List of Contents

دكتورة وفاء

Lab 1 – Blood Typing

Lab 2 – Bleeding Time

Lab 3 – Blood clotting tests

Lab 4 – RBC Count

Lab 5 – WBC Count

Lab 6 – Hemoglobin

Lab 7 – ESR (Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate)

Lab 8 – Measurement of Hormone Concentration in the Blood

دكتور حيدر

Lab 9 – Arterial Pulse

Lab 10 – Body Temperature

Lab 11 – Electrical Potential of the Heart

Lab 12 – Exercise ESG Test

دكتور طالب

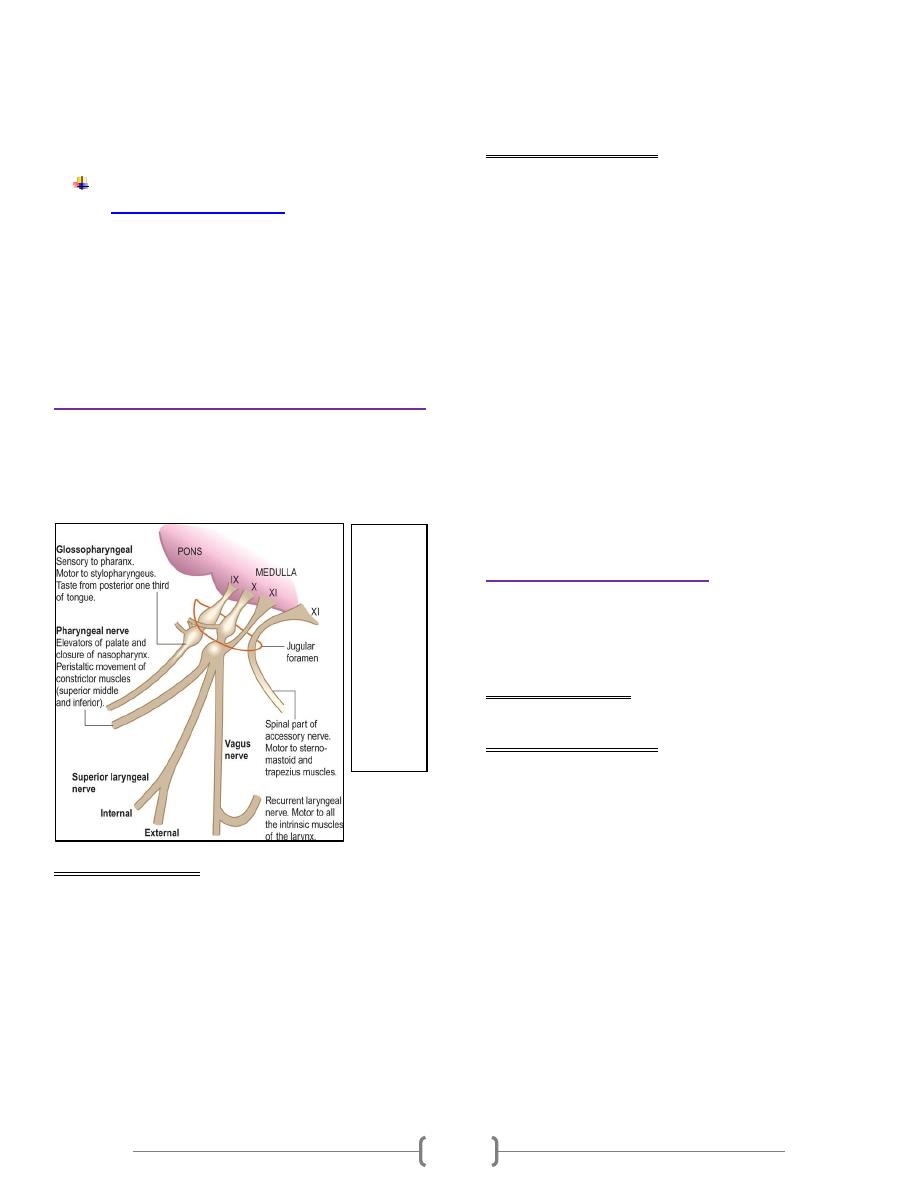

Lab 31 – Examination of Cranial nerves

(Except II, III, IV, and VI)

دكتور احمد الشيباني

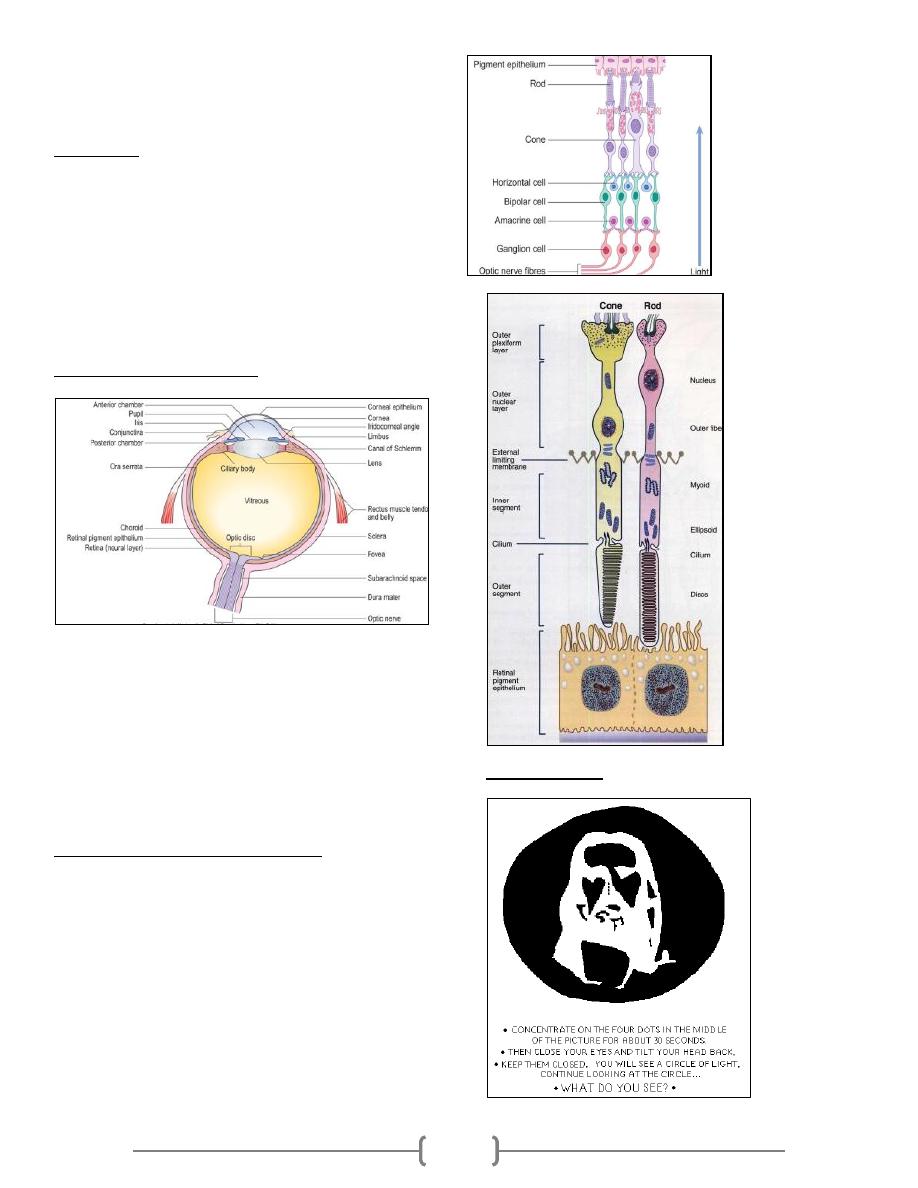

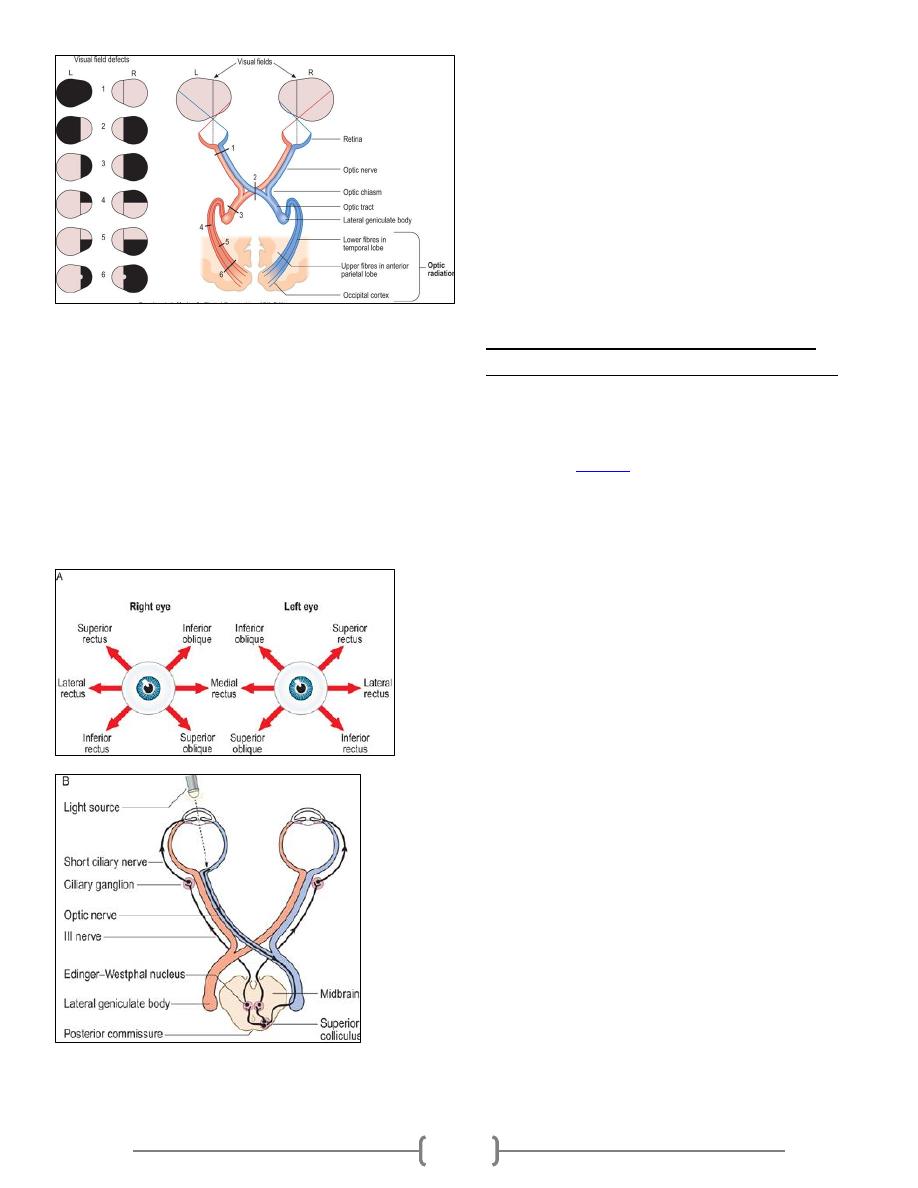

Lab 34 – Ocular Physiology

Lab 35 – Color Vision

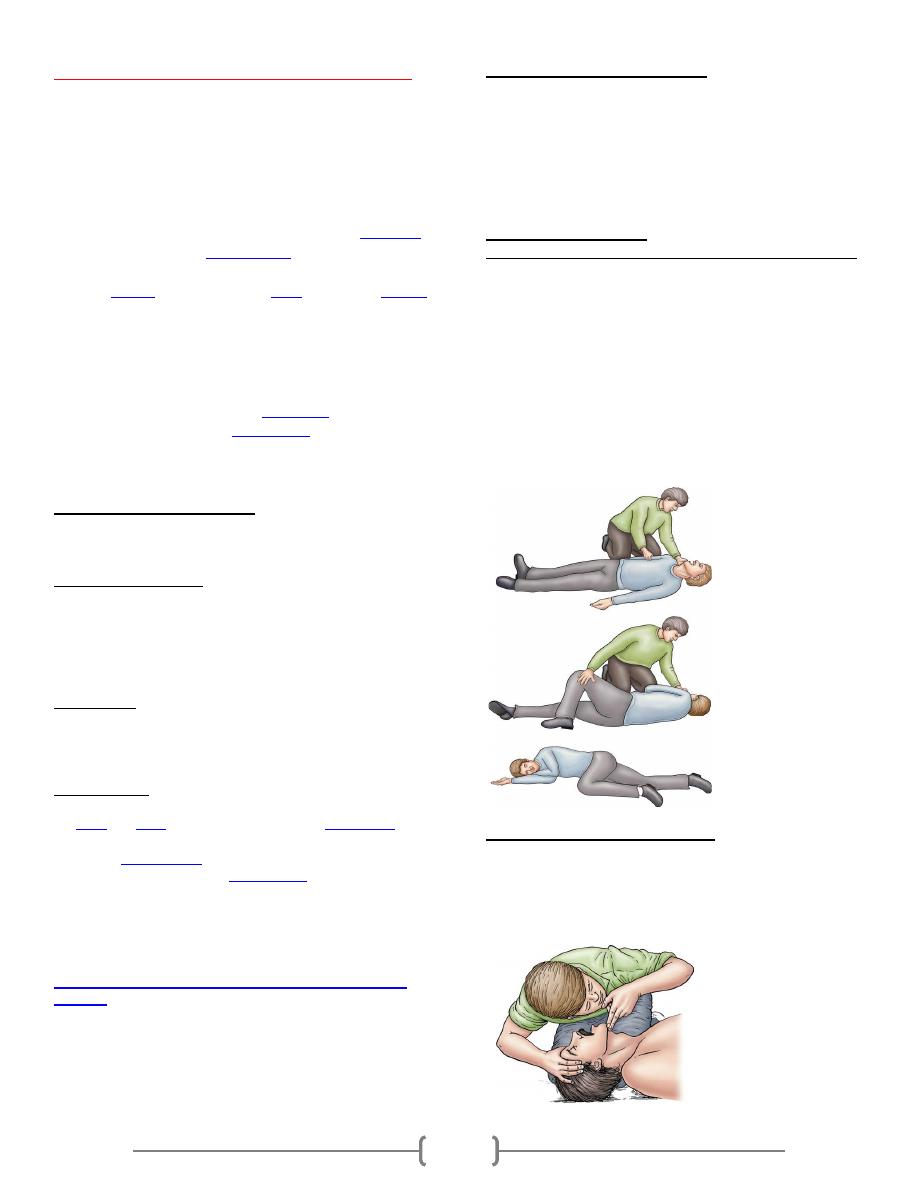

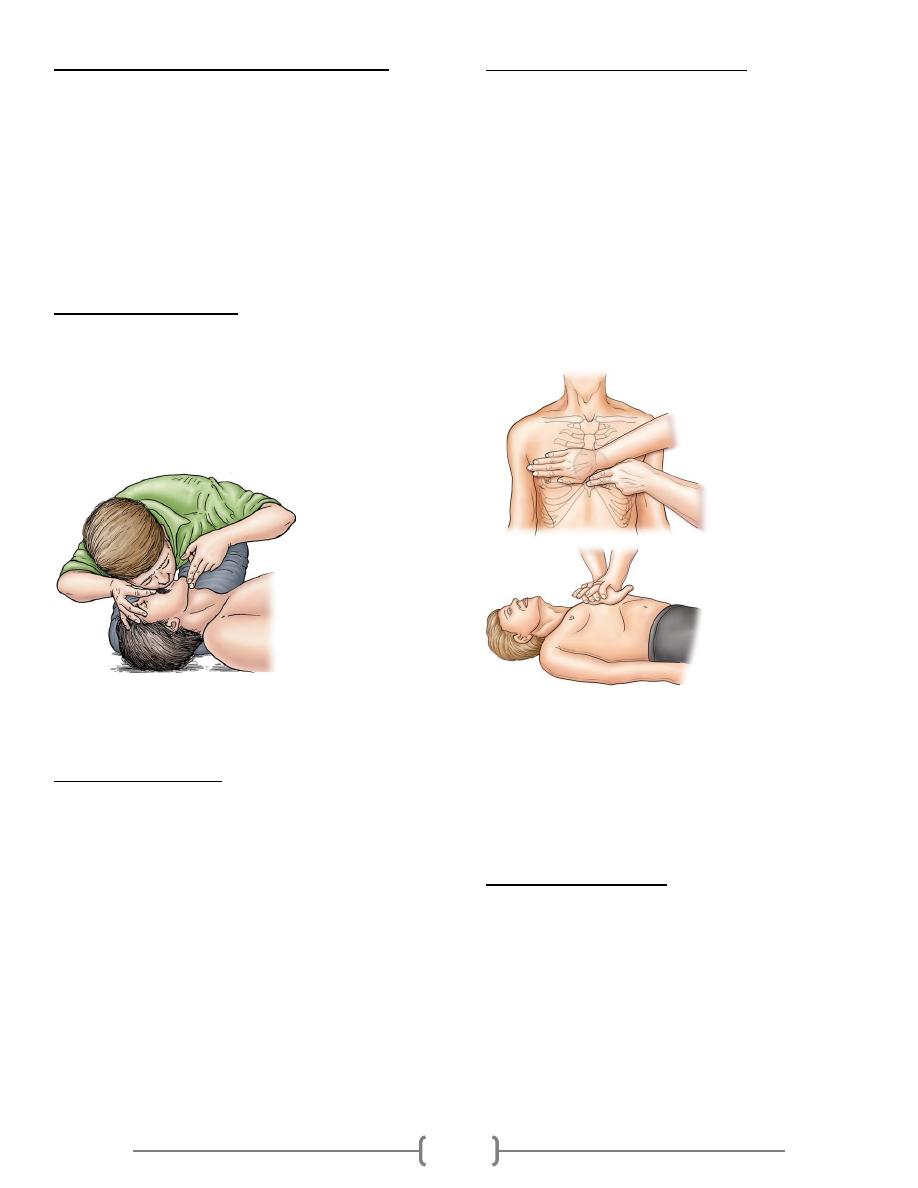

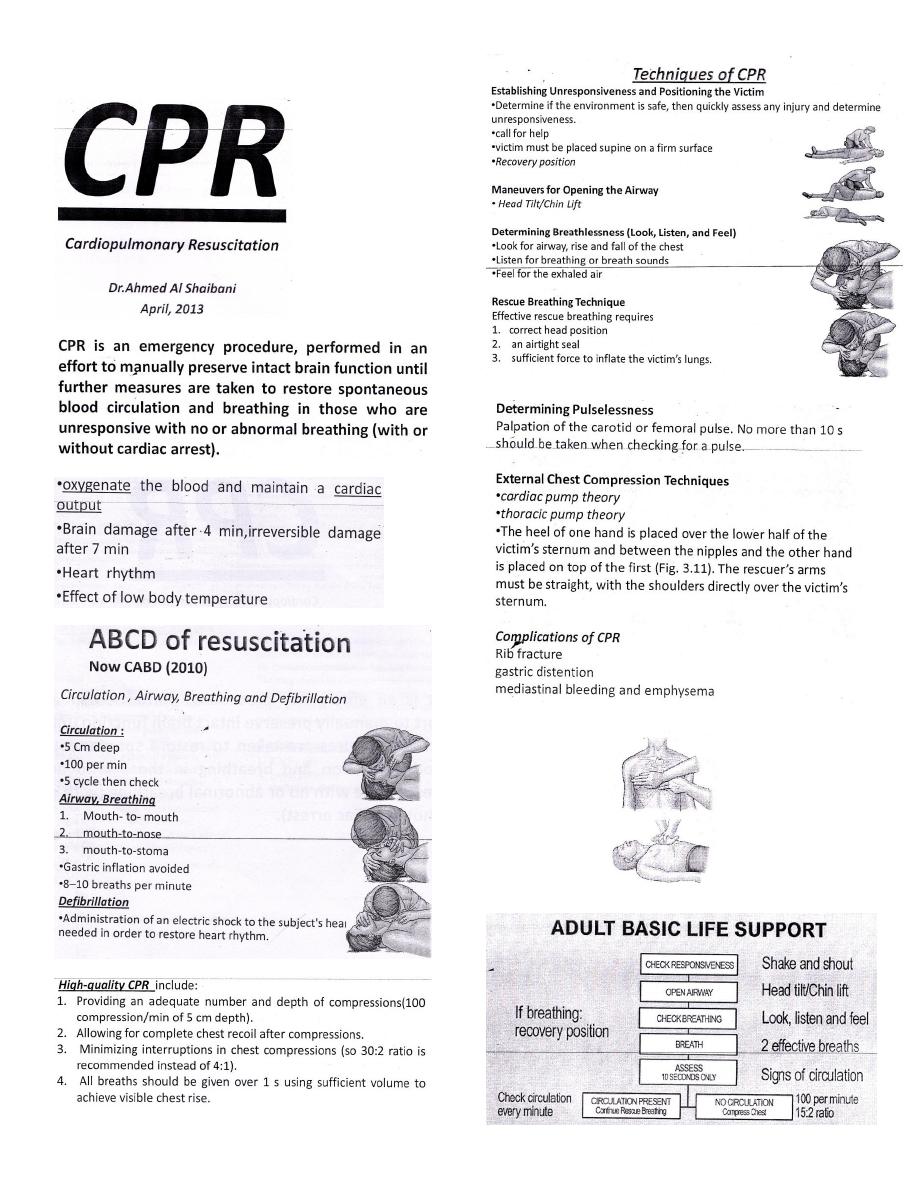

Lab 36 – Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)

