Chapter 15

Digestive

system

Ch. 15 – Part 1

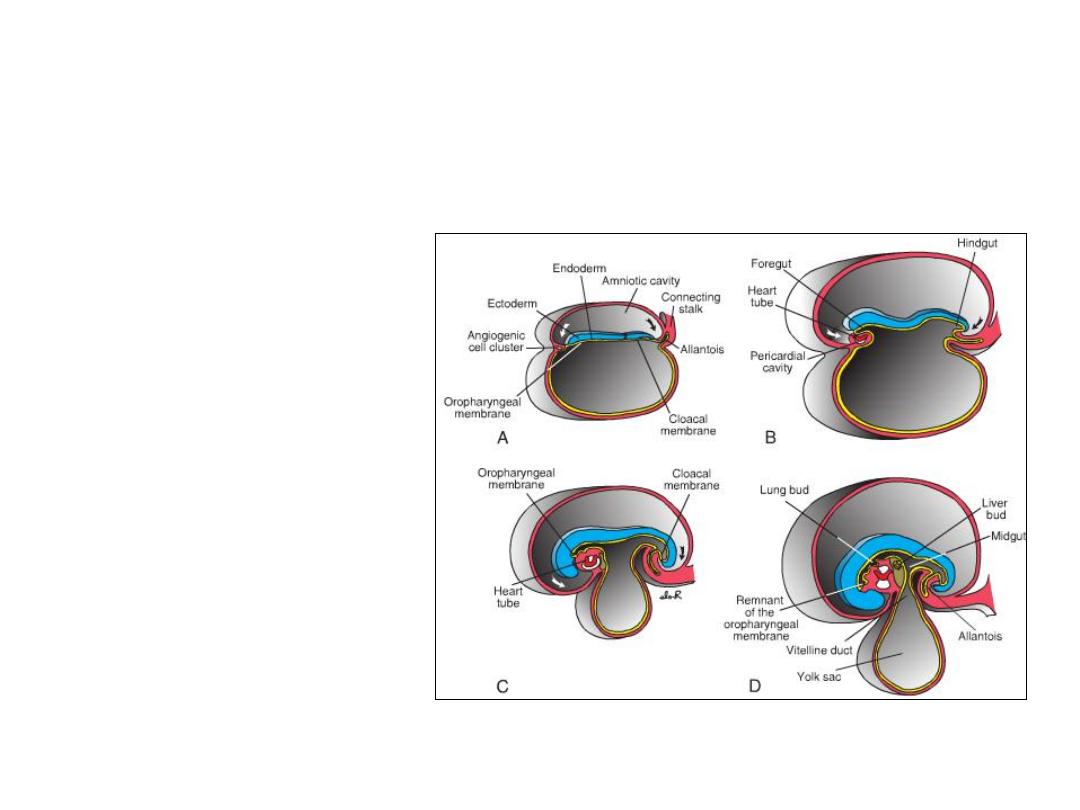

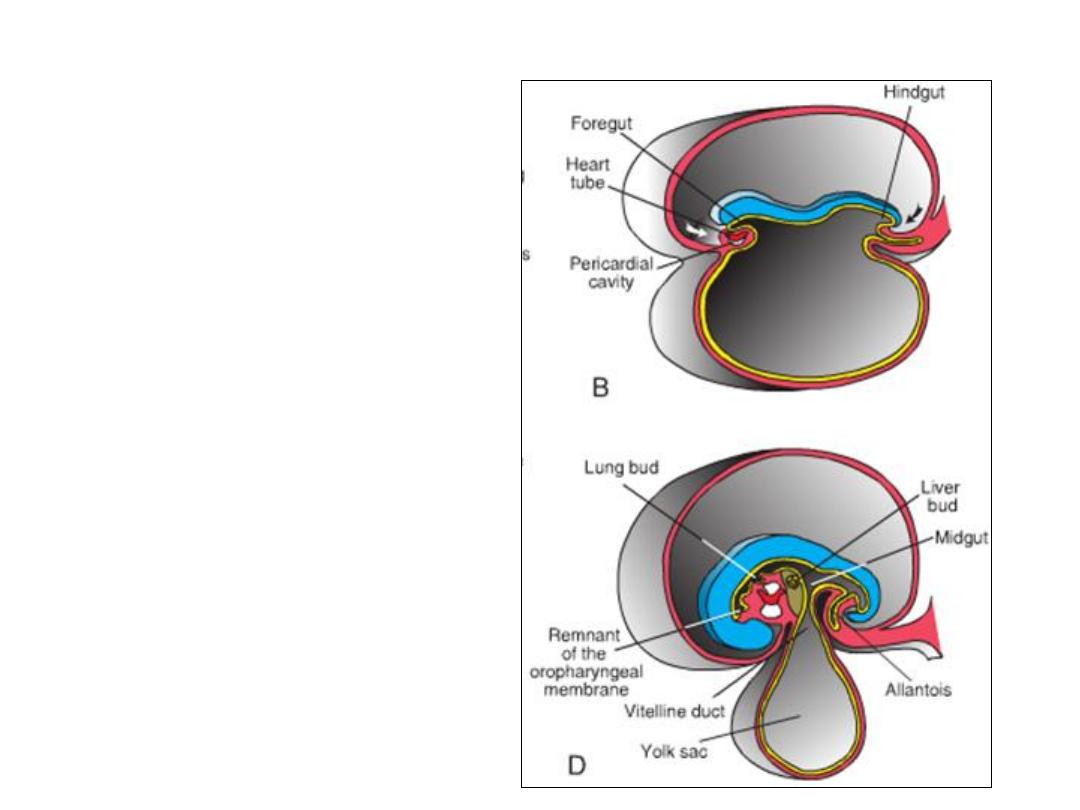

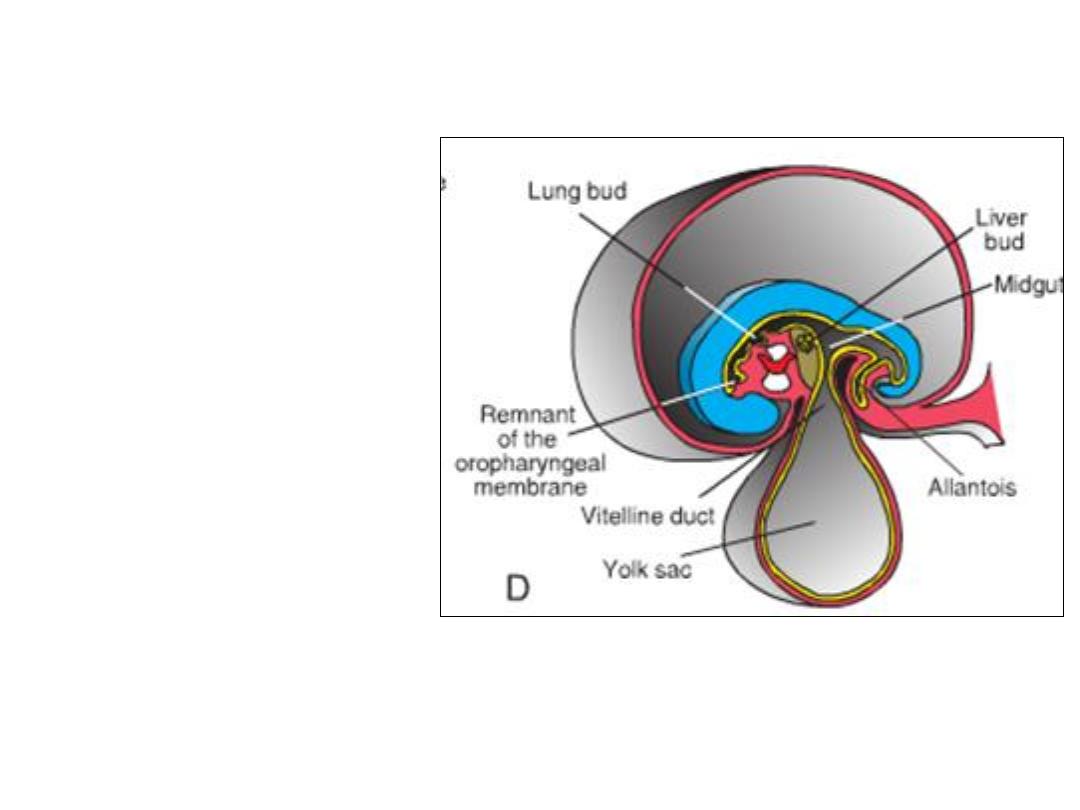

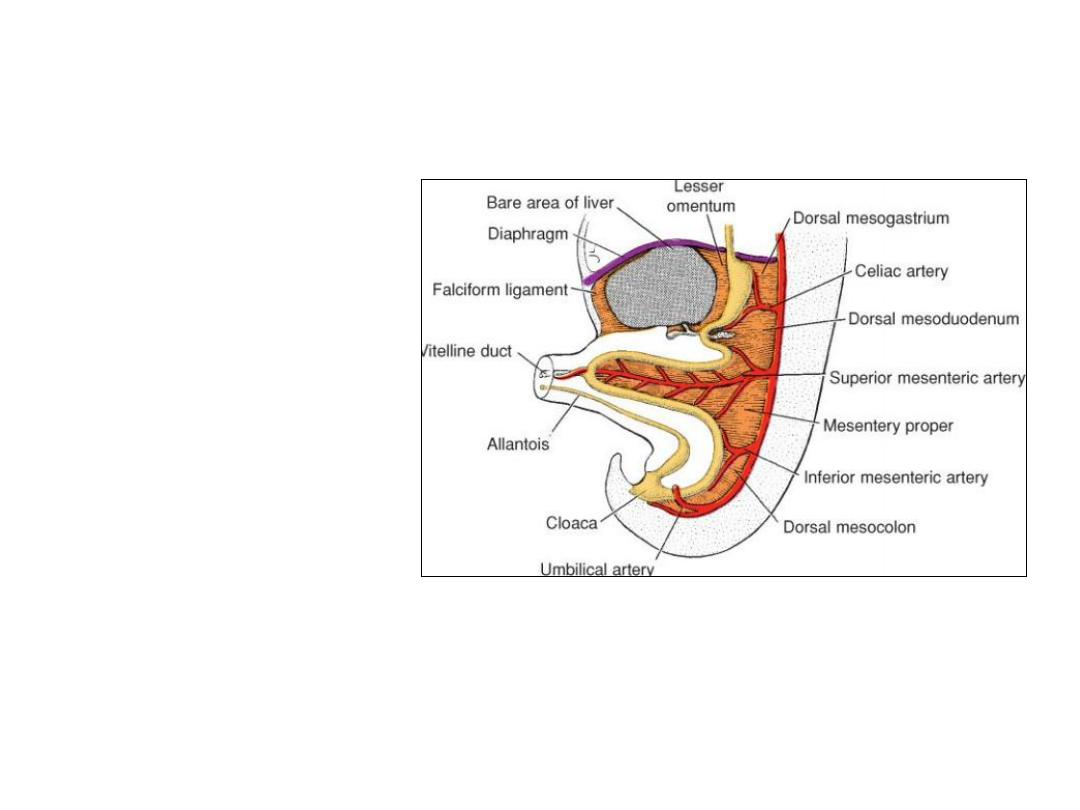

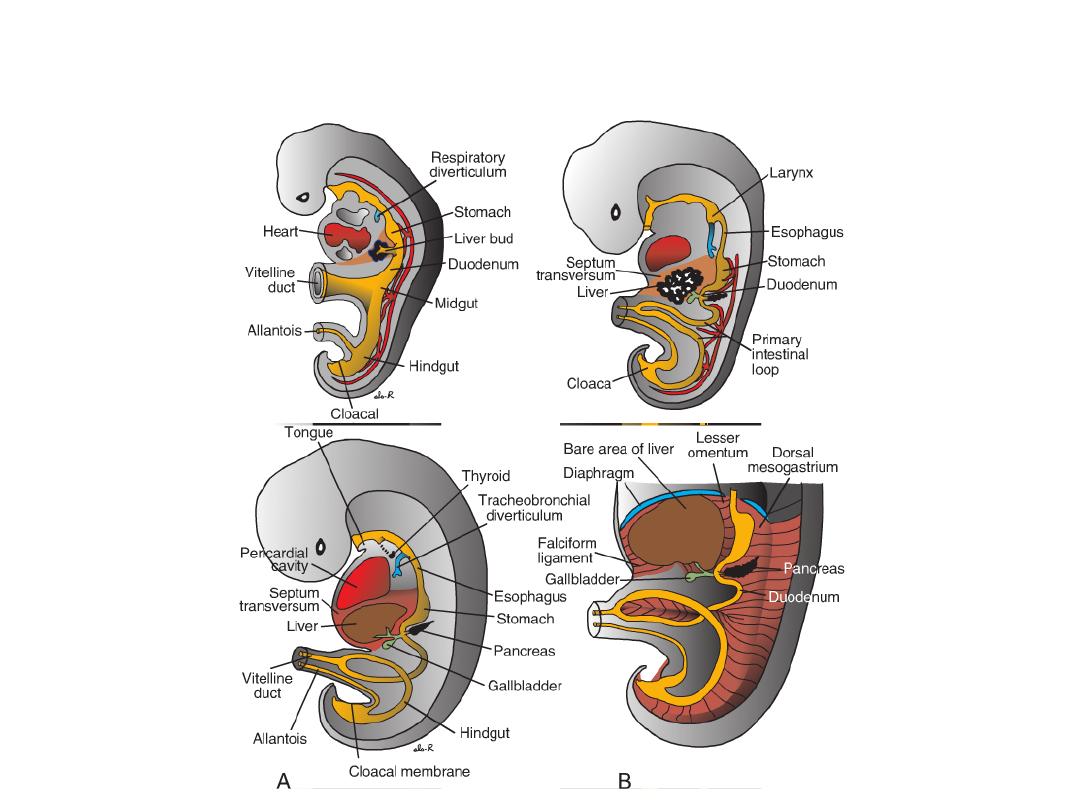

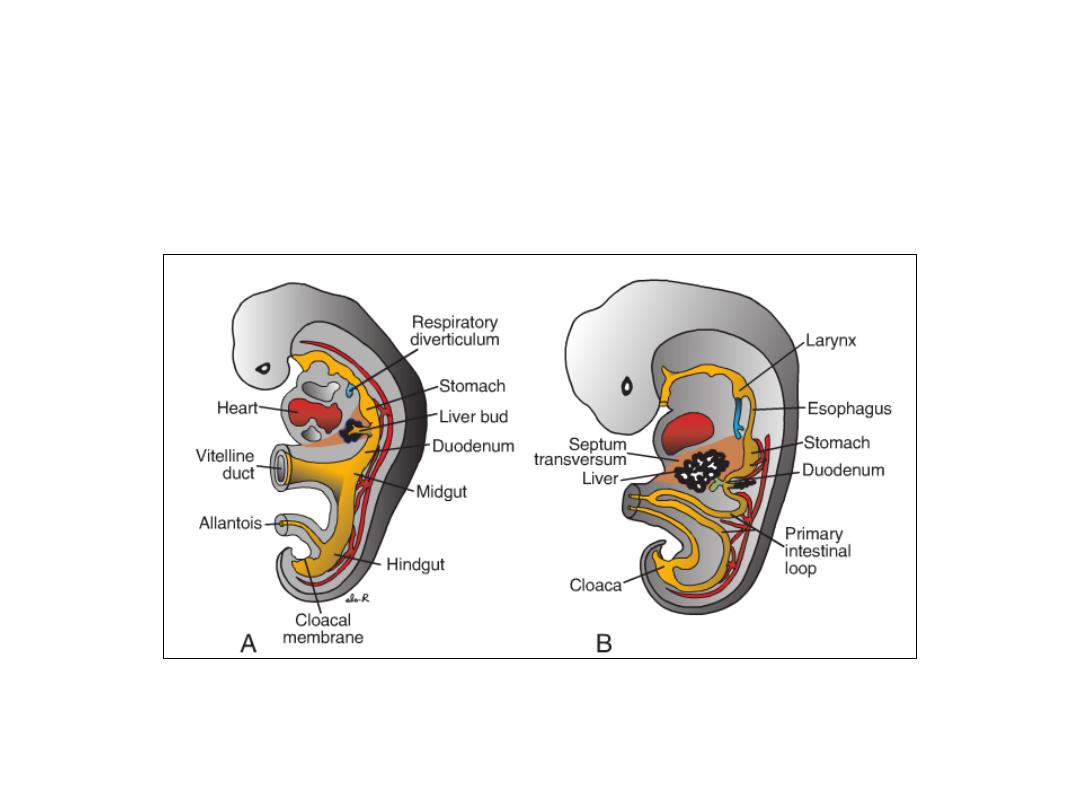

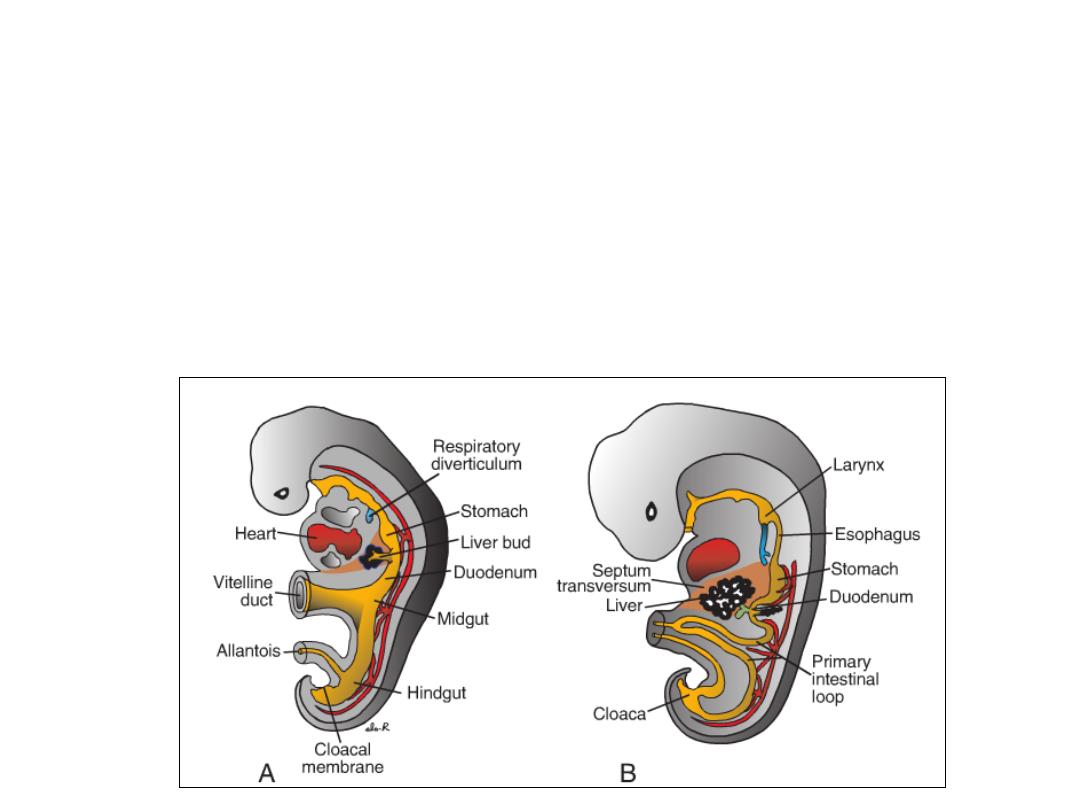

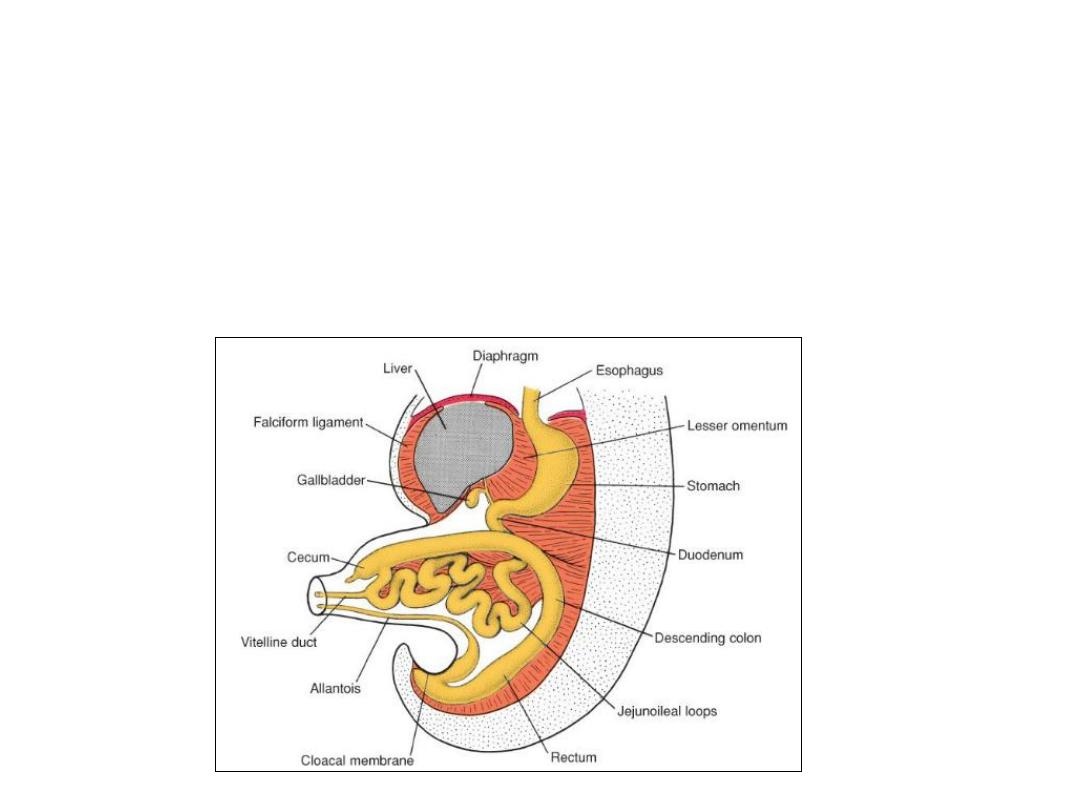

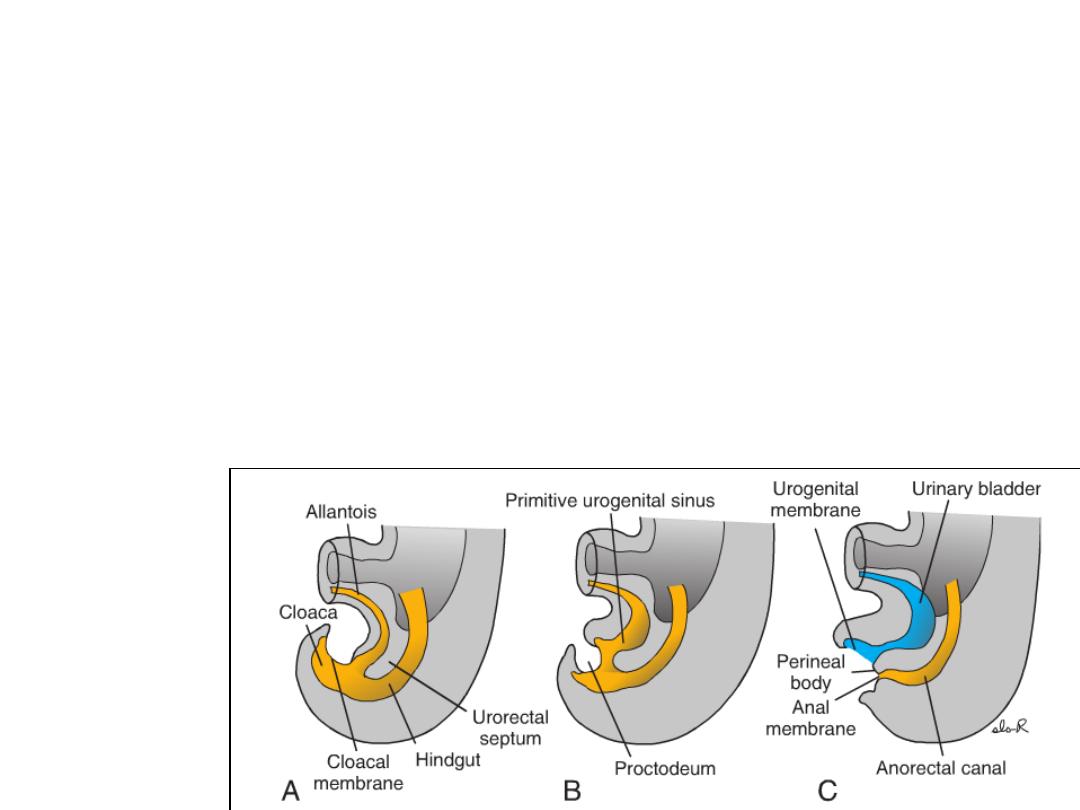

Figure: Sagittal sections

through embryos at

various stages of

development

demonstrating the effect of

cephalocaudal and lateral

folding on the position of

the endoderm-lined cavity.

Note formation of the

foregut, mid-gut, and

hindgut.

A. Presomite embryo.

B. Embryo with seven

somites.

C. Embryo with 14 somites.

D. At the end of the first

month.

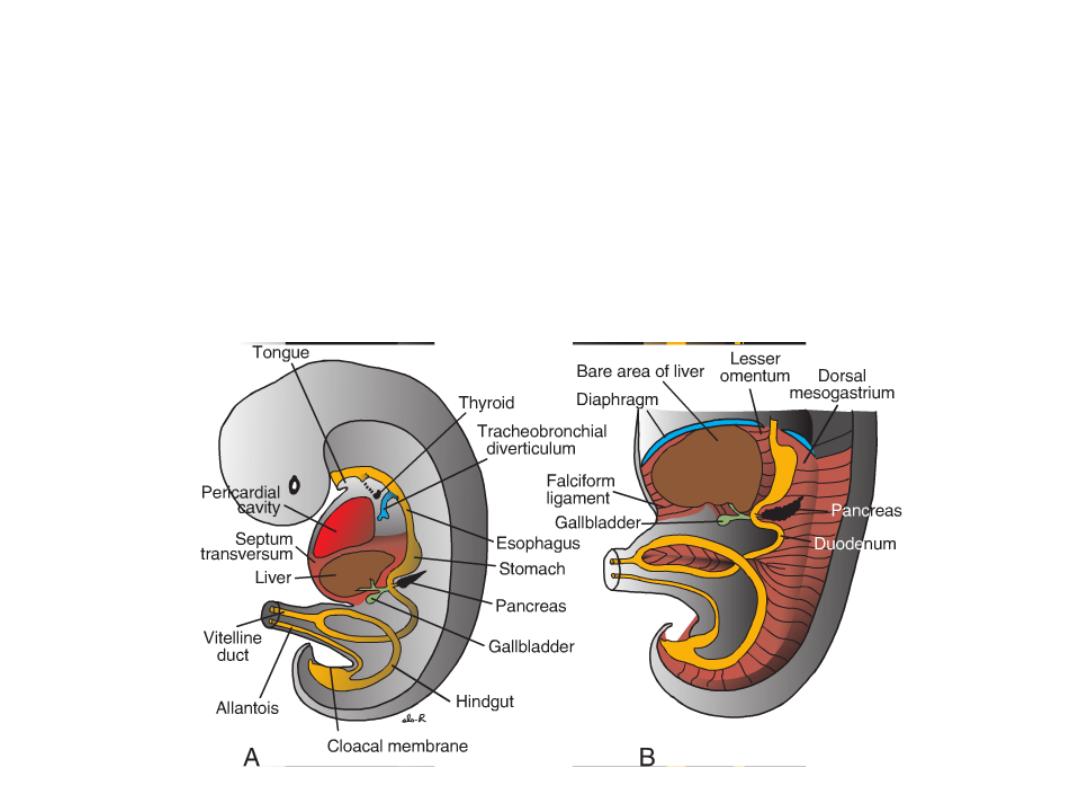

• As a result of cephalo-caudal and lateral folding of the embryo, a portion

of the endoderm-lined yolk sac cavity is incorporated into the embryo to

form the primitive gut.

• Two other portions of the endoderm-lined cavity, the yolk sac and the

allantois, remain outside the embryo.

DIVISIONS OF THE GUT TUBE

•In the cephalic and caudal parts

of the embryo, the primitive gut

forms a blind-ending tube, the

foregut and hindgut,

respectively. The middle part,

