Unit 11: Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Systems

156

Haemopoiesis

Haemopoiesis is process of blood cell formation, starts

with a stem cell that can give rise to the separate cell

lineages. Haemopoiesis include:

Erythropoiesis (formation of red cells).

Myelopoiesis (formation of granulocytes and monocytes).

Thrombopoiesis (formation of platelets).

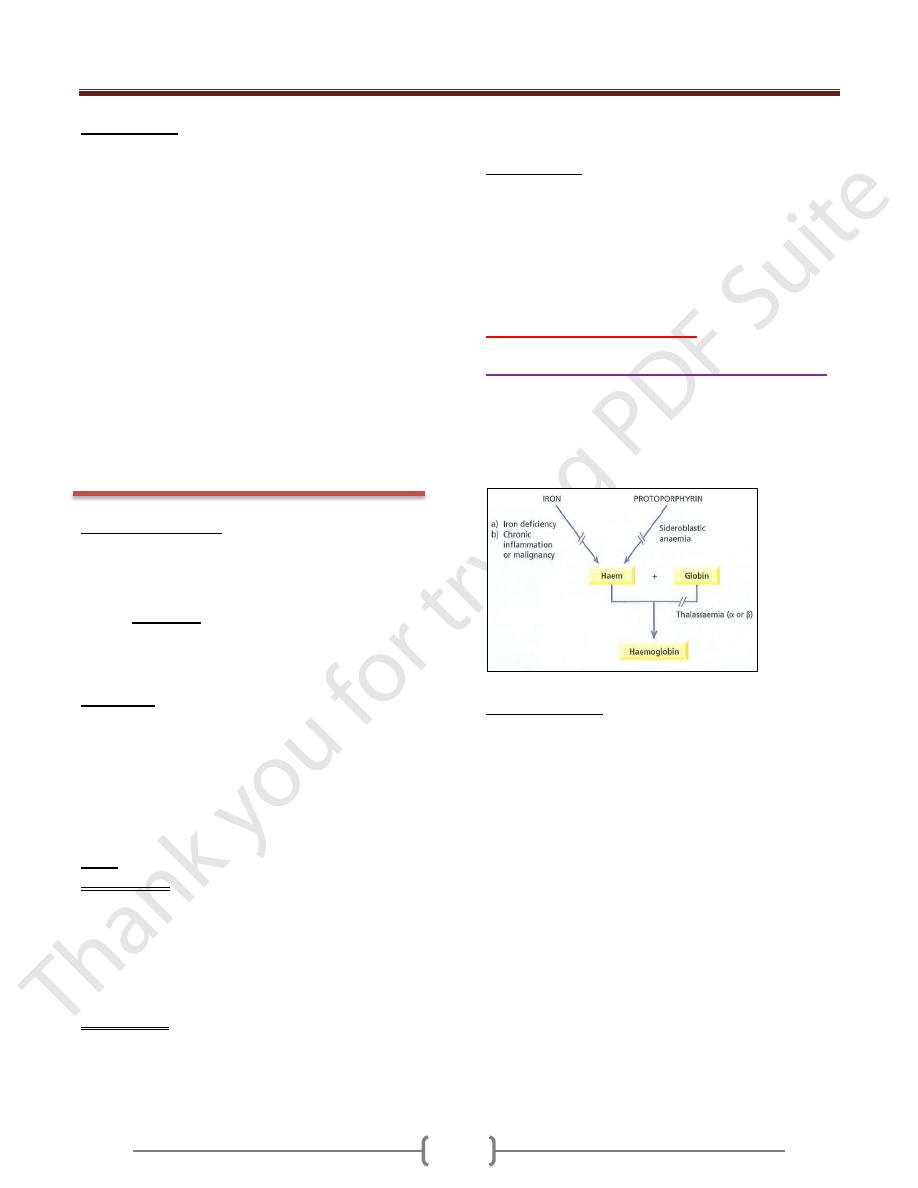

Haemoglobin (Hb) is iron containing metalloprotein

found in the red blood cells. The main function of

haemoglobin is to carry O

2

to the tissues and to return

carbon dioxide (CO

2

) from the tissues to the lungs, Hb

molecule consist of:

4 polypeptide chains.

4 haem group (each composed of Fe

2+

& portoporphyrin)

RED CELL DISORDERS

Anemia in general

Anemia defined as a reduction in the haemoglobin

concentration of the blood less than 13.5 g/dL in adult

males, less than 11.5 g/dL in adult females.

Anemia

caused by:

Blood loss (hemorrhage).

Increased red cell destruction (hemolysis).

Decreased red cell production.

Symptoms

Shortness of Breath.

Weakness.

Palpitation.

Headaches.

Heart failure (especially in elderly).

Angina pectoris (especially in elderly).

Visual disturbances (very severe anemia).

Signs

General Signs

Are associated with all type of anemia include:

o Pallor of mucous membranes.

o Tachycardia.

o Cardiomegaly and a systolic flow murmur (especially

in elderly).

o Retinal haemorrhages (in severe anemia)

Specific Signs

Are associated with particular types of anemia e.g.:

o Koilonychia (spoon nails) with iron deficiency.

o Jaundice with hemolytic or megaloblastic anemia.

o Leg ulcers with sickle cell and hemolytic anemia.

o Bone deformities with thalassaemia major.

Classification

The most useful classification is that based on red cell

volume (MCV) and divides the anemia into:

Microcytic (MCV <80fL).

Normocytic (MCV 80 - 95fL).

Macrocytic (MCV >95fL).

Hemolytic anemias

Microcytic anemia differential diagnosis:

1. Iron deficiency anemia.

2. Anemia of chronic disease (some cases).

3. Thalassaemia (major and minor)

4. Sideroblastic anemia (some cases)

Iron metabolism

Approximately 1 mg of iron is absorbed (in duodenum

and upper jejunum) and 1 mg lost (sweating, epidermal

shedding) each day.

Transferrin is the main iron carrier in plasma, transfer iron

from GIT cells to erythroblast (Hb forming cells) or store.

Iron stored in reticuloendothelial system (bone marrow,

liver and spleen) in 2 forms: ferritin and hemosiderin.

Serum iron measure iron bound to transferrin while total

iron binding capacity (T.I.B.C) measure transferrin not

bound to iron i.e. free transferrin.

Serum transferrin receptor (sTfR) is portion of the

transferrin receptor (found on surface of cells) that shed

into serum. The sTfR is regarded as a more stable marker

of iron store than ferritin in inflammatory state (since

ferritin is an acute phase reactant protein that increased in

inflammation).

Total amount of body iron is 2-6 g distributed in form of

Hb, myoglobin, ferritin, hemosiderin, transferrin bound

iron and enzymes cytochrome).

