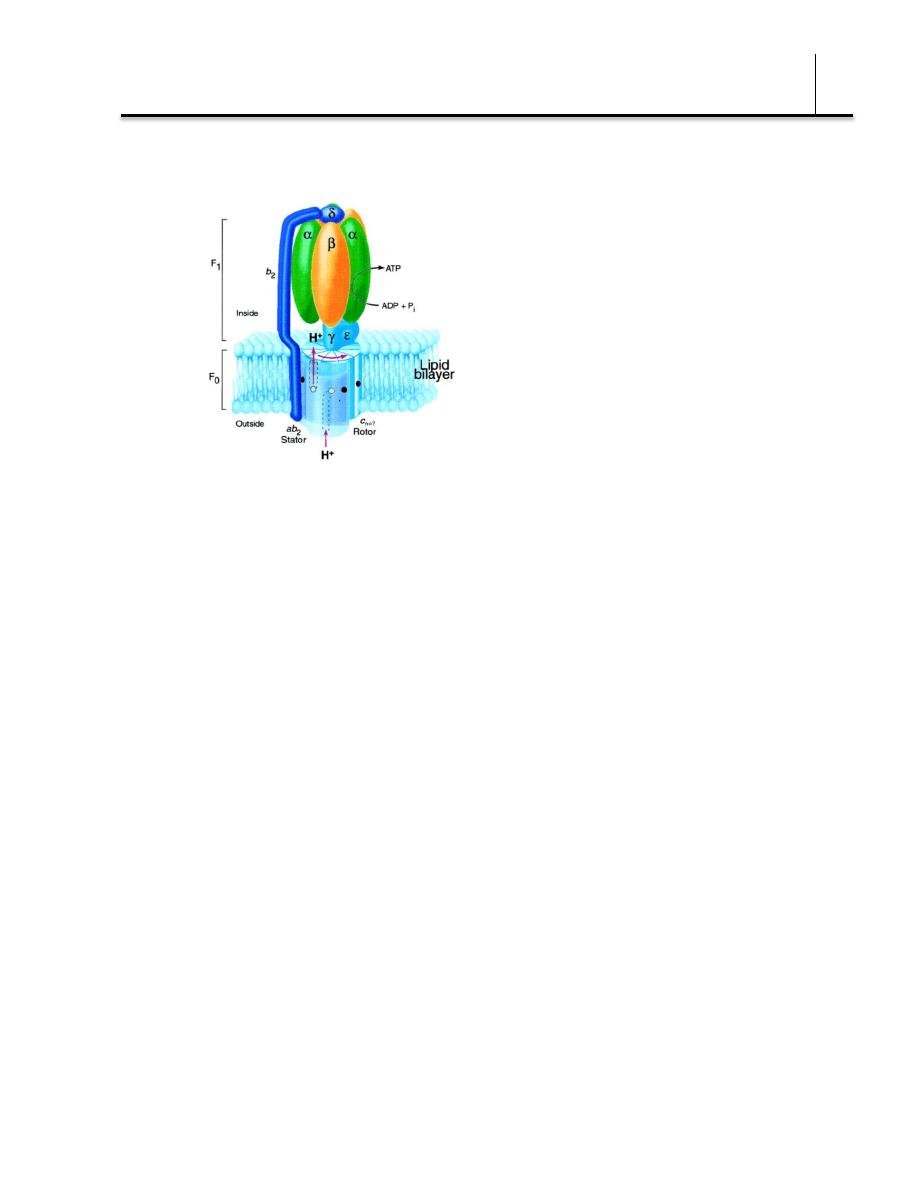

small bowel. Some ETEC produce heat-labile exotoxin (LT).

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

13

The bacteria subunit B attach to the ganglioside (note: The name

ganglioside came from the first isolation of lipids from ganglion

cells of the brain. Ganglioside is

a component of the cell plasma

signal transduction events) at

the brush border of epithelial

cells of the small intestine and

facilitates the entry of subunit A

into the cell, where the latter

activates adenylyl cyclase. This markedly increases the local

concentration of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), which

results in intense and prolonged hypersecretion of water and

chlorides and inhibits the reabsorption of sodium. The gut lumen

is distended with fluid, and hypermotility and diarrhea ensue,

lasting for several days.

