Signals and Systems

Richard Baraniuk

NONRETURNABLE

NO REFUNDS, EXCHANGES, OR CREDIT ON ANY COURSE PACKETS

Signals and Systems

Course Authors:

Richard Baraniuk

Contributing Authors:

Thanos Antoulas

Richard Baraniuk

Adam Blair

Steven Cox

Benjamin Fite

Roy Ha

Michael Haag

Don Johnson

Ricardo Radaelli-Sanchez

Justin Romberg

Phil Schniter

Melissa Selik

John Slavinsky

Michael Wakin

Produced by:

The Connexions Project

http://cnx.rice.edu/

Rice University, Houston TX

Problems? Typos? Suggestions? etc...

http://mountainbunker.org/bugReport

c

2003 Thanos Antoulas, Richard Baraniuk, Adam Blair, Steven Cox, Benjamin Fite, Roy

Ha, Michael Haag, Don Johnson, Ricardo Radaelli-Sanchez, Justin Romberg, Phil Schniter,

Melissa Selik, John Slavinsky, Michael Wakin

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/1.0

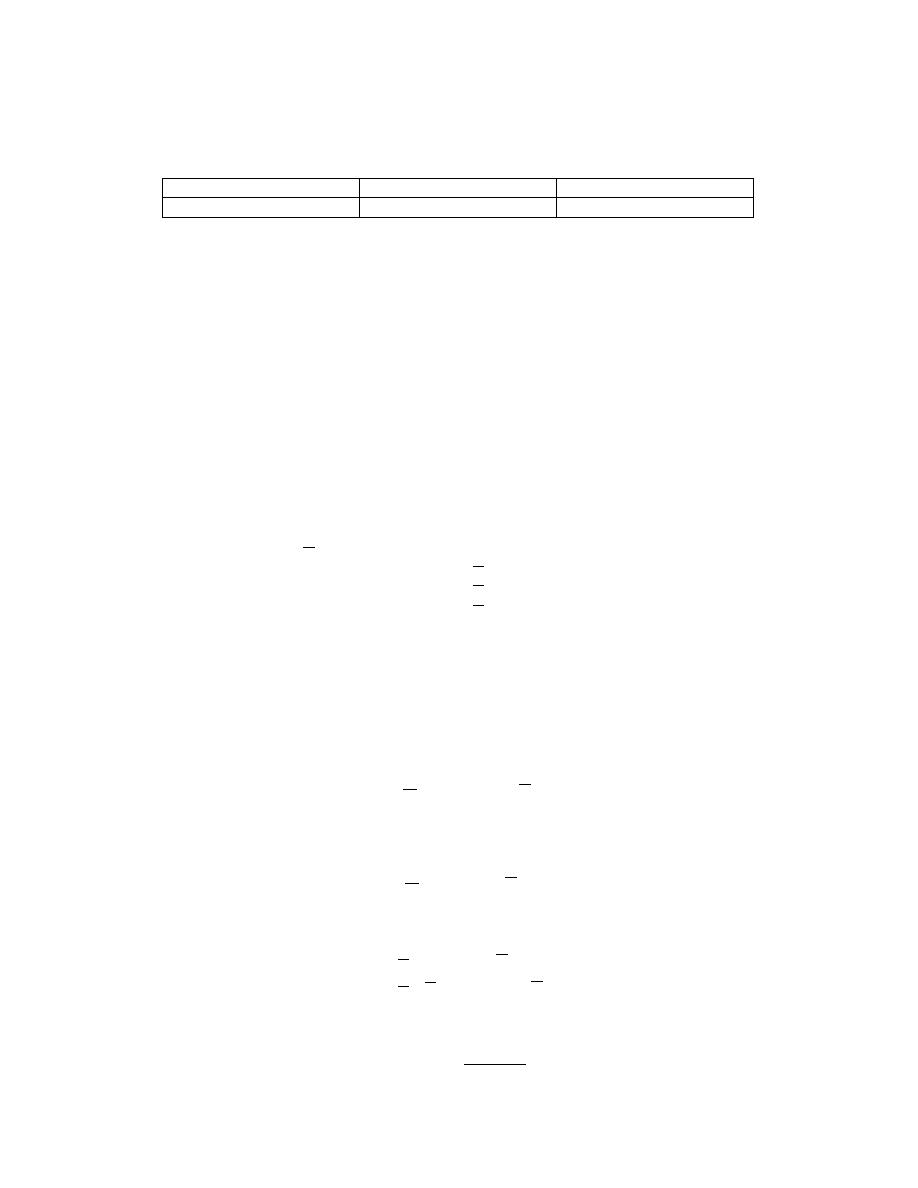

Table of Contents

1 Introduction

2.1 Signals Represent Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

2 Signals and Systems: A First Look

3.1 System Classifications and Properties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

3.2 Properties of Systems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

3.3 Signal Classifications and Properties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14

3.4 Discrete-Time Signals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

3.5 Useful Signals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

3.6 The Complex Exponential . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

3.7 Discrete-Time Systems in the Time-Domain . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

3.8 The Impulse Function . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

3.9 BIBO Stability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

3 Time-Domain Analysis of CT Systems

4.1 Systems in the Time-Domain . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

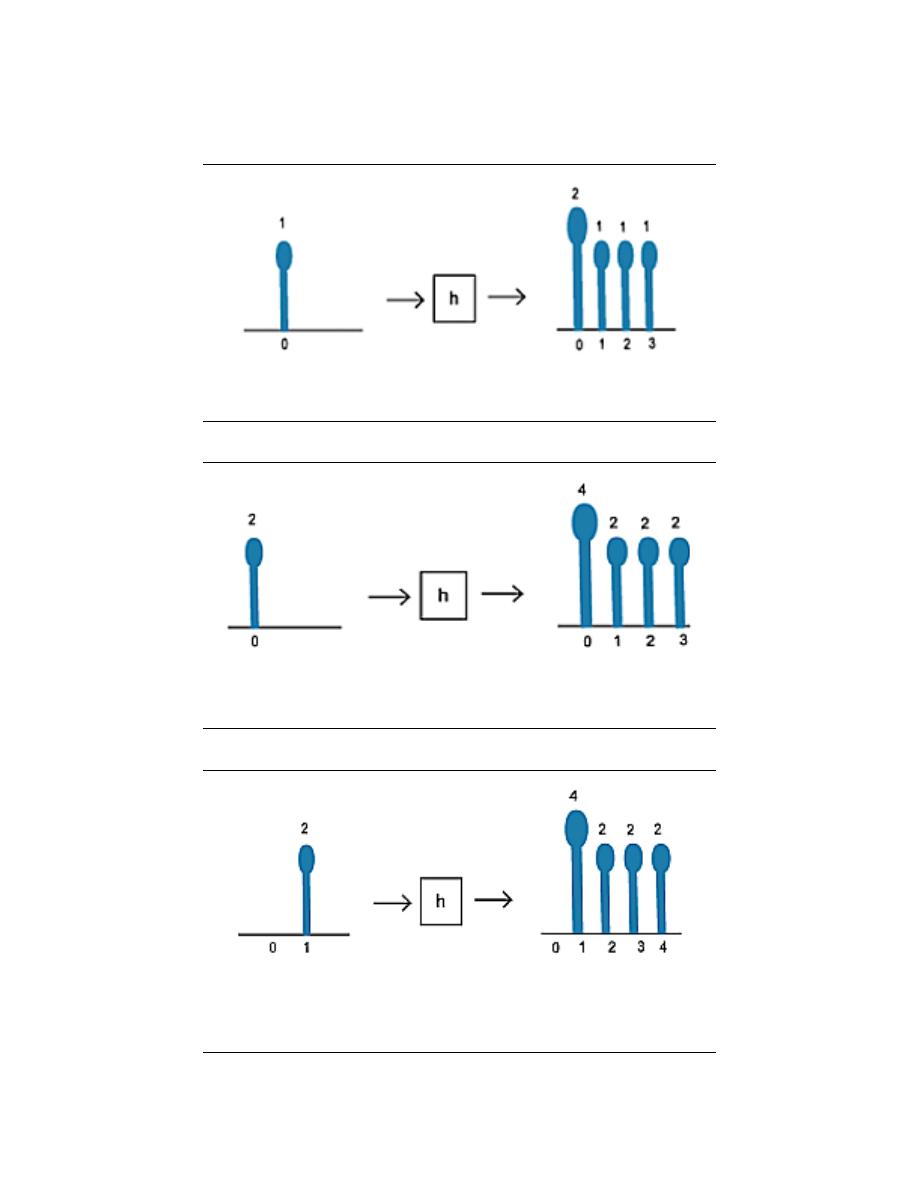

4.2 Continuous-Time Convolution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

4.3 Properties of Convolution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

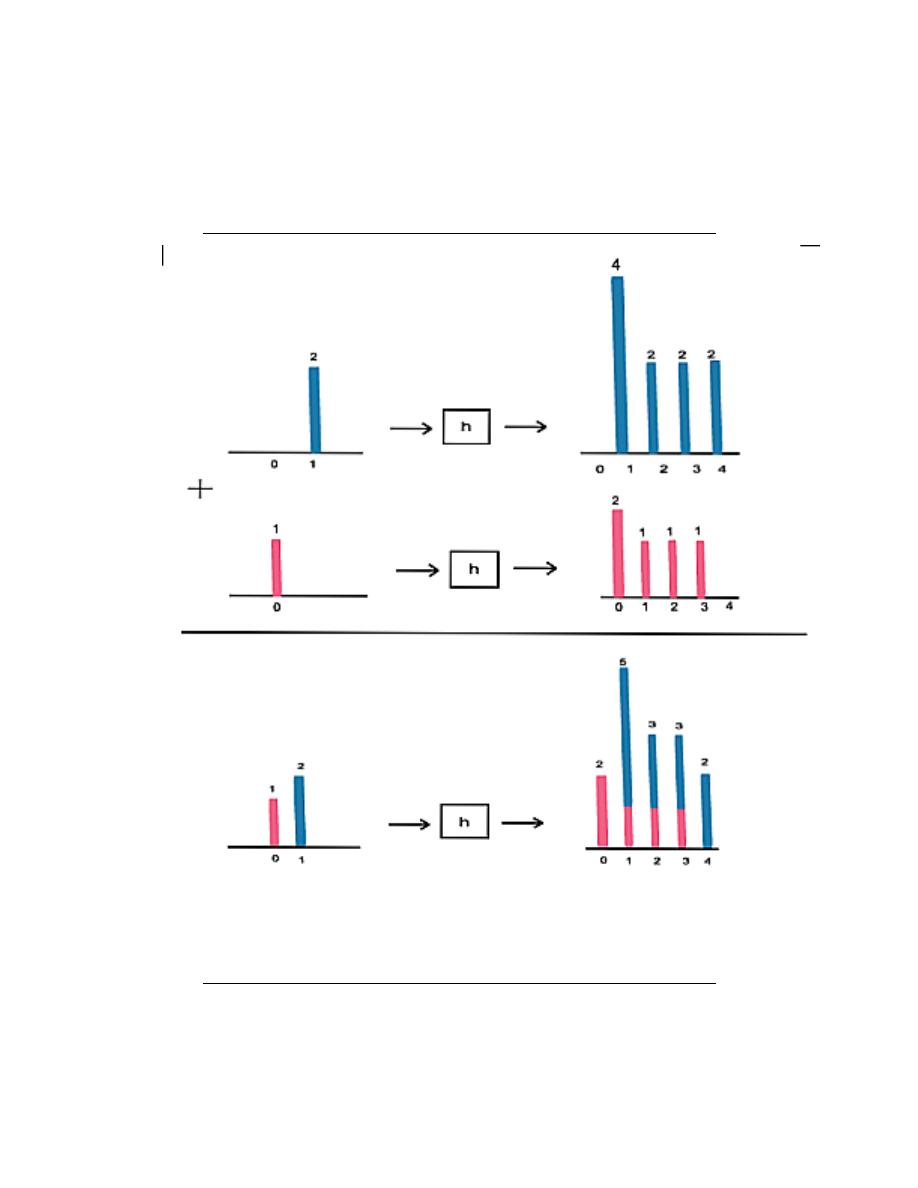

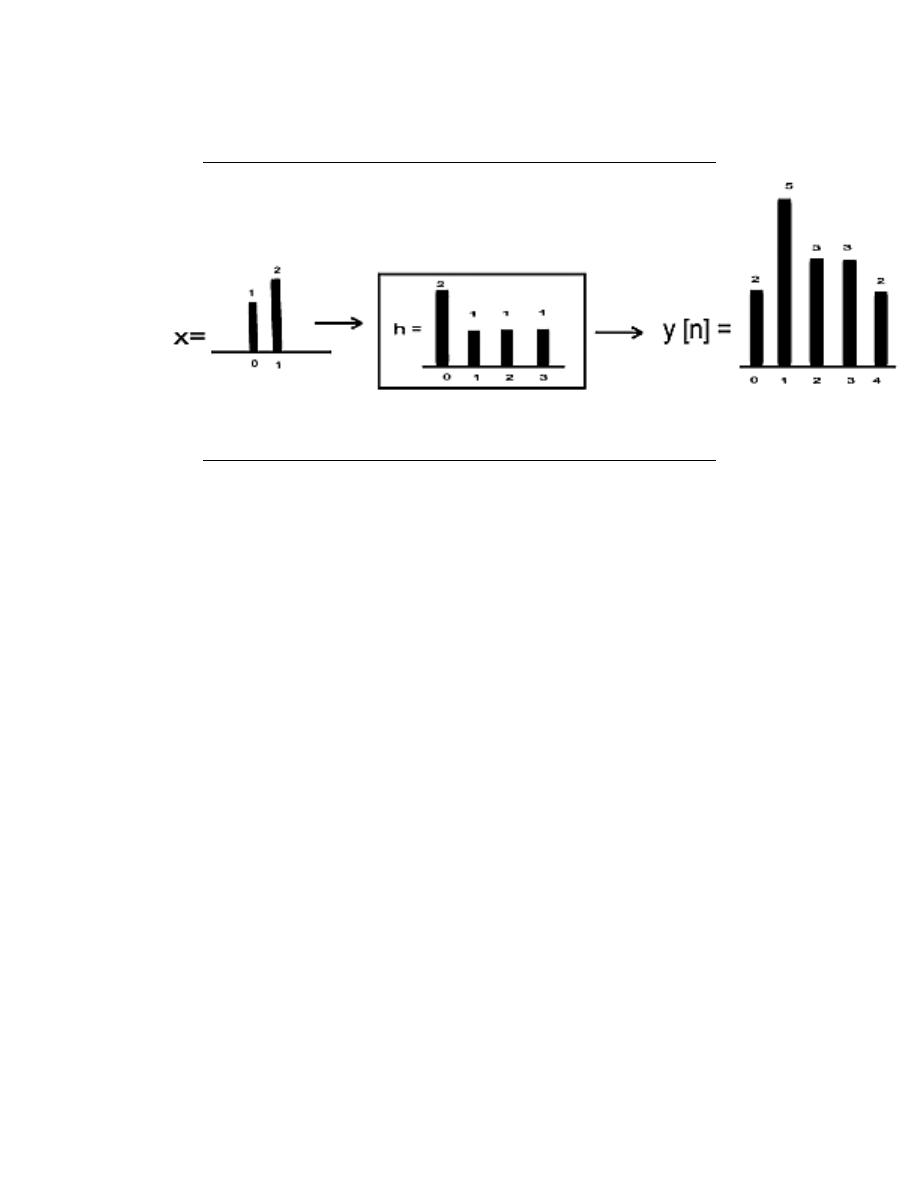

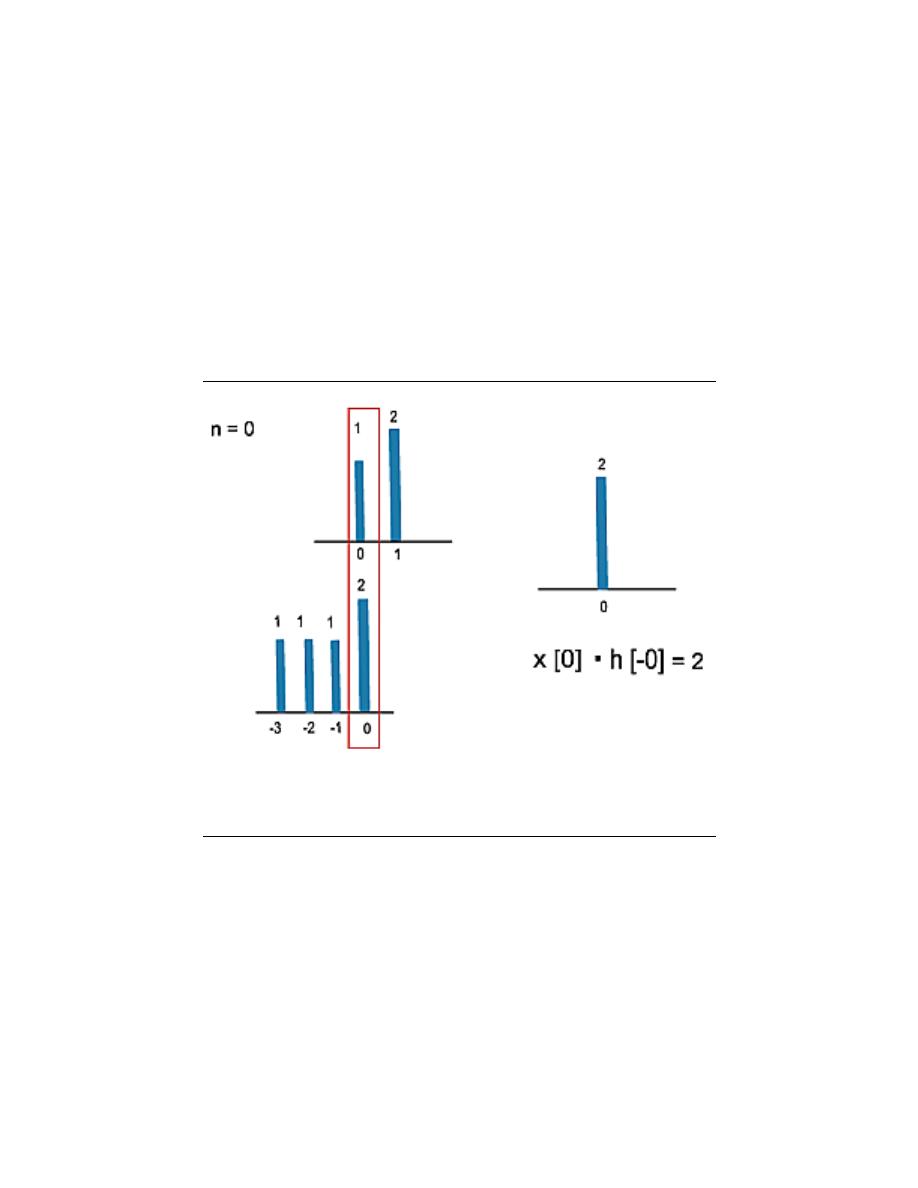

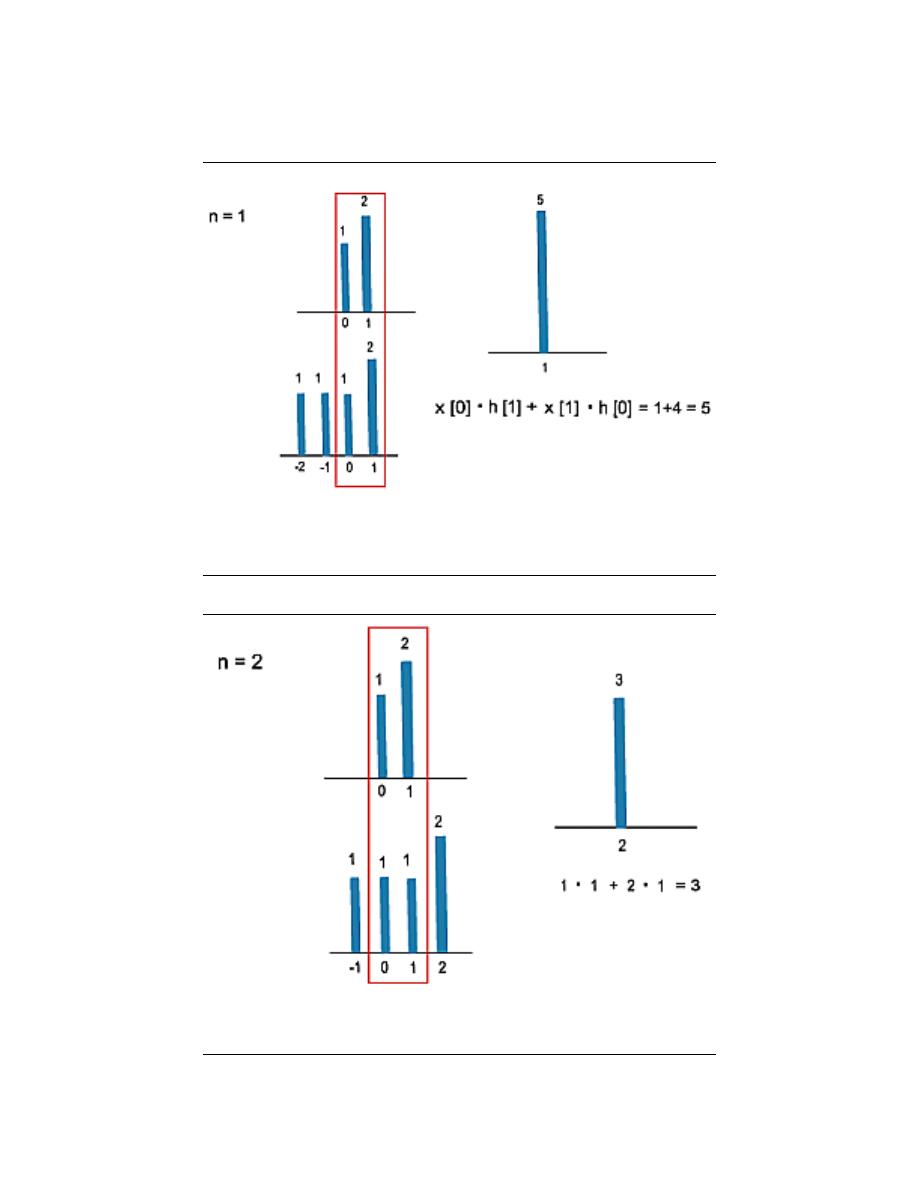

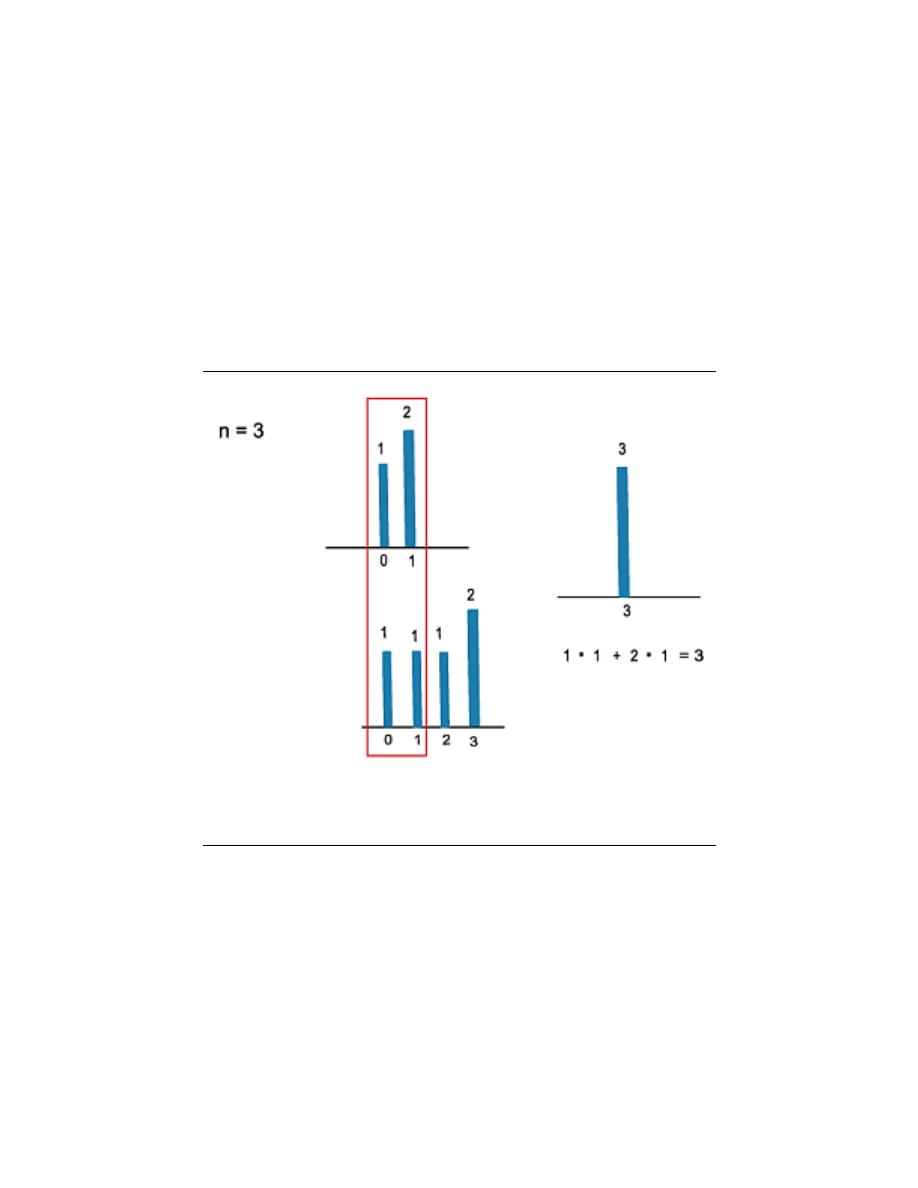

4.4 Discrete-Time Convolution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

4 Linear Algebra Overview

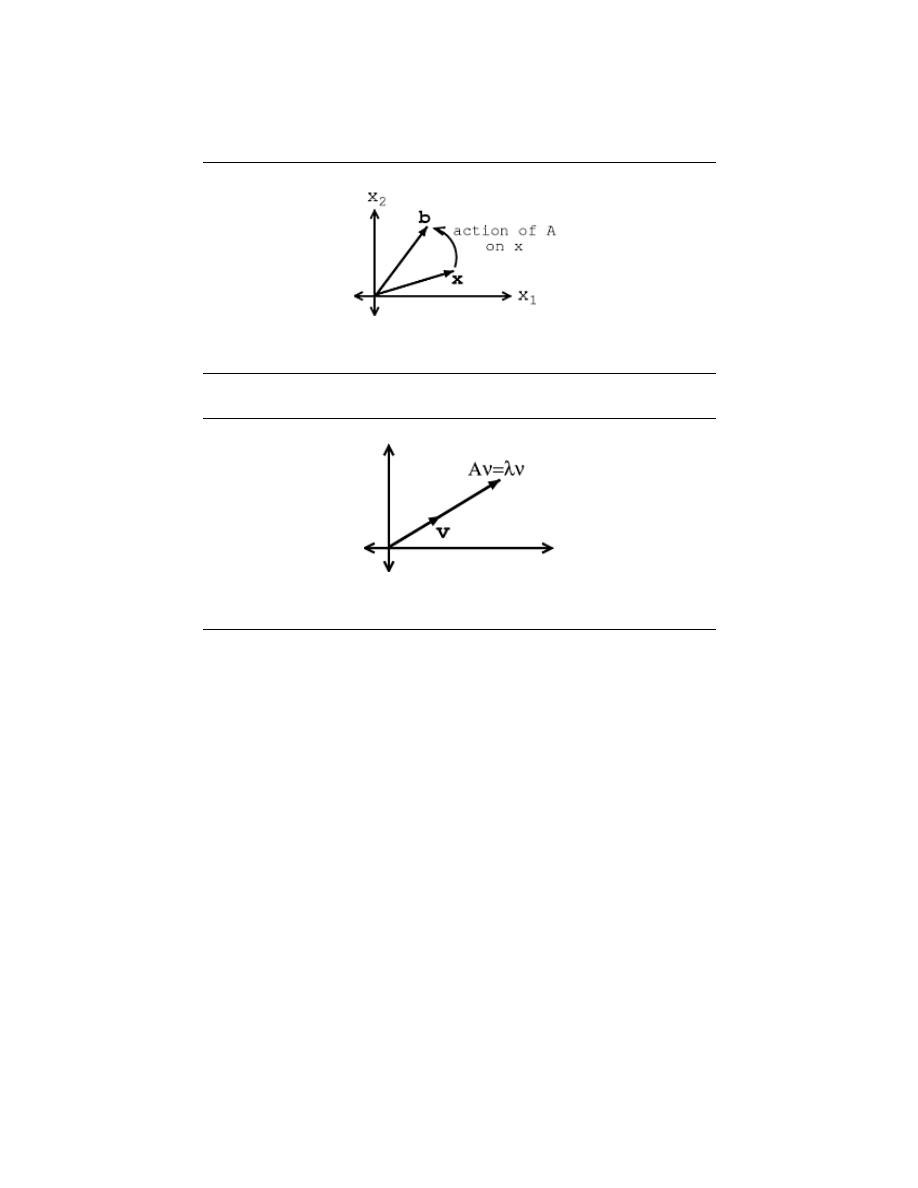

5.1 Linear Algebra: The Basics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

5.2 Vector Basics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

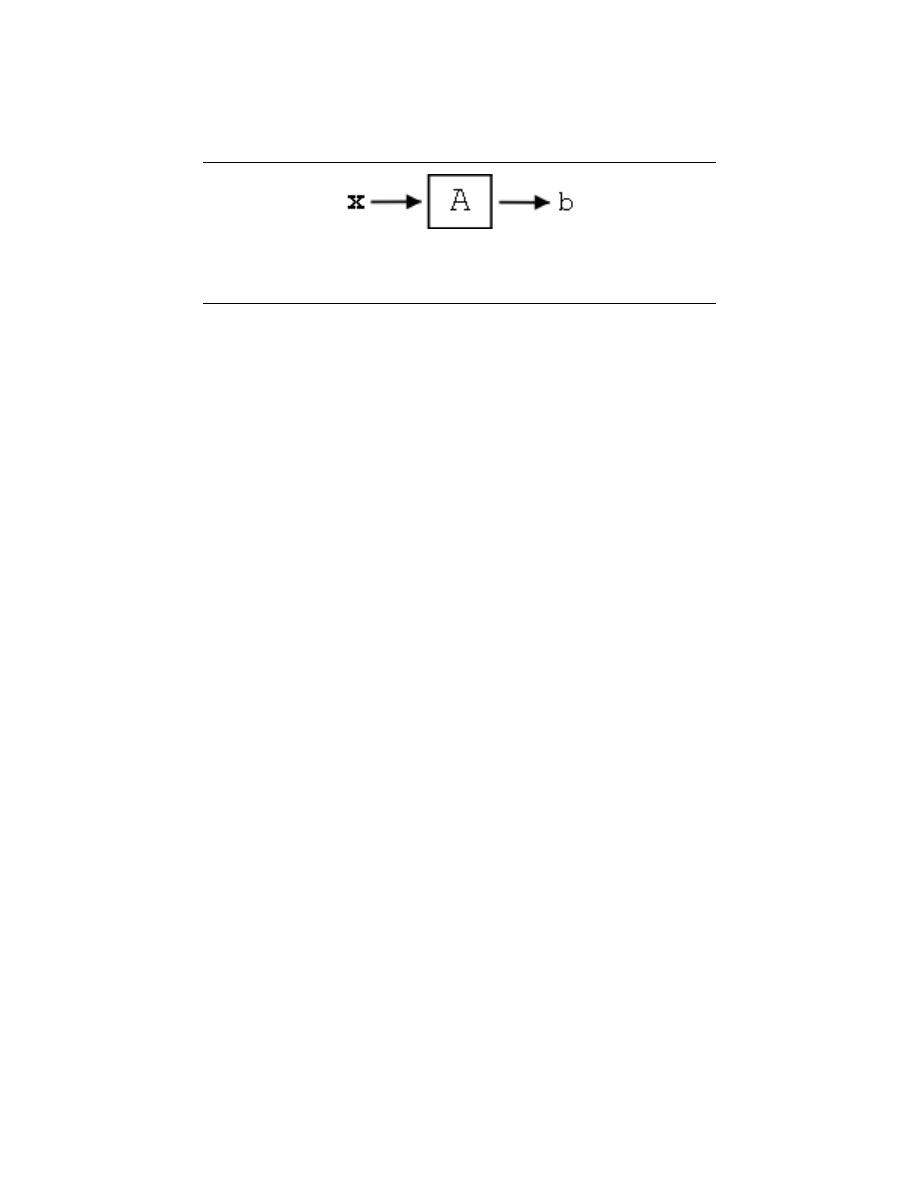

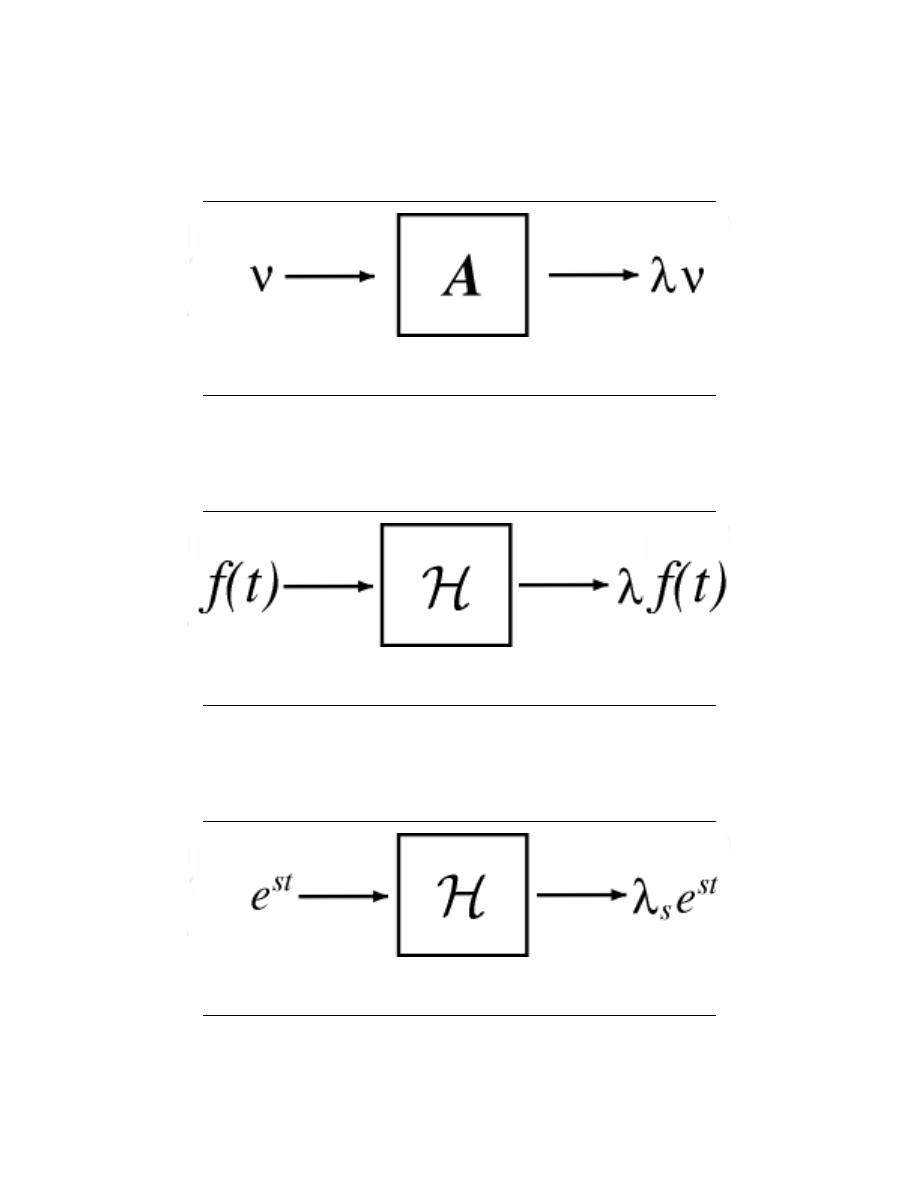

5.3 Eigenvectors and Eigenvalues . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

5.4 Matrix Diagonalization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76