Unit 11: Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Systems

157

Iron deficiency Anemia

It is the most common cause of anemia worldwide. The

reticuloendothelial iron stores become completely

depleted before anemia occurs.

Causes of iron deficiency:

Chronic blood loss especially uterine or from the

gastrointestinal tract (most common cause).

Increased demands during infancy, adolescence,

pregnancy, lactation and in menstruating women.

Malabsorption or poor diet (rare) e.g. Gluten-

induced enteropathy.

Clinical features

General symptoms and signs of anemia

Specific symptoms and signs as:

1) Painless glossitis.

2) Angular stomatitis.

3) Koilonychia (spoon nails).

4) Dysphagia as a result of pharyngeal webs (Paterson

Kelly or Plummer-Vinson syndrome).

5) Pica (unusual dietary cravings e.g. earth, clay, ice).

6) Irritability, poor cognitive function and a decline in

psychomotor development (in children).

Laboratory findings:

Low Hb (Mild, moderate or severe anemia).

MCV < 80fL (Microcytic) & MCH (Hypochromic) <

27pg/L.

Blood film shows hypochromic microcytic cells with

target cells and pencil shaped poikilocytes.

Iron Studies used to confirm iron deficiency anemia,

include: Serum iron decreased; Total iron binding

capacity (TIBC) increased; Serum transferrin receptor

increased and Serum ferritin is very low.

Bone marrow iron (reticuloendothelial store) is absent

Treatment

Treat the underlying cause.

Iron replacement therapy (oral iron or parentral) 4 – 6

months to treat anemia and replenish iron store.

Anemia of chronic disorders

Common anemia occurs in patients with chronic

inflammatory and malignant diseases. The pathogenesis

of this anemia related to decreased release of iron from

macrophages (store) to plasma.

Laboratory findings:

Low Hb (mild and non-progressive anemia).

MCV and MCH Normal or slightly reduced (MCV

rarely <75 fL).

Blood film shows normochromic, normocytic or

mildly hypochromic microcytic.

Iron Studies include: serum iron decreased; TIBC

decreased; serum transferrin receptor normal and

serum ferritin is normal or increased.

Bone marrow storage (reticuloendothelial) iron is normal.

Treatment

Treat The underlying cause (does not respond to iron therapy).

Thalassaemia Trait

Group of genetic disorders that result in a reduced rate of

synthesis of globin chains (reduce Hb synthesis).

Laboratory findings:

Hb normal or low (absent or mild anemia).

MCV and MCH reduced (MCV ≤ 70 fL).

Red cell count is usually over 5.5 x 10

12

/L.

Blood film shows hypochromic microcytic red cells.

Iron Studies in thalassaemia minor are Normal.

Hb electrophoresis raised Hb A2.

Sideroblastic Anemia

It is a refractory anemia caused by defect in haem

synthesis (failure to use iron in Hb synthesis despite the

availability of high iron stores). Sideroblastic anemia

either congenital or acquired e.g. Lead poisoning.

Laboratory findings:

Blood film shows hypochromic microcytic red cells.

Iron Studies: Serum iron increased; TIBC normal; Serum

transferrin receptor normal; Serum ferritin increased.

Bone marrow iron is increased.

Presence of many pathological ring sideroblasts in

the bone marrow (diagnostic for sideroblastic anemia)

Macrocytic Anemia

In macrocytic anemia, the red cells are abnormally large

(mean cell volume MCV > 95 fL). Causes of

macrocytosis can be subdivided into 2 groups:

Megaloblastic: erythroblasts in the bone marrow show

delayed maturation of the nucleus relative to the cytoplasm

(asynchronous maturation) due defect in DNA synthesis.

Nonmegaloblastic erythroblasts in the bonemarrow are normal

Megaloblastic Anemia

Causes of megaloblastic anemia:

1) Vitamin B

l2

deficiency.

2) Folate deficiency.

Unit 11: Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Systems

158

3) Abnormalities of vitamin B

12

or folate metabolism

(nitrous oxide, antifolate drugs).

4) Defects of DNA synthesis (e.g. orotic aciduria, alcohol).

Causes of non megaloblastic macrocytosis:

1) Alcohol.

2) Liver disease (especially alcoholic).

3) Reticulocytosis (hemolysis or hemorrhage).

4) Aplastic anemia or red cell aplasia.

5) Hypothyroidism.

6) Myelodysplasia.

7) Myeloma and macroglobulinaemia.

8) Leucoerythroblastic anemia.

9) Myeloproliferative disease.

10) Pregnancy.

11) Newborn.

12) Congenital dyserythropoietic anemia (type II).

Vitamin B

12

(Cobalamin)

The vitamin B

12

is found in animal product only such as

liver, meat and dairy produce. Minimal adult daily

requirement is 1-2/µg. Body stores about 2-3 mg

(sufficient for 2-4 years).

Bl2 (in normal diet) is combined with the glycoprotein

intrinsic factor (IF) (which is synthesized by the gastric

parietal cells) in stomach. The IF-B

12

complex can then

bind to IF receptor in the distal ileum where B

l2

is

absorbed and IF destroyed.

Transcobalamin (TC) is vitamin B

l2

carrier in blood which

delivers B

l2

to bone marrow and other tissues.

Vitamin B

12

is a coenzyme for two biochemical reactions

in the body:

1) Methylation of homocysteine to methionine.

2) Conversion of methylmalonyl CoA to succinyl CoA.

Folate

Folate is found in liver, greens and yeast. Minimal adult

daily requirement is 100-150/µg. Body stores 10-12 mg

(sufficient for 4 months).

Dietary folates absorbed through duodenum and jejunum

(after conversion to methyltetrahydrofolate THF).

Folates are needed in a variety of biochemical reactions in

the body such:

1) Amino acid interconversions.

2) Synthesis of DNA purine precursors.

Both B

12

& folate deficiency cause defect in DNA synthesis

Causes of vitamin B

12

(Cobalamin) deficiency:

1) Nutritional (especially vegans)

2) Malabsorption:

Gastric causes (e.g., pernicious anemia, congenital lack or

abnormality of intrinsic factor, total or partial gastrectomy).

Intestinal causes (e.g. intestinal stagnant loop syndrome,

chronic tropical sprue, ileal resection and crohn's disease,

fish tapeworm).

Causes of folate deficiency:

1) Nutritional (especially old age, poverty, famine)

2) Malabsorption (tropical sprue, gluten induced enteropathy,

extensive jejunal resection or crohn's disease).

3) Excess utilization (pregnancy, lactation, hemolytic anaemias,

myelofibrosis, malignant disease, inflammatory diseases).