LT is antigenic and cross-reacts with the enterotoxin of Vibrio

cholerae. LT stimulates the production of neutralizing antibodies

in the serum (and perhaps on the gut surface) of persons

previously infected with enterotoxigenic E coli. Persons residing

in areas where such organisms are highly prevalent (eg, in some

developing countries) are likely to possess antibodies and are

less prone to develop diarrhea on reexposure to the LT-

producing E coli.

Some strains of ETEC produce the heat-stable enterotoxin (ST), which

is under the genetic control of a heterogeneous group of plasmids. ST

activates guanylyl cyclase in enteric epithelial cells and stimulates fluid

secretion. Many ST-positive strains also produce LT. The strains with

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

14

both toxins produce a more severe diarrhea.

The plasmids carrying the genes for enterotoxins (LT, ST) also may

carry genes for the colonization factors that facilitate the attachment

of E coli strains to intestinal epithelium.

Care in the selection and consumption of foods potentially

contaminated with ETEC is highly recommended to help prevent

traveler's diarrhea. Antimicrobial prophylaxis can be effective but may

result in increased antibiotic resistance in the bacteria and probably

should not be uniformly recommended. Once diarrhea develops,

antibiotic treatment effectively shortens the duration of disease.

3) Shiga toxin producing E coli (STEC) are named for the

cytotoxic toxins they produce. There are at least two antigenic

forms of the toxin referred to as Shiga-like toxin 1 and Shiga-like

toxin 2. STEC has been associated with hemorrhagic colitis, a

severe form of diarrhea, and with hemolytic uremic syndrome, a

disease resulting in acute renal failure, microangiopathic

hemolytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia. The Shiga-like toxins

have many properties that are similar to the Shiga toxin

produced by some strains of Shigella dysenteriae type 1;

however, the two toxins are antigenically and genetically

distinct. Of the E coli serotypes that produce Shiga toxin,

O157:H7 is the most common and is the one that can be

identified in clinical specimens. STEC O157:H7 does not use

sorbitol, unlike most other E coli, and is negative on sorbitol

MacConkey agar (sorbitol is used instead of lactose); O157:H7

strains also are negative on MUG tests (note: MUG is a test used

to determine if there are coliforms in food or water samples. The

detection of E. coli with MUG is based on the ability of beta-

glucuronidase, an enzyme possessed by most E. coli strains, to

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

15

hydrolyze 4-methylumbelliferyl-beta-D-glucuronide (MUG). The

hydrolysis of MUG by E. coli yields a fluorescent end

product. Development of fluorescence allows the detection of E.

coli). Many of the non-O157 serotypes may be sorbitol positive,

when grown in culture. Specific antisera are used to identify the

O157:H7 strains. Assays for Shiga toxin using commercially

available enzyme immunoassays are done in many laboratories.

Other sensitive test methods include cell culture cytotoxin

testing and polymerase chain reaction PCR for the direct

detection of toxin genes from stool samples. Many cases of

hemorrhagic colitis and its associated complications can be

prevented by thoroughly cooking ground beef.

4) Enteroinvasive E coli (EIEC) produces a disease very similar

to shigellosis. The disease occurs most commonly in children in

developing countries and in travelers to these countries. Like

Shigella, EIEC strains are non-lactose or late lactose fermenters

and are nonmotile. EIEC produce disease by invading intestinal

mucosal epithelial cells.

5) Enteroaggregative E coli (EAEC) causes acute and chronic

diarrhea (>14 days in duration) in persons in developing

countries. These organisms also are the cause of food-borne

illnesses in industrialized countries. They are characterized by

their specific patterns of adherence to human cells. EAEC

produce ST-like toxin (see above) and a hemolysin.

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

16

3. Sepsis—When normal host defenses are inadequate, E coli may

reach the bloodstream and cause sepsis. Newborns may be highly

susceptible to E coli sepsis because they lack IgM antibodies. Sepsis

may occur secondary to urinary tract infection.

4. Meningitis—E coli and group B streptococci are the leading causes

of meningitis in infants. Approximately 75% of E coli from meningitis

cases have the K1 antigen.

Klebsiella pneumoniae is present in the respiratory tract and feces

of about 5% of normal individuals.

