Chapter 5 – Cardiovascular disease

112

“” Vascular disease “”

(Printed by Mostafa Hatim)

- Peripheral arterial disease - Diseases of aorta – Hypertension

Hypertension

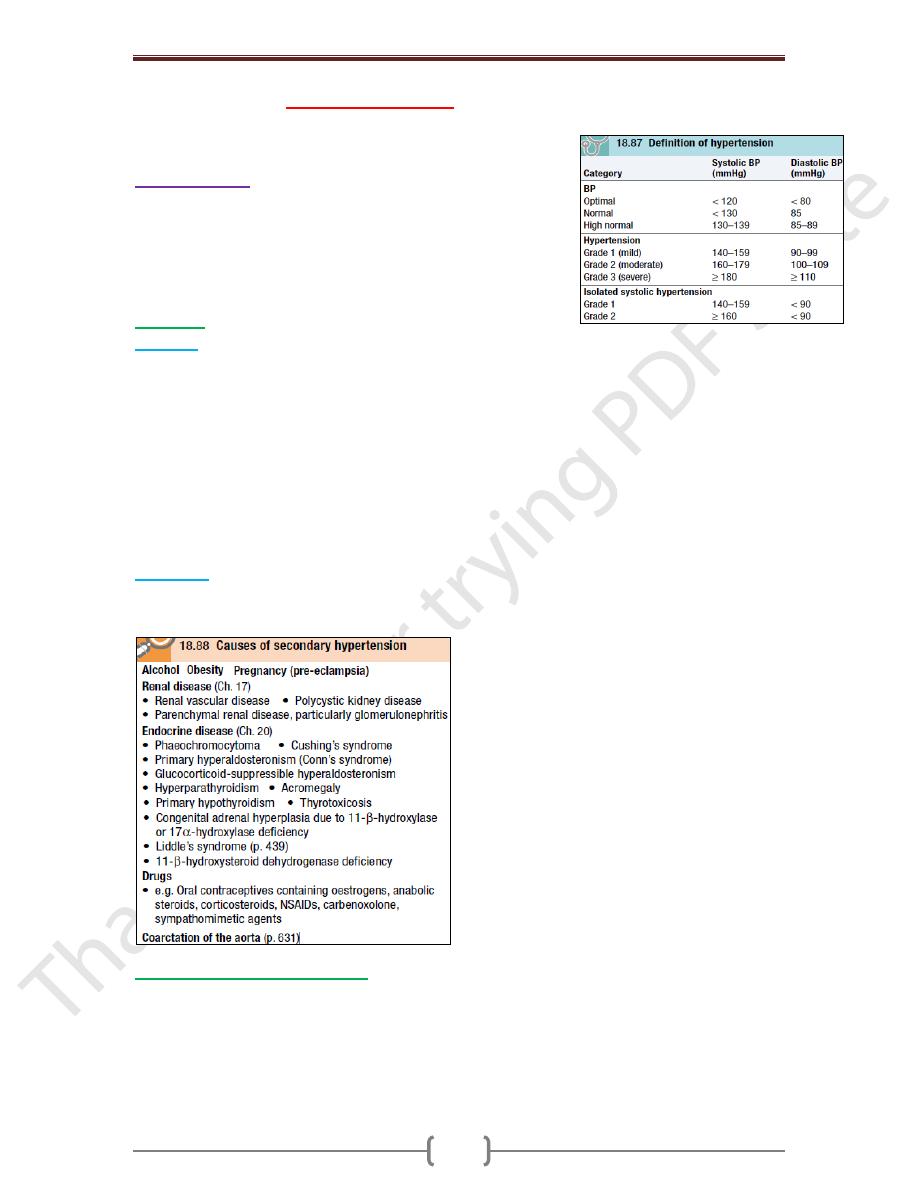

is a condition in which arterial BP is chronically elevated. BP

occurs within a continuous range, so cutoff levels are defined

according to their effect on patients’ risk. The British Hypertension

Society has defined ranges of BP which are normal and those that

indicate hypertension.