4) Excess urinary folate loss (active liver disease, congestive

heart failure)

5) Drugs (anticonvulsants, sulfasalazine).

6) Alcoholism.

Clinical features of megaloblastic anemia:

1) Symptoms of gradual, progressive anemia but sometimes

patients are asymptomatic (detected through the finding of

a raised MCV on a routine blood count).

2) Symptoms associated with vitamin B

l2

or Folic acid deficiency:

Peripheral neuropathy (sub-acute combined degeneration

of the cord) in severe B

12

deficiency only.

Gastrointestinal symptoms (due to vitamin B

l2

and folic

acid deficiency):

Anorexia and weight loss.

Diarrhea or constipation.

Glossitis (red, sore, smooth tongue)&angular cheilosis

Jaundice (due to destruction of red cell precursors in the

bone marrow).

Bruising (due to thrombocytopenia) and reversible

melanin skin hyperpigmentation.

Infections due to low WBC count (e.g. respiratory or

urinary tracts).

General tissue effects of B

12

& folate deficiencies:

1) Epithelial surfaces cells show macrocytosis, with

increased numbers of multinucleate and dying cells.

2) Infertility is common in (both men and women) and

recurrent fetal loss.

3) Folate or B12 deficiency in the mother predisposes to

neural tube defect in the fetus.

4) Cardiovascular disease (e.g. ischemic heart disease,

cerebrovascular disease or pulmonary embolus).

5) Prophylactic folic acid in pregnancy has been found to

reduce the subsequent incidence of acute lymphoblastic

leukemia in childhood.

Unit 11: Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Systems

159

Laboratory findings

A. Diagnosis megaloblastic anemia

1) Complete blood pictures:

Low Hb.

MCV > 95 fL (macrocytic).

Low WBC count (leucopenia)

Low platelet counts (thrombocytopenia).

Low reticulocyte count.

2) Blood film:

Macrocytic red cells (typically oval in shape).

Hyper segmented neutrophils nuclei (with 6 or more

lobes).

3) Bone marrow aspirate:

Hypercellular bone marrow.

Increased erythroid /myeloid ratio.

Erythroid cell precursors are large (megaloblastic) and

show failure of nuclear maturation but normal cytoplas

hemoglobinization (asynchronous maturation).

Myeloid cell changes (giant metamyelocytes).

Megakariocytes are decreased and show abnormal

morphology

4) Biochemistry:

elevation of serum unconjugated bilirubin.

elevation of lactate dehrogenase (LDH).

B. Establishing a type of deficiency (vitamin B

12

and/or

folic acid)

1) Low serum B

12

(in megaloblastic anemia or neuropathy

caused by B

12

deficiency).

2) Low serum and red cell folate (in megaloblastic anemia

caused by folate deficiency).

3) Homocysteine and methylmalonic acid level increased in

B

12

deficiency while homocysteine level increased in

folate deficiency.

C. Establishing a cause of deficiency.

Treatment

In vitamin B

12

deficiency, Hydroxocobalamin is given

(intramuscular).

In folate deficiency, folic acid is given (oral). If large

doses of folic acid are given in B

l2

deficiency they cause a

hematological response but may aggravate the

neuropathy. They should therefore not be given alone

unless B

12

deficiency has been excluded.

Prophylactic Therapy

Prophylactic Vitamin B

12

therapy is given to patients who

have: 1) Total gastrectomy. 2) Ileal resection.

Prophylactic folic acid is given in:

1) Pregnancy (to prevent a neural tube defect occurrence)

2) Chronic dialysis.

3) Hemolytic anemias.

4) Chronic myelofibrosis.

Pernicious anemia

A severe lack of IF due to gastric atrophy (autoimmune

destruction of gastric parietal cells). The ratio of incidence

in men and women is approximately 1:1.6 and the peak

age of onset is 60 years. Pernicious anemia associations

(occur more commonly with):

1) Female. 2) Blue eyes.

3) Premature greying. 4) Northern Europeans

5) Familial. 6) Blood group A.

7) Other autoimmune diseases (e.g. vitiligo, thyroid

diseases, Addison disease).

8) An association with HLA - B8, - B12 and - BW15.

Diagnosis

Pernicious anemia usually suspected from the clinical

picture and the findings of megaloblastic anemia due to

B

12

deficiency, confirmed by:

1) Presence of circulating gastric auto antibodies (important):

Parietal cell antibody.

IF antibody (blocking and binding) found.

2) Gastric biopsy usually shows atrophy of all layers.

3) A lack of IF has been demonstrated by cobalamin

absorption studies (Schilling technique): the urinary

secretion (Schilling) test was carried out with an oral trace

dose of radioactive cyanocobalamin with or without oral

IF and a (flushing) intramuscular dose of

hydroxocobalamin or cyanocobalamin so that any labeled

cobalamin absorbed would appear in a 24 hour urine (this

test is no longer available in most countries).

4) Low or absent Hcl or pepsin (now rarely performed).

Other Hemolytic anemias

These are anemias which result from an increase in RBC

destruction (mean lifespan of the red cell reduced).

Classifications:

1) Location of hemolysis (intravascular or extravascular).

2) Location of defect causing the hemolysis (intrinsic or

extrinsic).

3) Mode of onset (inherited or acquired).

Extravascular hemolysis: it's a normal process, RBCs

phagocytized by reticuloendothelial system cells (in

marrow, liver and spleen) after a mean lifespan of 120

Unit 11: Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Systems

160

days; Hb broken into portoporphyrin (which is converted

to bilirubin and excreted by liver), iron (binds to

transferrin and returns to marrow erythroblasts) and

globin chains (broken down to amino acids which are

reutilized for general protein synthesis).

Intravascular hemolysis: it's abnormal process, RBCs

break down inside the vessels, free Hb binds to

haptoglobin and haemopexin or converted to

methaemalbumin. These proteins are cleared by the liver

where the haem is broken down to recover iron & produce

bilirubin. The excess free Hb is filtered by the glomerulus,

and free Hb will enter the urine (haemoglobinuria), as

iron is released, the renal tubules become loaded with

haemosiderin (haemosiderinuria).

Hereditary hemolytic anemias (usually caused by

intrinsic defect):

1) Membrane defects e.g. hereditary spherocytosis.

2) Metabolic defect e.g. G6PD deficiency.

3) Haemoglobin defects e.g. Hb S, Hb C.

Acquired hemolytic anemias (usually caused by an

extrinsic defect):

1) Immune:

Autoimmune e.g. autoimmune hemolytic anemia

(warm and cold type).

Alloimmune e.g. hemolytic transfusion reactions,

hemolytic disease of the newborn.

