1

Interstitial and Infiltrative Pulmonary Diseases

Diffuse parenchymal lung disease

The diffuse parenchymal lung diseases (DPLDs) are a heterogeneous group of conditions

associated with diffuse thickening of the alveolar walls with:

1. Inflammatory cells and exudates (e.g. the acute respiratory distress syndrome-

ARDS),

2. Granulomas (e.g. sarcoidosis),

3. Alveolar haemorrhage (e.g. Goodpasture's syndrome,)

4. And/or fibrosis (e.g. fibrosing alveolitis).

Diagnosis of interstitial lung disease:

1-A general approach:

Establishing a diagnosis is important because:

•

Firstly

, there are prognostic implications; for example, sarcoidosis is frequently

self-limiting, whereas idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is most often fatal.

•

Secondly

, establishing a specific diagnosis will avoid inappropriate treatment; for

example, the powerful immunosuppressive regimens used for some cases of IPF

would be undesirable if the underlying condition was asbestosis or hypersensitivity

pneumonitis.

•

Thirdly

, some DPLDs can be expected to respond better than others to

treatment, e.g. a good symptomatic response to corticosteroids could be predicted

in sarcoidosis, whereas the prognosis would need to be more guarded in IPF.

•

Finally

, a lung biopsy taken when the patient is already established on empirical

immunosuppressive therapy is not only associated with a higher morbidity and

mortality, but the interpretation of the tissue obtained is more difficult.

•

It is desirable, therefore, to be confident about the diagnosis before starting any

therapy.

The smoking status should be recorded and a drug history that includes over-the-

counter prescriptions should be obtained.

2

A history of rashes

, joint pains or renal disease may suggest an underlying connective

tissue disorder or vasculities.

The presence of any comorbid disease should be ascertained such as collagen vascular

disease, immunodeficiency, HIV or malignancy.

In exceptional cases there is a family history of DPLD.

2-Physical signs

In many cases, especially in early disease, there are few, if any, physical signs.

In

advanced disease, tachypnoea and cyanosis may be evident at rest and there may be

signs of pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure.

Finger clubbing may be prominent,

particularly in IPF or asbestosis

. There may be

restriction of lung expansion and showers of end-inspiratory crackles posteriorly and

laterally.

Extrapulmonary signs, including lymphadenopathy or uveitis, may be present in

sarcoidosis and

arthropathies or rashes may occur when a DPLD is a manifestation of a

connective tissue disorder.

Conditions Which Mimic Interstitial Lung Diseases

1-Infection

•

Viral pneumonia

•

Pneumocystis jirovecii

•

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

•

TB

•

Parasites, e.g. filariasis

•

Fungal infection

2-Malignancy

•

Leukaemia and lymphoma

•

Lymphatic carcinomatosis

•

Multiple metastases

•

Bronchoalveolar carcinoma

3

3-Pulmonary oedema

4-Aspiration pneumonitis

Investigations

Laboratory investigations:

•

Full blood count-lymphopenia in sarcoid; eosinophilia in pulmonary eosinophilias and

drug reactions; neutrophilia in hypersensitivity pneumonitis

•

Ca2-+may be elevated in sarcoid

•

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)-may provide non-specific indicator of disease

activity in DPLD

•

Serum ACE-non-specific indicator of disease activity in sarcoid

•

ESR and CRP may be non-specifically raised

•

Autoimmune screen and rheumatoid factor may suggest collagen vascular disease

Radiology:

Chest X-ray,High-resolution CT scan

Pulmonary function:

Spirometry, lung volumes, gas transfer, exercise tests Pulmonary

function tests typically show a restrictive pattern with diminished lung volumes and a

reduced gas transfer, although an elevated gas transfer may be seen in cases of alveolar

haemorrhage.

Bronchoscopy

•

Bronchoalveolar lavage-infection, differential cell counts

•

Bronchial biopsy may be useful in sarcoid

Lung biopsy (in selected cases)

•

Transbronchial biopsy useful in sarcoid and differential of malignancy or infection

•

Video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS)

Others

•

Liver biopsy

•

Urinary calcium excretion may be useful in sarcoid

4

Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias

The idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs) are

characterised by varying patterns of

inflammation and fibrosis in the lung parenchyma

, and comprise a number of

clinicopathological entities that are sufficiently different from one another to be

considered as separate diseases.

