Unit 12: Lung (Diseases of respiratory system)

071

Atelectasis (collapse)

It is loss of lung volume caused by inadequate expansion

of airspaces. It results in shunting of inadequately

oxygenated blood from pulmonary arteries into veins,

thus giving rise to a ventilation-perfusion imbalance &

hypoxia.

Atelectasis is classified into three forms:-

1) Resorption Atelectasis

Resorption atelectasis occurs when an obstruction

prevents air from reaching distal airways. Depending on

the level of airway obstruction, an entire lung, a complete

lobe, or one or more segments may be involved.

Causes of resorption collapse is obstruction of a bronchus

by a mucous or mucopurulent plug. This frequently

occurs postoperatively, also complicate bronchial asthma,

bronchiectasis, chronic bronchitis, or the aspiration of

foreign bodies.

2) Compression Atelectasis

This usually associated with accumulations of fluid,

blood, or air within the pleural cavity, which

mechanically collapse the adjacent lung. This is a frequent

occurrence with pleural effusions, caused most commonly

by congestive heart failure (CHF). Leakage of air into the

pleural cavity (pneumothorax) also leads to compression

atelectasis.

Basal atelectasis resulting from the elevated position of

the diaphragm commonly occurs in

1- bedridden patients

2- patients with ascites,

3- patients during and after surgery.

3) Contraction Atelectasis

Occurs when either local or generalized fibrotic changes

in the lung or pleura hamper expansion and increase

elastic recoil during expiration.

Acute lung injury

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)

ARDS is a clinical syndrome caused by diffuse alveolar

capillary and epithelial damage. There is usually rapid

onset of life-threatening respiratory insufficiency,

cyanosis, and severe arterial hypoxemia that is refractory

to oxygen therapy and that may progress to multisystem

organ failure. The histologic manifestation of ARDS in

the lungs is known as diffuse alveolar damage. ARDS is

associated with either direct injury to the lung or indirect

injury in the setting of a systemic process.

Pathogenesis

The alveolar capillary membrane is formed by 2 separate

barriers: the microvascular endothelium and the alveolar

epithelium. In ARDS the integrity of this barrier is

compromised by either endothelial or epithelial injury, or both.

The acute consequences of damage to the alveolar

capillary membrane include

1- Creased vascular permeability →alveolar flooding,

2- Loss of diffusion capacity

3- Widespread surfactant abnormalities caused by damage

to type II pneumocytes recent work suggests that in

ARDS, lung injury is caused by an imbalance of pro-

inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators. Nuclear

factor κB (NF-κB), whose activation is tightly regulated

under normal conditions shifting the balance in favor of

pro-inflammatory state. As early as 30 minutes after an

acute insult, there is increased synthesis of interleukin 8

(IL-8), a potent neutrophil chemotactic and activating

agent, by pulmonary macrophages as well asIL-1 &

(TNF), leads to endothelial activation, and pulmonary

microvascular sequestration and activation of neutrophils.

Activated neutrophils release a variety of products (e.g.,

oxidants, proteases, platelet-activating factor, &

leukotrienes) that cause damage to the alveolar epithelium

and maintain the inflammatory cascade. Combined assault

on the endothelium and epithelium perpetuate vascular

leakiness and loss of surfactant that render the alveolar unit

unable to expand. It should be noted that the destructive

forces unleashed by neutrophils can be counteracted by an

array of endogenous antiproteases, antioxidants, and anti-

inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-10) that are upregulated by

pro-inflammatory cytokines. In the end, it is the balance

between the destructive & protective factors that determines

the degree of tissue injury and clinical severily of ARDS.

Causes of ARDS

Direct Lung Injury

Indirect Lung Injury

Pneumonia

Sepsis

Aspiration of gastric contents

Severe trauma with shock

Uncommon Causes

Pulmonary contusion

Cardiopulmonary bypass

Fat embolism

Acute pancreatitis

Near-drowning

Drug overdose

Inhalational injury

Transfusion of blood products

Uremia

Morphology

In the acute phase of ARDS the lungs are dark red, firm,

airless, and heavy. Microscopically, there is capillary

congestion, necrosis of alveolar epithelial cells, interstitial

and intra-alveolar edema and hemorrhage, collections of

Unit 12: Lung (Diseases of respiratory system)

070

neutrophils in capillaries. The most characteristic finding

is the presence of hyaline membranes, particularly lining

the distended alveolar ducts. consist of fibrin-rich edema

fluid admixed with remnants of necrotic epithelial cells.

Overall, the picture is remarkably similar to that seen in

respiratory distress syndrome in the newborn.

In the organizing stage there is marked proliferation of

type II pneumocytes in an attempt to regenerate the

alveolar lining. Resolution is unusual; more commonly

there is organization of the fibrin exudates, with resultant

intra-alveolar fibrosis. Marked thickening of the alveolar

septa caused by proliferation of interstitial cells and

deposition of collagen.

