Respiratory System

Dr.M.Ali

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

COPD is defined as a preventable and treatable lung disease with some significant

extrapulmonary effects that may contribute to the severity in individual patients.

The pulmonary component is characterised by airflow limitation that is not

fully reversible. The airflow limitation is usually progressive and associated with

an abnormal inflammatory response of the lung to noxious particles or

gases.Related diagnoses include chronic bronchitis (cough and sputum on most

days for at least 3 consecutive months for at least 2 successive years) and

emphysema (abnormal permanent enlargement of the airspaces distal to the

terminal bronchioles, accompanied by destruction of their walls and without

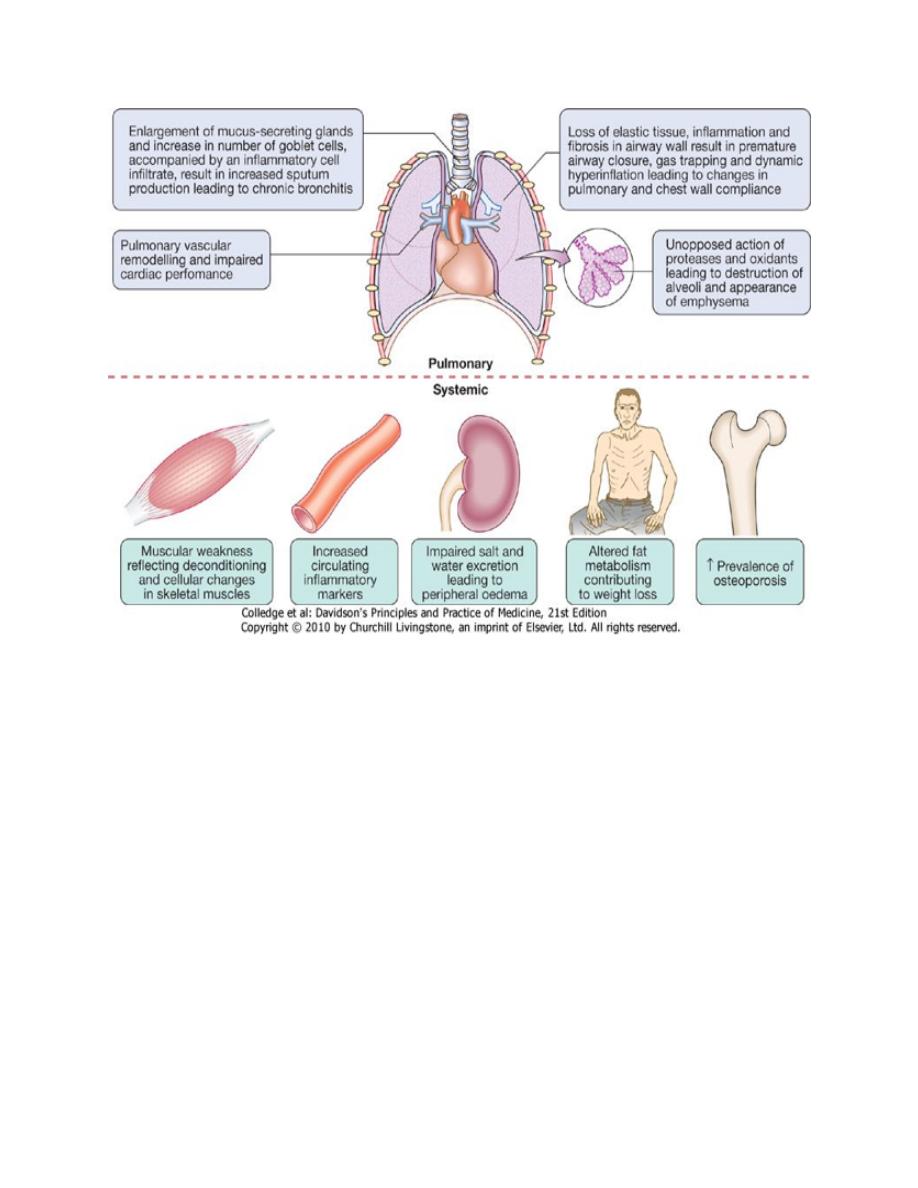

obvious fibrosis). Extrapulmonary manifestations include impaired nutrition,

weight loss and skeletal muscle dysfunction .

