48

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

49

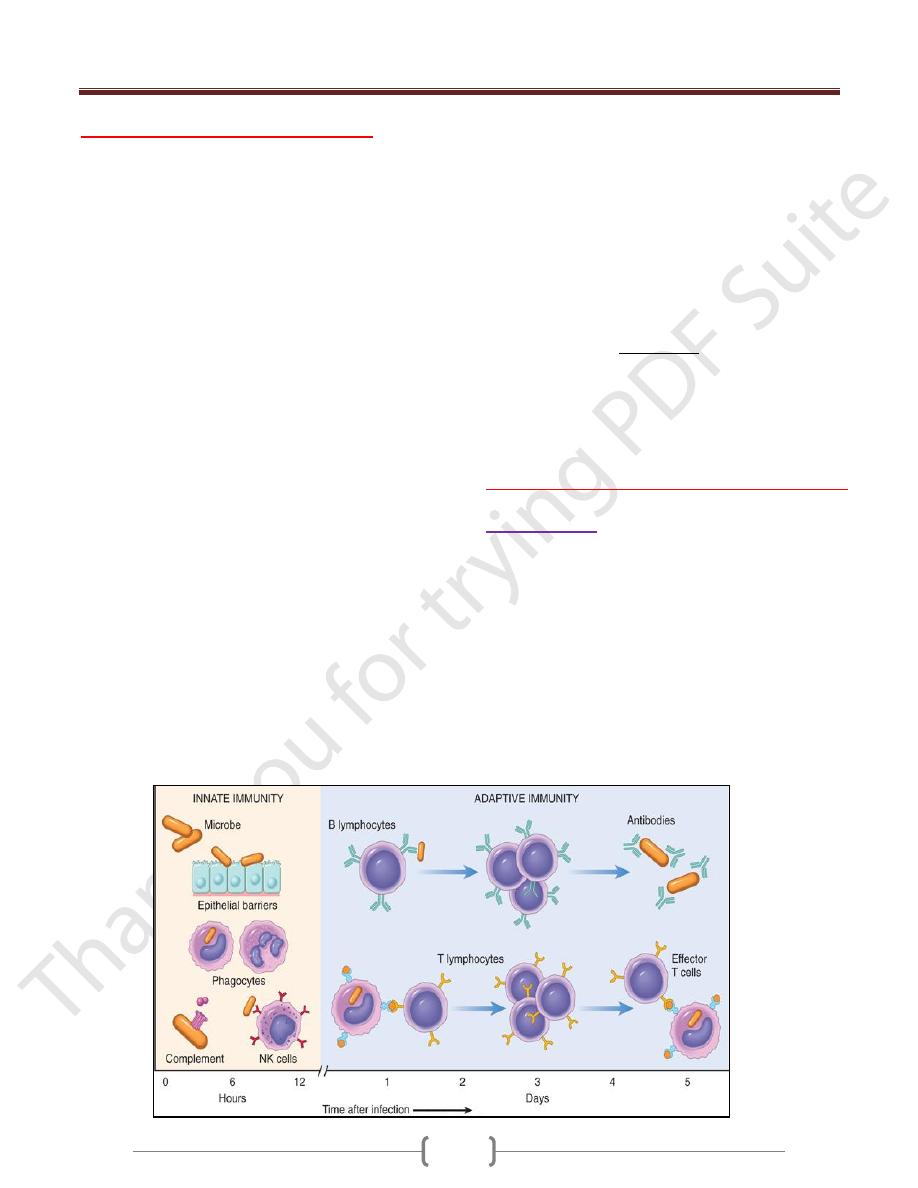

Innate and adaptive immunity

Defense against microbes consists of 2 types of reactions.

Innate immunity (also called natural, or native, immunity)

is mediated by cells and proteins that are always present

& fight against microbes & action immediately in

response to infection

The major components of innate immunity are:

epithelial barriers of the skin,

gastrointestinal tract,

respiratory tract, which prevent microbe entry

phagocytic leukocytes (neutrophils and macrophages);

natural killer (NK) cell;

Several circulating plasma proteins, the most important

of which are the proteins of the complement system.

However, many pathogenic microbes have evolved to

overcome innate immune defenses, and protection against

these infections requires the more powerful mechanisms

of adaptive immunity (also called acquired, or specific,

immunity).

Adaptive immunity is normally silent and "adapts” to the

presence of infectious microbes by becoming active,

expanding, and generating potent mechanisms for

neutralizing and eliminating the microbes.

The components of the adaptive immune system are

lymphocytes and their products.

There are two types of adaptive immune responses:

humoral immunity, mediated by soluble antibody proteins

that are produced by B lymphocytes (also called B cells

cell-mediated (or cellular) immunity, mediated by T

lymphocytes (also called T cells)

Antibodies provide protection against extracellular

microbes in the blood, mucosal secretions, and tissues.

T lymphocytes are important in defense against

intracellular microbes.

They work by either directly killing infected cells

(accomplished by cytotoxic T lymphocytes) or by

activating phagocytes to kill ingested microbes, via the

production of soluble protein mediators called cytokines

(made by helper T cells).

When the immune system is inappropriately triggered or

not properly controlled, the same mechanisms that are

involved in host defense cause tissue injury and disease.

The reaction of the cells of innate and adaptive immunity

may be manifested as inflammation.

Inflammation is a beneficial process, but it is also the

basis of many human diseases.

Cells & Tissues of the Immune System

Lymphocytes

Lymphocytes: are present in the circulation and in various

lymphoid organs.

T lymphocytes are so called because they mature in the

thymus, whereas B lymphocytes mature in the bone

marrow.

They are recognizing tens or hundreds of millions of

antigens. This enormous diversity of antigen recognition

is generated by the somatic rearrangement of antigen

receptor genes during lymphocyte maturation, and

variations that are introduced during the joining of

different gene segments to form antigen receptors

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

50

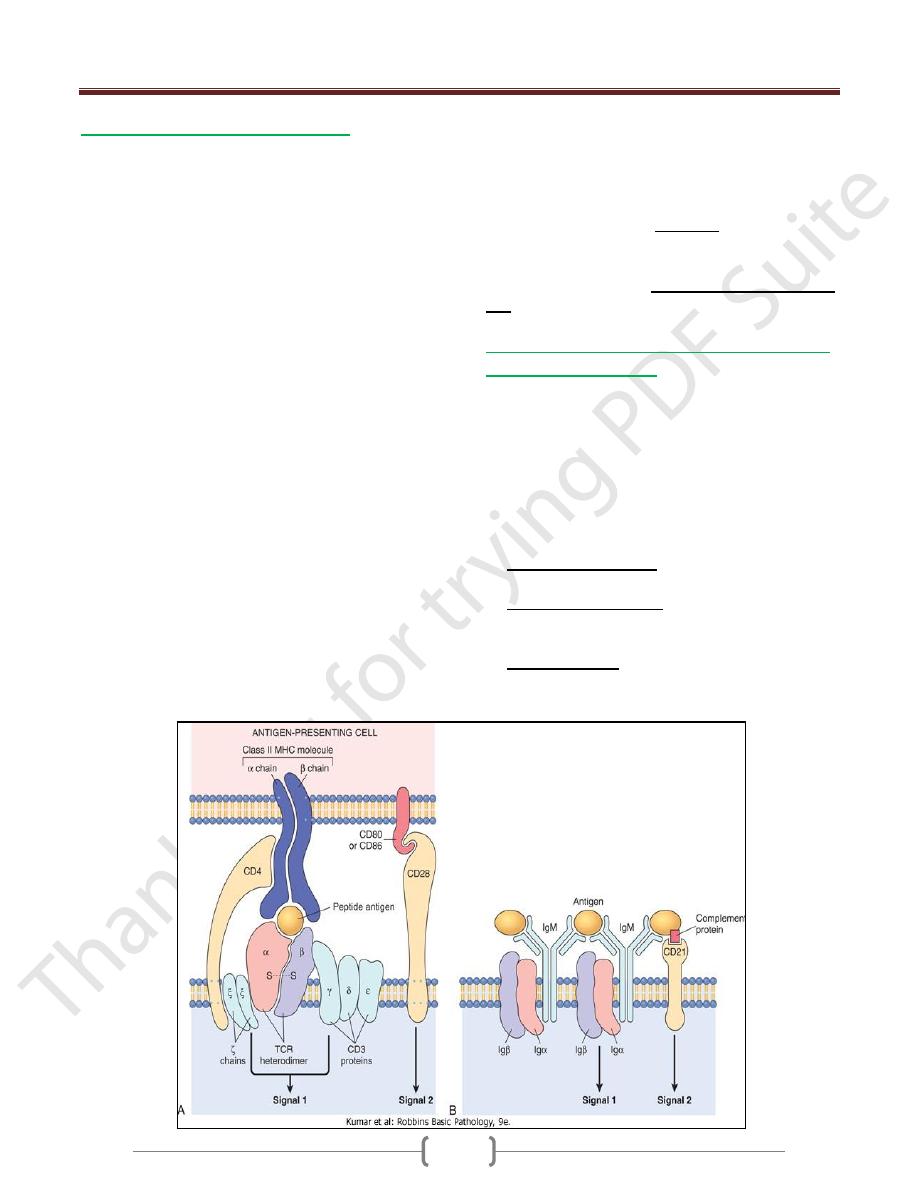

1- T (thymus-derived) lymphocytes

Express Ag receptors called T cell receptors (TCRs) that

recognize peptide fragments of protein antigens that are

displayed by MHC molecules on the surface of antigen-

presenting cells.

T cells recognize only peptide fragments of protein

antigens that are displayed on other cells bound to

proteins of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC;

or in humans, human leukocyte antigen [HLA] complex

the normal function of MHC molecules is to display

peptides for recognition by T lymphocytes.

In every individual, T cells recognize only peptides

displayed by that individual's MHC molecules, which, of

course, are the only MHC molecules that the T cells will

encounter normally. This phenomenon is called MHC

restriction.

TCRs are noncovalently linked to a cluster of five

invariant polypeptide chains, the γ, δ, and ε proteins of the

CD3 molecular complex and two ζ chains

T cells express a number of other invariant function-

associated molecules. CD4 & CD8 are expressed on distinct

T-cell subsets & serve as coreceptors for T-cell activation

CD4+ T cells are "helper" T cells because they secrete

soluble molecules (cytokines) that help B cells to produce

antibodies (the origin of the name "helper" cells) and also

help macrophages to destroy phagocytosed microbes.

CD8+ T cells can also secrete cytokines, but they play a

more important role in directly killing virus-infected or

tumor cells, and hence are called "cytotoxic" T

lymphocytes (CTLs). Other important invariant proteins

on T cells include CD28, which functions as the receptor

for molecules that are induced on APCs by microbes (and

are called costimulators),

Another small population of T cells expresses markers of

T cells and NK cells. These NKT cells recognize

microbial glycolipids

Another populations of T cells that functions to suppress

immune response is that of regulatory T lymphocytes (T

reg)

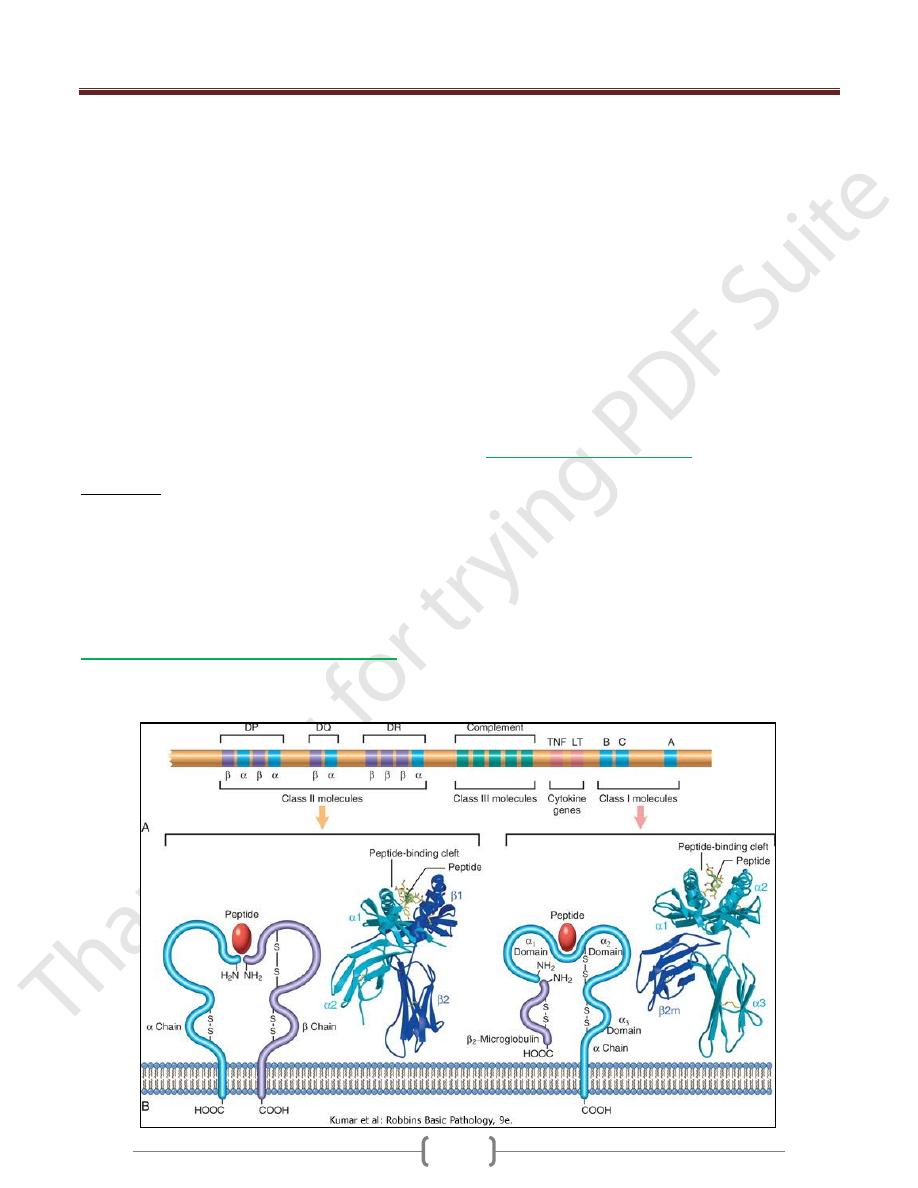

MHC Molecules: the Peptide Display System

of Adaptive Immunity

The human MHC, known as the human leukocyte antigen

(HLA) complex, consists of a cluster of genes on chrom. 6

The HLA system is highly polymorphic

this polymorphism also constitutes a formidable barrier to

organ transplantation

On the basis of their chemical structure, tissue

distribution, and function, MHC gene products fall into

three categories:

Class I MHC molecules are encoded by three closely

linked loci, designated HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C

Class II MHC molecules are encoded by genes in the

HLA-D region, which contains at least three

subregions: DP, DQ, and DR.

Class III proteins include some of the complement

components (C2, C3, and Bf); genes encoding tumor

necrosis factor (TNF) and lymphotoxin (LT)

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

51

Different MHC alleles bind to different peptide fragments

depending on the particular amino acid sequence of a

given peptide; the expression of many different MHC

molecules allows each cell to present a wide array of

peptide antigens.

The role of the MHC in T-cell stimulation also has

important implications for the genetic control of immune

responses.

The ability of any given MHC allele to bind the peptide

antigens generated from a particular pathogen will

determine whether an individual's T cells can actually

"see" and respond to that pathogen.

An individual will recognize and mount an immune

response against a given antigen only if he or she inherits

MHC molecules that can bind the antigenic peptide and

present it to T cells.

The inheritance of particular alleles influences both

protective and harmful immune responses.

For example, if the antigen is pollen and the response is

an allergic reaction,

Inheritance of some HLA genes may make individuals

susceptible to this disease.

On the other hand, good responsiveness to a viral antigen,

determined by inheritance of certain HLA alleles, may be

beneficial for the host.

2- B (bone marrow-derived) lymphocytes

Express membrane-bound antibodies that recognize a

wide variety of antigens.

B cells are activated to become plasma cells, which

secrete antibodies.

They are also present in bone marrow and in the follicles

of peripheral lymphoid tissues (lymph nodes, spleen,

tonsils, and other mucosal tissues).

B cells express several invariant molecules that are

responsible for signal transduction & for activation of the

cells.

These molecules include the CD40 receptor, which binds

to its ligand expressed on helper T cells, and CD21 (also

known as the CR2 complement receptor), which

recognizes a complement breakdown product that is

frequently deposited on microbes

EBV use CD21 as a receptor for the binding to B cell and

infecting them

3- Natural killer (NK) cells

Kill cells that are infected by some microbes.

It has 2 types of receptors: activating & inhibitory receptors

To avoid attacking normal host cells, NK cells express

inhibitory receptors that recognize self class I MHC

molecules, which are expressed on all healthy cells;

engagement of these inhibitory receptors typically

overrides the activating receptors and thus prevents

activation of the NK cells.

NK cells express inhibitory receptors that recognize MHC

molecules that are normally expressed on healthy cells,

and are thus prevented from killing normal cells.

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

52

Antigen-presenting cells (APCs)

Capture microbes and other antigens, transport them to

lymphoid organs, and display them for recognition by

lymphocytes.

The most efficient APCs are:

Dendritic cells,

Cells with dendritic morphology (i.e., with fine dendritic

cytoplasmic processes) occur as two functionally distinct

types.

Interdigitating DCs, or more simply, DCs, are

nonphagocytic cells that express high levels of class II

MHC and T-cell costimulatory molecules

It is live in and under epithelia in most tissues.

1) One subset of DC is called Plasmacytoid DCs because of

their resemblance to plasma cells

They present in the blood and lymphoid organs

They are major source of antiviral cytokines type I

interferon produce to many viruses

2) The second type of DCs is called follicular dendritic

cells (FDCs). They are located in the germinal centers of

lymphoid follicles in the spleen and lymph nodes. These

cells bear receptors for the Fc tails of IgG and for

complement proteins, and hence efficiently trap antigen

bound to antibodies and complement. These cells display

antigens to activated B lymphocytes in lymphoid follicles

and promote secondary antibody responses.

