Unit 2: Bacteriology

00

Lecture 3 - The Physiology of

Metabolism and Growth in Bacteria

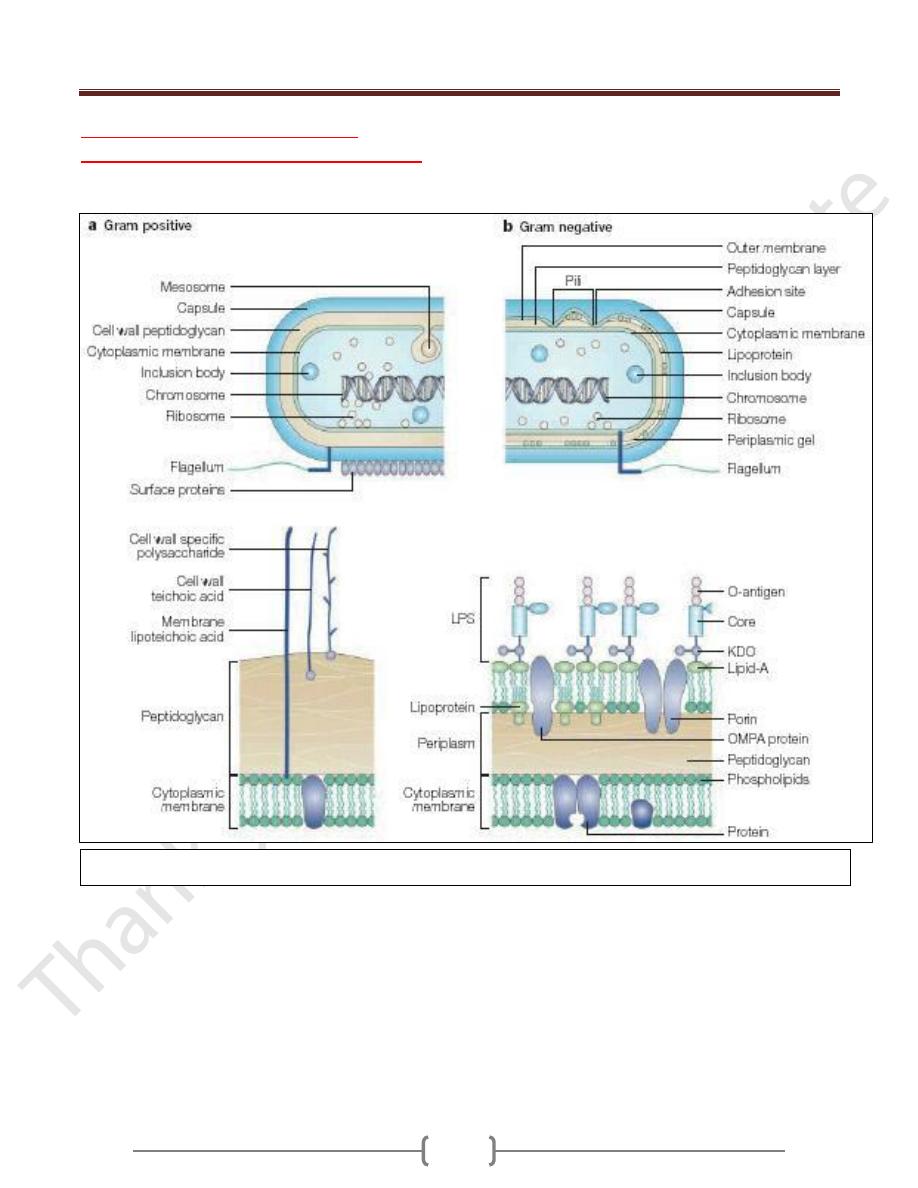

Fine structure of Both: The Cell Wall of Gram-Positive Bacteria

(left) and the

Cell Wall

of Gram-Negative Bacteria (right)

Unit 2: Bacteriology

06

Types of Metabolism

Metabolism is the totality of chemical reactions occurring

in bacterial cells. They can be subdivided into anabolic

(synthetic) reactions that consume energy and catabolic

reactions that supply energy. In the anabolic, endergonic

reactions, the energy requirement is consumed in the form

of light or chemical energy—by photosynthetic or

chemosynthetic bacteria, respectively. Catabolic reactions

supply both energy and the basic structural elements for

synthesis of specific bacterial molecules. Bacteria that

feed on inorganic nutrients are said to be lithotrophic,

those that feed on organic nutrients are organotrophic.