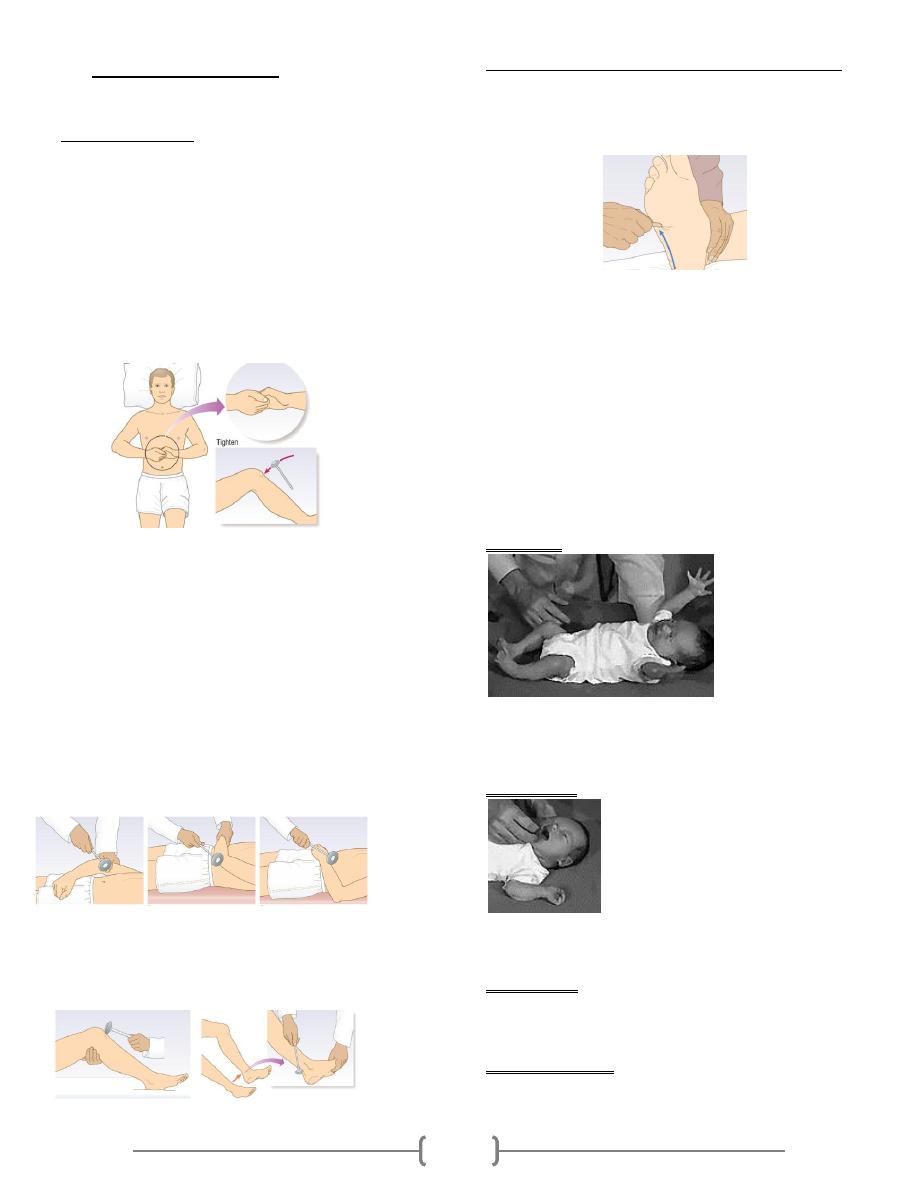

Lab 37 – Reflexes

دكتور صباح

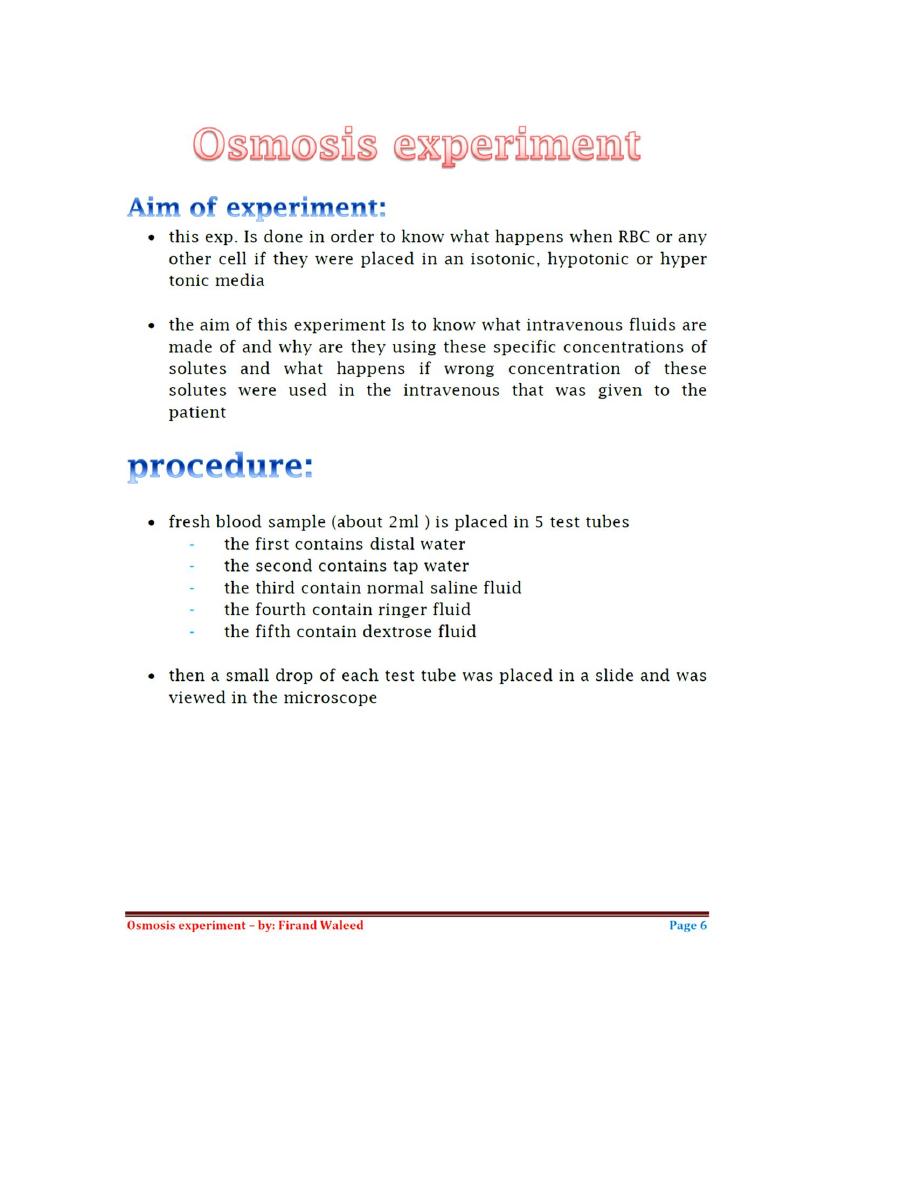

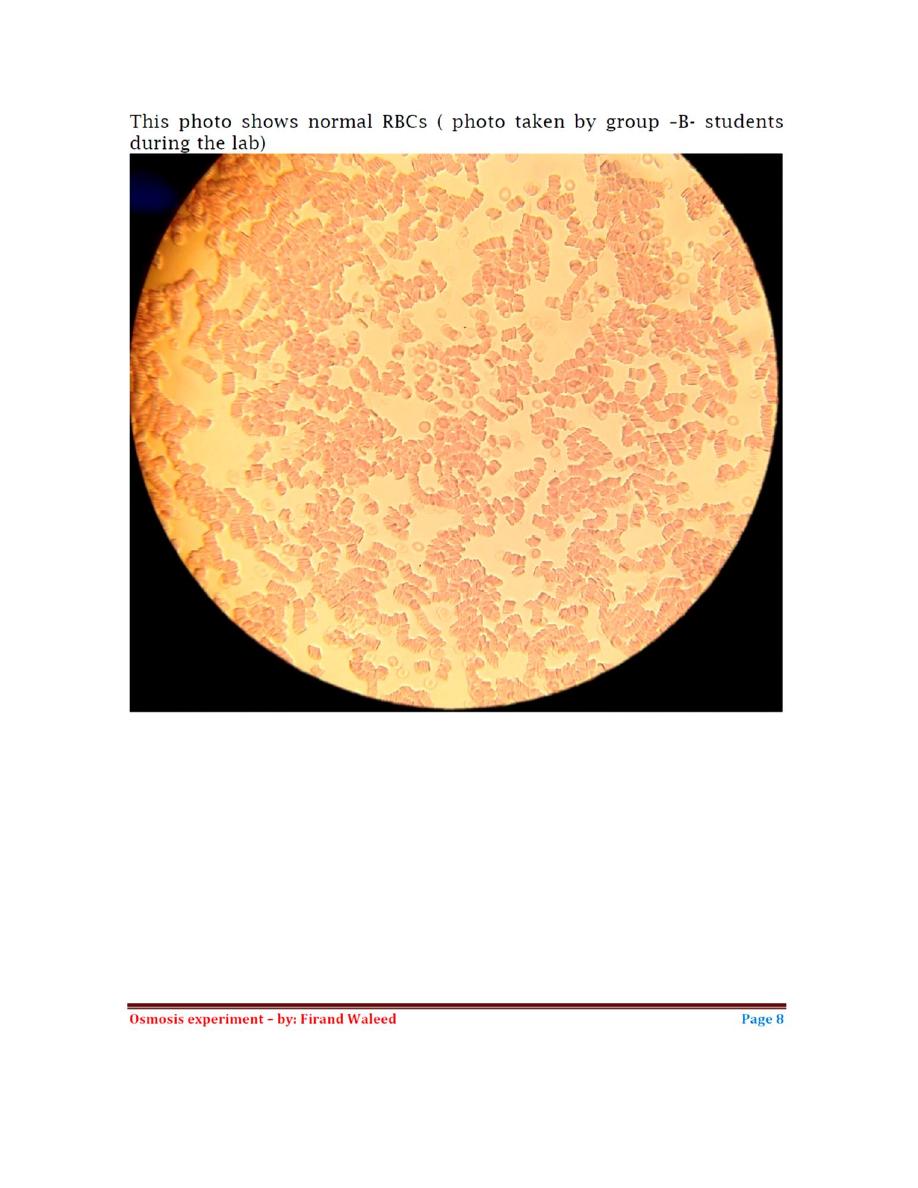

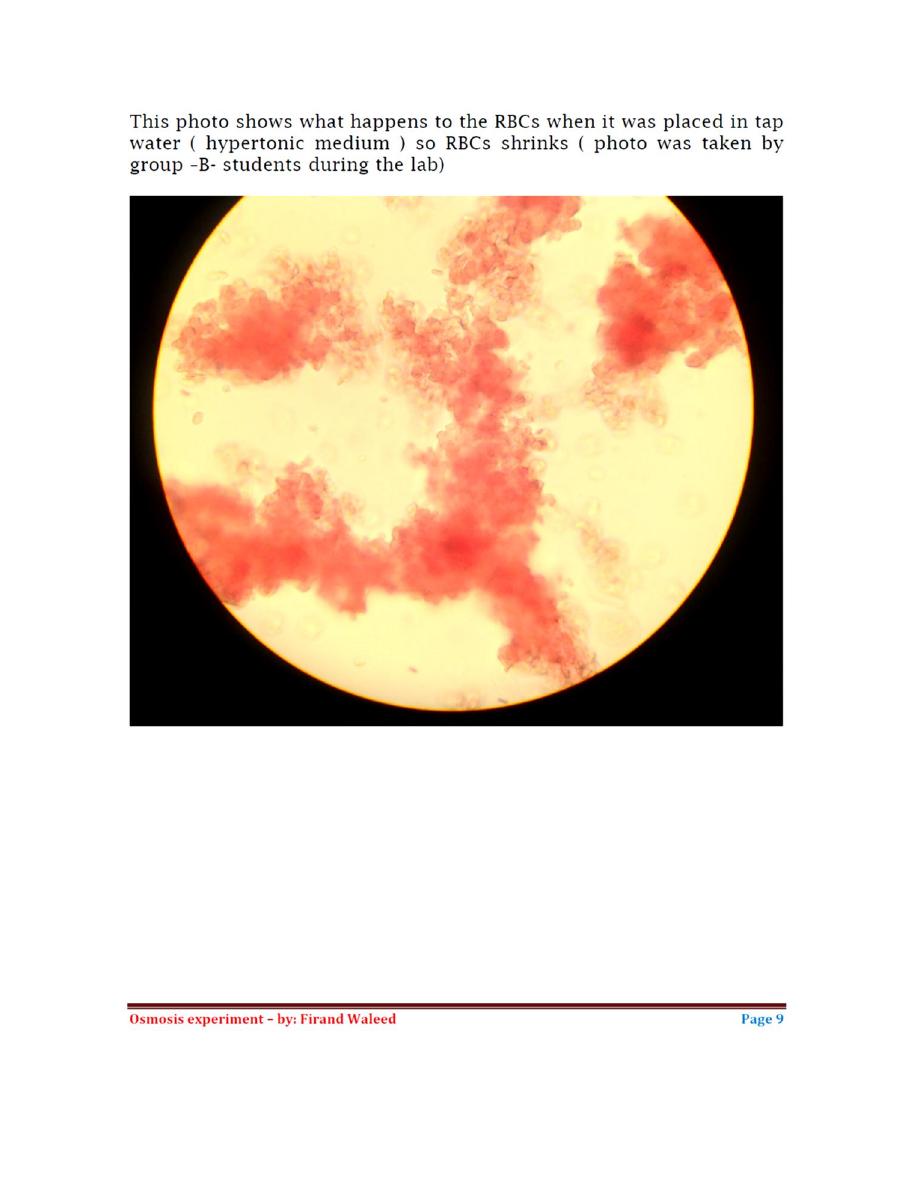

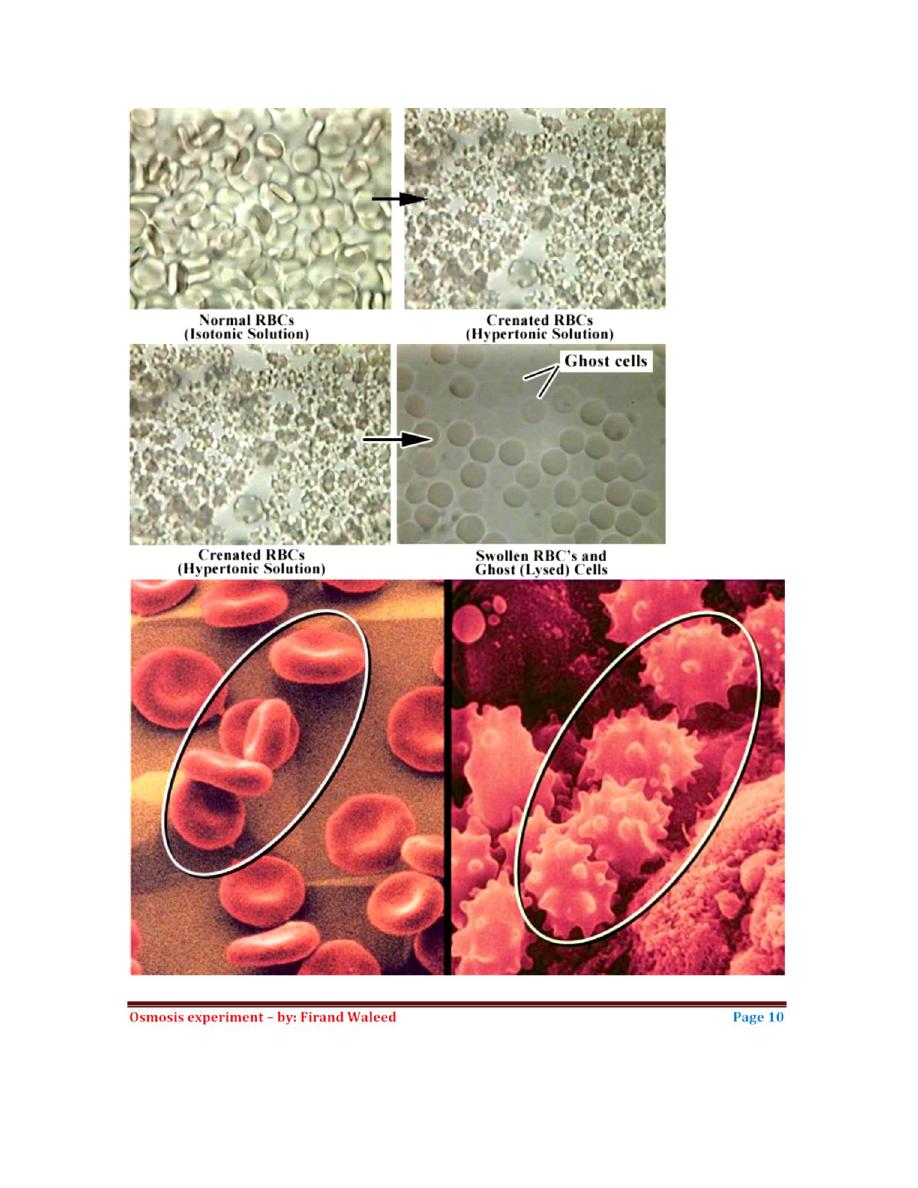

Lab 38 – Osmosis

Lab 39 – Semen

1

Blood typing

Blood typing is a method to tell what specific type of blood

you have. What type you have depends on whether or not

there are certain proteins, called antigens, on your RBCs.

Blood is often grouped according to the ABO blood typing

system. This method breaks blood types down into four

categories: A, B, AB & O.

Your blood type (or blood group) depends on the types that

are been passed down to you from your parents.

How the Test is performed

Blood is drawn from a vein, usually from the inside of the

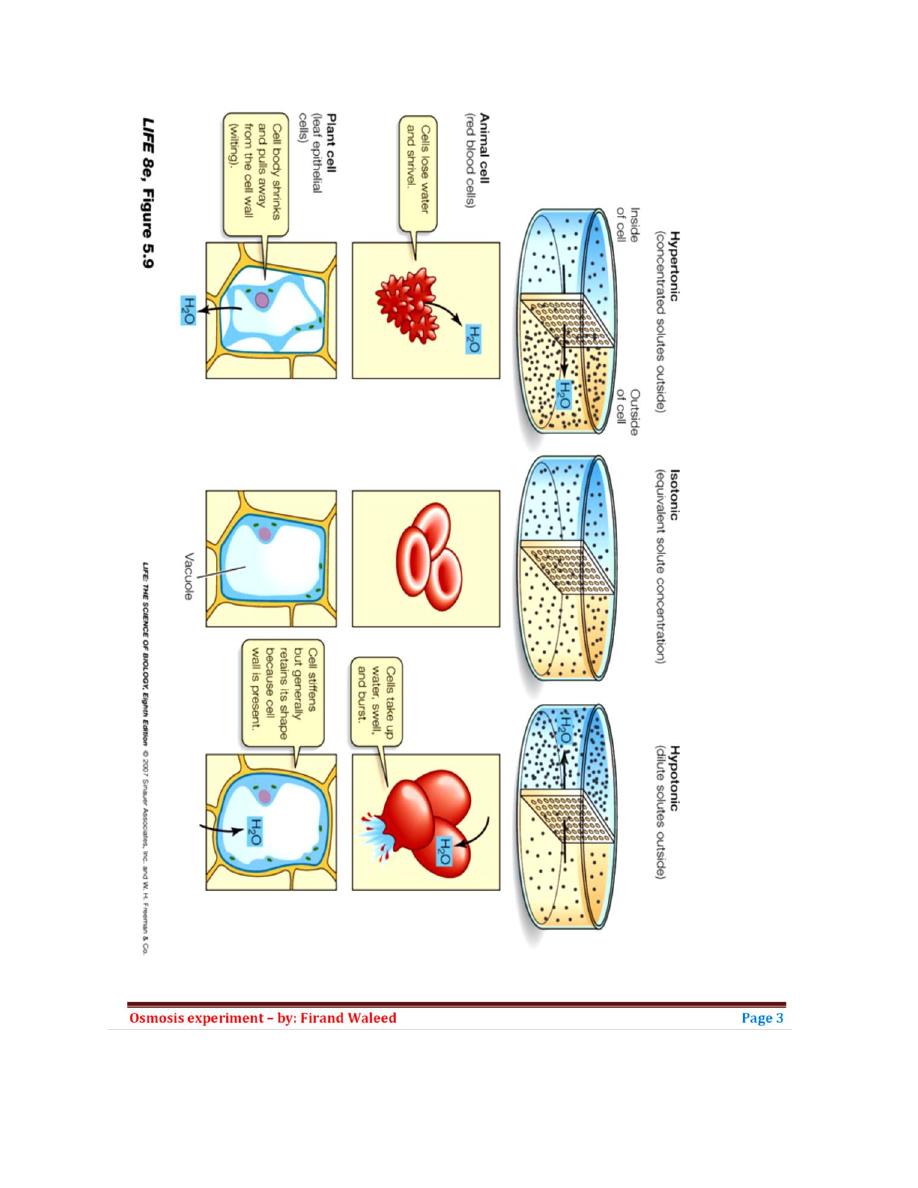

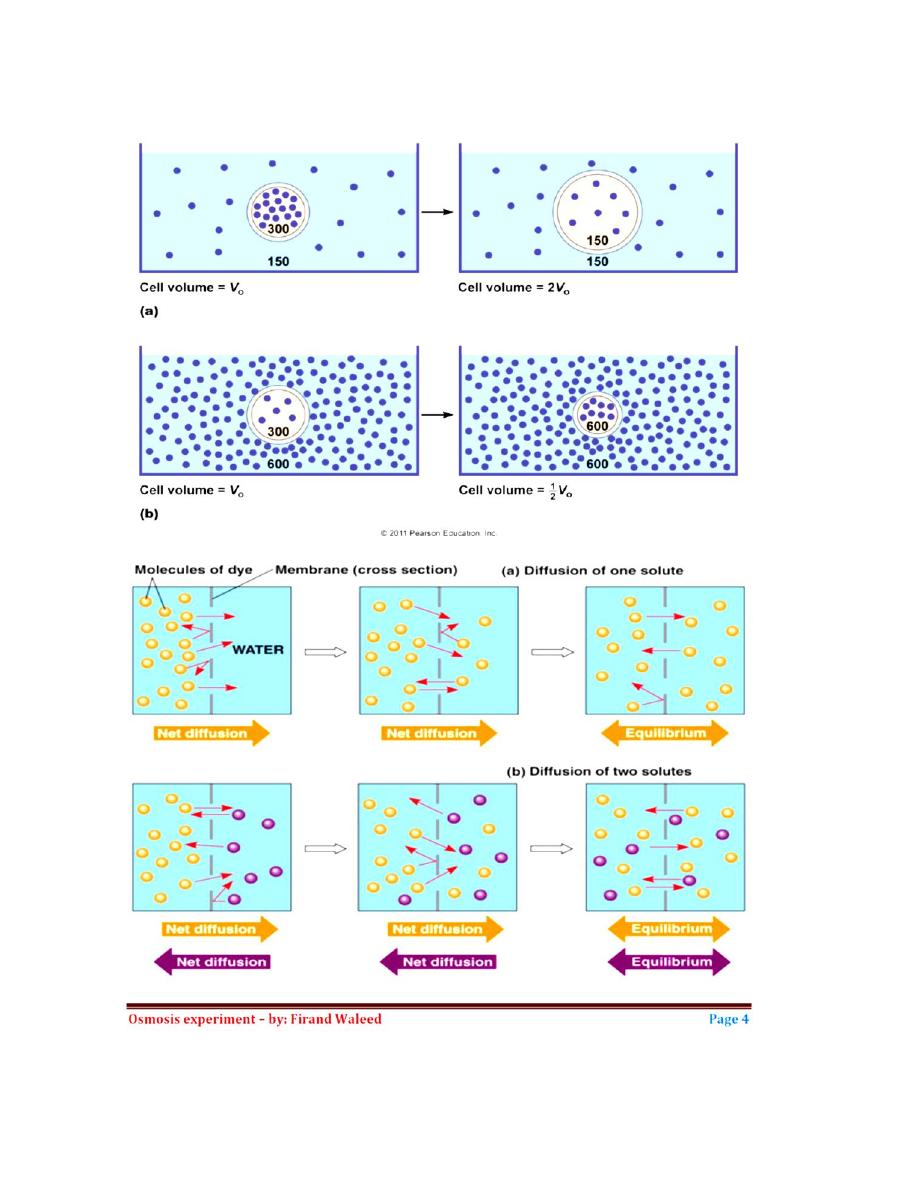

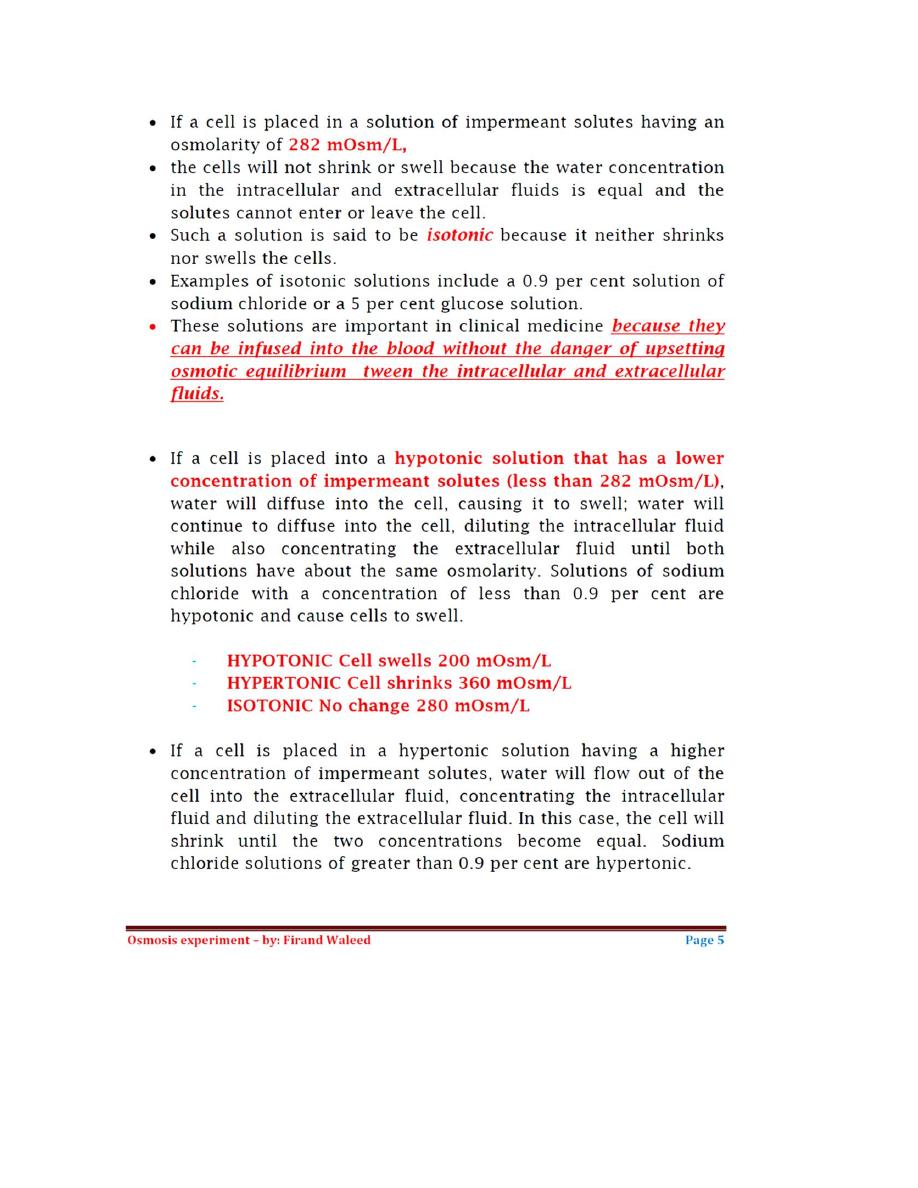

elbow or the back of the hand. The puncture site is cleaned

with a germ-killing product. An elastic band is placed around

the upper arm to apply pressure, which causes the vein to

swell with blood.

