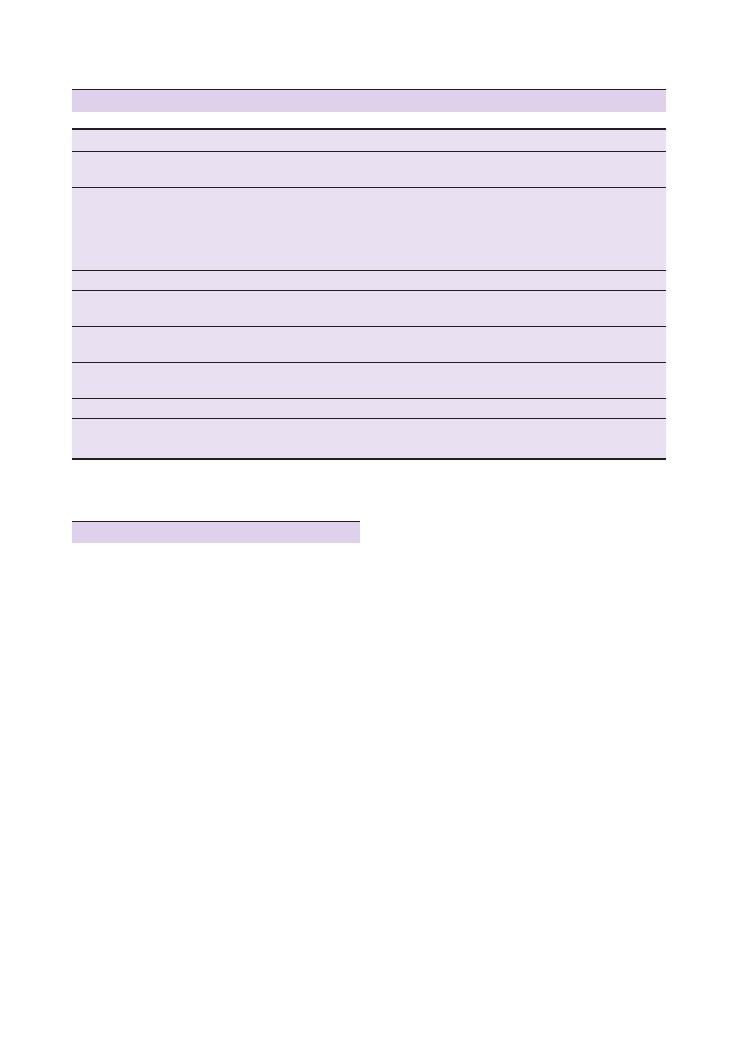

OSCEs for

Medical Finals

Companion website

This book is accompanied by a companion website:

www.wiley.com/go/khan/osces

featuring:

• Downloadable checklists from the book

• Survey showing which OSCE stations have a high chance of appearing in finals

This book is also available as an e-book.

For more details, please see

www.wiley.com/buy/9780470659410

or scan this QR code:

OSCEs for

Medical Finals

Hamed Khan

MBBS DGM MRCGP MRCP (London)

GP Principal and Undergraduate Tutor

Oxted, Surrey

Iqbal Khan

BSc MBBS

FY2 Doctor

Homerton University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

Akhil Gupta

BSc MBBS

Specialist Registrar in Anaesthetics

London Deanery

Nazmul Hussain

MBBS MRPharmS

GP ST3

Newham GP Vocational Training Scheme

Sathiji Nageshwaran

BSc MBBS

FY2 Doctor

Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust

A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication

This edition first published 2013 © 2013 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Wiley-Blackwell is an imprint of John Wiley & Sons, formed by the merger of Wiley’s

global Scientific, Technical and Medical business with Blackwell Publishing.

Registered office: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West

Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial offices: 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, USA

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about

how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our

website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in

accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs

and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as

trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names,

service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The

publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This

publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the

subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in

rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required,

the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

OSCEs for medical finals / Hamed Khan ... [et al.].

p. ; cm.

Objective structured clinical examinations for medical finals

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-470-65941-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-118-44190-9 (eMobi) –

ISBN 978-1-118-44191-6 (ePDF/ebook) – ISBN 978-1-118-44192-3 (ePub)

I. Khan, Hamed. II. Title: Objective structured clinical examinations for medical finals.

[DNLM: 1. Clinical Medicine–Examination Questions. 2. Clinical Competence–

Examination Questions. 3. Communication–Examination Questions. 4. Medical

History Taking–Examination Questions. 5. Physical Examination–Examination

Questions. WB 18.2]

616.0076–dc23

2012024677

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears

in print may not be available in electronic books.

Cover design by Sarah Dickinson

Set in 8.75/11 Minion pt by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited

1 2013

Contributors, vii

Acknowledgements, viii

Preface, ix

Part 1: Examinations

Top Tips, 1

1. Cardiovascular, 2

2. Respiratory, 7

3. Abdominal, 10

4. Peripheral nervous system, 20

5. Central nervous system, 28

6. Ophthalmoscopy, 37

7. Cerebellar, 40

8. Speech, 44

9. Thyroid, 48

10. Breast, 53

11. Rectal, 56

12. Hernia, 60

13. Testicular, 64

14. Vascular (arterial), 68

15. Vascular (venous), 73

16. Ulcer, 76

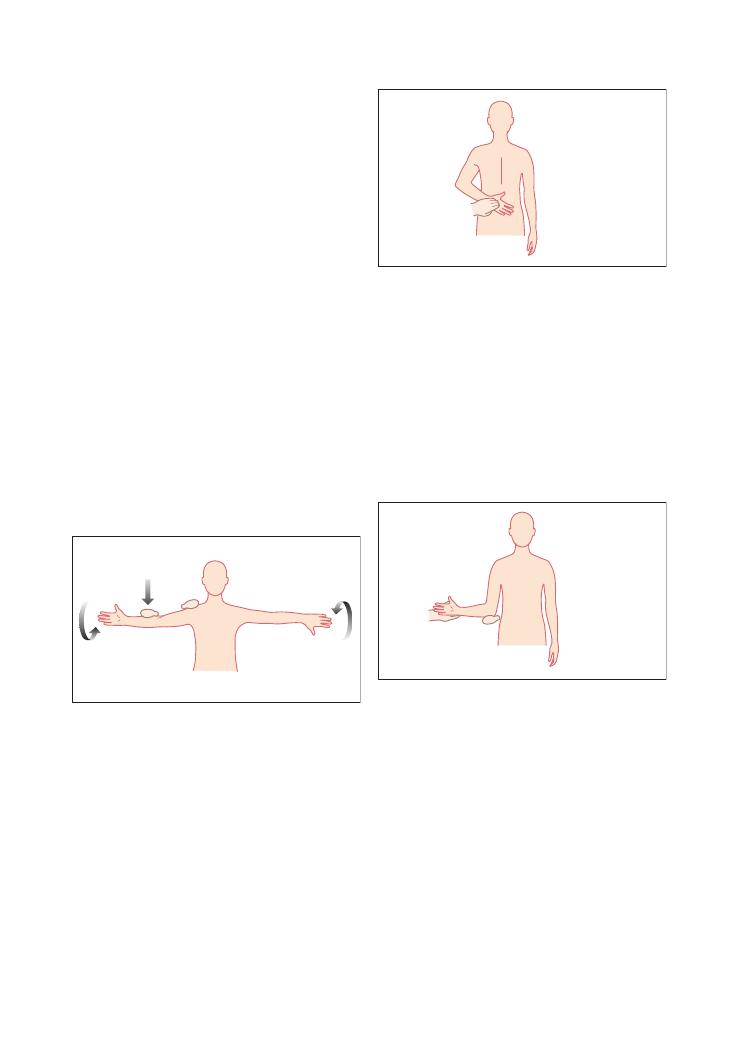

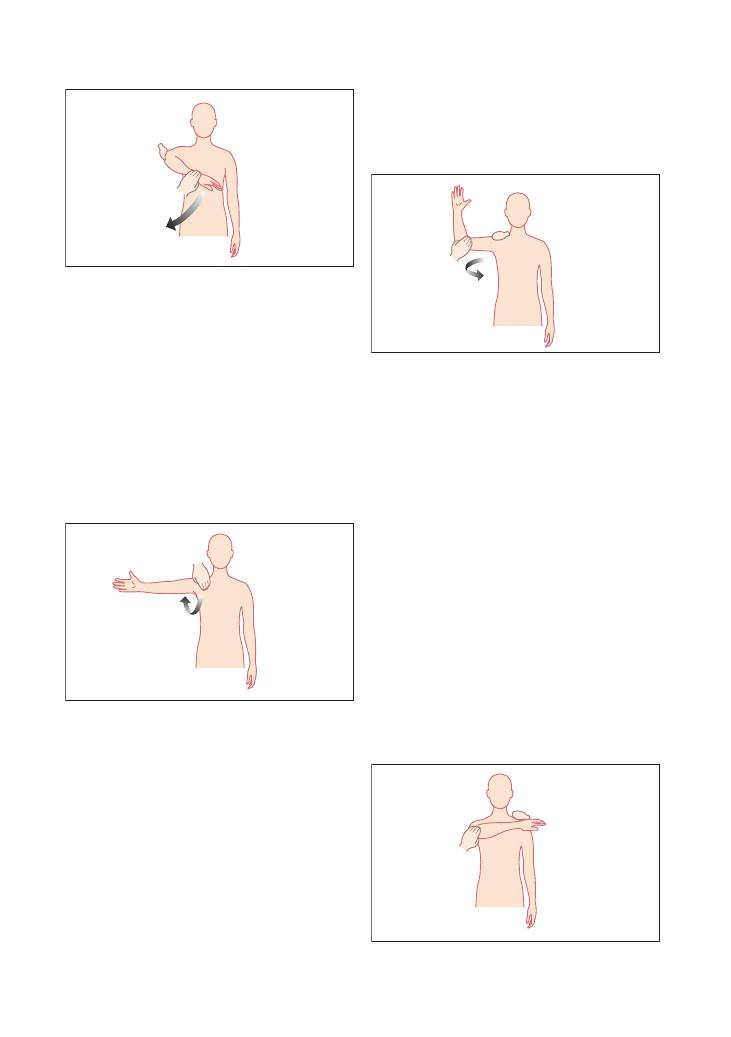

17. Shoulder, 80

18. Hand, 87

19. Hip, 93

20. Knee, 98

21. Confirming death, 105

Part 2: Histories

Top Tips, 107

22. General lethargy and tiredness, 109

23. Weight loss, 112

24. Chest pain, 115

25. Palpitations, 118

26. Cough, 122

Contents

27. Shortness of breath, 125

28. Haemoptysis, 128

29. Diarrhoea, 132

30. Abdominal pain, 137

31. Abdominal distension, 143

32. Haematemesis, 148

33. Rectal bleeding, 152

34. Jaundice, 155

35. Dysphagia, 158

36. Headache, 161

37. Loss of consciousness, 165

38. Tremor, 168

39. Dizziness, 172

40. Joint pain, 177

41. Back pain, 183

42. Pyrexia of unknown origin, 191

43. Ankle swelling, 195

44. Needlestick injury, 199

45. Preoperative assessment, 201

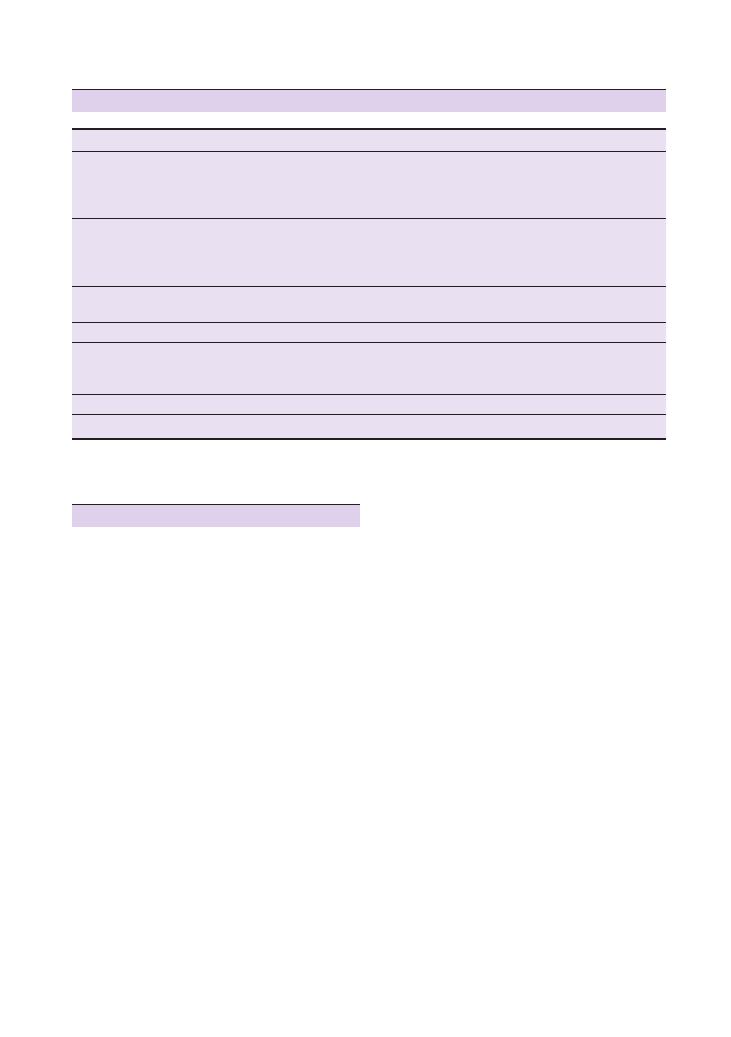

Part 3: Communication skills

Top Tips, 205

46. Breaking bad news, 208

47. Explaining medication, 211

48. Explaining a procedure, 215

49. Inhaler technique and asthma medication, 220

50. Exploring reasons for non-compliance, 222

51. Counselling for an HIV test, 225

52. Post mortem consent, 228

53. Explaining a DNAR (Do Not Attempt

Resuscitation) decision, 230

54. Explaining post-myocardial infarction

medication, 233

55. Dealing with an angry patient, 236

56. Carrying out a handover, 239

v

vi Contents

Part 4: Procedures

Top Tips, 243

57. Urinary catheterisation, 245

58. Insertion of nasogastric tube, 248

59. Venepuncture/phlebotomy, 252

60. Intramuscular injection, 254

61. Intravenous cannulation, 257

62. Intravenous drug administration, 260

63. Arterial blood gas analysis, 262

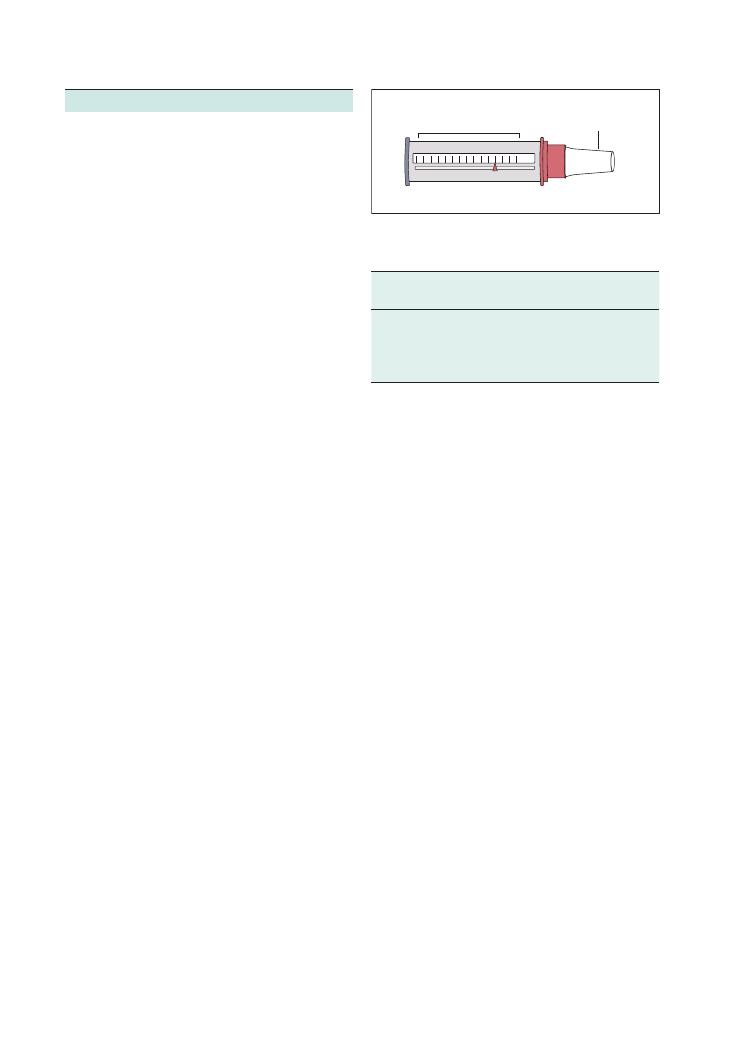

64. Measuring peak expiratory flow rate, 267

65. Performing and interpreting ECGs, 271

66. Scrubbing up in theatre, 276

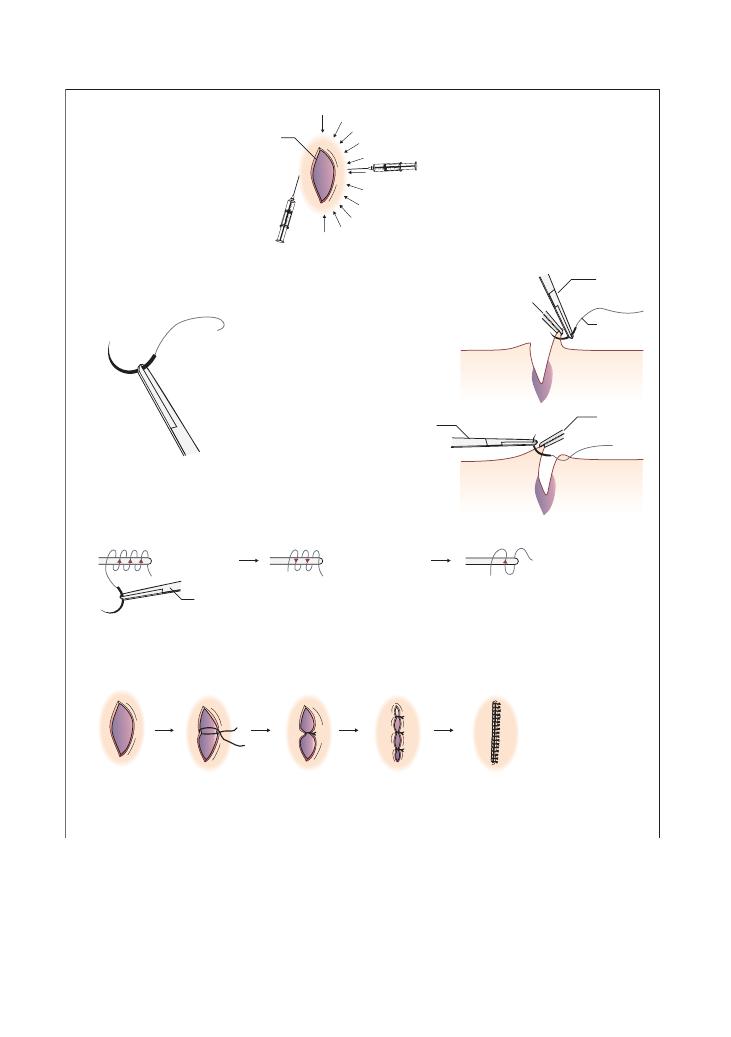

67. Suturing, 278

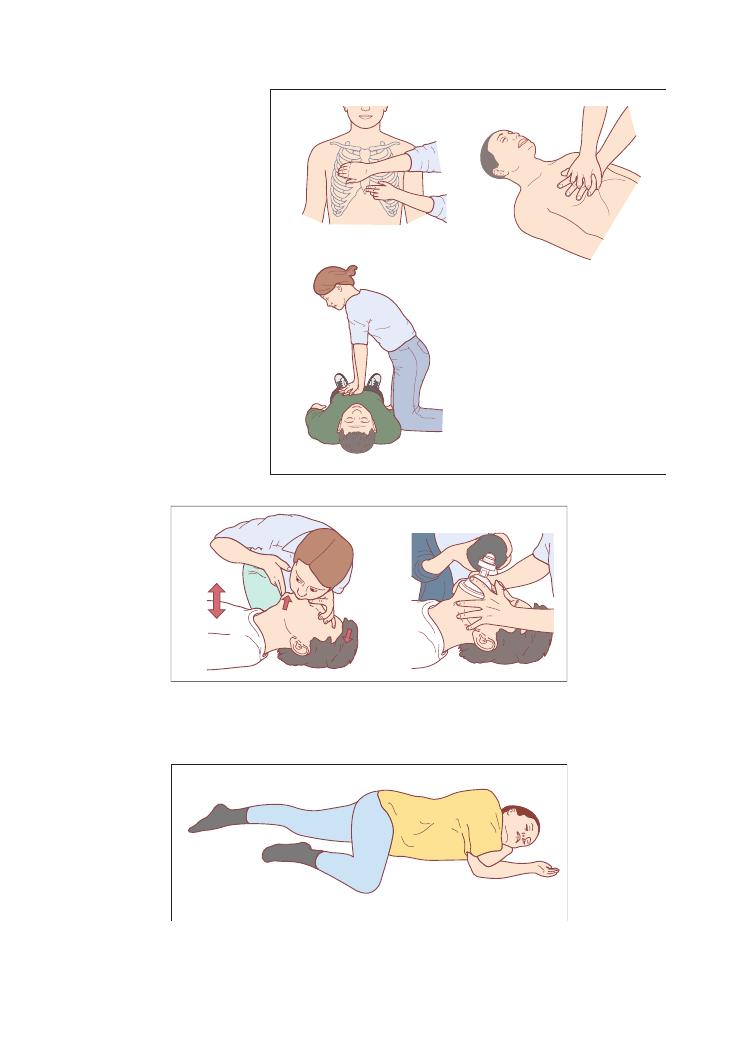

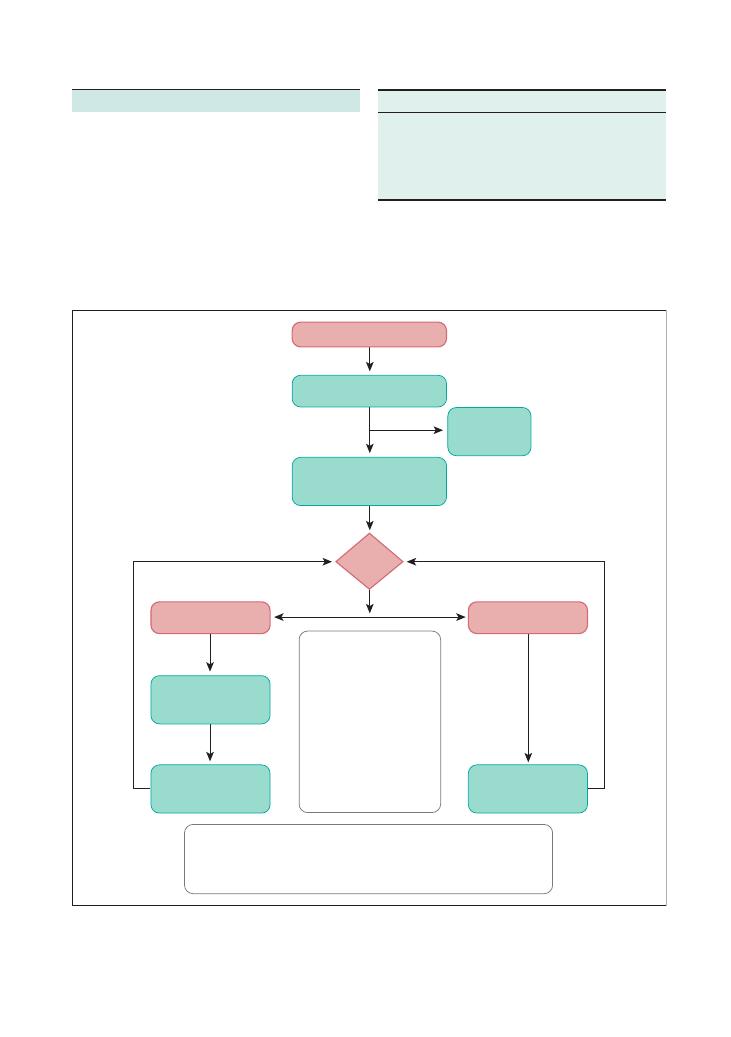

68. Basic life support, 282

69. Advanced life support, 286

70. Completing a death certificate, 291

Index, 293

Companion website

This book is accompanied by a companion website:

featuring:

• Downloadable checklists from the book

• Survey showing which OSCE stations have a high chance of appearing in finals

vii

Contributors

We are grateful to the following doctors and medical

students for their contributions to this book.

Contributors to the chapters

Shifa Rahman

Manpreet Sahamey

Ruth-Mary deSouza

Gillian Landymore

Ravi Naik

Contributors to the medical school tables

Saba Ali

Ali Alidina

Nina Arnesen

Svitlana Austin

James Best

Kerry Bosworth

Lisa Burton

Sangeetha Chandragopal

Emily Clark

Laura Clarke

Rebecca Critchley

Nicola Davis

Ruth-Mary deSouza

Pippa Dwan

Matthew Everson

Martin Fawcett

Clare Fernandes

Lyndsey Forbes

Rachel Friel

Ushma Gadhvi

Harminder Gill

Catherine Hatzantonis

Elizabeth Hockley

Laura Hopkins

Towhid Imam

Zara Jaulim

Michelle Kameda

Jennifer Kelly

Pamini Ledchumykanthan

Almas Malik

Sathiji Nageshwaran

Ravi Naik

Sania Naqvi

Siva Nathan

Allan Nghiem

Gary Nicholson

Clarissa Perks

Anna Rebowska

Elissa Scotland

Charly Sengheiser

Nadir Sohail

Charlotte Spilsbury

Sarah Thompson

Elizabeth Khadija Tissingh

Christine Wahba

John Wahba

Siobhan Wild

Anna Willcock

Ahila Yogendra

viii

Acknowledgements

We are immensely grateful to the multitude of friends

and colleagues who helped us with various aspects of

this book. They include the following:

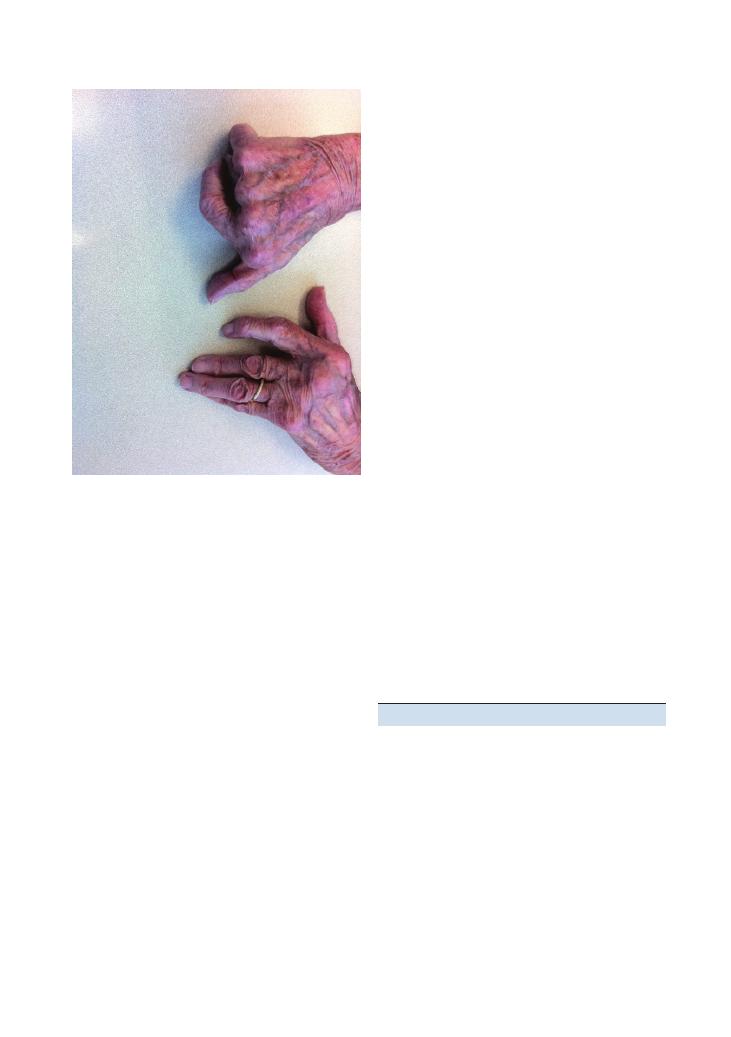

• All of the patients who kindly permitted us to use

their photos in this book

• All the staff at Eversley Medical Centre who assisted

us with finding patients with signs that could be pho-

tographed – specifically Dr John Chan, Dr Colette

Boateng and practice nurses Pauline Kearney and

Cheryl Mirador

• Dr Vivek Chayya and Dr Alison Barbour for their

advice on gastroenterology

• Dr Sara Khan, Dr Kartik Modha, Dr Nazia Khan

and Dr Siva Nathan for their help in recruiting

contributors

• Saiji Nageshwaran and Vaitehi Nageshwaran for

reviewing several of the chapters

• Mr Ian Skipper for his unparalleled IT expertise and

assistance

• Dr Khalid Khan for helping us develop the idea from

which this book was derived, and for reviewing, proof-

reading and critiquing the final manuscript

• All of our parents and families, without whose

patience and support this project would never have

succeeded

We are also grateful to the Medical Womens Federa-

tion, Tiko’s GP Group and the Muslim Doctors Asso-

ciation for helping us recruit contributors through

their organisations.

ix

Preface

The student begins with the patient, continues with the

patient, and ends his studies with the patient, using

books and lectures as tools, as means to an end.

Sir William Osler

Few will disagree that the recent overhauls in medical

training, together with higher numbers of medical

students being trained, has made medicine far more

competitive than before. Medical students today have

to make definitive career choices much earlier on than

they would have had in years gone by, and to start

building a portfolio of achievements such as audits

and publications very early on at medical school. Time

has become even more precious than it was before, and

it is understandable that medical students today will

opt for concise focused textbooks rather than sprawl-

ing prosaic texts, some of which have been used over

many generations and gained an almost legendary

status.

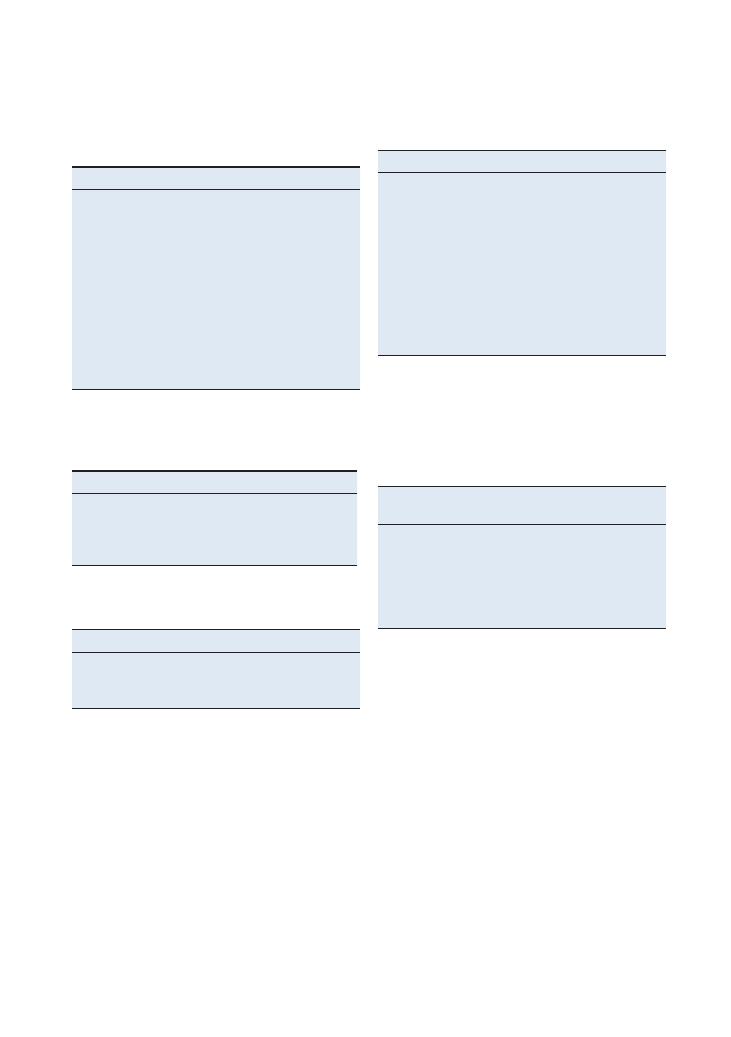

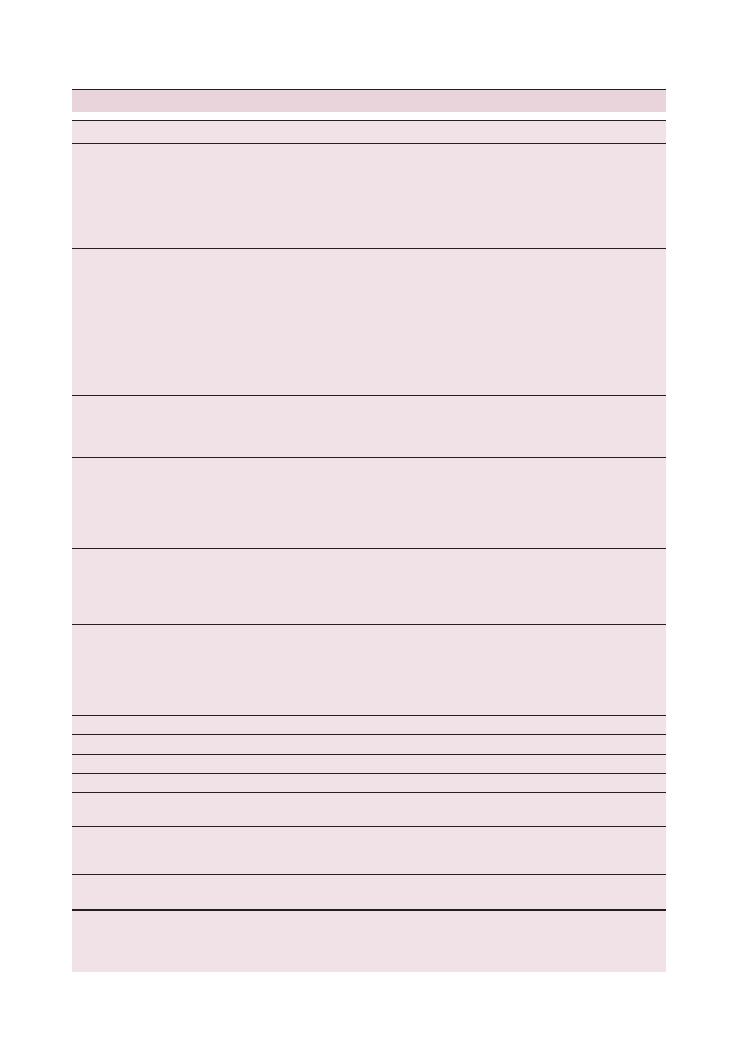

This book is perhaps unique in that it has been

written by a group of doctors who range from those in

career-grade posts who have completed postgraduate

training and have been OSCE examiners themselves, to

those who have very recently sat their finals. We have

collated our experiences to create a textbook that we

have made as focused, easy to read and, above all, as

exam-orientated as possible. While doing this, we have

worked hard to ensure that we include everything nec-

essary not only to pass finals, but also to achieve excel-

lent marks and hopefully merits and distinctions.

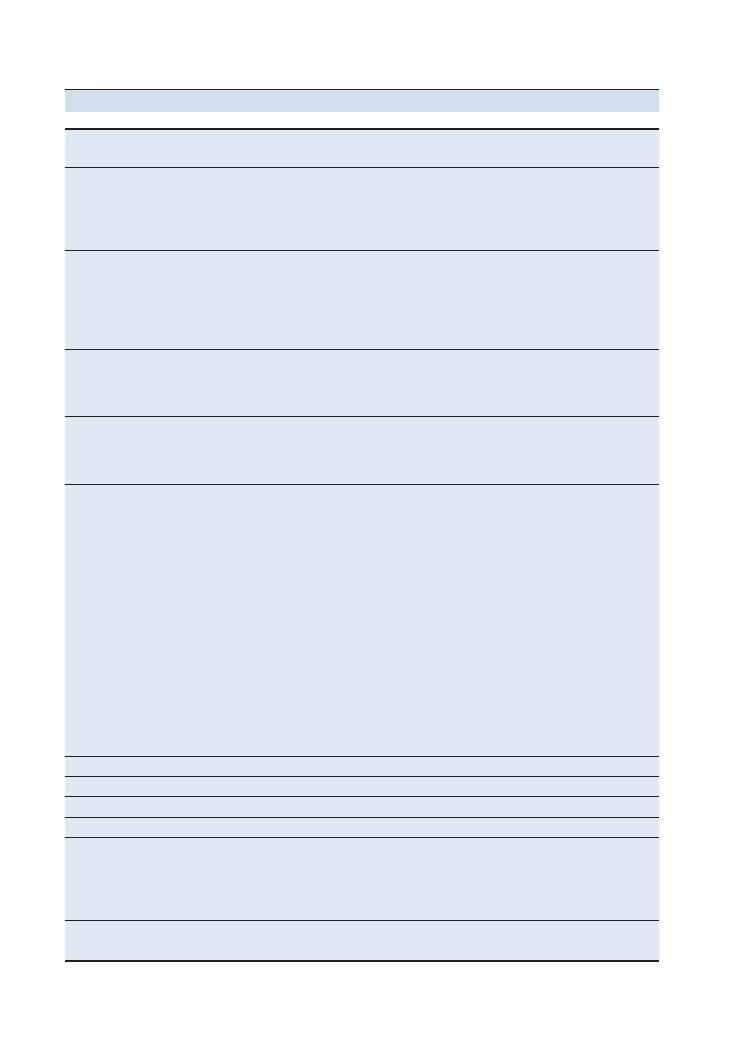

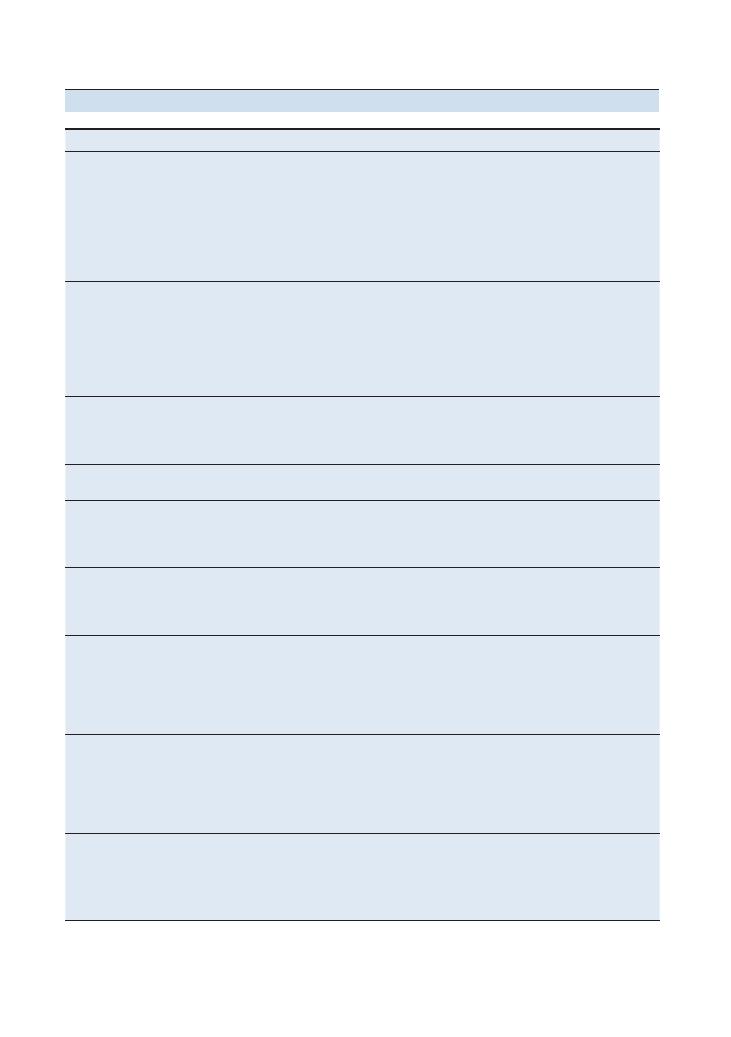

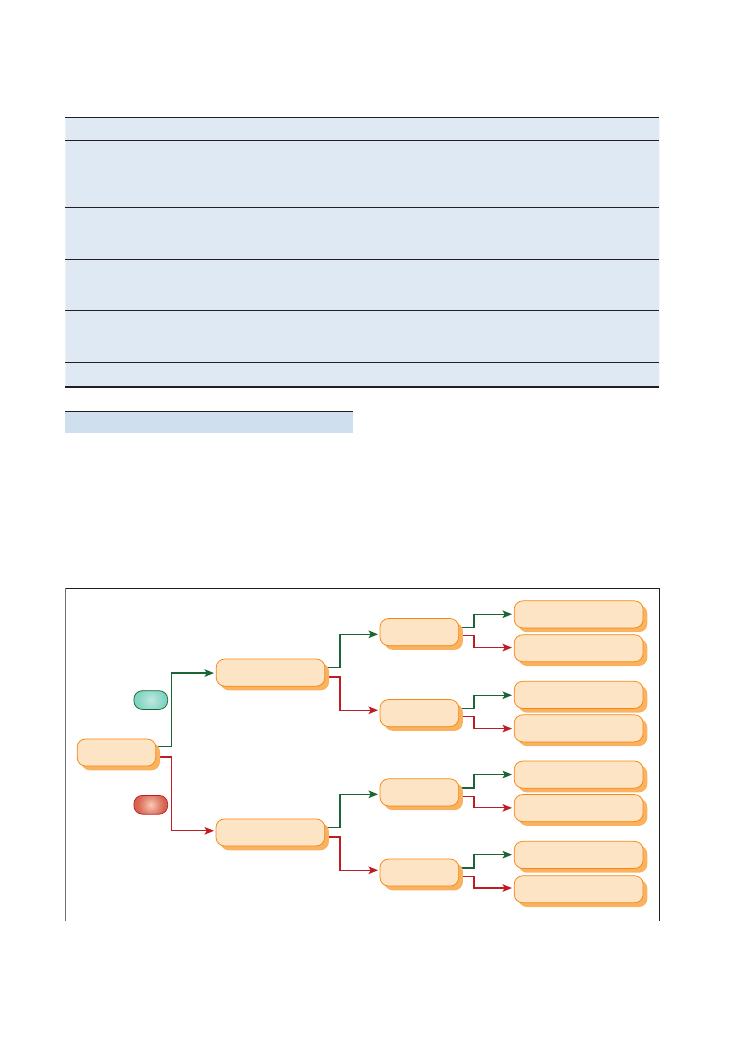

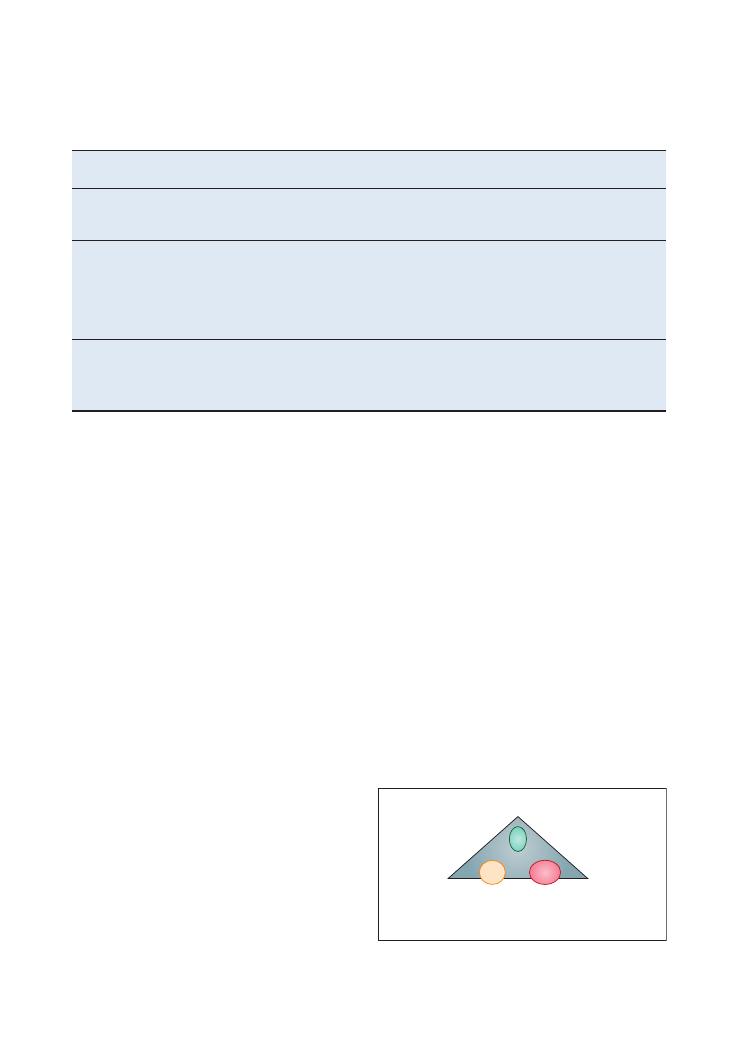

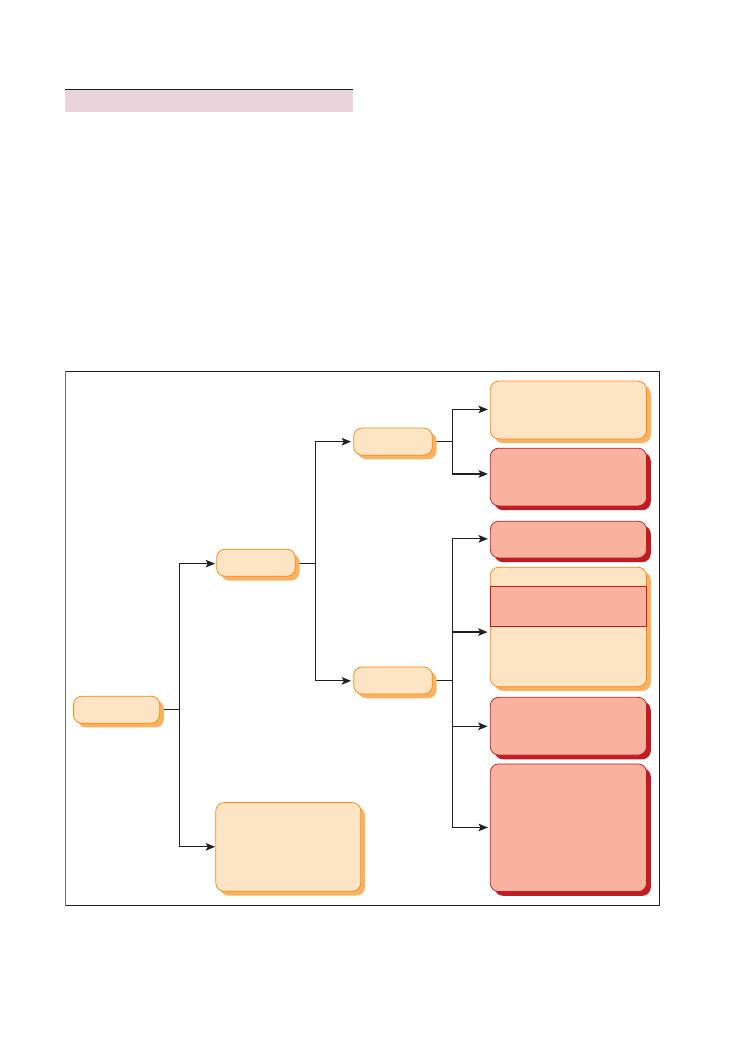

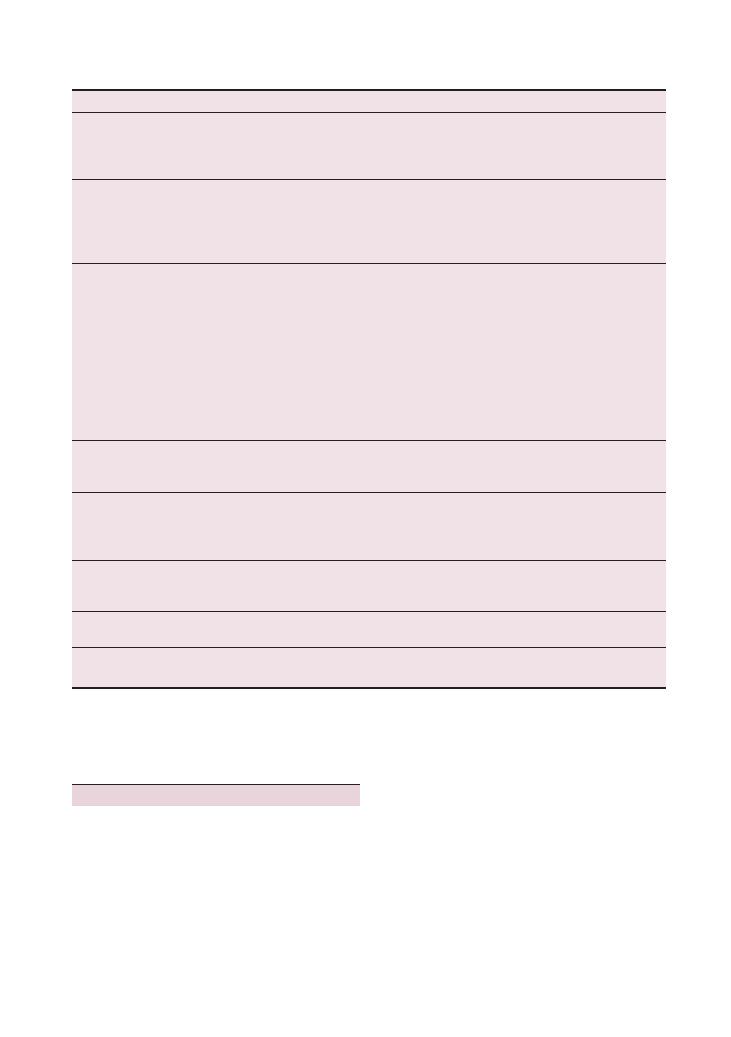

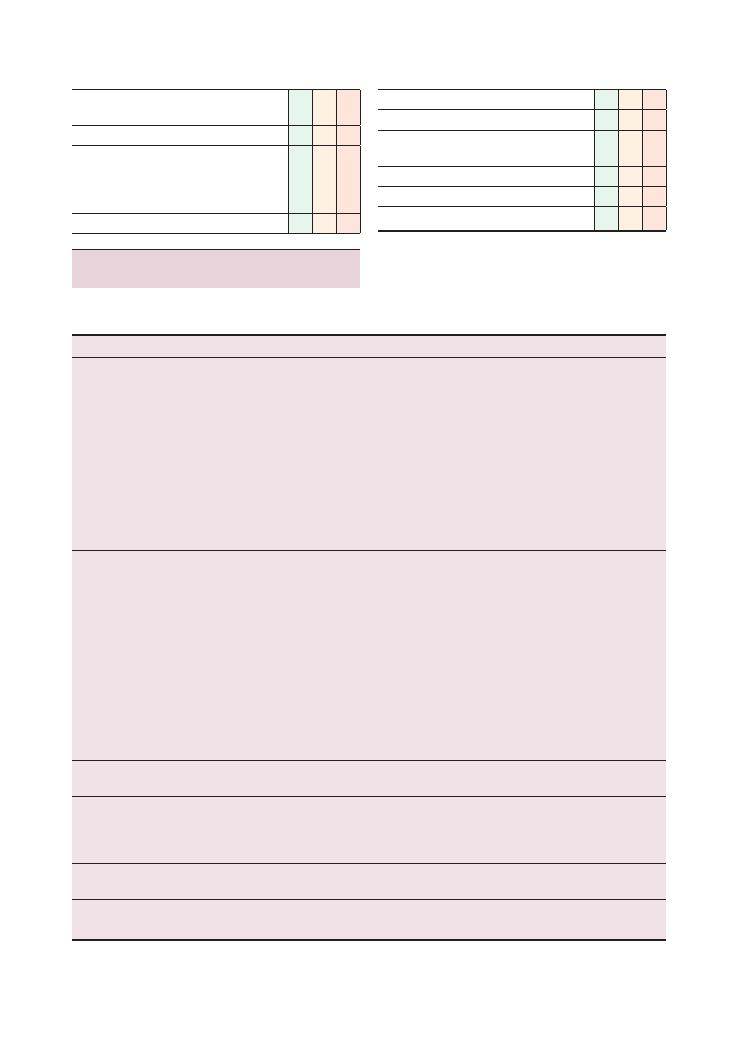

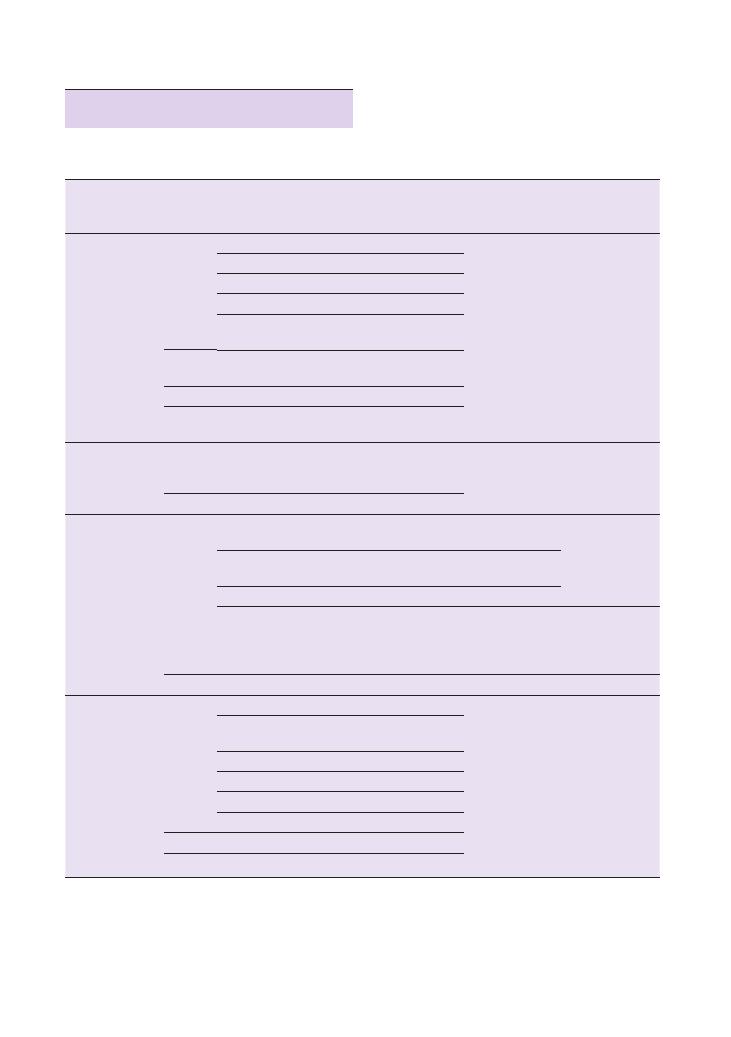

The structure is based on four sections – clinical

examinations, histories, communication skills and pro-

cedures. At the beginning of each of these sections,

there is a ‘Top Tips’ page that has generic advice for any

OSCE station of that section which would help you

boost your marks and performance regardless of what

the station is.

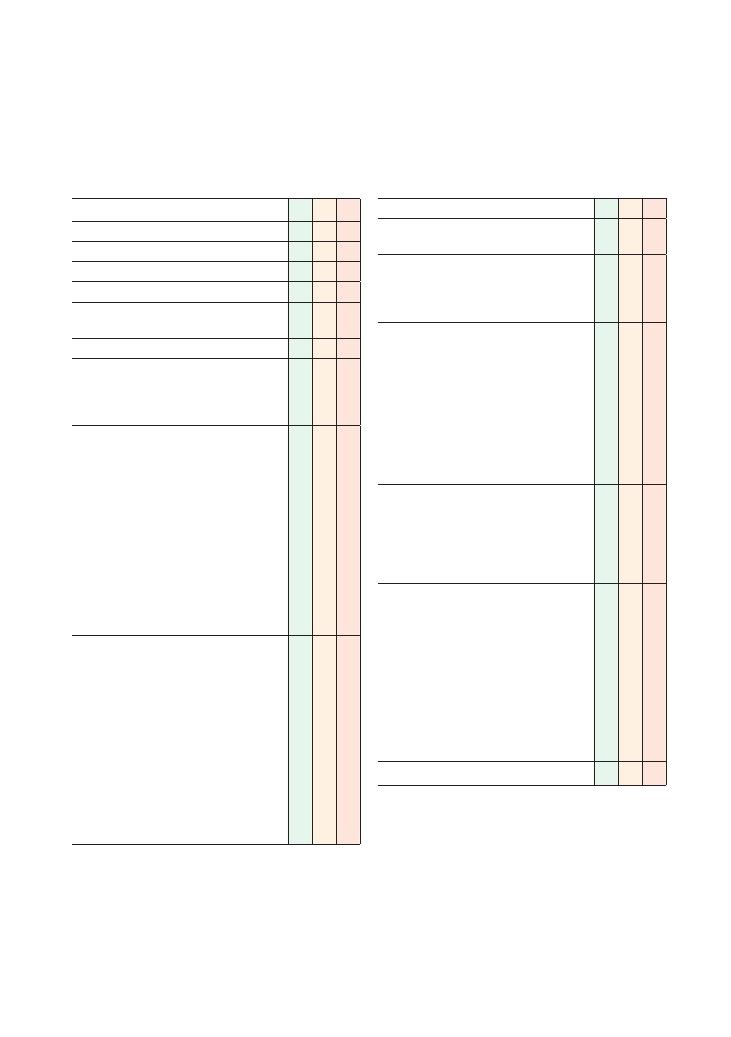

Each section is divided into chapters based on the

stations we feel are most likely to appear in OSCEs at

medical schools. Practice makes perfect – and more so

in OSCEs than in any other form of assessment. That

is why we have started each chapter with a checklist of

items reflecting the areas you are likely to be marked

on. You should use these to perfect and consolidate your

routines, and also when practising OSCEs with friends

and on patients. You should ideally do this in a pair or

a group of three, with one student doing the station as

a candidate and one allocating mock ‘marks’ using the

checklists to assess the candidate’s performance.