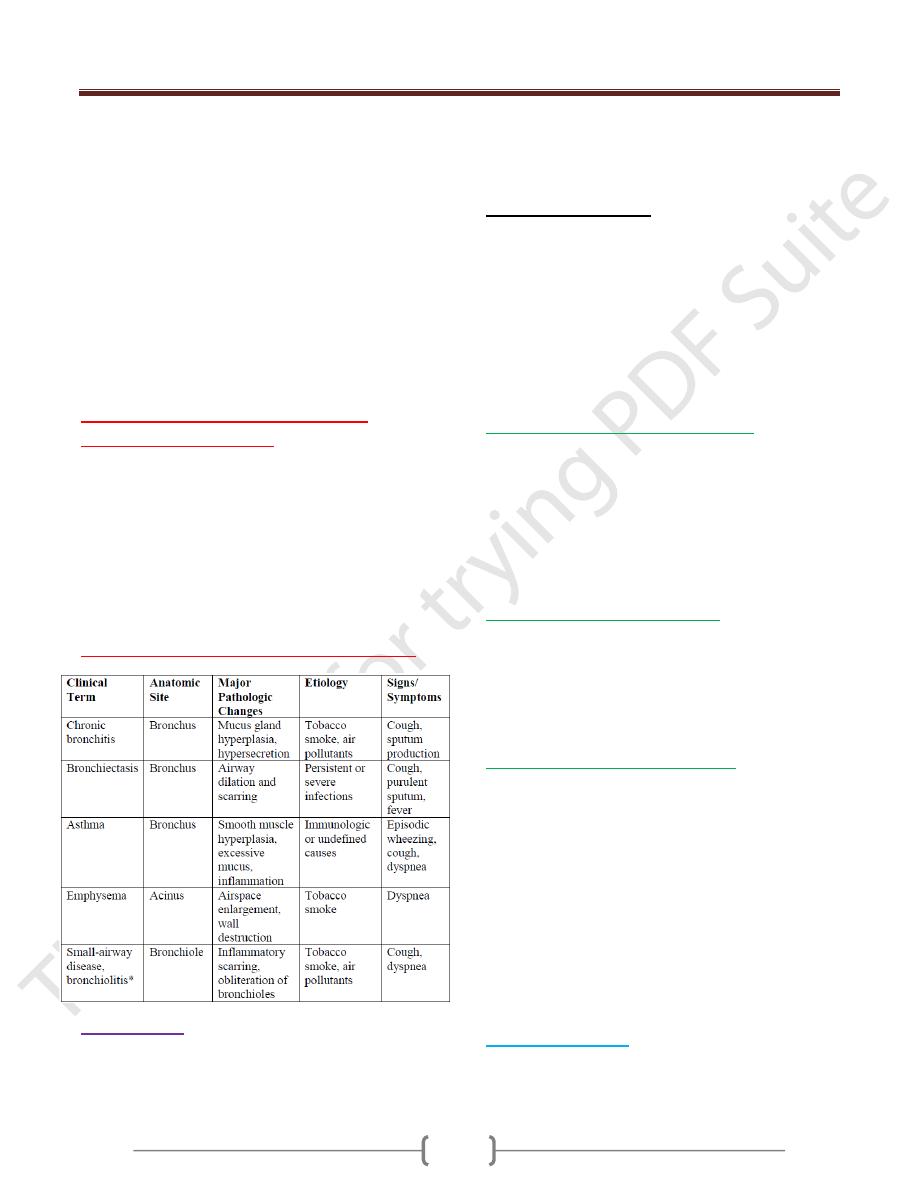

Obstructive versus restrictive

pulmonary diseases

Diffuse pulmonary diseases can be classified in 2 categories

(1) Obstructive disease (airway disease), characterized by

limitation of airflow usually resulting from an increase in

resistance caused by partial or complete obstruction at any

level, (2) Restrictive disease, characterized by reduced

expansion of lung parenchyma accompanied by decreased

total lung capacity.

Obstructive lung (airway) diseases

Emphysema

It characterized by abnormal permanent enlargement of the

airspaces distal to the terminal bronchioles, accompanied

by destruction of their walls without obvious fibrosis.

overinflation conditions in which enlargement of airspaces is

not accompanied by destruction e.g.the distention of airspaces

in the opposite lung after unilateral pneumonectomy

Types of Emphysema

Emphysema is classified according to its anatomic

distribution within the lobule; recall that the acinus is the

structure distal to terminal bronchioles, and a cluster of

three to five acini is called a lobule.

There are four major types of emphysema: (1)

centriacinar, (2) panacinar, (3) distal acinar, and (4)

irregular. Only the first two cause clinically significant

airway obstruction, with centriacinar emphysema being

about 20-times more common than panacinar disease.

1) Centriacinar (Centrilobular) Emphysema

In which the central or proximal parts of the acini, formed

by respiratory bronchioles, are affected, while distal

alveoli are spared. Thus, both emphysematous and normal

airspaces exist within the same acinus and lobule. The

lesions are more common and severe in the upper lobes,

particularly in the apical segments. commonly seen as a

consequence of cigarette smoking in people who do not

have congenital deficiency of α

1

-antitrypsin

2) Panacinar (Panlobular) Emphysema

In this type of emphysema, the acini are uniformly

enlarged from the level of the respiratory bronchiole to

the terminal blind alveoli. In contrast to centriacinar

emphysema, panacinar emphysema tends to occur more

commonly in the lower lung zones and is the type of

emphysema that occurs in α

1

-antitrypsin deficiency.

3) Distal Acinar (Paraseptal) Emphysema

In this form, the proximal portion of the acinus is normal

but the distal part is primarily involved. The emphysema

is more striking adjacent to the pleura, along the lobular

connective tissue septa, and at the margins of the lobules.

It occurs adjacent to areas of fibrosis, scarring, or

atelectasis and is usually more severe in the upper half of

the lungs. The characteristic findings are the presence of

multiple, contiguous, enlarged airspaces that range in

diameter from less than 0.5 mm to more than 2.0 cm,

sometimes forming cystlike structures that with

progressive enlargement are referred to as bullae. This

type of emphysema probably underlies many of the cases

of spontaneous pneumothorax in young adults.

4) Irregular Emphysema

Irregular emphysema, so named because the acinus is

irregularly involved, is almost invariably associated with

scarring, such as resulting from healed inflammatory

Unit 12: Lung (Diseases of respiratory system)

071

diseases. Although clinically asymptomatic, this may be

the most common form of emphysema.

