Unit 4 - Infectious disease

37

Lecture 1+2+3 - Protozoal Infections

Systemic protozoal infections

Malaria

Malaria in humans is caused by Plasmodium falciparum,

P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae .

It is transmitted by the bite of female anopheline

mosquitoes and occurs throughout the tropics and

subtropics at altitudes below 1500 metres. Recent

estimates have put an episodes of clinical malaria at 515

million cases per year, with two-thirds of these occurring

in sub-Saharan Africa, especially amongst children and

pregnant women. P. falciparum has now become resistant

to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, initially in

South-east Asia and now throughout Africa.

Pathogenesis

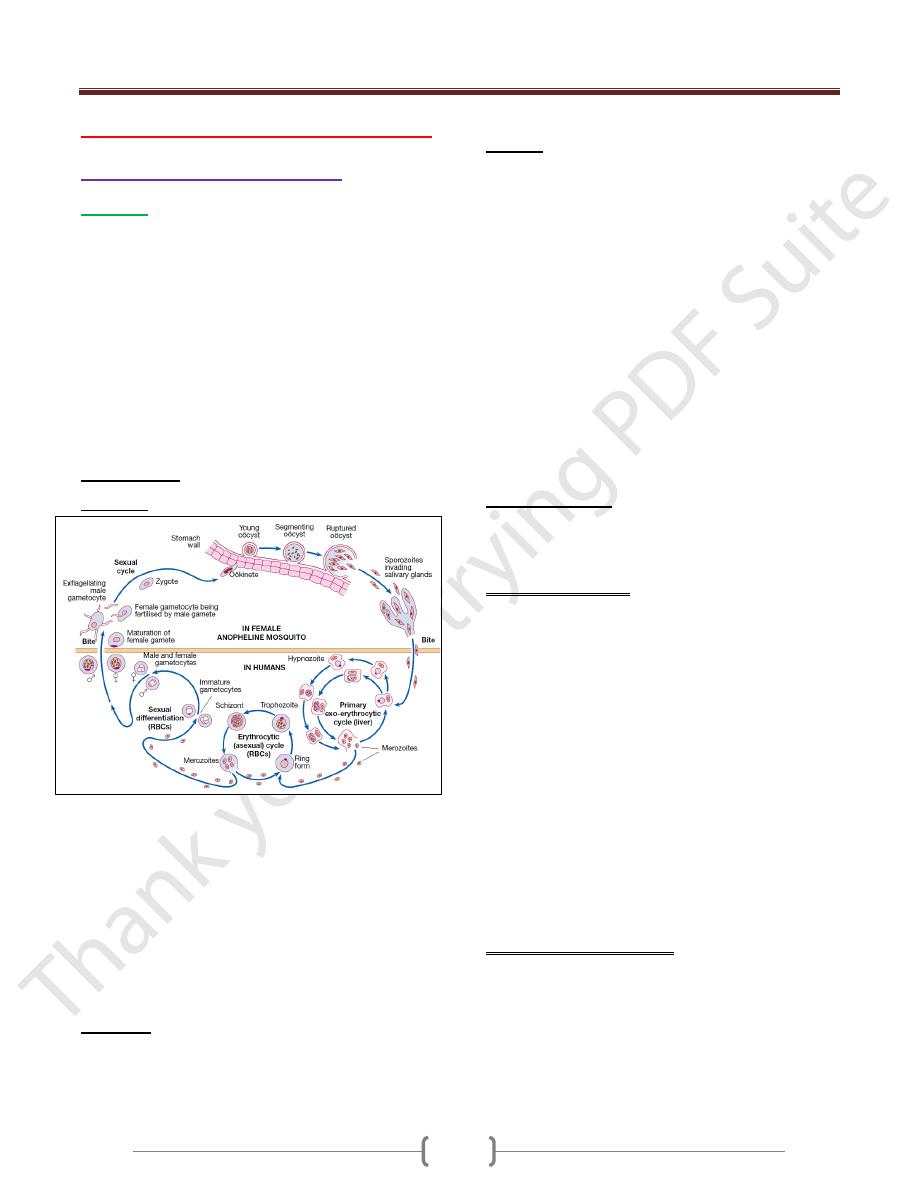

Life cycle

P. vivax and P. ovale may persist in liver cells as dormant

forms, hypnozoites, capable of developing into merozoites

months or years later. Thus the first attack of clinical

malaria may occur long after the patient has left the endemic

area & the disease may relapse after treatment if drugs that

kill only the erythrocytic stage of the parasite are given.

P. falciparum and P. malariae have no persistent exo-

erythrocytic phase but recrudescence of fever may result

from multiplication of parasites in red cells which have

not been eliminated by treatment and immune processes.

Pathology

Red cells infected with malaria are prone to hemolysis.

This is most severe with P. falciparum, which invades red

cells of all ages but especially young cells.