It causes a small proportion (about 1%) of bacterial pneumonias. K

pneumoniae can produce extensive hemorrhagic necrotizing

consolidation of the lung. It produces urinary tract infection and

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

17

bacteremia with focal lesions in debilitated patients. Other enterics

also may produce pneumonia. Klebsiella sp. rank among the top ten

bacterial pathogens responsible for hospital-acquired infections. Two

other klebsiellae are associated with inflammatory conditions of the

upper respiratory tract: Klebsiella pneumoniae subspecies ozaenae has

been isolated from the nasal mucosa in ozena (Ozena is a disease of

the nose in which the bony ridges and mucous membranes of the nose

waste away.), and Klebsiella pneumoniae subspecies rhinoscleromatis

from rhinoscleroma, a destructive granuloma of the nose and pharynx.

Klebsiella granulomatis causes a chronic genital ulcerative disease.

Proteus species produce infections in humans only when the bacteria

leave the intestinal tract. They are found in urinary tract infections and

produce bacteremia, pneumonia, and focal lesions in debilitated

patients or those receiving intravenous infusions. P mirabilis causes

urinary tract infections and occasionally other infections. Proteus

vulgaris and Morganella morganii are important nosocomial pathogens

(Greek "nosus" meaning "disease" , "komeion" meaning "to take care

of" so nosocomial meaning is hospital acquired infections).

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

18

Proteus species produce urease, resulting in rapid hydrolysis of urea

with liberation of ammonia. Thus, in urinary tract infections with

Proteus, the urine becomes alkaline, promoting stone formation and

making acidification virtually impossible. The rapid motility of Proteus

may contribute to its invasion of the urinary tract.

Strains of Proteus vary greatly in antibiotic sensitivity. P mirabilis is

often inhibited by penicillins; the most active antibiotics for other

members of the group are aminoglycosides and cephalosporins.

Specimens

Specimens include urine, blood, pus, spinal fluid, sputum, or other

material, as indicated by the localization of the disease process.

Smears

The Enterobacteriaceae resemble each other morphologically. The

presence of large capsules is suggestive of Klebsiella.

Culture

Specimens are plated on both blood agar and differential media. With

differential media, rapid preliminary identification of gram-negative

enteric bacteria is often possible.

Immunity

Specific antibodies develop in systemic infections, but it is uncertain

whether significant immunity to the organisms follows.

No single specific therapy is available. The sulfonamides, ampicillin,

cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides have marked

antibacterial effects against the enterics, but variation in susceptibility

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

19

is great, and laboratory tests for antibiotic susceptibility are essential.

Multiple drug resistance is common and is under the control of

transmissible plasmids.

Certain conditions predisposing to infection by these organisms require

surgical correction, eg, relief of urinary tract obstruction, closure of a

perforation in an abdominal organ, or resection of a bronchiectatic

portion of lung. Treatment of gram-negative bacteremia and

impending septic shock requires rapid institution of antimicrobial

therapy, restoration of fluid and electrolyte balance, and treatment of

disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Various means have been proposed for the prevention of traveler's

diarrhea, including daily ingestion of bismuth subsalicylate suspension

(bismuth subsalicylate can inactivate E coli enterotoxin in vitro) and

regular doses of tetracyclines or other antimicrobial drugs for limited

periods. Because none of these methods are entirely successful or

lacking in adverse effects, it is widely recommended that caution be

observed in regard to food and drink in areas where environmental

sanitation is poor and that early and brief treatment (eg, with

ciprofloxacin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) be substituted for

prophylaxis.

The enteric bacteria establish themselves in the normal intestinal tract

within a few days after birth and from then on constitute a main

portion of the normal aerobic (facultative anaerobic) microbial flora. E

coli is the example. Enterics found in water or milk are accepted as

proof of fecal contamination from sewage or other sources.

Enteropathogenic E coli serotypes should be controlled. Some of the

enterics constitute a major problem in hospital infection. It is

Bacteriology (Lec 3)

Dr. Donya A Makki Enterobacteriaceae

20

particularly important to recognize that many enteric bacteria are

"opportunists" that cause illness when they are introduced into

debilitated patients. Within hospitals or other institutions, these

bacteria commonly are transmitted by personnel, or instruments. Their

control depends on hand washing, rigorous asepsis, sterilization of

equipment, disinfection, restraint in intravenous therapy, and strict

precautions in keeping the urinary tract sterile (ie, closed drainage).