Drug associated e.g. penicillin, quinidine, methyldopa

2) Red cell fragmentation syndromes.

3) March haemoglobinaemia.

4) Infections (Malaria, meningococcal or pneumococcal

septicaemia).

5) Chemical & physical agents (Wilson's disease, lead,

spider venom, burn).

6) Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH)

Clinical features of hemolytic anemias:

1) Anemia and pallor of the mucous membranes.

2) Mild fluctuating jaundice.

3) Splenomegaly.

4) Dark urine (excess urobilinogen).

5) Pigment gall stones (bilirubin).

6) Aplastic crisis may precipitated by infection with

parvovirus or less frequently by folate deficiency.

7) Ulcers around the ankle (e.g. sickle cell anemia).

Main features of hemolytic anemia:

A. Increased red cell destruction

1) Serum unconjugated bilirubin increased:

Jaundice

Increased risk of gallstones.

2) Increased urine urinobilinogen and faecal

stercobilinogen.

3) Decreased serum haptoglobin and haemopexin.

4) Extravascular changes:

Splenomegaly.

Increased iron stores.

5) Intravascular changes:

Haemoglobinaemia (free Hb circulates in blood) and

haemoglobinuria (free Hb in urine).

Haemosiderinuria (haemosiderin in the urine, sign of

filtration of Hb through the kidney).

Methaemalbuminaemia (free Hb bound to albumin in blood).

Decreased iron stores.

B. Increased red cell production

1) Marrow expansion (bone changes)

2) Erythroid hyperplasia (decrease myeloid/erythroid ratio)

3) Reticulocytosis and polychromasia.

4) Increased folate requirements (macrocytosis).

C. Damaged red cells:

1) Morphology (e.g. microspherocytes, elliptocytes, fragments)

2) Osmotic fragility, autohaemolysis.

3) Short red cell survival and sites of destruction was

shown by 51Cr labelling study.

Hereditary spherocytosis

The inheritance is autosomal dominant. Hereditary

spherocytosis is usually extravascular hemolysis caused

by defects in the proteins of the red cell membranes. The

marrow produces red cells of normal biconcave shape but

these lose membrane and become increasingly spherical

as they circulate through the spleen. Ultimately, the

spherocytes are unable to pass through the splenic

microcirculation where they die prematurely. The

principal form of treatment is splenectomy.

Clinical features:

1) Anemia (can present at any age).

2) Fluctuating jaundice.

3) Splenomegaly.

4) Pigment gallstones.

5) Aplastic crises, usually precipitated by parvovirus

infection (increase in severity of anemia with low

reticulocytes count).

Laboratory findings:

1) Low Hb.

2) Reticulocytosis (reticulocytes count increased 5-20%).

3) Blood film show microspherocytes (smaller diameters

than normal red cells with no central pallor).

Unit 11: Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Systems

161

4) Osmotic fragility test is increased.

5) Autohaemolysis is increased & corrected by glucose.

6) The direct antiglobulin (Coomb's) test is normal.

GIucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase

deficiency (G6PD):

The inheritance is sex-linked, affecting males and carried

by females. G6PD functions to reduce NADP while

oxidizing glucose 6 phosphate. NADP is needed for the

production of reduced glutathione. G6PD deficiency

renders the red cell susceptible to oxidant stress

(infection, acute illness, drugs, fava beans). G6PD

deficiency is usually intravascular hemolysis.

Clinical features:

G6PD deficiency is usually asymptomatic, the main

syndromes that occur are as follows:

1) Acute haemolytic anemia in response to oxidant stress

(rapidly developing intravascular hemolysis with

fever, chills, low back pain and haemoglobinuria). The

anemia may be self-limiting as new young red cells

are made with near normal enzyme levels.

2) Neonatal jaundice.

3) Congenital non spherocytic hemolytic anemia (rare).

Laboratory findings:

Between crises

1) The complete blood picture and film are normal.

2) The G6PD enzyme deficient.

During crisis

1) Low Hb

2) High reticulocytes count

3) Blood film may show:

Contracted and fragmented cells (bite & blister cells)

which have had Heinz bodies removed by the spleen.

Heinz bodies (oxidized, denatured haemoglobin)

may be seen in the reticulocyte preparation.

4) Intravascular hemolysis features.

5) The G6PD enzyme assay may give a false normal

level (higher enzyme level in young red cells).

Treatment:

1) Remove oxidant stress (stop drug, treat infection).

2) A high urine output is maintained.

3) Blood transfusion (for severe anemia).

4) Phototherapy & exchange transfusion (in neonatal jaundice)

Immune haemolytic anemias

They are characterized by a positive direct antiglobulin

test (DAT) also known as the Coombs' test.

A. Autoimmune haemolytic anemias

Autoimmune haemolytic anemias are caused by antibody

production by the body against its own red & divided into:

1) Warm autoimmune haemolytic anemias:

Either idiopathic or secondary to SLE, CLL,

lymphomas and drugs (e.g. methyldopa).

The Ab is usually IgG and binds to red cells best at 37°C

Extra vascular hemolysis generally.

Blood film show prominent spherocytosis.

The DAT is positive.

2) Cold autoimmune haemolytic anemias

Either idiopathic or secondary to infections (Mycoplasma

pneumonia, infectious mononucleosis) or lymphoma.

The Ab is usually IgM and binds to red cells best at 4°C.

Both intravascular & extravascular hemolysis can occur

Blood film show red cells agglutinate & less spherocytosis.

The DAT is positive.

B. Alloimmune hemolytic anemias

Antibody produced by one individual reacts with red cells

of another. Two important situations:

1) Hemolytic transfusion reactions (transfusion of ABO

incompatible blood).

2) Hemolytic disease of the newborn (when the

molecules produced by the mother pass through the

Red cell fragmentation syndromes

These arise through physical damage to red cells either on

abnormal surfaces (e.g. artificial heart valves or arterial

grafts) or as a microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (red

cells passing through abnormal small vessels (e.g.

disseminated intravascular coagulation DIC or thrombotic

thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). The peripheral blood

contains many deeply staining red cell fragments.

March haemoglobinuria

This is caused by damage to red cells between the small

bones of the feet, usually during prolonged marching or

running. The blood film does not show fragments.

Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH)

PNH is a rare, acquired, clonal disorder of marrow stem

cells in which there is deficient synthesis of the GPI

anchor, a structure that attaches several surface proteins to

the cell membrane (such as CD55 and CD59). The net

result is that CD55 and CD59 are absent from the cell

surface of all the cells derived from the abnormal stem

cell and render red cells sensitive to lysis by complement.

