1 |

P a g e

PRESENTING PROBLEMS IN RESPIRATORY DISEASE:

Cough

:

Cough is the most frequent symptom of respiratory disease. It is caused by

stimulation of sensory nerves in the mucosa of the pharynx, larynx, trachea and

bronchi .

Acute sensitization of the normal cough reflex occurs in a number of

conditions, and it is typically induced by changes in air temperature or

exposure to irritants such as cigarette smoke or perfumes .

The explosive quality of a normal cough is lost in patients with respiratory

muscle paralysis or vocal cord palsy.

Paralysis of a single vocal cord gives rise to a prolonged, low-pitched,

inefficient 'bovine' cough accompanied by hoarseness .

Coexistence of an inspiratory noise (stridor) indicates partial obstruction of

a major airway (e.g. laryngeal oedema, tracheal tumor, scarring,

compression or inhaled foreign body) and requires urgent investigation

and treatment.

Sputum production is common in patients with acute or chronic cough,

and its nature and appearance can provide clues to the etiology

Causes of cough

Acute transient cough is most commonly caused by viral lower respiratory tract

infection, post-nasal drip resulting from rhinitis or sinusitis, aspiration of a

foreign body or throat-clearing secondary to laryngitis or pharyngitis.

When it occurs in the context of more serious diseases such as pneumonia,

aspiration, congestive heart failure or pulmonary embolism, it is usually easy to

diagnose from other clinical features .