A needle is inserted into the vein, and the blood is collected

into a tube. During the procedure, the elastic band is removed

to restore circulation. Once the blood has been collected, the

needle is removed, and a band-aid or gauze is applied.

In infants or young children, the area is cleansed with

antiseptic and punctured with a sharp needle or a lancet. The

blood may be collected in a pipette (small glass tube), on a

slide, onto a test strip, or into a small container. A bandage

may be applied if there is any bleeding.

The test to determine your blood group is called ABO typing.

Your blood sample is mixed with antibodies against type A

and B blood, and the sample is checked to see whether or not

the blood cells stick together (agglutinate). If blood cells stick

together, it means the blood reacted with one of the antibodies.

The second step is called back typing. The liquid part of your

blood without cells (serum) is mixed with blood that is known

to be type A and type B. Persons with type A blood have anti-

B antibodies, and those with type B blood have anti-A

antibodies. Type O blood contains both types of antibodies.

These two steps can accurately determine your blood type.

Blood typing is also done to tell whether or not you have a

substance called Rh factor on the surface of your red blood

cells. If you have this substance, you are considered Rh+

(positive). Those without it are considered Rh- (negative). Rh

typing uses a method similar to ABO typing.

How to Prepare for the Test

No special preparation is necessary for this test.

How the Test Will Feel

Some people have discomfort when the needle is inserted.

Others may only feel a tiny prick or stinging sensation.

Afterward, there may be some throbbing or a bruise may

develop.

Why the Test is performed

This test is done to determine a person's blood type. Health

care providers need to know your blood type when you get a

blood transfusion or transplant, because not all blood types are

compatible with each other. For example:

If you have type A blood, you can only receive types A

and O blood.

If you have type B blood, you can only receive types B

and O blood.

If you have type AB blood, you can receive types A, B,

AB, and O blood.

If you have type O blood, you can only receive type O

blood.

Type O blood can be given to anyone with any blood type.

That is why people with type O blood are called universal

blood donors.

Blood typing is especially important during pregnancy. If the

mother is found to be Rh-, the father should also be tested. If

the father has Rh+ blood, the mother needs to receive a

treatment to help prevent the development of substances that

may harm the unborn baby. See:

Rh incompatibility

If you are Rh+, you can receive Rh+ or Rh- blood. If you are

Rh-, you can only receive Rh- blood.

Normal Results

ABO typing:

If your blood cells stick together when mixed with:

Anti-A serum, you have type A blood

Anti-B serum, you have type B blood

Both anti-A and anti-B serums, you have type AB blood

If your blood cells do not stick together when anti-A and anti-

B are added, you have type O blood.

Back typing:

If the blood clumps together only when B cells are added

to your sample, you have type A blood.

If the blood clumps together only when A cells are added

to your sample, you have type B blood.

If the blood clumps together when either types of cells are

added to your sample, you have type O blood.

Lack of blood cells sticking together when your sample is

mixed with both types of blood indicates you have type AB

blood.

RH typing:

If your blood cells stick together when mixed with anti-

Rh serum, you have type Rh-positive blood.

If your blood does not clot when mixed with anti-Rh

serum, you have type Rh-negative blood.

Risks

Risks associated with taking blood may include:

Fainting or feeling light-headed

Multiple punctures to locate veins

2

Excessive bleeding

Hematoma

(blood accumulating under the skin)

Infection (a slight risk any time the skin is broken)

Considerations

There are many antigens besides the major ones (A, B, and

Rh). Many minor ones are not routinely detected during blood

typing. If they are not detected, you may still have a reaction

when receiving certain types of blood, even if the A, B, and

Rh antigens are matched.

A process called cross-matching followed by a

Coombs' test

can help detect these minor antigens and is routinely done

prior to transfusions, except in emergency situations.

Alternative Names

Cross matching; Rh typing; ABO blood typing

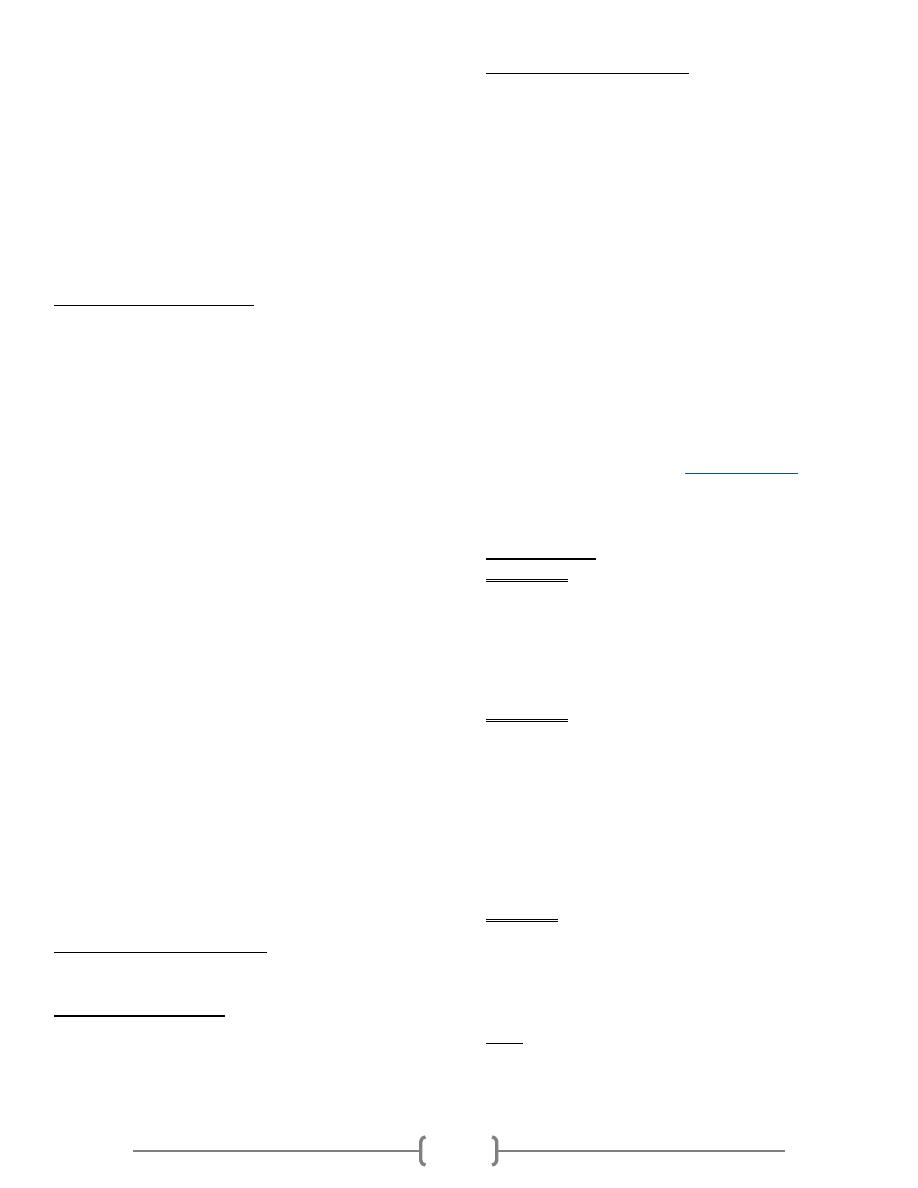

Eldoncard in home blood type test - step by

step procedure

This fast, easy to use blood typing kit contains everything

required to determine blood group and Rh factor using a

whole blood sample obtained from a finger prick without the

need for separate reagents or laboratory training. The

EldonCard is a patented test card device that comes specially

treated and impregnated with dried antibody sera Anti-A,

Anti-B and Anti-Rh used universally for determining Blood

type by the forward typing method. Creates a Permanent

Blood Type Record Card for medical histories and

emergencies.

1) Wash your hands before carrying out the test and again after

carrying out the test.

2) Open the foil pouch containing the test cards, the 2 tests are on

the one card so you need to cut the tests into 2 single cards.

Using a pair of scissors cut the cards in half, down the line in

the middle of the two. Place the card on a table or flat surface.

3) Lay out the applicators (eldonsticks) ready for use.

4) Fill a small cup with tap water and using the plastic pipette,

draw a small volume of the tap water into the plastic pipette.

You draw the water by simply holding the small, thin end in

the water and squeezing the top part.

5) With the test card still on a flat surface release one drop of

water onto each of the coloured reagents spots on the

EldonCard.

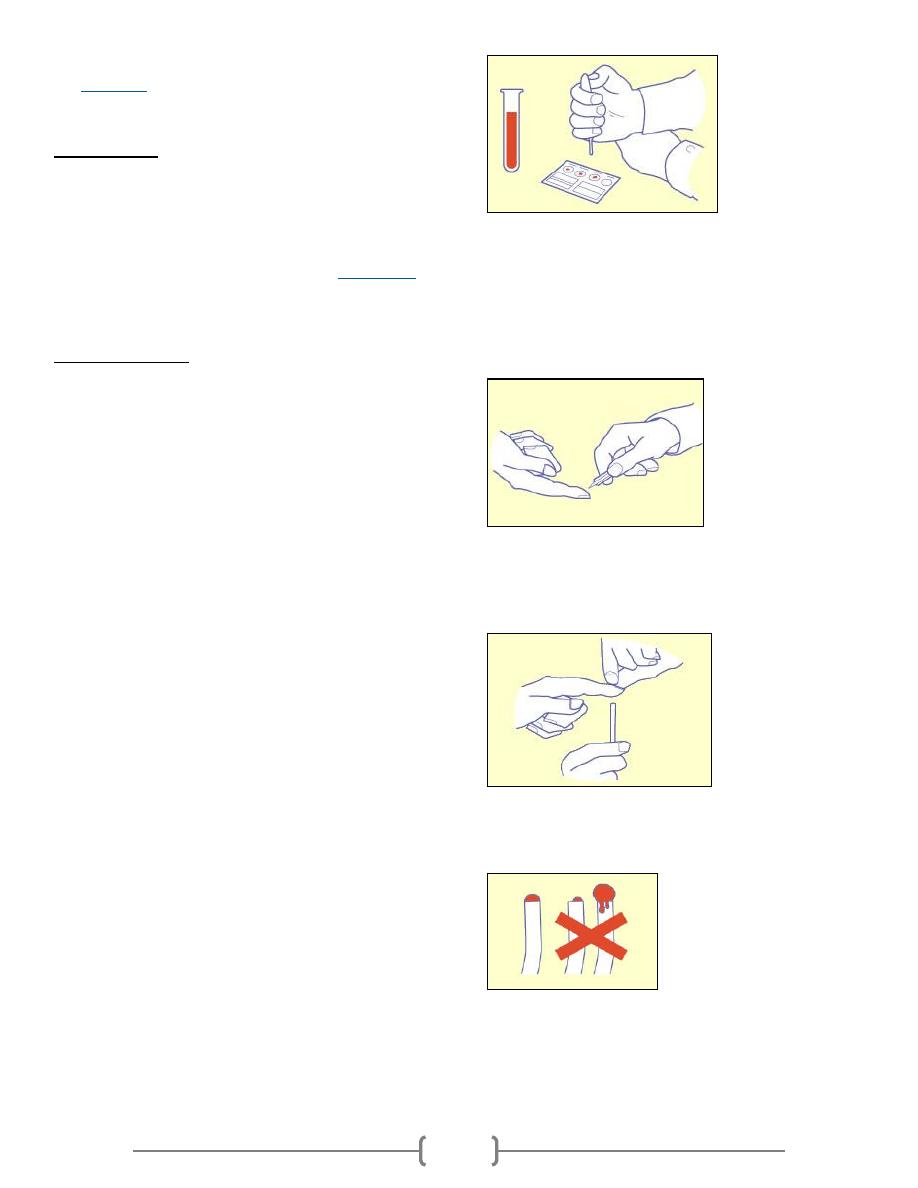

6) Twist off the little green protective cap from the lancet. Place

the lancet upon a table.

7) Wipe a fingertip with the alcohol impregnated tissue provided

and allow it to dry.

8) Place the lancet against the end of the finger and press the

green body against your finger to release the needle.

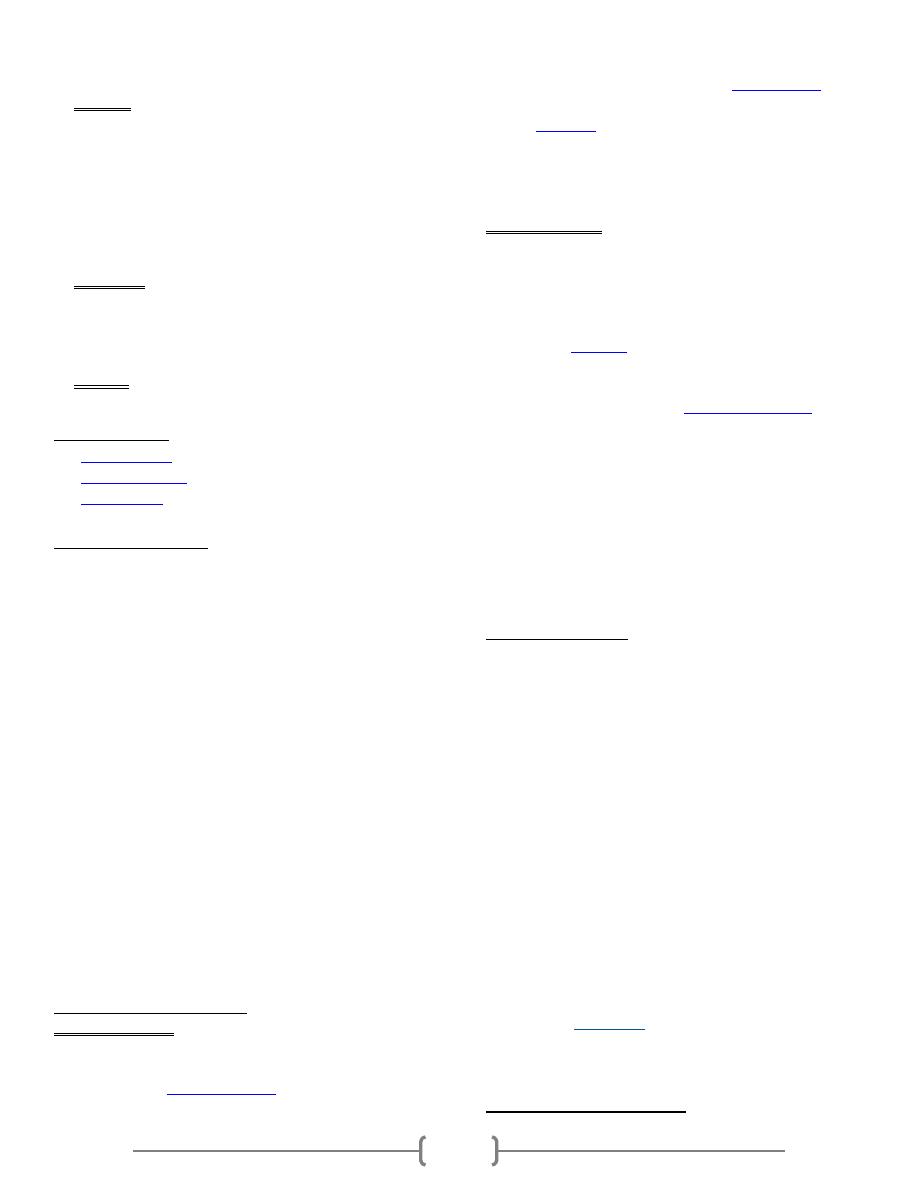

9) Massage the finger from the bottom to the top to encourage

bloodflow. Press the blood towards fingertip. Repeat pressing

until a drop with a 3 to 4 mm (1/8 inch) diameter is seen.

10) Transfer the blood to an EldonStick, approached from beneath

the finger. Don't smear the blood over the skin.

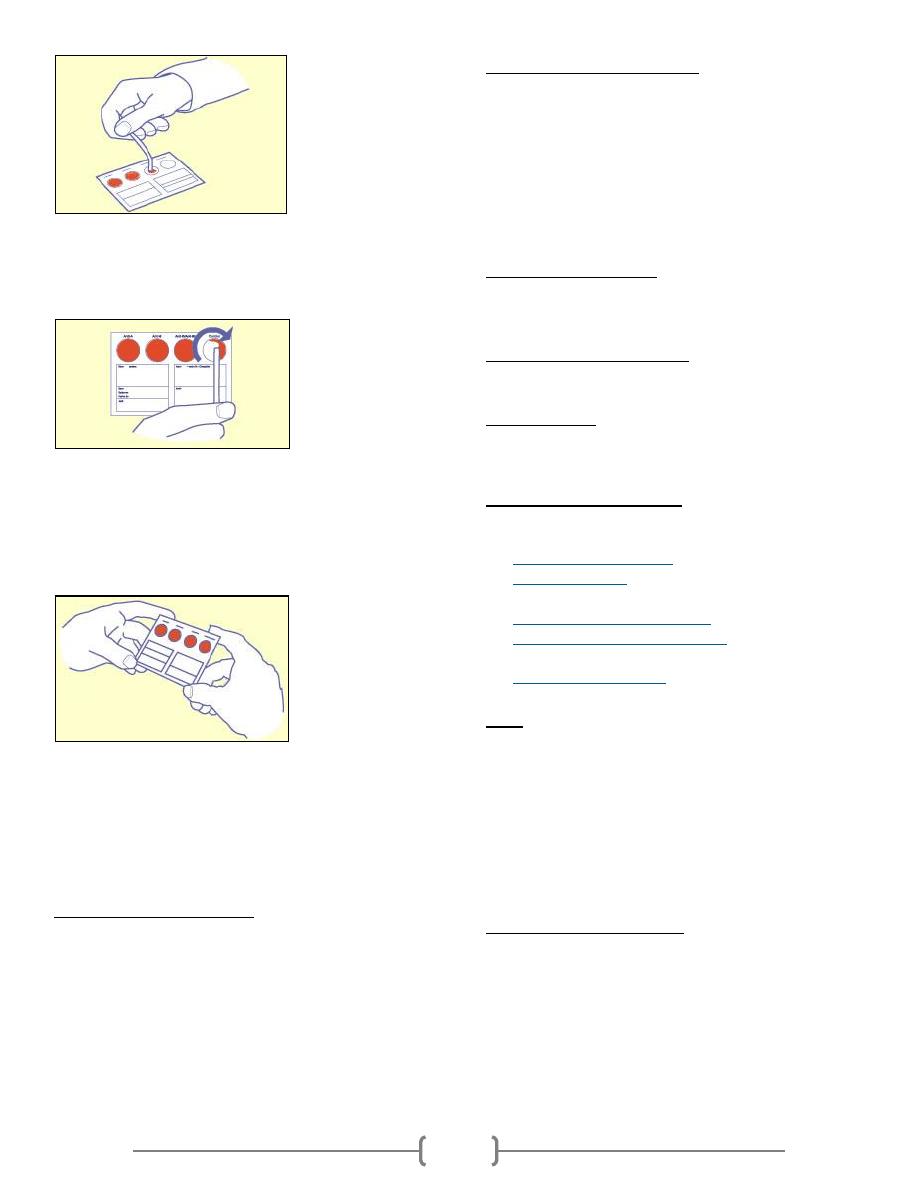

11) Place the eldonstick with the drop of blood into the first circle.

The blood should touch the water already present. Gently

press the side of the eldonstick head against the card and stir

in the water and blood mixture until the coloured dry material

has dissolved.

3

12) Repeat this procedure for the other 3 circles, making sure you

use a new eldonstick for each circle. You should NEVER

transfer liquid from one circle to another.

13) Once all 4 circles are complete gently tilt the whole card

vertically on its bottom edge and keep this position for 10

seconds. You will see the blood flowing slowly to the bottom

of the circle. Repeat this procedure tilting the card on the 3

other sides

Bleeding time

Bleeding time is a blood test that looks at how fast small blood

vessels in the skin close to stop you from bleeding.

How the Test is performed

A blood pressure cuff is inflated around your upper arm.

While the cuff is on your arm, the health care provider makes

two small cuts on the lower arm. They are just deep enough to

cause a tiny amount of bleeding.

The blood pressure cuff is immediately deflated. Blotting

paper is touched to the cuts every 30 seconds until the

bleeding stops. The health care provider records the time it

takes for the cuts to stop bleeding.

How to Prepare for the Test

Certain medications may change the test results. Always tell

your doctor what medications you are taking, even over-the-

counter drugs. Drugs that may increase bleeding times include

dextran, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and

salicylates (including aspirin).

Your doctor may tell you to stop taking certain medicines a

few days before the test. Never stop taking medicine without

first talking to your doctor.

How the Test Will Feel

The tiny cuts are very shallow. Most people say it feels like a

skin scratch.

Why the Test is Performed

This test helps diagnose bleeding problems.

Normal Results

Bleeding normally stops within 1 to 9 minutes. However,

values may vary from lab to lab.

What Abnormal Results Mean

Longer-than-normal bleeding time may be due to:

Blood vessel defect

Platelet aggregation defect

Thrombocytopenia

(low platelet count)

Additional conditions under which the test may be performed:

Acquired platelet function defect

Congenital platelet function defects

Primary thrombocythemia

Von Willebrand's disease

Risks

There is a very slight risk of infection where the skin is

broken. Excessive bleeding is rare

Blood Clotting Tests

Blood clotting tests are used to diagnose and assess bleeding

problems and to monitor people who take warfarin or other

anticoagulant medicines.