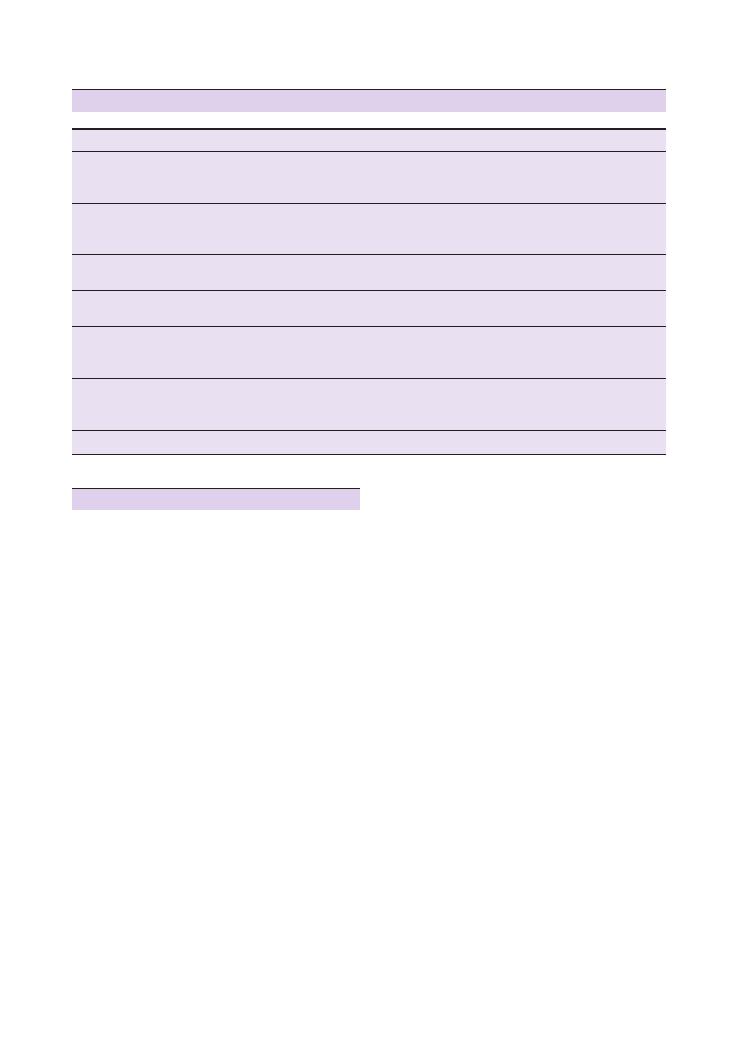

Following this in each section, we have included

tables that summarise the most common conditions

that are likely to present in finals OSCEs. We have

ensured that the information on the conditions in these

tables is as focused and exam-oriented as possible.

There is also a ‘Hints and tips for the exam’ section in

which we have summarised key advice and common

pitfalls that finalists tend to make.

We hope that this book will make your revision not

only thorough and focused, but also enjoyable. We have

spent a lot of time working with our publishers to make

the text as vibrant, colourful and easy to read as pos-

sible, with a plethora of tables, illustrations and photos

that will not only make it easy to remember key

ideas and principles, but also make the topic more

interesting.

We wish you the very best of luck with your finals

OSCEs, and hope that you find this book both enjoy-

able and useful.

Hamed Khan

OSCEs for Medical Finals, First Edition. Hamed Khan, Iqbal Khan, Akhil Gupta, Nazmul Hussain, and Sathiji Nageshwaran.

© 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Published 2013 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

1

Part 1: Examinations

Top tips

Do:

• Memorise the steps: The most important thing that

OSCE examiners are looking for is an ability to carry

out a full examination with reasonable technique and

speed. At finals level, you will be forgiven for missing a

few signs, and the vast majority of the marks on the

mark schemes are allocated for going through the

motions and doing all the ‘steps’. In contrast, at post-

graduate level, for example for the MRCP exam, you

would be expected to pick up all the major signs, and

be penalised heavily for missing them.

• Always suggest a number of possible differential

diagnoses: Very few doctors will be able conclusively

to put their finger on a diagnosis after examining a

patient for 10 minutes without a history. Offering a

number of differentials means that you have a higher

chance of at least mentioning the correct one, even if it

is not at the top of your list. It will also show a healthy

awareness of your own limitations.

• Practise, practise and practise: The best way to do

this is by seeing patients, having a friend to assess you

using our checklists and then getting critical (but con-

structive) feedback from them. Swapping roles and

watching colleagues examine is more useful than most

students think, as it will reinforce the steps of the exam-

ination, and you may see them use techniques and skills

that you would not otherwise have thought of. Doing

all the major examinations should become such a

normal routine for you that you can do it without

thinking about what the next step will be – just like

riding a bicycle or driving a car.

Don’t:

• Don’t be nervous: Most people have problems in

OSCEs not because of poor technique or knowledge,

but because of anxiety and nervousness. Don’t be over-

whelmed by the occasion, and don’t be intimated by an

examiner’s grilling. You will find it much easier to focus

on your technique and findings if you are relaxed, and

most examiners only grill students who are doing well,

as they do not waste their breath on those whom they

have decided are a lost cause!

• Don’t worry about minutiae: Medicine is not an

exact science, and different doctors have different ways

of examining patients, most of which yield the right

conclusions. At undergraduate level, all the examiners

are looking for is a decent, fluent technique that appears

to be well practised. Don’t spend ages trying to figure

out exactly how much the chest should expand, or

whether the cricoid–sternal notch distance is three

finger breadths or four.

• Don’t hurt the patient: This is the only unforgivable

sin in the OSCE. Its always a good idea to start your

examination by asking if the patient is in pain anywhere,

and reassuring them that if you unintentionally cause

pain during the examination, you will be happy to stop.

Students often have a tendency to ignore patients saying

‘Ouch!’ and pretending that they have not heard it, but

this is definitely the worst thing you can do. If you do

cause pain, acknowledge it immediately, apologise unre-

servedly and offer to stop – both examiners and patients

will appreciate your honesty and professionalism.

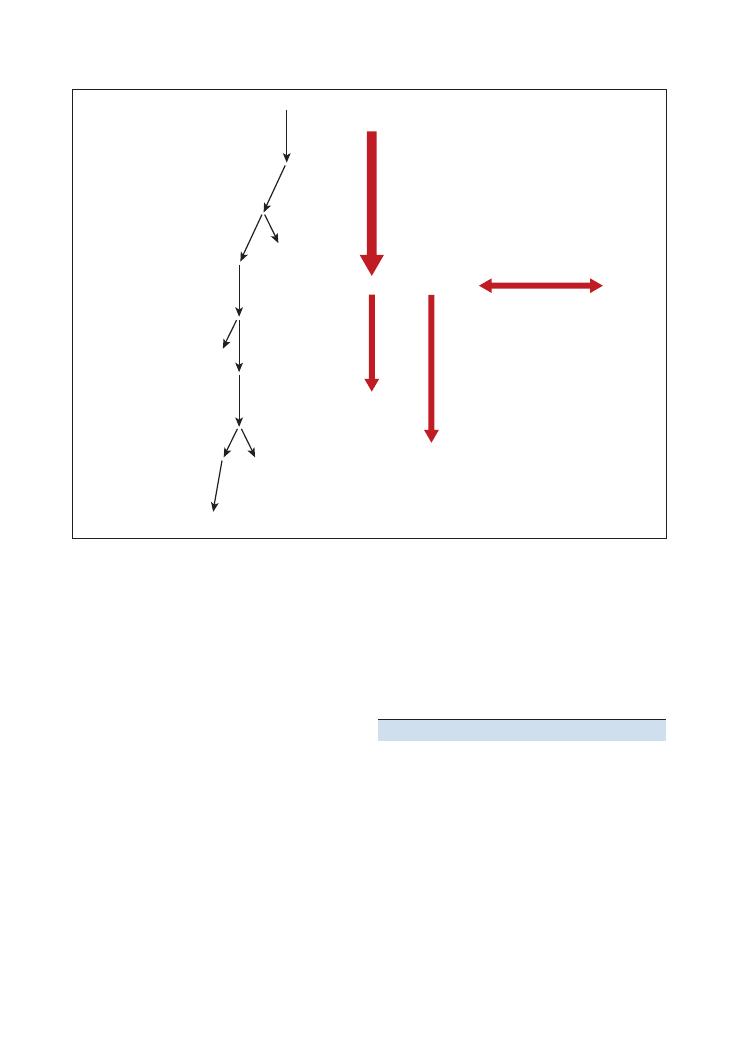

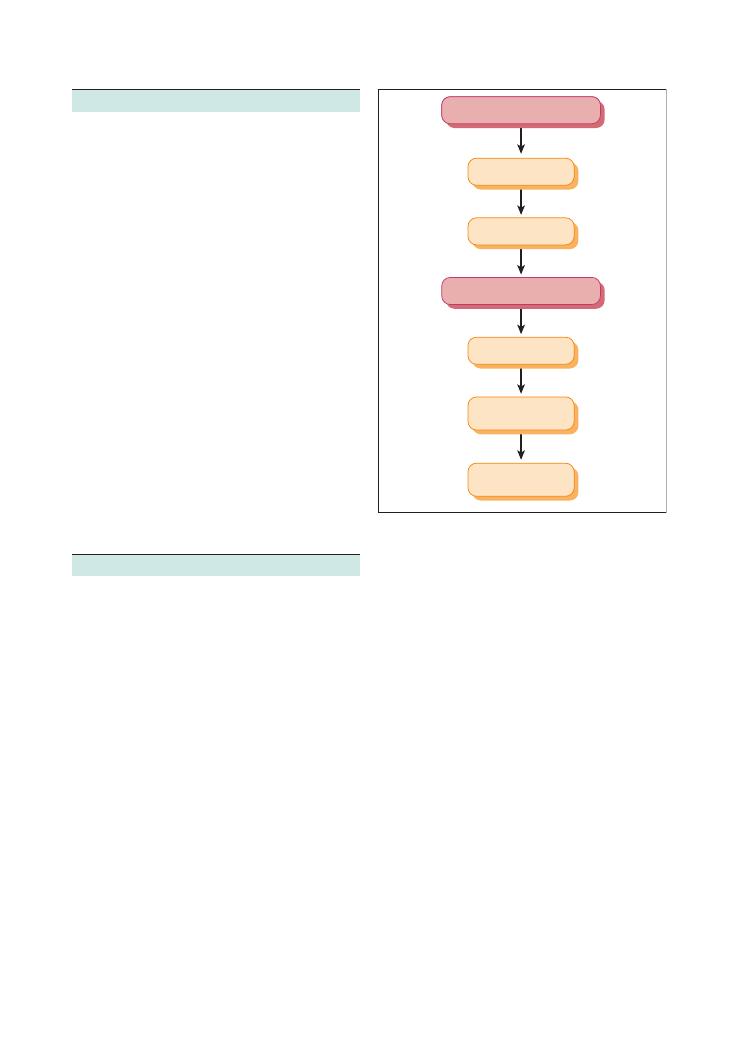

Generic points for all examination stations

HELP:

H: ‘Hello’ (introduction and gains consent)

E: Exposure (nipples to knees/down to groins)

L: Lighting

P: Positions correctly (supine), asks if patient is in any

pain

Washes hands

Inspects from end of bed for paraphernalia

Inspects patient (scars, etc.)