5.5 Eigen-stuff in a Nutshell . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78

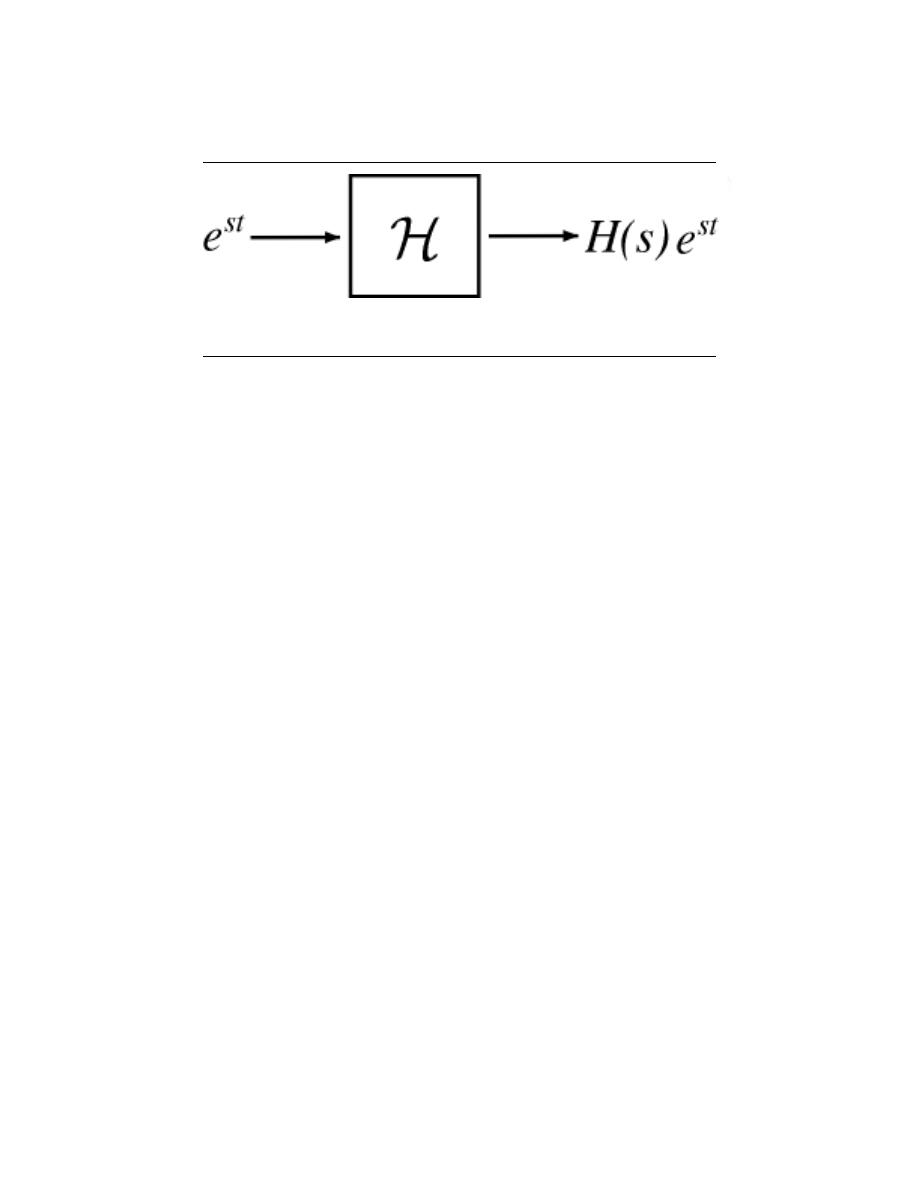

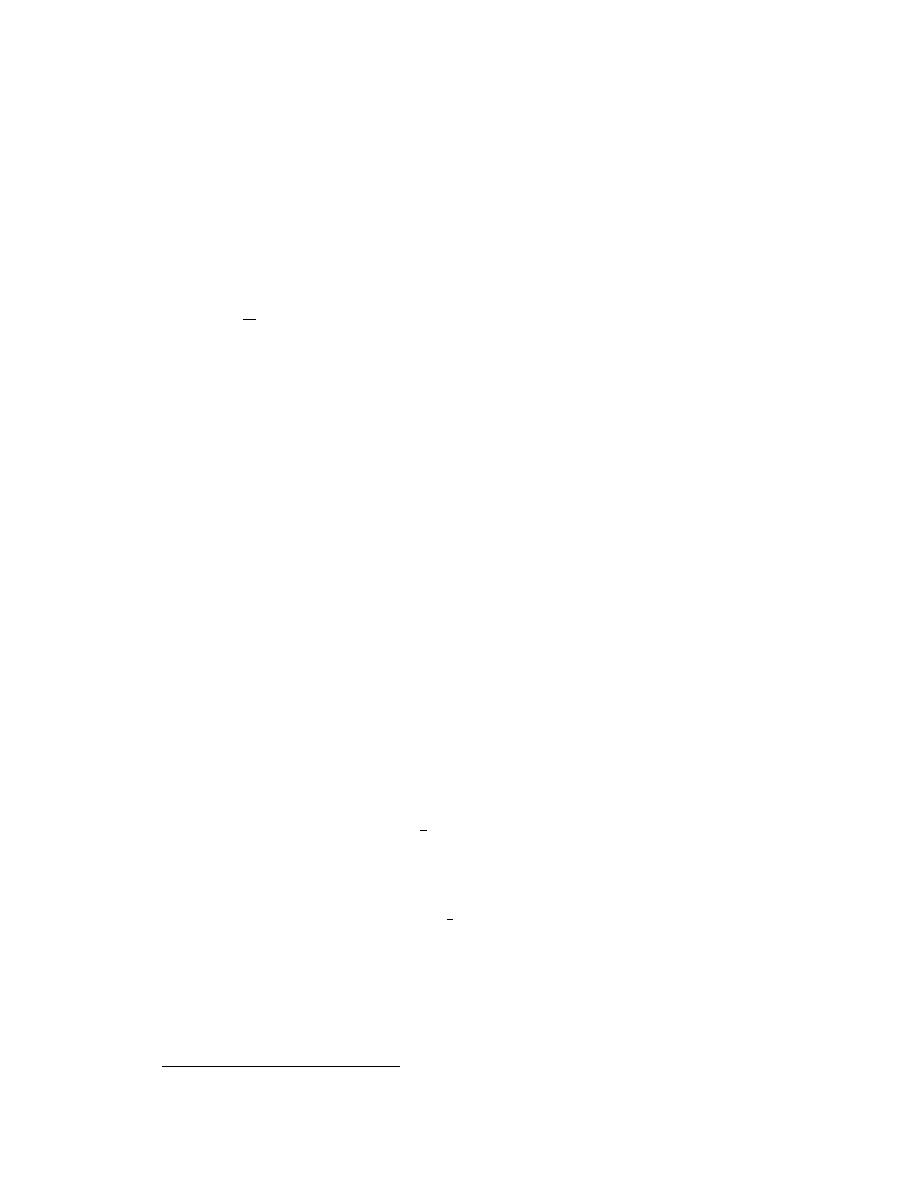

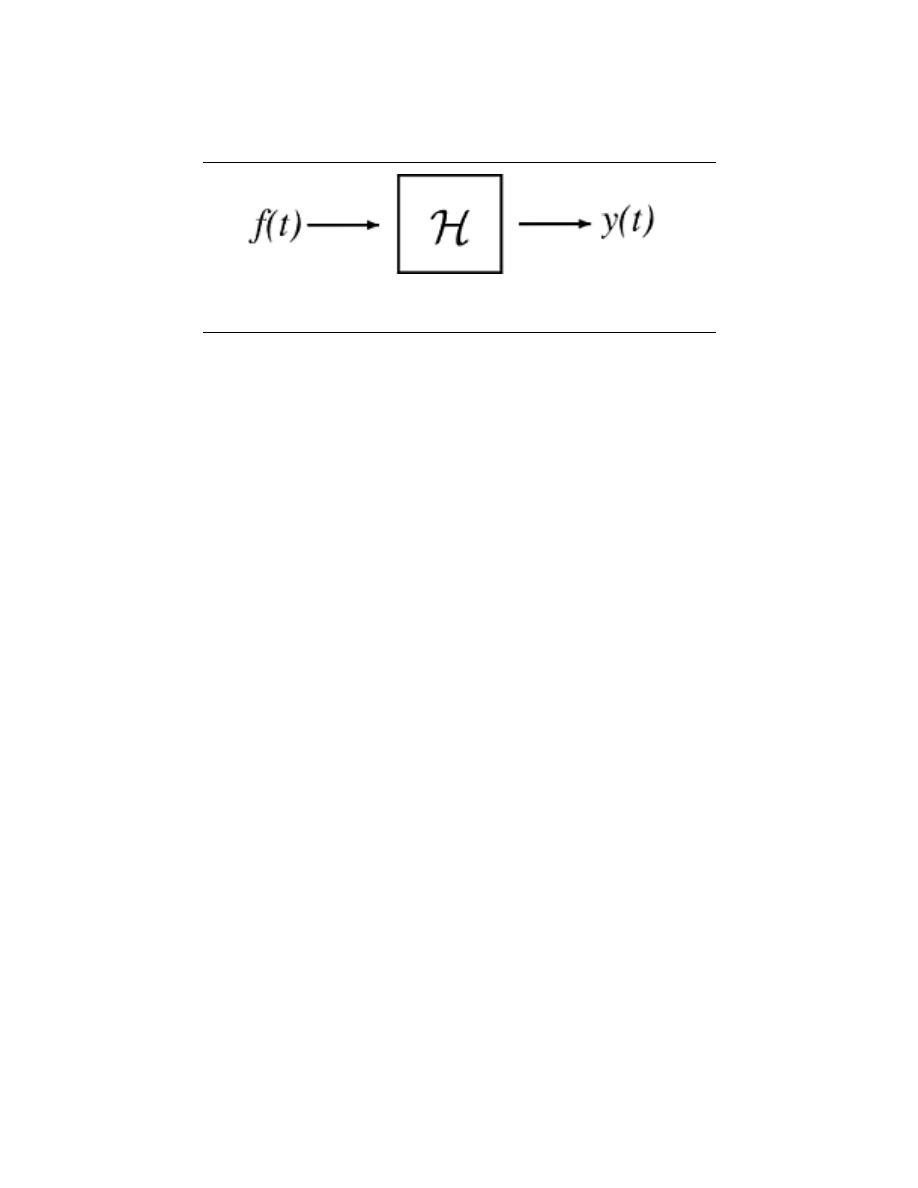

5.6 Eigenfunctions of LTI Systems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

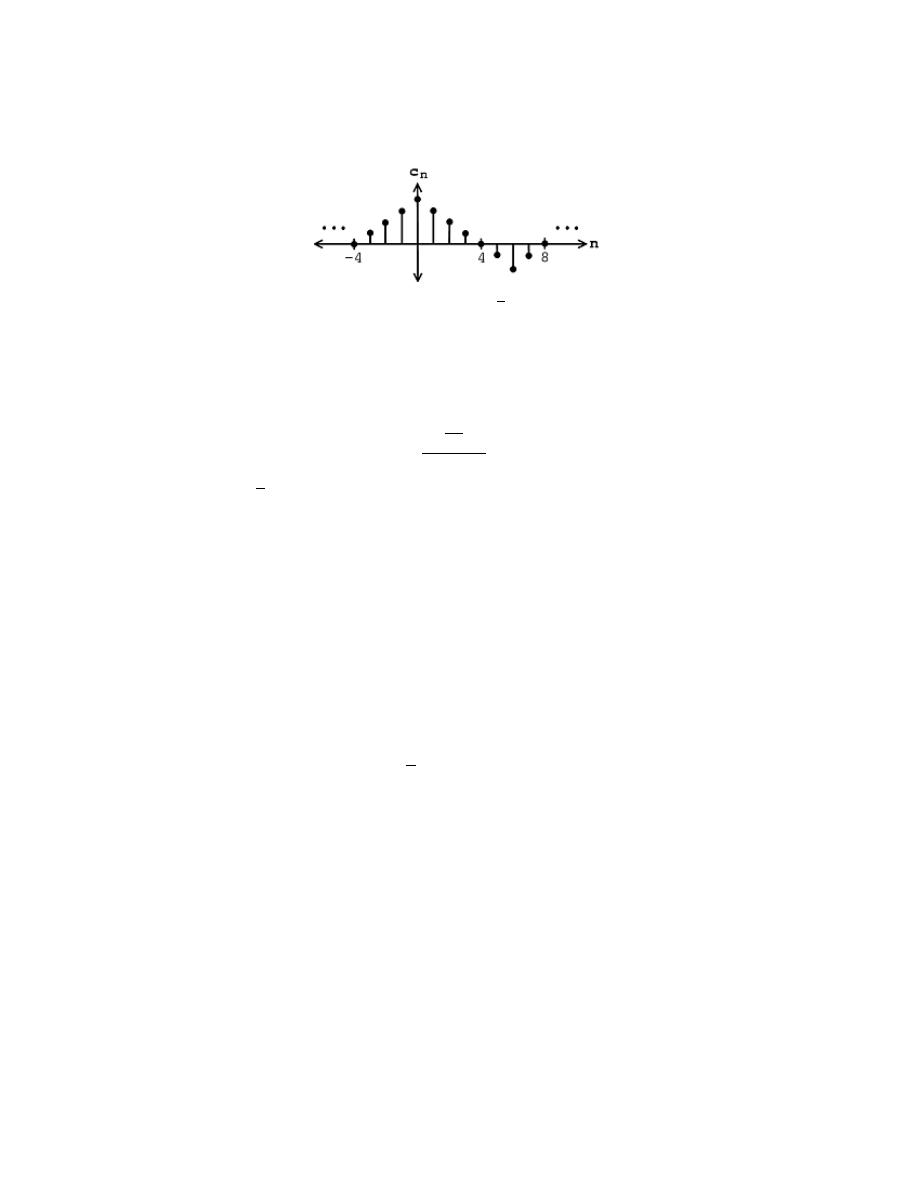

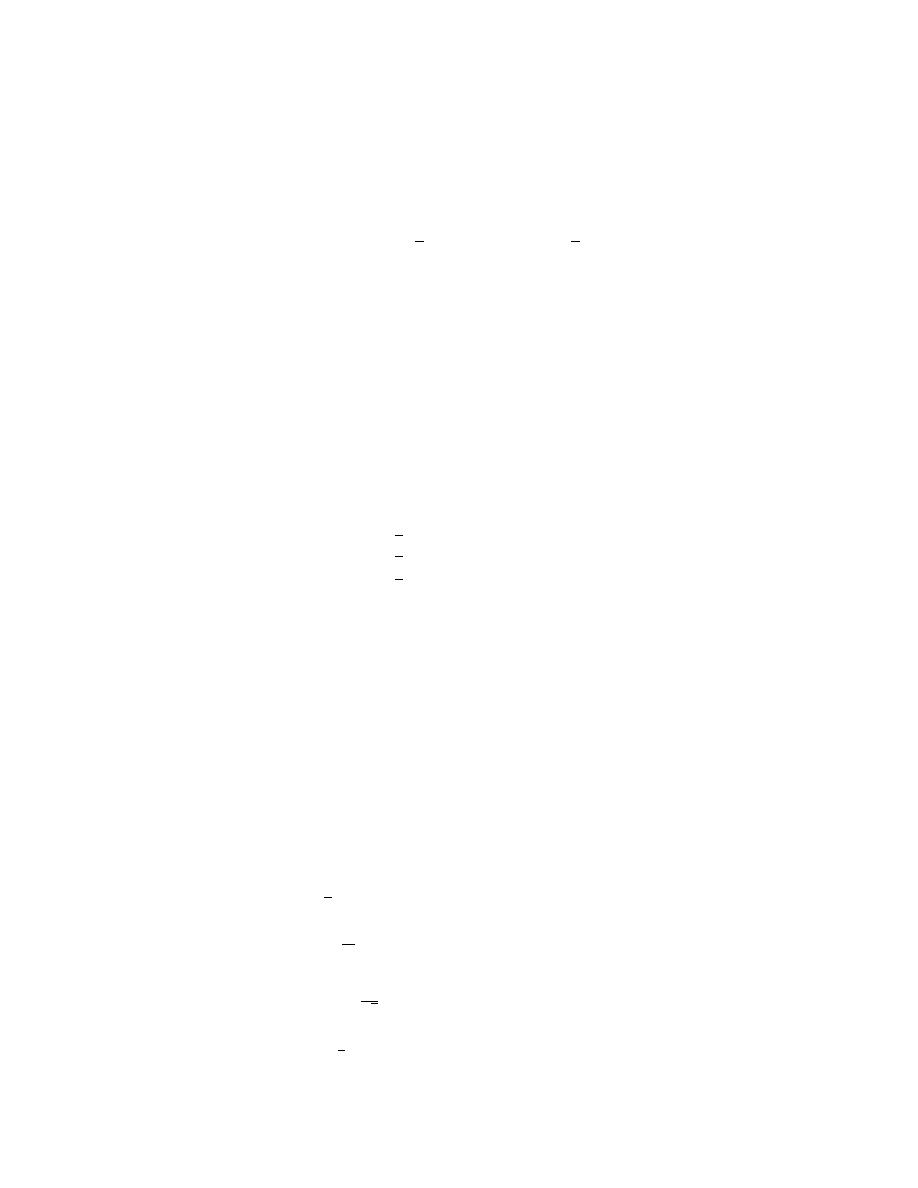

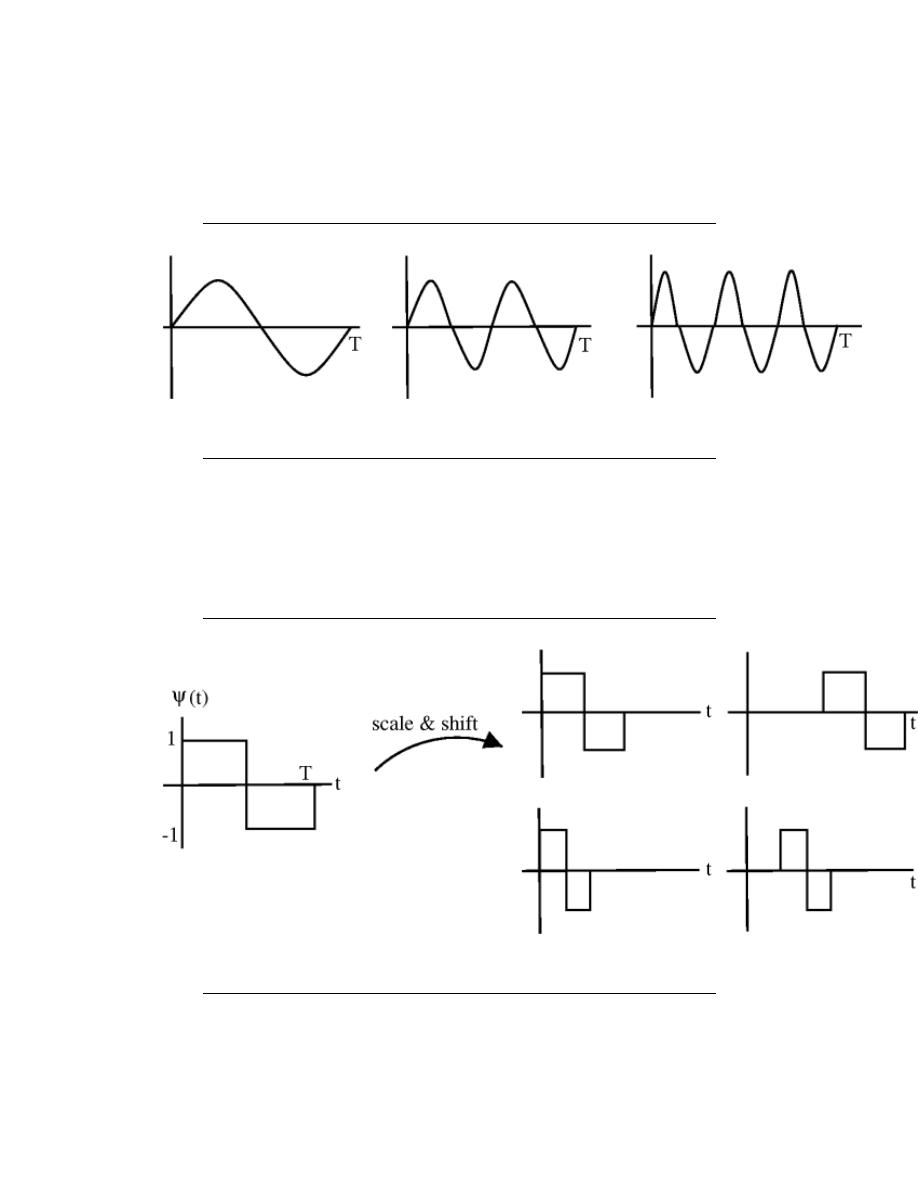

5 Fourier Series

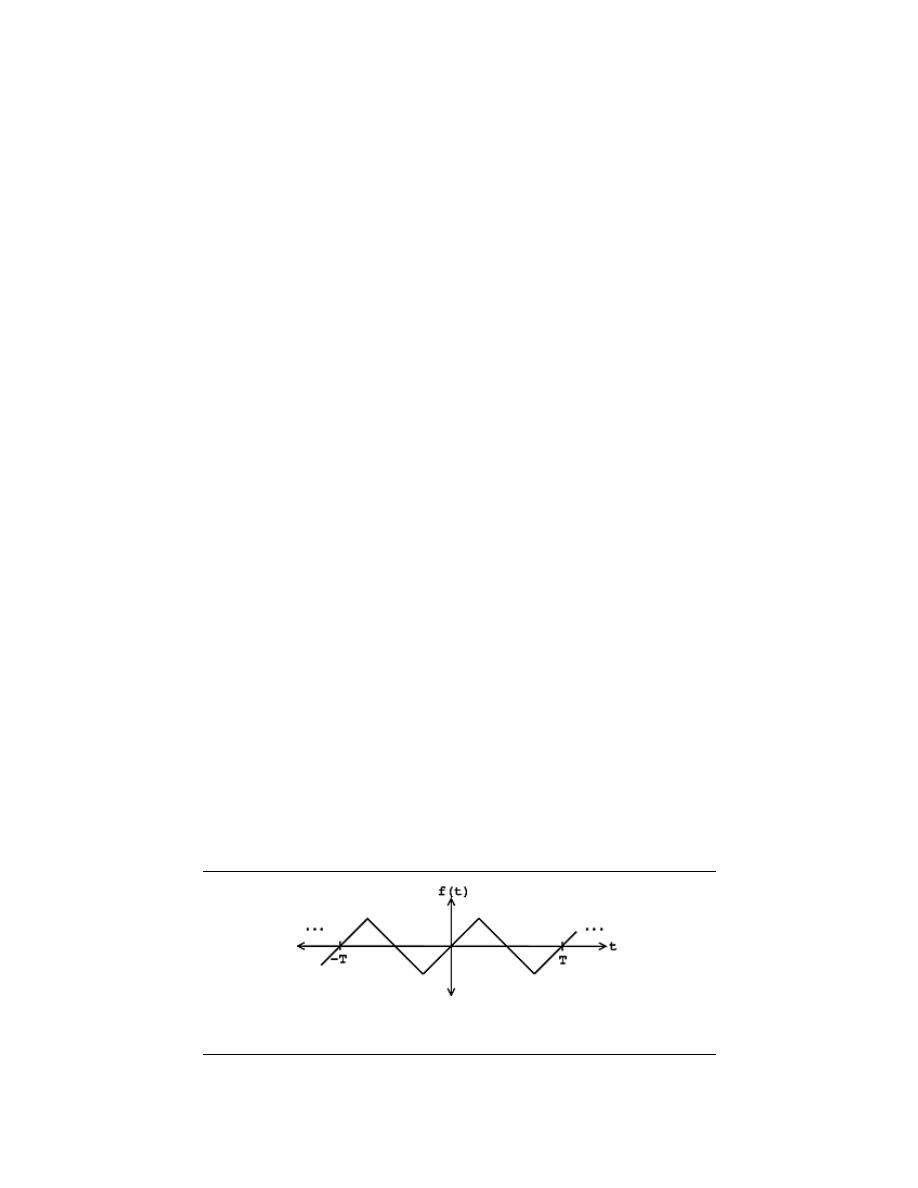

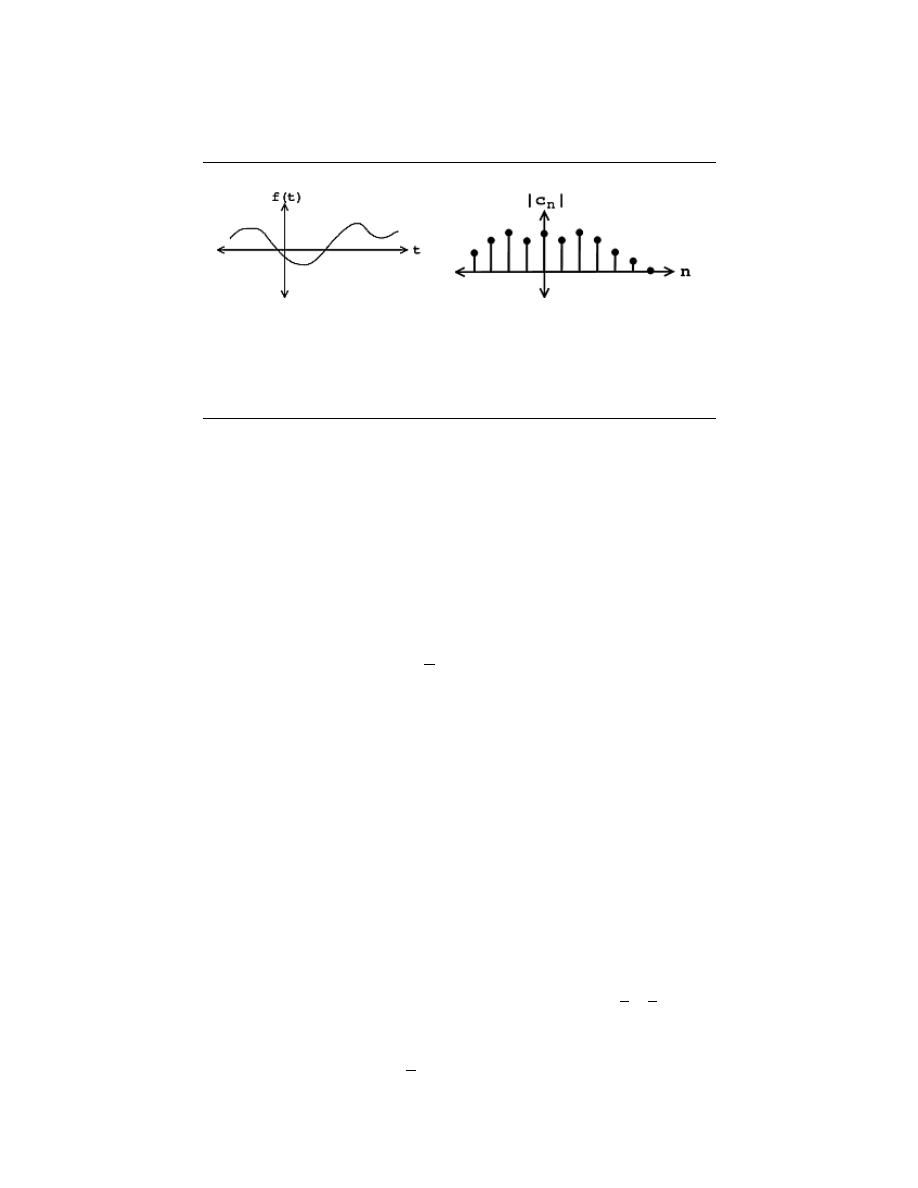

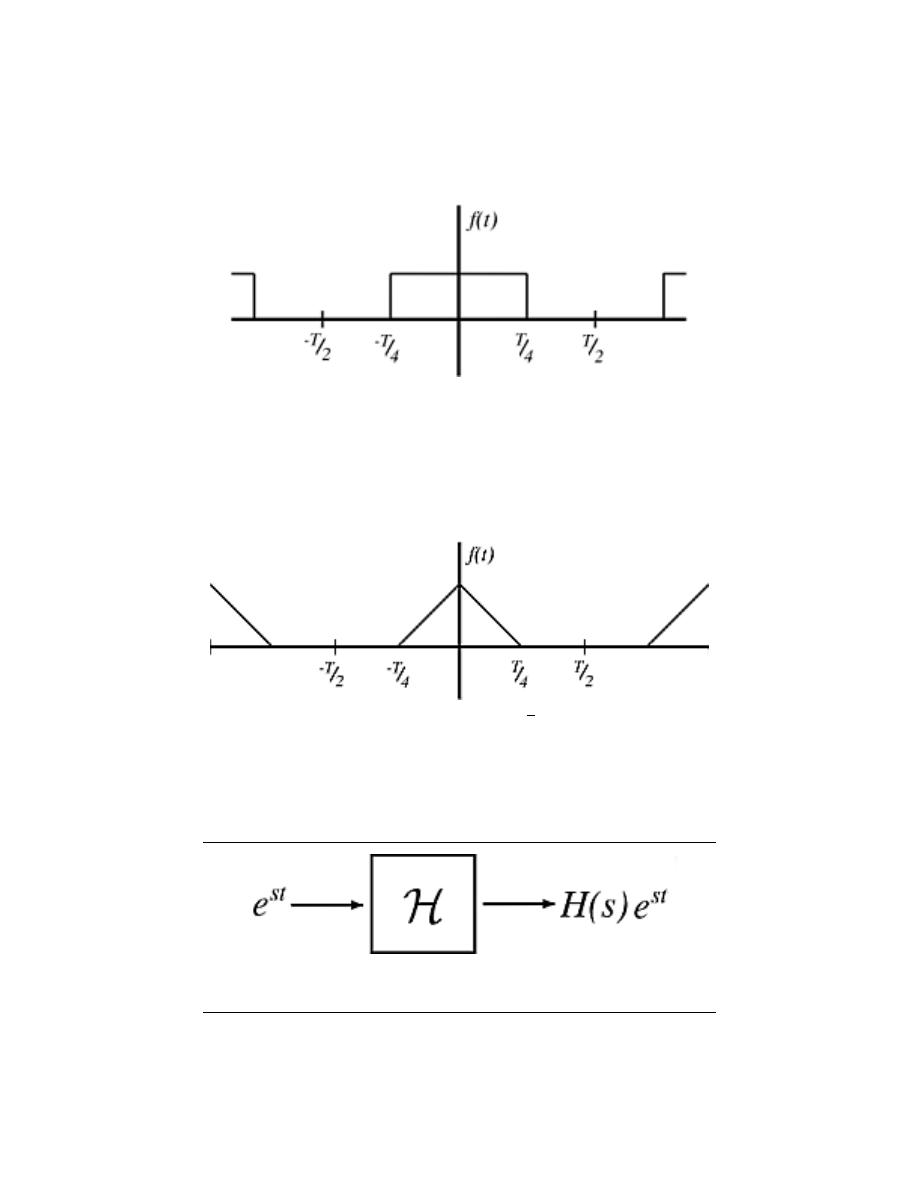

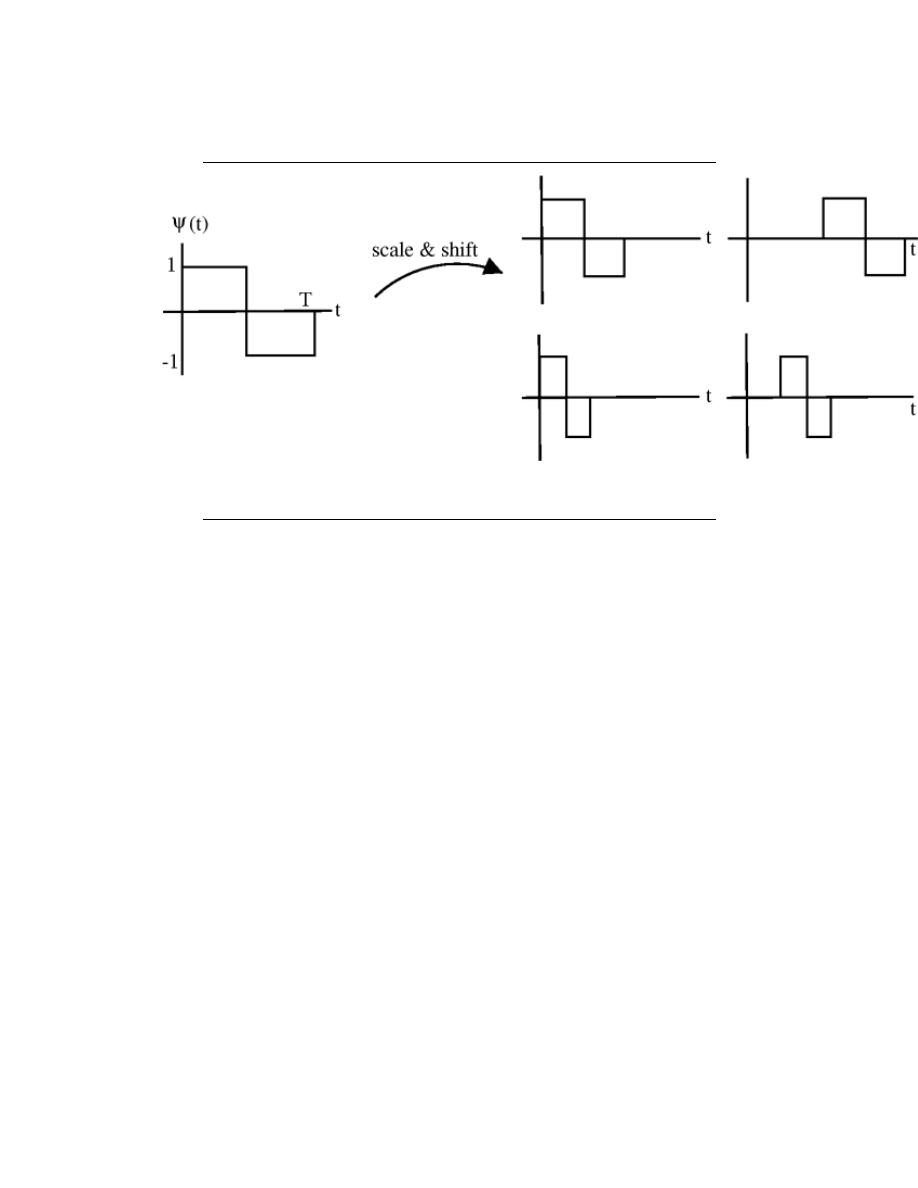

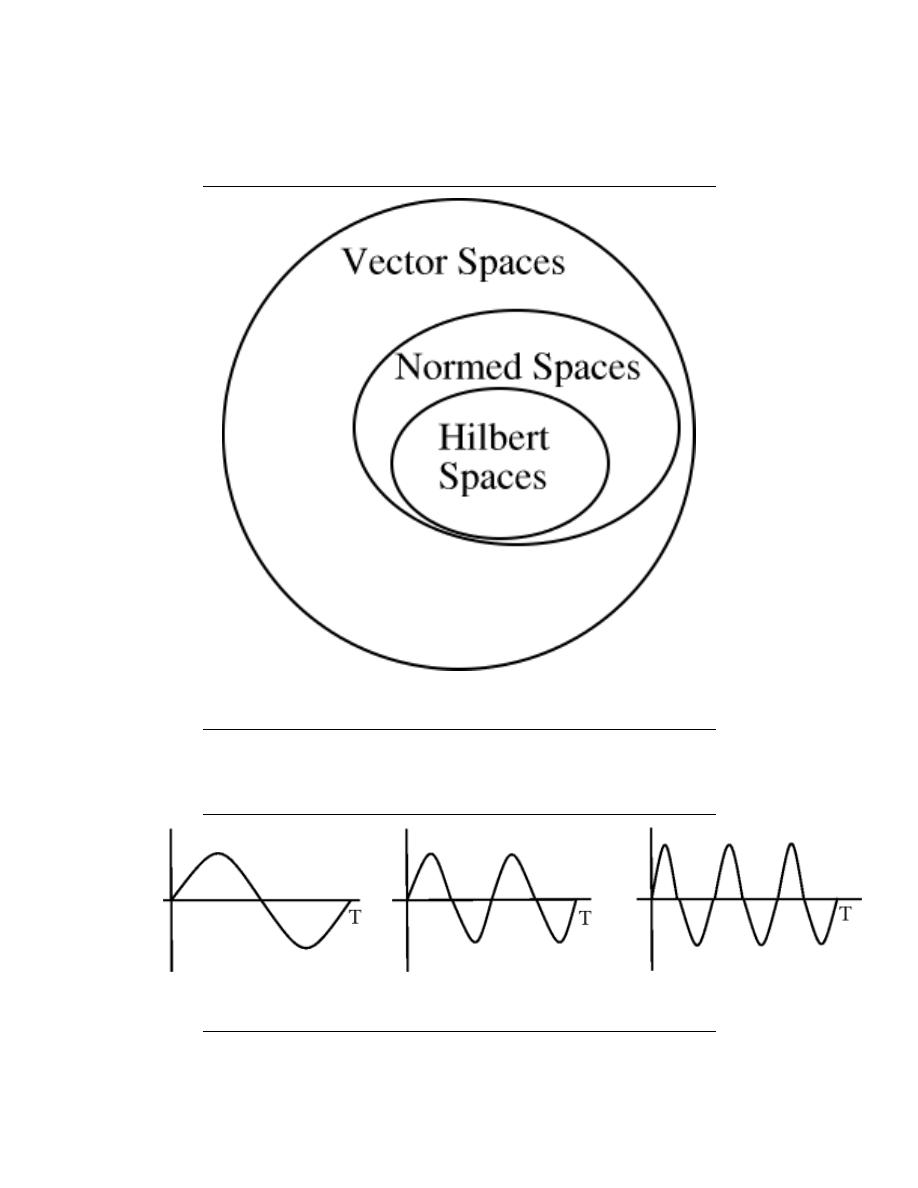

6.1 Periodic Signals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

6.2 Fourier Series: Eigenfunction Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

6.3 Derivation of Fourier Coefficients Equation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88

6.4 Fourier Series in a Nutshell . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

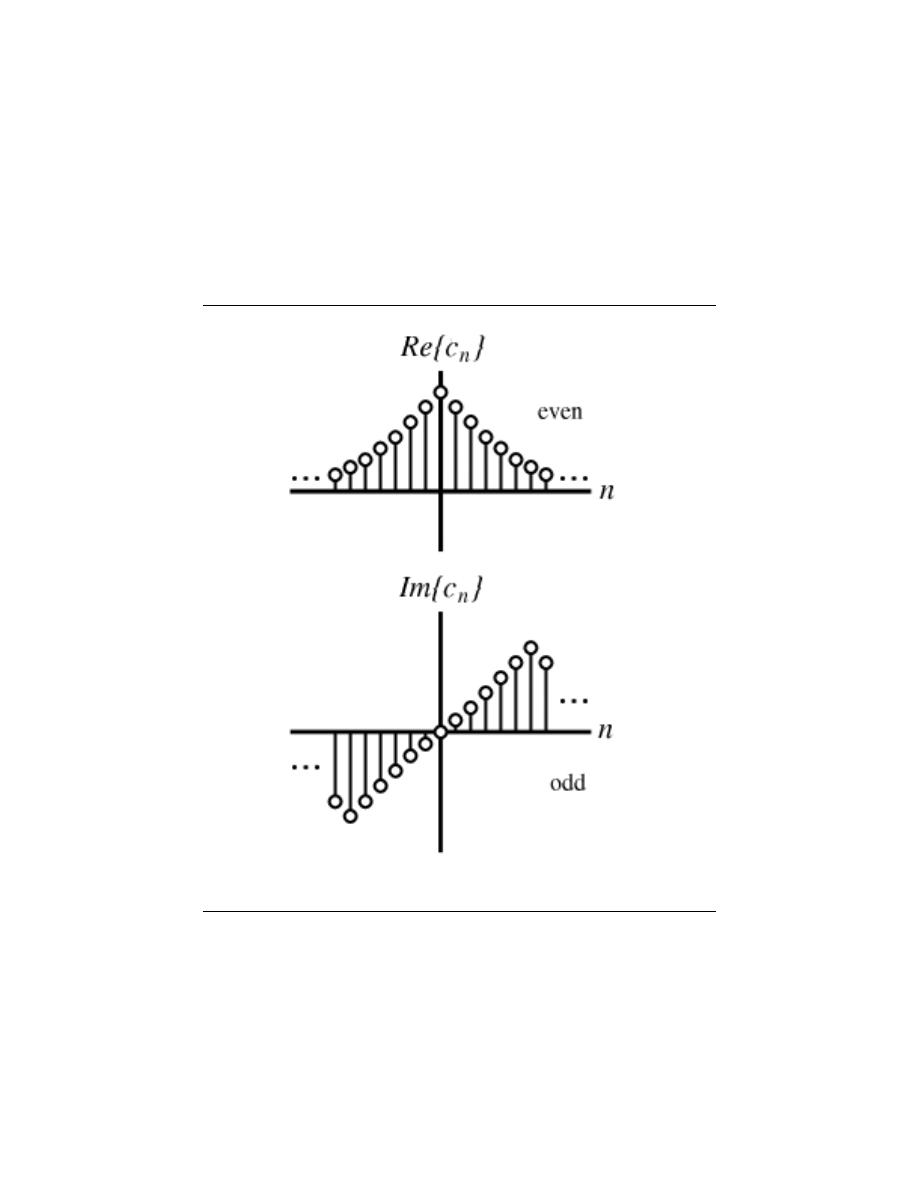

6.5 Fourier Series Properties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

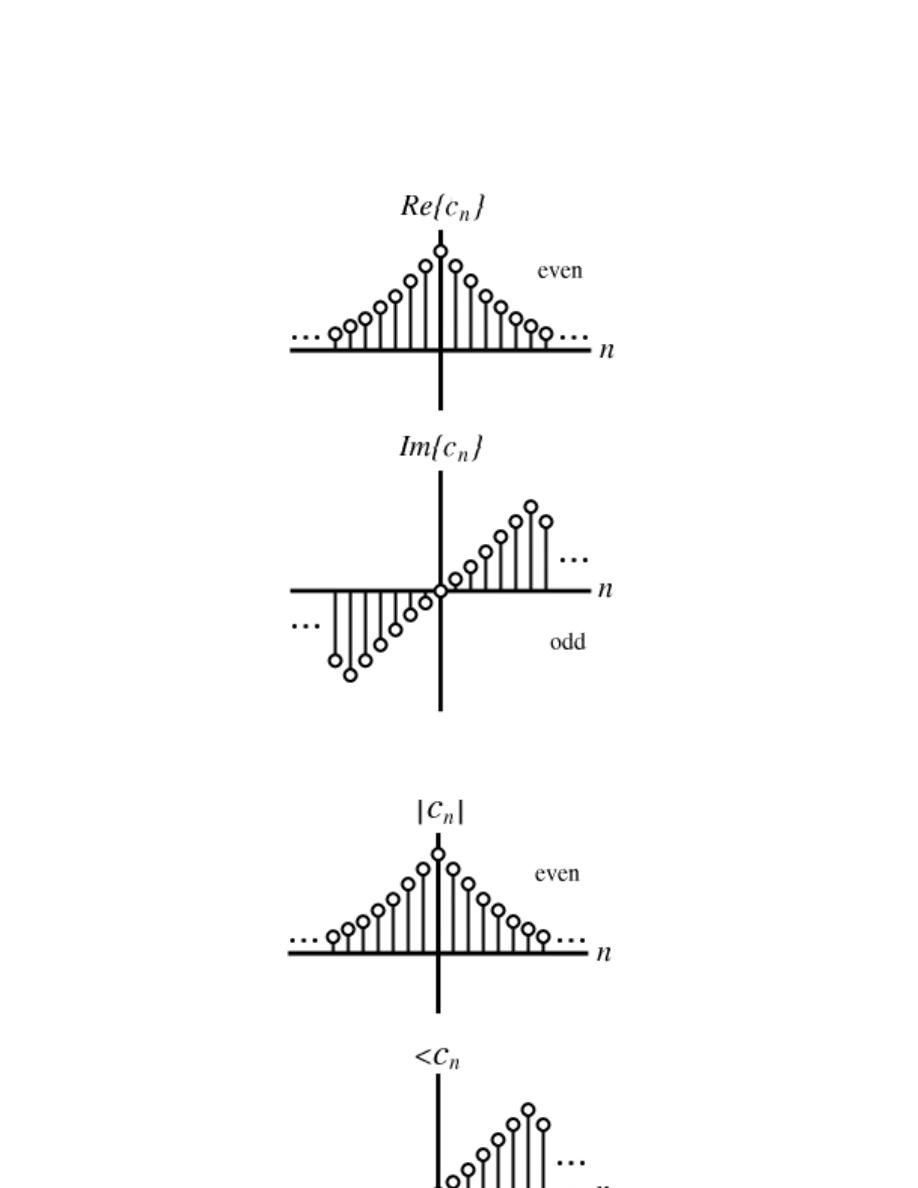

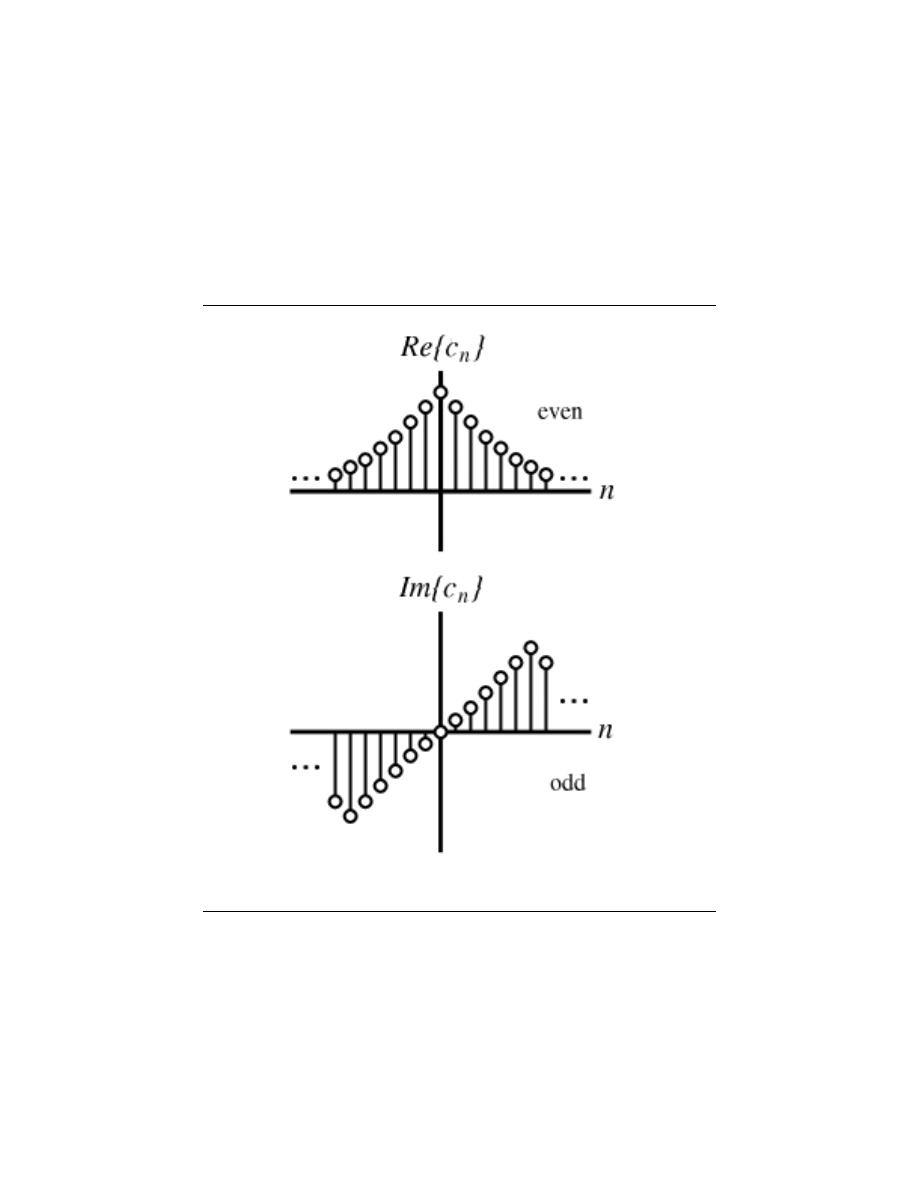

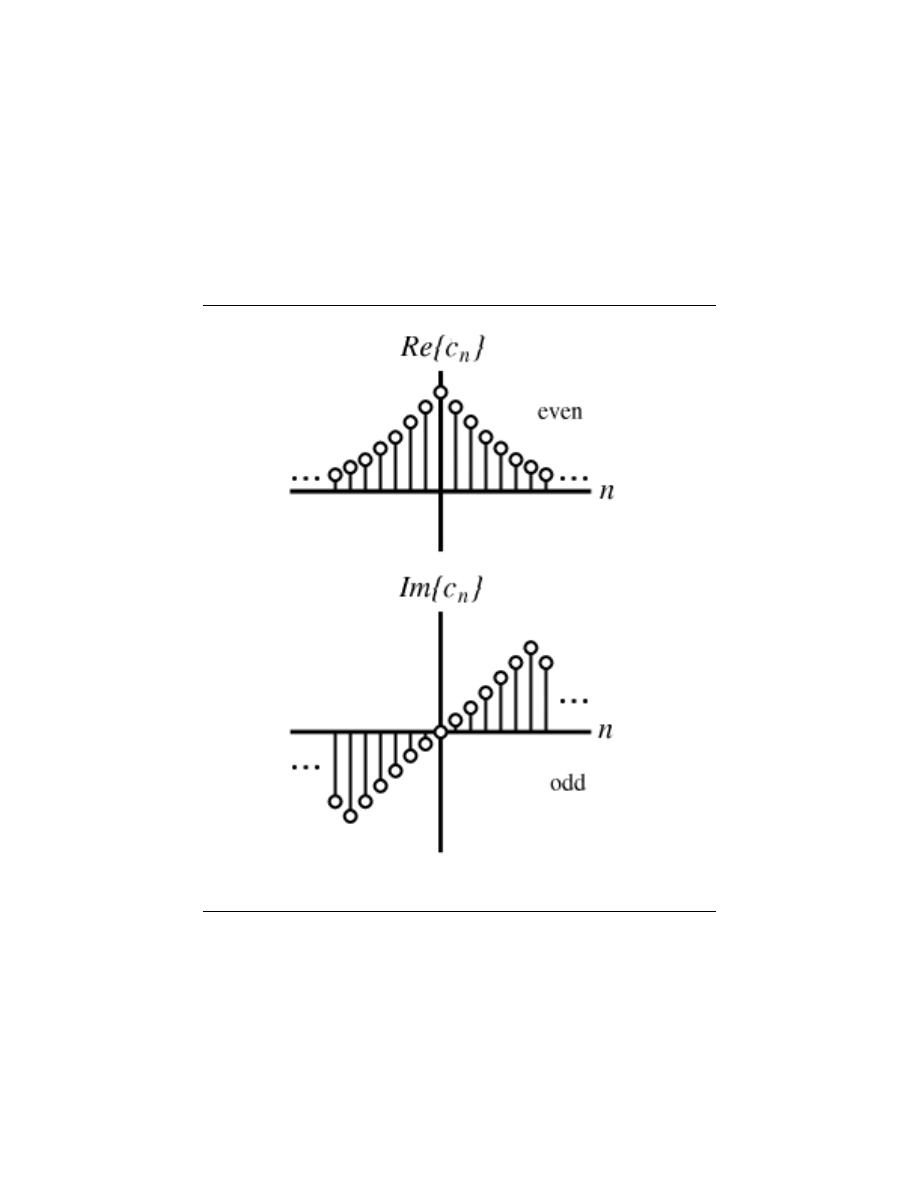

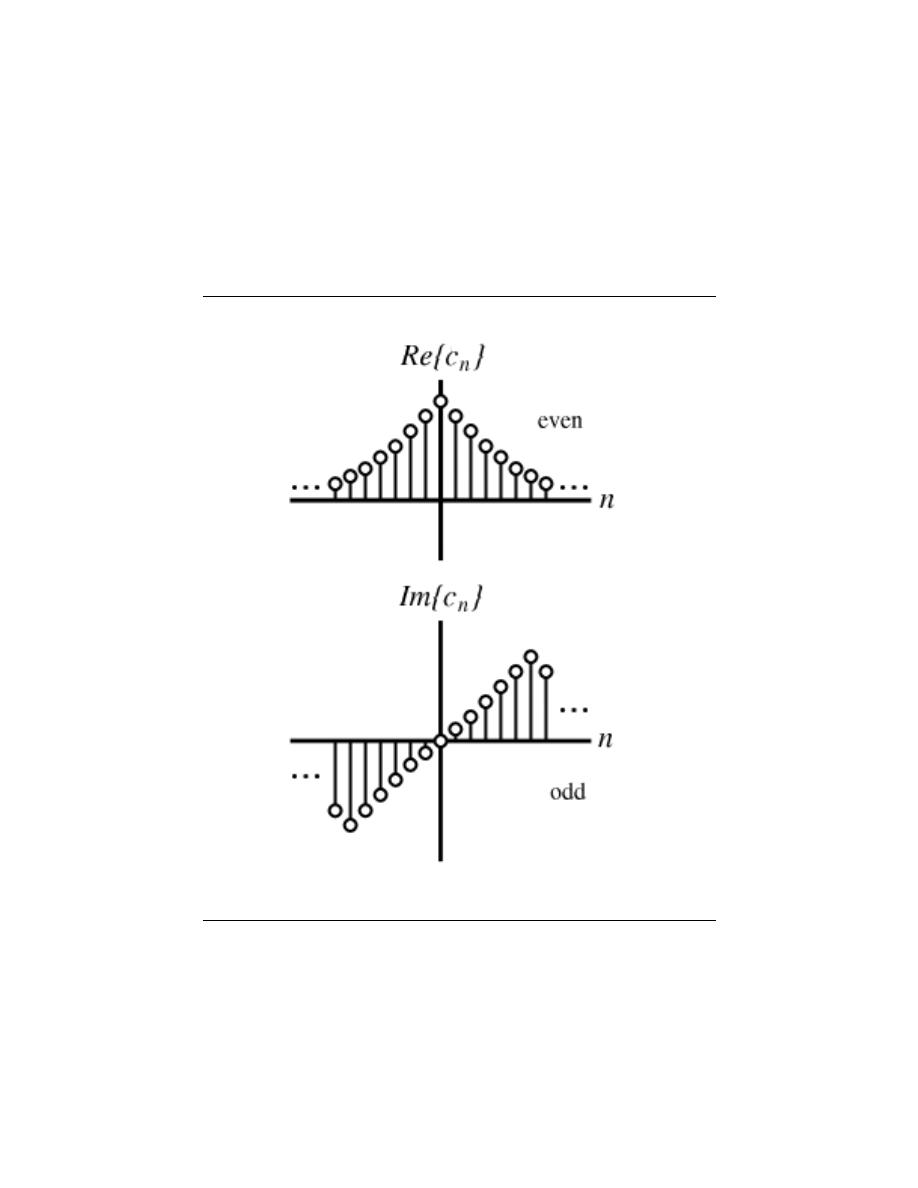

6.6 Symmetry Properties of the Fourier Series . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

6.7 Circular Convolution Property of Fourier Series . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

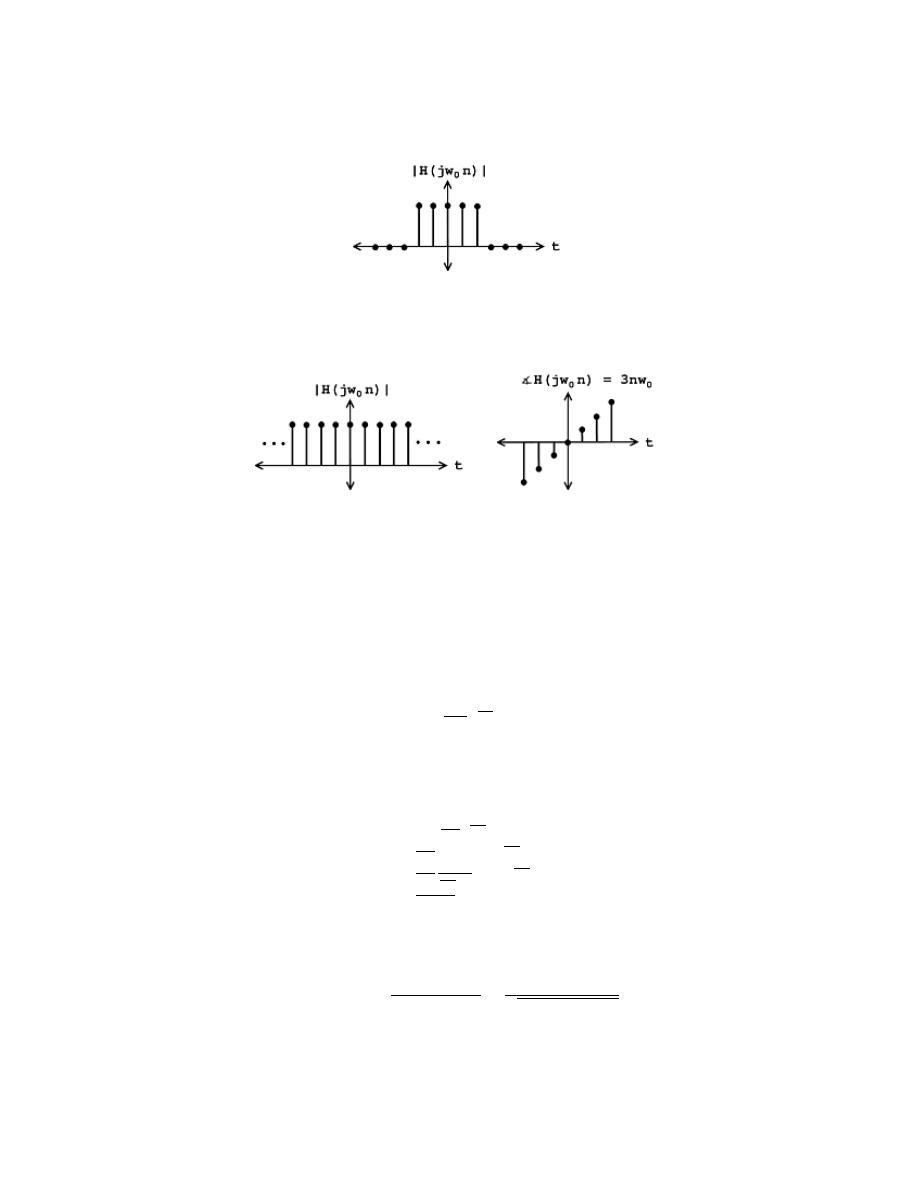

6.8 Fourier Series and LTI Systems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102

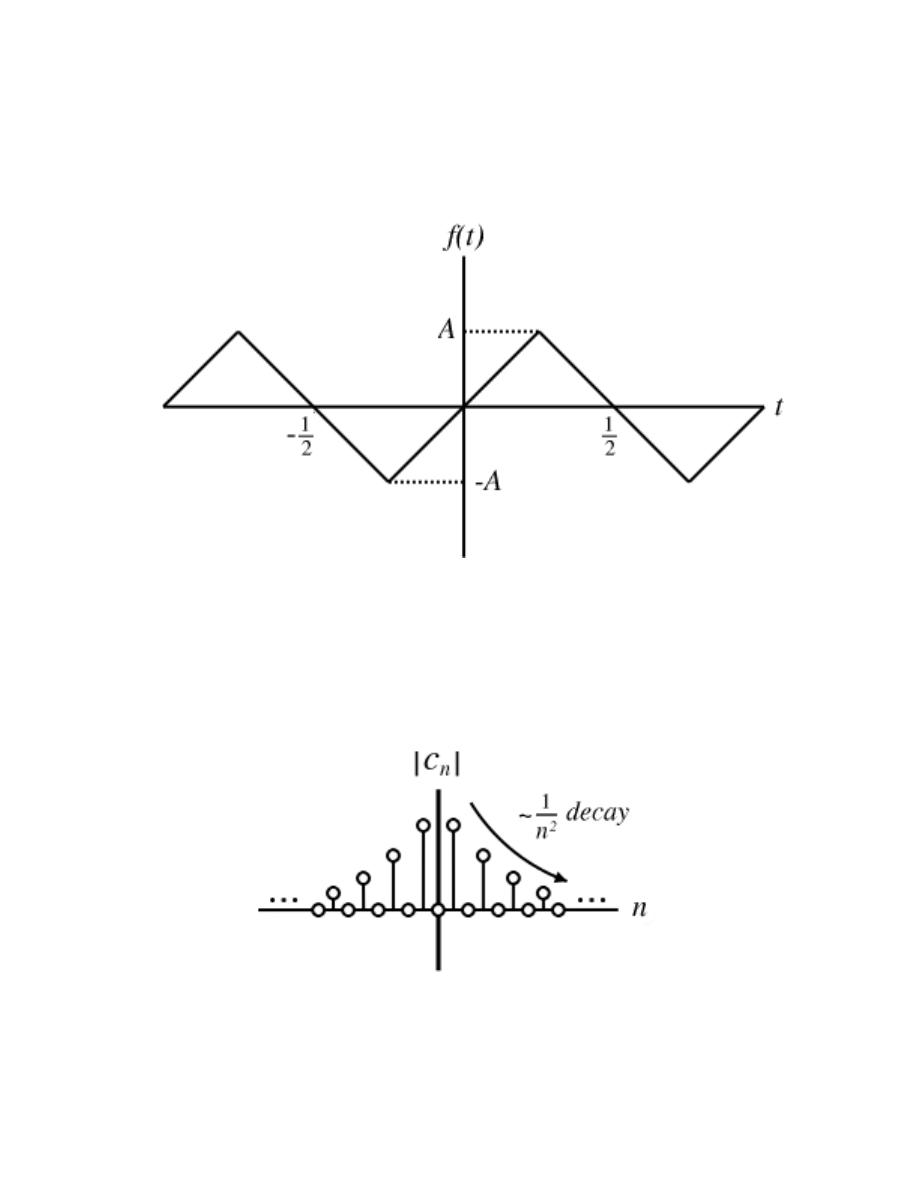

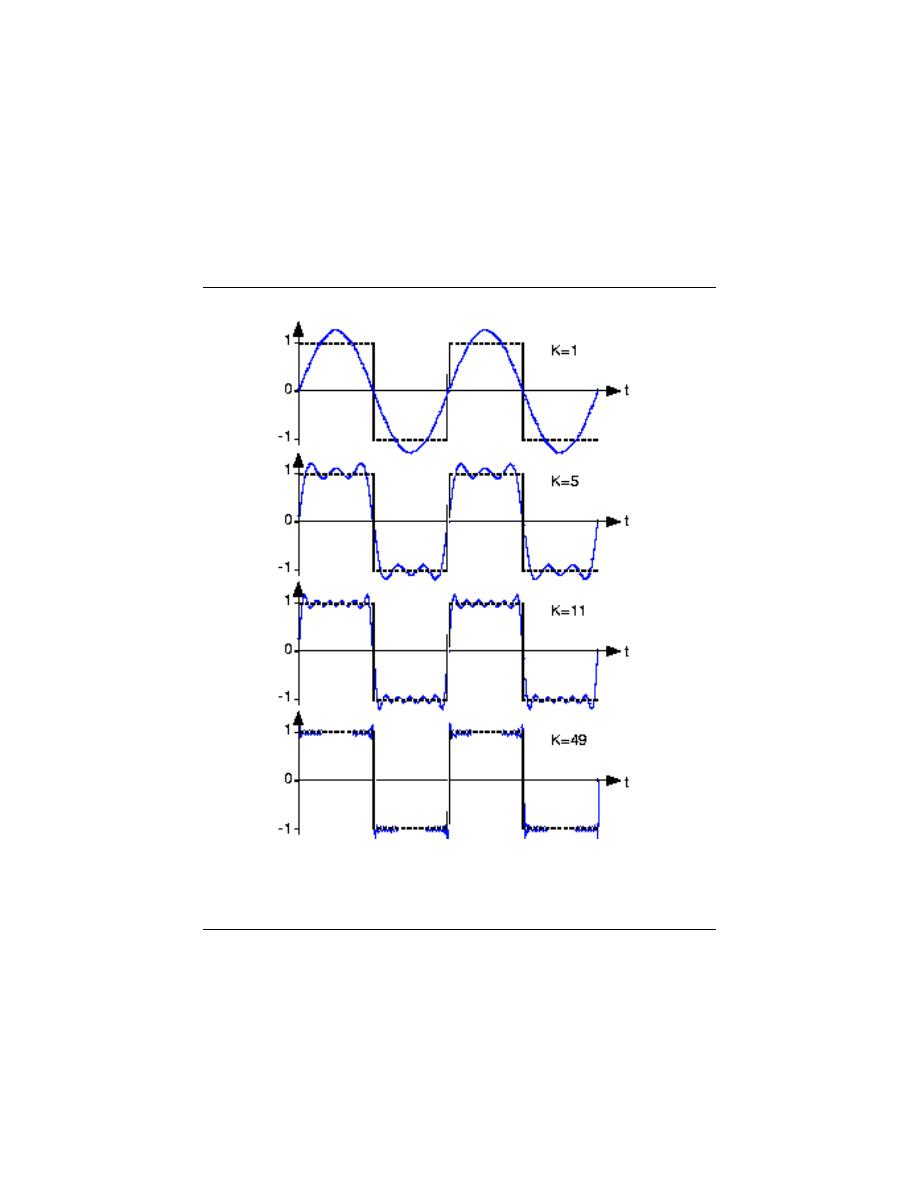

6.9 Convergence of Fourier Series . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 104

6.10 Dirichlet Conditions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

6.11 Gibbs’s Phenomena . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108

6.12 Fourier Series Wrap-Up . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111

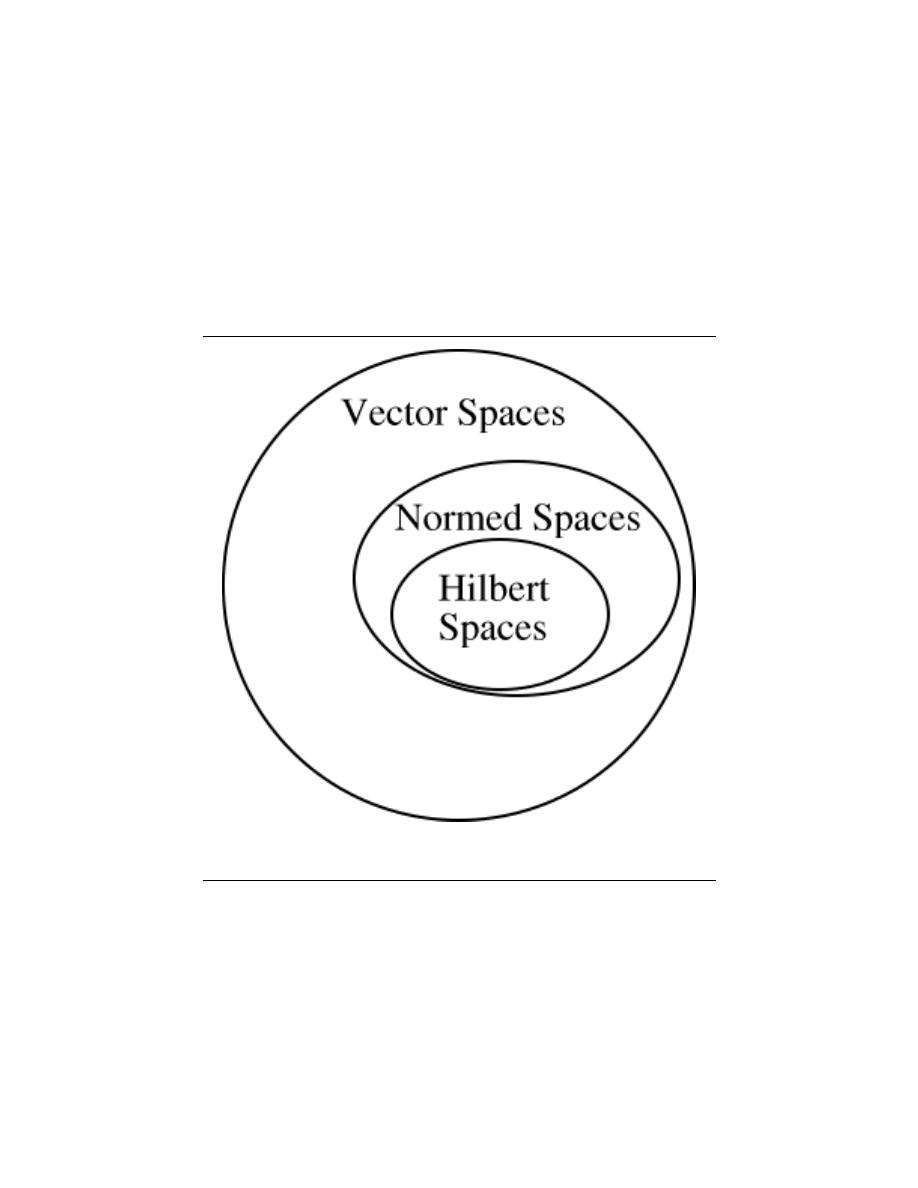

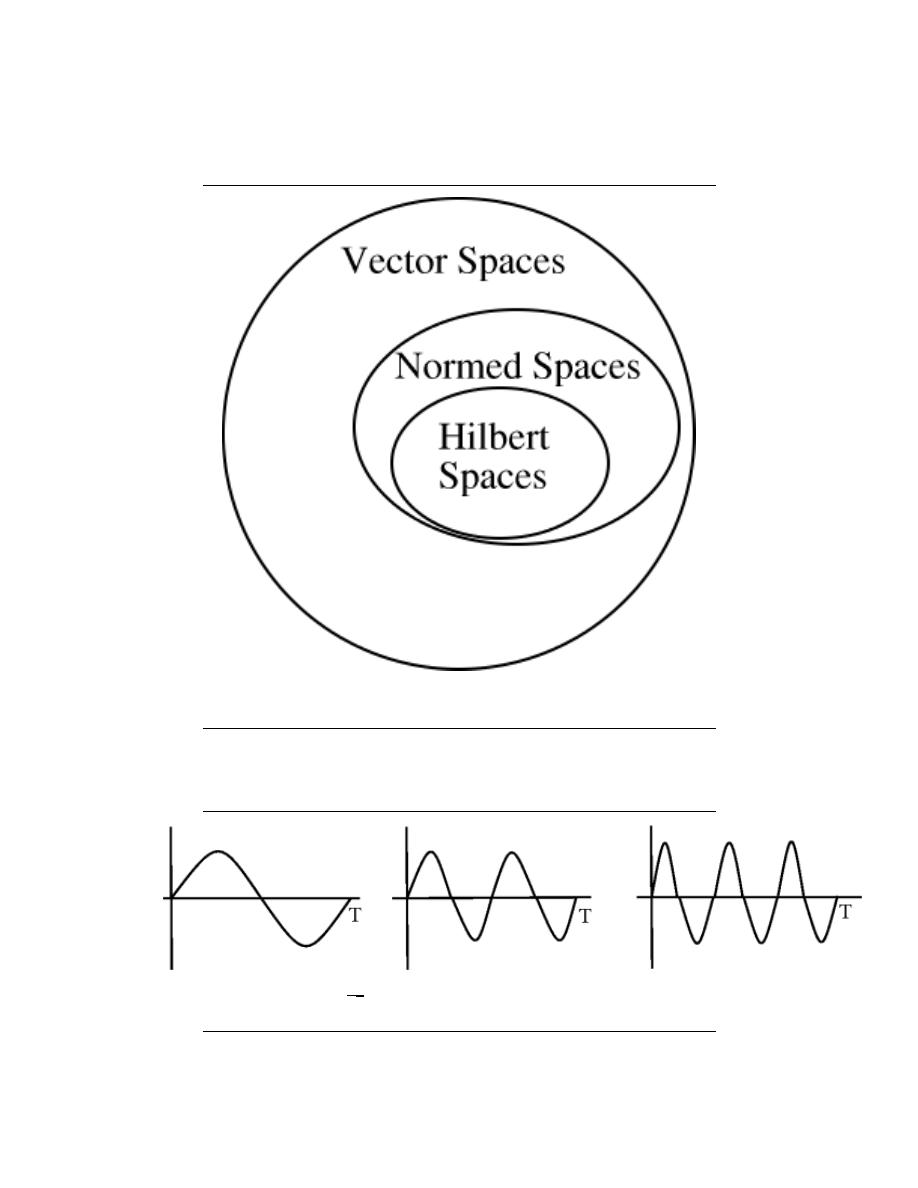

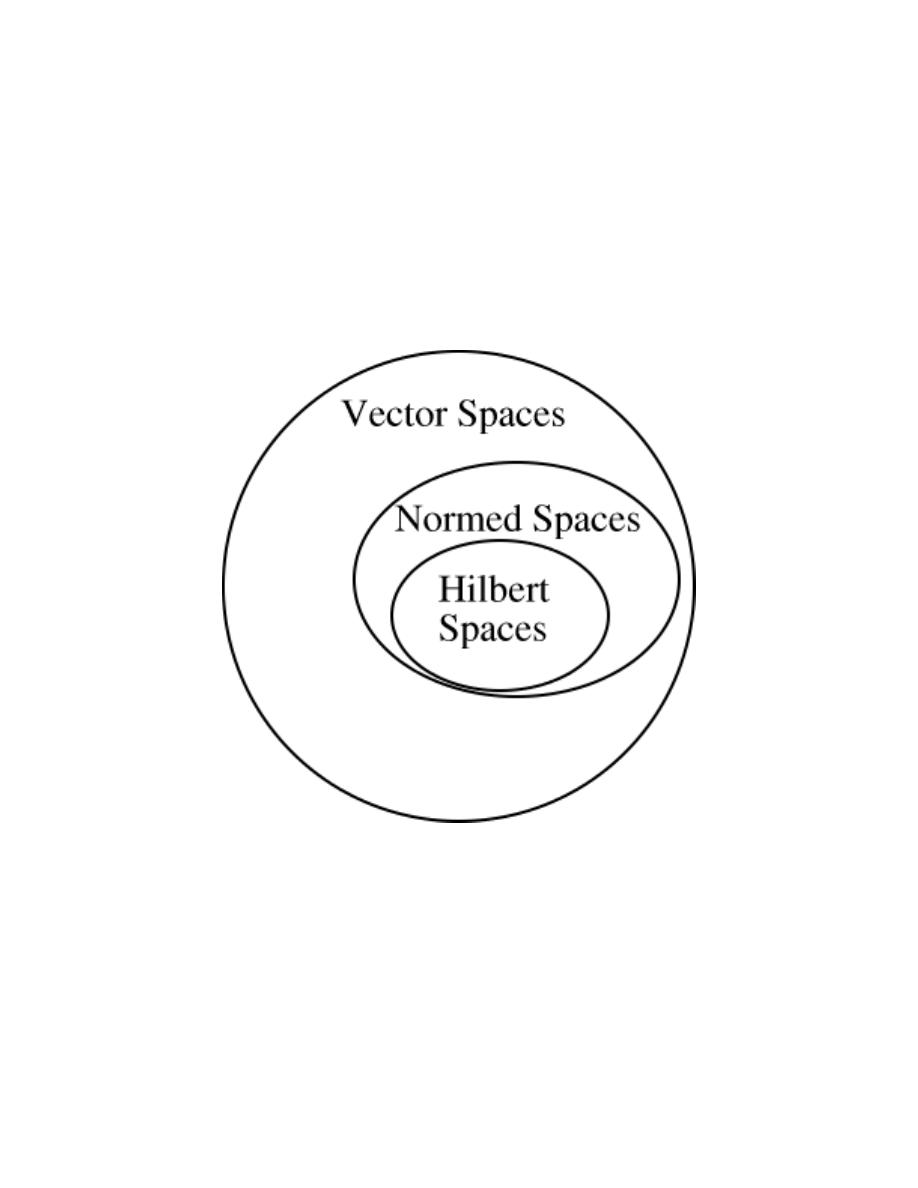

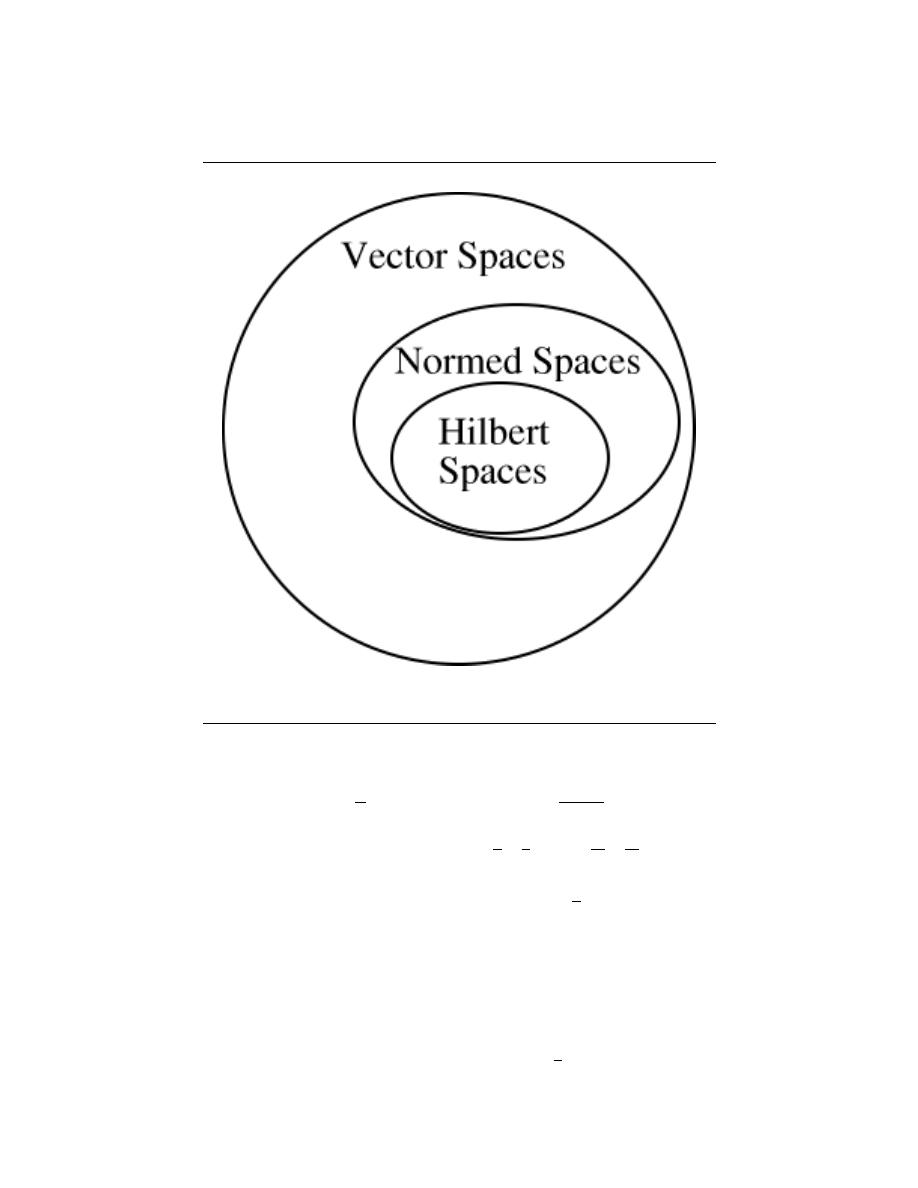

6 Hilbert Spaces and Orthogonal Expansions

7.1 Vector Spaces . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113

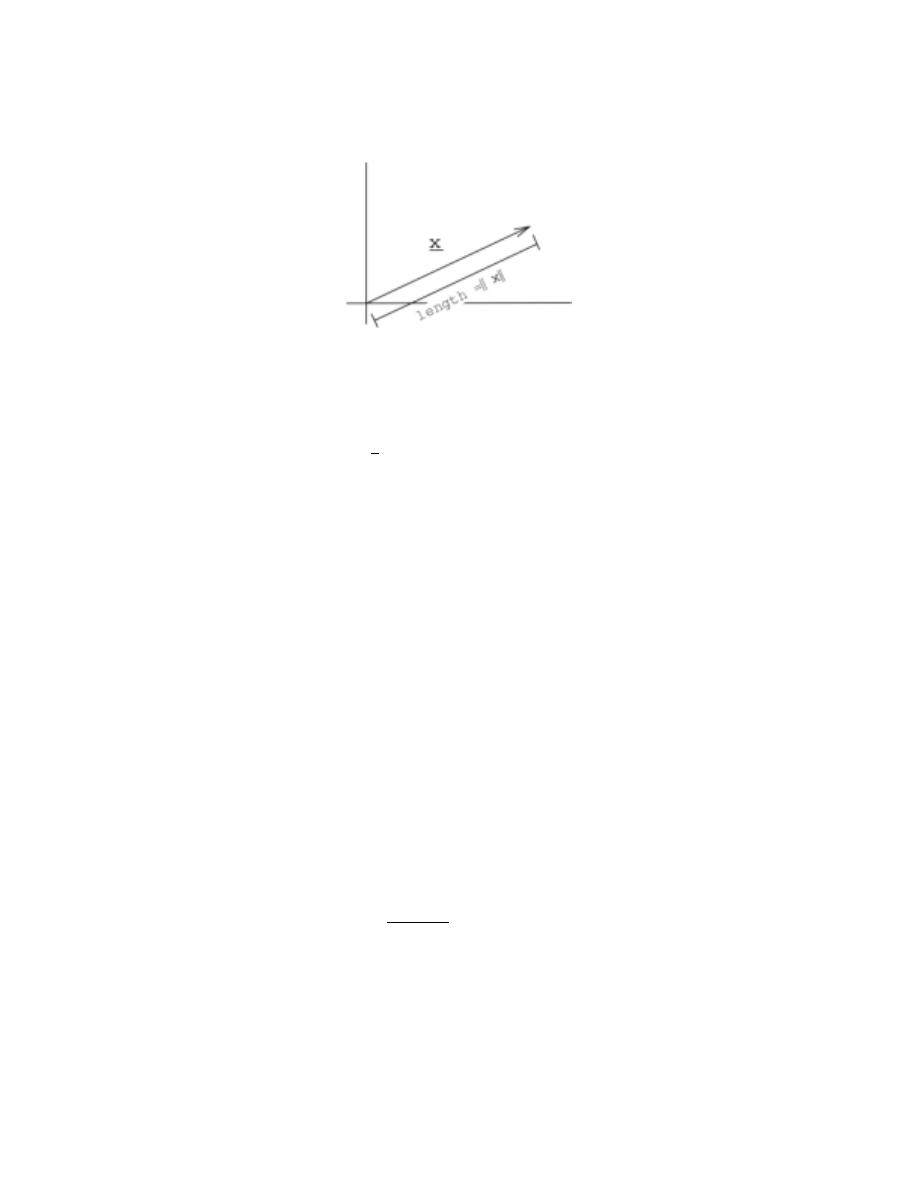

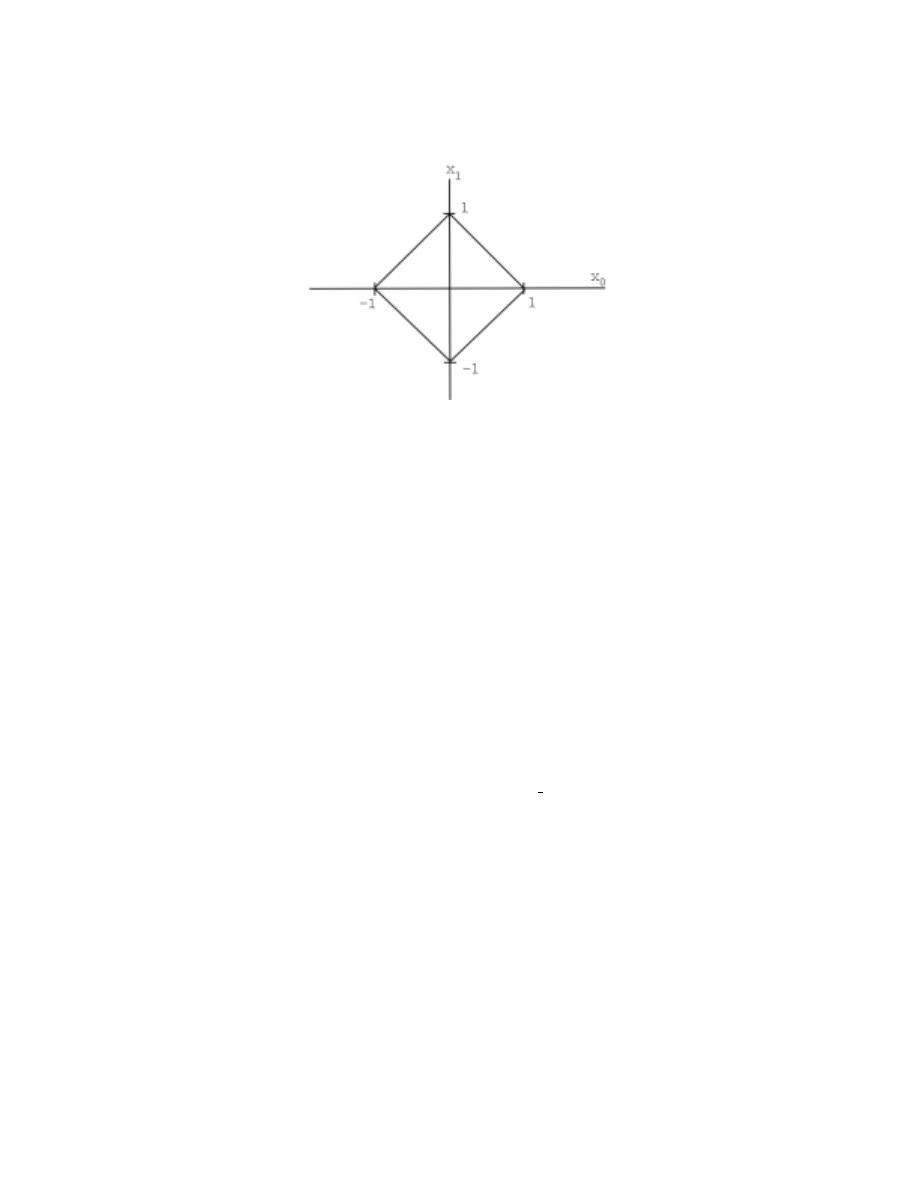

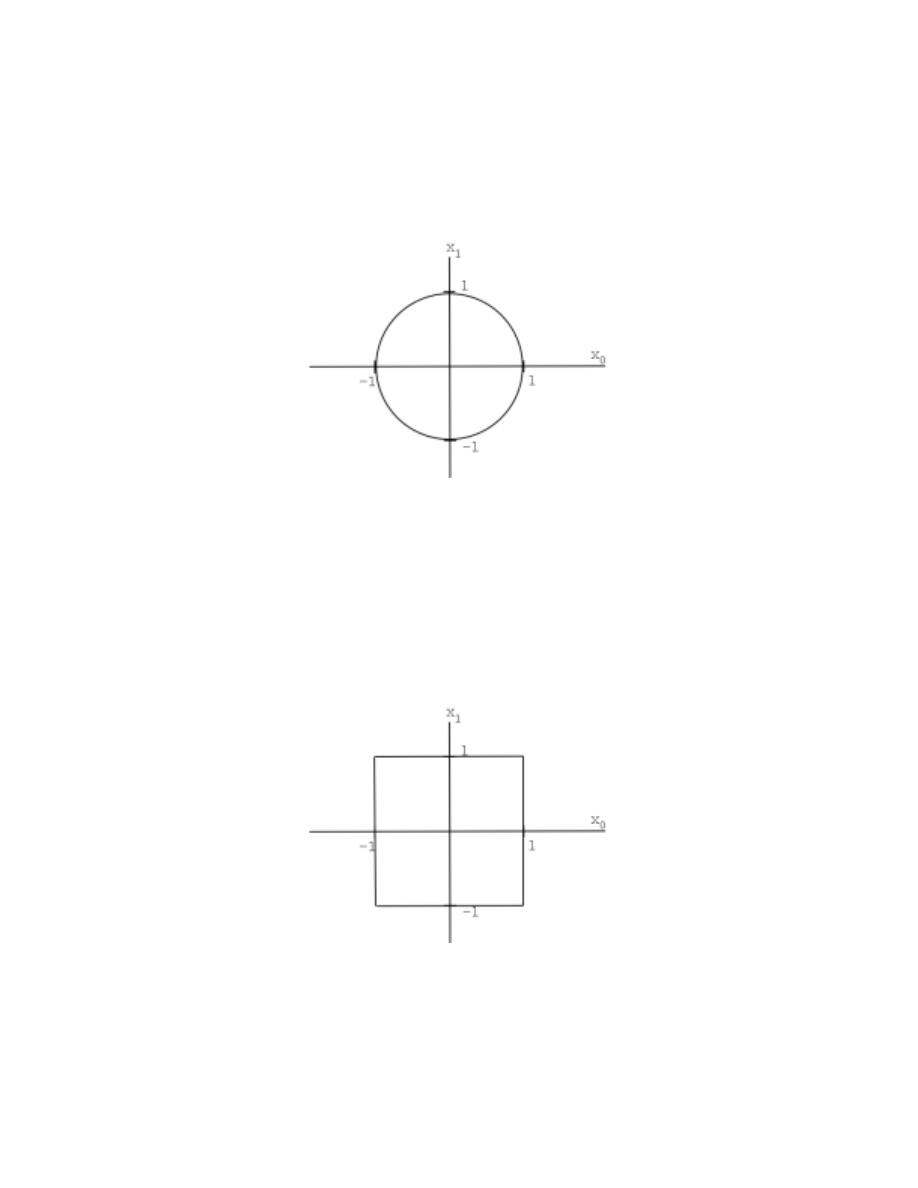

7.2 Norms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115

7.3 Inner Products . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 118

7.4 Hilbert Spaces . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 120

7.5 Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 120

7.6 Common Hilbert Spaces . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .128

7.7 Types of Basis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 131