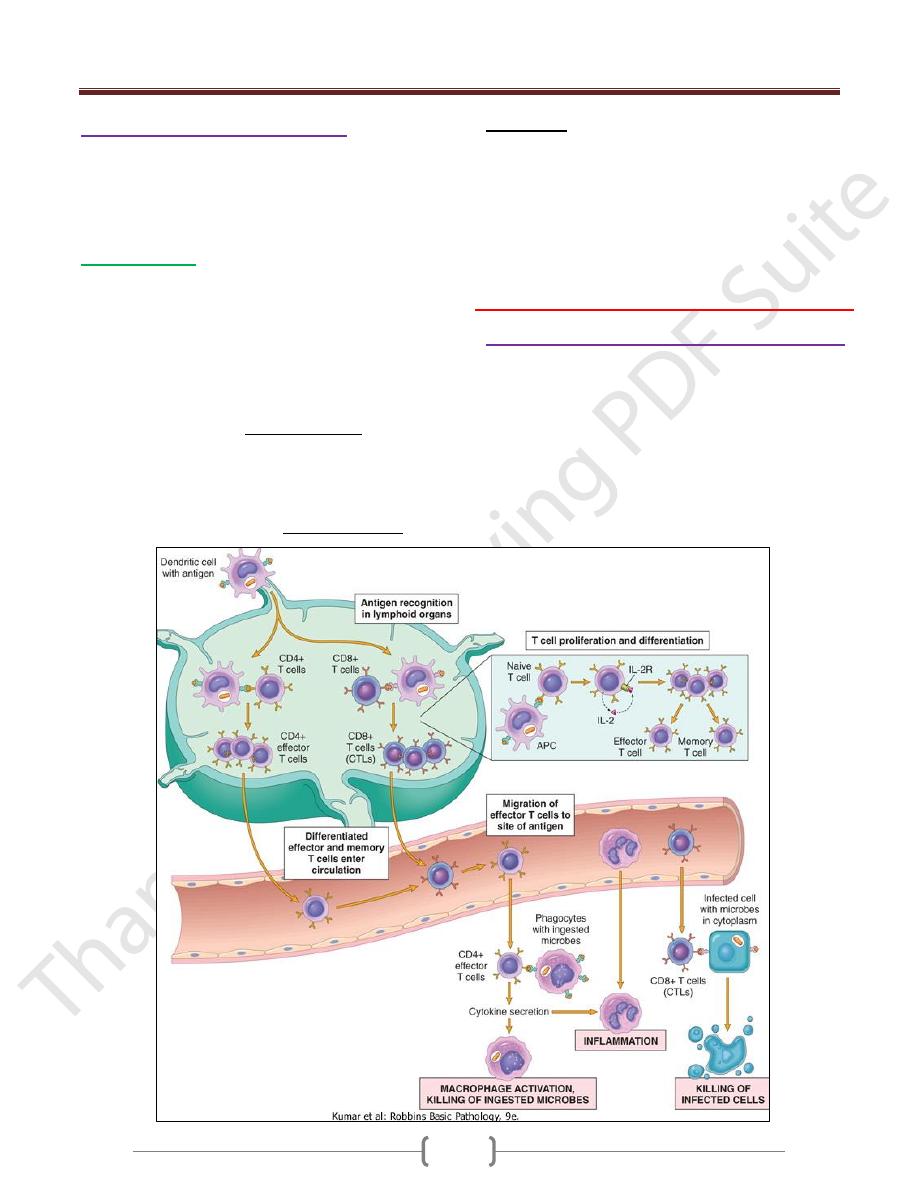

Overview of normal immune responses

The early innate immune response to microbes

The physiologic function of the immune system is defense

against infectious microbes. The early reaction to microbes

is mediated by the mechanisms of innate immunity, which

are ready to respond to microbes. These mechanisms

include epithelial barriers, phagocytes, NK cells, and

plasma proteins, e.g., of the complement system.

The reaction of innate immunity is often manifested as

inflammation.

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

53

The Capture & Display of Microbial Antigens

The defense reactions of adaptive immunity develop

slowly, but are more potent and specialized.

Microbes and other foreign antigens are captured by

dendritic cells and transported to lymph nodes, where the

antigens are recognized by naïve lymphocytes.

The lymphocytes are activated to proliferate and

differentiate into effector and memory cells.

Cell-Mediated Immunity: Activation of T

Lymphocytes & Elimination of Cell-

Associated Microbes

Cell-mediated immunity is the reaction of T lymphocytes,

designed to combat cell-associated microbes (e.g.,

phagocytized microbes and microbes in the cytoplasm of

infected cells).

Humoral immunity is mediated by antibodies and is

effective against extracellular microbes (in the circulation

and mucosal lumens).

Cells neutralize microbes and block their infectivity, and

promote the Antibodies secreted by plasma phagocytosis

and destruction of pathogens. Antibodies also confer

passive immunity to neonates.

CD4+ helper T cells help B cells to make antibodies,

activate macrophages to destroy ingested microbes, and

regulate all immune responses to protein antigens. The

functions of CD4+ T cells are mediated by secreted

proteins called cytokines.

CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes kill cells that express

antigens in the cytoplasm that are seen as foreign (e.g.

virus-infected and tumor cells).

Cytokines

Are Messenger Molecules of the Immune System Body”

Cytokines are polypeptide products of many cell types

(but principally activated lymphocytes and macrophages)

that function as mediators of inflammation and immune

responses

Although different cytokines have diverse actions and

functions, they all share some common features.

Cytokines are synthesized and secreted in response to

external stimuli, which may be microbial products,

antigen recognition, and other cytokines.

Their secretion is typically transient and is controlled by

transcription and post-translational mechanisms.

The actions of cytokines may be

autocrine (on the cell that produces the cytokine),

paracrine (on adjacent cells), and, less commonly,

Endocrine (at a distance from the site of production).

The effects of cytokines tend to be

Pleiotropic (one cytokine has effects on many cell types)

Redundant (the same activity may be induced by many

proteins).

Cytokines may be grouped into several classes based

on their biologic activities and functions.

1) Cytokines involved in innate immunity and

inflammation (IL-1,IL-12,IL-6. IL-23.IFN TNF)

2) Cytokines that regulate lymphocyte responses and

effector functions in adaptive immunity(IL-2, IL-4)

3) Cytokines that stimulate hematopoiesis. Many of these

are called colony-stimulating factors

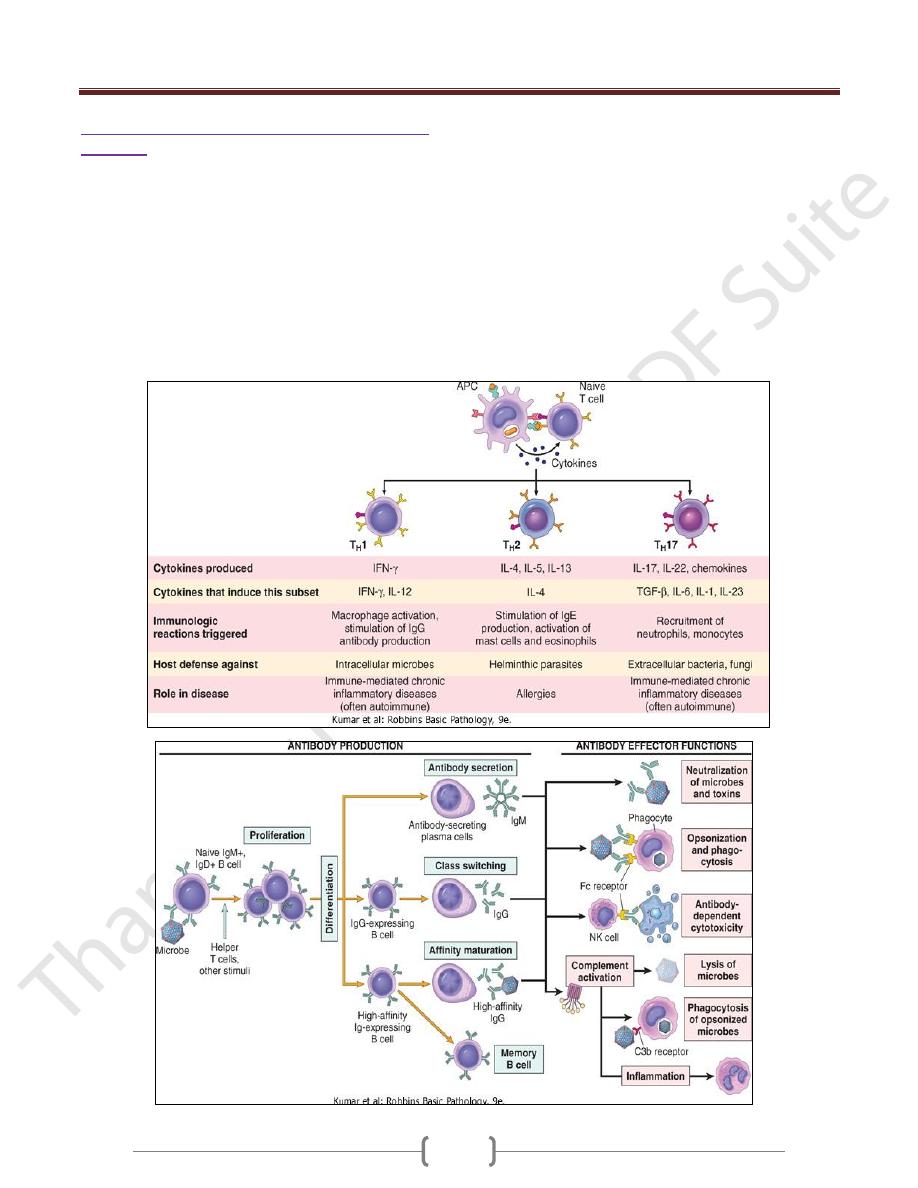

Effector Functions of T Lymphocytes

The best defined subsets of CD4+ helper cells are the T

H

1

and T

H

2 and TH17subsets

One of the earliest responses of CD4+ helper T cells is

secretion of the cytokine IL-2 and expression of high-

affinity receptors for IL-2. IL-2 is a growth factor that acts

on these T lymphocytes and stimulates their proliferation,

leading to an increase in the number of antigen-specific

lymphocytes.

A third subset, called T

H

17, has been described recently

that produces the cytokine IL-17, which promotes

inflammation, and is believed to play an important role in

some T cell-mediated inflammatory disorders.

These effector cells migrate to sites of infection and

accompanying tissue damage.

When the differentiated effectors again encounter cell-

associated microbes, they are activated to perform the

functions that are responsible for elimination of the

microbes.

The key mediators of the functions of helper T cells are

the surface molecule called CD40 ligand (CD40L), which

binds to its receptor, CD40, on B cells and macrophages,

Humoral immunity: activation of B lymphocytes

& elimination of extracellular microbes

Upon activation, B lymphocytes proliferate and then

differentiate into plasma cells that secrete different classes

of antibodies with distinct functions

B cells can also act as APCs, i.e. ingest protein antigens,

degrade them, and display peptides bound to class II

MHC molecules for recognition by helper T cells. The

helper T cells express CD40L and secrete cytokines,

which work together to activate the B cells.

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

54

Decline of immune responses & Immunologic

Memory

The majority of effector lymphocytes induced by an

infectious pathogen die by apoptosis after the microbe is

eliminated, thus returning the immune system to its basal

resting state.

This return to a stable or steady state is called homeostasis.

It occurs because microbes provide essential stimuli for

lymphocyte survival and activation and effector cells are

short-lived.

Therefore, as the stimuli are eliminated, the activated

lymphocytes are no longer kept alive

The initial activation of lymphocytes also generates long-

lived memory cells, which may survive for years after the

infection.

Memory cells are an expanded pool of antigen-specific

lymphocytes (more numerous than the naive cells specific

for any antigen that are present before encounter with that

antigen), and memory cells respond faster and more

effectively against the antigen than do naive cells. This is

why the generation of memory cells is an important goal

of vaccination.

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

55

Hypersensitivity reactions:

mechanisms of immune-mediated

injury

Immune responses are capable of causing tissue injury

and diseases that are called hypersensitivity diseases.

This term originated from the idea that individuals who

mount immune responses against an antigen are said to be

"sensitized" to that antigen, and therefore, pathologic or

excessive reactions are manifestations of "hypersensitivity

Normally, an immune system of checks and eradicate the

infecting organisms without serious injury to host tissues.

However, immune responses may be inadequately

controlled or inappropriately targeted to host tissues, and

in these situations, the normally beneficial response is the

cause of disease.

Causes of Hypersensitivity Diseases

Pathologic immune responses may be directed against

different types of antigens, and may result from various

underlying abnormalities:

1) Autoimmunity

Normally, the immune system does not react against an

individual's own antigens. This phenomenon is called self-

tolerance, implying that all of us "tolerate" our own

antigens. Sometimes, self-tolerance fails, resulting in

reactions against one's own cells and tissues that are

called autoimmunity.

2) Reactions against microbial antigens

that may cause disease. In some cases, the reaction

appears to be excessive or the microbial antigen is

unusually persistent.

If antibodies are produced against such antigens, the

antibodies may bind to the microbial antigens to produce

immune complexes, which deposit in tissues and trigger

inflammation; this is the underlying mechanism of

poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis

T-cell responses against persistent microbes may give rise

to severe inflammation, sometimes with the formation of

granulomas this is the cause of tissue injury in

tuberculosis and other infections.

Rarely, antibodies or T cells reactive with a microbe

cross-react with a host tissue; this is believed to be the

basis of rheumatic heart disease

3) Reactions against environmental antigens.

Most healthy individuals do not react strongly against

common environmental substances (e.g., pollens, animal

danders, or dust mites), but almost 20% of the population is

"allergic" to these substances

Allergies are diseases caused by unusual immune responses

to a variety of noninfectious,

Types of Hypersensitivity Diseases

Hypersensitivity reactions are traditionally subdivided

into four types; three are variations on antibody-mediated

injury, whereas the fourth is cell mediated

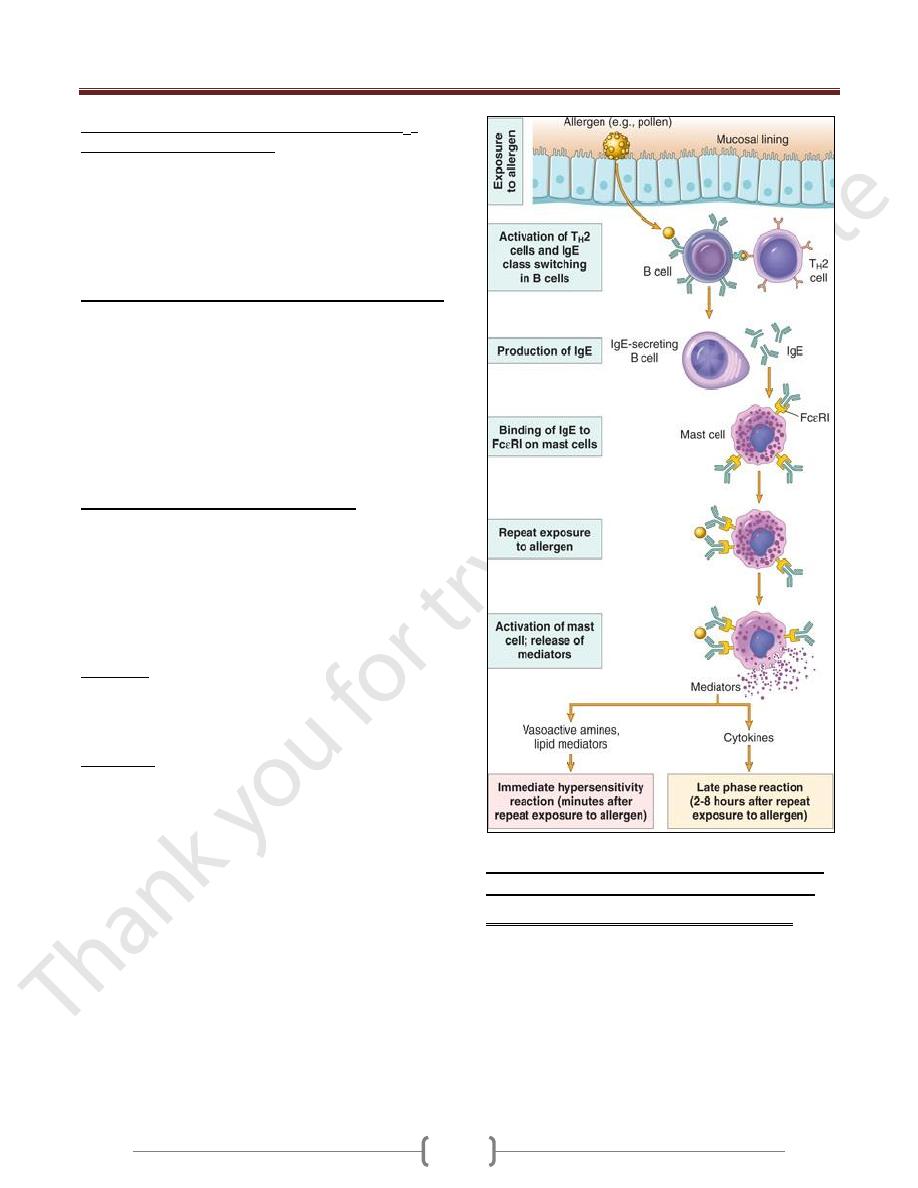

Immediate (Type I) Hypersensitivity

Often called allergy,

Results from the activation of the T

H

2 subset of CD4+

helper T cells by environmental antigens, leading to the

production of IgE antibodies, which become attached to

mast cells.

When these IgE molecules bind the antigen (allergen), the

mast cells are triggered to release mediators that transiently

affect vascular permeability & induce smooth muscle

contraction in various organs & that also may stimulate more

prolonged inflammation (the late-phase reaction). These

diseases are commonly called allergic, or atopic, disorders.