The most common and important of these is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF),

which

accounts for over 85% of new cases.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

•

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis refers to a

specific form of DPLD characterised by

pathological (or HRCT) evidence of 'usual interstitial pneumonia' (UIP).

•

The histological features are suggestive of repeated episodes of focal damage to the

alveolar epithelium consistent with an autoimmune process, but the

aetiology

remains

elusive; putative factors include viruses (e.g. Epstein-Barr virus), occupational dusts

(metal or wood), drugs (antidepressants) or chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux.

•

Familial cases are rare but genetic factors that control the inflammatory and fibrotic

response are likely to be important.

•

There is a strong association with cigarette smoking.

Clinical features

•

IPF is uncommon before the age of 50 years. It usually presents with

insidiously

progressive breathlessness and a non-productive cough.

•

Constitutional symptoms are unusual. Clinical findings include

finger clubbing and the

presence of bi-basal fine late inspiratory crackles.

•

The natural history is usually one of steady decline, but some patients are prone to

exacerbations which are accompanied by an acute deterioration in breathlessness,

disturbed gas exchange, and new

ground glass changes or consolidation on HRCT.

•

In advanced disease

, central cyanosis is detectable and patients may develop features

of right heart failure.

•

There is no circulating marker for IPF.

5

•

Non-specific findings include hypergammaglobulinaemia, positive rheumatoid factor or

antinuclear factor, and an elevated LDH which may reflect active pneumonitis.

Investigations:

•

Pulmonary function tests classically show a restrictive defect with reduced lung

volumes and gas transfer.

•

However, lung volumes may be paradoxically preserved in patients with concomitant

emphysema.

•

Dynamic tests are useful to document exercise tolerance and demonstrate exercise-

induced arterial hypoxaemia, but as IPF advances, arterial hypoxaemia and hypocapnia

are present at rest.