iv

7.8 Orthonormal Basis Expansions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 135

7.9 Function Space . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 139

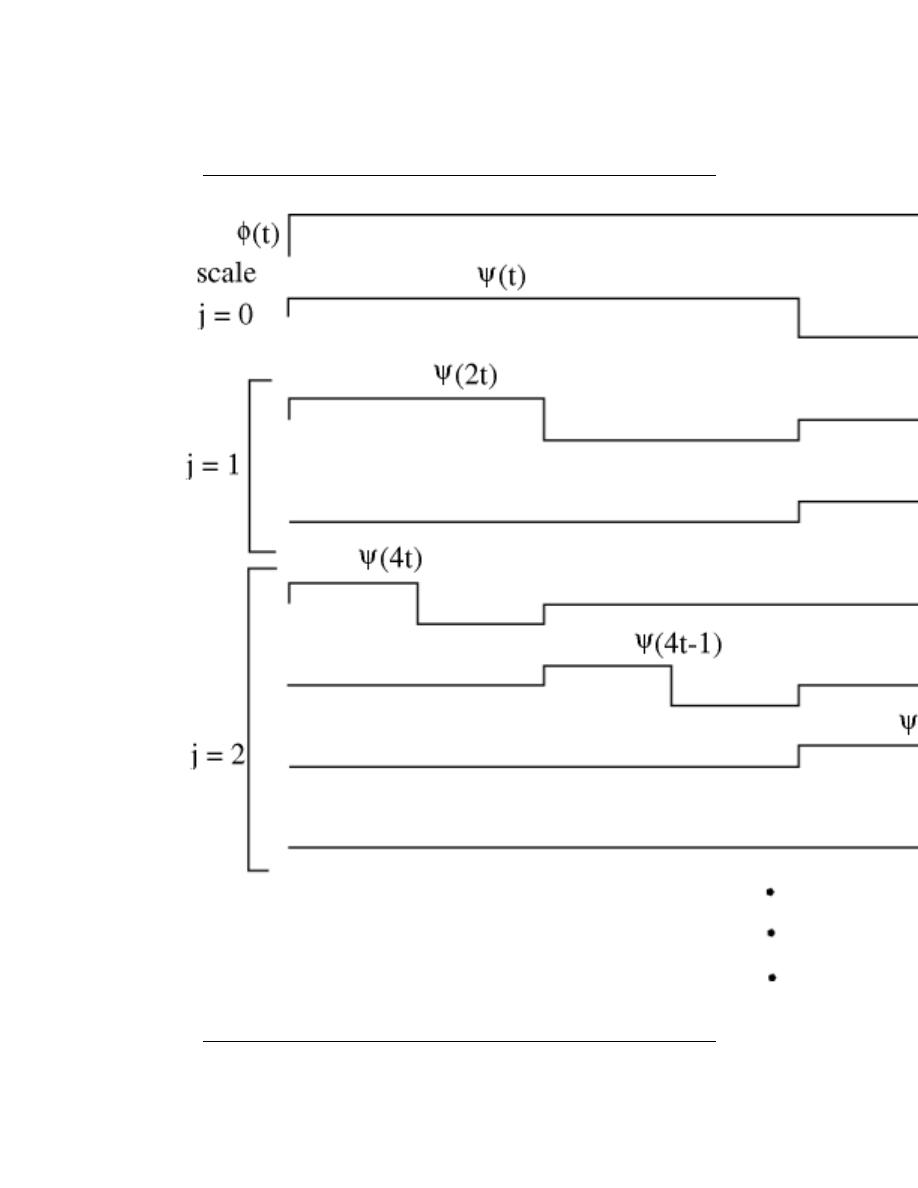

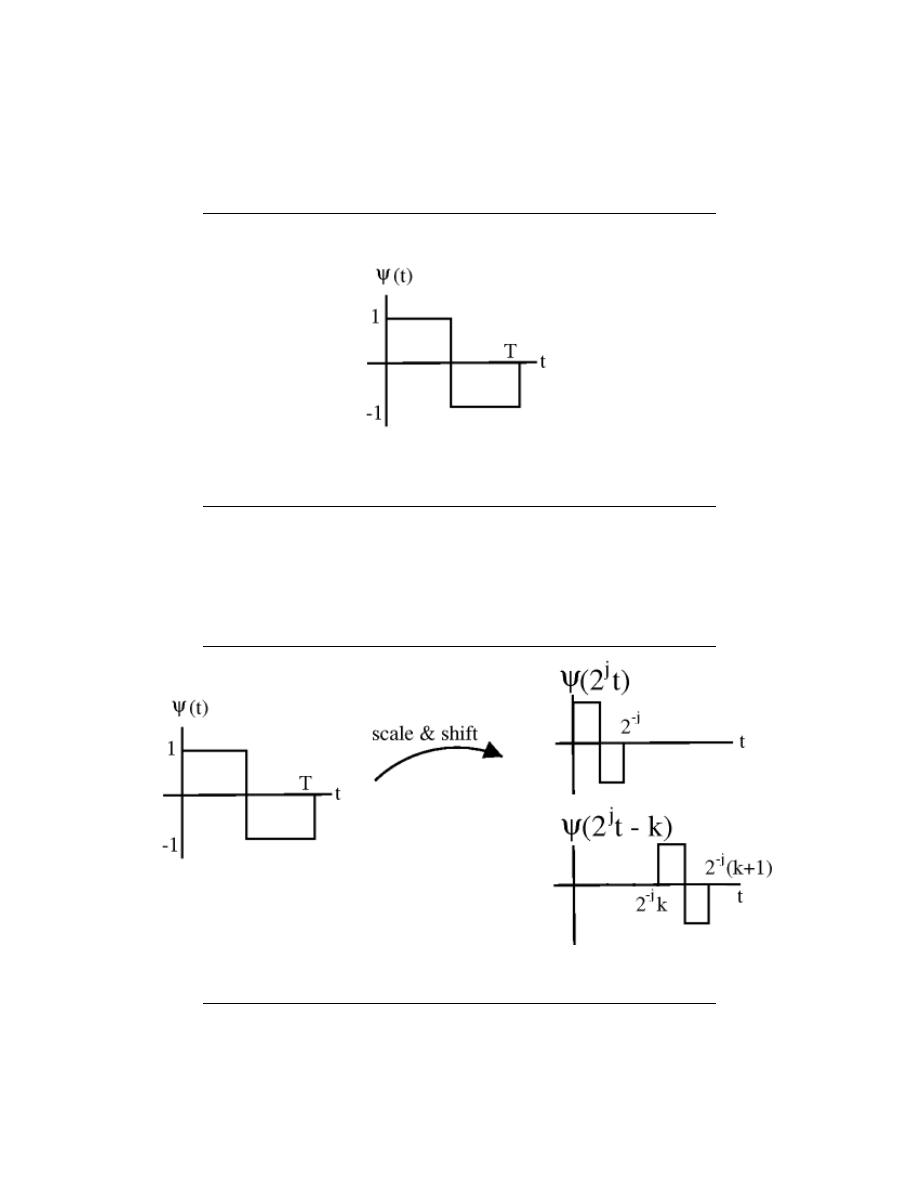

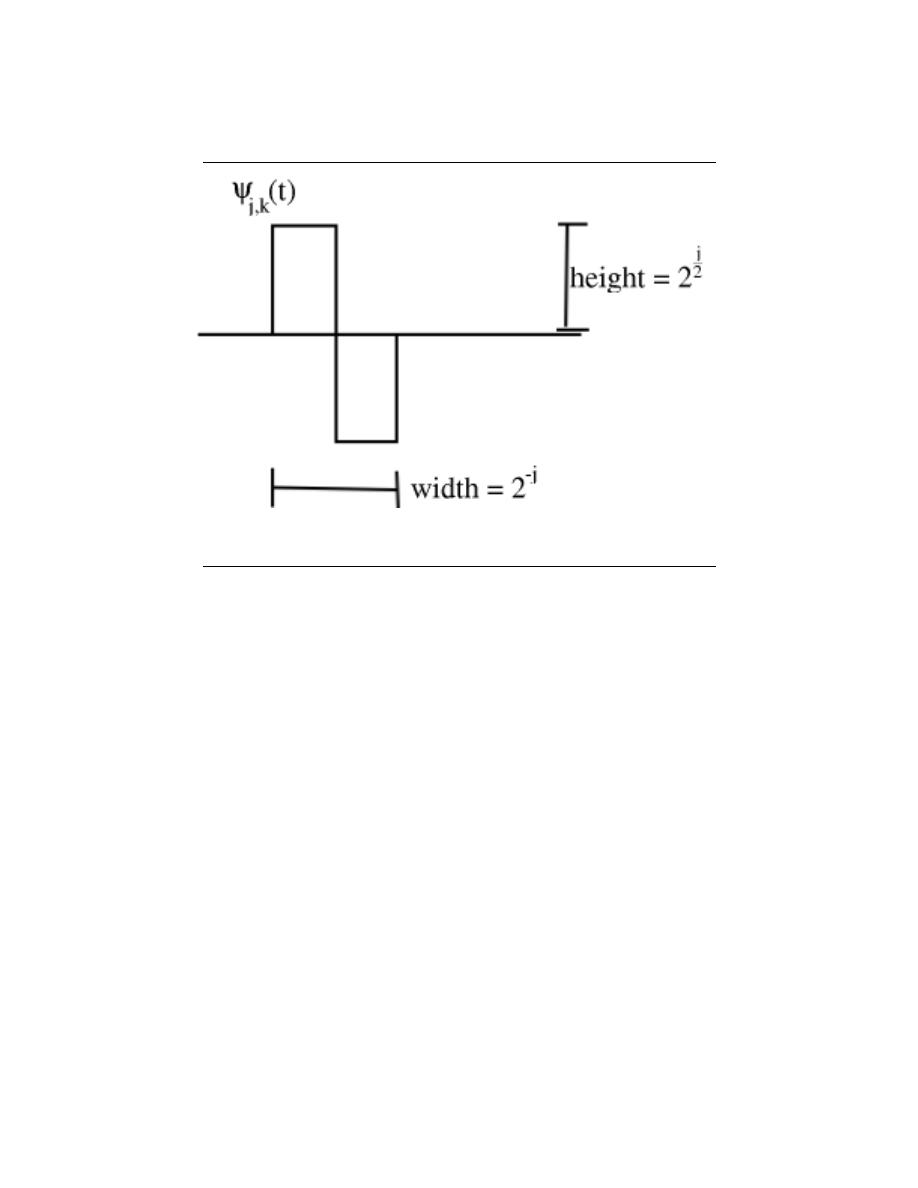

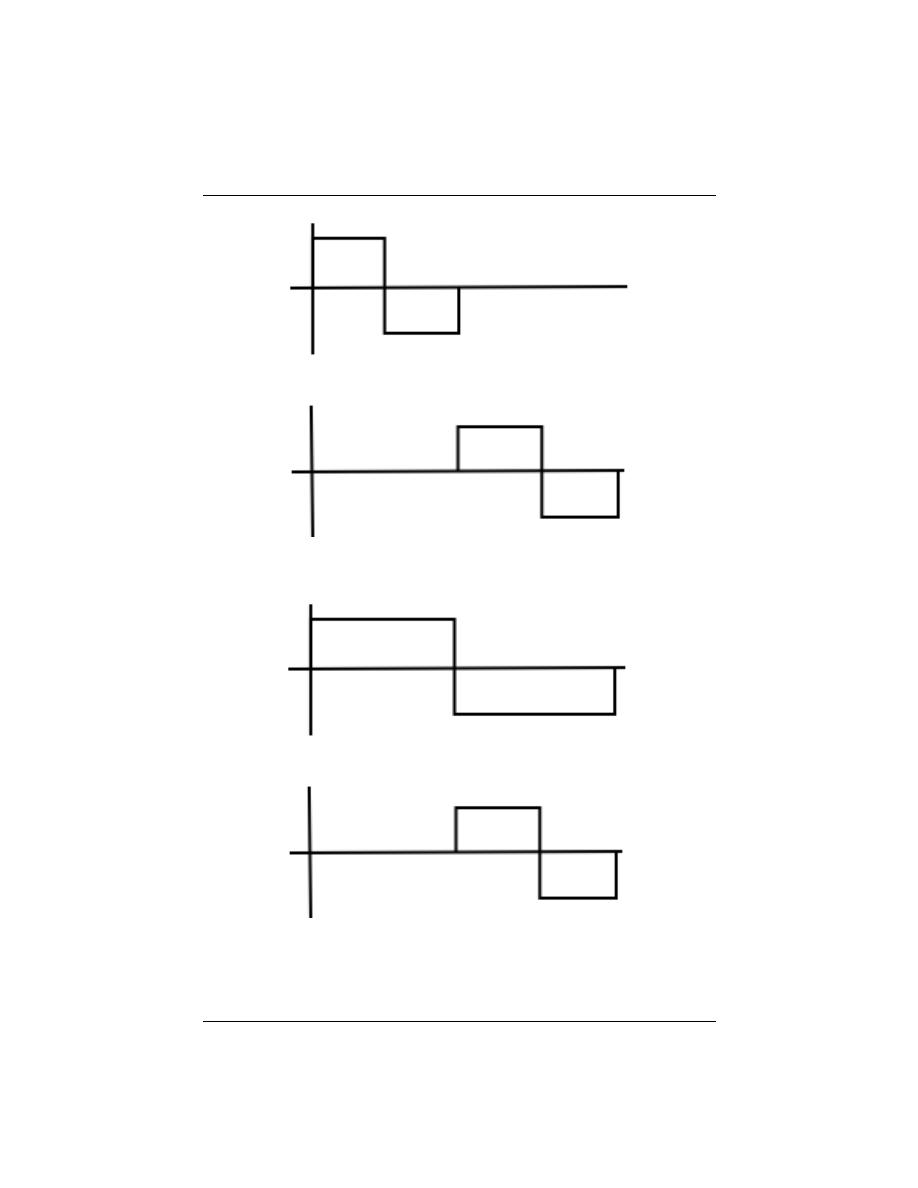

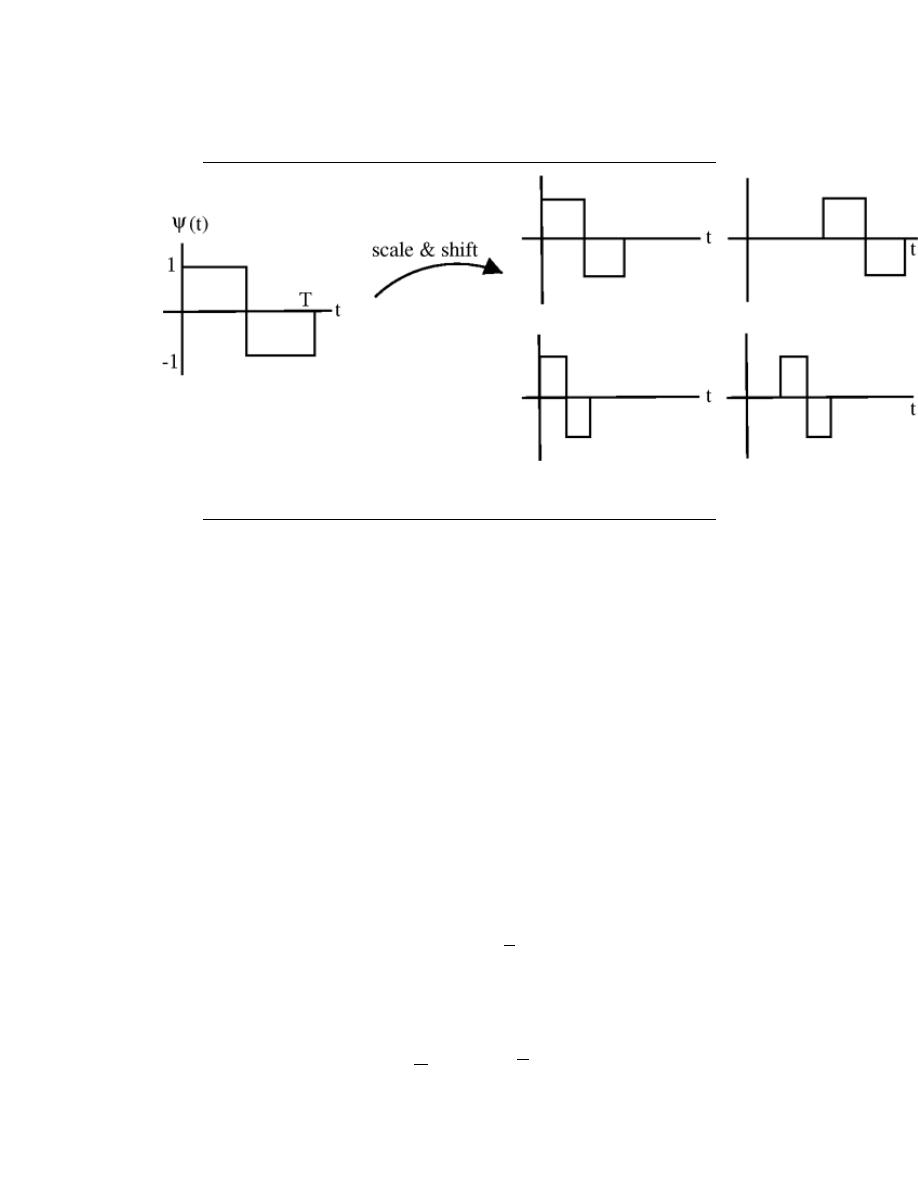

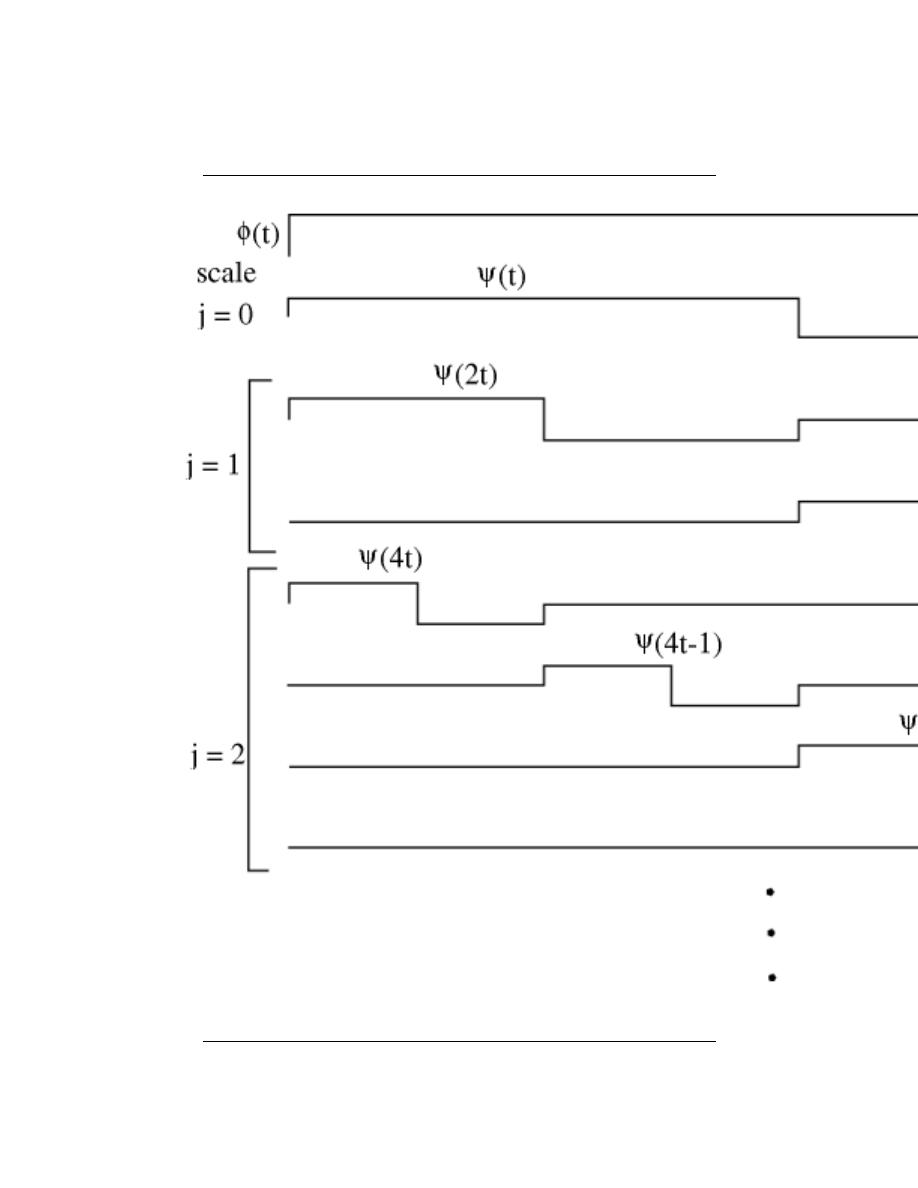

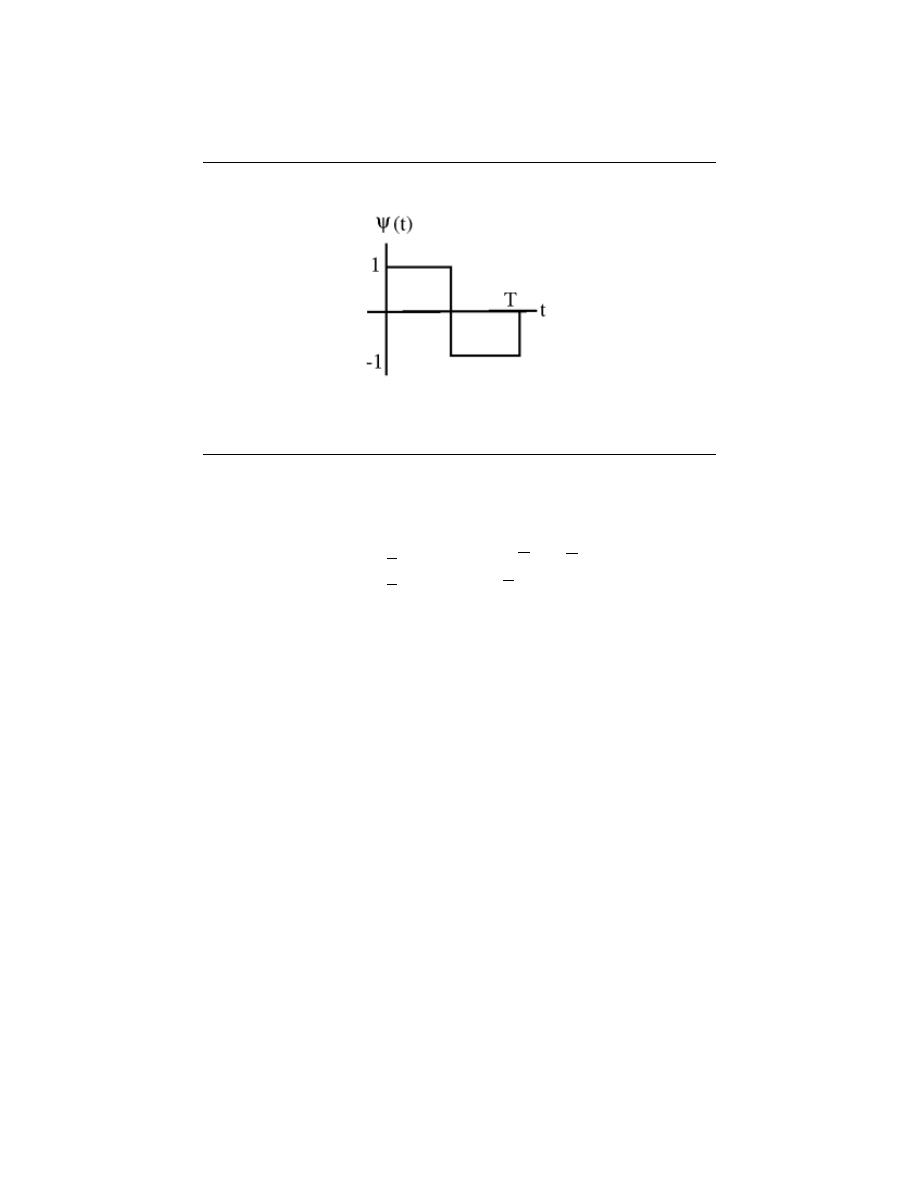

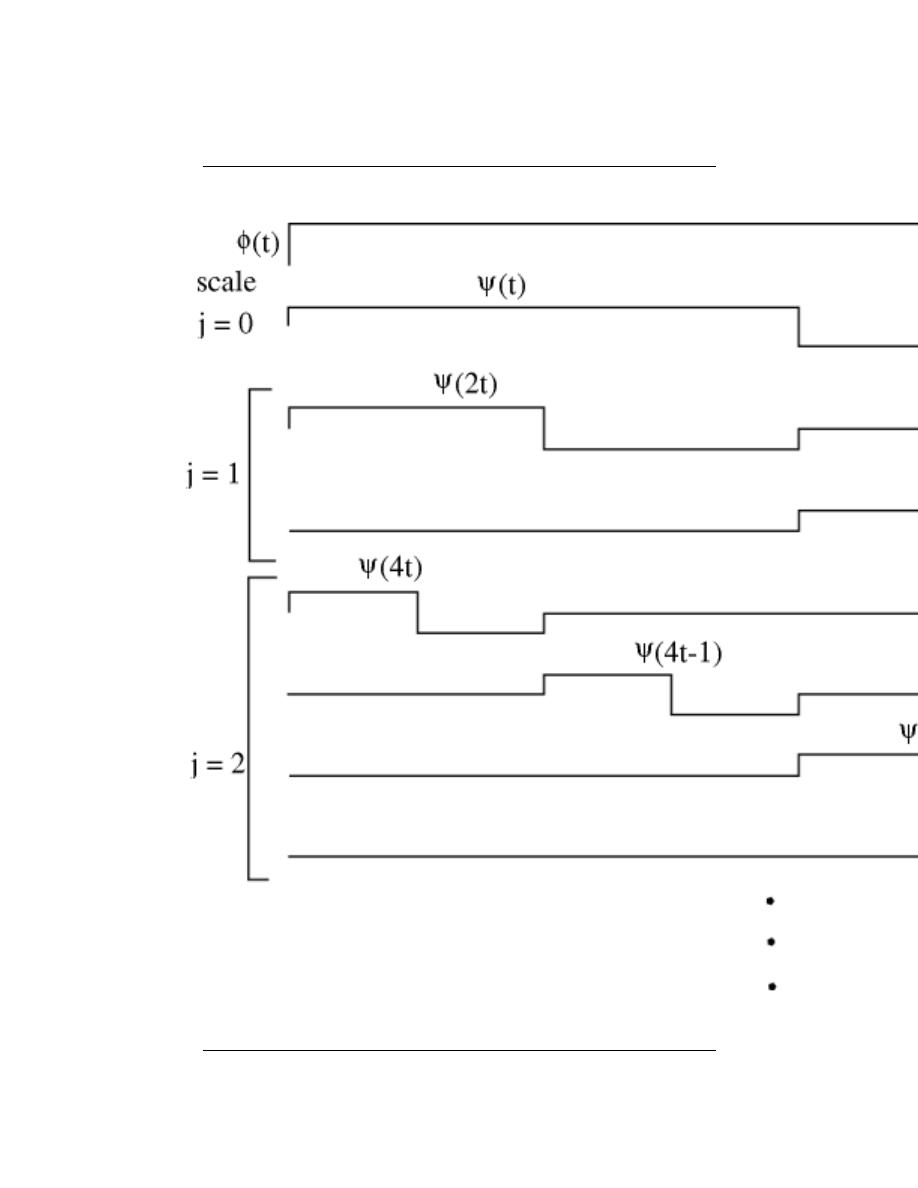

7.10 Haar Wavelet Basis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 140

7.11 Orthonormal Bases in Real and Complex Spaces . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143

7.12 Plancharel and Parseval’s Theorems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 148

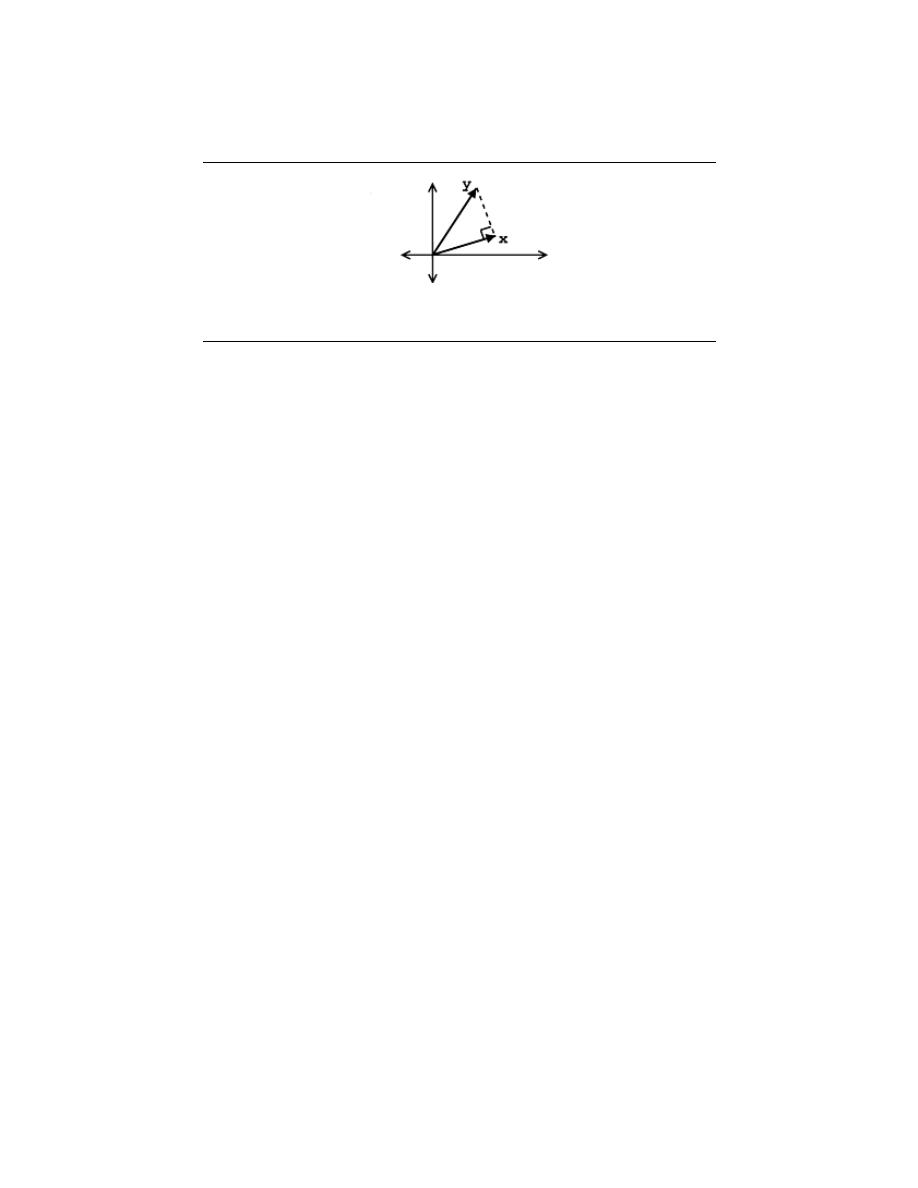

7.13 Approximation and Projections in Hilbert Space . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151

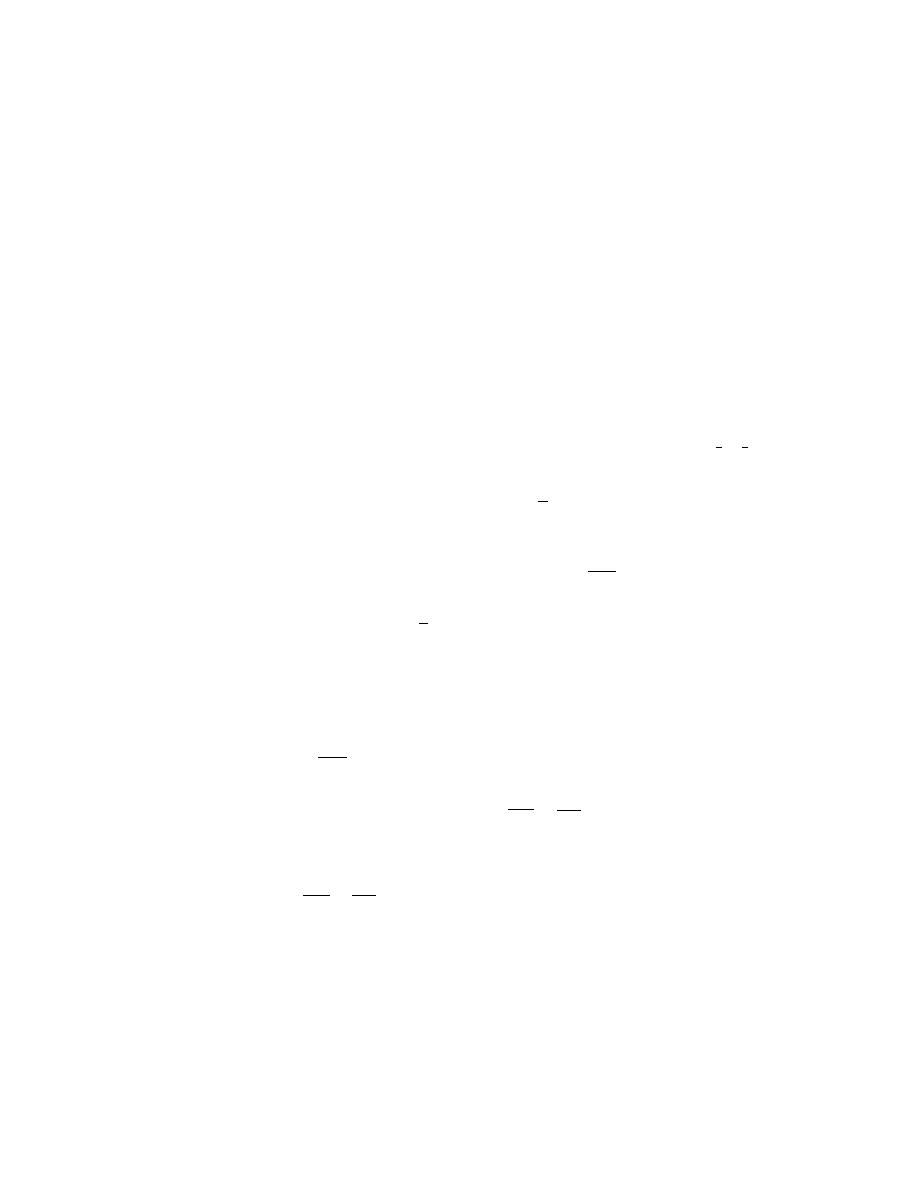

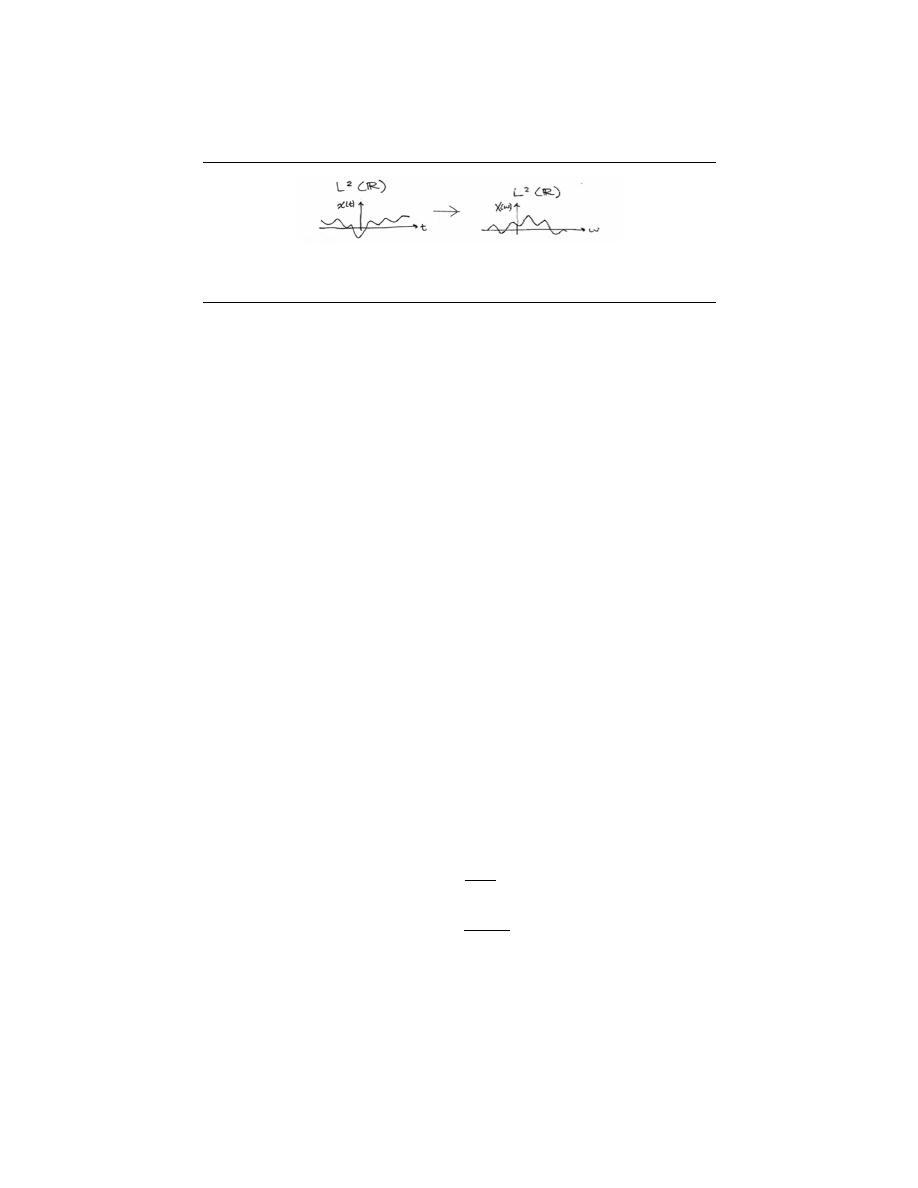

7 Fourier Analysis on Complex Spaces

8.1 Fourier Analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153

8.2 Fourier Analysis in Complex Spaces . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 154

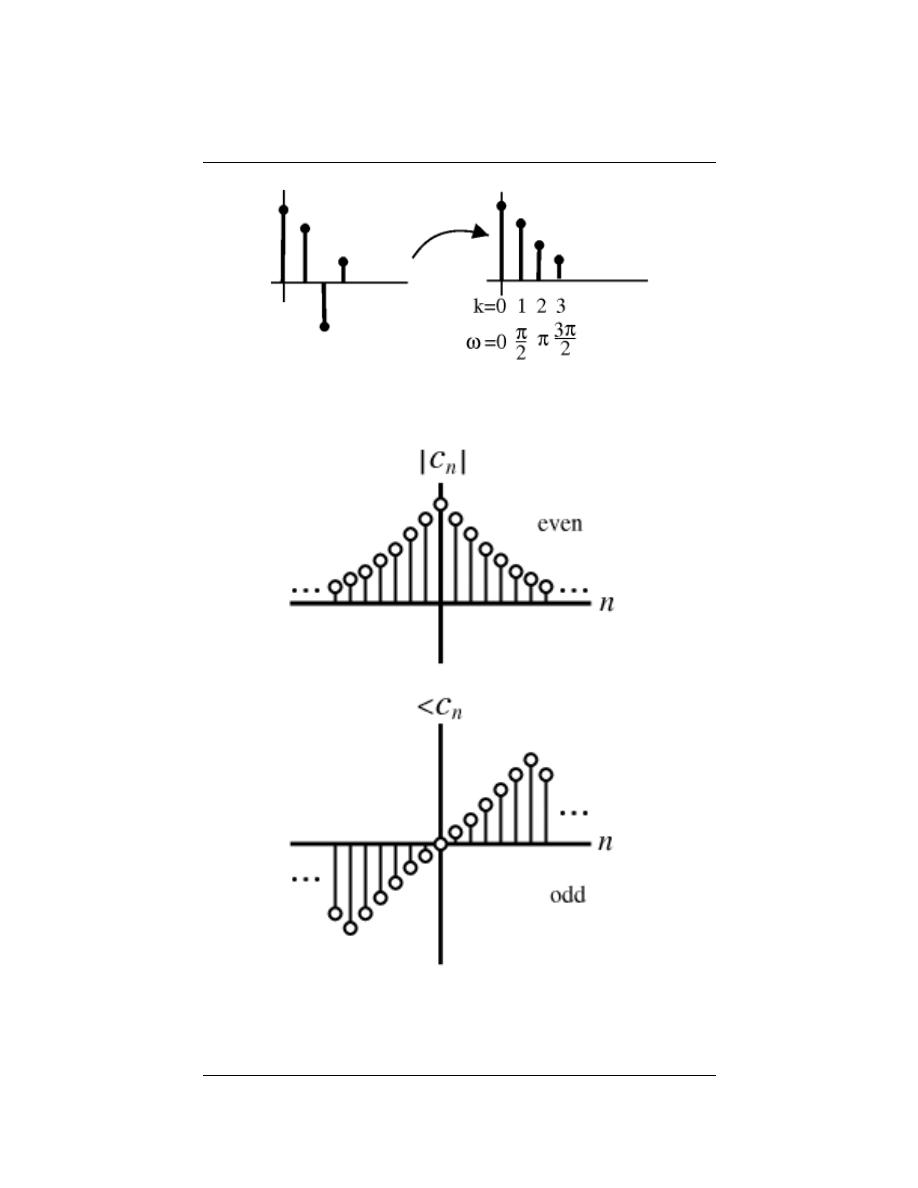

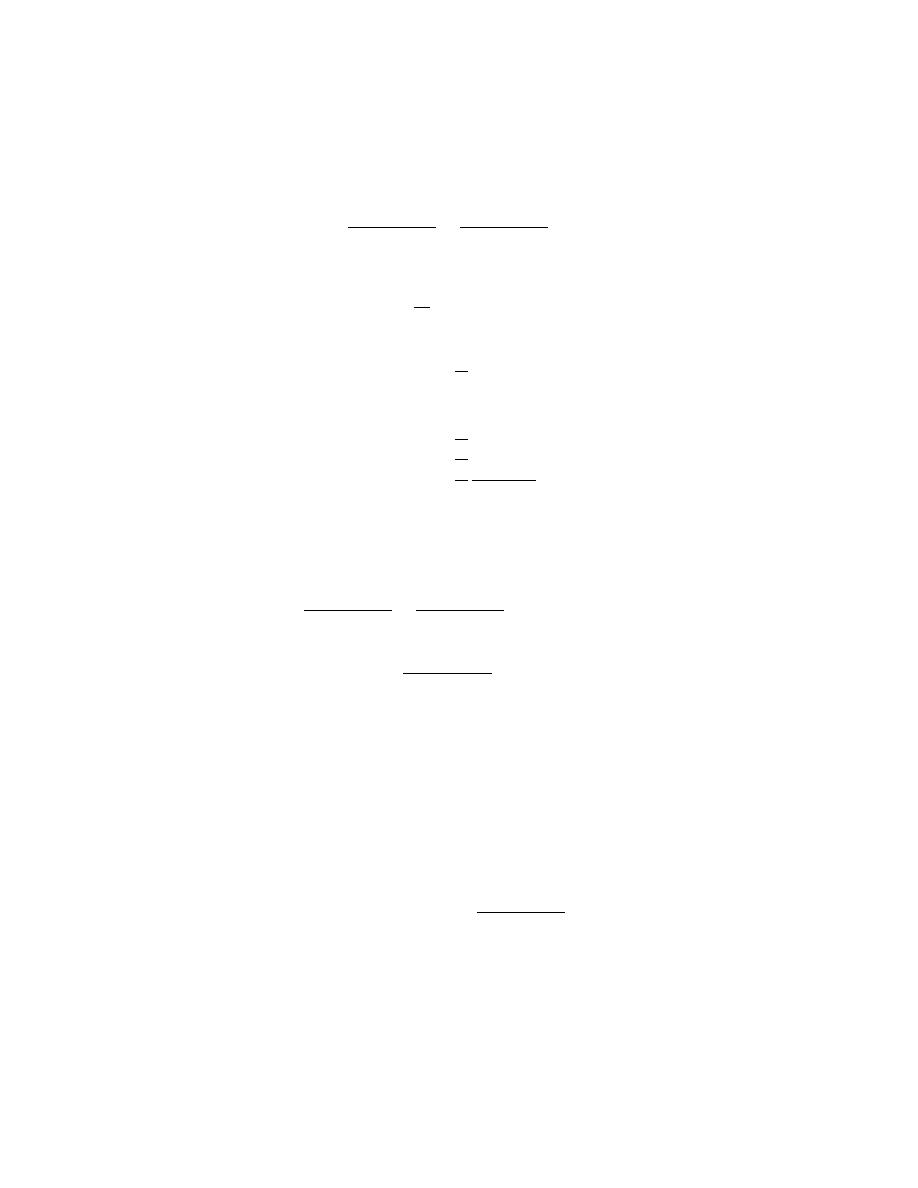

8.3 Matrix Equation for the DTFS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 163

8.4 Periodic Extension to DTFS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 164

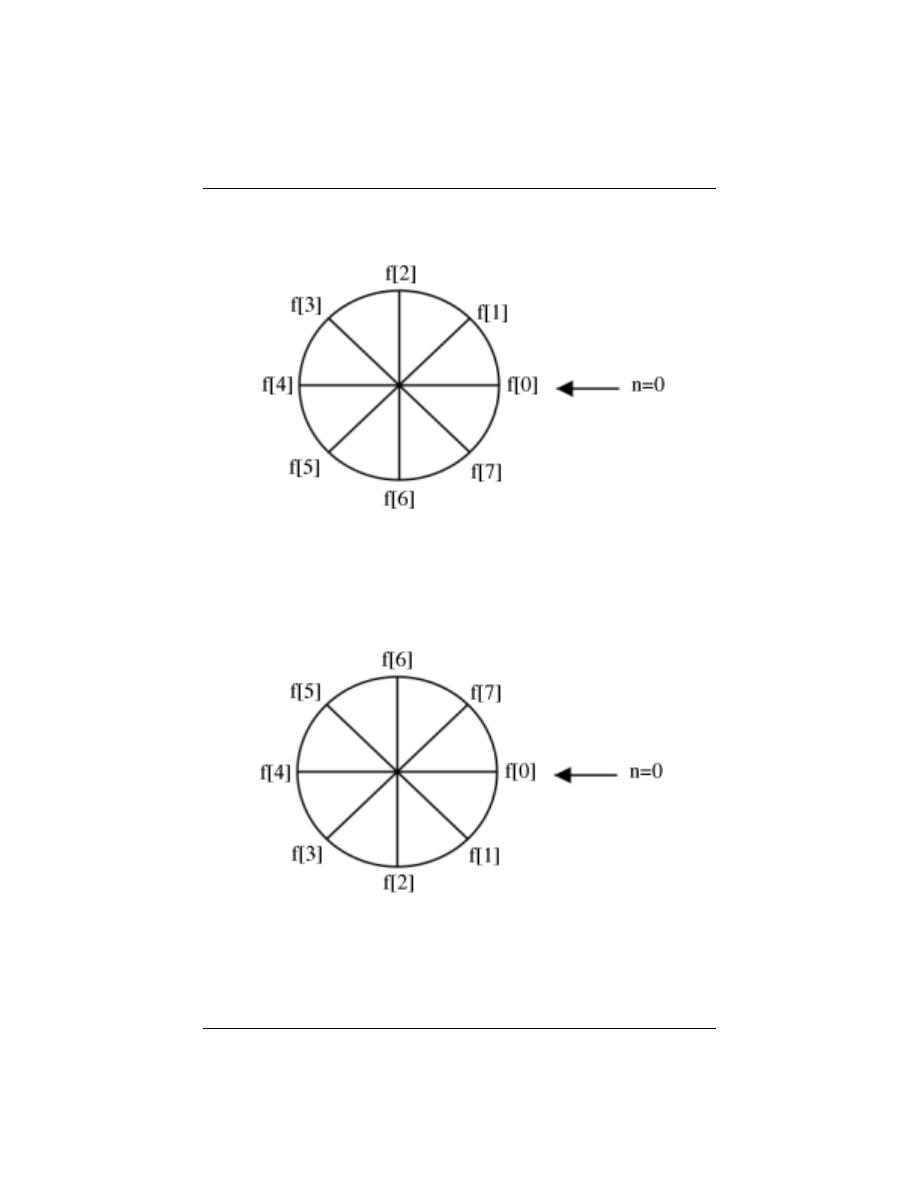

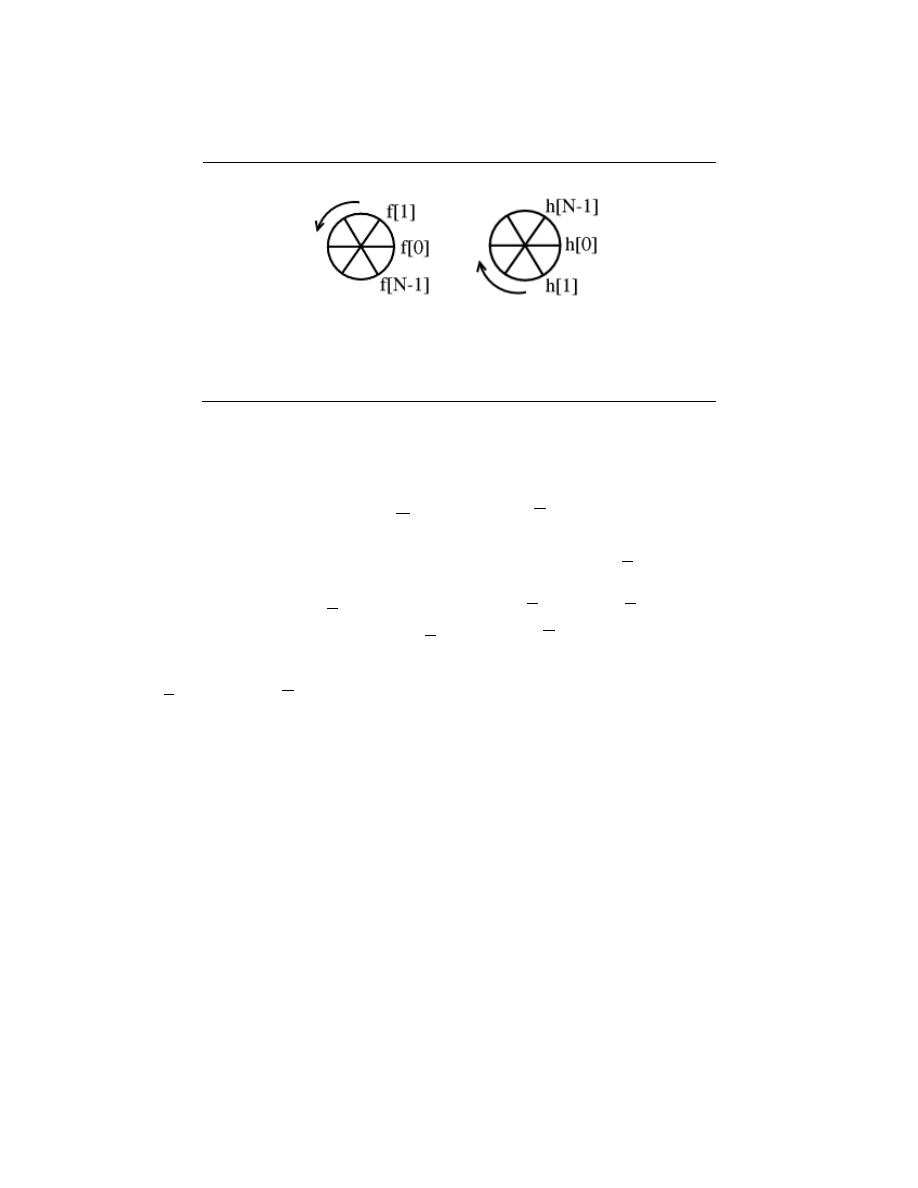

8.5 Circular Shifts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 168

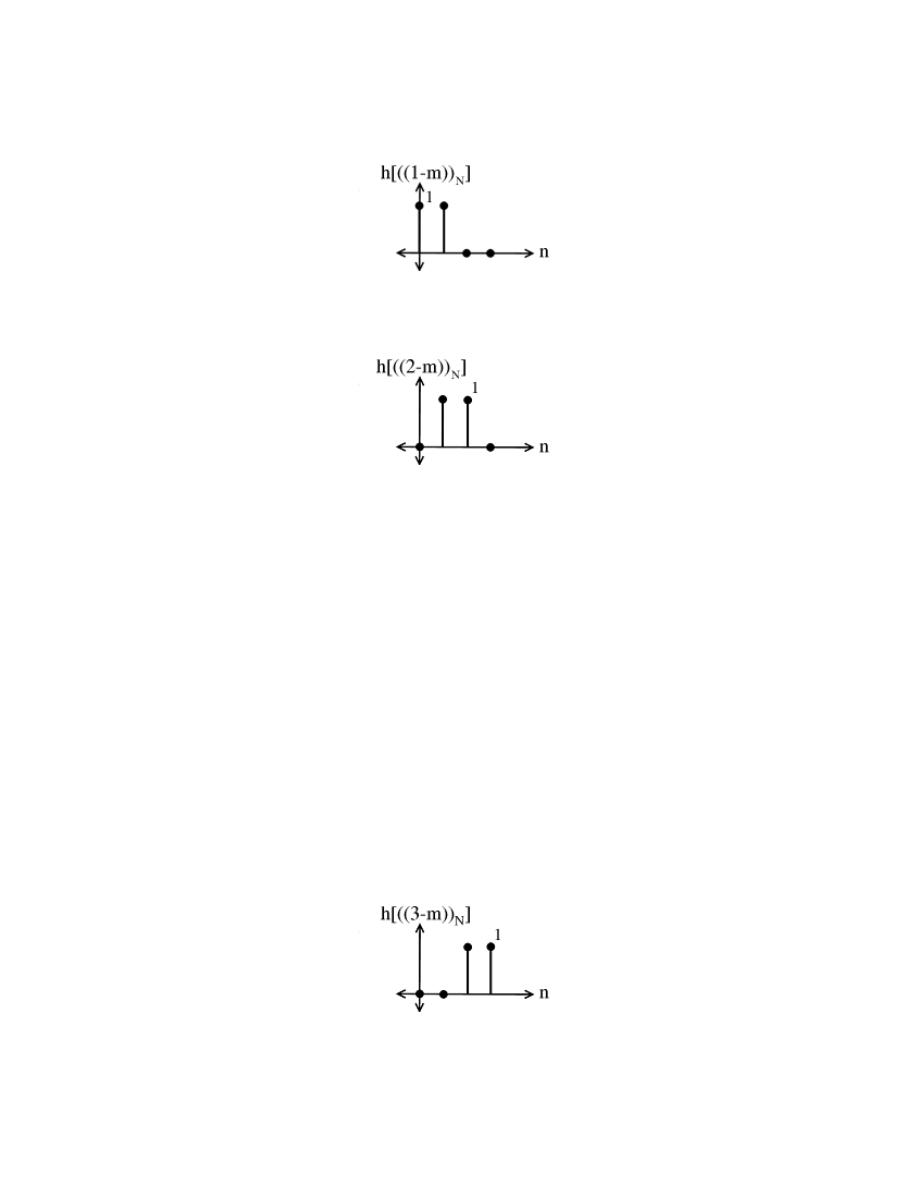

8.6 Circular Convolution and the DFT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 178

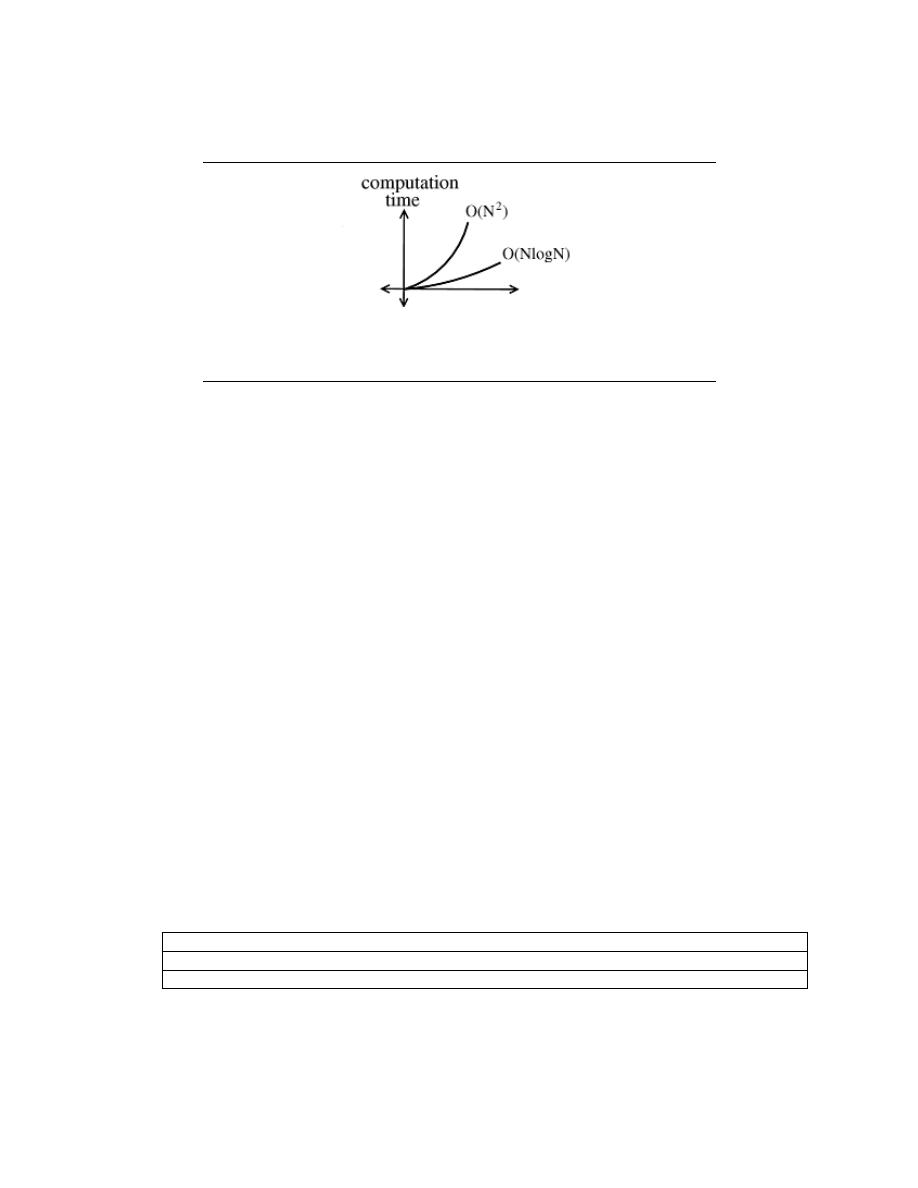

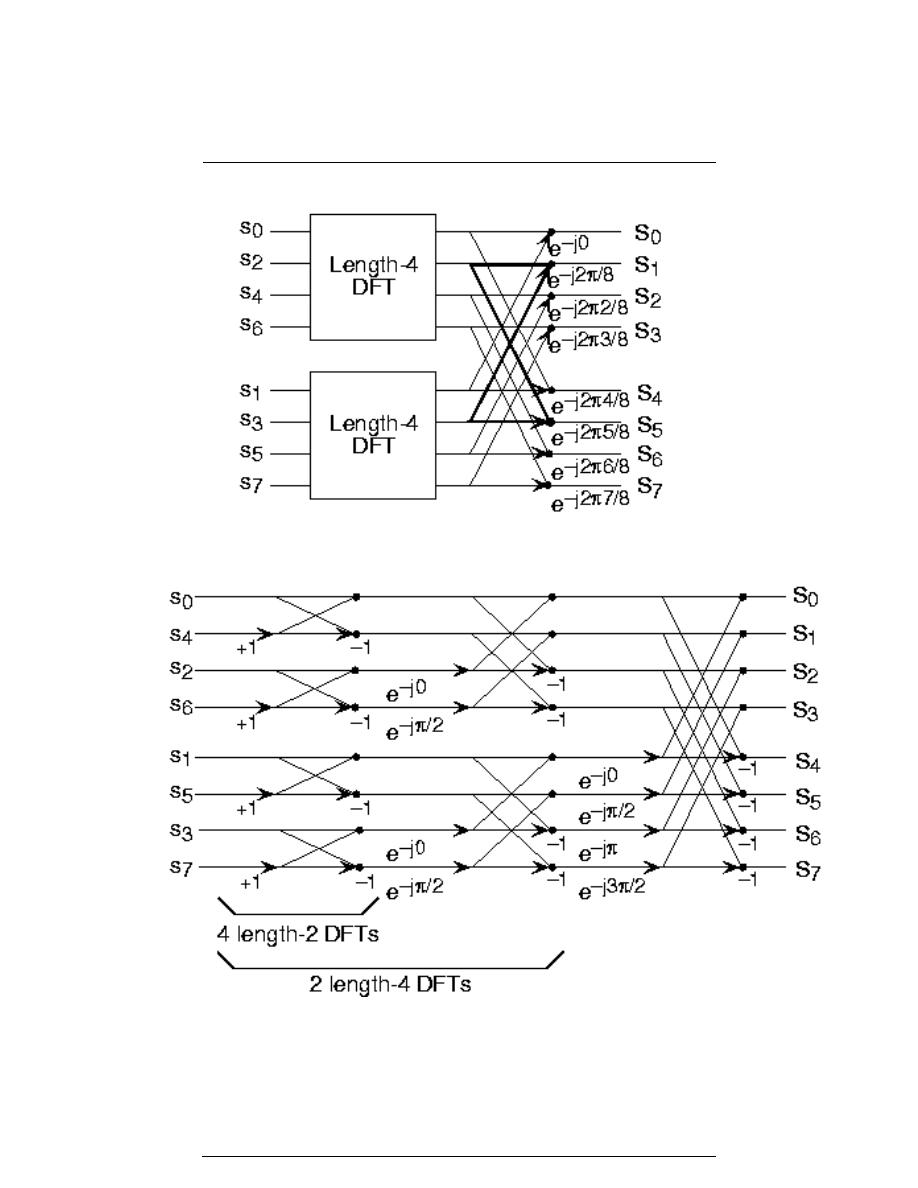

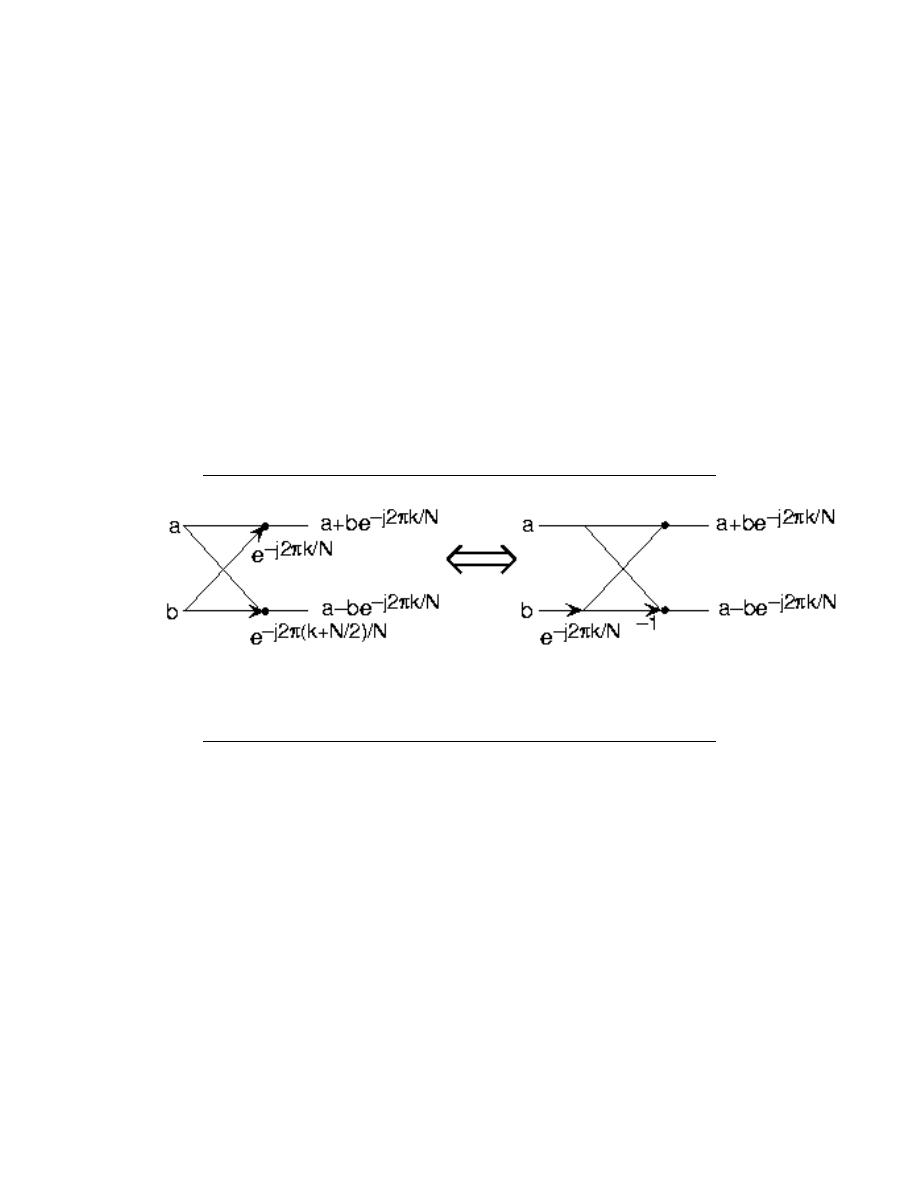

8.7 DFT: Fast Fourier Transform . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 183

8.8 The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 184

8.9 Deriving the Fast Fourier Transform . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 185

8 Convergence

9.1 Convergence of Sequences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 189

9.2 Convergence of Vectors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .190

9.3 Uniform Convergence of Function Sequences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 194

9 Fourier Transform

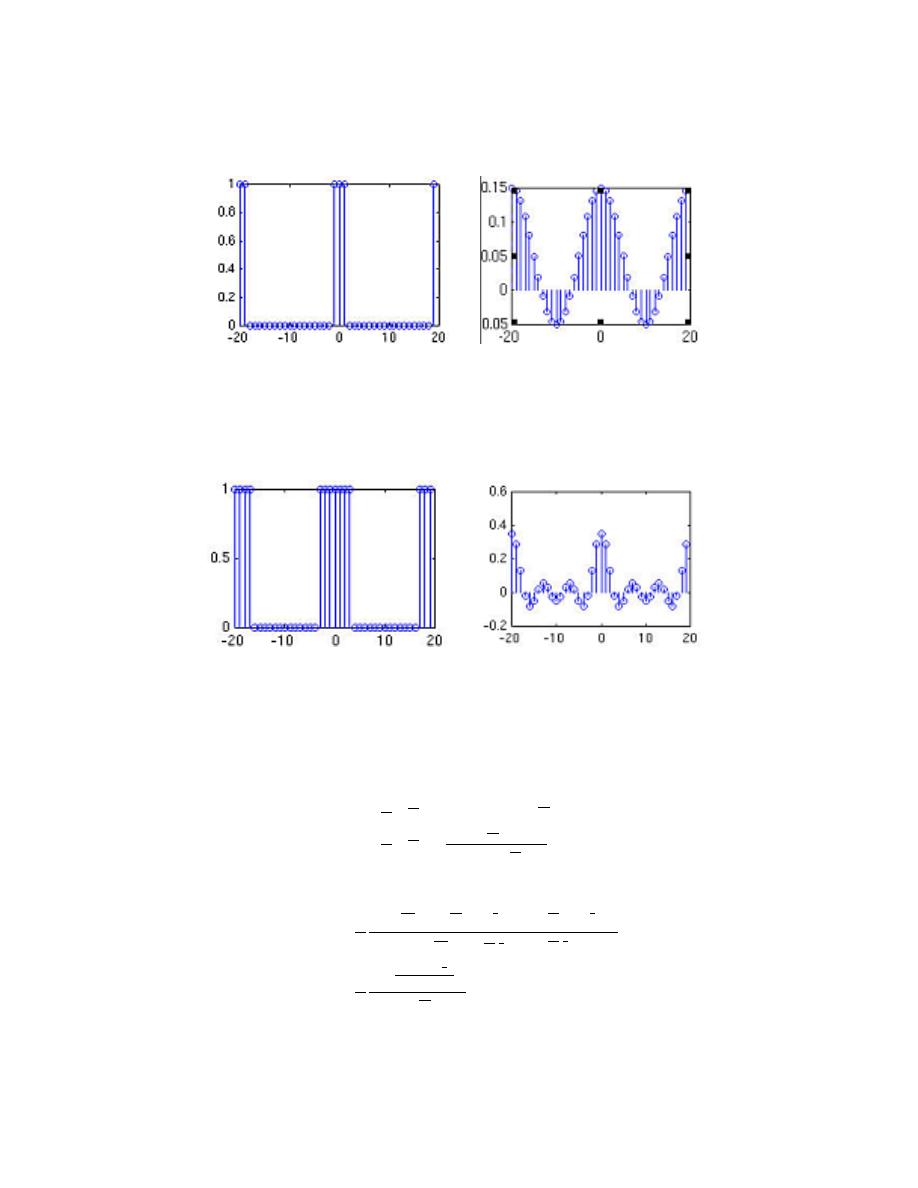

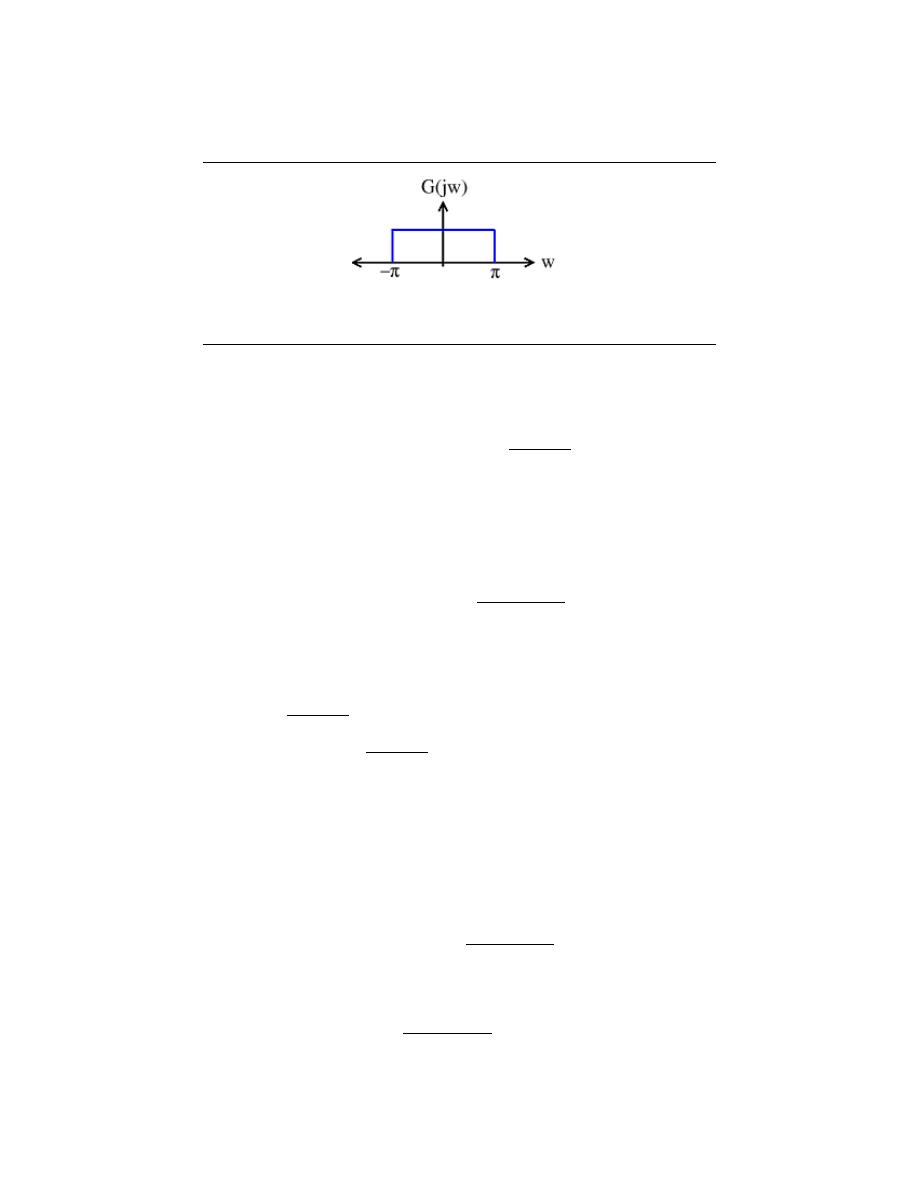

10.1 Discrete Fourier Transformation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 195

10.2 Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 196

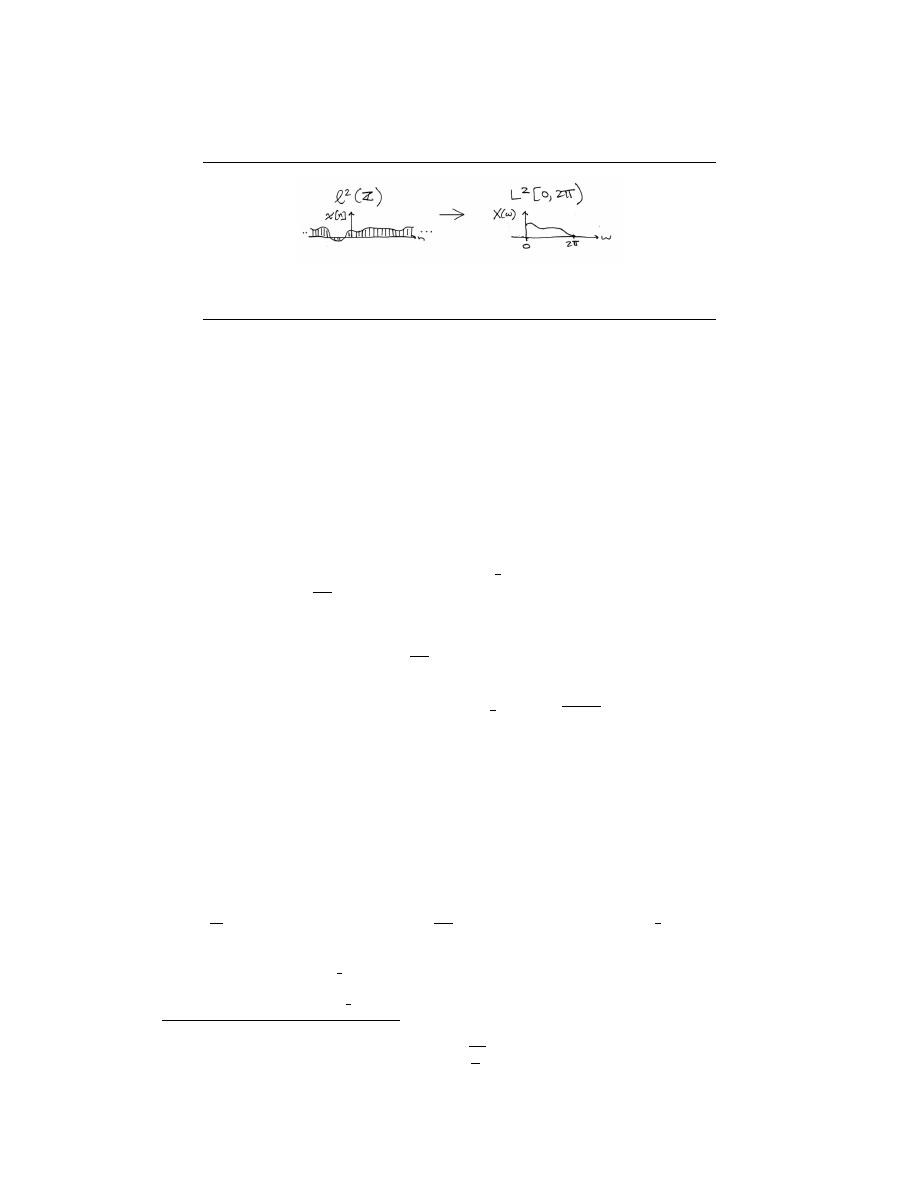

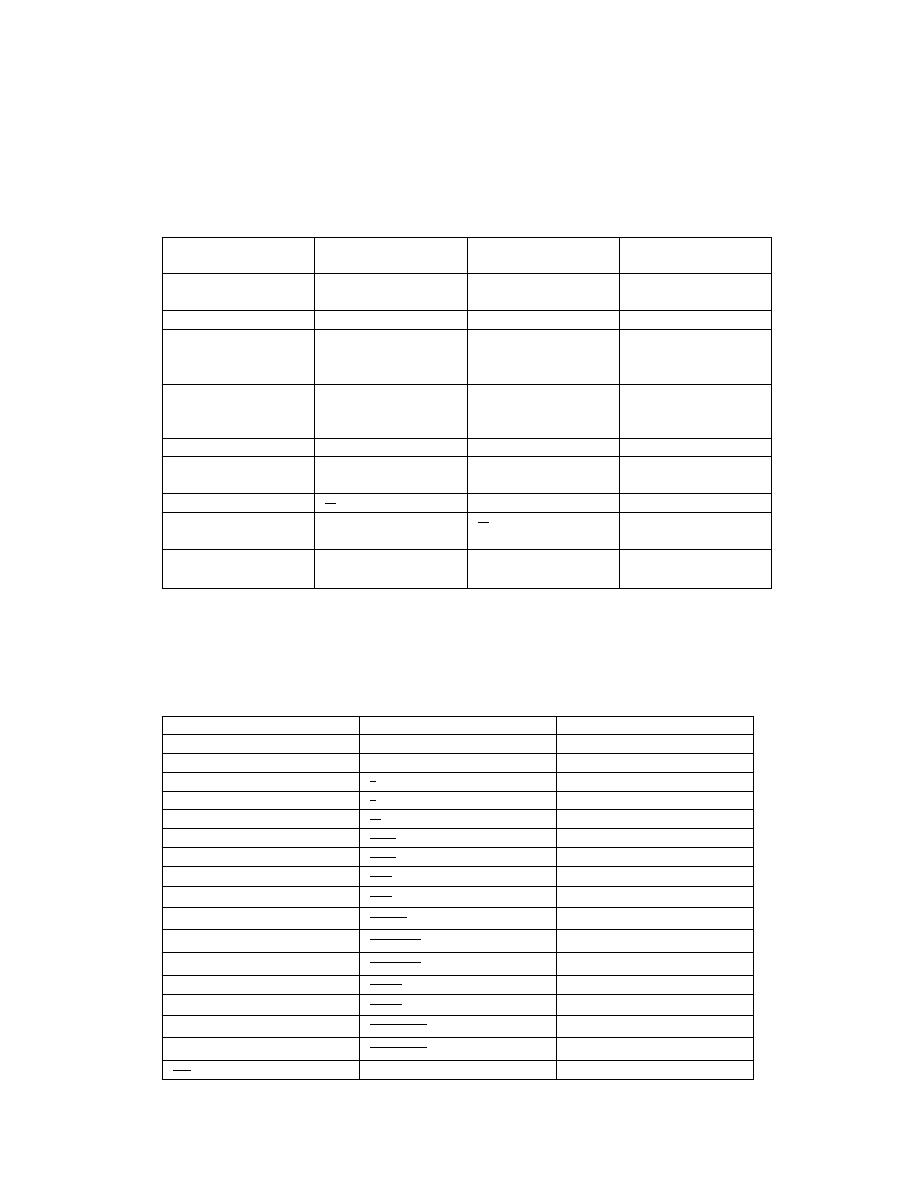

10.3 Table of Common Fourier Transforms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 199