P. vivax and P. ovale invade reticulocytes.

P. malariae normoblasts, so that infections remain lighter.

Anaemia may be profound and is worsened by dys-

erythropoiesis, splenomegaly and depletion of folate stores.

In P. falciparum malaria, red cells containing trophozoites

adhere to vascular endothelium in post-capillary venules

in brain, kidney, liver, lungs and gut. The vessels become

congested, resulting in widespread organ damage which is

exacerbated by rupture of schizonts, liberating toxic and

antigenic substances. P. falciparum has influenced human

evolution, with the appearance of protective mutations

such as sickle-cell, thalassaemia, G6PD deficiency and

HLA-B53. P. falciparum does not grow well in red cells

that contain haemoglobin F, C or especially S.

Haemoglobin S heterozygotes (AS) are protected against

the lethal complications of malaria.

P. vivax cannot enter red cells that lack the Duffy blood

group; therefore many West Africans and African-

Americans are protected.

Clinical features

The clinical features of malaria are non-specific and the

diagnosis must be suspected in anyone returning from an

endemic area that has features of infection.

P. falciparum infection: This is the most dangerous of the

malarias and patients are either ‘killed or cured’. The

onset is often insidious, with malaise, headache and

vomiting. Cough and mild diarrhea are also common. The

fever has no particular pattern. Jaundice is common due to

haemolysis and hepatic dysfunction. The liver and spleen

enlarge and may become tender. Anaemia develops

rapidly, as does thrombocytopenia. A patient with

falciparum malaria, apparently not seriously ill, may

rapidly develop dangerous complications.

Cerebral malaria is manifested by confusion, seizures or

coma, usually without localizing signs. Children die rapidly

without any special symptoms other than fever. Immunity

is impaired in pregnancy & the parasite can preferentially

bind to a placental protein known as chondroitin sulphate A.

Abortion and intrauterine growth retardation from

parasitisation of the maternal side of the placenta are frequent

Previous splenectomy increases the risk of severe malaria.

P. vivax and P. ovale infection

In many cases the illness starts with several days of

continued fever before the development of classical bouts

of fever on alternate days.

Fever starts with a rigor.

The patient feels cold & the temperature rises to about 40 °C.

After half an hour to an hour the hot or flush phase begins.

It lasts several hours and gives way to 3- 3- profuse

perspiration and a gradual fall in temperature. The cycle is

Unit 4 - Infectious disease

38

repeated 48 hours later. Gradually the spleen and liver

enlarge and may become tender. Anaemia develops slowly.

Relapses are frequent in the first 2 years after leaving the

malarious area & infection may be acquired from blood

transfusion.

P. malariae infection

This is usually associated with mild symptoms and bouts

of fever every third day. Parasitaemia may persist for

many years with the occasional recrudescence of fever, or

without producing any symptoms. Chronic P. malariae

infection causes glomerulonephritis and longterm

nephrotic syndrome in children.

Investigations

1) Giemsa-stained thick and thin blood films should be

examined whenever malaria is suspected.

In the thick film erythrocytes are lysed, releasing all

blood stages of the parasite. This, as well as the fact that

more blood is used in thick films, facilitates the diagnosis

of low level parasitaemia. A thin film is essential to

confirm the diagnosis, to identify the species of parasite

and, in P. falciparum infections, to quantify the parasite

load (by counting the percentage of infected erythrocytes).

P. falciparum parasites may be very scanty, especially in

patients who have been partially treated. With P.

falciparum, only ring forms are normally seen in the early

stages (see Fig. 13.31); with the other species all stages of

the erythrocytic cycle may be found.

Gametocytes appear after about 2 weeks, persist after

treatment and are harmless, except that they are the source

by which more mosquitoes become infected.

2) Immunochromatographic tests for malaria antigens,

such as OptiMal® (which detects the Plasmodium lactate

dehydrogenase of several species) and ParasightF®

(which detects the P. falciparum histidine-rich protein 2),

are extremely sensitive and specific for falciparum.

malaria but less so for other species. They should be used

in parallel with blood film examination but are especially

useful where the microscopist is less experienced in

examining blood films.

3) DNA detection (PCR) is used mainly in research and is

useful for determining whether a patient has a

recrudescence of the same malaria parasite or a

reinfection with a new parasite.

Management

Mild P. falciparum malaria

Since P. falciparum is now resistant to chloroquine and

sulfadoxine- pyrimethamine (Fansidar) almost worldwide,

an artemisinin-based treatment is recommended. Co-

artemether (CoArtem® or Riamet®) contains artemether

and lumefantrine and is given as 4 tablets at 0, 8, 24, 36,

48 and 60 hours. Alternatives are quinine by mouth (600

mg of quinine salt every 8 hours for 5–7 days), together

with or followed by either doxycycline (200 mg once

daily for 7 days) or clindamycin (450 mg every 8 hours

for 7 days) or atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone®, 4

tablets once daily for 3 days).