Pathogenesis

Emphysema arising as a consequence of the protease-

antiprotease imbalance

The protease-antiprotease imbalance hypothesis is based

on the observation that patients with a genetic deficiency

of the antiprotease α

1

-antitrypsin have a markedly

enhanced tendency to develop pulmonary emphysema,

which is compounded by smoking. About 1% of all

patients with emphysema have this defect. α

1

-Antitrypsin,

normally present in serum, which is a major inhibitor of

proteases (particularly elastase) secreted by neutrophils

during inflammation.

α

1

-Antitrypsin is encoded by (Pi) locus on chromosome 14.

The following sequence is postulated:

1) 1-Neutrophils (the principal source of cellular proteases)

are normally sequestered in peripheral capillaries,

including those in the lung, and a few gain access to the

alveolar spaces.

2) 2-Any stimulus that increases either the number of

leukocytes (neutrophils and macrophages) in the lung or

the release of their protease-containing granules increases

proteolytic activity.

3) 3-With low levels of serum α

1

-antitrypsin, elastic tissue

destruction is unchecked and emphysema results.

In smokers, neutrophils and macrophages accumulate in

alveoli. The mechanism of inflammation is not entirely

clear, but possibly involves the direct chemo attractant

effects of nicotin , these activate the transcription factor

NF-κB, which switches on genes that encode TNF and

chemokines, including IL-8. These, in turn, attract and

activate neutrophils. Accumulated neutrophils are

activated and release their granules, rich in a variety of

cellular proteases (neutrophil elastase, proteinase 3, and

cathepsin G), resulting in tissue damage.

Smoking also enhances elastase activity in macrophages;

macrophage elastase is not inhibited by α

1

-antitrypsin and,

indeed, can proteolytically digest this antiprotease. There

is increasing evidence that in addition to elastase, matrix

metalloproteinases derived from macrophages and

neutrophils have a role in tissue destruction.

Morphology

The diagnosis and classification of emphysema depend

largely on the macroscopic appearance of the lung.

Panacinar emphysema, when well developed, produces

pale, voluminous lungs that often obscure the heart when

the anterior chest wall is removed at autopsy.

In centriacinar emphysema the lungs are a deeper pink

than in panacinar emphysema and less voluminous, unless

the disease is well advanced.

Generally, in centriacinar emphysema the upper two-

thirds of the lungs is more severely affected than the

lower lungs.

Histologically there is thinning and destruction of

alveolar walls. With advanced disease, adjacent alveoli

become confluent, creating large airspaces. Terminal and

respiratory bronchioles may be deformed because of the

loss of septa that help tether these structures in the

parenchyma. With the loss of elastic tissue in the

surrounding alveolar septa, there is reduced radial traction

on the small airways. As a result, they tend to collapse

during expiration-an important cause of chronic airflow

obstruction in severe emphysema. In addition to alveolar

loss, the number of alveolar capillaries is diminished.

Chronic Bronchitis

Is defined as a persistent productive cough for at least

3 consecutive months in at least 2 consecutive years. It

is common among cigarette smokers and urban dwellers

in smog-ridden cities; about 20% - 25% of men in the 40-

to 65-year age have the disease. Recurrent infections and

respiratory failure are constant threats & diagnosis is

made on clinical grounds.

Pathogenesis

Environmental irritants mainly cigarette smoking &

other air pollutants, induce:-

1) Hypertrophy of mucous glands in the trachea & main-

stem bronchi and lead to a marked increase in mucin-

secreting goblet cells in the surface epithelium of smaller

bronchi and bronchioles lead to hypersecretion of mucus

2) Inflammation with infiltration of CD8+ T cells,

macrophages, and neutrophils.

The morphologic basis of airflow obstruction in

chronic bronchitis is more peripheral and results from

1) "Small airway disease," induced by goblet cell

metaplasia with mucus plugging of the bronchiolar

lumen, inflammation, and bronchiolar wall fibrosis.

2) Coexistent emphysema: chronic bronchitis with

significant airflow obstruction is almost always

complicated by emphysema.

Morphology

Grossly, the mucosal lining of the larger airways is

usually hyperemic and swollen due to edema. It is often

covered by a layer of mucinous or mucopurulent

Unit 12: Lung (Diseases of respiratory system)

071

secretions. The smaller bronchi and bronchioles may also

be filled with similar secretions.

Histologically,

(1) In the trachea and larger bronchi is enlargement of

the mucus-secreting glands. (2) Mixed inflammatory

cells, largely mononuclear but sometimes admixed with

neutrophils in the bronchial mucosa.

Chronic bronchiolitis (small airway disease),

characterized by goblet cell metaplasia, mucus plugging,

inflammation, and fibrosis, is also present. In the most

severe cases, there may be complete obliteration of the

lumen due to fibrosis (bronchiolitis obliterans). It is the

peribronchiolar fibrosis and luminal narrowing that results

in airway obstruction.

Asthma

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory airways disorder that

causes recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness,

chest tightness, and cough, particularly at night and/or

early in the morning.

This clinical picture is caused by repeated immediate

hypersensitivity and late-phase reactions in the lung that

give rise

1) intermittent and reversible airway obstruction,

2) chronic bronchial inflammation with eosinophils,

3) Bronchial smooth muscle cell hypertrophy and

hyperreactivity. It is thought that inflammation causes

an increase in (bronchospasm) to a variety of stimuli.

About 70% of cases are said to be "extrinsic" or "atopic"

and are due to IgE and T

H

2-mediated immune responses

to environmental Ags. While in 30% asthma is said to be

"intrinsic" or "non-atopic" & is triggered by non-immune

stimuli such as aspirin; pulmonary infections,(viruses);

cold; psychological stress; exercise; and inhaled irritants.