Thanks patient

Offers to help patient get dressed

Washes hands

Presents findings

Offers appropriate differential diagnosis

Suggests appropriate further investigations and

management

For joints only: Look

→ Feel → Move → Active/

passive/resisted

2

1 Cardiovascular

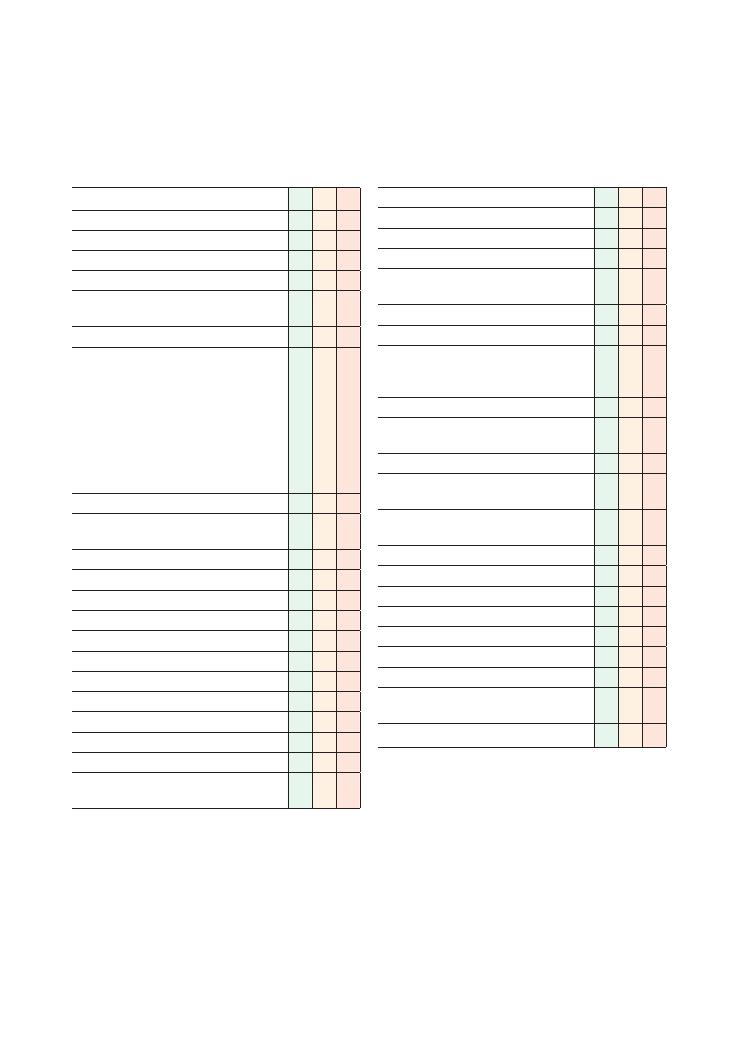

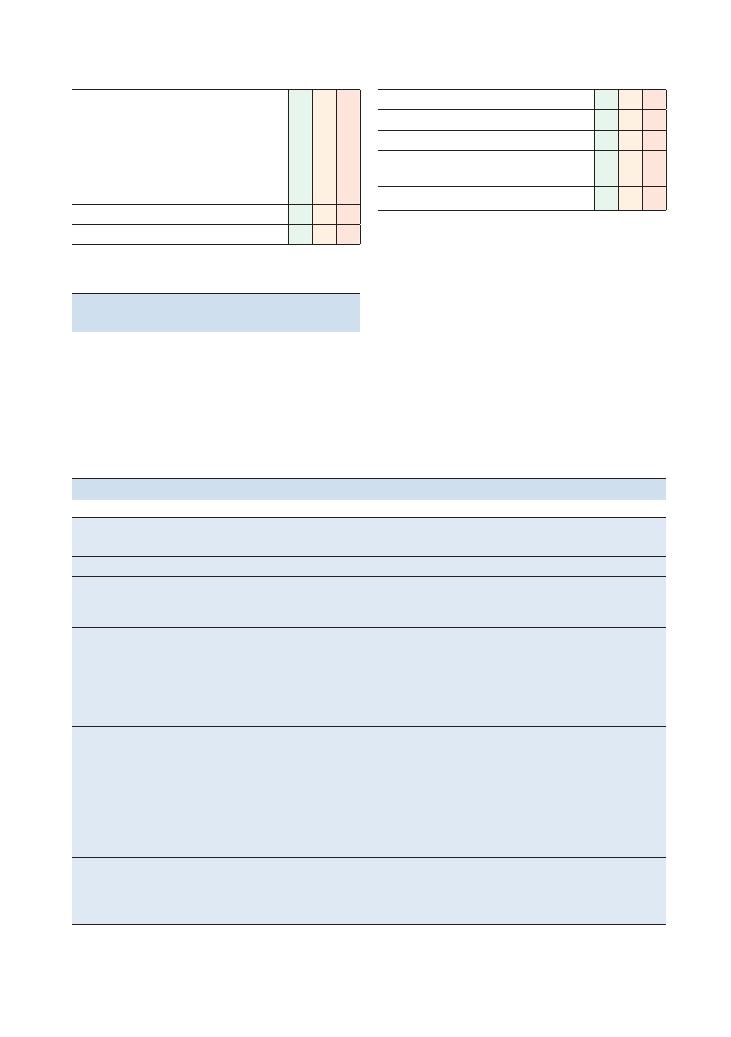

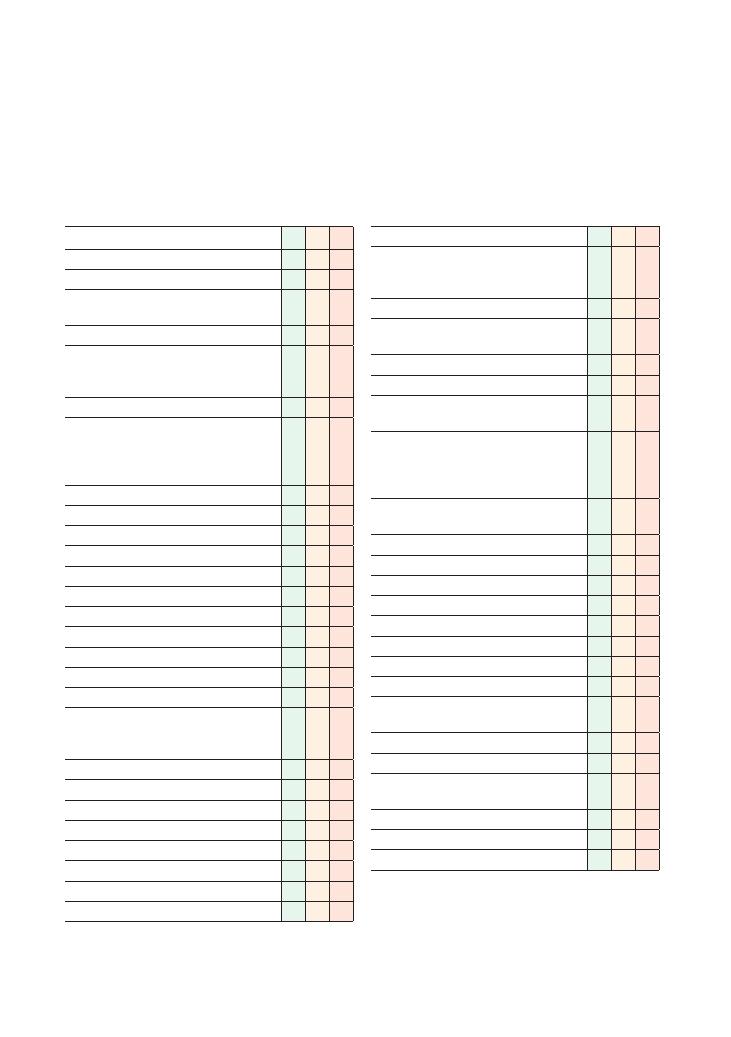

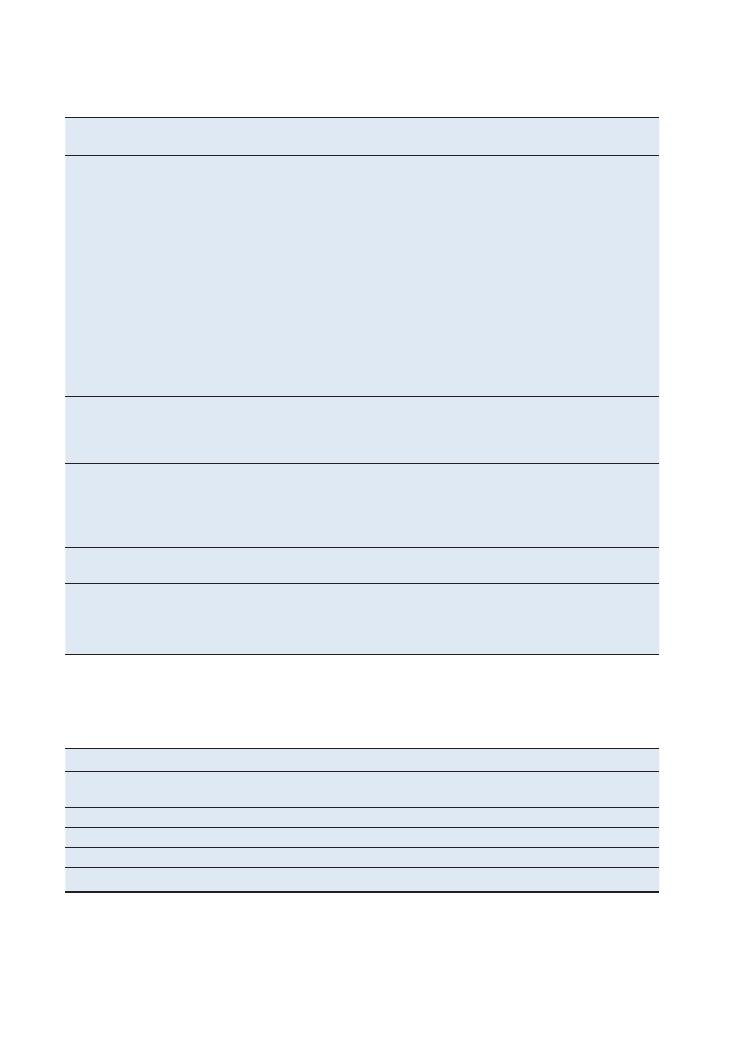

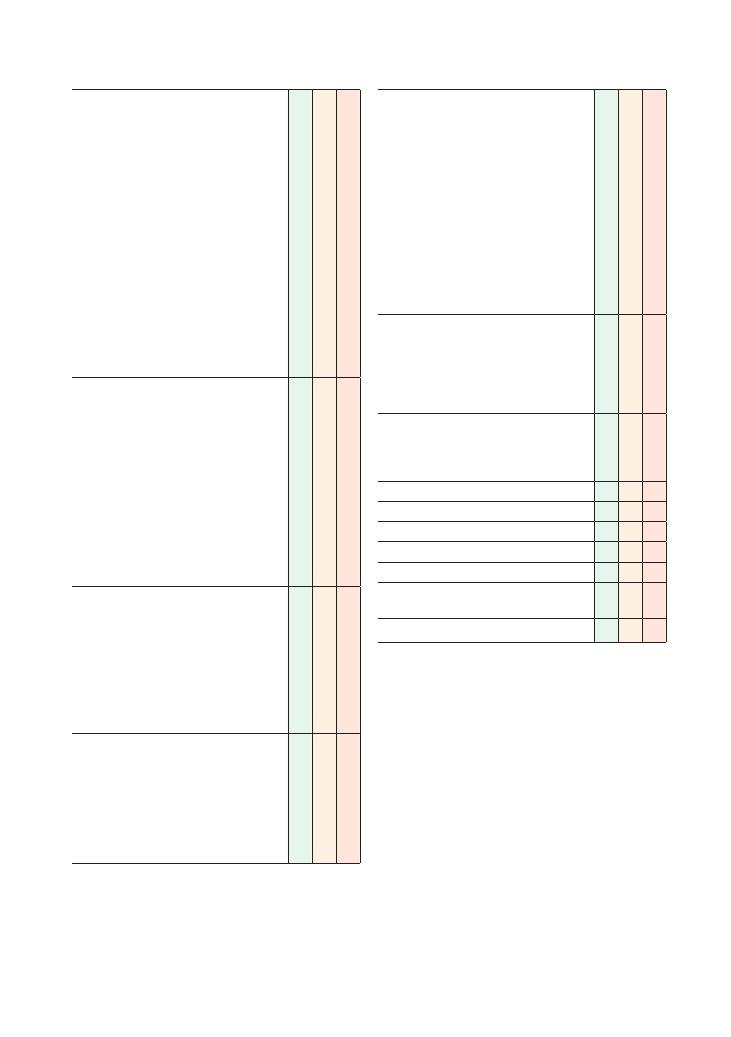

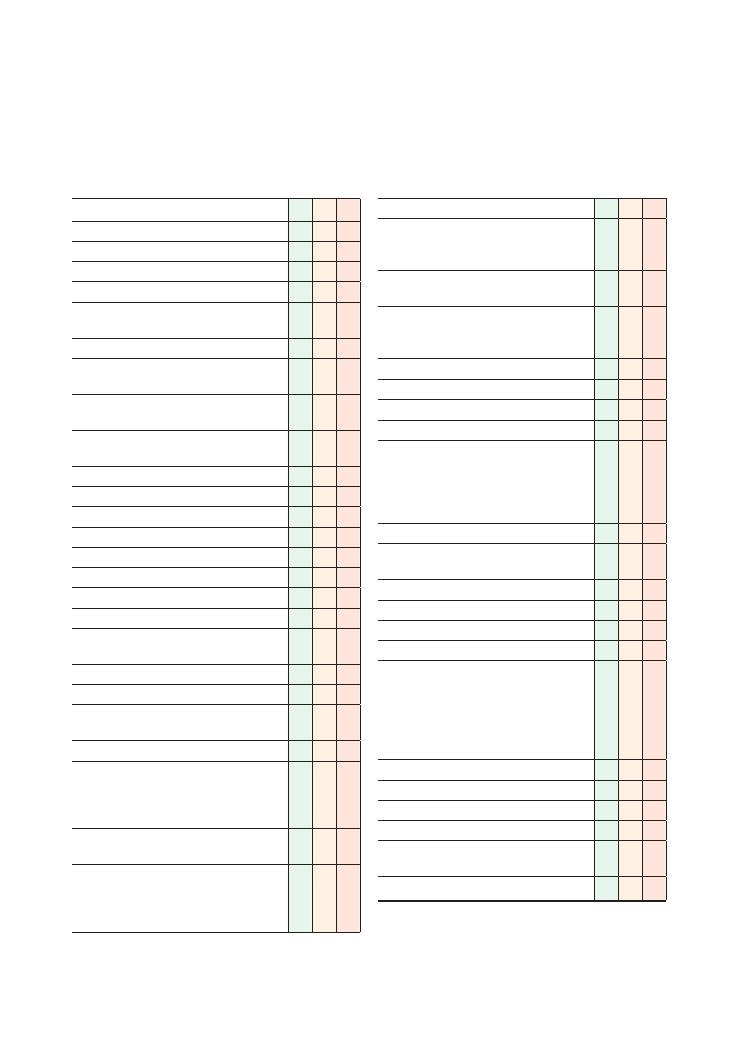

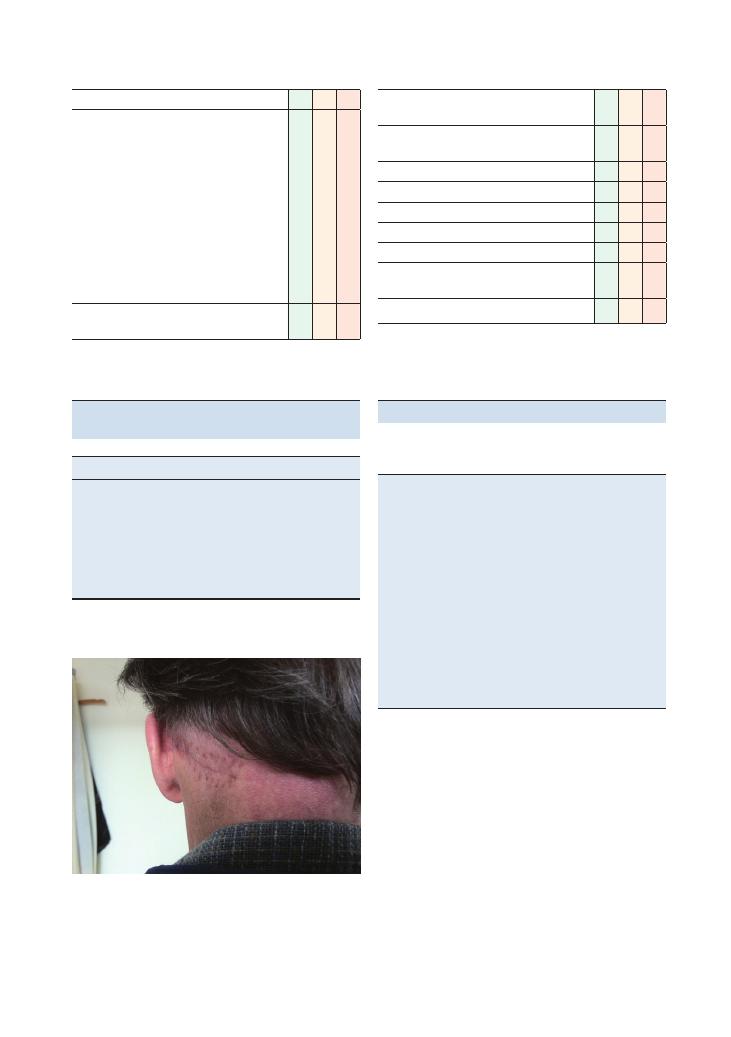

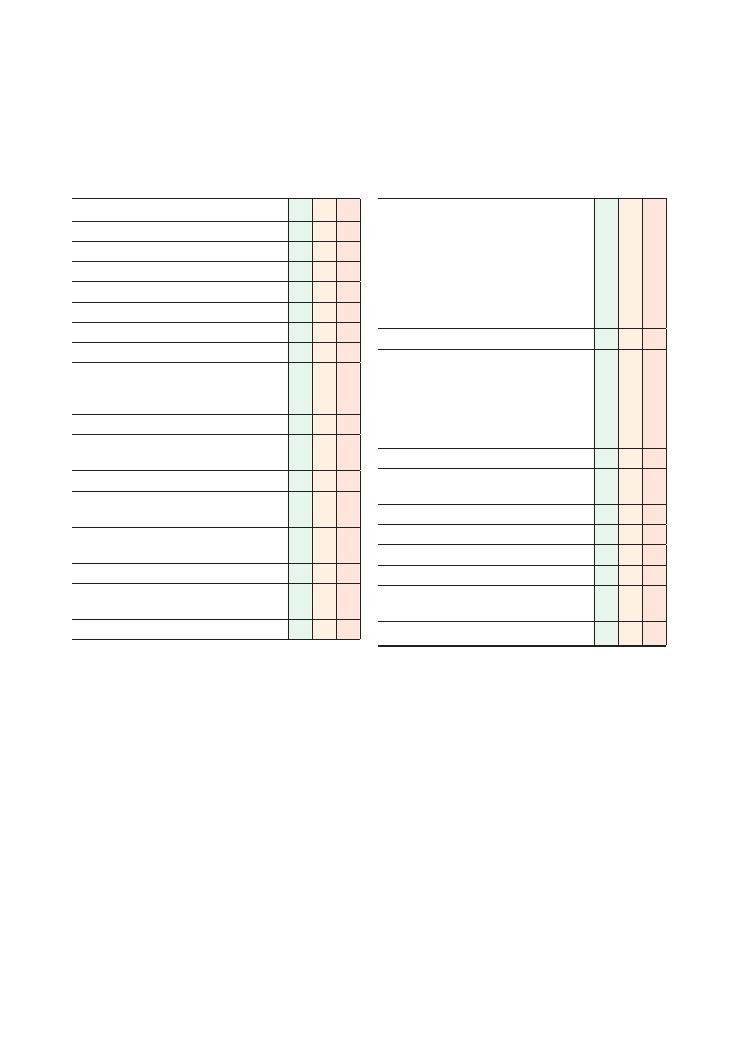

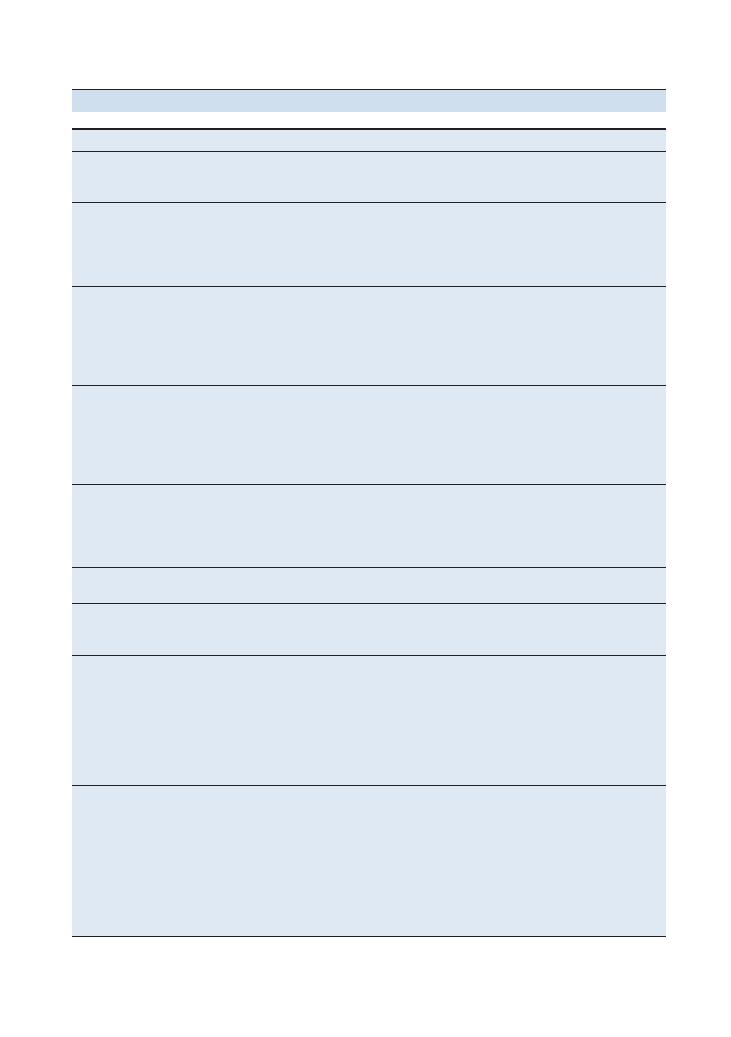

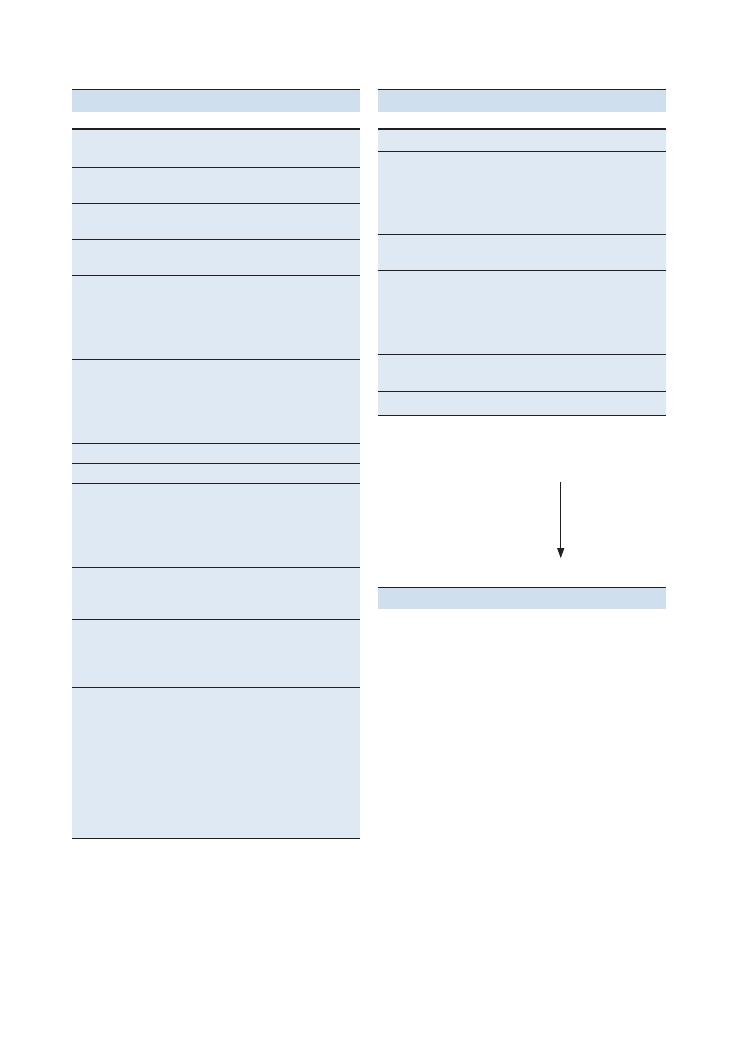

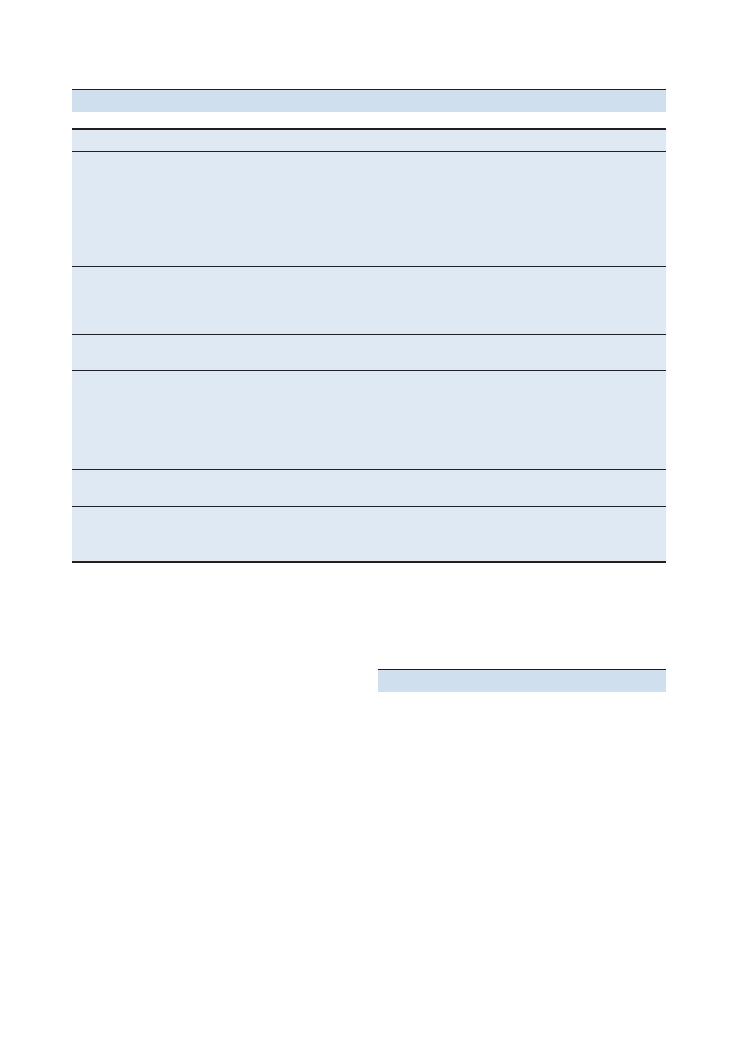

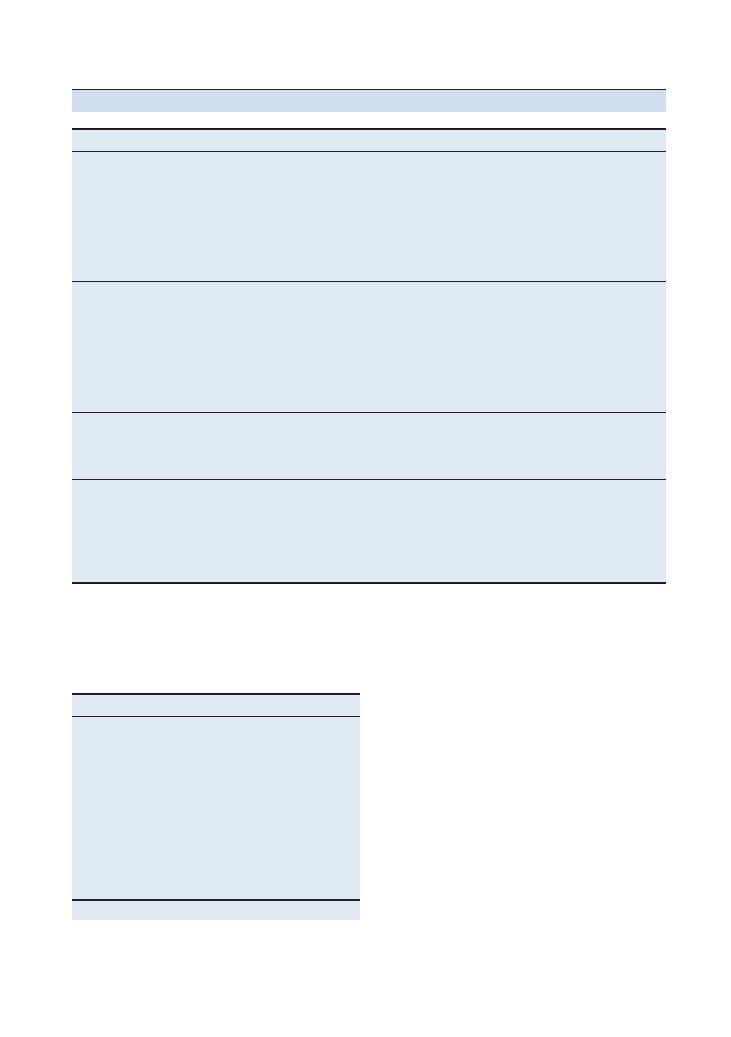

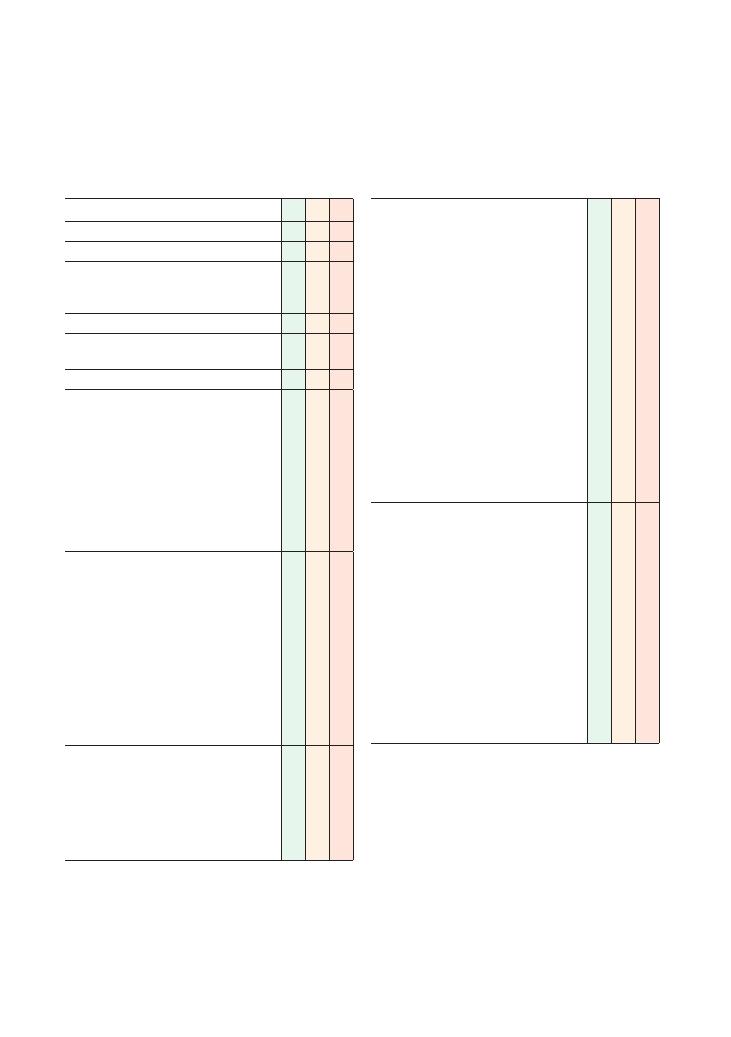

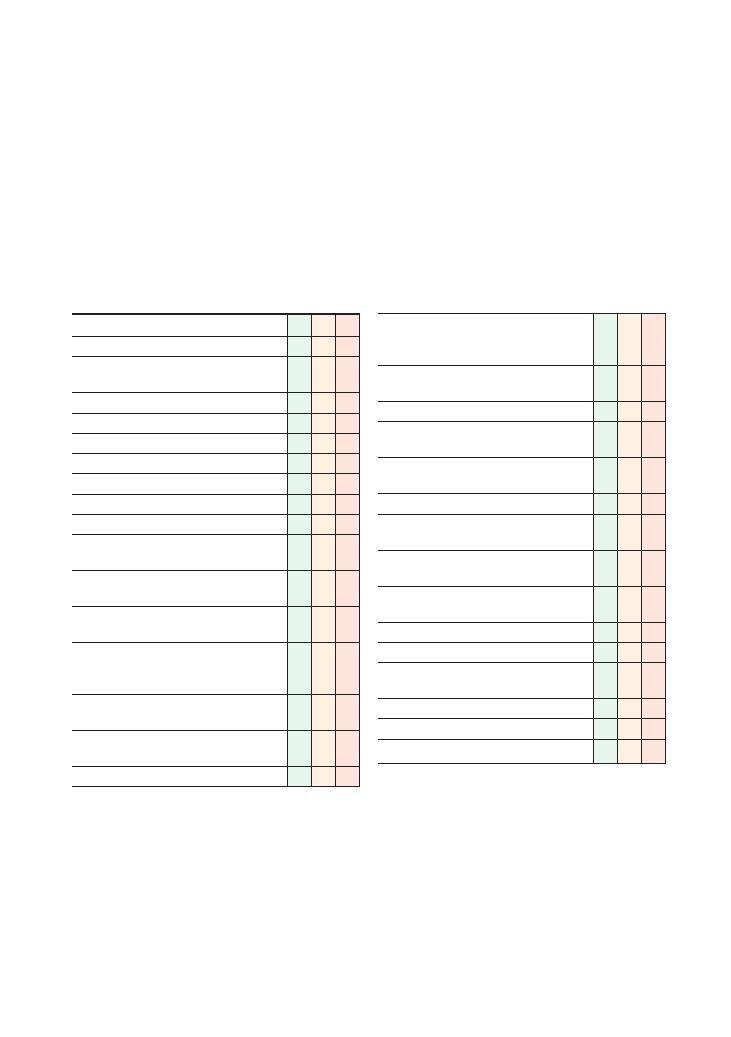

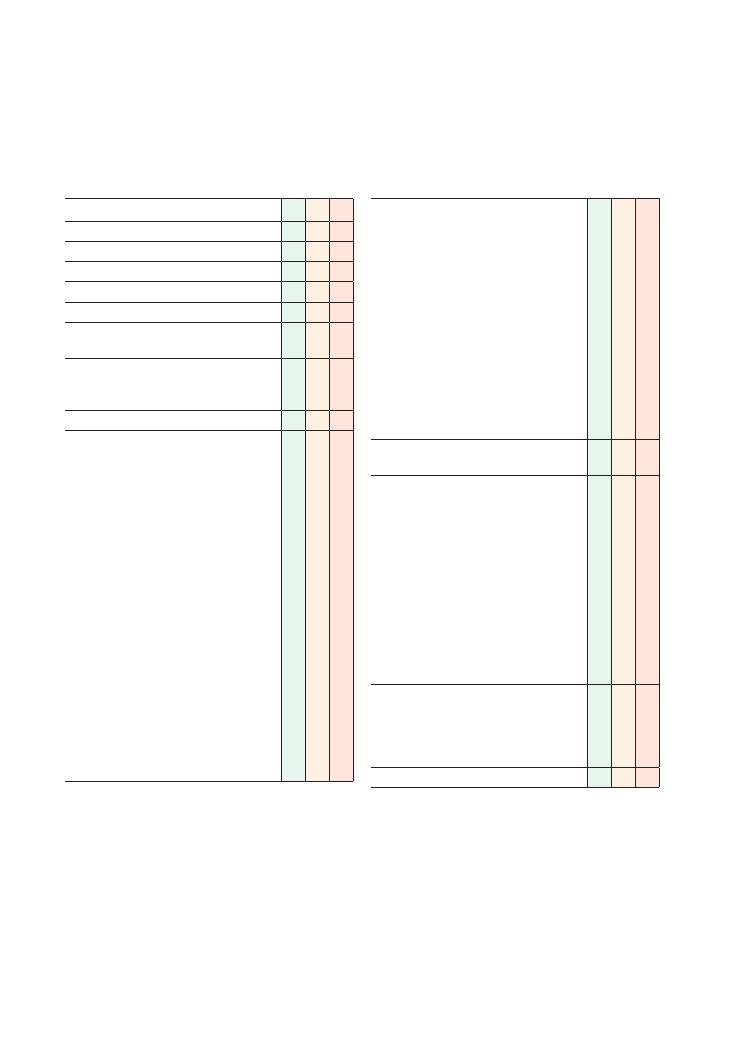

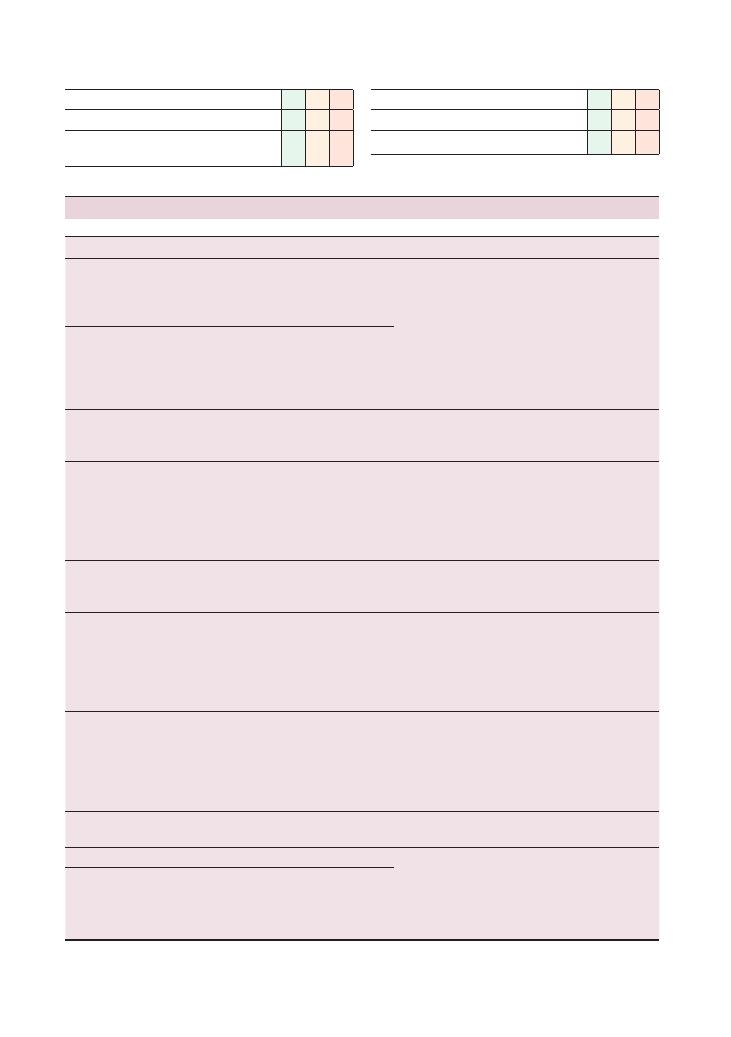

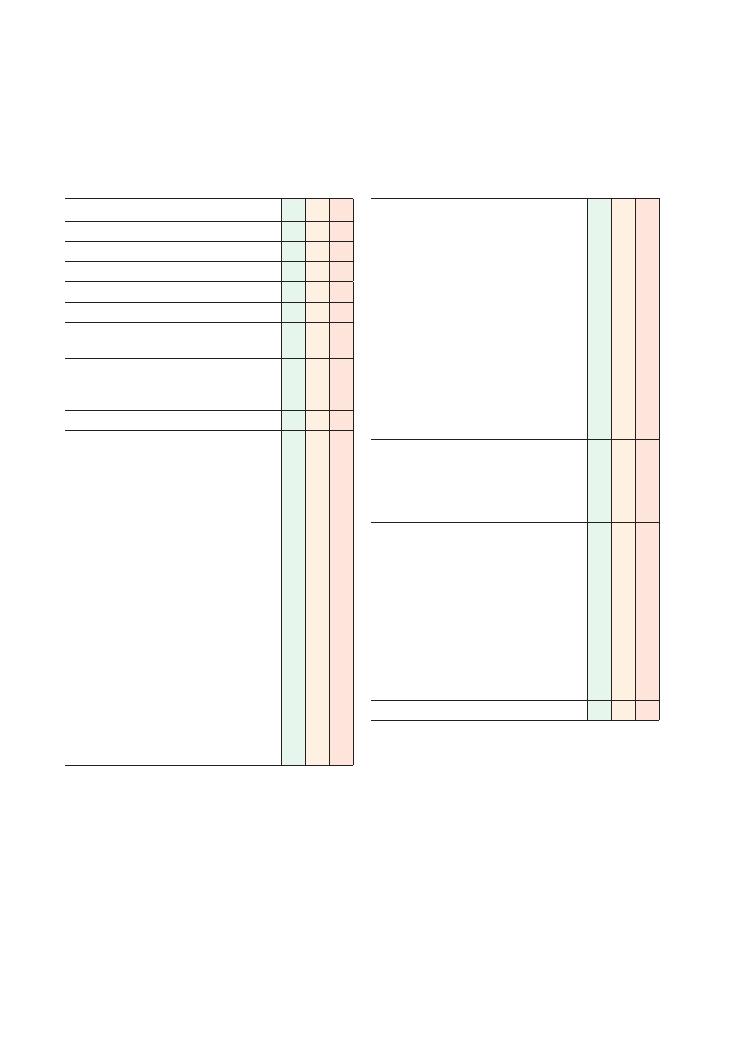

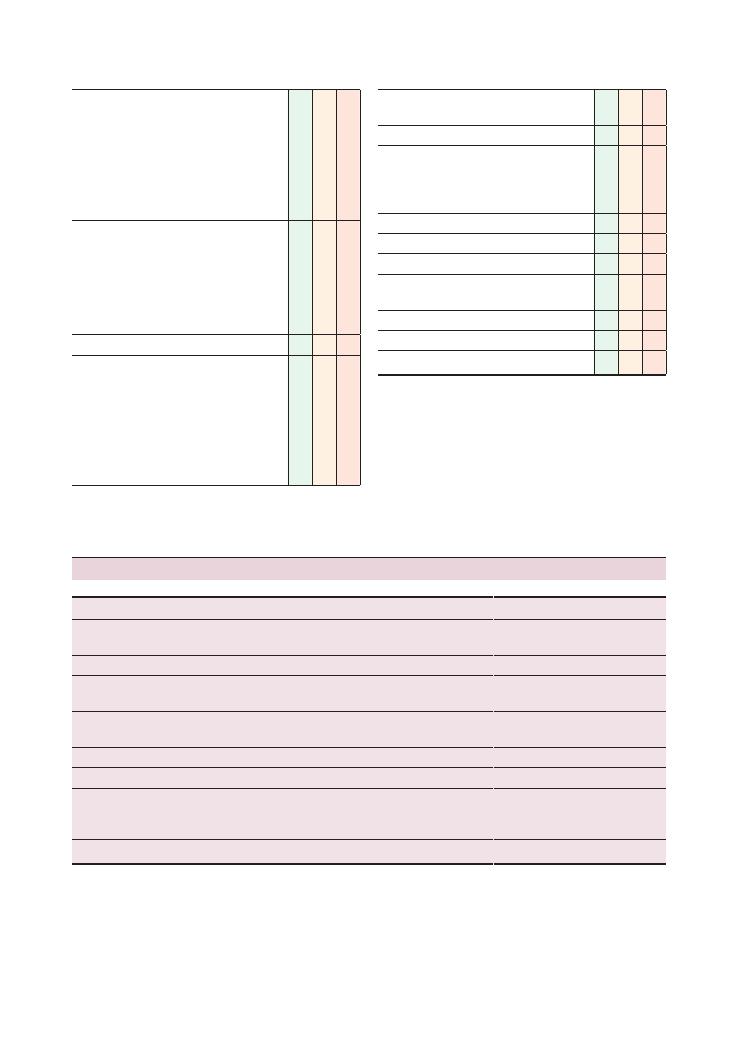

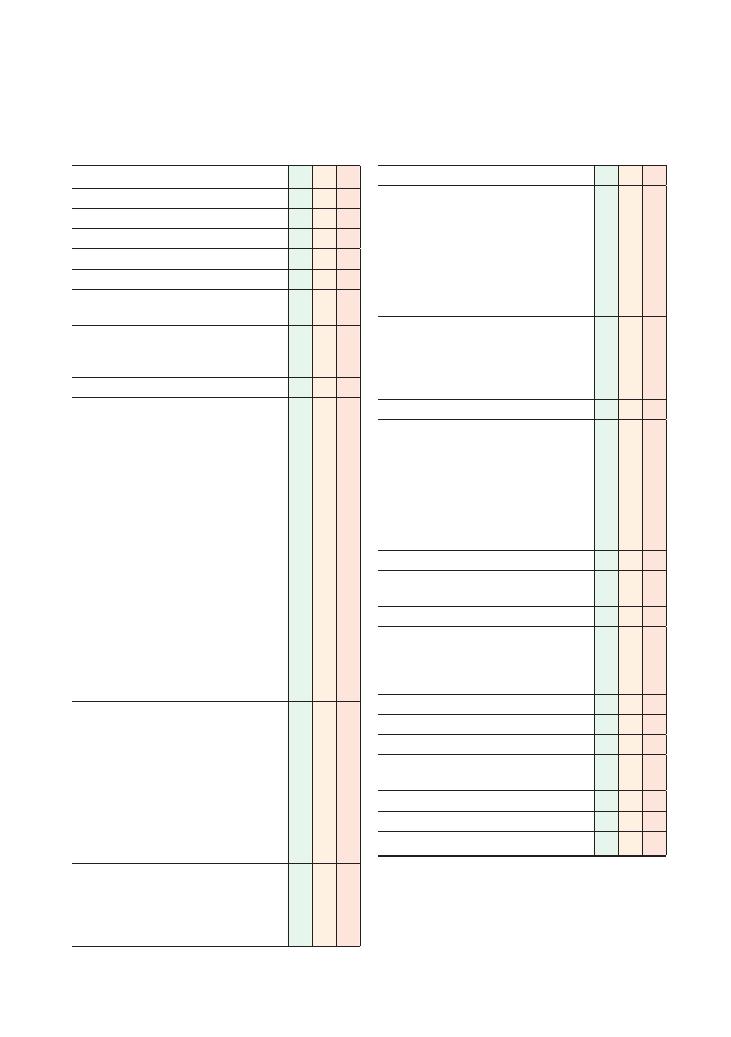

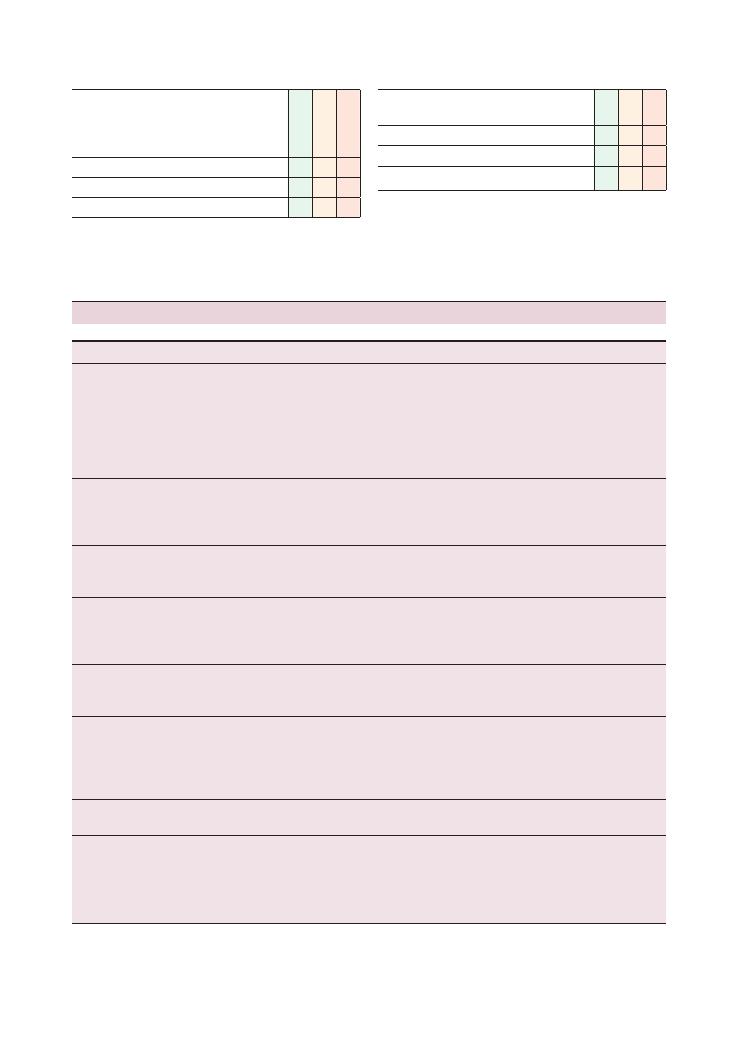

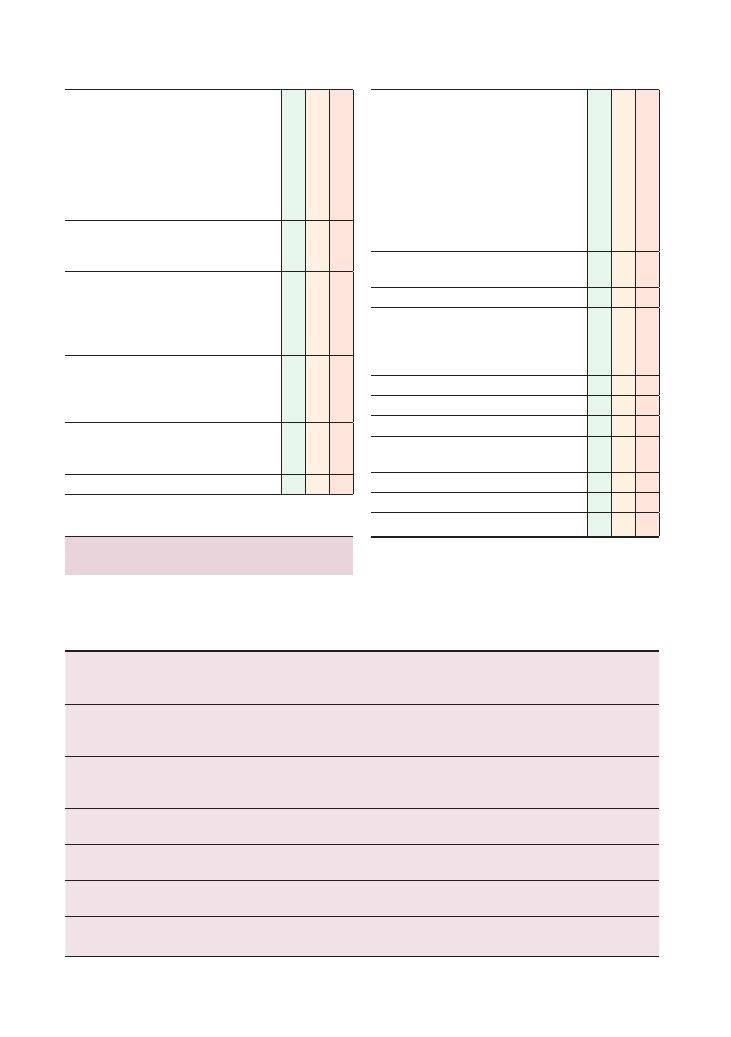

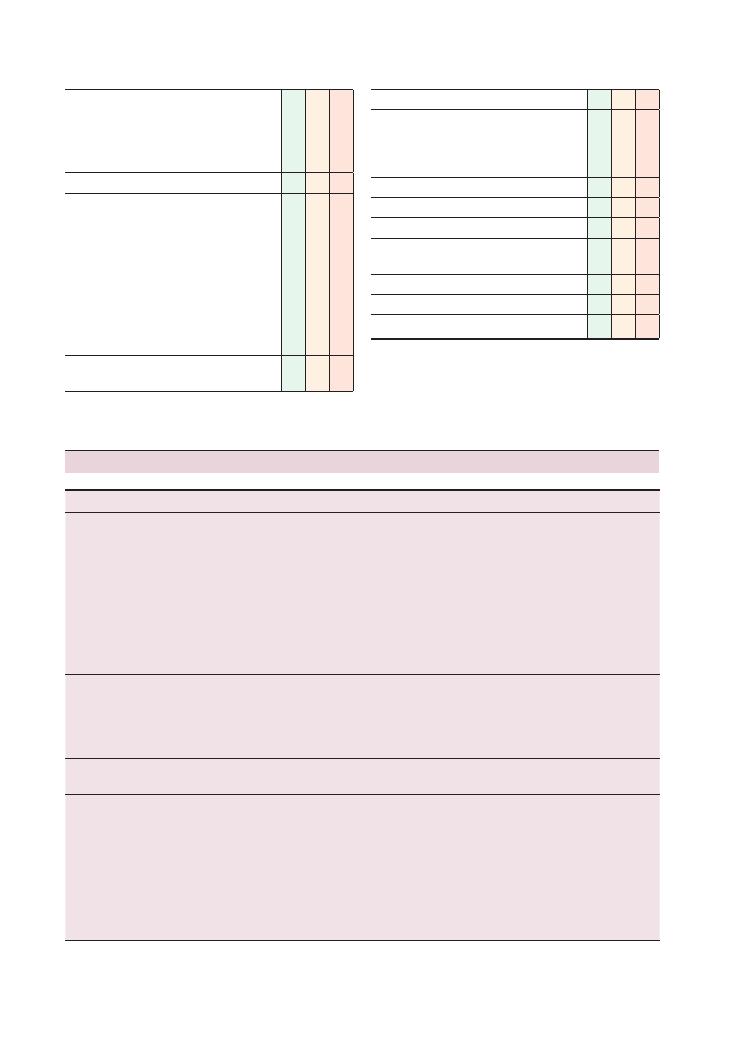

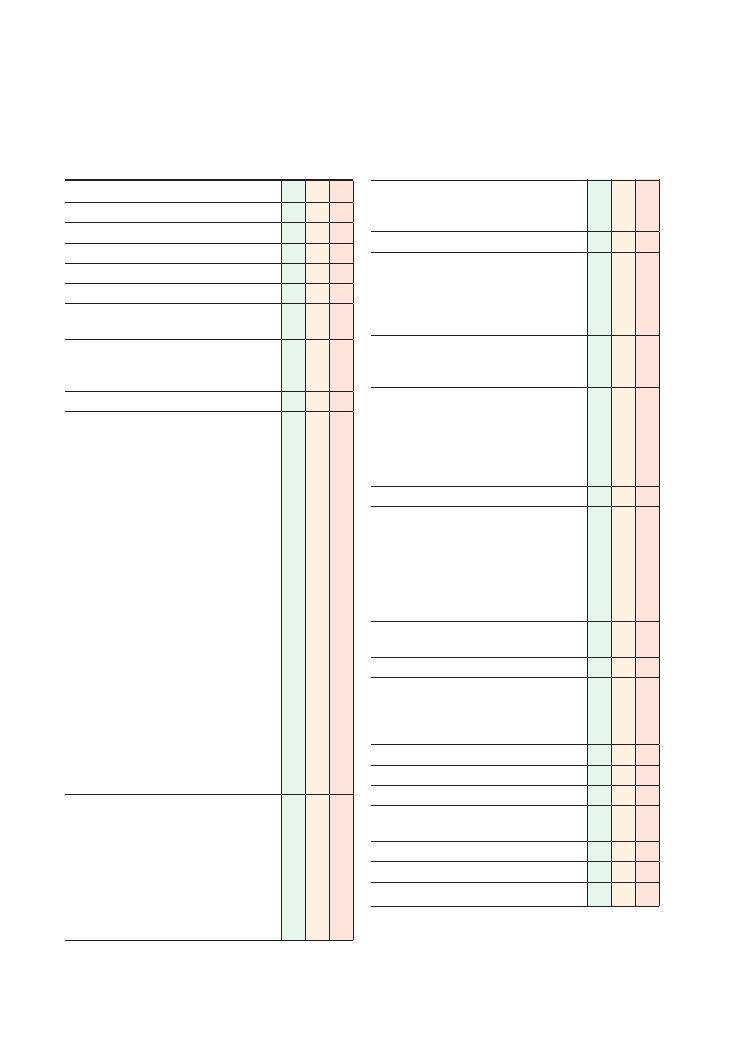

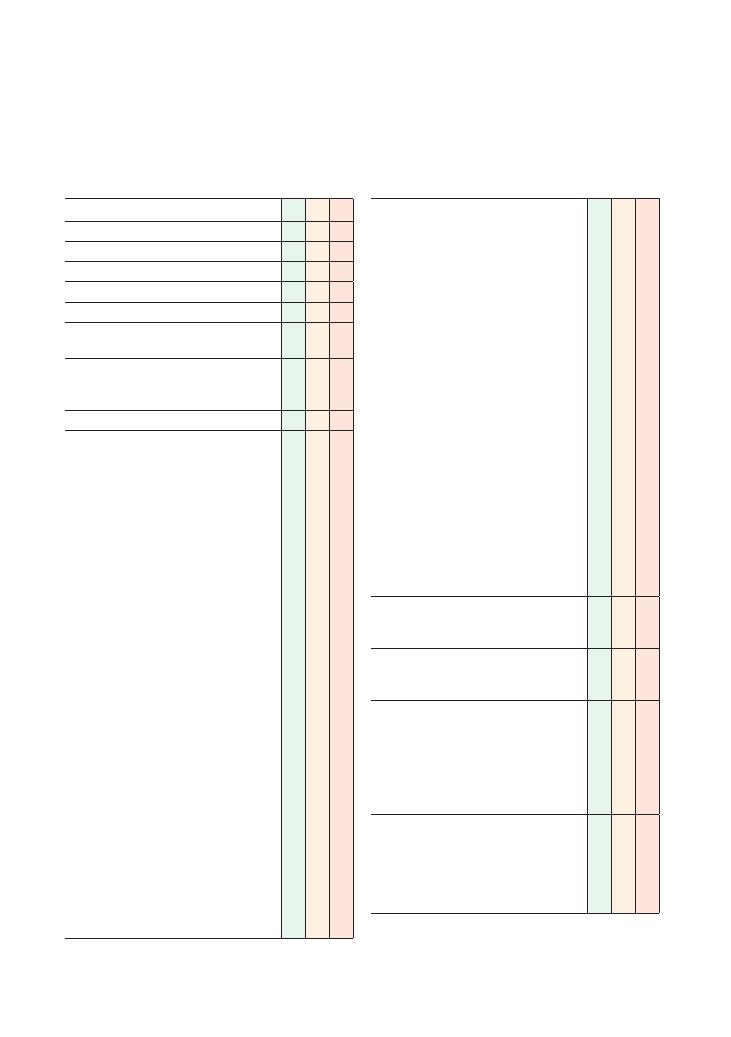

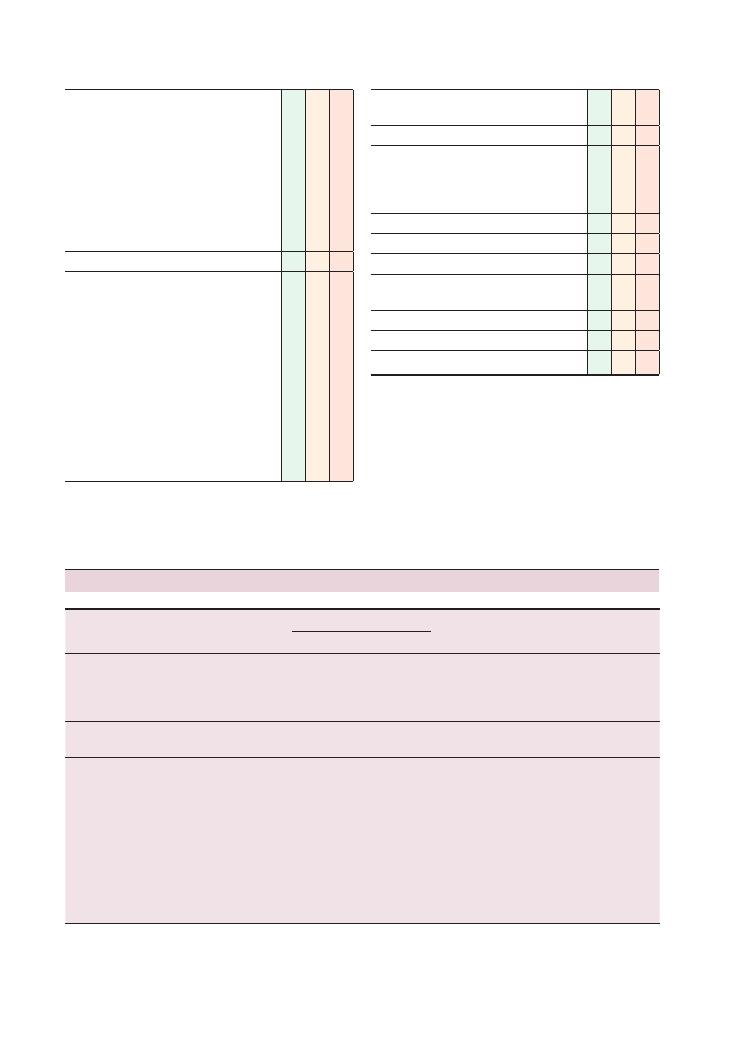

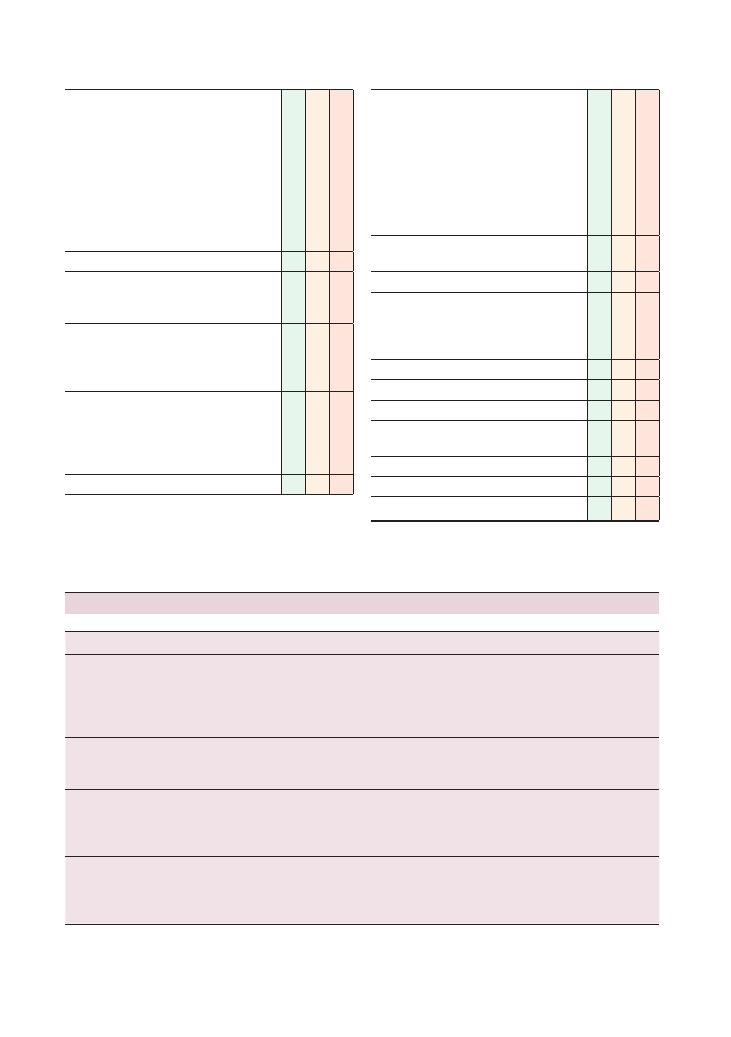

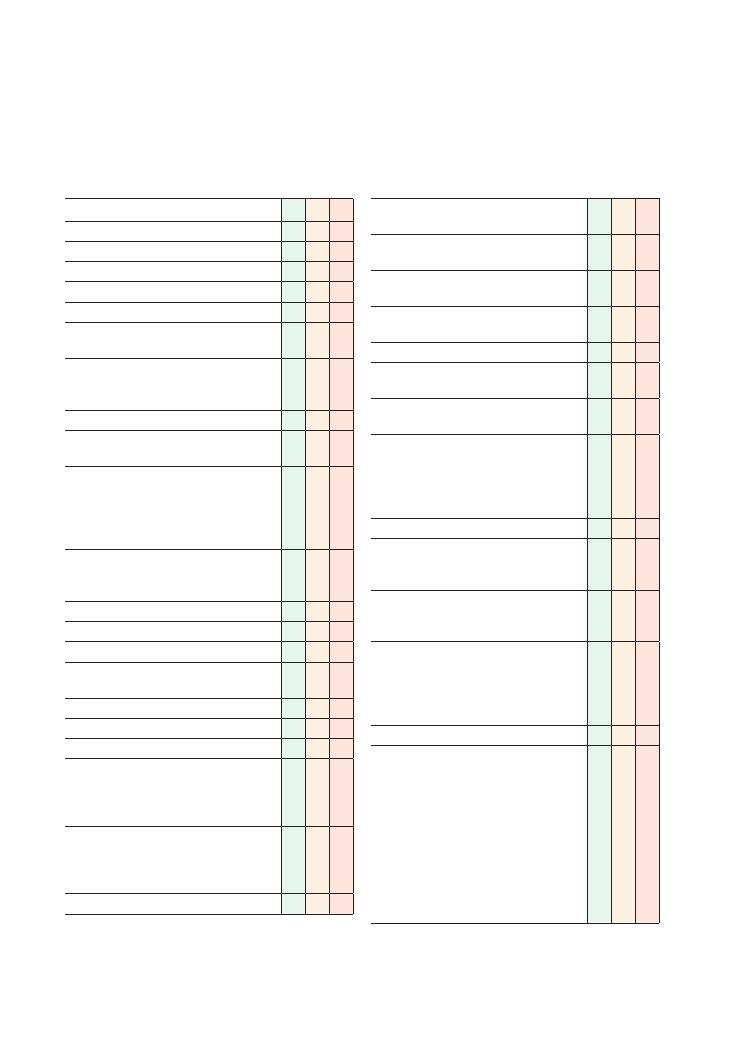

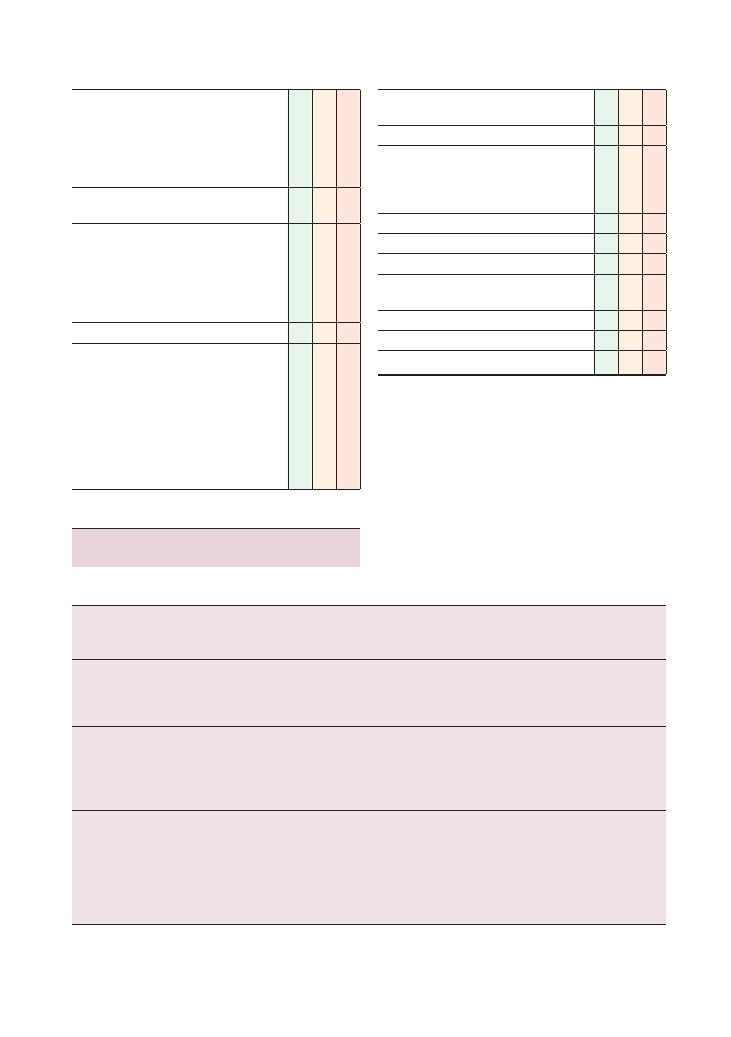

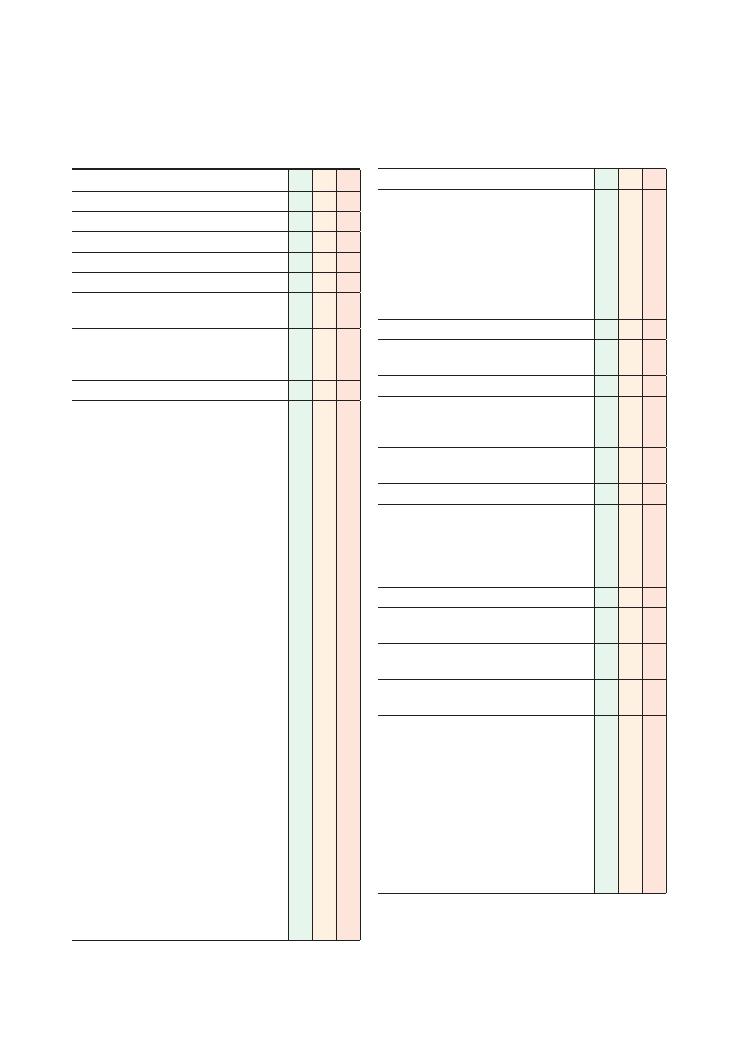

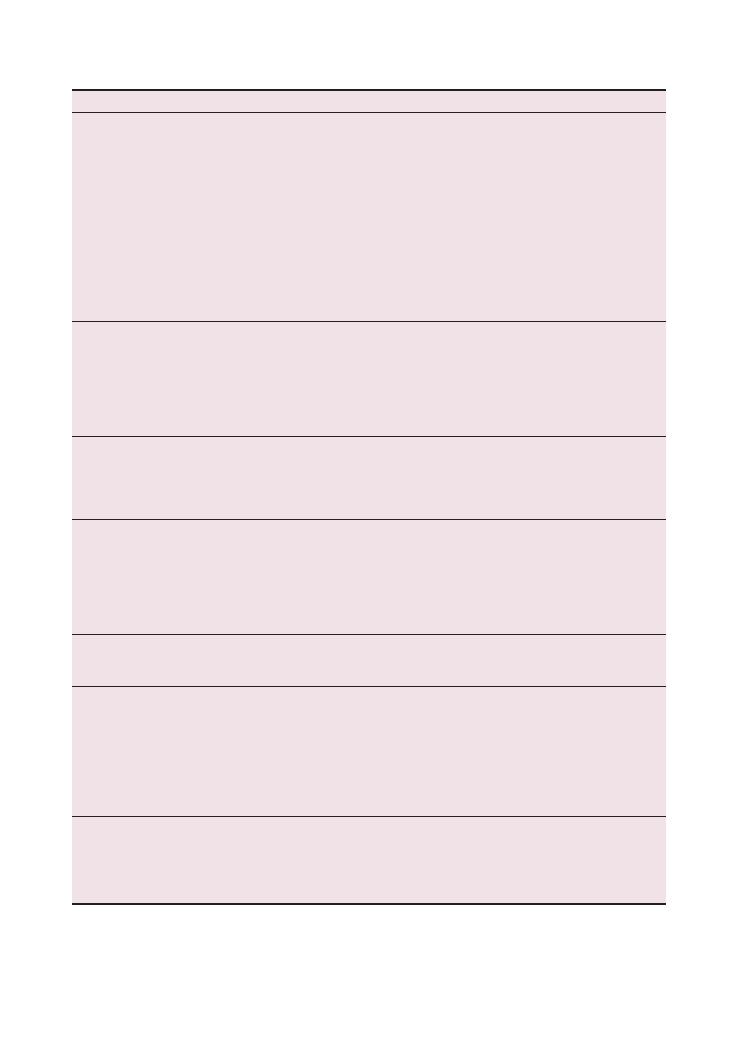

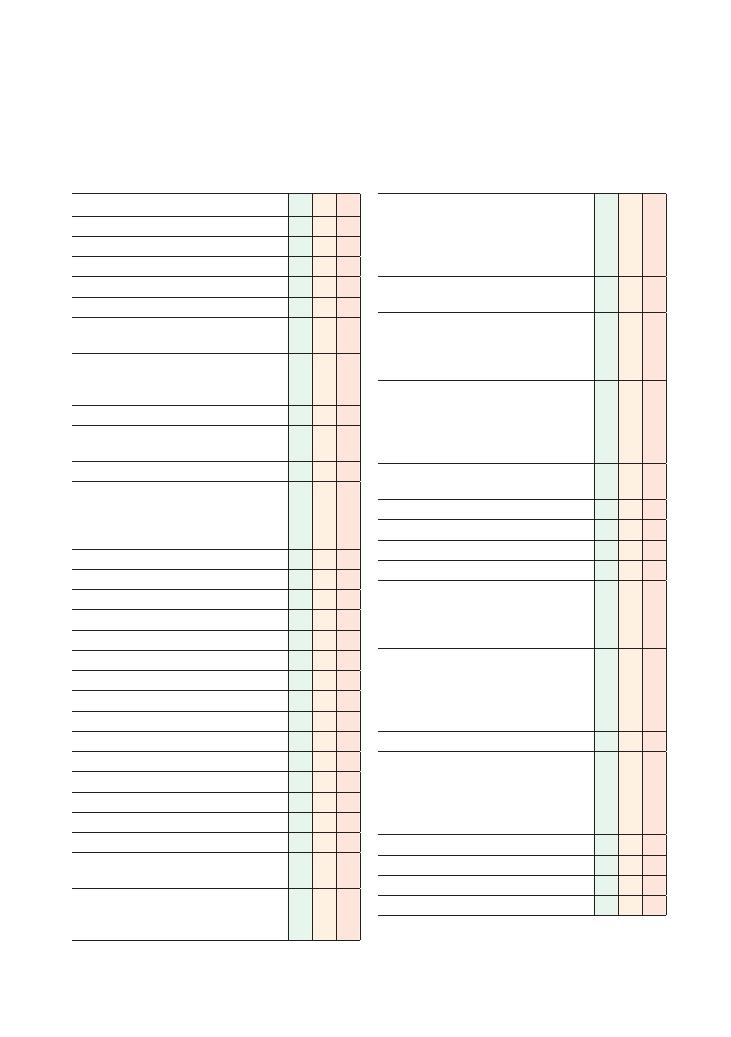

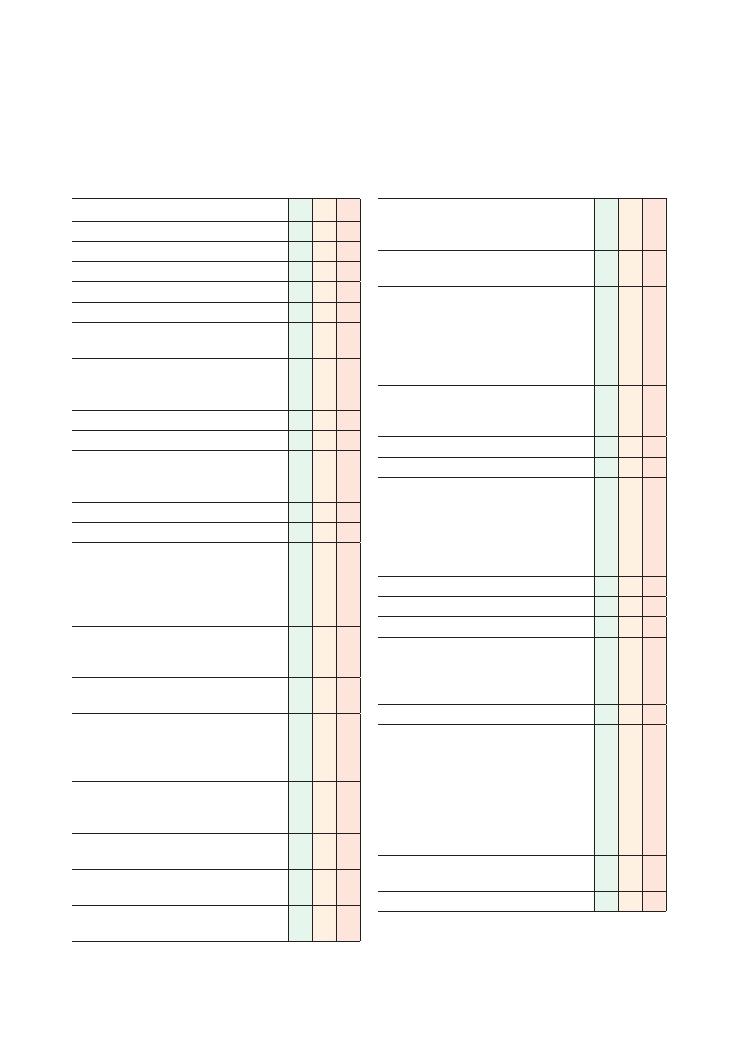

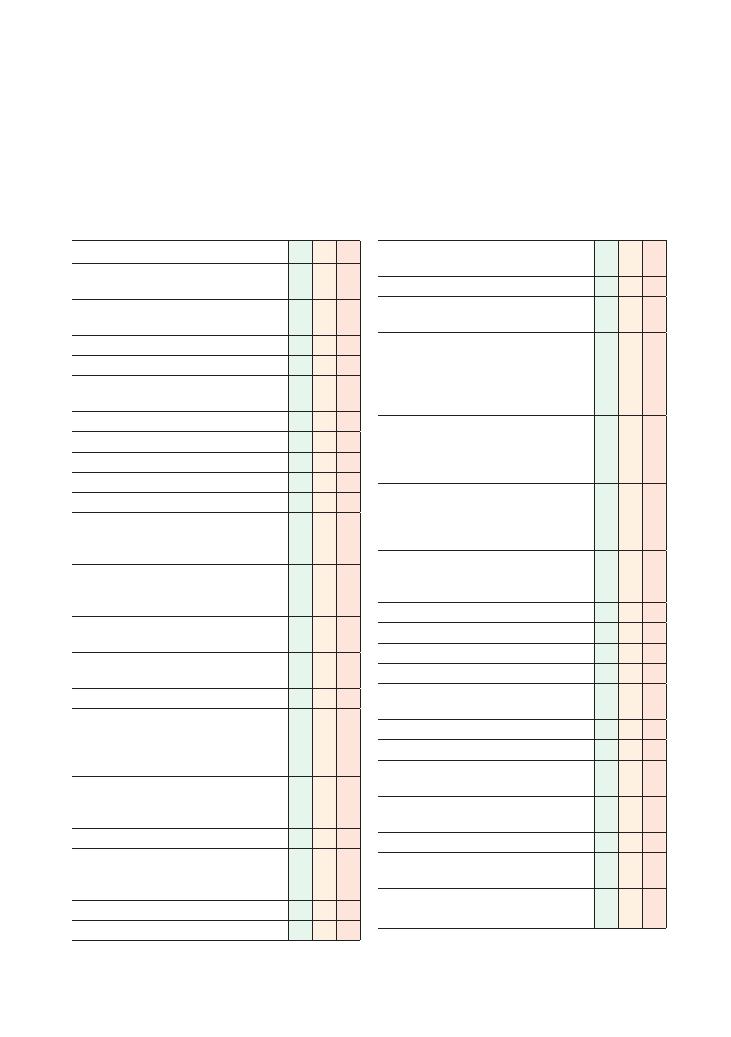

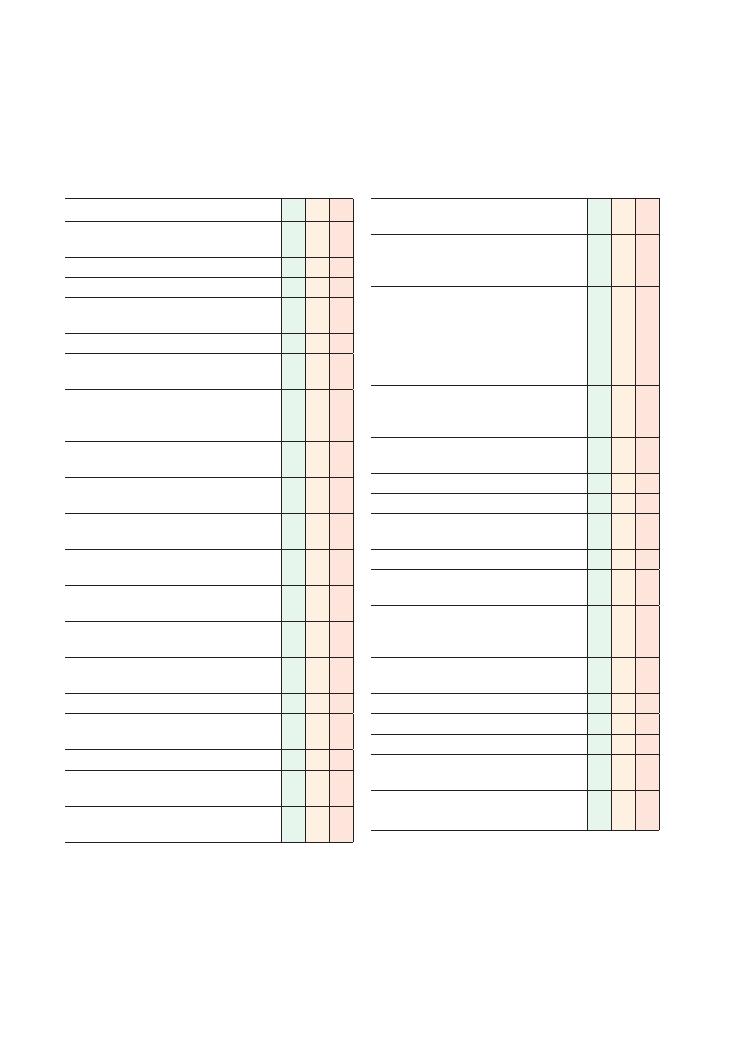

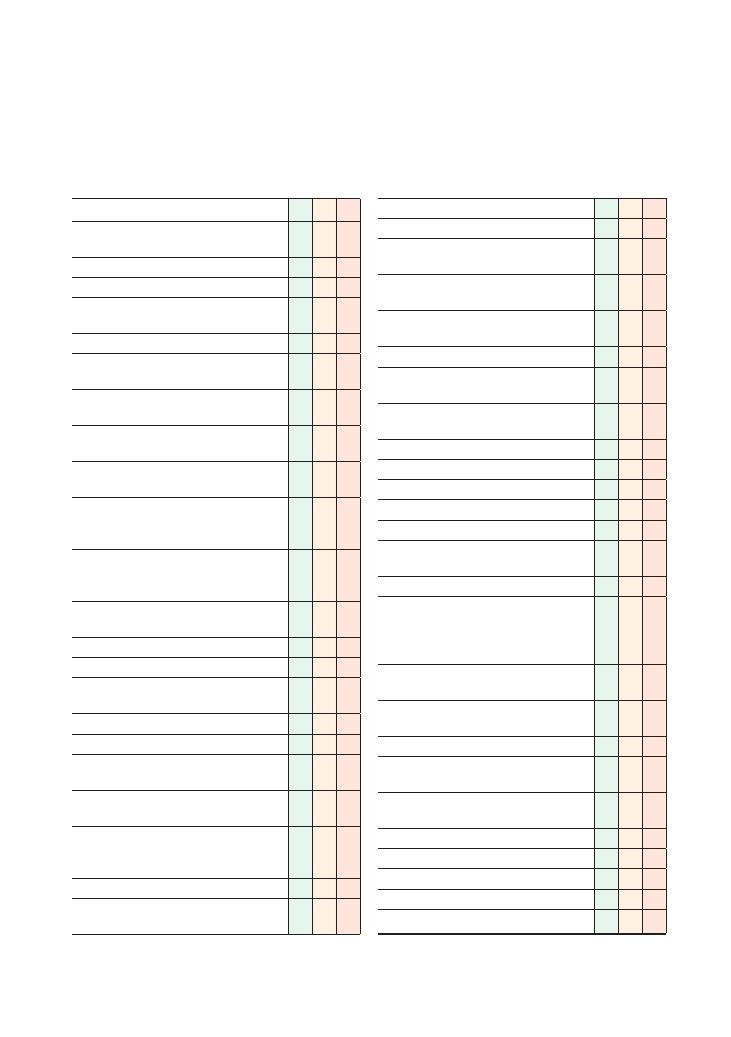

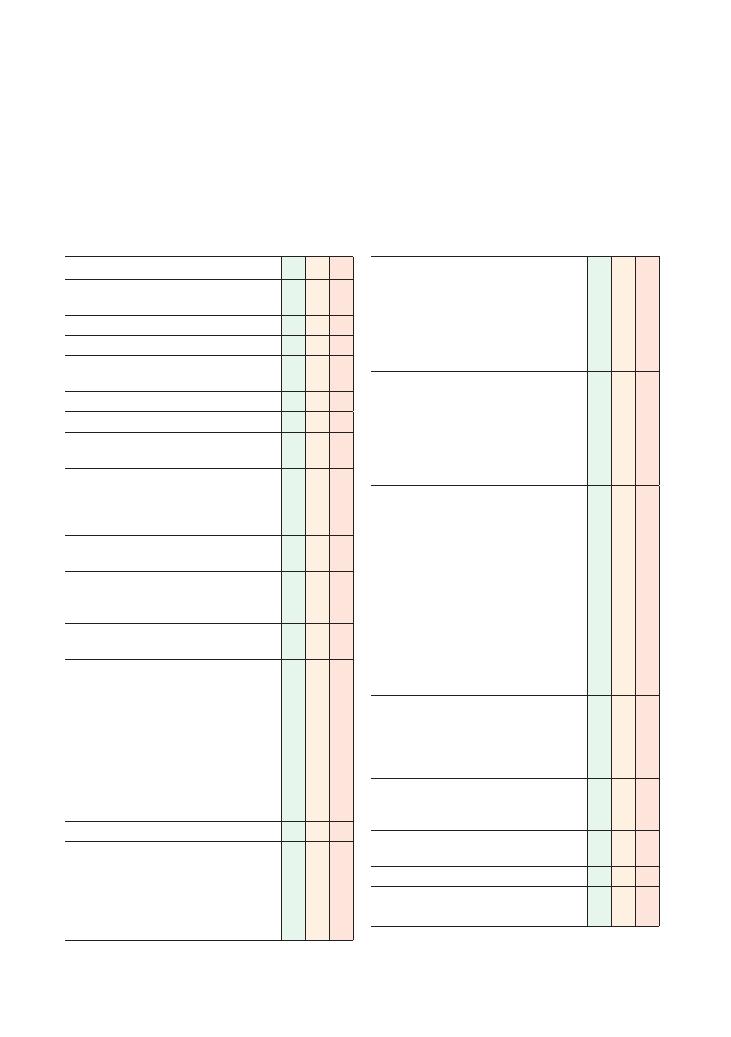

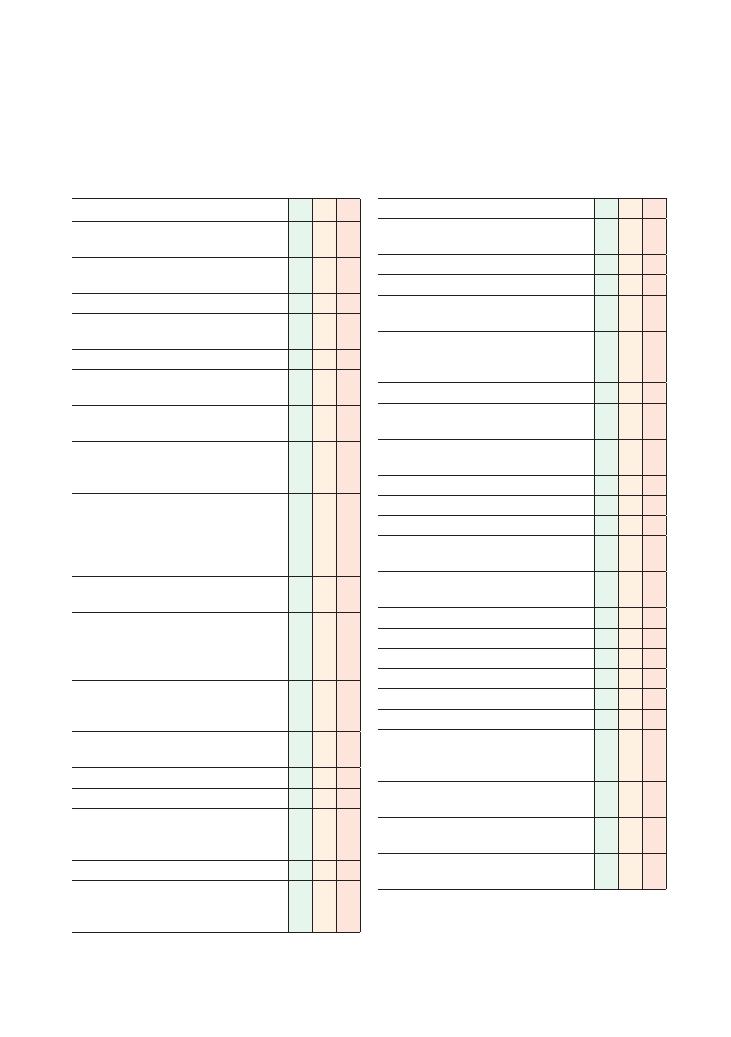

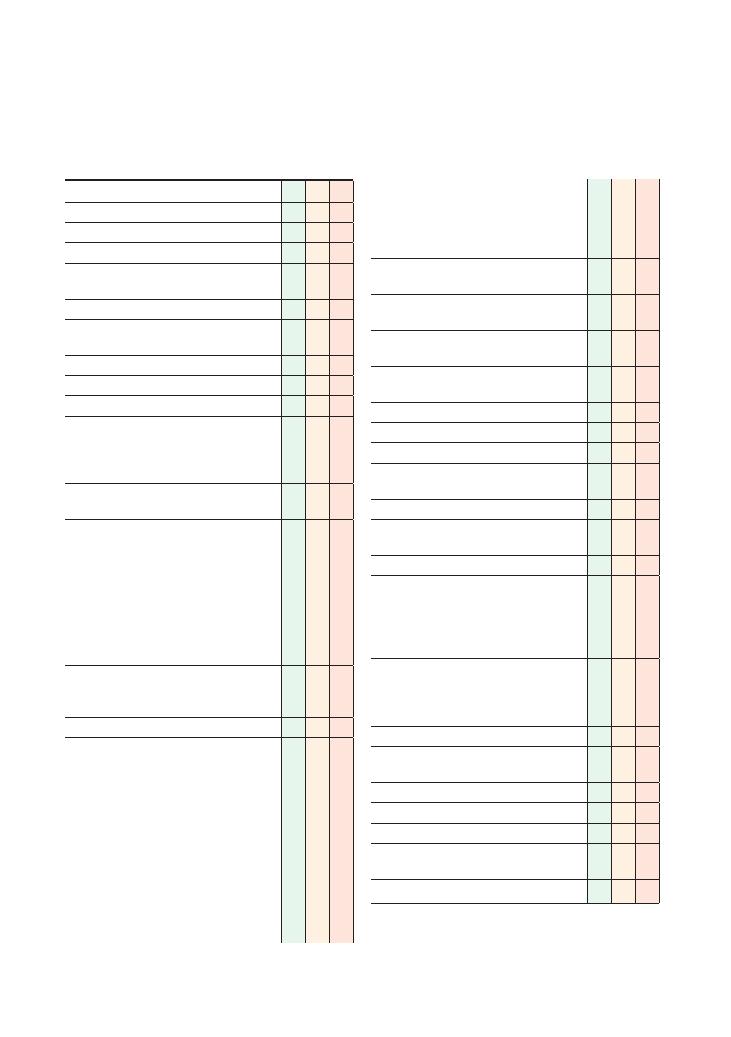

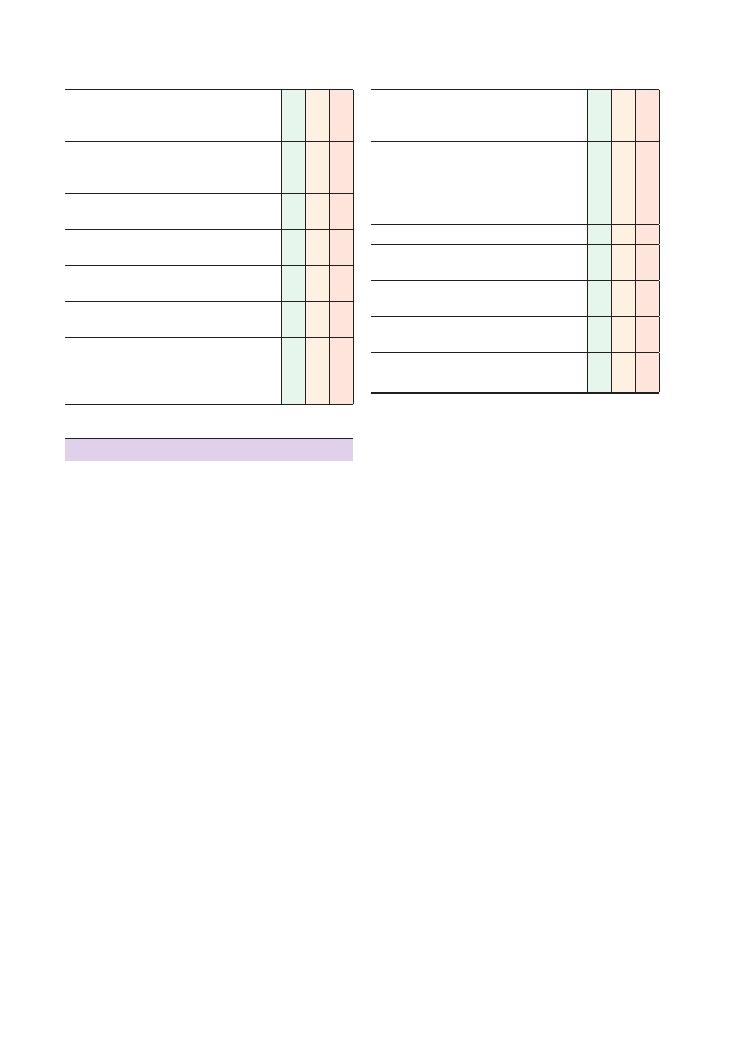

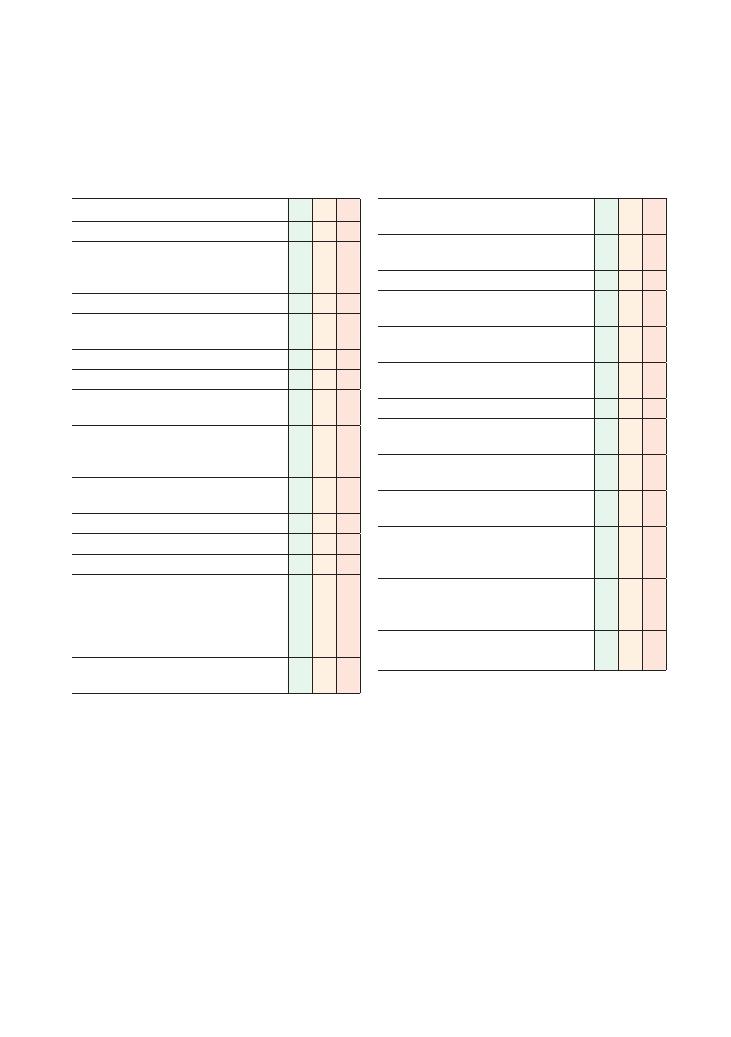

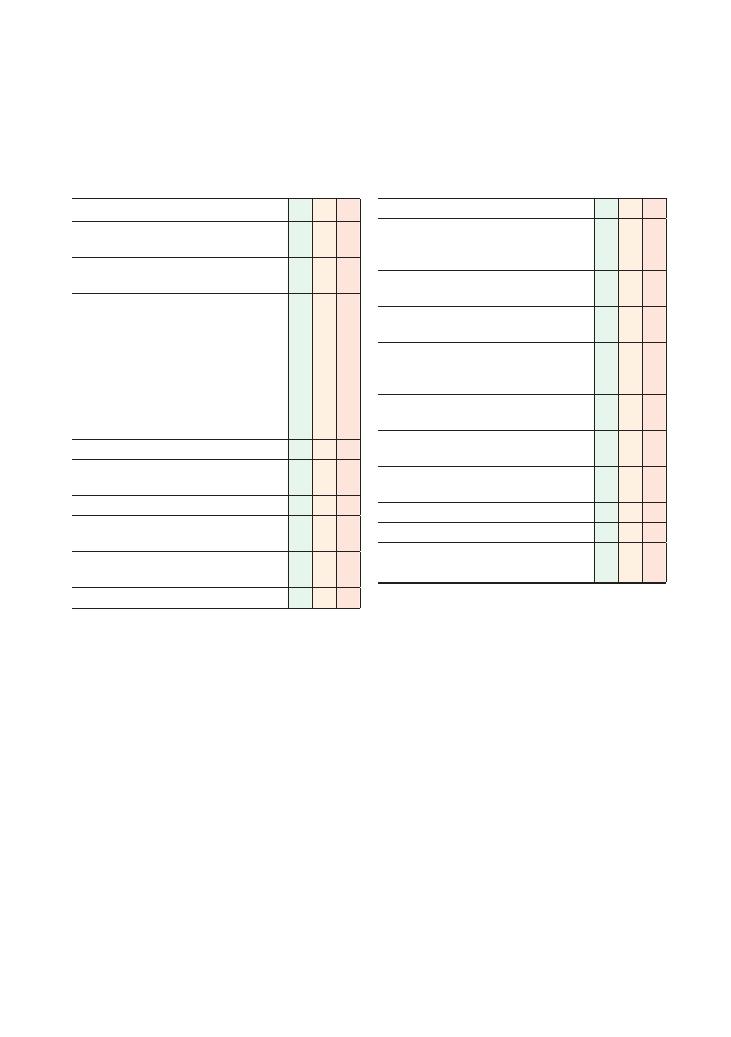

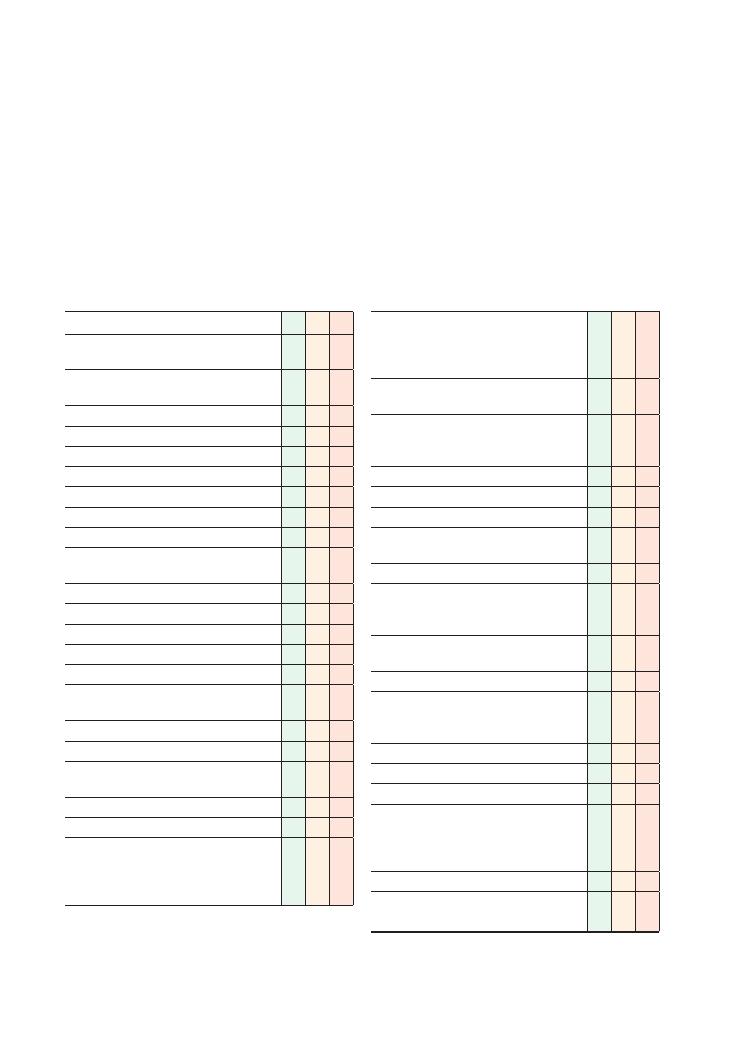

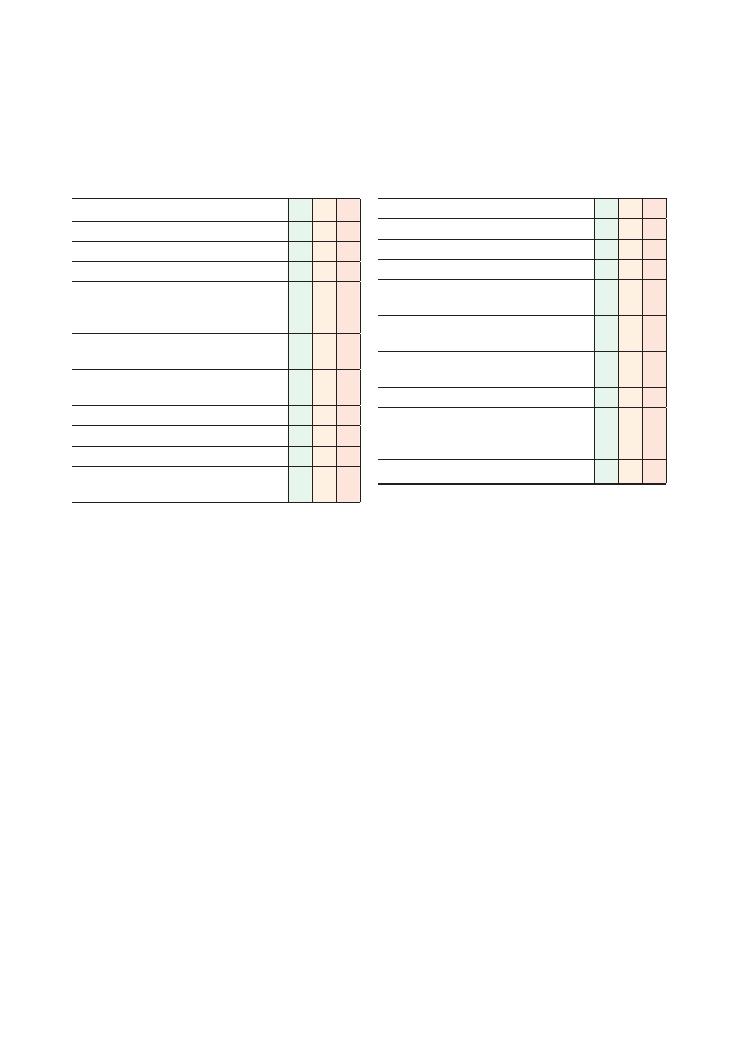

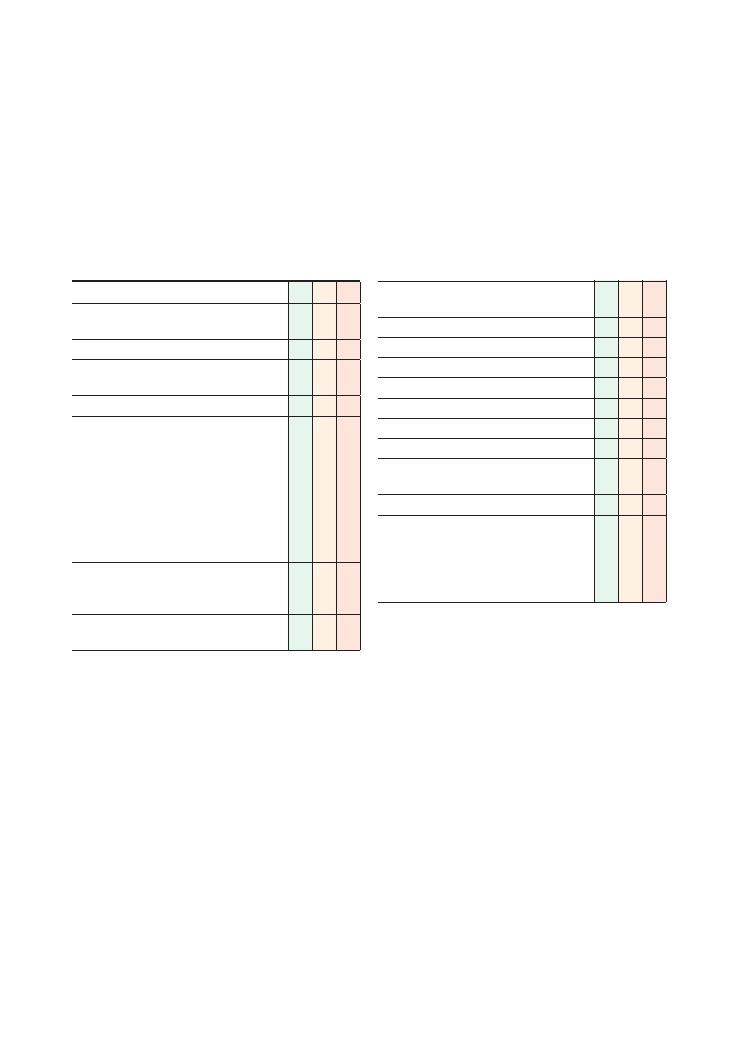

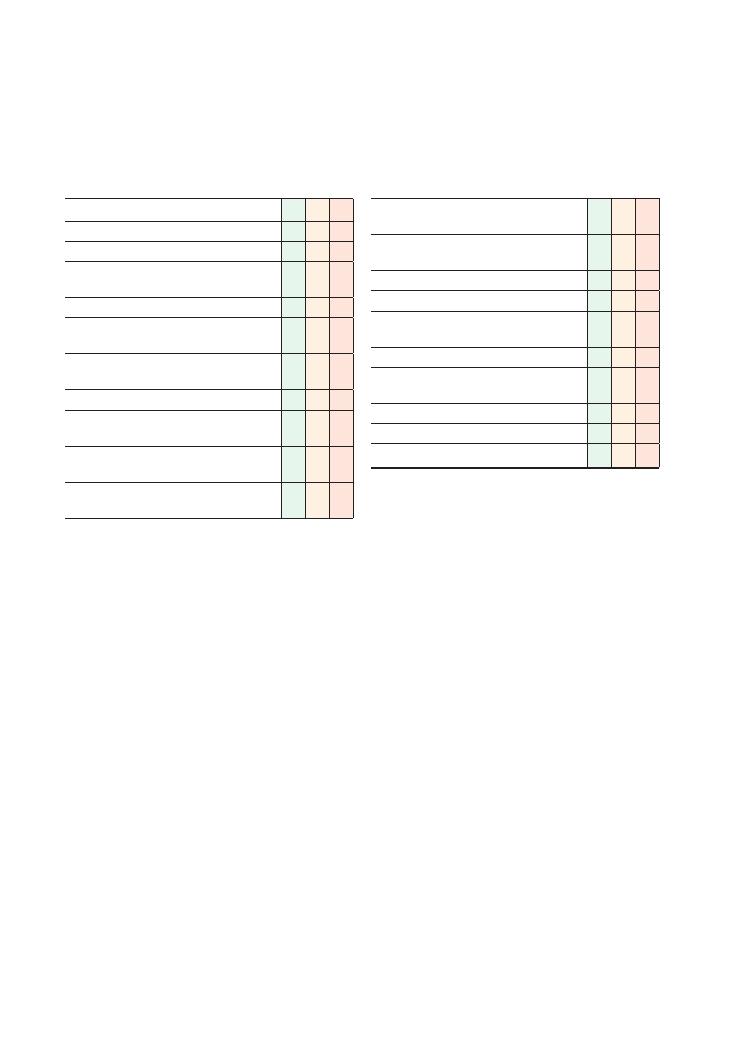

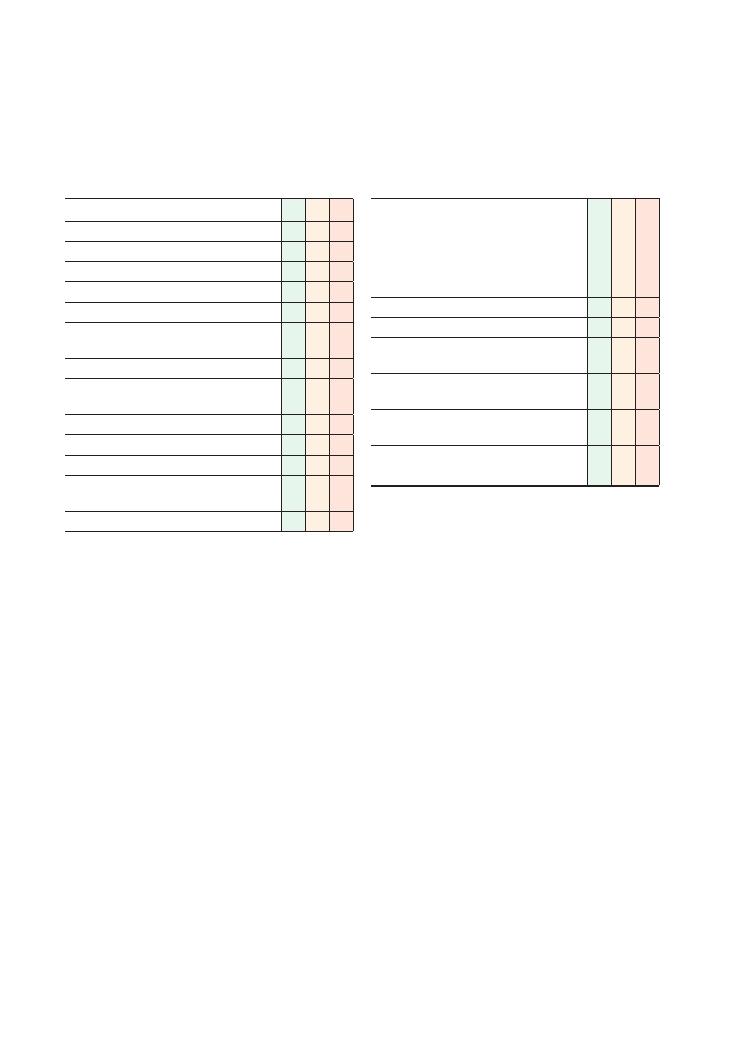

Checklist

P

MP

F

HELP:

H: ‘Hello’ (introduction and gains consent)

E: Exposure

L: Lighting

P: Positions at 45 degrees, asks if patient is in

any pain

Washes hands

Inspection:

• From end of bed: ECG, GTN spray

• Scars: thoracotomy, mitral valvotomy

• Pacemaker

Hands:

• Clubbing (infective endocarditis, cyanotic heart

disease, atrial myxoma)

• Signs of infective endocarditis (splinter

haemorrhages, Janeway lesions, Osler’s nodes)

Radial pulse:

• Rate

• Rhythm (regular or irregular)

• Character (collapsing, slow rising)

• Radial–radial delay

Requests blood pressure

Eyes:

• Xanthelasma

• Corneal arcus

• Anaemia

Face:

• Malar flush

Mouth

• ‘CDD’ (central cyanosis, dental hygiene,

dehydration)

Checklist

P

MP

F

Neck:

• Jugular venous pressure (raised

>4 cm)

• Palpates carotid pulse (character)

Palpates apex beat

Checks if apex beat is displaced in axilla

Palpates sternal edges and subclavicular areas for

thrills

Auscultates chest:

• Mitral area/apex beat (5th intercostal space

[ICS], midclavicular line)

• Tricuspid area (4th ICS, right sternal edge)

• Pulmonary area (2nd ICS, right sternal edge)

• Aortic area (2nd ICS, left sternal edge)

• Palpate carotid or brachial pulse

simultaneously to time murmur

Cardiac manoeuvres:

• Auscultates mitral area with patient lying on

left side and in expiration for murmur of mitral

stenosis

• Auscultates aortic area with patient sitting

forward and in expiration for murmur of aortic

regurgitation

Auscultates lung bases for pulmonary oedema

Palpates shins or ankles for peripheral oedema

Thanks patient

Offers to help patient get dressed

Washes hands

Presents findings

Offers appropriate differential diagnosis

Suggests appropriate further investigations and

management

OVERALL IMPRESSION:

Examinations:

1 Cardiovascular 3

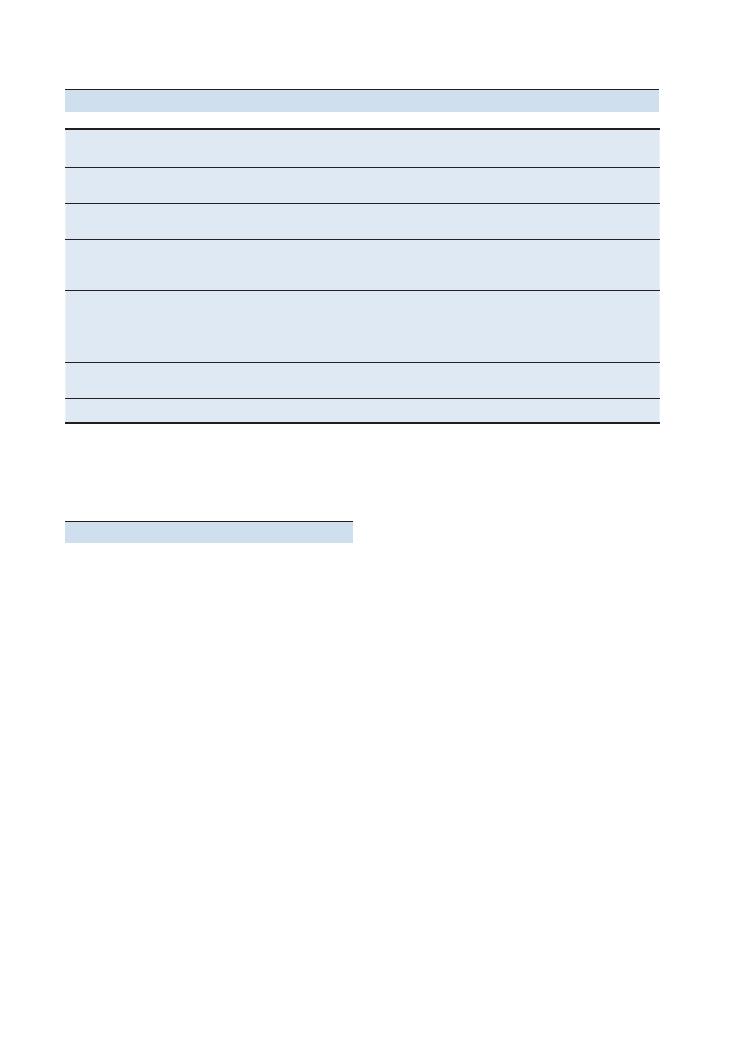

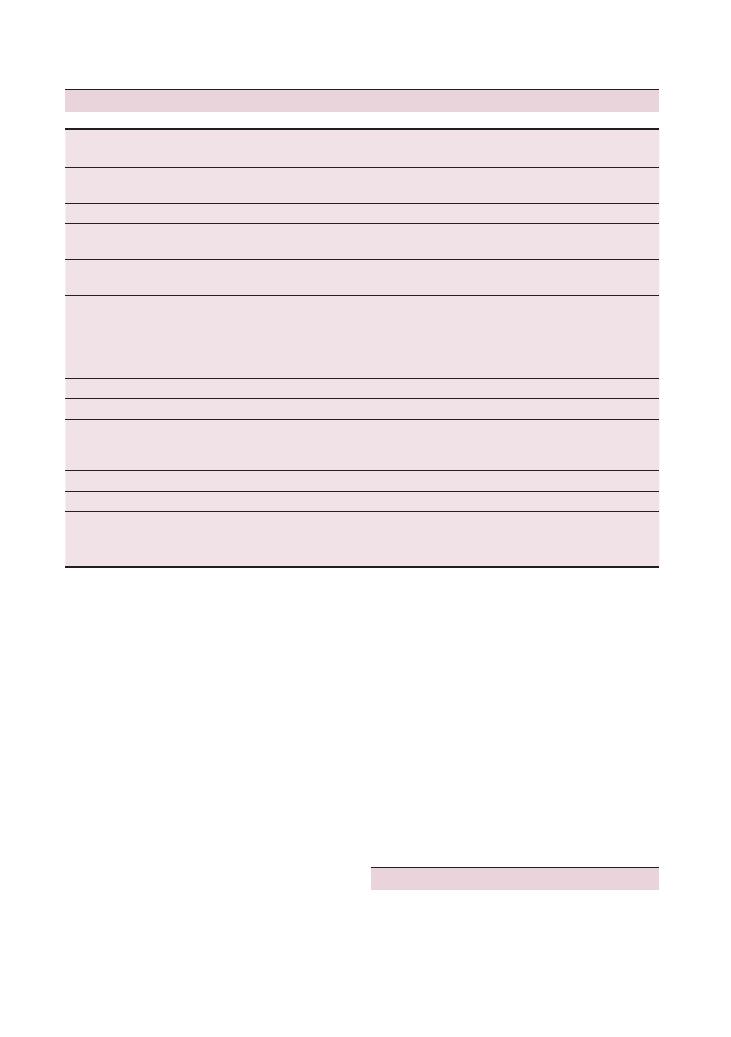

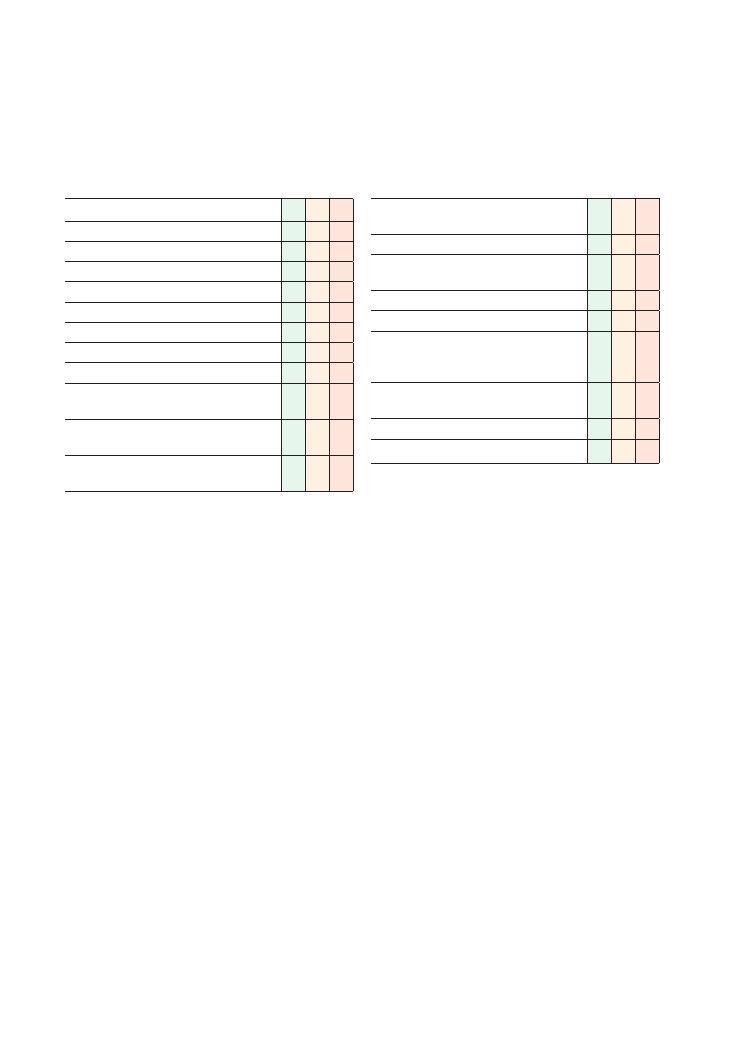

Summary of common conditions seen in OSCEs

Aortic stenosis

Aortic

regurgitation

Mitral stenosis

Mitral

regurgitation

Tricuspid

regurgitation

Location of murmur

(loudest heard)

Aortic area

Aortic area

Mitral area

Mitral area

Tricuspid area

Type of murmur

Ejection systolic

Radiating to carotids

End-diastolic

Mid-diastolic

Pan-systolic

Radiating to axilla

Systolic

Manoeuvres to

enhance murmur

None

Sit forward and

expirate

Roll on left side and

expirate

None

None

Pulse

Slow rising

Collapsing

Carotid pulsations

Irregular if atrial

fibrillation

Normal

Normal

Peripheral features

Narrow pulse pressure

Commonly have CABG

scar

Quincke’s sign

Corrigan’s pulsation

De Musset’s sign

Atrial fibrillation on

auscultation

Right-sided heart

failure

None

JVP increased to

earlobes

Key management

points

Aortic valve

replacement if

severe

Beta-blockers

Diuretics

Treat heart failure

Antibiotic prophylaxis

for gastrointestinal/

genitourinary/dental

procedures

Aortic valve

replacement

Treat any heart failure

Antibiotic prophylaxis

for gastrointestinal/

genitourinary/

dental procedures

Mitral valvotomy

Treat atrial fibrillation

and heart failure

Antibiotic prophylaxis

for gastrointestinal/

genitourinary/

dental procedures

Anticoagulate (with

warfarin)

Mitral valve

replacement

Treat any heart failure

Antibiotic prophylaxis

for gastrointestinal/

genitourinary/

dental procedures

Tricuspid valvotomy

Treat right heart

failure

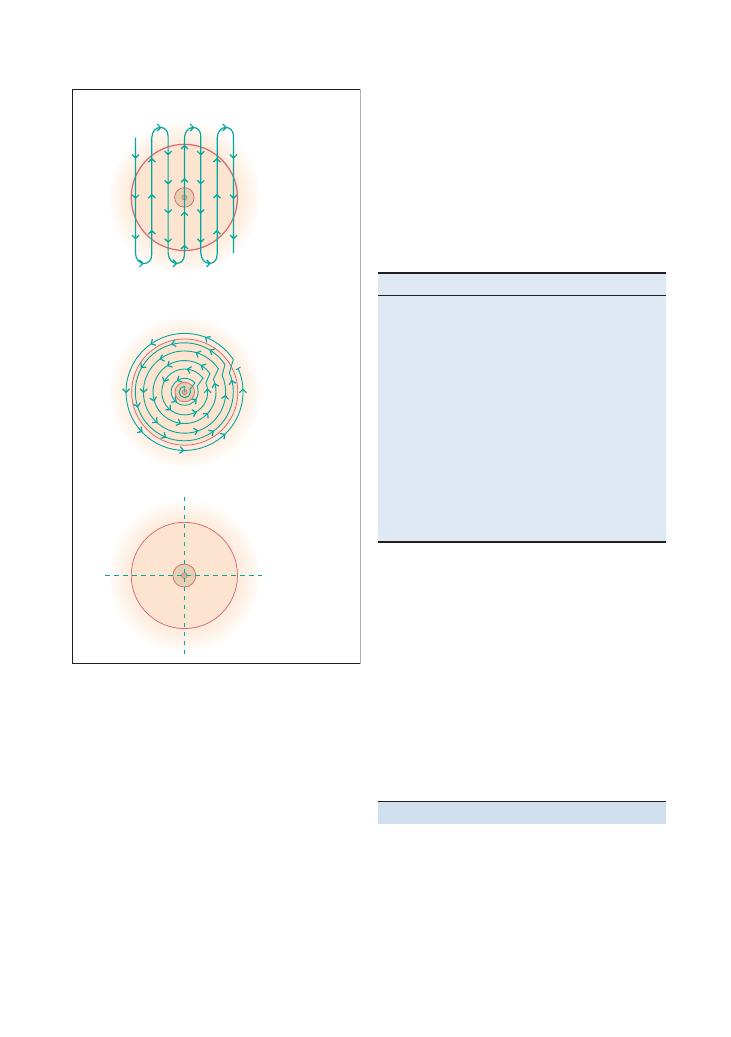

Hints and tips for the exam

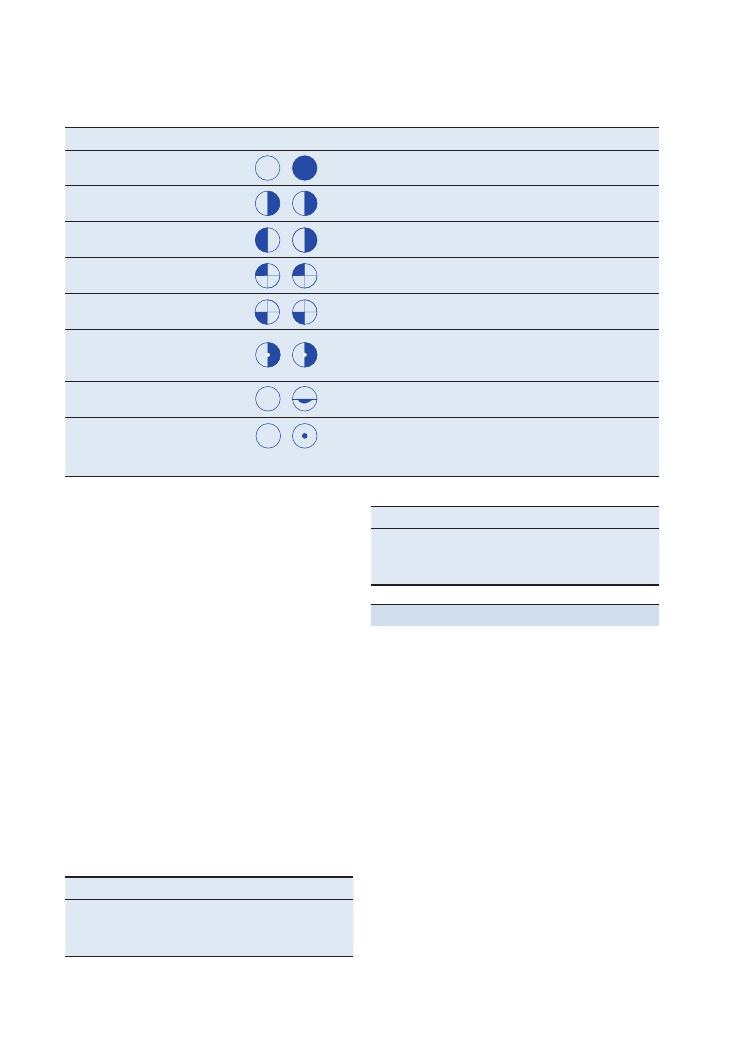

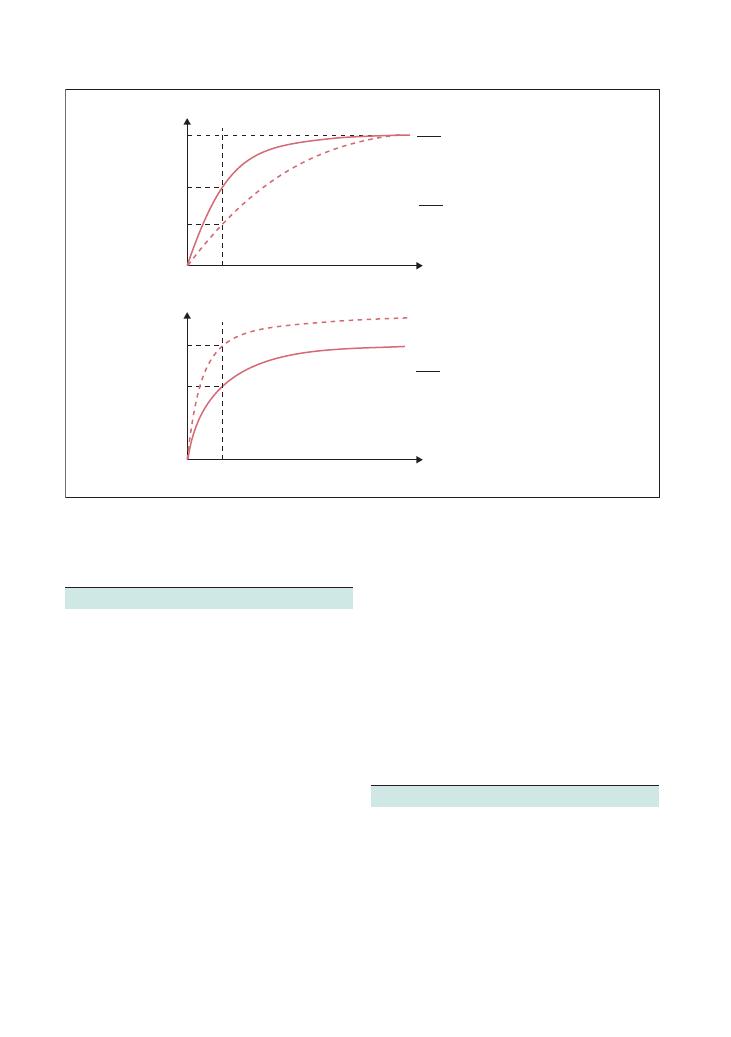

Identifying valvular lesions

Trying to learn all the murmurs and all the conditions

associated with them is futile and only really necessary

if you are a cardiologist. Trying to correctly differentiate

whether murmurs are ejection systolic or pansystolic,

end-diastolic rather than mid-diastolic, is also difficult

and is not necessary for finals and perhaps even PACES.

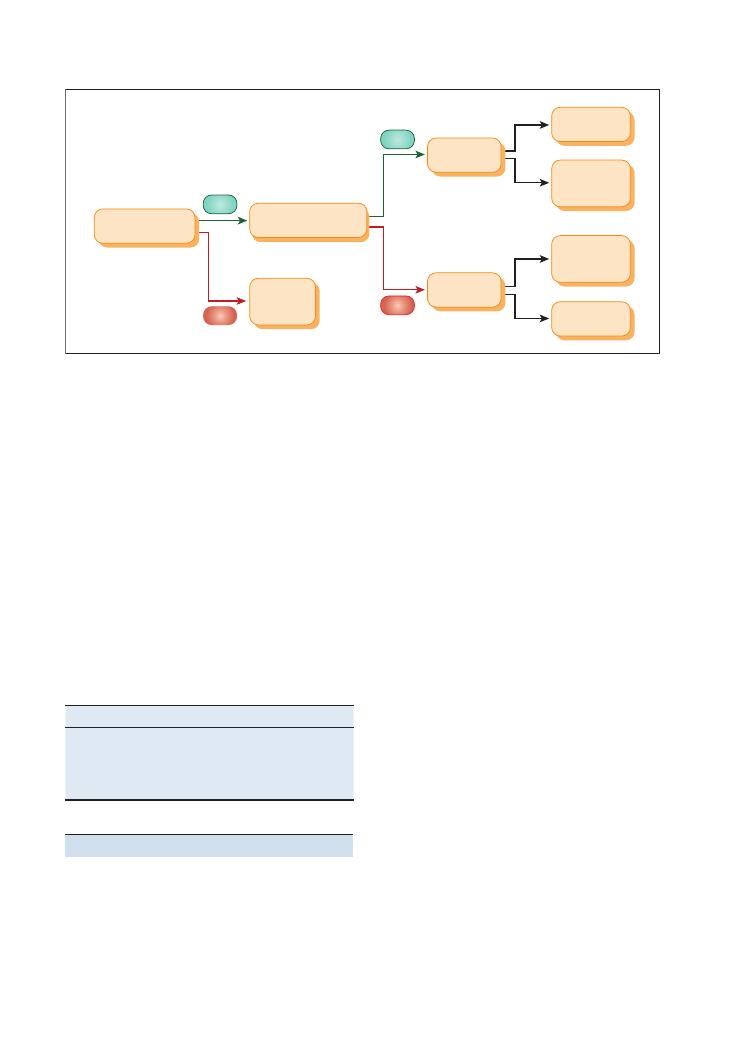

The easiest and most logical way of diagnosing the

correct valvular lesion from the murmur is by answer-

ing the following two questions:

1. Where is the murmur?

Murmurs can frequently be heard throughout the

chest, but the area where a murmur is loudest is usually

where the murmur is – so a murmur heard loudest in

the aortic area will probably be aortic regurgitation

(AR) or aortic stenosis (AS), and a murmur heard

loudest in the mitral area will probably be mitral regur-

gitation (MR) or mitral stenosis (MS). Exceptions to

this include Gallavardin’s phenomenon, in which an AR

murmur is heard loudest in the tricuspid area; however,

from the perspective of passing an exam, you would

not be penalised for missing that, and in any case it is

extremely rare.

2. Is it systolic or diastolic?

In other words, does the murmur correspond with the

pulse (systolic) or not (diastolic)?

Murmurs will only be produced if the natural flow

of the blood is opposed. In the case of valves through

which the blood leaves the heart (such as the aortic

valve), systolic murmurs will only be produced when

the outflow of blood is hindered, which can only

happen in AS (as opposed to AR, which would not

hinder the outflow of blood).

In the case of valves where the blood flows into the

heart in diastole, the natural flow of blood in diastole

is against the aortic valve, as the purpose of the aortic

valve is to stop blood flowing into the aorta during

diastole. Hence blood hits the aortic valves and stops

there when the cardiac muscles relax in diastole. This

natural flow would be impaired by AR as the blood

flows into the aorta when it should not, which is why a

diastolic murmur in the aortic area can only be AR.

4

Examinations:

1 Cardiovascular

Also remember that you should not hear a murmur

with a replaced valve unless it is leaking.

Identifying which valve has been replaced

Remember that the pulse correlates with the first heart

sound, which is the mitral valve closing. (The second

heart sound is the aortic valve closing.)

• If the loudest sound of the valve closing correlates

with the pulse, it is the first heart sound, indicating that

the mitral valve has been replaced.

• If the loudest sound of the valve does not correspond

with the pulse, it is the second heart sound, indicating

that the aortic valve has been replaced.

• The location of the loudest sounds may also be

helpful. Bioprosthetic valves sound the same as normal

heart valves, so it would be unfair for examiners to

expect you to identify them.

Apex beat

The apex beat is palpable in the 5th intercostal

space, and is displaced to the apex in MR. Various char-

acters of the apex beat have been described, such as

‘heaving’ and ‘thrusting’; differentiating between them

is extremely difficult and probably beyond the scope of

a 10-minute OSCE. Other than this, it is more likely to

cause confusion than add anything substantive.

The best course of action is to describe where the

apex beat it, and whether it is palpable or not. An

impalpable apex beat is often caused by obesity,

hyperinflation of the lungs, dextrocardia or poor

technique.

Scars

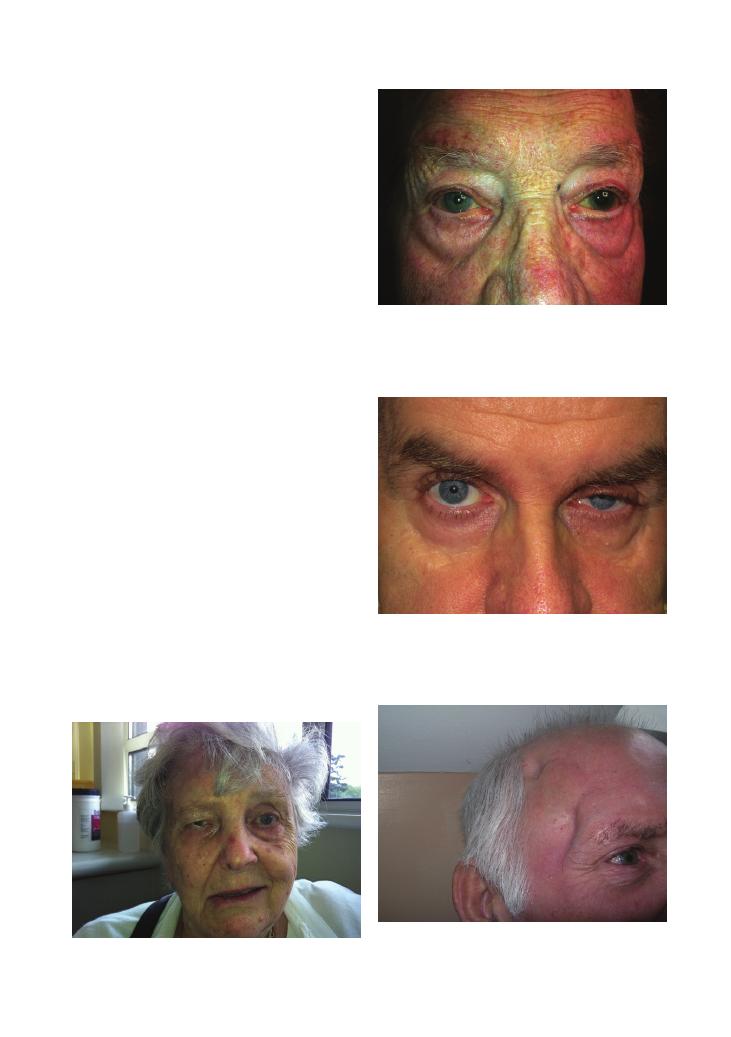

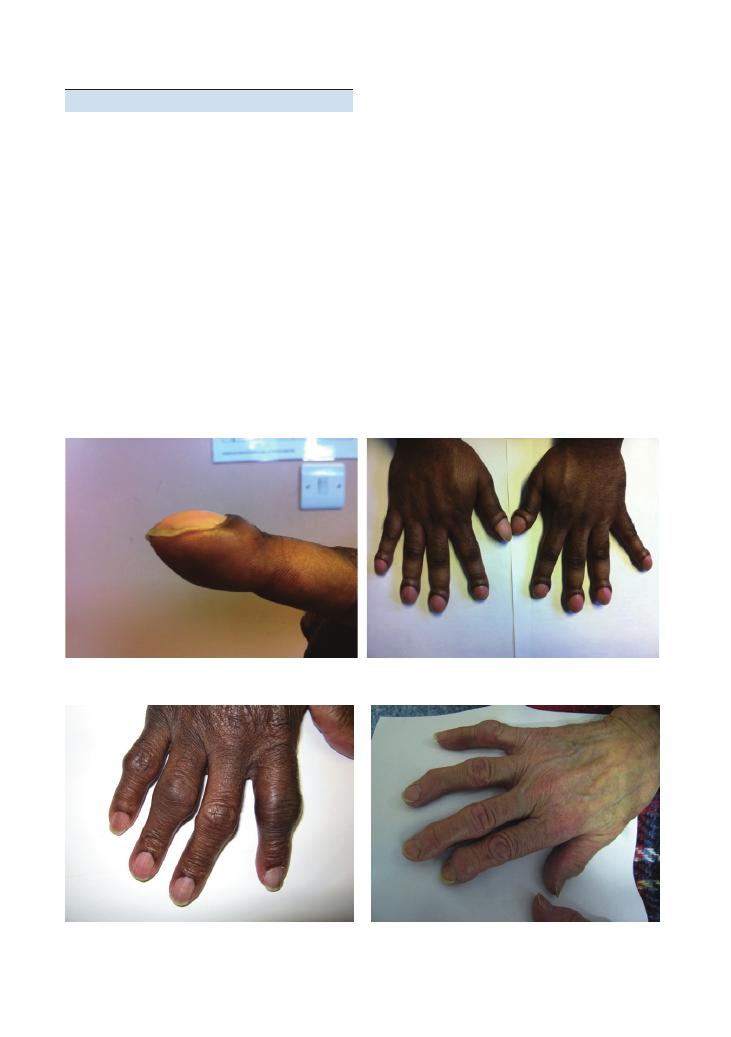

Figures 1.1–1.5 show scars and other signs that you will

need to note on your examination of the patient.

Questions you could be asked

Q. Which organism causing infective endocarditis is

associated with underlying bowel cancer?

A. Streptococcus bovis – a colonoscopy should be con-

sidered in all patients presenting who are found to have

Streptococcus bovis.

Q. What is the most common cause of tricuspid

regurgitation?

A. Most cases of tricuspid regurgitation are ‘func-

tional’, due to dilatation of the right ventricle (so that

the tricuspid valves flop downwards). This could arise

for a number of reasons, such as right heart failure,

congestive heart failure and pulmonary hypertension.

If this seems too complex, remember that diastolic

murmurs are usually ‘ARMS’ (AR or MS), and the area

where it is loudest is probably where the murmur is.

Right versus left

• LEFT-sided murmurs are louder in EXPIRATION.

• RIGHT-sided murmurs are louder in INSPIRATION.

This is because more blood flows into the intrathoracic

cavity and lungs on inspiration, and hence more blood

flows through the right-sided heart valves as these

supply the lungs. The converse is true for left-sided

murmurs.

It is vital to ask patients to hold their breath when

using this test, but you must not ask them to do this for

too long as this can cause the patient pain and you will

fail the exam. Its often a good idea to hold your own

breath at the same time so that you will know when it

is getting too long to allow your patient to breath

normally.

Timing the murmur

Timing murmurs is something that both students and

experienced doctors have difficulty with. Just remem-

ber to palpate the pulse when listening to the heart

sound, and see if you hear the murmur at the same time

as you feel the pulse.

• If the murmur is WITH the pulse, it is a SYSTOLIC

murmur.

• If the murmur if NOT WITH the pulse, it is a

DIASTOLIC murmur.

Use a central pulse such as the carotid or brachial to do

this, otherwise it will not be accurate.

Diastolic murmurs

A number of conditions can cause diastolic murmurs,

but the most common ones are AR and MS – this can

be easily memorised using the mnemonic ‘ARMS’.

Diastolic murmurs are very difficult to elicit for even

the most experienced doctors, and if you can hear a

murmur easily, it is most likely to be systolic. However,

if you do manage to identify a diastolic murmur, it is

handy to remember that MS murmurs are much quieter

than AR murmurs, and if you can auscultate a diastolic

murmur throughout the chest, it is much more likely

to be AR than MS.

Valve replacements

If you see a midline sternotomy scar, you should imme-

diately bring your ear close to the patient’s chest and

listen carefully for the clicking noise that is indicative

of the closing of a metallic valve replacement – this can

easily be heard without a stethoscope.

Examinations:

1 Cardiovascular 5

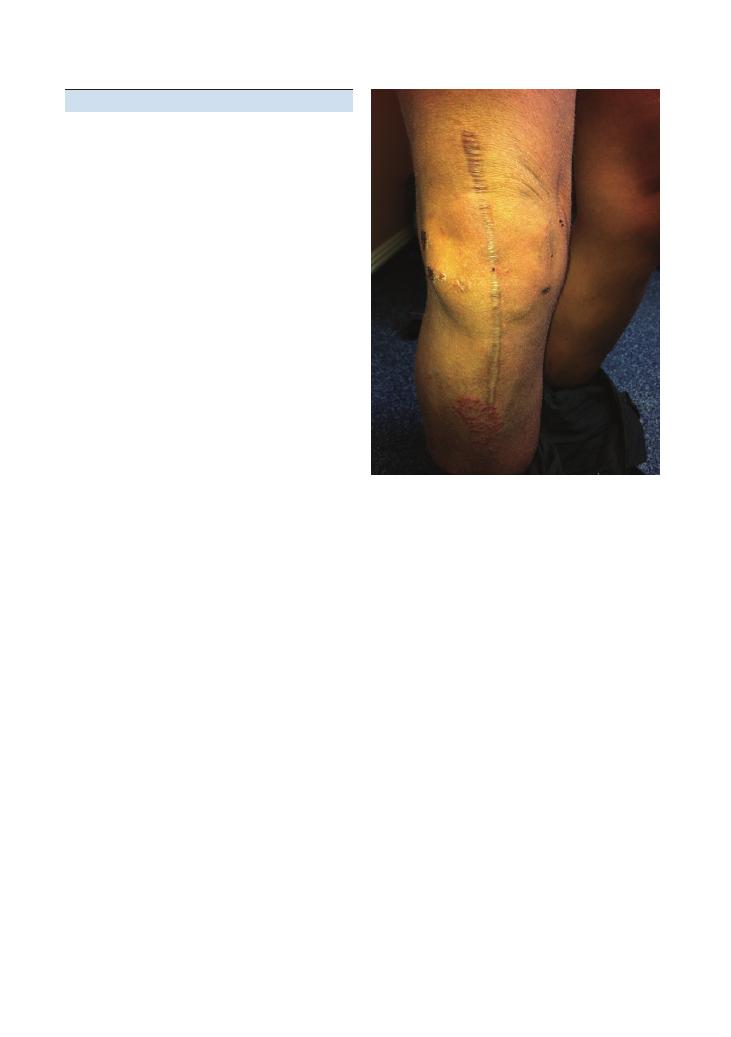

Figure 1.1 Graft scar from leg vein removal in coronary artery

bypass grafting

Figure 1.2 Chest scar in coronary artery bypass grafting

Figure 1.3 Xanthelasma

Figure 1.4 Corneal arcus

Figure 1.5 Indication of pacemaker insertion

6

Examinations:

1 Cardiovascular

Q. How should a patient with suspected heart failure

be investigated in primary care?

A. According to the NICE guidelines (NICE, 2010), the

primary investigation of choice is the blood level of

brain natriuretic peptide (BNP)– patients with normal

results are unlikely to have heart failure, and those with

a BNP level

>400 pg/mL should be investigated urgently

(within 2 weeks).

Reference

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

(2010) Chronic heart failure: Management of chronic

heart failure in adults in primary and secondary care.

Available from http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/

live/13099/50526/50526.pdf (accessed June 2012).