Human pathogenic bacteria are always chemosynthetic,

organotrophic bacteria (or chemo-organotrophs).

Catabolic Reactions

Organic nutrient substrates are catabolized in a wide

variety of enzymatic processes that can be schematically

divided into four phases:

Digestion

. Bacterial exoenzymes split up the nutrient

substrates into smaller molecules outside the cell. The

exoenzymes represent important pathogenicity factors in

some cases.

Uptake

. Nutrients can be taken up by means of passive

diffusion or, more frequently, specifically by active

transport through the membrane (s). Cytoplasmic

membrane permeases play an important role in these

processes.

Preparation for oxidation

. Splitting off of carboxyl

and amino groups, phosphorylation, etc.

Oxidation.

This process is defined as the removal of

electrons and H+ ions. The substance to which the H2

atoms are transferred is called the hydrogen acceptor.

The two basic forms of oxidation are defined by

the final hydrogen acceptor.

o Respiration. Here oxygen is the hydrogen acceptor. In

anaerobic respiration, the O2 that serves as the hydrogen

acceptor is a component of an inorganic salt.

o Fermentation. Here an organic compound serves as the

hydrogen acceptor. The main difference between

fermentation and respiration is the energy yield, which

can be greater from respiration than from fermentation for

a given nutrient substrate by as much as a factor of 10.

Fermentation processes involving microorganisms are

designated by the final product, e.g., alcoholic

fermentation, butyric acid fermentation, etc.

The energy released by oxidation is stored as chemical

energy in the form of a thioester (e.g., acetyl-CoA) or

organic phosphates (e.g., ATP).

The role of oxygen. Oxygen is activated in one of

three ways:

o Transfer of 4e

–

to O

2

, resulting in 2 oxygen ions (2 O2

–

).

o Transfer of 2e

–

to O

2

resulting in 1 peroxide anion(1 O2

2–

o Transfer of 1e– to O2, resulting in one superoxide anion

(1 O2 –).

Hydrogen peroxide and the highly reactive superoxide

anion are toxic and therefore must undergo further

conversion immediately.

Bacteria are categorized as the following

according to their O2-related behavior:

o Facultative anaerobes. These bacteria can oxidize

nutrient substrates by means of both respiration and

fermentation.

o Obligate aerobes. These bacteria can only reproduce in

the presence of O2.

o Obligate anaerobes. These bacteria die in the presence of

O2. Their metabolism is adapted to a low redox potential

and vital enzymes are inhibited by O2.

o Aerotolerant anaerobes. These bacteria oxidize nutrient

substrates without using elemental oxygen although,

unlike obligate anaerobes, they can tolerate it.

Basic mechanisms of catabolic metabolism.

The principle of the biochemical unity of life asserts that

all life on earth is, in essence, the same. Thus, the

catabolic intermediary metabolism of bacteria is, for the

most part, equivalent to what takes place in eukaryotic

cells. The reader is referred to textbooks of general

microbiology for exhaustive treatment of the pathways of

intermediary bacterial metabolism.

Anabolic Reactions

It is not possible to go into all of the biosynthetic feats of

bacteria here. Suffice it to say that they are, on the whole,

quite astounding. Some bacteria (E. coli) are capable of

synthesizing all of the complex organic molecules that

they are comprised of, from the simplest nutrients in a

very short time. These capacities are utilized in the field

of microbiological engineering. Antibiotics, amino acids,

and vitamins are produced with the help of bacteria. Some

bacteria are even capable of using aliphatic hydrocarbon

compounds as an energy source. Such bacteria can “feed”

on paraffin or even raw petroleum. Culturing of bacteria

Unit 2: Bacteriology

06

in nutrient mediums based on methanol is an approach

being used to produce biomas in addition to many other

ones.

Metabolic Regulation: Bacteria are highly efficient

metabolic regulators, coordinating each individual

reaction with other cell activities and with the available

nutrients as economically and rationally as possible.