The main clinical problem in PNH is chronic

Unit 11: Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Systems

162

intravascular hemolysis, thrombosis and pancytopenia.

PNH may be diagnosed by flowcytometry and Ham's test

(red cell lysis in serum at low pH).

Genetic disorders of haemoglobin

Thalassaemia: which is a group of inherited disorders of

haemoglobin synthesis characterized by a reduced or

absent one or more of the globin chains of adult

haemoglobin e.g.

thalassaemia and

thalassaemia.

Haemoglobin variant: which is a group of inherited

disorders of haemoglobin synthesis characterized by

abnormal synthesis of globin chains of adult

haemoglobin e.g. Hb S, Hb C.

Normal blood Hb:

1) Hb A - α2 β2 chains (represent > 95%).

2) Hb F - α2 γ2 chains (represent < 1%).

3) Hb A

2

- chains (represent 1.5 - 3.5%).

α Thalassaemia

α Thalassaemia usually caused by gene deletions.

Normally, there are four copies of the α globin gene

(

/

), the clinical severity can be classified according

to the number of genes that are missing or inactive.

A deficiency of α chains leads to the production of excess γ

or β chains, which form Hb Bart’ s (γ4) and Hb H (β4).

These soluble tetramers do not precipitate extensively in the

bone marrow and hence erythropoiesis is more effective

than in β thalassaemia. However, Hb H is unstable and

precipitates in red cells as they age. The inclusion bodies

cause red cell membrane damage & obstruction in the

spleen leading to shortened red cell survival.

Thalassaemia trait

The a thalassaemia traits are caused by loss of one (-

/

) (silent carrier) or two a genes (-

/-

or --/

)

(thalassaemia minor).

Usually not associated with anemia.

MCV and MCH are low.

Red cell count is over 5.5 x 10

12

/L.

Haemoglobin electrophoresis is normal.

a/β globin chain synthesis studies or DNA analyses are

needed to diagnosis.

Hb H disease

Hb H disease is caused by loss of three a genes (--/-

).

Hb H contains 4β globin chains.

Moderately severe anemia (Hb 7-11 g/dL).

Splenomegaly.

MCV and MCH are low.

Reticulocyte preparations show Hb H (golf ball appearance)

Haemoglobin electrophoresis is abnormal (Hb H).

Hydrops fetalis

Hydrops fetalis is caused by loss of four a genes (--/--)

a chain is essential in fetal as well as in adult Hb, Loss

of all 4 genes completely suppresses a chain synthesis,

it is incompatible with life and leads to death in utero.

Hb Barts contains 4γ globin chains.

β Thalassaemia

β Thalassaemia caused by point mutations rather than

gene deletions in majority of cases. The β thalassaemia trait

either no β chain (β

o

) or small amounts (β

+

) are synthesized.

Excess a chains precipitate in erythroblasts and in mature

red cells causing severe ineffective erythropoiesis and

hemolysis. The greater the α chain excess, the more severe

the anemia. Production of γ chains helps to 'mop up' excess

a chains and to ameliorate the condition.

β Thalassaemia major (Cooley Anemia)

It is often a result of inheritance of two different

mutations: either homozygous β

o

(β

o

β

o

) or β

+

(β

+

β

+

)

or

heterozygotes (β

o

β

+

) or compound heterozygotes with

other Hb variants.

Clinical features

1) Severe anemia becomes apparent at 3-6 months after

birth (when the switch from γ to β chain production

occur), anemia is transfusion dependent.

2) Hepato-splenomegaly occurs as a result of excessive

red cell destruction, extramedullary haemopoiesis and

later because of iron overload.

3) Expansion of bones caused by intense marrow

hyperplasia leads to bone deformities.

4) Iron overload caused by repeated transfusions (unless

chelation therapy initiated). Iron damages the liver,

heart, endocrine organs.

5) Infections.

Laboratory Features

1) Severe anemia (low Hb).

2) MCV and MCH are low.

3) Reticulocytes count Increased.

4) Blood film show hypochromic, microcytic RCs, many

nucleated red cells, target cells & basophilic stippling.

5) Hb electrophoresis reveals absence or very low of Hb

A, high Hb F and Hb A

2

percentage is normal, low or

slightly raised.

Unit 11: Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Systems

163

6) a/β globin chain synthesis studies show an increased a:

β ratio with reduced or absent β chain synthesis.

7) DNA analysis is used to identify the defect.

Treatment

1) Regular blood transfusions are needed to maintain

the Hb over 10 g/dL at all times.

2) Regular folic acid.

3) Iron chelation therapy is used to treat iron overload

e.g. Desferrioxamine, Deferiprone and Deferasirox.

4) Splenectomy may be needed to reduce blood requirements.

Thalassaemia intermedia

Thalassaemia intermedia is a term used to define a group

of patients with

β

thalassaemia in whom the clinical

severity of the disease is spectrum range from mild

symptoms of the β thalassaemia trait to the severe

manifestations of β thalassaemia major. The diagnosis is a

clinical one that is based on the patient maintaining a

satisfactory Hb level of at least 6-7 g/dL at the time of

diagnosis without the need for regular blood transfusions

(not transfusion dependent). This is a clinical syndrome

which may be caused by a variety of genetic defects.

β Thalassaemia minor

β Thalassaemia trait is ββ

+

or ββ

o

.

Asymptomatic.

Mild anemia (Hb 10-12 g/dL).

MCV and MCH very low.

High red cell count (> 5.5 x 10

12

/L).

Haemoglobin electrophoresis show raised Hb A

2

(> 3.5%)

If both parents carry β thalassaemia trait, there is a 25%

risk of a thalassaemia major child. Therefore, prenatal

genetic counseling is important to patients with a partner

who also has a significant Hb disorder.

Haemoglobin S (Hb S)

Hb S is inherited Hb variant, the abnormality is caused by

substitution of valine for glutamic acid in position 6 in the

β globin chain (β change to S).

Hb S is insoluble and forms crystals when exposed to low

oxygen tension (e.g. hypoxia, dehydration, infections, cold

exposure) & the red cells sickle & may block different areas

of the microcirculation causing infarcts of various organs.

Sickle cell anemia (homozygous, Hb SS)

Clinical features

1) Severe haemolytic anemia punctuated by crises. The

symptoms of anemia are mild in relation to the

severity of the anemia because Hb S gives up oxygen

to tissues relatively easily compared with Hb A.

2) Painful vaso-occlusive crises (infarcts can occur in a

variety of organs including the bones, lung, kidney and

the spleen).

3) Visceral sequestration crises (sickling within organs &

pooling of blood) with a severe exacerbation of anemia

4) Aplastic crises occur as a result of infection with

parvovirus or from folate deficiency (sudden fall in Hb

and reticulocytes count).