Epidemiology

Prevalence is directly related to the prevalence of tobacco smoking and, in low-

and middle-income countries, the use of biomass fuels. Current estimates suggest

that 80 million people world-wide suffer from moderate to severe disease.In 2005,

COPD contributed to more than 3 million deaths (5% of deaths globally), but by

2020 it is forecast to represent the third most important cause of death world-

wide.The anticipated rise in morbidity and mortality from COPD will be greatest in

Asian and African countries as a result of their increasing tobacco consumption.

Aetiology

Cigarette smoking represents the most significant risk factor for COPD and relates

to both the amount and the duration of smoking.It is unusual to develop COPD

with less than 10 pack years (1 pack year = 20 cigarettes/day/year) and not all

smokers develop the condition, suggesting that individual susceptibility factors are

important.

Respiratory System

Dr.M.Ali

Risk factors for development of COPD

a- Exposures

• Tobacco smoke: accounts for 95% of cases in UK

• Biomass solid fuel fires: wood, animal dung, crop residues and coal lead to

high levels of indoor air pollution

• Occupation: coal miners and those who work with cadmium

• Outdoor and indoor air pollution

• Low birth weight: may reduce maximally attained lung function in young

adult life

• Lung growth: childhood infections or maternal smoking may affect growth

of lung during childhood, resulting in a lower maximally attained lung

function in adult life

• Infections: recurrent infection may accelerate decline in FEV

1

; persistence of

adenovirus in lung tissue may alter local inflammatory response

predisposing to lung damage; HIV infection is associated with emphysema

• Low socioeconomic status

• Nutrition: role as independent risk factor unclear

• Cannabis smoking

b-Host factors

• Genetic factors: α

1

-antiproteinase deficiency; other COPD susceptibility

genes are likely to be identified

• Airway hyper-reactivity

Respiratory System

Dr.M.Ali

Pathophysiology

COPD has both pulmonary and systemic components. The changes in pulmonary

and chest wall compliance mean that collapse of intrathoracic airways during

expiration is exacerbated, during exercise as the time available for expiration

shortens, resulting in dynamic hyperinflation. Increased V/Q mismatch increases

the dead space volume and wasted ventilation. Flattening of the diaphragmatic

muscles and an increasingly horizontal alignment of the intercostal muscles place

the respiratory muscles at a mechanical disadvantage. The work of breathing is

therefore markedly increased, first on exercise but, as the disease advances, at rest

too. Emphysema may be classified by the pattern of the enlarged airspaces:

centriacinar, panacinar and periacinar. Bullae form in some individuals. This

results in impaired gas exchange and respiratory failure.

Clinical features

COPD should be suspected in any patient over the age of 40 years who presents

with symptoms of chronic bronchitis and/or breathlessness. Depending on the

presentation, important differential diagnoses include chronic asthma, tuberculosis,

bronchiectasis and congestive cardiac failure.Cough and associated sputum

production are usually the first symptoms, often referred to as a 'smoker's cough'.

Haemoptysis may complicate exacerbations of COPD but should not be attributed

to COPD without thorough investigation.Breathlessness usually brings about the

first presentation to medical attention.the modified Medical Research Council

(MRC) dyspnoea scale may also be useful. In advanced disease, enquiry should be

made as to the presence of oedema (which may be seen for the first time during an

exacerbation) and morning headaches, which may suggest hypercapnia.