2 |

P a g e

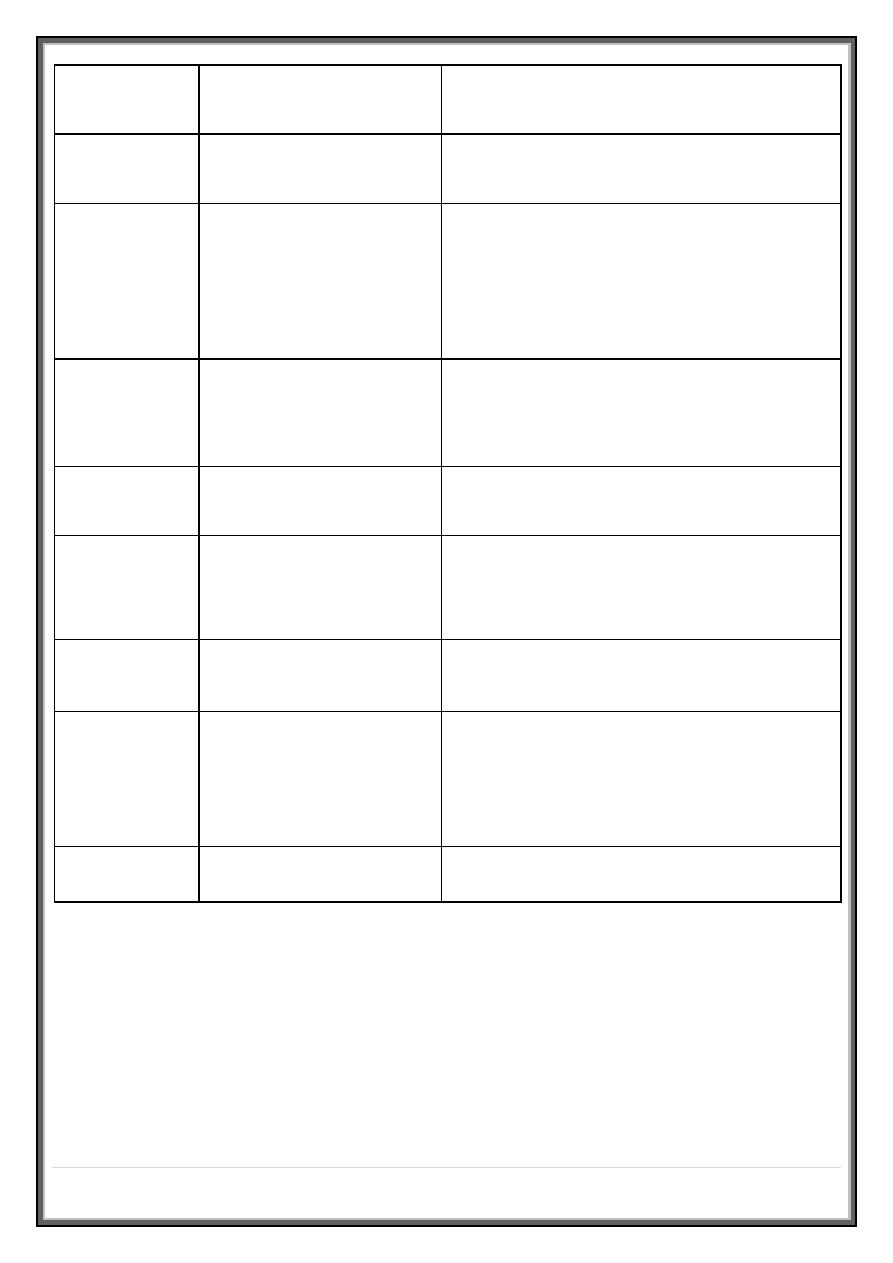

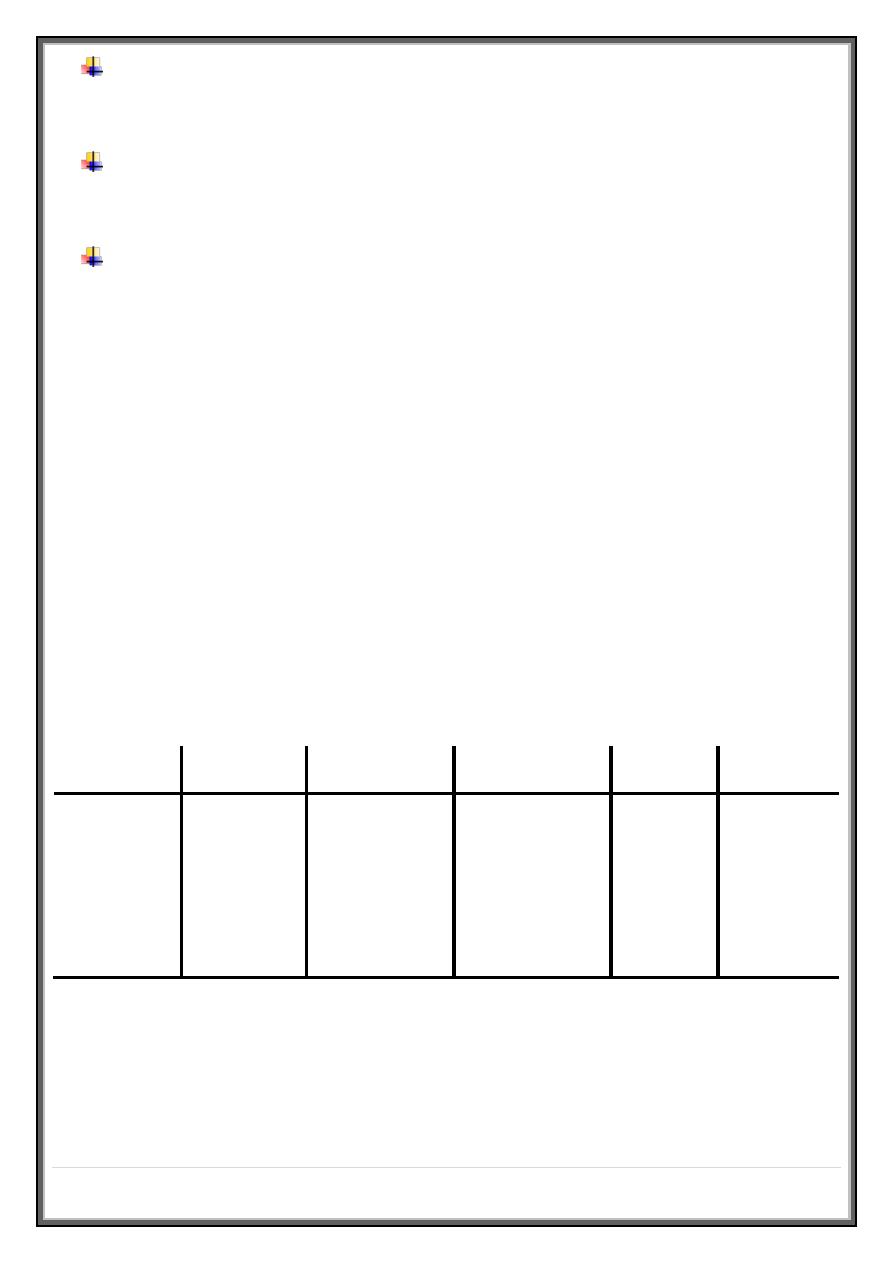

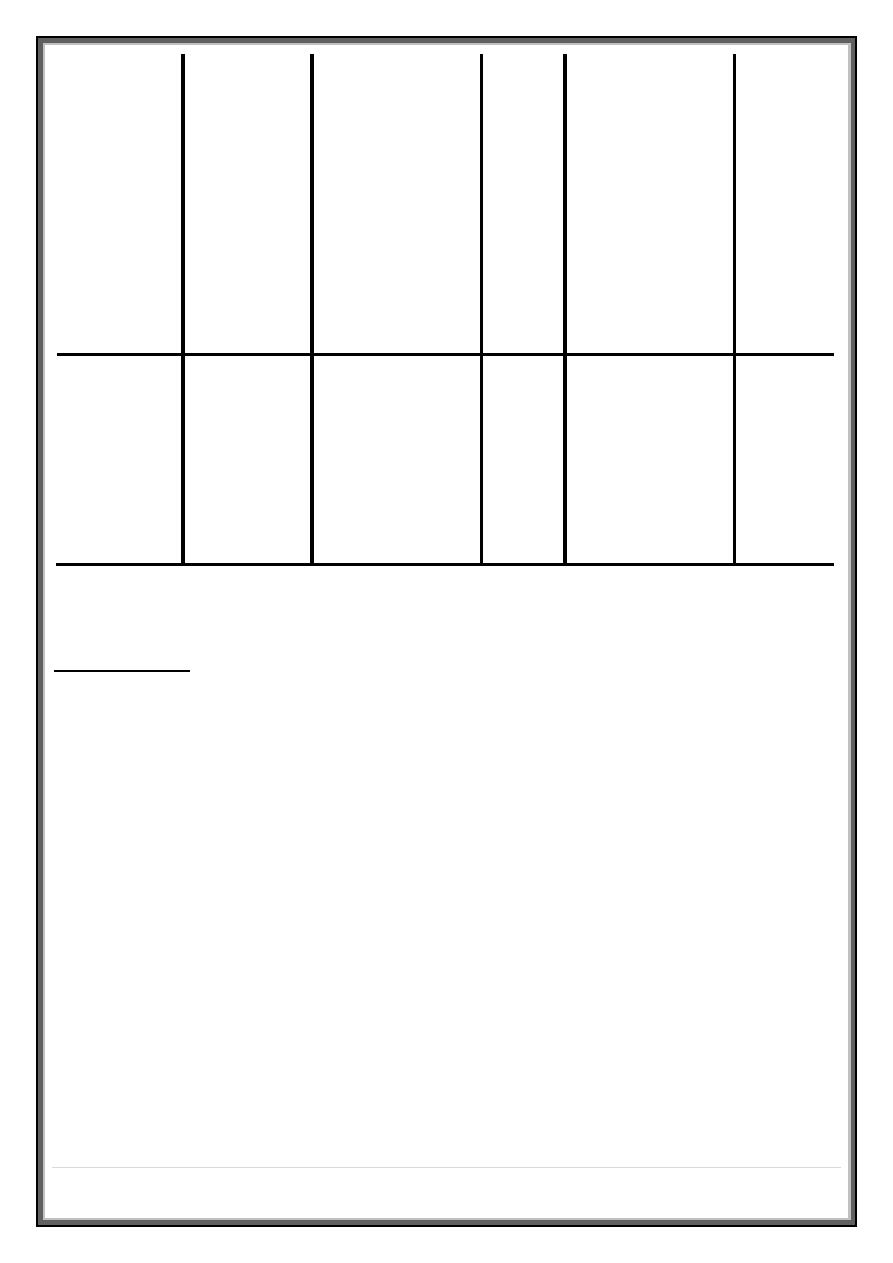

Origin

Common causes

Clinical features

Pharynx

Post-nasal drip

History of chronic rhinitis

Larynx

Laryngitis, tumor,

whooping cough, croup

Voice or swallowing altered, harsh or

painful cough

Paroxysms of cough, often associated

with stridor

Trachea

Tracheitis

Raw retrosternal pain with cough

Bronchi

Bronchitis (acute) and

COPD

Dry or productive, worse in mornings

Asthma

Usually dry, worse at night

Eosinophilic bronchitis Features similar to asthma but no

airway hyper-reactivity (AHR)

Bronchial carcinoma

Persistent (often with hemoptysis)

3 |

P a g e

Lung

parenchyma

Tuberculosis

Productive, often with hemoptysis

Pneumonia

Dry initially, productive later

Bronchiectasis

Productive, changes in posture induce sputum

production

Pulmonary

oedema

Often at night (may be productive of pink,

frothy sputum)

Interstitial

fibrosis

Dry, irritant and distressing

Drug side-

effect

ACE inhibitors

Dry cough

Patients with chronic cough present more of a diagnostic challenge, especially

when physical examination, chest X-ray and lung function studies are normal.