5) Haemolytic crises (increased rate of haemolysis with a

fall in Hb but rise in reticulocytes count).

6) Other clinical features: ulcers of the lower legs are

common. The spleen is enlarged in infancy and early

childhood but later is often reduced in size as a result

of infarcts (autosplenectomy). Pulmonary

hypertension, a proliferative retinopathy and priapism.

Laboratory findings

Hb is usually 6-9 g/dL.

Blood film show sickle cells, target cells, Howell Jolly

bodies.

Screening tests for sickling are positive when the

blood is deoxygenated (e.g. sodium metabisulphite).

Haemoglobin electrophoresis: Hb S is high, no Hb A

is detected and Hb F is variable amount (5-15%).

Treatment

Avoid factors known to precipitate crises e.g.

dehydration, anoxia, infections and cold exposure.

Regular folic acid.

Crises: treat by rest, warmth, rehydration, antibiotics,

analgesia, exchange transfusion (aim to reduce Hb S

less than 30%).

Blood transfusion (given only in severe anemia with

symptoms).

Hydroxyurea can increase Hb F.

Sickle cell trait (Heterozygous, Hb βS)

Benign condition with no anemia and normal

appearance of red cells on a blood film (unless

exposed to low oxygen tension).

Impaired urine concentrating ability and haematuria

can occur (due to minor infarcts of the renal papillae).

Haemoglobin electrophoresis: The ratio of Hb A to Hb

S is 60 : 40%

Unit 11: Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Systems

164

WHITE CELL DISORDERS

Acute leukaemia

Genetic damage is believed to involve several key

biochemical steps resulting in: an increased rate of

proliferation; reduced apoptosis and a block in cellular

differentiation. Together these events cause accumulation

of the early bone marrow haemopoietic cells (blast cells).

Acute leukaemia is defined as the presence of over 20%

of blast cells in the blood or bone marrow at clinical

presentation. It can be diagnosed with even less than 20%

blasts if specific leukaemia associated cytogenetic or

molecular genetic abnormalities are present, types:

1) Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML).

2) Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL).

The aetiology of leukemia:

1) Inherited factors: e.g. Down's syndrome, Fanconi's

anemia.

2) Environmental influences:

Chemicals: chronic exposure to benzene or industrial

solvents may cause AML.

Chemotherapy: alkylating agents and melphalan

predispose to AML.

Ionizing radiation.

Infection: HTLV-1 cause Adult T-cell leukemia

Lymphoma.

3) Preleukemic syndrome: e.g. myelodysplastic syndrome,

myeloproliferative neoplasm.

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL)

ALL is the most common malignancy of childhood (highest

at 3-7 years), a secondary rise after the age of 40 years.

The common precursor B type (CDI0+) is the most usual

in children. has an equal sex incidence but there is a male

predominance for T-cell ALL (T-ALL).

Classification

is usually based on the:

1) Morphology: French American British (FAB) classification:

The L1 type show uniform, small blast cells with scanty

cytoplasm.

The L2 type comprise larger blast cells with more

prominent nucleoli & cytoplasm & with more heterogeneity

The L3 blasts are large with prominent nucleoli, strongly

basophilic cytoplasm and cytoplasmic vacuoles.

2) Immunophenotype: Immunological markers can be used to

divide ALL cases into early pre-B, pre-B, B& T-cell subtypes

3) Chromosomes and genetic analysis:

Hyperdiploid (cells have >50 chromosomes) or hypodiploid.

t(12; 21) TEL-AMLl translocation.

t(9; 22) Philadelphia chromosome.

llq23 Translocations (MLL gene).

Clinical features

1) Bone marrow failure:

Anemia (fatigue, pallor).

Neutropenia (infections).

Thrombocytopenia (spontaneous bruises, bleeding).

2) Organ infiltration:

Bone pain.

Lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly (moderate) and

hepatomegaly.

Meningeal syndrome (headache, nausea and vomiting,

blurring of vision and diplopia).

Testicular swelling or signs of meditational

compression in T-ALL.

Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML)

It is the common form of acute leukaemia in adults and is

increasingly common with age. AML forms only a minor

fraction (10-15%) of the leukaemias in childhood.

Classification

is usually based on the:

1) Morphology (FAB criteria):

AML M0 undifferentiated form.

AML M1 without maturation.

AML M2 with granulocytic maturation.

AML M3 acute promyelocytic.

AML M4 granulocytic and monocytic maturation.

AML M5 monoblastic (M5a) or monocytic (M5b).

AML M6 erythroleukaemia.

AML M7 megakaryoblastic.

2) Immunophenotype: CDI3, CD33, CD117, Glycophorin

(M6), platelet antigens (e.g. CD41) in (M7) and

myeloperoxidase in (M0).

3) Chromosomes and genetic analysis:

Normal karyotype.

t(8; 21), t(15; 17) and inv(16).

Nucleophosmin (NPM) gene mutations

Internal tandem repeats of the FLT-3 gene.

Clinical features

1) Bone marrow failure:

Anemia (fatigue, pallor).

Neutropenia (infections).

Thrombocytopenia (spontaneous bruises, bleeding).

Unit 11: Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Systems

165

2) Organ infiltration:

Gum hypertrophy, skin involvement and CNS disease

are characteristic of the AML M4 and M5.

Granulocytic sarcoma (isolated mass of leukaemic blasts)

3) Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is

characteristic of the AML M3.

Laboratory findings:

1) Complete blood picture:

Normochromic, normocytic anemia.

Thrombocytopenia.

The total white cell count may be decreased, normal or

increased to 200 x 10

9

/l or more.

2) Blood film shows a variable numbers of blast cells.

3) The bone marrow hypercellular with >20% leukaemic

blasts.

4) CSF examination may show leukaemic cells.

5) Coagulation tests for DIC are often positive in patients

with AML M3.

6) Biochemical tests: serum uric acid and serum lactate

dehydrogenase increased.

7) Radiography: may reveal lytic bone lesions or a

meditational mass (enlargement of the thymus and/or

lymph nodes characteristic of T-ALL).

Differentiation of ALL from AML

1) Morphology: lymphoblast vs. myeloblast (Auer rods).

2) Cytochemistry (special stains):

Myeloperoxidase and Sudan black are positive in

AML (including Auer rods) but negative in ALL.

Nonspecific esterase is positive in AML M4 and M5

but negative in ALL.

Periodic acid Schiff is positive in ALL (coarse block),

also positive in AML M6 (fine blocks).

Acid phosphatase is positive in T-ALL (Golgi

staining), also positive in AML M6 (diffuse).