10.4 Discrete-Time Fourier Transform (DTFT) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 199

10.5 Discrete-Time Fourier Transform Properties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 200

10.6 Discrete-Time Fourier Transform Pair . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 200

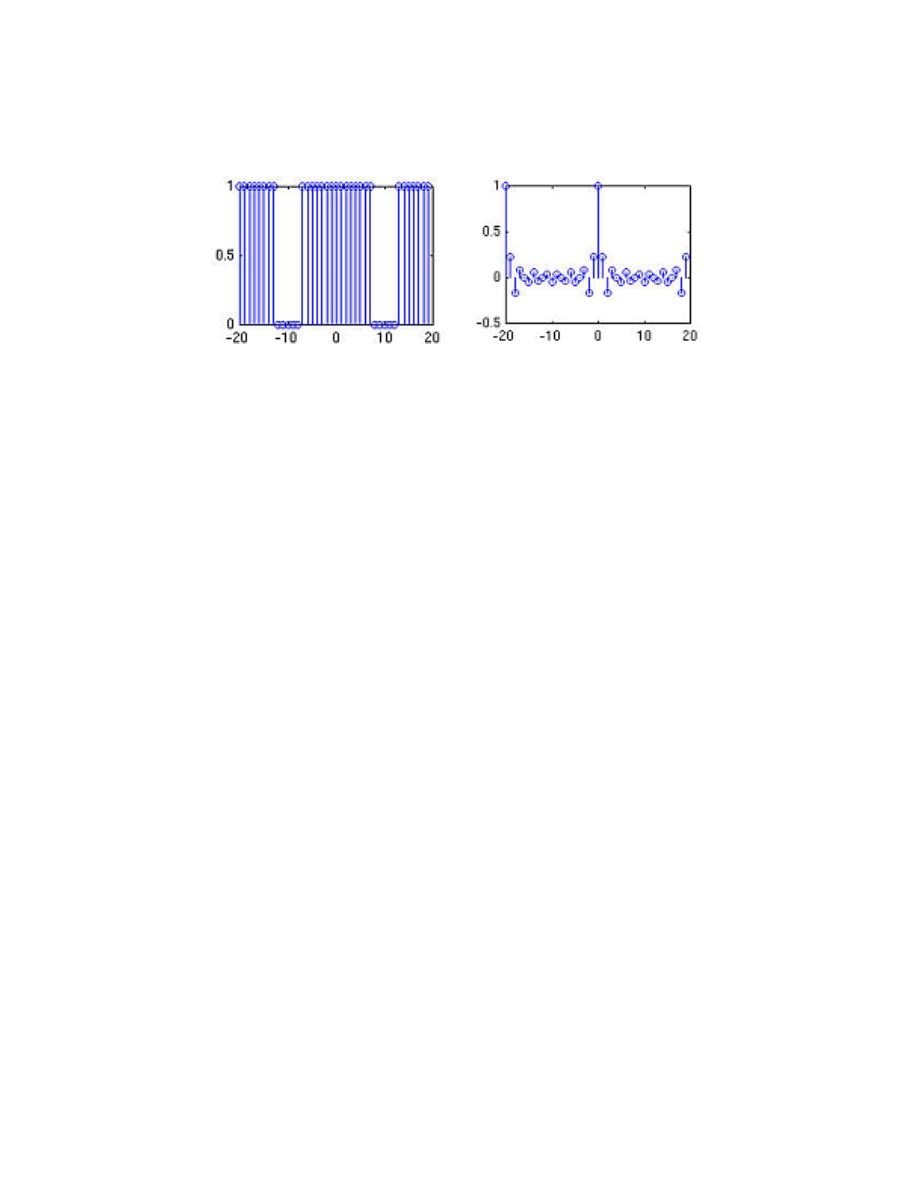

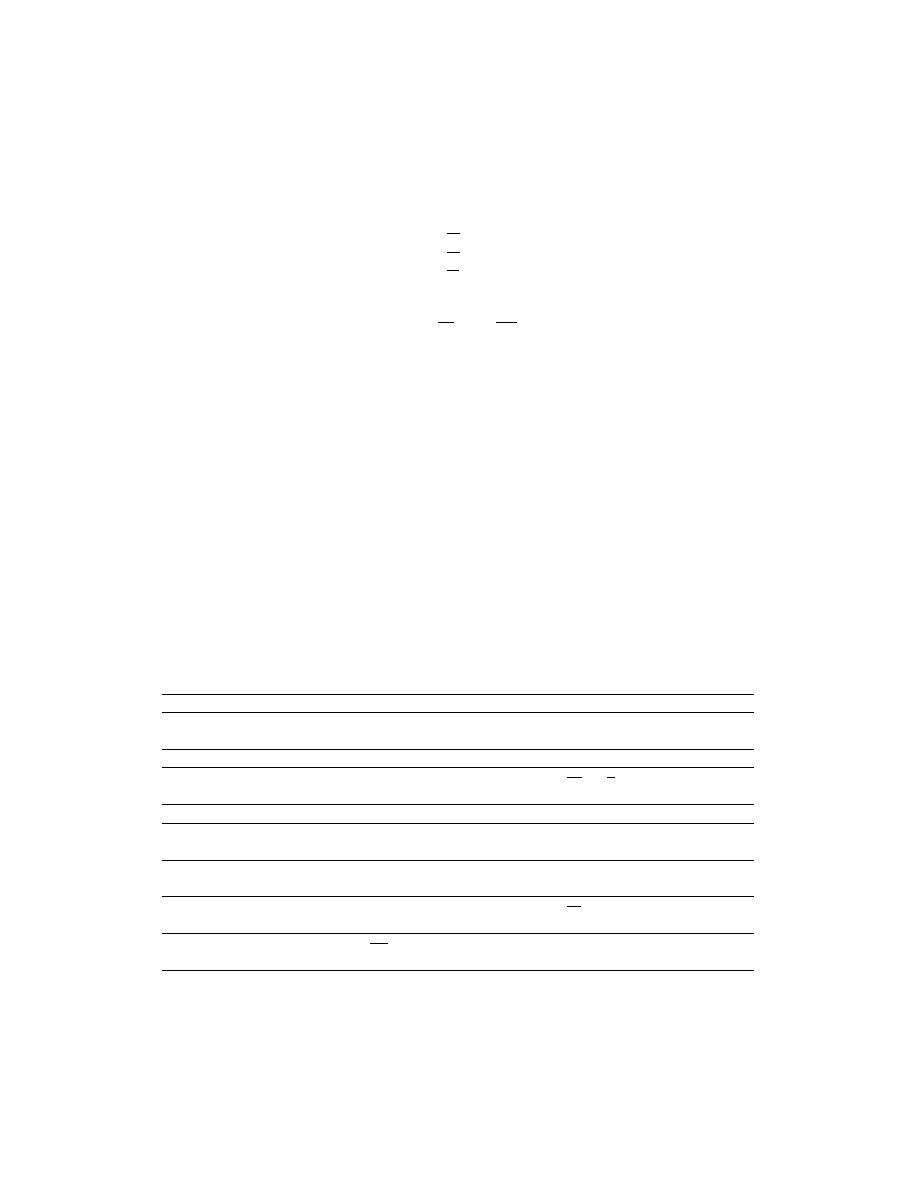

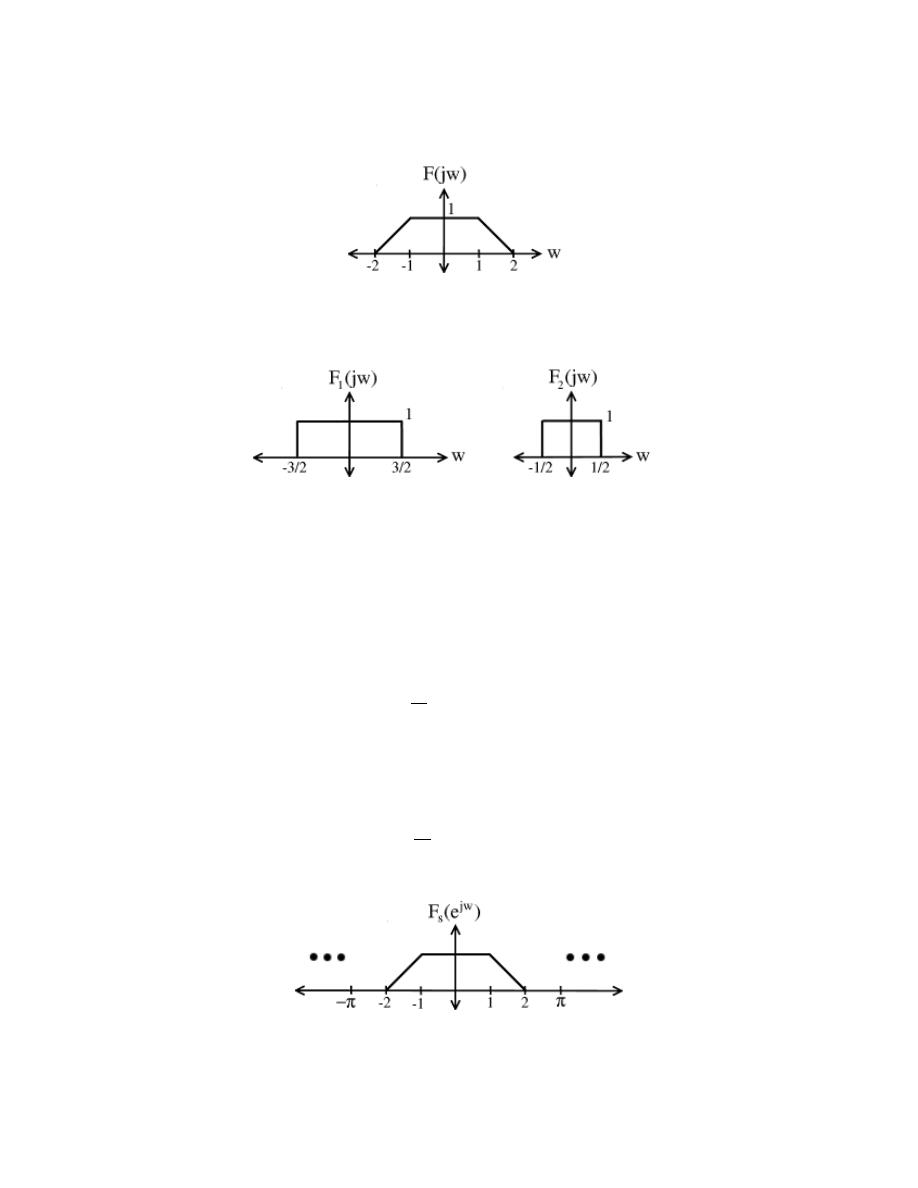

10.7 DTFT Examples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 202

10.8 Continuous-Time Fourier Transform (CTFT) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 204

10.9 Properties of the Continuous-Time Fourier Transform . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 207

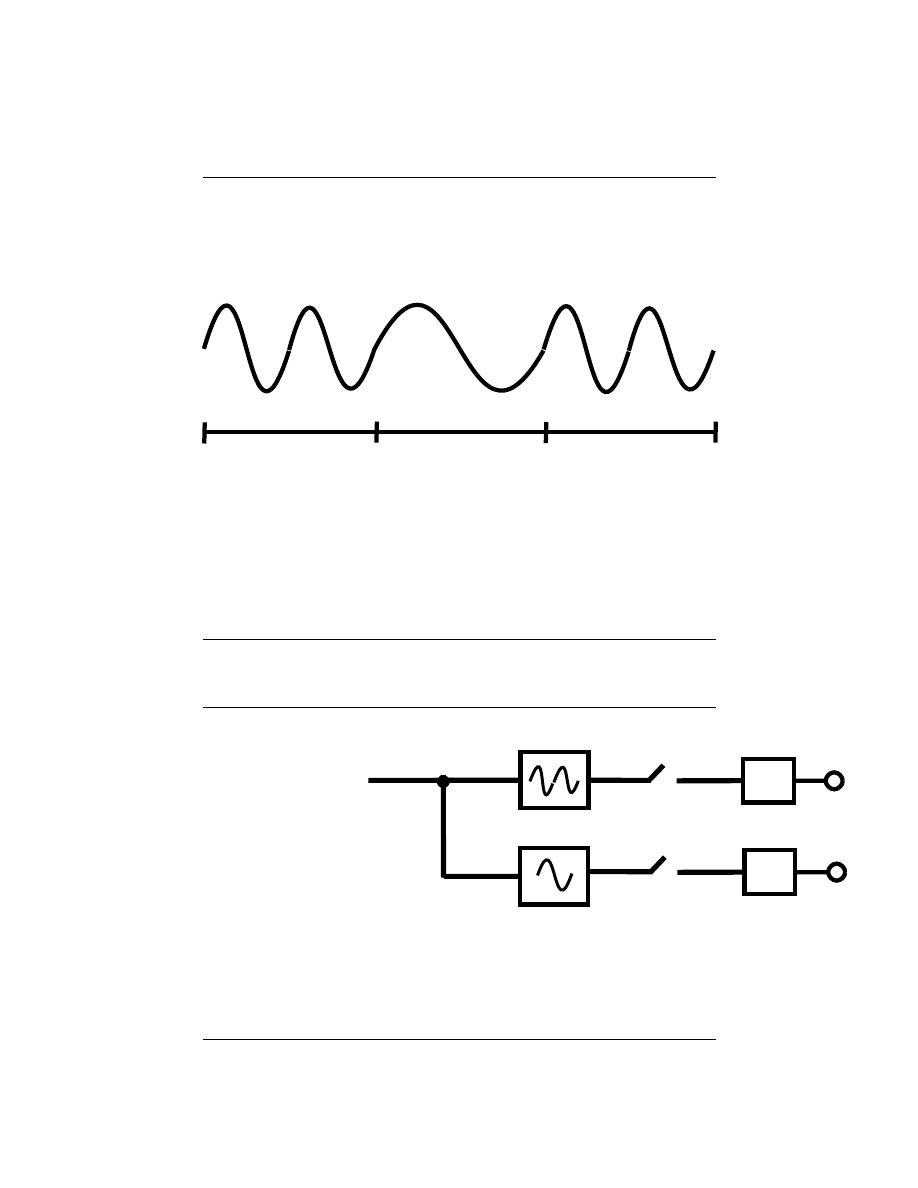

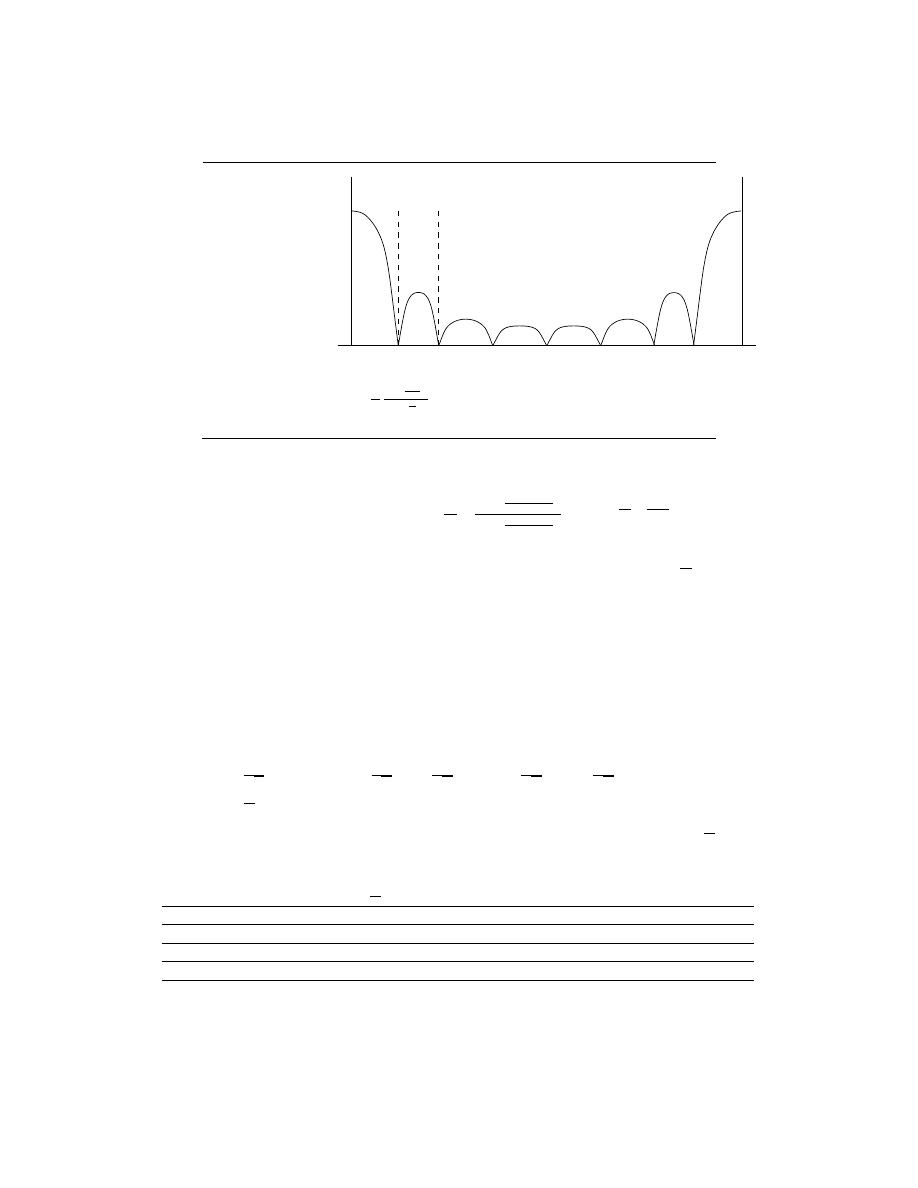

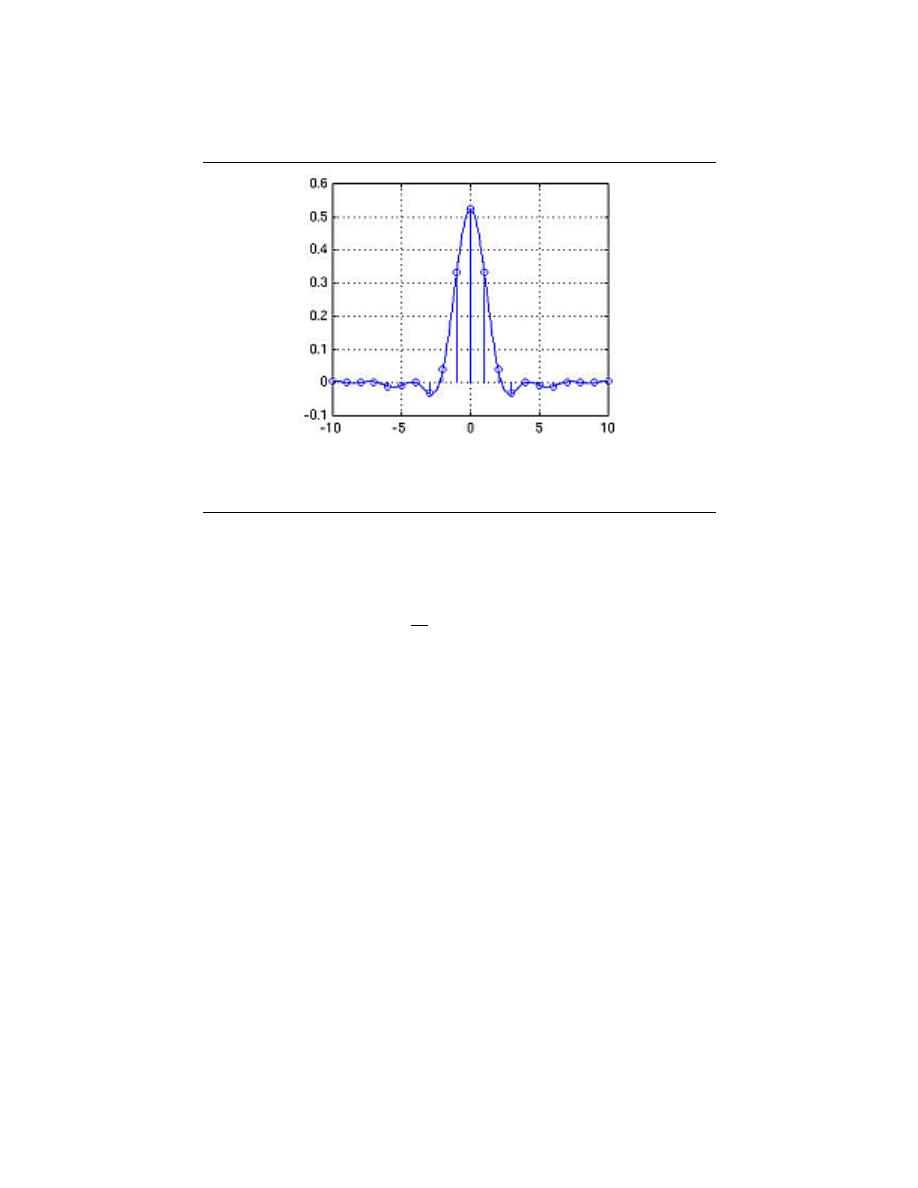

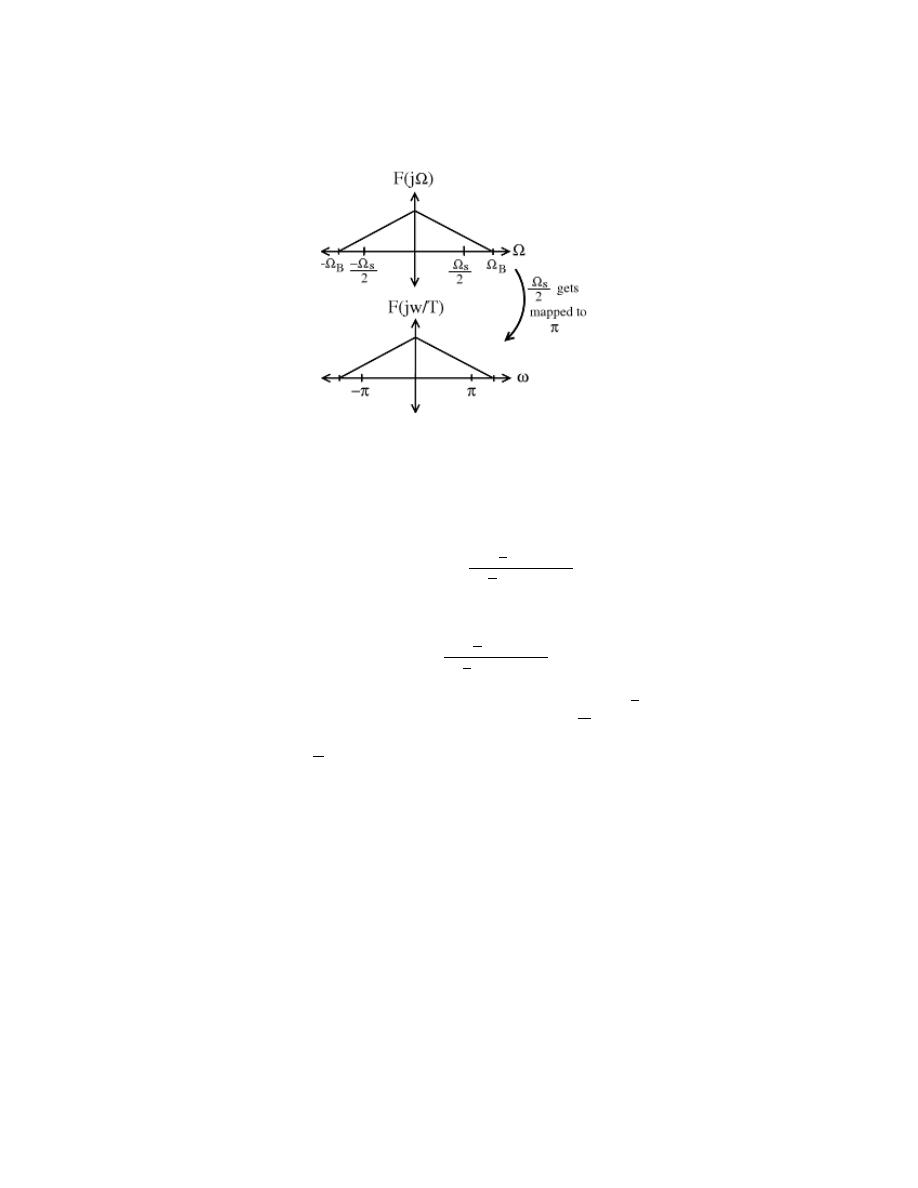

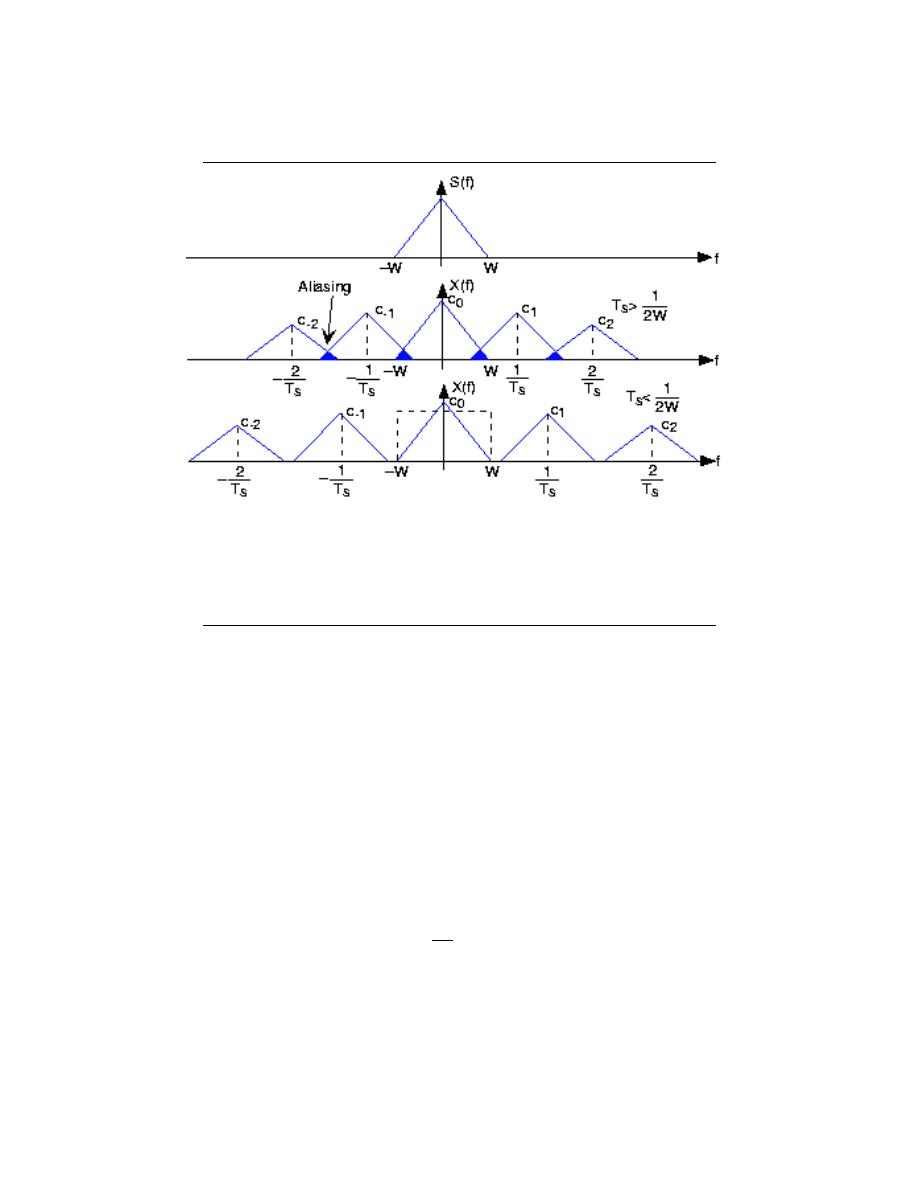

10 Sampling Theorem

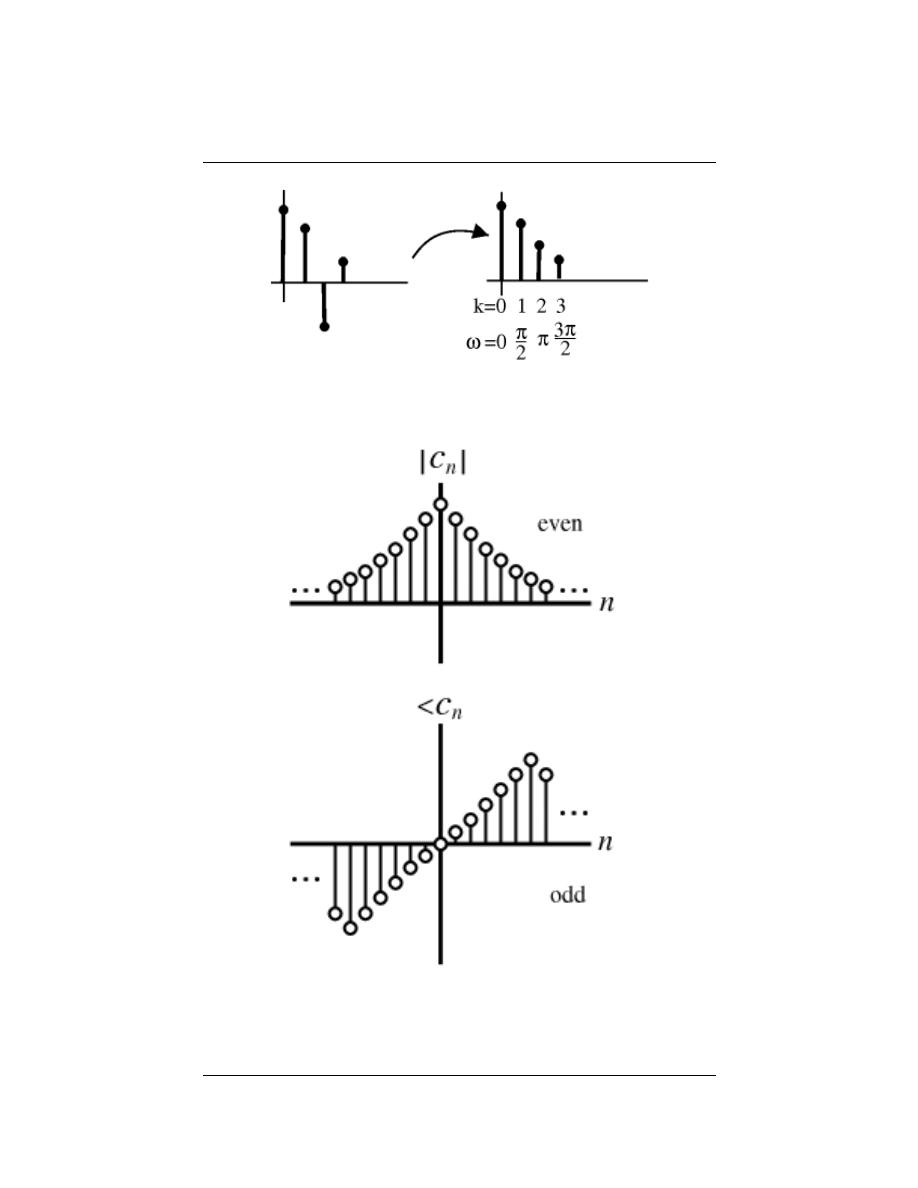

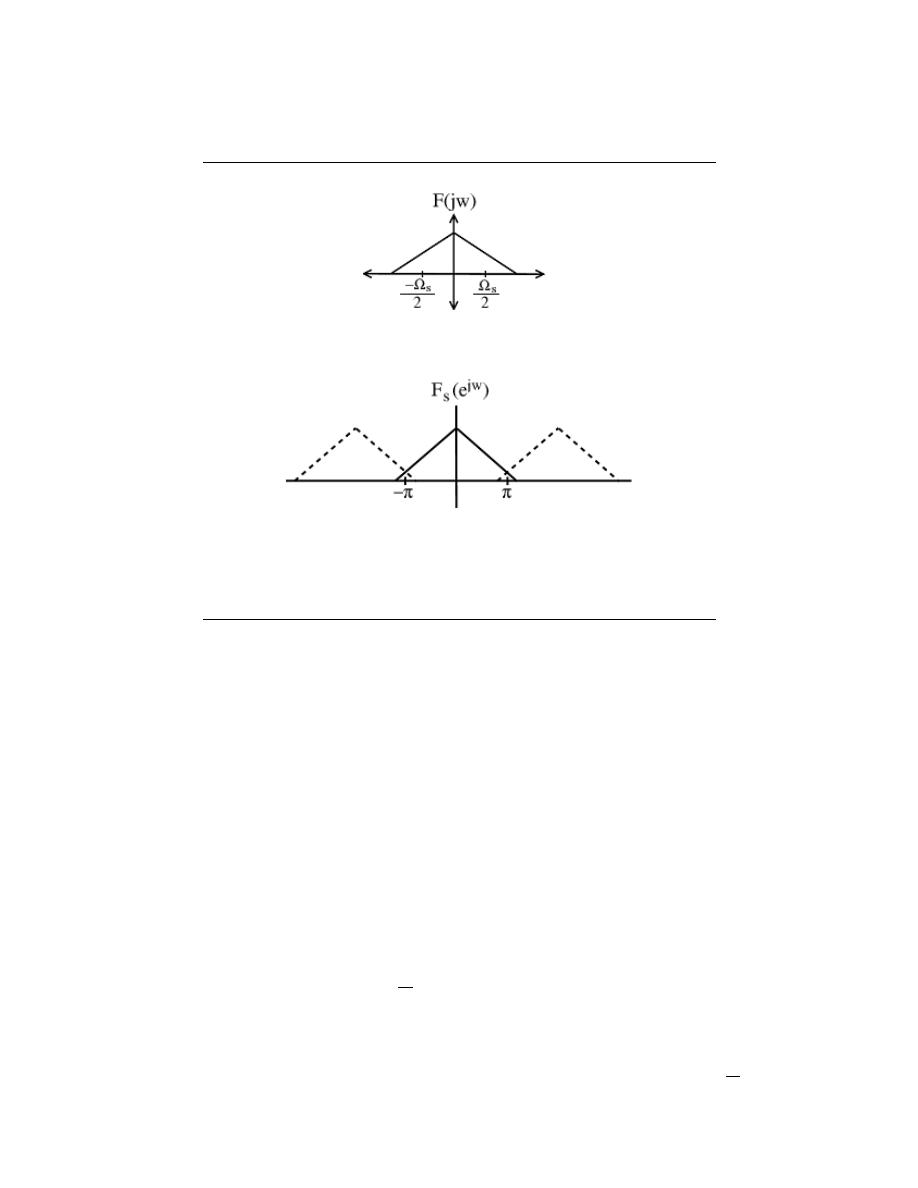

11.1 Sampling . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 211

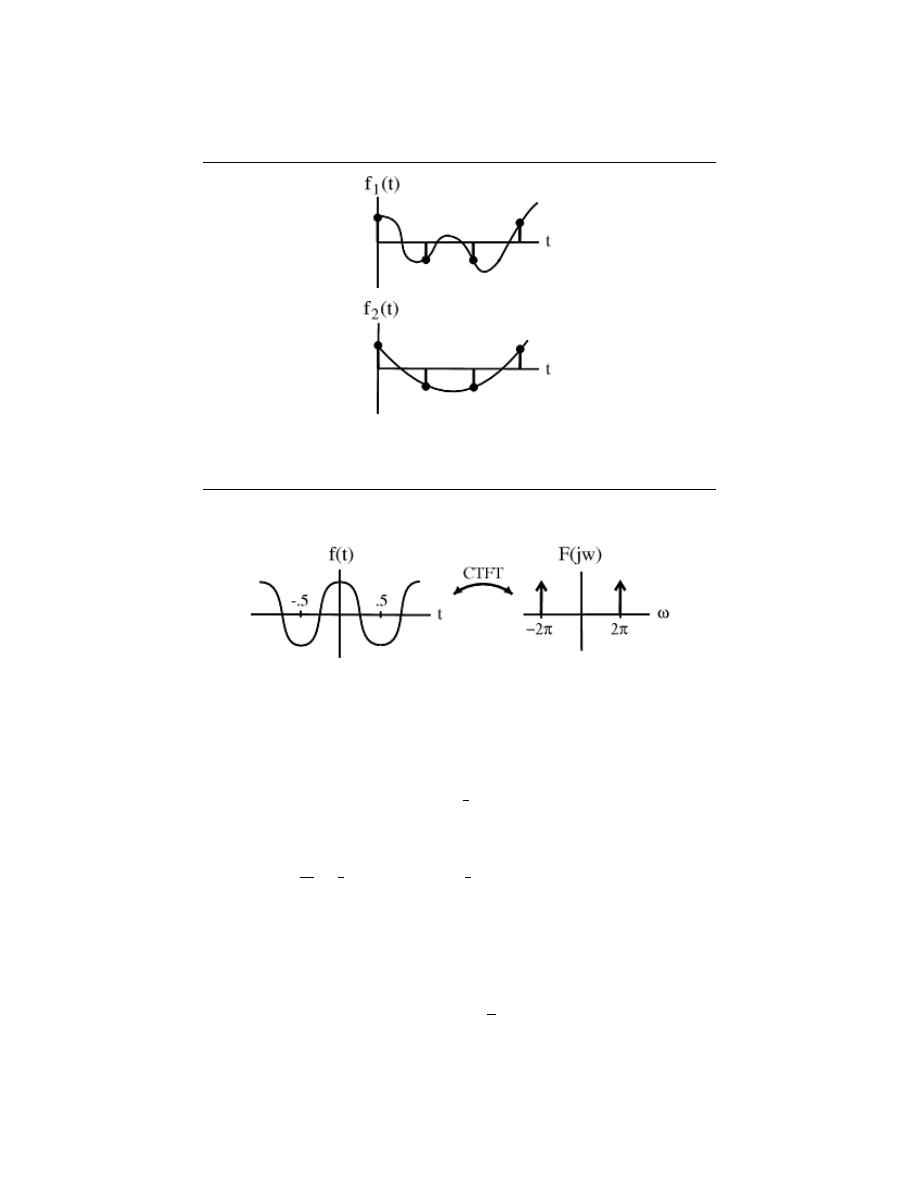

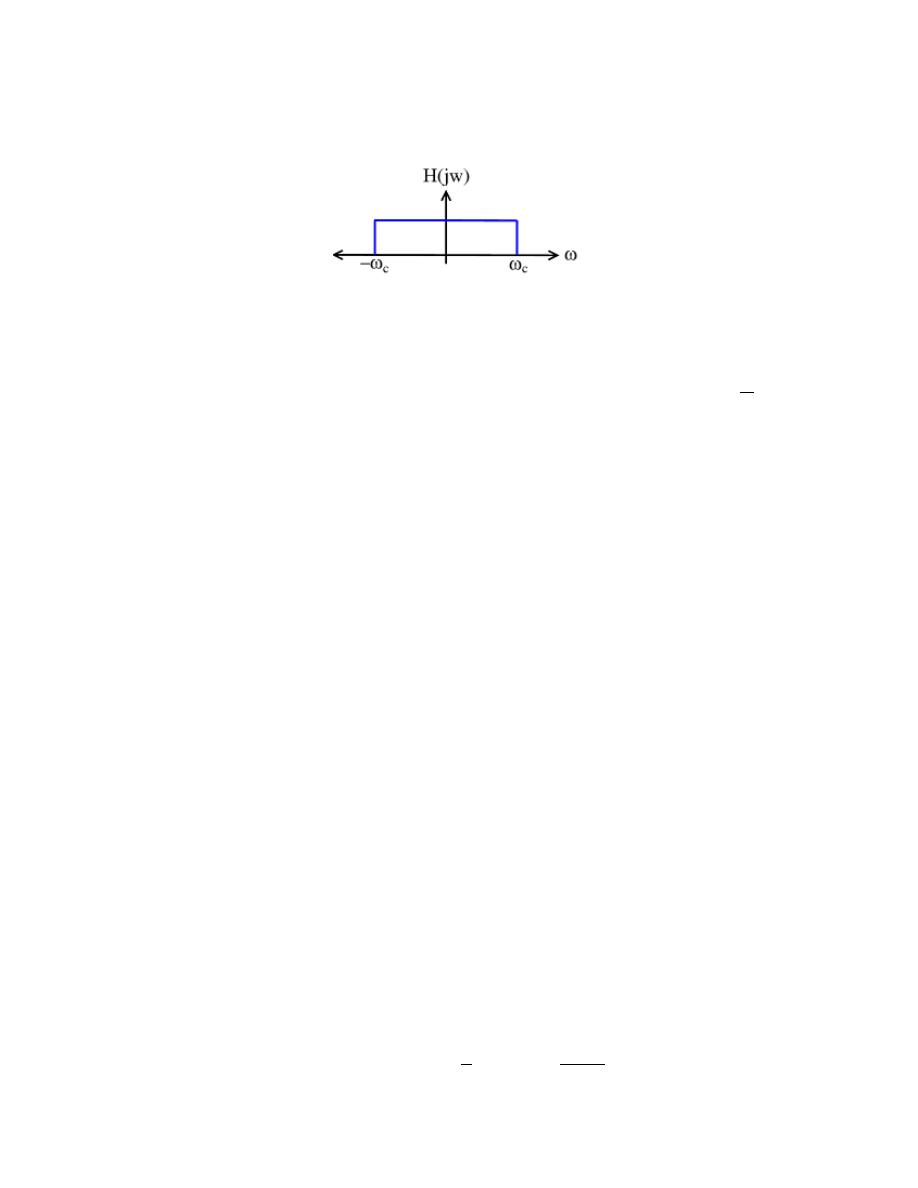

11.2 Reconstruction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 215

11.3 More on Reconstruction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 219

11.4 Nyquist Theorem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 222

11.5 Aliasing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 223

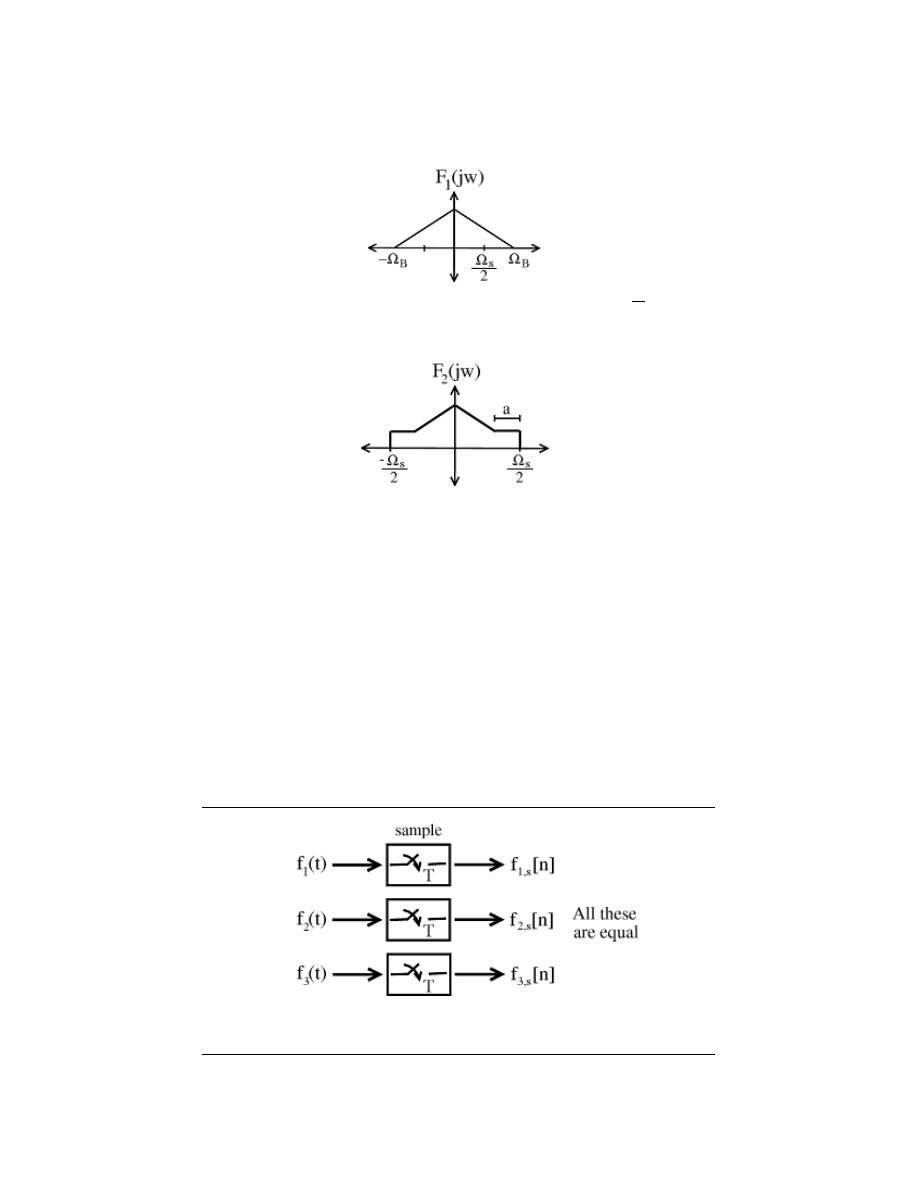

11.6 Anti-Aliasing Filters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 227

11.7 Discrete Time Processing of Continuous TIme Signals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 228

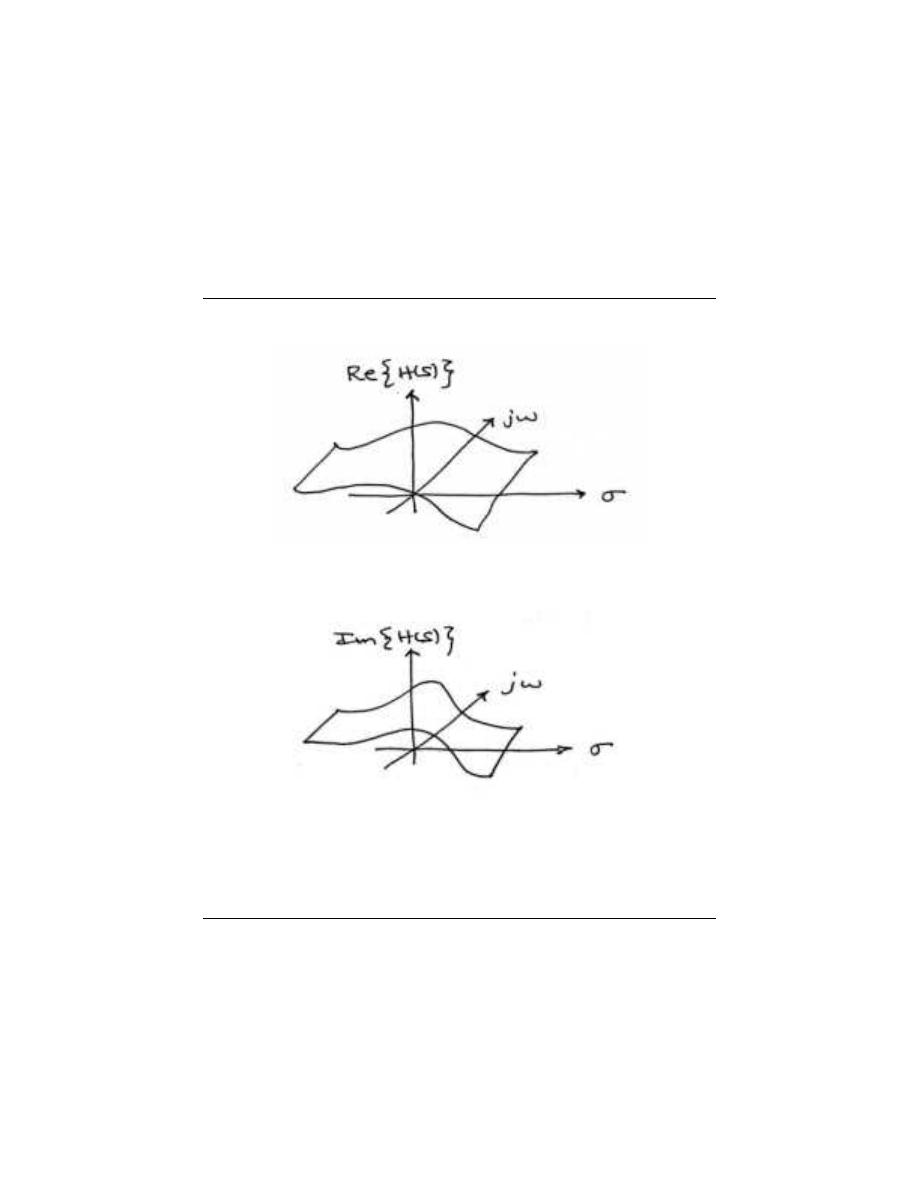

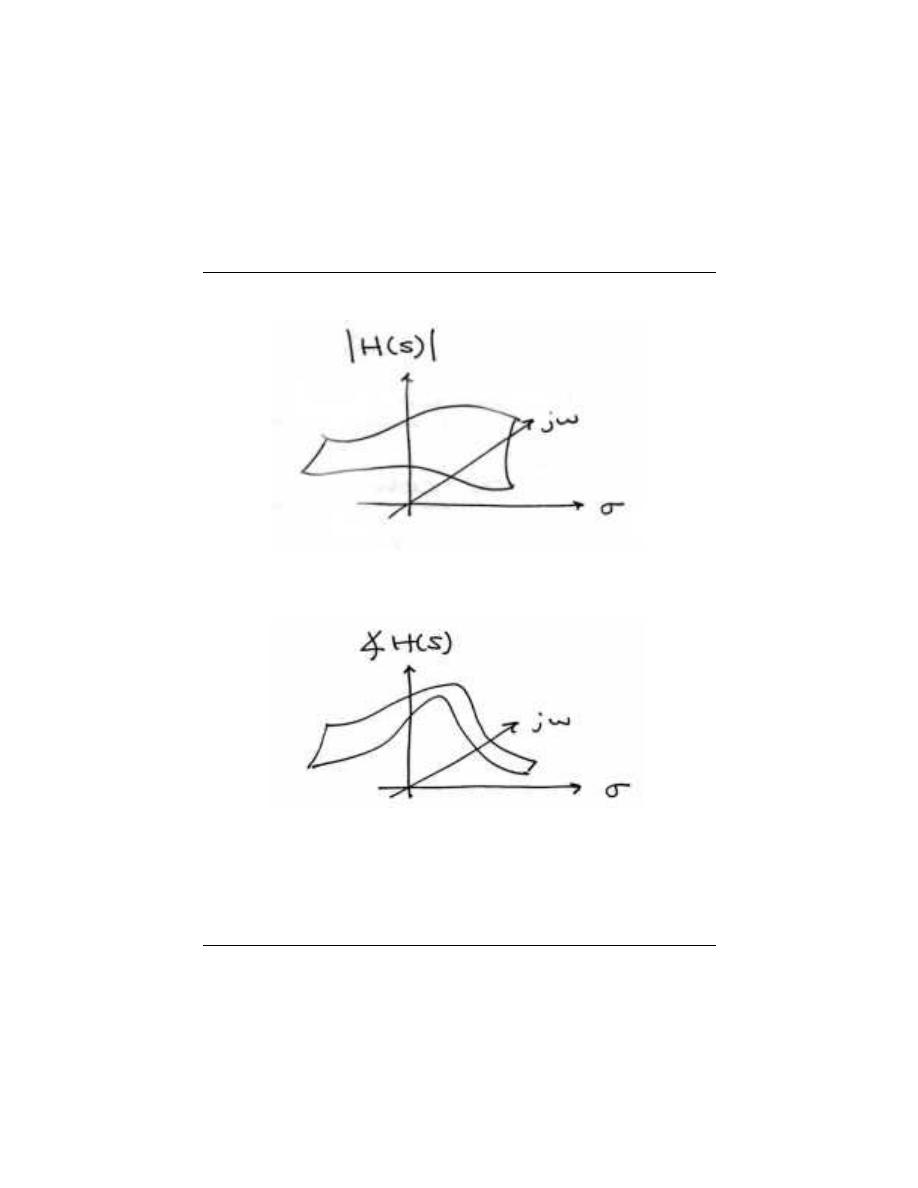

11 Laplace Transform and System Design

12.1 The Laplace Transforms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 235

12.2 Properties of the Laplace Transform . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 239

12.3 Table of Common Laplace Transforms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 239

12.4 Region of Convergence for the Laplace Transform . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 240

12.5 The Inverse Laplace Transform . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 242

12.6 Poles and Zeros . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 243

12 Z-Transform and Digital Filtering

13.1 The Z Transform: Definition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 247

v

13.2 Table of Common Z-Transforms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 251

13.3 Region of Convergence for the Z-transform . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 252

13.4 Inverse Z-Transrom . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 260