This type is a tissue reaction that occurs rapidly (typically

within minutes) after the interaction of antigen with IgE

antibody that is bound to the surface of mast cells in a

sensitized host.

The reaction is initiated by entry of an antigen, which is

called an allergen because it triggers allergy.

Many allergens are environmental substances that are

harmless for most persons on exposure.

Some people apparently inherit genes that make them

susceptible to allergies.

This susceptibility is manifested by the ability of such

persons to mount strong T

H

2 responses and, subsequently,

to produce IgE antibody against the allergens.

The IgE is central to the activation of the mast cells and

release of mediators that are responsible for the clinical

and pathologic manifestations of the reaction.

Immediate hypersensitivity may occur as a local reaction

that is merely annoying (e.g., seasonal rhinitis or hay fever),

severely debilitating (asthma), or even fatal (anaphylaxis).

Sequence of Events in Immediate Hypersensitivity

Reactions

Most hypersensitivity reactions follow the same

sequence of cellular responses:

Activation of T

H

2 cells and production of IgE antibody.

Allergens may be introduced by inhalation, ingestion,

or injection.

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

56

Variables that probably contribute to the strong T

H

2

responses to allergens include:

The route of entry,

dose,

chronicity of antigen exposure,

The genetic makeup of the host.

Structural properties that endow them with the ability

to elicit T

H

2 responses.

The TH2 cells that are induced secrete several cytokines:

IL-4 stimulates B cells specific for the allergen to undergo

heavy-chain class switching to IgE and to secrete this

immunoglobulin isotype.

IL-5 activates eosinophils that are recruited to the reaction,

IL-13 acts on epithelial cells & stimulates mucus secretion.

TH2 cells often are recruited to the site of allergic reactions

in response to chemokines that are produced locally

Chemokines is eotaxin, which also recruits eosinophils to

the same site.

Sensitization of mast cells by IgE antibody.

Mast cells are derived from precursors in the bone marrow,

are widely distributed in tissues, and often reside near blood

vessels and nerves and in subepithelial locations.

Mast cells express a high-affinity receptor for the Fc

portion of the Ε heavy chain of IgE, called FcΕRI.

These antibody-bearing mast cells are "sensitized" to react

if the antigen binds to the antibody molecules.

Basophiles

They also express FcΕRI, but their role in most immediate

hypersensitivity reactions is not established (since these

reactions occur in tissues and not in the circulation).

Eosinophils

The third cell type that expresses FcΕRI , which often are

present in these reactions and also have a role in IgE-

mediated host defense against helminth infections,

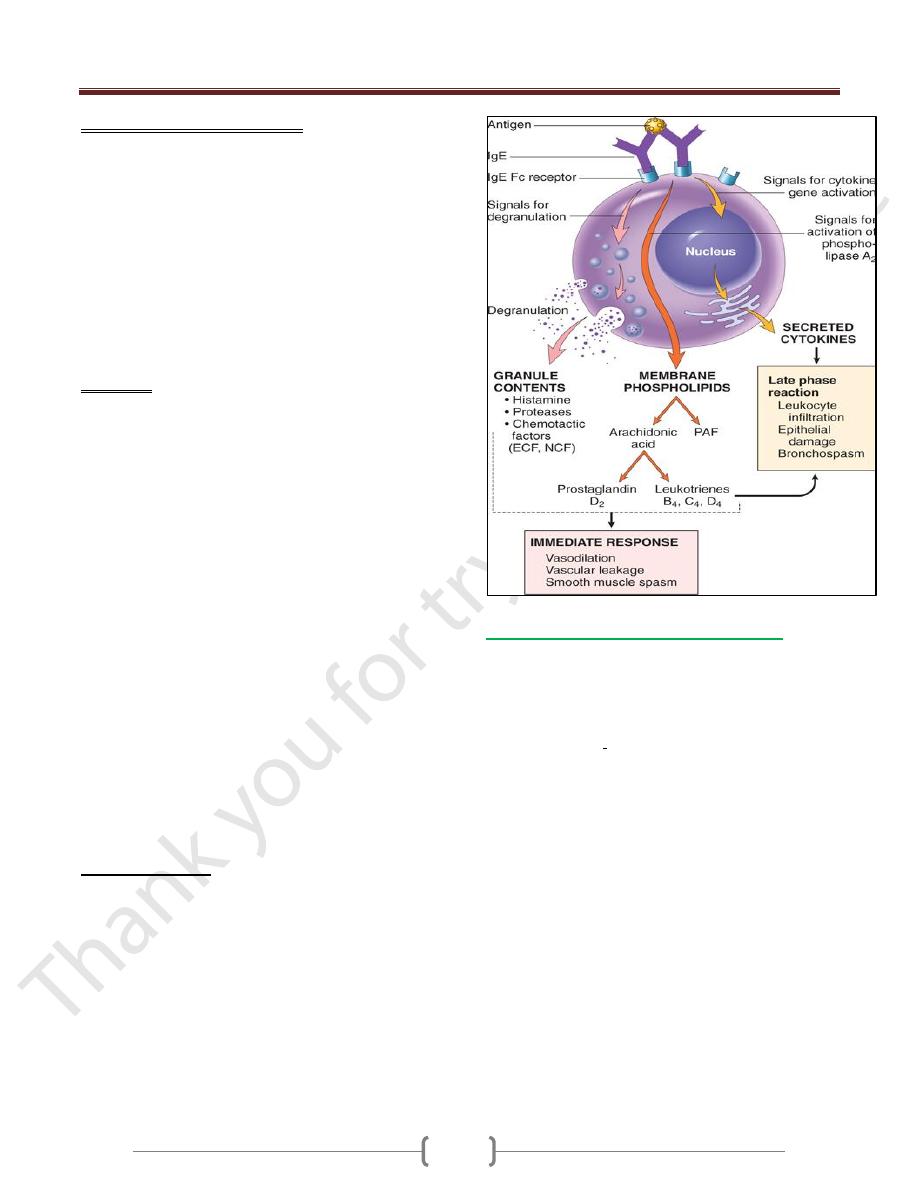

Activation of mast cells and release of mediators. When a

person who was sensitized by exposure to an allergen is

reexposed to the allergen, it binds to multiple specific IgE

molecules on mast cells, usually at or near the site of

allergen entry.

When these IgE molecules are cross-linked, a series of

biochemical signals is triggered in the mast cells. The

signals culminate in the secretion of various mediators

from the mast cells.

3 groups of mediators are the most important in

different immediate hypersensitivity reactions:

1) Vasoactive amines released from granule stores.

The granules of mast cells contain

a) Histamine, which is released within seconds or

minutes of activation. Histamine causes vasodilation,

increased vascular permeability, smooth muscle

contraction, and increased secretion of mucus.

b) 2-neutral proteases (e.g., tryptase), which may damage

tissues and also generate kinins and cleave

complement components to produce additional

chemotactic and inflammatory factors (e.g., C3a)

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

57

2) Newly synthesized lipid mediators.

Mast cells synthesize and secrete prostaglandins and

leukotrienes,

These lipid mediators have several actions that are

important in immediate hypersensitivity reactions.

a) Prostaglandin D

2

(PGD

2

) is the most abundant mediator

generated by the cyclooxygenase pathway in mast cells. It

causes intense bronchospasm as well as increased mucus

secretion.

b) The leukotrienes LTC

4

and LTD

4

are the most potent

vasoactive and spasmogenic agents known; LTB

4

is

highly chemotactic for neutrophils, eosinophils, and

monocytes.

3) Cytokines.

Activation of mast cells results in the synthesis and

secretion of several cytokines that are important for the

late-phase reaction. These include TNF and chemokines,

which recruit and activate leukocytes

IL-4 and IL-5, which amplify the T

H

2-initiated immune

reaction; and IL-13, which stimulates epithelial cell

mucus secretion.

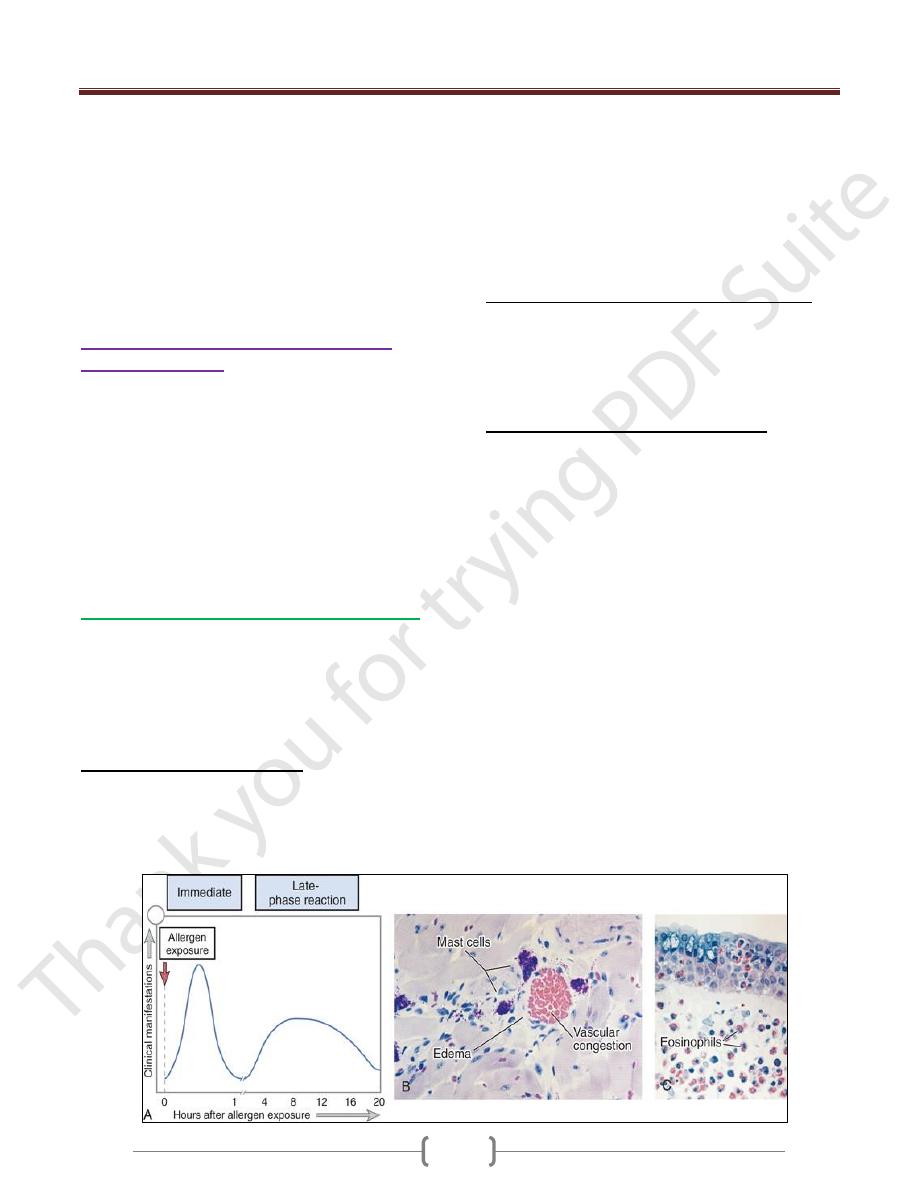

Often, the IgE-triggered reaction has 2 well-defined phases:

a) The immediate response, characterized by vasodilation,

vascular leakage, and smooth muscle spasm, usually

evident within 5 to 30 minutes after exposure to an

allergen and subsiding by 60 minutes;

b) a second, late-phase reaction

that usually sets in 2 to 8 hours later and may last for

several days

Characterized by inflammation as well as tissue

destruction, such as mucosal epithelial cell damage.

The dominant inflammatory cells in the late-phase

reaction are neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes,

especially T

H

2 cells.

Eosinophils are recruited by eotaxin and other

chemokines

Eosinophils produce

1) major basic protein

2) Eosinophil cationic protein, which are toxic to epithelial

cells

3) LTC

4

4) Platelet-activating factor, which promote inflammation.

T

H

2 cells produce cytokines

Because inflammation is a major component of many

allergic diseases, notably asthma and atopic dermatitis,

therapy usually includes anti-inflammatory drugs such as

corticosteroids.

Clinical and Pathologic Manifestations

An immediate hypersensitivity reaction occurs as a

systemic disorder or as a local reaction.

The nature of the reaction is often determined by the route

of antigen exposure.

Systemic exposure to protein antigens (e.g., in bee

venom) or drugs (e.g., penicillin) may result in systemic

anaphylaxis. urticaria (hives), and skin erythema appear,

followed in short order by profound respiratory difficulty

caused by pulmonary bronchoconstriction and

accentuated by hypersecretion of mucus. the musculature

of the entire gastrointestinal tract may be affected, with

resultant vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea.

(Anaphylactic shock), and the patient may progress to

circulatory collapse and death within minutes.

Local reactions generally occur when the antigen is

confined to a particular site, such as:

Skin (contact, causing urticaria),

Gastrointestinal tract (ingestion, causing diarrhea),

Lung (inhalation, causing bronchoconstriction).

Nose, (inhalation)hay fever,

Patients who suffer from allergy often have a family

history of similar conditions.

Genes involved in:

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

58

encoding HLA molecules

cytokines (which may control T

H

2 responses),

a component of the FcΕRI,

The immune response dependent on T

H

2 cells and IgE-in

particular, the late-phase inflammatory reaction-plays an

important protective role in combating parasitic infections.

IgE antibodies are produced in response to many

helminthic infections, and their physiologic function is to

target helminths for destruction by eosinophils & mast cells

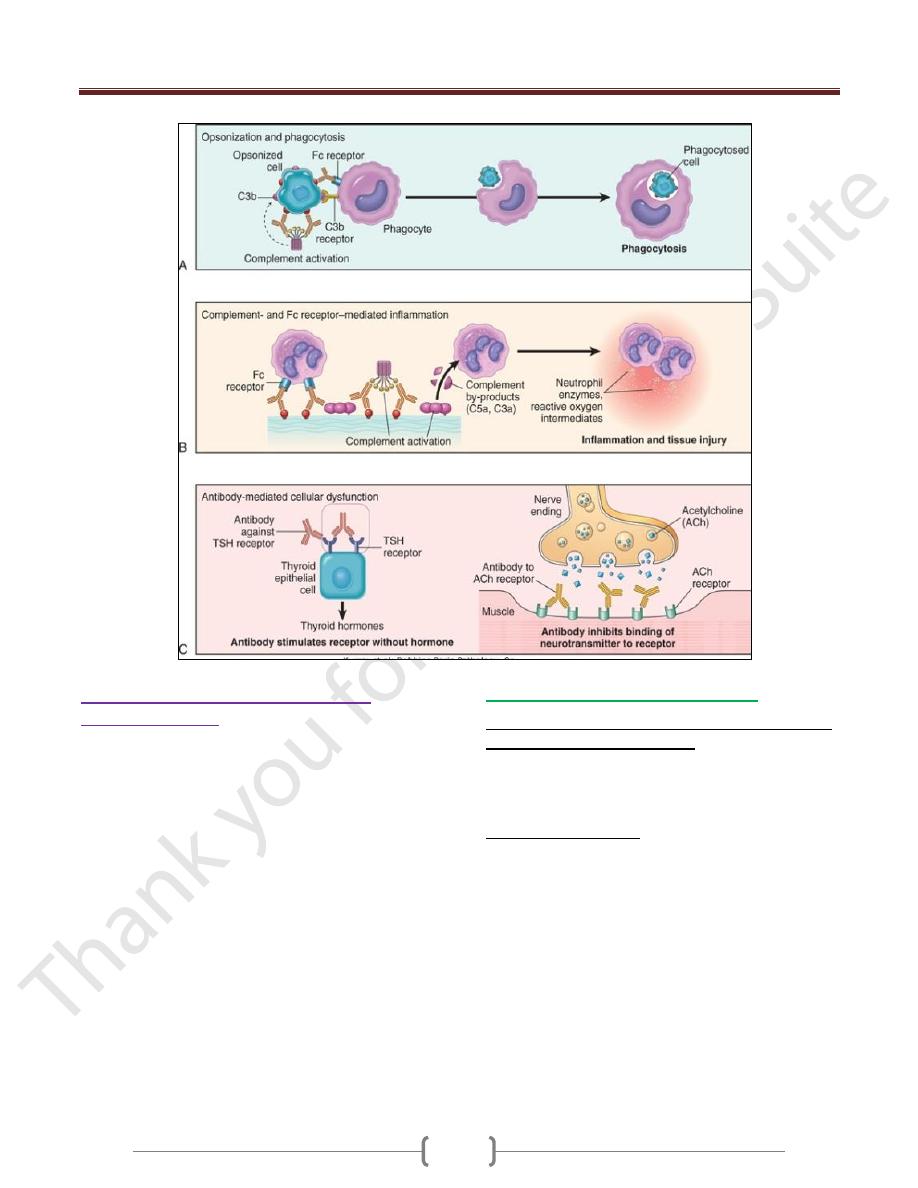

Antibody-Mediated Diseases (Type II

Hypersensitivity)

Antibody-mediated (type II) hypersensitivity disorders are

caused by

Antibodies that bind to fixed tissue or cell surface antigens,

promoting phagocytosis and destruction of the coated cells

or triggering pathologic inflammation in tissues.

Antibodies directed against: target antigens on the surface

of cells or other tissue components. The antigens may be

normal molecules intrinsic to cell membranes or in the

extracellular matrix, they may be adsorbed exogenous

antigens (e.g., a drug metabolite).

Mechanisms of Antibody-Mediated Diseases

Antibodies cause disease by targeting cells for

phagocytosis, and by interfering with normal cellular

functions

The antibodies that are responsible typically are high-

affinity antibodies capable of activating complement and

binding to the Fc receptors of phagocytes.

1) Opsonization and phagocytosis.