3) Immunoglobulin and TCR genes:

Precursor B-ALL show clonal rearrangement of

immunoglobulin genes.

T-ALL show clonal rearrangement of TCR genes.

AML show germline configuration of

Immunoglobulin and TCR genes.

4) Immunophenotype:

AML show positive CDI3 and CD33.

B ALL show positive CD19, cCD22 and TdT.

T ALL show positive cCD3, CD7 and TdT.

5) Chromosomes and genetic analysis

Treatment

General supportive therapy for bone marrow failure

includes blood product support, treat infections, DIC and

prevention of tumour lysis syndrome.

Chemotherapy and sometimes radiotherapy (different

protocols according to age), several phases:

1) Remission induction: the aim is to rapidly kill most

of the tumour cells and get the patient into remission

(less than 5% blasts in the bone marrow).

2) Consolidation (Intensification): two or three courses

use high doses of multidrug chemotherapy in order to

completely reduce or eliminate the tumour burden to

very low levels.

3) CNS prophylaxis: to prevent or treat central nervous

system disease (only for ALL).

4) Maintenance therapy for 2 to 3 years (for ALL and

AML M3 only).

Stem cell transplantation reduces the rate of relapse but

adds further toxicity to the treatment.

All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) therapy is given in

conjunction with chemotherapy for the M3 disease.

Poor prognostic factor in ALL:

1) High WBC at presentation (e.g. >50 x 10

9

/L).

2) Boys.

3) T-ALL Immunophenotype in children.

4) Age: adult or infant <2 years.

5) Cytogenetics: Ph+, llq23 rearrangements.

6) Time to clear blasts from blood (>1 week)

7) Time to remission (>4 weeks)

8) CNS disease at presentation

9) Minimal residual disease still positive at 3-6 months.

Prognostic factor in AML:

1) Cytogenetics: t(15; 17), t(8; 21), inv(16) and NPM

mutation carry better prognosis than other

chromosomes and genetic lesion.

2) Bone marrow response to remission induction: <5%

blasts after first course show better prognosis.

3) Age of patient: <60 years show better prognosis than >

60 years.

4) Onset: primary show better prognosis than secondary.

Unit 11: Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Systems

166

Chronic Leukaemia

The chronic leukaemias have slower progression.

Paradoxically, they are also more difficult to cure.

Chronic leukaemias can be subdivided into:

Chronic myeloid leukaemia represent about

15% of all leukaemias.

25% of all leukaemias.

Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML)

Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) is a clonal disease that

results from an acquired genetic change in a stem cell.

This altered stem cell proliferates and generates a

population of differentiated cells that gradually displaces

normal haemopoiesis and leads to a greatly expanded total

myeloid mass. CML has three phases: chronic phase,

accelerated phase and blastic crisis.

Leukaemogenesis

Philadelphia chromosome is an acquired cytogenetic

anomaly that is characterizes in all leukaemic cells in CML.

90-95% of CML patients have Ph chromosome.

Reciprocal translocation of chromosome 22 and

chromosome 9; t(9;22).

BCR-ABL1 fusion gene generate a fusion protein that has

tyrosine kinase activity in excess of the normal. Growth

and survival of hematopoietic cells increased and become

independent of cytokines.

Clinical features

Chronic phase

The median age of onset is 50 - 60 years. The incidence is

slightly higher in males than in females.

Asymptomatic, 50% of CML can be discovered in a

routine blood examination.

CML patients may present with:

Anemia (fatigue, shortness of breath).

Haemorrhage (bruising or bleeding).

Abdominal discomfort (splenomegaly).

Weight loss.

Excessive sweating.

Less frequent symptoms:

Splenic infarction (left upper-quadrant and left

shoulder pain).

Leucostasis features (very high leucocyte counts) e.g.

headache, blurred vision, cerebrovascular accidents

and dyspnea.

Visual disturbances (retinal haemorrhages).

Gout.

Blastic transformation

Spleen is frequently enlarged and may be painful.

Liver may become very large.

Fever and lymphadenopathy (rare in chronic phase).

Lytic lesions of bone (rare).

Laboratory findings:

Chronic phase

1) Hb low (normochromic, normocytic anemia).

2) WBCs count is high (20 – 200 × 10

9

/L).

3) Platelet numbers are usually increased, normal or even reduced.

4) Blood film shows:

A full spectrum of granulocyte series cells, ranging

from blast forms to mature neutrophils (myelocytes

and neutrophils predominating).

Blast less than 12%.

The percentages of eosinophils and basophils are

usually increased.

5) Bone marrow aspirate shows:

Hypercellular fragments and trails.

A full spectrum of granulocyte series cells (resembling

that of CML blood).

Blast cells in chronic phase 2 – 10%.

Eosinophils and basophils are usually prominent.

Megakaryocytes are very numerous.

6) Bone marrow biopsy shows:

Hypercellularity (complete loss of fat spaces).

The reticulin content (fibrosis) may be normal or increased.

7) Neutrophils alkaline phosphatase score is invariably low

(increase in infections).

8) BCR – ABL1 transcripts can be demonstrated in the blood

(diagnostic) using real time quantitative polymerase chain

reaction (RQ - PCR).

9) Serum uric acid is usually normal or slightly raised.

Lactate dehydrogenase is usually raised.

10) The serum vitamin B

12

and B

12

binding capacity are

greatly increased.

Accelerated phase:

1) Anemia in the presence of a normal leucocyte count.

2) Platelets number may be greatly increased (>1000 ×

10

9

/L) or reduced (< 100 × 10

9

/L) in a manner not

accounted for by treatment.

3) Basophilia ≥ 20%.

4) The marrow shows increased numbers of blast cells (10 -

19 %) or fibrosis.

5) Serum uric acid increased

Blastic crisis: Blastic crisis is defined by the presence

of more than 20% blasts in the blood or marrow.

Unit 11: Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Systems

167

Treatment

1) Tyrosine kinase inhibitor: Imatinib mesylate (Glivec,

Gleevec).

2) Chemotherapy: Hydroxyurea, Busulfan.

3) Interferon Alfa.

4) Allogeneic stem cell transplant.

Course and prognosis

CML usually shows an excellent response to imatinib in

the chronic phase.

If death occurs it is usually from terminal acute

transformation or from intercurrent haemorrhage or

infection.