the midgut, remains temporally

connected to the yolk sac by

means of the vitelline duct, or

yolk stalk.

1- THE FOREGUT:

•The pharyngeal gut, or pharynx,

extends from the oropharyngeal

membrane to the respiratory

diverticulum and is part of the

foregut.

•The remainder of the foregut

lies caudal to the pharyngeal

tube and extends as far caudally

as the liver outgrowth.

DIVISIONS OF THE GUT TUBE

2- THE MIDGUT begins caudal to

the liver bud and extends to

the junction of the right two

thirds and left third of the

transverse colon in the adult.

3- THE HINDGUT extends from

the left third of the transverse

colon to the cloacal

membrane.

• Endoderm: forms the epithelial lining of the digestive tract

and gives rise to the specific cells (the parenchyma) of glands,

such as hepatocytes and the exocrine and endocrine cells of

the pancreas.

• Visceral mesoderm: forms

– Muscle, connective tissue, and peritoneal components of the wall of

the gut

– stroma (connective tissue) for the glands

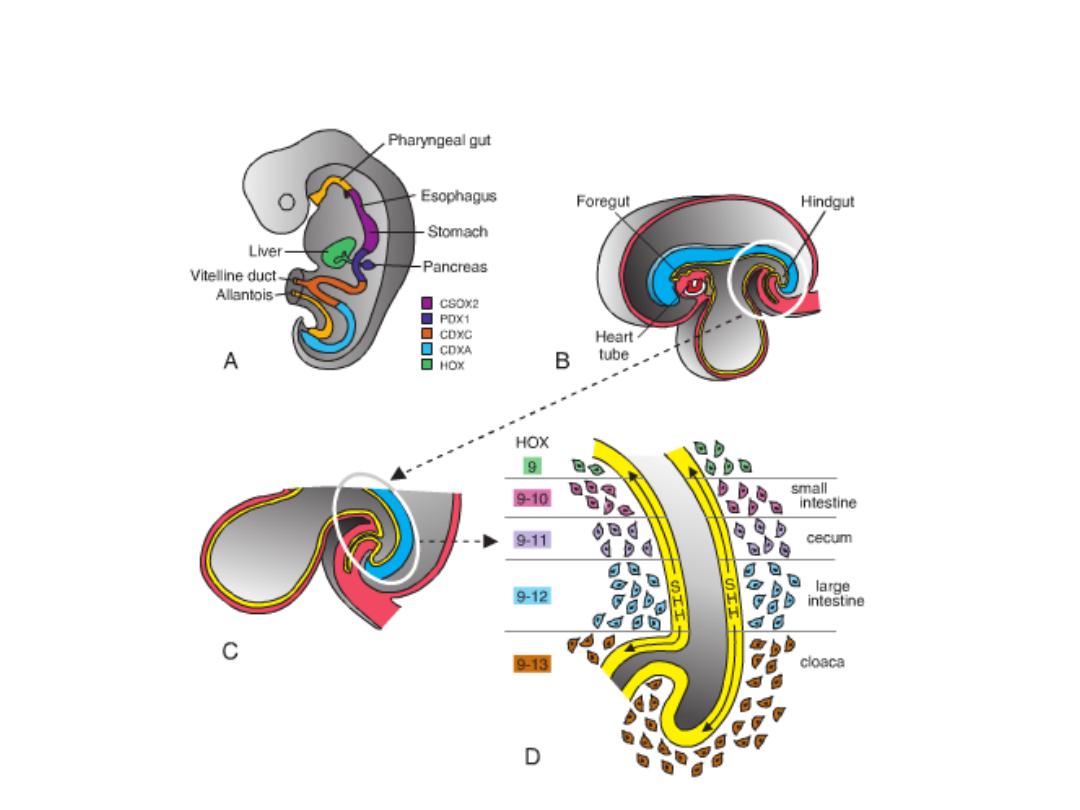

MOLECULAR REGULATION OF GUT TUBE DEVELOPMENT

1- Regional specification of the gut tube into different components occurs

during the time that the lateral body folds are bringing the two sides of

the tube together.