When circulating cells, such as erythrocytes or platelets,

are coated (opsonized) with autoantibodies, with or

without complement proteins, the cells become targets for

phagocytosis by neutrophils and macrophages

These phagocytes express receptors for the Fc tails of IgG

antibodies and for breakdown products of the C3

complement protein, and use these receptors to bind and

ingest opsonized particles.

Opsonized cells are usually eliminated in the spleen, and

this is why splenectomy is of clinical benefit in

autoimmune thrombocytopenia and some forms of

autoimmune hemolytic anemia

2)

Antibodies bound to cellular or tissue antigens

activate the complement system by the "classical"

pathway end with inflammation

Products of complement activation serve several functions

of which is to recruit neutrophils and monocytes,

triggering inflammation in tissues.

3) Antibody-mediated cellular dysfunction.

In some cases, antibodies directed against cell surface

receptors impair or dysregulate cellular function without

causing cell injury or inflammation.

In myasthenia gravis, antibodies against acetylcholine

receptors in the motor end plates of skeletal muscles inhibit

neuromuscular transmission, with resultant muscle weakness.

In Graves disease, Abs against the thyroid-stimulating

hormone receptor stimulate thyroid epithelial cells to

secrete thyroid hormones, resulting in hyperthyroidism.

Antibodies against hormones and other essential proteins

can neutralize and block the actions of these molecules,

causing functional derangements

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

59

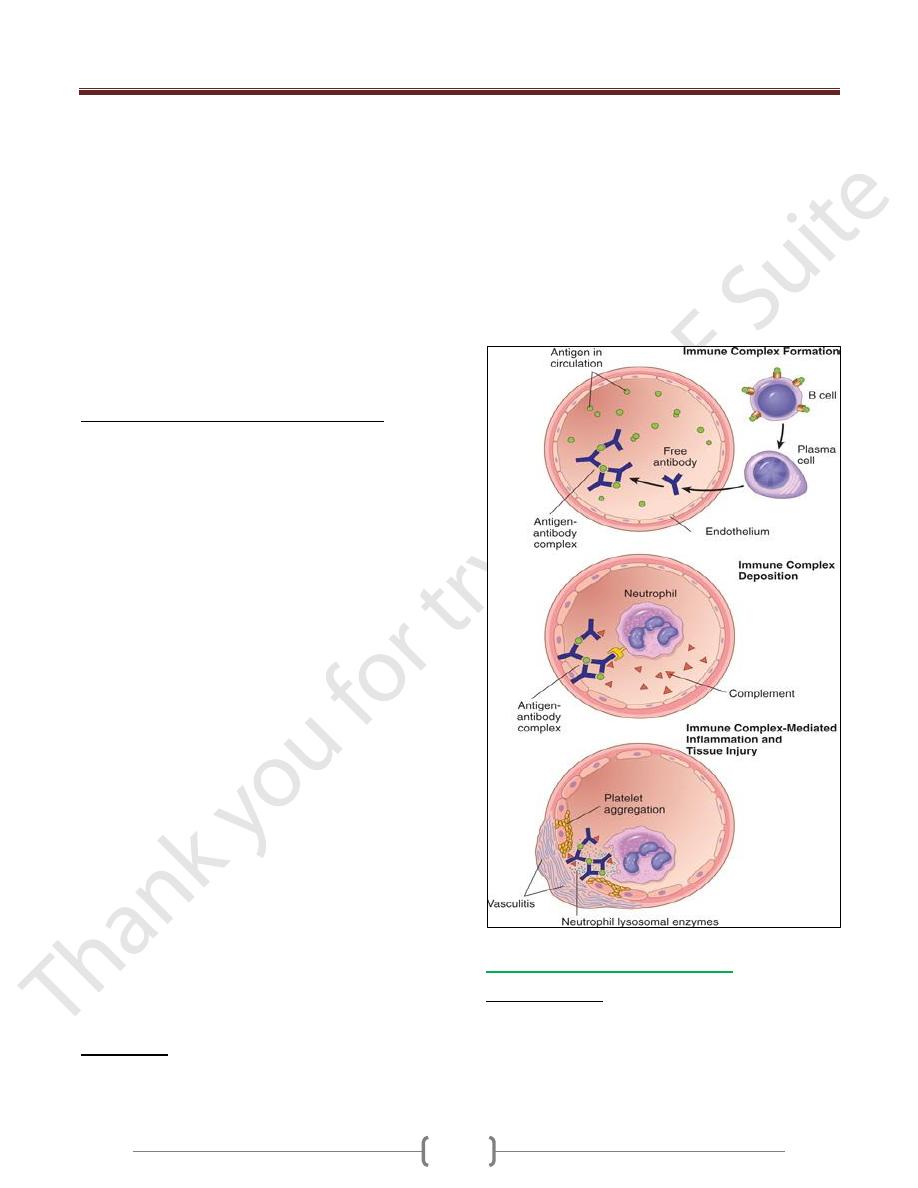

Immune complex diseases (type III

hypersensitivity)

Are caused by antibodies binding to antigens to form

immune complexes that circulate and deposit in vascular

beds and stimulate inflammation, typically as a

consequence of complement activation. Tissue injury in

these diseases is the result of the inflammation.

Antigen-antibody (immune) complexes that are formed in

the circulation may deposit in blood vessels, leading to

complement activation and acute inflammation.

The antigens in these complexes may be exogenous

antigens, such as microbial proteins, or endogenous

antigens, such as nucleoproteins.

Small amounts of antigen-antibody complexes may be

produced during normal immune responses and are

usually phagocytosed and destroyed.

Immune complex-mediated injury is systemic when

complexes are formed in the circulation and are deposited

in several organs, or it may be localized to particular

organs (e.g., kidneys, joints, or skin) if the complexes are

formed and deposited in a specific site.

Systemic Immune Complex Disease

The pathogenesis of systemic immune complex disease

can be divided into three phases:

(1) formation of antigen-antibody complexes in the circulation

(2) deposition of the immune complexes in various tissues

(3) inflammatory reaction in various sites throughout the body

Acute serum sickness

It was first described in humans when large amounts of

foreign serum were administered for passive immunization

(e.g., in persons receiving horse serum containing

antidiphtheria antibody

Approximately 5 days after the foreign protein is injected,

specific antibodies are produced; these react with the

antigen still present in the circulation to form antigen-

antibody complexes.

The complexes deposit in blood vessels in various tissue

beds, triggering the subsequent injurious inflammatory

reaction.

Several variables determine whether immune complex

formation leads to tissue deposition and disease.

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

60

1) The size of the complexes. Very large complexes or

complexes with many free IgG Fc regions (typically

formed in antibody excess) are rapidly removed from the

circulation by macrophages in the spleen and liver and are

therefore usually harmless.

2) The charge of the complex,

3) The valency of the antigen,

4) The avidity of the antibody, 5-the hemodynamics of a

given vascular bed

The favored sites of deposition are:

Kidneys, joints, and small blood vessels in many tissues.

Localization in the kidney and joints is explained in part

by the high hemodynamic pressures associated with the

filtration function of the glomerulus and the synovium.

The third phase, the inflammatory reaction.

During this phase (approximately 10 days after antigen

administration), clinical features such as fever, urticaria,

arthralgias, lymph node enlargement, and proteinuria

appear.

The immune complexes activate the complement system,

leading to the release of biologically active fragments

such as the anaphylatoxins (C3a and C5a), which increase

vascular permeability and are chemotactic for neutrophils

and monocytes

The complexes also bind to Fcγ receptors on neutrophils

and monocytes, activating these cells.

phagocytosis of immune complexes by the leukocytes

results in the secretion of a variety of additional pro-

inflammatory substances, including prostaglandins,

vasodilator peptides, and chemotactic substances, as well

as lysosomal enzymes capable of digesting basement

membrane, collagen, elastin, and cartilage, and reactive-

oxygen species that damage tissues.

Immune complexes can also cause platelet aggregation

and activate Hageman factor; both of these reactions

augment the inflammatory process and initiate formation

of microthrombi, which contribute to the tissue injury by

producing local ischemia

The resultant pathologic lesion is termed vasculitis if it

occurs in blood vessels, glomerulonephritis if it occurs in

renal glomeruli,arthritis if it occurs in the joints, & so on.

(IgG and IgM) and antibodies that bind to phagocyte Fc

receptors (IgG). During the active phase of the disease,

consumption of complement may result in decreased

serum complement levels.

Morphology

:

The morphologic appearance of immune complex injury

is dominated by acute necrotizing

vasculitis, microthrombi, and superimposed ischemic

necrosis accompanied by acute inflammation of the

affected organs.

The necrotic vessel wall takes on a smudgy eosinophilic

appearance called fibrinoid necrosis, caused by protein

deposition

However, chronic immune complex disease develops

when there is persistent antigenemia or repeated exposure

to an antigen.

This occurs in some human diseases, such as systemic

lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Local Immune Complex Disease

Arthus reaction:

In which an area of tissue necrosis appears as a result of

acute immune complex vasculitis.

The reaction is produced experimentally by (injecting an

antigen into the skin of a previously immunized animal

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

61

i.e., pre-formed antibodies against the antigen are already

present in the circulation).

Because of the initial antibody excess, immune complexes

are formed as the antigen diffuses into the vascular wall;

these are precipitated at the site of injection and trigger

the same inflammatory reaction and histologic appearance

as in systemic immune complex disease.

Arthus lesions evolve over a few hours and reach a peak 4

to 10 hours after injection, when the injection site

develops visible edema with severe hemorrhage,

occasionally followed by ulceration.

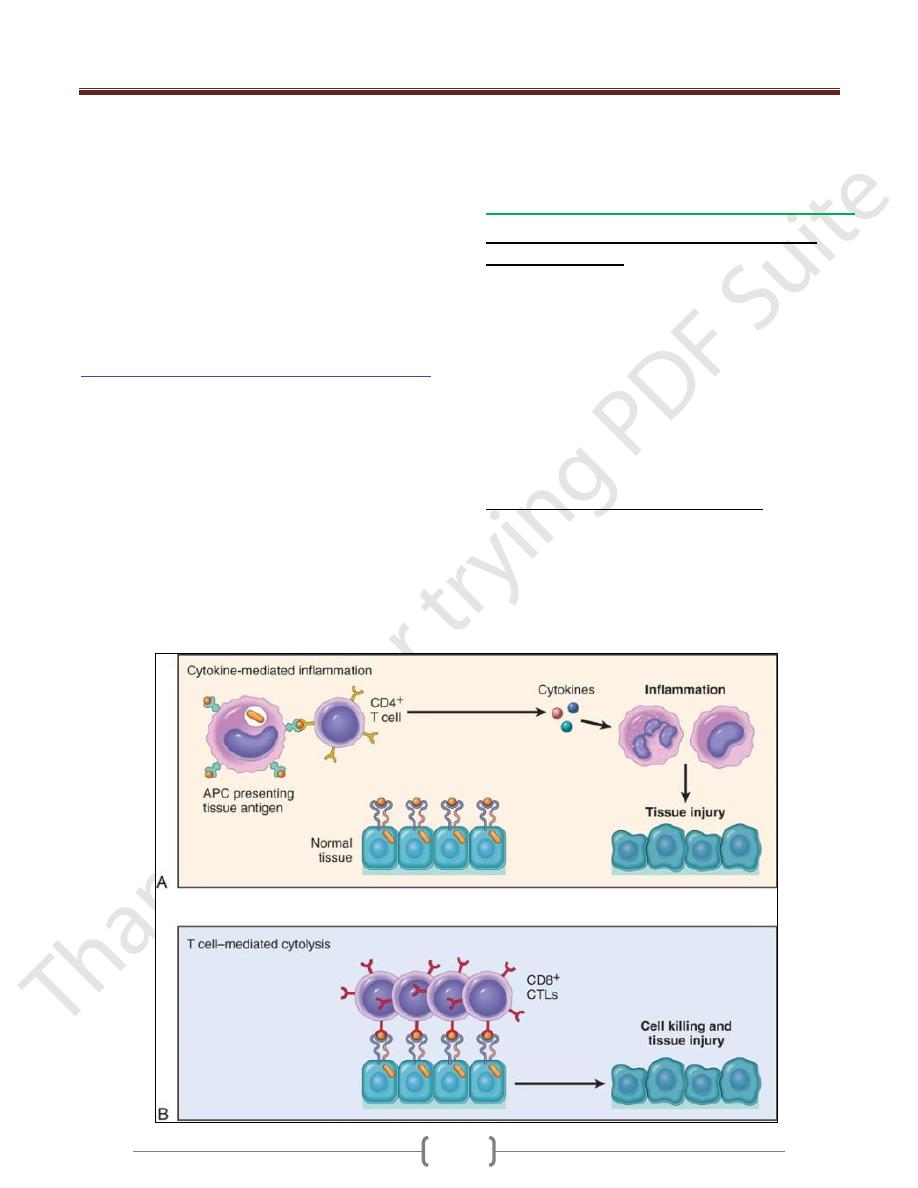

T cell–mediated (type IV) hypersensitivity

Are caused mainly by immune responses in which T

lymphocytes of the T

H

1 and T

H

17 subsets produce

cytokines that induce inflammation and activate

neutrophils and macrophages, which are responsible for

tissue injury. CD8+ CTLs also may contribute to injury

by directly killing host cells.

Two types of T cell reactions are capable of causing tissue

injury and disease:

(1) cytokine-mediated inflammation, in which the

cytokines are produced mainly by CD4+ T cells

(2) direct cell cytotoxicity, mediated by CD8+ Tc cells

In inflammation, exemplified by the delayed-type

hypersensitivity (DTH) reaction, CD4+ T cells of the T

H

1

and T

H

17 subsets secrete cytokines, which recruit and

activate other cells, especially macrophages, and these are

the major effector cells of injury.

Inflammatory reactions elicited by CD4+ T cells

1) First exposure to antigen and is essentially cell-

mediated immunity

Naive CD4+ T lymphocytes recognize peptide antigens of

self or microbial proteins in association with class II

MHC molecules on the surface of DCs (or macrophages)

that have processed the antigens.

If the DCs produce IL-12, the naive T cells differentiate

into effector cells of the T

H

1 type.

The cytokine IFN-γ, made by NK cells and by the T

H

1

cells themselves, further promotes T

H

1 differentiation,

providing a powerful positive feedback loop.

If the APCs produce IL-1, IL-6, or IL-23 instead of IL-

12, the CD4+ cells develop into T

H

17 effectors.

2) On subsequent exposure to the antigen,

The previously generated effector cells are recruited to the

site of antigen exposure and are activated by the antigen

presented by local APCs.

The T

H

1 cells secrete IFN-γ, which is the most potent

macrophage-activating cytokine known.

Activated macrophages also express more class II MHC

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

62

molecules and costimulators, and the cells secrete more

IL-12, thus stimulating more T

H

1 responses.

T

H

17 effector cells secrete IL-17 which promote the

recruitment of neutrophils (and monocytes) and thus

induce inflammation. Because the cytokines produced by

the T cells enhance leukocyte recruitment and activation,

these inflammatory reactions become chronic unless the

offending agent is eliminated or the cycle is interrupted

therapeutically.

Contact dermatitis is an example of tissue injury resulting

from T cell-mediated inflammation. It is evoked by

contact with the active component of poison ivy and

poison oak, which probably becomes antigenic by binding

to a host protein).

On reexposure of a previously exposed person to the

plants, sensitized T

H

1 CD4+ cells accumulate in the

dermis and migrate toward the antigen within the

epidermis. Here they release cytokines that damage

keratinocytes, causing separation of these cells and

formation of an intraepidermal vesicle, and inflammation

manifested as a vesicular dermatitis.

type 1 diabetes

multiple sclerosis, are caused by T

H

1 and T

H

17 reactions

against self-antigens, and

Crohn disease may be caused by uncontrolled reactions

involving the same T cells but directed against intestinal

bacteria.

rejection of transplants

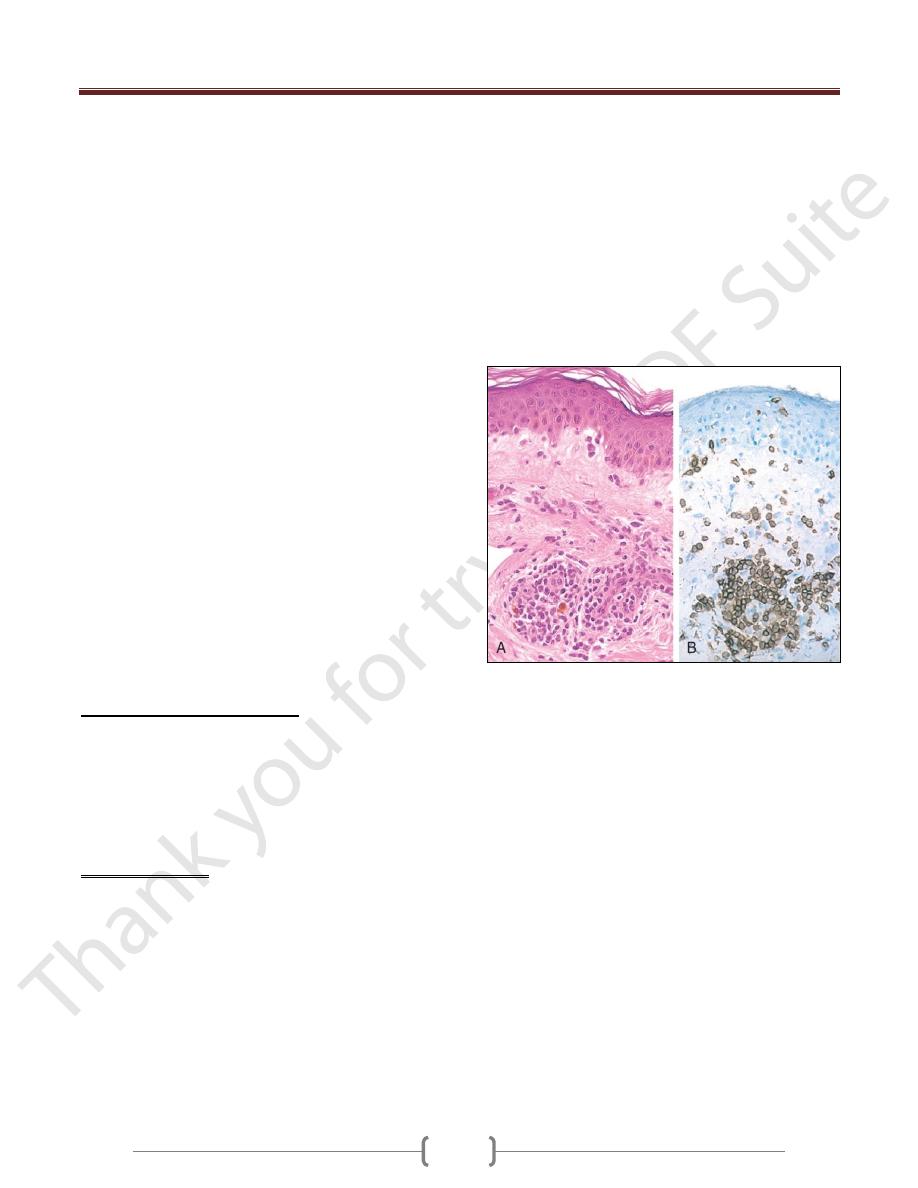

Delayed-Type Hypersensitivity

DTH is a T cell-mediated reaction that develops in

response to antigen challenge in a previously sensitized

individual. In contrast with immediate hypersensitivity,

the DTH reaction is delayed for 12 to 48 hours, which is

the time it takes for effector T cells to be recruited to the

site of antigen challenge and to be activated to secrete

cytokines.