Pathogenesis

The major etiologic factors of asthma are genetic

predisposition to type I hypersensitivity ("atopy"), acute

and chronic airway inflammation, and bronchial hyper-

responsiveness to a variety of stimuli.

1) Atopic asthma is associated with an excessive T

H

2

reaction against environmental antigens. Cytokines”IL-4”

produced by T

H

2 cells account for most of the features of

asthma- stimulates IgE production, IL-5 activates

eosinophils, and IL-13 stimulates mucus production. All

of these cytokines are produced by T

H

2 cells.

In addition, epithelial cells are activated to produce

chemokines that promote recruitment of more T

H

2 cells

and eosinophils & other leukocytes.

2) "airway remodeling." These changes include

hypertrophy of bronchial smooth muscle and deposition

of subepithelial collagen, it may occur over several years

before initiation of symptoms& its etiologic basis may be

an inherited predisposition associated with accelerated

proliferation of bronchial smooth muscle cells and

fibroblasts. The gene that implicated called ADAM33, .

Mast cells, are also thought to contribute to airway

remodeling by secreting growth factors that stimulate

smooth muscle proliferation.

Atopic Asthma

This most common type of asthma usually begins in

childhood. A positive family history of atopy is common,

and asthmatic attacks are often preceded by allergic

rhinitis, urticaria, or eczema. The disease is triggered by

environmental antigens, such as dusts, pollen, animal

dander, and foods…etc.

In the airways there is an initial sensitization to the

inhaled antigens, which stimulates induction of T

H

2-type

cells and release of interleukins IL-4 and IL-5. This leads

to synthesis of IgE that binds to mucosal mast cells.

Exposure of IgE-coated mast cells to the same antigen

causes cross-linking of IgE and the release of chemical

mediators. Mast cells on the respiratory mucosal surface

are initially activated; the resultant mediator release opens

mucosal intercellular junctions, allowing penetration of

the antigen to more numerous mucosal mast cells. In

addition, direct stimulation of subepithelial vagal

(parasympathetic) receptors provokes reflex

bronchoconstriction through both central and local

reflexes. This occurs within minutes after stimulation and

is therefore called the acute, or immediate, response,

which consists of bronchoconstriction, edema (due to

increased vascular permeability), and mucus secretion. A

variety of inflammatory mediators have been implicated

in the acute-phase response, includes: Leukotrienes C

4

,

D

4

, and E

4

, Acetylcholine, histamine. Prostaglandin

D

2

,.Platelet-activating factor.

Mast cells also release additional cytokines that cause the

influx of other leukocytes, including neutrophils &

mononuclear cells, & eosinophils. These inflammatory

cells set the stage for the late-phase reaction, which starts

4 to 8 hours later & may persist for 12 to 24 hours or more

Non- Atopic Asthma

Viral infections of the respiratory tract (most common)

and inhaled air pollutants such as sulfur dioxide, ozone,

and nitrogen dioxide. These agents increase airway hyper-

reactivity in both normal and asthmatic subjects. In the

Unit 12: Lung (Diseases of respiratory system)

071

latter, however, the bronchial response, manifested as

spasm, is much more severe and sustained. A positive

family history is uncommon, serum IgE levels are normal,

and there are no associated allergies.

Drug-Induced Asthma

Several pharmacologic agents provoke asthma, aspirin

being the most striking example. Individuals with aspirin

sensitivity present with recurrent rhinitis and nasal polyps,

urticaria, and bronchospasm. The precise mechanism

remains unknown.

Occupational Asthma

This form of asthma is stimulated by fumes (epoxy resins,

plastics), organic and chemical dusts (wood, cotton,

platinum), gases (toluene), and other chemicals. Asthma

attacks usually develop after repeated exposure to the

inciting antigen(s).

Morphology

In fatal cases, grossly, the lungs are overdistended because

of overinflation, and there may be small areas of

atelectasis. The most striking macroscopic finding is

occlusion of bronchi and bronchioles by thick, tenacious

mucus plugs. Histologically, the mucus plugs contain

whorls of shed epithelium (Curschmann spirals).

Numerous eosinophils and Charcot-Leyden crystals

(collections of crystalloids made up of eosinophil proteins)

are also present. The other characteristic findings of

asthma, collectively called "airway remodeling"

Thickening of the basement membrane of the bronchial

epithelium.Edema and an inflammatory infiltrate in the

bronchial walls, with a prominence of eosinophils and

mast cells.An increase in the size of the submucosal

glands.Hypertrophy of the bronchial muscle walls.

Bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis is the permanent dilation of bronchi and

bronchioles caused by destruction of the muscle and

elastic supporting tissue, resulting from or associated with

chronic necrotizing infections. It is not a primary disease

but rather is secondary to persisting infection or

obstruction caused by a variety of conditions.

Predisposing Factors

Bronchial obstruction. by tumors, foreign bodies, and

occasionally impaction of mucus. Under these conditions,

the bronchiectasis is localized to the obstructed lung

segment. Bronchiectasis can also complicate atopic

asthma and chronic bronchitis.

Congenital or hereditary conditions. Like

In cystic fibrosis, widespread severe bronchiectasis

results from obstruction and infection caused by the

secretion of abnormally viscid mucus.

In immunodeficiency states, particularly

immunoglobulin deficiencies, bronchiectasis is likely to

develop because of an increased susceptibility to repeated

bacterial infections.

Kartagener syndrome, an autosomal recessive disorder,

is frequently associated with bronchiectasis and with

sterility in males. Structural abnormalities of the cilia

impair mucociliary clearance in the airways, leading to

persistent infections, and reduce the mobility of

spermatozoa.

Suppurative, pneumonia, due to Staphylococcus aureus

or Klebsiella spp., may predispose to bronchiectasis.