What is blood made up of?

Plasma, the liquid part of blood, makes up about 60% of the

blood's volume. Plasma is mainly made from water but

contains many different proteins and other chemicals such as

hormones, antibodies, enzymes, glucose, fat particles, salts,

etc.

Blood cells, which can be seen under a microscope, make up

about 40% of the blood's volume. Blood cells are made in the

4

bone marrow by blood 'stem' cells. Blood cells are divided

into three main types.

Red cells (erythrocytes). These make blood a red colour.

One drop of blood contains about five million red cells. A

constant new supply of red blood cells is needed to replace

old cells that break down. Millions are released into the

bloodstream from the bone marrow each day. Red cells

contain chemical called haemoglobin. Haemoglobin is

attracted to oxygen and the two substances can bind

together. This allows oxygen to be transported by red

blood cells from the lungs to all parts of the body.

White cells (leukocytes). There are different types of white

cells such as neutrophils (polymorphs), lymphocytes,

eosinophils, monocytes, basophils. They are a part of the

immune system and are mainly involved in combating

infection.

Platelets. These are tiny and help the blood to clot if we

cut ourselves

Related articles

Anticoagulants

Atrial Fibrillation

Gallium Scan

How does blood clot?

Within seconds of cutting a blood vessel, the damaged tissue

causes platelets to become 'sticky' and clump together around

the cut. These 'activated' platelets and the damaged tissue

release chemicals which react with other chemicals and

proteins in the plasma, called clotting factors. There are 13

known clotting factors which are called by their Roman

numbers - factor I to factor XIII. A complex cascade of

chemical reactions involving these clotting factors quickly

occurs next to a cut.

The final step of this cascade of chemical reactions is to

convert factor I (also called fibrinogen - a soluble protein) into

thin strands of a solid protein called fibrin. The strands of

fibrin form a meshwork and trap blood cells and platelets

which form into a solid clot.

If a blood clot forms within a healthy blood vessel it can cause

serious problems. So, there are also chemicals in the blood

that prevent clots from forming and chemicals that 'dissolve'

clots. There is balance between forming clots and preventing

clots. Normally, unless a blood vessel is damaged or cut, the

'balance' tips in favour of preventing clots forming within

blood vessels.

What problems can occur?

Bleeding disorders

There are various conditions where you tend to bleed

excessively if you damage or cut a blood vessel - for example:

Too few platelets (

thrombocytopenia

) - due to various causes.

Genetic conditions where you do not make one or more

clotting factors. The most well known is

haemophilia A

which

occurs in people who do not make factor VIII.

Lack of

vitamin K

, which can cause bleeding problems, as you

need this vitamin to make certain clotting factors.

Liver disorders - these sometimes cause bleeding problems, as

your liver makes most of the clotting factors.

Clotting disorders

Sometimes a blood clot forms within a blood vessel that has

not been injured or cut - for example:

A blood clot that forms within an artery supplying blood to

the heart or brain is the common cause of heart attack and

stroke. The platelets become sticky and clump next to

patches of

atheroma

(fatty material) in blood vessels and

activate the clotting mechanism.

Sluggish blood flow can make the blood clot more readily

than usual. This is a factor in

deep vein thrombosis

(DVT)

which is a blood clot that sometimes forms in a leg vein.

Certain genetic conditions can make the blood clot more

easily than usual.

Certain medicines can affect the blood clotting mechanism,

or increase the amount of some clotting factors, which may

result in the blood clotting more readily

Liver disorders can sometimes cause clotting problems, as

your liver makes some of the chemicals involved in

preventing and dissolving clots.

Blood clotting tests

You may be advised to have tests of blood clotting:

If you have a suspected bleeding disorder. For example, if

you bleed a lot after cuts, or if you bruise easily.

If you have certain liver diseases that can affect the

making of blood clotting factors.

Before surgery, in certain circumstances, to assess your

risk of bleeding problems during an operation.

If you develop a blood clot within a blood vessel for no

apparent reason.

If you take anticoagulant medication such as warfarin (to

check that you are taking the correct dose).

There are a number of different tests. The ones chosen depend

on the circumstances and the suspected problem.

RBC count

An RBC count is a blood test that tells how many red blood

cells (RBCs) you have.

RBCs contain

hemoglobin

, which carries oxygen. How much

oxygen your body tissues get depends on how many RBCs

you have and how well they work.

How the Test is Performed

5

A blood sample is needed. For information on how this is

done, see:

Venipuncture

How to Prepare for the Test

No special preparation is necessary for adults.

How the Test Will Feel

When the needle is inserted to draw blood, some people feel

moderate pain, while others feel only a prick or stinging

sensation. Afterward, there may be some throbbing.

Why the Test is Performed

The RBC count is almost always part of the

CBC

(complete

blood count) test.

The test can help diagnose anemia and other conditions

affecting red blood cells.

Additional conditions under which an RBC count may be

performed:

Alport syndrome

Drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia

Hemolytic anemia due to G6PD deficiency

Hereditary anemias, such as thalassemia

Idiopathic autoimmune hemolytic anemia

Immune hemolytic anemia

Macroglobulinemia of Waldenstrom

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH)

Primary myelofibrosis

Normal Results

The general the range is as follows:

Male: 4.7 to 6.1 million cells per microliter (cells/mcL)

Female: 4.2 to 5.4 million cells/mcL

Note: Normal value ranges may vary slightly among different

laboratories. Talk to your doctor about the meaning of your

specific test results.

The examples above show the common measurements for

results for these tests. Some laboratories use different

measurements or may test different specimens.

What Abnormal Results Mean

Higher-than-normal numbers of RBCs may be due to:

Cigarette smoking

Congenital heart disease

Cor pulmonale

Dehydration

(such as from severe diarrhea)

Kidney tumor (renal cell carcinoma)

Low blood oxygen levels (hypoxia)

Pulmonary fibrosis

Polycythemia vera

Your RBC count will increase for several weeks when you

move to a higher altitude.

Drugs that can increase the RBC count include:

Gentamicin

Methyldopa

Lower-than-normal numbers of RBCs may be due to:

Anemia

Bone marrow failure (for example, from radiation, toxins,

or tumor)

Erythropoietin deficiency (secondary to kidney disease)

Hemolysis (RBC destruction) due to transfusion, blood

vessel injury, or other cause

Hemorrhage (bleeding)

Leukemia

Malnutrition

Multiple myeloma

Nutritional deficiencies of:

o Iron

o

Copper

o

Folate

o

Vitamin B-12

o

Vitamin B-6

Overhydration

Pregnancy

Drugs that can decrease the RBC count include:

Chemotherapy drugs

Chloramphenicol

Hydantoins

Quinidine

Risks

There is very little risk involved with having your blood taken.

Veins and arteries vary in size from one patient to another and

from one side of the body to the other. Taking blood from

some people may be more difficult than from others.

Other risks associated with having blood drawn are slight but

may include:

Excessive bleeding

Fainting or feeling light-headed

Hematoma (blood accumulating under the skin)

Infection (a slight risk any time the skin is broken)

Alternative Names

Erythrocyte count; Red blood cell count

WBC count

A WBC count is a blood test to measure the number of white

blood cells (WBCs).

White bloods cells help fight infections. They are also called

leukocytes. There are five major types of white blood cells:

Basophils

Eosinophils

Lymphocytes (T cells and B cells)

6

Monocytes

Neutrophils

See also:

Blood differential

How the Test is performed

Blood is typically drawn from a vein, usually from the inside

of the elbow or the back of the hand. The site is cleaned with

germ-killing medicine (antiseptic). The health care provider

wraps an elastic band around the upper arm to apply pressure

to the area and make the vein swell with blood.

Next, the health care provider gently inserts a needle into the

vein. The blood collects into an airtight vial or tube attached to

the needle. The elastic band is removed from your arm.

Once the blood has been collected, the needle is removed, and

the puncture site is covered to stop any bleeding.

In infants or young children, a sharp tool called a lancet may

be used to puncture the skin and make it bleed. The blood

collects into a small glass tube called a pipette, or onto a slide

or test strip. A bandage may be placed over the area if there is

any bleeding.

The blood sample is sent to a laboratory. A WBC count is

almost always done as part of a

complete blood count

(CBC).

How to Prepare for the Test

No special preparation is usually needed. Tell your doctor

about any medications you are taking, including over-the-

counter products. Certain drugs may interfere with test results.

Drugs that may increase WBC counts include:

Allopurinol

Aspirin

Chloroform

Corticosteroids

Epinephrine

Heparin

Quinine

Triamterene

Drugs that may lower your WBC count include:

Antibiotics

Anticonvulsants

Antihistamines

Antithyroid drugs

Arsenicals

Barbiturates

Chemotherapy drugs

Diuretics

Sulfonamides

How the Test Will Feel

When the needle is inserted to draw blood, some people feel

moderate pain, while others feel only a prick or stinging

sensation. Afterward, there may be some throbbing.

Why the Test is performed

Your doctor will order this test to find out how many white

blood cells you have. Your body produces more white blood

cells when you have an infection or allergic reaction -- even

when you are under general stress.

Normal Results

4,500-10,000 white blood cells per microliter (mcL).

Note: Normal value ranges may vary slightly among different

laboratories. Talk to your doctor about the meaning of your

specific test results.

The examples above show the common measurements for

results for these tests. Some laboratories use different

measurements or may test different specimens.

What Abnormal Results Mean

A low number of WBCs is called leukopenia. It may be due

to:

Bone marrow deficiency or failure (for example, due to

infection, tumor, or abnormal scarring)

Collagen-vascular diseases (such as

systemic lupus

erythematosus

)

Disease of the liver or spleen

Radiation therapy or exposure

A high number of WBCs is called leukocytosis. It may be due

to:

Anemia

Bone marrow tumors

Infectious diseases

Inflammatory disease (such as

rheumatoid arthritis

or

allergy

)

Leukemia

Severe emotional or physical stress

Tissue damage (for example, burns)

These lists are not all inclusive.

Risks

There is very little risk involved with having your blood taken.

Veins and arteries vary in size from one patient to another and

from one side of the body to the other. Taking blood from

some people may be more difficult than from others.

Other risks associated with having blood drawn are slight but

may include:

Excessive bleeding

Fainting or feeling light-headed

Hematoma (blood accumulating under the skin)

Infection (a slight risk any time the skin is broken)

Considerations

People who have had their spleen removed (

splenectomy

) will

always have a slightly higher number of WBCs.

Alternative Names

Leukocyte count; White blood cell count

1

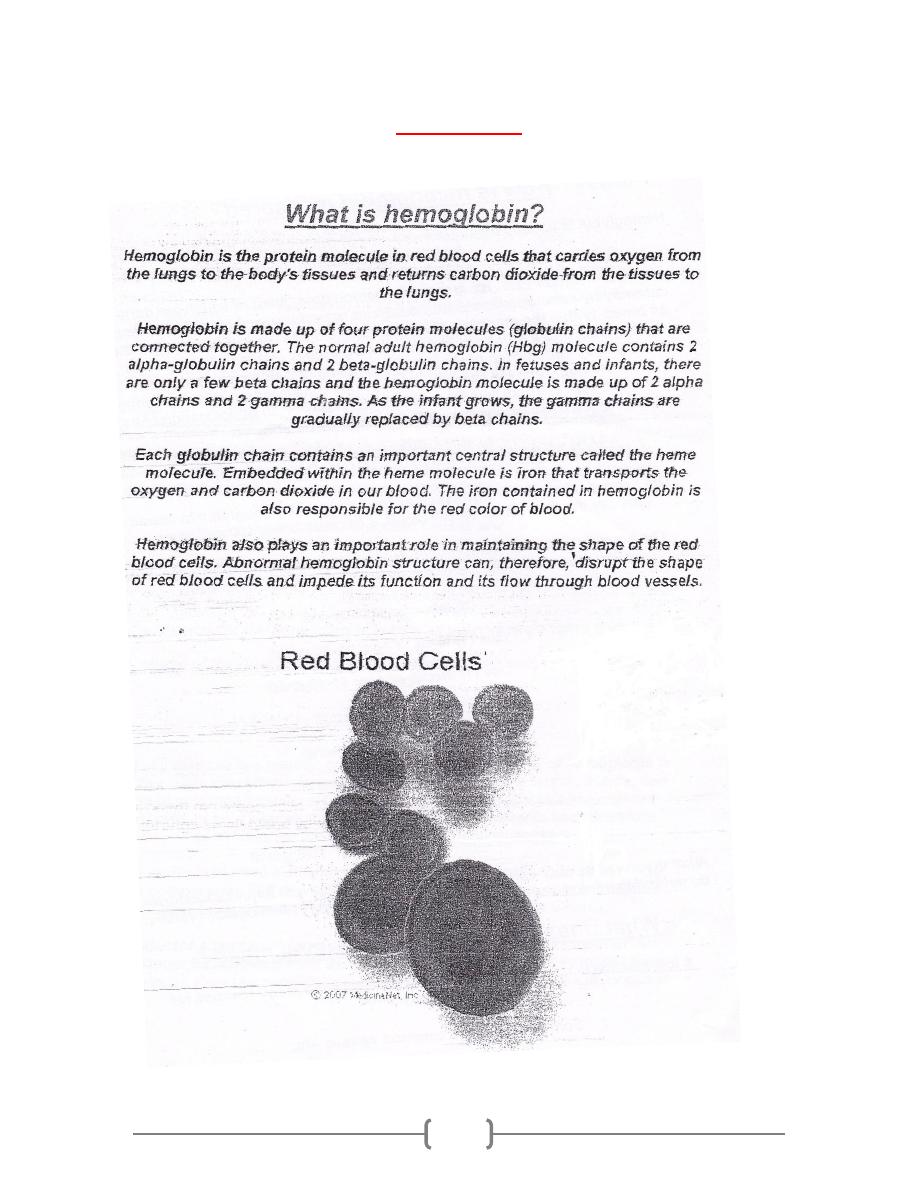

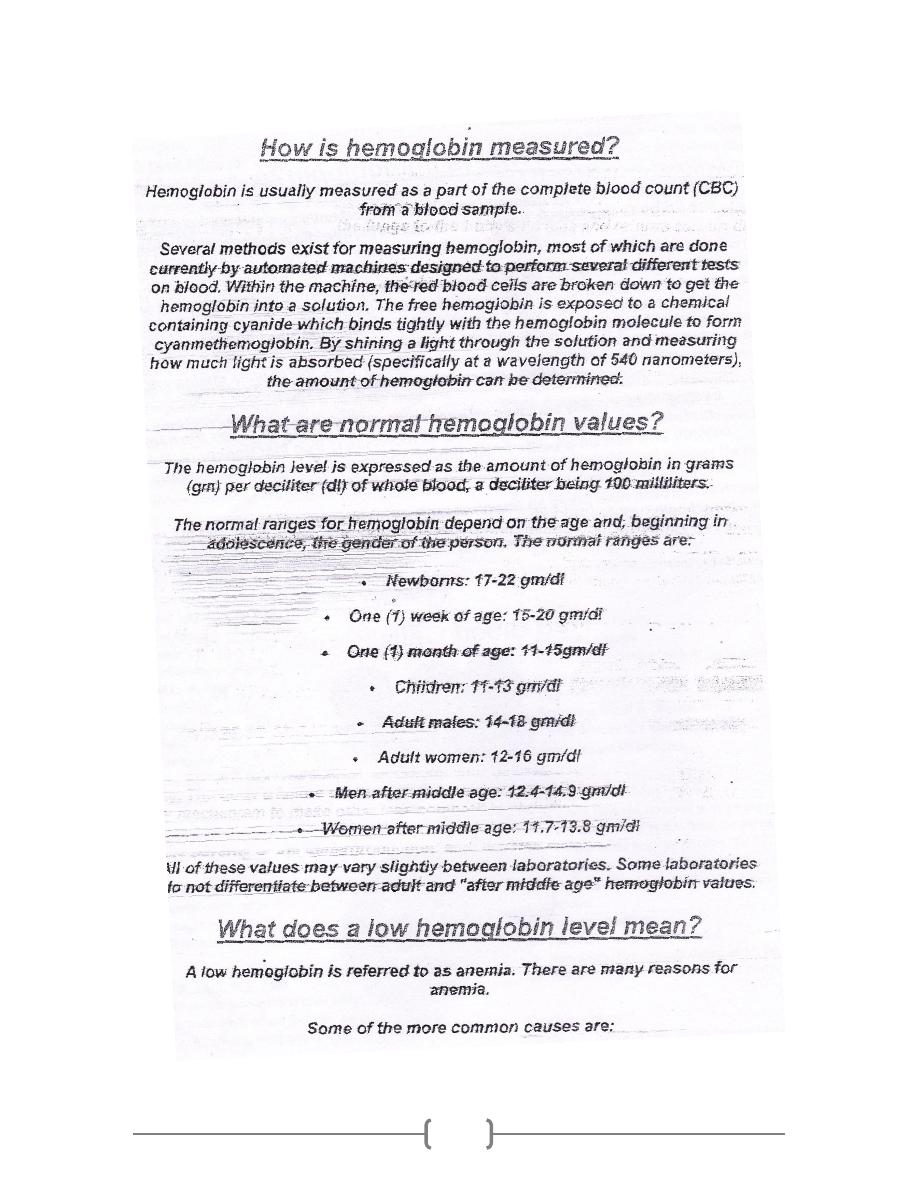

Hemoglobin

2

3

4

ESR

1

ESR stands for erythrocyte sedimentation rate. It is commonly

called a "sed rate."

It is a test that indirectly measures how much inflammation is

in the body.

How the Test is performed

A blood sample is needed. For information on how this is

done, see:

Venipuncture

The blood sample is sent to a lab. The test measures how fast

red blood cells called erythrocytes fall to the bottom of a tall,

thin tube.

How to Prepare for the Test

There are no special preparations needed.

How the Test Will Feel

When the needle is inserted to draw blood, some people feel

moderate pain, while others feel only a prick or stinging

sensation. Afterward, there may be some throbbing.

Why the Test is performed

A "sed rate" is often ordered for someone who is having

unexplained fevers, certain types of arthritis, muscle

symptoms, or other vague symptoms that cannot be explained.

Once a diagnosis has been made, this test may be used to mon-

itor whether the illness is becoming more active or flaring up.

This test can be used to monitor inflammatory diseases or

cancer. It is a screening test, which means it cannot be used to

diagnose a specific disorder.

However, it is useful for detecting and monitoring:

Autoimmune disorders

Certain forms of arthritis

Inflammatory diseases that cause vague symptoms

Tissue death

Tuberculosis

Normal Results

Adults (Westergren method):

Men under 50 years old: less than 15 mm/hr

Men over 50 years old: less than 20 mm/hr

Women under 50 years old: less than 20 mm/hr

Women over 50 years old: less than 30 mm/hr

Children (Westergren method):

Newborn: 0 to 2 mm/hr

Newborn to puberty: 3 to 13 mm/hr

Note: mm/hr. = millimeters per hour

Normal value ranges may vary slightly among different

laboratories. Talk to your doctor about the meaning of your

specific test results.

What Abnormal Results Mean

Although it can help diagnose some illnesses, an abnormal

ESR does not prove that you have a certain condition. Other

tests are almost always needed

An increased ESR rate may be due to:

Anemia

Cancers such as lymphoma or

multiple myeloma

Kidney disease

Pregnancy

Thyroid disease

The immune system helps protect the body against harmful

substances. In

autoimmune disorder

is a condition that occurs

when the immune system mistakenly attacks and destroys

healthy body tissue. ESR is often higher than normal in people

with an autoimmune disorder.

Common autoimmune disorders include:

o

Lupus

o

Rheumatoid arthritis in adults

or

children

Very high ESR levels occur with less common

autoimmune disorders, including:

o Allergic vasculitis

o

Giant cell arteritis

o Hyperfibrinogenemia (increased

fibrinogen

levels in

the blood)

o

Macroglobulinemia - primary

o

Necrotizing vasculitis

o

Polymyalgia rheumatica

An increased ESR rate may be due to some infections,

including:

o Body-wide (systemic) infection

o

Bone infections

o

Infection of the heart or heart valves

o

Rheumatic fever

o Severe skin infections, such as

erysipelas

o Tuberculosis

Lower-than-normal levels occur with:

Congestive heart failure

Hyperviscosity

Hypofibrinogenemia

(decreased fibrinogen levels)

Low plasma protein (due to liver or kidney disease)

Polycythemia

Sickle cell anemia

Risks

Veins and arteries vary in size from one patient to another and

from one side of the body to the other. Obtaining a blood

sample from some people may be more difficult than from

others.

Other risks associated with having blood drawn are slight but

may include:

Excessive bleeding

Fainting or feeling light-headed

Hematoma (blood accumulating under the skin)

Infection (a slight risk any time the skin is broken)

Alternative Names

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; Sed rate; Sedimentation rate

ESR

2

Procedure 14-8: perform an ESR using the

westergren method

Theory and Rationale

A well-mixed anticoagulated blood sample is drawn into a

Westergren tube and left upright for an hour. The full length

of red cells from the top of the column in that hour is the

erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or sed rate. Reference ranges

vary among institutions, but the generally accepted reference

range is 0 to 20 mm/hr for women and 0 to 15 mm/hr for men.

Materials

ESR kit (Sediplast ESR System)

EDTA anticoagulated patient blood sample

gauze square

disposable gloves

biohazard waste container

sharps container

patient record

Competency

(Conditions) With the necessary materials, you will be able to

(Task) demonstrate performing an ESR using the Westergren

method (Standards) correctly in one hour.

1) Wash your hands.

2) Gather equipment and supplies.

3) Greet and identify the patient and escort him or her to the

laboratory draw area. Explain the procedure.

4) Wash your hands and put on your gloves and PPE.

5) Perform a venipuncture and obtain an EDTA-

anticoagulated tube of patient blood; gently mix the

anticoagulation tube for 2 minutes.

6) Remove the stopper on the prefilled vial included with the

Sediplast ESR System. Fill the vial to the indicated line

with blood.

7) Replace the stopper and invert several times to mix.

8) Insert the pipette through the pierceable stopper, and push

down until the pipette touches the bottom of the vial. The

pipette will autozero the blood and any excess with flow

into the closed reservoir compartment.

9) Let the pipette stand for one hour, then read the numerical

results of the ESR.

10) Dispose of all used sharps and biohazardous waste in the

appropriate containers.

11) Remove the disposable gloves and discard appropriately.

Wash your hands.

12) Document the sed rate in mm/hr on the laboratory

requisition or other designated area of the chart.

Patient Education

Instruct the patient beforehand in the general procedure. Do

not promise the patient that the procedure will not hurt. It is

more tactful to say that it might feel like a “brief sting.”Let the

patient know when the actual puncture is about to happen. As

necessary, provide information about how long the results will

take and how they will be transmitted to the patient.

Charting Example

Sometimes charting may not be required for phlebotomy

procedures because laboratory processing documentation is

sufficient. If charting is required, it might look like this:

08/25/XX 7:30 a.m. Pt anxious about phlebotomy

procedure. General explanations given before each step. Pt

voiced concern over the amount of pain she would

experience and that her veins were hard to get blood from.

Venous specimen obtained for a CBC, Na, K, and Cl with

appropriate tubes. Pt held pressure gauze onsite, site was

bandaged, and pt was instructed to leave the bandage in

place for 15 minutes. Pt escorted to the exit. Robert Larin,

RMA (AMT)

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

The ESR is a simple non-specific screening test that indirectly

measures the presence of inflammation in the body. It reflects

the tendency of red blood cells to settle more rapidly in the

face of some disease states, usually because of increases in

plasma fibrinogen, immunoglobulins, and other acute-phase

reaction proteins. Changes in red cell shape or numbers may

also affect the ESR.