In this context, it is most often explained by cough-variant asthma (where

cough may be the principal or exclusive clinical manifestation), post-nasal drip

secondary to nasal or sinus disease, or gastro-oesophageal reflux with

aspiration.

4 |

P a g e

Diagnosis of the latter may require ambulatory pH monitoring or a prolonged

trial of anti-reflux therapy .

Between 10 and 15% of patients (particularly women) taking angiotensin-

converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors develop a drug-induced chronic cough .

Bordetella pertussis infection in adults can also result in protracted cough and

should be suspected in those in close contact with children.

While most patients with a bronchogenic carcinoma have an abnormal chest X-

ray on presentation, fibreoptic bronchoscopy or thoracic CT is advisable in most

adults (especially smokers)

In a small percentage of patients, dry cough may be the presenting feature of

interstitial lung disease .

Breathlessness

:

Breathlessness or dyspnea can be defined as the feeling of an uncomfortable

need to breathe.

It is unusual among sensations in having no defined receptors, no localised

representation in the brain, and multiple causes both in health (e.g. exercise)

and in diseases of the lungs, heart or muscles .

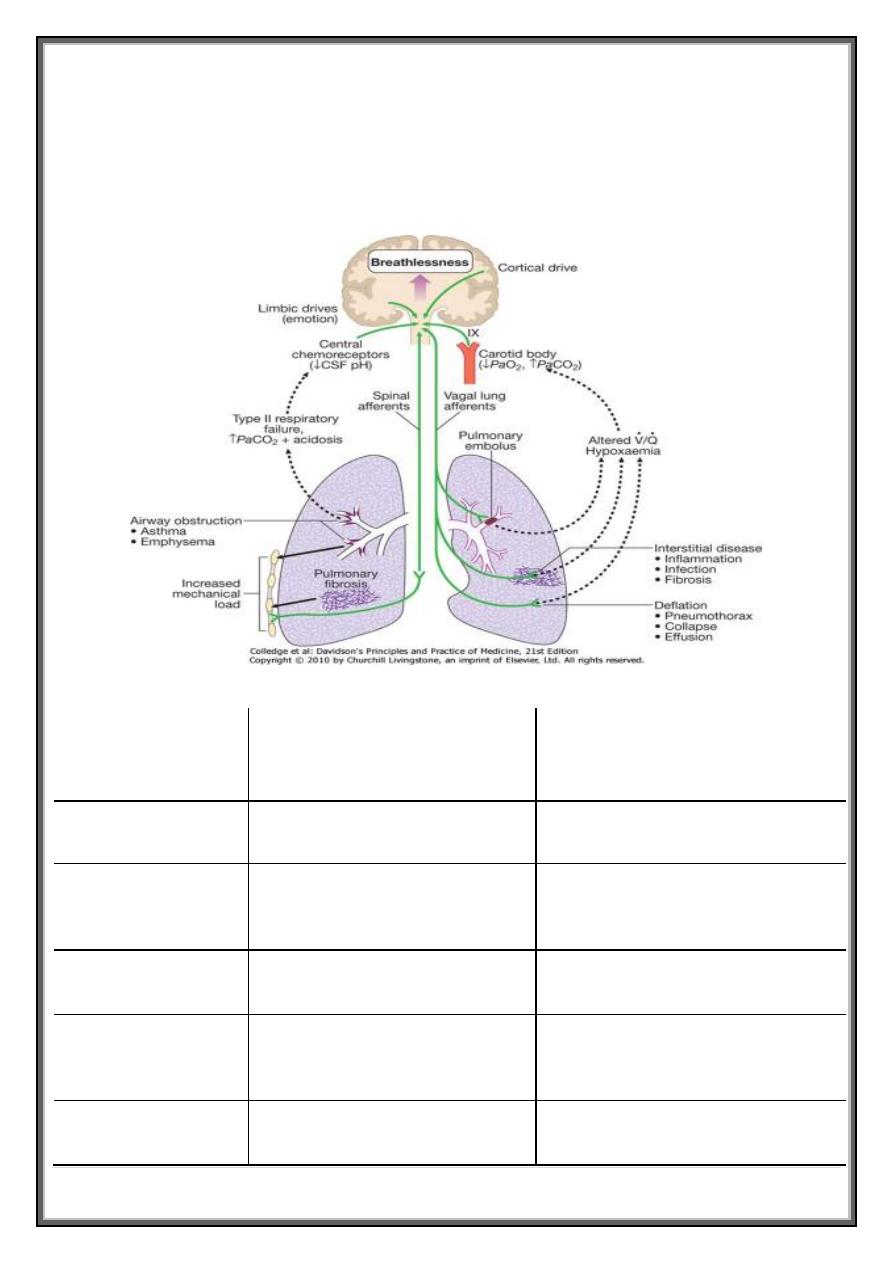

Pathophysiology

Respiratory diseases can stimulate breathing and dyspnoea by :

1. stimulating intrapulmonary sensory nerves (e.g. pneumothorax, interstitial

inflammation and pulmonary embolus)

2. increasing the mechanical load on the respiratory muscles (e.g. airflow

obstruction or pulmonary fibrosis)

3. Causing hypoxia, hypercapnia or acidosis, stimulating chemoreceptors .

5 |

P a g e

4. In cardiac failure, pulmonary congestion reduces lung compliance and can

also obstruct the small airways .

5. In addition, during exercise, reduced cardiac output limits oxygen supply

to the skeletal muscles, causing early lactic academia and further

stimulating breathing via the central chemoreceptors .