2- Specification is initiated by transcription factors expressed in the different

regions of the gut tube:

– SOX2 “specifies” the esophagus and stomach;

– PDX1 ,the duodenum;

– CDXC , the small intestine; and

– CDXA , the large intestine and rectum.

3- This initial patterning is stabilized by Epithelial–mesenchymal interaction

(between the endoderm and visceral mesoderm adjacent to the gut tube)

and is initiated by sonic hedgehog (SHH) expression throughout the gut

tube.

MOLECULAR REGULATION OF GUT TUBE

DEVELOPMENT

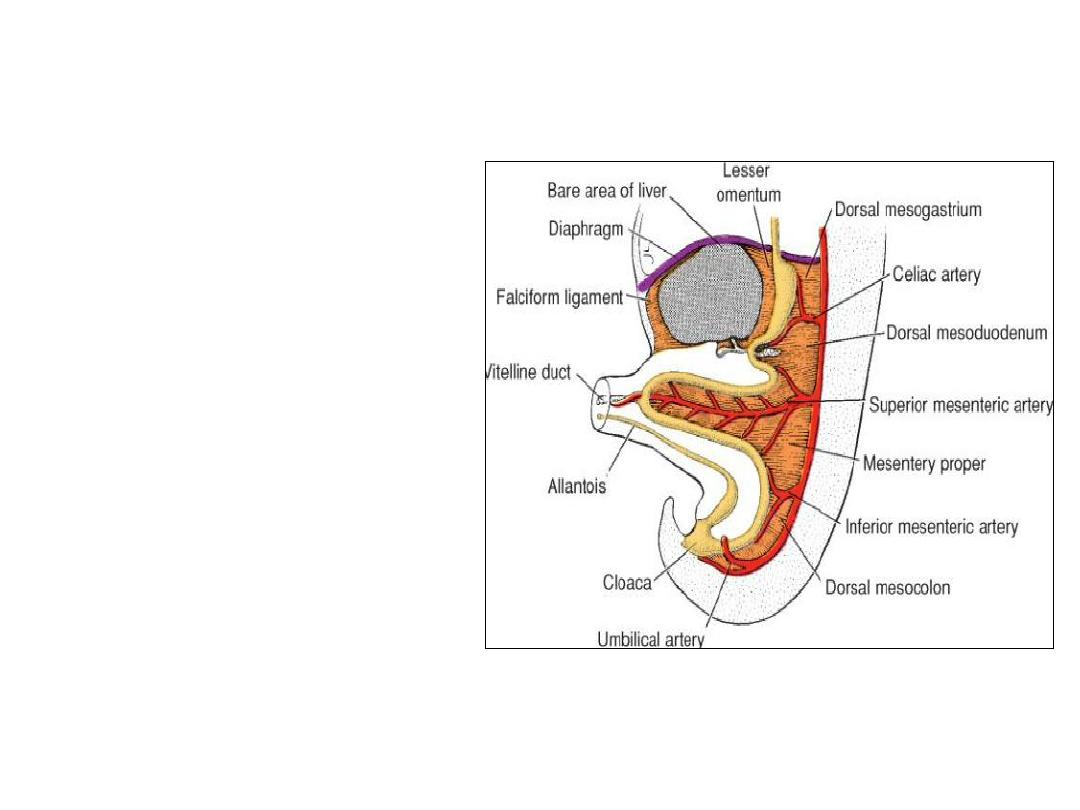

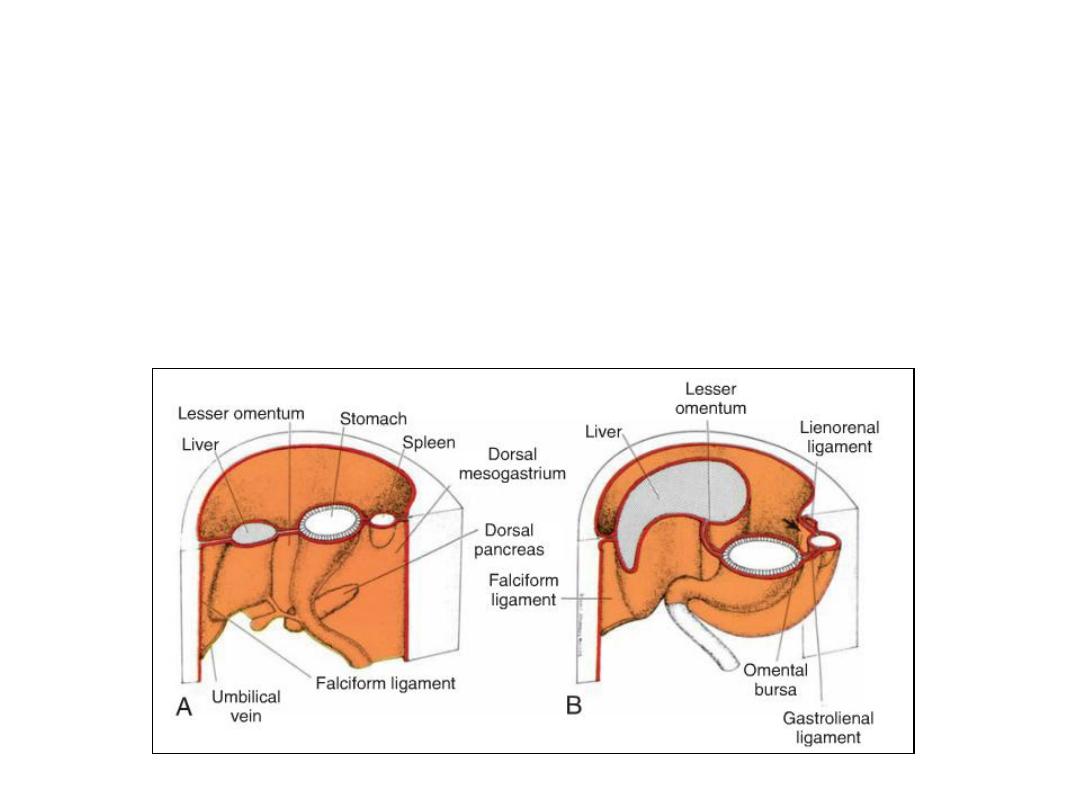

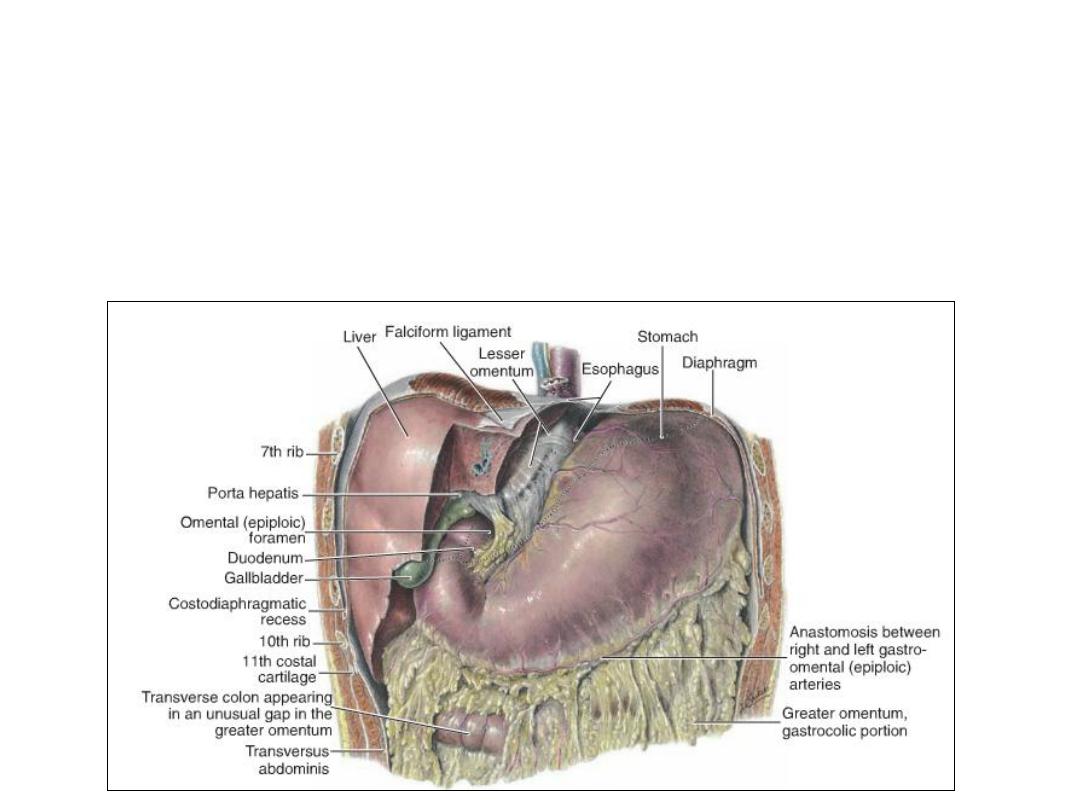

MESENTERIES

• Portions of the gut tube and its derivatives are suspended from the dorsal

and ventral body wall by mesenteries.

• Mesenteries: double layers of peritoneum that enclose an organ and

connect it to the body wall.

• Such organs are called intraperitoneal, whereas organs that lie against the

posterior body wall and are covered by peritoneum on their anterior

surface only (e.g., the kidneys) are considered retroperitoneal.

• Peritoneal ligaments are double layers of peritoneum (mesenteries) that

pass from one organ to another or from an organ to the body wall.

• Mesenteries and ligaments provide pathways for vessels, nerves, and

lymphatics to and from abdominal viscera.

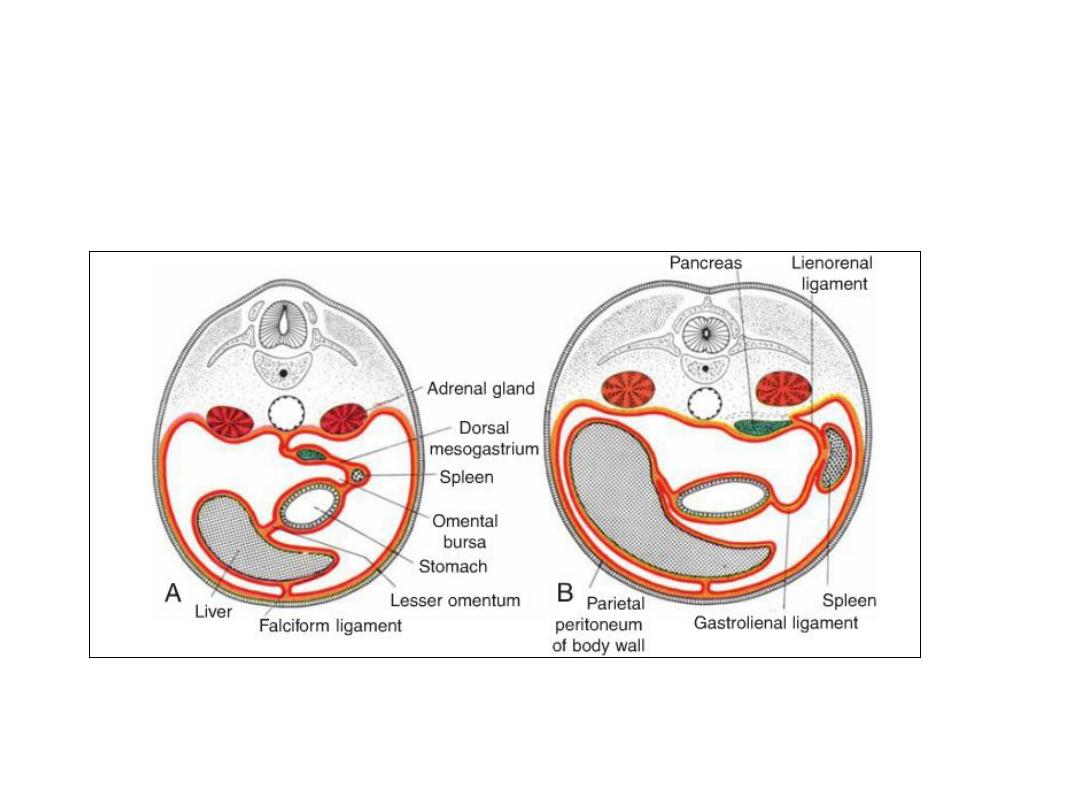

Figure: Transverse sections through embryos at various stages of development.

A. The intra-embryonic cavity, bordered by visceral and somatic layers of lateral plate mesoderm,

is in open communication with the extra embryonic cavity.

B. The intra-embryonic cavity is losing its wide connection with the extra embryonic cavity.

C. At the end of the fourth week, visceral mesoderm layers are fused in the midline and form a

double-layered membrane (dorsal mesentery) between right and left halves of the body cavity.

Ventral mesentery exists only in the region of the septum transversum (not shown).