Doxycycline & artemether should be avoided in pregnancy.

Complicated P. falciparum malaria

Severe malaria should be considered as a medical emergency.

Management includes

1) early and appropriate antimalarial chemotherapy,

2) active treatment of complications,

3) Correction of fluid, electrolyte and acid–base balance,

and avoidance of harmful ancillary treatments.

4) The treatment of choice is intravenous artesunate , as

soon as the patient has recovered sufficiently to

swallow tablets, oral artesunate

5) Quinine salt can also be used.

Management of non-falciparum malaria

P. vivax, P. ovale and P. malariae infections should be

treated with oral chloroquine: 600 mg chloroquine base

followed by 300 mg base in 6 hours, then 150 mg base

12- hourly for 2 more days. ‘radical cure’ is now achieved

in most patients with P. vivax or P. ovale malaria using a

course of primaquine (15 mg daily for 14 days), which

destroys the hypnozoite phase in the liver.

Note:

Development of a fully protective malaria vaccine

is still some way off, which is not surprising considering

that natural immunity, is incomplete and not long-lived.

There is, however, some evidence that vaccination can

reduce the incidence of severe malaria in populations.

Trial vaccines are being evaluated in Africa.

African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness)

African sleeping sickness is caused by trypanosomes

conveyed to humans by the bites of infected tsetse flies,

and is unique to sub-Saharan Africa.

Trypanosoma brucei gambiense trypanosomiasis has a

wide distribution in West and Central Africa.

T. brucei rhodesiense trypanosomiasis is found in parts of

East and Central Africa, where it is currently on the increase.

Clinical features

A bite by a tsetse fly is painful and commonly becomes

inflamed, but if trypanosomes are introduced, the site may

Unit 4 - Infectious disease

39

again become painful and swollen about 10 days later

(‘trypanosomal chancre’) and the regional lymph nodes

enlarge (‘Winterbottom’s sign’). Within 2–3 weeks of

infection the trypanosomes invade the blood stream. The

disease is characterised by an early haematolymphatic

stage and a late encephalitic stage in which the parasite

crosses the blood–brain barrier and chronic

encephalopathy develops.

Rhodesiense infections

In these infections the disease is more acute and severe

than in gambiense infections, so that within days or a few

weeks the patient is usually severely ill and may have

developed pleural effusions and signs of myocarditis or

hepatitis. There may be a petechial rash. The patient may

die before there are signs of involvement of the CNS. If

the illness is less acute, drowsiness, tremors and coma

develop.

Gambiense infections

The distinction between early and late stages may not be

apparent in gambiense infections. The disease usually

runs a slow course over months or years, with irregular

bouts of fever and enlargement of lymph nodes. The

spleen and liver may become palpable. After some

months without treatment, the CNS is invaded. This is

shown clinically by headache and changed behaviour,

blunting of higher mental functions, insomnia by night

and sleepiness by day, mental confusion and eventually

tremors, pareses, wasting, coma and death.

Investigations

1) Thick & thin blood films stained will reveal trypanosomes.

2) The Concentration methods include buffy coat

microscopy & miniature anion exchange chromatography.

3) Rapid card agglutination trypanosomiasis test (CATT) for

antibody detection.

4) If the CNS is affected, CSF analysis which reveals

pleocytosis, increased protein, pressure and diminished

glucose. Presence of high level IgM in CSF is suggestive

for trypanosomiasis.

Management

Before CNS involvement, intravenous suramin, for

rhodesiense infections.

For gambiense infections, intramuscular or intravenous

pentamidine.

Once the nervous system is affected, treatment with

melarsoprol is effective for both East &West African

diseases.

American trypanosomiasis (Chagas’ disease)

The cause is Trypanosoma cruzi, transmitted to humans

from the faeces of a reduviid (triatomine) bug in which

the trypanosomes have a cycle of development before

becoming infective to humans.

There are 2 phases of the disease: acute & chronic phases.

Investigations

1) T. cruzi is easily detectable in a blood film in the acute illness

2) In chronic disease it may be recovered in up to 50% of

cases by xenodiagnosis,.

3) Parasite DNA detection by PCR in the patient’s blood is a

highly sensitive method for documentation of infection

and, in addition, can be employed in faeces of bugs used

in xenodiagnosis tests to improve sensitivity.

4) Antibody detection is also highly sensitive (99%).

Management

Parasiticidal agents are used to treat the acute phase,

congenital disease and early chronic phase (within 10

years of infection).

1) Nifurtimox is given orally.

2) Benznidazole is an alternative.

3) Specific drug treatment of the chronic form is now

increasingly favoured, but in the cardiac or digestive

‘mega’ diseases it does not reverse established tissue

damage. Surgery may be needed.

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasma gondii is an intracellular parasite

Transmission

1- Via oöcyst- contaminated soil, salads and vegetables.