13.5 Rational Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 263

13.6 Difference Equation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 265

13.7 Understanding Pole/Zero Plots on the Z-Plane . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 268

13.8 Filter Design using the Pole/Zero Plot of a Z-Transform . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 272

13 Homework Sets

14.1 Homework #1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 277

14.2 Homework #1 Solutions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 280

vi

1

1 Cover Page

.1.1 Signals and Systems: Elec 301

summary:

This course deals with signals, systems, and transforms, from their

theoretical mathematical foundations to practical implementation in circuits and

computer algorithms. At the conclusion of ELEC 301, you should have a deep

understanding of the mathematics and practical issues of signals in continuous and

discrete time, linear time-invariant systems, convolution, and Fourier transforms.

Instructor: Richard Baraniuk

1

Teaching Assistant: Michael Wakin

2

Course Webpage: Rice University Elec301

3

Module Authors: Richard Baraniuk, Justin Romberg, Michael Haag, Don Johnson

Course PDF File: Currently Unavailable

1

http://www.ece.rice.edu/∼richb/

2

http://www.owlnet.rice.edu/∼wakin/

3

http://dsp.rice.edu/courses/elec301

2

Chapter 1

Introduction

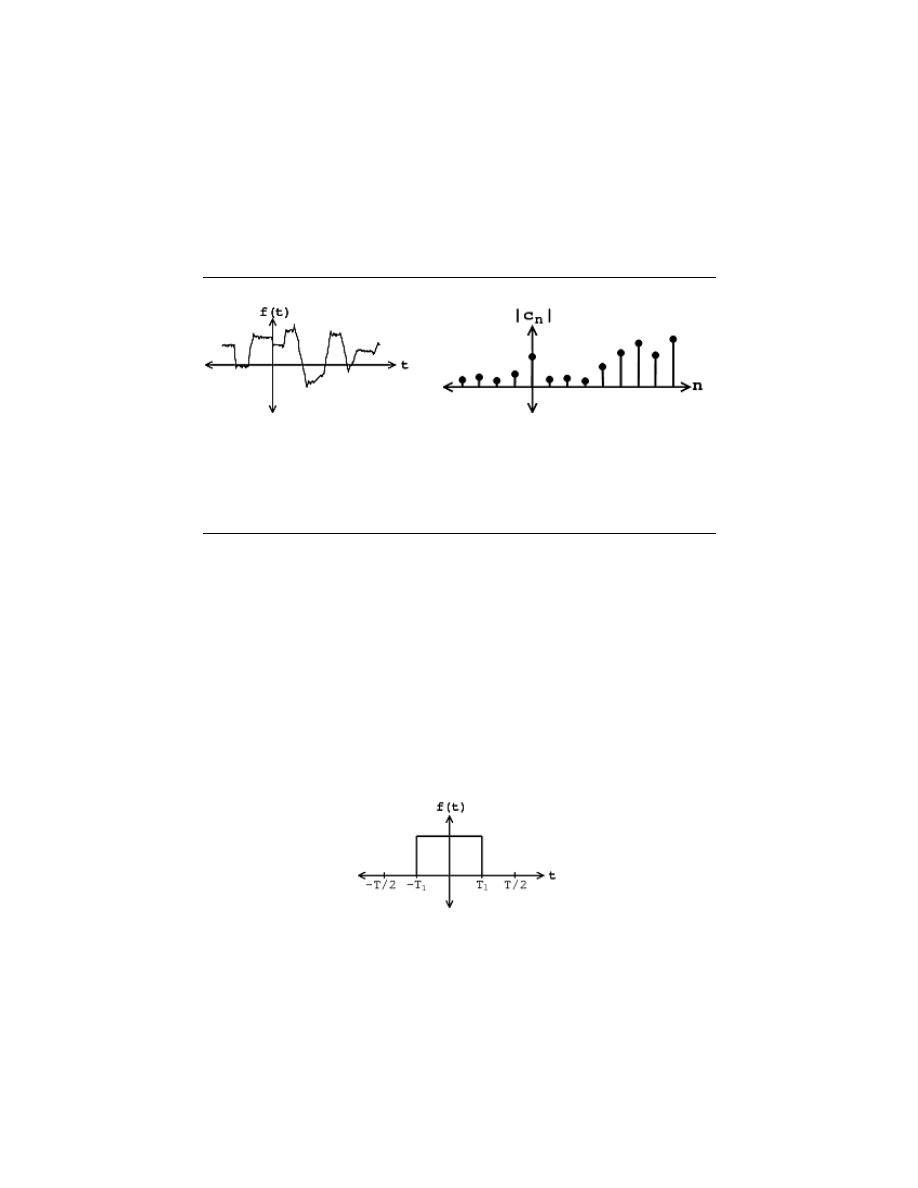

2.1 Signals Represent Information

Whether analog or digital, information is represented by the fundamental quantity in elec-

trical engineering: the signal . Stated in mathematical terms, a signal is merely a function.

Analog signals are continuous-valued; digital signals are discrete-valued. The independent

variable of the signal could be time (speech, for example), space (images), or the integers

(denoting the sequencing of letters and numbers in the football score).

1.1.1 Analog Signals

Analog signals are usually signals defined over continuous independent variable(s). Speech

is produced by your vocal cords exciting acoustic resonances in your vocal tract. The result

is pressure waves propagating in the air, and the speech signal thus corresponds to a function

having independent variables of space and time and a value corresponding to air pressure:

s (x, t) (Here we use vector notation x to denote spatial coordinates). When you record

someone talking, you are evaluating the speech signal at a particular spatial location, x

0

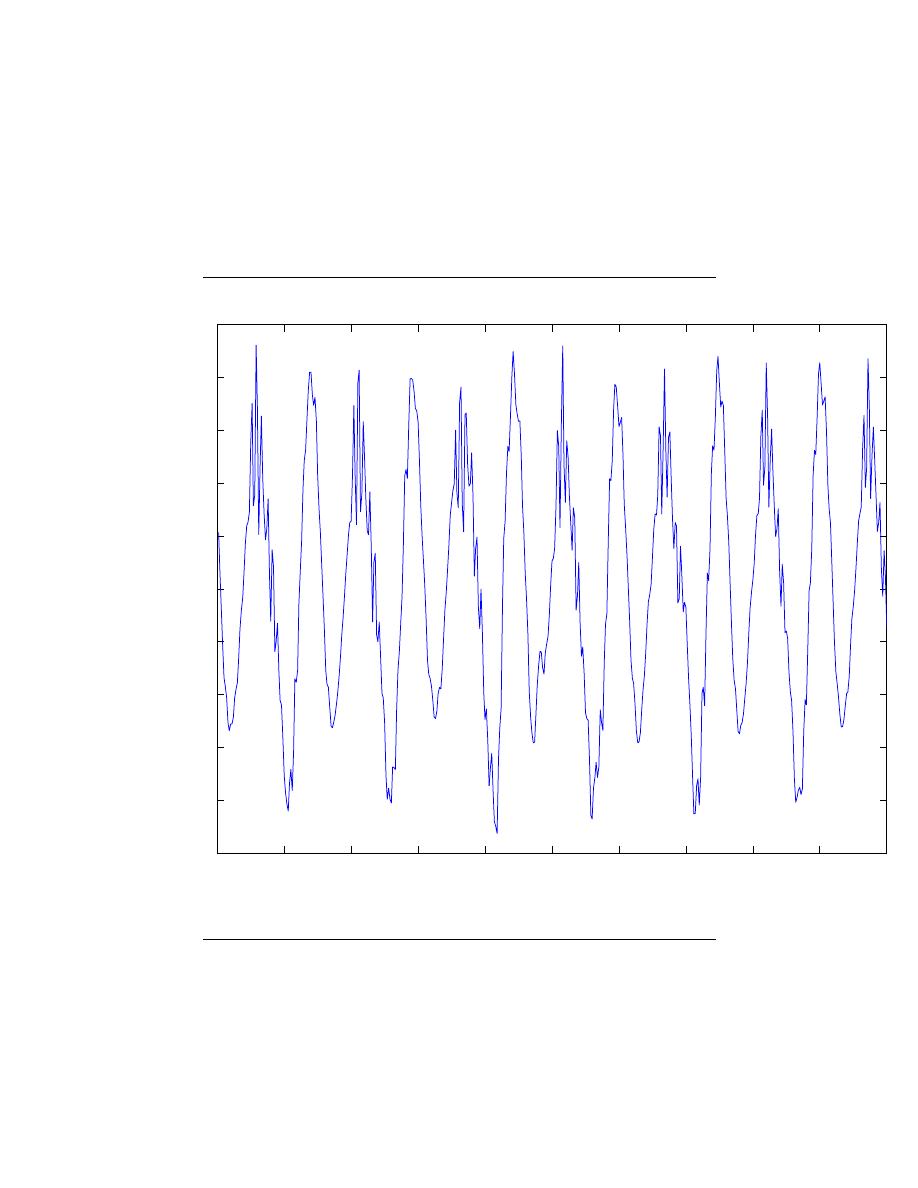

say. An example of the resulting waveform s (x

0

, t) is shown in this figure (Figure 1.1).

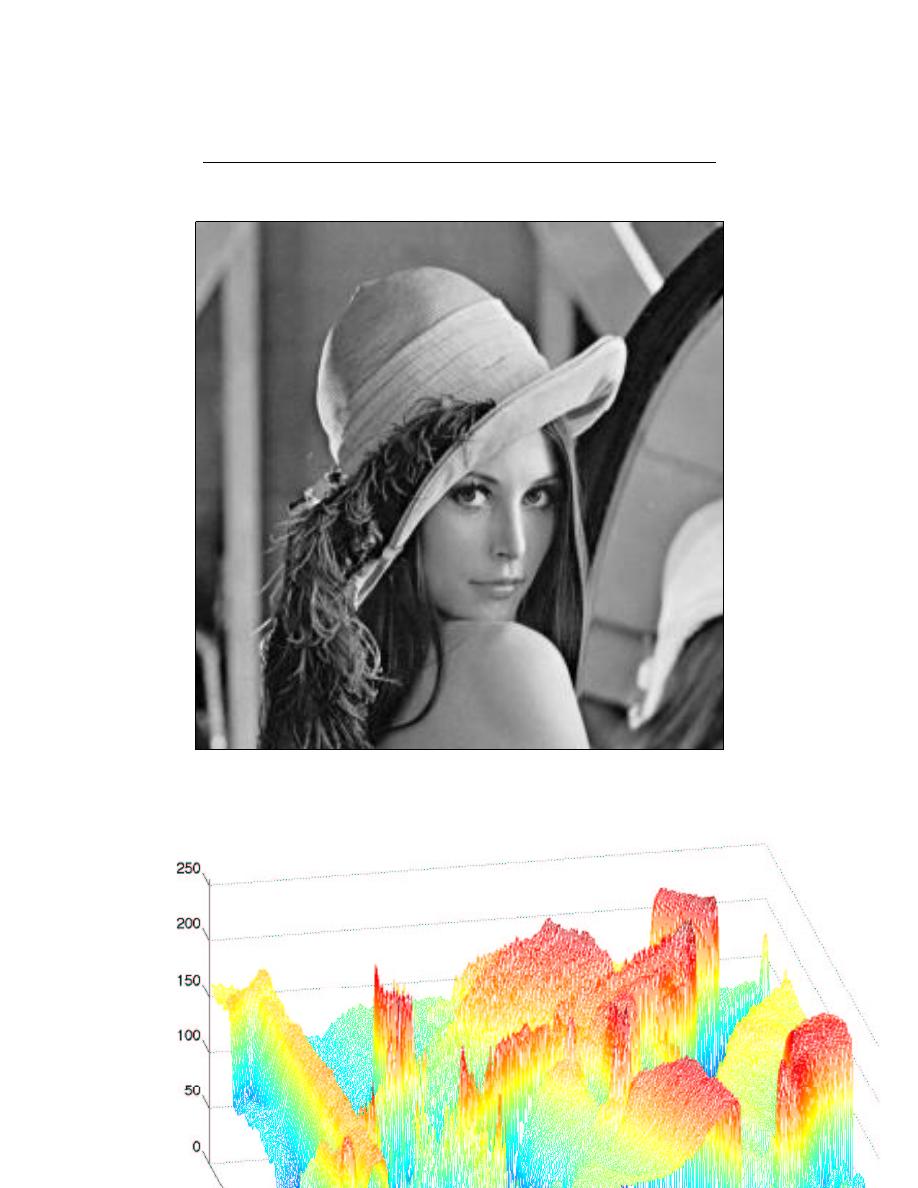

Photographs are static, and are continuous-valued signals defined over space. Black-

and-white images have only one value at each point in space, which amounts to its optical

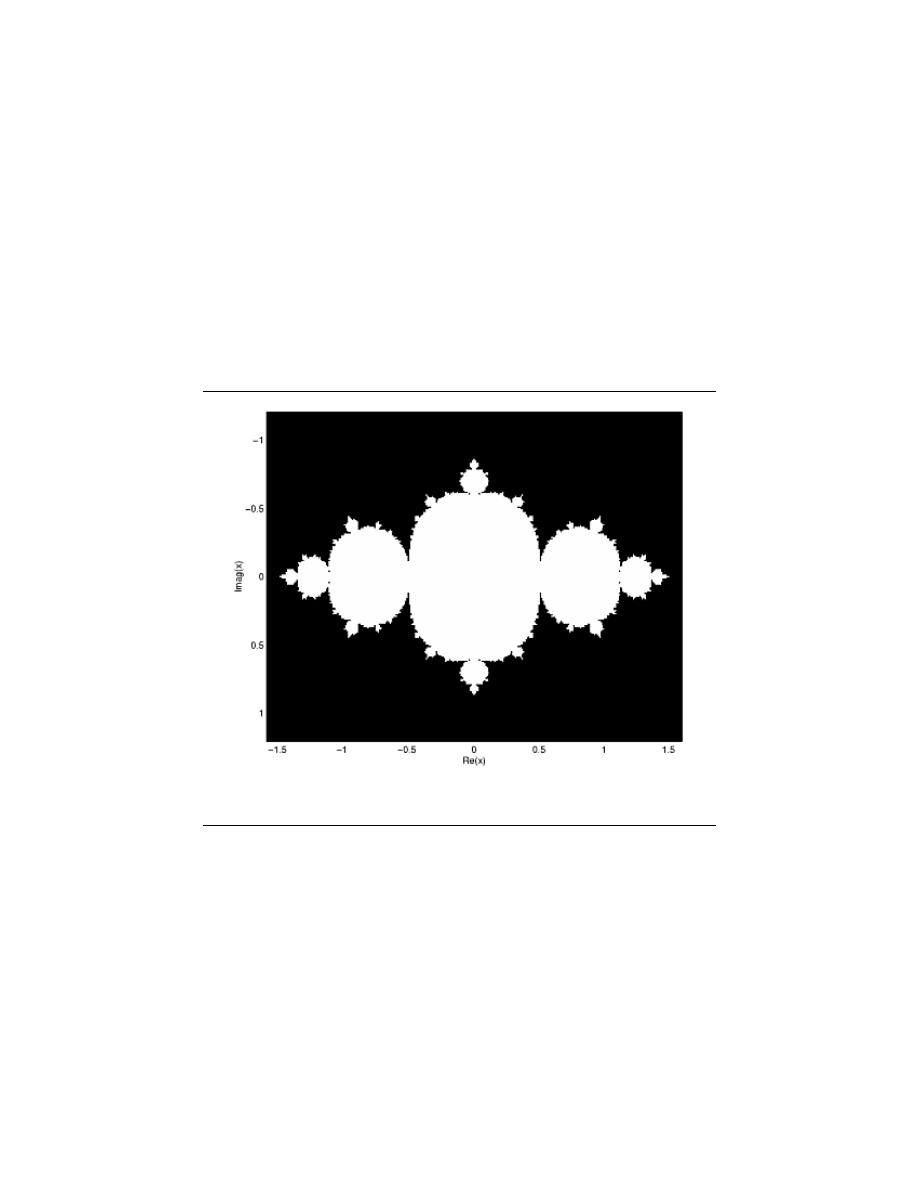