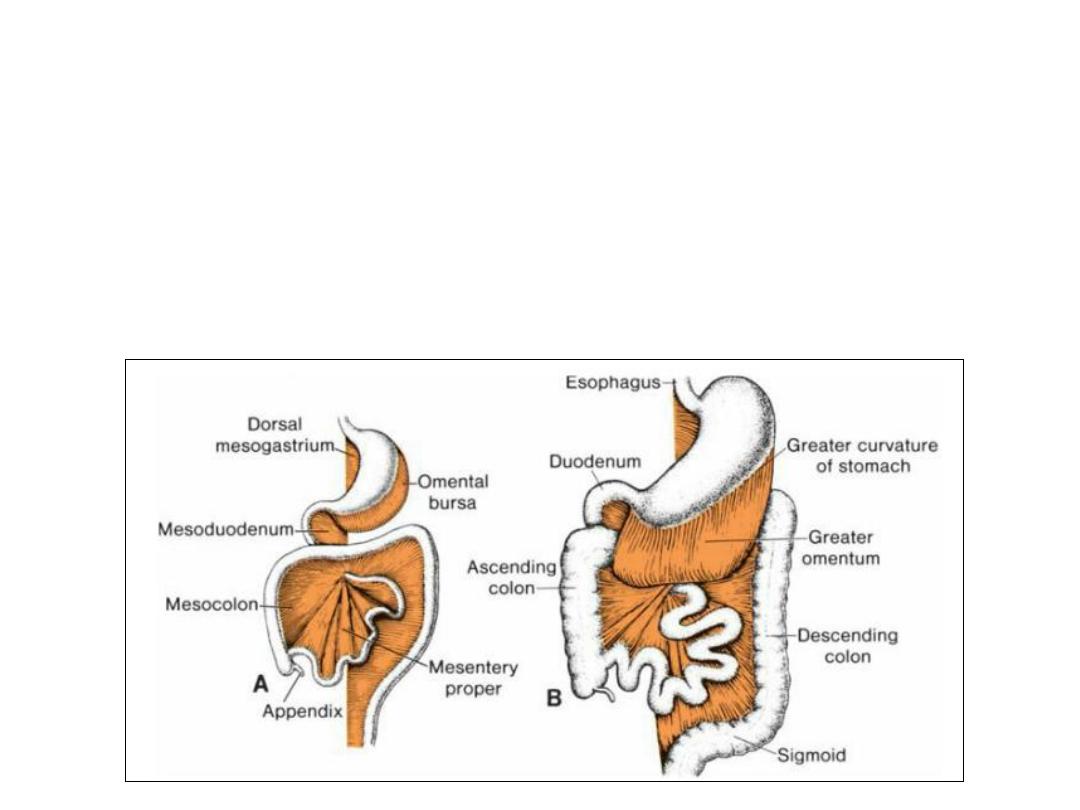

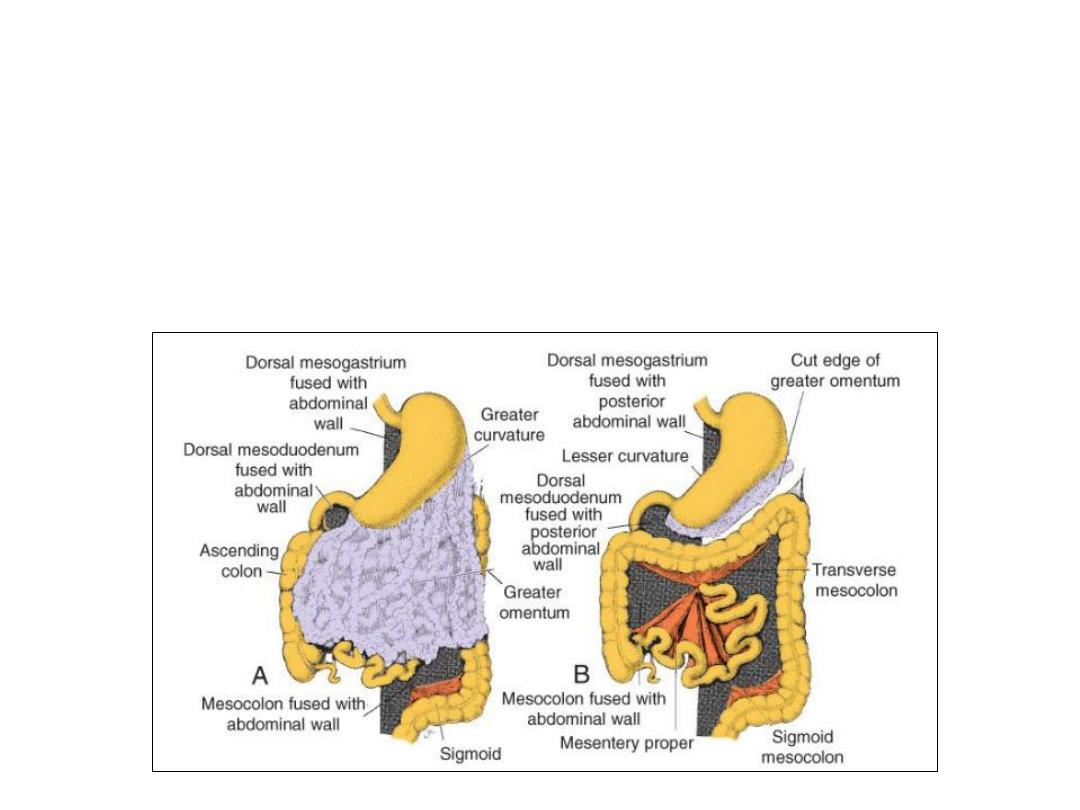

DORSAL MESENTRY

By the fifth week

THE DORSAL MESENTERY:

extends from the lower end of

the esophagus to the cloacal

region of the hindgut.

Dorsal mesogastrium or

greater omentum: In the

region of the stomach.

Dorsal mesoduodenum: In

the region of the duodenum

Mesentery proper: Dorsal

mesentery of the jejunum &

ileum.

Dorsal mesocolon: in the

region of the colon

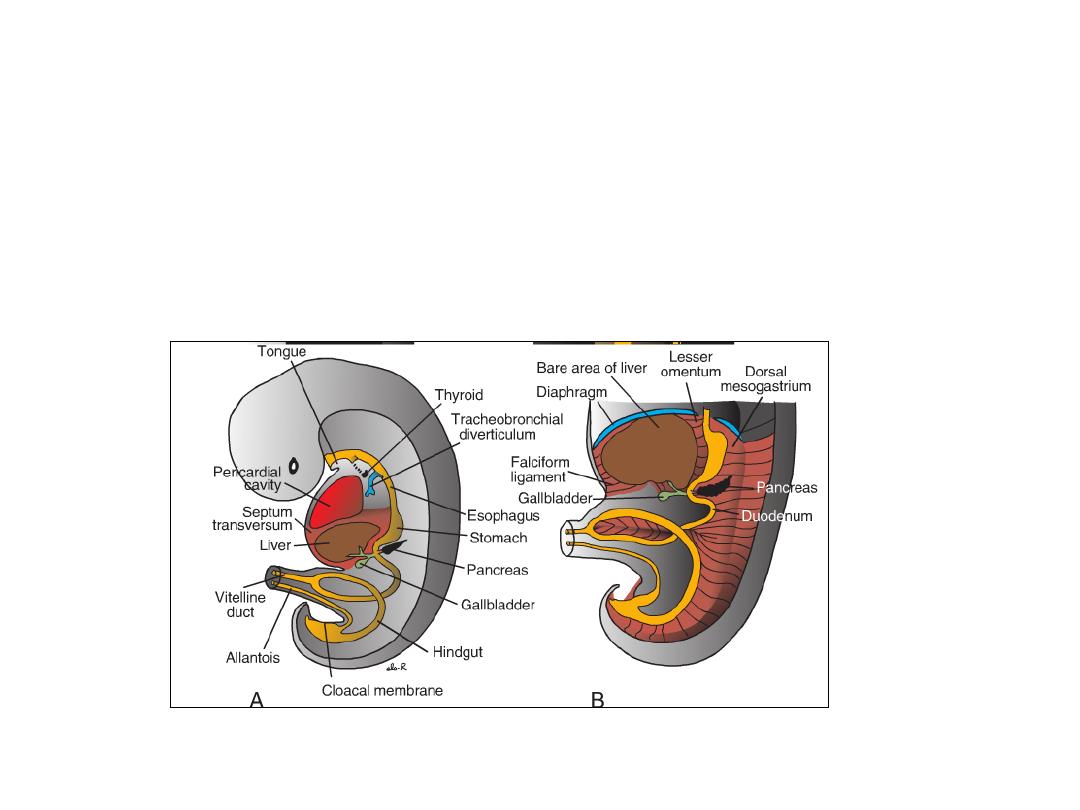

VENTRAL MESENTRY

Exists only in the region of the

terminal part of the esophagus,

the stomach, and the upper part

of the duodenum,

- Derived from the septum

transversum.

Growth of the liver into the

mesenchyme of the septum

transversum divides the ventral

mesentery into

(a) the lesser omentum,

extending from the lower portion

of the esophagus, the stomach,

and the upper portion of the

duodenum to the liver and

(b) the falciform ligament,

extending from the liver to the

ventral body wall.

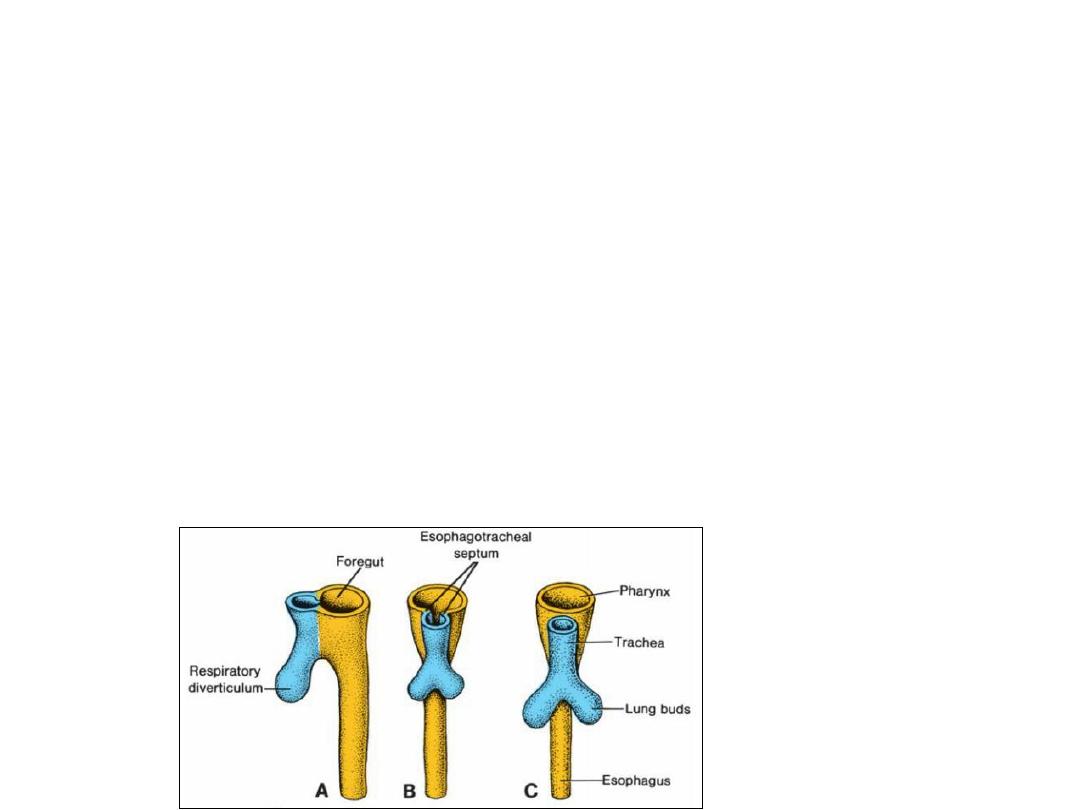

FOREGUT

•Esophagus

•When the embryo is approximately 4 weeks old, the respiratory diverticulum (lung bud)

appears at the ventral wall of the foregut at the border with the pharyngeal gut.

•The tracheo-esophageal septum gradually partitions this diverticulum from the dorsal part

of the foregut.

• In this manner, the foregut divides into a ventral portion, the respiratory primordium, and

a dorsal portion, the esophagus.

•At first, the esophagus is short, but with descent of the heart and lungs, it lengthens

rapidly.

•The muscular coat, which is formed by surrounding splanchnic mesenchyme, is striated in

its upper two thirds and innervated by the vagus; the muscle coat is smooth in the lower

third and is innervated by the splanchnic plexus.

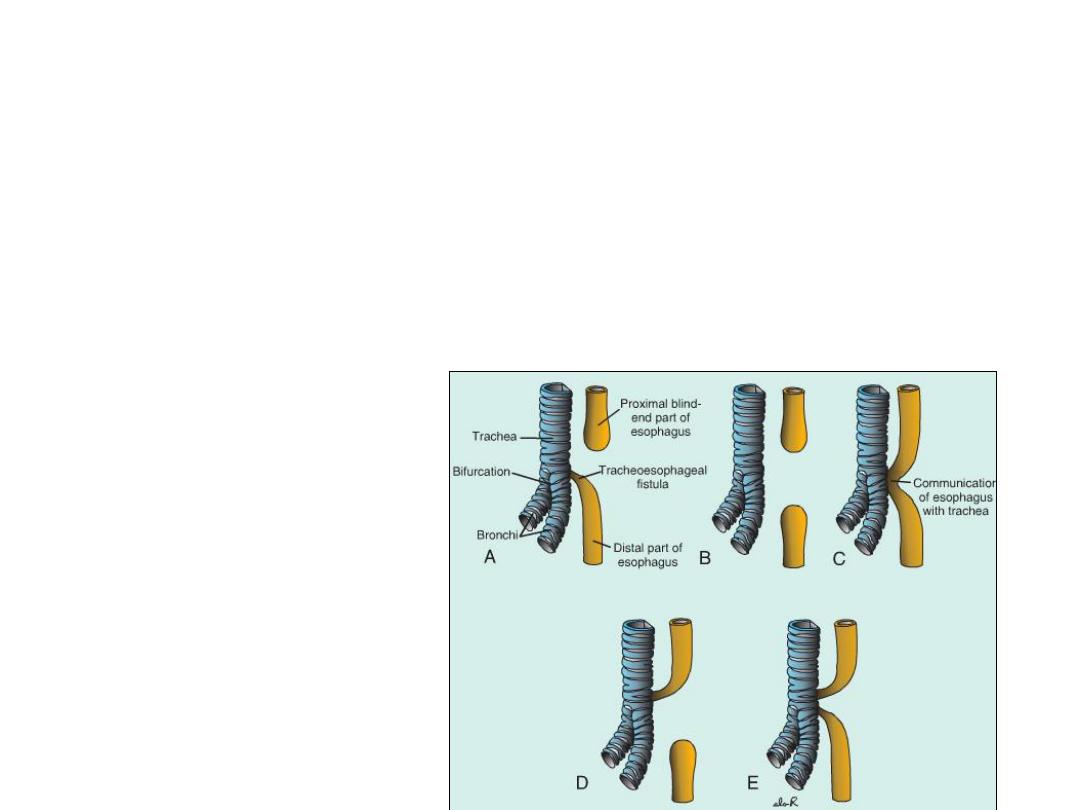

Figure: Variations of

esophageal atresia

and/or tracheo-

esophageal fistula in

order of their frequency

of appearance: A,90%;

B,4%; C,4%; D,1%; and

E,1%.

Clinical Correlates

Esophageal Abnormalities

Esophageal atresia and/or tracheoesophageal fistula results either from

spontaneous posterior deviation of the tracheoesophageal septum or from some

mechanical factor pushing the dorsal wall of the foregut anteriorly.

In its most common form, the proximal part of the esophagus ends as a blind

sac, and the distal part is connected to the trachea by a narrow canal just above

the bifurcation.

Atresia of the esophagus prevents normal passage of amniotic fluid into the

intestinal tract, resulting in accumulation of excess fluid in the amniotic sac

(polyhydramnios) .

• The lumen of the esophagus may narrow, producing esophageal stenosis,

usually in the lower third. Stenosis may be caused by incomplete

recanalization, vascular abnormalities, or accidents that compromise

blood flow.

• Occasionally, the esophagus fails to lengthen sufficiently, and the stomach

is pulled up into the esophageal hiatus through the diaphragm. The result

is a congenital hiatal hernia.