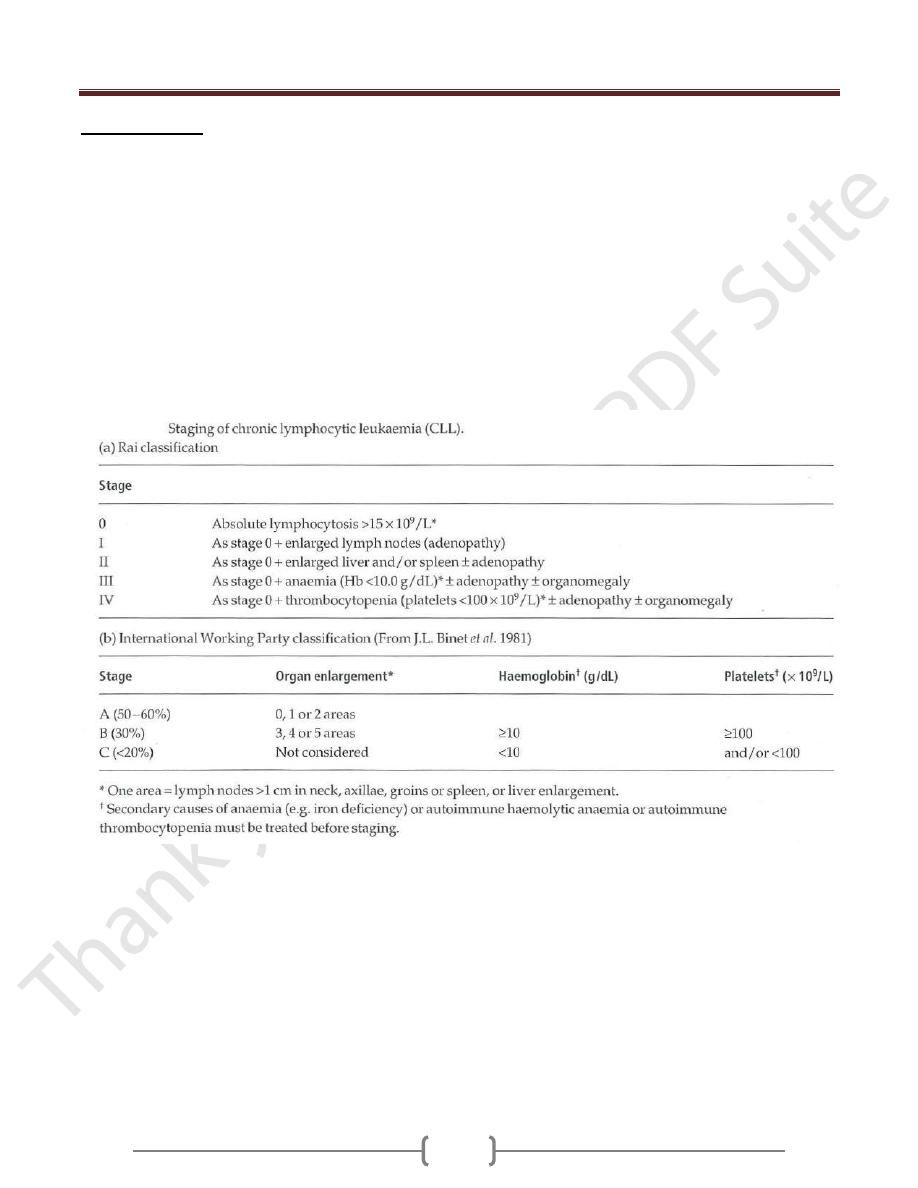

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL)

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) is the most

common form of leukemia in adults over the age of 50

years. The tumour cell appears to be a relatively mature B

cell with weak surface expression of IgM or IgD. The

cells accumulate in the blood, bone marrow, liver, spleen

and lymph nodes as a result of a prolonged lifespan with

impaired apoptosis.

Cytogenetics:

The most common chromosomes abnormalities are:

Deletion of 13q14.

Trisomy 12.

Deletions at llq23.

Structural abnormalities of 17p involving the p53 gene

Clinical features

1) Peak incidence between 60 and 80 years of age. The male

to female ratio is 2 : 1.

2) Most cases are diagnosed when a routine blood test is

performed.

3) Symmetrical enlargement of cervical, axillary or inguinal

lymph nodes is the most frequent clinical sign. The nodes

are usually discrete and non tender.

4) Anemia may be present.

5) Thrombocytopenia may be present (bruising or purpura).

6) Splenomegaly and, less commonly, hepatomegaly are

common in later stages.

7) Infection (bacterial, viral or fungal) due to immune

suppression (resulting from hypogammaglobulinaemia

and cellular immune dysfunction).

Laboratory findings

1) Lymphocytosis. The absolute lymphocyte count is >5 x

10

9

/L and may be up to 300 X 10

9

/L or more.

2) Blood film shows small mature lymphocytes, smudge or

smear cells.

3) Immunophenotyping of the lymphocytes shows:

CD19+ (B cells).

Weakly expressing of surface IgM or IgD.

Expression of only one form of light chain, either κ or

λ (monoclonal).

CD5+ and CD23+ but CD79b - and FMC7- (characteristic).

4) Normocytic normochromic anaemia is present in later

stages as a result of marrow infiltration, hypersplenism or

autoimmune haemolysis.

5) Thrombocytopenia occurs in later stages.

6) Bone marrow aspiration shows lymphocytic replacement

of normal marrow elements. Lymphocytes comprise 25-

95% of all the cells.

7) Bone marrow biopsy reveals nodular, diffuse or

interstitial involvement by lymphocytes.

8) Reduced concentrations of serum Ig.

9) Autoimmunity directed against cells of the haemopoietic

system is common. Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia is

most frequent but immune thrombocytopenia, neutropenia

and red cell aplasia are also seen.

Good Prognostic markers:

1) Stage: Binet A (Rai 0-1).

2) Female.

3) Slow lymphocyte doubling time.

4) Nodular infiltration in bone marrow biopsy.

5) Cytogenetics: Deletion 13q14.

6) Ig genes mutation status: hypermutated (unmutated Ig

genes has an unfavorable prognosis).

7) Negative CD38 expression.

8) Low ZAP-70 expression.

9) Low CLLU.l expression.

10) Normal LDH.

Treatment:

1) Chemotherapy: alkylating agent or Purine analogues.

2) Monoclonal antibodies: Campath-1H (anti-CD52),

Rituximab (anti CD20).

3) Others: corticosteroids, radiotherapy, splenectomy, Ig replacement.

4) Allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

Unit 11: Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Systems

168

Course of disease

Many patients in Binet stage A or Rai stage 0 or I never

need therapy.

For those who do need treatment, typical pattern is that of

a disease that is responsive to several courses of

chemotherapy before the gradual onset of extensive bone

marrow infiltration, bulky disease and recurrent infection.

The disease may transform into a high grade lymphoma

(Richter's transformation) or there may be the appearance

of an increasing number of prolymphocytes that are

resistant to treatment.