Lecture 5+6 – Hemorrhage & Shock

20

Hemorrhage

Haemorrhage or bleeding is the loss of blood from the

circulatory system. It must be recognized & managed

aggressively to avoid multiple organ failure & death. It

must be treated first by arresting it, then other measures

like fluid resuscitation & blood transfusion.

Pathophysiology

Haemorrhage may lead to hypovolaemic shock

(hypoperfusion), the following events may occur:

Cellular anaerobic metabolism with lactic acidosis

(this acidosis causes coagulopathy & further

haemorrhage).

Ischaemic endothelial cells activate anti-coagulant

pathways & further haemorrhage.

Underperfused muscles are unable to generate heat so

hypothermia results which affects coagulation &

results in further haemorrhage.

These events result in a vicious cycle leading to

physiological exhaustion & death.

Medical therapy has a tendency to worsen the conditio

Intravenous fluids & blood are cold, so causes

hypothermia.

Many crystalloid fluids are acidic (normal saline has a

PH of 6.7).

Surgery causes heat loss (by opening body cavities) &

causes further haemorrhage.

Types of haemorrhage

1) Revealed & concealed haemorrhage :

Revealed haemorrhage: Obvious external haemorrhage.

eg. bleeding from open arterial wound, haematemesis

from DU.

Concealed haemorrhage: It is contained within body

cavity. It must be diagnosed & treated early, eg.

Abdominal (peritoneal & retroperitoneal), thoracic, &

pelvic bleeding due to trauma. Non-traumatic cause eg.

ruptured aortic aneurysm, occult GI bleeding.

2) Primary, reactionary, & secondary haemorrhage:

Primary hemorrhage: Occurring immediately as a result

of injury or surgery.

Reactionary (Delayed) haemorrhage : Occurring within

24 hours. Usually caused by dislodgement of clot (by

resuscitation, vasodilatation, normalization of BP) or due

to a slippage of a ligature.

Secondary haemorrhage: It usually occurs within 7 – 14

days after injury. It is precipitated by infection, pressure

necrosis (such as from a drain), or malignancy.

3) Surgical & non-surgical haemorrhage

Surgical haemorrhage: Result from direct injury; it is

amenable to surgical control.

Non-surgical haemorrhage: Result from oozing from

raw surfaces due to coagulopathy. It requires correction of

coagulation abnormalities or packing.

Hemorrhag is broken down into 4 classes by the

American College of Surgeons' Advanced Trauma Life

Support

1) Class I Hemorrhage involves up to 15% of blood

volume. There is typically no change in vital signs and

fluid resuscitation is not usually necessary.

2) Class II Hemorrhage involves 15-30% of total blood

volume. A patient is often tachycardic (rapid heartbeat)

with a narrowing of the difference between the systolic

and diastolic blood pressures. The body attempts to

compensate with peripheral vasoconstriction. Skin may

start to look pale and be cool to the touch. Volume

resuscitation with crystalloids (Saline solution or Lactated

Ringer's solution) is all that is typically required. Blood

transfusion is not typically required.

3) Class III Hemorrhage involves loss of 30-40% of

circulating blood volume. The patient's blood pressure

drops, the heart rate increases, peripheral perfusion, such

as capillary refill worsens, and the mental status worsens.

Fluid resuscitation with crystalloid and blood transfusion

are usually necessary.

4) Class IV Hemorrhage involves loss of >40% of

circulating blood volume. The limit of the body's

compensation is reached and aggressive resuscitation is

required to prevent death

Lecture 5+6 – Hemorrhage & Shock

21

Management of haemorrhage

1) Identify haemorrhage: Revealed haemorrhage may be

obvious but the diagnosis of concealed haemorrhage may

be difficult. Any shock should be assumed to be

hypovolaemic until proved otherwise & the cause should

be assumed haemorrhage until this has been excluded.

2) Immediate resuscitation:

Direct pressure should be placed over the site of external

haemorrhage .

Airway & breathing should be assessed & controlled.

Large- bore intravenous access should be instituted &

blood drawn for cross- matching.

Intravenous fluids should be given, & when the blood is

available it should be given according to the degree of

haemorrhage.

3) Identify the site of haemorrhage:

This is important to define the next step in haemorrhage

control (operation, endoscopic control,

angioembolization).

