Pediatrics Lec 7 Dr. Ziyad

1

Fluid requirement

Fluid needs vary according to the gestational age, environmental condition, and

disease states.

Assuming minimal water loss in the stool of infant not receiving oral fluids, their

water need are equal to insensible water loss, excretion of renal solutes,

growth and any unusual water losses.

Insensible water loss are indirectly related to gestational age; very immature

preterm infant (<1000 g) may lose as much as 2-3 mL/kg/hr, partly because of

immature skin, lack of subcutaneous tissue, and a large exposed surface area.

Larger premature infants (2,000-2,500 g) nursed in an incubator may have an

insensible water loss of approximately 0.6-0.7 mL/kg/hr.

Insensible water loss is increased under radiant warmers, during phototherapy,

and in febrile infants. It is diminished when infants are clothed, breathe

humidified air, or are of advanced postnatal age.

Neoborn infants, especially those with VLBW, are also less able to concentrate

urine; their fluid intake required to excrete solutes increases.

Water intake in term infants is usually begun at 60-70 mL/kg on day 1 and

increased to 100-120 mL/kg by days 2-3.

Smaller, more premature infants may need to start with 70-80 mL/kg on day 1

and advance gradually to 150 mL/kg/day.

Daily weights, urine, and serum urea nitrogen and sodium levels should be

monitored carefully to determine water balance and fluid needs.

Clinical observation and physical examination are poor indicators of the state of

hydration of premature infants.

Conditions that increase fluid loss, such as glycosuria, the polyuric phase of

acute tubular necrosis, and diarrhea may lead to severe dehydration.

Alternatively, fluid overload may lead to edema, heart failure, patent ductus

arteriosus, and bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

Pediatrics Lec 7 Dr. Ziyad

2

Total Parenteral Nutrition:

Total intravenous alimentation may provide sufficient fluid, calories, amino

acids, electrolytes, and vitamins to sustain the growth of LBW infants before

complete enteral feeding has been established or when enteral feeding is

impossible for prolonged periods. Complications of intravenous alimentation

are related to both the catheter and metabolism of the infusate:

Coagulase-negative staphylococcus sepsis is the most important problem of

central vein infusions. Treatment includes appropriate antibiotics. If an infection

persists the line must be removed.

Thrombosis, extravasation of fluid, and accidental dislodgment of catheters

have also occurred.

Phlebitis, cutaneous sloughing, and superficial infection may occur.

Metabolic complications of parenteral nutrition include hyperglycemia, which

may lead to osmotic diuresis and dehydration; azotemia; hypoglycemia from

sudden accidental cessation of the infusate ; hyperlipidemia and

hyperammonemia. Metabolic bone disease and/or cholestatic jaundice and liver

disease may develop in infants who require long-term parenteral nutrition.

Feeding:

The process of oral alimentation requires, in addition to a strong sucking effort,

coordination of swallowing, epiglottal and uvular closure of the larynx and nasal

passages, and normal esophageal motility, a synchronized process that is usually

absent before 34 wk of gestation.

Oral feeding (nipple) should not be initiated or should be discontinued in infants

with respiratory distress, hypoxia, circulatory insufficiency, excessive

secretions, gagging, sepsis, central nervous system depression, severe

immaturity, or signs of serious illness.

These high-risk infants require parenteral nutrition or gavage feeding to supply

calories, fluid, and electrolytes.

Pediatrics Lec 7 Dr. Ziyad

3

Preterm infants at 34 week of gestation or more can often be fed by bottle or at

the breast. Smaller or less vigorous infants should be fed by gavage. The tube is

passed through the nose until approximately 2.5 cm (1 inch) of the lower end is

in the stomach; a measured amount of fluid is given by pump or by gravity.

Such tubes may be left in place for 3-7 days before being replaced by a similar

tube through the alternate nostril. The LBW infant may be fed with intermittent

bolus feeding or continuous feeding.

A change to breast or bottle-feeding may be instituted gradually as soon as

infant displays general vigor adequate for oral feeding

For infants under 1000 g the initial feedings are either breast milk or preterm

formula at 10 mL/kg/24 hr as a continuous nasogastric tube drip (or given by

intermittent gavage every 2-3 hr.)

if the initial feeding is tolerated, the volume is increased by 10 – 15 ml/ kg/24

hr. Once a volume of 150 ml/kg/24 hr achieved, the caloric content may be

increase to 24 or 27 kcal/oz.

Intravenous fluids are needed until feedings provide approximately 120

mL/kg/24. the feeding protocol for premature infants weighing over 1,500g is

initiated at a volume of 20-25 mL/kg/24 hr of full-strength breast milk or

preterm formula given as a bolus every 3 hr. thereafter increments in total daily

formula volume should not exceed 20 ml/kg/24 hr.