7

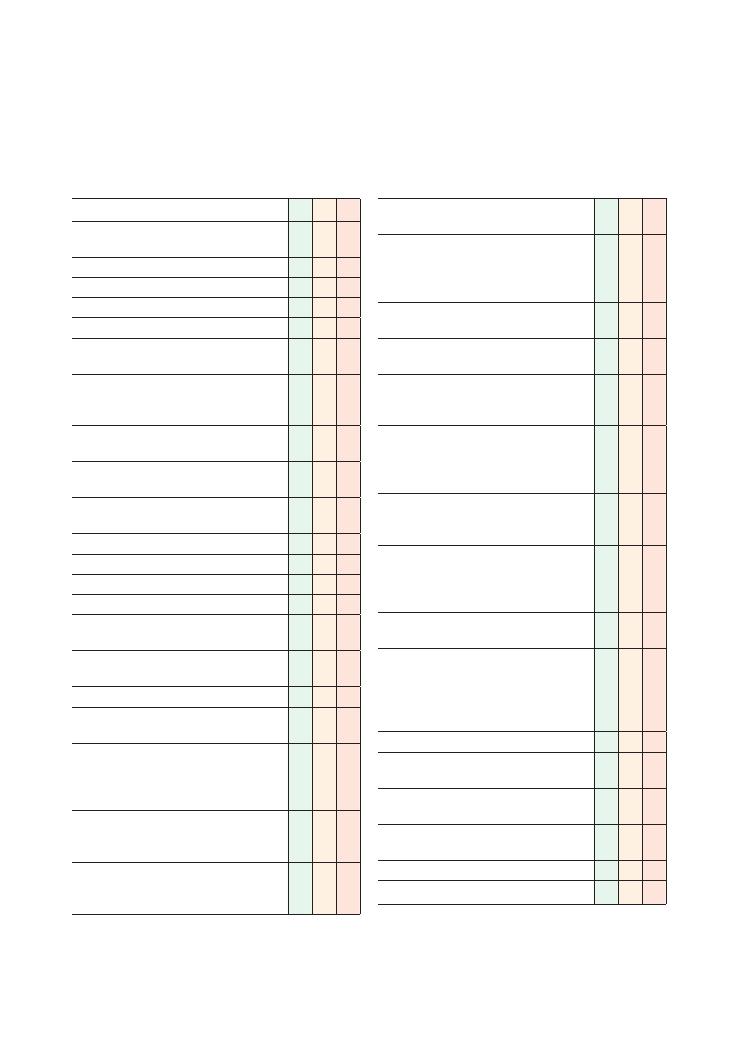

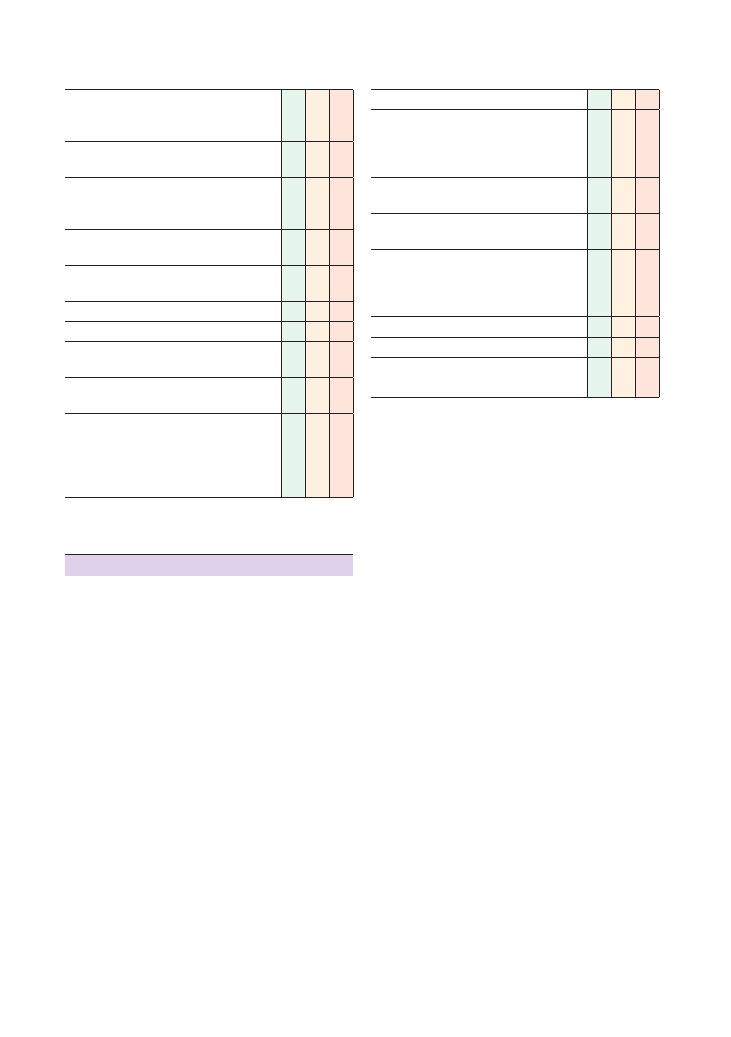

2 Respiratory

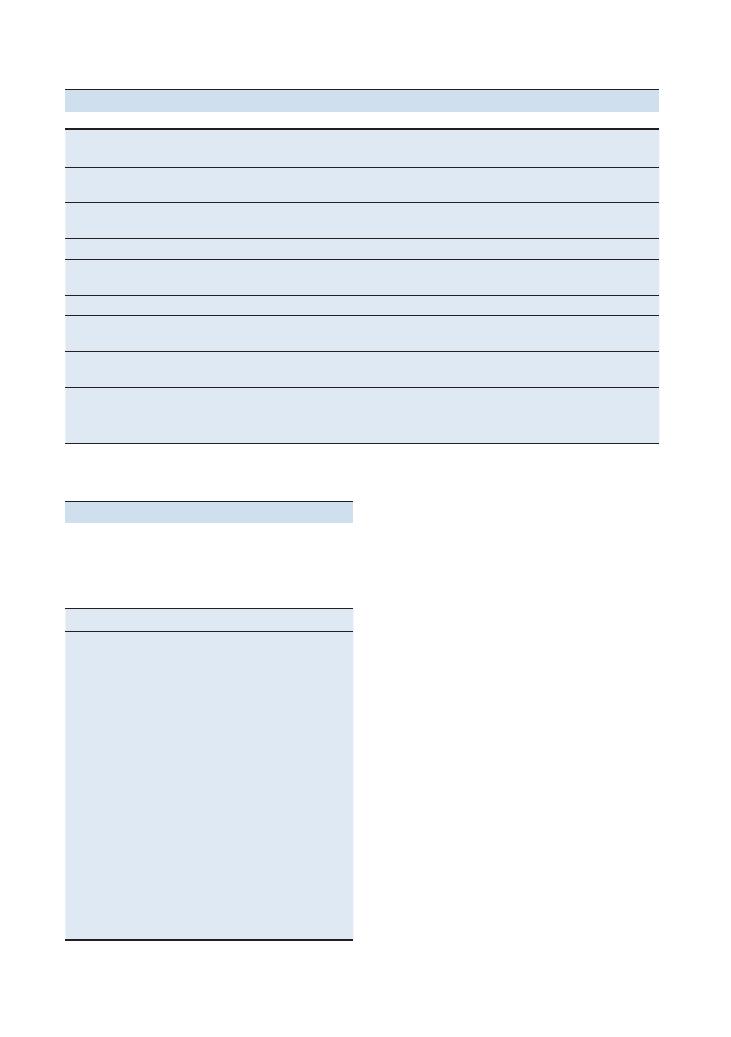

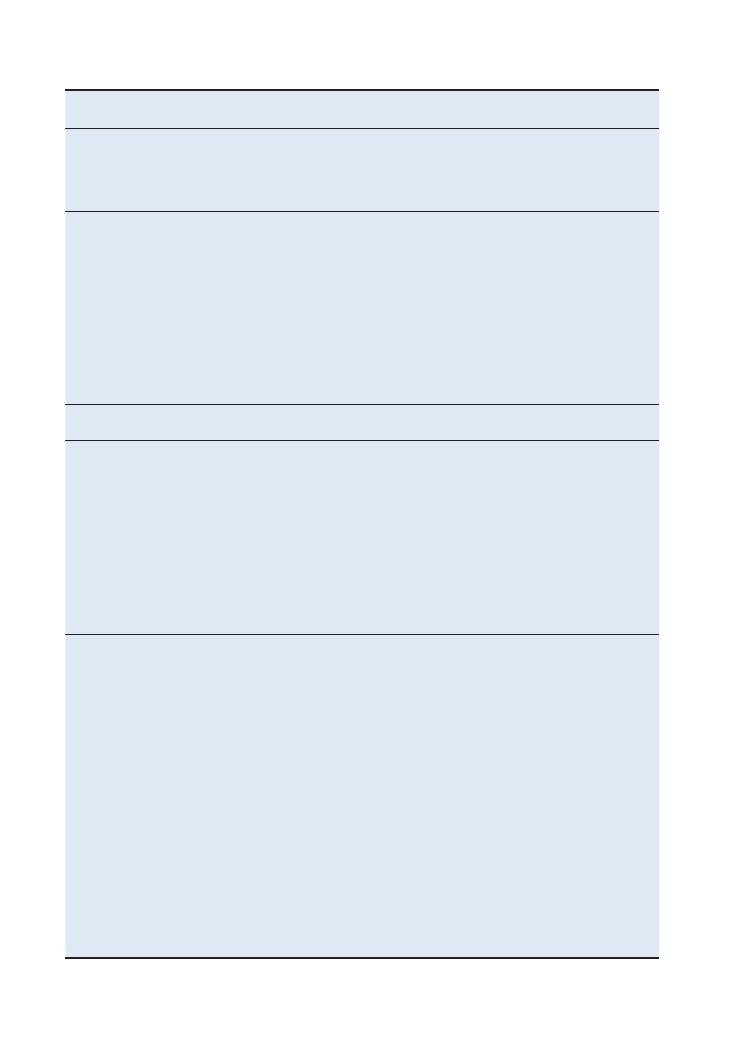

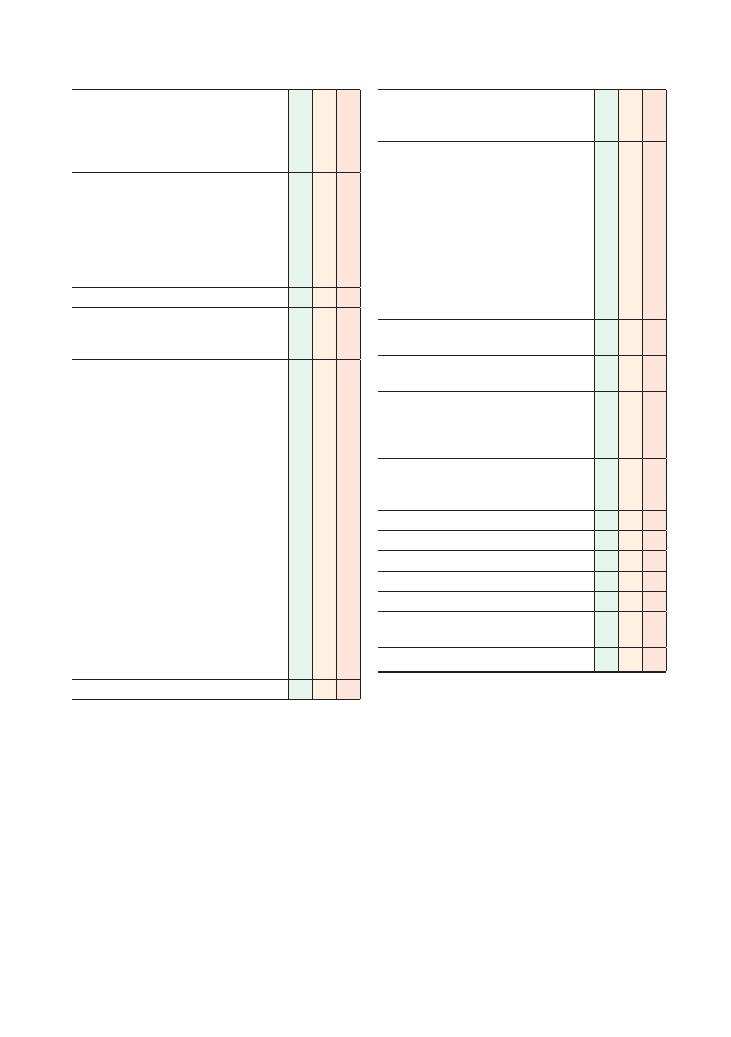

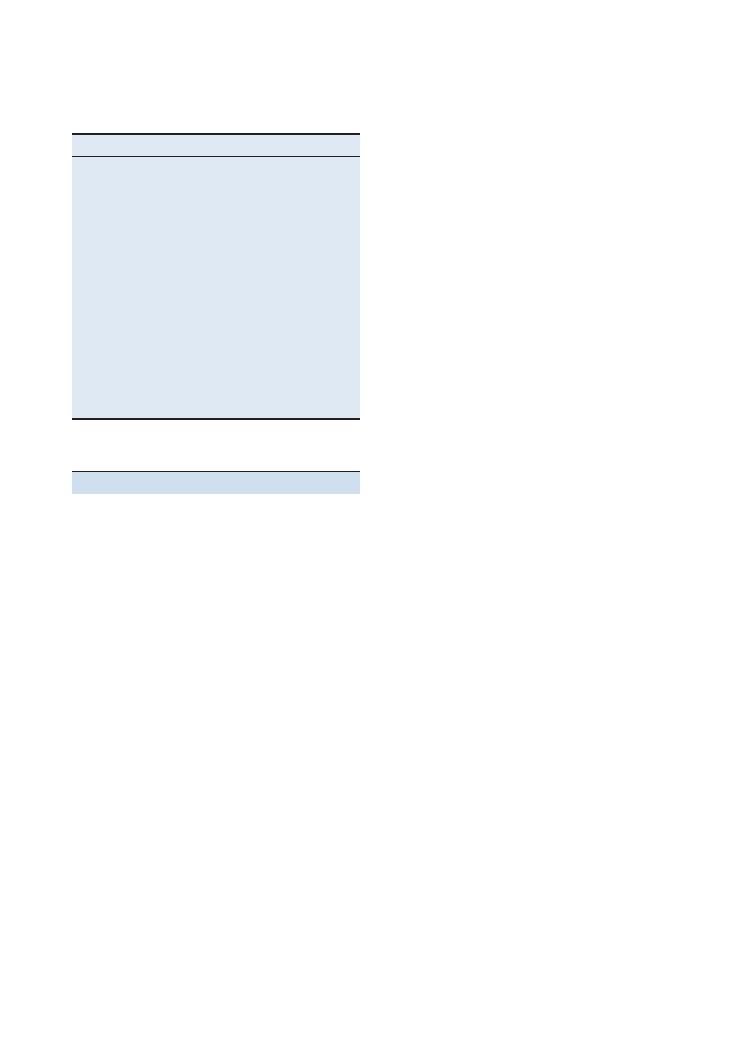

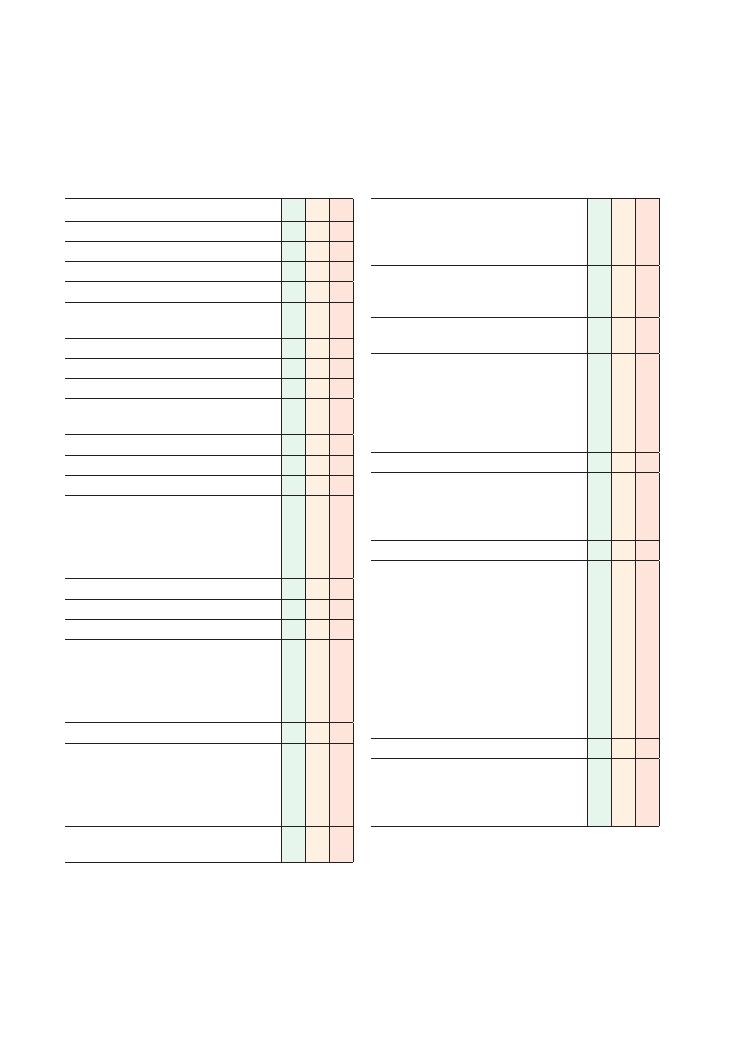

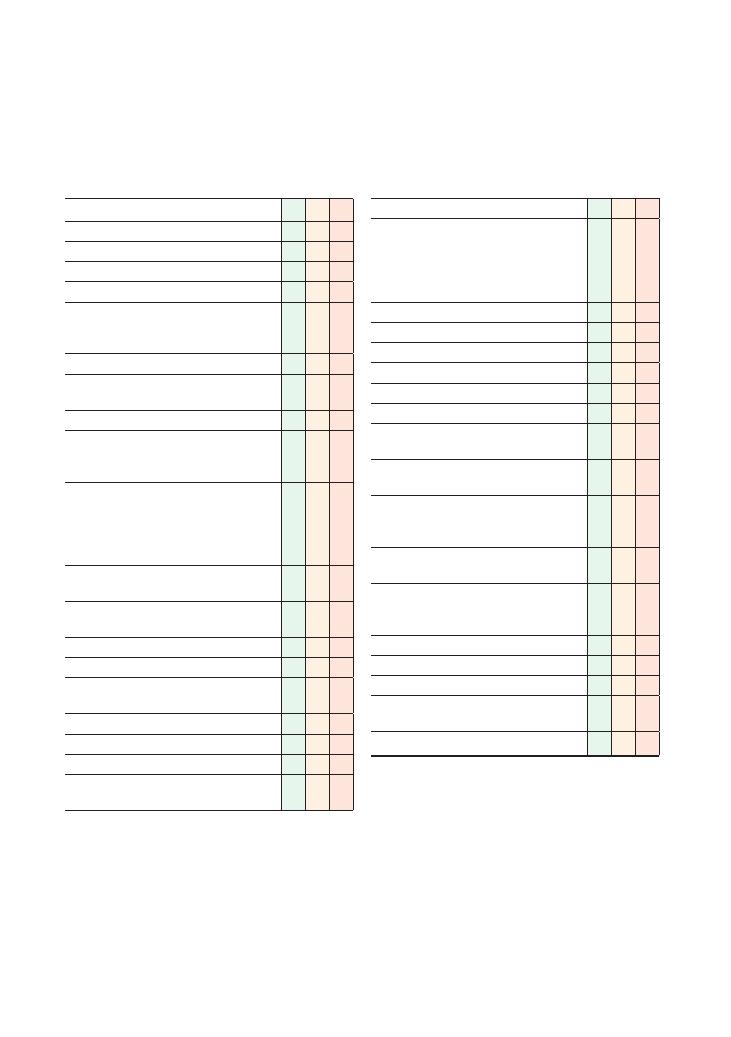

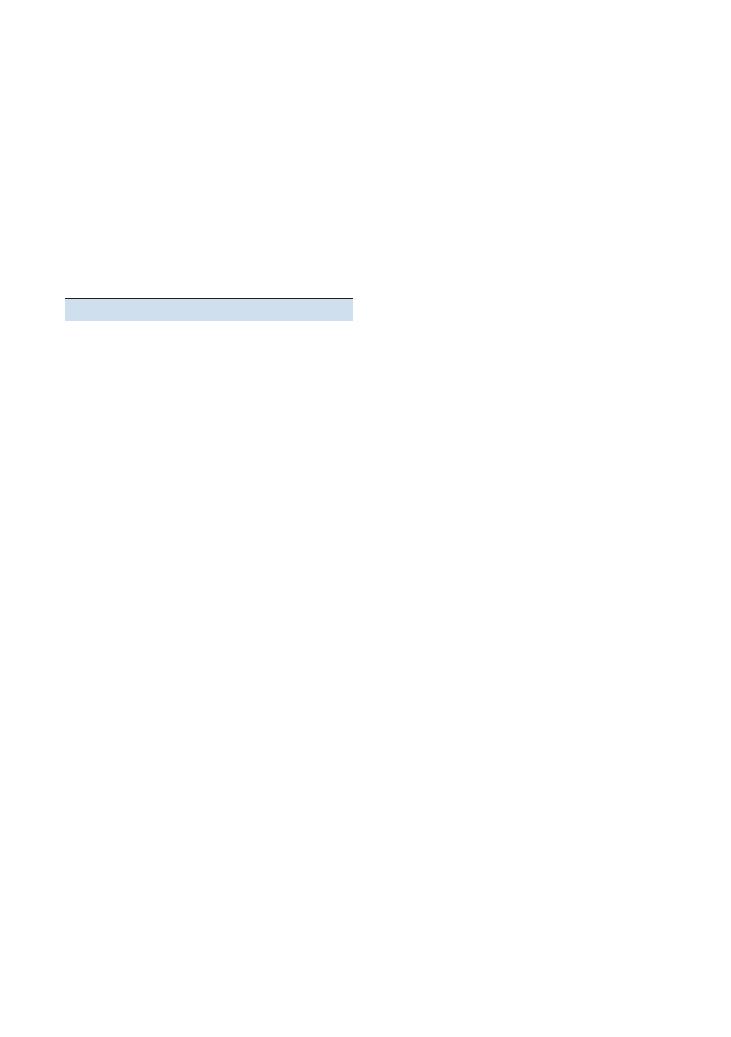

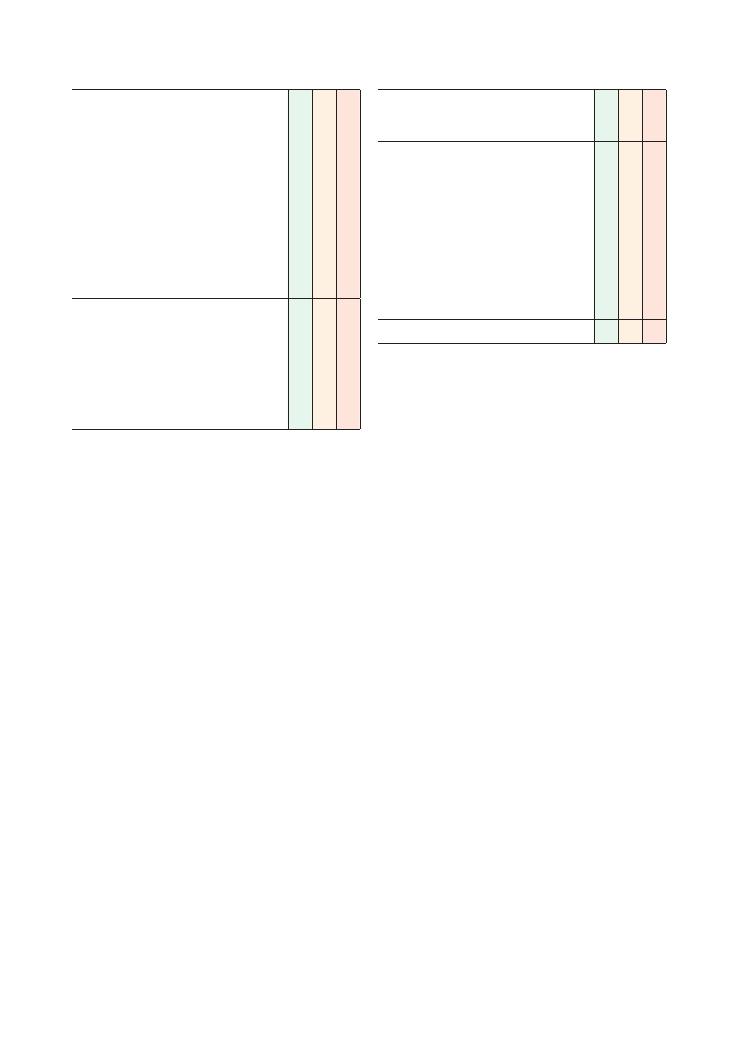

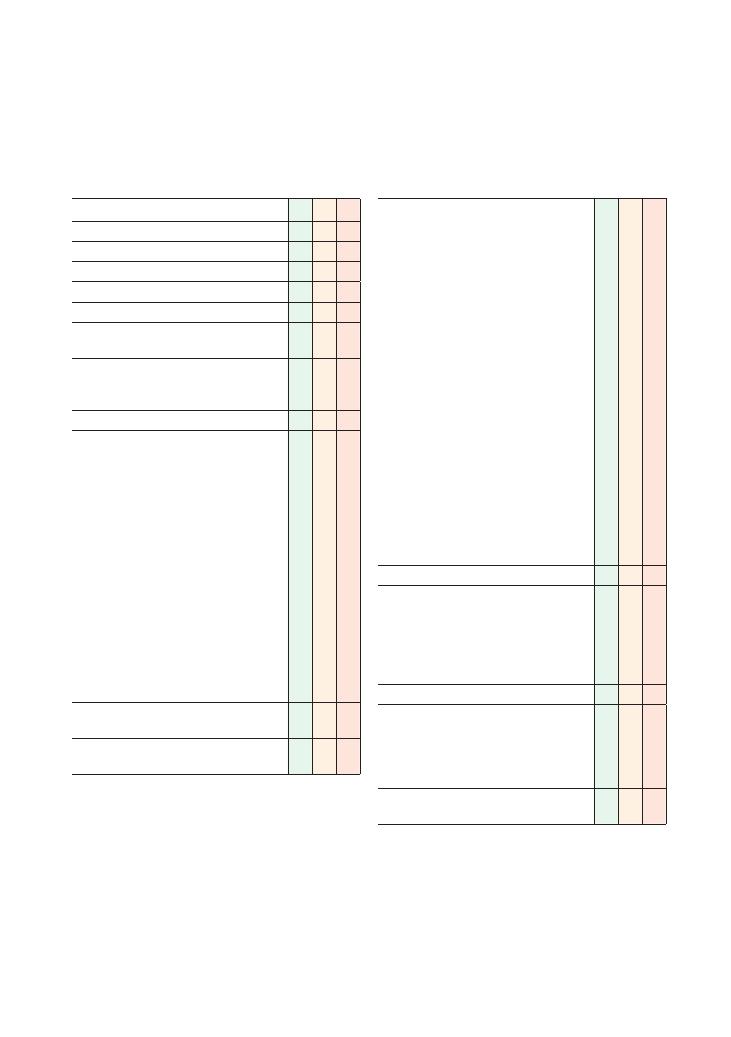

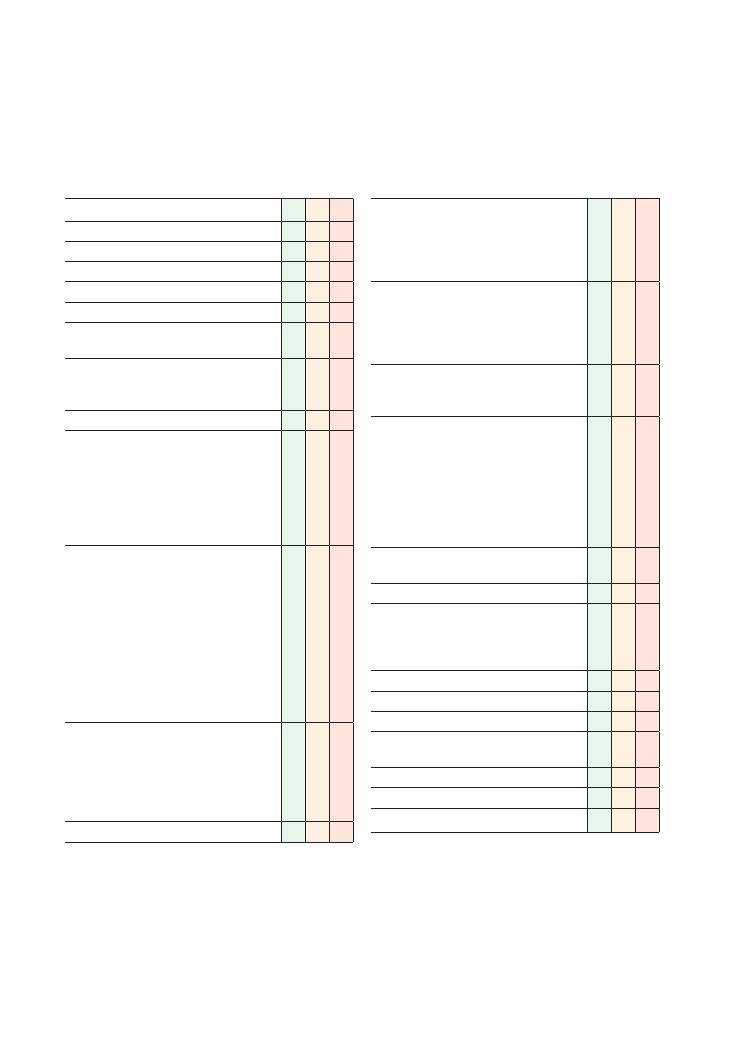

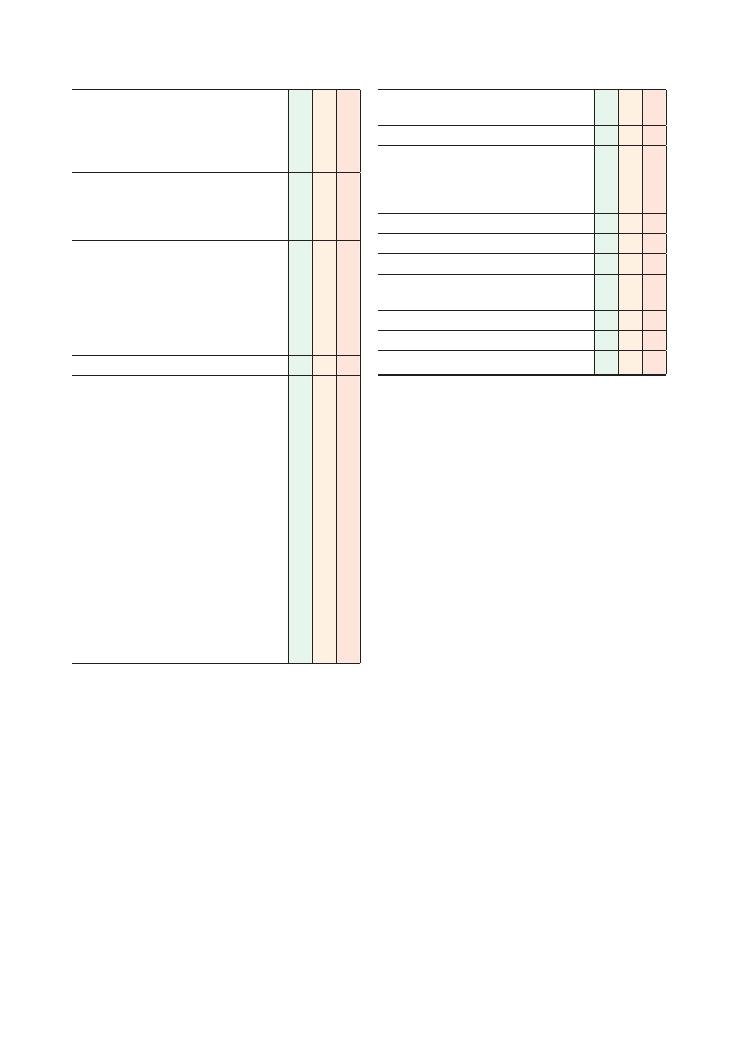

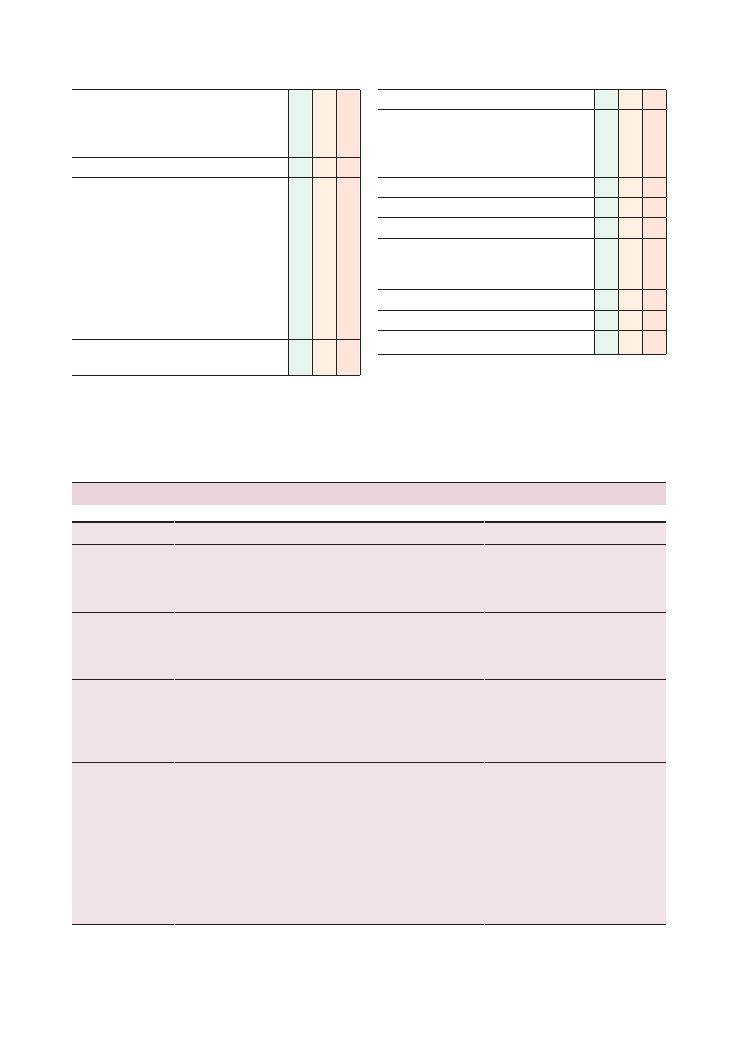

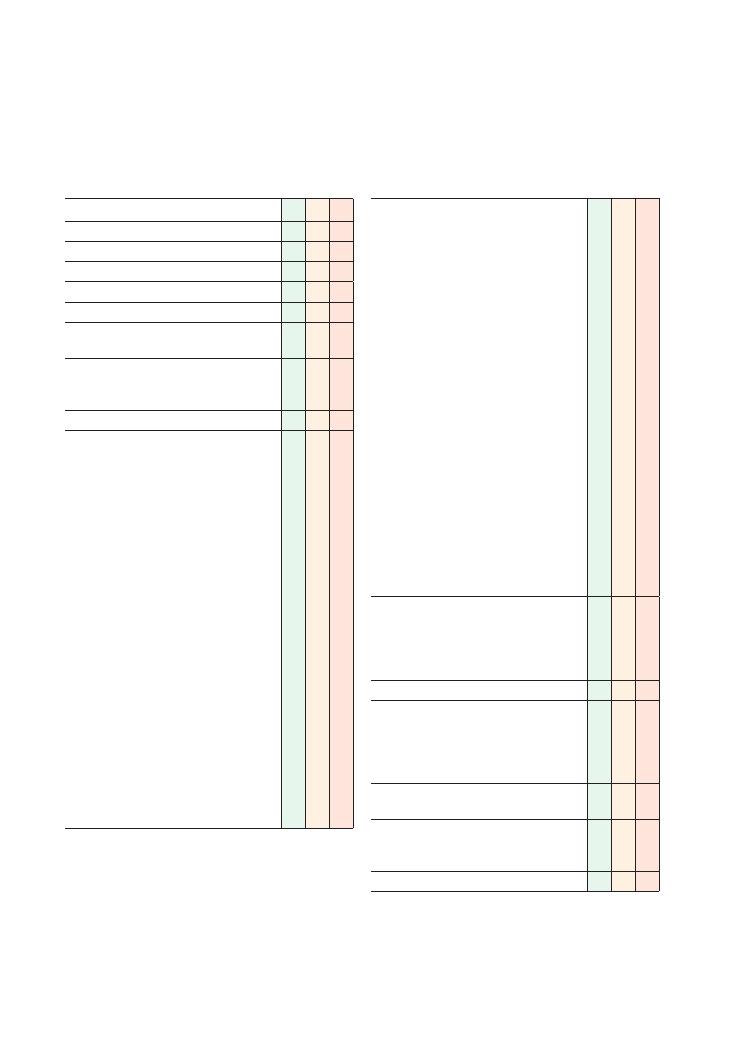

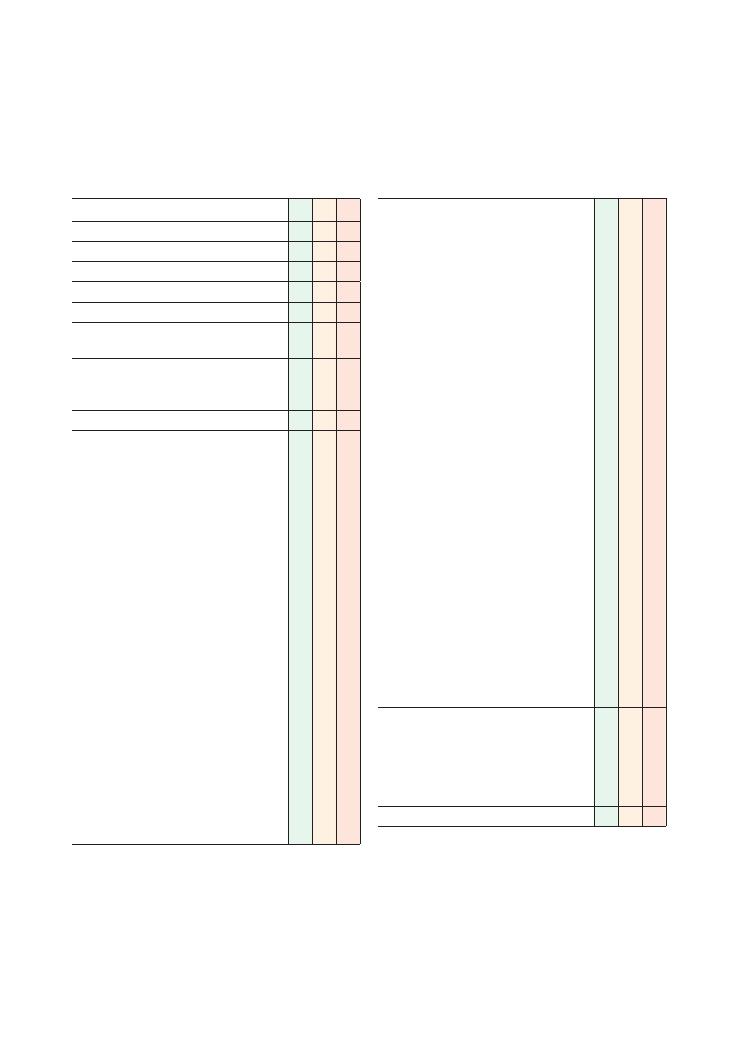

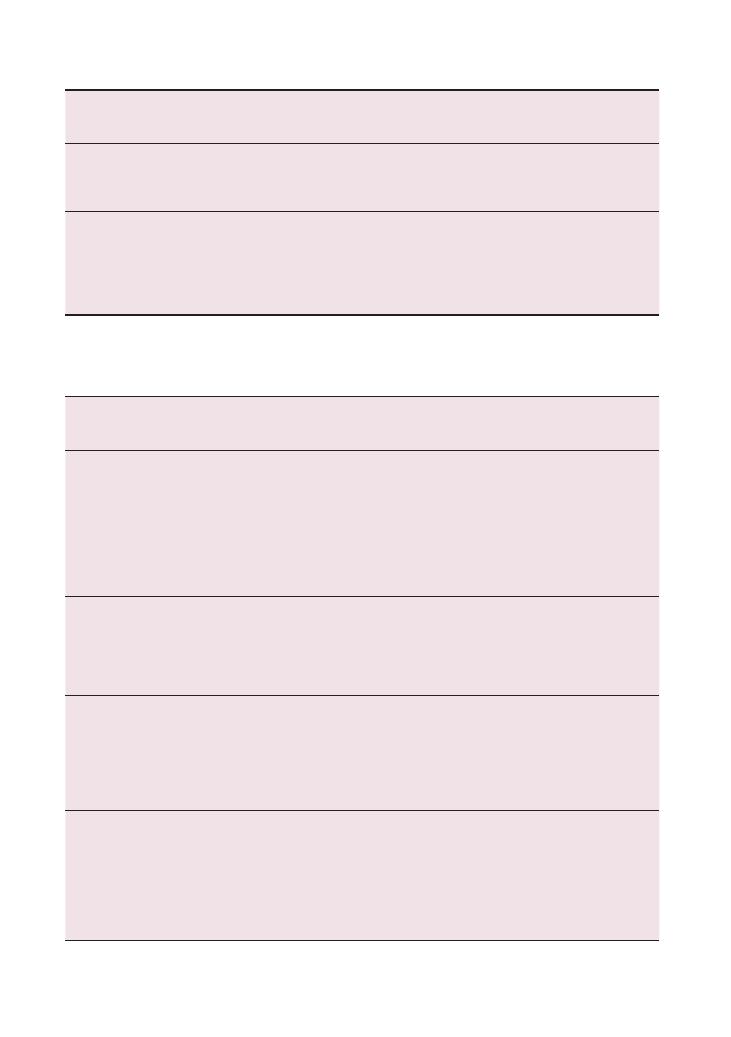

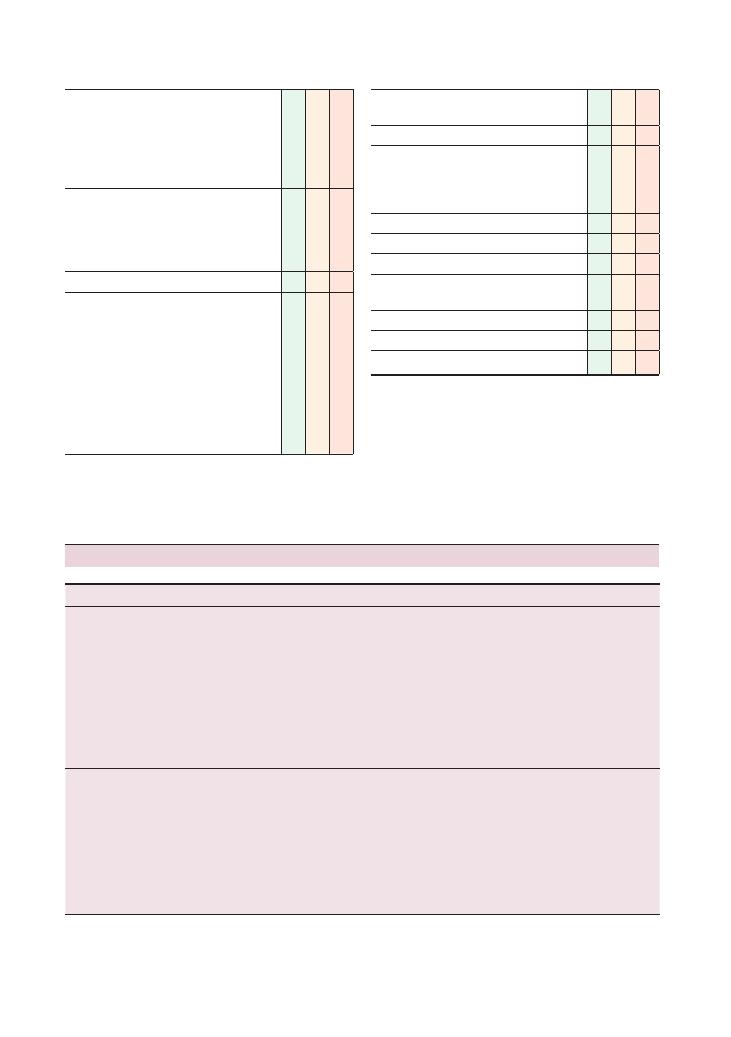

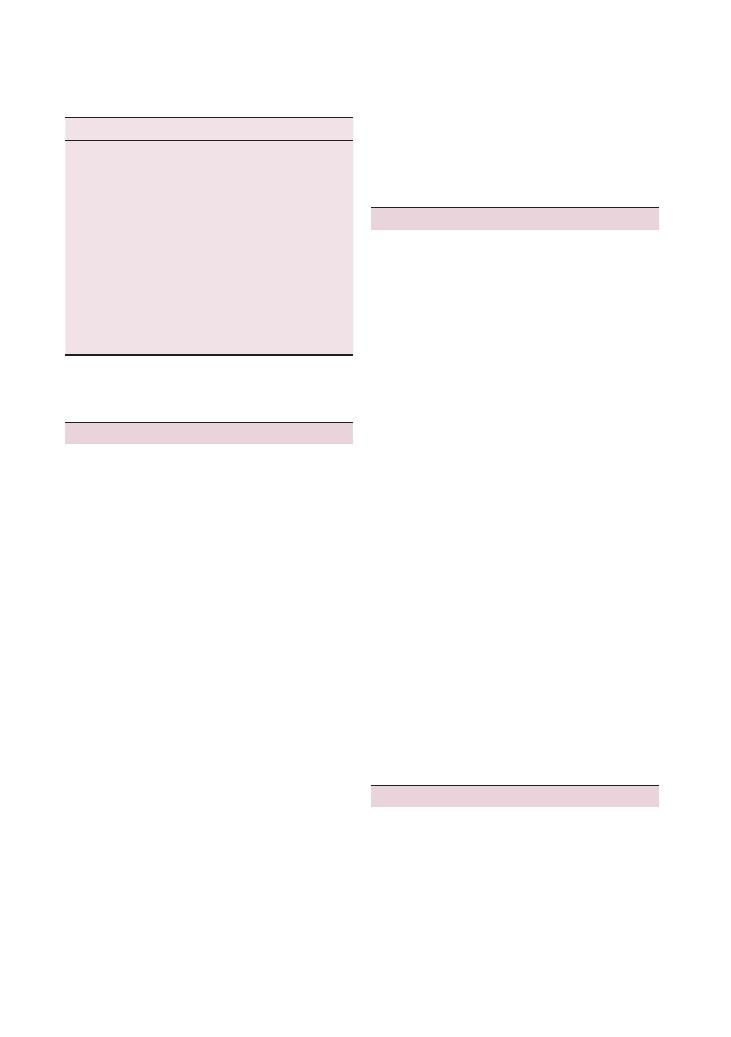

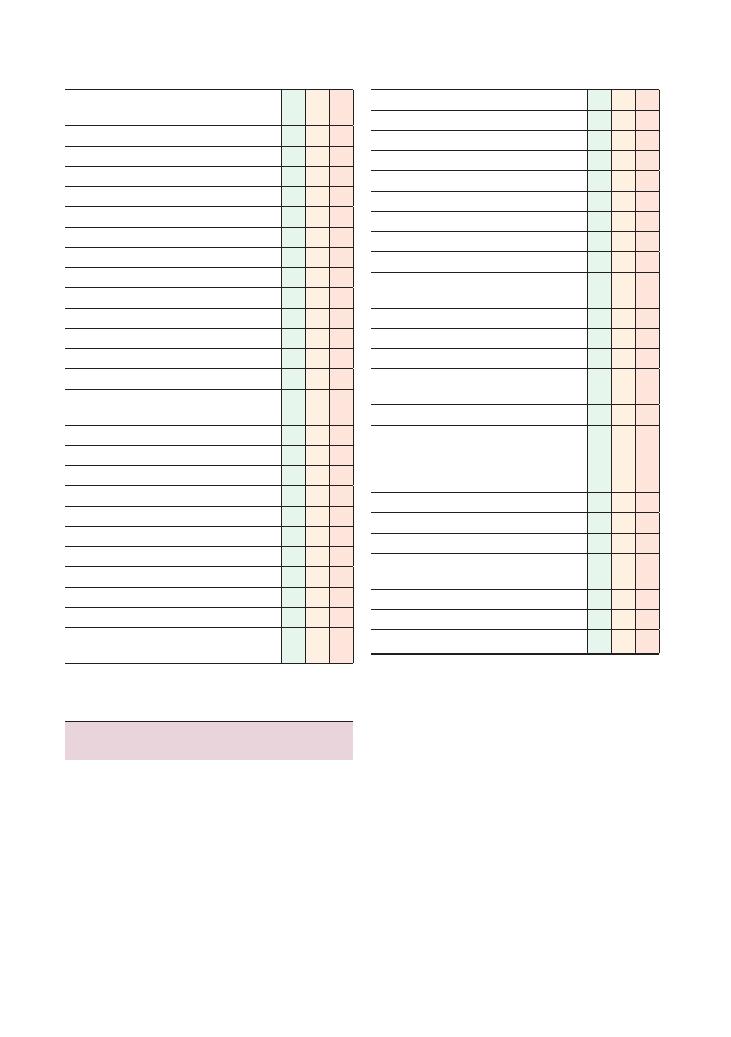

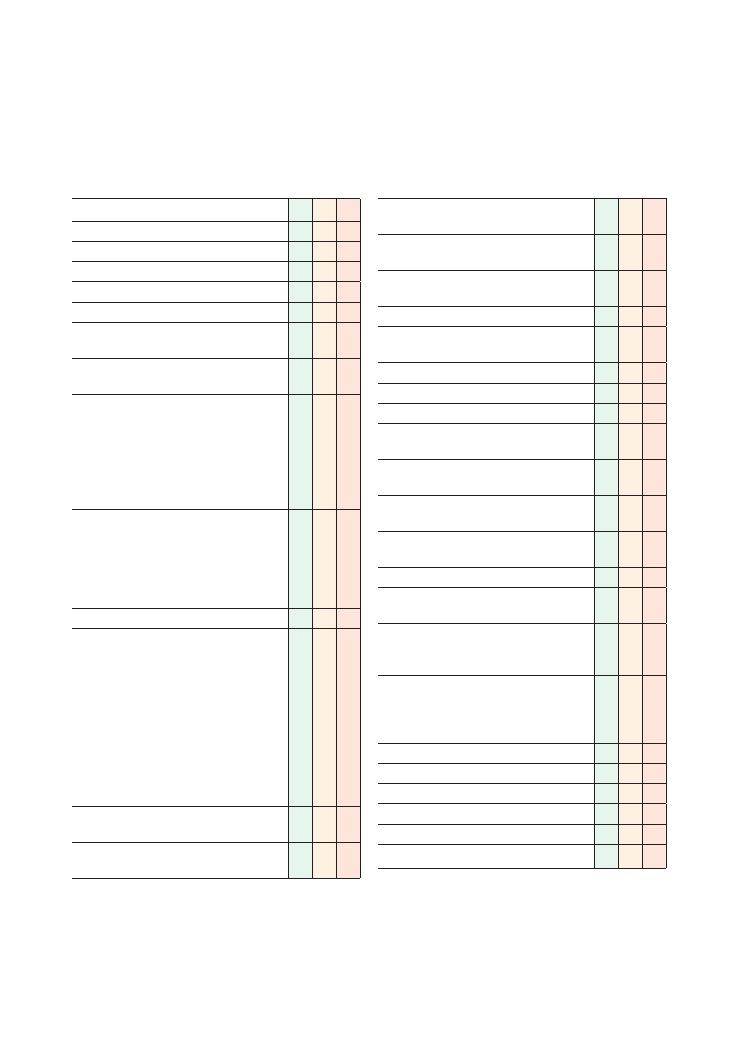

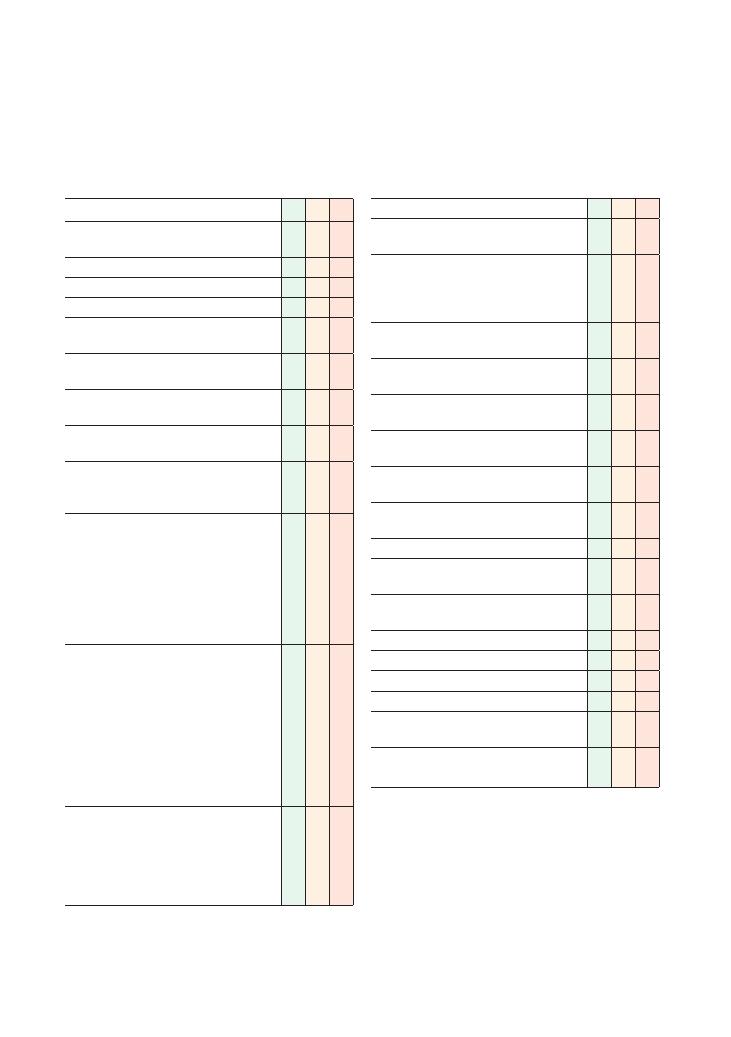

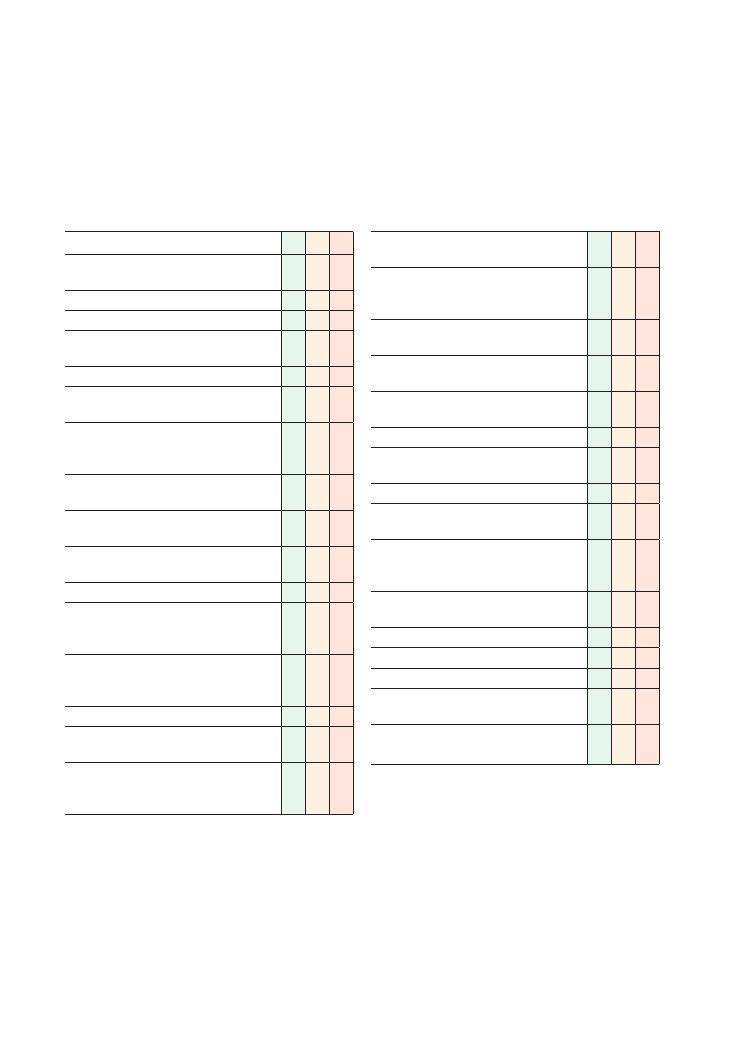

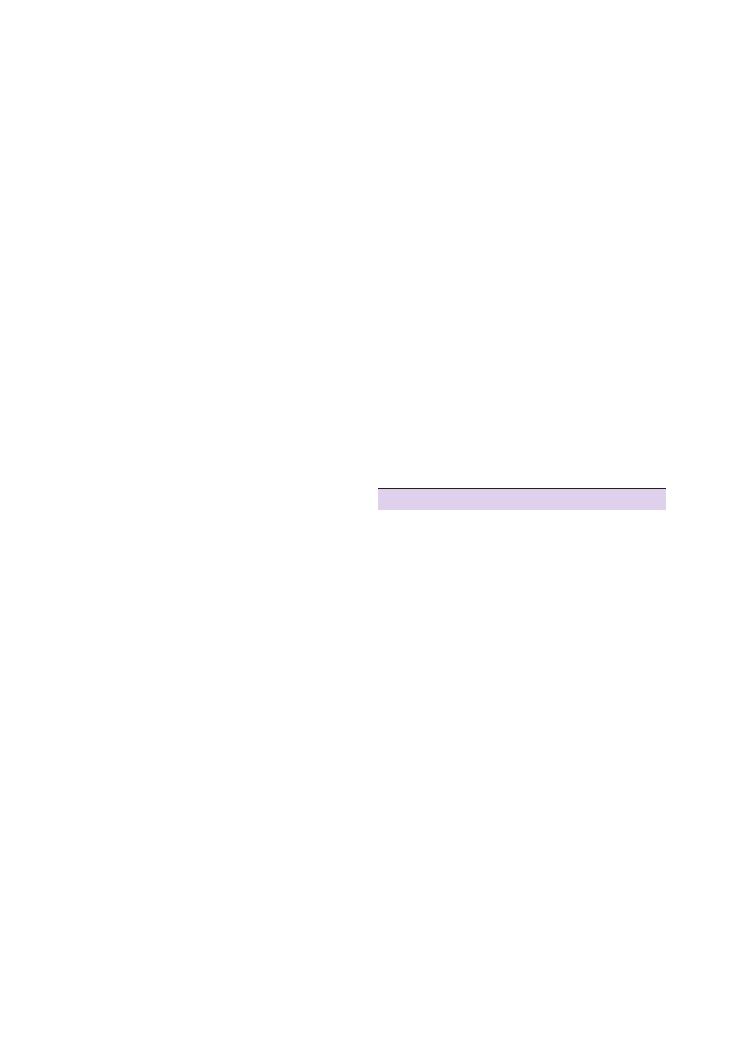

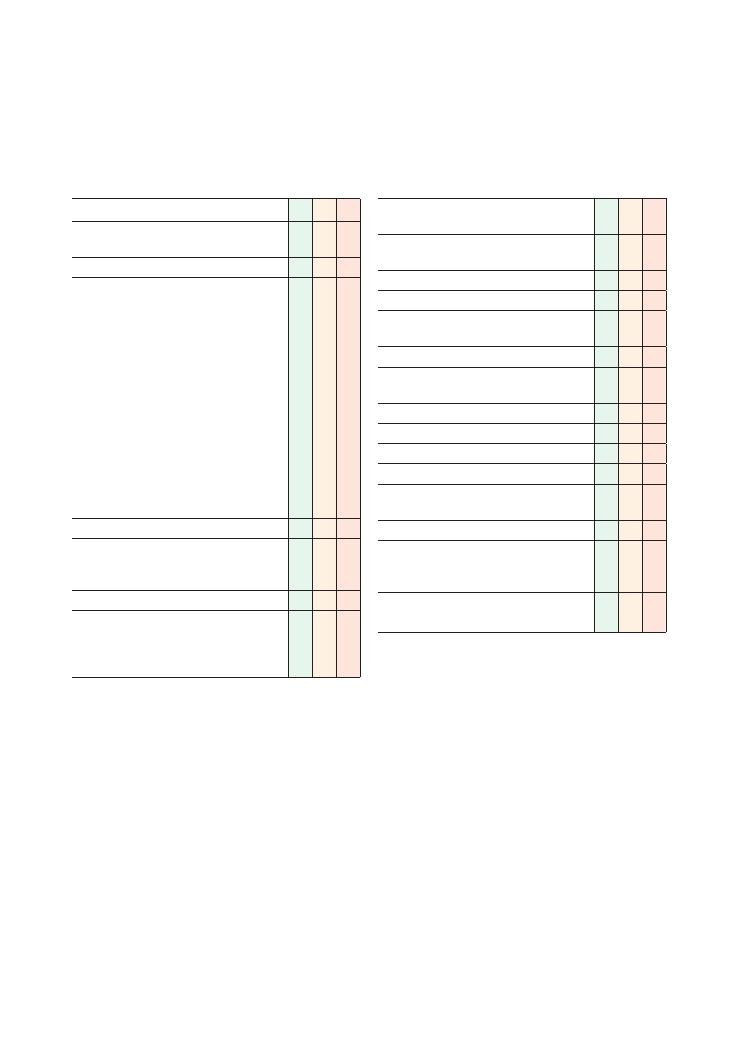

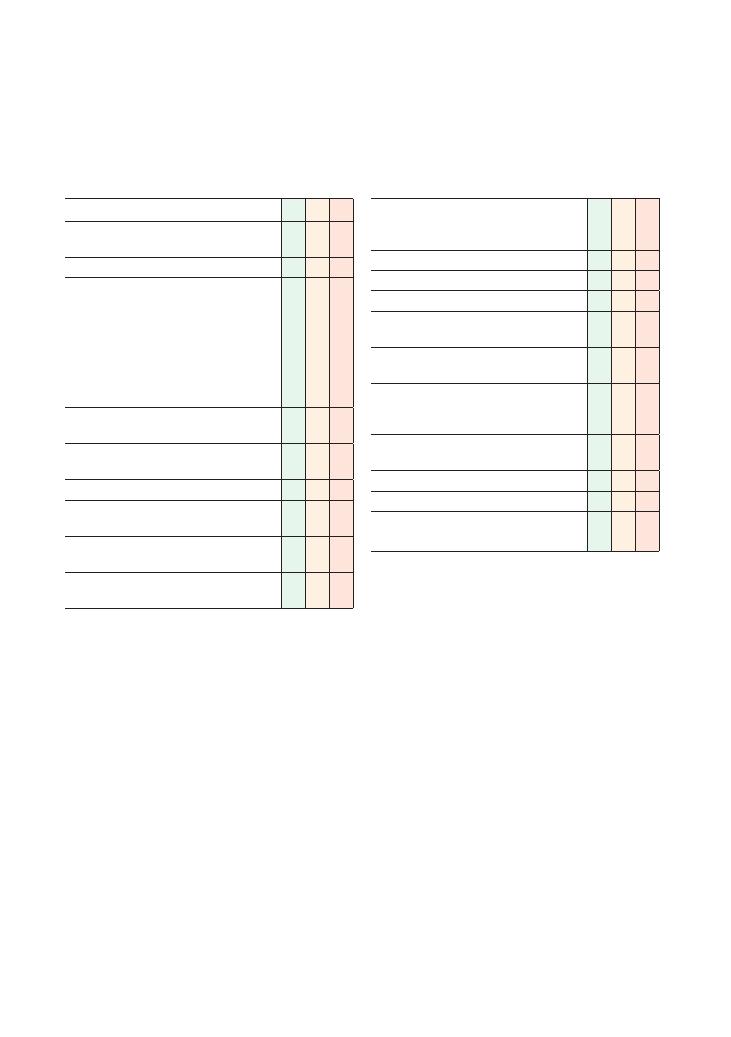

Checklist

P

MP

F

HELP:

H: ‘Hello’ (introduction and gains consent)

E: Exposure

L: Lighting

P: Positions at 45 degrees, asks if the patient is

in any pain

Washes hands

Inspects from end of bed:

• Looks at the front and back for thoracotomy

scars

• Sputum pots (bronchiectasis, COPD)

• Oxygen cylinders (COPD)

• Inhalers (COPD, asthma)

• Immuosuppressants (pulmonary fibrosis)

• Nebulisers (COPD)

• Peak flow charts (asthma)

Hands:

• Clubbing (suppurative conditions, lung cancer,

fibrosis)

• Tar staining

• Wasting of small muscles

Tremor

+ CO

2

retention flap

Radial pulse

Respiratory rate

Eyes:

• Horner syndrome (Pancoast syndrome)

• Anaemia

Face:

• Plethora (polycythaemia)

Mouth:

• ‘CDD’ (central cyanosis, dental hygiene,

dehydration)

Checklist

P

MP

F

Neck:

• JVP (raised

>4 cm) in cor pulmonale

• Palpates lymph nodes

• Tracheal deviation

• Cricoid–suprasternal notch distance (

<three

finger breadths in hyperinflation)

Palpates:

• Palpates apex beat

• Measures chest expansion (6–8 cm is normal)

at three places on the anterior and three on

the posterior chest

Percusses:

• Percusses at three positions on the anterior

and three on the posterior chest

Auscultates:

• Auscultates at three positions on the anterior

and three on the posterior chest

• Auscultates axillae to listen for right middle

lobe signs

• Auscultates for vocal fremitus

Palpates shins or ankles for peripheral oedema

Thanks patient

Offers to help patient get dressed

Washes hands

Presents findings

Offers appropriate differential diagnosis

Suggests appropriate further investigations and

management

OVERALL IMPRESSION:

8

Examinations:

2 Respiratory

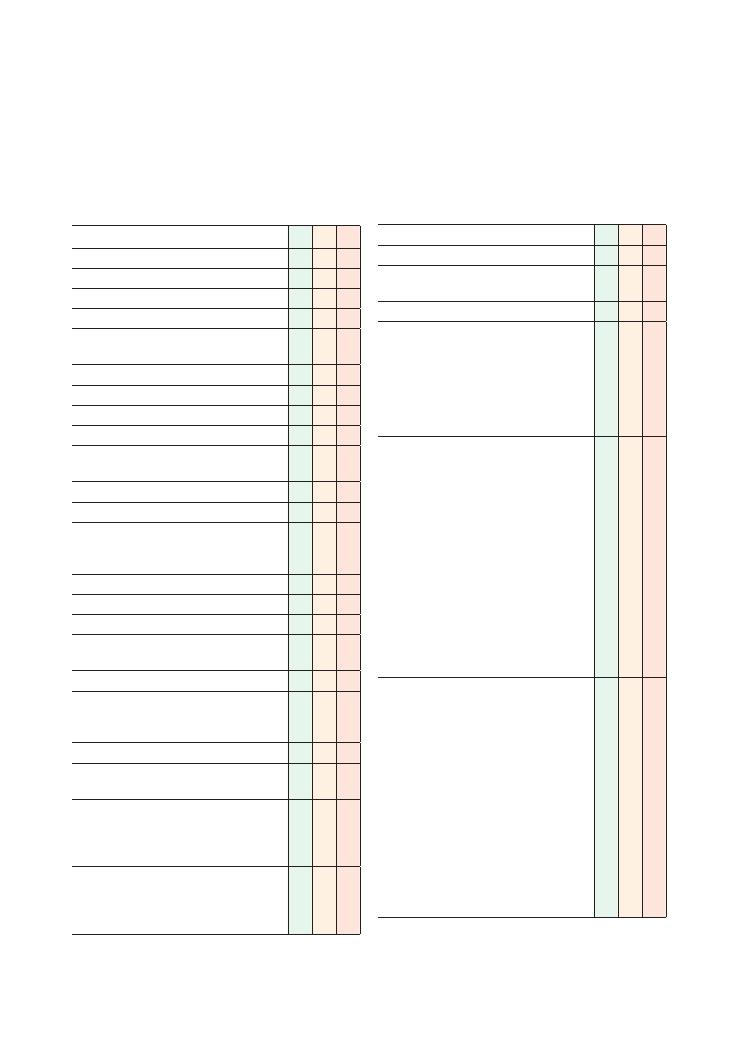

Summary of common conditions seen in OSCEs

Condition

Key finding

Chest

expansion

Percussion

Auscultation

Vocal

fremitus

Pulmonary

fibrosis

Fine end-inspiratory

crackles

Decreased

bilaterally

Normal/mild decrease at

bases

Fine end-inspiratory

crepitations

Normal/increased

at bases

Pneumothorax

Increased resonance

Decreased

unilaterally

Increased resonance

Decreased breath sounds

at site of pneumothorax

Decreased

Pleural effusion

Stony dull bases

Normal

Dull on side of effusion

Dull base(s)

Decreased at base

COPD/asthma

Wheeze

Normal

Normal

Wheeze

+ scattered

crepitations in COPD

Normal

Lobectomy

Scar

Normal

Dull at site of lobectomy

Normal

Normal

Pneumonectomy

Scar

Decreased

unilaterally

Dull on side of

pneumonectomy

Absent on side of

pneumonectomy

Decreased

Bronchiectasis

Sputum pot,

crackles, clubbing

Normal

Normal

Normal

Normal

Consolidation

Crackles

concentrated in

one area

Normal

Normal

Normal/increased at site

of consolidation

Normal/increased

at site of

consolidation

Findings

Condition

Young, thin, short patient with a PEG

site near the umbilicus and a

tunnelled catheter at the axilla or on

the chest

Bronchiectasis

secondary to

cystic fibrosis

Middle-aged patient with full sputum

pot

Bronchiectasis

Cushingoid features (high BMI, bruising,

striae) and bruising (from steroid use)

Pulmonary fibrosis

Features of rheumatological disease, e.g.

rheumatoid hands (ulnar deviation,

swollen metacarpophalangeal joints,

swan neck deformity) or scleroderma

(beak-shaped nose, small mouth,

tight skin, telangiectasia)

Pulmonary fibrosis

Elderly patient with tar-stained

fingernails and an oxygen cylinder at

the bedside

COPD

Characteristic scars (with pictures)

Lobectomy/

pneumonectomy

Hints and tips for the exam

Inspection

Inspection can often provide the diagnosis at the respi-

ratory station. There are some key stereotypical features

of a few conditions that can give the case away.

Timing

A common problem at the respiratory station is timing

as students find it difficult to listen to carefully all

the breath sounds in enough places during the 5–10

minutes they have.

Once you have completed your inspection, start

examining from the back. Most physicians will agree

that it is easier to percuss and auscultate at the back as

you have more surface area available. In addition, the

position of the heart often makes it difficult to establish

findings in the left lower zone of the lung anteriorly.

One of the ways you can minimise collateral time

losses is by reducing the time spent in changing the

patient’s position. When the patient is lying down,

palpate, percuss and auscultate the anterior aspect of the

chest. When he or she is sitting forwards, palpate, percuss

and auscultate the posterior aspect, and examine for

lymphadenopathy at the same time.

Lobectomies and pneumonectomies

These are very common in OSCEs as patients are

usually stable and ambulant, and the examination find-

ings are obvious. Students are often surprised when

they do not hear decreased breath sounds at the site of

lobectomy scars, which they may have done during

their ward attachments. This is because, after a few

months or years, patients with lobectomies develop

Examinations:

2 Respiratory 9

Questions you could be asked

Q. Why are spontaneous pneumothoraces more

common in tall men?

A. There are a number of theories for this. One is that

the difference between the intrapleural pressure of the

apex and the base is greater in taller people, making

it easier for a pneumothorax to form spontaneously.

Another is that any anatomical defects or blebs will

become more stretched if the length if the lung is

longer, as is the case in taller individuals.

Q. Why might you hear breath sounds over an area of

the lung that has been excised in a lobectomy?

A. See ‘Lobectomies and pneumonectomies’ above.

Q. Name three causes of bibasal crepitations with club-

bing in a patient.

A. See ‘Creps and clubbing’ above.

compensatory hyperinflation, and lung tissue fills up

areas it was removed from. This will not be the case

immediately after lobectomy surgery as sufficient time

has not surpassed for compensatory hyperinflation to

occur.

