Unit 5: Neoplasia

77

Nomenclature

Benign Tumors

Malignant Tumors

Unit 5: Neoplasia

78

Unit 5: Neoplasia

79

Characteristics of benign andmalignant neoplasms

1) Malignant transformation (Differentiation and Anaplasia)

Unit 5: Neoplasia

80

Dysplasia

Unit 5: Neoplasia

81

2) Rate of Growth (Growth rate of transformed cells)

Unit 5: Neoplasia

82

3) Local Invasion

4) Metastasis

Unit 5: Neoplasia

83

Epidemiology of neoplasm

Cancer epidemiology can contribute substantially to

knowledge about the origin of cancer. Now well-

established concept that cigarette smoking is causally

associated with lung cancer arose primarily from

epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology of cancer is focused

on several subjects which are:

Cancer incidence

Incidence of cancers all over the world will give idea

about the effect of prevention and treatment cancers.

Over several decades, the death rates of many forms of

malignant neoplasia have changed. Particularly notable is

the significant increase in the overall cancer death rate

among men that was attributable largely to lung cancer, but

this has finally begun to drop. In contrast, the overall death

rate among women has fallen slightly, mostly as a result of

the decline in death rates from cancers of the uterine cervix,

stomach, and large bowel. These welcome trends have

more than counterbalanced the striking climb in the rate of

lung cancer among women, which not long ago was a

relatively uncommon form of neoplasia in this sex. The

declining death rate from cervical cancer is directly related

to widespread use of cytologic smear studies for early

detection of this tumor while it is still curable. The causes

of decline in death rates for cancers of the stomach are

obscure; however, there have been speculations about

decreasing exposure to dietary carcinogens.

Geographical and environmental factors

The incidences of certain cancer are different from on

area to other in our world this may be due to certain

environmental or genetic factors that may occur due to

certain environmental factors.

This notion is supported by the geographic differences in

death rates from specific forms of cancer. For example,

death rates from breast cancer are about fourfold to

fivefold higher in the United States and Europe compared

with Japan. Conversely, the death rate for stomach

carcinoma in men and women is about seven times higher

in Japan than in the United States. Liver cell carcinoma is

relatively infrequent in the United States but is the most

lethal cancer among many African populations. Nearly all

the evidence indicates that these geographic differences

are environmental rather than genetic in origin.

Age

In general, the frequency of cancer increases with age.

Most cancer mortality occurs between ages 55 and 75; the

rate declines, along with the population base, after age 75.

The rising incidence with age may be explained by:

1) The accumulation of somatic mutations associated

with the emergence of malignant neoplasms.

2) The decline in immune competence that accompanies

aging also may be a factor.

Cancer causes slightly more than 10% of all deaths among

children younger than 15years. The major lethal cancers in

children are leukemia, tumors of the central nervous

system, lymphomas, soft tissue sarcomas & bone sarcomas.

Heredity

The evidence now indicates that for many types of cancer,

including the most common forms, there exist not only

environmental influences but also hereditary

predispositions. Hereditary forms of cancer can be

divided into three categories

A- Inherited cancer syndromes: (Autosomal

dominant pattern)

Inherited cancer syndromes include several well-defined

cancers in which inheritance of a single mutant gene

greatly increases the risk of developing a tumor. The

predisposition to these tumors shows an autosomal

dominant pattern of inheritance. Childhood

retinoblastoma is the most striking example of this

category.

Tumors within this group often are associated with a

specific marker phenotype. There may be multiple benign

tumors in the affected tissue, as occurs in familial polyposis

of the colon and in multiple endocrine neoplasia.

B – Familial cancers

Virtually all the common types of cancers that occur

sporadically have been reported to occur in familial

forms. Examples include carcinomas of colon, breast,

ovary, and brain. Features that characterize familial

cancers include early age at onset, tumors arising in two

or more close relatives of the index case, and sometimes

multiple or bilateral tumors. Familial cancers are not

associated with specific marker phenotypes. For example,

in contrast to the familial adenomatous polyposis

syndrome, familial colonic cancers do not arise in

preexisting benign polyps. The transmission pattern of

familial cancers is not clear.

Unit 5: Neoplasia

84

C- Autosomal recessive syndromes (Defective

DNA repair)

Besides the dominantly inherited precancerous conditions,

a small group of autosomal recessive disorders is

collectively characterized by chromosomal or DNA

instability. One of the best-studied examples are

xeroderma pigmentosum, Fanconi anemia, ataxic

talangectsia. in which DNA repair is defective.

Acquired Preneoplastic Disorders

In addition to the genetic influences described earlier,

certain clinical conditions are well-recognized

predispositions to the development of malignant neoplasia

and are referred to as preneoplastic disorders. This

designation is unfortunate because it implies a certain

inevitability, but in fact, although such conditions may

increase the likelihood, in most instances cancer does not

develop. A brief listing of the chief conditions follows:

* Persistent regenerative cell replication (e.g., squamous

cell carcinoma in the margins of a chronic skin fistula or

in a long-unhealed skin wound; hepatocellular carcinoma

in cirrhosis of the liver)Hyperplastic and dysplastic

proliferations (e.g., endometrial carcinoma in atypical

endometrial hyperplasia; bronchogenic carcinoma in the

dysplastic bronchial mucosa of habitual cigarette

smokers)Chronic atrophic gastritis (e.g., gastric

carcinoma in pernicious anemia or following long-

standing Helicobacter pylori infection)Chronic ulcerative

colitis (e.g., an increased incidence of colorectal

carcinoma in long-standing disease)Leukoplakia of the

oral cavity, vulva, or penis (e.g., increased risk of

squamous cell carcinoma)Villous adenomas of the colon

(e.g., high risk of transformation to colorectal carcinoma)