Respiratory System

Dr.M.Ali

Modified MRC dyspnoea scale

Grad

e

Degree of breathlessness related to activities

0

No breathlessness except with strenuous exercise

1

Breathlessness when hurrying on the level or walking up a slight hill

2

Walks slower than contemporaries on level ground because of breathlessness or has to stop for breath when walking at

own pace

3

Stops for breath after walking about 100 m or after a few minutes on level ground

4

Too breathless to leave the house, or breathless when dressing or undressing

Physical signs are non-specific, correlate poorly with lung function, and are

seldom obvious until the disease is advanced. Breath sounds are typically quiet;

crackles may accompany infection but if persistent raise the possibility of

bronchiectasis.Finger clubbing is not a feature of COPD and should trigger further

investigation for lung cancer, bronchiectasis or fibrosis. The presence of pitting

oedema should be documented but the frequently used term 'cor pulmonale' is

actually a misnomer, as the right heart seldom 'fails' in COPD and the occurrence

of oedema usually relates to failure of salt and water excretion by the hypoxic,

hypercapnic kidney.The body mass index (BMI) is of prognostic significance and

should be recorded. Two classical phenotypes have been described: 'pink puffers'

and 'blue bloaters'. The former('pink puffers) are typically thin and breathless,

and maintain a normal PaCO

2

until the late stage of disease. The latter ('blue

bloaters')develop (or tolerate) hypercapnia earlier and may develop oedema and

secondary polycythaemia. In practice, these phenotypes often overlap.

Respiratory System

Dr.M.Ali

Investigations

Although there are no reliable radiographic signs that correlate with the severity of

airflow limitation, a chest X-ray is essential to identify alternative diagnoses such

as cardiac failure, other complications of smoking such as lung cancer, and the

presence of bullae.