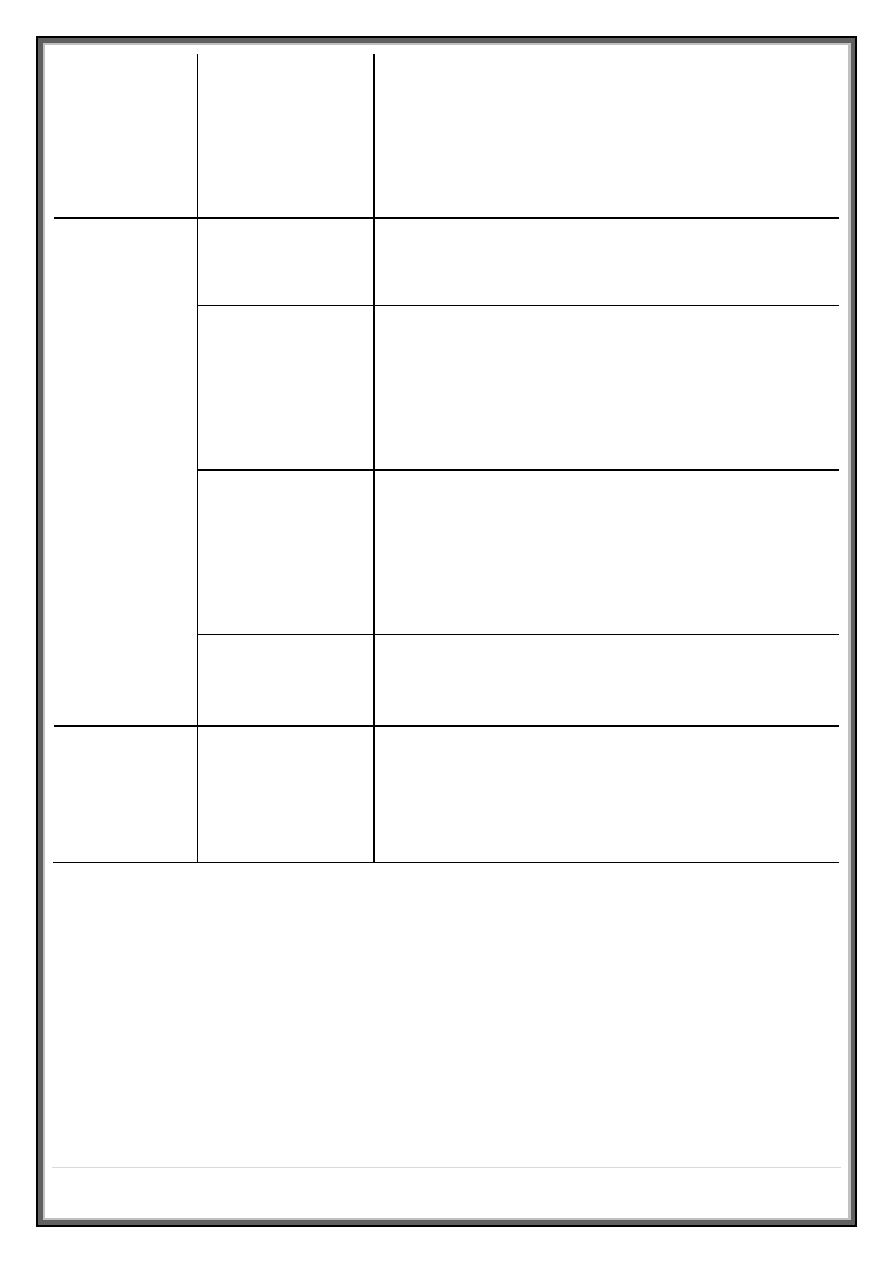

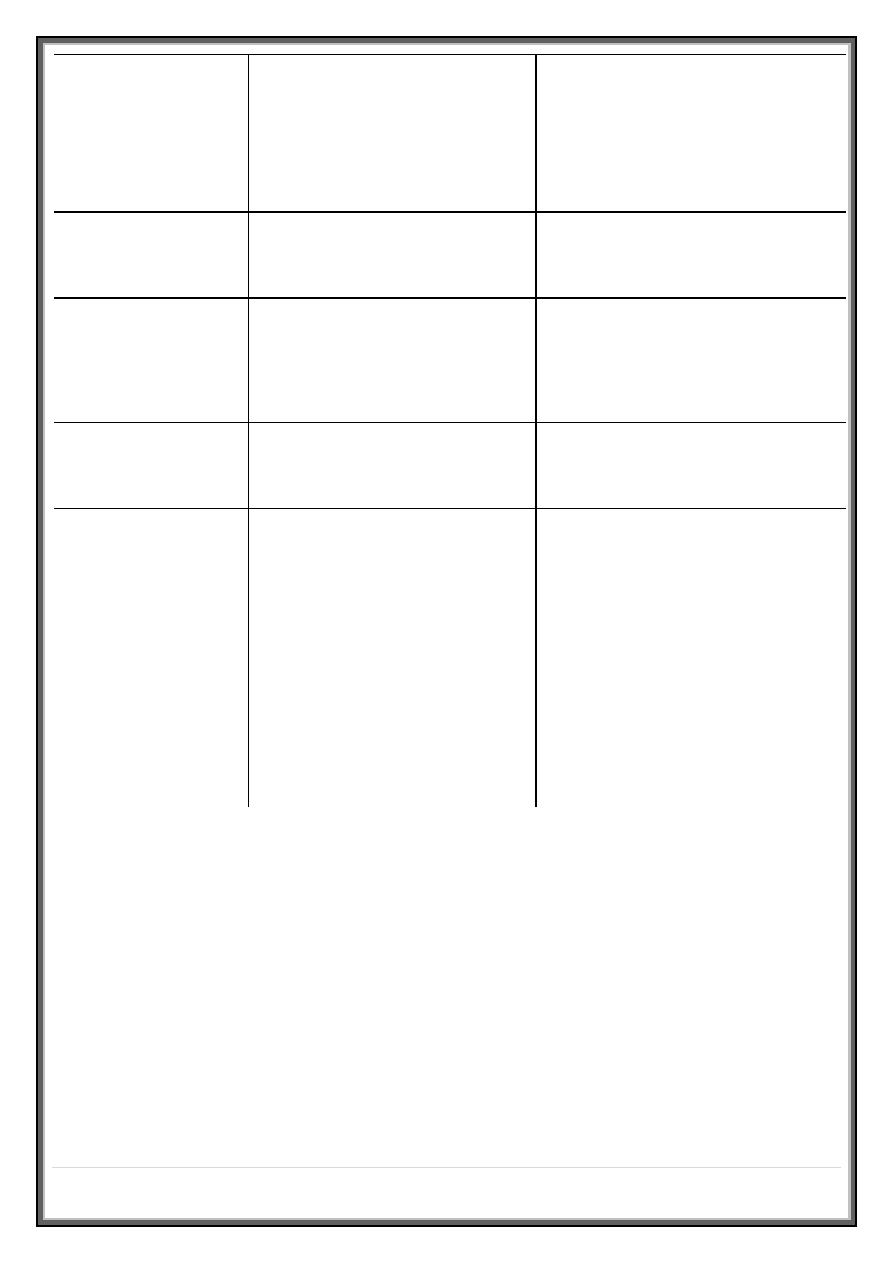

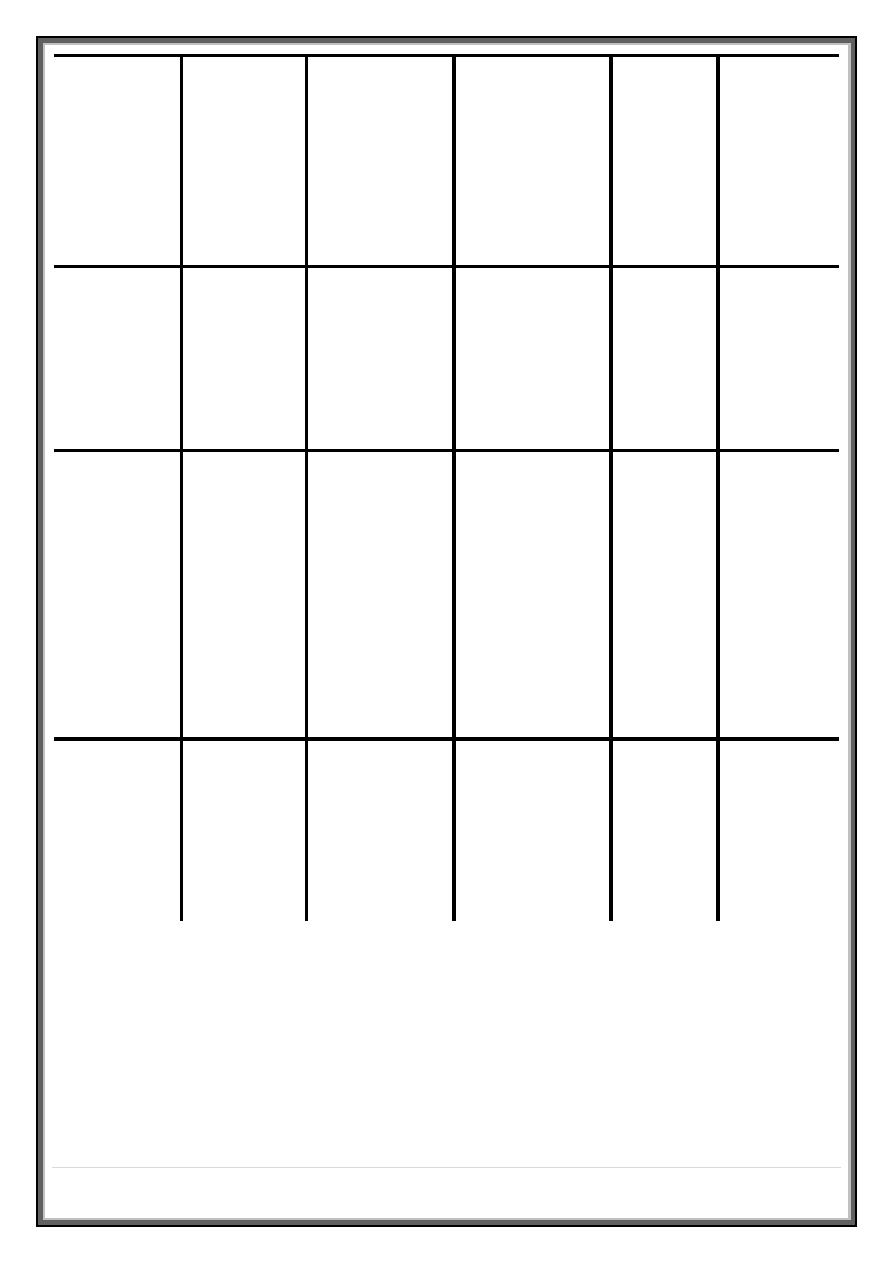

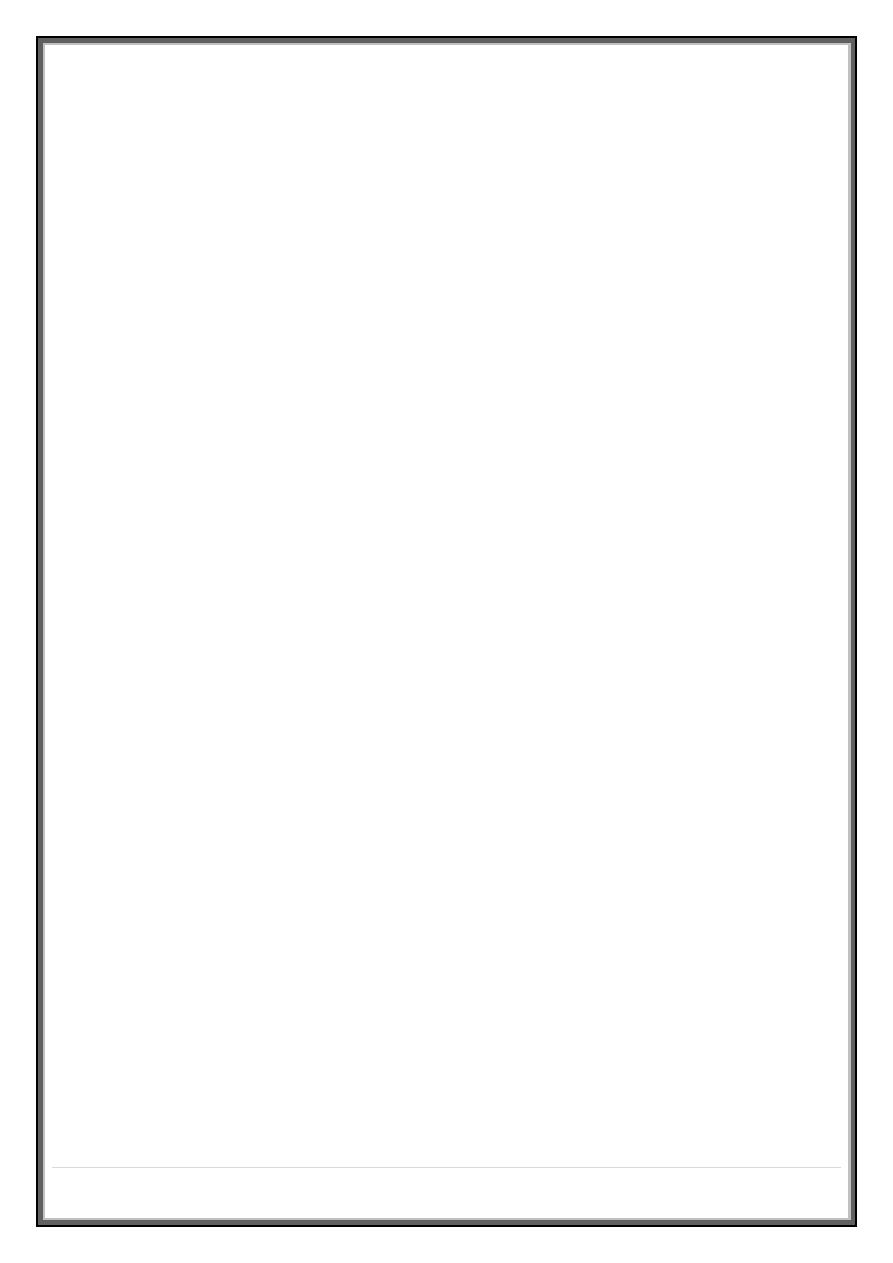

System

Acute dyspnea

Chronic exertional

dyspnea

Cardiovascular

*Acute pulmonary edema Chronic heart failure

Myocardial ischemia

(angina equivalent)