Aetiology

Essential

o In >95% of cases, a specific underlying cause of hypertension cannot be found. Such

patients are said to have essential HP. The pathogenesis of this is not clearly understood.

Many factors may contribute to its development, including:

o renal dysfunction, peripheral resistance vessel tone, endothelial dysfunction, autonomic

tone, insulin resistance and neurohumoral factors.

o hypertension is more common in some ethnic groups, particularly Black Americans and

Japanese, and approximately 40–60% is explained by genetic factors.

o Important environmental factors include a high salt intake, heavy consumption of

alcohol, obesity, lack of exercise and impaired intrauterine growth. There is little

evidence that ‘stress’ causes hypertension.

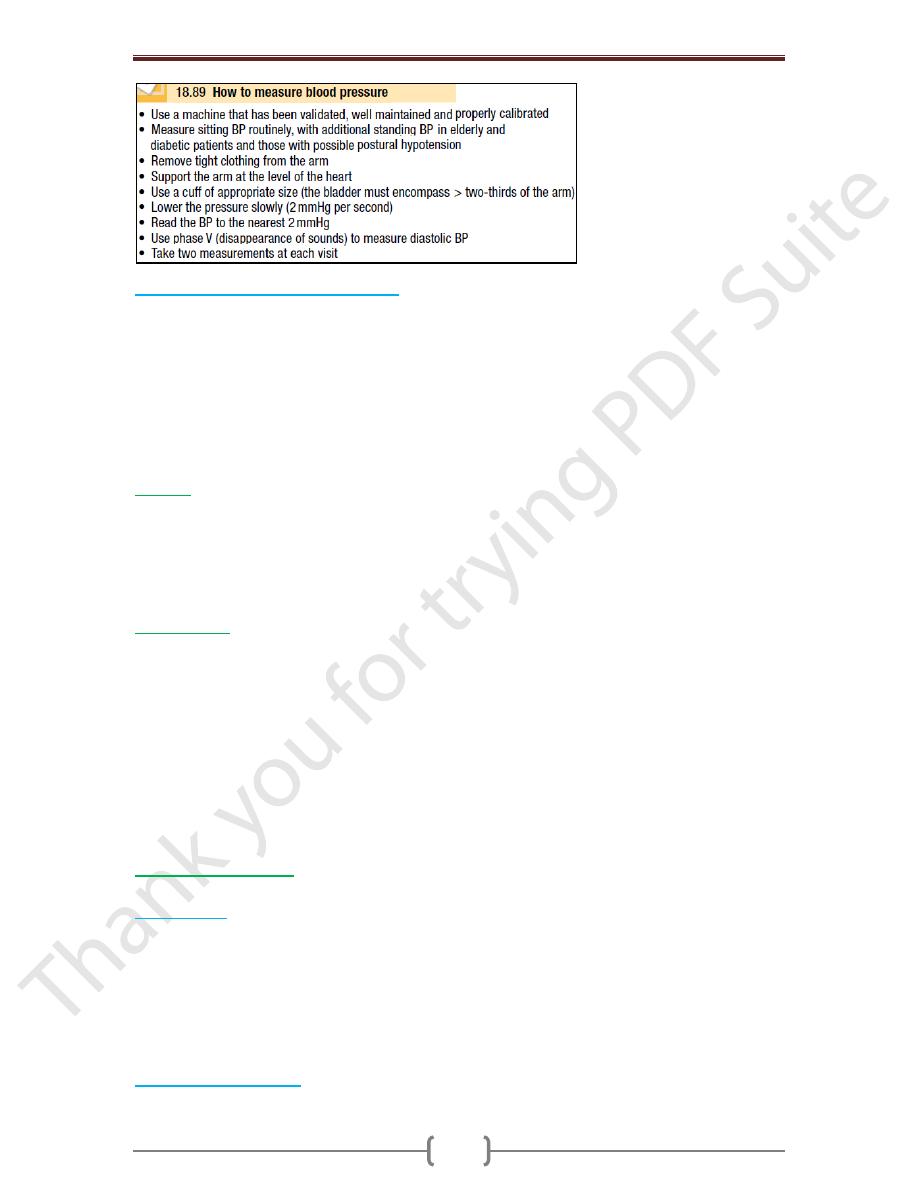

Secondary

In about 5% of cases, hypertension can be shown to be a consequence of a specific

disease or abnormality leading to sodium retention &/or peripheral vasoconstriction.