A full blood count is useful to exclude anaemia or document polycythaemia, and

in younger patients with predominantly basal emphysema, α

1

-antiproteinase

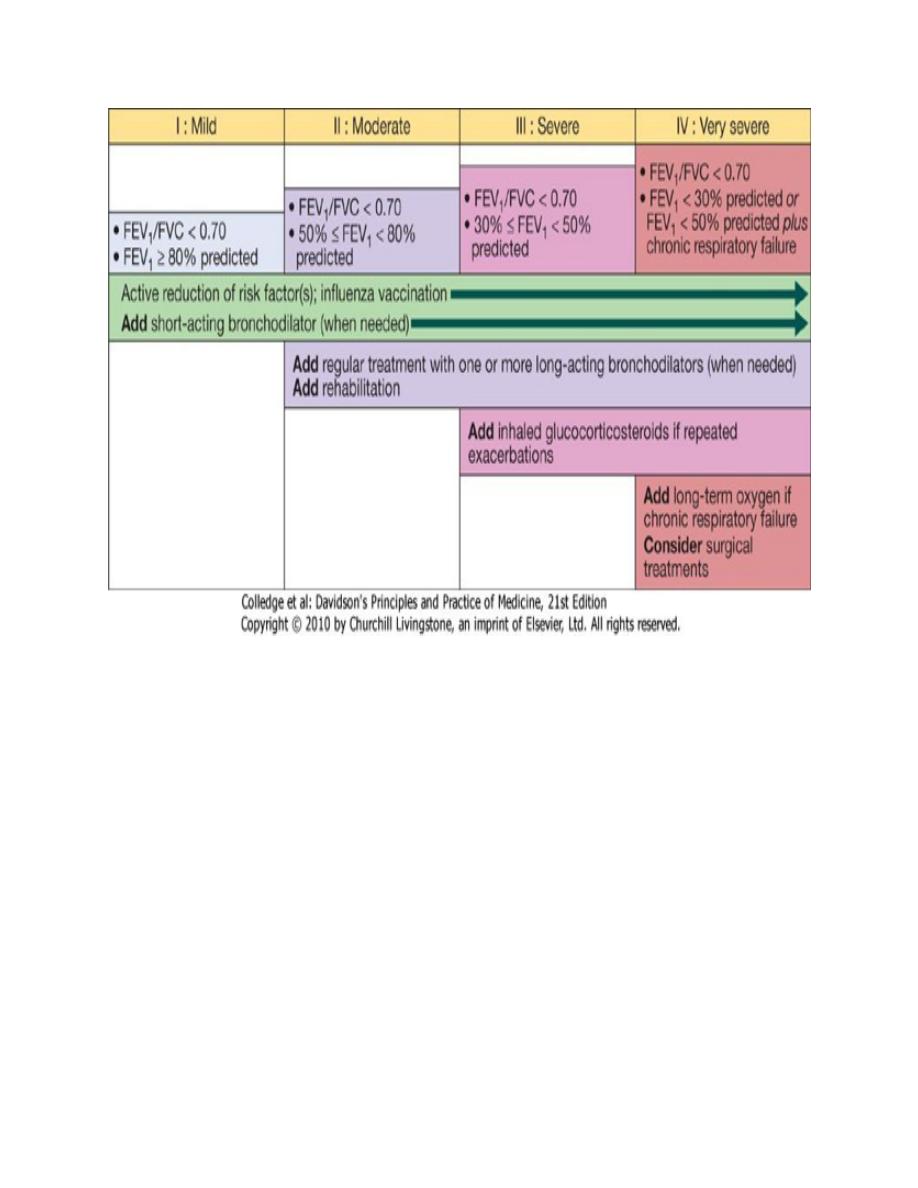

should be assayed. The diagnosis requires objective demonstration of airflow

obstruction by spirometry and is established when the post-bronchodilator

FEV

1

is less than 80% of the predicted value and accompanied by FEV

1

/FVC

< 70%. An FEV

1

/FVC < 70% with an FEV

1

of 80% or more suggests the presence

of mild disease, although this may be a normal finding in older patients. The

severity of COPD may be defined according to the post-bronchodilator FEV

1

as a

percentage of the predicted value for the patient's age . A low peak flow is

Respiratory System

Dr.M.Ali

consistent with COPD but is non-specific, does not discriminate between

obstructive and restrictive disorders, and may underestimate the severity of airflow

limitation.

Spirometric classification of COPD severity based on post-bronchodilator

FEV1

Stag

e

Severity

FEV

1

I

Mild

FEV

1

/FVC < 0.70

FEV

1

≥80% predicted

II

Moderate

FEV

1

/FVC < 0.70

50% ≤ FEV

1

< 80% predicted(50%-80%)

III

Severe

FEV

1

/FVC < 0.70

30% ≤ FEV

1

< 50% predicted(30%-50%)

IV

Very severe

FEV

1

/FVC < 0.70

FEV

1

< 30% predicted or FEV

1

< 50% predicted plus chronic

respiratory failure

Measurement of lung volumes provides an assessment of hyperinflation. This is

generally performed using the helium dilution technique.The presence of

emphysema is suggested by a low gas transfer factor . Exercise tests provide an

objective assessment of exercise tolerance and a baseline on which to judge the

response to bronchodilator therapy or rehabilitation programmes; they may also be

valuable when assessing prognosis.

Pulse oximetry may prompt referral for a domiciliary oxygen assessment if less

than 93%.

Respiratory System

Dr.M.Ali

HRCT is likely to play an increasing role in the assessment of COPD, as it allows

the detection, characterisation and quantification of emphysema and is more

sensitive than a chest X-ray at detecting bullae.

Management

Smoking cessation:

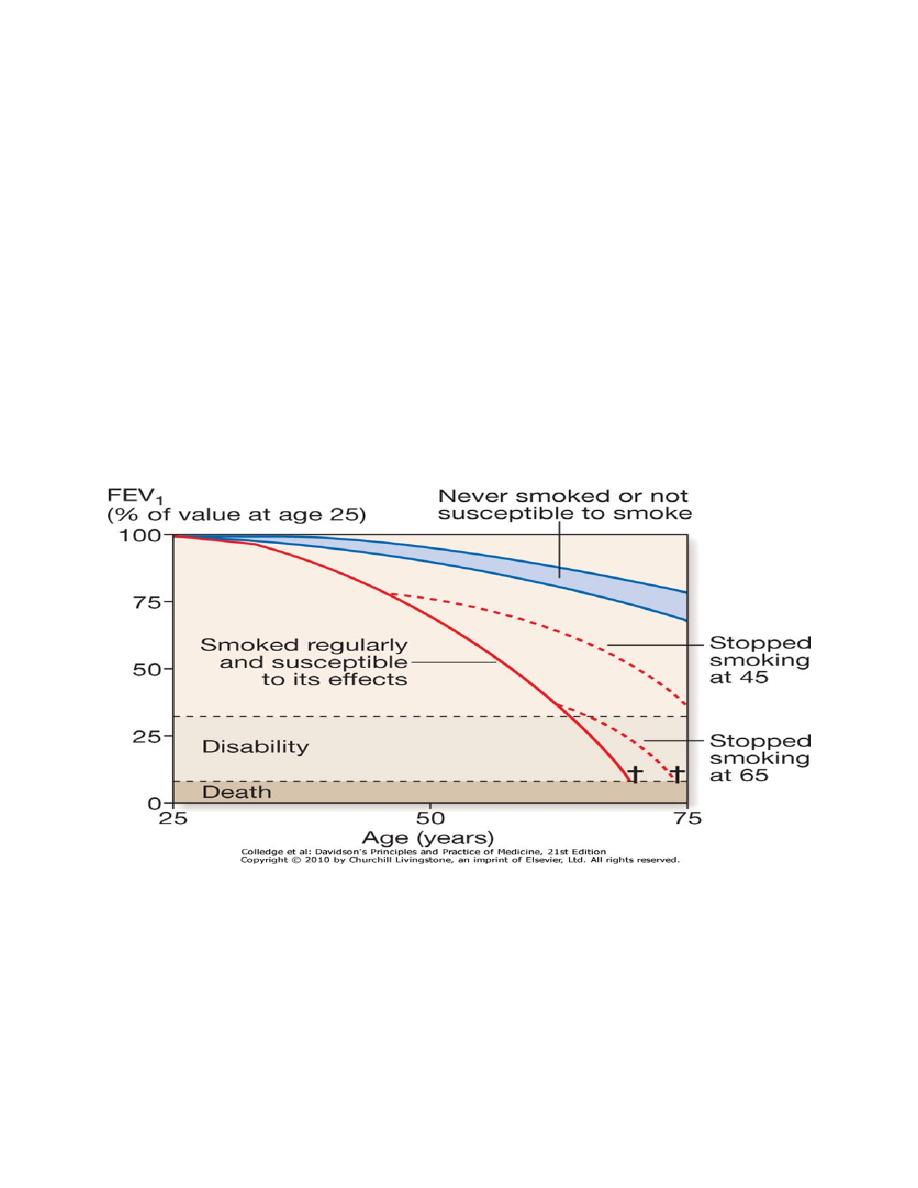

Every attempt should be made to highlight the role of smoking in the development

and progress of COPD, advising and assisting the patient toward smoking

cessation. On cessation patients should be warned to expect an apparent worsening

of chest symptoms and reassured that this is temporary.

Cessation is difficult but highly rewarding and remains the only intervention

proven to decelerate the decline in FEV1.

Smoking cessation and COPD 'Sustained smoking cessation in mild to moderate

COPD is accompanied by a reduced decline in FEV

1

compared to persistent

smokers.' Reducing the number of cigarettes smoked each day has little impact on

the course and prognosis of COPD, but complete cessation is accompanied by an

improvement in lung function and deceleration in the rate of FEV

1

decline.In

regions where the indoor burning of biomass fuels is important, the introduction of

non-smoking cooking devices or the use of alternative fuels should be encouraged.