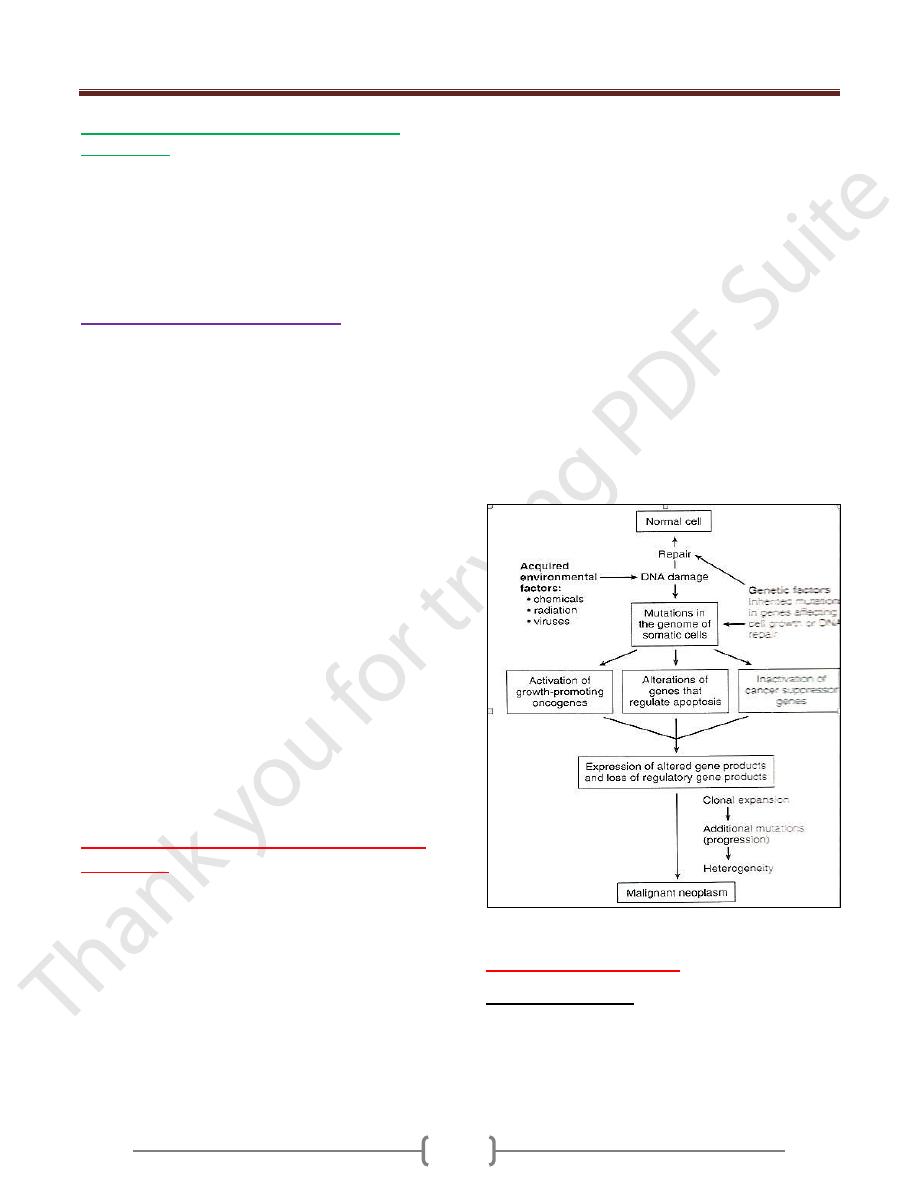

Carcinogenesis: the molecular basis

of cancer

Non-lethal genetic damage lies at the heart of

carcinogenesis. Such genetic damage (or mutation) may

be acquired by the action of environmental agents, such as

chemicals, radiation, or viruses, or it may be inherited in

the germ line. The genetic hypothesis of cancer implies

that a tumor mass results from the clonal expansion of a

single progenitor cell that has incurred genetic damage

(i.e., tumors are monoclonal).

Four classes of normal regulatory genes-growth-

promoting proto-oncogenes, growth-inhibiting tumor

suppressor genes, genes that regulate programmed cell

death (i.e., apoptosis), and genes involved in DNA repair-

are the principal targets of genetic damage. Collectively

the genetic alterations in tumor cells confer upon them

growth and survival advantages over normal cells.

Carcinogenesis is a multi-steps process resulting from the

accumulation of multiple mutations. Over a period of time

many tumors become more aggressive by acquiring

greater malignant potential .This phenomena is referred to

as tumor progression. Increasing malignancy is often

acquired step by step. At the molecular level, tumor

progression result from multiple mutations that

accumulate independently in different cells generating

subclones with different characteristics such as ability to

invade, rate of growth, metastatic ability, hormonal

responsiveness and susceptibility to anti neoplastic drugs.

Even though most malignant tumors are monoclonal in

origin by the time they become clinically evident their

constituent cells are extremely hetrogenous.

Illustration of Pathogenesis of cancer

Hallmarks of cancer

Cancer critical genes

These genes are had a role in seven fundamental changes in

cell physiology that together determine its malignant attributes

1) Self-sufficiency in growth signals

2) Insensitivity to growth-inhibitory signals

3) Evasion of apoptosis

Unit 5: Neoplasia

85

4) Limitless replicative potential (i.e., overcoming cellular

senescence and avoiding mitotic catastrophe)

5) Development of sustained angiogenesis

6) Ability to invade and metastasize

7) Genomic instability resulting from defects in DNA repair

Mutation in genes that regulate some or all of the above

cellular traits are seen in every cancer and hence these

will form the basis of the molecular origins of cancer.

1- Self – sufficiency in growth signals

Genes that promote autonomous cell growth in cancer cells

are called oncogenes. They are derived by mutations in

proto-oncogenes and are characterized by the ability to

promote cell growth in the absence of normal growth-

promoting signals. Their products, called oncoproteins,

resemble the normal products of proto-oncogenes except

that oncoproteins are devoid of important regulatory

elements & their production in the transformed cells does

not depend on growth factors or other external signals.