Pathogenesis

Two processes in the pathogenesis of bronchiectasis:

Obstruction and chronic persistent infection. Either of

these two processes may come first. Normal clearance

mechanisms are hampered by obstruction (by a

bronchogenic carcinoma or a foreign body), so secondary

infection soon follows; conversely, chronic infection in

time causes damage to bronchial walls, leading to

weakening and dilation.

Morphology

Bronchiectatic involvement of the lungs usually affects

the lower lobes bilaterally, When tumors or aspiration of

foreign bodies lead to bronchiectasis, involvement may be

sharply localized to a single segment of the lungs.

Usually, the most severe involvement is found in the more

distal bronchi and bronchioles. The airways may be

dilated to as much as four times their usual diameter.

The histologic findings vary with the activity and

chronicity of the disease. In the full-blown active case, an

intense acute and chronic inflammatory exudate

within the walls of the bronchi and bronchioles and the

desquamation of lining epithelium cause extensive areas

of ulceration.

In the usual case, a mixed flora can be cultured from the

involved bronchi, including staphylococci, streptococci,

pneumococci, .When healing occurs, the lining epithelium

may regenerate completely; however, usually so much injury

has occurred that abnormal dilation and scarring persist.

Fibrosis of the bronchial and bronchiolar walls and

peribronchiolar fibrosis develop in more chronic cases.

In some instances, the necrosis destroys the bronchial or

bronchiolar walls and forms a lung abscess

Unit 12: Lung (Diseases of respiratory system)

071

Pulmonary infections

Pneumonia defined as any infection in the lung. It may be

acute or chronic disease with a more protracted course.

Causes

Bacterial, viral, fungal, chemical…. .

Acute bacterial pneumonias can present as

bronchopneumonia or lobar pneumonia.

1) Bronchopneumonia implies a patchy distribution of

inflammation that generally involves more than one lobe,

results from an initial infection of the bronchi and

bronchioles with extension into the adjacent alveoli.

2) Lobar pneumonia the contiguous airspaces of part or all of

a lobe are homogeneously filled with an exudate that can

be visualized on radiographs as a lobar or segmental

consolidation. Streptococcus pneumoniae is responsible

for more than 90% of lobar pneumonias. Other

classification of pneumonias

1-base on specific etiologic agent

2-clinical setting if no pathogen can be isolated.

Community-Acquired Acute Pneumonias

Most community-acquired acute pneumonias are bacterial

in origin. Usually the infection follows a viral upper

respiratory tract infection. The onset is usually abrupt, with

high fever, chills, pleuritic chest pain, & a productive

mucopurulent cough; S. pneumoniae is the most common

cause of community-acquired acute pneumonia.

I-Streptococcus pneumoniae

Pneumococcal infections occur with increased frequency

in three groups of individuals:

1) Those with underlying chronic diseases such as CHF,

COPD, or diabetes.

2) Those with either congenital or acquired immunoglobulin

defects (e.g., the acquired immune deficiency syndrome).

3) Those with decreased or absent splenic function (e.g.,

sickle cell disease or after splenectomy). because the

spleen contains the largest collection of phagocytes & thus

responsible for removing pneumococci from the blood.

Morphology

With pneumococcal lung infection, it could be lobar or

bronchopneumonia, the latter is more prevalent at the

extremes of age. Regardless of the distribution of the

pneumonia, because pneumococcal lung infections usually

originate by aspiration of pharyngeal flora (20% of adults

harbor S. pneumoniae in their throats), the lower lobes or

the right middle lobe are most frequently involved.

In the era before antibiotics, pneumococcal pneumonia

involved entire or almost entire lobes and evolved through

four stages: congestion, red hepatization, gray

hepatization, and resolution. Early antibiotic therapy

alters this typical progression.

1) Congestion stage: in which the affected lobe heavy &

red. Histologically, vascular congestion can be seen, with

proteinaceous fluid, scattered neutrophils, and many

bacteria in the alveoli.

2) Red hepatization stage in which the lung lobe has a

liver-like consistency; the alveolar spaces are packed with

neutrophils, red cells, and fibrin.

3) Gray hepatization in this stage the lung is dry, gray, and

firm, because RBC are lysed, while the fibrinosuppurative

exudate persists within the alveoli.

4) Stage of Resolution follows in uncomplicated cases, as

exudates within the alveoli are enzymatically digested to

produce granular, semifluid debris that is resorbed,

ingested by macrophages, coughed up, or organized by

fibroblasts growing into it.

The pleural involvment (pleuritis) may resolve or

undergo organization, leaving fibrous thickening or

permanent adhesions

In the bronchopneumonic pattern, foci of inflammatory

consolidation are distributed in patches throughout one or

more lobes, most frequently bilateral and basal. Well-

developed lesions up to 3 - 4 cm in diameter are slightly

elevated and are gray-red to yellow. The lung tissues

surrounding areas of consolidation is usually hyperemic

and edematous& Pleural involvement is less common

than in lobar pneumonia.

Histologically, the lesion consists of focal suppurative

exudate that fills the bronchi, bronchioles, and adjacent

alveolar spaces.

Complications:

1) Abscess due to tissue destruction and necrosis .

2) Empyema when pus accumulate in the pleural cavity.

3) Organization of the intra-alveolar exudate may convert

areas of the lung into solid fibrous tissue;

4) bacteremic dissemination may lead to meningitis,

arthritis, or infective endocarditis. Complications are

much more likely with serotype 3 pneumococci

Diagnosis

1) Gram-stained sputum is an important step in the diagnosis

of acute pneumonia. Looking for neutrophils containing

the typical gram-positive diplococci is good evidence of

pneumococcal pneumonia, but as S. pneumoniae is an

endogenous flora and therefore false-positive results may

be obtained by this method.

Unit 12: Lung (Diseases of respiratory system)

071

2) Blood cultures is more specific. During early phases of

illness, blood cultures may be positive in 20% to 30% of

persons with pneumonia.