2- Ingestion or tasting of raw or undercooked meats

containing tissue cysts. Sheep, pigs and rabbits are the

most common meat sources.

Outbreaks of toxoplasmosis have been linked to the

consumption of unfiltered water.

Clinical features

1) In most immunocompetent individuals, including children

and pregnant women, the infection goes unnoticed. In

approximately 10% of patients it causes a self-limiting

illness, most common in adults aged 25–35 years.

2) The most common presenting feature is painless

lymphadenopathy, either local or generalised. In

particular, the cervical nodes are involved, but

mediastinal, mesenteric or retroperitoneal groups may be

Unit 4 - Infectious disease

40

affected. The spleen is seldom palpable. Most patients

have no systemic symptoms, but some complain of

malaise, fever, fatigue, muscle pain, sore throat and

headache. Complete resolution usually occurs within a

few months, although symptoms and lymphadenopathy

tend to fluctuate unpredictably and some patients do not

recover completely for a year or more.

3) Very infrequently, patients may develop encephalitis,

myocarditis, polymyositis, pneumonitis or hepatitis.

4) Retinochoroiditis is nearly always the result of congenital

infection but has also been reported in acquired disease.

Congenital toxoplasmosis

Acute toxoplasmosis, mostly subclinical, affects 0.3– 1%

of pregnant women, with an approximately 60%

transmission rate to the fetus which increases with

increasing gestation.

Seropositive females infected 6 months before conception

have no risk of fetal transmission.

Congenital disease affects approximately 40% of infected

fetuses, and is more likely and more severe with infection

early in gestation. Many fetal infections are subclinical at

birth but long term sequelae include retinochoroiditis,

microcephaly and hydrocephalus.

Investigations

1) Immunocompromised patients diagnosis often requires

direct detection of parasites.

2) Serology is often used in immunocompetent individuals.

a. The Sabin–Feldman dye test (indirect fluorescent

antibody test), which detects IgG antibody. Recent

infection is indicated by a fourfold or greater increase in

titre when paired sera are tested in parallel. Peak titres of

1/1000 or more are reached within 1–2 months of the

onset of infection, and the dye test then becomes an

unreliable indicator of recent infection. The detection of

significant levels of Toxoplasma-specific IgM antibody

may be useful in confirming acute infection. False

positives or persistence of IgM antibodies for years after

infection make interpretation difficult; however, negative

IgM antibodies virtually rule out acute infection.

b. During pregnancy it is critical to differentiate between

recent & past infection; the presence of high-avidity IgG

antibodies excludes infection acquired in the preceding 3–

4 months.

3) If necessary, the presence of Toxoplasma organisms in a

lymph node biopsy can be sought by staining sections

histochemically with T. gondii antiserum, or by the use of

PCR to detect Toxoplasma-specific DNA.

Management

1) In immunocompetent subjects uncomplicated toxoplasmosis

is self-limiting and responds poorly to antimicrobial therapy.

2) Treatment with pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine and folinic

acid is therefore usually reserved for rare cases of severe

or progressive disease, and for infection in

immunocompromised patients.

3) In a pregnant woman with an established recent infection,

spiramycin (3 g daily in divided doses) should be given

until term. Once fetal infection is established, treatment

with sulfadiazine and pyrimethamine plus calcium

folinate is recommended (spiramycin does not cross the

placental barrier).

Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is caused by unicellular flagellate

intracellular protozoa belonging to the genus Leishmania

(order Kinetoplastidae). There are 21 leishmanial species

which cause several diverse clinical syndromes, which

can be placed into three broad groups:

• Visceral leishmaniasis (VL, kala-azar)

• Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL)

• Mucosal leishmaniasis (ML).

Epidemiology and transmission

Zoonotic transmission of parasites from animals (chiefly

canine and rodent reservoirs) to humans through

phlebotomine sandfly vectors, Humans are the only

known reservoir (anthroponotic) in major VL foci in India

and for transmission of leishmaniasis between injection

drug-users.

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL, kala-azar)

VL is caused by the protozoon Leishmania donovani

complex including:

1- L. donovani, 2- L. infantum. 3- L. chagasi.

India, Sudan, Bangladesh and Brazil account for 90% of

cases of VL, while other affected regions include the

Mediterranean, East Africa, China, Arabia, and other

South American countries .

In addition to sandfly transmission,

VL has also been reported to follow blood transfusion and

disease can present unexpectedly in immunosuppressed

patients—for example, after renal transplantation and in

HIV infection. The great majority of people infected

remain asymptomatic.

Unit 4 - Infectious disease

41

In visceral diseases the spleen, liver, bone marrow and

lymph nodes are primarily involved.

Clinical features

On the Indian subcontinent adults and children are equally

affected; on other continents VL is predominantly a

disease of small children and infants, except in adults with

HIV co-infection.