Under physiologic conditions, cell proliferation can be

readily resolved into the following steps:

1) The binding of a growth factor to its specific receptor on

the cell membrane

2) Transient and limited activation of the growth factor

receptor, which in turn activates several signal- transducing

proteins on the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane

3) Transmission of the transduced signal across the cytosol

to the nucleus via second messengers or a cascade of

signal transduction molecules

4) Induction and activation of nuclear regulatory factors that

initiate DNA transcription

5) Entry and progression of the cell into the cell cycle,

resulting ultimately in cell division.

Self – sufficiency involve the following

A – Growth factors

All normal cells require stimulation by growth factors to

undergo proliferation. Most soluble growth factors are

made by one cell type and act on a neighboring cell to

stimulate proliferation (paracrine action). Many cancer cells

acquire growth self-sufficiency, however, by acquiring the

ability to synthesize the same growth factors to which they

are responsive. For example, many glioblastomas secrete

platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and express the

PDGF receptor, and many sarcomas make both

transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α) and its receptor.

B- Growth factors receptors

Mutant genes present in two forms:

1) Formation of mutant receptor protein that deliver

continuous mitogenic signals to cells even in the absence

of the relevant growth factor in the environment.

2) Overexpression of growth factor receptors that render

cancer cells hyper-responsive to levels of growth factor that

would not normally trigger proliferation. As examples are

EGF (epidermal growth factor) overexpression in 80% of

squamous cell carcinoma. HER/NEU receptor is amplified

in 25% of breast carcinoma which indicated bad prognosis.

C- Single – transducing proteins

A relatively common mechanism by which cancer cells

acquire growth autonomy is mutations in genes that

encode various components of the signaling molecules

couple growth factor receptors to their nuclear targets.

Many such signaling proteins are associated with the

inner leaflet of the plasma membrane, where they receive

signals from activated growth factor receptors and

transmit them to the nucleus, either through second

messengers or through a cascade of phosphorylation and

activation of signal transduction molecules. Two

important members in this category are RAS and ABL.

D – Nuclear transcription factors:

Transcription is the synthesis of messenger RNA (mRNA)

from a DNA this is a key step in the formation of protein

coded by DNA. Transcription factors are proteins

necessary for RNA polymerase to initiate transcription of

mRNA molecule from its DNA template.

As example of this group (MYS) gene which showed

mutation by translocation between chromosomes (8 : 14)

which occur in burkitt lymphoma & also breast, colon, lung.

E – cyclins and cyclin – dependent Kinase (CDKs).

They are activated by binding to cyclins (so called because

of cyclic nature of their production and degradation). The

CDK- cyclin complexes activate the crucial RB protein that

derives the cell cycle. On completion of this task, cyclin

levels decline rapidly. Cyclin D, E , A , and B appear

sequentially during the cell cycle to one or more CDK.

Mutation that dsregulate the activity of cyclins and CDKs

would favor cell proliferation .The cyclin D genes are

overexpressed in many cancers including breast, esophagus,

melanoma, sarcom. While cyclins activate the CDKs their

inhibitors (CDKIs) such as (P21 ,P 27 and P57 ) silence the

CDKs and exert negative control the cell cycle. The CDKIs

are frequently mutated or otherwise silenced in many

malignancies. (Pancreatic, esophagus or glioblastoma.

Unit 5: Neoplasia

86

2) Insensitivity to Growth Inhibitory Signals

RB Gene: Governor of the Cell Cycle

P53 Gene: Guardian of the Genome

Unit 5: Neoplasia

87

Transforming Growth Factor-β Pathway (TGF-β)

Adenomatous polyposis Coli-β-Catenin Pathway

3) Avoidance of apoptosis

Unit 5: Neoplasia

88

4) Unlimited replicative potential

5) Development of sustain angiogenesis

Unit 5: Neoplasia

89

6) Invasion & Metastasis

Unit 5: Neoplasia

90

Unit 5: Neoplasia

91

Etiology of cancer: carcinogenic agents

Three classes of carcinogenic agents can be identified:

(1) chemicals, (2) radiant energy, and (3) microbial

agents. Chemicals and radiant energy are documented

causes of cancer in humans, and oncogenic viruses are

involved in the pathogenesis of tumors in several animal

models and at least in some human tumors. In the

following discussion, each class of agents is considered

separately, but it is important to note that several may act

in concert or sequentially to produce the multiple genetic

abnormalities characteristic of neoplastic cells.

Chemical Carcinogens

Direct-Acting Agents

Direct-acting agents require no metabolic conversion to

become carcinogenic. They are in general weak

carcinogens but are important because some of them are

cancer chemotherapeutic drugs (e.g., alkylating agents)

that have successfully cured, controlled, or delayed

recurrence of certain types of cancer (e.g., leukemia,

lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and ovarian carcinoma),

only to evoke later a second form of cancer, usually

leukemia. This situation is even more tragic when their

initial use has been for non-neoplastic disorders, such as

rheumatoid arthritis or Wegener granulomatosis. The risk

of induced cancer is low, but its existence dictates

judicious use of such agents.

Indirect-Acting Agents

The designation indirect-acting agent refers to chemicals

that require metabolic conversion to an ultimate

carcinogen before they become active. Some of the most

potent indirect chemical carcinogens-the polycyclic

hydrocarbons-are present in fossil fuels. For example,

benzo[a]pyrene and other carcinogens are formed in the

high-temperature combustion of tobacco in cigarette

smoking. These products are implicated in the causation

of lung cancer in cigarette smokers. Polycyclic

hydrocarbons may also be produced from animal fats

during the process of broiling meats and are present in

smoked meats & fish. The principal active products in

many hydrocarbons are epoxides, which form covalent

adducts (addition products) with molecules in the cell,

principally DNA, but also with RNA and proteins.