Respiratory System

Dr.M.Ali

Bronchodilator therapy is central to the management of breathlessness.The

inhaled route is preferred and a number of different agents delivered by a variety of

devices are available. Short-acting bronchodilators, such as the β

2

-agonists

salbutamol and terbutaline, or the anticholinergic, ipratropium bromide, may be

used for patients with mild disease. Longer-acting bronchodilators, such as the β

2

-

agonists salmeterol and formoterol, or the anticholinergic tiotropium bromide, are

more appropriate for patients with moderate to severe disease.Significant

improvements in breathlessness may be reported despite minimal changes in FEV

1

,

probably reflecting improvements in lung emptying that reduce dynamic

hyperinflation and ease the work of breathing. Oral bronchodilator therapy may be

contemplated in patients who cannot use inhaled devices efficiently. Theophylline

preparations improve breathlessness and quality of life, but their use has been

limited

by

side-effects,

unpredictable

metabolism

and

drug

interactions.Bambuterol, a pro-drug of terbutaline, is used on occasion. Orally

active highly selective phosphodiesterase inhibitors are currently under

development.

Corticosteroids

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations;

they are currently recommended in patients with severe disease (FEV

1

< 50%) who

report two or more exacerbations requiring antibiotics or oral steroids per year.

Regular use is associated with a small improvement in FEV

1

, but they do not alter

the natural history of the FEV

1

decline. It is more usual to prescribe a fixed

combination of an ICS with a LABA.Oral corticosteroids are useful during

exacerbations but maintenance therapy contributes to osteoporosis and impaired

skeletal muscle function and should be avoided.

Respiratory System

Dr.M.Ali

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Exercise should be encouraged at all stages and patients should be reassured that

breathlessness, whilst distressing, is not dangerous. Multidisciplinary programmes

that incorporate physical training, disease education and nutritional counselling

reduce symptoms, improve health status and enhance confidence.

Oxygen therapy

Long-term domiciliary oxygen therapy (LTOT) 'Long-term home oxygen

therapy improves survival in selected patients with COPD complicated by severe

hypoxaemia (arterial PaO

2

less than 8.0 kPa (55 mmHg)).'

Prescription of long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) in COPD Arterial blood

gases measured in clinically stable patients on optimal medical therapy on at least

two occasions 3 weeks apart:

Respiratory System

Dr.M.Ali

1. PaO

2

< 7.3 kPa (55 mmHg) irrespective of PaCO

2

and FEV

1

< 1.5 L

2. PaO

2

7.3-8 kPa (55-60 mmHg) plus pulmonary hypertension, peripheral

oedema or nocturnal hypoxaemia

3. patient stopped smoking.

• Use at least 15 hours/day at 2-4 L/min to achieve a PaO

2

> 8 kPa (60

mmHg) without unacceptable rise in PaCO

2

.

• Surgical intervention:

Young patients in whom large bullae compress surrounding normal lung tissue,

who otherwise have minimal airflow limitation and a lack of generalised

emphysema, may be considered for bullectomy.Patients with predominantly upper

lobe emphysema, with preserved gas transference and no evidence of pulmonary

hypertension, may benefit from lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS), in which

peripheral emphysematous lung tissue is resected with the aim of reducing

hyperinflation and decreasing the work of breathing may lead to

improvements in FEV

1

, lung volumes, exercise tolerance and quality of life.

Both bullectomy and LVRS can be performed thorascopically, minimising

morbidity, and endoscopic techniques for lung volume reduction are also under

development. Lung transplantation may benefit carefully selected patients with

advanced disease but is limited by shortage of donor organs.

Other measures

Patients with COPD should be offered an annual influenza vaccination and, as

appropriate, pneumococcal vaccination. Obesity, poor nutrition, depression and

social isolation should be identified and, if possible, improved. Mucolytic therapy

such as acetylcysteine, or antioxidant agents are occasionally used but with limited

evidence.

Acute exacerbations of COPD

Acute exacerbations of COPD are characterised by an increase in symptoms and

deterioration in lung function and health status. They become more frequent as the

Respiratory System

Dr.M.Ali

disease progresses and are usually triggered by bacteria, viruses or a change in air

quality. They may be accompanied by the development of respiratory failure

and/or fluid retention and represent an important cause of death. Many patients can

be managed at home with the use of increased bronchodilator therapy, a short

course of oral corticosteroids, and if appropriate, antibiotics. The presence of

cyanosis, peripheral oedema or an alteration in consciousness should prompt

referral to hospital.In other patients, consideration of comorbidity and social

circumstances may influence decisions regarding hospital admission.