II-Haemophilus influenzae

It can cause a life-threatening form of pneumonia in

children, often following a respiratory viral infection.

Adults at risk are those with chronic pulmonary diseases

such as chronic bronchitis, cystic fibrosis, and

bronchiectasis.

.Encapsulated H. influenzae type b was an important

cause of epiglottitis and suppurative meningitis in

children, & vaccination against this organism in infancy

has significantly reduced the risk.

III-Staphylococcus aureus

It is an important cause of secondary bacterial pneumonia

in children and healthy adults after viral respiratory

illnesses (e.g., measles in children and influenza in both

children & adults).Staphylococcal pneumonia is associated

with a high incidence of complications, such as lung

abscess and empyema.Staphylococcal pneumonia occurring

in association with right-sided staphylococcal endocarditis

is a serious complication of intravenous drug abuse. It is

also an important cause of nosocomial pneumonia

IV-Klebsiella pneumoniae

K. pneumoniae is the most frequent cause of gram-

negative bacterial pneumonia.It frequently Affect

debilitated and malnourished persons, particularly chronic

alcoholics.Thick and gelatinous sputum is characteristic,

because the organism produces an abundant viscid

capsular polysaccharide.

Hospital-Acquired Pneumonias (Nasocomial

pneumonia)

Nosocomial or hospital-acquired, pneumonias are defined as

pulmonary infections acquired in the course of a hospital

stay. Nosocomial infections are common in hospitalized

persons with severe underlying disease, immune

suppression, or prolonged antibiotic therapy. Those on

mechanical ventilation are at high-risk. Gram-negative rods

(Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas spp.) & S. aureus are

the most common isolates; while, S. pneumoniae is not a

major pathogen in nosocomial infections

Aspiration Pneumonia

Aspiration pneumonia occurs in markedly debilitated

patients or those who aspirate gastric contents either while

unconscious (e.g., after a stroke) or during repeated

vomiting. These individuals have abnormal gag and

swallowing reflexes that facilitate aspiration. The

resultant pneumonia is partly chemical, resulting from the

extremely irritating effects of the gastric acid, and partly

bacterial recent studies implicate aerobes more commonly

than anaerobes. This type of pneumonia is often

necrotizing, with a fulminant clinical course, and is a

frequent cause of death in persons predisposed to

aspiration & abscess formation is a common complication

Lung Abscess

Lung abscess refers to a localized area of suppurative

necrosis within the pulmonary parenchyma, resulting in

the formation of large cavity. The term necrotizing

pneumonia has been used for a similar process resulting in

multiple small cavitations; necrotizing pneumonia often

coexists or evolves into lung abscess, The causative

organism may be introduced into the lung by any of the

following mechanisms

1) Aspiration of infective material from carious teeth or

infected sinuses or tonsils, particularly likely during oral

surgery, anesthesia, coma, or alcoholic intoxication and in

debilitated patients with depressed cough reflexes.

2) Aspiration of gastric contents, usually accompanied by

infectious organisms from the oropharynx.

3) As a complication of necrotizing bacterial pneumonias,

particularly those caused by S. aureus, Streptococcus

pyogenes, K. pneumoniae, Pseudomonas spp., and, rarely,

type 3 pneumococci. Mycotic infections and

bronchiectasis may also lead to lung abscesses.

4) Bronchial obstruction, particularly with bronchogenic

carcinoma obstructing a bronchus or bronchiole. Impaired

drainage, distal atelectasis, and aspiration of blood and

tumor fragments all contribute to the development of

abscesses. An abscess may also form within an excavated

necrotic portion of a tumor.

5) Septic embolism, from septic thrombophlebitis or from

infective endocarditis of the right side of the heart.In

addition, lung abscesses may result from hematogenous

spread of bacteria in disseminated pyogenic infection e.g.

staphylococcal bacteremia which results in multiple lung

abscesses.

Anaerobic bacteria are present in almost all lung

abscesses e.g. Bacteroides& microaerophilic streptococci.

Morphology

Abscesses vary in diameter from a few millimeters to large

cavities of 5 to 6 cm. The localization and number of

Unit 12: Lung (Diseases of respiratory system)

077

abscesses depend on their mode of development.

Pulmonary abscesses resulting from aspiration of infective

material are much more common on the right side (more

vertical airways) than on the left, and most are single. On

the right side, they tend to occur in the posterior segment of

the upper lobe and in the apical segments of the lower lobe,

because these locations reflect the probable course of

aspirated material when the patient is recumbent.

Abscesses that develop in the course of pneumonia or

bronchiectasis are commonly multiple, basal, and

diffusely scattered.

abscesses arising from hematogenous seeding or Septic

emboli are commonly multiple and may affect any region

of the lungs.

As the focus of suppuration enlarges, it almost inevitably

ruptures into airways. Thus, the contained exudate may be

partially drained, producing an air-fluid level on

radiographic examination. Occasionally, abscesses

rupture into the pleural cavity and produce bronchopleural

fistulas, the consequence of which is pneumothorax or

empyema. Other complications arise from embolization

of septic material to the brain, giving rise to meningitis or

brain abscess.

Histologically there is suppuration surrounded by variable

amounts of fibrous scarring and mononuclear infiltration

(lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages), depending on

the chronicity of the lesion.

Lung tumors

Primary lung cancer is a common disease. Bronchial

epithelium is the site of origin of 95% of primary lung

tumors (carcinomas); the remaining 5% includes

bronchial carcinoids, mesenchymal malignancies (e.g.,

fibrosarcomas, leiomyomas), lymphomas, and a few

benign lesions.