The aromatic amines and azo dyes are another class of

indirect-acting carcinogens. Before its carcinogenicity was

recognized, β-naphthylamine was responsible for a 50-fold

increased incidence of bladder cancers in heavily exposed

workers in the aniline dye and rubber industries. Many

other occupational carcinogens. Because indirect-acting

carcinogens require metabolic activation for their

conversion to DNA-damaging agents, much interest is

focused on the enzymatic pathways that are involved, such

as the cytochrome P-450-dependent monooxygenases. The

genes that encode these enzymes are polymorphic, and

enzyme activity varies among different individuals. It is

widely believed that the susceptibility to chemical

carcinogenesis depends at least in part on the specific allelic

form of the enzyme inherited. Thus, it may be possible in

the future to assess cancer risk in a given individual by

genetic analysis of such enzyme polymorphisms.

A few other agents merit brief mention. Aflatoxin B

1

is of

interest because it is a naturally occurring agent produced

by some strains of Aspergillus, a mold that grows on

improperly stored grains and nuts. There is a strong

correlation between the dietary level of this food

contaminant &the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in

some parts of Africa and the Far East. Additionally, vinyl

chloride, arsenic, nickel, chromium, insecticides, fungicides

& polychlorinated biphenyls are potential carcinogens in

the workplace and about the house. Finally, nitrites used as

food preservatives have caused concern, since they cause

nitrosylation of amines contained in the food. The

nitrosoamines so formed are suspected to be carcinogenic.

Mechanisms of Action of Chemical Carcinogens

Because malignant transformation results from mutations,

it should come as no surprise that most chemical

carcinogens are mutagenic. Indeed, all direct and ultimate

carcinogens contain highly reactive electrophile groups

that form chemical adducts with DNA, as well as with

proteins and RNA. Although any gene may be the target

of chemical carcinogens, the commonly mutated

oncogenes and tumor suppressors, such as RAS and p53,

are important targets of chemical carcinogens. Indeed,

specific chemical carcinogens, such as aflatoxin B

1

,

produce characteristic mutations in the p53 gene, such

that detection of the "signature mutation" within the p53

gene establishes aflatoxin as the causative agent. These

associations are proving useful tools in epidemiologic

studies of chemical carcinogenesis.

Carcinogenicity of some chemicals is augmented by

subsequent administration of promoters (e.g., phorbol

esters, hormones, phenols, and drugs) that by themselves

are nontumorigenic. To be effective, repeated or sustained

exposure to the promoter must follow the application of

the mutagenic chemical, or initiator. The initiation-

promotion sequence of chemical carcinogenesis raises an

important question: Since promoters are not mutagenic,

Unit 5: Neoplasia

92

how do they contribute to tumorigenesis? Although the

effects of tumor promoters are pleiotropic, induction of

cell proliferation is a sine qua non of tumor promotion. It

seems most likely that while the application of an initiator

may cause the mutational activation of an oncogene such

as RAS, subsequent application of promoters leads to

clonal expansion of initiated (mutated) cells. Forced to

proliferate, the initiated clone of cells accumulates

additional mutations, developing eventually into a

malignant tumor. Indeed, the concept that sustained cell

proliferation increases the risk of mutagenesis, and hence

neoplastic transformation, is also applicable to human

carcinogenesis. For example, pathologic hyperplasia of

the endometrium) and increased regenerative activity that

accompanies chronic liver cell injury are associated with

the development of cancer in these organs. Were it not for

the DNA repair mechanisms discussed earlier, the

incidence of chemically induced cancers in all likelihood

would be much higher. As mentioned above, the rare

hereditary disorders of DNA repair, including xeroderma

pigmentosum, are associated with greatly increased risk of

cancers induced by UV light and certain chemicals.

Radiation Carcinogenesis

Radiation, whatever its source (UV rays of sunlight, x-

rays, nuclear fission, radionuclides) is an established

carcinogen. Unprotected miners of radioactive elements

have a 10-fold increased incidence of lung cancers.

Follow-up of survivors of the atomic bombs dropped on

Hiroshima and Nagasaki disclosed a markedly increased

incidence of leukemia-principally acute and chronic

myeloid leukemia-after an average latent period of about

7 years, as well as an increased mortality rate from

thyroid, breast, colon, and lung carcinomas. The nuclear

power accident at Chernobyl in the former Soviet Union

continues to exact its toll in the form of high cancer

incidence in the surrounding areas. Therapeutic irradiation

of the head and neck can give rise to papillary thyroid

cancers years later. The oncogenic properties of ionizing

radiation are related to its mutagenic effects; it causes

chromosome breakage, translocations, and, less

frequently, point mutations. Biologically, double-stranded

DNA breaks seem to be the most important form of DNA

damage caused by radiation. There is also some evidence

that nonlethal doses of radiation may induce genomic

instability, favoring carcinogenesis.

The oncogenic effect of UV rays merits special mention

because it highlights the importance of DNA repair in

carcinogenesis. Natural UV radiation derived from the sun

can cause skin cancers (melanomas, squamous cell

carcinomas, and basal cell carcinomas). At greatest risk

are fair-skinned people who live in locales such as

Australia and New Zealand that receive a great deal of

sunlight. Nonmelanoma skin cancers are associated with

total cumulative exposure to UV radiation, whereas

melanomas are associated with intense intermittent

exposure-as occurs with sunbathing. UV light has several

biologic effects on cells. Of particular relevance to

carcinogenesis is the ability to damage DNA by forming

pyrimidine dimers. This type of DNA damage is repaired

by the nucleotide excision repair pathway. With extensive

exposure to UV light, the repair systems may be

overwhelmed, and skin cancer results. As mentioned

above, patients with the inherited disease xeroderma

pigmentosum have a defect in the nucleotide excision

repair pathway. As expected, there is a greatly increased

predisposition to skin cancers in this disorder.

Viral and Microbial Oncogenesis

a- Oncogenic RNA Viruses

The study of oncogenic retroviruses in animals has

provided spectacular insights into the genetic basis of

cancer. However, human T-cell leukemia virus-1 (HTLV-

1) is the only retrovirus that has been demonstrated to

cause cancer in humans. HTLV-1 is associated with a

form of T-cell leukemia/lymphoma that is endemic in

certain parts of Japan and the Caribbean basin but is found

sporadically elsewhere, including the United States.