• History: Previous episodes, known aneurysm, drugs

(steroidal & nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory).

• Physical examination: Nature of blood : fresh, melaena,

external signs of injury, abdominal tenderness.

• Investigations: Must be appropriate to the patients

physiological condition, & unnecessary investigations

must be avoided. Chest & pelvic radiography, abdominal

ultrasound, diagnostic peritoneal aspiration.

4) haemorrhage control:

Control must be achieved rapidly by moving the patient

rapidly to a place of haemorrhage control (theater,

angiography or endoscopy suites). Patient needs

lifesaving procedure so surgery may need to be limited to

the minimum necessary to stop bleeding & control sepsis.

More definitive repairs can be delayed until the patient is

physiologically capable of sustaining the procedure

(Damage control surgery).

Shock

Shock is the most important cause of death among

surgical patients.

Definition: It is a systemic state of low tissue perfusion,

which is inadequate for normal cellular respiration.

Pathophysiology

1) Cellular

Tissue perfusion is reduced,

cells are deprived of oxygen

anaerobic metabolism occurs

Liberation of lactic acid (instead of carbon dioxide)

causes systemic metabolic acidosis .

As glucose within the cells exhausted anaerobic

respiration ceases

failure of sodium potassium pump in the cell membrane

& intracellular organelles.

Intracellular lysosomes release autodigestive enzymes &

cell lysis ensues.

Intracellular contents including potassium are released

into the blood stream causing hyperkalaemia.

2) Microvascular

Tissue ischemia activate immune & coagulation

systems.

Hypoxia & acidosis activate complement & prime

neutrophils resulting in the generation of oxygen free

radicals & cytokine release.

These lead to injury to capillary endothelial cells &

further activation of the immune & coagulation

systems.

The damaged endothelium becomes leaky, so fluid

leaks & tissue oedema ensues, exacerbating cellular

hypoxia.

3) Systemic

a) Cardiovascular: Decreased preload & afterload cause

compensatory baroreceptor response which leads to

increased sympathetic activity & release of

catecholamines into the circulation which results in

tachycardia & systemic vasoconstriction (except in sepsis)

Lecture 5+6 – Hemorrhage & Shock

22

b) Respiratory: The metabolic acidosis & increased

sympathetic activity result in an increased respiratory rate

& minute ventilation to increase the excretion of carbon

dioxide & this produces compensatory respiratory

alkalosis.

c) Renal: Decreased perfusion pressure in the kidney leads

to reduced filtration at the glomerulus & a decreased urine

output.

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis is stimulated

resulting in further vasoconstriction & increased sodium

& water reabsorption by the kidney.

d) Endocrine: Antidiuretic hormon (vasopressin) is released

from hypothalamus & results in vasoconstriction & water

reabsorption in the renal collecting system.

Cortisol is also released from the adrenal cortex causes

sodium & water reabsorption & sensitising the cells to

catecholamines.

4) Ischemia-perfusion syndrome

Systemic hypo-perfusion causes tissue hypoxia which

activates complement, neutrophils, & microvascular

thrombi which cause further endothelial damage to

organs such as the lungs & kidneys.

The acid & potassium load cause myocardial

depression, vascular dilatation & further hypotension.

These events cause multiple organ failure.

Classification of shock

1) Hypovolemic shock:

It is the most common form of shock, caused by reduced

circulating volume due to

a) haemorrhagic causes

b) Non-haemorrhagic causes: poor fluid intake, excessive

fluid loss because of vomiting, diarrhea, urinary loss

(as in diabetes), evaporation & third- spacing (fluid is

lost into GIT & interstitial spaces as in bowel

obstruction or pancreatitis.

2) Cardigenic shock

It is due to primary failure of the heart to pump blood to

the tissues.

It occurs in:

a) myocardial infarction

b) dysrhythmias

c) valvular heart disease

d) blunt myocardial injury

e) cardiomyopathy

f) Myocardial depression: results from endogenous

factors released in sepsis & pancreatitis or exogenous

factors such as drugs.

3) Obstructive shock

Mechanical obstruction of cardiac filling causes reduction

of preload & fall in cardiac output.

It occurs in :

a) cardiac tamponade

b) tension pneumothorax

c) massive pulmonary embolism

d) Air embolism.