reflection properties. In Figure 1.2, an image is shown, demonstrating that it (and all other

images as well) are functions of two independent spatial variables.

Color images have values that express how reflectivity depends on the optical spectrum.

Painters long ago found that mixing together combinations of the so-called primary colors–

red, yellow and blue–can produce very realistic color images. Thus, images today are usually

thought of as having three values at every point in space, but a different set of colors is used:

How much of red, green and blue is present. Mathematically, color pictures are multivalued–

vector-valued–signals: s (x) = (r (x) , g (x) , b (x))

T

.

Interesting cases abound where the analog signal depends not on a continuous variable,

such as time, but on a discrete variable. For example, temperature readings taken every

hour have continuous–analog–values, but the signal’s independent variable is (essentially)

the integers.

1.1.2 Digital Signals

The word ”digital” means discrete-valued and implies the signal has an integer-valued inde-

pendent variable. Digital information includes numbers and symbols (characters typed on

3

4

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

Speech Example

-0.5

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

Amplitude

Figure 1.1:

A speech signal’s amplitude relates to tiny air pressure variations. Shown

is a recording of the vowel ”e” (as in ”speech”).

5

Lena

(a)

(b)

Figure 1.2:

On the left is the classic Lena image, which is used ubiquitously as a test

image. It contains straight and curved lines, complicated texture, and a face. On the

right is a perspective display of the Lena image as a signal: a function of two spatial

variables. The colors merely help show what signal values are about the same size. In

this image, signal values range between 0 and 255; why is that?

6

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

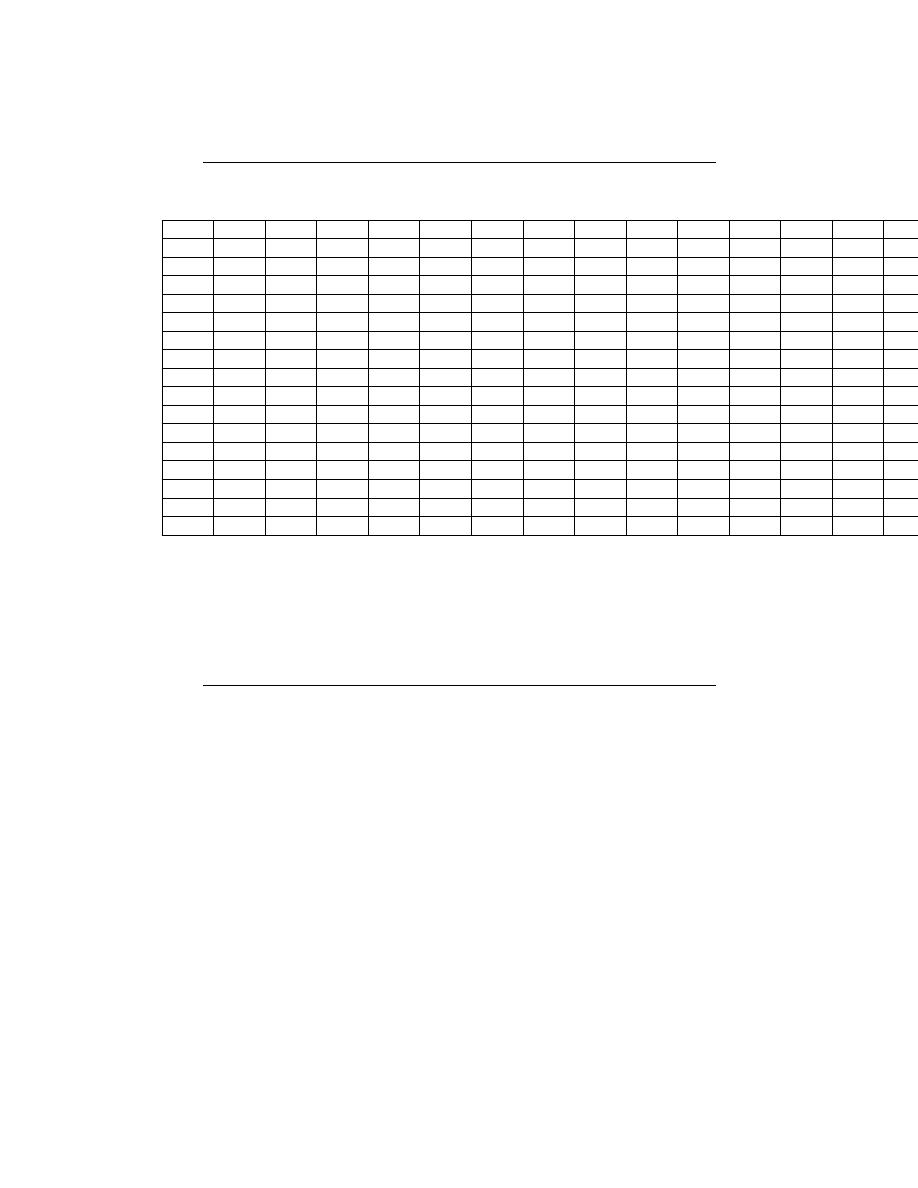

Ascii Table

number character

number character

number character

number character

number character

number character

number character

number character

00

nul

01

soh

02

stx

03

etx

04

eot

05

enq

06

ack

07

bel

08

bs

09

ht

0A

nl

0B

vt

0C

np

0D

cr

0E

so

0F

si

10

dle

11

dc1

12

dc2

13

dc3

14

dc4

15

nak

16

syn

17

etb

18

car

19

em

1A

sub

1B

esc

1C

fs

1D

gs

1E

rs

1F

us

20

sp

21

!

22

”

23

#

24

$

25

%

26

&

27

’

28

(

29

)

2A

*

2B

+

2C

,

2D

-

2E

.

2F

/

30

0

31

1

32

2

33

3

34

4

35

5

36

6

37

7

38

8

39

9

3A

:

3B

;

3C

<

3D

=

3E

>

3F

?

40

@

41

A

42

B

43

C

44

D

45

E

46

F

47

G

48

H

49

I

4A

J

4B

K

4C

L

4D

M

4E

N

4F

0

50

P

51

Q

52

R

53

S

54

T

55

U

56

V

57

W

58

X

59

Y

5A

Z

5B

[

5C

\

5D

]

5E

ˆ

5F

60

’

61

a

62

b

63

c

64

d

65

e

66

f

67

g

68