Respiratory

*Acute severe asthma

*COPD

*Acute exacerbation of

COPD

*Chronic asthma

*Pneumothorax

Bronchial carcinoma

6 |

P a g e

*Pneumonia

*Pulmonary embolus

Interstitial lung disease

(sarcoidosis, fibrosing

alveolitis, extrinsic allergic

alveolitis, pneumoconiosis)

Acute respiratory distress

syndrome (ARDS)

Chronic pulmonary

thromboembolism

Inhaled foreign body

(especially in the child)

Lobar collapse

Lymphatic carcinomatosis

(may cause intolerable

breathlessness)

Laryngeal oedema (e.g.

anaphylaxis)

Large pleural effusion(s)

Others

Metabolic acidosis (e.g.

diabetic ketoacidosis,

lactic acidosis, uremia,

overdose of salicylates,

ethylene glycol

poisoning) Psychogenic

hyperventilation (anxiety

or panic-related)

Severe anemia

Obesity

Deconditioning

Chronic exertional breathlessness

The cause of breathlessness is often apparent from a careful clinical

history. Key questions include :

How is your breathing at rest and overnight ?

7 |

P a g e

In COPD, there is a fixed, structural limit to maximum ventilation, and a

tendency for progressive hyperinflation during exercise .

Breathlessness is mainly apparent during mobilization, and patients

usually report minimal symptoms at rest and overnight.

In contrast, patients with significant asthma are often woken from their sleep

by breathlessness with chest tightness and wheeze .

Orthopnea

, however, is common in COPD as well as in heart disease, because

airflow obstruction is made worse by cranial displacement of the diaphragm by

the abdominal contents when recumbent, so many patients choose to sleep

propped up .

It may thus not be a useful differentiating symptom, unless there is a clear

history of previous angina or infarction to suggest cardiac disease .

Variability within and between days is a hallmark of asthma; in mild asthma the

patient may be free of symptoms and signs when well .

Gradual, progressive loss of exercise capacity over months and years with

consistent disability over days is typical of COPD .

When asthma is suspected, the degree of variability is best documented by

home peak flow monitoring .

Relentless, progressive breathlessness that is also present at rest, often

accompanied by a dry cough, suggests interstitial fibrosis .

8 |

P a g e

Impaired left ventricular function can also cause chronic exertional

breathlessness, cough and wheeze. A history of angina, hypertension or

myocardial infarction may be useful in implicating a cardiac cause.

The suspicion of cardiac impairment may be confirmed by a displaced apex

beat, a raised JVP and cardiac murmurs (although these signs can occur in

severe cor pulmonale) .

The chest X-ray may show cardiomegaly and an electrocardiogram (ECG) and

echocardiogram may provide evidence of left ventricular disease.

Measurement of arterial blood gases may be of value, since in the absence of

an intracardiac shunt or pulmonary oedema the PaO2 in cardiac disease is

normal and the PaCO2 is low or normal .

Did you have breathing problems in childhood or at school ?

When present, a history of childhood wheeze increases the likelihood of

asthma, although this history may be absent in late-onset asthma .

Similarly, a history of atopic allergy increases the likelihood of asthma .

Do you have other symptoms along with your breathlessness ?

Digital or perioral paresthesia and a feeling that 'I cannot get a deep enough

breath in' are typical features of psychogenic hyperventilation, but this cannot

be diagnosed until investigations have excluded other potential causes of

breathlessness.

Additional symptoms include lightheadedness, central chest discomfort or

even carpopedal spasm due to acute respiratory alkalosis .

These alarming symptoms may provoke further anxiety and exacerbate

hyperventilation .

9 |

P a g e

Psychogenic breathlessness rarely disturbs sleep, frequently occurs at

rest, may be provoked by stressful situations and may even be relieved by

exercise .

The Nijmegen questionnaire can be used to enumerate some of the typical

symptoms of hyperventilation. Arterial blood gases show normal PO2, low PCO2

and alkalosis .

Pleuritic chest pain in a patient with chronic breathlessness, particularly if it

occurs in more than one site over time, should raise suspicion of

thromboembolic disease .

Thromboembolism may occasionally present as chronic breathlessness with no

other specific features, and should always be considered before a diagnosis of

psychogenic hyperventilation is made.

Factors suggesting psychogenic hyperventilation

'Inability to take a deep breath '

Frequent sighing/erratic ventilation at rest

Short breath-holding time in the absence of severe respiratory disease

Difficulty in performing/inconsistent spirometry man [oelig ]uvres

High score (over 26) on Nijmegen questionnaire

Induction of symptoms during submaximal hyperventilation

Resting end-tidal CO2 < 4.5%

Associated digital paresthesia

Morning headache is an important symptom in patients with breathlessness, as

it may signal the onset of carbon dioxide retention and respiratory failure .

10 |

P a g e

This is particularly significant in patients with musculoskeletal disease impairing

respiratory function (e.g. kyphoscoliosis or muscular dystrophy) .

Acute severe breathlessness

This is one of the most common and dramatic medical emergencies .

Although there are a number of possible causes, the history and a rapid but

careful examination will usually suggest a diagnosis which can be confirmed by

routine investigations, including chest X-ray, ECG and arterial blood gases .

History

It is important to establish the rate of onset and severity of the breathlessness

and whether associated cardiovascular symptoms (chest pain, palpitations,

sweating and nausea) or respiratory symptoms (cough, wheeze, hemoptysis,

stridor) are present.

A previous history of repeated episodes of left ventricular failure, asthma or

exacerbations of COPD is valuable .

In the severely ill patient it may be necessary to obtain the history from

accompanying relatives or careers .

In children, the possibility of inhalation of a foreign body or acute epiglottitis

should always be considered .

Pulmonary oedema is suggested by pink frothy sputum and bi-basal

crackles, asthma or COPD by wheeze and prolonged expiration ,

Pneumothorax by a silent resonant hemi thorax, and pulmonary embolus

by severe breathlessness with normal breath sounds .

11 |

P a g e

The peak expiratory flow should be measured whenever possible. Leg

swelling may suggest cardiac failure or, if asymmetrical, venous

thrombosis .

Arterial blood gases, chest X-ray and an ECG should be obtained to confirm

the clinical diagnosis, and high concentrations of oxygen given pending

results.

Urgent endotracheal intubation may become necessary if the conscious

level declines or if severe respiratory acidosis is present .

Clinical assessment

The following should be assessed and documented immediately :

1. Level of consciousness

2. Degree of central cyanosis

3. Evidence of anaphylaxis (urticaria or angioedema)

4. Patency of the upper airway

5. Ability to speak (in single words or sentences)

6. Cardiovascular status (heart rate and rhythm, blood pressure and degree

of peripheral perfusion) .