The incubation period ranges from weeks to months

(occasionally several years).

1) The first sign of infection is High fever, usually

accompanied by rigor and chills. Fever intensity decreases

over time and patients may become afebrile for

intervening periods ranging from weeks to months. This is

followed by a relapse of fever, often of lesser intensity.

2) Splenomegaly develops quickly in the first few weeks and

becomes massive as the disease progresses.

3) Moderate hepatomegaly occurs later.

4) Lymphadenopathy is seen in the majority of cases in

Africa, the Mediterranean and South America, but is rare

on the Indian subcontinent.

5) Blackish discoloration of the skin, from which the disease

derived its name, kala-azar (the Hindi word for ‘black

fever’), is a feature of advanced illness & is now rarely seen

6) Pancytopenia is a common feature. Moderate to severe

anaemia develops rapidly, and can result in congestive

cardiac failure and associated clinical features.

Thrombocytopenia, often compounded by hepatic

dysfunction, may result in bleeding from the retina,

gastrointestinal tract and nose.

7) In advanced illness, hypoalbuminaemia may manifest as

pedal oedema, ascites and anasarca (gross generalised

oedema and swelling).

8) As the disease advances, there is profound

immunosuppression.and secondary infections are very

common. These include tuberculosis, pneumonia, severe

amoebic or bacillary dysentery, gastroenteritis, herpes

zoster and chickenpox. Skin infections, boils, cellulitis

and scabies are common.

9) Without adequate treatment most patients with clinical

VL die.

Investigations

1) Pancytopenia is the most dominant feature, with

granulocytopenia and monocytosis.

2) Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinaemia, chiefly IgG

followed by IgM, and hypoalbuminaemia are seen later.

3) Demonstration of amastigotes (Leishman–Donovan bodies)

in splenic smears is the most efficient means of diagnosis,

with 98% sensitivity); however, it carries a risk of serious

haemorrhage in inexperienced hands. Safer methods, such

as bone marrow or lymph node smears, are not as sensitive.

Parasites may be demonstrated in buffy coat smears,

especially in immunosuppressed patients. Sensitivity can be

improved by culturing the aspirate material or by PCR for

DNA detection and species identification, but these tests

can only be performed in specialised laboratories.

4) Serodiagnosis, by ELISA or immunofluorescence

antibody test, is employed in developed countries.

5) In endemic regions, a highly sensitive and specific direct

agglutination test using stained promastigotes and rapid

immunochromatographic k39 strip test have become

popular. These tests remain positive for several months

after cure has been achieved, so do not predict response to

treatment or relapse. A significant proportion of the

healthy population in an endemic region will be positive

for these tests due to past exposure.

6) Formal gel (aldehyde) for detection of raised globulin has

limited value and should not be employed for the

diagnosis of VL.

Management

1) Pentavalent antimonials

2) Amphotericin B, The antifungal drug,

3) Other drugs

a. The oral drug miltefosine, an alkyl phospholipid, has been

approved in several countries for the treatment of VL.

b. Paromomycin is an aminoglycoside that has undergone

trials in India and Africa India for the treatment of VL.

c. Pentamidine isetionate was used to treat Sb-refractory

patients with VL.

Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL)

After treatment and apparent recovery from the visceral

disease in India and Sudan, some patients develop

dermatological manifestations due to local parasitic infection.

Clinical features

In India dermatological changes occur in a small minority

of patients 6 months to ≥3 years after the initial infection.

They are seen as macules, papules, nodules (most

frequently) and plaques which have a predilection for the

face, especially the area around the chin. The face often

appears erythematous Hypopigmented macules can occur

over all parts of the body and are highly variable in extent

and location. There are no systemic symptoms and no

spontaneous healing.

Unit 4 - Infectious disease

42

Investigations and management

The diagnosis is clinical, supported by demonstration of

scanty parasites in lesions by slit-skin smear and culture.

Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry may

demonstrate the parasite in skin tissues.

In the majority of patients serological tests (direct

agglutination test or k39 strip tests) are positive.

Treatment of PKDL is difficult. In India, sodium

stiobogluconate for 120 days or several courses of

amphotericin B infusions are required.

Cutaneous and mucosal leishmaniasis

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL)

CL (oriental sore) occurs in both the Old World and the

New World (the Americas). Transmission is by sandfly .

In the Old World, CL is mild. It is found around the

Mediterranean basin, throughout the Middle East and

Central Asia as far as Pakistan, and in sub-Saharan West

Africa and Sudan .

The causative organisms for Old World zoonotic CL are

L. major, L. tropica and L. aethiopica .

Anthroponotic CL is caused by L. tropica, and is confined

to urban or suburban areas of the Old World. Afghanistan

is currently the biggest focus, but infection is endemic in

Pakistan, the western deserts of India, Iran, Iraq, Syria and

other areas of the Middle East.