Similar to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV),

HTLV-1 has tropism for CD4+ T cells, and this subset of

T cells is the major target for neoplastic transformation.

Human infection requires transmission of infected T cells

via sexual intercourse, blood products, or breastfeeding.

Leukemia develops only in about 3% to 5% of infected

individuals after a long latent period of 20 to 50 years.

There is little doubt that HTLV-1 infection of T

lymphocytes is necessary for leukemogenesis, but the

molecular mechanisms of transformation are not clear.

HTLV-1 does not contain a viral oncogene, and in contrast

to certain animal retroviruses, no consistent integration site

next to a cellular oncogene has been discovered. Indeed, the

long latency period between initial infection and

development of disease suggests a multistep process, during

which many oncogenic mutations are accumulated.

The genome of HTLV-1 contains, in addition to the usual

retroviral genes, a unique region called pX. This region

encodes several genes, including one called TAX. The TAX

Unit 5: Neoplasia

93

protein has been shown to be necessary and sufficient for

cellular transformation. By interacting with several

transcription factors, such as NF-κB, the TAX protein can

transactivate the expression of genes that encode cytokines,

cytokine receptors, and costimulatory molecules. This

inappropriate gene expression leads to autocrine signaling

loops and increased activation of pro-mitogenic signaling

cascades. Furthermore, TAX can drive progression through

the cell cycle by directly binding to and activating cyclins.

In addition, TAX can repress the function of several tumor

suppressor genes that control the cell cycle, including

CDKN2A/p16 and p53. From these and other observations

the following scenario is emerging The TAX gene turns on

several cytokine genes and their receptors (IL-2 and IL-2R,

IL-15, and IL-15R), setting up an autocrine system that

drives T-cell proliferation. Of these cytokines, IL-15 seems

to be more important, but much remains to be defined.

Additionally, a parallel paracrine pathway is activated by

increased production of granulocyte-macrophage colony-

stimulating factor, which stimulates neighboring

macrophages to produce other T-cell mitogens. Initially the

T-cell proliferation is polyclonal because the virus infects

many cells, but, because of TAX-based inactivation of

tumor suppressor genes such as p53, the proliferating T

cells are at increased risk of secondary transforming events

(mutations), which lead ultimately to the outgrowth of a

monoclonal neoplastic T-cell population.

B - Oncogenic DNA Viruses

As with RNA viruses, several oncogenic DNA viruses

that cause tumors in animals have been identified. Four

DNA viruses-human papillomavirus (HPV), Epstein-Barr

virus (EBV), Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV, also

called human herpesvirus 8), and hepatitis B virus (HBV)-

are of special interest, because they are strongly

associated with human cancer

Human Papillomavirus

Scores of genetically distinct types of HPV have been

identified. Some types (e.g., 1, 2, 4, and 7) definitely cause

benign squamous papillomas (warts) in humans). By

contrast, high-risk HPVs (e.g., 16 and 18) have been

implicated in the genesis of several cancers, particularly

squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix and anogenital

region. In addition, at least 20% of oropharyngeal cancers

are associated with HPV. In contrast to cervical cancers,

genital warts have low malignant potential & are associated

with low-risk HPVs predominantly HPV-6 & HPV-11.

The oncogenic potential of HPV can be related to

products of two early viral genes, E6 and E7. Together,

they interact with a variety of growth-regulating proteins

encoded by protooncogenes and tumor suppressor genes.

The E7 protein binds to the retinoblastoma protein and

displaces the E2F transcription factors that are normally

sequestered by RB, promoting progression through the

cell cycle. Interestingly, E7 protein from high-risk HPV

types has a higher affinity for RB than does E7 from low-

risk HPV types. E7 also inactivates the CDKIs

CDKN1A/p21 and CDNK1B/p27. E7 proteins from high-

risk HPV types (types 16, 18, and 31) also bind and

presumably activate cyclins E and A. The E6 protein has

complementary effects. It binds to and mediates the

degradation of p53 and BAX, a pro-apoptotic member of

the BCL2 family, and it activates telomerase. In analogy

with E7, E6 from high-risk HPV types has a higher

affinity for p53 than E6 from low-risk HPV types.

Interestingly, in benign warts the HPV genome is

maintained in a nonintegrated episomal form, while in

cancers the HPV genome is randomly integrated into the

host genome. Integration interrupts the viral DNA,

resulting in overexpression of the oncoproteins E6 and

E7. Furthermore, cells in which the viral genome has

integrated show significantly more genomic instability.

To summarize, infection with high-risk HPV types

simulates the loss of tumor suppressor genes, activates

cyclins, inhibits apoptosis, and combats cellular

senescence. Thus, it is evident that many of the hallmarks

of cancer discussed earlier are driven by HPV proteins.

However, infection with HPV itself is not sufficient for

carcinogenesis. For example, when human keratinocytes

are transfected with DNA from HPV 16, 18, or 31 in

vitro, they are immortalized, but they do not form tumors

in experimental animals. Cotransfection with a mutated

RAS gene results in full malignant transformation. These

data strongly suggest that HPV, in all likelihood, acts in

concert with other environmental factors). However, the

primacy of HPV infection in the causation of cervical

cancer is attested to by the near complete protection from

this cancer by anti-HPV vaccines.

Epstein-Barr Virus

EBV has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several

human tumors: Burkitt lymphoma, B-cell lymphomas in

patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and

other causes of immunosuppression, a subset of Hodgkin

lymphoma, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Except for

nasopharyngeal carcinoma, all others are B-cell tumors. A

Unit 5: Neoplasia

94

subset of T-cell lymphomas and the rare NK-cell

lymphomas may also be related to EBV.

EBV has been implicated in the pathogenesis of Burkitt

lymphomas, lymphomas in immunosuppressed

individuals with HIV infection or organ transplantation,

some forms of Hodgkin lymphoma, and nasopharyngeal

carcinoma. All except the nasopharyngeal cancers are B-

cell tumors.Certain EBV gene products contribute to

oncogenesis by stimulating a normal B-cell proliferation

pathway. Concomitant compromise of immune

competence allows sustained B-cell proliferation and

eventually development of lymphoma with occurrence of

additional mutations such as t(8 ; 14), leading to

activation of the MYC gene.

Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C Viruses:-

Between 70% and 85% of hepatocellular carcinomas

worldwide are due to infection with HBV or HCV.The

oncogenic effects of HBV and HCV are multifactorial,

but the dominant effect seems to be immunologically

mediated chronic inflammation, hepatocellular injury,

stimulation of hepatocyte proliferation, and production of

reactive oxygen species that can damage DNA.The HBx

protein of HBV and the HCV core protein can activate a

variety of signal transduction pathways that may also

contribute to carcinogenesis.

Bacterial oncogene (Helicobacter pylori)

H. pylori infection has been implicated in both gastric

adenocarcinoma and MALT lymphoma.The mechanism

of H. pylori-induced gastric cancers is multifactorial

including immunologically mediated chronic

inflammation, stimulation of gastric cell proliferation &

production of reactive oxygen species that damage DNA.

H. pylori pathogenicity genes, such as CagA, may also

contribute by stimulating growth factor pathways.It is

thought that H. pylori infection leads to polyclonal B-cell

proliferations & that eventually a monoclonal B-cell

tumor (MALT lymphoma) emerges as a result of

accumulation of mutations

Host defense against tumors: tumor

immunity

Tumor Antigens

Antigens that elicit an immune response have been

demonstrated in many experimentally induced tumors & in

some human cancers. Initially, they were broadly classified

into two categories based on their patterns of expression:

tumor-specific antigens, which are present only on tumor

cells and not on any normal cells, and tumor-associated

antigens, which are present on tumor cells and also on some

normal cells. This classification, however, is imperfect,

because many antigens thought to be tumor specific turned

out to be expressed by some normal cells as well. The

modern classification of tumor antigens is based on their

molecular structure and source. An important advance in

the field of tumor immunology was the development of

techniques for identifying tumor antigens that were

recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), because

CTLs are the major immune defense mechanism against

tumors. Recall that CTLs recognize peptides derived from

cytoplasmic proteins that are displayed bound to class I

major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules

Products of Other Mutated Genes

Because of the genetic instability of tumor cells, many

genes are mutated in these cells, including genes whose

products are not related to the transformed phenotype &

have no known function. Products of these mutated genes

are potential tumor antigens. These antigens are extremely

diverse because the carcinogens that induce the tumors may

randomly mutagenize virtually any host gene. Mutated

cellular proteins are found more frequently in chemical

carcinogen- or radiation-induced animal tumors than in

spontaneous human cancers. They can be targeted by the

immune system, since there is no self-tolerance against them.

Overexpressed or Aberrantly Expressed

Cellular Proteins

Tumor antigens may be normal cellular proteins that are

abnormally expressed in tumor cells and elicit immune

responses. In a subset of human melanomas some tumor

antigens are structurally normal proteins that are produced

at low levels in normal cells and overexpressed in tumor

cells. One such antigen is tyrosinase, an enzyme involved

in melanin biosynthesis that is expressed only in normal

melanocytes and melanomas. T cells from melanoma

patients recognize peptides derived from tyrosinase,

Unit 5: Neoplasia

95

raising the possibility that tyrosinase vaccines may

stimulate such responses to melanomas; clinical trials

with these vaccines are ongoing. It may be surprising that

these patients are able to respond to a normal self-antigen.

The probable explanation is that tyrosinase is normally

produced in such small amounts and in so few cells that it

is not recognized by the immune system and fails to

induce tolerance.

Another group, the so called "cancer-testis" antigens, are

encoded by genes that are silent in all adult tissues except

the testis-hence their name. Although the protein is

present in the testis it is not expressed on the cell surface

in an antigenic form, because sperm do not express MHC

class I antigens. Thus, for all practical purposes, these

antigens are tumor specific. Prototypic of this group is the

MAGE family of genes. Although they are tumor specific,

MAGE antigens are not unique for individual tumors.

MAGE-1 is expressed on 37% of melanomas and a

variable number of lung, liver, stomach, and esophageal

carcinomas. Similar antigens called GAGE, BAGE, and

RAGE have been detected in other tumors.

Tumor Antigens Produced by Oncogenic Viruses

Some viruses are associated with cancers. Not

surprisingly, these viruses produce proteins that are

recognized as foreign by the immune system. The most

potent of these antigens are proteins produced by latent

DNA viruses; examples in humans include HPV and

EBV. There is abundant evidence that CTLs recognize

antigens of these viruses and that a competent immune

system plays a role in surveillance against virus-induced

tumors because of its ability to recognize and kill virus-

infected cells. Indeed, vaccines against HPV antigens

have been found effective in prevention of cervical

cancers in young females.

Oncofetal Antigens

Oncofetal antigens or embryonic antigens, such as

carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and α-fetoprotein, are

expressed during embryogenesis but not in normal adult

tissues. Derepression of the genes that encode these

antigens causes their reexpression in colon and liver

cancers. Antibodies can be raised against these, and they

are useful for detection of oncofetal antigens. Although,

as discussed later, they are not entirely tumor specific,

they can serve as serum markers for cancer.

Altered Cell Surface Glycolipids & Glycoproteins

Most human and experimental tumors express higher than

normal levels and/or abnormal forms of surface

glycoproteins and glycolipids, which may be diagnostic

markers and targets for therapy. These altered molecules

include gangliosides, blood group antigens, and mucins.

Although most of the epitopes recognized by antibodies

raised against such antigens are not specifically expressed

on tumors, they are present at higher levels on cancer cells

than on normal cells. This class of antigens is a target for

cancer therapy with specific antibodies.