4) Distributive shock

There is abnormally high cardiac output with

vasodilatation & hypotension. There is maldistribution of

blood flow at a microvascular level with arteriovenous

shunting & dysfunction of the cellular utilization of

oxygen. The peripheries are worm & capillary refill is

brisk despite profound shock.

It occurs in

a) Septic shock: caused by release of endotoxins &

acivation of cellular & humoral components of the

immune system.

b) Anaphylaxis: vasodilatation is caused by histamine

release.

c) Spinal cord injury (neurogenic shock): caused by

failure of sympathetic outflow & adequate vascular

tone.

5)

Endocrine shock

: It occurs in:

a) hypo- & hyperthyroidism

b) Adrenal insufficiency.

In hypothyroidism there is disordered vascular & cardiac

responsiveness to circulating catecholamines so cardiac

output falls & there may be associated cardiomyopathy.

Hyperthyroidism may cause a high- output cardiac failure.

In adrenal insufficiency there is hypovolaemia & poor

response to circulating & exogenous catecholamines, it

occurs in Addisons disease, & systemic sepsis.

Severity of shock:

1) Compensated shock: There is a compensatory

cardiovascular & endocrine response to maintain adequate

blood flow to the most vital organs (brain, heart, lungs, &

kidneys) & reducing perfusion to the skin, muscles, &

Lecture 5+6 – Hemorrhage & Shock

23

GIT. Apart from tachycardia & cool peripheries

(vasoconstriction) there may be no other clinical signs of

hypovolaemia. Loss of 15% of the circulating blood

volume is within normal compensatory mechanism.

Blood pressure is only falls after 30-40% of circulating

volume has been lost.

2) Decompensation: Further loss of circulating volume

causes progressive cardiovascular, respiratory, & renal

decompensation.

3) Mild shock: Initially there is tachycardia, tachypnoea &

mild reduction in urine output with mild anxiety. Blood

pressure is maintained although there is a decrease in

pulse pressure. The peripheries are cold & sweaty with

prolonged capillary refill times (except in septic

distributive shock).

4) Moderate shock: As shock progresses, renal

compensatory mechanisms fail, renal perfusion falls &

urine output decreases below 0.5 ml/kg/h. There is further

tachycardia & blood pressure starts to fall. Patients

become drowsy & mildly confused.

5) Severe shock: There is profound tachycardia &

hypotension. Urine output falls to zero & patients are

unconscious with labored respiration.