New World CL is a more significant disease, which may

disfigure the nose, ears and mouth & is causedby the L.

mexicana complex (comprising L. mexicana, L. amazonensis

& L. venezuelensis) and by the Viannia subgenus L. (V.)

brasiliensis complex (comprising L. (V.) guyanensis, L.

(V.) panamensis, L. (V.) brasiliensis and L. (V.) peruviana).

CL is commonly imported and should be considered in

the differential diagnosis of an ulcerating skin lesion,

especially in travellers who have visited endemic areas of

the Old World or forests in Central and South America.

Clinical features

The incubation period is typically 2–3 months (range 2

weeks to 5 years).

In all types of CL, the common feature is development of

a papule followed by ulceration of the skin with raised

borders, usually at the site of the bite of the vector.

Lesions, single or multiple, start as small red papules that

increase gradually in size, reaching 2–10 cm in diameter.

A crust forms, overlying an ulcer with a granular base .

These ulcers develop a few weeks or months after the

bite. There can be satellite lesions, especially in L. major

and occasionally in L. tropica infections.

Regional lymphadenopathy, pain, pruritus and secondary

bacterial infections may occur.

Clinically, lesions of L. mexicana and L. peruviana closely

resemble those seen in the Old World, but lesions on the

pinna of the ear are common & are chronic & destructive.

L. mexicana is responsible for chiclero ulcers, the self-

healing sores of Mexico.

If immunity is good, there is usually spontaneous healing

in L. tropica, L. major and L. mexicana lesions. In some

patients with anergy to Leishmania, the skin lesions of L.

aethiopica, L. mexicana and L. amazonensis infections

progress to the development of diffuse CL; this is

characterized by spread of the infection from the initial

ulcer, usually on the face, to involve the whole body in

the form of non-ulcerative nodules. Occasionally, in L.

tropica infections, sores that have apparently healed

relapse persistently (recidivans or lupoid leishmaniasis).

Mucosal leishmaniasis (ML)

The Viannia subgenus extends widely from the Amazon

basin as far as Paraguay and Costa Rica, and is

responsible for deep sores and ML.

In L. (V.) brasiliensis complex infections, cutaneous

lesions may be followed by mucosal spread of the disease

simultaneously or even years later. between 2% and 40%

of infected persons develop ‘espundia’, metastatic lesions

in the mucosa of the nose or mouth. This is characterised

by thickening and erythema of the nasal mucosa, typically

starting at the junction of the nose and upper lip. Later,

ulceration develops. The lips, soft palate, fauces and

larynx may also be invaded and destroyed, leading to

considerable suffering and deformity.

There is no spontaneous healing, and death may result

from severe respiratory tract infections due to massive

destruction of the pharynx.

Investigations in CL and ML

1) CL is often diagnosed on the basis of clinical

characteristics of the lesions

2) Parasitological confirmation to detect Amastigotes on a

slit-skin smear with Giemsa staining; is also important to

exclude other disease.

3) Cultured from the sores early during the infection.

Management of CL and ML

1) Small lesion: may a- self-heal or treated by b- freezing

with liquid nitrogen or curettage.

2) In CL, topical application of paromomycin 15% plus

methylbenzethonium chloride 12% is beneficial.

Unit 4 - Infectious disease

43

3) Intralesional antimony (Sb: 0.2–0.8 mL/lesion) up to 2 g

seems to be rapidly effective in suitable cases, well

tolerated and economic, and is safe in patients with

cardiac, liver or renal diseases.

4) In ML, and in( CL when the lesions are multiple or in a

disfiguring site),

a- parenteral Sb in a dose of 20 mg/kg/day (usually given

for 20 days for CL and 28 days for ML),

b- Conventional or liposomal amphotericin B (see

treatment of VL above).

5) Two to four doses (2–4 mg/kg) of alternate-day

administration of pentamidine are effective in New World

CL. In ML, 8 injections of pentamidine (4 mg/kg on

alternate days) cure the majority of patients.

6) Ketoconazole 600 mg daily for 4 weekshas shown some

potential against L. mexicana infection.