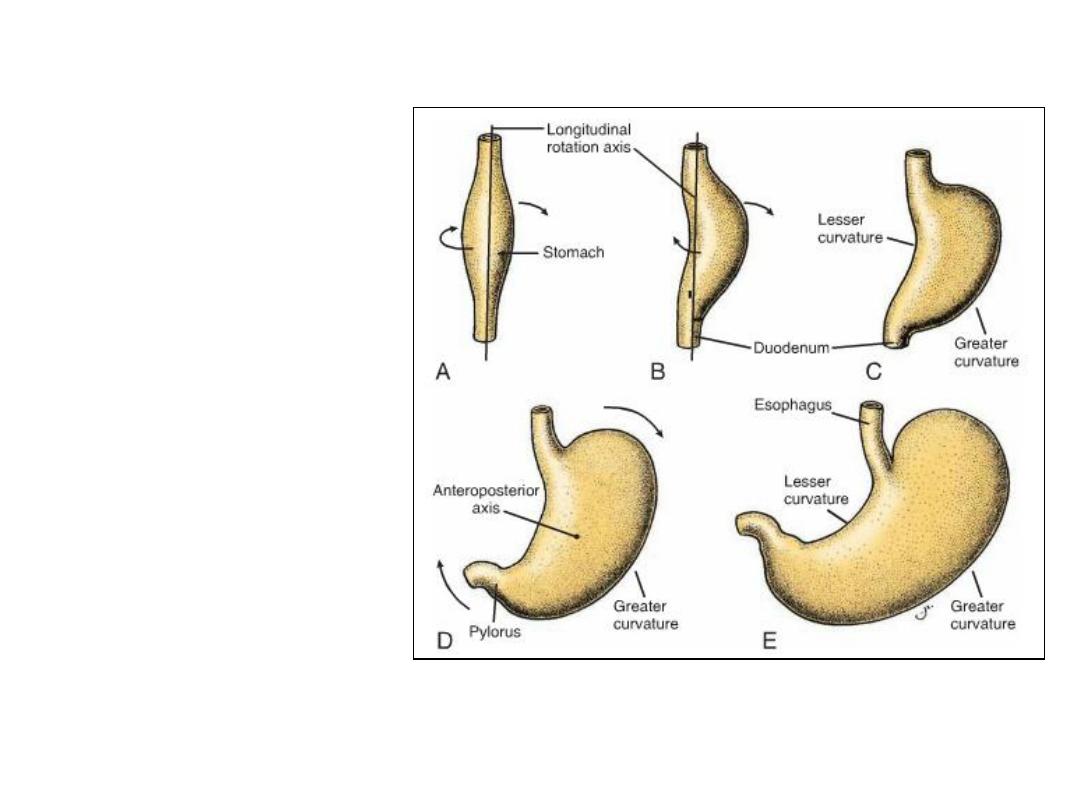

Stomach rotation

•The stomach appears as a fusiform

dilation of the foregut in the

fourth week of development.

•The stomach rotates 90°clockwise

around its longitudinal axis,

causing its left side to face

anteriorly and its right side to face

posteriorly.

•Hence, the left vagus nerve,

initially innervating the left side of

the stomach, now innervates the

anterior wall; similarly, the right

nerve innervates the posterior

wall.

•During this rotation, the original

posterior wall of the stomach

grows faster than the anterior

portion, forming the greater and

lesser curvatures.

Stomach rotation

•The cephalic and caudal

ends of the stomach

originally lie in the midline,

but during further growth,

the stomach rotates

around an anteroposterior

axis, such that the caudal

or pyloric part moves to

the right and upward, and

the cephalic or cardiac

portion moves to the left

and slightly downward.

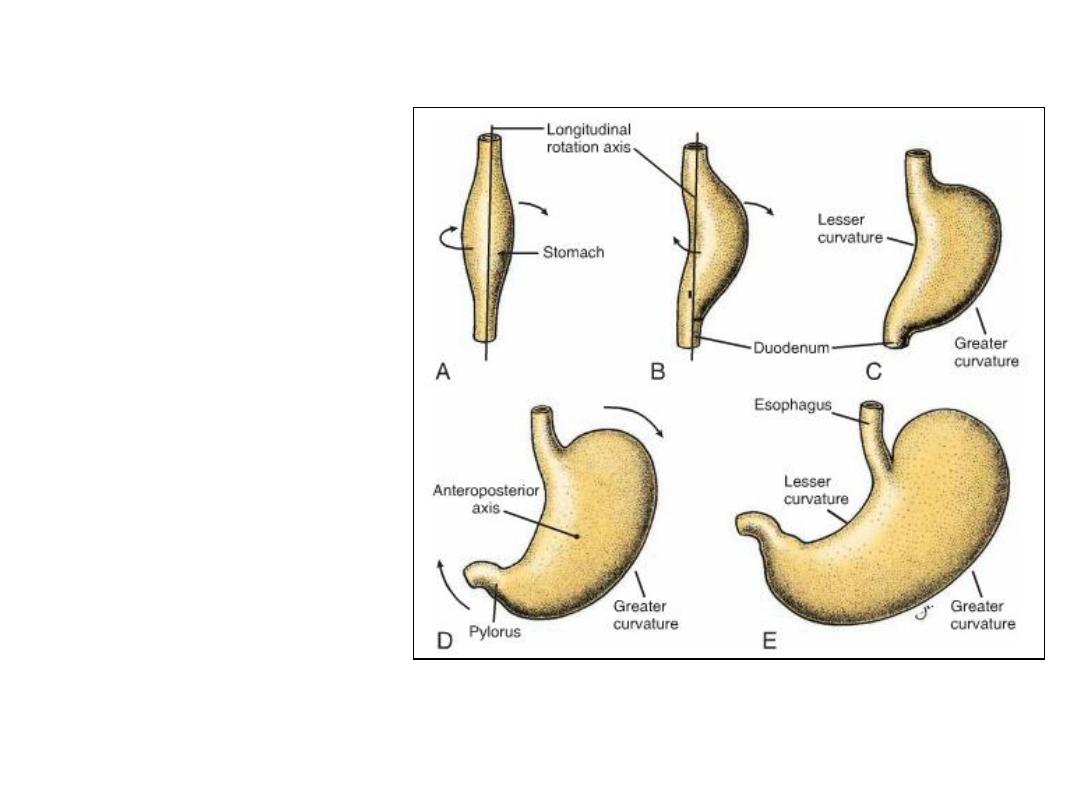

Formation of omental bursa (lesser sac)

• Rotation about the longitudinal axis pulls the dorsal mesogastrium to the

left, creating a space behind the stomach called the omental bursa (lesser

peritoneal sac).

• This rotation also pulls the ventral mesogastrium to the right.

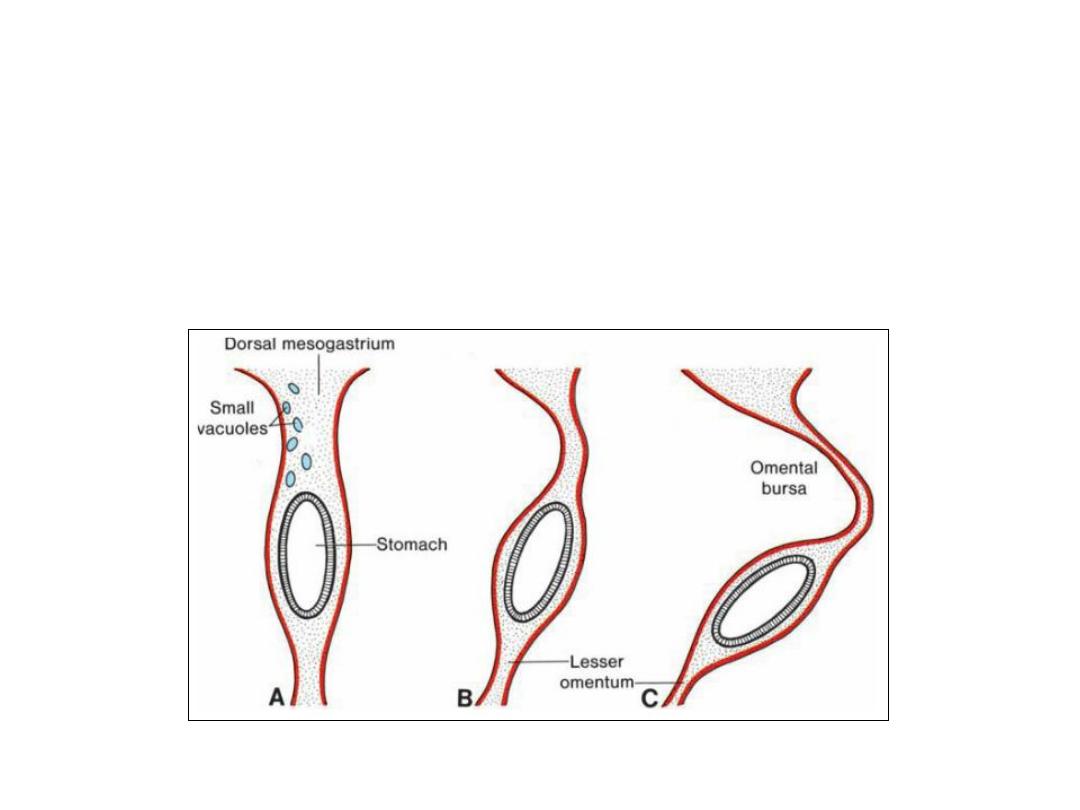

Spleen development

• The spleen primordium appears as a mesodermal proliferation between

the two leaves of the dorsal mesogastrium.

• With continued rotation of the stomach, the spleen, which remains

intraperitoneal, is then connected to the body wall in the region of the

left kidney by the lienorenal ligament and to the stomach by the

gastrolienal ligament.

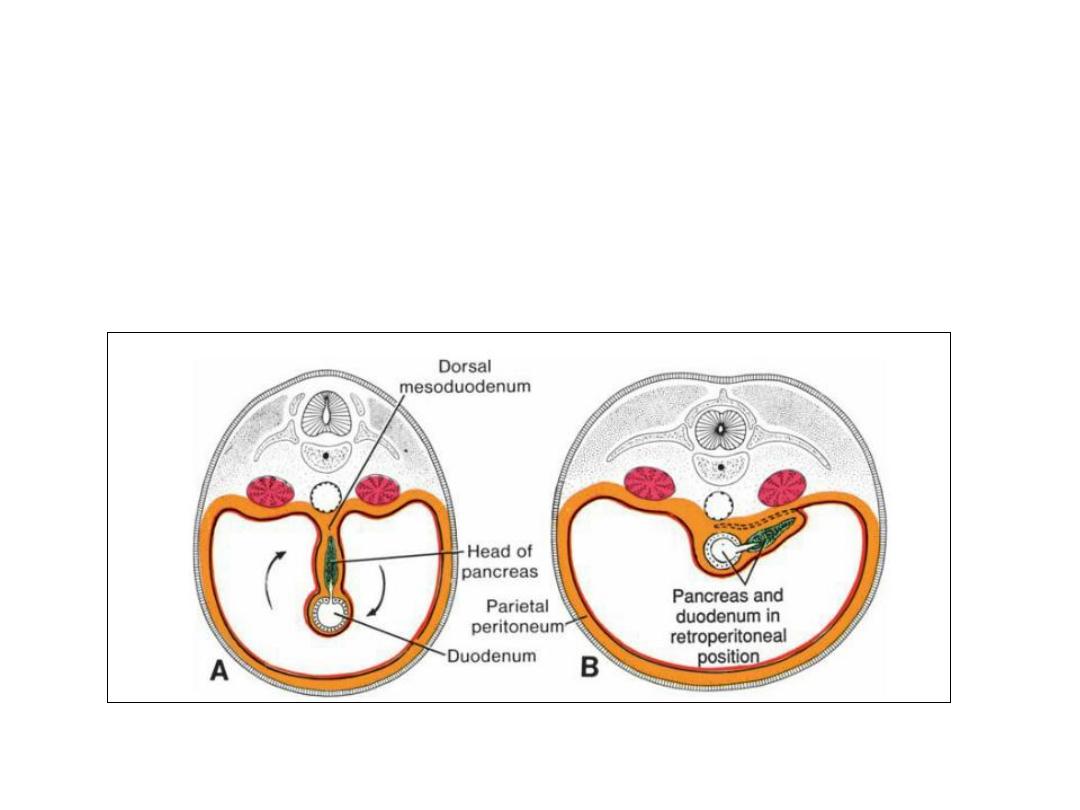

Organs, such as the pancreas, that are originally covered by

peritoneum, but later fuse with the posterior body wall to become

retroperitoneal, are said to be secondarily retroperitoneal.

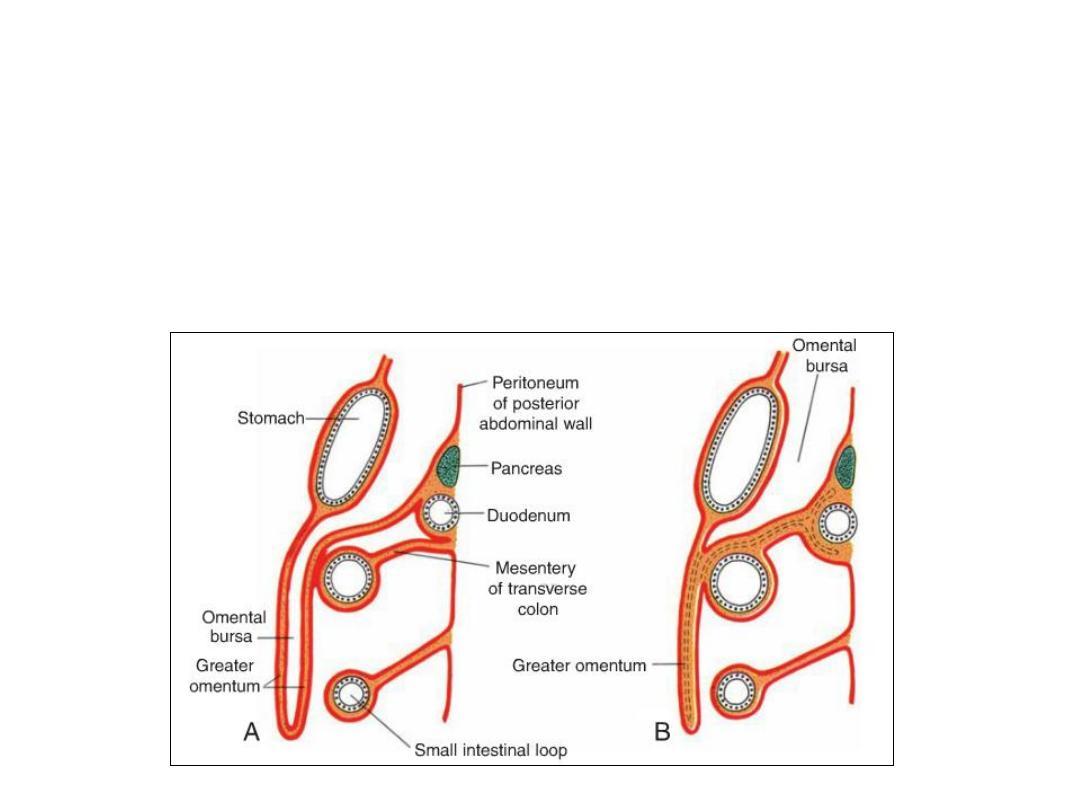

Formation of greater omentum

• As a result of rotation of the stomach about its anteroposterior axis, the

dorsal mesogastrium bulges down. It continues to grow down and forms a

double-layered sac extending over the transverse colon and small

intestinal loops like an apron. This double-leafed apron is the greater

omentum; later, its layers fuse to form a single sheet hanging from the

greater curvature of the stomach.

Formation of greater omentum

• The posterior layer of the greateromentum also fuses with the mesentery

of the transverse colon.

The lesser omentum and falciform ligament form from the ventral mesogastrium,

which itself is derived from mesoderm of the septum transversum.

• The free margin of the falciform ligament contains the umbilical vein, which

is obliterated after birth to form the round ligament of the liver (ligamentum

teres hepatis) .

• The free margin of the lsser omentum connecting the duodenum and liver

(hepatoduodenal ligament) contains the bile duct, portal vein, and hepatic

artery (portaltriad) This free margin also forms the roof of the epiploic

foramen of Winslow, which is the opening connecting the omental bursa

(lesser sac) with the rest of the peritoneal cavity (greater sac).

Clinical Correlates

• Stomach Abnormalities

• Pyloric stenosis: occurs when the circular and, to a lesser degree, the

longitudinal musculature of the stomach in the region of the pylorus

hypertrophies. One of the most common abnor-malities of the stomach in

infants, pyloric steno-sis is believed to develop during fetal life. There is an

extreme narrowing of the pyloric lumen, and the passage of food is

obstructed, resulting in severe vomiting. In a few cases, the pylorus is

atretic.