h

69

i

6A

j

6B

k

6C

l

6D

m

6E

n

6F

o

70

p

71

q

72

r

73

s

74

t

75

u

76

v

77

w

78

x

79

y

7A

z

7B

{

7C

—

7D

}

7E

∼

7F

del

Figure 1.3:

The ASCII translation table shows how standard keyboard characters

are represented by integers.

This table displays the so-called 7-bit code (how many

characters in a seven-bit code?); extended ASCII has an 8-bit code. The numeric codes

are represented in hexadecimal (base-16) notation. The mnemonic characters correspond

to control characters, some of which may be familiar (like cr for carriage return) and

some not ( bel means a ”bell”).

the keyboard, for example). Computers rely on the digital representation of information to

manipulate and transform information. Symbols do not have a numeric value, and each is

represented by a unique number. The ASCII character code has the upper- and lowercase

characters, the numbers, punctuation marks, and various other symbols represented by a

seven-bit integer. For example, the ASCII code represents the letter a as the number 97 and

the letter A as 65. Figure 1.3 shows the international convention on associating characters

with integers.

Chapter 2

Signals and Systems: A First

Look

3.1 System Classifications and Properties

2.1.1 Introduction

In this module some of the basic classifications of systems will be briefly introduced and the

most important properties of these systems are explained. As can be seen, the properties of

a system provide an easy way to separate one system from another. Understanding these

basic difference’s between systems, and their properties, will be a fundamental concept used

in all signal and system courses, such as digital signal processing (DSP). Once a set of

systems can be identified as sharing particular properties, one no longer has to deal with

proving a certain characteristic of a system each time, but it can simply be accepted do the

the systems classification. Also remember that this classification presented here is neither

exclusive (systems can belong to several different classificatins) nor is it unique (there are

other methods of classification).

2.1.2 Classification of Systems

Along with the classification of systems below, it is also important to understand the Clas-

sification of Signals.

2.1.2.1 Continuous vs. Discrete

This may be the simplest classification to understand as the idea of discrete-time and

continuous-time is one of the most fundamental properties to all of signals and system.

A system where the input and output signals are continuous is a continuous system , and

one where the input and ouput signals are discrete is a discrete system .

2.1.2.2 Linear vs. Nonlinear

A linear system is any system that obeys the properties of scaling (homogeneity) and

superposition (additivity), while a nonlinear system is any system that does not obey at

least one of these.