•

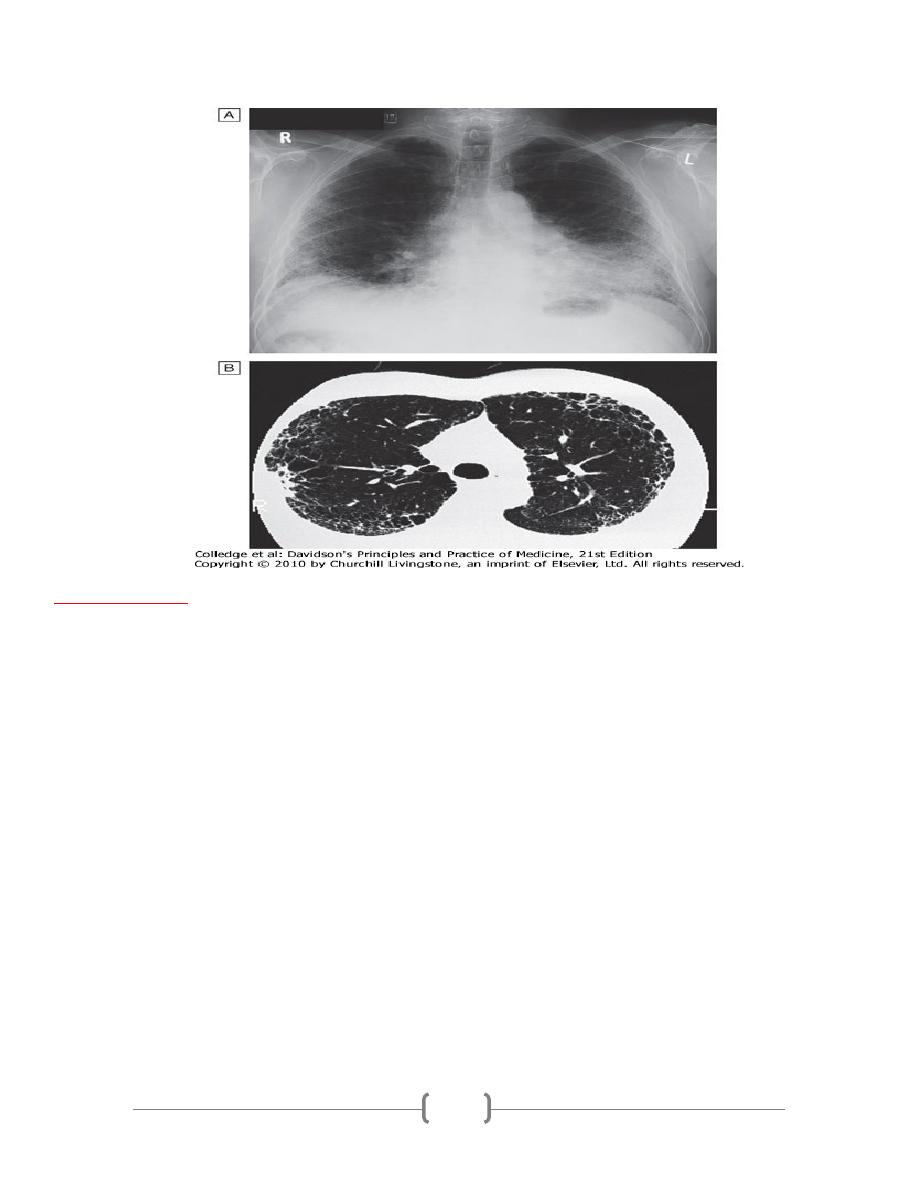

Virtually all patients have an abnormal chest X-ray at presentation with lower zone bi-

basal reticular and reticulonodular opacities.

•

A 'honeycomb' appearance may be seen in advanced disease but is non-specific.

•

HRCT typically demonstrates a patchy, predominantly peripheral, subpleural and basal

reticular pattern with subpleural cysts (honeycombing) and/or traction bronchiectasis.

•

A lung biopsy is not usually required in those with typical clinical features and HRCT

appearances, particularly if other known causes of interstitial lung disease have been

excluded, but should be considered in cases of diagnostic uncertainty or with atypical

features.

6

Management

Treatment is challenging. Prednisolone therapy (0.5 mg/kg) combined with azathioprine

(2-3 mg/kg) is advocated for patients who are:

1. highly symptomatic or

2. have rapidly progressive disease,

3. have a predominantly 'ground glass' appearance on CT or

4. a sustained fall of > 15% in their FVC or gas transfer over a 3-6-month period.

•

However, response rates are notoriously poor, side-effects are guaranteed.

•

If objective evidence of improvement can be demonstrated, the prednisolone

dose may be gradually reduced to a maintenance dose of 10-12.5 mg daily.

•

The potential of therapies such as warfarin, N-acetylcysteine, IFN-γ1b, bosentan

is being explored but cannot be recommended outside clinical trials at present.

•

Lung transplantation should be considered in young patients with advanced disease.

•

Oxygen may be provided for palliation of breathlessness but opiates may be

required for relief of severe dyspnoea.

•

The optimum treatment for acute exacerbations is unknown.

7

Prognosis

•

A median survival of 3 years is widely quoted; however, the rate of disease

progression varies considerably from death within a few months to survival with

minimal symptoms for many years.

•

Serial lung function testing may provide useful prognostic information, with

relative preservation of lung function

suggesting longer survival and desaturation

on exercise heralding a poorer prognosis.

•

The finding of high numbers of fibroblastic foci on biopsy suggests a more rapid

deterioration.

•

IPF is associated with

an increased risk of carcinoma of the lung.