Duodenum

The terminal part of the foregut and the cephalic part of the midgut

form the duodenum. The junction of the two parts is directly distal to

the origin of the liver bud.

Duodenum

As the stomach rotates, the duodenum takes on the form of a C-

shaped loop and rotates to the right. This rotation, together with rapid

growth of the head of the pancreas, swings the duodenum from its

initial midline position to the right side of the abdominal cavity .

Duodenum

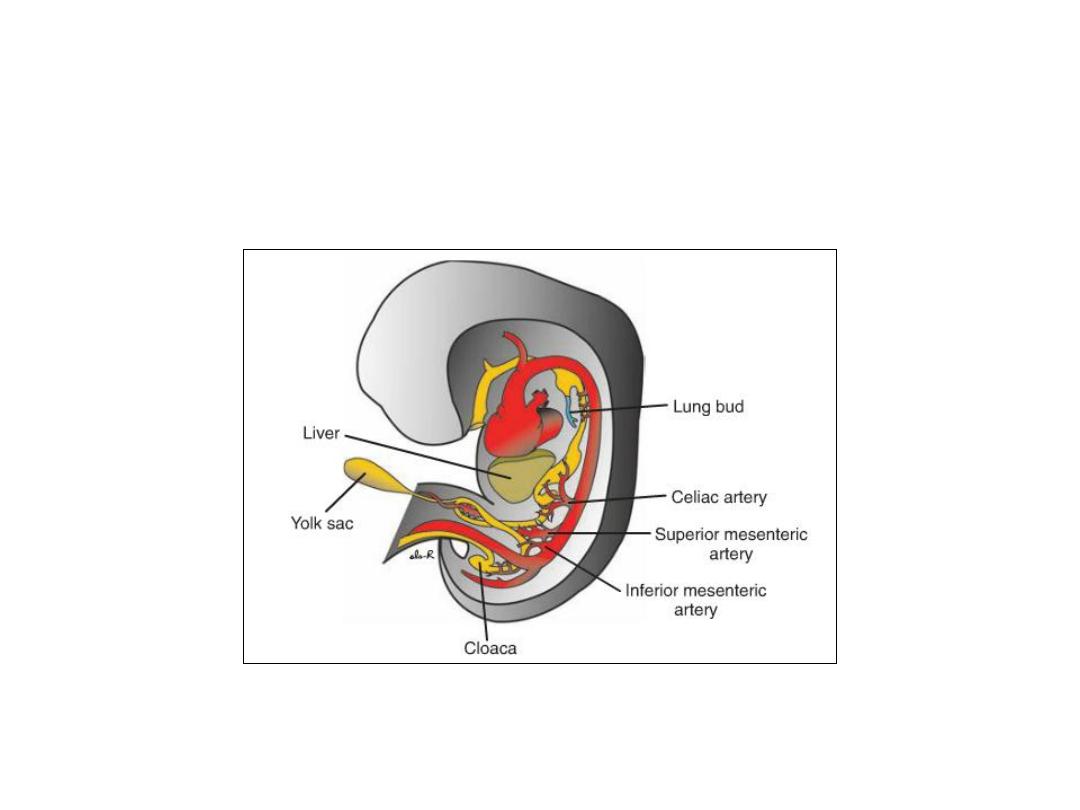

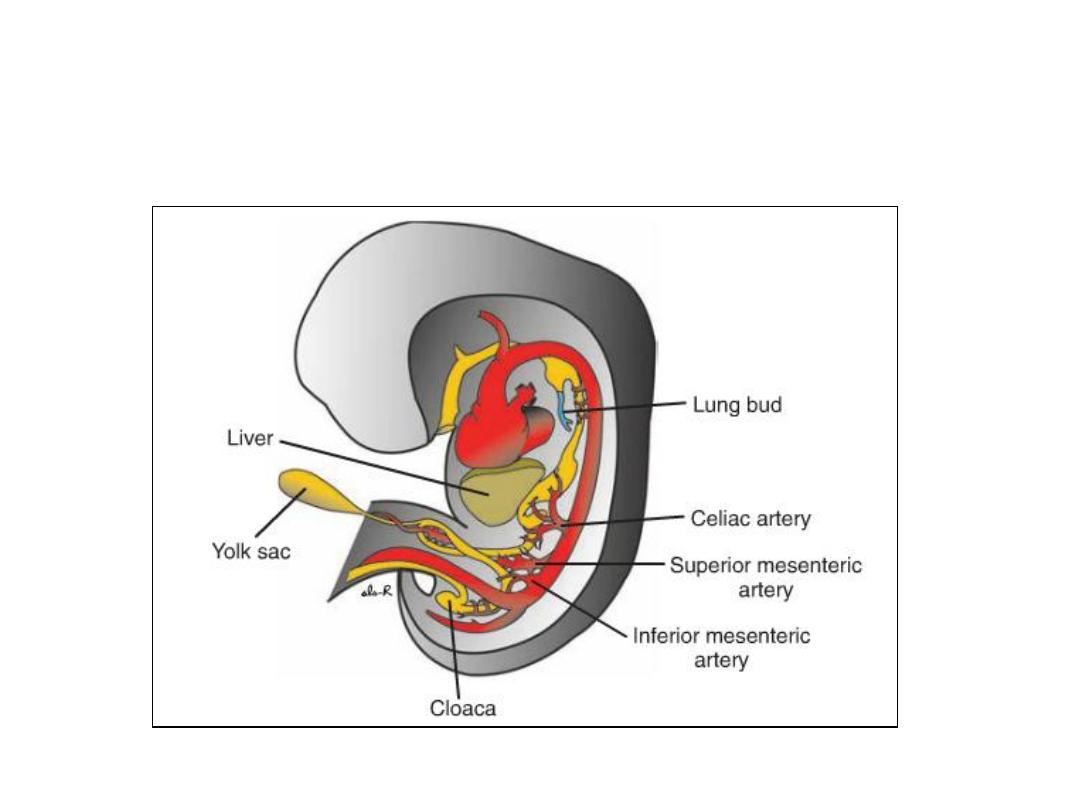

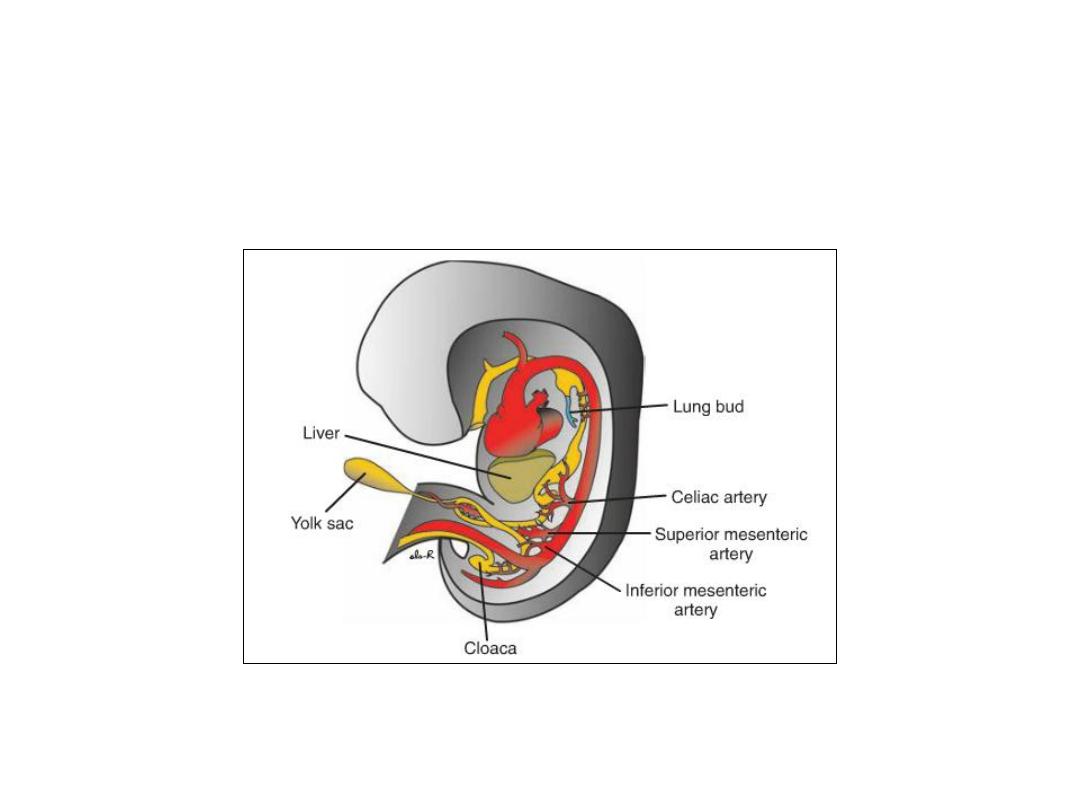

• Since the foregut is supplied by the celiac artery and the midgut is

supplied by the superior mesenteric artery, the duodenum is supplied by

branches of both arteries.

Figure: Embryo during the sixth week of development, showing blood

supply to the segments of the gut. The superior mesenteric artery supplies

the midgut. The celiac and inferior mesenteric arteries supply the foregut

and hindgut, respectively.

During the second month, the lumen of the duodenum is obliterated

by proliferation of cells in its walls. However, the lumen is recanalized

shortly thereafter.

Liver & gall bladder

•

The liver primordium appears in the middle of the third week as an outgrowth of the

endodermal epithelium at the distal end of the foregut.

•

This outgrowth, the hepatic diverticulum, or liver bud, consists of rapidly proliferating cells

that penetrate the septum transversum, that is, the mesodermal plate between the

pericardial cavity and the stalk of the yolk sac.

•

While hepatic cells continue to penetrate the septum, the connection between the hepatic

diverticulum and the foregut (duodenum) narrows, forming the bile duct.

•

A small ventral outgrowth is formed by the bile duct, and this outgrowth gives rise to the gall

bladder and the cystic duct.

• During further development, epithelial liver cords intermingle with the

vitelline and umbilical veins, which form hepatic sinusoids.

• Liver cords differentiate into the parenchyma (liver cells) and form the

lining of the biliary ducts (endoderm).

• Hematopoietic cells, Kupffer cells, and connective tissue cells are derived

from mesoderm of the septum transversum.

• In this region, the liver remains in contact with the rest of the original

septum transversum. This portion of the septum, which consists of

densely packed mesoderm, will form the central tendon of the

diaphragm.

• The surface of the liver that is in contact with the future diaphragm is

never covered by peritoneum; it is the bare area of the liver.

• Hematopoietic function: Large nests of proliferating cells, which produce

red and white blood cells, lie between hepatic cells and walls of the

vessels. This activity gradually subsides during the last 2 months of

intrauterine life, and only small hematopoietic islands remain at birth.

• Another important function of the liver begins at approximately the 12th

week, when bile is formed by hepatic cells.

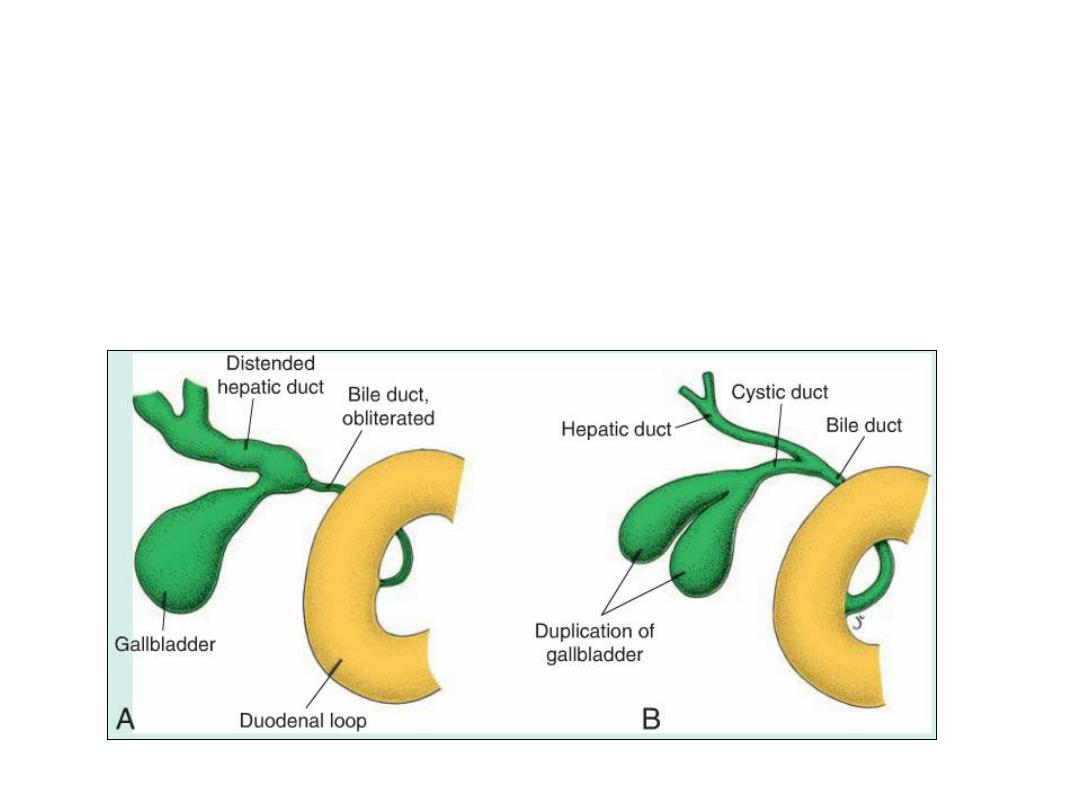

Clinical correlates

• Accessory hepatic ducts

• Duplication of the gallbladder

• Extrahepatic biliary atresia,

• Intrahepatic biliary duct atresia and hypoplasia.