Gastrointestinal protozoal infections

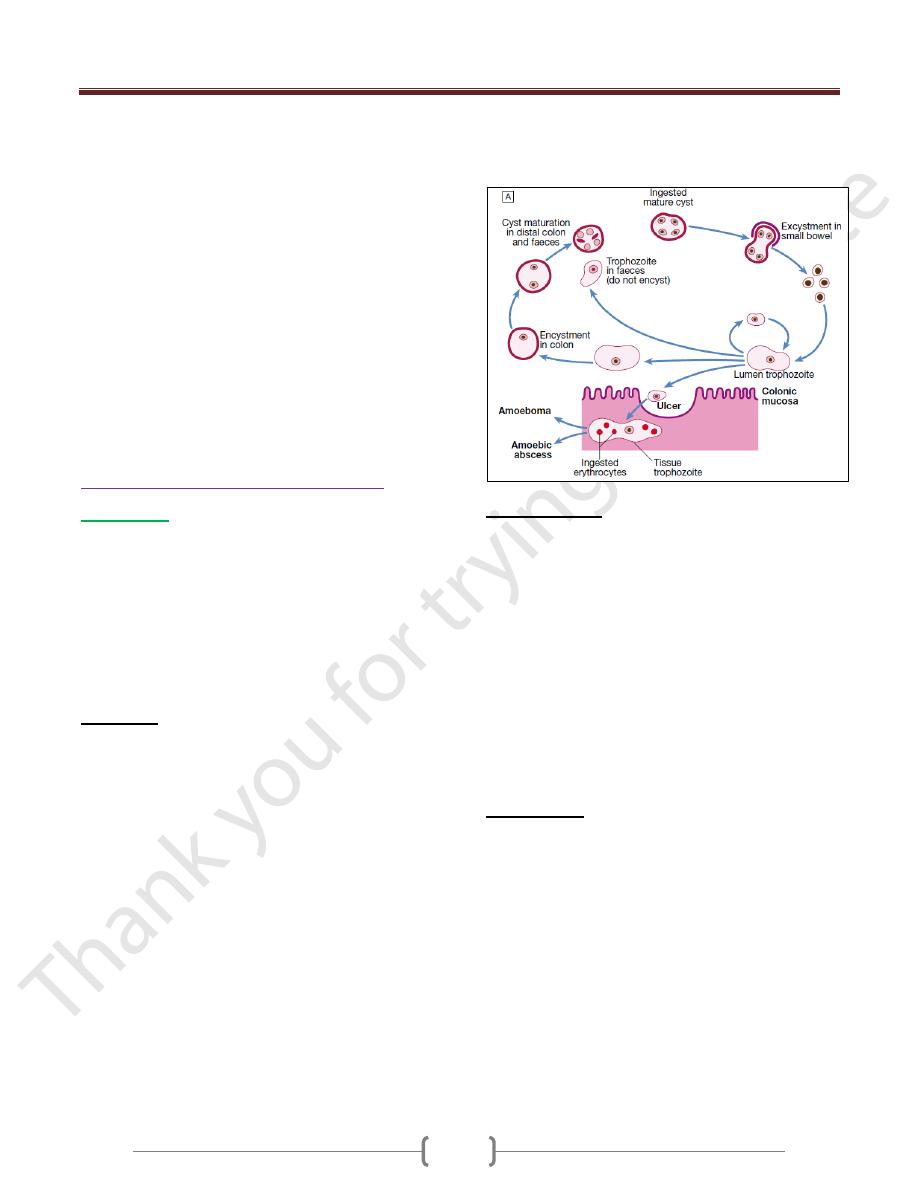

Amoebiasis

Amoebiasis is caused by Entamoeba histolytica, which is

spread between humans by its cysts.

Two non-pathogenic Entamoeba species (E. dispar and E.

moshkovskii) are morphologically identical to E.

histolytica, and are distinguishable only by molecular

techniques, isoenzyme studies or monoclonal antibody

typing. However, only E. histolytica causes amoebic

dysentery or liver abscess.

Pathology

Cysts of E. histolytica are ingested in water or uncooked

foods contaminated by human faeces.

In the colon, vegetative trophozoite forms emerge from

the cysts. The parasite may invade the mucous membrane

of the large bowel, producing lesions that are maximal in

the caecum but found as far down as the anal canal. These

are flask-shaped ulcers, varying greatly in size and

surrounded by healthy mucosa. A localised granuloma

(amoeboma), presenting as a palpable mass in the rectum

or a filling defect in the colon on radiography, is a rare

complication which should be differentiated from colonic

carcinoma. Amoebic ulcers may cause severe

haemorrhage but rarely perforate the bowel wall.

Amoebic trophozoites can emerge from the vegetative

cyst from the bowel and be carried to the liver in a portal

venule. They can multiply rapidly and destroy the liver

parenchyma, causing an abscess.

The liquid contents at first have a characteristic pinkish

colour which may later change to chocolate brown (like

anchovy sauce).

Cutaneous amoebiasis, though rare, causes progressive

genital, perianal or peri-abdominal surgical wound ulceration.

Clinical features

Intestinal amoebiasis—amoebic dysentery

1) Most amoebic infections are asymptomatic.

2) The incubation period of amoebiasis ranges from 2 weeks

to many years, followed by a chronic course with

abdominal pains and two or more unformed stools a day.

3) Offensive diarrhoea alternating with constipation, and

blood or mucus in the stool, are common.

4) There may be abdominal pain, especially right lower

quadrant (which may simulate acute appendicitis).

5) A dysenteric presentation with passage of blood,

simulating bacillary dysentery or ulcerative colitis, occurs

particularly in older people, in the puerperium and with

superadded pyogenic infection of the ulcers.