Several mucins are of special interest and have been the

focus of diagnostic and therapeutic studies. These include

CA-125 and CA-19-9, expressed on ovarian carcinomas,

and MUC-1, expressed on breast carcinomas. Unlike

many other types of mucins, MUC-1 is an integral

membrane protein that is normally expressed only on the

apical surface of breast ductal epithelium, a site that is

relatively sequestered from the immune system. In ductal

carcinomas of the breast, however, the molecule is

expressed in an unpolarized fashion and contains new,

tumor-specific carbohydrate and peptide epitopes. These

epitopes induce both antibody and T-cell responses in

cancer patients and are therefore being considered as

candidates for tumor vaccines.

Cell Type-Specific Differentiation Antigens

Tumors express molecules that are normally present on

the cells of origin. These antigens are called

differentiation antigens, because they are specific for

particular lineages or differentiation stages of various cell

types. Their importance is as potential targets for

immunotherapy and for identifying the tissue of origin of

tumors. For example, lymphomas may be diagnosed as B-

cell-derived tumors by the detection of surface markers

characteristic of this lineage, such as CD10 and CD20.

Antibodies against these molecules are also used for

tumor immunotherapy. These differentiation antigens are

typically normal self-antigens, and therefore they do not

induce immune responses in tumor-bearing hosts.

Antitumor Effector Mechanisms

Cell-mediated immunity is the dominant anti-tumor

mechanism in vivo. Although antibodies can be made

against tumors, there is no evidence that they play a

protective role under physiologic conditions.

Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes

The role of specifically sensitized CTLs in experimentally

induced tumors is well established. In humans, they seem to

play a protective role, chiefly against virus-associated

neoplasms (e.g., EBV-induced Burkitt lymphoma and

Unit 5: Neoplasia

96

HPV-induced tumors). The presence of MHC-restricted

CD8+ cells that can kill autologous tumor cells within

human tumors suggests that the role of T cells in immunity

against human tumors may be broader than previously

suspected. In some cases, such CD8+ T cells do not

develop spontaneously in vivo but can be generated by

immunization with tumor antigen-pulsed dendritic cells.

Natural Killer Cells

NK cells are lymphocytes that are capable of destroying

tumor cells without prior sensitization; they may provide

the first line of defense against tumor cells. After

activation with IL-2, NK cells can lyse a wide range of

human tumors, including many that seem to be

nonimmunogenic for T cells. T cells and NK cells seem to

provide complementary antitumor mechanisms. Tumors

that fail to express MHC class I antigens cannot be

recognized by T cells, but these tumors may trigger NK

cells because the latter are inhibited by recognition of

normal autologous class I molecules. The triggering

receptors on NK cells are extremely diverse and belong to

several gene families. NKG2D proteins expressed on NK

cells and some T cells are important activating receptors.

They recognize stress-induced antigens that are expressed

on tumor cells and cells that have incurred DNA damage

and are at risk for neoplastic transformation.

Macrophages

Activated macrophages exhibit cytotoxicity against tumor

cells in vitro. T cells, NK cells, and macrophages may

collaborate in antitumor reactivity, because interferon-γ, a

cytokine secreted by T cells and NK cells, is a potent

activator of macrophages. Activated macrophages may

kill tumors by mechanisms similar to those used to kill

microbes or by secretion of tumor necrosis factor (TNF).

Humoral Mechanisms

Although there is no evidence for the protective effects of

anti-tumor antibodies against spontaneous tumors,

administration of monoclonal antibodies against tumor

cells can be therapeutically effective. A monoclonal

antibody against CD20, a B cell surface antigen, is widely

used for treatment of certain non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

Immune Surveillance & Immune Evasion

by Tumors

Given the host of possible and potential antitumor

mechanisms, is there any evidence that they operate in

vivo to prevent the emergence of neoplasms? The

strongest argument for the existence of immune

surveillance is the increased frequency of cancers in

immunodeficient hosts. About 5% of individuals with

congenital immunodeficiencies develop cancers, a rate

that is about 200 times that for individuals without such

immunodeficiencies. Analogously, immunosuppressed

transplant recipients and patients with acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome have increased numbers of

malignancies. It should be noted that most (but not all) of

these neoplasms are lymphomas, often lymphomas of

activated B cells. Particularly illustrative is X-linked

lymphoproliferative disorder. When affected boys develop

an EBV infection, such infection does not take the usual

self-limited form of infectious mononucleosis but instead

evolves into a chronic or sometimes fatal form of

infectious mononucleosis or, even worse, malignant

lymphoma.

Escape mechanisms of tumor from

immunosurveillance

1) Selective outgrowth of antigen-negative variants.

During tumor progression, strongly immunogenic

subclones may be eliminated

2) Loss or reduced expression of histocompatibility

molecules.

Tumor cells may fail to express normal levels of HLA

class I, escaping attack by CTLs. Such cells, however,

may trigger NK cells

3) Immunosuppression. Many oncogenic agents (e.g.,

chemicals and ionizing radiation) suppress host immune

responses. Tumors or tumor products also may be

immunosuppressive. For example, TGF-β, secreted in

large quantities by many tumors, is a potent

immunosuppressant. In some cases, the immune response

induced by the tumor may inhibit tumor immunity.

Several mechanisms of such inhibition have been

described. For instance, recognition of tumor cells may

lead to engagement of the T-cell inhibitory receptor,

CTLA-4, or activation of regulatory T cells that suppress

immune responses.

It is worth mentioning that although much of the focus in

the field of tumor immunity has been on the mechanisms

by which the host immune system defends against tumors,

there is some recent evidence that, paradoxically, the

immune system may promote the growth of tumors. It is

possible that activated lymphocytes and macrophages

produce growth factors for tumor cells. Enzymes, such as

MMPs, that enhance tumor invasion, may also be

produced. Harnessing the protective

Unit 5: Neoplasia

97

Clinical aspects of neoplasia

Ultimately the importance of neoplasms lies in their

effects on patients. Although malignant tumors are of

course more threatening than benign tumors, any tumor,

even a benign one, may cause morbidity and mortality.

Indeed, both malignant and benign tumors may cause

problems because of (1) location and impingement on

adjacent structures, (2) functional activity such as

hormone synthesis or the development of paraneoplastic

syndromes, (3) bleeding and infections when the tumor

ulcerates through adjacent surfaces, (4) symptoms that

result from rupture or infarction & (5) cachexia or wasting

Effects of Tumor on Host

Location is crucial in both benign and malignant tumors.