Method

When anticoagulated whole blood is allowed to stand in a

narrow vertical tube for a period of time, the RBCs – under the

influence of gravity - settle out from the plasma. The rate at

which they settle is measured as the number of millimeters of

clear plasma present at the top of the column after one hour

(mm/hr).

The Wintrobe sedimentation rack

ESR

3

There are two main methods used to measure the ESR: the

Westergren method and the Wintrobe Method. Each method

produces slightly different results. Most laboratories use the

Westergren method.

Westergren method:

The Westergren method requires collecting 2 ml of venous

blood into a tube containing 0 .5 ml of sodium citrate. It

should be stored no longer than 2 hours at room temperature

or 6 hours at 4 °C. The blood is drawn into a Westergren-Katz

tube to the 200 mm mark. The tube is placed in a rack in a

strictly vertical position for 1 hour at room temperature, at

which time the distance from the lowest point of the surface

meniscus to the upper limit of the red cell sediment is

measured. The distance of fall of erythrocytes, expressed as

millimeters in 1 hour, is the ESR.

Wintrobe method:

The Wintrobe method is performed similarly except that the

Wintrobe tube is smaller in diameter than the Westergren tube

and only 100 mm long. EDTA anticoagulated blood without

extra diluent is drawn into the tube, and the rate of fall of red

blood cells is measured in millimeters after 1 hour. The

shorter column makes this method less sensitive than the

Westergren method because the maximal possible abnormal

value is lower. However, this method is more practical for

demonstration purposes.

Average values in healthy men are: <15mm/hr; in healthy

females, they are somewhat higher: <20mm. The values are

slightly higher in old age, in both genders.

Theoretical considerations

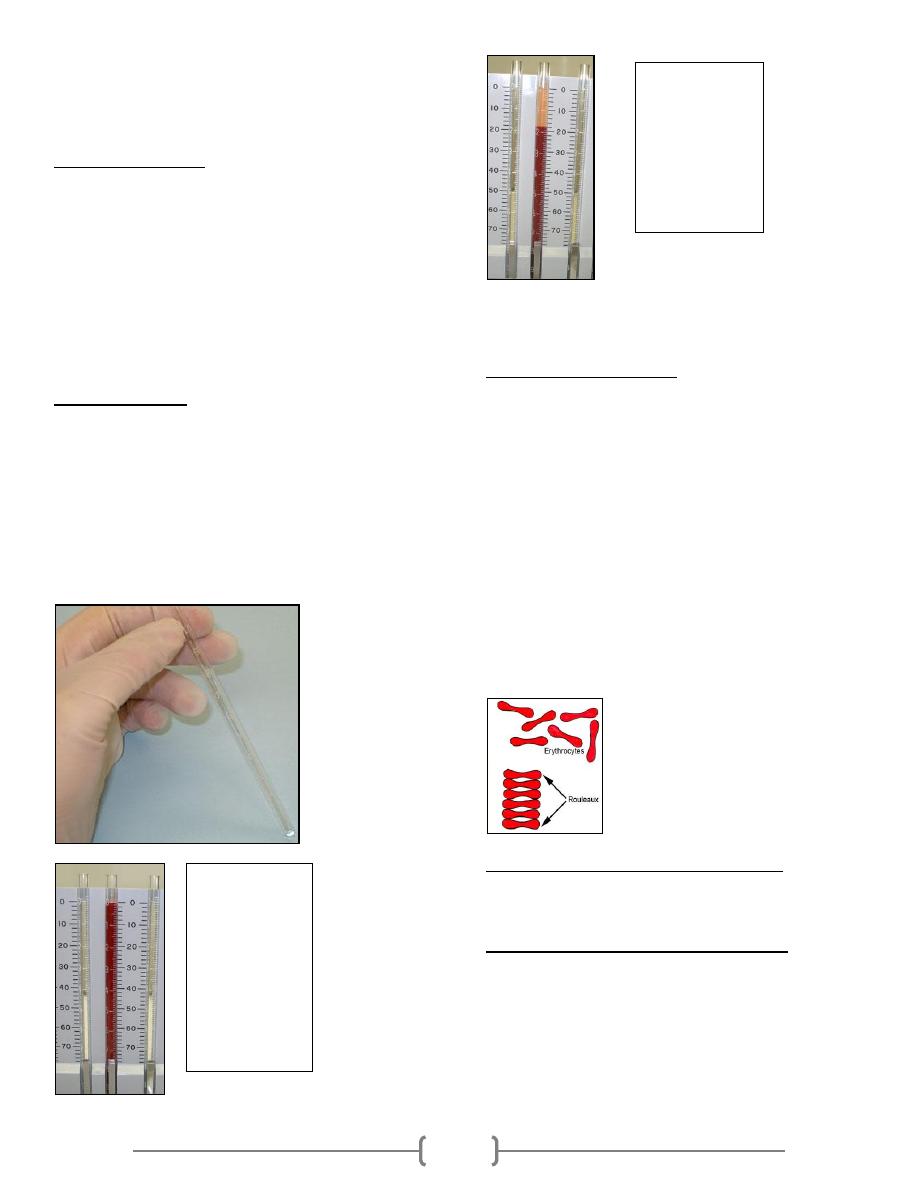

The RBCs sediment because their density is greater than that

of plasma; this is particularly so, when there is an alteration in

the distribution of charges on the surface of the RBC (which

normally keeps them separate form each other) resulting in

their coming together to form large aggregates known as

rouleaux.

Rouleaux formation is determined largely by increased levels

of plasma fibrinogen and globulins, and so the ESR reflects

mainly changes in the plasma proteins that accompany acute

and chronic infections, some tumors and degenerative

diseases. In such situations, the ESR values are much greater

than 20mm/hr. Note that the ESR denotes merely the presence

of tissue damage or disease, but not its severity; it may be used

to follow the progress of the diseased state, or monitor the

effectiveness of treatment.

Some interferences which increase ESR:

Increased level of fibrinogen, gamma globulins.

Technical factors: tilted ESR tube, high room temperature.

Some interferences which decrease ESR:

Abnormally shaped RBC (sickle cells, spherocytosis).

Technical factors: short ESR tubes, low room temperature,

delay in test performance (>2 hours), clotted blood sample,

excess anticoagulant, bubbles in tube.

Chronic inflammatory disease (collagen and vascular diseases)

increases ESR.

Polycythemia decreases ESR.

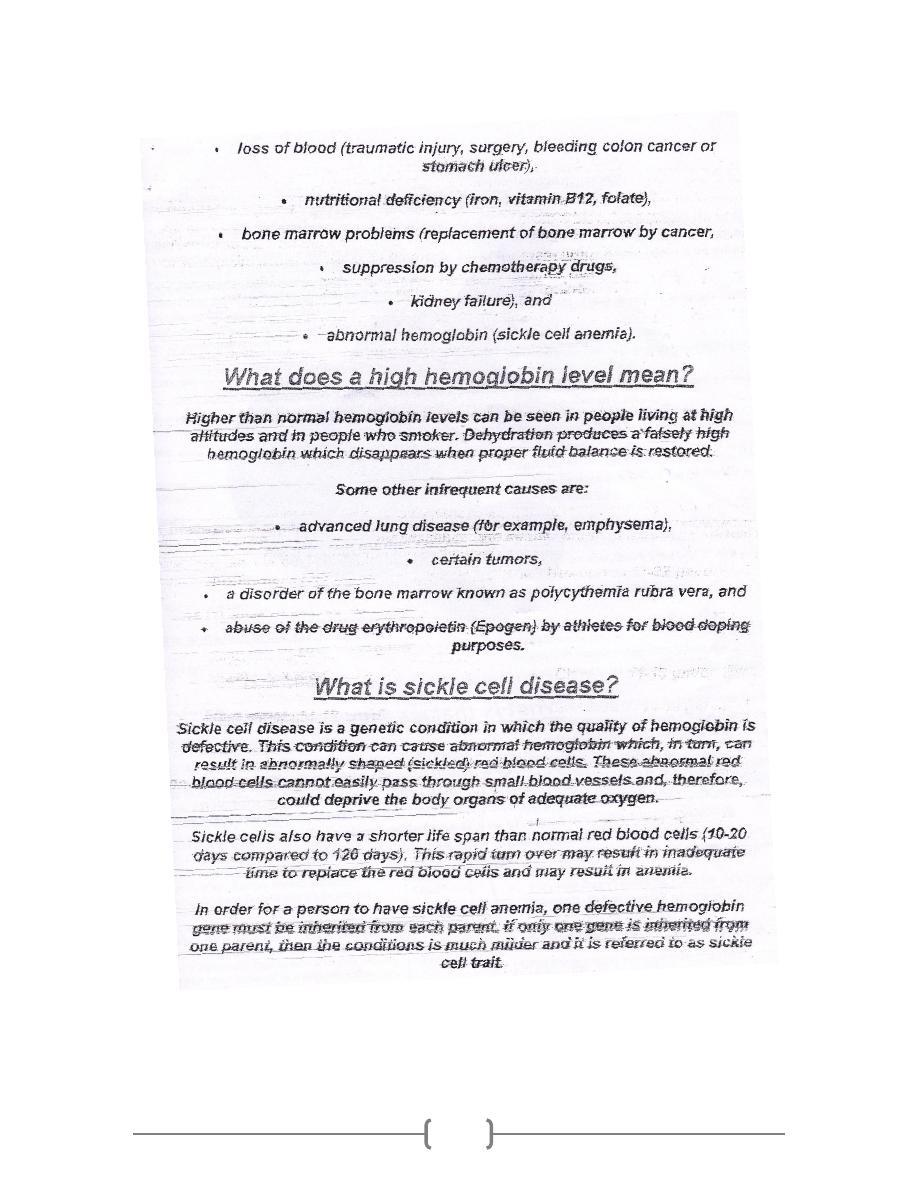

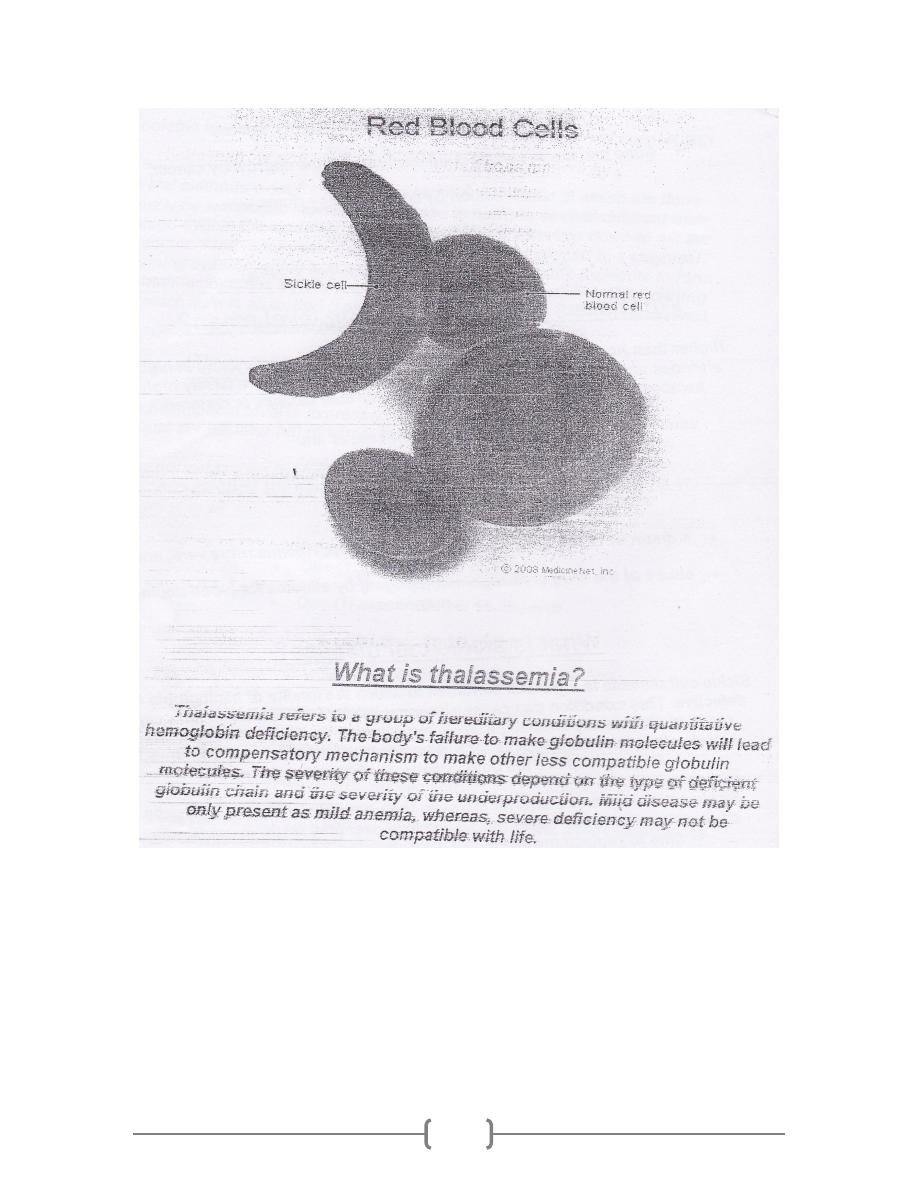

This picture

shows a rack

holding

Wintrobe

tubes, in which

anticoagulated

whole blood

has just been

added.

(Time: 0)

Red blood cells

have settled,

leaving plasma

at the top of the

tube. Reading:

18 mm/hour

(Time: one

hour)

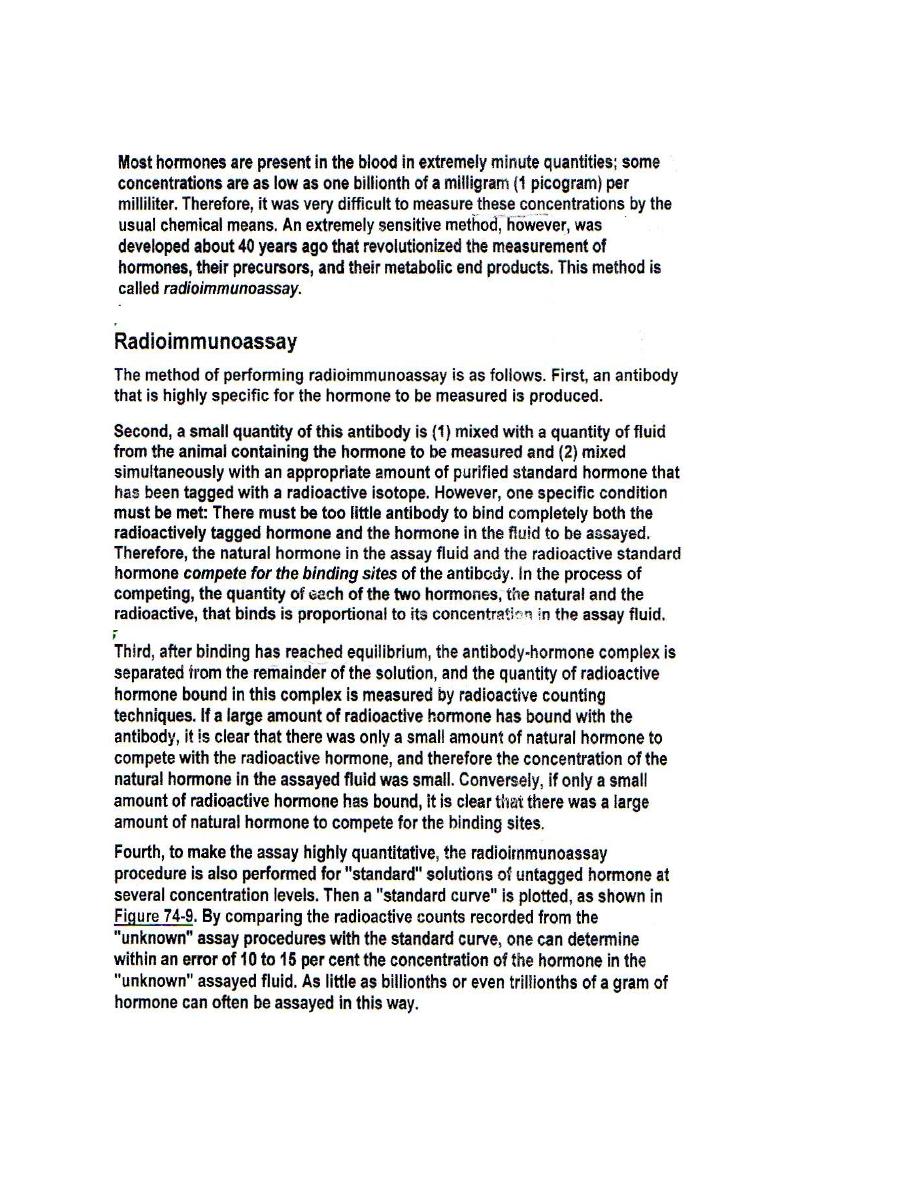

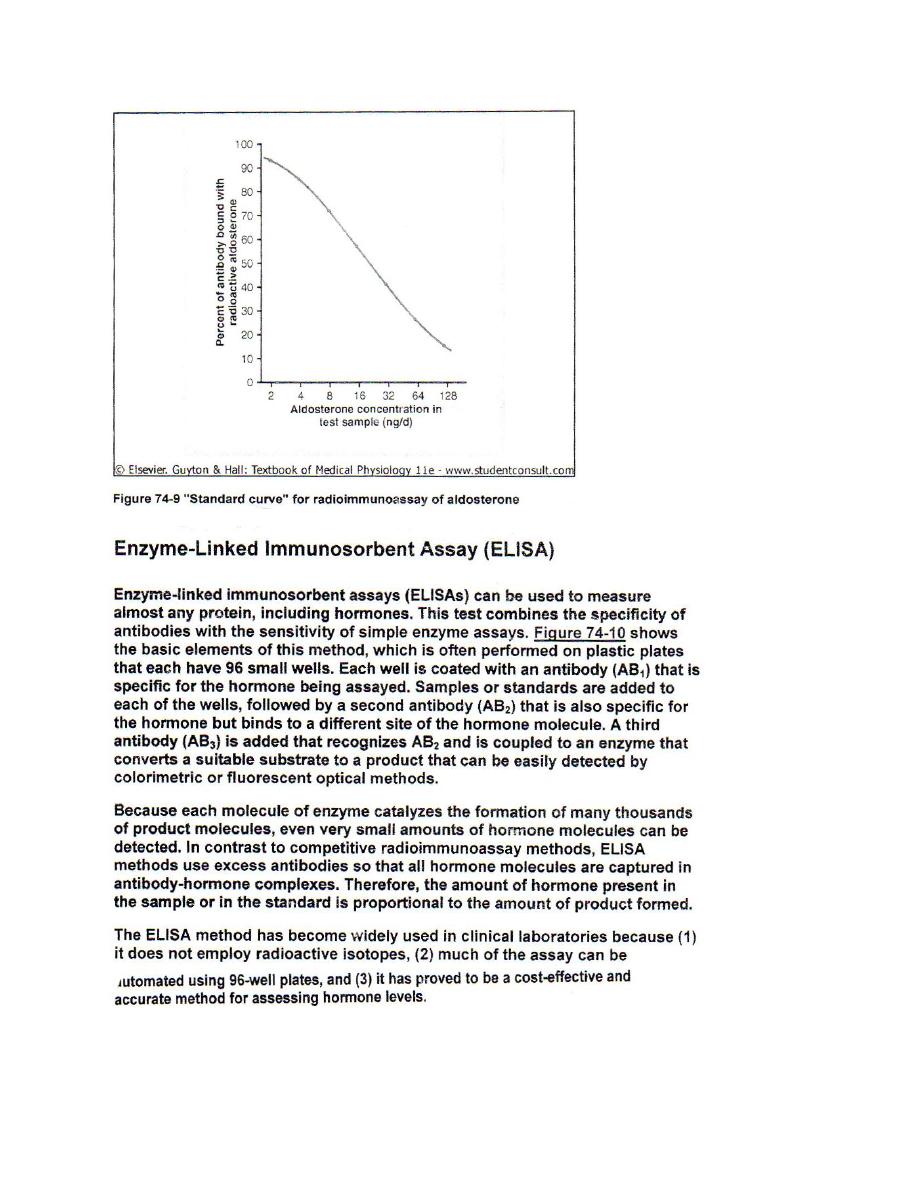

Measurement of Hormone Concentration in the Blood

1

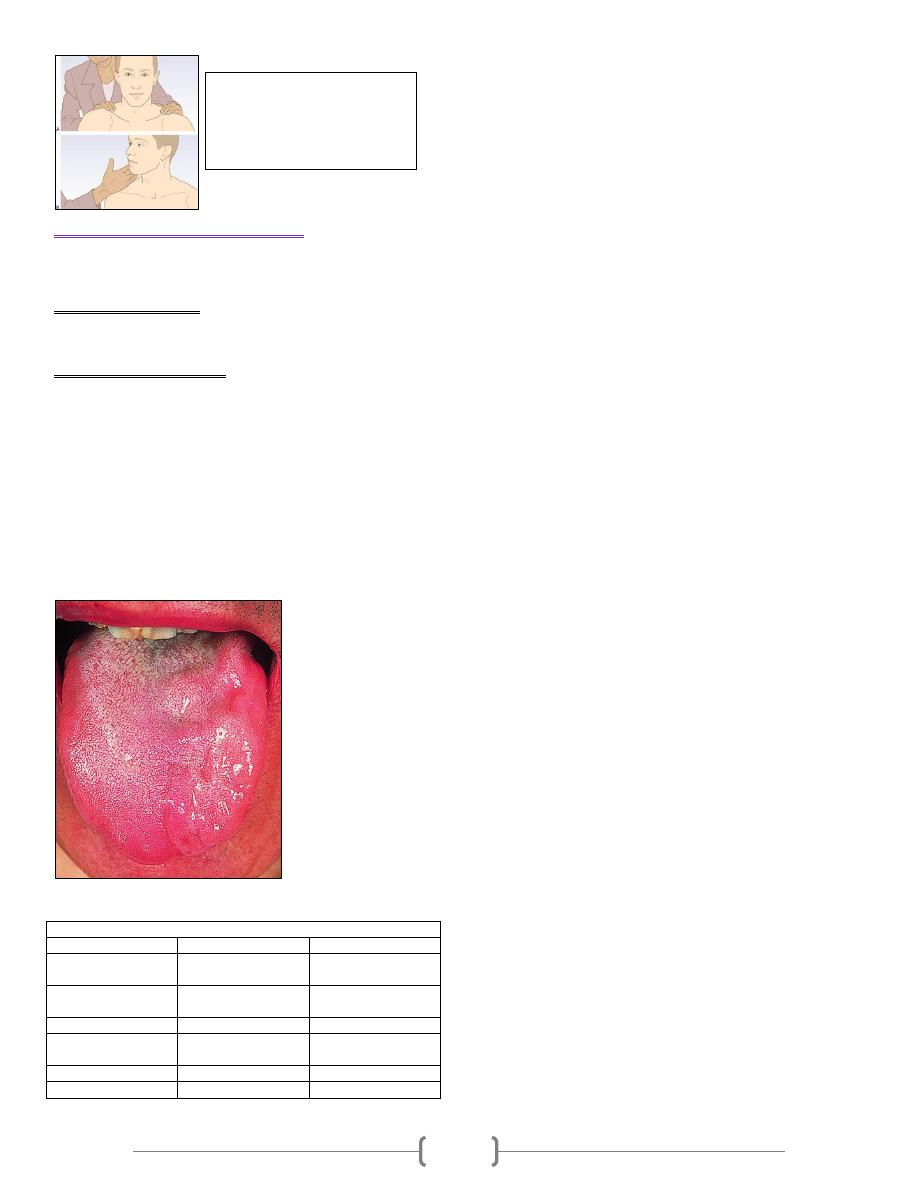

Arterial Pulse

Anatomy

As the ventricles eject blood into the arteries a pressure wave

(pulse) is transmitted and can be felt particularly where the

arteries are superficial and pass over bone. The pressure wave

travels faster than the blood. The pulse waveform depends on

the heart rate, stroke volume, peripheral resistance (especially

in the arterioles), left ventricular outflow obstruction and the

elasticity of peripheral vessels.