Management of Acute exacerbations of COPD

Oxygen therapy

In patients with an exacerbation of severe COPD, high concentrations of oxygen

may cause respiratory depression and worsening acidosis . Controlled oxygen at

24% or 28% should be used with the aim of maintaining a PaO

2

> 8 kPa (60 mmHg)

(or an SaO

2

> 90%) without worsening acidosis.

Bronchodilators

Nebulised short-acting β

2

-agonists combined with an anticholinergic agent (e.g.

salbutamol with ipratropium) should be administered. With careful supervision, it

is usually safe to drive nebulisers with oxygen, but if concern exists regarding

oxygen sensitivity, nebulisers may be driven by compressed air and supplemental

oxygen delivered by nasal cannula.

Corticosteroids:

Oral prednisolone reduces symptoms and improves lung function. Currently, doses

of 30 mg for 10 days are recommended but shorter courses may be acceptable.

Prophylaxis against osteoporosis should be considered in patients who receive

repeated courses of steroids .

Antibiotic therapy:

The role of bacteria in exacerbations remains controversial and there is little

evidence for the routine administration of antibiotics. They are currently

recommended for patients reporting an increase in sputum purulence, sputum

volume or breathlessness. In most cases, simple regimens are advised, such as an

Respiratory System

Dr.M.Ali

aminopenicillin or a macrolide. Co-amoxiclav is only required in regions where β-

lactamase-producing organisms are known to be common.

Non-invasive ventilation:

If, despite the above measures, the patient remains tachypnoeic and acidotic (H

+

≥

45/pH < 7.35), then NIV should be commenced .Several studies have demonstrated

its benefit. Mechanical ventilation may be contemplated in those with a reversible

cause for deterioration (e.g. pneumonia), or when no prior history of respiratory

failure has been noted.

Non-invasive ventilation in COPD exacerbations

'Non-invasive ventilation is safe and effective in patients with an acute

exacerbation of COPD complicated by mild to moderate respiratory acidosis and

should be considered early in the course of respiratory failure to reduce the need

for endotracheal intubation, treatment failure and mortality.‘

Additional therapy

Exacerbations may be accompanied by the development of peripheral oedema;

this usually responds to diuretics. There has been a vogue for using an infusion of

intravenous aminophylline but evidence for benefit is limited and there are risks of

inducing arrhythmias and drug interactions. The use of the respiratory stimulant

doxapram has been largely superseded by the development of NIV, but it may be

useful for a limited period in selected patients with a low respiratory rate.

Prognosis

COPD has a variable natural history but is usually progressive. The prognosis is

inversely related to age and directly related to the post-bronchodilator FEV

1

.

Additional poor prognostic indicators include weight loss and pulmonary

hypertension. A recent study has suggested that a composite score (BODE index)

comprising the body mass index (B), the degree of airflow obstruction (O), a

measurement of dyspnoea (D) and exercise capacity (E), may assist in predicting

death from respiratory and other causes . Respiratory failure, cardiac disease and

lung cancer represent common modes of death.

Respiratory System

Dr.M.Ali

Calculation of the BODE index

Points on BODE index

Variable

0

1

2

3

FEV

1

≥ 65

50-64

36-49

≤ 35

Distance walked in

6 min (m)

≥ 350

250-349

150-249

≤ 149

MRC

dyspnoea

scale

0-1

2

3

4

Body mass index

> 21

≤ 21

A patient with a BODE score of 0-2 has a mortality rate of around 10% at 52 months,

whereas a patient with a BODE score of 7-10 has a mortality rate of around 80% at 52

months.

Discharge :

Discharge from hospital may be planned once the patient is clinically stable on his

or her usual maintenance medication. The provision of a nurse-led 'hospital at

home' team providing short-term nebuliser loan improves discharge rates and

provides additional support for the patient.