Measurement of blood pressure

A decision to embark upon antihypertensive therapy effectively commits the patient to

life-long treatment, so BP readings must be as accurate as possible.

Measurements should be made to the nearest 2 mmHg, in the sitting position with the arm

supported, and repeated after 5 minutes’ rest if the first recording is high (Box 18.89). To

avoid spuriously high recordings in obese subjects, the cuff should contain a bladder that

encompasses at least two-thirds of the circumference of the arm.

Chapter 5 – Cardiovascular disease

113

Home and ambulatory BP recordings

Exercise, anxiety, discomfort & unfamiliar surroundings can all lead to a transient rise in

BP. A series of automated ambulatory BP measurements obtained over 24 hours or longer

provides a better profile than a limited number of clinic readings & correlates more closely

with evidence of target organ damage than casual BP measurements. The average

ambulatory daytime (not 24hr or nighttime) BP should be used to guide management

decisions. Patients can measure their own BP at home using a range of commercially

available semi-automatic devices. The value of such measurements is less well

established & is dependent on the environment & timing of the readings measured.

History

Family hx, lifestyle (exercise, salt intake, smokin habit) & other risk factors should be

recorded. A careful hx will identify those patients with drug- or alcohol-induced

hypertension & may elicit the symptoms of other causes of secondary hypertension such

as phaeochromocytoma (paroxysmal headache, palpitation & sweating) or complications

such as coronary artery disease (e.g. angina, breathlessness).

Examination

Radio-femoral delay (coarctation of the aorta), enlarged kidneys (polycystic kidney

disease), abdominal bruits (renal artery stenosis) & the characteristic facies and habitus of

Cushing’s syndrome are all examples of physical signs that may help to identify causes of

secondary hypertension. Examination may also reveal features of important risk factors

such as central obesity and hyperlipidaemia (tendon xanthomas etc.). Most abnormal

signs are due to the complications of hypertension.

Non-specific findings may include left ventricular hypertrophy (apical heave),

accentuation of the aortic component of the S2, and a S4. The optic fundi are often

abnormal and there may be evidence of generalized atheroma or specific complications

such as aortic aneurysm or peripheral vascular disease.

Target organ damage

The adverse effects of hypertension on the organs can often be detected clinically.

Blood vessels:

In larger arteries (> 1 mm in diameter), the internal elastic lamina is

thickened, smooth muscle is hypertrophied and fibrous tissue is deposited. The vessels

dilate and become tortuous, and their walls become less compliant. In smaller arteries (<

1 mm), hyaline arteriosclerosis occurs in the wall, the lumen narrows and aneurysms

may develop. Widespread atheroma develops and may lead to coronary and

cerebrovascular disease, particularly if other risk factors (e.g. smoking, hyperlipidaemia,

diabetes) are present. Hypertension is a major risk factor in the pathogenesis of aortic

aneurysm and aortic dissection.

Central nervous system:

Stroke may be due to cerebral haemorrhage or infarction.

Carotid atheroma and transient ischaemic attacks. Subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Chapter 5 – Cardiovascular disease

114

Hypertensive encephalopathy is a rare condition characterised by high BP & neurological

symptoms, including transient disturbances of speech or vision, paraesthesiae,

disorientation, fits and loss of consciousness. Papilloedema is common. However, the

neurological deficit is usually reversible if the hypertension is properly controlled.