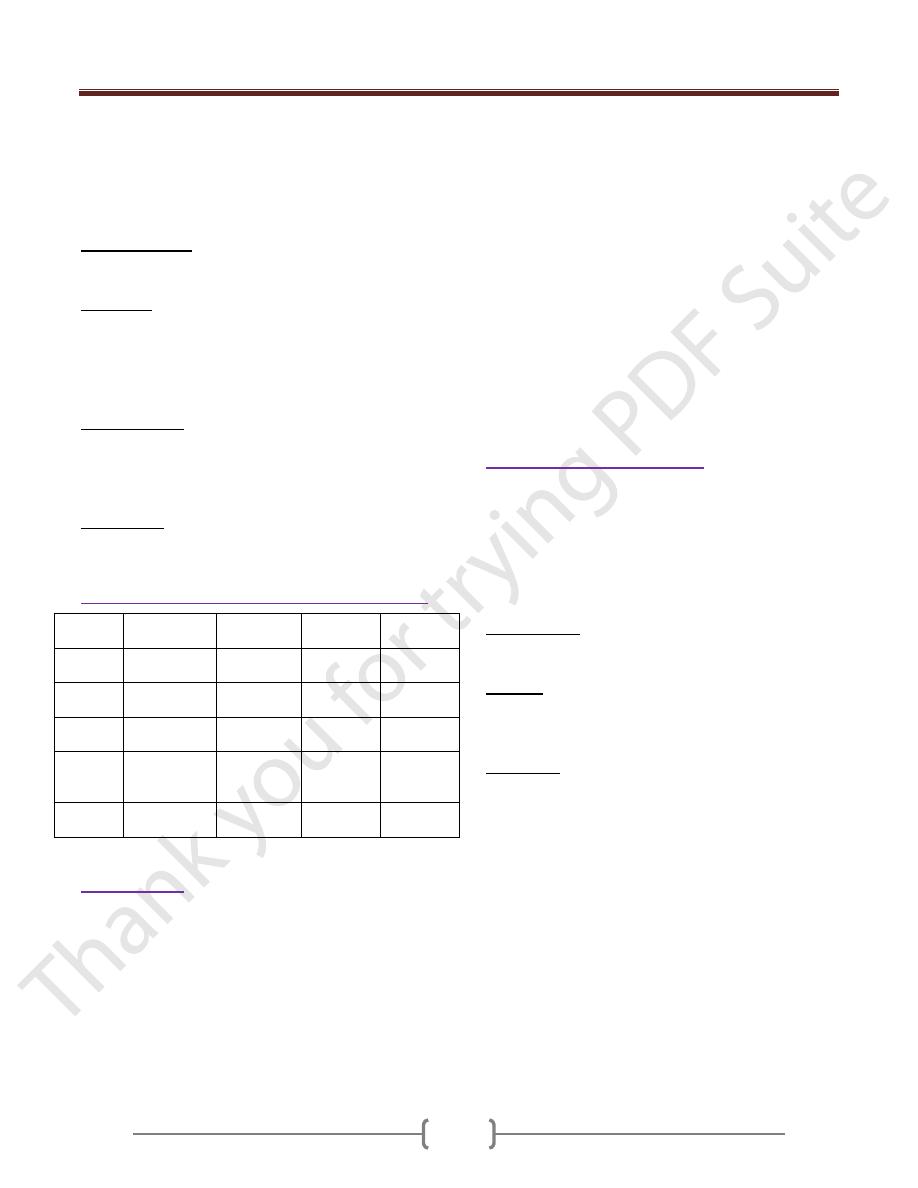

Cardiovascular and metabolic characteristics of shock

Hypovolaemia

Cardiogenic

Obstructive

Distributive

Cardiac

output

Low

Low

Low

High

Vascular

resistance

High

High

High

Low

Venous

pressure

Low

High

High

Low

Mixed

venous

saturation

Low

Low

Low

High

Base

deficit

High

High

High

High

Resuscitation

Should be rapid.

If there is doubt about the cause of shock it is safer to

assume the cause is hypovolaemia & begins with fluid

resuscitation followed by an assessment of the response.

If the general condition of the patient permits, rapid

clinical examination is performed.

In patients who are actively bleeding the resuscitation

should proceed parallel with surgery.

1) Ensure a patent airway & adequate oxygenation &

ventilation.

2) Intravenous access (with short wide- bore catheter) &

blood sample aspirated for cross-matching & blood

should be requested.

3) Intravenous administration of the available fluids

(crystalloid or colloid) while waiting blood Blood

transfusion should be done as early as possible.

4) Vasopressor agents (phenylephrine, noradrenaline) are

used in distributive shock in which there is peripheral

vasodilatation with hypotension despite high cardiac

output.

In cardiogenic shock or when myocardial depression

complicates a shock state inotropic therapy may be

needed to increase cardiac output & therefore oxygen

delivery. The inodilator dobutamine is the drug of choice.

Management of septic shock

1) Admission to intensive care unit of hospital.

2) Care of airway and breathing. Giving oxygen, and may

need mechanical ventilation.

3) Intravenous fluid (Crystalloid or colloid).

4) Antibiotic.

5) Taking history when the condition of patient permits.

6) Control of diabetes.

7) Investigations: Hb, WBC count, RBS, S. electrolytes, B.

urea, S. creatinin. Blood, urine and pus culture may be

needed. Chest X-ray.

8) Surgery: Drainage of pus, gangrene of limb may need

amputation.

9) Care of intravenous line (canula), intercostal tube and

Foley catheter if present.

10) Monitoring

a) Pulse rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate and

temperature

b) Oxygen saturation monitoring

c) Hourly urine output measurement. The best measures

of organ perfusion & the best monitor of the adequacy

of shock therapy remain the urine output.

d) CVP monitoring

e) Electrocardiogram

f) Cardiac output monitoring

g) Level of consciousness (is an important marker of

cerebral perfusion although it is a poor marker of

adequacy of resuscitation).

h) Measures of S. electrolytes and acid base balance.