A small (1-cm) pituitary adenoma can compress and

destroy the surrounding normal gland and give rise to

hypopituitarism. A 0.5-cm leiomyoma in the wall of the

renal artery may lead to renal ischemia and serious

hypertension. A comparably small carcinoma within the

common bile duct may induce fatal biliary tract obstruction.

Hormone production is seen with benign and malignant

neoplasms arising in endocrine glands. Adenomas and

carcinomas arising in the β-cells of the islets of the

pancreas can produce hyperinsulinism, sometimes fatal.

Analogously, some adenomas and carcinomas of the

adrenal cortex elaborate corticosteroids that affect the

patient (e.g., aldosterone, which induces sodium retention,

hypertension, and hypokalemia). Such hormonal activity

is more likely with a well-differentiated benign tumor

than with a corresponding carcinoma.

Cancer Cachexia

Many cancer patients suffer progressive loss of body fat

and lean body mass, accompanied by profound weakness,

anorexia, and anemia, referred to as cachexia. There is

some correlation between the size and extent of spread of

the cancer and the severity of the cachexia. However,

cachexia is not caused by the nutritional demands of the

tumor. Although patients with cancer are often anorexic,

current evidence indicates that cachexia results from the

action of soluble factors such as cytokines produced by

the tumor and the host rather than reduced food intake. In

patients with cancer, calorie expenditure remains high,

and basal metabolic rate is increased, despite reduced

food intake. This is in contrast to the lower metabolic rate

that occurs as an adaptational response in starvation. The

basis of these metabolic abnormalities is not fully

understood. It is suspected that TNF produced by

macrophages in response to tumor cells or by the tumor

cells themselves mediates cachexia. TNF suppresses

appetite and inhibits the action of lipoprotein lipase,

inhibiting the release of free fatty acids from lipoproteins.

Additionally, a protein-mobilizing factor called

proteolysis-inducing factor, which causes breakdown of

skeletal muscle proteins by the ubiquitin-proteosome

pathway, has been detected in the serum of cancer

patients. Other molecules with lipolytic action also have

been found. There is no satisfactory treatment for cancer

cachexia other than removal of the underlying cause, the

tumor.

Paraneoplastic Syndromes

Symptom complexes that occur in patients with cancer

and that cannot be readily explained by local or distant

spread of the tumor or by the elaboration of hormones

indigenous to the tissue of origin of the tumor are referred

to as paraneoplastic syndromes. They appear in 10% to

15% of patients with cancer, and it is important to

recognize them for several reasons

The paraneoplastic syndromes are diverse and are

associated with many different tumors . The most common

syndromes are hypercalcemia, Cushing syndrome, and

nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis; the neoplasms most

often associated with these and other syndromes are lung

and breast cancers and hematologic malignancies.

Hypercalcemia in cancer patients is multifactorial, but the

most important mechanism is the synthesis of a parathyroid

hormone-related protein (PTHrP) by tumor cells. Also

implicated are other tumor-derived factors, such as TGF-α,

a polypeptide factor that activates osteoclasts, and the

active form of vitamin D. Another possible mechanism for

hypercalcemia is widespread osteolytic metastatic disease

of bone, but it should be noted that hypercalcemia resulting

from skeletal metastases is not a paraneoplastic syndrome.

Cushing syndrome as a paraneoplastic phenomenon is

usually related to ectopic production of ACTH or ACTH-

like polypeptides by cancer cells, as occurs in small-cell

cancers of the lung. Sometimes one tumor induces several

syndromes concurrently. For example, bronchogenic

carcinomas may elaborate products identical to or having

the effects of ACTH, antidiuretic hormone, parathyroid

hormone, serotonin, human chorionic gonadotropin, and

other bioactive substances.

Unit 5: Neoplasia

98

Grading and Staging of Cancer:-

Methods to quantify the probable clinical aggressiveness of

a given neoplasm and its apparent extent and spread in the

individual patient are necessary for making accurate

prognosis and for comparing end results of various

treatment protocols. For instance, the results of treating

extremely small, highly differentiated thyroid

adenocarcinomas that are localized to the thyroid gland are

likely to be different from those obtained from treating

highly anaplastic thyroid cancers that have invaded the

neck organs.

The grading of a cancer attempts to establish some

estimate of its aggressiveness or level of malignancy

based on the cytologic differentiation of tumor cells and

the number of mitoses within the tumor. The cancer may

be classified as grade I, II, III, or IV, in order of

increasing anaplasia. Criteria for the individual grades

vary with each form of neoplasia and so are not detailed

here. Difficulties in establishing clear-cut criteria have led

in some instances to descriptive characterizations (e.g.,

"well-differentiated adenocarcinoma with no evidence of

vascular or lymphatic invasion" or "highly anaplastic

sarcoma with extensive vascular invasion").

Staging of cancers is based on the size of the primary

lesion, its extent of spread to regional lymph nodes, and

the presence or absence of metastases. This assessment is

usually based on clinical and radiographic examination

(computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging)

and in some cases surgical exploration. Two methods of

staging are currently in use: the TNM system (T, primary

tumor; N, regional lymph node involvement; M,

metastases) and the AJC (American Joint Committee)

system. In the TNM system, T1, T2, T3, and T4 describe

the increasing size of the primary lesion; N0, N1, N2, and

N3 indicate progressively advancing node involvement;

and M0 and M1 reflect the absence or presence of distant

metastases. In the AJC method, the cancers are divided

into stages 0 to IV, incorporating the size of primary

lesions and the presence of nodal spread and of distant

metastases. Examples of the application of these two

staging systems are cited in subsequent chapters. It is

worth noting that when compared with grading, staging

has proved to be of greater clinical value.

Unit 5: Neoplasia

99

Laboratory Diagnosis of Cancer

Unit 5: Neoplasia

100