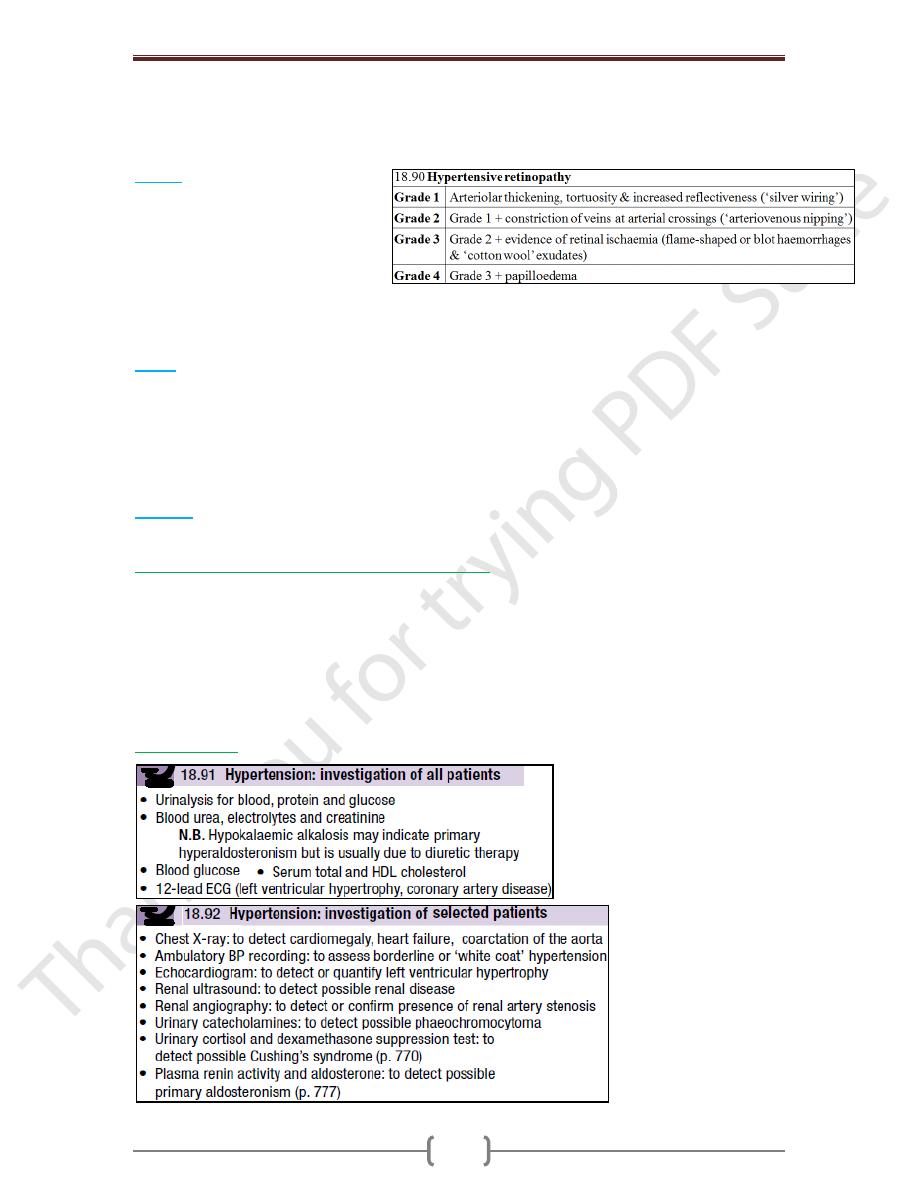

Retina:

The optic fundi reveal a

gradation of changes linked to the

severity of hypertension (Box 18.90).

‘Cotton wool’ exudates are

associated with retinal ischaemia or

infarction, and fade in a few weeks.

‘Hard’ exudates (small, white, dense deposits of lipid) and microaneurysms (‘dot’

haemorrhages) are more characteristic of diabetic retinopathy. Hypertension is also

associated with central retinal vein thrombosis.

Heart:

The excess cardiac mortality and morbidity associated with hypertension are

largely due to a higher incidence of coronary artery disease. High BP places a pressure

load on the heart and may lead to left ventricular hypertrophy with a forceful apex

beat & S4. Atrial fibrillation is common and may be due to diastolic dysfunction caused

by left ventricular hypertrophy or the effects of coronary artery disease. Severe

hypertension can cause left ventricular failure in the absence of coronary artery disease,

particularly when renal function, and therefore sodium excretion, is impaired.