Growth and Culturing of Bacteria

Nutrients

The term bacterial culture refers to proliferation of

bacteria with a suitable nutrient substrate. A nutrient

medium in which chemoorganotrophs are to be

cultivated must have organic energy sources (H2

donors) and H2 acceptors. Other necessities include

sources of carbon and nitrogen for synthesis of specific

bacterial compounds as well as minerals such as

sulfur, phosphorus, calcium, magnesium, and trace

elements as enzyme activators. Some bacteria also

require “growth factors,” i.e., organic compounds they

are unable to synthesize themselves. Depending on the

bacterial species involved, the nutrient medium must

contain certain amounts of O2 and CO2 and have

certain pH and osmotic pressure levels. Growth

factors are required in small amounts by cells because

they fulfill specific roles in biosynthesis. The need for a

growth factor results from either a blocked or missing

metabolic pathway in the cells. Growth factors are

organized into three categories:

1. Purines and pyrimidines: required for synthesis of

nucleic acids (DNA and RNA).

2. Amino acids: required for the synthesis of proteins.

3. Vitamins: needed as coenzymes and functional groups

of certain enzymes.

Some bacteria (e.g E. coli) do not require any growth

factors: they can synthesize all essential purines,

pyrimidines, amino acids and vitamins, starting with their

carbon source, as part of their own intermediary

metabolism. Certain other bacteria (e.g. Lactobacillus)

require purines, pyrimidines, vitamins and several amino

acids in order to grow. These compounds must be added

in advance to culture media that are used to grow these

bacteria. The growth factors are not metabolized directly

as sources of carbon or energy, rather they are assimilated

by cells to fulfill their specific role in metabolism. Mutant

strains of bacteria that require some growth factor not

needed by the wild type (parent) strain are referred to as

auxotrophs. Thus, a strain of E. coli that requires the

amino acid tryptophan in order to grow would be called a

tryptophan auxotroph and would be designated E. colitrp-.

The function(s) of these vitamins in essential enzymatic

reactions gives a clue why, if the cell cannot make the

vitamin, it must be provided exogenously in order for

growth to occur.

Growth and Cell Death

Bacteria reproduce asexually by means of simple

transverse binary fission. Their numbers (n) increase

logarithmically (n = 2G). The time required for a

reproduction cycle (G) is called the generation time (g)

and can vary greatly from species to species. Fast-

growing bacteria cultivated in vitro have a generation

time of 15–30

minutes. The same bacteria may take

hours to reproduce in vivo. Obligate anaerobes grow

much more slowly than aerobes; this is true in vitro as

well. Tuberculosis bacteria have an in-vitro generation

time of 12–24 hours. Of course the generation time also

depends on the nutrient content of the medium.