Investigations

1) The stool & any exudate should be examined at once under

the microscope for motile trophozoites containing RBCs.

Movements cease rapidly as the stool preparation cools.

2) Several stools may need to be examined in chronic

amoebiasis before cysts are found. Sigmoidoscopy may

reveal typical flask-shaped ulcers, which should be

scraped and examined immediately for E. histolytica.

3) In endemic areas one-third of the population are

symptomless passers of amoebic cysts.

4) Serum antibodies are detectable by immunofluorescence in

over 95% of patients with hepatic amoebiasis & intestinal

amoeboma, but in only about 60% of dysenteric amoebiasis

5) DNA detection by PCR shown to be useful in diagnosis of

E. histolytica infections but is not generally available.

Unit 4 - Infectious disease

44

Amoebic liver abscess

1) The abscess is usually found in the right hepatic lobe.

2) There may not be associated diarrhoea. Early symptoms

may be local discomfort only and malaise; later, a

swinging temperature and sweating may develop, usually

without marked systemic symptoms or associated

cardiovascular signs.

3) An enlarged, tender liver, cough and pain in the right

shoulder are characteristic, but symptoms may remain

vague and signs minimal.

4) A large abscess may penetrate the diaphragm and rupture

into the lung, from where its contents may be coughed up.

5) Rupture into the pleural cavity, the peritoneal cavity or

pericardial sac is less common but more serious.

Investigations

1) An amoebic abscess of the liver is suspected on clinical

grounds; there is often a neutrophil leucocytosis and a

raised right hemidiaphragm on chest X-ray.

2) Confirmation is by ultrasonic scanning.

3) Aspirated pus from an amoebic abscess has the

characteristic anchovy sauce or chocolate brown

appearance but only rarely contains free amoebae .

Management

1) Intestinal and early hepatic amoebiasis responds quickly

to oral metronidazole (800 mg 8-hourly for 5–10 days) or

other long-acting nitroimidazoles like tinidazole or

ornidazole (both in doses of 2 g daily for 3 days).

Nitaxozanide (500 mg 12-hourly for 3 days) is an

alternative drug.

2) Either diloxanide furoate or paromomycin, in doses of

500 mg orally 8-hourly for 10 days after treatment, should

be given to eliminate luminal cysts.

3) If a liver abscess is large or threatens to burst, or if the

response to chemotherapy is not prompt, aspiration is

required and is repeated if necessary.

Rupture of an abscess into the pleural cavity, pericardial

sac or peritoneal cavity necessitates immediate aspiration

or surgical drainage. Small serous effusions resolve

without drainage.

Giardiasis

Infection with Giardia lamblia is found world-wide and is

common in the tropics.

In cystic form it remains viable in water for up to 3 months

and infection usually occurs by ingesting contaminated

water. Its flagellar trophozoite form attaches to the

duodenal and jejunal mucosa, causing inflammation.

Incubation period of 1–3 weeks,

Clinical features

There is diarrhoea, abdominal pain, weakness, anorexia,

nausea and vomiting.

Investigations

1) On examination there may be abdominal distension and

tenderness. Stools obtained at 2–3-day intervals should be

examined for cysts.

2) Duodenal or jejunal aspiration by endoscopy gives a

higher diagnostic yield.

3) The ‘string test’ may be used, in which one end of a piece

of string is passed into the duodenum by swallowing,

retrieved after an overnight fast, and expressed fluid

examined for the presence of G. lamblia trophozoites.

4) A number of stool antigen detection tests are available.

Jejunal biopsy specimens may show G. lamblia on the

epithelial surface.

Management

Treatment is with a single dose of tinidazole 2 g, or

metronidazole 400 mg 8-hourly for 10 days.

Cryptosporidiosis

Cryptosporidium spp. are coccidian protozoal parasites of

humans and domestic animals.

Infection is acquired by the faecal–oral route through

contaminated water supplies.

The incubation period is approximately 7–10 days, and

is followed by watery diarrhoea and abdominal cramps.

The illness is usually self-limiting, but in

immunocompromised patients, especially those with HIV,

the illness can be devastating, with persistent severe

diarrhea and substantial weight loss.

Cyclosporiasis

Cyclospora cayetanensis is a globally distributed

coccidian protozoal parasite of humans.

Infection is acquired by ingestion of contaminated water.

The incubation period is approximately 2–11 days, and

is followed by acute onset of diarrhoea with abdominal

cramps, which may remit and relapse.

Although usually self-limiting, the illness may last as long

as 6 weeks with significant associated weight loss and

malabsorption, and is more severe in

immunocompromised individuals.

Diagnosis is by detection of oöcysts on faecal

microscopy.

Treatment may be necessary in a few cases & the agent

of choice is co-trimoxazole 960 mg 12-hourly for 7 days.