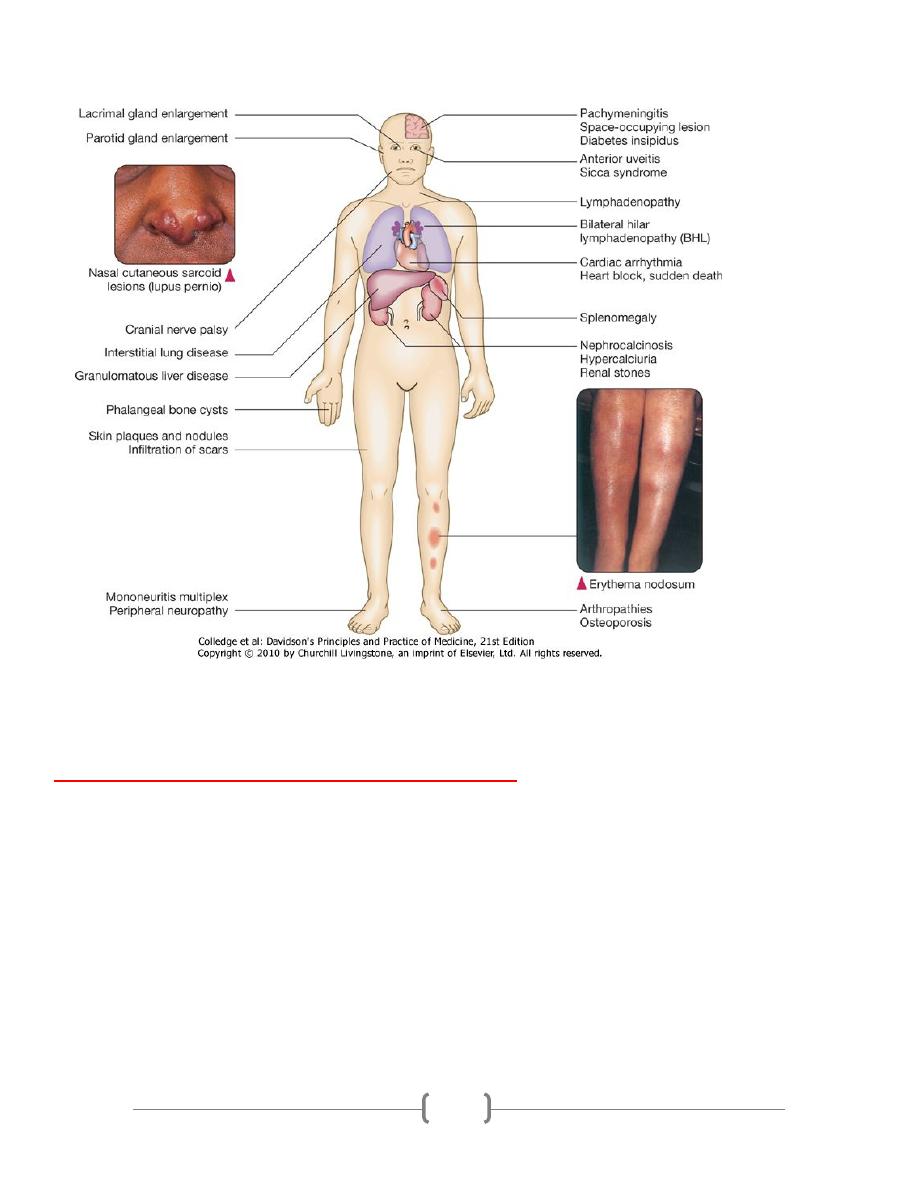

Sarcoidosis

•

Sarcoidosis

is a multisystem granulomatous disorder of unknown aetiology that is

characterised by the presence of non-caseating granulomas.

•

The condition is more frequently described in colder parts of northern Europe.

•

It also appears to be more common and more severe in those from a West Indian or

Asian background; Eskimos, Arabs and Chinese are rarely affected.

•

The tendency for sarcoid to present in the spring and summer has led to speculation

as to the role of infective agents, including mycobacteria, propionibacteria and

viruses, but the cause remains elusive.

•

Genetic susceptibility

is supported by familial clustering; a range of

class II HLA

alleles confer protection from or susceptibility to the condition.

•

Sarcoidosis occurs less frequently in

smokers.

Clinical features

•

Sarcoidosis is considered with other DPLD as over 90% of cases affect the lungs, but

the condition can affect almost any organ.

•

Löfgren's syndrome

-an acute illness characterised by erythema nodosum, peripheral

arthropathy, uveitis, bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (BHL), lethargy and occasionally

fever-is often seen in young adults.

8

•

Alternatively, BHL may be detected in an otherwise asymptomatic individual

undergoing a chest X-ray for other purposes.

•

Pulmonary disease may also present in a more insidious manner with cough, exertional

breathlessness and radiographic infiltrates; chest auscultation is often surprisingly

unremarkable.

•

Fibrosis occurs in around

20% of cases

of pulmonary sarcoidosis and may cause

a silent

loss of lung function.

•

Pleural disease is uncommon and finger clubbing is not a feature

.