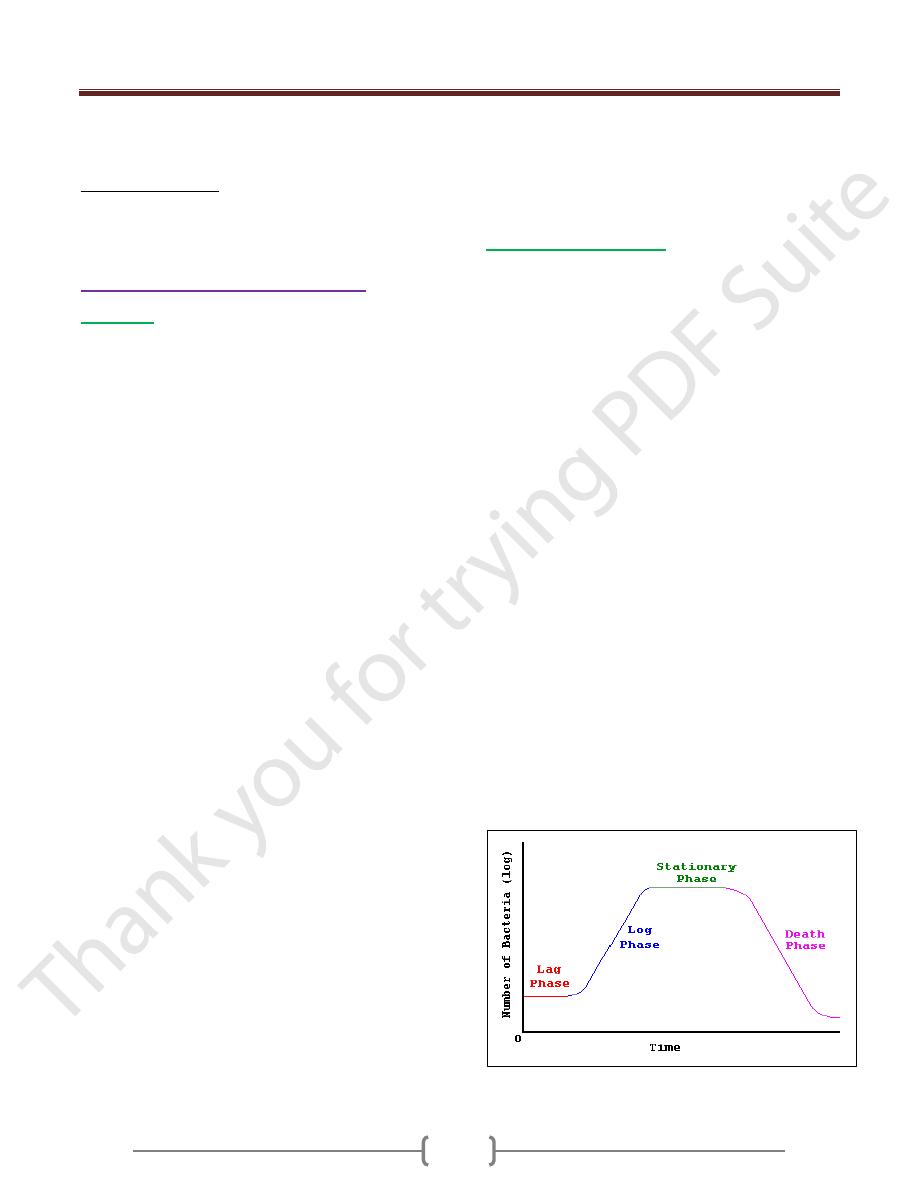

The so-called normal growth curve for bacteria is

obtained by inoculating a nutrient broth with bacteria the

metabolism of which is initially quiescent, counting them

at intervals and entering the results in a semilog

coordinate system . The lag phase is characterized by an

increase in bacterial mass per unit of volume, but no

increase in cell count. During this phase, the metabolism

of the bacteria adapts to the conditions of the nutrient

medium. In the following log (or exponential) phase , the

cell count increases logarithmically up to about 109/ml.

This is followed by growth deceleration and transition to

the stationary phase due to exhaustion of the nutrients and

the increasing concentration of toxic metabolites. Finally,

death phase processes begin. The generation time can

only be determined during log phase, either graphically or

by determining the cell count (n) at two different times.

Normal Growth Curve of a Bacterial Culture

Unit 2: Bacteriology

06

The summary:

Human pathogenic bacteria are

chemosynthetic and organotrophic (chemo-

organotrophic). They derive energy from the breakdown

of organic nutrients and use this chemical energy both for

resynthesis and secondary activities. Bacteria oxidize

nutrient substrates by means of either respiration or

fermentation. In respiration, O2 is the electron and proton

acceptor, in fermentation an organic molecule performs

this function. Human pathogenic bacteria are classified in

terms of their O2 requirements and tolerance as

facultative anaerobes, obligate aerobes, obligate

anaerobes, or aerotolerant anaerobes. Nutrient broth or

agar is used to cultivate bacteria. Nutrient agar contains

the inert substrate agarose, which liquefies at 100°C and

gels at 45°C. Selective and indicator mediums are used

frequently in diagnostic bacteriology. Bacteria reproduce

by means of simple transverse binary fission. The time

required for complete cell division is called generation

time. The in-vitro generation time of rapidly proliferating

species is 15–30 minutes. This time is much longer in

vivo. The growth curve for proliferation in nutrient broth

is normally characterized by the phases lag, log (or

exponential) growth, stationary growth, and death.