Tuberculin reaction, elicited by challenge with a protein

extract of M. tuberculosis (tuberculin) in a person who has

previously been exposed to the tubercle bacillus. Between

8 and 12 hours after intracutaneous injection of

tuberculin, a local area of erythema and induration

appears, reaching a peak (typically 1 to 2 cm in diameter)

in 24 to 72 hours and thereafter slowly subsiding.

On histologic examination, the DTH reaction is

characterized by perivascular accumulation ("cuffing") of

CD4+ helper T cells and macrophages

Local secretion of cytokines by these cells leads to

increased microvascular permeability, giving rise to

dermal edema and fibrin deposition; the latter is the main

cause of the tissue induration in these responses.

DTH reactions are mediated primarily by T

H

1 cells; the

contribution of T

H

17 cells is unclear.

The tuberculin response is used to screen populations for

people who have had previous exposure to tuberculosis

and therefore have circulating memory T cells specific for

mycobacterial proteins.

Notably, immunosuppression or loss of CD4+ T cells

(e.g., resulting from HIV infection) may lead to a

negative tuberculin response even in the presence of a

severe infection.

Delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction in the skin. A,

Perivascular accumulation ("cuffing") of mononuclear

inflammatory cells (lymphocytes and macrophages), with

associated dermal edema and fibrin deposition. B,

Immunoperoxidase staining reveals a predominantly perivascular

cellular infiltrate that marks positively with anti-CD4 antibodies

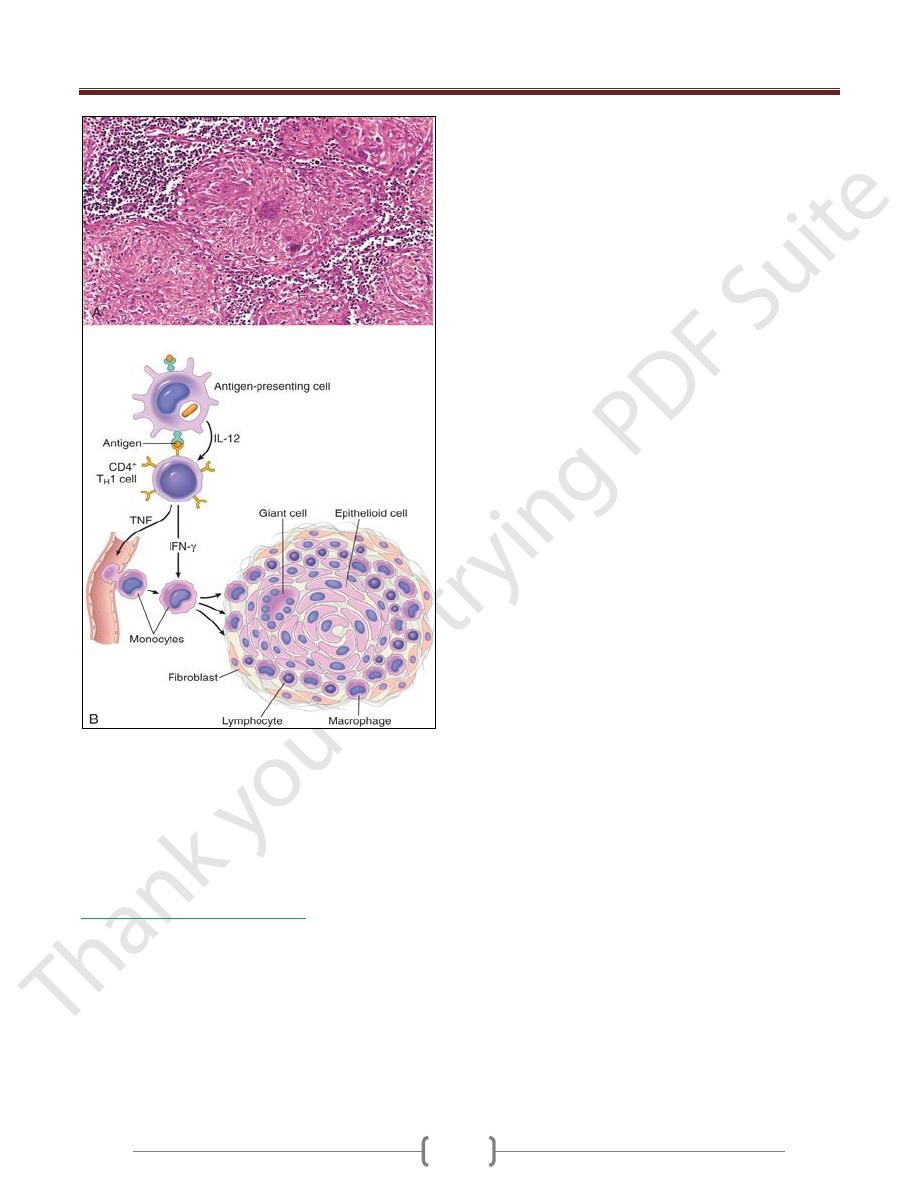

Prolonged DTH reactions against persistent microbes or

other stimuli may result in a special morphologic pattern

of reaction called granulomatous inflammation.

The initial perivascular CD4+ T cell infiltrate is

progressively replaced by macrophages over a period of 2

to 3 weeks. They become large, flat, and eosinophilic, and

are called epithelioid cells.

The epithelioid cells occasionally fuse under the influence

of cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ) to form multinucleate giant cells.

A microscopic aggregate of epithelioid cells, typically

surrounded by a collar of lymphocytes, is called a granuloma

The process is essentially a chronic form of T

H

1-mediated

inflammation and macrophage activation

Older granulomas develop an enclosing rim of fibroblasts

and connective tissue.

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

63

Granulomatous inflammation.

A, A section of a lymph node shows several granulomas, each

made up of an aggregate of epithelioid cells and surrounded by

lymphocytes. The granuloma in the center shows several

multinucleate giant cells.

B, The events that give rise to the formation of granulomas in

type IV hypersensitivity reactions. Note the role played by T-

cell-derived cytokines.

T Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity

CD8+ CTLs kill antigen-bearing target cells.

Class I MHC molecules bind to intracellular peptide

antigens and present the peptides to CD8+ T lymphocytes,

stimulating the differentiation of these T cells into effector

cells called CTLs.

CTLs play a critical role in resistance to virus infections

and some tumors.

The principal mechanism of killing by CTLs is dependent

on the perforin-granzyme system. Perforin and granzymes

are stored in the granules of CTLs and are rapidly released

when CTLs engage their targets.

Perforin binds to the plasma membrane of the target cells

and promotes the entry of granzymes, which are proteases

that specifically cleave and thereby activate cellular

caspases. These enzymes induce apoptotic death of the

target cells

CTLs play an important role in the rejection of solid-

organ transplants and may contribute to many

immunologic diseases, such as type 1 diabetes (in which

insulin-producing β cells in pancreatic islets are destroyed

by an autoimmune T cell reaction).

CD8+ T cells may also secrete IFN-γ and contribute to

cytokine-mediated inflammation, but less so than CD4+

cells.

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

64

Autoimmune diseases

Is an immune reaction to self-antigens (i.e., autoimmunity

due to presence of autoreactive antibodies or T cells

Presumed autoimmune diseases range from those in

which specific immune responses are directed against one

particular organ or cell type and result in localized

tissue damage, to multisystem diseases characterized by

lesions in many organs and associated with multiple

autoantibodies or cell-mediated reactions against

numerous self-antigens

In the systemic diseases, the lesions affect principally the

connective tissue and blood vessels of the various

organs involved.

The diseases are often referred to as "collagen vascular"

or "connective tissue" disorders.

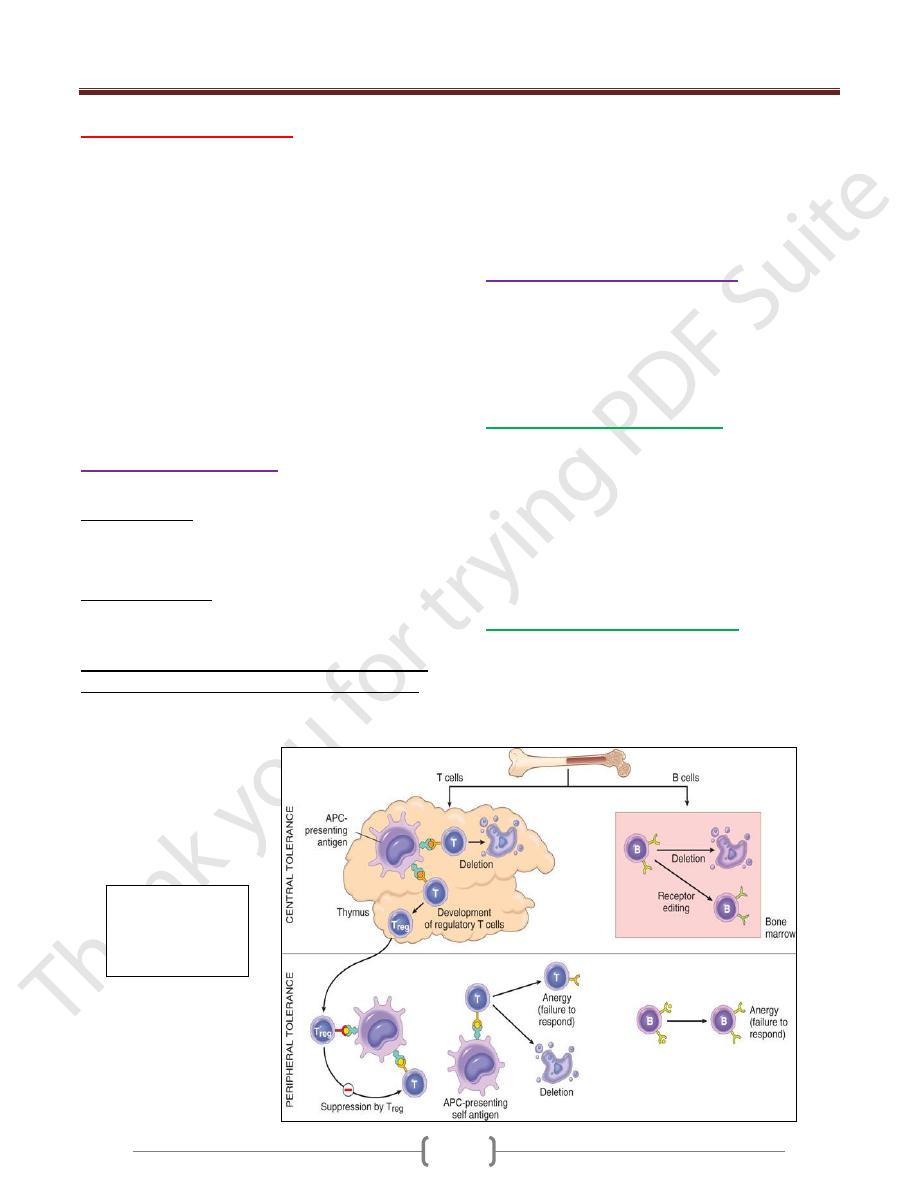

Immunological Tolerance

lack of immune responsiveness to one's own tissue antigens

Central tolerance. This refers to deletion of self-reactive

T and B lymphocytes during their maturation in central

lymphoid organs (i.e., in the thymus for T cells and in the

bone marrow for B cells).

Peripheral tolerance. Self-reactive T cells that escape

negative selection in the thymus can potentially dangerous

unless they are deleted.

Several mechanisms in the peripheral tissues that

silence autoreactive T cells have been identified:

1) Anergy: This refers to functional inactivation (rather than

death) of lymphocytes induced by encounter with antigens

under certain conditions

2) Suppression by regulatory T cells: The responses of T

lymphocytes to self-antigens may be actively suppressed

by regulatory T cells (Treg).

3) Activation-induced cell death: apoptosis of mature

lymphocytes as a result of self-antigen recognition.

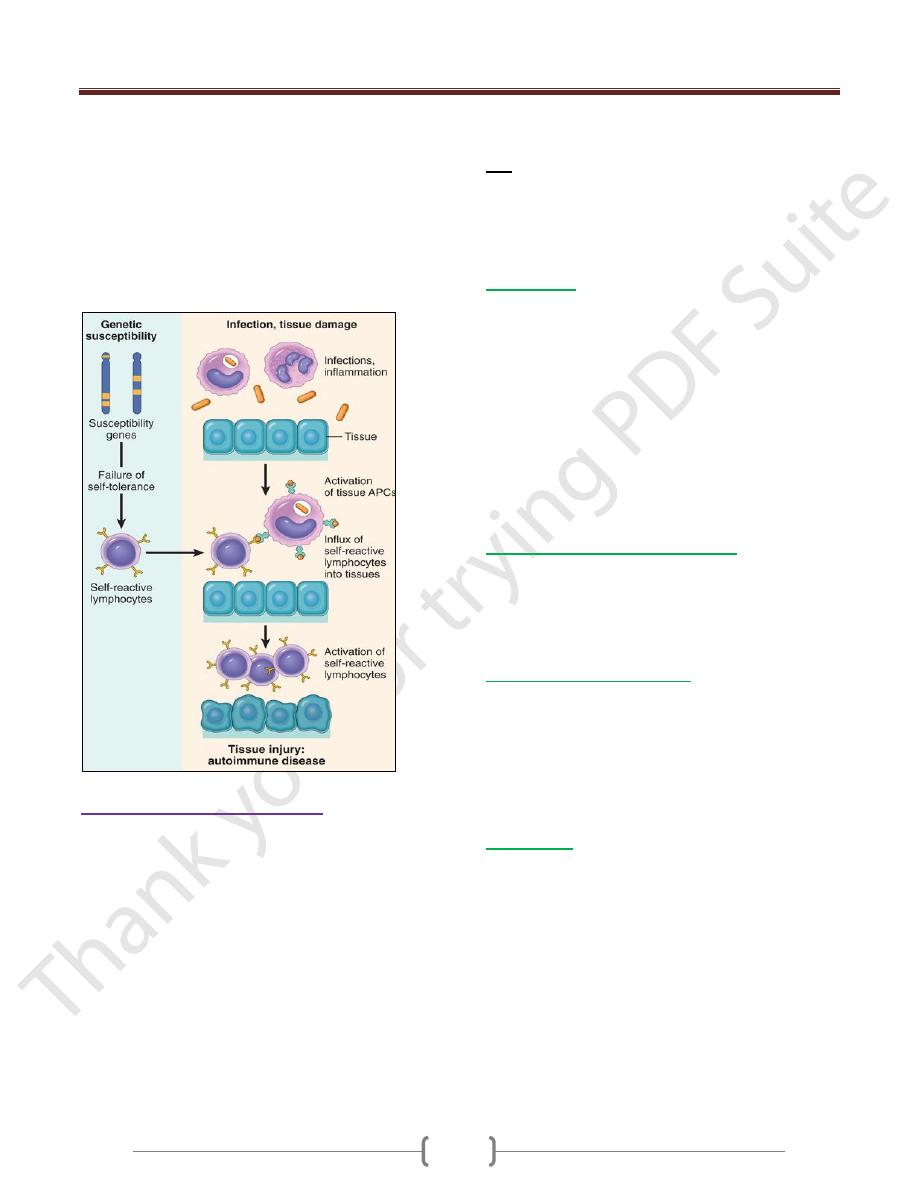

Mechanisms of Autoimmunity

The breakdown of self-tolerance and the development of

autoimmunity are probably related to the inheritance of

various susceptibility genes and environmental factors

that cause changes in tissues, often induced by infections or

injury, that alter the display & recognition of self-antigens

Genetic Factors in Autoimmunity

Autoimmune diseases have a tendency to run in families,

and there is a greater incidence of the same disease in

monozygotic than in dizygotic twins

Several autoimmune diseases are linked with the HLA

locus, especially class II alleles (HLA-DR, -DQ).

Genome-wide linkage analyses are revealing many

genetic loci that are associated with different

autoimmune diseases due to mutation or polymorphism

Role of Infections and Tissue Injury

Viruses and other microbes may share cross-reacting

epitopes with self-antigens,

Microbial infections with resultant tissue necrosis and

inflammation can cause upregulation of costimulatory

molecules on APCs in the tissue, thus favoring a break-

Central and

peripheral

tolerance (T -and

B- cell)

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

65

down of T cell anergy and subsequent T cell activation.