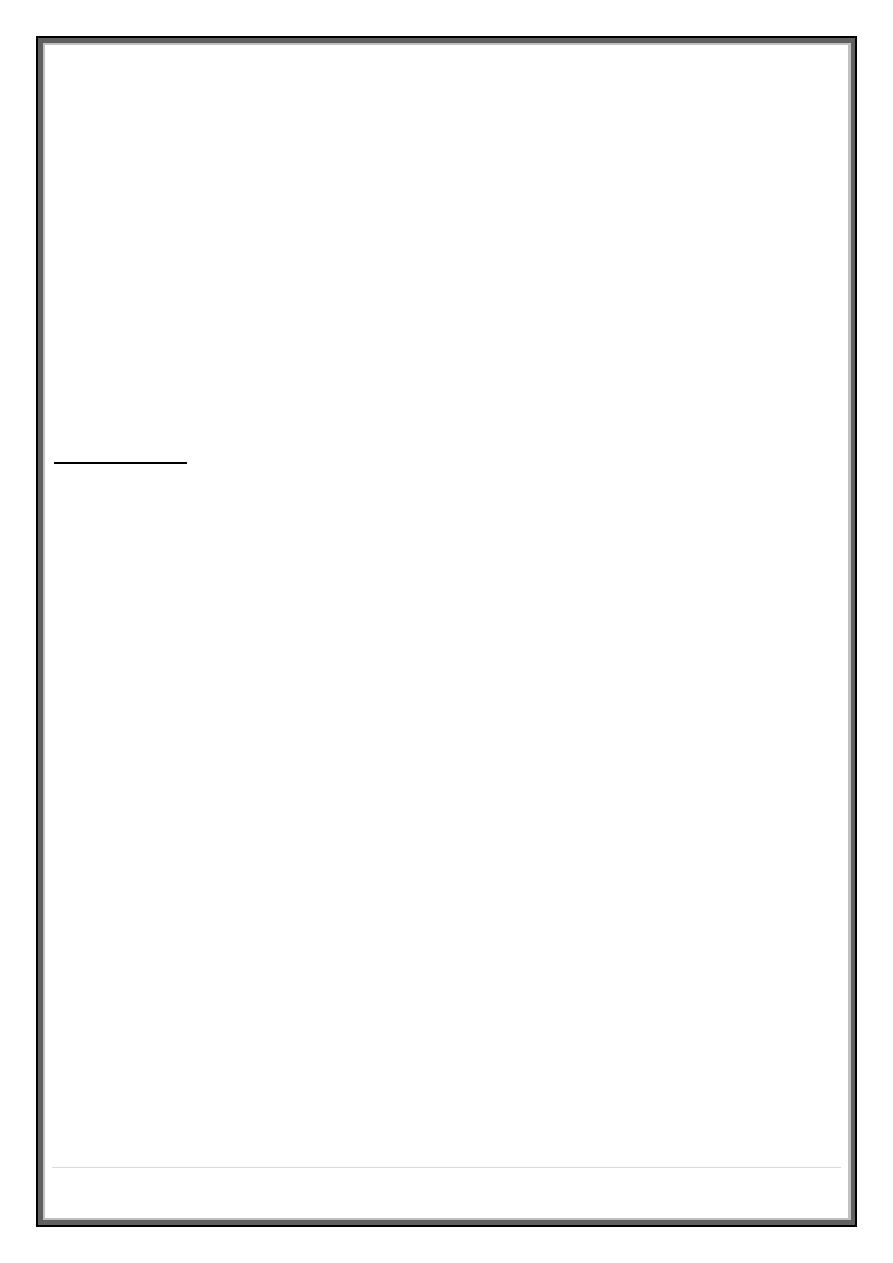

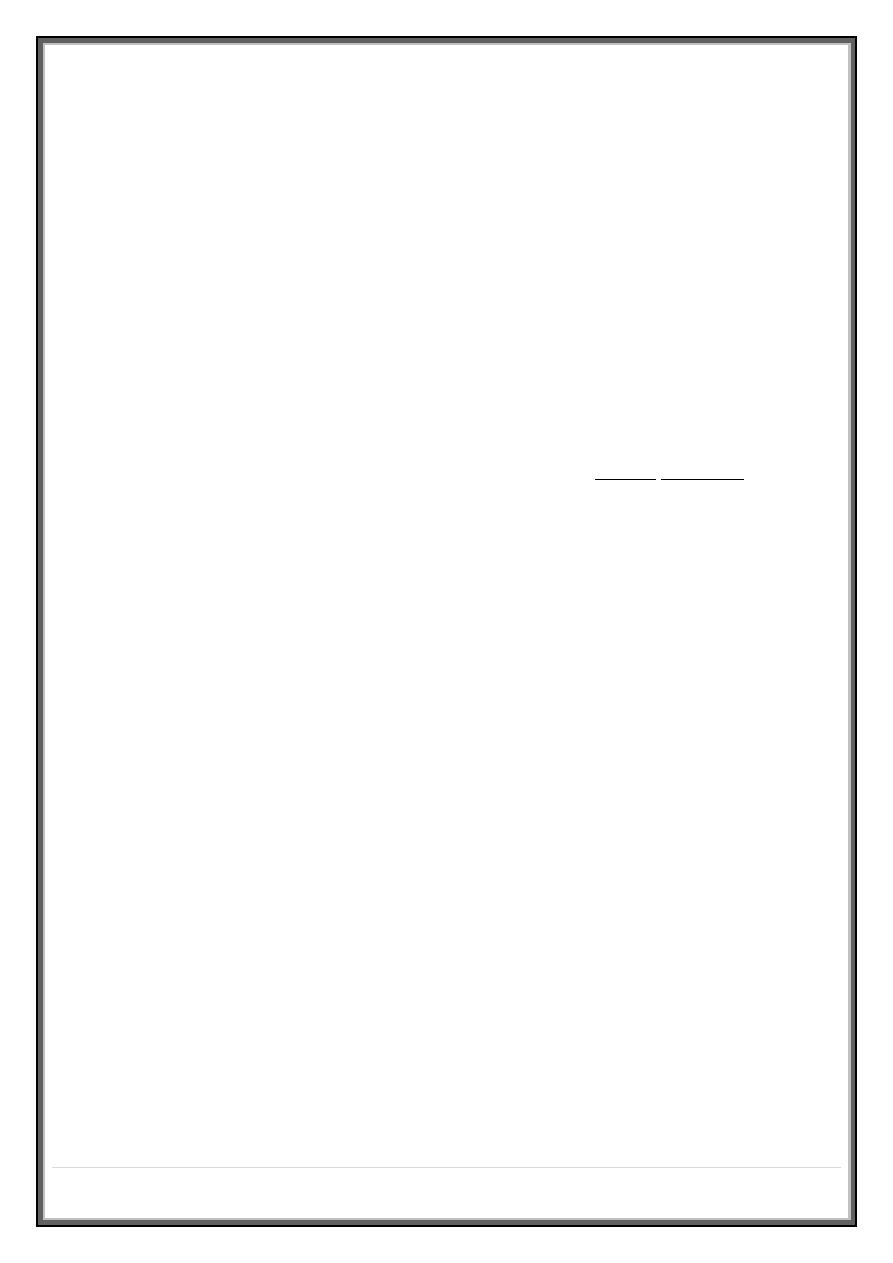

Condition

History

Signs

CXR

ABG

ECG

Pulmonary

oedema

Chest pain,

palpitations,

orthopnea,

cardiac

history*

Central

cyanosis, ↑JVP,

sweating, cool

extremities,

basal

crepitation's*

Cardiomegaly,

oedema/pleural

effusions*

↓PaO

2

↓PaCO

2

Sinus

tachycardia,

ischemia*,

arrhythmia

12 |

P a g e

Massive

pulmonary

embolus

Risk factors,

chest pain,

pleurisy,

syncope*,

dizziness*

Central

cyanosis,

↑JVP*, absence

of signs in the

lung*, shock

(tachycardia,

hypotension)

Often normal

Prominent hilar

vessels, oligaemic

lung fields*

↓PaO

2

↓PaCO

2

Sinus

tachycardia,

RBBB, S

1

Q

3

T

3

pattern

↓T (V

1

-V

4

)

Acute

severe

asthma

History of

asthma,

asthma

medications,

wheeze*

Tachycardia,

pulses

paradoxes,

cyanosis (late),

JVP →*, ↓peak

flow, wheeze*

Hyperinflation

only (unless

complicated by

pneumothorax)*

↓PaO2

↓PaCO2

(↑PaCO2

in

extremis)

Sinus

tachycardia

(bradycardia

in extremis)

Acute

exacerbatio

n of COPD

Previous

episodes*,

smoker. If in

type II

respiratory

failure may be

drowsy

Cyanosis,

hyperinflation*,

signs of CO2

retention (flapping

tremor, bounding

pulses)*

Hyperinflation*,

bullae, complicating

pneumothorax

↓ or ⇓PaO2

PaCO2 in type

II failure ±

↑H+, ↑HCO3

in chronic

type II failure

Normal, or signs

of right

ventricular

strain

Pneumonia

Prodromal

illness*,

fever*,

rigors*,

pleurisy*

Fever,

confusion,

pleural rub*,

consolidation*,

cyanosis (if

severe)

Pneumonic

consolidation*

↓PaO2

↓PaCO2

(↑ in

extremis)

Tachycardia

13 |

P a g e

Metabolic

acidosis

Evidence of

diabetes

mellitus or

renal

disease,

aspirin or

ethylene

glycol

overdose

Fetor (ketones),

hyperventilation

without heart or

lung signs*,

dehydration*,

air hunger

Normal PaO2 normal

⇓

PaCO2, ↑H+

Psychogenic Previous

episodes,

digital or

peri-oral

dysesthesias

No cyanosis, no

heart or lung

signs,

carpopedal

spasm

Normal PaO2 normal*

⇓

PaCO2, ↓H+*

Hemoptysis

Coughing up blood, irrespective of the amount, is an alarming symptom and

patients nearly always seek medical advice .

o A history should be taken to establish that it is true hemoptysis and not

hematemesis, or gum or nose bleeding .

o Hemoptysis must always be assumed to have a serious cause until this is

excluded.

o Many episodes of hemoptysis remain unexplained even after full

investigation, and are likely to be caused by simple bronchial infection .

o A history of repeated small hemoptysis, or blood-streaking of sputum, is

highly suggestive of bronchial carcinoma .

o Fever, night sweats and weight loss suggest tuberculosis .

14 |

P a g e

o Pneumococcal pneumonia often causes 'rusty'-colored sputum but can

cause frank hemoptysis, as can all supportive pneumonic infections

including lung abscess .

o Bronchiectasis and intracavitary mycetoma can cause catastrophic