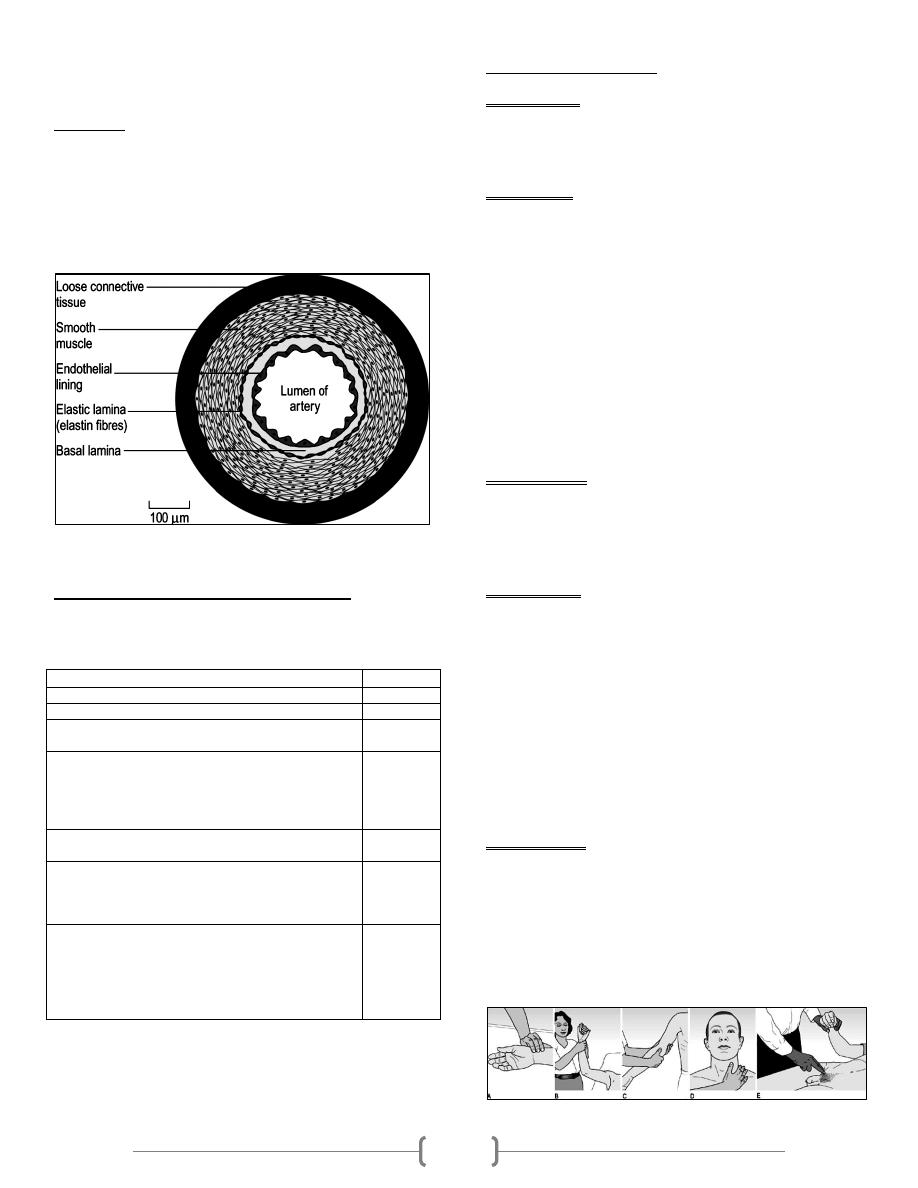

Cross-section of an artery

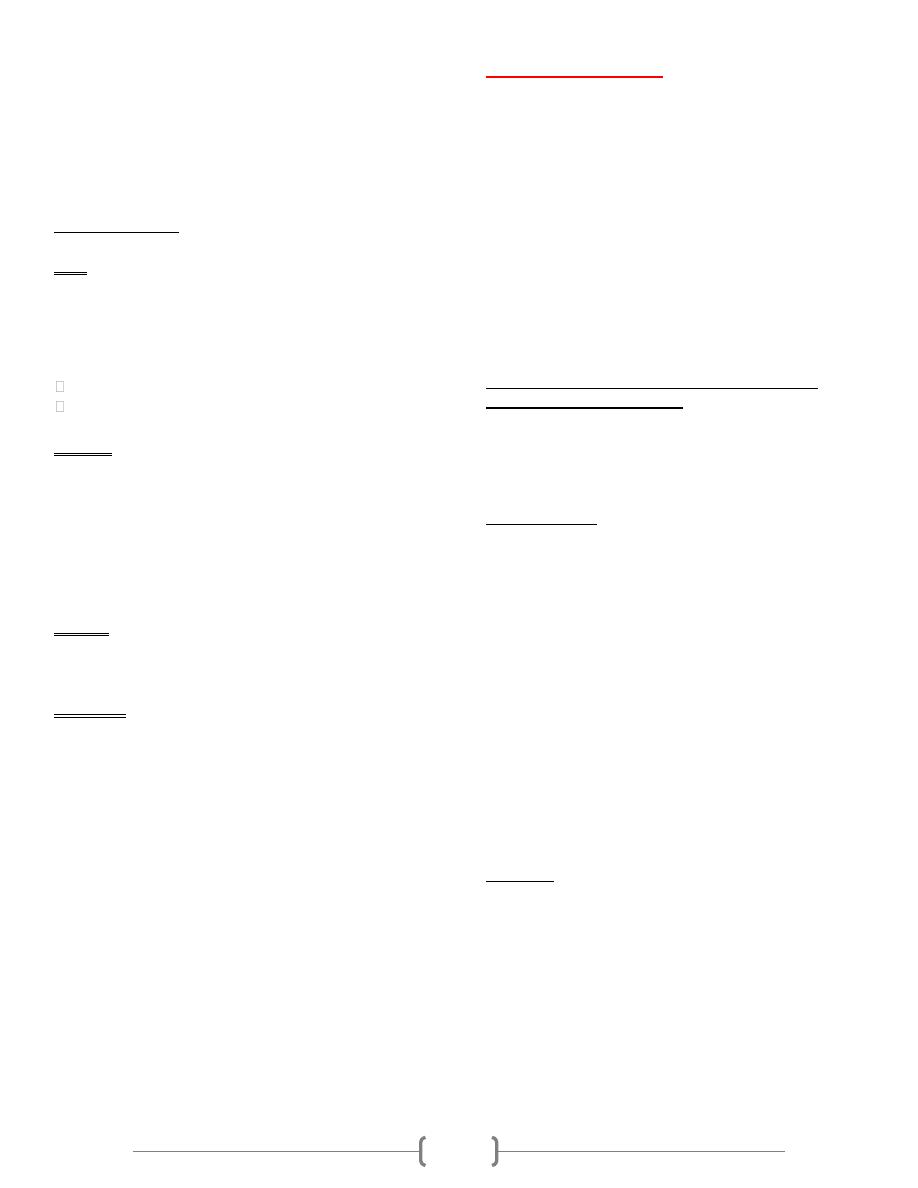

Surface markings of the arterial pulses

Important table

Use the larger (brachial, carotid or femoral) pulses to assess

the pulse volume and character and in hypotensive

States. When taking a pulse, characterize the information

according to: rate, rhythm, volume & character.

Examination sequence

Arterial pulses

If you are in any doubt about whose pulse you are feeling,

palpate your own pulse at the same time. If what you are

feeling is not synchronous with yours it is the patient's pulse.

Radial pulse

Place the pads of your three middle fingers over the right

radial artery.

Assess rate, rhythm and volume.

Count the pulse rate over 15 s and multiply by 4 to obtain

the beats per minute (bpm).

To detect a collapsing pulse, feel the pulse with the base of

your fingers, then raise the

patient's hand above his head.

Palpate both radial pulses simultaneously, assessing any

volume differences.

Palpate the femoral and radial pulse simultaneously, noting

any delay between the two and any difference in pulse

volume between them.

Brachial pulse

This artery lies deeper than the radial, medial to the biceps

tendon, so use your thumb to palpate it, with your fingers

cupped round the back of the elbow

Assess the character and volume

Carotid pulse

Explain to the patient what you are going to do. Never

assess both carotid pulses simultaneously

Ask the patient to lie semi-recumbent in case you induce a

reflex bradycardia.

Gently place the tip of your thumb between the larynx and

the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle

Listen for bruits over both femoral arteries, using the

diaphragm of your stethoscope.

Listen for bruits over both carotid arteries, using the

diaphragm of your stethoscope while the patient holds his

breath

Femoral pulse

Ask the patient to lie down and explain what you are going

to do.

With your fingers extended, place the pads of your index

and middle fingers over the femoral artery

Check for radiofemoral delay.

Listen for bruits over both femoral arteries, using the

diaphragm of your stethoscope.

Surface marking

Artery

At the wrist, lateral to the flexor carpi radialis tendon

Radial

In the antecubital fossa, medial to the biceps tendon

Brachial

At the angle of the jaw, anterior to the

sternocleidomastoid muscle

Carotid

Just below the inguinal ligament, midway between the

anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic

symphysis (the mid-inguinal point). It is immediately

lateral to the femoral vein and medial to the femoral

nerve

Femoral

Lies posteriorly in relation to the knee joint, at the level

of the knee crease, deep in the popliteal fossa

Popliteal

Located 2 cm below and posterior to the medial

malleolus, where it passes beneath the flexor

retinaculum between flexor digitorum longus and

flexor hallucis longus

Posterial

Tibial

Passes lateral to the tendon of extensor hallucis longus

and is best felt at the proximal extent of the groove

between the first and second metatarsals. It may be

absent or abnormally sited in 10% of normal subjects,

sometimes being 'replaced' by a palpable perforating

peroneal artery

Dorsalis

Pedis

2

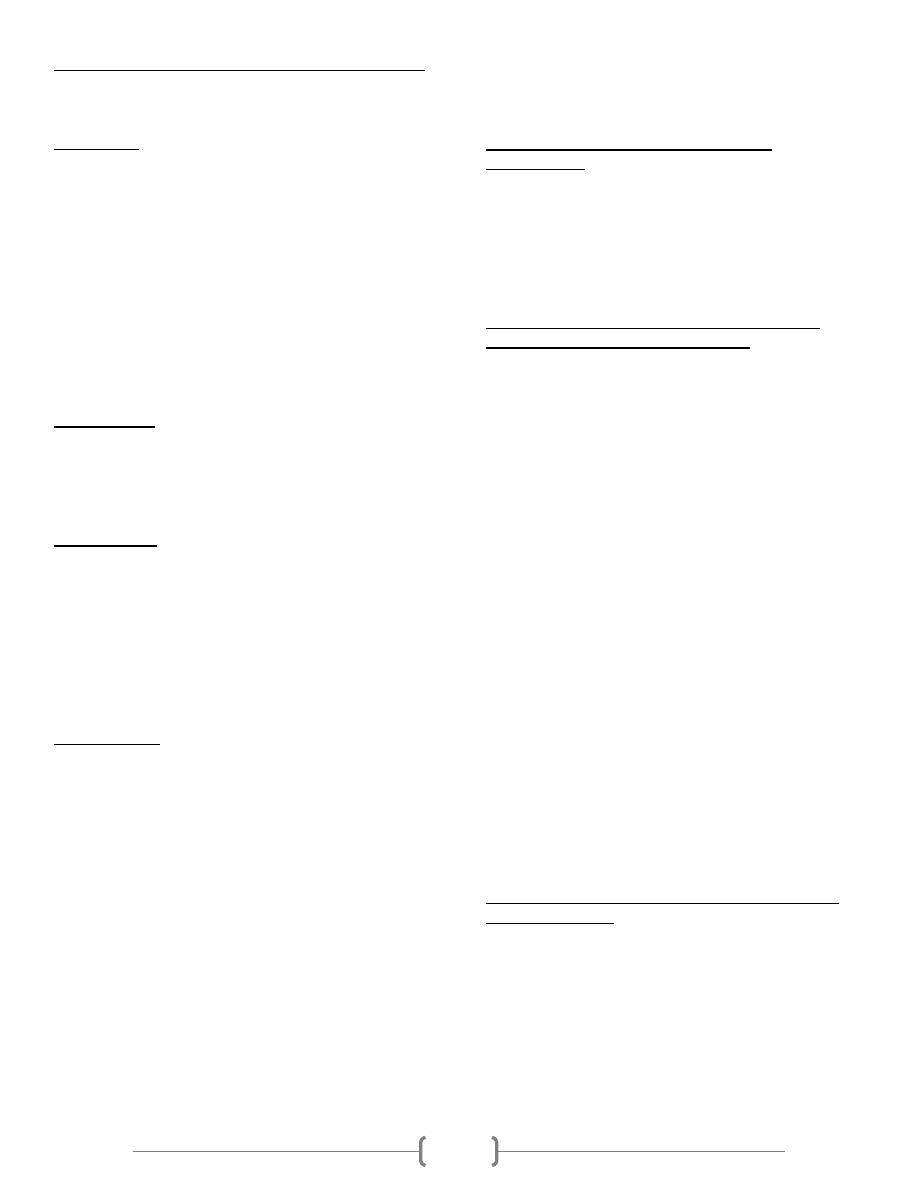

The radial, brachial and carotid pulses. (A) Locating

and palpating the radial pulse. (B) Feeling for a collapsing

radial pulse. (C) Assessing the brachial pulse with your

thumb. (D) Locating the carotid pulse with your thumb.

(E) Examining the femoral artery, while simultaneously

checking for radiofemoral delay.

Normal findings

Rate

Assess the pulse rate in the clinical context. A pulse rate

of 40 bpm can be normal in a fit, young adult, whereas a

pulse rate of 65 bpm may be abnormally low in the setting

of acute heart failure. Resting heart rate is normally 60-

100 bpm.

Bradycardia is a pulse rate <60 bpm.

Tachycardia is a pulse rate of >100 bpm.

Rhythm

Normal rhythm is regular; it is called sinus rhythm, as it

originates from the sinoatrial (SA) nodeIt varies slightly

with the respiratory cycle, mediated by the vagus nerve, and

is most pronounced in children, young adults or athletes

(sinus arrhythmia). During inspiration, parasympathetic

tone falls and the heart rate quickens; on expiration, the

heart rate falls

Volume

Volume means the degree of pulsation and reflects the pulse

pressure.

Character

Character means the waveform or shape of the arterial pulse.

Body Temperature:

Measurement of body temperature is used routinely in the

clinical work. It varies considerably under many physiological

and pathological conditions. The normal body temperature

ranges between 36.6-37.2 ºC. Circadian variation of 0.5 ºC

occurs and the lowest record is in the early morning.

Temperature variations occur as shown below:

Hypothermia below 35 ºC

Subnormal below 36.6 ºC

Febrile above 37.2 ºC

Hyperpyrexia above 41.6 ºC

The rectal temperature is usually about 0.5 ºC higher than the

mouth and mouth temperature in turn 0.5 ºC higher than that

of axilla.

Body Temperature Is Controlled by Balancing Heat

Production Against Heat Loss:

When the rate of heat production in the body is greater than

the rate at which heat is being lost, heat builds up in the body

and the body temperature rises. Conversely, when heat loss is

greater, both body heat and body temperature decrease.

Heat Production:

We discuss the different factors that determine the rate of heat

production, called the metabolic rate of the body. The most

important of these factors are:

(1) basal rate of metabolism of all the cells of the body;

(2) extra rate of metabolism caused by muscle activity,

including muscle contractions caused by shivering;

(3) extra metabolism caused by the effect of thyroxine (and, to

a less extent, other hormones, such as growth hormone ) on

the cells;

(4) extra metabolism caused by the effect of epinephrine,

norepinephrine, and sympathetic stimulation on the cells;

(5) extra metabolism caused by increased chemical activity in

the cells themselves, especially when the cell temperature

increases; and

(6) extra metabolism needed for digestion, absorption, and

storage of food (thermogenic effect of food).

Heat Loss:

Most of the heat produced in the body is generated in the deep

organs, especially in the liver, brain, and heart, and in the

skeletal muscles during exercise. Then this heat is transferred

from the deeper organs and tissues to the skin, where it is lost

to the air and other surroundings. Therefore, the rate at which

heat is lost is determined almost entirely by two factors: (1)

how rapidly heat can be conducted from where it is produced

in the body core to the skin and (2) how rapidly heat can then

be transferred from the skin to the surroundings.

3

Basic Physics of How Heat Is Lost from the Skin Surface:

The various methods by which heat is lost from the skin to the

surroundings include radiation, conduction, and

evaporation, which are explained next.

(1) Radiation: in a nude person sitting inside at normal room

temperature, about 60 per cent of total heat loss is by

radiation.

Loss of heat by radiation means loss in the form of infrared

heat rays, a type of electromagnetic wave. Most infrared heat

rays that radiate from the body have wavelengths of 5 to 20

micrometers, 10 to 30 times the wavelengths of light rays. All

objects that are not at absolute zero temperature radiate such

rays. The human body radiates heat rays in all directions. Heat

rays are also being radiated from the walls of rooms and other

objects toward the body. If the temperature of the body is

greater than the temperature of the surroundings, a greater

quantity of heat is radiated from the body than is radiated to

the body.

(2) Conduction: only minute quantities of heat, about 3 per

cent, are normally lost from the body by direct conduction

from the surface of the body to solid objects, such as a chair or

a bed. Loss of heat by conduction to air, however, represents a

sizable proportion of the body's heat loss (about 15 per cent)

even under normal conditions.

(3) Convection: The removal of heat from the body by

convection air currents is commonly called heat loss by

convection. Actually, the heat must first be conducted to the

air and then carried away by the convection air currents .

A small amount of convection almost always occurs around

the body because of the tendency for air adjacent to the skin to

rise as it becomes heated. Therefore, in a nude person seated

in a comfortable room without gross air movement, about 15

per cent of his or her total heat loss occurs by conduction to

the air and then by air convection away from the body .

(4) Evaporation: When water evaporates from the body

surface, 0.58 Calorie (kilocalorie) of heat is lost for each gram

of water that evaporates. Even when a person is not sweating,

water still evaporates insensibly from the skin and lungs at a

rate of about 600 to 700 ml/day. This causes continual heat

loss at a rate of 16 to 19 Calories per hour. This insensible

evaporation through the skin and lungs cannot be controlled

for purposes of temperature regulation because it results from

continual diffusion of water molecules through the skin and

respiratory surfaces. However, loss of heat by evaporation of

sweat can be controlled by regulating the rate of sweating .

Evaporation Is a Necessary Cooling Mechanism at Very

High Air Temperatures. As long as skin temperature is

greater than the temperature of the surroundings, heat can be

lost by radiation and conduction. But when the temperature of

the surroundings becomes greater than that of the skin, instead

of losing heat, the body gains heat by both radiation and

conduction. Under these conditions, the only means by which

the body can rid itself of heat is by evaporation.

Therefore, anything that prevents adequate evaporation when

the surrounding temperature is higher than the skin

temperature will cause the internal body temperature to rise.

Regulation of Body Temperature-Role of the

Hypothalamus:

The temperature of the body is regulated almost entirely by

nervous feedback mechanisms, and almost all these operate

through temperature-regulating centers located in the

hypothalamus. For these feedback mechanisms to operate,

there must also be temperature detectors to determine when

the body temperature becomes either too high or too low.

Role of the Anterior Hypothalamic-Preoptic Area in

Thermostatic Detection of Temperature:

Experiments have been performed in which minute areas in

the brain of an animal have been either heated or cooled by

use of a thermode. This small, needle-like device is heated by

electrical means or by passing hot water through it, or it is

cooled by cold water. The principal areas in the brain where

heat or cold from a thermode affects body temperature control

are the preoptic and anterior hypothalamic nuclei of the

hypothalamus .

Using the thermode, the anterior hypothalamic-preoptic area

has been found to contain large numbers of heat-sensitive

neurons as well as about one third as many cold-sensitive

neurons. These neurons are believed to function as

temperature sensors for controlling body temperature. The

heat-sensitive neurons increase their firing rate 2- to 10-fold in

response to a 10°C increase in body temperature. The cold-

sensitive neurons, by contrast, increase their firing rate when

the body temperature falls .

When the preoptic area is heated, the skin all over the body

immediately breaks out in a profuse sweat, while the skin

blood vessels over the entire body become greatly dilated.

This is an immediate reaction to cause the body to lose heat,

thereby helping to return the body temperature toward the

normal level. In addition, any excess body heat production is

inhibited. Therefore, it is clear that the hypothalamic-preoptic

area has the capability to serve as a thermostatic body

temperature control center.

Detection of Temperature by Receptors in the Skin and

Deep Body Tissues:

Although the signals generated by the temperature receptors of

the hypothalamus are extremely powerful in controlling body

temperature, receptors in other parts of the body play

additional roles in temperature regulation. This is especially

true of temperature receptors in the skin and in a few specific

deep tissues of the body .

It will be recalled from the discussion of sensory receptors that

the skin is endowed with both cold and warmth receptors.

There are far more cold receptors than warmth receptors-in

4

fact, 10 times as many in many parts of the skin. Therefore,

peripheral detection of temperature mainly concerns detecting

cool and cold instead of warm temperatures .

When the skin is chilled over the entire body, immediate

reflex effects are invoked and begin to increase the

temperature of the body in several ways:

(1) by providing a strong stimulus to cause shivering resultant

increase in the rate of body heat production;

(2) by inhibiting the process of sweating, if this is already

occurring; and (3) by promoting skin vasoconstriction to

diminish loss of body heat from the skin .

Deep body temperature receptors are found mainly in the

spinal cord, in the abdominal viscera, and in or around the

great veins in the upper abdomen and thorax. These deep

receptors function differently from the skin receptors because

they are exposed to the body core temperature rather than the

body surface temperature. Yet, like the skin temperature

receptors, they detect mainly cold rather than warmth. It is

probable that both the skin and the deep body receptors are

concerned with preventing hypothermia-that is, preventing

low body temperature .

Posterior Hypothalamus Integrates the Central and

Peripheral Temperature Sensory Signals:

Even though many temperature sensory signals arise in

peripheral receptors, these signals contribute to body

temperature control mainly through the hypothalamus. The

area of the hypothalamus that they stimulate is located

bilaterally in the posterior hypothalamus approximately at the

level of the mammillary bodies. The temperature sensory

signals from the anterior hypothalamic-preoptic area are also

transmitted into this posterior hypothalamic area. Here the

signals from the preoptic area and the signals from elsewhere

in the body, are combined and integrated to control the heat-

producing and heat-conserving reactions of the body.

Neuronal Effector Mechanisms That Decrease or Increase

Body Temperature:

When the hypothalamic temperature centers detect that the

body temperature is either too high or too low, they institute

appropriate temperature-decreasing or temperature-increasing

procedures. The reader is probably familiar with most of these

from personal experience, but special features are the

following:

A-Temperature-Decreasing Mechanisms When the Body

Is Too Hot:

The temperature control system uses three important

mechanisms to reduce body heat when the body temperature

becomes too great :

1. Vasodilation of skin blood vessels. In almost all areas of the

body, the skin blood vessels become intensely dilated. This is

caused by inhibition of the sympathetic centers in the posterior

hypothalamus that cause vasoconstriction. Full vasodilation

can increase the rate of heat transfer to the skin as much as

eightfold .