Kidneys

:

Long-standing hypertension may cause proteinuria & progressive renal failure

by damaging the renal vasculature.

‘Malignant’ or ‘accelerated’ phase hypertension

This rare condition may complicate hypertension of any aetiology and is characterised by

accelerated microvascular damage with necrosis in the walls of small arteries and

arterioles (‘fibrinoid necrosis’) and by intravascular thrombosis. The diagnosis is based

on evidence of high BP and rapidly progressive end organ damage, such as retinopathy

(grade 3 or 4), renal dysfunction (especially proteinuria) and/or hypertensive

encephalopathy (see above). Left ventricular failure may occur and, if this is untreated,

death occurs within months.

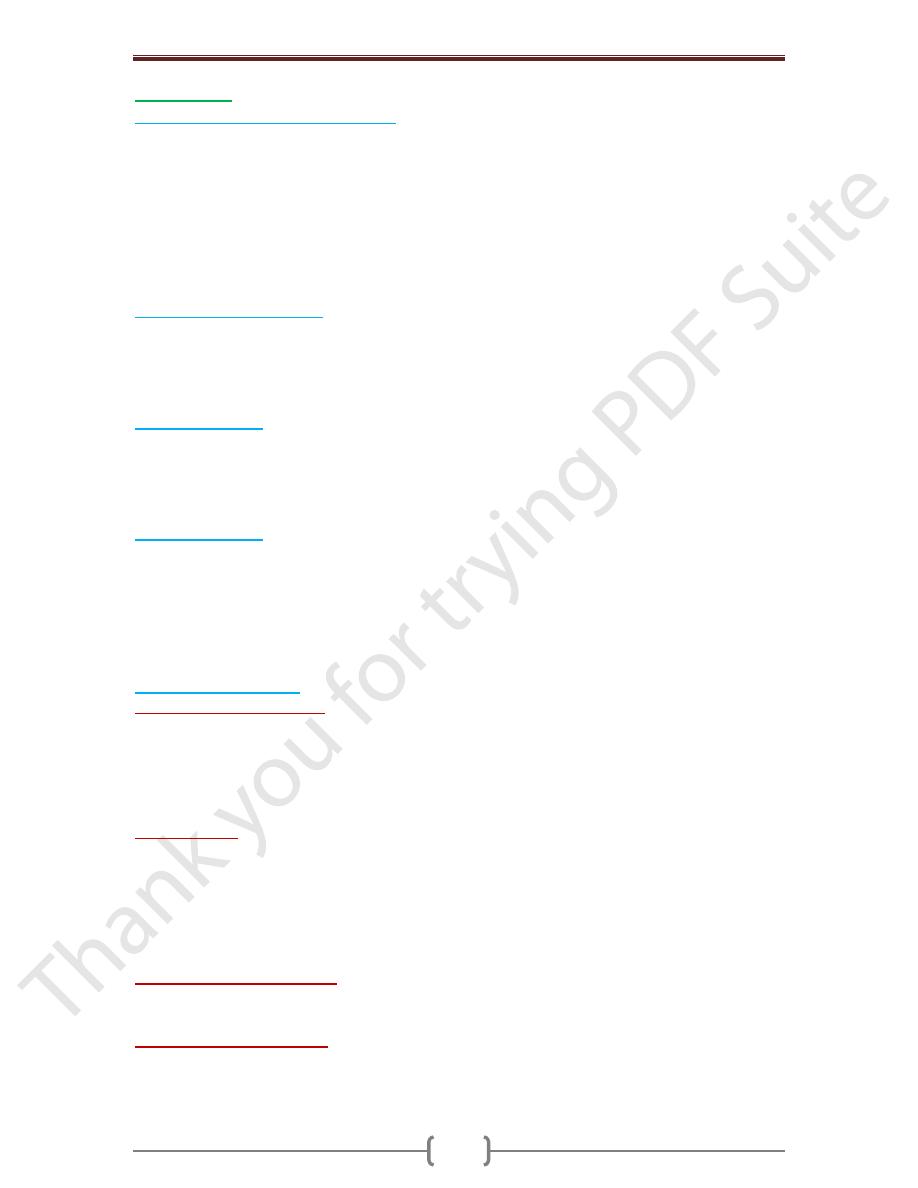

Investigations

Chapter 5 – Cardiovascular disease

115

Management

Quantification of cardiovascular risk

The sole objective of antihypertensive therapy is to reduce the incidence of adverse CV