•

Complications such as bronchiectasis, aspergilloma, pneumothorax, pulmonary

hypertension and cor pulmonale have been reported but are rare.

Presentation of sarcoidosis

•

Asymptomatic: abnormal routine chest X-ray ( 30%) or abnormal liver function tests

•

Respiratory and constitutional symptoms (20-30%)

•

Erythema nodosum and arthralgia (20-30%)

•

Ocular symptoms (5-10%)

•

Skin sarcoid (including lupus pernio) (5%)

•

Superficial lymphadenopathy (5%)

•

Other (1%), e.g. hypercalcaemia, diabetes insipidus, cranial nerve palsies, cardiac

arrhythmias, nephrocalcinosis

9

Chest X-ray changes in sarcoidosis

Stage I:

BHL (usually symmetrical); paratracheal nodes often enlarged

Often asymptomatic, but may be associated with erythema nodosum and

arthralgia. The majority of cases resolve spontaneously within 1 year

Stage II:

BHL and parenchymal infiltrates

Patients may present with breathlessness or

cough. The majority of cases resolve spontaneously

Stage III:

parenchymal infiltrates without BHL

Disease less likely to resolve spontaneously

Stage IV:

10

pulmonary fibrosis

Can cause progression to ventilatory failure, pulmonary

hypertension and cor pulmonale

Investigations

•

Lymphopenia is characteristic and liver function tests may be mildly deranged

.

Hypercalcaemia may be present (reflecting increased formation of calcitriol-1,25-

dihydroxyvitamin D

3

-by alveolar macrophages), particularly if the patient has been

exposed to strong sunlight.

•

Hypercalciuria

may also be seen and may lead to nephrocalcinosis.

•

Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme

(ACE)

is a non-specific marker of disease

activity and can assist in monitoring the clinical course.

•

Chest radiography

has been used to stage sarcoid.

•

In patients with pulmonary infiltrates,

pulmonary function testing

may show a

restrictive defect accompanied by

impaired gas exchange

.

•

Exercise tests may reveal oxygen desaturation.

•

Transbronchial (and bronchial) biopsies

show non-caseating granulomas

and the

mucosa may have a 'cobblestone' appearance at bronchoscopy.

•

The BAL fluid typically contains an increased CD4:CD8 T-cell ratio.

•

Characteristic HRCT appearances include reticulonodular opacities.

•

The occurrence of erythema nodosum with BHL on chest X-ray is often

sufficient for a confident diagnosis, without recourse to a tissue biopsy.

•

Similarly, a typical presentation with classical HRCT features may also be

accepted.

•

However, in other instances the diagnosis should be confirmed by histological

examination of the involved organ.

•

The presence of anergy (e.g. to tuberculin skin tests) may support the diagnosis.

11

Management

•

Patients who present with acute illness and erythema nodosum should receive

NSAIDs and, if symptoms are severe, a short course of corticosteroids.

•

The majority of patients enjoy

spontaneous remission

and so if there is no

evidence of organ damage, systemic corticosteroid therapy can be withheld for 6

months.

•

However, prednisolone

(at a starting dose of 20-40 mg/day) should be commenced

immediately in the presence of hypercalcaemia, pulmonary impairment, renal

impairment and uveitis

.

•

Topical steroids may be useful in cases of mild uveitis, and inhaled corticosteroids

have been used to shorten the duration of systemic corticosteroid use in

asymptomatic parenchymal sarcoid.

•

Patients should be warned that strong sunlight may precipitate hypercalcaemia and

endanger renal function.

Features suggesting a less favourable outlook include:

1. Age> 40 years,

2. Afro-Caribbean ethnicity,

3. Persistent symptoms for more than 6 months,

4. the involvement of more than three organs,

5. lupus pernio

6. And a stage III/IV chest X-ray.

•

In patients with severe disease methotrexate (10-20 mg/week), azathioprine

(50-150 mg/day) and specific TNF-α inhibitors have been effective.

•

Chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine and low-dose thalidomide may be useful in

cutaneous sarcoid with limited pulmonary involvement.

•

Selected patients may be referred for consideration of single lung

transplantation.

•

The overall mortality is low (1-5%) and usually reflects cardiac involvement or

pulmonary fibrosis.