The most common benign lesions are Hamartomas:-

Spherical, small (3-4 cm), discrete that often show up as

"coin" lesions on chest radiographs. They consist mainly

of mature cartilage but are often admixed with fat, fibrous

tissue, and blood vessels in varying proportions.

Carcinoma

Lung cancer is the number one cause of cancer-related

deaths in industrialized countries. In either sex. These

statistics are related to the causal relationship of cigarette

smoking and lung cancer.

The peak incidence of lung cancer occurs in persons in

their 50s and 60s. The 5-year survival rate for all stages of

lung cancer combined is about 15%; even those with

disease localized to the lung have a 5-year survival of

approximately 45%.

Histologic types:-

The four major histologic types of carcinomas of the lung

are squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, small-cell

carcinoma, and large-cell carcinoma. In some cases there

is a combination of histologic patterns (e.g., combined

small-cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma).

Adenocarcinoma has replaced squamous cell carcinoma

as the most common primary lung tumor in recent years.

For therapeutic purposes, carcinomas of the lung are

classified into two broad groups:

1-small-cell lung cancer (SCLC)

2-non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) which includes

squamous cell, adenocarcinomas, and large-cell

carcinomas. The reason is that all SCLCs have

metastasized by the time of diagnosis and are not curable

by surgery. Therefore, they are best treated by

chemotherapy, with or without radiation. In contrast,

NSCLCs usually respond poorly to chemotherapy and are

better treated by surgery, there are also genetic differences

between SCLCs and NSCLCs. For example, SCLCs are

characterized by a high frequency of RB gene mutations,

while activating KRAS and EGFR oncogene mutations are

restricted to adenocarcinomas within the NSCLC group

and are rare in SCLCs.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Carcinomas of the lung arise by accumulation of genetic

abnormalities that result in transformation of benign

bronchial epithelium into neoplastic tissue. The sequence

of molecular changes start by inactivation of the tumor

suppressor genes located on chromosome 3p as an early

event, whereas p53 mutations or activation of the KRAS

oncogene occurs relatively late. Loss of chromosome 3p

material, can be found even in benign bronchial

epithelium of individuals with lung cancer, as well as in

the respiratory epithelium of smokers without lung

cancers, suggesting that large areas of the respiratory

mucosa are mutagenized after exposure to carcinogens.

On this fertile soil, those cells that accumulate additional

mutations ultimately develop into cancer.

Statistically, about 90% of lung cancers occur in active

smokers or those who stopped recently. The increased risk

becomes 60 times greater among habitual heavy smokers

(two packs a day for 20 years) compared with nonsmokers.

Women have a higher susceptibility to carcinogens in

tobacco than men. Cessation of smoking decreases the risk

Unit 12: Lung (Diseases of respiratory system)

071

of developing lung cancer over time but it may never

return to baseline levels. Passive smoking (proximity to

cigarette smokers) increases the risk of developing lung

cancer to approximately twice that of nonsmokers.

The smoking of pipes and cigars also increases the risk,

but only modestly.

It is well known that not all persons exposed to tobacco

smoke develop cancer. It is very likely that the mutagenic

effect of carcinogens is conditioned by hereditary (genetic)

factors. Recall that many chemicals (procarcinogens)

require metabolic activation via the P-450 monooxygenase

enzyme system for conversion into ultimate carcinogens.

There is evidence that persons with specific genetic

polymorphisms involving the P-450 genes have an

increased capacity to metabolize procarcinogens derived

from cigarette smoke and, conceivably, incur the greatest

risk of developing lung cancer.

Morphology

Carcinomas of the lung begin as small mucosal lesions

that are usually firm and gray-white. They may form

intraluminal masses, invade the bronchial mucosa, or

form large bulky masses pushing into adjacent lung

parenchyma. Some large masses undergo cavitation

caused by central necrosis or develop focal areas of

hemorrhage. Finally, these tumors may extend to the

pleura, invade the pleural cavity and chest wall, & spread

to adjacent intrathoracic structures. More distant spread

can occur via the lymphatics or the hematogenous route.

Squamous cell carcinomas

are more common in men

than in women and are closely correlated with a smoking

history; they tend to arise centrally in major bronchi and

eventually spread to local hilar nodes, but they disseminate

outside the thorax later than other histologic types. Large

lesions may undergo central necrosis, giving rise to

cavitation. Squamous cell carcinomas are often preceded

for years by squamous metaplasia or dysplasia in the

bronchial epithelium, which then transforms to carcinoma

in situ, a phase that may last for several years. By this time,

atypical cells may be identified in cytologic smears of

sputum or in bronchial lavage fluids or brushings, although

the lesion is asymptomatic and undetectable on

radiographs. Eventually, the small neoplasm reaches a

symptomatic stage, when a well-defined tumor mass begins

to obstruct the lumen of a major bronchus, often producing

distal atelectasis and infection. Simultaneously, the lesion

invades surrounding pulmonary substance. Histologically,

these tumors range from well-differentiated squamous cell

neoplasms showing keratin pearls and intercellular bridges

to poorly differentiated neoplasms having only minimal

residual squamous cell features.

Adenocarcinomas

are usually more peripherally

located, many arising in relation to peripheral lung scars

(“scar carcinomas”). Adenocarcinomas are the most

common type of lung cancer in women and nonsmokers. It

grow slowly and form smaller masses than do the other

subtypes, but they tend to metastasize widely at an early

stage

Histologically, they assume a variety of forms, including

acinar (gland forming), papillary

, and

solid types

. The

putative precursor of peripheral adenocarcinomas has

been described as atypical adenomatous hyperplasia

(AAH). Microscopically, AAH is recognized as a well-

demarcated focus of epithelial proliferation composed of

cuboidal to low-columnar cells with various degrees of

cytologic atypia (nuclear hyperchromasia, pleomorphism,

prominent nucleoli). Genetic analyses of AAH show

many of the molecular aberrations associated with

adenocarcinomas (e.g., KRAS mutations).