Tissue antigens may be altered by a variety of

environmental insults, like ultraviolet (UV) radiation

causes cell death and may lead to the exposure of nuclear

antigens, which elicit pathologic immune responses

in lupus; this mechanism is the proposed explanation for

the association of lupus flares with exposure to

sunlight. Smoking had an effect

there is a strong gender bias of autoimmunity,♀>♂

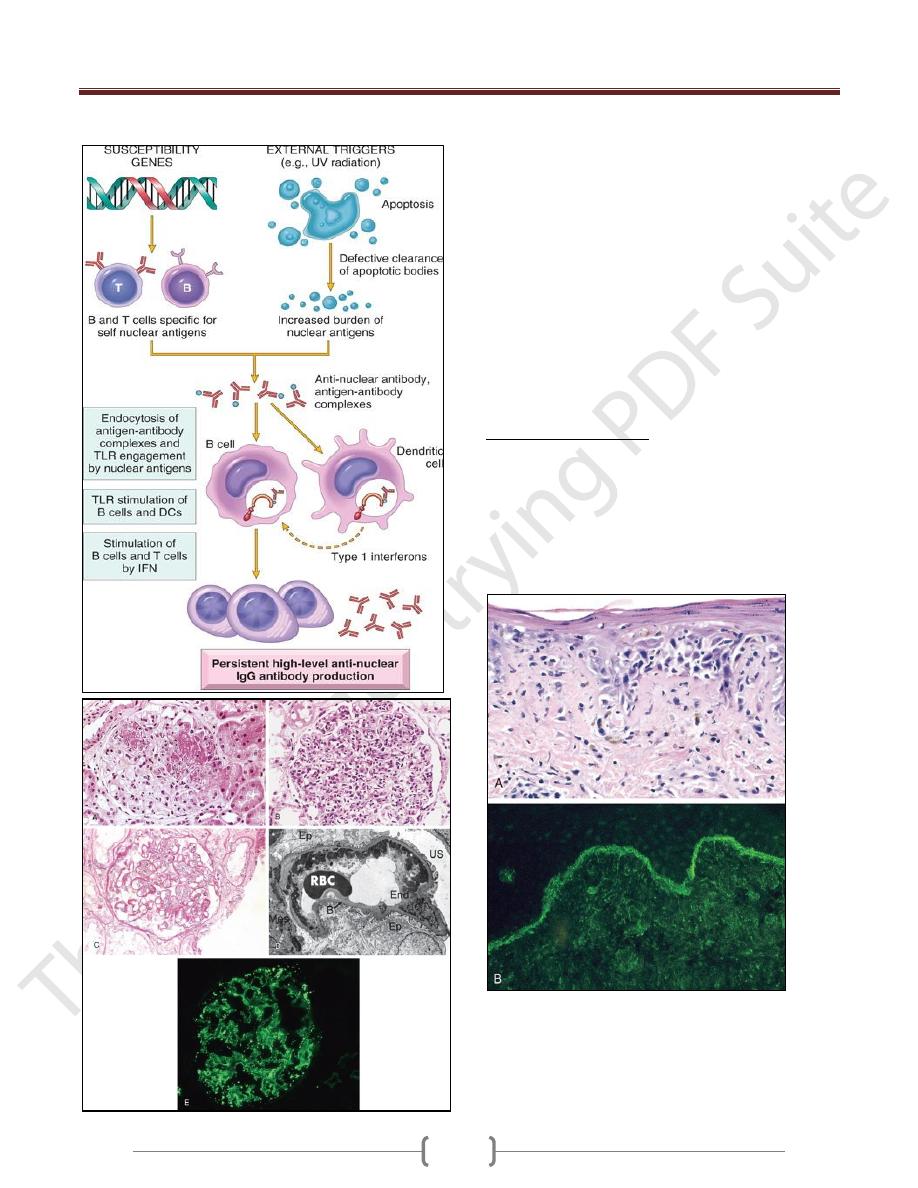

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystem

autoimmune disease of variable clinical behavior.

Clinically, it is an unpredictable, remitting and relapsing

disease of acute or insidious onset that may involve

virtually any organ in the body

It affects principally the skin, kidneys, serosal

membranes, joints, and heart.

Immunologically, the disease is associated with an

enormous array of autoantibodies, classically including

antinuclear antibodies (ANAs). The clinical presentation

of SLE is so variable, with so many overlapping features

with those of other autoimmune diseases (RA,

polymyositis, and others), that it has been necessary to

develop diagnostic criteria for SLE

The diagnosis is established by demonstration of 4 or

more of the criteria during any interval of observation.

4/11

1. Malar rash 2. Discoid rash 3. Photosensitivity

4. Oral ulcers 5. Arthritis 6. Serositis 7. Renal disorder

8. Neurologic disorder 9. Hematologic disorder

10. Immunologic disorder 11. Antinuclear antibody

Pathogenesis

1) Genetic Factors. Many lines of evidence support a

genetic predisposition to SLE.(Familial association,

HLA association, Genetic deficiencies of classical

pathway complement proteins, especially C1q, C2, or C4,

are seen in about 10% of patients with SLE.)

2) Environmental Factors.(Ultraviolet (UV) radiation,

Cigarette smoking, Sex hormones, Drugs

3) Immunologic Abnormalities in SLE.

Production abnormally large amounts of IFN-α.

TLR signals (Toll -like receptors) that activate B cells

specific for self-nuclear Ags. Failure of B cell tolerance

Spectrum of Autoantibodies in SLE

Antibodies have been identified against a host of nuclear &

cytoplasmic components of the cell(DNA, histones, nucleolar

Another group of antibodies is directed against surface

Ags of blood cells, platelets, lymphocytes, phospholipids

Mechanisms of Tissue Injury

Most organ damage in SLE is caused by immune complex

deposition. (Type III hypersensitivity)

Autoantibodies of different specificities contribute to the

pathology & clinical manifestations of SLE (type II hyper-

sensitivity). Autoantibodies against red cells, white cells, &

platelets opsonize these cells and lead to their phagocytosis

Morphology

The morphologic changes in SLE are therefore extremely

variable and depend on the nature of the autoantibodies,

the tissue in which immune complexes deposit, and the

course and duration of disease. The most characteristic

morphologic changes result from the deposition of

immune complexes in a variety of tissues.

1) Blood Vessels. An acute necrotizing vasculitis

2) Kidneys. The pathogenesis of all forms

of glomerulonephritis in SLE involves deposition of

DNA-anti-DNA complexes within the glomeruli.

3) Skin is involved in a majority of patients; a characteristic

erythematous or maculopapular eruption over the malar

eminences and bridge of the nose ("butterfly pattern")

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

66

4) Joints. 5) CNS. 6) spleen 7) heart 8) liver

Lupus nephritis

A. Focal lupus nephritis, with two necrotizing lesions in a glomerulus

(segmental distribution) (H&E stain).

B. Diffuse lupus nephritis. Note the marked global increase in

cellularity throughout the glomerulus (H&E stain).

C. Lupus nephritis showing a glomerulus with several "wire loop"

lesions representing extensive subendothelial deposits of immune

complexes (periodic acid Schiff stain).

D. Electron micrograph of a renal glomerular capillary loop from a

patient with SLE nephritis. Confluent subendothelial dense deposits

correspond to "wire loops" seen by light microscopy.

E. Deposition of IgG antibody in a granular pattern, detected by

immunofluorescence.

B, basement membrane; End, endothelium;

Ep, epithelial cell with foot processes; Mes, mesangium; RBC, red

blood cell in capillary lumen; US, urinary space; *, electron-dense

deposits in subendothelial location.

Clinical Manifestations

The patient is a young woman with some, but rarely all, of

the following features: a butterfly rash over the face,

fever, pain and swelling in one or more peripheral joints

(hands and wrists, knees, feet, ankles, elbows, shoulders),

pleuritic chest pain, and photosensitivity.

The most common causes of death are renal failure,

intercurrent infections, and cardiovascular disease

Systemic lupus erythematosus involving the skin.

A, An H&E-stained section shows liquefactive degeneration of the

basal layer of the epidermis and edema at the dermoepidermal

junction.

B, An immunofluorescence micrograph stained for IgG reveals

deposits of immunoglobulin along the dermoepidermal junction.

H&E, hematoxylin-eosin; IgG, immunoglobulin G.

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

67

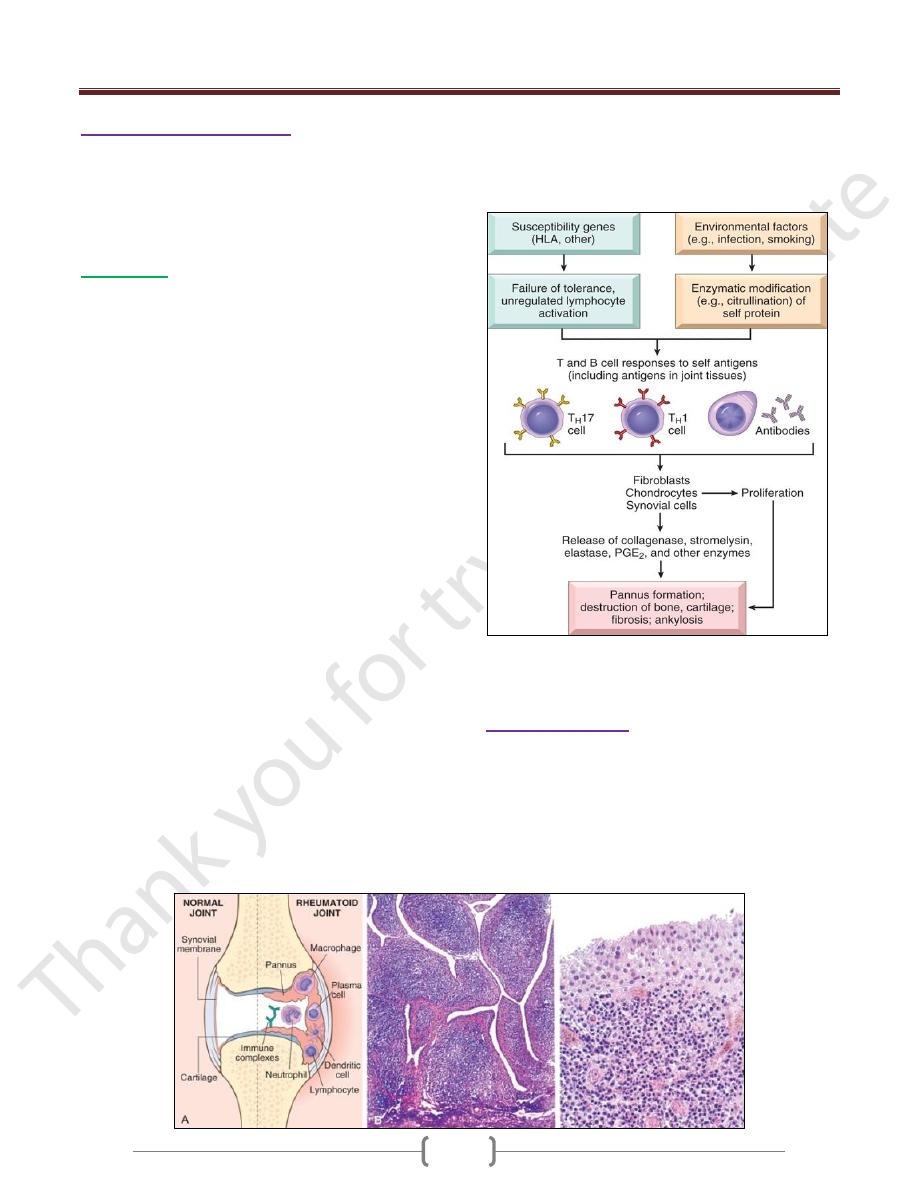

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

Is a systemic, chronic inflammatory disease affecting

many tissues but principally attacking the joints to

produce a nonsuppurative proliferative synovitis that

frequently progresses to destroy articular cartilage and

underlying bone with resulting disabling arthritis.

Morphology

RA typically presents as symmetric arthritis,

principally affecting the small joints of the hands and

feet, ankles, knees, wrists, elbows, and shoulders.

Typically, the proximal interphalangeal and

metacarpophalangeal joints are affected, but distal

interphalangeal joints are spared.

Histologically, the affected joints show chronic

synovitis, characterized by

1) synovial cell hyperplasia and proliferation;

2) dense perivascular inflammatory cell infiltrates

(frequently forming lymphoid follicles) in the synovium

composed of CD4+ T cells, plasma cells & macrophages;

3) increased vascularity due to angiogenesis;

4) neutrophils and aggregates of organizing fibrin on the

synovial surface and in the joint space; and

5) increased osteoclast activity in the underlying bone,

leading to synovial penetration and bone erosion

The classic appearance is that of a pannus, formed by

proliferating synovial-lining cells admixed with

inflammatory cells, granulation tissue, and fibrous

connective tissue; the overgrowth of this tissue is so

exuberant that the usually thin, smooth synovial

membrane is transformed into , edematous, frondlike

(villous) projections

With full-blown inflammatory joint involvement,

periarticular soft tissue edema usually develops,

classically manifested first by fusiform swelling of the

proximal interphalangeal joints

With progression of the disease, the articular cartilage

subjacent to the pannus is eroded and, virtually destroyed.

The subarticular bone may also be attacked and eroded.

Eventually the pannus fills the joint space, and subsequent

fibrosis and calcification may cause permanent ankylosis.

Rheumatoid arthritis. A, A joint lesion. B, Low magnification reveals

marked synovial hypertrophy with formation of villi. C, At higher

magnification, dense lymphoid aggregates are seen in the synovium

Sjögren Syndrome

Sjögren syndrome is a clinicopathologic entity

characterized by dry eyes (keratoconjunctivitis sicca)

and dry mouth (xerostomia), resulting from immune-

mediated destruction of the lacrimal and salivary glands.

It occurs as an isolated disorder (primary form), or more

often in association with another autoimmune disease

(secondary form).

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

68

Involved tissues show an intense lymphocyte (primarily

activated CD4+ T cells) & plasma-cell infiltrate,

occasionally forming lymphoid follicles with germinal

centers.

The disease is believed to be caused by an autoimmune

T-cell reaction against an unknown self-antigen(s)

expressed in these glands, or immune reactions against the

antigens of a virus that infects the tissues The disease is

believed to be caused by an autoimmune T-cell reaction

against an unknown self-antigen(s) expressed in these

glands, or immune reactions against the antigens of a

virus that infects the tissues

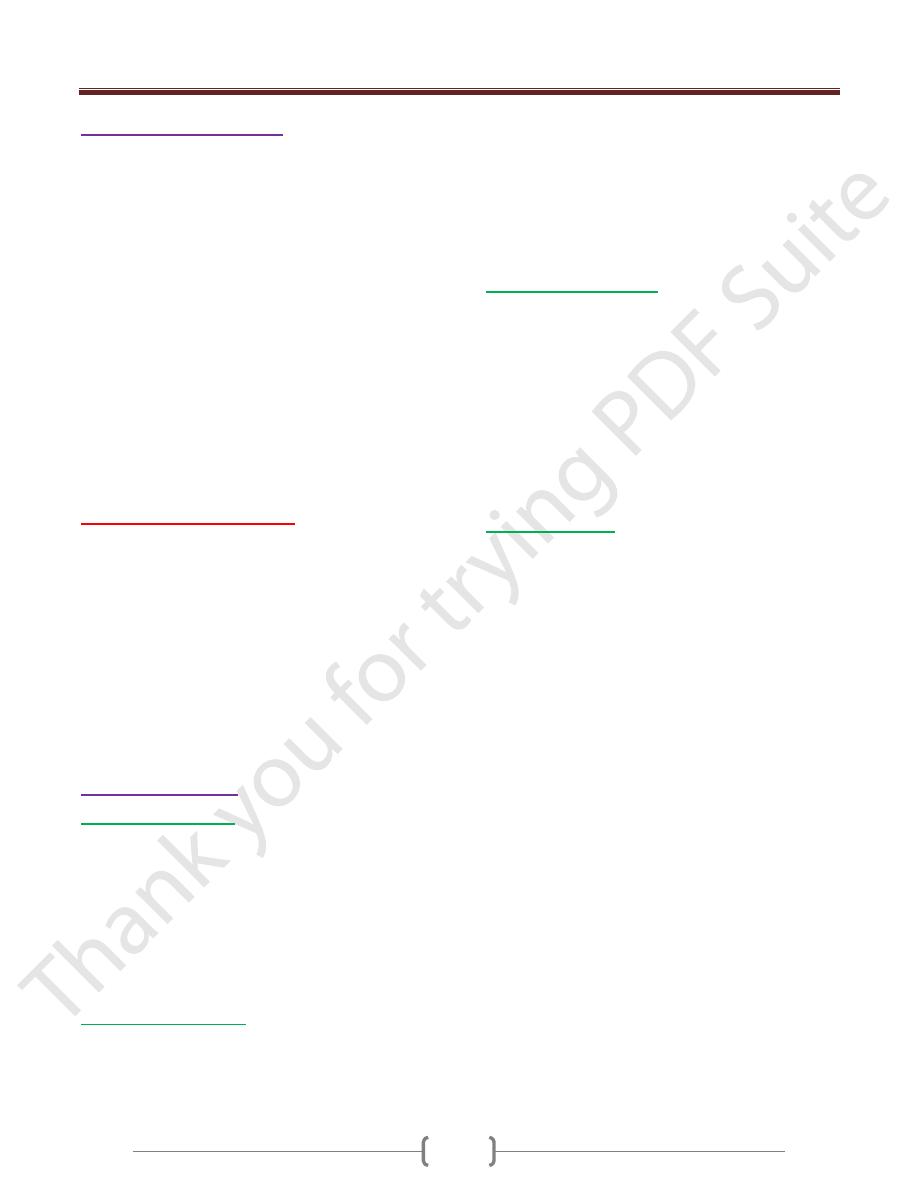

Sjögren syndrome. A, Enlargement of the salivary gland. B,

The histologic view shows intense lymphocytic and plasma cell

infiltration with ductal epithelial hyperplasia.

Systemic Sclerosis (Scleroderma)

This disorder is better labeled (SS), because it is

characterized by excessive fibrosis throughout the body

and not just the skin.