events, particularly CHD, stroke & HF. Benefit of antihypertensive drug therapy:

Diuretics or β-blockers have been shown to reduce the risk of CHD by 16%, stroke by

38%, CV death by 21% & all causes of mortality by 13%. The effects of ACE inhibitors

& calcium antagonists are similar. NNTB varies greatly according to the absolute

baseline risk of CVD. Most of the excess morbidity & mortality associated with

hypertension is attributable to CHD & many treatment guidelines are therefore based on

estimates of the 10-year CHD risk.

Threshold for intervention:

Systolic & diastolic BP are both powerful predictors of CV risk. Patients with diabetes or

CVD are at particularly high risk & the threshold for initiating antihypertensive therapy is

therefore lower (≥ 140/90 mmHg). The thresholds for treatment in the elderly are the

same as for younger patients

Treatment targets

The optimum BP for reduction of major CV events has been found to be 139/83 mmHg

& even lower in patients with DM. Moreover, reducing BP below this level causes no

harm. Patients taking antihypertensive therapy require follow-up at 3-monthly intervals to

monitor BP, minimize side-effects and reinforce lifestyle advice.

Non-drug therapy

Appropriate lifestyle measures may obviate the need for drug therapy in patients with

borderline hypertension, reduce the dose &/or the number of drugs required in patients with

established hypertension & directly reduce CV risk. Correcting obesity, reducing alcohol

intake, restricting salt intake, taking regular physical exercise & increasing consumption of

fruit & vegetables can all lower BP. Moreover, quitting smoking, eating oily fish &

adopting a diet that is low in saturated fat may produce further reductions in CV risk.

Antihypertensive drugs

o Thiazide and other diuretics.

The mechanism of action of these drugs is incompletely

understood and it may take up to a month for the maximum effect to be observed. An

appropriate daily dose is 2.5 mg bendroflumethiazide or 0.5 mg cyclopenthiazide. More

potent loop diuretics, such as furosemide 40 mg daily or bumetanide 1 mg daily, have

few advantages over thiazides in the treatment of hypertension unless there is substantial

renal impairment or they are used in conjunction with an ACE inhibitor.

o ACE inhibitors

(e.g. enalapril 20 mg daily, ramipril 5–10 mg daily or lisinopril 10–40

mg daily). These inhibit the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II & are usually

well tolerated. They should be used with particular care in patients with impaired renal

function or renal artery stenosis because they can reduce the filtration pressure in the

glomeruli & precipitate renal failure. Electrolytes & creatinine should be checked

before & 1–2 wks after commencing therapy. Side-effects include firstdose hypotension,

cough, rash, hyperkalaemia & renal dysfunction.

o Angiotensin receptor blockers

(e.g. irbesartan 150–300 mg daily, valsartan 40-160 mg

daily). These block the angiotensin II type I receptor and have similar effects to ACE

inhibitors; however, they do not cause cough and are better tolerated.

o Calcium channel antagonists.

The dihydropyridines (e.g. amlodipine 5–10 mg daily,

nifedipine 30–90 mg daily) are effective & usually well-tolerated antihypertensive drugs

that are particularly useful in older people. Side effects include flushing, palpitations &

fluid retention. The rate-limiting calcium channel antagonists (e.g. diltiazem 200–300 mg

Chapter 5 – Cardiovascular disease

116

daily, verapamil 240 mg daily) can be useful when hypertension coexists with angina but

they may cause bradycardia. The main side-effect of verapamil is constipation.

o

β-blockers.

are no longer used as firstline antihypertensive therapy, except in patients

with another indication for the drug (e.g. angina). Metoprolol (100-200 mg daily),

atenolol (50-100 mg daily) & bisoprolol (5–10 mg daily) preferentially block cardiac β1-

adrenoceptors, as opposed to the β2-adrenoceptors that mediate vasodilatation &

bronchodilatation.

o Labetalol and carvedilol.