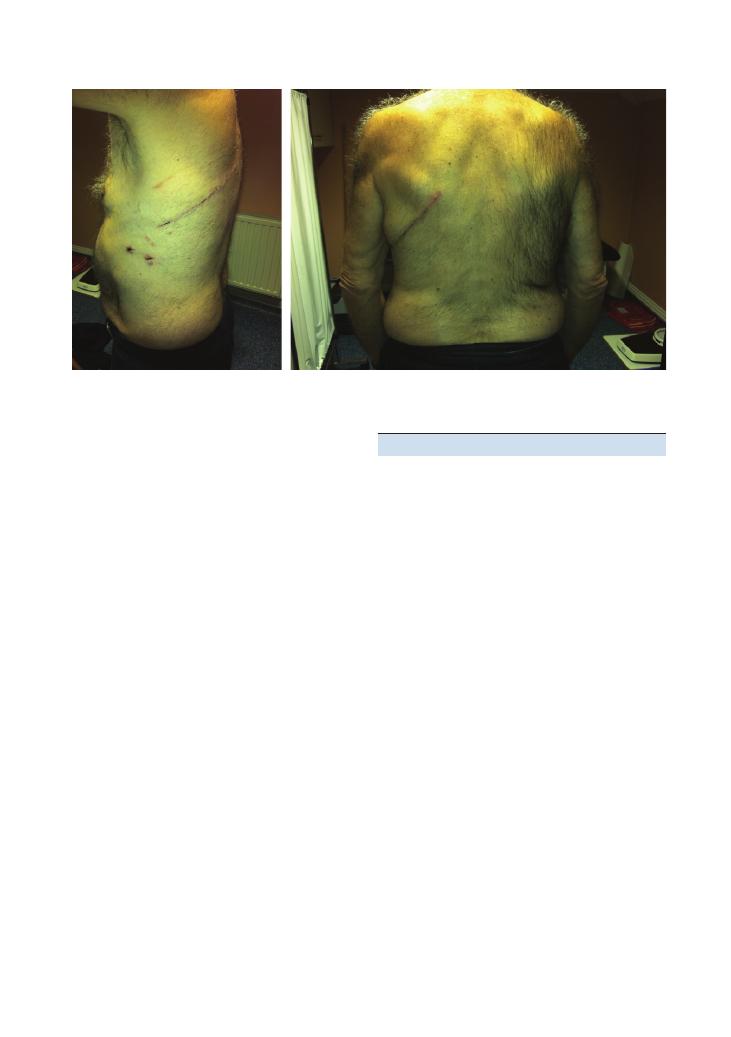

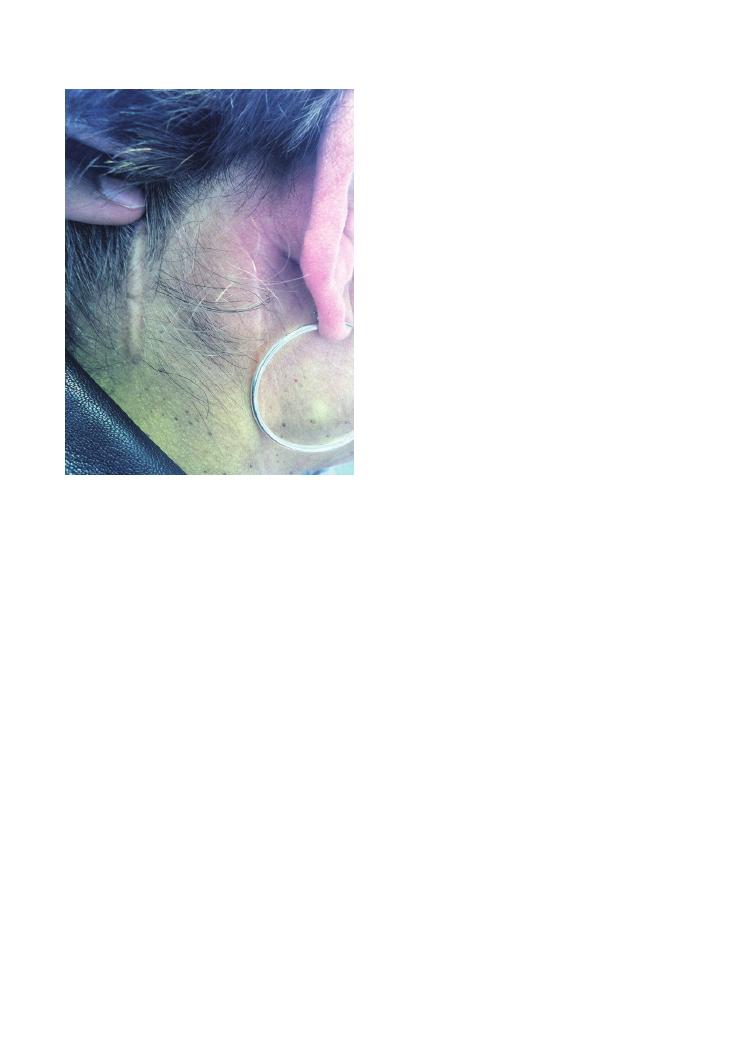

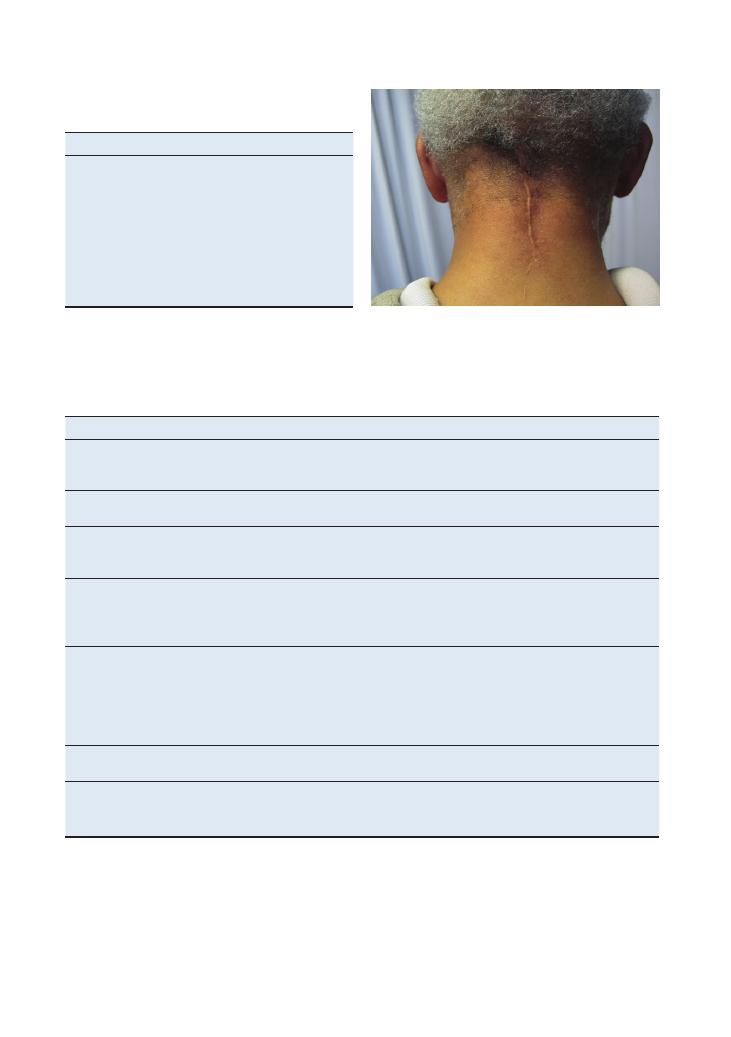

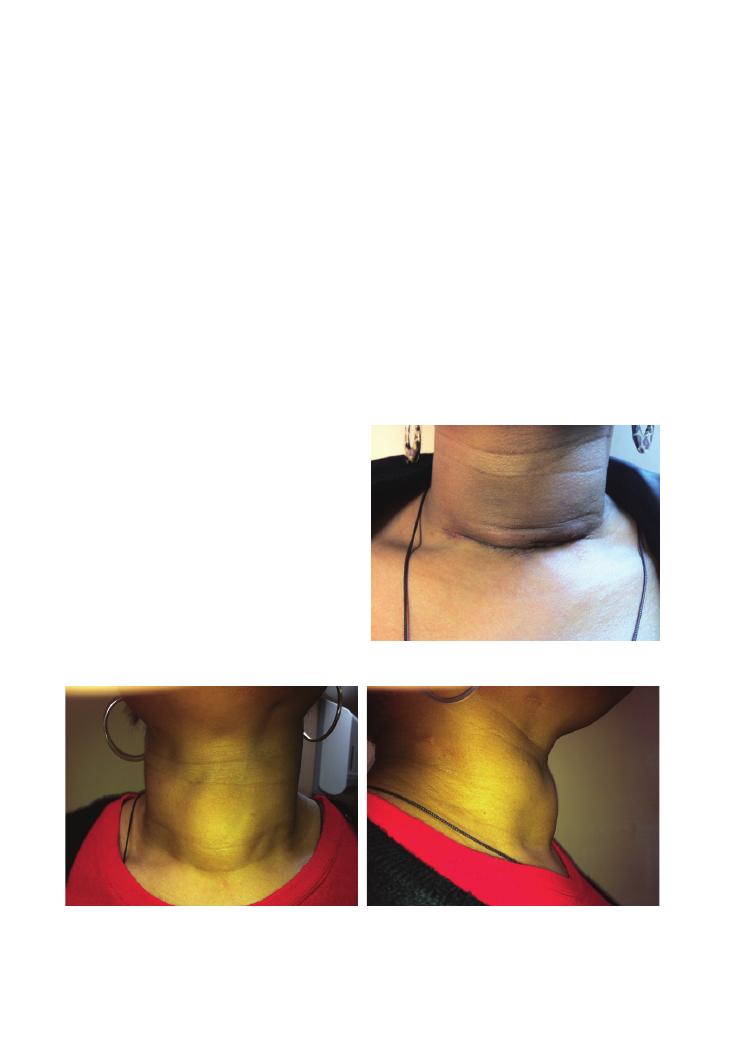

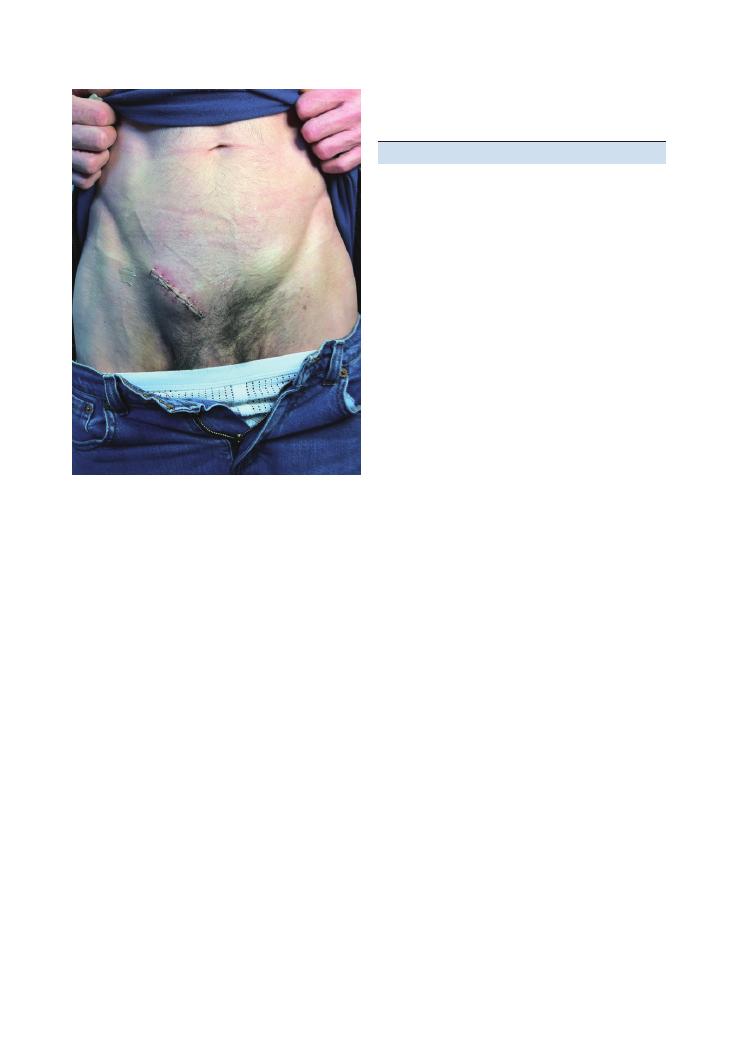

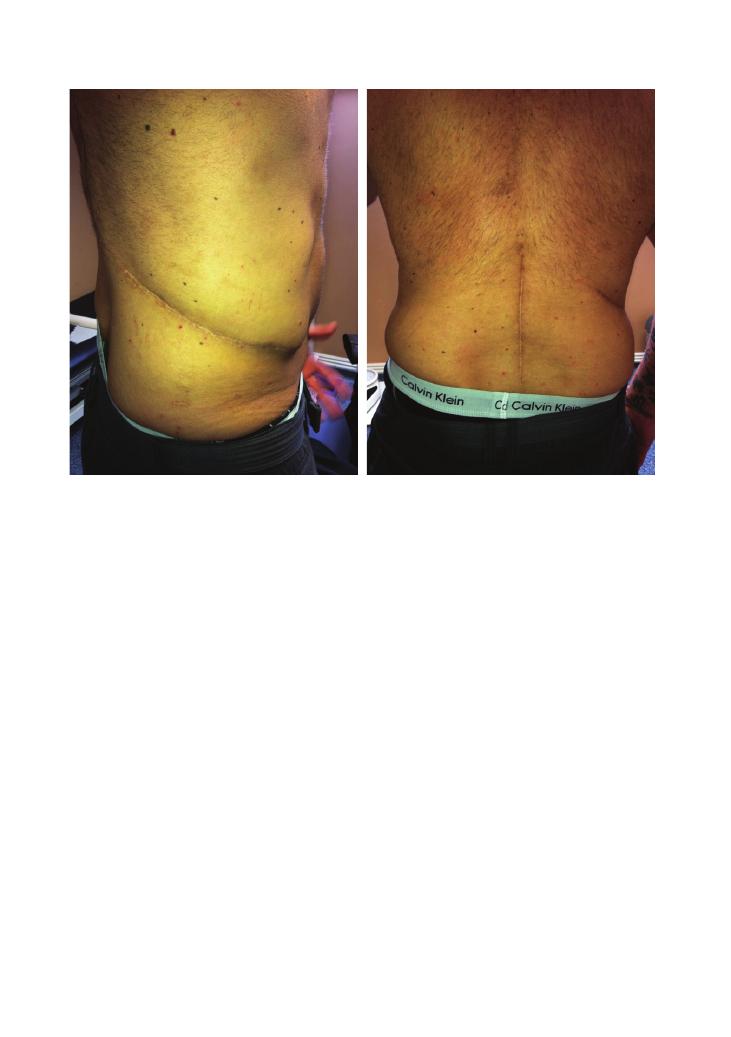

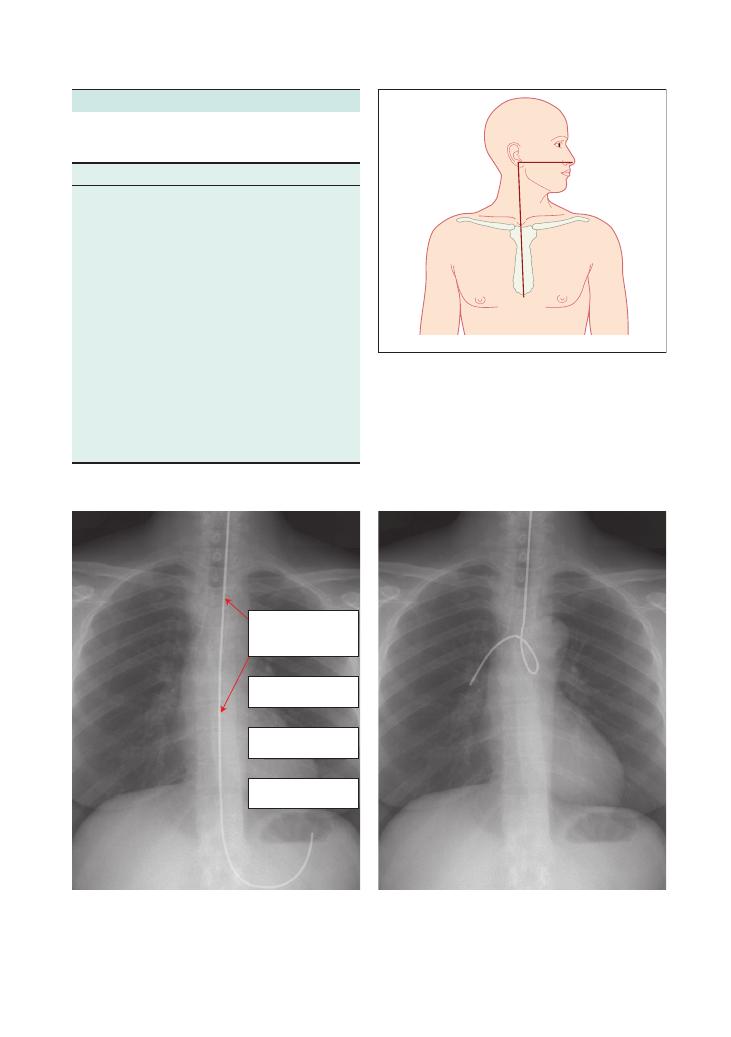

The scar from a pneumonectomy can be very similar

to the scar from a lobectomy (Figure 2.1), although they

can immediately be distinguished by the fact that chest

expansion and breaths sounds are usually completely

absent on the side of a chest that has undergone a

pneumonectomy.

‘Creps and clubbing’

Remember that bilateral crepitations and clubbing that

occur together most commonly present in patients with

bronchiectasis or pulmonary fibrosis.

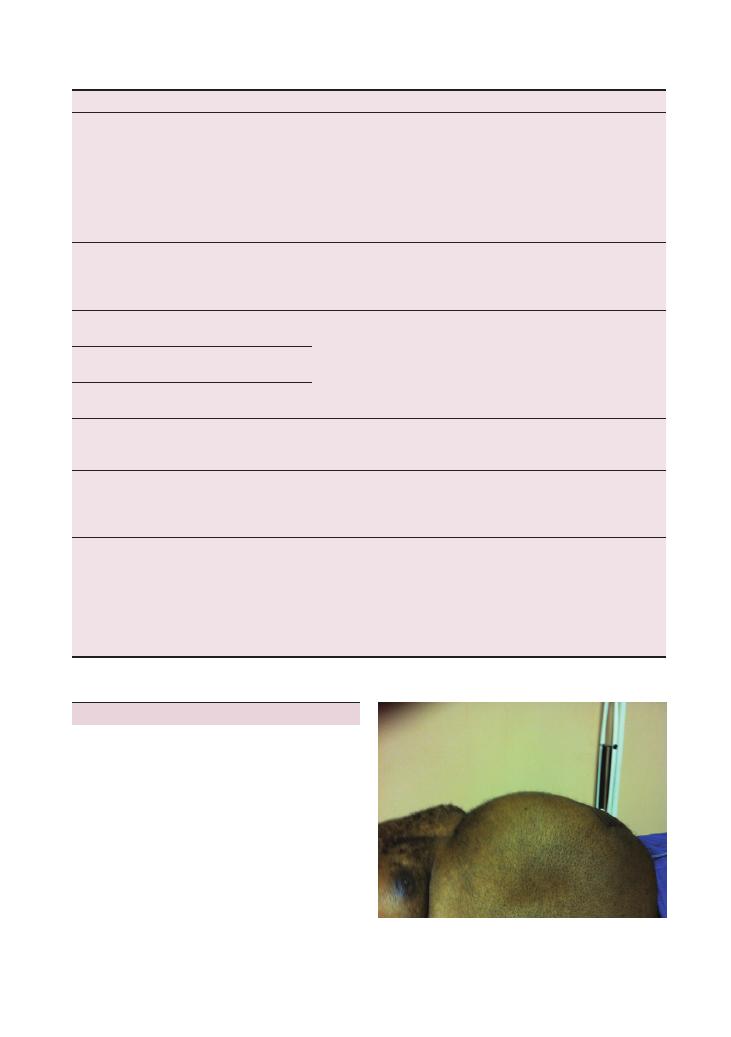

Figure 2.1 Lobectomy scar: side view (a) and back view (b)

(a)

(b)

10

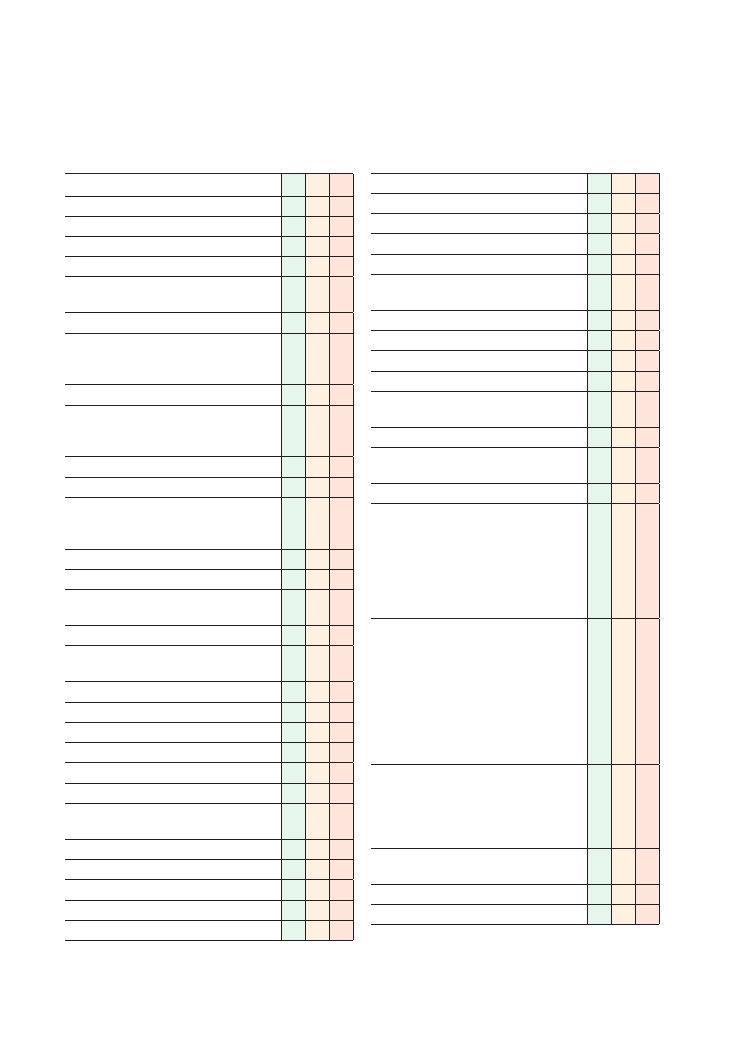

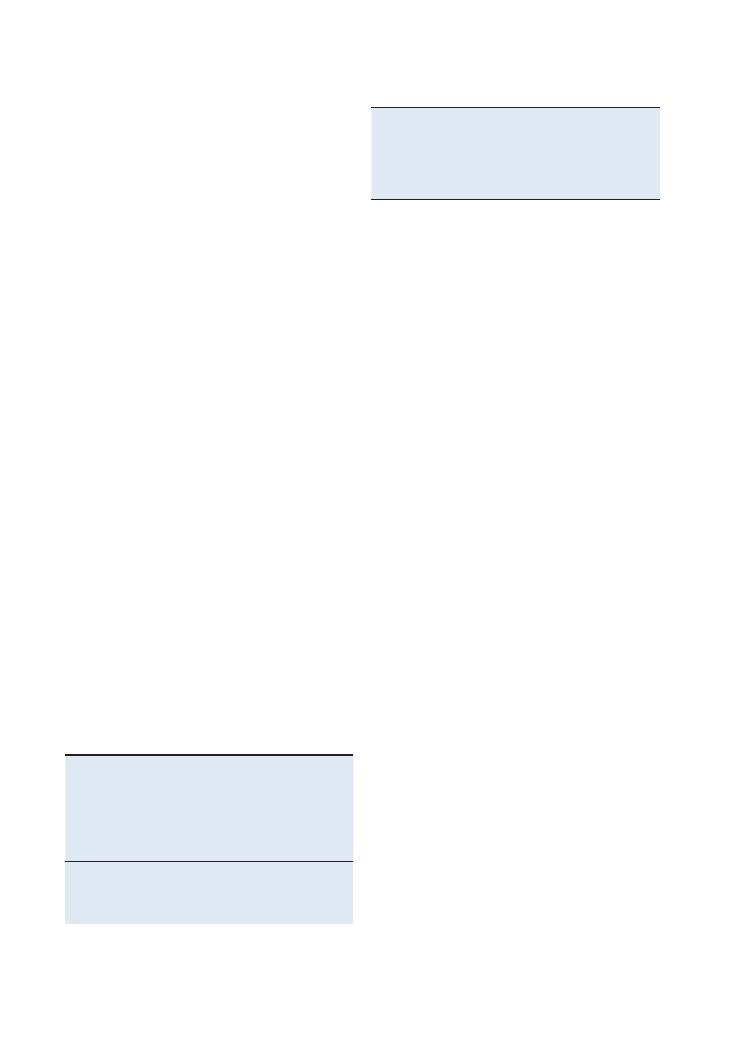

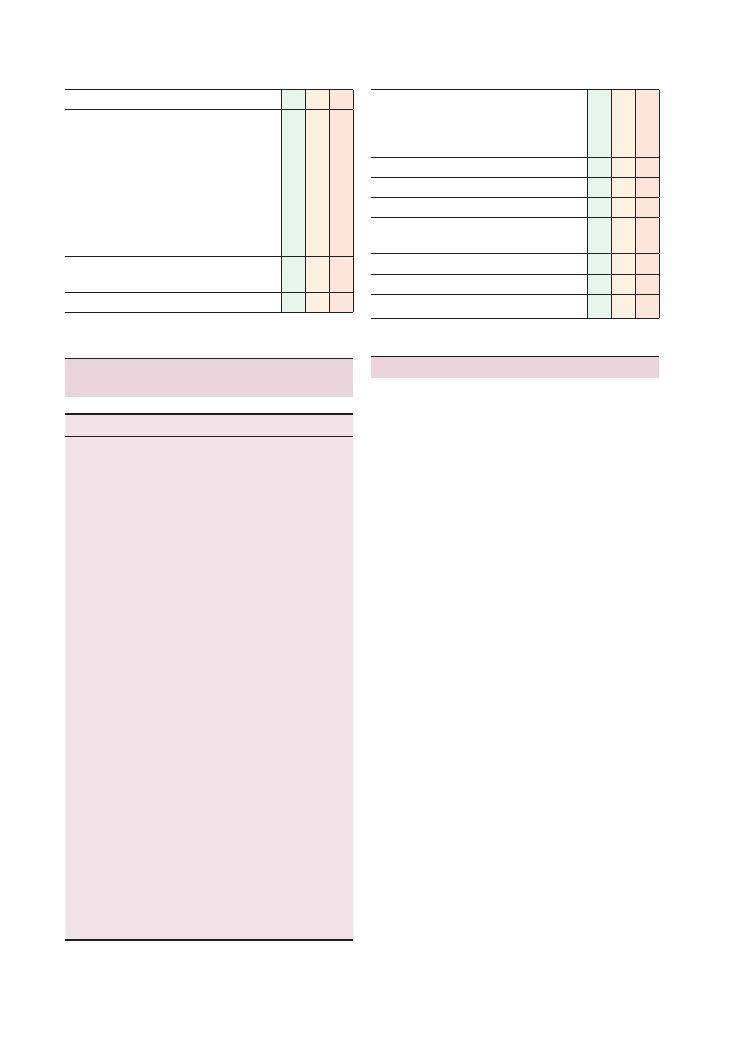

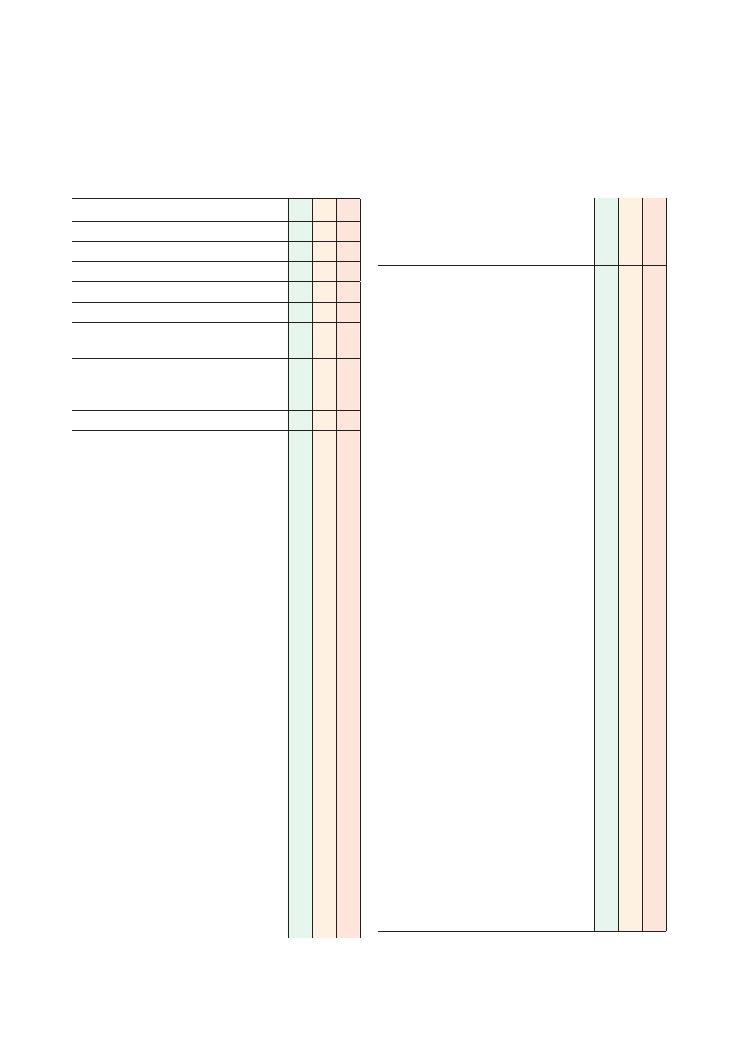

3 Abdominal

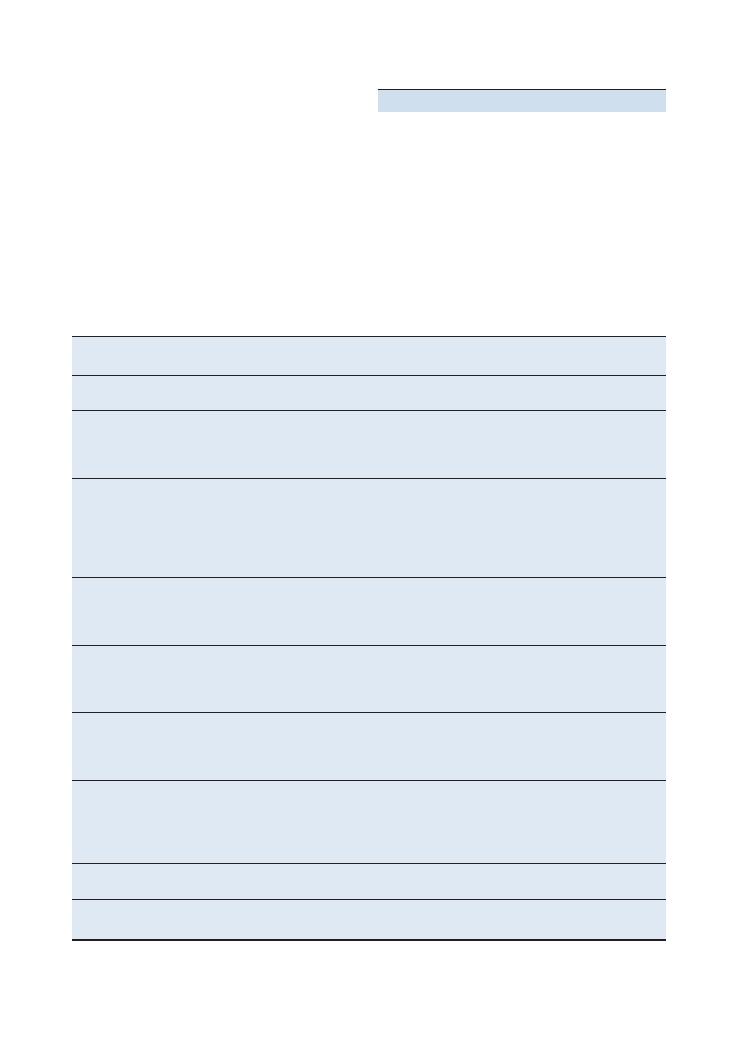

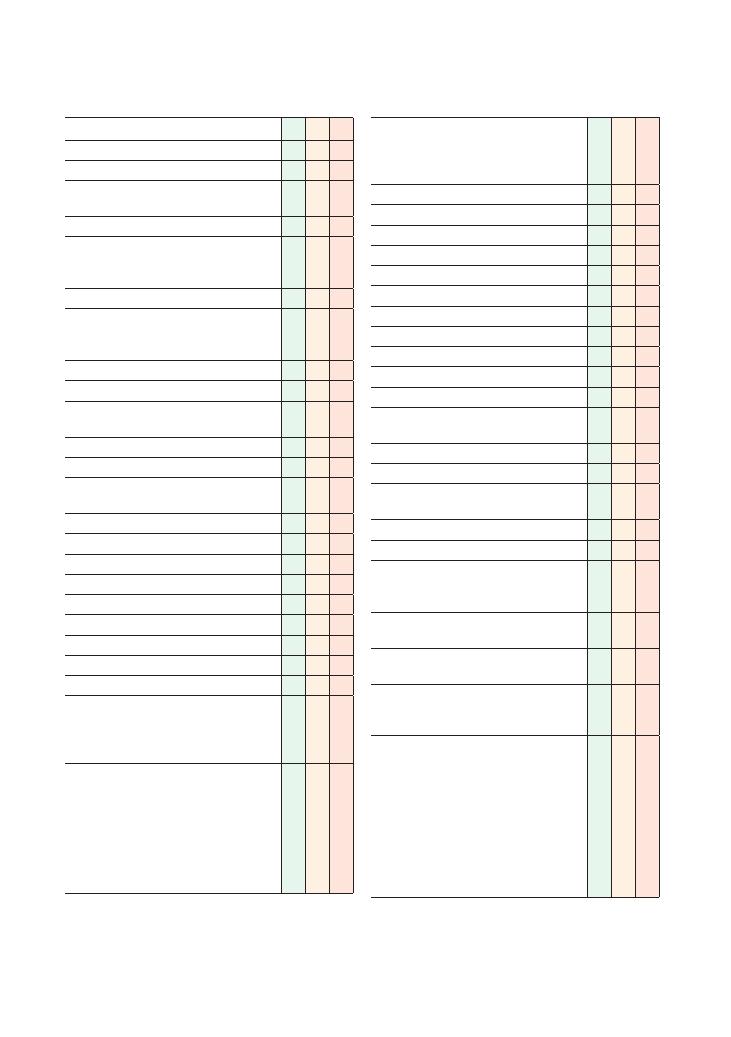

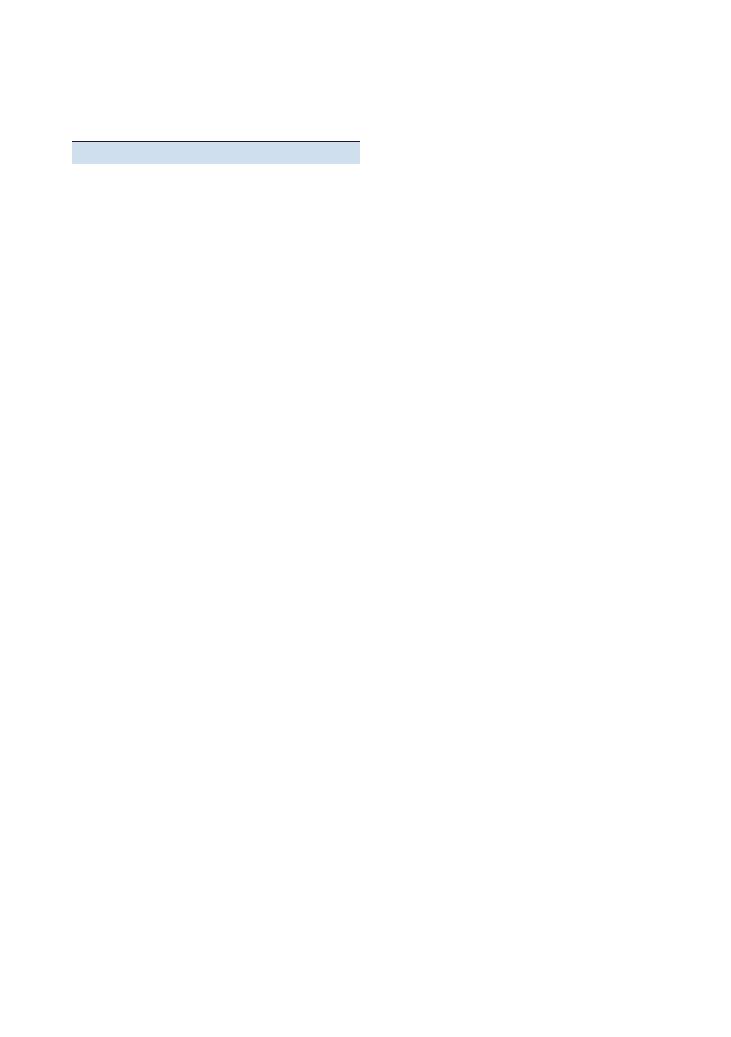

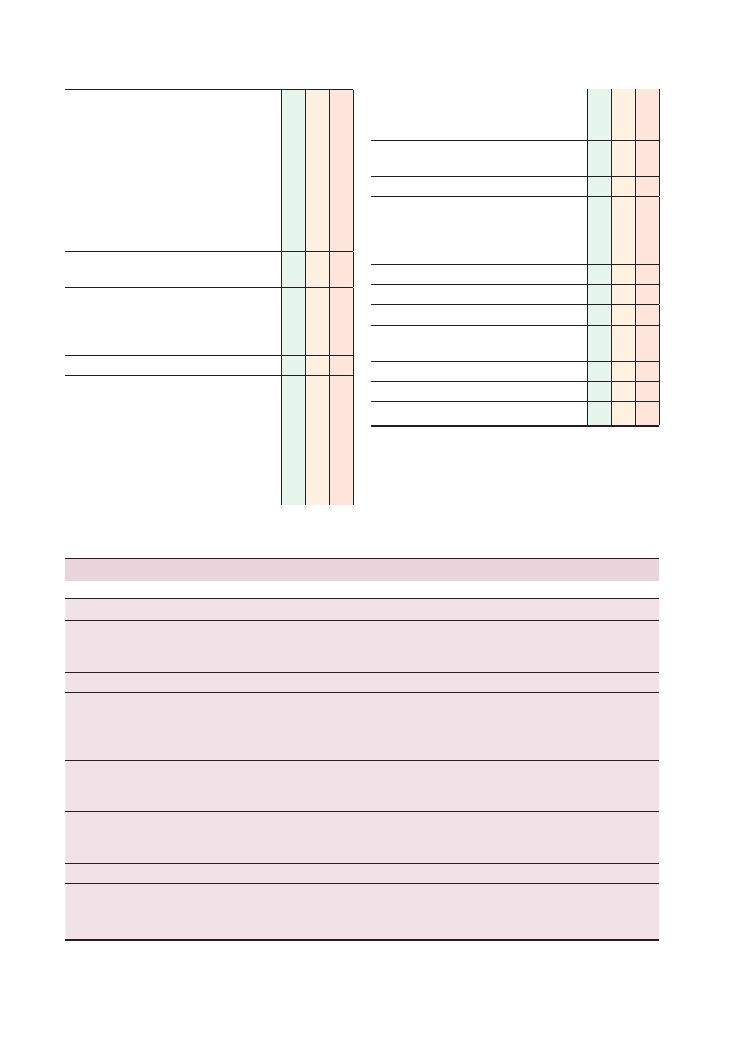

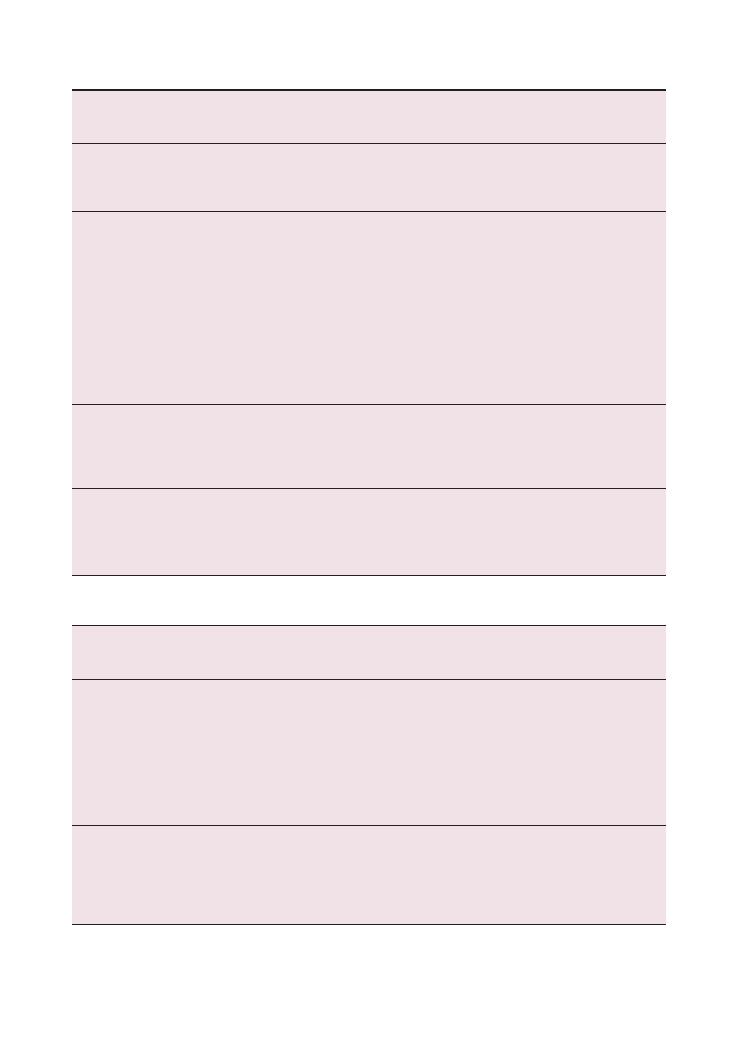

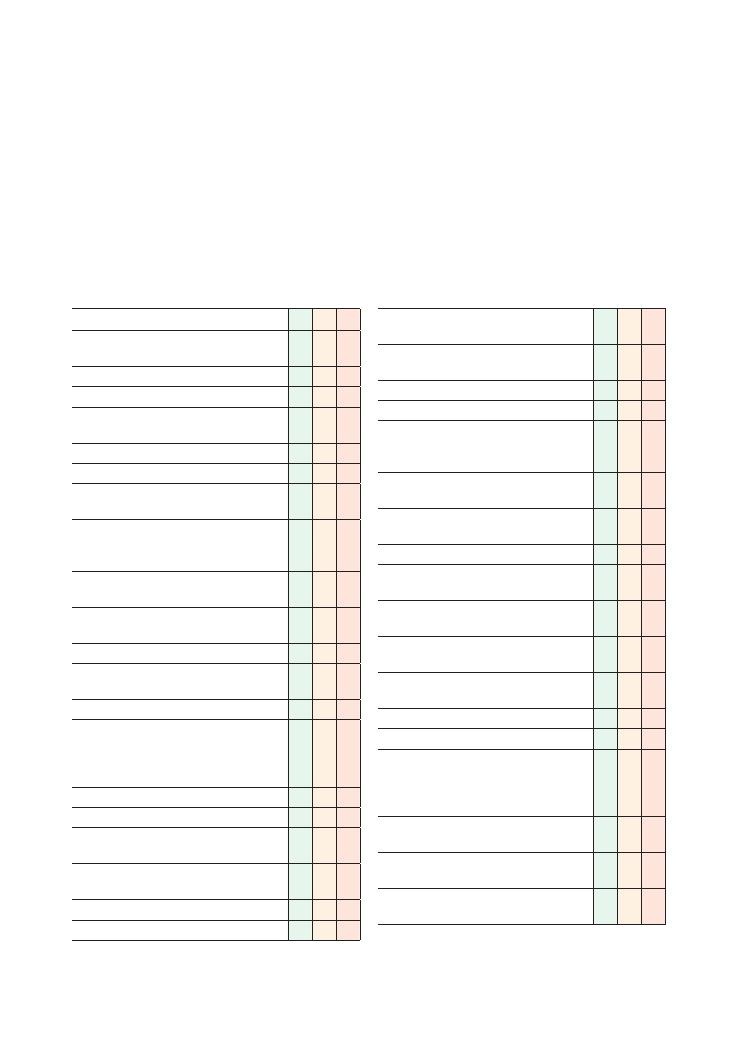

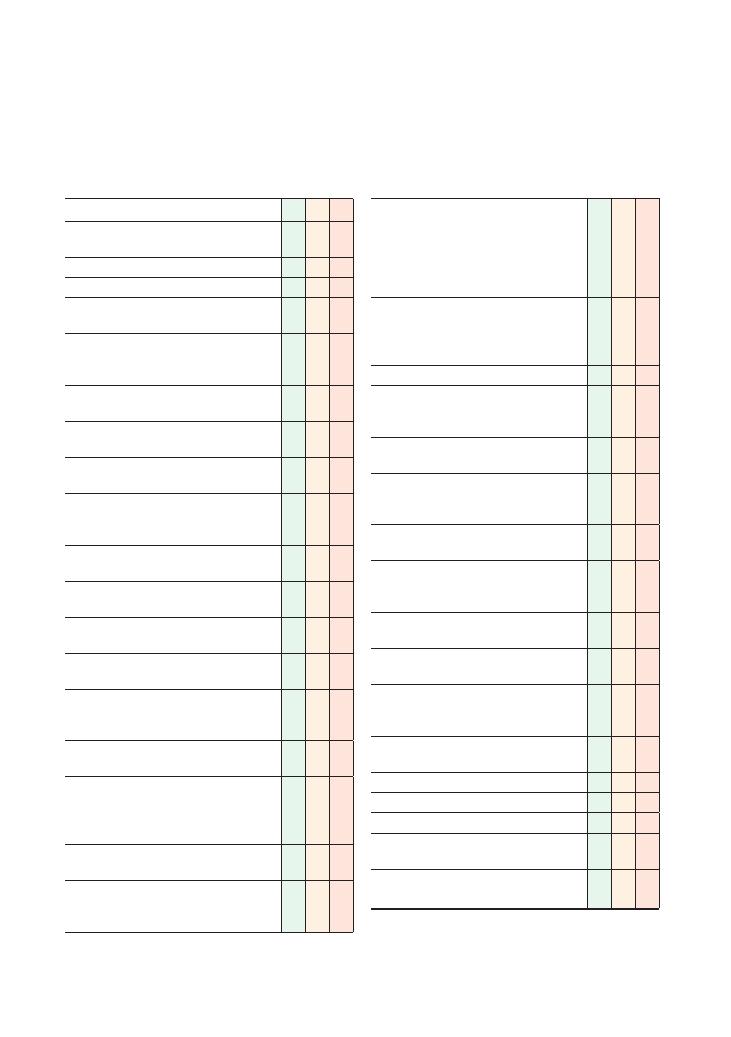

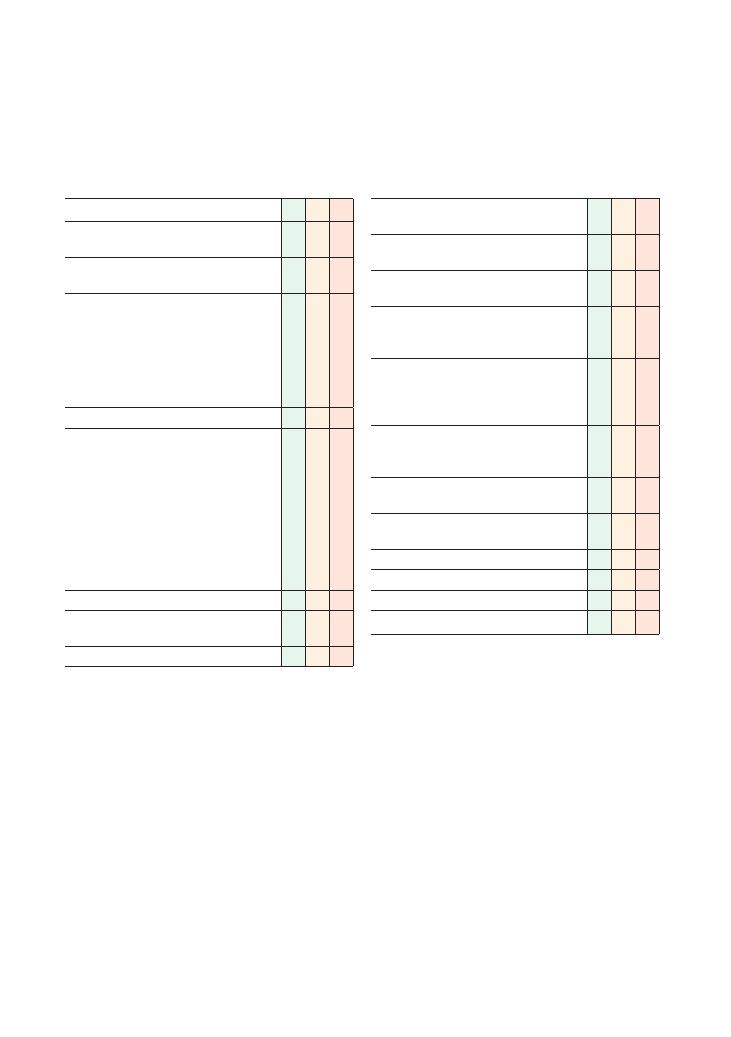

Checklist

P

MP

F

HELP:

H: ‘Hello’ (introduction and gains consent)

E: Exposure (nipples to knees/down to groins)

L: Lighting

P: Positions correctly (supine), asks if patient is in

any pain

Washes hands

Inspects from end of bed for relevant

paraphernalia (e.g. nutritional supplements, CAPD

device)

Inspects patient:

• Body habitus (BMI, Cushingoid from

immunosuppressants following organ

transplant)

• Pallor (anaemia)

• Jaundice

• Pigmentation (Addison’s disease, Peutz–Jeghers

syndrome, ‘bronze’/slate grey in

haemochromatosis, drugs)

• Bruising

• Tattoos

• Peripheral skin lesions associated with IBD

(erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum)

Hands:

• Clubbing (IBD, malignancy, malabsorption

states such as coeliac disease, liver cirrhosis)

• Dupuytren contracture

• Palmar erythema

• Leukonychia (iron deficiency)

• Koilonychia

• Liver flap

Arms:

• Arteriovenous fistula (for dialysis) – auscultate

for bruit

• Tattoos

Eyes:

• Jaundice

• Anaemia

• Xanthelasmata

Checklist

P

MP

F

Face:

• Parotid enlargement (alcohol excess)

Mouth:

• Angular stomatitis (iron/vitamin B deficiency)

• Glossitis (vitamin B deficiency)

• Peri-oral pigmentation (Peutz–Jeghers

syndrome), telangiectasia

• Ulcers (IBD)

• Dehydration

• Dental hygiene

• Smell of breath (hepatic fetor, uraemia)

Supraclavicular lymph nodes (Virchow’s node/

Troisier’s sign for stomach cancer)

Chest:

• Gynaecomastia

• Spider naevi (more than five is significant)

Inspects abdomen:

• Scars (see Figure 3.4)

• Drain insertion sites

• Peristalsis/pulsations

• Caput medusae

• Distension

• Masses/swellings

• Stretch marks/striae

Palpates abdomen (ideally kneeling down):

• Superficial palpation in nine quadrants for

masses and tenderness

• Deep palpation in nine quadrants for masses

and tenderness

• Hepatomegaly

• Splenomegaly

• Ballots kidneys

• Abdominal aortic aneurysm

Percusses abdomen:

• Liver

• Spleen

• Ascites with shifting dullness

• Bladder (dull if full, e.g. in urinary retention)

Auscultates for bowel sounds, renal bruits,

abdominal aortic aneurysm

Examines for shifting dullness/ascites

Examines lower legs for oedema

Examinations:

3 Abdominal 11

Checklist

P

MP

F

Tells examiner he would like to complete the

examination by examining the following:

• Hernial orifices (with cough/sitting up)

• Genitalia

• Rectum

• Lymph nodes

• Urine dipstick

Thanks patient

Offers to help patient get dressed

Checklist

P

MP

F

Washes hands

Presents findings

Offers appropriate differential diagnosis

Suggests appropriate further investigations and

management

OVERALL IMPRESSION:

Summary of common findings seen

in OSCEs

• Chronic liver disease

• Hepatomegaly

• Splenomegaly

• Nephrectomy scar/features of end-stage renal

failure (ESRF)

• Enlarged kidneys

• Transplanted kidneys

• Ascites

• Hernia

• Stoma

• Surgical scars

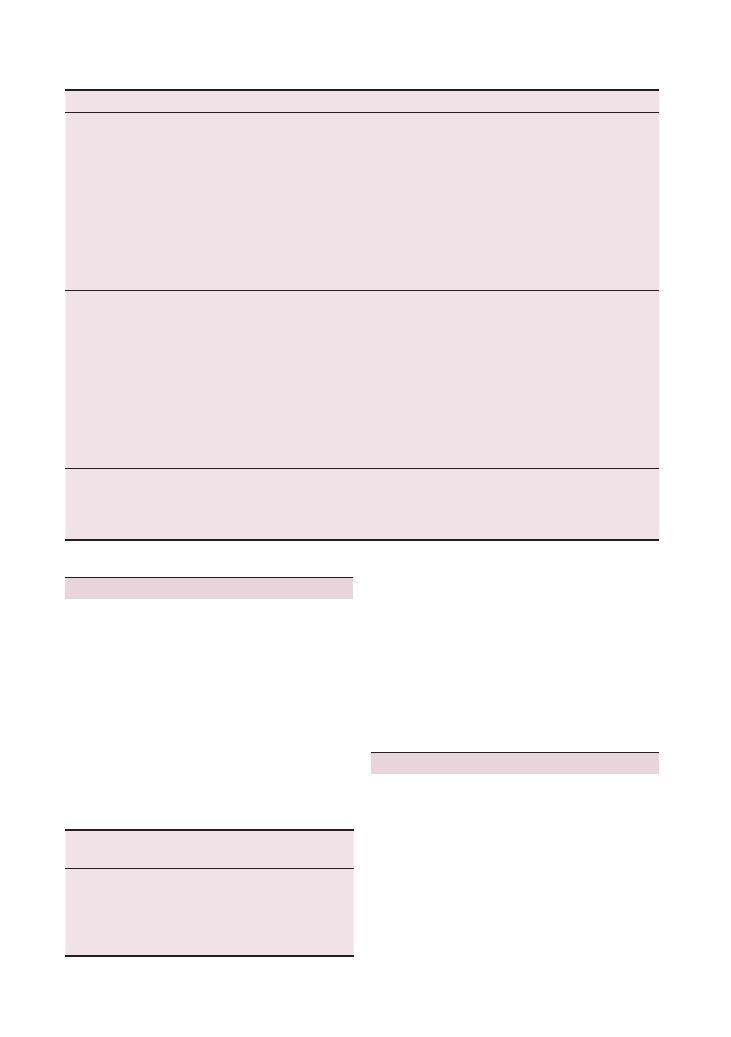

Summary of common conditions seen in OSCEs

Common chronic

conditions

Chronic liver disease

Inflammatory bowel

disease

Renal disease/ESRF

Examination findings

General inspection

Malnourished

Bruising (impaired clotting)

Cushingoid appearance

(from steroids)

Cushingoid appearance (from

steroids)

CAPD paraphernalia

Hands/arms

Clubbing

Palmar erythema

Dupuytren contracture

Liver flap (in hepatic encephalopathy)

Leukonychia (due to

hypoalbuminaemia)

Clubbing

Tubing for total parenteral

nutrition

Leukonychia/ koilonychia

Arteriovenous fistula (listen to

bruit)

Elevated blood pressure

Renal osteodystrophy

Face

Jaundiced sclera (if decompensated)

Parotid enlargement (if liver failure

caused by excess alcohol intake)

Mouth ulcers

Temporalis muscle wasting

Gum hypertrophy (ciclosporin)

Anaemia

Collapsed nasal bridge

(Wegener’s granulomatosis)

Molluscum (immunosuppression)

Viral skin warts/skin cancers

Butterfly rash (if SLE)

Hearing aid (if Alport syndrome)

Neck

Raised JVP (if fluid overload

secondary to hypoalbuminaemia)

Parathyroidectomy scar (after

tertiary hyperparathyroidism)

Raised JVP

Cushingoid neck

(

Continued )

12

Examinations:

3 Abdominal

Common chronic

conditions

Chronic liver disease

Inflammatory bowel

disease

Renal disease/ESRF

Chest

Reduced hair

Gynaecomastia

Spider naevi

Right internal jugular/subclavian

tunnelled intravenous line/scar

CABG scar (may indicate

atherosclerosis causing

renovascular disease)

Abdomen

Jaundice (if decompensated)

Ascites (if portal hypertension)

Hepatomegaly

Splenomegaly (in portal hypertension)

Caput medusae

Surgical scars

Liver transplant scar (from

primary sclerosing

cholangitis)

Fistulas

Stomas

Nephrectomy scars (if renal

transplant/dialysis)

Enlarged kidneys (if adult

polycystic kidney disease)

Transplanted kidney palpable in

iliac fossa/near groin

CAPD scars

Injection sites (from

subcutaneous insulin)

Cushingoid features (if

immunosuppression with

steroids)

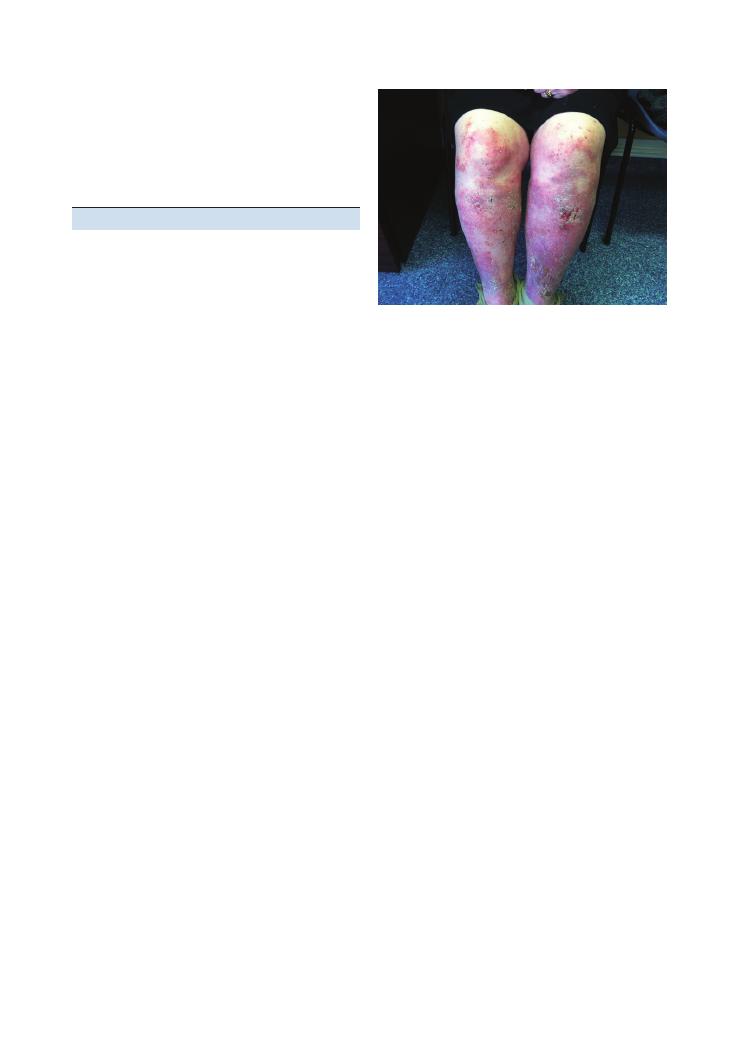

Legs

Peripheral oedema

(hypoalbuminaemia)

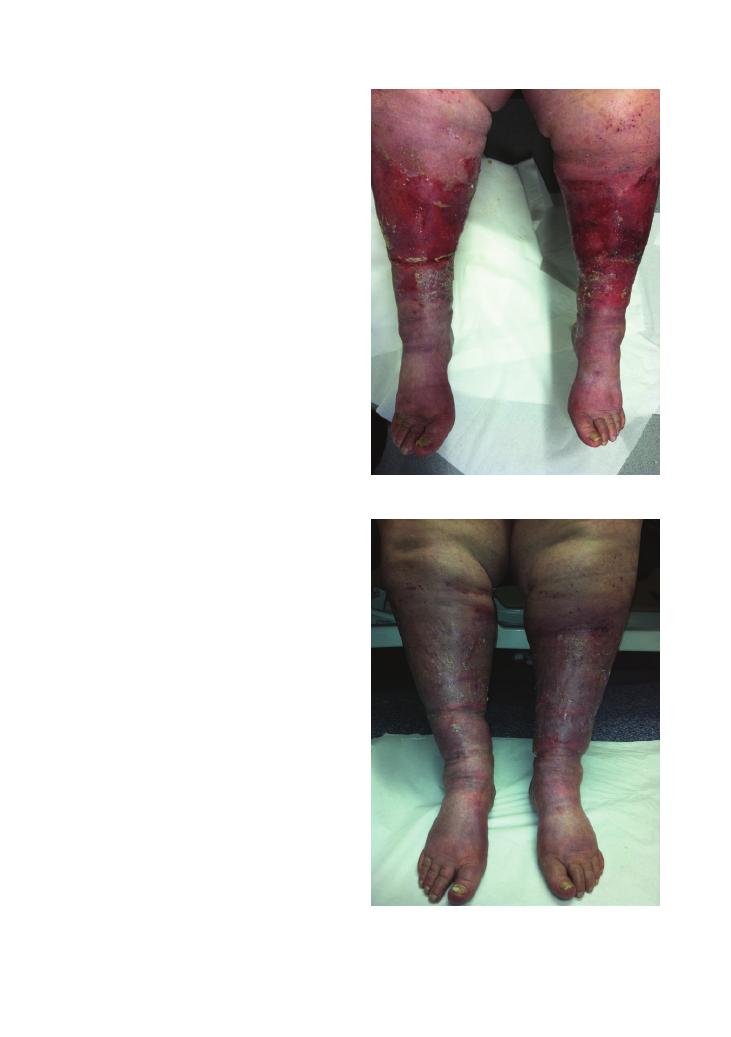

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Erythema nodosum

Peripheral oedema

Key investigations

Liver function tests

Clotting and albumin (for synthetic

liver function)

Alcohol screen

Abdominal ultrasound

Viral hepatitis screen

Autoimmune hepatitis screen

Viral serology screen

Liver biopsy

Oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy

(to look for varices if portal

hypertension suspected)

Inflammatory markers

Colonoscopy

Stool microscopy, culture

and sensitivity

Urinalysis (including albumin

creatinine ratio)

Us

+Es and glomerular filtration

rate

Nephritic/vasculitic screen

Renal ultrasound

IVU/CT kidneys, ureter and

bladder

Renal biopsy

Key management

principles

Treat underlying cause

Stop all hepatotoxic medications

Nutritional support

Salt restriction

Monitor fluid status and input/output

Vitamin B/folate supplements

Lactulose

Monitor blood glucose

Monitor Glasgow Coma Scale score

Treat clotting abnormalities

Assess for portal hypertension

(splenomegaly/ascites/caput

medusae)

→ if present do

oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy

for varices

Steroids (topical/enema/

oral)

Mesalazine/ azathioprine/

anti-TNF

Assess for toxic

megacolon

Monitor inflammatory

markers

Metronidazole for perianal

disease

Nutritional support/

elemental diet

Surgery

Treat underlying cause

Stop all nephrotoxic medications

Nutritional support

Salt restriction

Monitor fluid status and input/

output

Calcium supplements (if

hypocalcaemic)

Phosphate binders (if high

phosphate)

Monitor parathyroid hormone

level (consider

parathyroidectomy if tertiary

hyperparathyroidism)

Monitor blood gases and treat

acidosis

Monitor Hb (consider

erythropoietin/iron if anaemic)

Optimise blood pressure (ACE

inhibitor) and cholesterol

Examinations:

3 Abdominal 13

Hints and tips for the exam

Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly

Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly are also very common

findings at this station in finals. We have discussed

various key tips below to help you in both the diagnosis

and the discussion.

Examining large livers and spleens

• Start low in the right iliac fossa, so that you do not

miss giant organomegaly.

Common conditions leading to chronic

liver disease

To make things easier, we have summarised here the key

clinical features and investigations of chronic liver

disease that you can use in the viva/questions part at

the end of the OSCE generically, regardless of what the

cause of the liver disease is. Table 3.1 outlines common

conditions leading to chronic liver disease – the most

common ones are marked with an asterisk. This will be

especially useful for students aiming for a merit or dis-

tinction, as it helps to diagnose not only chronic liver

disease, but also the underlying cause.

Table 3.1 Common conditions leading to chronic liver disease

Common causes of

chronic liver disease

Key points in history

Collateral ‘clues’

Specific investigations to

identify cause

*Alcohol

Alcohol intake

CAGE

Rib fractures on chest X-ray

High AST:ALT ratio

High MCV

*Hepatitis B and C

Sexual history

Intravenous drug abuse

Blood transfusions

Travel abroad

Tattoos

Scars from intravenous access

Hepatitis serology

Primary biliary cirrhosis

Xanthelasmata

Pigmentation

Clubbing

Excoriation marks

Female (

>90%)

Middle-aged

Features of autoimmune/connective

tissue/rheumatological diseases

Features of immunosuppression (Cushing’s

disease, molluscum contagiosum)

↑ IgM

Antimitochondrial antibodies

Cholestatic liver profile (

↑ ALP)

Liver biopsy

Autoimmune hepatitis

Musculoskeletal pain

Features of autoimmune/connective

tissue/rheumatological diseases

Features of immunosuppression (Cushing’s

disease, molluscum)

↑ IgG

Antinuclear antibodies

Anti-smooth muscle antibodies

Liver biopsy

Primary sclerosing

cholangitis

Past medical history of or active

IBD

Features of IBD (usually ulcerative colitis)

Bowel surgery scars

Stoma

pANCA

ERCP/MRCP

Liver biopsy

Cholestatic liver profile (

↑ ALP)

Wilson’s disease

Family history (autosomal

recessive inheritance)

‘Bronze’ skin pigmentation

Marked tremor

Kayser–Fleischer rings in iris

Dysarthria/cognitive impairment

Serum copper

24-hour urinary copper excretion

Haemochromatosis

Family history (autosomal

recessive inheritance)

Diabetes

Arthritis

Hypopituitarism

‘Slate grey’ pigmentation

‘Bronzing’ of the skin

Gonadal atrophy

Gynaecomastia

Serum iron studies

Liver biopsy

Fatty liver/non-alcoholic

steatohepatitis)

Xanthelasmata

Hypertension

CABG scar

Ultrasound

Lipids

Heart failure

Past medical history of heart

disease/hypercholesterolaemia

Signs of heart failure

Echo

14

Examinations:

3 Abdominal

• Use the radial aspect of your index finger – but if that

doesn’t work, use your finger with your hands pointing

up towards the patient’s head.