bronchial hemorrhage, and in these patients there may be a history of

previous tuberculosis or pneumonia in early life .

o Finally, pulmonary thromboembolism is a common cause of hemoptysis

and should always be considered.

Causes of hemoptysis

Bronchial disease

1. Carcinoma *

2. Bronchiectasis *

3. Acute bronchitis *

4. Bronchial adenoma

5. Foreign body

Parenchymal disease

1. Tuberculosis *

2. Supportive pneumonia

3. Lung abscess

4. Parasites (e.g. hydatid disease, flukes)

5. Trauma

6. Actinomycosis

7. Mycetoma

Lung vascular disease

1. Pulmonary infarction *

2. Good pasture's syndrome

3. Polyarthritis' nodosa

15 |

P a g e

4. Idiopathic pulmonary haemosiderosis

Cardiovascular disease

1. Acute left ventricular failure *

2. Mitral stenosis

3. Aortic aneurysm

Blood disorders

1. Leukemia

2. Hemophilia

3. Anticoagulants

Physical examination may reveal additional clues. Finger clubbing suggests

bronchial carcinoma or bronchiectasis; other signs of malignancy, such as

cachexia, hepatomegaly and lymphadenopathy, should also be sought .

Fever, pleural rub or signs of consolidation occur in pneumonia or

pulmonary infarction; a minority of patients with pulmonary infarction

also have unilateral leg swelling or pain suggestive of deep venous

thrombosis .

Rashes, hematuria and digital infarcts suggest an underlying systemic

disease such as a vasculitis, which may be associated with hemoptysis .

In the vast majority of cases, however, the haemoptysis itself is not life-

threatening and a logical sequence of investigations should be followed :

Chest X-ray, which may give evidence of a localized lesion including

pulmonary infarction, tumor (malignant or benign), pneumonia,

mycetoma or tuberculosis

Full blood count and clotting screen

Bronchoscopy after acute bleeding has settled, which may reveal a central

bronchial carcinoma (not visible on the chest X-ray) and permit biopsy and

tissue diagnosis

16 |

P a g e

CTPA, which may reveal underlying pulmonary thromboembolic disease or

alternative causes of hemoptysis not seen on the chest X-ray (e.g.

pulmonary arteriovenous malformation or small or hidden tumors) .

Management

In severe acute hemoptysis, the patient should be nursed upright (or on the side

of the bleeding if this is known), and given high-flow oxygen and appropriate

hemodynamic resuscitation .

Bronchoscopy in the acute phase is difficult and often merely shows blood

throughout the bronchial tree .

If radiology shows an obvious central cause, then rigid bronchoscopy under

general anesthesia may allow intervention to stop bleeding; however, the

source often cannot be visualized .

Intubation with a divided endotracheal tube may allow protected ventilation of

the unaffected lung to stabilize the patient .

Bronchial arteriography and embolization , or even emergency pulmonary

surgery, can be life-saving in the acute situation.

Done by: #MOHDZ Dr.bilal –

medicine

17 |

P a g e