Labetalol (200 mg–2.4 g daily in divided doses) and

carvedilol (6.25–25 mg 12-hourly) are combined β- and α-adrenoceptor antagonists

which are sometimes more effective than pure β-blockers. Labetalol can be used as an

infusion in malignant phase hypertension.

o Other drugs.

A variety of vasodilators may be used. These include the α1-adrenoceptor

antagonists (α-blockers), such as prazosin (0.5–20 mg daily in divided doses), indoramin

(25–100 mg 12-hourly) and doxazosin (1–16 mg daily), and drugs that act directly on

vascular smooth ms, such as hydralazine (25–100 mg 12-hourly) & minoxidil (10–50 mg

daily). Side-effects include first-dose and postural hypotension, headache, tachycardia &

fluid retention. Minoxidil also causes increased facial hair and is therefore unsuitable for

female patients.

Choice of antihypertensive drug

The choice is initially dictated by the patient’s age & ethnic background, although cost

and convenience will affect the exact drug & preparation used. Response to initial

therapy & side-effects dictate subsequent treatment. Comorbid conditions also have an

influence on initial drug selection; for example, a β-blocker might be the most

appropriate treatment for a patient with angina. Thiazide diuretics and dihydropyridine

calcium channel antagonists are the most suitable drugs for the treatment of high BP in

older people. Although some patients can be satisfactorily treated with a single

antihypertensive drug, a combination of drugs is often required to achieve optimal BP

control as it produce fewer unwanted effects & Some drug combinations have

complementary or synergistic actions; for example, thiazides increase activity of the

renin–angiotensin system while ACE inhibitors block it.

Emergency treatment of accelerated phase or malignant hypertension

In this hypertension, lowering BP too quickly may compromise tissue perfusion (due to

altered autoregulation) and can cause cerebral damage, including occipital blindness, and

precipitate coronary or renal insufficiency. Even in the presence of cardiac failure or

hypertensive encephalopathy, a controlled reduction to a level of about 150/90 mmHg

over a period of 24–48 hours is ideal. In most patients, it is possible to avoid parenteral

therapy and bring BP under control with bed rest and oral drug therapy. Intravenous or

intramuscular labetalol (2 mg/min to a maximum of 200 mg), intravenous glyceryl

trinitrate (0.6–1.2 mg/hour), intramuscular hydralazine (5 or 10 mg aliquots repeated at

half-hourly intervals) and intravenous sodium nitroprusside (0.3–1.0 μg/kg body

weight/min) are all effective but require careful supervision, preferably in a high-

dependency unit.

Refractory hypertension

The common causes of treatment failure in hypertension are non-adherence to drug

therapy, inadequate therapy, and failure to recognise an underlying cause such as renal

artery stenosis or phaeochromocytoma; of these, the first is by far the most prevalent.

There is no easy solution to compliance problems but simple treatment regimens,

attempts to improve rapport with the patient and careful supervision may all help.

Chapter 5 – Cardiovascular disease

117

Adjuvant drug therapy

o

Aspirin.

Antiplatelet therapy is a powerful means of reducing CV risk but may cause

bleeding, particularly intracerebral haemorrhage, in a small number of patients. The

benefits are thought to outweigh the risks in hypertensive patients aged 50 or over who

have well-controlled BP and either target organ damage, diabetes or a 10-year CHD risk

of ≥ 15% (or 10-year CVD risk of ≥ 20%).

o

Statins.

Treating hyperlipidaemia can produce a substantial reduction in CV risk. These

drugs are strongly indicated in patients who have established vascular disease, or

hypertension with a high (≥ 20% in 10 yrs) risk of developing CVD.