Bronchioloalveolar carcinomas (BACs)

They

involve peripheral parts of the lung, either as a single

nodule or, more often, as multiple diffuse nodules that

may coalesce to produce pneumonia-like consolidation.

The key feature of BACs is their growth along

preexisting structures and preservation of alveolar

architecture. The two subtypes of BACs are mucinous

and nonmucinous, with the former comprising tall,

columnar cells with prominent cytoplasmic and intra-

alveolar mucin. it is proposed that some invasive

adenocarcinomas of the lung may arise through an

atypical adenomatous hyperplasia-bronchioloalveolar

carcinoma-invasive adenocarcinoma sequence.

Large-cell carcinomas

are undifferentiated malignant

epithelial tumors that lack the cytologic features of small-

cell carcinoma and glandular or squamous differentiation.

The cells typically have large nuclei, prominent nucleoli,

and a moderate amount of cytoplasm. Large-cell

carcinomas probably represent squamous cell or

adenocarcinomas that are so undifferentiated that they can

no longer be recognized by light microscopy.

Ultrastructurally, however, minimal glandular or

squamous differentiation is common

Small-cell lung carcinomas

generally appear as pale

gray, centrally located masses with extension into the

lung parenchyma and early involvement of the hilar and

mediastinal nodes. These cancers are composed of tumor

Unit 12: Lung (Diseases of respiratory system)

071

cells with a round to fusiform shape, scant cytoplasm, and

finely granular chromatin. Mitotic figures are frequently

seen, " the neoplastic cells are usually twice the size of

resting lymphocytes. Necrosis is invariably present and

may be extensive. The tumor cells are markedly fragile

and often show fragmentation and "crush artifact" in

small biopsy specimens. Another feature of small-cell

carcinomas, best appreciated in cytologic specimens, is

nuclear molding resulting from close apposition of tumor

cells that have scant cytoplasm. These tumors are derived

from neuroendocrine cells of the lung, and hence they

express a variety of neuroendocrine markers in addition

to a host of polypeptide hormones that may result in

paraneoplastic syndromes.

Clinical course

Carcinomas of the lung are silent, insidious lesions In

some instances, chronic cough and expectoration call

attention to still localized, resectable disease. By the time

hoarseness, chest pain, superior vena caval syndrome,

pericardial or pleural effusion, or persistent segmental

atelectasis or pneumonitis makes its appearance, the

prognosis is grim. Too often, the tumor presents with

symptoms emanating from metastatic spread to the brain

(mental or neurologic changes), liver (hepatomegaly), or

bones (pain). Although the adrenals may be nearly

obliterated by metastatic disease, adrenal insufficiency

(Addison disease) is uncommon because islands of

cortical cells sufficient to maintain adrenal function

usually persist. Overall, NSCLCs have a better prognosis

than SCLCs. When NSCLCs (squamous cell carcinomas

or adenocarcinomas) are detected before metastasis or

local spread, cure is possible by lobectomy or

pneumonectomy. SCLCs, on the other hand, have

invariably spread by the time they are first detected, even

if the primary tumor appears small and localized. Thus,

surgical resection is not a viable treatment. They are very

sensitive to chemotherapy but invariably recur. Median

survival even with treatment is 1 year. It is variously

estimated that 3% to 10% of all patients with lung cancer

develop clinically overt paraneoplastic syndromes. These

include

1) Hypercalcemia caused by secretion of a parathyroid

hormone-related peptide (osteolytic lesions may also

cause hypercalcemia, but this would not be a

paraneoplastic syndrome;

2) Cushing syndrome (from increased production of

adrenocorticotropic hormone);

3) syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone

4) Neuromuscular syndromes, including a myasthenic

syndrome, peripheral neuropathy, and polymyositis;

5) Clubbing of the fingers and hypertrophic pulmonary

osteoarthropathy; and

6) Hematologic manifestations, including migratory

thrombophlebitis, nonbacterial endocarditis, and

disseminated intravascular coagulation. Secretion of

calcitonin and other ectopic hormones has also been

documented. Hypercalcemia is most often encountered

with squamous cell neoplasms, the hematologic

syndromes with adenocarcinomas. The remaining

syndromes are much more common with small-cell

neoplasms, but exceptions abound.

Carcinoids

Bronchial carcinoids are thought to arise from the

Kulchitsky cells (neuroendocrine cells) that line the

bronchial mucosa and resemble intestinal carcinoids. The

neoplastic cells contain dense-core neurosecretory

granules in their cytoplasm and, may secrete hormonally

active polypeptides. They occasionally occur as part of

the multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome. Bronchial

carcinoids appear at an early age (mean 40 years) and

represent about 5% of all pulmonary neoplasms. In happy

contrast to their more ominous neuroendocrine

counterpart, small-cell carcinomas, carcinoids are often

resectable and curable.

Morphology

Most bronchial carcinoids originate in main-stem bronchi

and grow in one of two patterns: (1) an obstructing

polypoid, spherical, intraluminal mass; or (2) a mucosal

plaque penetrating the bronchial wall.About 5% -15% of

these tumors have metastasized to the hilar nodes at

presentation, distant metastasis is rare.

Histologically, these neoplasms are composed of nests of

uniform cells that have regular round nuclei with "salt-

and-pepper" chromatin, absent or rare mitoses, and little

pleomorphism.

Atypical carcinoid tumors display a higher mitotic rate,

increased cytologic variability, and focal necrosis. & have

a higher incidence of lymph node and distant metastasis

than "typical" carcinoids, and understandably persons

with atypical carcinoids fare worse in the long run with

p53 mutations in 20% to 40% of cases.