2. Sweating. The effect of increased body temperature to cause

sweating, which shows a sharp increase in the rate of

evaporative heat loss resulting from sweating when the body

core temperature rises above the critical level of 37°C

(98.6°F). An additional 1°C increase in body temperature

causes enough sweating to remove 10 times the basal rate of

body heat production .

3. Decrease in heat production. The mechanisms that cause

excess heat production, such as shivering and chemical

thermogenesis, are strongly inhibited .

B-Temperature-Increasing Mechanisms When the Body Is

Too Cold:

When the body is too cold, the temperature control system

institutes exactly opposite procedures. They are :

1. Skin vasoconstriction throughout the body. This is caused

by stimulation of the posterior hypothalamic sympathetic

centers .

2. Piloerection. Piloerection means hairs "standing on end."

Sympathetic stimulation causes the arrector pili muscles

attached to the hair follicles to contract, which brings the hairs

to an upright stance. This is not important in human beings,

but in lower animals, upright projection of the hairs allows

them to entrap a thick layer of "insulator air" next to the skin,

so that transfer of heat to the surroundings is greatly

depressed .

3. Increase in thermogenesis (heat production). Heat

production by the metabolic systems is increased by

promoting shivering, sympathetic excitation of heat

production, and thyroxine secretion.

Concept of a "Set-Point" for Temperature Control:

It is clear that at a critical body core temperature of about

37.1°C (98.8°F), drastic changes occur in the rates of both heat

loss and heat production. At temperatures above this level, the

rate of heat loss is greater than that of heat production, so the

body temperature falls and approaches the 37.1°C level. At

temperatures below this level, the rate of heat production is

greater than that of heat loss, so the body temperature rises and

again approaches the 37.1°C level. This crucial temperature

level is called the "set-point" of the temperature control

mechanism. That is, all the temperature control mechanisms

continually attempt to bring the body temperature back to this

set-point level.

Fever: which means a body temperature above the usual range

of normal, can be caused by abnormalities in the brain itself or

by toxic substances that affect the temperature-regulating

centers. They include bacterial diseases, brain tumors, and

environmental conditions that may terminate in heatstroke .

5

Resetting the Hypothalamic Temperature-Regulating

Center in Febrile Diseases-Effect of Pyrogens:

Many proteins, breakdown products of proteins, and certain

other substances, especially lipopolysaccharide toxins released

from bacterial cell membranes, can cause the set-point of the

hypothalamic thermostat to rise. Substances that cause this

effect are called pyrogens. Pyrogens released from toxic

bacteria or those released from degenerating body tissues

cause fever during disease conditions. When the set-point of

the hypothalamic temperature-regulating center becomes

higher than normal, all the mechanisms for raising the body

temperature are brought into play, including heat conservation

and increased heat production. Within a few hours after the

set-point has been increased, the body temperature also

approaches this level .

Mechanism of Action of Pyrogens in Causing Fever-Role

of Interleukin-1: Experiments in animals have shown that

some pyrogens, when injected into the hypothalamus, can act

directly and immediately on the hypothalamic temperature-

regulating center to increase its set-point. Other pyrogens

function indirectly and may require several hours of latency

before causing their effects. This is true of many of the

bacterial pyrogens, especially the endotoxins from gram-

negative bacteria .

When bacteria or breakdown products of bacteria are present

in the tissues or in the blood, they are phagocytized by the

blood leukocytes, by tissue macrophages, and by large

granular killer lymphocytes. All these cells digest the bacterial

products and then release the substance interleukin-1-also

called leukocyte pyrogen or endogenous pyrogen-into the

body fluids. The interleukin-1, on reaching the hypothalamus,

immediately activates the processes to produce fever,

sometimes increasing the body temperature a noticeable

amount in only 8 to 10 minutes. As little as one ten-millionth

of a gram of endotoxin lipopolysaccharide from bacteria,

acting in concert with the blood leukocytes, tissue

macrophages, and killer lymphocytes, can cause fever. The

amount of interleukin-1 that is formed in response to

lipopolysaccharide to cause fever is only a few nanograms .

Several experiments have suggested that interleukin-1 causes

fever by first inducing the formation of one of the

prostaglandins, mainly prostaglandin E2, or a similar

substance, which acts in the hypothalamus to elicit the fever

reaction. When prostaglandin formation is blocked by drugs,

the fever is either completely abrogated or at least reduced. In

fact, this may be the explanation for the manner in which

aspirin reduces fever, because aspirin impedes the formation

of prostaglandins from arachidonic acid. Drugs such as aspirin

that reduce fever are called antipyretics.

Experiments:

Aim: to measure the body temperature.

Apparatus: clinical thermometer.

Procedure for the oral temperature measurement:

1. Clean the thermometer by rubbing its bulb with cotton wool

soaked in alcohol in direction towards the bulb, holding it

from the end away from the bulb with your right thumb and

index fingers.

2. Holding the thermometer from the same end, observe the level

of the indicator fluid (mercury). If the column is not easily

seen rotate the thermometer forward and backward until the

column appears easily and clearly.

3. Lower the mercury level below 35 ºC, this is best done by

sharp jerky shakes of the thermometer.

4. Insert the bulb of the thermometer under the tongue with the

mouth shut tightly while breathing through the nose.

5. Leave the thermometer in its place for 2 minutes then

withdraw it and notice the level of the indicator.

1

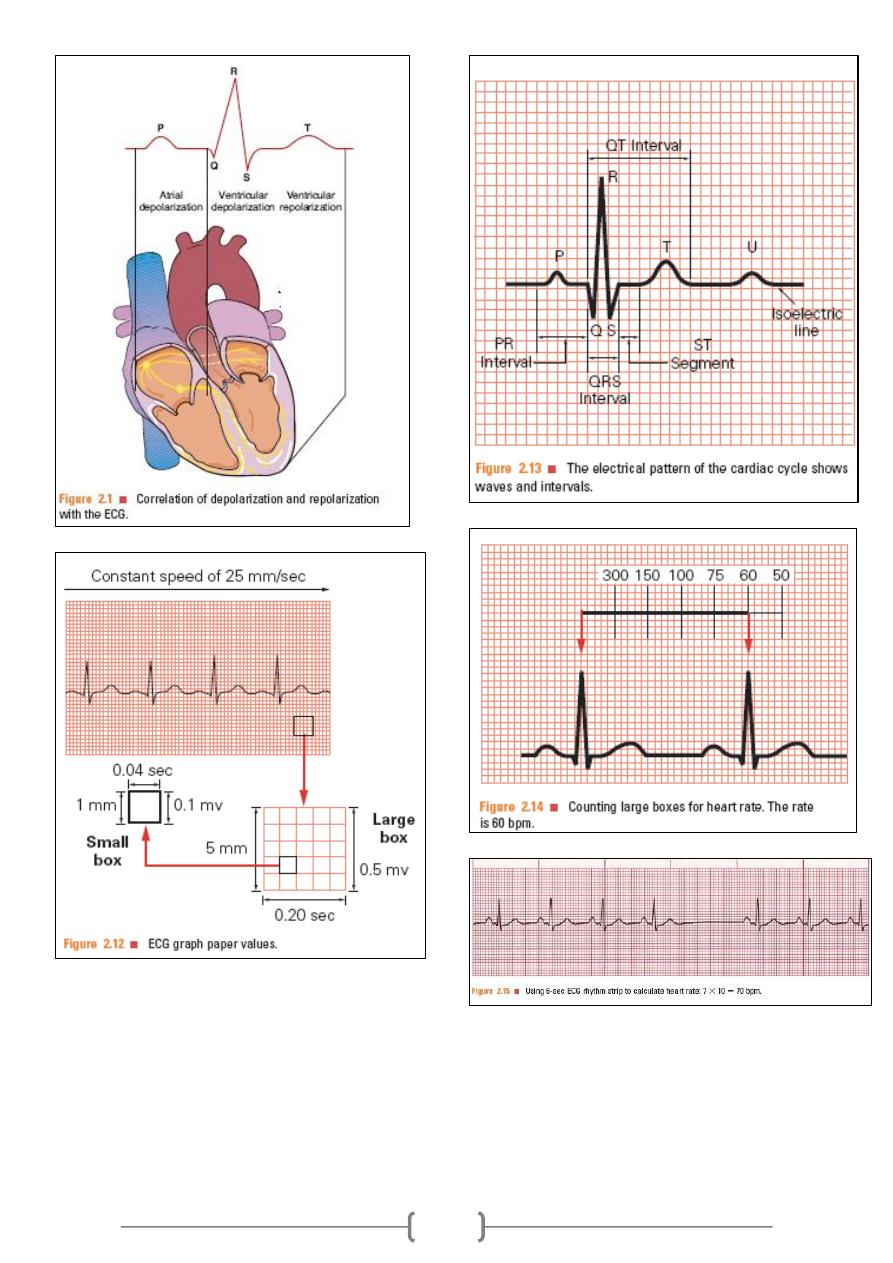

Electrical potential of the heart

The electrocardiogram (ECG):

The ECG is the recording of the electrical potential of

the heart that extend to the body surface. By placing

the electrodes of an ECG instrument on the skin

surface, you can record the waves of depolarization

and repolarization that are generated by the cardiac

muscle. The apparatus used is called the

electrocardiograph; it is formed basically of a sensitive

galvanometer and an amplifier.

A standard ECG consists of 12 leads:

3 Bipolar standard limb leads (I, II, III).

3 unipolar limb leads (aVR, aVL, aVF).

6 unipolar chest leads.

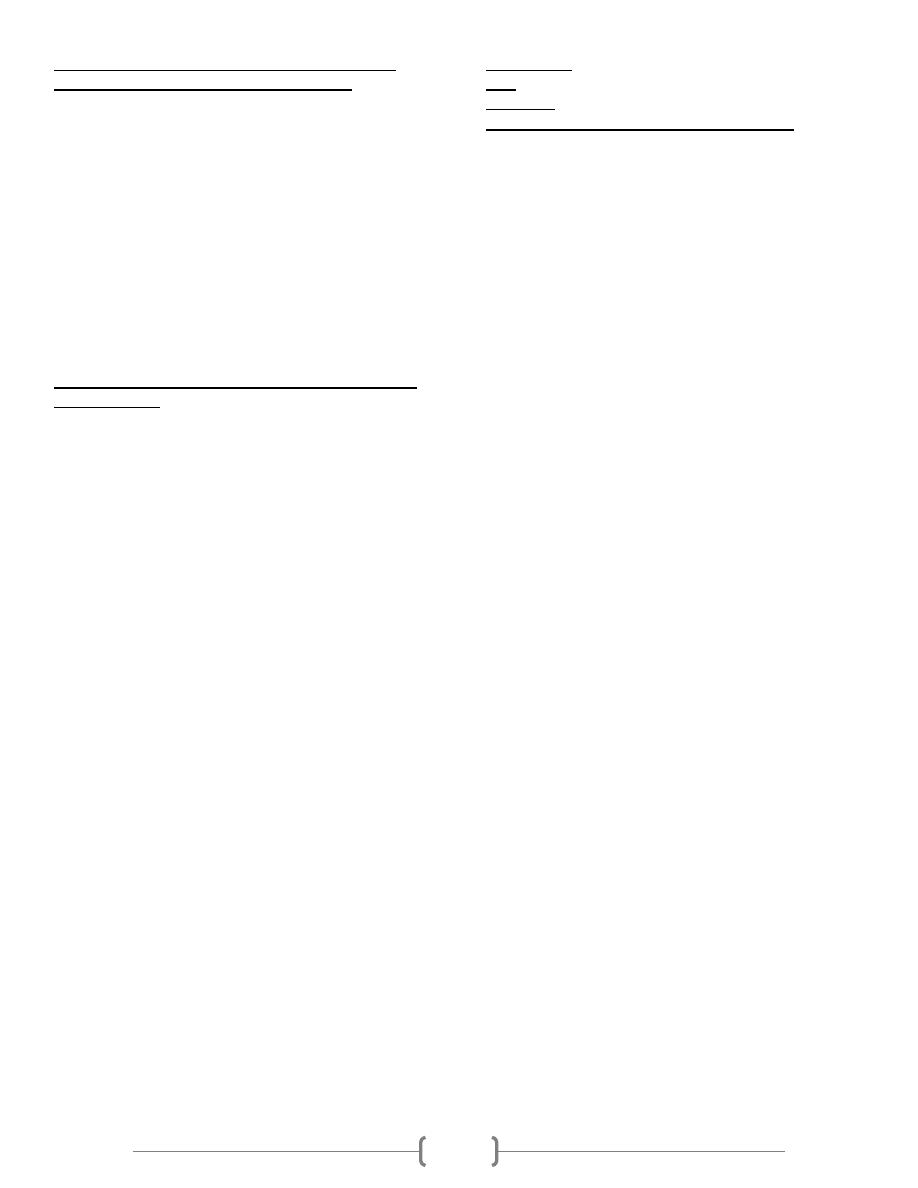

Bipolar standard limb leads (I, II, III):

These leads record the differences between the potentials in 2

limbs, by applying electrodes usually at the wrist and ankle.

The 3 standard bipolar limb leads include:

Lead I: This records the difference between the potential

in the left arm

(LA) and that in the right arm (RA).

Lead 11: This records the difference between the potential

in the right arm (RA) and that in the left leg (LL).

Lead III: This records the difference between the potential

in the left

leg (LL) and that in the left arm (LA).

Einthoven's triangle: This is an equilateral triangle, the

sides of which represent the 3 bipolar standard limb leads

while the heart lies at its centre.

Unipolar limb leads (aVR, aVL, aVF):

These measure the absolute (actual) potential at a certain

point. This is carried out by applying one electrode from the

electrocardiograph to the desired point (it is active, +ve or

exploring electrode) while the other electrode represents a

common reference point inside the instrument; it is the -ve

electrode (0 potential) i.e. the unipolar leads measure the

potential differences between active electrodes and zero

potential.

These are augmented unipolar limb leads that have magnified

amplitudes by about 50 % without any change in their

configuration, so they are called aVR, aVL and aVF (a =

augmented).

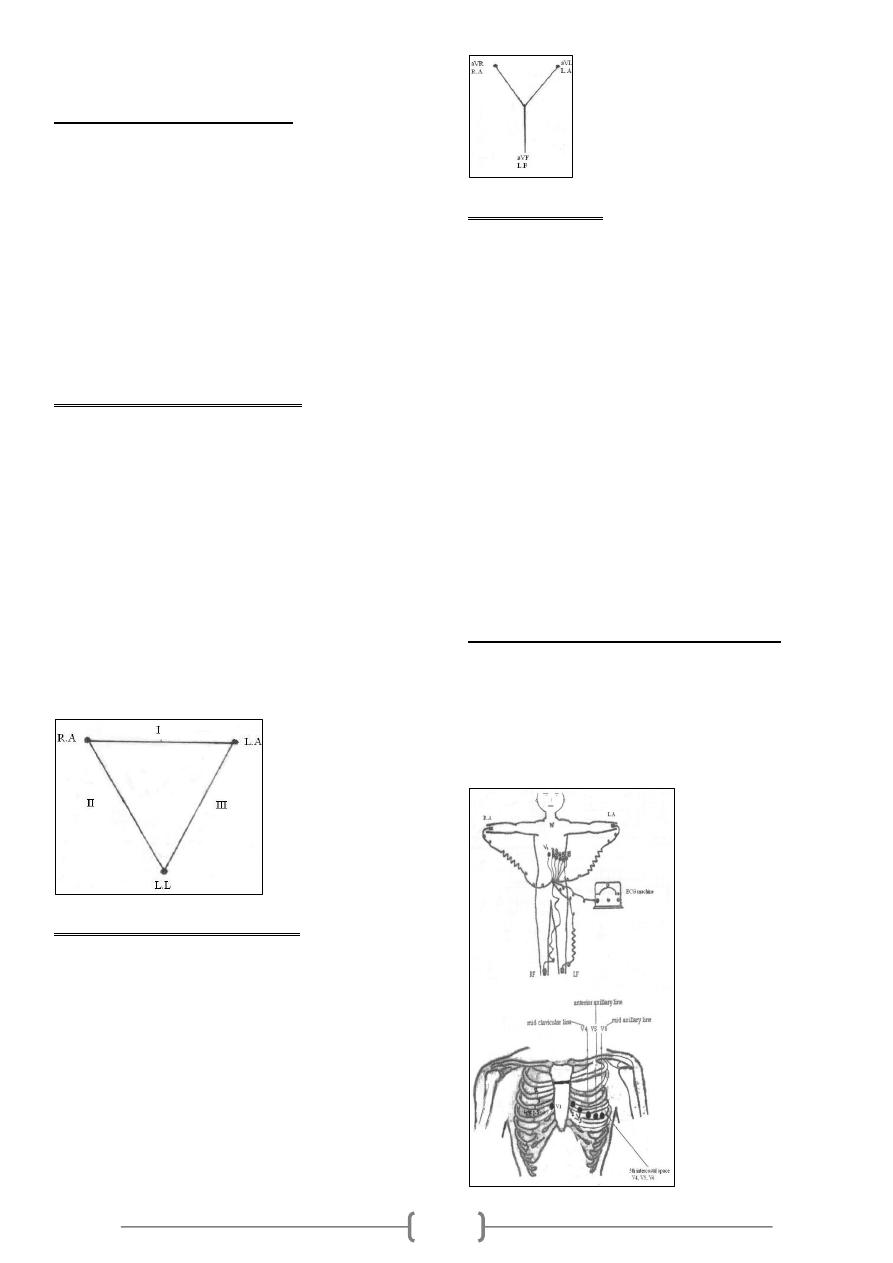

Unipolar chest leads:

Unipolar leads (precordial or chest leads) record the absolute

potential at 6 standard points on the anterior chest wall desig-

nated as V1 to V6, the locations of which are as follows:

V1: At the right margin of the sternum in the 4th right

intercostal space.

V2: At the left margin of the sternum in the 4th left

intercostal space.

V3: Midway between V2 and V4.

V4: At the left midclavicular line in the 5th intercostal

space.

V5: At the left anterior axillary line in the 5th intercostal

space.

V6: At the left midaxillary line in the 5th intercostal

space.

The precordial leads look at the heart in a horizontal plane

from the front & left sides. Leads V1 & V2 look at the right

ventricle and reflect its activity, V3 & V4 look at the

interventricular septum and reflect its activity, while leads V5

& V6 look at the left ventricle and reflect its activity.

Connections of the electrocardiograph:

By specific electrodes, the electrocardiograph is connected to

the 4 limbs and the chest at the same time. The right leg

connection is used to "earth" the subject (to minimize

interference currents). It is arranged so that an upward (+ ve)

deflection is produced when a depolarization wave is moving

toward the exploring electrode or a repolarization wave is

moving away from it, and vice versa.

2

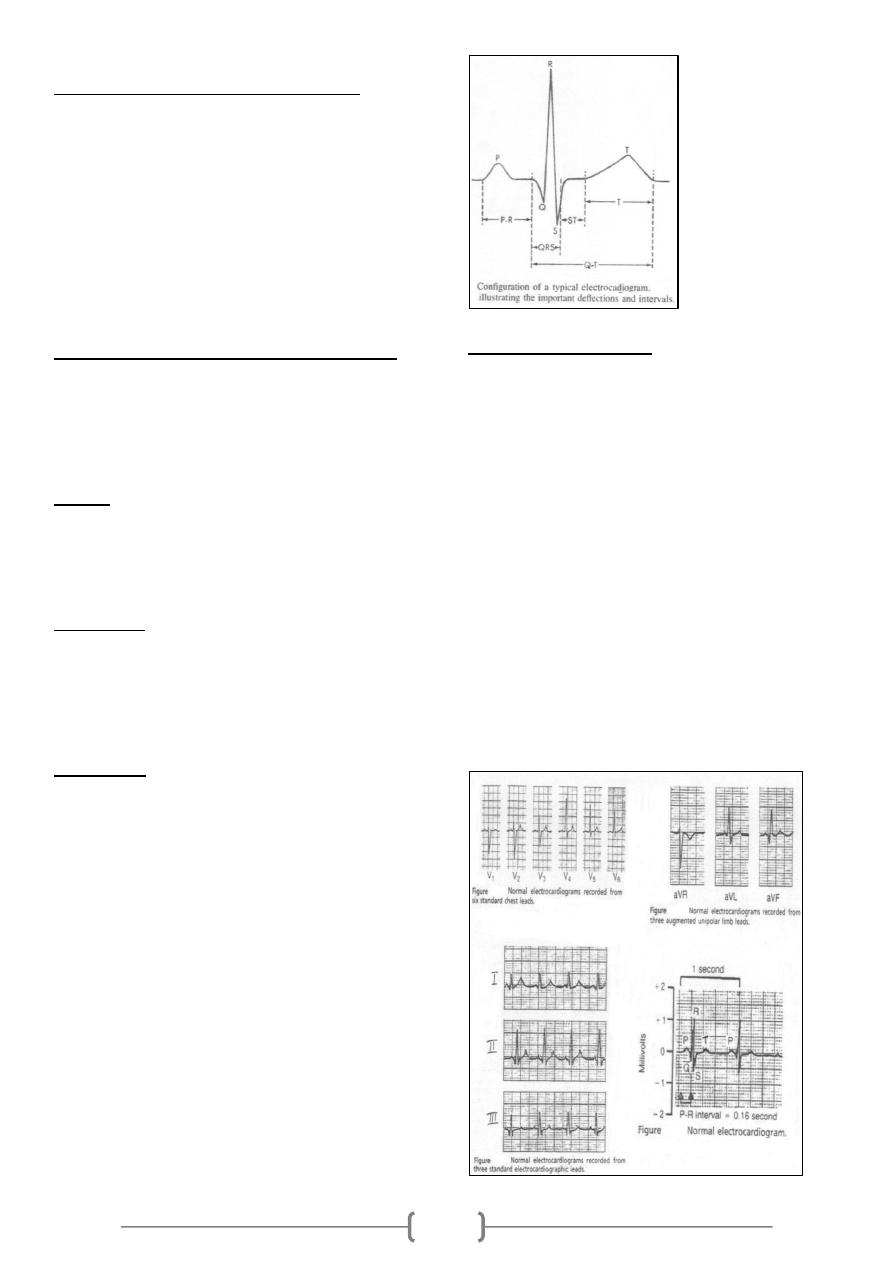

Calibration of the electrocardiograph:

The electrocardiograph is calibrated so that a change of 1 mV

upward or downward produces a deflection of 10 mm

amplitude (10 small squares; 2 large squares), thus each mm

between the horizontal lines (voltage calibration lines) equals

0.1 mV. In other words, the thin horizontal lines calibrated at

1 mm interval and the thick horizontal lines at 5 mm

intervals. The vertical lines are time calibration lines in

which duration of each mm (small square) equals 0.04

second, each inch (2.5cm) is 1 second, divided into 5 large

squares, each large square (5 small squares) represents 0.20

second as each small square = 0.04 second.

Calculation of heart rate from ECG paper:

If the heart rhythm is regular, the heart rate (HR) ran be

counted by dividing the number of large squares between two

consecutive R waves into 300 or small squares into 1500. If

the rhythm is irregular, one can multiply the number of

complexes in 6 seconds by 10.

Speed:

It is the speed at which the chart paper moves. The standard

speed is 25 mm/sec. The importance of another speed (50

mm/sec) is in case of tachycardia (e.g. HR of 180 beat/min)

to obtain a proper ECG.

Sensitivity:

It means mm deflection for 1 mV (range; 5-10-20). The

higher the sensitivity of the instrument, the more the

deflection and vise versa. The standard sensitivity is 10

mm/mV (2 large squares); in cardiomegally you must reduce

the sensitivity.