• Keep your fingers absolutely still as the patient

breathes in and out.

• Make sure that you move your hand upwards supe-

riorly by no more than 2 cm as the patient breathes in

and out. If you leave too large a distance as you move

up, there is a risk that you may miss the edge of the liver

or spleen.

• For the liver, percussion is almost as discriminatory

as palpation. It is also useful to differentiate between

lung hyperinflation pushing the liver down, and true

hepatomegaly. The superior aspect of the liver usually

lies between the 4th and 6th ribs, and continues down

to the last rib at the inferior border of the rib cage;

hence, there should be dullness in all of this area.

Hyperinflation pushing down the liver is confirmed if

percussion is resonant significantly below the 6th rib.

• For the spleen, use your left hand to stabilise the left

ribs in order to prevent them from being pushed

towards the left as you palpate the spleen with your

right hand. If you still have difficulty, roll the patient

on to the right side and repeat this.

• When you do find an enlarged liver or spleen, esti-

mate the size of hepatomegaly in centimeters rather

than ‘finger breadths’, which vary from person to person

(depending on how big their fingers are!).

• Avoid the business of trying to identify the liver char-

acteristics (e.g. whether it ‘firm’, ‘hard’ or ‘soft’, or pul-

satile, or nodular or smooth). Doing this in an exam

will make the patient uncomfortable and use up your

valuable time without achieving very much. Once a

large liver or spleen has been identified, the most logical

way of defining its characteristics would be to carry out

some sort of imaging – usually an ultrasound of the

abdomen.

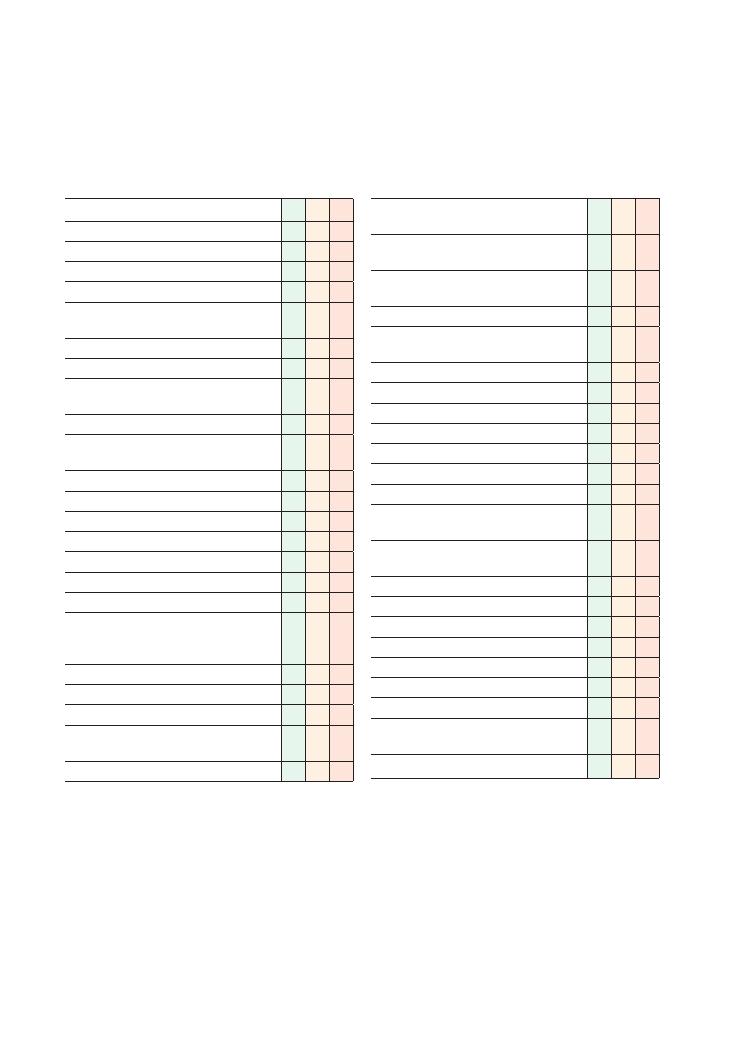

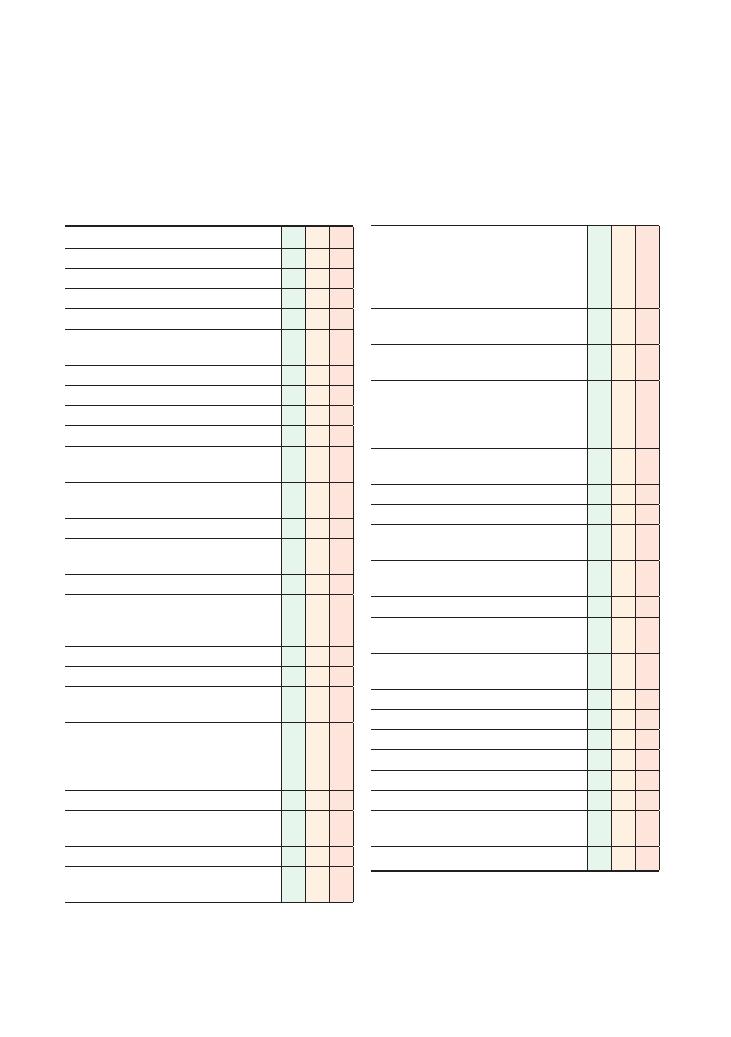

Systematic differentiation of the underlying

causes of hepatomegaly and splenomegaly

• A large liver and/or spleen is a very common finding

at finals OSCE stations. Make sure that you have a

generic system for categorising the causes, so that you

can reel off a list of differential diagnoses quickly, con-

fidently and systematically.

• Always try to use all the signs to help you devise a

differential diagnosis. However, if you find an enlarged

spleen or liver and have no clue what the cause is,

go for conditions that can cause hepatomegaly and

splenomegaly either individually or together – the first

column of Table 3.2 summarises these.

• Don’t be too pedantic when distinguishing between

gigantic, moderate and mild splenomegaly. Identifying

splenomegaly and giving a reasonable list of differential

diagnoses and investigations will usually be enough

to score a decent pass. Distinguishing between mild/

moderate and gigantic splenomegaly will help to get

you into the merit/distinction range. Remember that

the spleen has to be at least double or triple its normal

size to be palpable.

• Remember to piece the other parts of your examina-

tion together to complete the diagnostic jigsaw. All the

conditions that cause hepatomegaly or splenomegaly

have several peripheral signs so look out for these and

use them to support your differential diagnosis.

Renal cases

Although students often worry about getting a ‘renal

case’ in finals, it can often be a blessing in disguise. The

differential diagnosis is relatively straightforward, and

the signs are easy to elicit.

Fundamentally, there are only two findings in renal

cases – those of ESRF, and ballotable enlarged kidneys.

End-stage renal failure

There are potentially three findings that are all attribut-

able to ESRF:

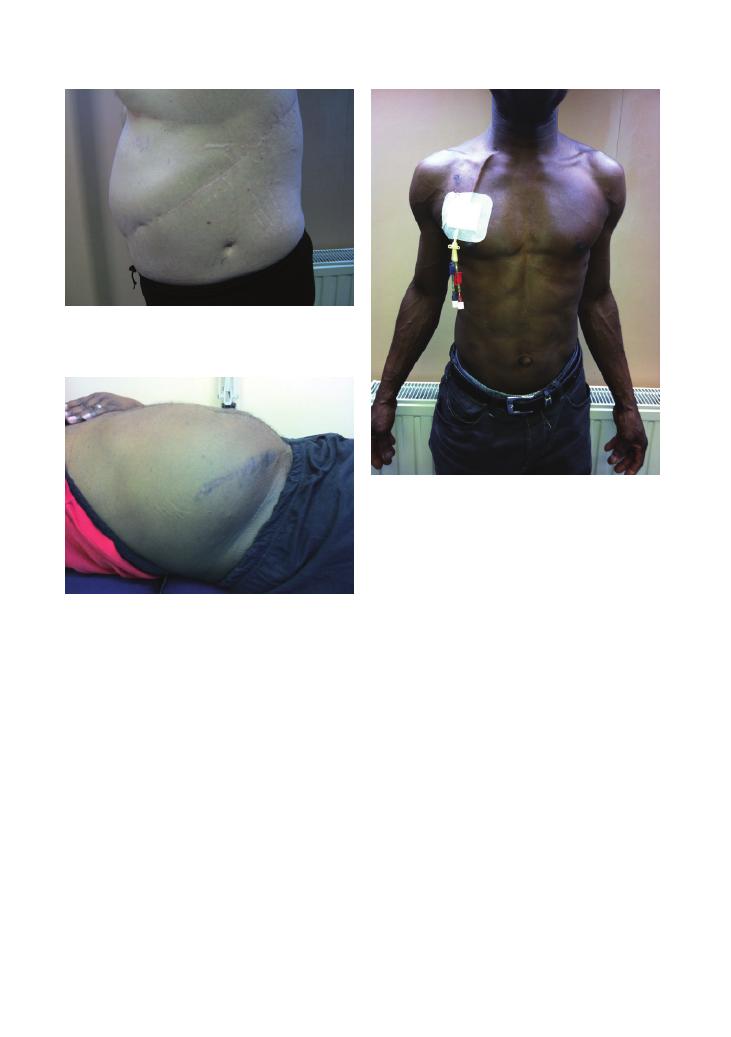

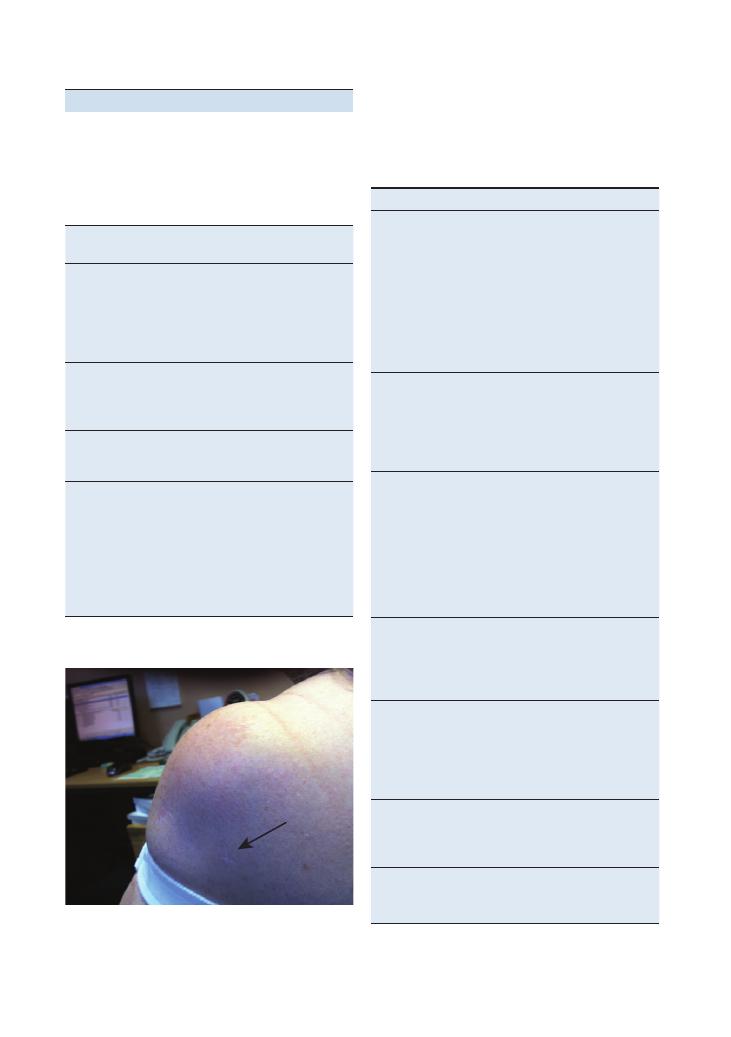

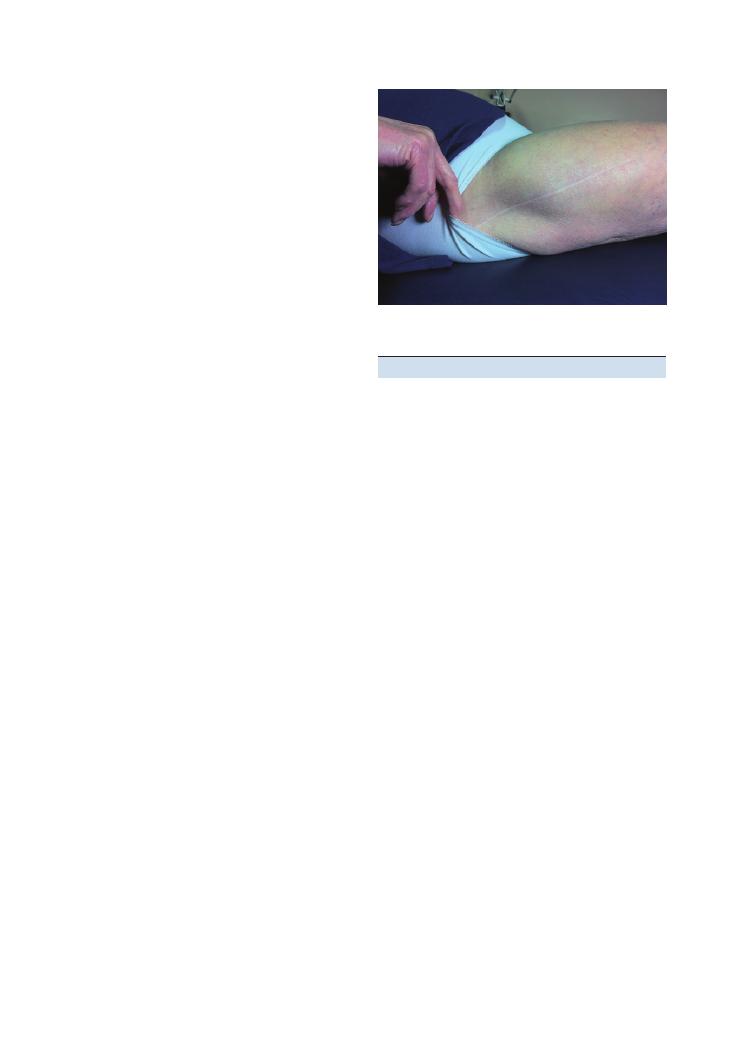

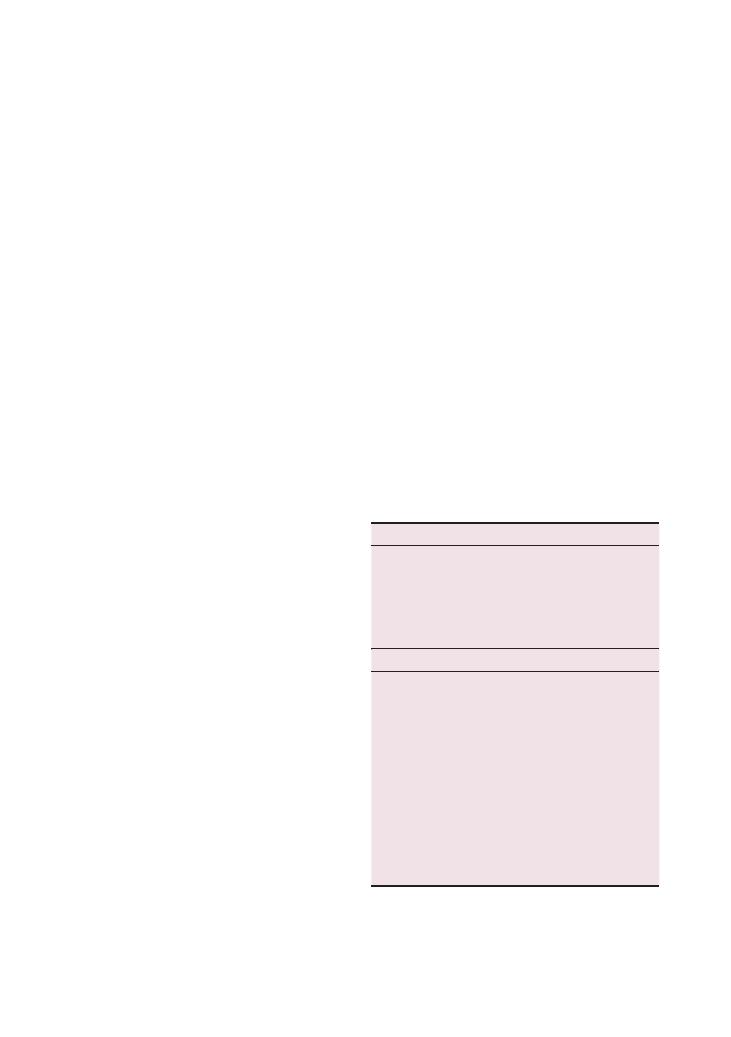

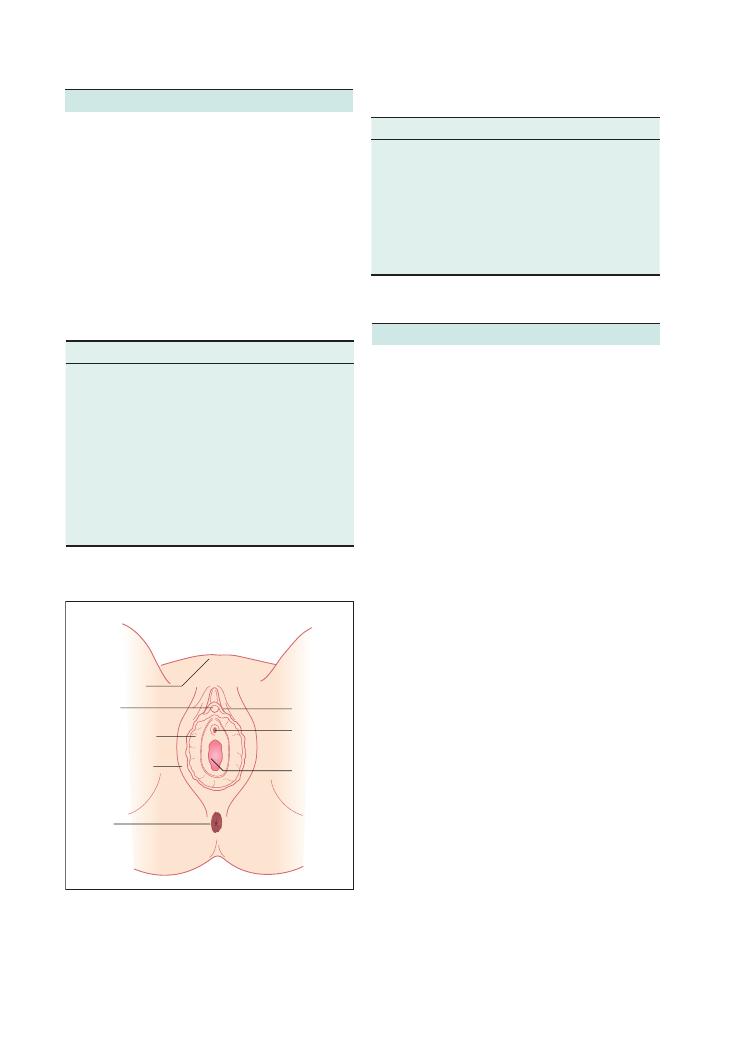

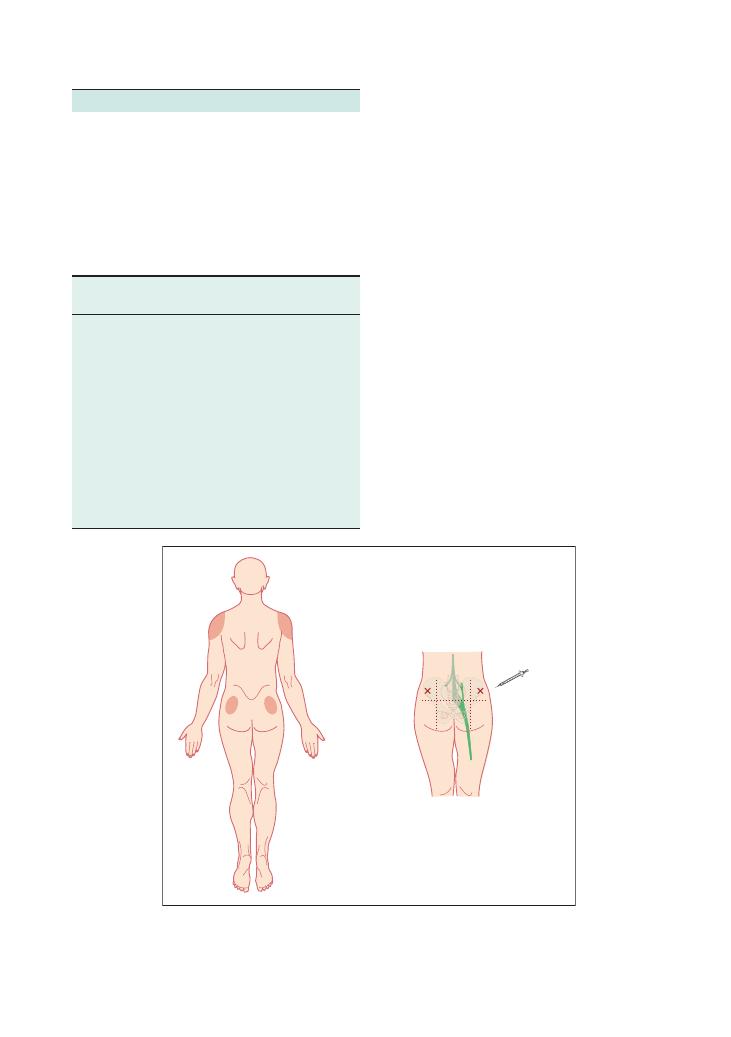

• Nephrectomy scar (Figure 3.2): Inspect carefully for

this, making sure that you look all the way around the

lumbar/flank regions through to the back. Finding a

nephrectomy scar is alone sufficient to devise a full list

of differential diagnoses and a management plan.

• Palpable transplanted kidney: This is usually near

the groin/iliac fossa with a small scar at the site.

• Signs of dialysis use (arteriovenous fistula, right

internal jugular vein line, CAPD scars; Figure 3.3): A

slicker way of describing this is ‘renal replacement

therapy’, which covers them all – and also sounds more

impressive!

Whichever of these signs the patient has, the under-

lying condition is always ESRF.

The four most common causes of ESRF are as

follows:

1) Diabetes

2) Hypertension

3) Adult polycystic kidney disease (APKD)

4) Glomerulonephritis

Once you have got to this stage, your investigations and

management should be guided by your differential

diagnosis. However, if you are still struggling, merely

discuss the generic investigations and management

strategies for patients with ESRF, as discussed in the

summary table above.

Examinations:

3 Abdominal 15

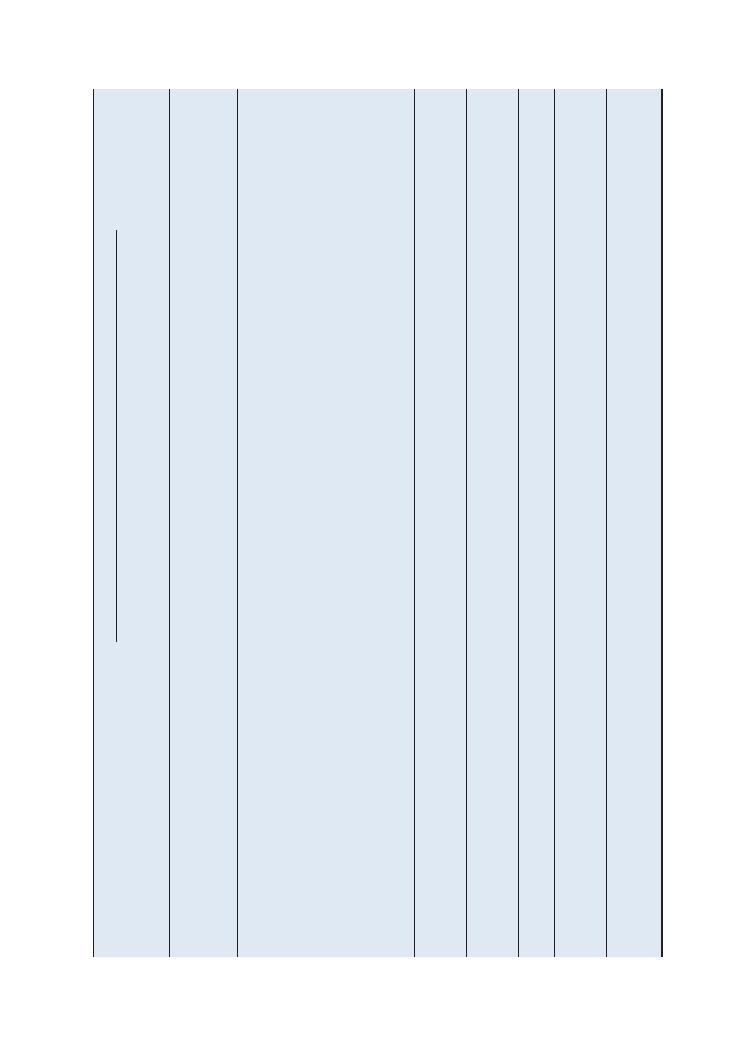

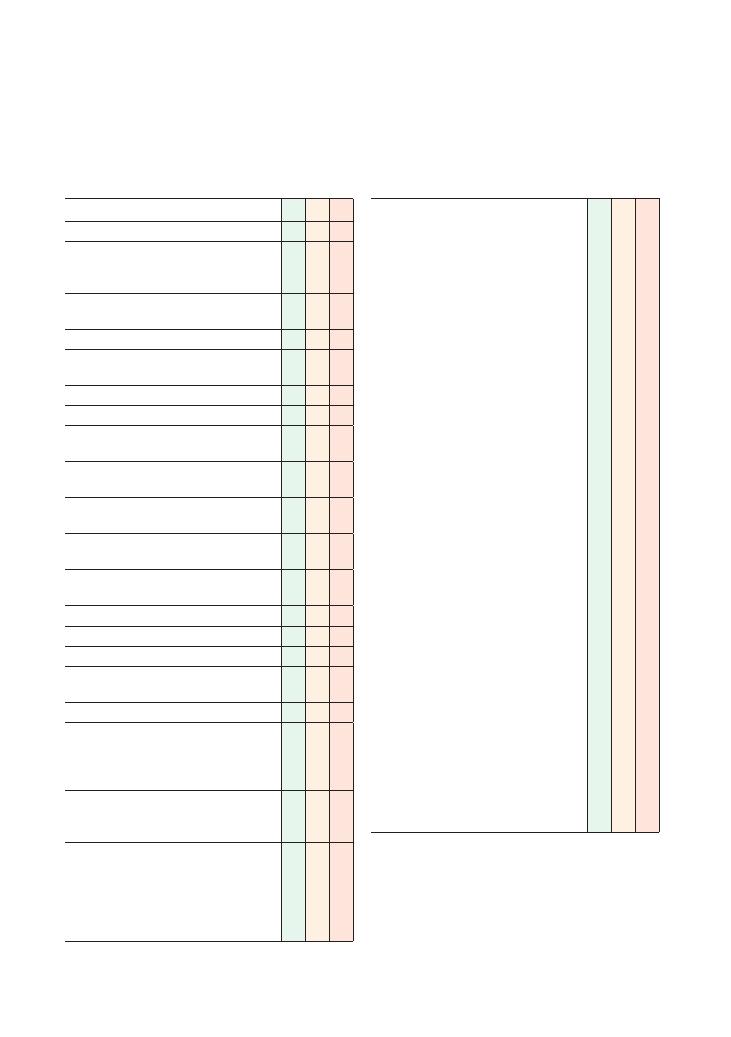

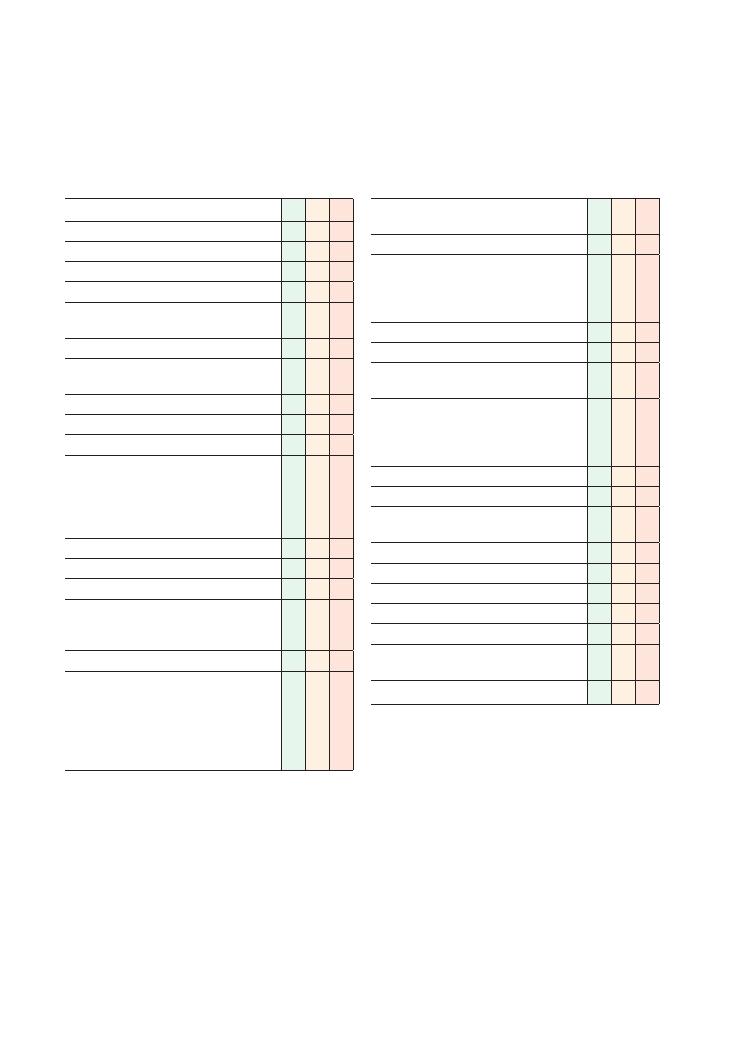

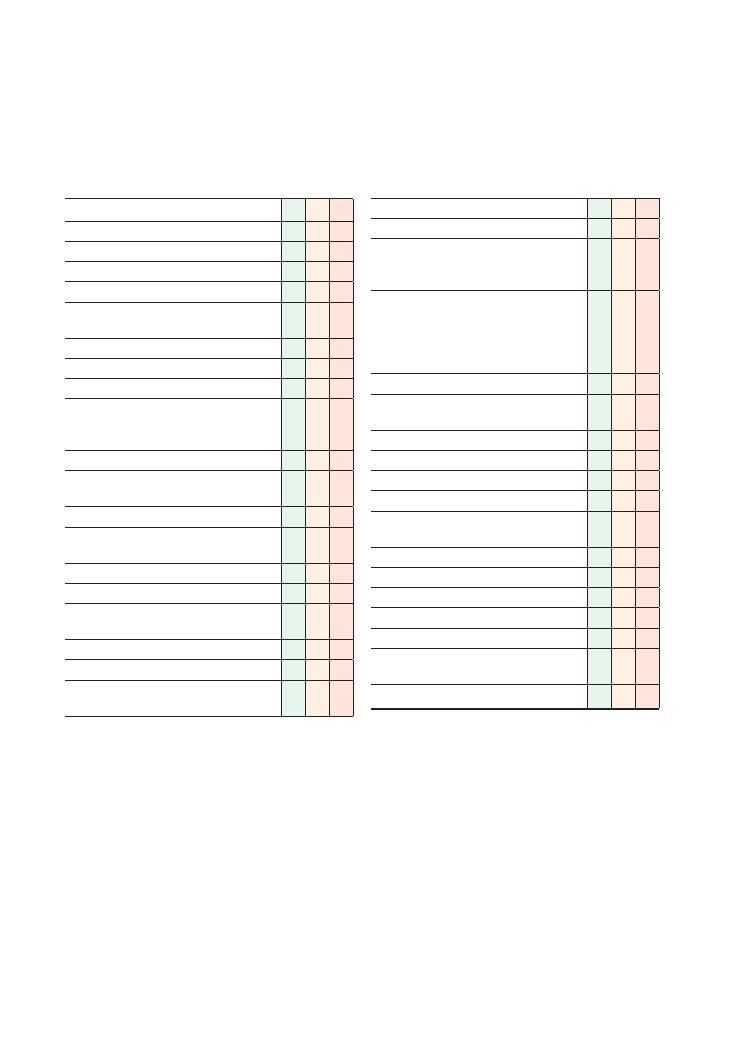

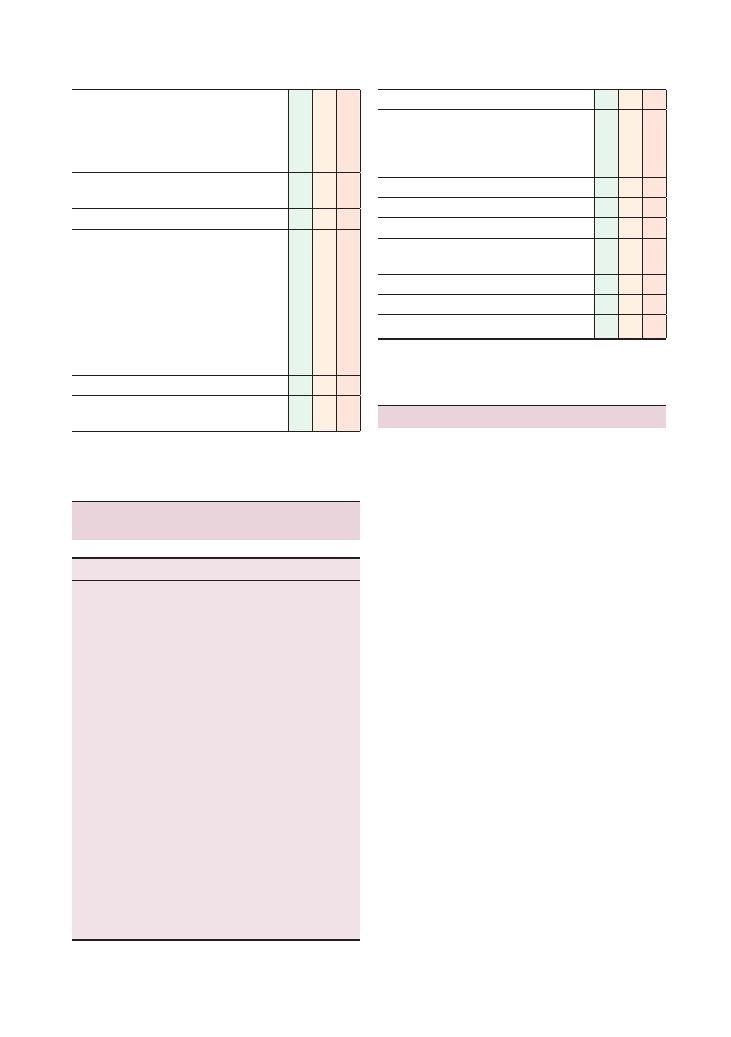

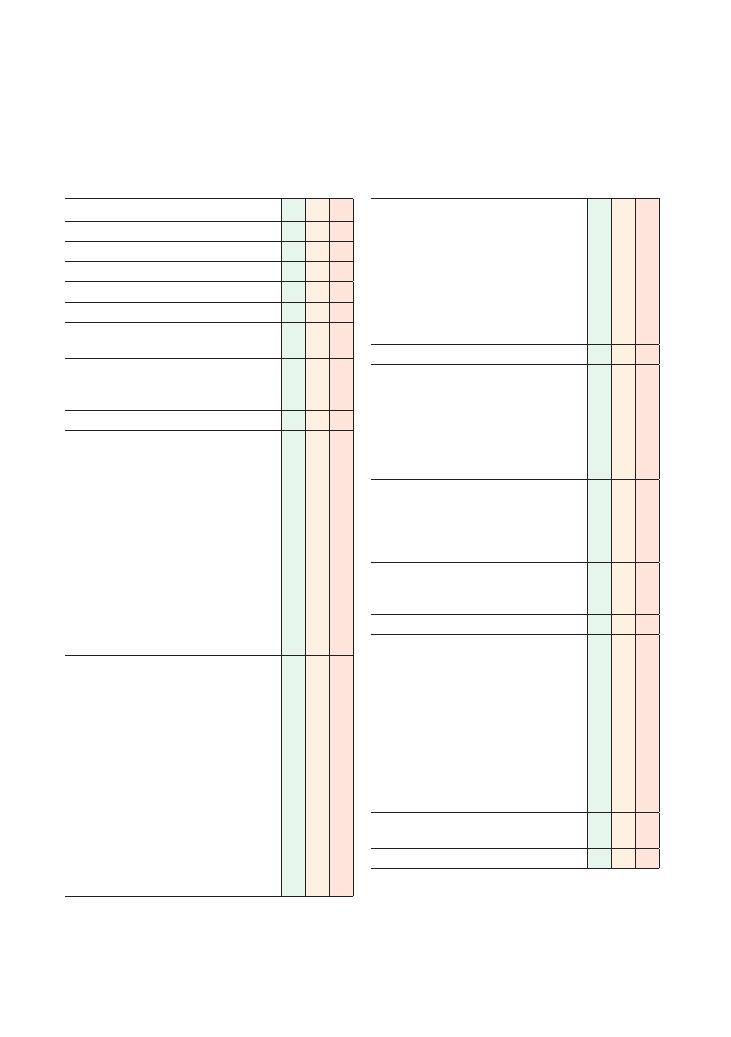

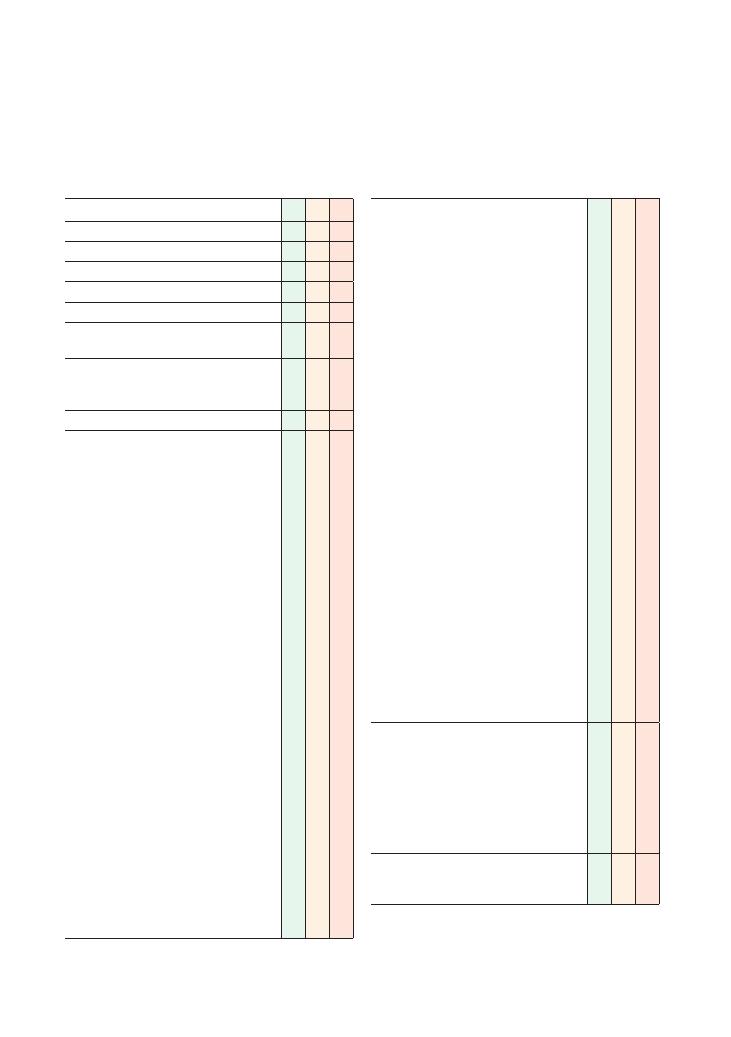

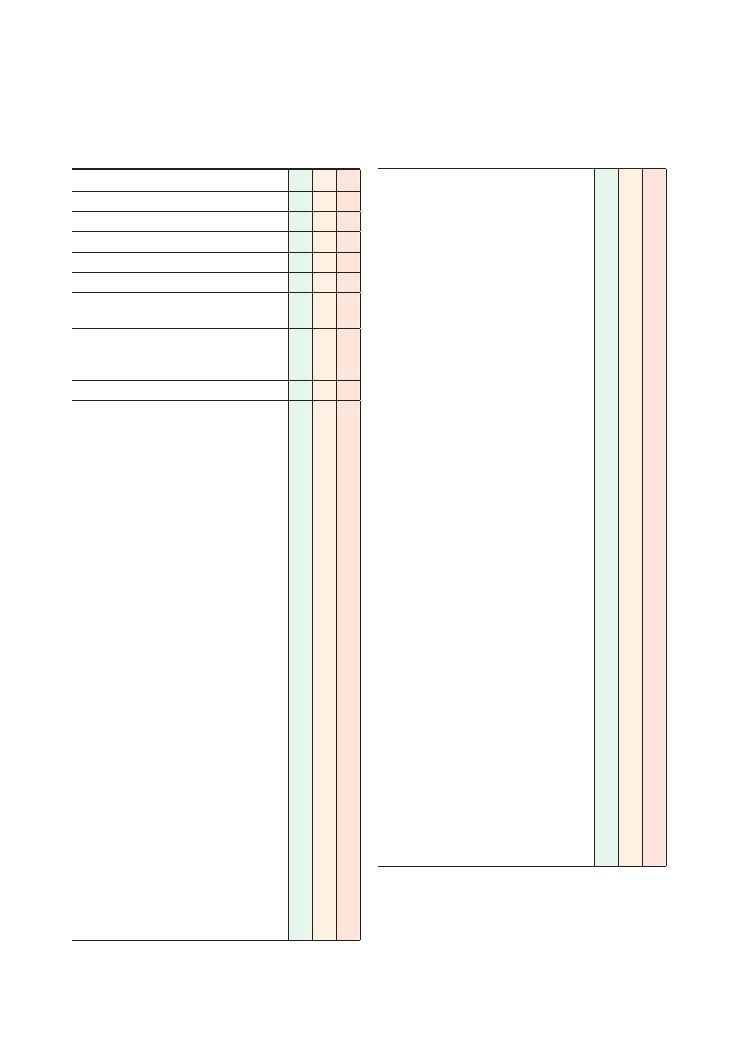

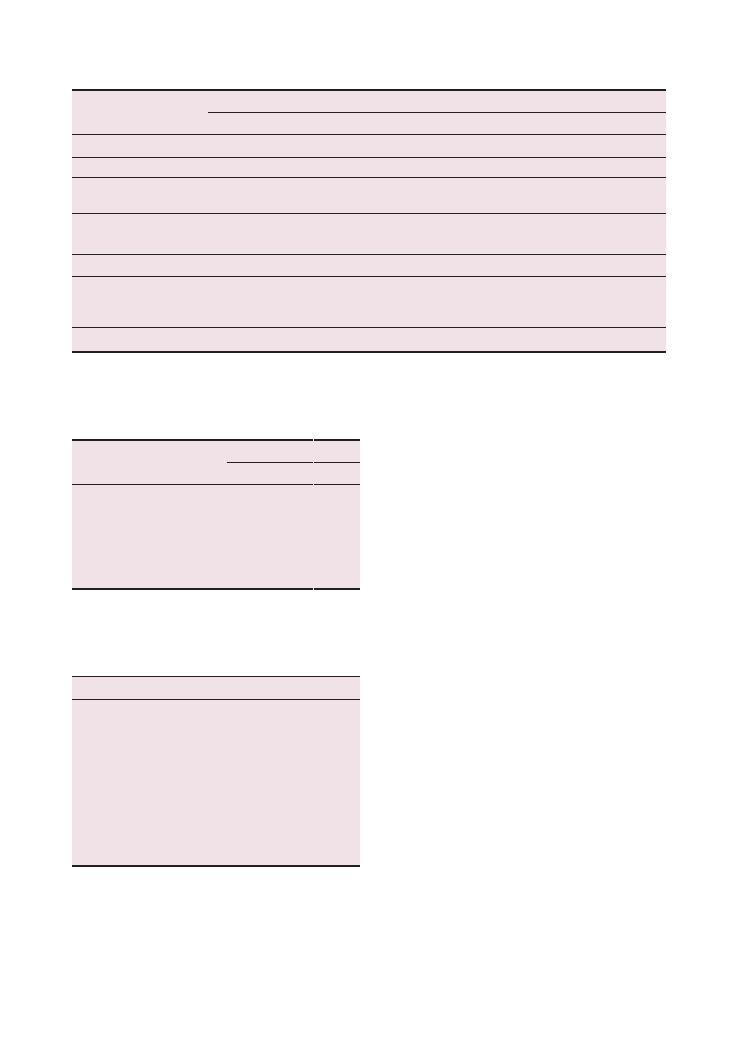

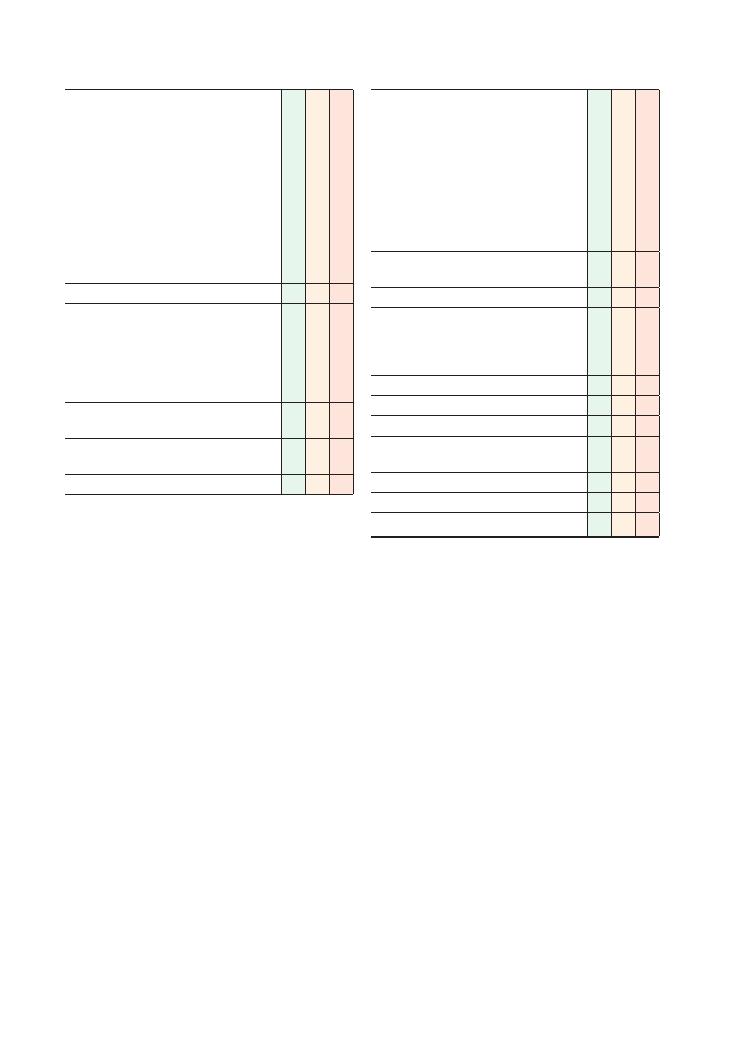

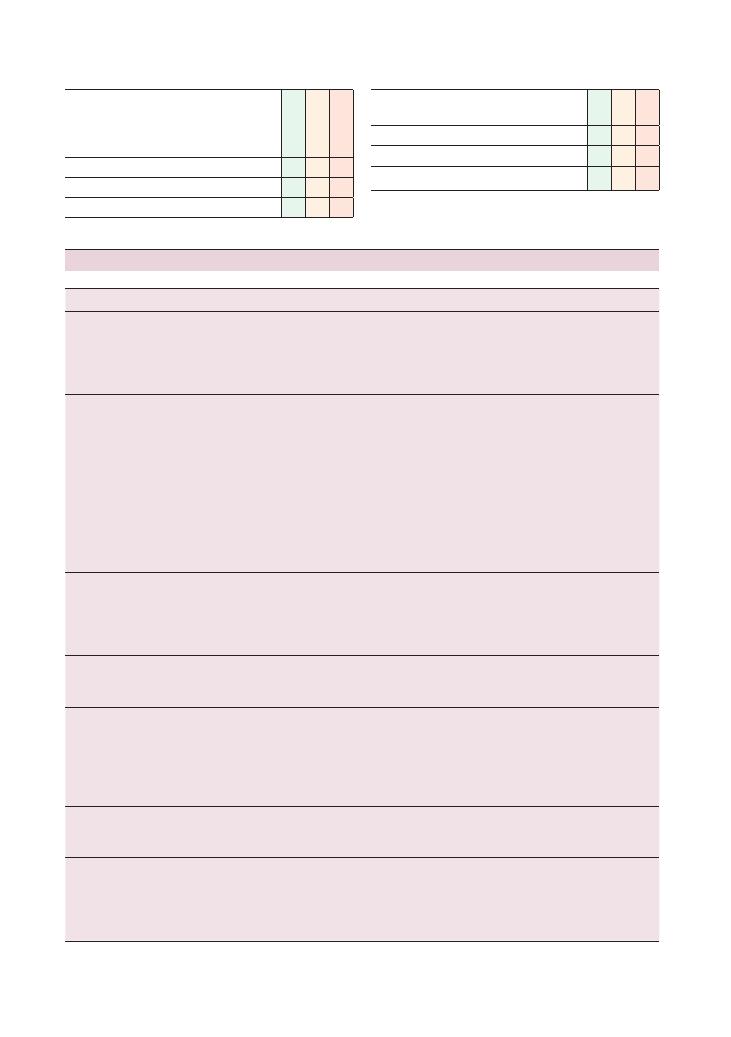

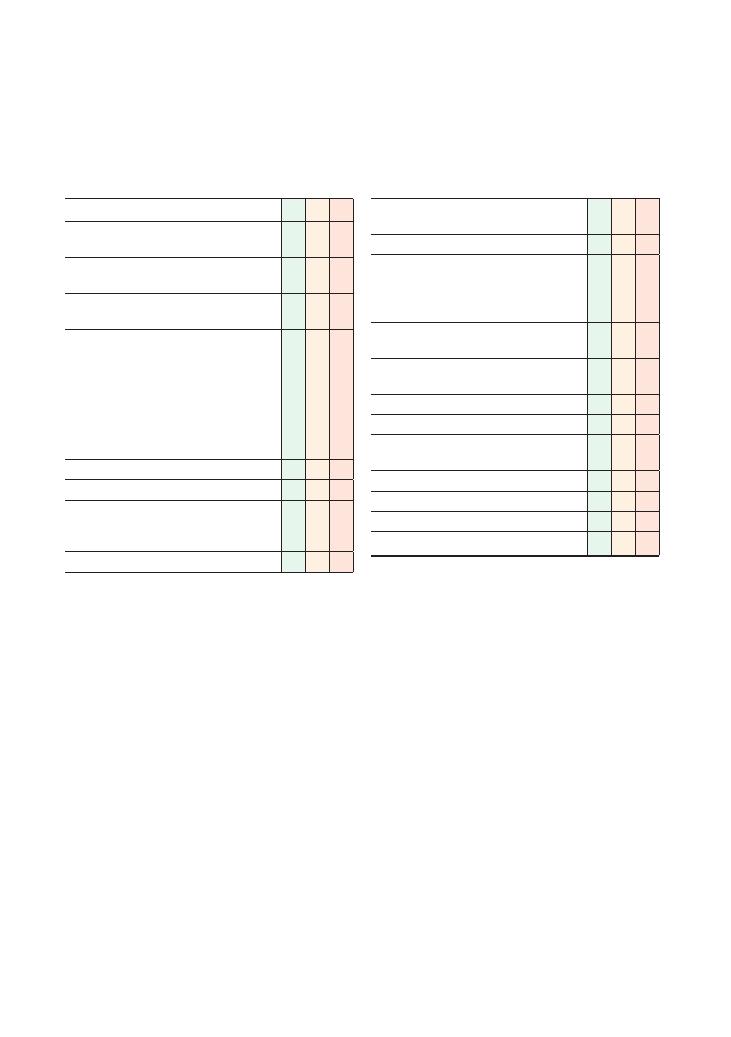

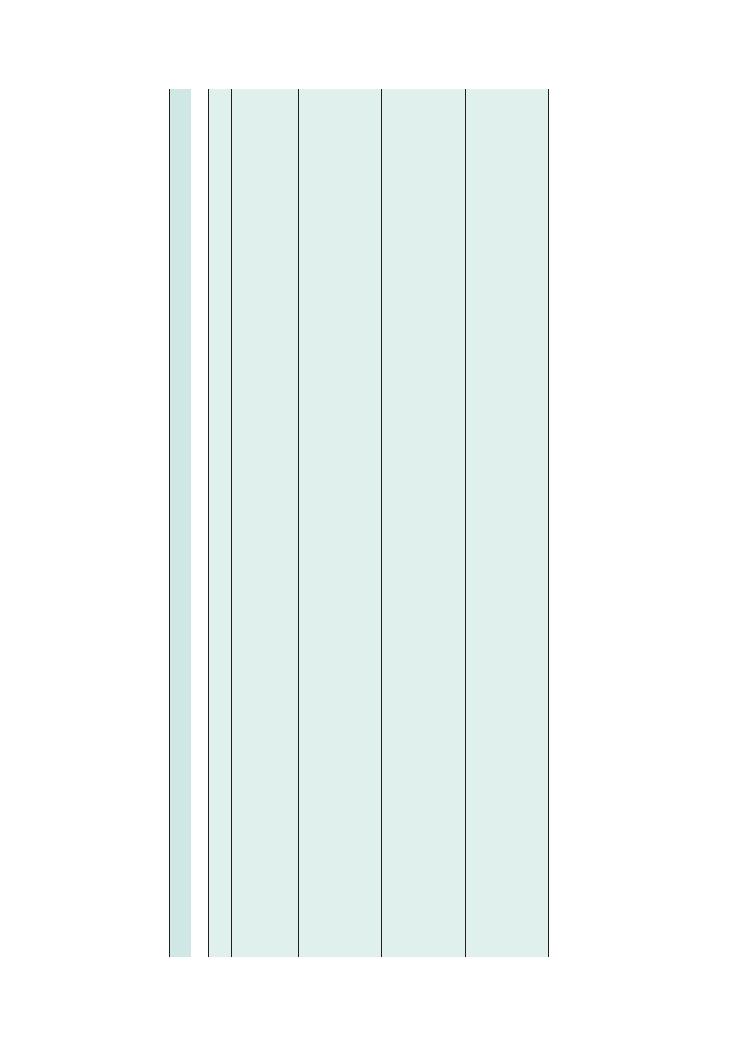

Table

3.2

Causes

of

hepatomegaly

and

splenomegaly

Hepatosplenomegaly

Hepatomegaly

only

(without

splenomegaly)

Splenomegaly

only

(without

hepatomegaly)

Peripher

al

signs

Gigantic

splenomegaly

(palpable

in

right

lower

quadr

ant)

Moder

ate

splenomegaly

(5–10

cm)

Mild

splenomegaly

(2–5

cm)

Malignancy

All

haematological

malignancies

(myeloprolifer

ative

and

lymphoprolifer

ative)

Hepatocellular

carcinoma

Secondary

metastases

Chronic

myelogenous

leukaemia

Myelofibrosis

All

haematological

malignancies

(myeloprolifer

ative

and

lymphoprolifer

ative)

All

haematological

malignancies

(myeloprolifer

ative

and

lymphoprolifer

ative)

Lymphadenopathy

Cachexia

Anaemia

Bruising

and

purpur

a

Infective

Vir

al

hepatitis

CMV

To

xoplasmosis

Malaria

Schistosomiasis

Histoplasmosis

Brucellosis

Leptospirosis

Kala-azar

W

eils

disease

Hydatid

disease

Vir

al

hepatitis

Chronic

malaria

Viscer

al

leishmaniasis

All

infectious

causes

of

hepatosplenomegaly

Glandular

fever

Brucellosis

Vir

al

hepatitis

Early

sickle

cell

disease

HIV

Pyrexia

Recent

foreign

travel

Tattoos/intr

avenous

drug

abuse

scars

(vir

al

hepatitis)

Infiltr

ative

Sarcoidosis

Amyloidosis

Gaucher’

s

disease

Fatty

liver/NASH

Haemochromatosis

Gaucher’

s

disease

Gaucher’

s

disease

Sarcoidosis

Amyloidosis

Gaucher’

s

disease

Sarcoid

skin

disease

Inflammatory

–

–

–

Felty’

s

syndrome

(rheumatoid

arthritis

, neutropenia,

splenomegaly)

Rheumatoid

arthritis

SLE

Arthropathy

Butterfly

rash

of

SLE

Liver

disease

Liver

disease

with

portal

hypertension

Any

cause

of

chronic

liver

disease

(as

above)

–

Portal

hypertension

Liver

cirrhosis

with

portal

hypertension

Signs

of

chronic

liver

disease

(as

above)

Cardiov

ascular

–

Right

heart

failure

Tricuspid

regurgitation

–

–

Infective

endocarditis

Constrictive

pericarditis

Ankle

oedema,

raised

JVP

Haematuria

and

peripher

al

signs

of

endocarditis

Miscellaneous

–

Polycystic

kidney

disease

(causing

liver

cysts)

–

–

Haemolytic

anaemias

(autoimmune

,

hereditary

spherocytosis)

Thalassaemia

Ballotable

kidneys/

nephrectomy

scar

Jaundice

(from

haemolysis)

16

Examinations:

3 Abdominal

occurs because of tertiary hyperparathyroidism and

although it looks like clubbing, with prominence of the

distal phalanges, what actually happens is that the prox-

imal phalanges become narrow, and this makes the

distal phalanges look prominent despite being normal.

Pseudoclubbing is common after renal replacement

therapy – patients with long-standing secondary

hyperparathyroidism (due to low calcium levels)

develop parathyroid hyperplasia, leading to increased

parathyroid hormone production that becomes auton-

omous of the negative feedback system. Once a patient

is undergoing renal replacement therapy and their

calcium levels normalise, the parathyroid continues

producing excess parathyroid hormone, which results

in hypercalcaemia and resorption of bone from the

proximal phalanges, causing them to narrow.

• Chronic liver disease and features of ESRF in the

same patient: This is rare, but don’t let it put you off.

The most likely cause is hepatitis C (leading to chronic

liver disease), which also causes membranous glomeru-

lonephritis (leading to ESRF).