Prevention of Infection:

Premature infants have an increased susceptibility to infection, and thus meticulous

attention to infection control is required. Prevention strategies include:

1. Strict compliance with hand washing and universal precautions.

2. Limiting nurse-to patient ratios and avoiding crowding.

3. Minimizing the risk of catheter contamination, meticulous skin care

4. Encouraging early appropriate advancement of enteral feeding.

5. Education and feedback to staff.

6. Surveillance of nosocomial infection rates in the nursery.

Pediatrics Lec 7 Dr. Ziyad

4

PROGNOSIS:

Infants born weighing 1,501-2,500 g have a 95% or greater chance of survival,

but those weighing less still have significantly higher mortality.

Intensive care has extended the period during which a VLBW infant is at

increased risk of dying of complications of prematurity, such as

bronchopulmonary dysplasia, necrotizing enterocolitis, or nosocomial infection.

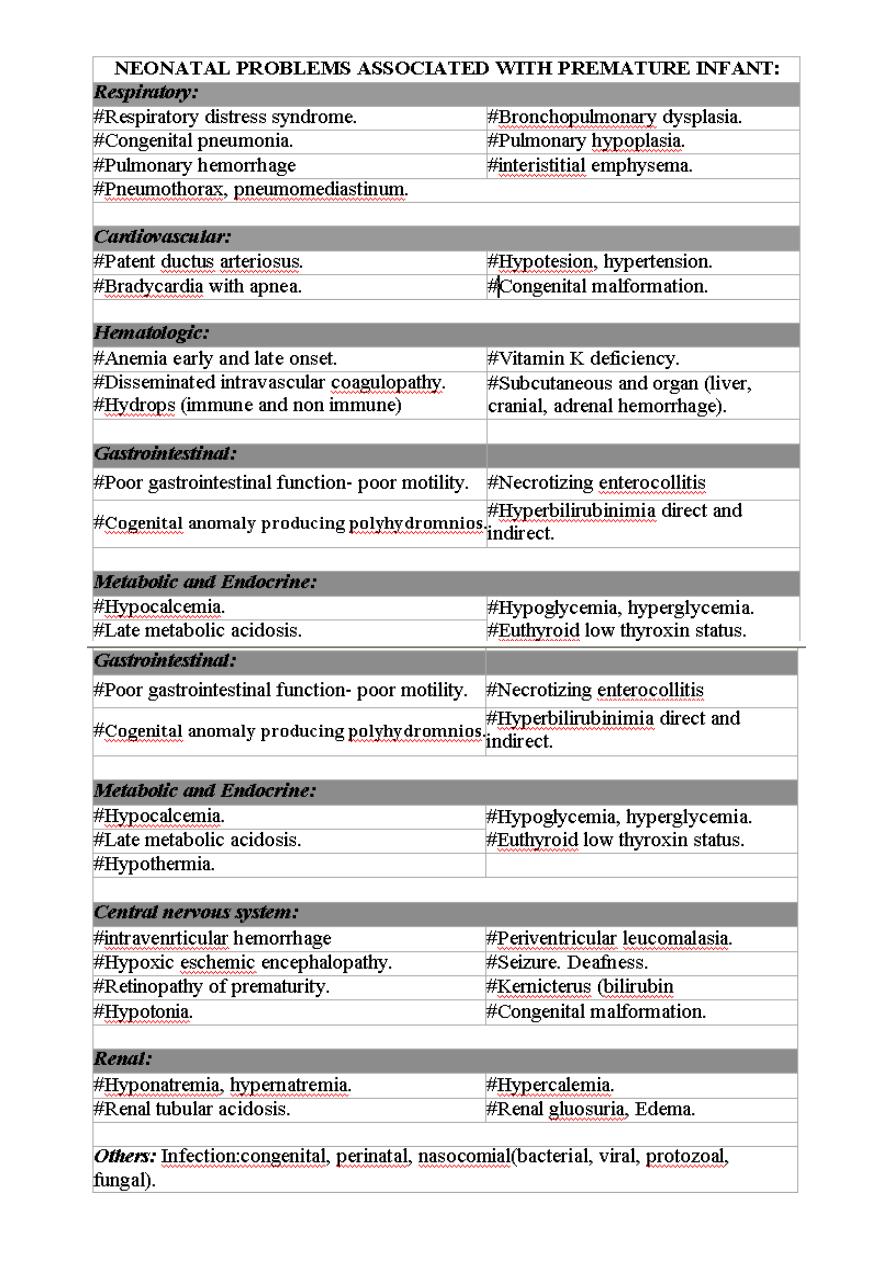

SEQUELAE OF LOW BIRTH WEIGHT

IMMEDIATE

Hypoxia, ischemia

Intraventricutlar hemorrhage Sensorineural injury

Respiratory failure

Necrotizing enterocolitis.

Cholestatic liver disease.

Nutrient deficiency

Social stress

.

Other

LATE

Mental retardation, spastic diplegia, mictocephaly, seizure, poor school

performance, spasticity, hydrocephalus

Hearing, visual impairment, retinopathy of prematurity myopia

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia, core pulmonale, bronchospasim

Short bowel syndrome, malabsorbtion, malnutrition

Cirrhosis, hepatic failure, hepatic carcinoma Growth, failure, osteopenia,

anemia,Child abuse or neglect, failure to thrive

Sudden infant death syndrome, infection, inguinal hernia

Pediatrics Lec 7 Dr. Ziyad

5