Cutaneous involvement is the usual presenting symptom

in approximately 95% of cases,

but it is the visceral involvement-of the gastrointestinal

tract, lungs, kidneys, heart, and skeletal muscles-that

produces the major morbidity and mortality.

Fibroblast activation with excessive fibrosis is the

hallmark of systemic sclerosis. .

It is proposed that CD4+ cells responding to an

unidentified antigen accumulate in the skin and release

cytokines that activate mast cells and macrophages; in

turn, these cells release fibrogenic cytokines such as IL-

1, PDGF, TGF-β, and fibroblast growth factors.

B-cell activation also occurs, as indicated by the presence

of hypergammaglobulinemia and ANAs.

Almost all patients develop Raynaud phenomenon

Endothelial injury and microvascular disease are

commonly present in the lesions of systemic sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis.

A, Normal skin.

B, Extensive deposition of dense collagen in the dermis. C, The

extensive subcutaneous fibrosis has virtually immobilized the

fingers, creating a clawlike flexion deformity.

Loss of blood supply has led to cutaneous ulcerations.

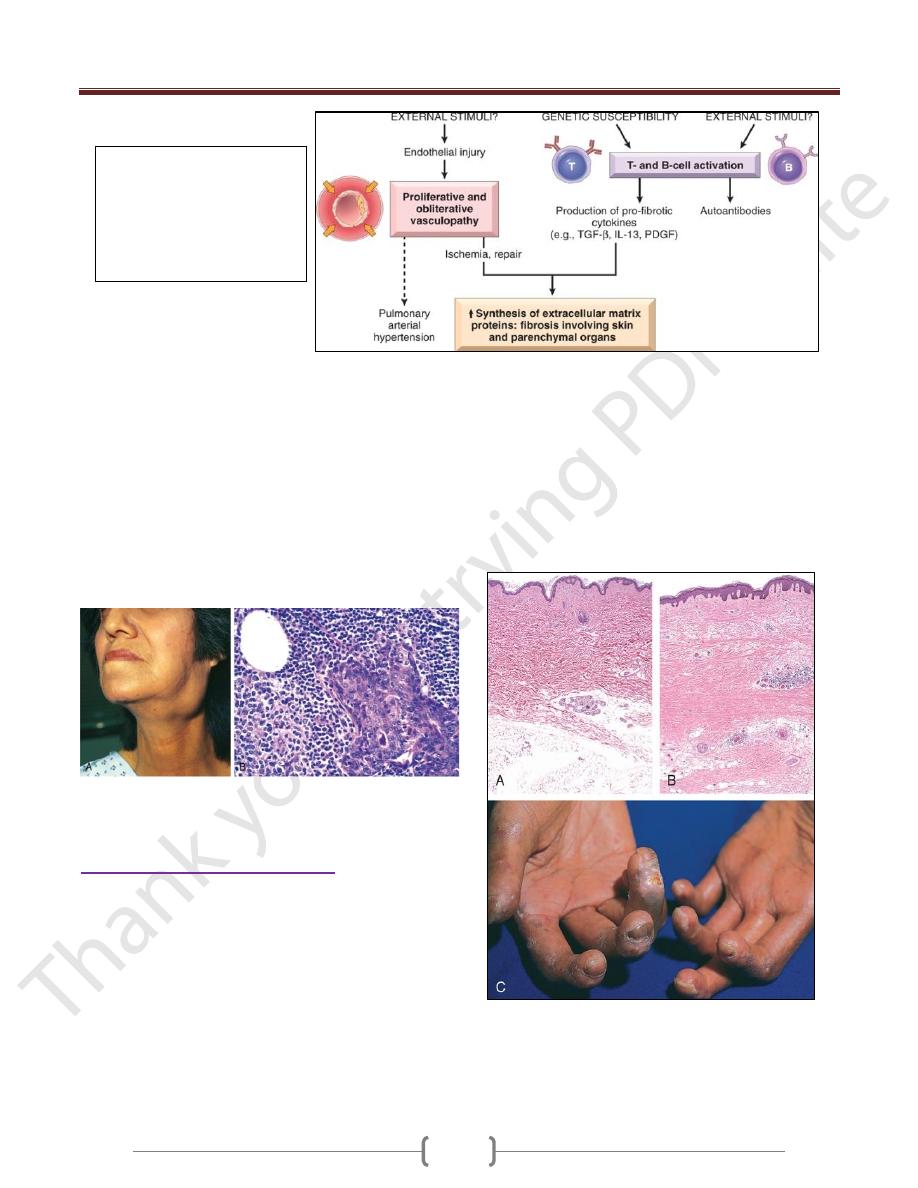

Pathogenesis of SS: unknown

external stimuli cause vascular

abnormalities and immune

activation in genetically

susceptible individual leads to

excessive fibrosis

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

69

Inflammatory Myopathies

Inflammatory myopathies make up a heterogeneous group

of rare disorders characterized by immune-mediated

muscle injury and inflammation.

Three disorders-:

polymyositis,

dermatomyositis,

and inclusion body myositis-have been described.

Women with dermatomyositis have a slightly increased risk

of developing visceral cancers (of the lung, ovary, stomach)

The immunologic evidence supports antibody-mediated

tissue injury in dermatomyositis, whereas polymyositis and

inclusion body myositis seem to be mediated by CTLs.

ANAs are present in most patients.

Only Jo-1 antibodies, directed against transfer RNA

synthetase, are specific for this group of disorders

Rejection of transplants

The major barrier to transplantation of organs from one

individual to another of the same species (called allografts)

is immunologic rejection of the transplanted tissue

Rejection of allografts is a response to MHC molecules,

which are so polymorphic that no two individuals in an

outbred population are likely to express exactly the same

set of MHC molecules

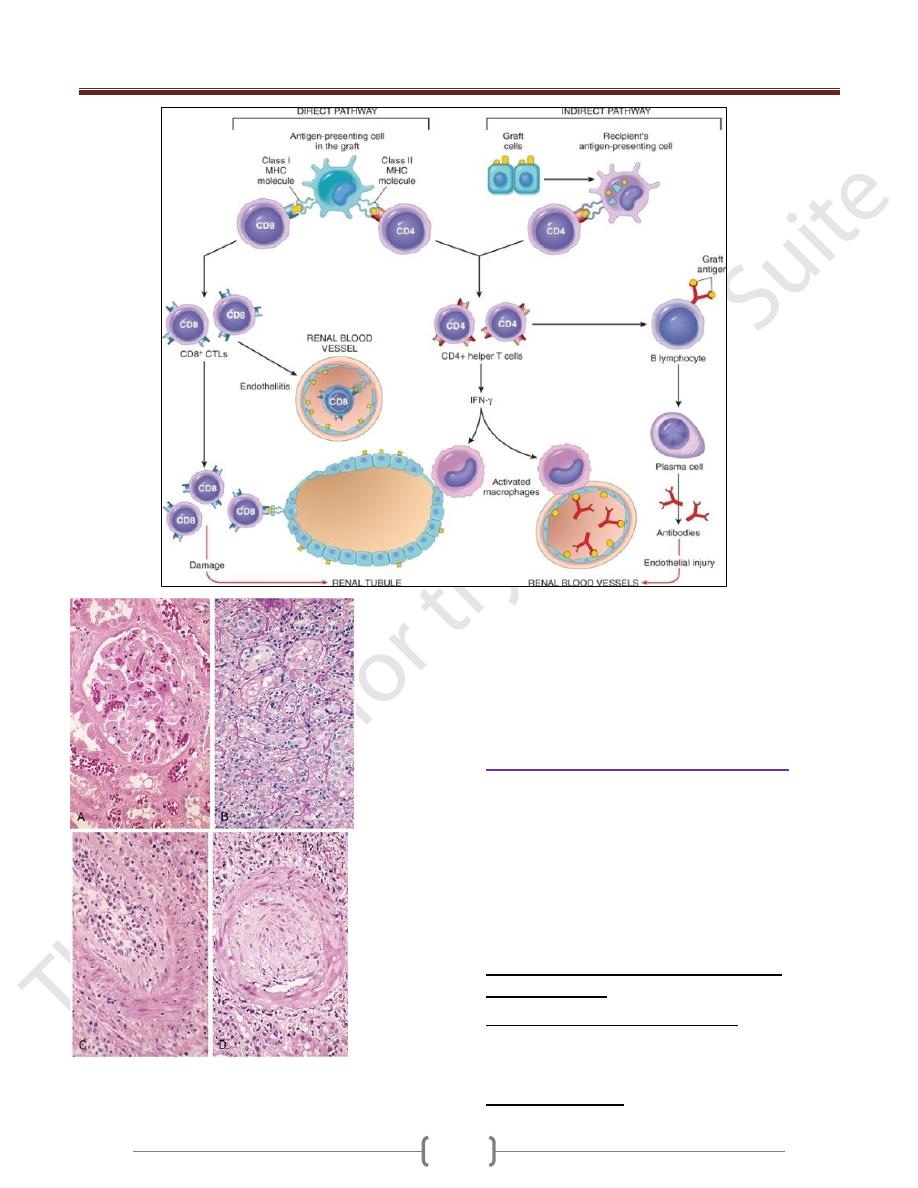

Effector Mechanisms of Graft Rejection

Recognition of alloAgs by direct and indirect pathway

lead to T cells and antibodies reactive with the graft are

involved in the rejection of most solid-organ allografts

Morphology (Types)

Hyperacute Rejection

.

Occurs within minutes to a few hours after transplantation

in a presensitized host and is typically recognized by the

surgeon just after the vascular anastomosis is completed.

The histology is characterized by widespread acute

arteritis and arteriolitis, vessel thrombosis, and

ischemic necrosis, all resulting

From the binding of preformed antibodies to graft

endothelium. Virtually all arterioles and arteries exhibit

characteristic acute fibrinoid necrosis of their walls,

Acute cellular rejection

Is most commonly seen within the first months after

transplantation and is typically accompanied by clinical

signs of renal failure.

Histologically, there is usually extensive interstitial CD4+

and CD8+ T-cell infiltration with edema and mild

interstitial hemorrhage.

Glomerular and peritubular capillaries contain large

numbers of mononuclear cells, which may also invade

the tubules and cause focal tubular necrosis. In addition to

tubular injury, CD8+ T cells may also injure the

endothelium, causing an endotheliitis.

Acute humoral rejection (rejection vasculitis)

caused by antibodies

The histologic lesions may take the form of necrotizing

vasculitis with endothelial cell necrosis; neutrophilic

infiltration; deposition of antibody, complement, and

fibrin; and thrombosis.

Such lesions may be associated with ischemic necrosis of

the renal parenchyma.

The resultant narrowing of the arterioles may cause

infarction or renal cortical atrophy.

The proliferative vascular lesions mimic arteriosclerotic

thickening and are believed to be caused by cytokines

Chronic Rejection

:

Present clinically late after transplantation (months to

years) with a progressive rise in serum creatinine levels

(an index of renal dysfunction) over a period of 4 to 6

months.

The vascular changes occur predominantly in the arteries

and arterioles, which exhibit intimal smooth muscle cell

proliferation and extracellular matrix synthesis

Result in renal ischemia manifested by loss or hyalinization

of glomeruli, interstitial fibrosis, and tubular atrophy.

The vascular lesion may be caused by cytokines released by

activated T cells that act on the cells of the vascular wall.

Chronic rejection does not respond to standard immune-

suppression regimens& need other renal transplant

Hyperacute Rejection. Hyperacute rejection occurs

within minutes to a few hours after transplantation in a

presensitized host and is typically recognized by the

surgeon just after the vascular anastomosis is completed.

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

70

Morphologic patterns of graft rejection.

A, Hyperacute rejection of a kidney allograft showing endothelial

damage, platelet and thrombi in a glomerulus.

B, Acute cellular rejection of a kidney allograft with inflammatory

cells in the interstitium and between epithelial cells of the tubules.

C, Acute humoral rejection of a kidney allograft (rejection

vasculitis) with inflammatory cells & proliferating smooth muscle

cells in the intima

D, Chronic rejection in a kidney allograft with graft arteriosclerosis.

The arterial lumen is replaced by an accumulation of smooth muscle

cells and connective tissue in the intima.

Transplantation of Hematopoietic Cells

Bone marrow transplantation is increasingly used as

therapy for hematopoietic and some nonhematopoietic

malignancies, aplastic anemias, and certain immune

deficiency states

HSC previously was obtained from donor bone marrow,

now was harvested from peripheral blood after

administration of hematopoietic growth factor or from the

umbilical cord of newborn as a rich source of HSC

Two complications were raised from these

transplantations:

1) 1-Graft –versus –host Disease (GVHD) occurs when

immunologically competent T cells (or their precursors)

are transplanted into recipients who are immunologically

compromised. Either acute or chronic

2) 2-Immune deficiency leads to viral infections (EBV, CMV)

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

71

Immune deficiency diseases

Immune deficiency diseases may be caused by inherited

defects affecting immune system development, or they

may result from secondary effects of other diseases (e.g.,

infection, malnutrition, aging, immunosuppression,

autoimmunity, or chemotherapy).

Clinically, patients with immune deficiency present with

increased susceptibility to infections as well as to certain

forms of cancer.

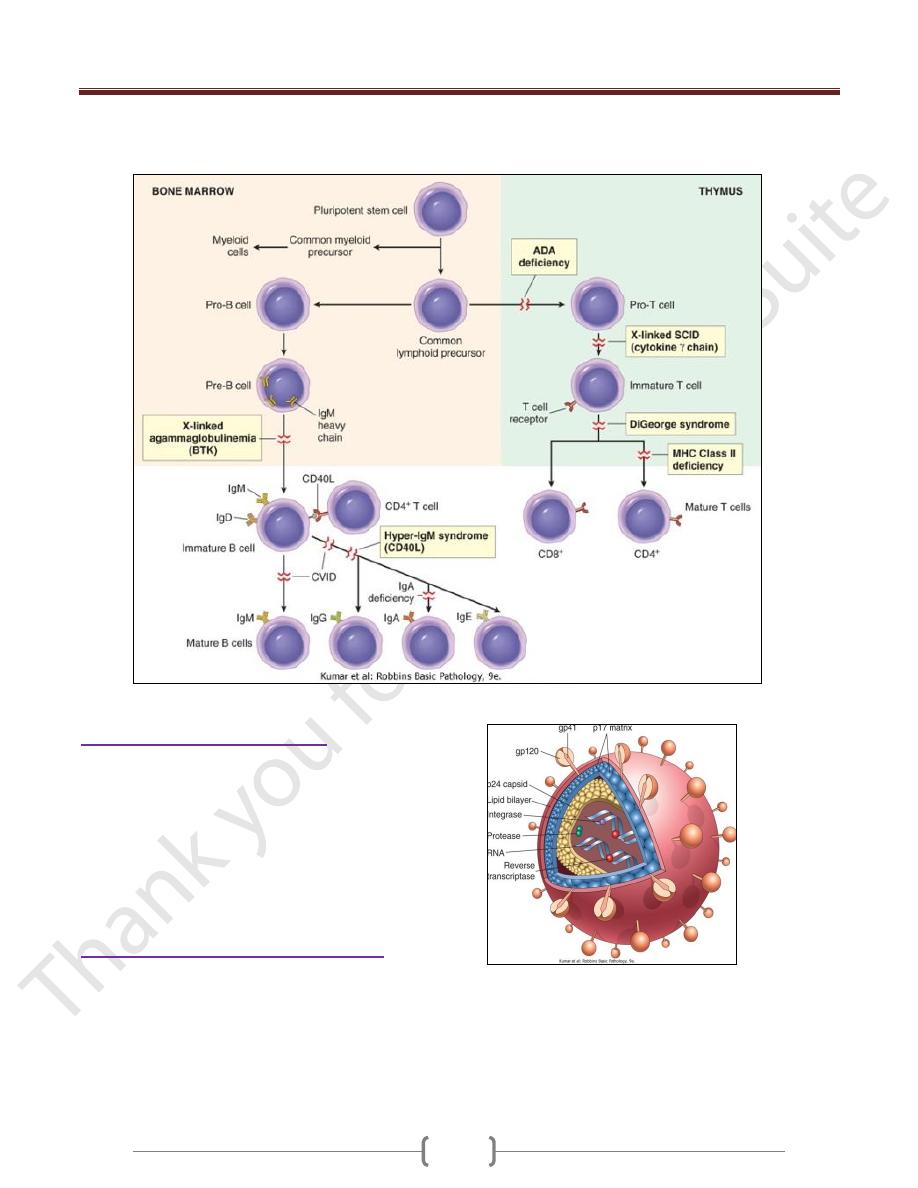

Primary Immune Deficiencies (congenital)

Most primary immune deficiency diseases are genetically

determined and affect either adaptive immunity (i.e.,

humoral or cellular) or innate host defense mechanisms,

including complement proteins and cells such as

phagocytes and NK cells.

Most primary immune deficiencies occur early in life

(between 6 months and 2 years of age).

X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia (XLA, Bruton

Disease)

It is characterized by the failure of pre-B cells to

differentiate into B cells; as a consequence, and as the

name implies, there is a resultant absence of gamma

globulin in the blood.

B-cell maturation stops because of mutations in a tyrosine

kinase that is associated with pre-B-cell signal transduction

Absent or markedly decreased numbers of B cells in the

circulation, depressed serum levels of all classes of

immunoglobulins.

The numbers of pre-B cells in the bone marrow may be

normal or reduced.

Underdeveloped germinal centers in peripheral lymphoid

tissues, Absence of plasma cells throughout the body

Normal T-cell-mediated responses

Common Variable Immunodeficiency

This is a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by:

hypogammaglobulinemia, impaired Ab responses to

infection (or vaccination), increased susceptibility to

infections

The basis of the Ig deficiency is variable (hence the name).