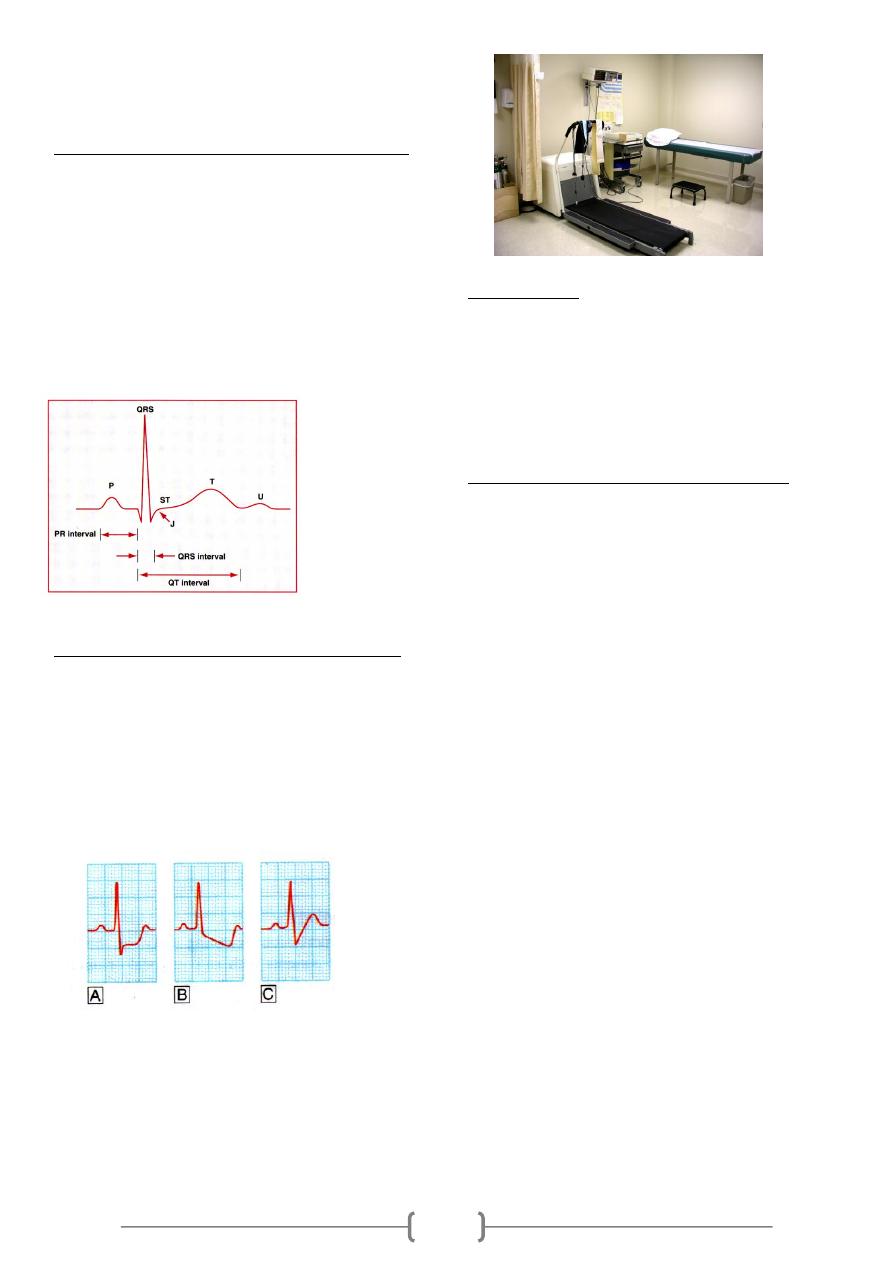

ECG waves:

ECG (Electrocardiograph) is an indirect recording of

electrical potential of the heart. Normal ECG consists of the

following waves:

P wave caused by the depolarization process of the atria;

i.e., correspond to atrial depolarization just before

contraction (i.e., not atrial contraction).

QRS complex of waves caused by the depolarization

process of the ventricles; again before ventricular

contraction (i.e., not ventricular contraction).

T wave caused by the repolarization of the ventricles; the

ventricles recover from the state of depolarization.

Duration and intervals:

P wave, duration; 0.07-0.14 seconds and not higher than 3

mm.

PR interval, This is measured from the beginning of the P

wave to the beginning of the QRS complex; to the onset of

the Q wave if there is one and to the onset of the R wave if

there is no Q wave. This interval corresponds to the time

taken for the impulse to travel from the sinus node to the

ventricular muscle. It ranges normally between 0.12- 0.21

seconds. Abnormal PR interval is either long as in first

degree heart block or short as in WPW syndrome.

QRS complex, duration; 0.06 – 0.10 seconds. Abnormal wide

QRS indicate bundle branch block.

T wave, duration; 0.25 -0.35 seconds and not taller than 10

mm in chest leads.

QT interval, it represents the total time from the onset of

ventricular depolarization to the completion of repolarization.

It indicates the duration of ventricular systole i.e. contraction

of the ventricle lasts from the beginning of the Q wave to the

end of the T wave. Normally it is about 0.35 seconds; range

0.28 – 0.44 seconds.

3

4

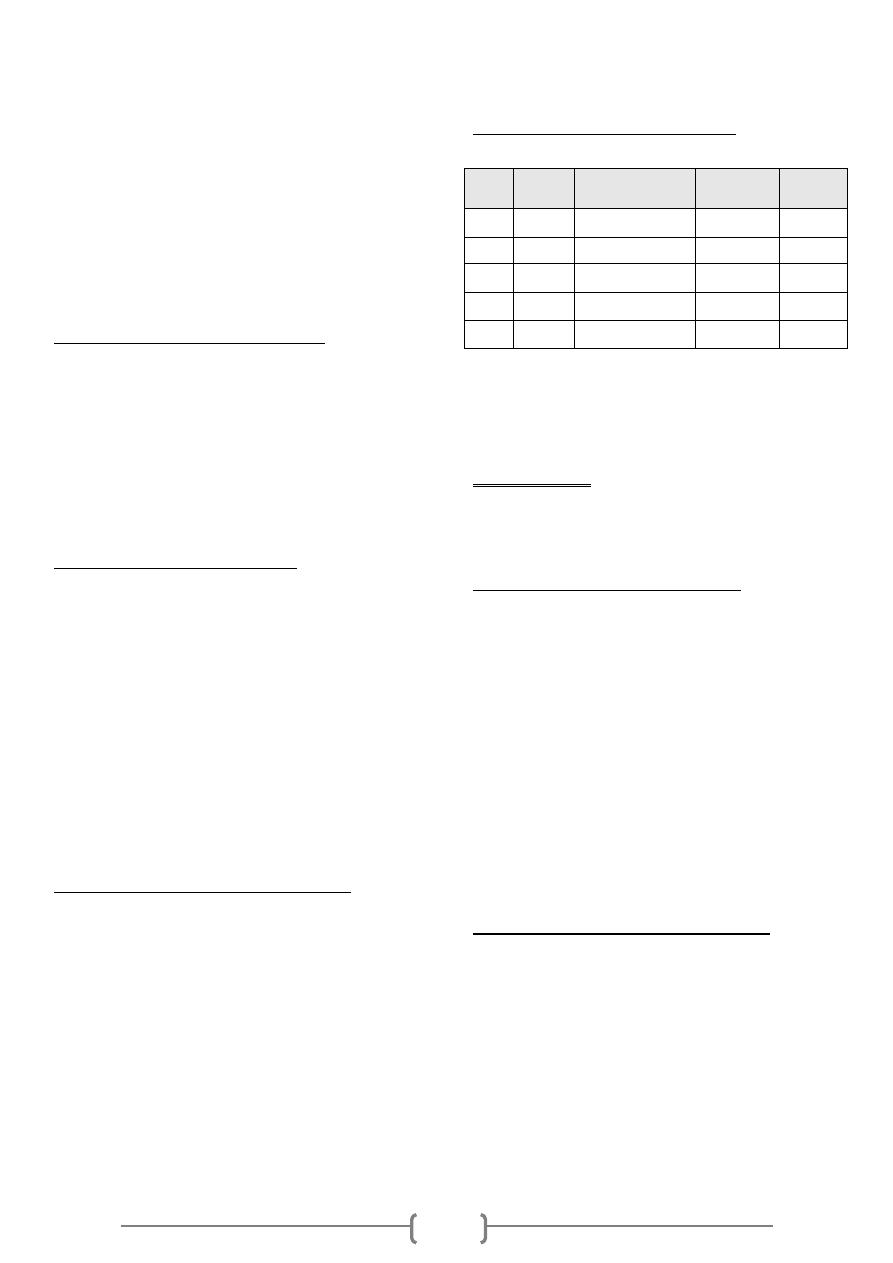

Exercise ECG test:

Exercise electrocardiography (ECG) is one of the most

frequent, non invasive modalities used to assess subjects with

suspected or proven cardiovascular disease.

The most common modes of exercise stress testing include

multistage bicycle ergometry and treadmill tests. The test,

"graded" for exercise intensity, includes submaximal levels

of three to four minutes duration each, progressing up to a

self-imposed fatigue level. The graded nature of the test

allows detection of ischemic manifestations and rhythm

disorders with small increments in exercise intensity.

Indications of exercise ECG test:

(1) Diagnostic indications:

1. Assessment of chest pain in patients with a probability

for coronary artery disease.

2. Arrhythmia provocation.

(2) Prognostic indications:

1. Evaluation of exercise tolerance and cardiac function.

2. Risk assessment after myocardial infarction.

3. Assessment of treatment for arrhythmia.

4. Evaluation of revascularization.

2. Preparation and Technique:

The following steps were performed before starting the

exercise test:

1) The room was checked for all equipments related to

cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

2) The subjects were asked to come overnight fasting or with

light breakfast at early morning.

3) The subjects were informed about details and hazards of the

test.

4) Shaving the hair of the chest and upper abdomen.

5) Electrode sites on limbs and chest were prepared with alcohol

to clean the skin.

6) The Manson-Likar limb lead modification was used; putting

the arm leads near the shoulders and lower limb leads on

sides of the abdomen.

Manson-Likar limb lead modification:

According to the Manson-Likar limb lead modification, the

electrodes were placed as follows:

1) RA (right arm): just below the right clavicle medial to deltoid

muscle.

2) LA (left arm): just below the left clavicle medial to deltoid

muscle.

3) RL (right leg): just above the right iliac crest on the

midaxillary line.

4) LL (left leg): just above the left iliac crest on the midaxillary

line.

5) V1: in the 4

th

intercostals space on the right sternal border.

6) V2: in the 4

th

intercostals space on the left sternal border.

7) V3: at the midpoint of a straight line between V2 and V4.

8) V4: in the 5

th

intercostals space on the midclavicular line.

9) V5: in the 5

th

intercostals space on the anterior axillary line.

10) V6: in the 5

th

intercostals space on the midaxillary line.

Exercise treadmill test protocol:

Modified Bruce Protocol

Workload is a reflection of oxygen consumption and hence

energy use.

Assessment of workload is measured by metabolic

equivalents (METs).

٭1 METs equals 3.5 ml oxygen/Kg per minute.

Heart rate response to exercise:

At the transition from rest to exercise, the heart rate increases

rapidly to value of 160-180 beats/min. During short periods

of maximal exercise, rates as high as 240 beats/min. have

been recorded. The initial rapid increase is thought to be the

result of central command influences or a brisk reflex from

mechanoreceptors. The almost instantaneous acceleration in

heart rate is due to vagal withdrawal than an increase in

sympathetic tone. Later, the increase in reflex activation of

pulmonary stretch receptors will trigger increased

sympathetic tone and additional parasympathetic withdrawal.

Increased circulating catecholamines from the adrenal glands

play a role as well. It has been shown that during exercise the

increase in heart rate accounts for a greater percentage of the

increase in cardiac output than does the increase in stroke

volume.

Blood pressure response to exercise:

The normal exercise response is an increase in the systolic

blood pressure which is progressive with the increase in

workloads to a peak response ranging from 160 to 200

mmHg, with the higher range of the scale in older subjects

with less compliant vascular system. In contrast, the diastolic

blood pressure does not usually change significantly. Failure

to increase systolic blood pressure beyond 120 mmHg, or a

sustained decrease greater than 10 mmHg is abnormal and

reflects either inadequate elevation of cardiac output because

of left ventricular systolic pump dysfunction or an excessive

reduction in systemic vascular resistance.

An abnormal systolic blood pressure response in

subjects with ischemic heart disease (IHD) is associated with

more extensive myocardial perfusion defects. Conditions

other than myocardial ischemia that have been associated

with failure to increase or an actual decrease in systolic blood

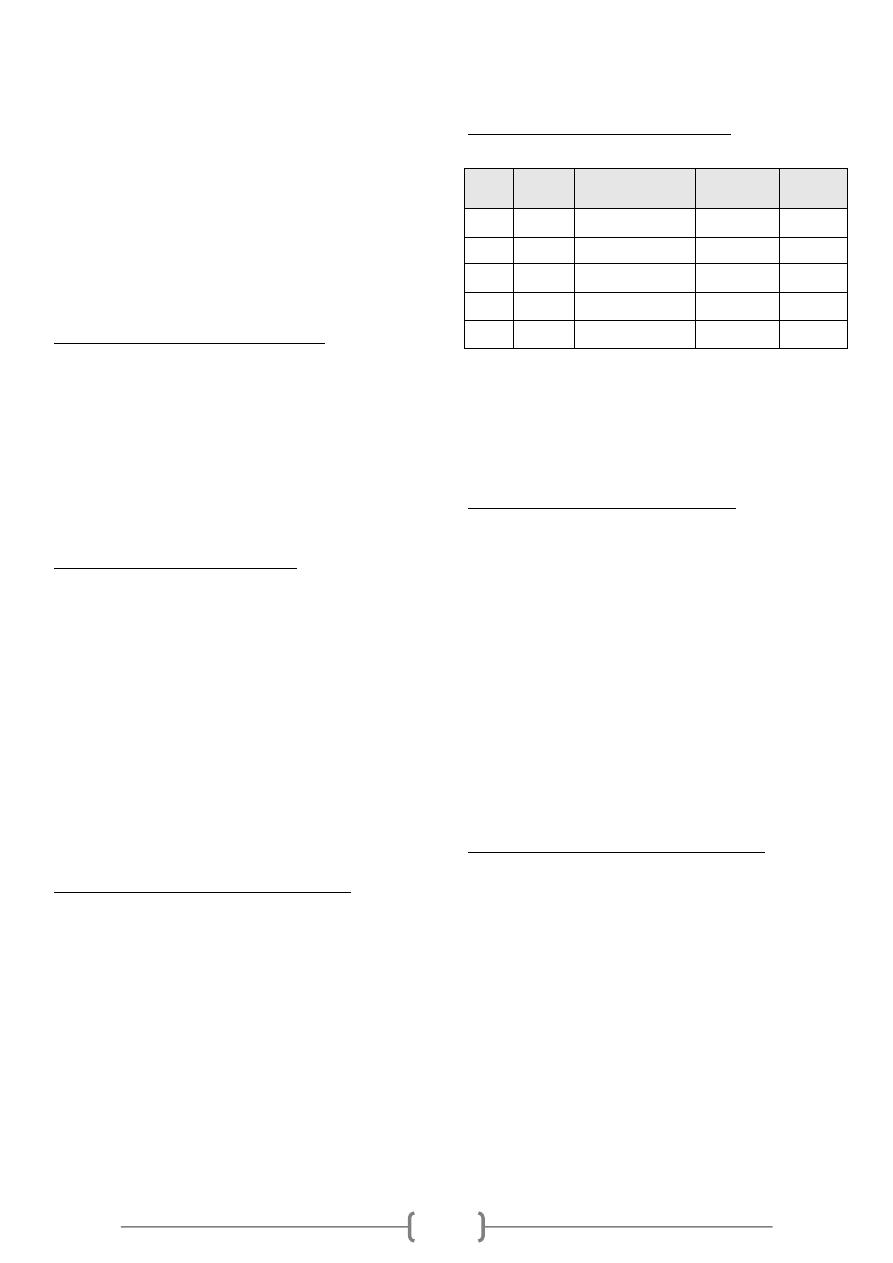

Stage Speed

(Km/h)

Grade/inclination

(%)

٭Workload

٭(METs)

Time

(minute)

1

2.7

10

5

3

2

4

12

7

3

3

5.4

14

9.5

3

4

6.7

16

13

3

5

8

18

16

3

5

pressure during progressive exercise are, cardiac arrhythmias,

vasovagal reactions, and ingestion of antihypertensive

drugs.

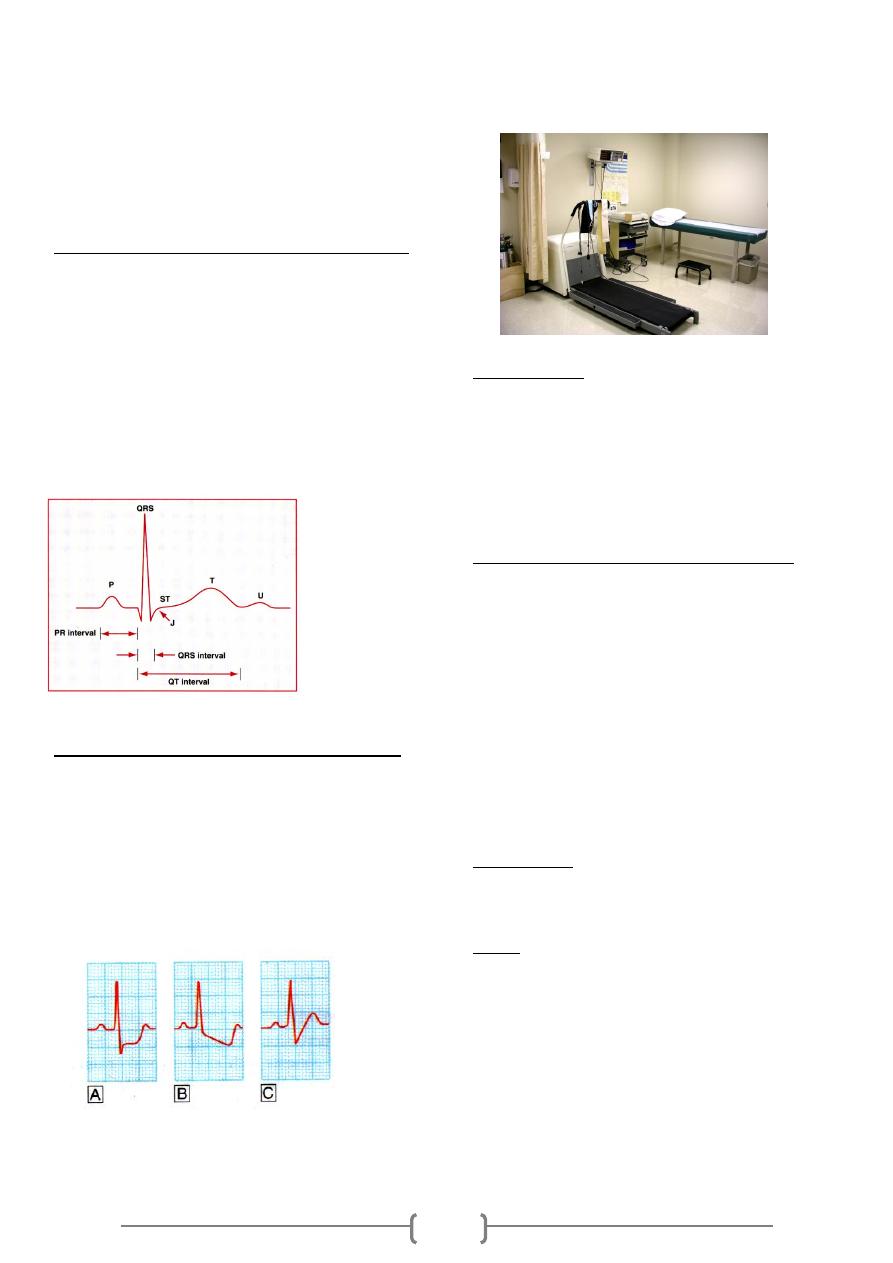

ECG findings during exercise stress testing:

In normal persons, the PR, QRS, and QT interval shortens as

heart rate increases. During exercise, P wave amplitude

increases, and the PR segment becomes progressively more

downsloping in the inferior leads. J-point or junctional

depression is a normal finding during exercise. In patients

with myocardial ischemia, however, the ST segment usually

becomes more horizontal (flattens) as the severity of

ischemic response worsens. Moreover, with progressive

exercise, the depth of ST segment depression may increase,

involving more ECG leads, and the patients may develop

chest pain.

Figure: The J-point in normal ECG waveform

Measurement of ST segment displacement:

ST segment depression is measured relative to the isoelectric

baseline (between the next T and P waves) at point 0.06 to

0.08 second (about 2 small squares) after the J- point.

Accordingly, detection of abnormal ECG changes during

exercise was depending on standard criteria for an abnormal

ST segment response which is horizontal (planar) or

downsloping depression of > 1mm, while upsloping ST

depression is considered as a normal fining during exercise.

Figure : Forms of exercise induced ST segment depression.

A- Plantar ST depression, is usually indicative of

myocardial ischemia.

B- Downsloping depression also usually indicates

myocardial ischemia.

C- Upsloping depression, however, may be a normal

finding.

The J- point:

The J-point represents the exact point at which the wave of

depolarization just completes its passage through the heart,

it occurs at the end of the QRS complex. At this point, all

parts of the ventricles are depolarized including both the

damaged and the normal parts, so that, no current is flowing

around the heart, therefore, the potential of ECG at this

instant is zero voltage.

Contra-indications for exercise testing:

1. Acute myocardial infarction.

2. Unstable angina.

3. Uncontrolled heart failure.

4. Acute myocarditis or pericarditis.

5. Acute systemic infection.

6. Deep vein thrombosis.

7. Uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure > 220

mmHg, diastolic > 120 mmHg.

8. Severe aortic stenosis.

9. Severe hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy.

10. Untreated life threatening arrhythmia.

11. Recent aortic surgery.

12. Advanced atrioventricular block.

-END-

1

Exercise ECG test:

Exercise electrocardiography (ECG) is one of the most

frequent, non invasive modalities used to assess subjects

with suspected or proven cardiovascular disease.

The most common modes of exercise stress testing include

multistage bicycle ergometry and treadmill tests. The test,

"graded" for exercise intensity, includes submaximal levels

of three to four minutes duration each, progressing up to a

self-imposed fatigue level. The graded nature of the test

allows detection of ischemic manifestations and rhythm

disorders with small increments in exercise intensity.

Indications of exercise ECG test:

(1) Diagnostic indications:

1. Assessment of chest pain in patients with a probability

for coronary artery disease.

2. Arrhythmia provocation.

(2) Prognostic indications:

1. Evaluation of exercise tolerance and cardiac function.

2. Risk assessment after myocardial infarction.

3. Assessment of treatment for arrhythmia.

4. Evaluation of revascularization.

2. Preparation and Technique:

The following steps were performed before starting the

exercise test:

1) The room was checked for all equipments related to

cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

2) The subjects were asked to come overnight fasting or with

light breakfast at early morning.

3) The subjects were informed about details and hazards of the

test.

4) Shaving the hair of the chest and upper abdomen.

5) Electrode sites on limbs and chest were prepared with

alcohol to clean the skin.

6) The Manson-Likar limb lead modification was used; putting

the arm leads near the shoulders and lower limb leads on

sides of the abdomen.

Manson-Likar limb lead modification:

According to the Manson-Likar limb lead modification, the