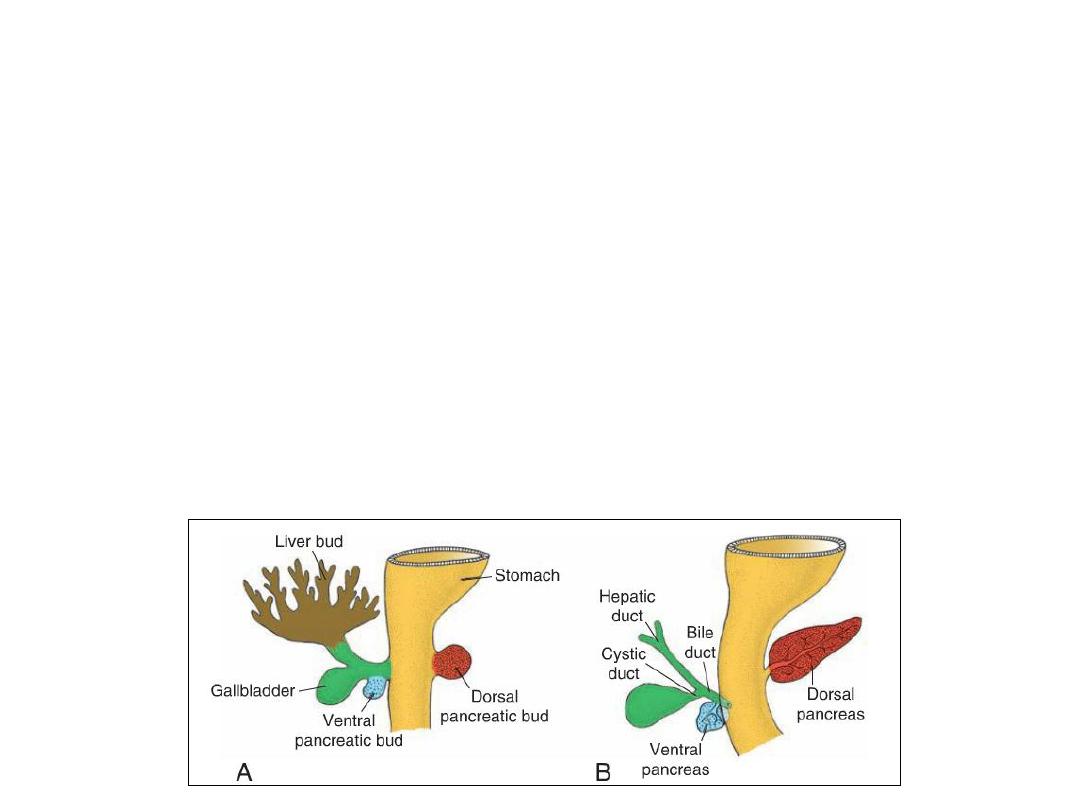

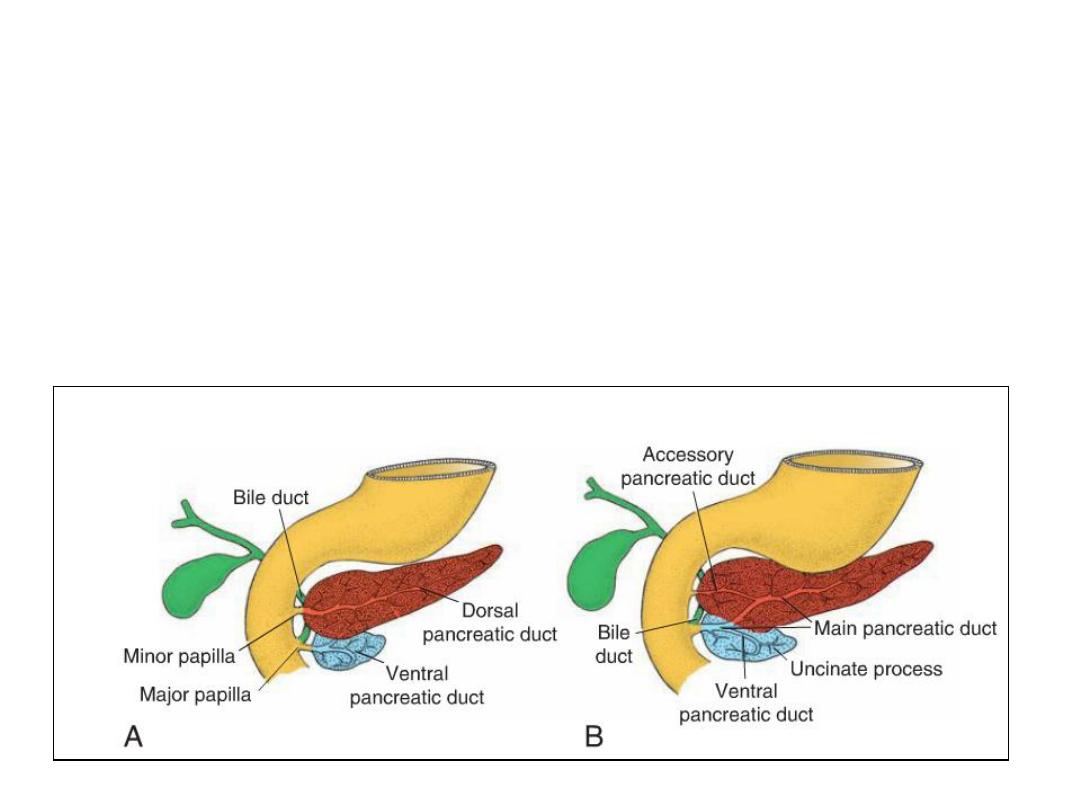

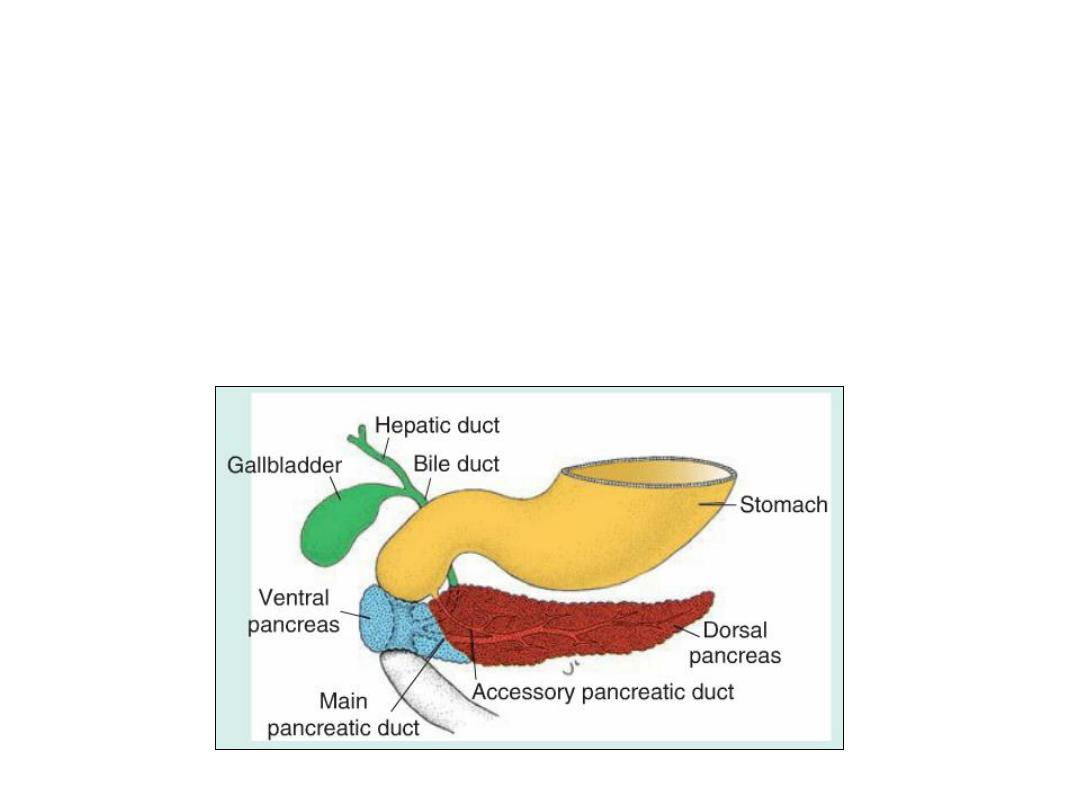

PANCREAS

•

The pancreas is formed by two buds, dorsal and ventral, originating from the

endodermal lining of the duodenum.

•

Whereas the dorsal pancreatic bud is in the dorsal mesentery, the ventral

pancreatic bud is close to the bile duct.

•

When the duodenum rotates to the right and becomes C-shaped, the ventral

pancreatic bud moves dorsally in a manner similar to the shifting of the entrance

of the bile duct.

•

Finally, the ventral bud comes to lie immediately below and behind the dorsal bud.

•

Later, the parenchyma and the duct systems of the dorsal and ventral pancreatic

buds fuse.

•

The ventral bud forms the uncinate process and inferior part of the head of the

pancreas. The remaining part of the gland is derived from the dorsal bud.

• The main pancreatic duct (of Wirsung) is formed by the distal part of the

dorsal pancreatic duct and the entire ventral pancreatic duct.

• The proximal part of the dorsal pancreatic duct either is obliterated or

persists as a small channel, the accessory pancreatic duct (of Santorini).

• The main pancreatic duct, together with the bile duct, enters the

duodenum at the site of the major papilla; the entrance of the accessory

duct (when present) is at the site of the minor papilla.

• In about 10% of cases, the duct system fails to fuse, and the original

double system persists.

Endocrine Pancreas

• In the third month of fetal life, pancreatic islets (of Langerhans ) develop

from the parenchymatous pancreatic tissue and scatter throughout the

pancreas.

• Insulin secretion begins at approximately the fifth month. Glucagon and

somatostatin-secreting cells also develop from parenchymal cells.

• Visceral mesoderm surrounding the pancreatic buds forms the pancreatic

connective tissue.

Clinical Correlates

• Annular pancreas

• Accessory pancreatic tissue

Ch. 15 – Part 2

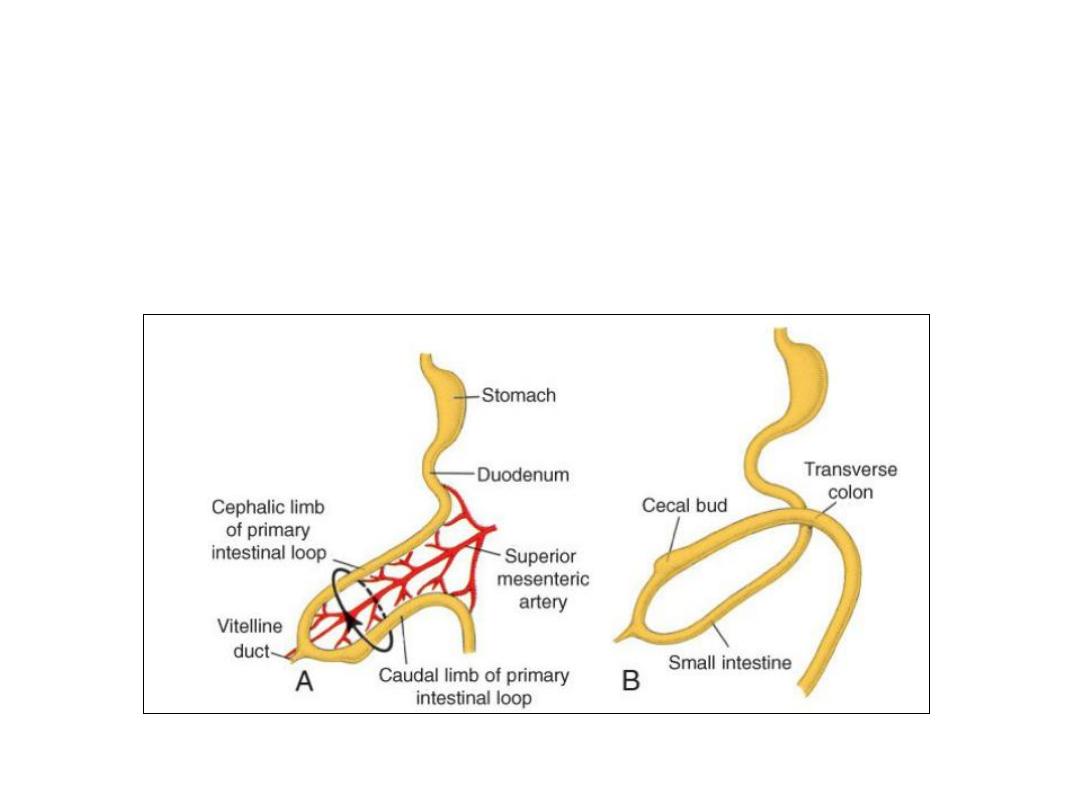

MIDGUT

• In the 5-week embryo, the midgut is suspended from the dorsal

abdominal wall by a short mesentery and communicates with the yolk sac

by way of the vitelline duct or yolk stalk .

• In the adult, the midgut begins immediately distal to the entrance of the

bile duct into the duodenum and terminates at the junction of the

proximal two thirds of the transverse colon with the distal third.

• Over its entire length, the midgut is supplied by the superior mesenteric

artery.

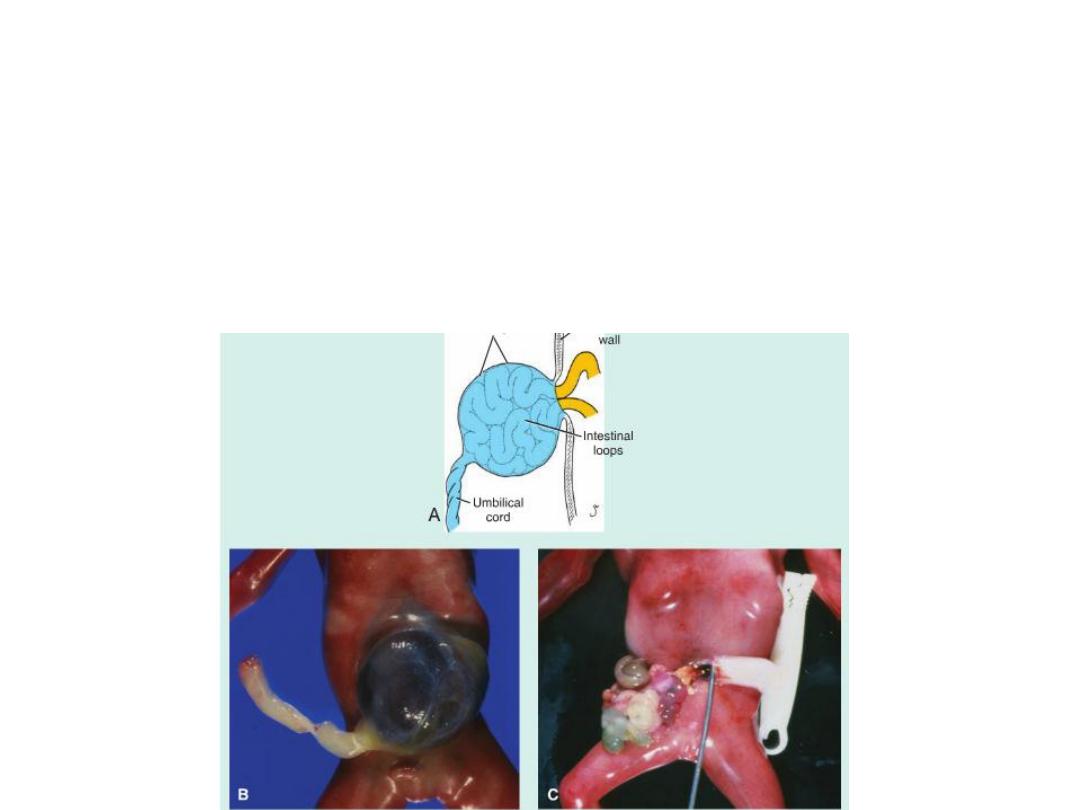

Physiological Herniation

• Development of the primary intestinal loop is characterized by rapid

elongation.

• As a result of the rapid growth and expansion of the liver, the abdominal

cavity temporarily becomes too small to contain all the intestinal loops,

and they enter the extraembryonic cavity in the umbilical cord during the

sixth week of development.

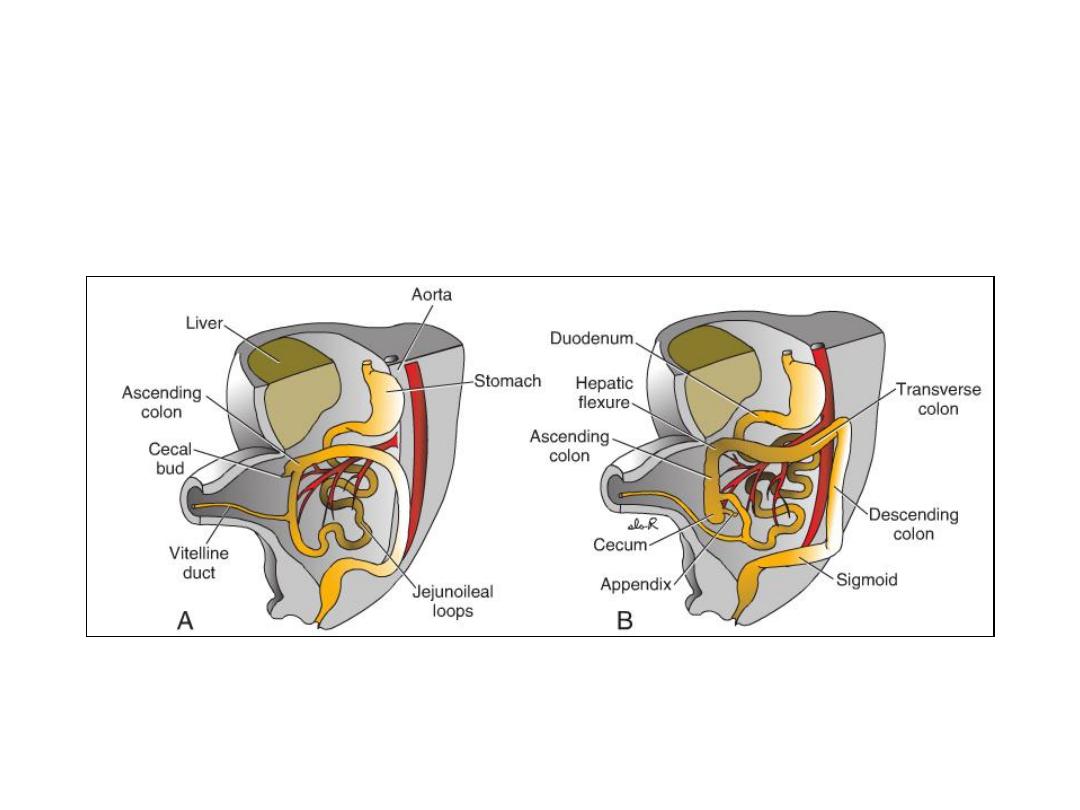

Rotation of the Midgut

• Coincident with growth in length, the primary intestinal loop rotates

around an axis formed by the superior mesenteric artery.