• Spleen versus kidney: When palpating the left side

of the abdomen, it can sometimes be difficult to distin-

guish a ballotable kidney from a spleen. Table 3.3 below

summarises the key differences.

Figure 3.2 Nephrectomy scar

Figure 3.3 Right internal jugular tunnelled catheter (for dialysis)

Figure 3.1 Scar from splenectomy after a road traffic accident, also

showing the drain insertion site

Ballotable/ enlarged kidneys

Ballotable enlarged kidneys can be palpated in the

lateral lumbar regions. As with ESRF, you only need to

remember a short list of differential diagnosis:

• APKD

• Renal cell carcinoma

• Bilateral hydronephrosis (secondary to obstruction,

e.g. by an external mass, prostate enlargement, etc.)

• Amyloidosis (primary or secondary)

The key investigations with all of these are imaging (CT

of the kidney, ureter and bladder/IVU) and renal

biopsy, with the management depending on the under-

lying cause.

Rare findings

• Clubbing versus pseudoclubbing: Although these

conditions look similar on examination, the underlying

causes are fundamentally different. Pseudoclubbing

Examinations:

3 Abdominal 17

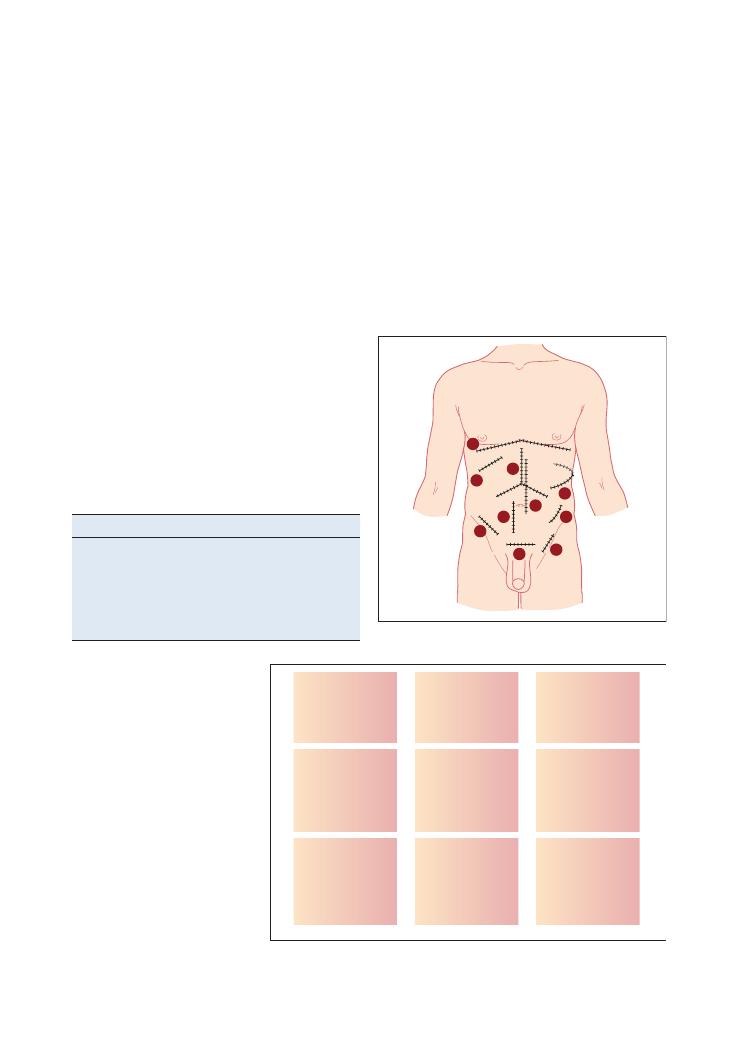

5) Nephrectomy scar (rarely adrenalectomy scar)

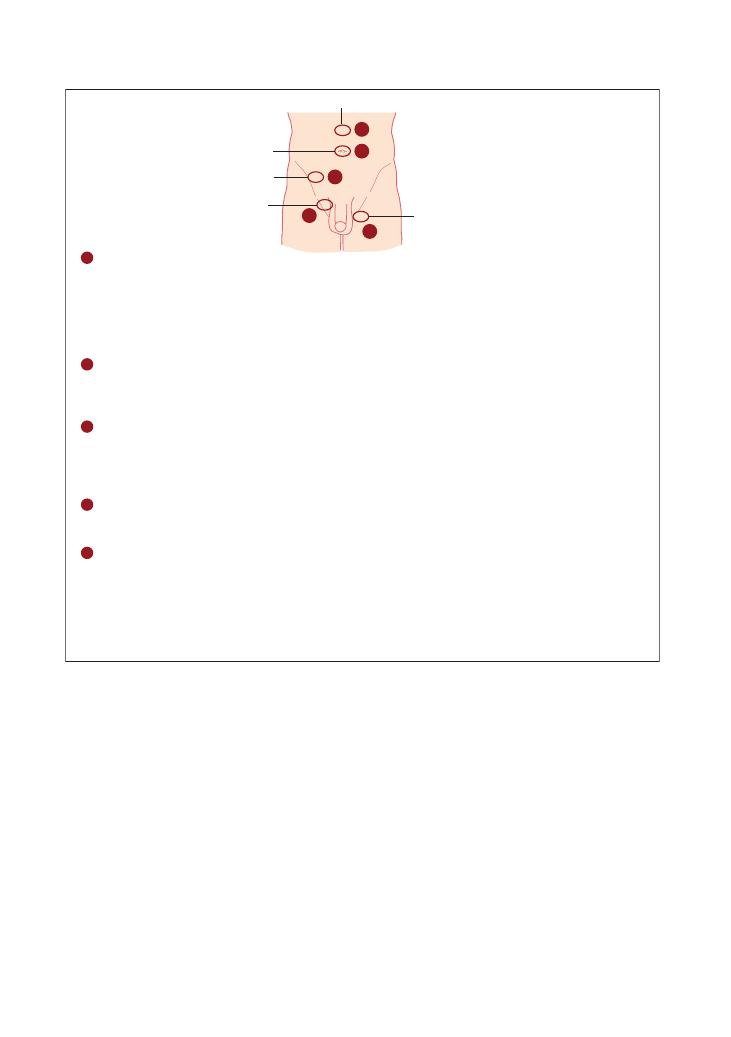

1. Classic caesarean section scar/hysterectomy scar

2. Appendicectomy scar: at McBurney’s point

3. Caesarean section scar (suprapubic)

4. Inguinal hernia scar

5. Femoral hernia scar

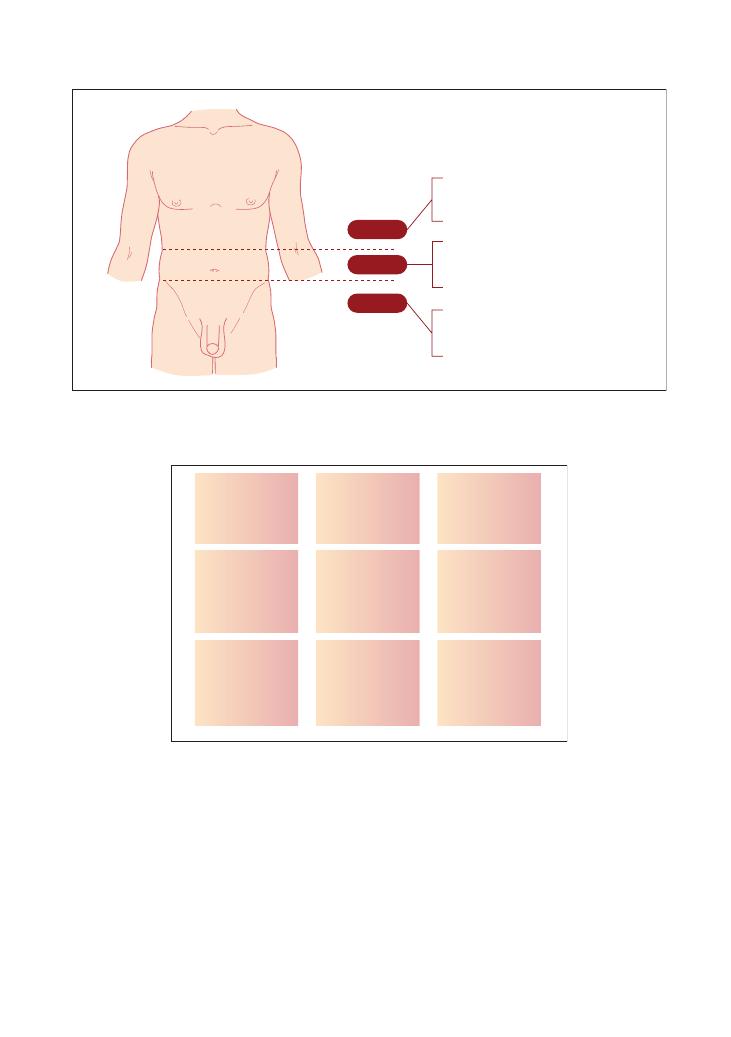

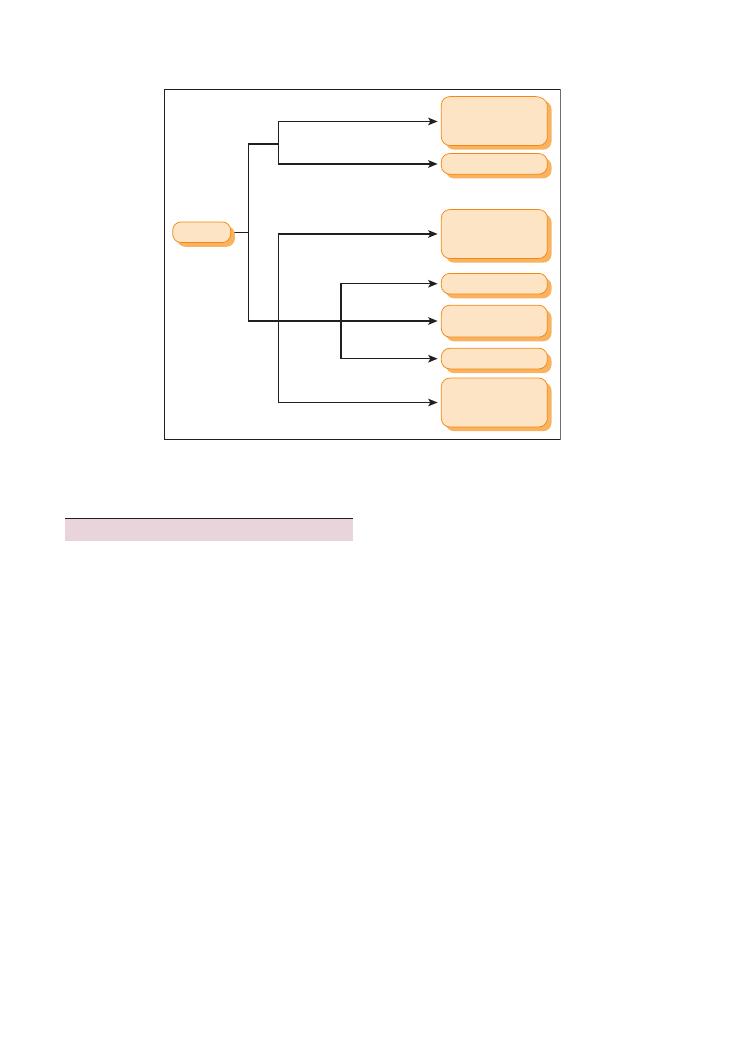

Abdominal masses

If you find a mass, try to answer two questions in your

mind.

1. Where is the mass?

First identify the quadrant where the mass is located,

and then think of the organs in that quadrant from

which the mass might originate (Figure 3.5).

Table 3.3 Spleen or kidney?

Spleen

Kidney

Cannot get above the spleen

Should be able to get above

the kidney

Moves downwards and

medially with inspiration

No movement with breathing

Not ballotable

Ballotable

Palpable notch (medial aspect)

No notch

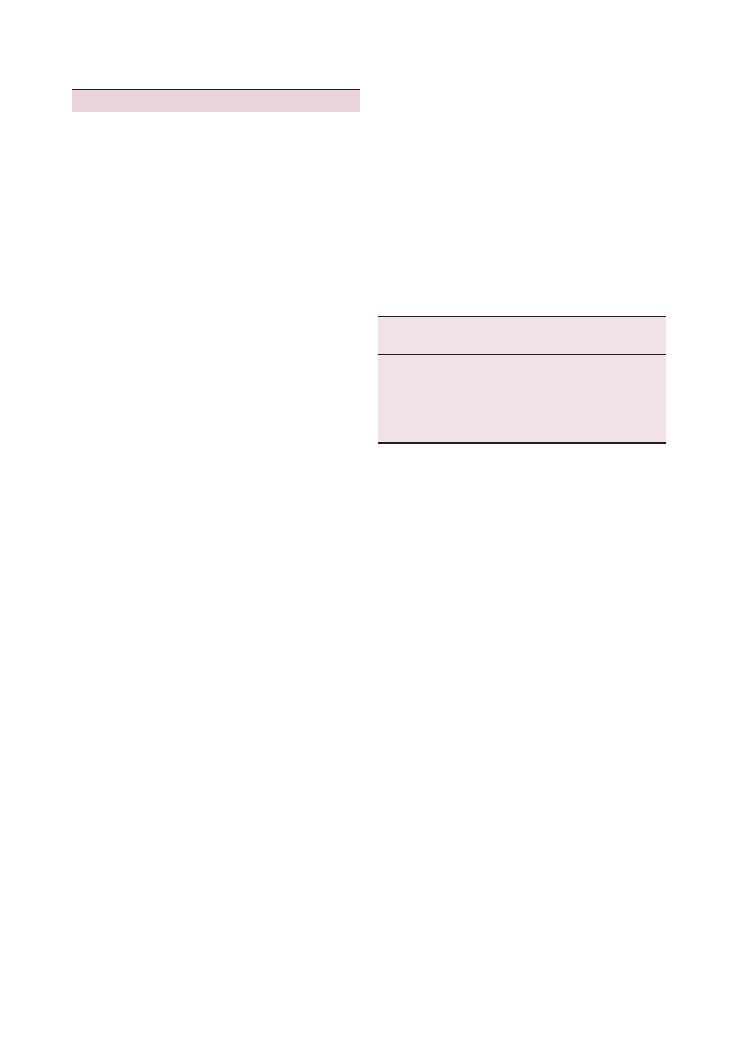

Figure 3.4 Common abdominal scars

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Figure 3.5 Location of organs in the

abdomen

Lung

Liver

Gallbladder

Stomach

Pancreas

Abdominal

aorta

Lung

Spleen

Pancreas

(rarely)

Liver

Kidney

Ureter

Stomach

Small intestine/

transverse colon

Abdominal

aorta

Spleen

Kidney

Ureter

Ureter

Ovary

Fallopian tube

Caecum

(appendix)

Bladder

Uterus

Cervix

(referred pain

from testicles)

Ureter

Ovary

Fallopian tube

Sigmoid colon

Theoretically, the spleen should be dull while the

kidney has traditionally been documented in most texts

to be ‘resonant’. This is, however, more theoretical than

realistic as in practice both kidneys and spleens feel dull

on percussion.

Abdominal scars

As with all OSCEs, the key findings in abdominal exam-

ination are often established on inspection (Figure 3.4):

1) Rooftop scar

• Partial hepatectomy

• Pancreatic surgery

• Accessing aorta

2) Kocher incision

• Cholecystectomy

3) ‘Mercedes-Benz’ scar

• Liver transplant

• Gastric surgery

• Oesophageal surgery

4) Midline laparotomy

• Colon surgery

• Aortic abdominal aneurysm surgery

18

Examinations:

3 Abdominal

Remember to describe the mass accurately and logi-

cally – see Chapter 10 on breast examination for a table

of characteristics that you should aim to describe.

2. What is the lesion?

As with everything in OSCEs, the key is to have a

generic method of categorising potential differential

diagnoses. The categories below can be used to devise

a differential diagnosis for a mass in almost any of the

nine quadrants:

• Tumour

• Benign

i. Cyst (liver, renal)

ii. Fibroids (in the pelvic area in women)

iii. Vascular (abdominal aortic aneurysm)

• Malignant

i. Primary

ii. Secondary

iii. Lymphoma

• Infection

• Abscess

• Tuberculosis (usually ileocaecal)

• Inflammatory bowel disease

• Crohn’s disease (in right iliac fossa)

• Diverticular disease (left iliac fossa)

Key investigations

The crux of investigating a mass is to visualise it and to

get a tissue sample from it. Hence the following inves-

tigations are most important:

• Imaging: CT/MRI scan

• Endoscopy: colonoscopy for colon, oesophago-

gastro-duodenoscopy for oesophagus/stomach, cystos-

copy for bladder

• Biopsy: for any non-vascular mass

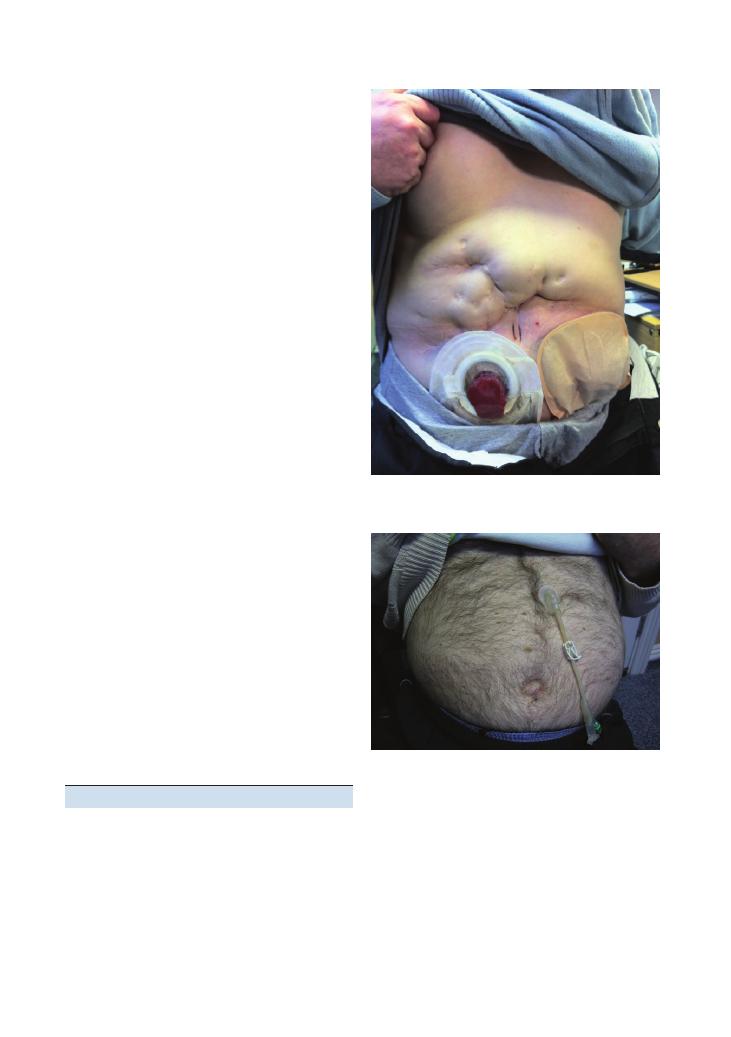

Stomas

Stomas (Figures 3.6 and 3.7) feature more commonly

in finals than most students think, and they are actually

quite easy to examine and talk about. The most

common stomas are ileostomies and colostomies, and

the key feature that distinguishes them is their location.

Table 3.4 summarises the key features.

Questions you could be asked

Q. What is the one investigation you would do in a

patient with known portal hypertension in order to

reduce mortality?

A. The key features of portal hypertension are:

• Splenomegaly

• Ascites

• Caput medusae

• Oesophageal varices

Figure 3.6 Stoma

Figure 3.7 Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG)

Although the answer to this is debatable, the most

important investigation would be an oesophago-

gastro-duodenoscopy to identify varices, and more

importantly to band them and prevent torrential acute

severe gastrointestinal bleeding.

Q. How big does the spleen have to be before it is

palpable?

A. About twice its normal size.

Examinations:

3 Abdominal 19

Q. Name some causes of a palpable liver without

hepatomegaly.

A.

• Lung hyperinflation (e.g. COPD) pushing it down

• Riedel’s lobe (on the left lateral side of liver)

• Gallbladder pathology

Table 3.4 Stomas

Ileostomy

Colostomy

Nephrostomy

Urostomy

Location

Right iliac fossa/lower

quadrant

Left iliac fossa

Flank

Right side of umbilicus

Reasons for use

Colon cancer (proximal)

IBD

Familial adenomatous

polyposis

Colon cancer (more distal)

Diverticulitis

Any cause of renal tract

obstruction

Any cause of renal tract

obstruction

Consistency of

products

Watery (as there is no

colonic absorption of

water)

Hard and dry (after colonic

absorption of water)

Urine

Urine (often has tiny amounts

of mucus produced by the

small intestinal conduit)

Mucosal

appearance

Mucosa protrudes

3–4 cm as a ‘spout’

No protrusion of mucosa

Usually no significant

mucosal protrusion

Usually no significant mucosal

protrusion

Permanent or

temporary

End-ileostomy (most

common): permanent

Loop ileostomy (rare):

temporary

End-colostomy: permanent

Loop colostomy: temporary

Usually temporary

Temporary or permanent

Q. What are ‘Terry’s nails’?

A. Terry’s nails signify chronic liver disease. They have

a characteristic appearance, being white proximally but

dark red distally, often in a concave shape.

20

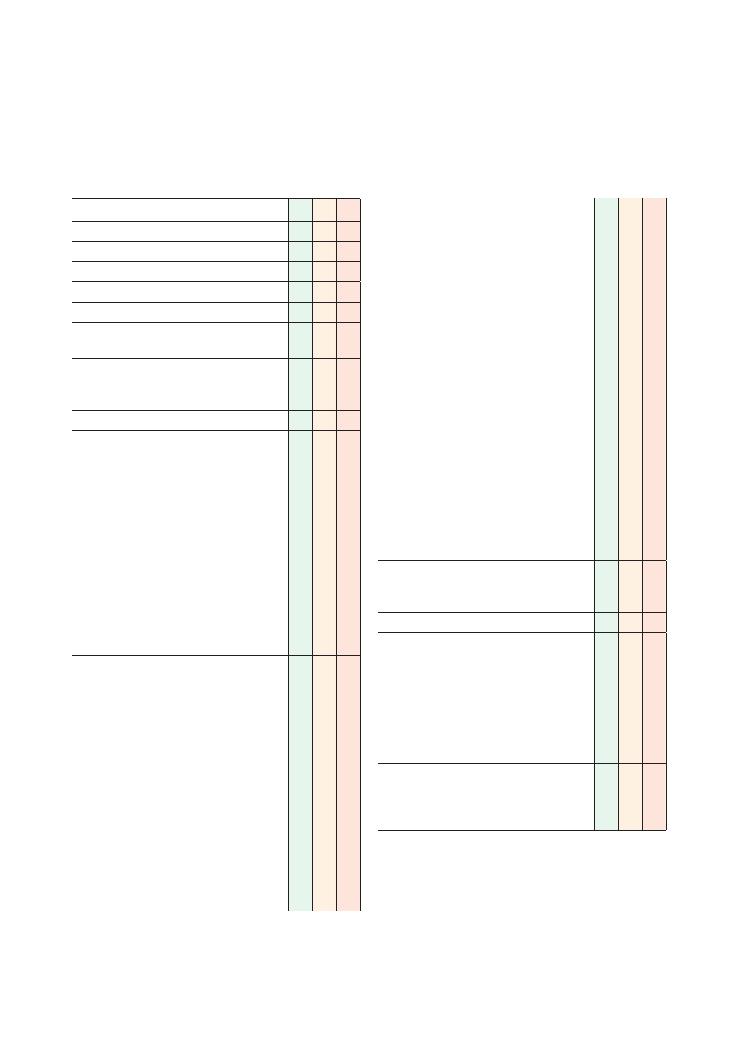

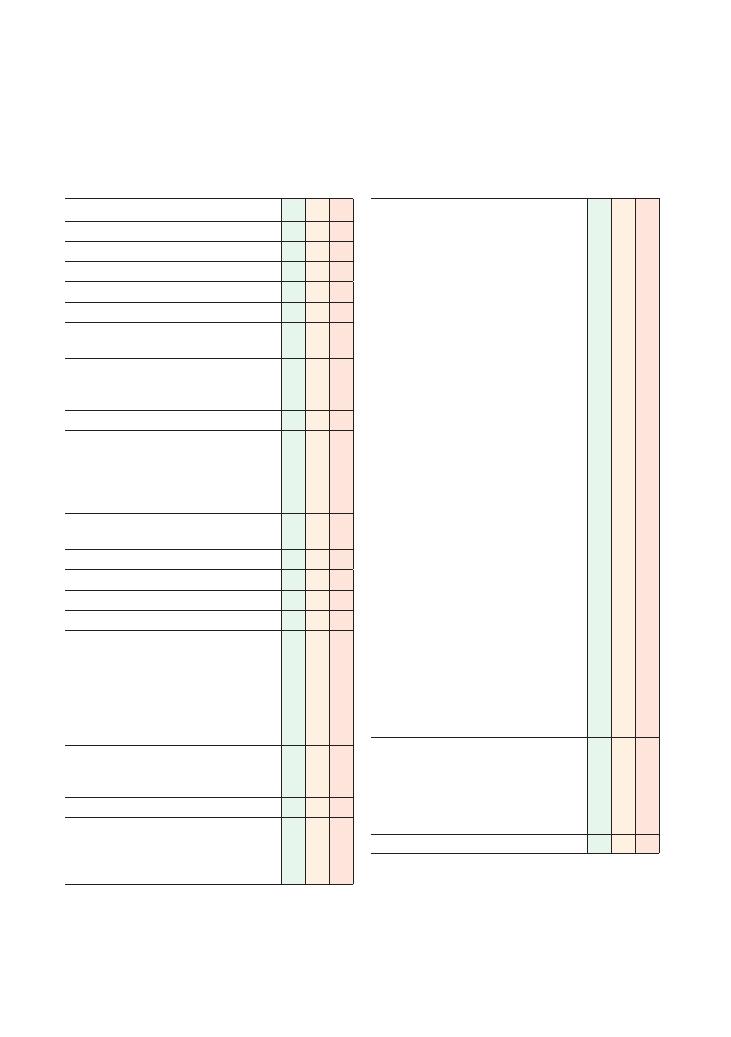

4 Peripheral nervous system

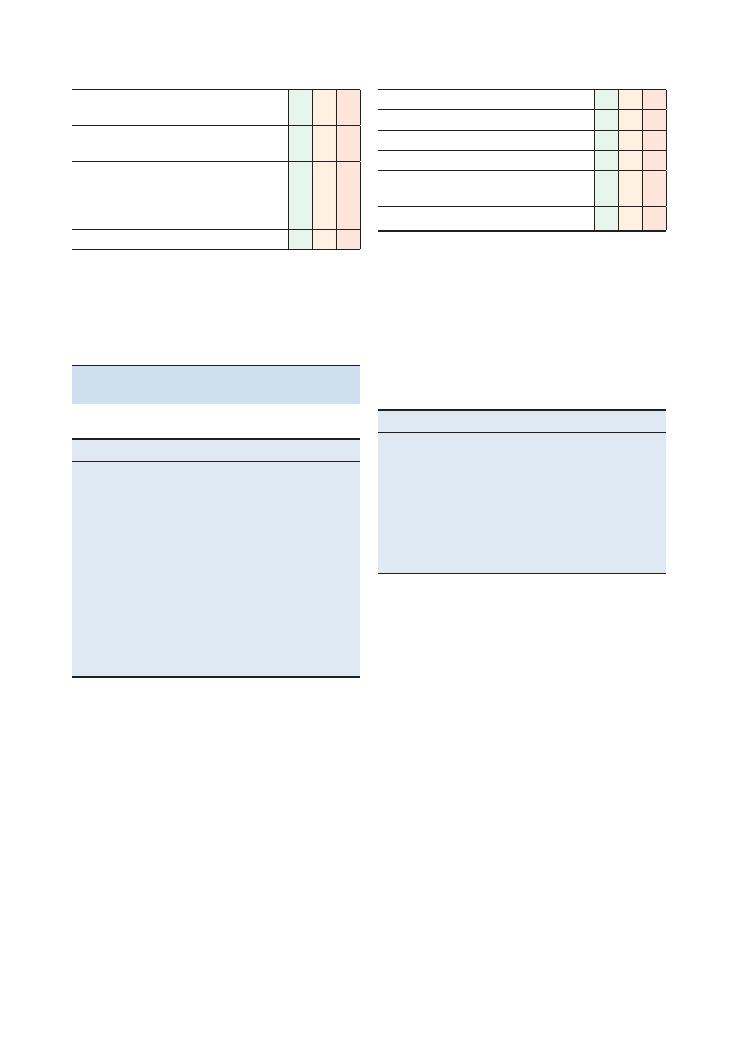

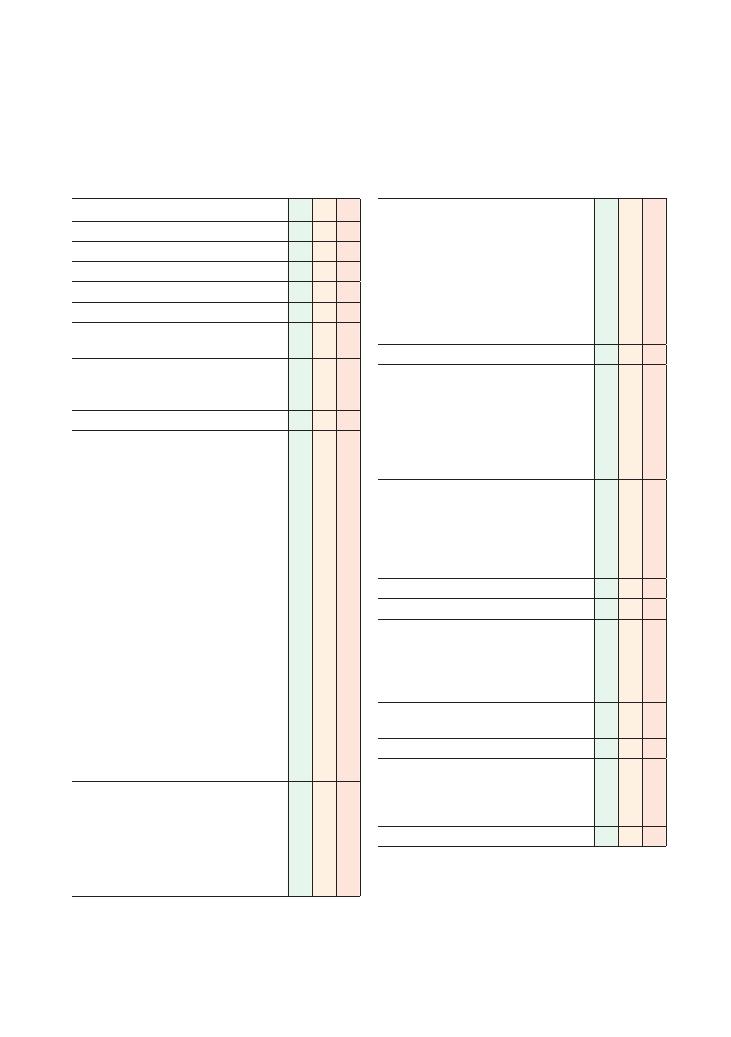

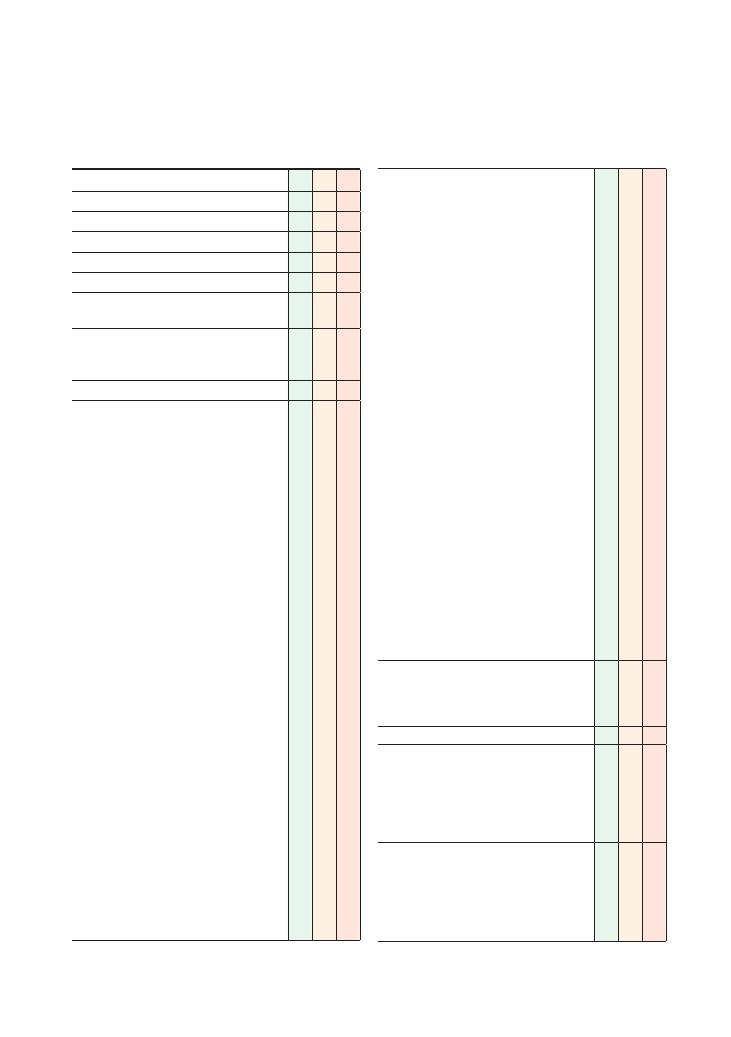

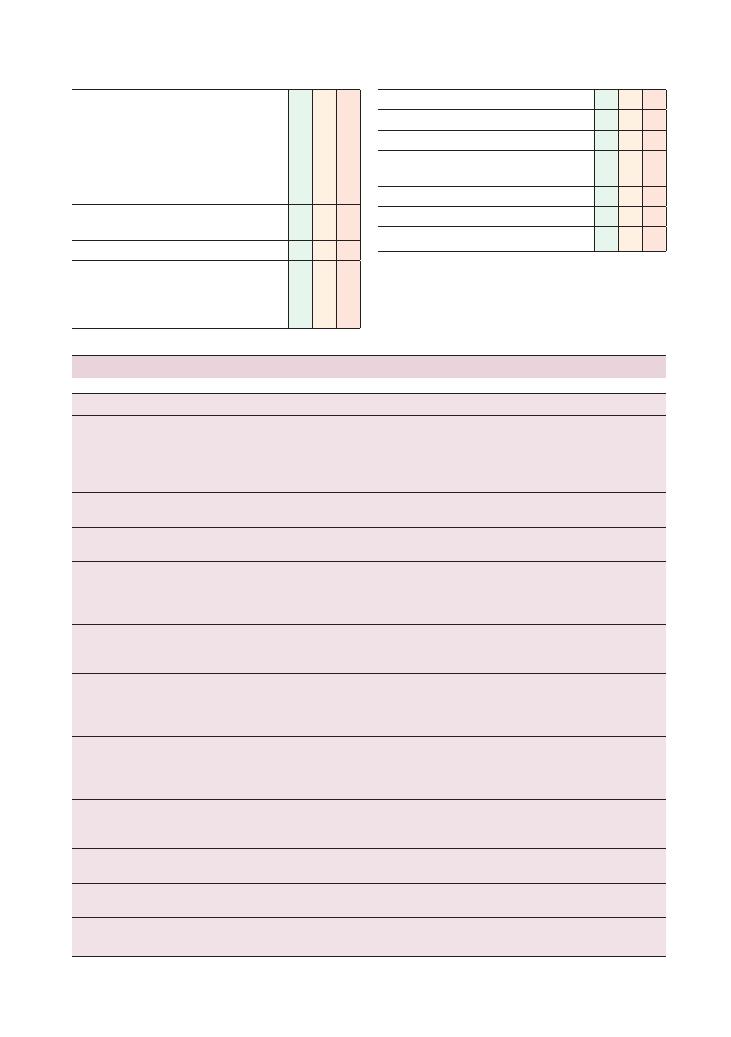

Checklist

P

MP

F

HELP:

H: ‘Hello’ (introduction and gains consent)

E: Exposure and explains he or she wants to

examine the nerves of the arms

L: Lighting

P: Have the patient in a position that they find

comfortable and in which the examination can

easily be undertaken

Washes hands

Inspects from end of bed:

• Relevant paraphernalia: walking stick, crutches,

foot supports, wheelchair, special glasses,

hearing aid

Inspects patient’s arms:

• Asymmetry

• Scars

• Skin changes

• Deformities

• Claw hand

• Wrist drop

• Fasciculations

• Wasting of small muscles of hands

• Scars

• Contractures

• Signs of denervation, such as:

• Injuries

• Neuropathic ulcers/Charcot joints

Inspects patient’s back:

• Spinal scars (back or side of neck)

• Kyphosis

Abnormal movements:

• Abnormal movements

• Tremor

• Dyskinesia

• Chorea

Upper limbs

Checklist

P

MP

F

Scars and skin changes

+ signs of denervation:

• Injuries

• Neuropathic ulcers

• Charcot joints

Inspects patient’s neck:

• Spinal scars – these can be at the back or on

the side of the neck

• Kyphosis

Motor examination

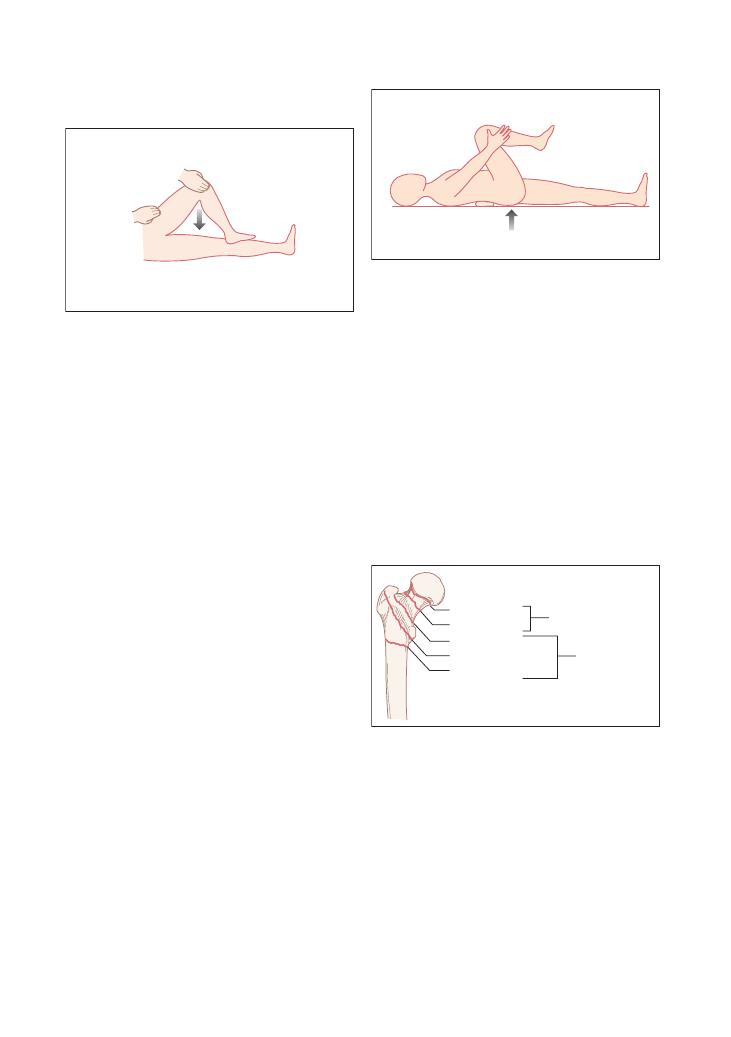

Screening test: Asks patient to raise both arms

forwards when in a supine position

Pronator drift: Asks patient to sit up and close

their eyes. Ask them to stretch their arms out

with the palms up at the level of their shoulders.

Looks for drift into pronation

Tone: Checks at each joint in flexion, extension,

pronation and supination

Power:

• Shoulder abduction: C5

• Shoulder adduction: C6, C7, C8

• Elbow flexion: C5, C6

• Elbow extension: C7

• Wrist flexion: C8

• Wrist extension: C7

• Fingers: T1

Fingers: flexion, extension, abduction, adduction,

opposition, grip strength

Thumb: abduction, adduction, extension

Reflexes:

• Reinforces if absent (clench teeth or apply

Jendrassik* manoeuvre)

• Biceps: C5/C6

• Triceps: C6/C7

• Supinator: C5/C6

Examinations:

4 Peripheral nervous system 21

Checklist

P

MP

F

Hoffman’s sign:

• Flexes and then suddenly releases distal

phalanx of middle finger

• Looks for abnormal flexion of other fingers

• This indicates an upper motor neuron lesion

Coordination:

• Finger–nose testing bilaterally

• Dysdiadochokinesis bilaterally

• Looks for intention tremor and past-pointing

• Tests for rebound by pushing down on the

outstretched arms and looking for rebound

past the original position

Sensory examination

Explains examination to patient and checks their

sensation on a part of the body known to have

normal sensation (such as forehead or sternum)

Examines the following modalities on all

dermatomes:

• Dermatomes of the upper limbs:

• C3: lateral neck

• C4: lateral shoulder

• C5: lateral upper arm

• C6: thumb

• C7: middle finger

• C8: little finger

• T1: medial lower arm

• T2: medial upper arm

• T3: axilla

• Dermatomes of the lower limbs:

• L1: just below groin

• L2: medial aspect of mid-thigh

• L3: knee

• L4: medial lower leg

• L5: big toe

• S1: little toe

• S2: medial aspect of back of knee

Pin-prick (spinothalamic tract): uses a Neurotip

Checklist

P

MP

F

Vibration(dorsal column): uses a 128 Hz tuning

fork on most distal phalanx, and only proceeds

proximally if a deficit is identified

Joint proprioception(dorsal column):

• Only proceeds proximally if a deficit is

identified

• Holds terminal phalanx of thumb. Shows

patient that ‘up’ means extension and

‘down’ means flexion. Asks them to close

their eyes. Moves phalanx and ask them to

say if it is ‘up’ or ‘down’. Only proceeds

proximally to the wrists and elbows if a

deficit is identified. Offers to perform

two-point discrimination using calipers

Light touch (dorsal column): uses a wisp of

cotton wool

Temperature (spinothalamic tract): offers to use

syringes of hot and cold water

Identifies pattern of sensory loss:

• Identifies if the pattern is dermatomal or

‘glove and stocking’

• Identifies level if it is dermatomal

Special tests: performs these based on the likely

diagnosis from the examination. Common ones

to know are Phalen’s, Tinel’s and Froment’s

Thanks patient

Offers to help patient get dressed

Washes hands

Presents findings

Offers appropriate differential diagnosis

Suggests appropriate further investigations and

management

OVERALL IMPRESSION:

*If the reflexes are difficult to elicit, reinforce them by asking the

patient to interlock their fingers and pull them in opposite directions

(Jendrassik manoeuvre).

22

Examinations:

4 Peripheral nervous system

Checklist

P

MP

F

HELP:

H: ‘Hello’ (introduction and gains consent)

E: Exposure (shorts or underwear)

+ explains he

or she wants to examine the nerves of the legs

L: Lighting

P: Have the patient in a position that they find

comfortable and in which the examination can

easily be undertaken. Ensure privacy and dignity

Washes hands

Inspects from the end of the bed for

paraphernalia: walking stick, crutches, foot

supports, wheelchair, special glasses, hearing aid

Inspects patient’s legs:

• Fasciculations

• Wasting of proximal and distal lower limb

muscles

• Scars

• Skin changes

• Signs of denervation (injuries, neuropathic

ulcers, Charcot joints)

• Contractures

• Pes cavus

• Foot drop

• Deformities

• Abnormal movements

Inspects patient’s back:

• Spinal scars

• Kyphosis, scoliosis

MOTOR EXAMINATION

Gait: Asks patient to walk and turn, and

observes gait carefully and any walking aids the

patient uses. Assesses heel–toe gait and patient’s

ability to stand on tiptoes

Romberg’s test:

• Asks patient to stand with both feet together

and their arms to their sides, first with their

eyes open and then with their eyes closed

• Positive if patient appears to be falling

(indicates dorsal column or sensory nerve

pathology) – ensure that patient does not

fall!

Lower limbs

Checklist

P

MP

F

Tone:

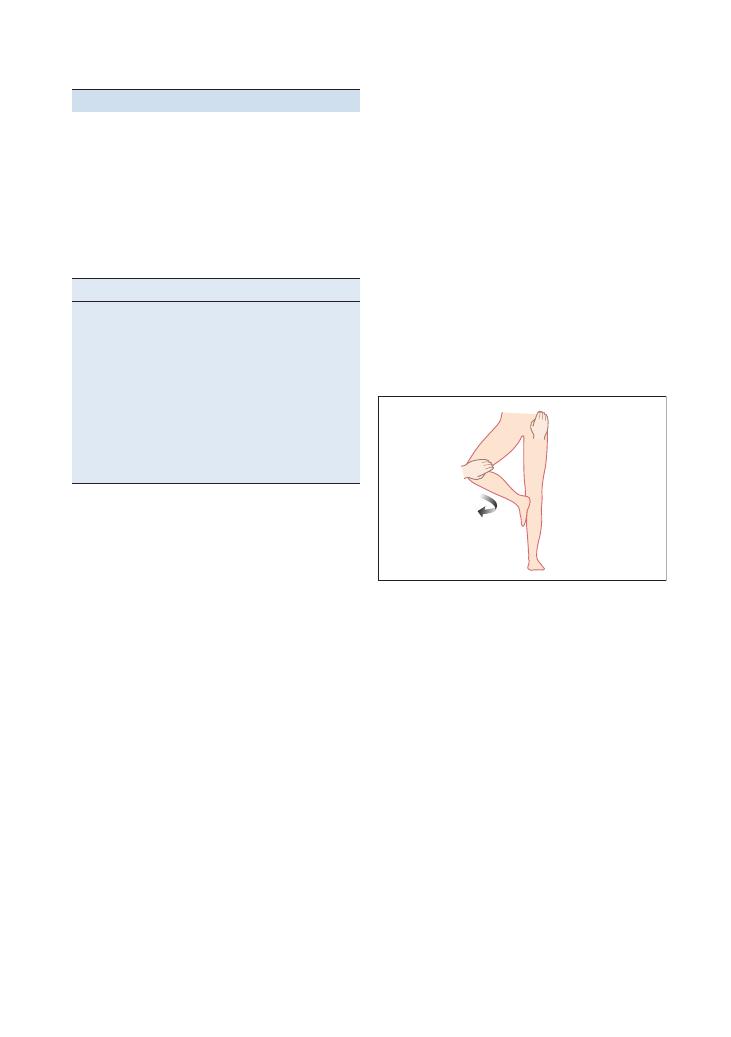

1) Lifts the knees quickly off the ground

2) ‘Rolls’ both hips gently

3) Checks for clonus (using ankle dorsiflexion)

Power:

Hip flexion: L1, L2

Hip extension: L5, S1

Knee flexion: L5, S1

Knee extension: L3, L4

Ankle dorsiflexion: L4, L5

Ankle plantarflexion: S1, S2

Foot inversion: L4, L5

Foot eversion: L5, S1

Toe movements: L5, S1

Reflexes:

Reinforces if absent (clench teeth or Jendrassik*

manoeuvre)

Knee: L3/4

Ankle: L5/S1

Plantar: Up (upper motor neurone lesion) or

down (lower motor neurone lesion/normal)

Coordination: Heel–shin testing bilaterally, gait

SENSORY EXAMINATION

Explains examination to patient and checks their

sensation on a part of the body known to have

normal sensation (such as forehead or sternum)

Examines following modalities on all

dermatomes:

• Pin-prick (spinothalamic tract): uses a

Neurotip

• Vibration (dorsal column): uses a 128 Hz

tuning fork on most distal phalanx, and only

proceeds proximally if a deficit is identified

• Joint proprioception (dorsal column):

• Holds great toe and shows patient that ‘up’

means extension and ‘down’ means flexion.

Then asks them to close their eyes, and

moves the toe, asking patient to say if it is

moving ‘up’ or ‘down’

• Only proceeds proximally if a deficit is

identified

• Offers to perform two-point discrimination

using calipers

Examinations:

4 Peripheral nervous system 23

*If the reflexes are difficult to elicit, reinforce them by asking the

patient to interlock their fingers and pull them in opposite directions

(Jendrassik manoeuvre).

Checklist

P

MP

F

• Light touch (dorsal column): uses a wisp of

cotton wool

• Temperature (spinothalamic tract): offers to

use syringes of hot and cold water

• Identifies pattern of sensory loss:

• Identifies if the pattern is dermatomal or

‘glove and stocking’

• Identifies level if it is dermatomal

Thanks patient

Checklist

P

MP

F

Offers to help patient get dressed

Washes hands

Presents findings

Offers appropriate differential diagnosis

Suggests appropriate further investigations and

management

OVERALL IMPRESSION:

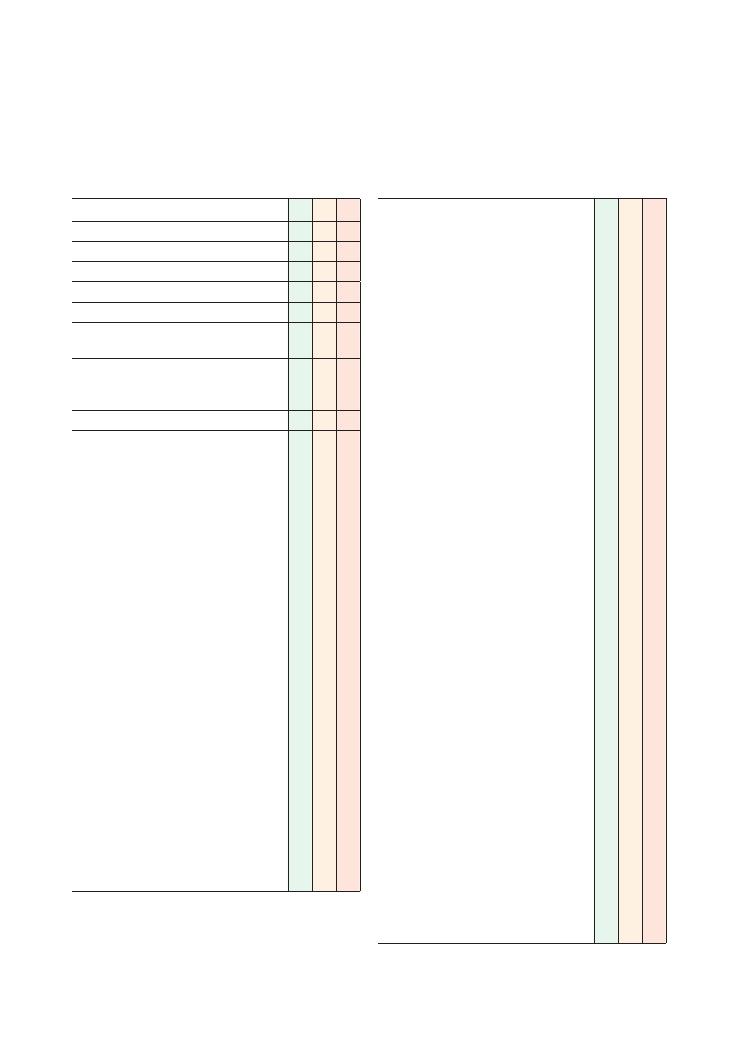

Summary of common conditions seen

in OSCEs

List of common cases

Lower limb

Upper limb

Foot drop

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Post stroke

Ulnar nerve palsy

Cerebellar degeneration

Wrist drop

Sensory neuropathy

Axillary nerve palsy

Radiculopathy secondary to spinal

pathology

Volkmann’s contracture

Cerebral palsy

Cervical rib

Muscular dystrophy

Cerebellar degeneration

Pes cavus

Tremor – Parkinson’s

disease, essential tremor

Old cauda equina syndrome

Post stroke

Old polio

Motor neurone disease

Brown–Sequard syndrome

Erb’s or Klumpke’s palsy

Common patterns of weakness,

and common causes for them

Pattern of weakness

Common causes

Proximal muscle weakness

Myopathy

Distal weakness

Inherited myopathies

Hemiparesis

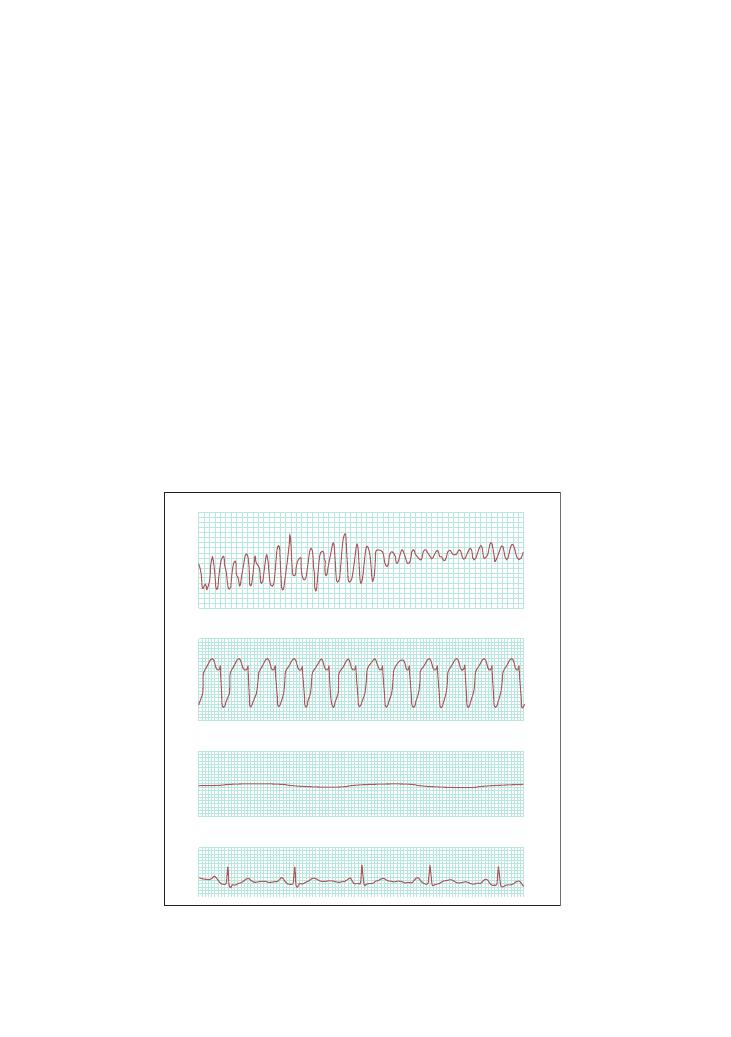

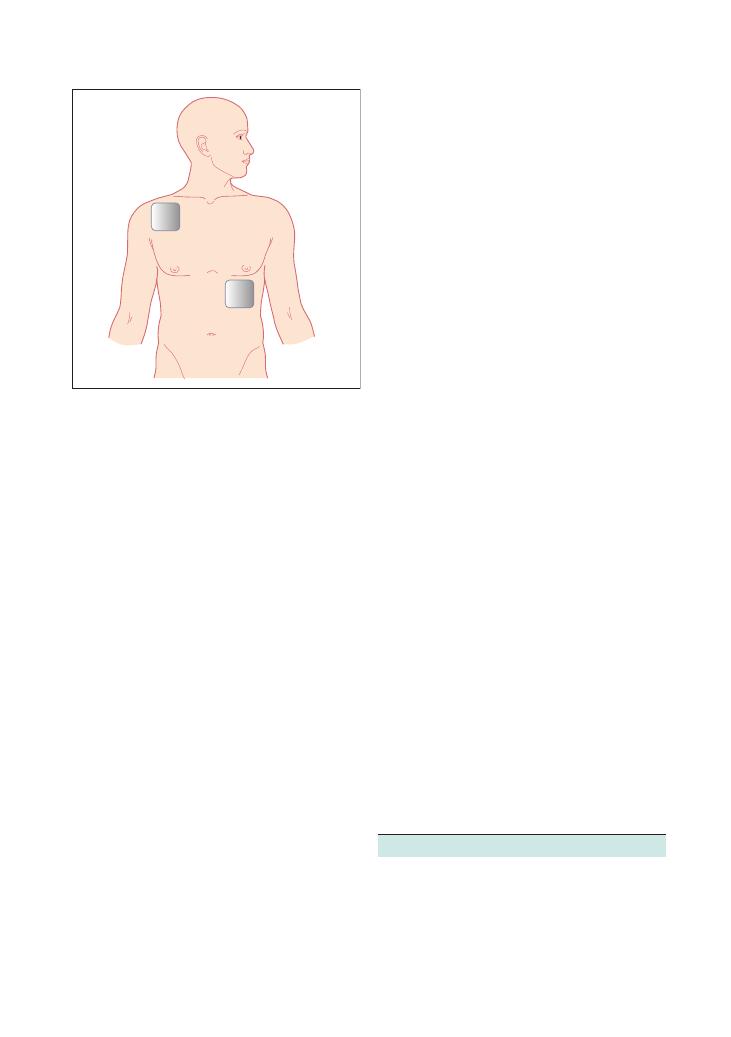

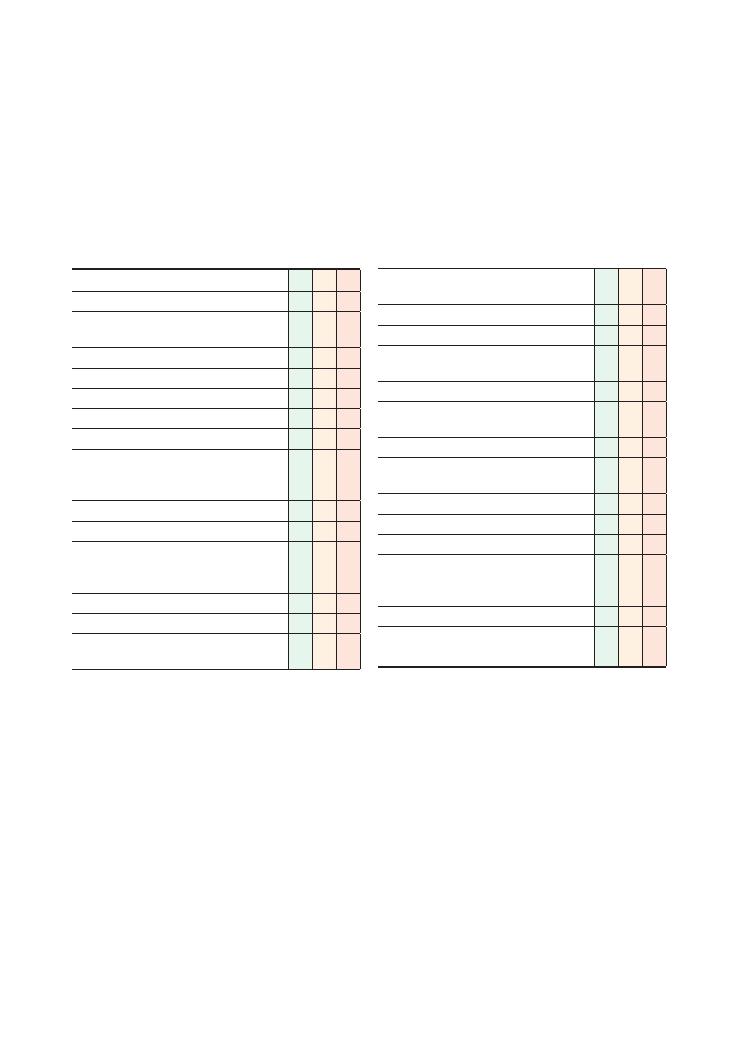

Cerebral pathology