Isolated IgA Deficiency

The pathogenesis of IgA deficiency seems to involve a

block in the terminal differentiation of IgA-secreting B

cells to plasma cells; IgM and IgG subclasses of antibodies

are present in normal or even supranormal levels

Hyper-IgM Syndrome

Patients with the hyper-IgM syndrome produce normal (or

even supranormal) levels of IgM antibodies to antigens

but lack the ability to produce the IgG, IgA, or IgE

isotypes; the underlying defect is an inability of T cells

to induce B-cell isotype switching

The most common genetic abnormality is mutation of the

gene encoding CD40L.

The contact-dependent signals are provided by interaction

between CD40 molecules on B cells and CD40L (also

known as CD154), expressed on activated helper T cells.

There is also a defect in cell-mediated immunity because

the CD40-CD40L interaction is critical for helper T cell-

mediated activation of macrophages, the central reaction

of cell-mediated immunity.

These patients are also susceptible to a variety of

intracellular pathogens that are normally combated by

cell-mediated immunity

Thymic Hypoplasia: DiGeorge Syndrome

The disorder is a consequence of a developmental

malformation affecting the third and fourth pharyngeal

pouches-structures that give rise to the thymus,

parathyroid glands, and portions of the face and aortic

arch. Thus, in addition to the thymic and T-cell defects,

there may be parathyroid gland hypoplasia resulting in

hypocalcemic tetany,

Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID)

Defects in both humoral & cell-mediated immune responses

Affected infants are susceptible to severe recurrent

infections by a wide array of pathogens, including

bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoans; opportunistic

infections by Candida.

These are caused by mutations in the gene encoding the

common γ chain shared by the receptors for the cytokines

IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, and IL-15.

IL-7 is the most important in this disease because it is the

growth factor responsible for stimulating the survival

and expansion of immature B- and T-cell precursors in

the generative lymphoid organs.

It is X- linked (X-SCID) caused by mutations in

adenosine deaminase (ADA), an enzyme involved in

purine metabolism. ADA deficiency results in

accumulation of adenosine, which inhibit DNA synthesis

& are toxic to lymphocytes. It is Autosomal SCID

Patients with SCID are currently treated by bone marrow

transplantation.

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

72

X-SCID is the first disease in which gene therapy has

been used to successfully replace the mutated gene

Secondary Immune Deficiencies

Immune deficiencies secondary to other diseases or

therapies are much more common than the primary

(inherited) disorders.

Secondary immune deficiencies may be encountered in

patients with malnutrition, infection, cancer, renal

disease, or sarcoidosis. However, the most common cases

of immune deficiency are therapy-induced suppression of

the bone marrow and of lymphocyte function.

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

AIDS is a retroviral disease caused by the human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV). It is characterized by

infection and depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes, and by

profound immunosuppression leading to opportunistic

infections, secondary neoplasms, and neurologic

manifestations

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

73

Amyloidosis

Is a condition associated with a number of inherited and

inflammatory disorders in which extracellular deposits

of fibrillar proteins are responsible for tissue damage

and functional compromise

These abnormal fibrils are produced by the aggregation

of misfolded proteins

The presence of abundant charged sugar groups in these

adsorbed proteins give the deposits staining characteristics

that were thought to resemble starch (amylose).

Therefore, the deposits were called amyloid, despite the

realization that the deposits are unrelated to "starch."

Pathogenesis of Amyloid Deposition

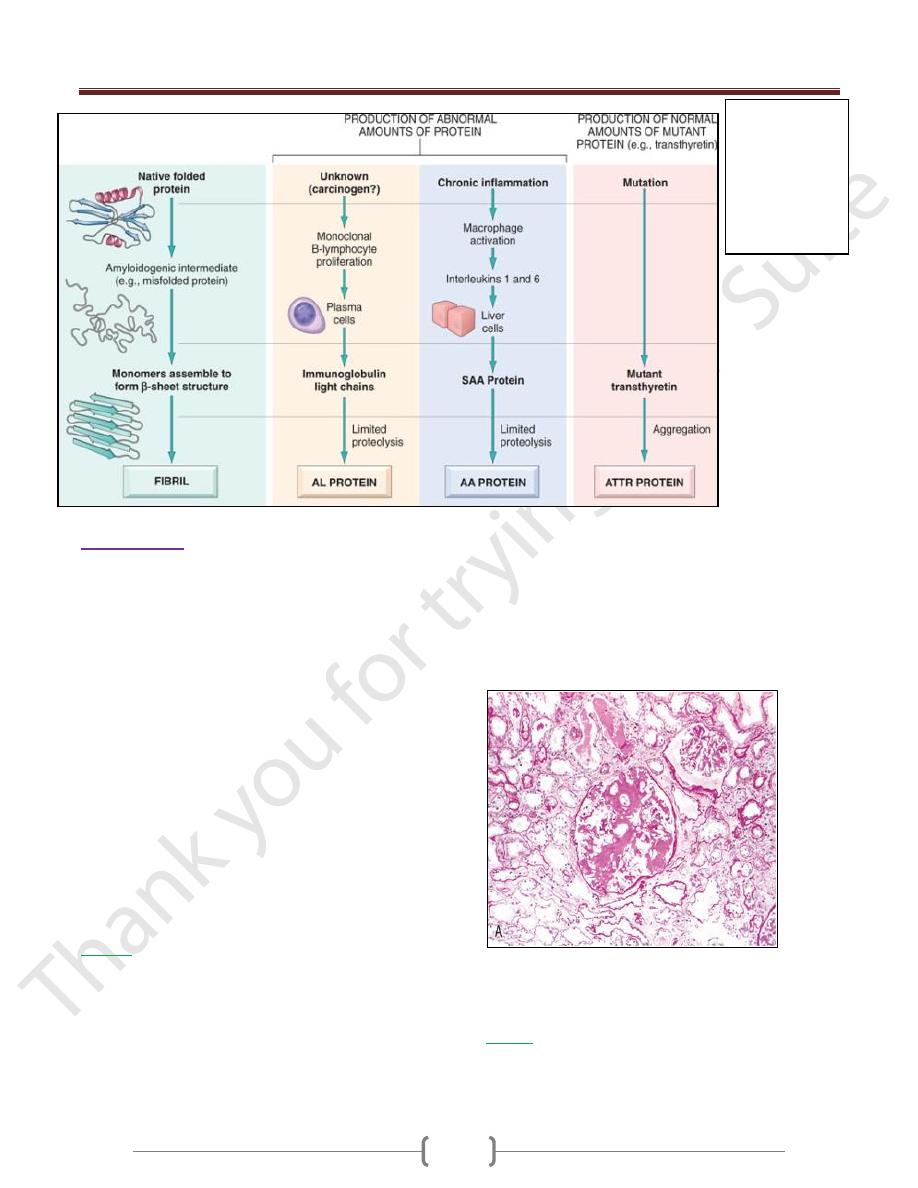

Amyloidosis is fundamentally a disorder of protein

misfolding.

More than 20 (at last count, 23) different proteins can

aggregate & form fibrils with the appearance of amyloid.

All amyloid deposits are composed of nonbranching

fibrils that are wound together .The dye Congo red

binds to these fibrils and produces a red-green

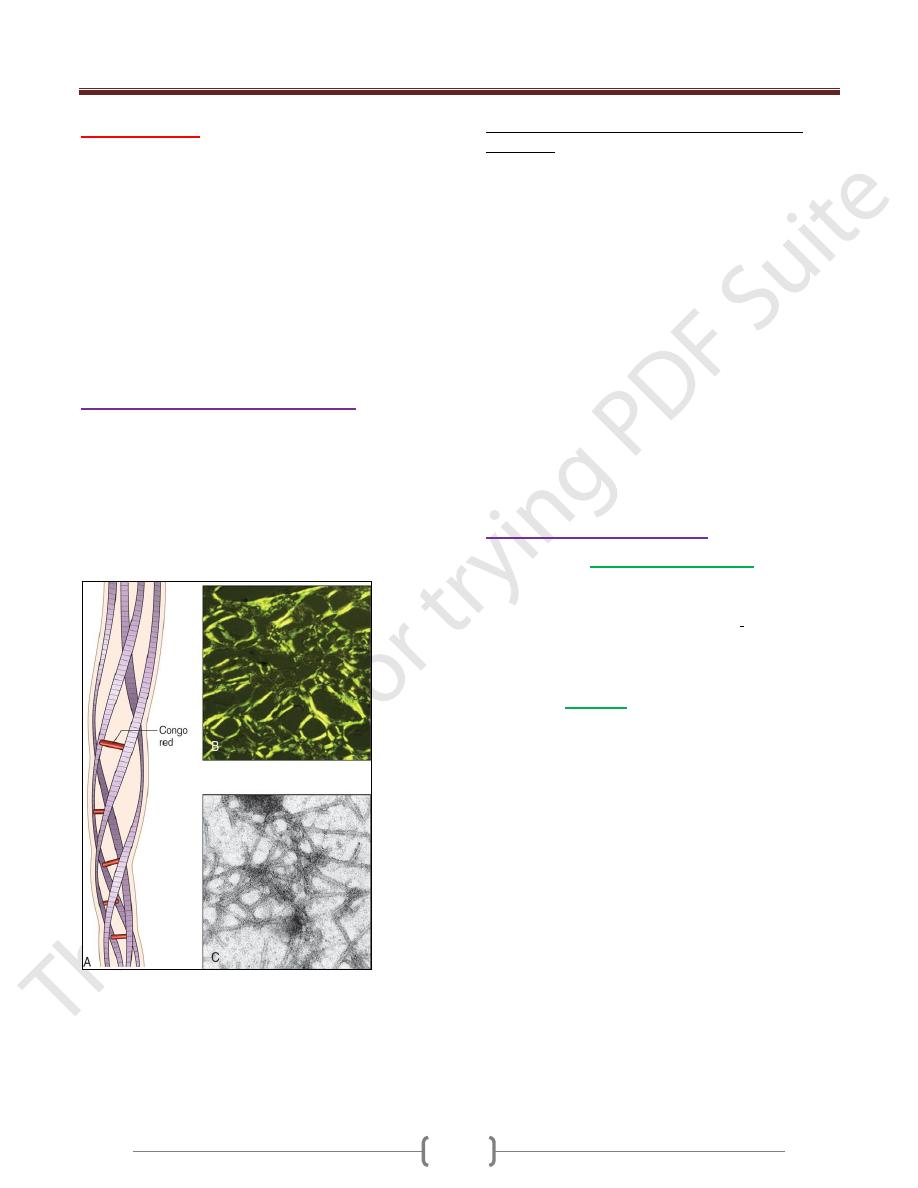

Structure of amyloid.

A, Schematic diagram of an amyloid fiber showing fibrils (4

shown, may be up to 6) wound around one another with

regularly spaced binding of the Congo red dye.

B, Congo red staining shows an apple-green birefringence under

polarized light, a diagnostic feature of amyloid.

C, Electron micrograph of 7.5-10 nm amyloid fibrils.

The proteins that form amyloid fall into 2 general

categories:

1) normal proteins that have an inherent tendency to fold

improperly,

2) Mutant proteins that is prone to misfolding and

subsequent aggregation. three are most common:

The AL (amyloid light chain) protein: is produced by

plasma cells and is made up of complete immunoglobulin

light chains,

The AA (amyloid-associated) fibril: is a protein derived

from serum precursor called SAA (serum amyloid-

associated) protein that is synthesized in the liver under

the influence of cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-1 that are

produced during inflammation.

Aβ amyloid: is found in cerebral lesion of Alzheimer

disease . constitutes the core of cerebral plaques

Transthyretin (TTR) : s a normal serum protein that

binds and transports thyroxine and retinol,

β

2

-Microglobulin: a component of MHC class I molecules

Classification of Amyloidosis

Amyloid may be

systemic (generalized),

involving

several organ systems,

On clinical grounds, the systemic, or generalized, pattern

is subclassified into primary amyloidosis when

associated with a monoclonal plasma cell proliferation &

Secondary amyloidosis when it occurs as a complication

of an underlying chronic inflammatory

Or it may be

localized

, when deposits are limited to a

single organ, such as the heart.

Hereditary or familial amyloidosis constitutes a

separate, heterogeneous group, with several distinctive

patterns of organ involvement.

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

74

Morphology

There are no consistent or distinctive patterns of organ or

tissue distribution of amyloid deposits

In amyloidosis secondary to chronic inflammatory

disorders, kidneys, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, adrenals,

and thyroid, as well as many other tissues,

On histologic examination, the amyloid deposition is

always extracellular and begins between cells, often

closely adjacent to basement membranes. As the amyloid

accumulates, it surrounding the cells and destroying them.

In the AL form, perivascular and vascular localizations

are common.

The histologic diagnosis of amyloid is based almost

entirely on its staining characteristics. The most

commonly used staining technique uses the dye Congo

red, which under ordinary light imparts a pink or red

color to amyloid deposits. Under polarized light the

Congo red-stained amyloid shows so-called apple-

green birefringence

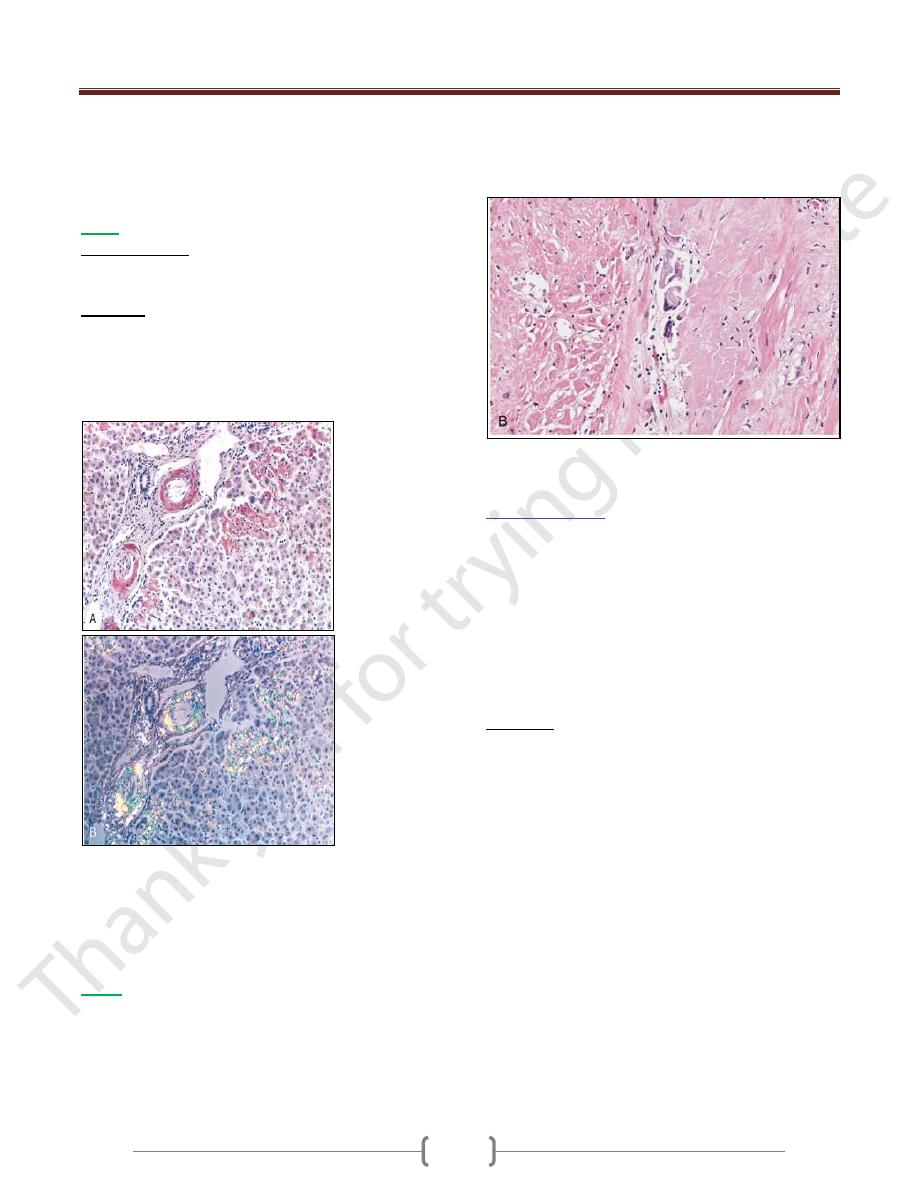

Kidney

Grossly, the kidney may appear unchanged, or it may be

abnormally large, pale, gray, and firm; in long-standing

cases, the kidney may be reduced in size.

Microscopically, the amyloid deposits are found

principally in the glomeruli, but they also are present in

the interstitial peritubular tissue as well as in the walls

of the blood vessels.

The glomerulus first develops focal deposits within the

mesangial matrix and diffuse or nodular thickenings

of the basement membranes of the capillary loops.

The interstitial peritubular deposits frequently are

associated with the appearance of amorphous pink casts

within the tubular lumens, presumably of a

proteinaceous nature.

Amyloidosis. A, Amyloidosis of the kidney. The glomerular

architecture is almost totally obliterated by the massive

accumulation of amyloid

Spleen

The deposits may be virtually limited to the splenic

follicles, splenic sinuses, splenic pulp, producing tapioca-

like granules

Pathogenesis of

amyloidosis. The

proposed

mechanisms

underlying

deposition of the

major forms of

amyloid fibrils

Unit 4: Diseases of the Immune System

75

Gross examination ("sago spleen"), the spleen is firm in

consistency.

The presence of blood in splenic sinuses usually imparts a

reddish color to the waxy, friable deposits.

Liver

Grossly: massive enlargement liver, is extremely pale,

grayish, and waxy on both the external surface and the cut

section.

Histologic analysis : amyloid deposits first appear in

the space of Disse and then progressively enlarge to

encroach on the adjacent hepatic parenchyma & sinusoids

The trapped liver cells undergo compression atrophy and

are eventually replaced by sheets of amyloid;

Amyloidosis.

A, A section of the liver stained with Congo red reveals pink-red

deposits of amyloid in the walls of blood vessels and along

sinusoids.

B, Note the yellow-green birefringence of the deposits when

observed by polarizing microscope

Heart

Grossly The deposits may not be evident on gross

examination, or they may cause minimal to moderate

cardiac enlargement. The most characteristic gross