• This rotation is counter clockwise, and it amounts to approximately

270°when it is complete.

Retraction of Herniated Loops

• During the 10th week, herniated intestinal loops begin to return to the

abdominal cavity.

Mesenteries of the Intestinal Loops

• With retraction of the intestinal loop, the dorsal mesentery twists

around the origin of the superior mesenteric artery.

• After retraction, the ascending and descending colons are permanently

anchored to the posterior abdominal wall in a retroperitoneal position.

• The appendix, lower end of cecum, transverse colon and sigmoid colon

remain intraperitoneal.

Abnormalities of the Mesenteries

• Mobile cecum: Persistence of a portion of the mesocolon (in the

ascending colon).

• Volvulus: In the most extreme form, the mesentery of the ascending colon

failsto fuse with the posterior body wall, and allows abnormal movements

of the gut.

• Retrocolic hernia: entrapment of portions of the small intestine behind

the mesocolon.

Body Wall Defects: Omphalocele, Gastroschisis.

A.Omphalocele showing failure of the intestinal loops to return to the

body cavity after physiologi-calherniation. The herniated loops are

covered by amnion. B.Omphalocele in a newborn.

C.Newborn with gastroschi-sis. Loops of bowel extend through a

closure defect in the ventral body wall and are not covered by

amnion.

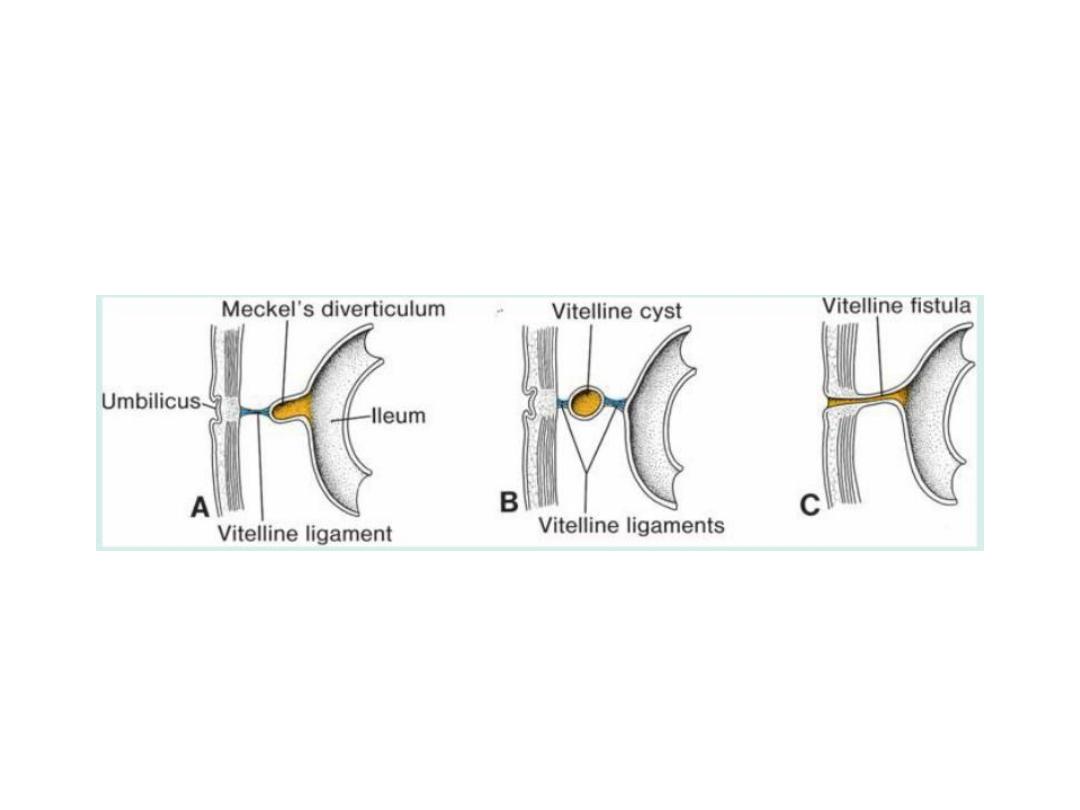

Vitelline Duct Abnormalities

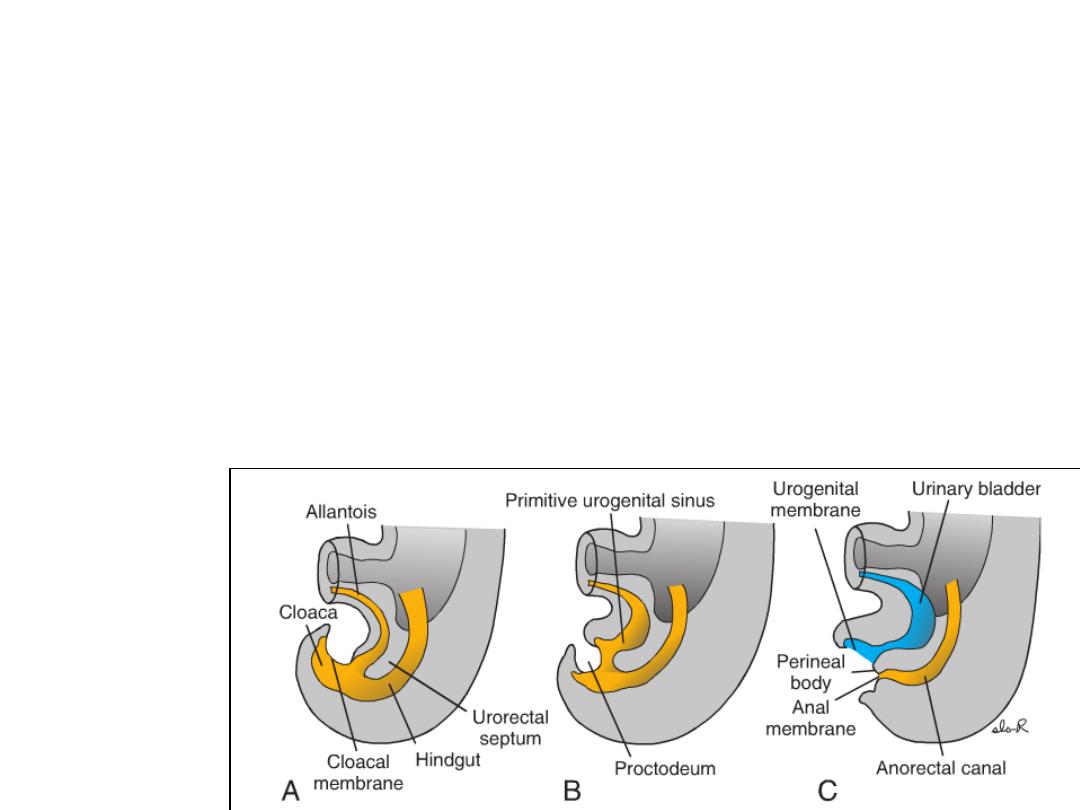

HINDGUT

• The hindgut gives rise to the distal third of the transverse colon, the

descending colon, the sigmoid, the rectum, and the upper part of the anal

canal.

• The terminal portion of the hindgut enters into the posterior region of the

cloaca, the primitive anorectal canal;

• The allantois enters into the anterior portion, the primitive urogenital sinus

• The cloaca itself is an endoderm-lined cavity covered at its ventral

boundary by surface ectoderm. This boundary between the endoderm

and the ectoderm forms the cloacal membrane.

• A layer of mesoderm, the urorectal septum, separates the region

between the allantois and hindgut.

• As the embryo grows and caudal folding continues, the tip of the urorectal

septum comes to lie close to the cloacal membrane.

• At the end of the seventh week, the cloacal membrane ruptures, creating the

anal opening for the hindgut and a ventral opening for the urogenital sinus.

• Between the two, the tip of the urorectal septum forms the perineal body.

• The upper part (two-thirds) of the anal canal is derived from endoderm of the

hindgut; the lower part (one-third) is derived from ectoderm around the

Proctodeum.

• Degeneration of the cloacal membrane (now called the Anal membrane )

establishes continuity between the upper and lower parts of the anal canal.

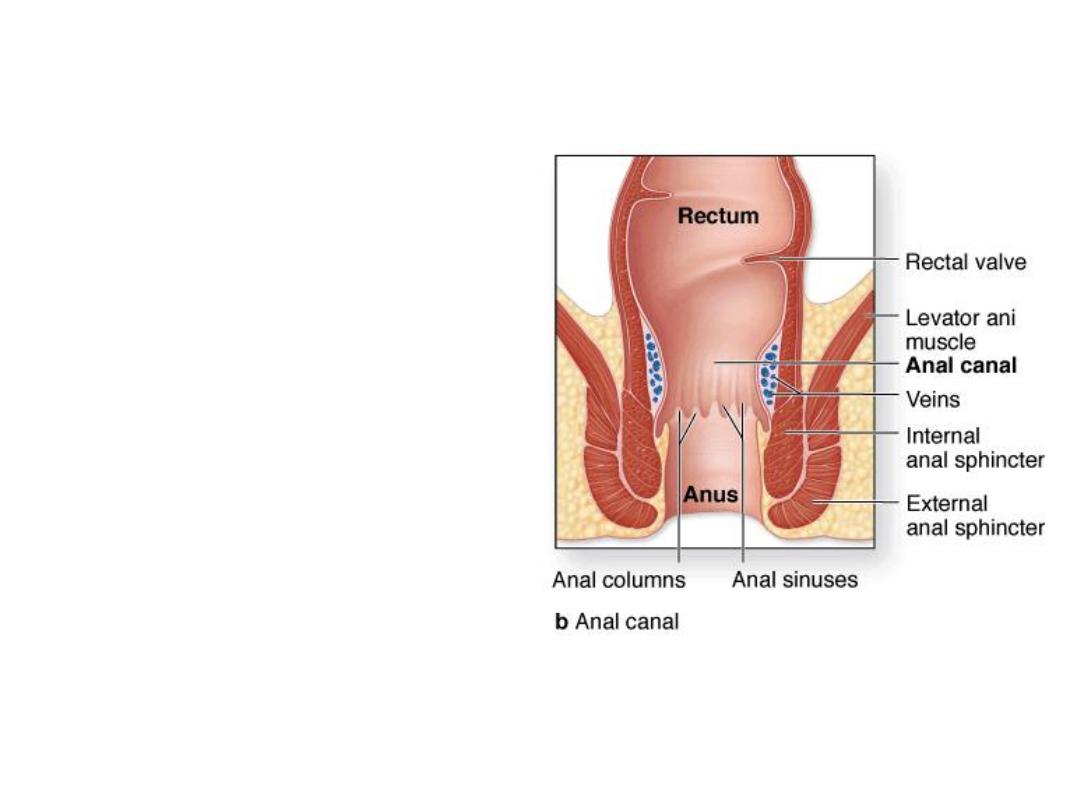

Since the caudal part of the anal canal

originates from ectoderm, it is supplied by

the inferior rectal arteries, branches of

the internal pudendal arteries.

However, the cranial part of the anal

canal originates from endoderm and is

therefore supplied by the superior rectal

artery, a continuation of the inferior

mesenteric artery, the artery of the

hindgut.

The junction between the endodermal and

ectodermal regions of the anal canal is

delineated by the pectinate line, just

below the anal columns.

At this line, the epithelium changes from

columnar to stratified squamous

epithelium.

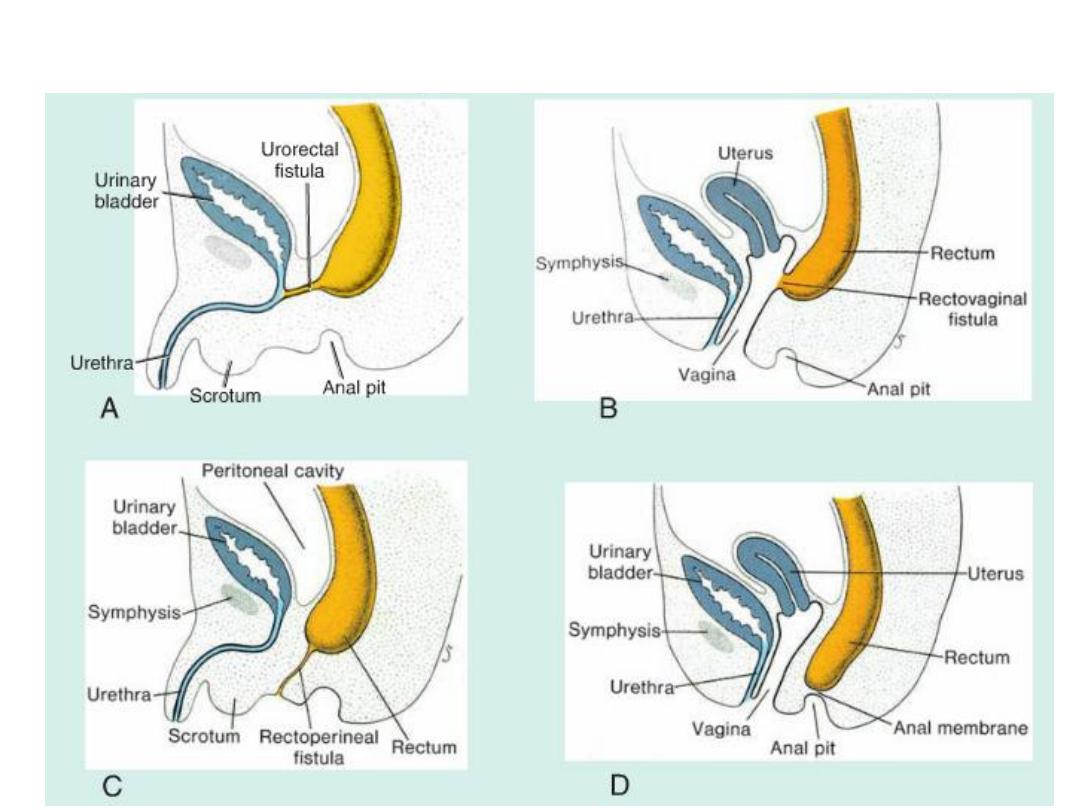

Hindgut Abnormalities

Congenital megacolon

• Is due to an absence of parasympathetic ganglia in the bowel wall

(aganglionic megacolon or hirschsprung disease ).

• These ganglia are derived from neural crest cells that migrate from the

neural folds to the wall of the bowel.

• Mutations in the RET gene, a tyrosine kinase receptor involved in crest

cell migration, can result in congenital megacolon.