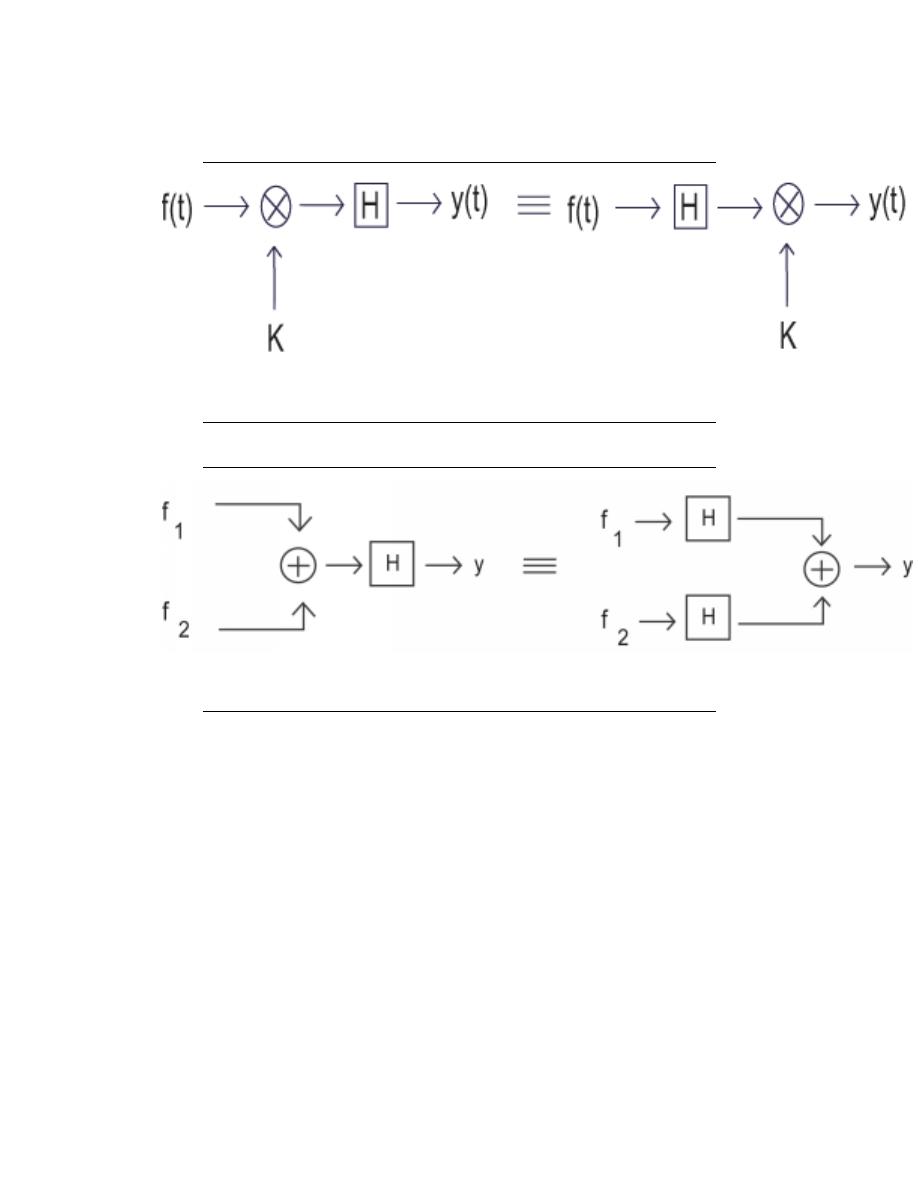

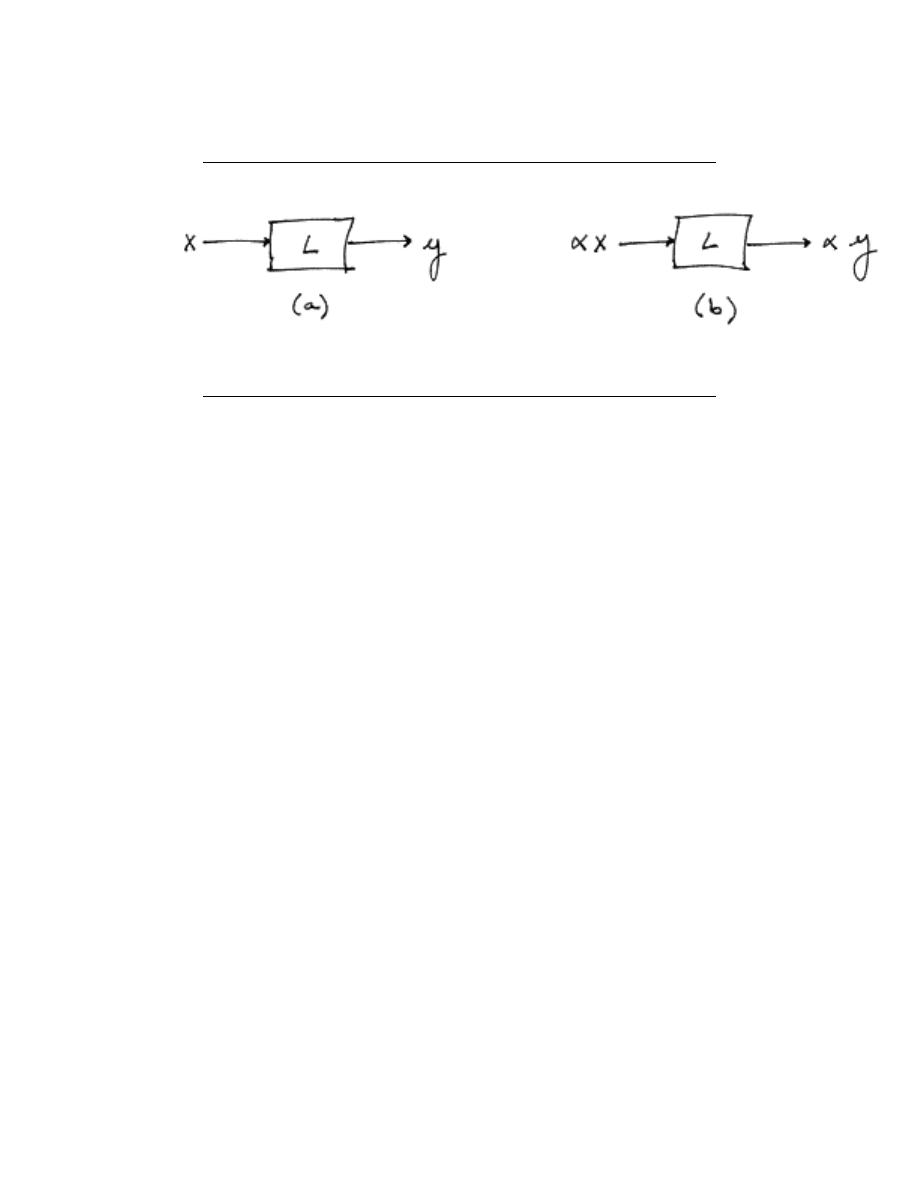

To show that a system H obeys the scaling property is to show that

H (kf (t)) = kH (f (t))

(2.1)

7

8

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

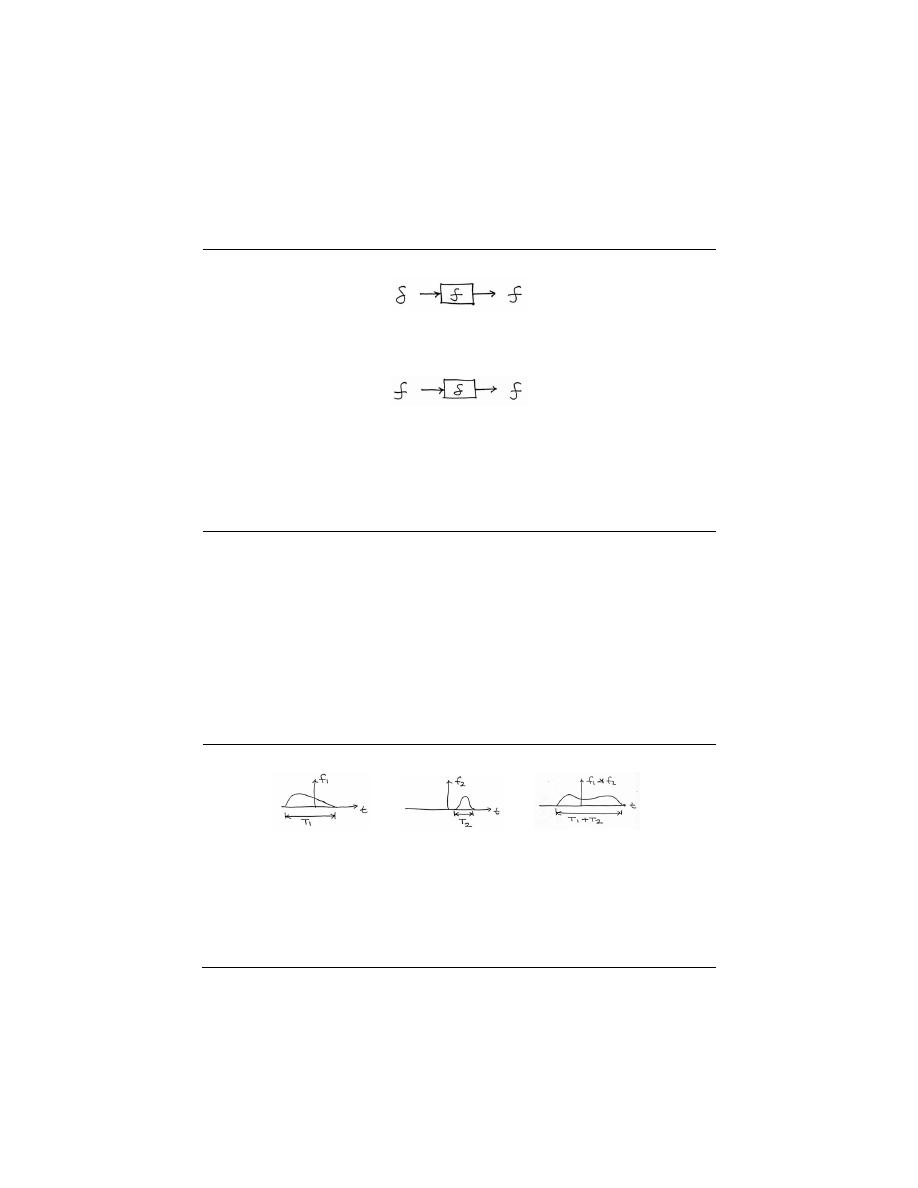

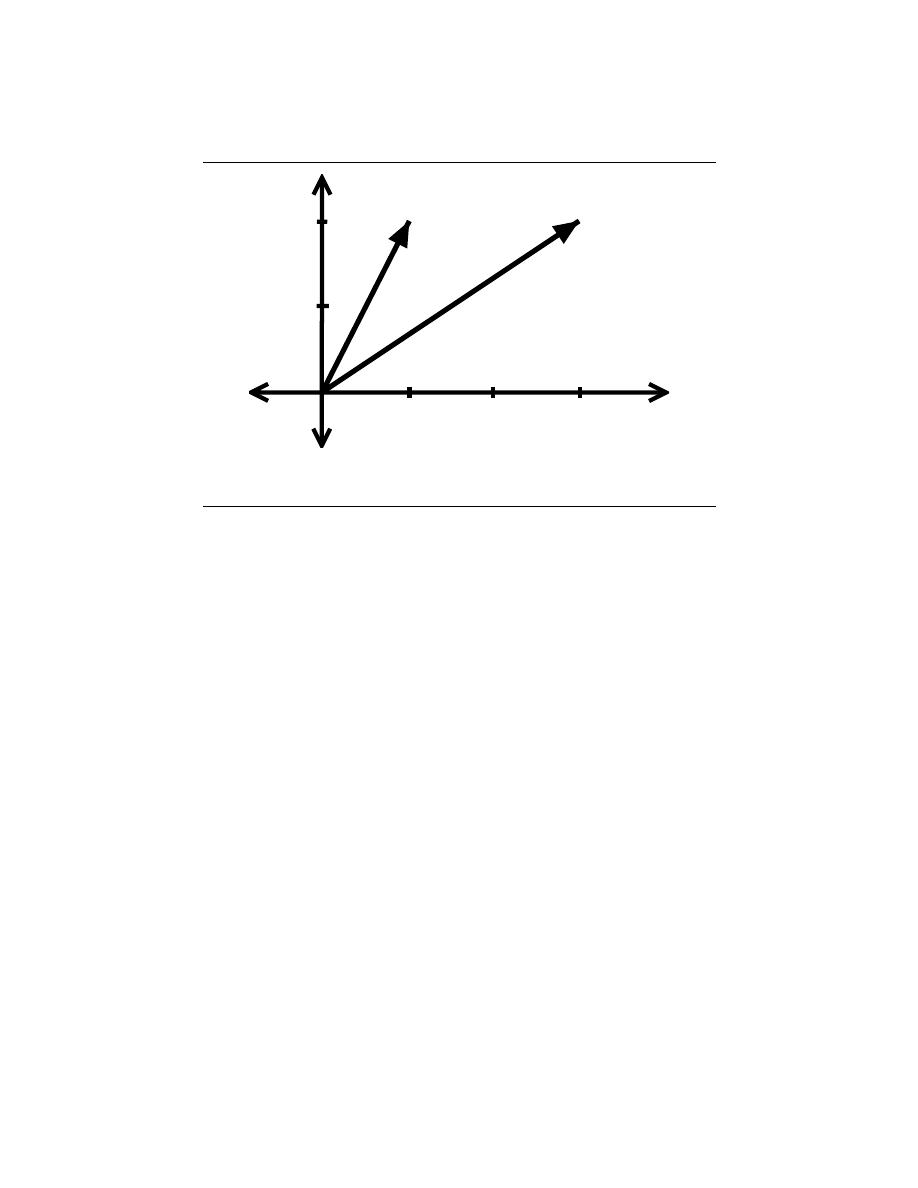

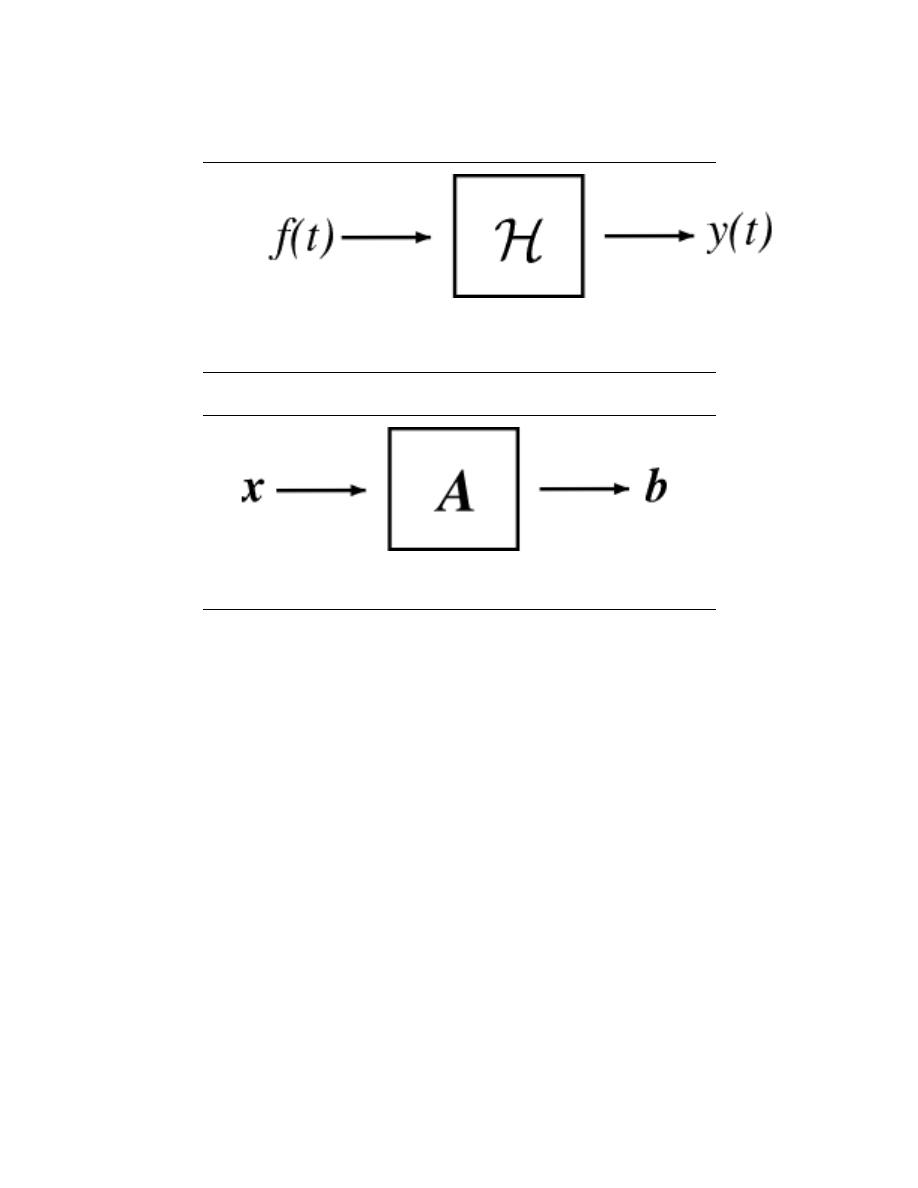

Figure 2.1: A block diagram demonstrating the scaling property of linearity

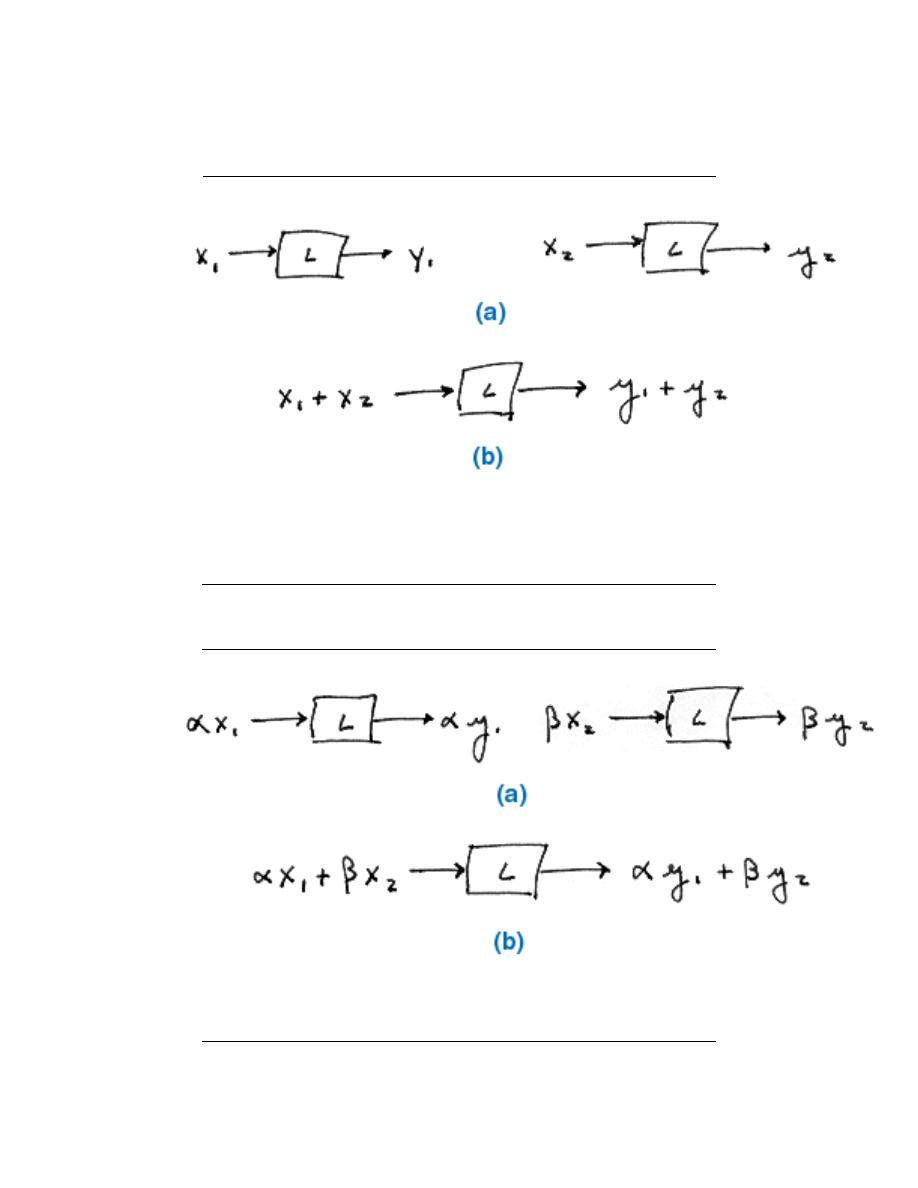

Figure 2.2: A block diagram demonstrating the superposition property of linearity

To demonstrate that a system H obeys the superposition property of linearity is to show

that

H (f

1

(t) + f

2

(t)) = H (f

1

(t)) + H (f

2

(t))

(2.2)

It is possible to check a system for linearity in a single (though larger) step. To do this,

simply combine the first two steps to get

H (k

1

f

1

(t) + k

2

f

2

(t)) = k

2

H (f

1

(t)) + k

2

H (f

2

(t))

(2.3)

2.1.2.3 Time Invariant vs. Time Variant

A time invariant system is one that does not depend on when it occurs: the shape of the

output does not change with a delay of the input. That is to say that for a system H where

H (f (t)) = y (t), H is time invariant if for all T

H (f (t − T )) = y (t − T )

(2.4)

9

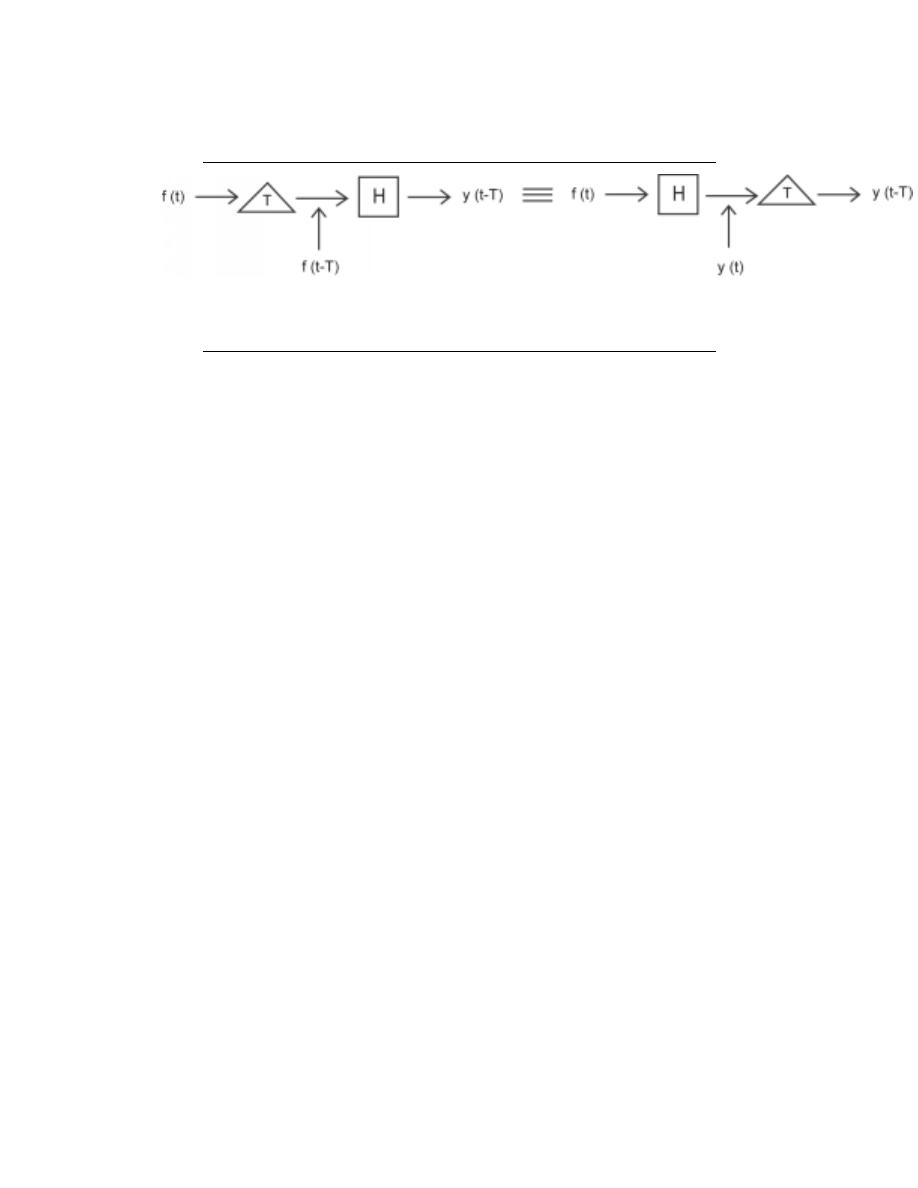

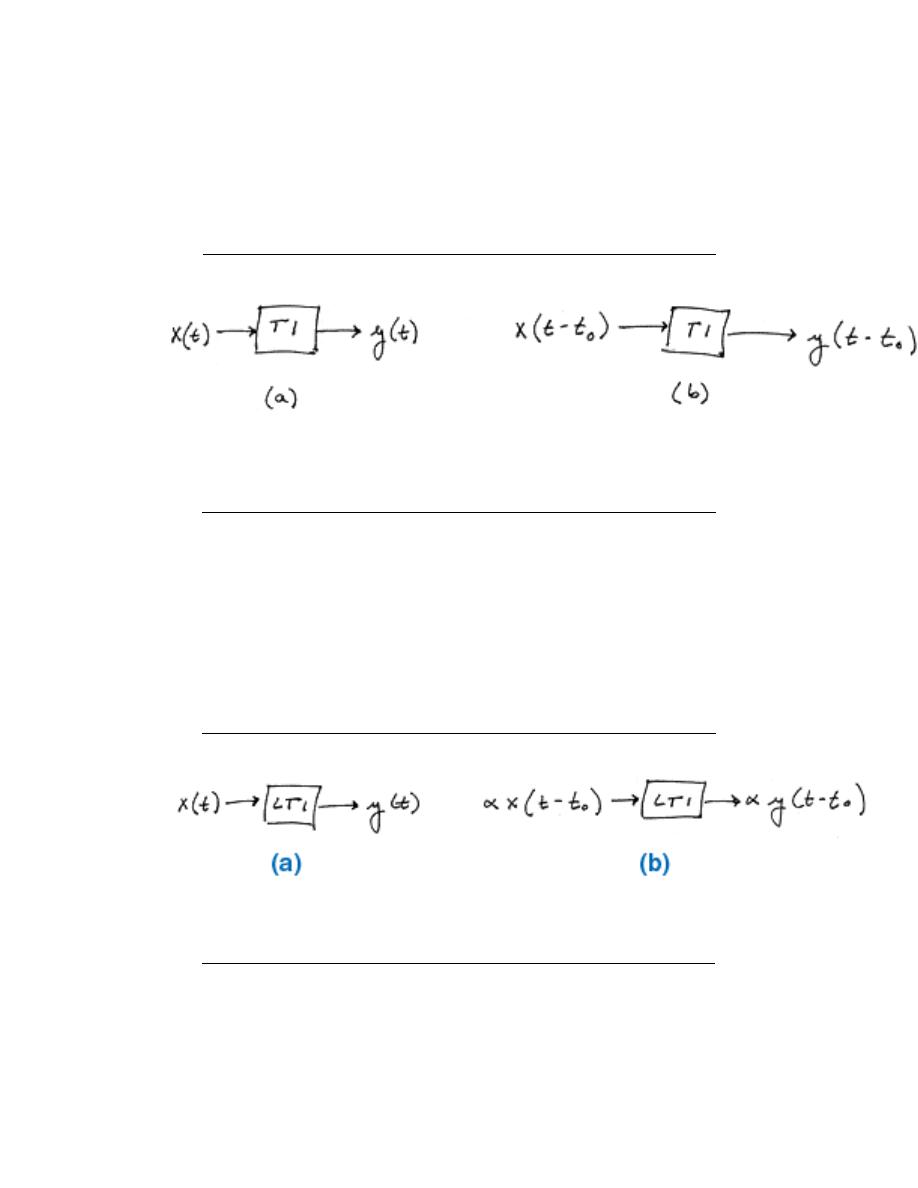

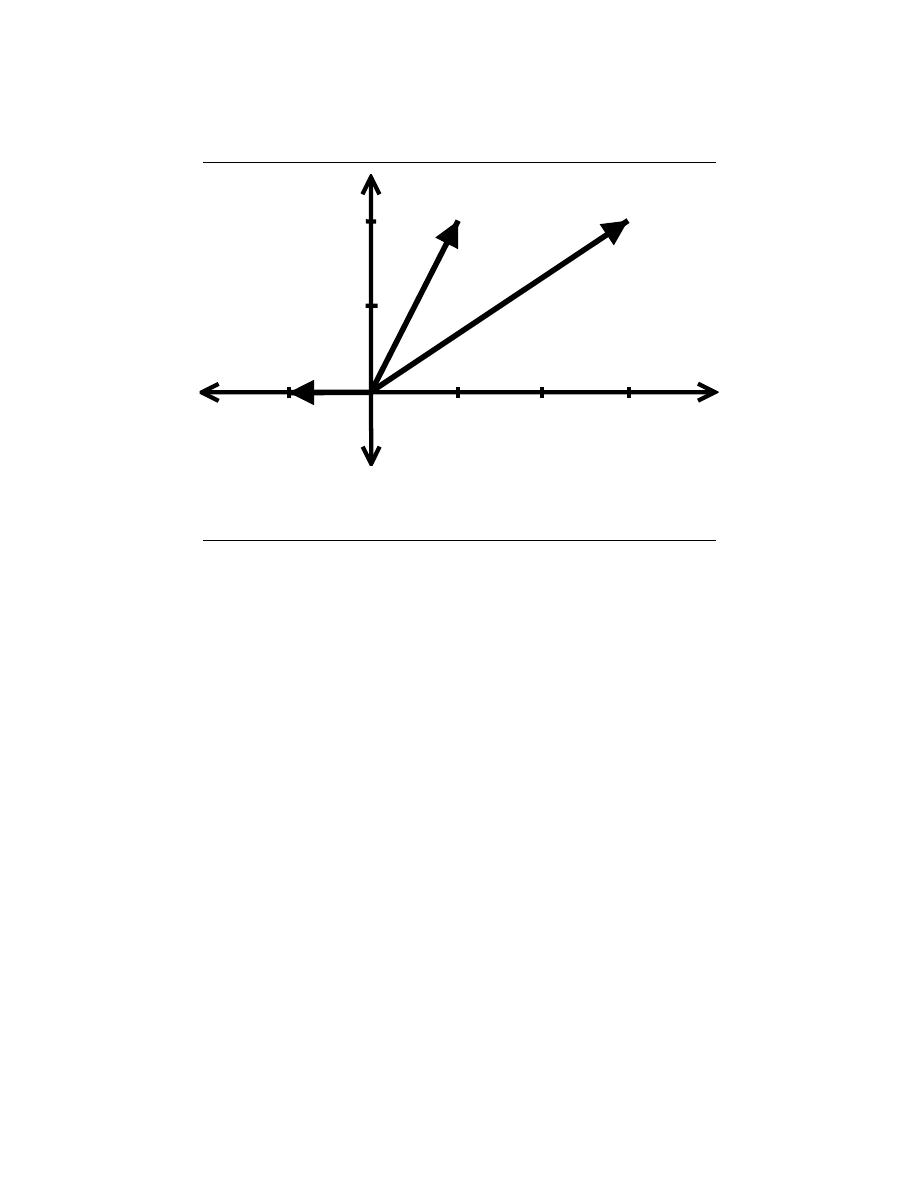

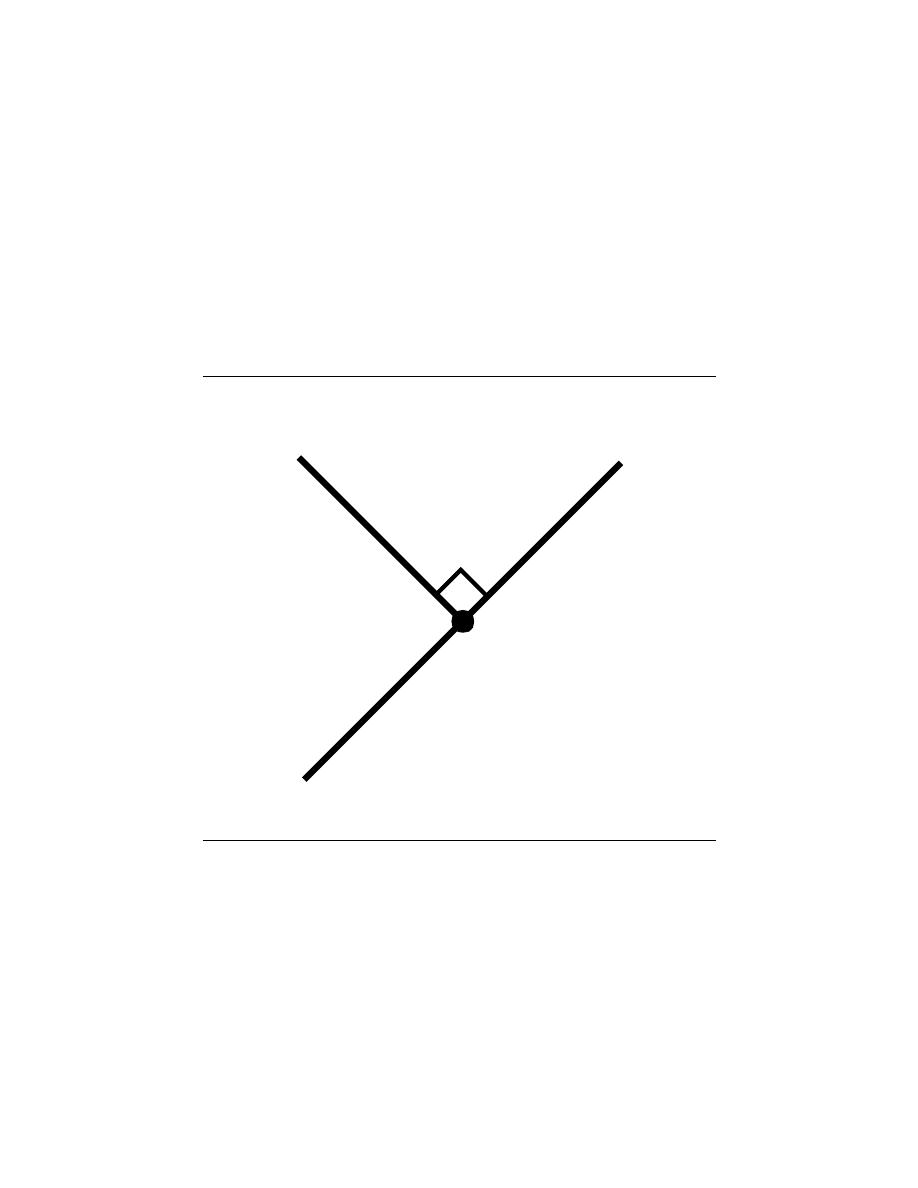

Figure 2.3:

This block diagram shows what the condition for time invariance. The

output is the same whether the delay is put on the input or the output.

When this property does not hold for a system, then it is said to be time variant , or

time-varying.

2.1.2.4 Causal vs. Noncausal

A causal system is one that is nonanticipative ; that is, the output may depend on current

and past inputs, but not future inputs. All ”realtime” systems must be causal, since they

can not have future inputs available to them.

One may think the idea of future inputs does not seem to make much physical sense;

however, we have only been dealing with time as our dependent variable so far, which is

not always the case. Imagine rather that we wanted to do image processing. Then the

dependent variable might represent pixels to the left and right (the ”future”) of the current

position on the image, and we would have a noncausal system.

2.1.2.5 Stable vs. Unstable

A stable system is one where the output does not diverge as long as the input does not

diverge. A bounded input produces a bounded output. It is from this property that this

type of system is referred to as bounded input-bounded output (BIBO) stable.

Representing this in a mathematical way, a stable system must have the following prop-

erty, where x (t) is the input and y (t) is the output. The output must satisfy the condition

|y (t) | ≤ M

y

< ∞

(2.5)

when we have an input to the system that can be described as

|x (t) | ≤ M

x

< ∞

(2.6)

M

x

and M

y

both represent a set of finite positive numbers and these relationships hold for

all of t.

If these conditions are not met, i.e. a system’s output grows without limit (diverges)

from a bounded input, then the system is unstable .

3.2 Properties of Systems

2.2.1 ”Linear Systems”

If a system is linear, this means that when an input to a given system is scaled by a value,

the output of the system is scaled by the same amount.

10

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

(a)

(b)

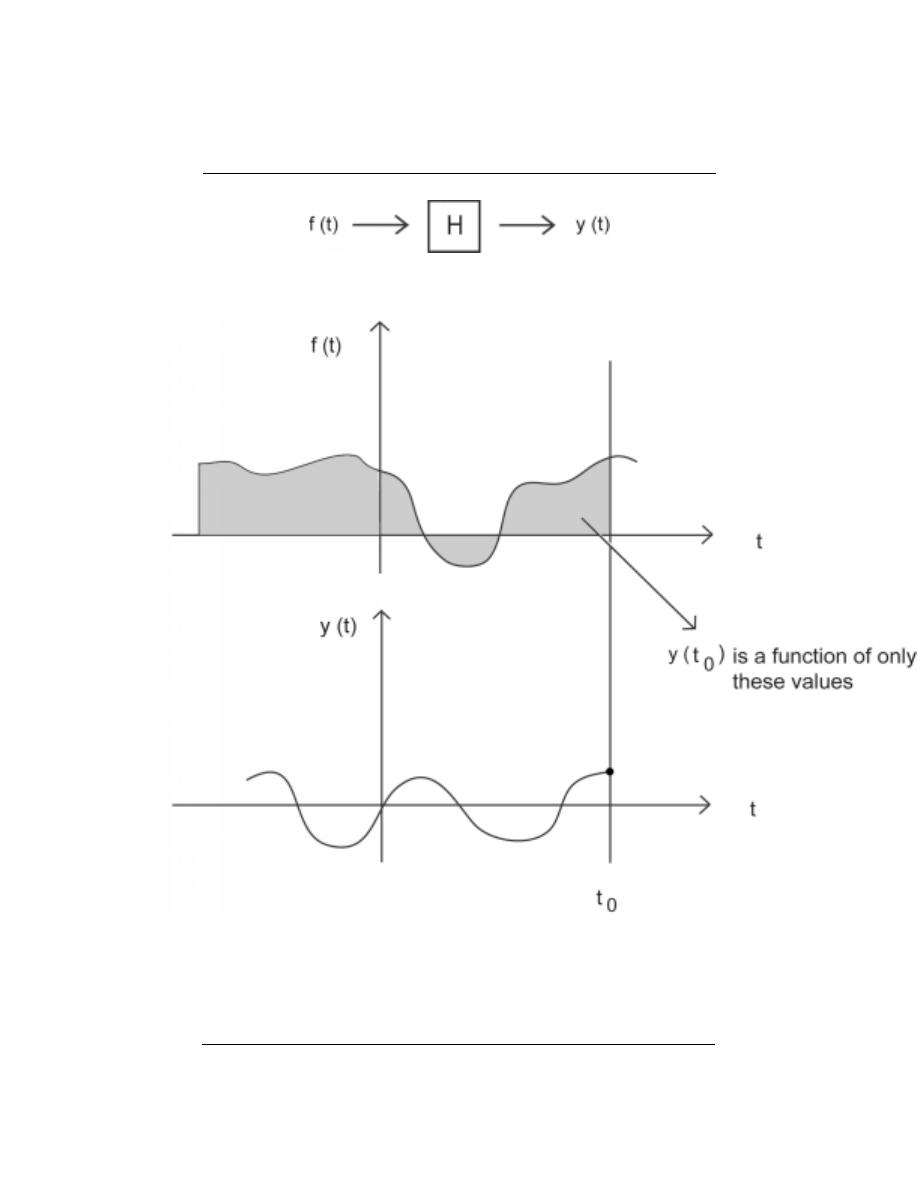

Figure 2.4:

(a) For a typical system to be causal... (b) ...the output at time t

0

, y (t

0

),

can only depend on the portion of the input signal before t

0

.

11

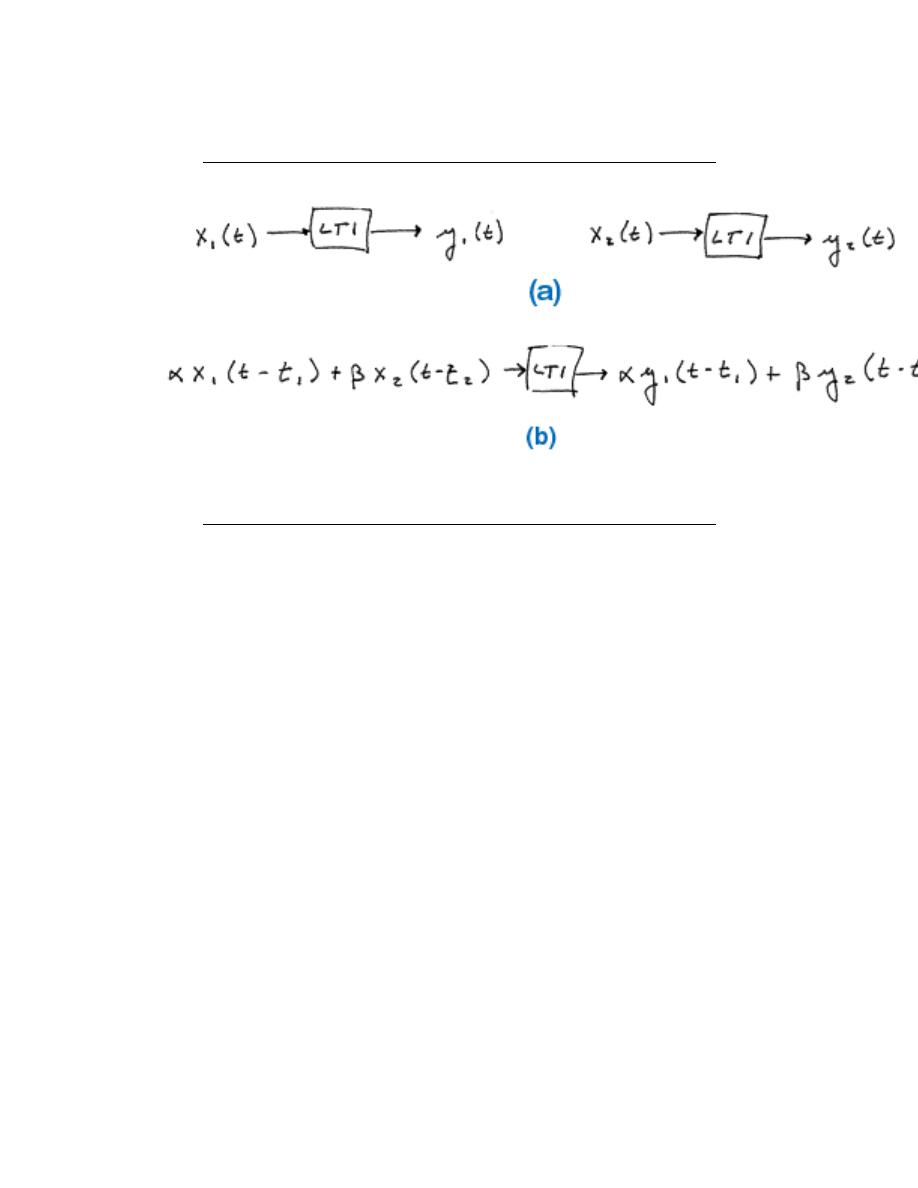

Linear Scaling

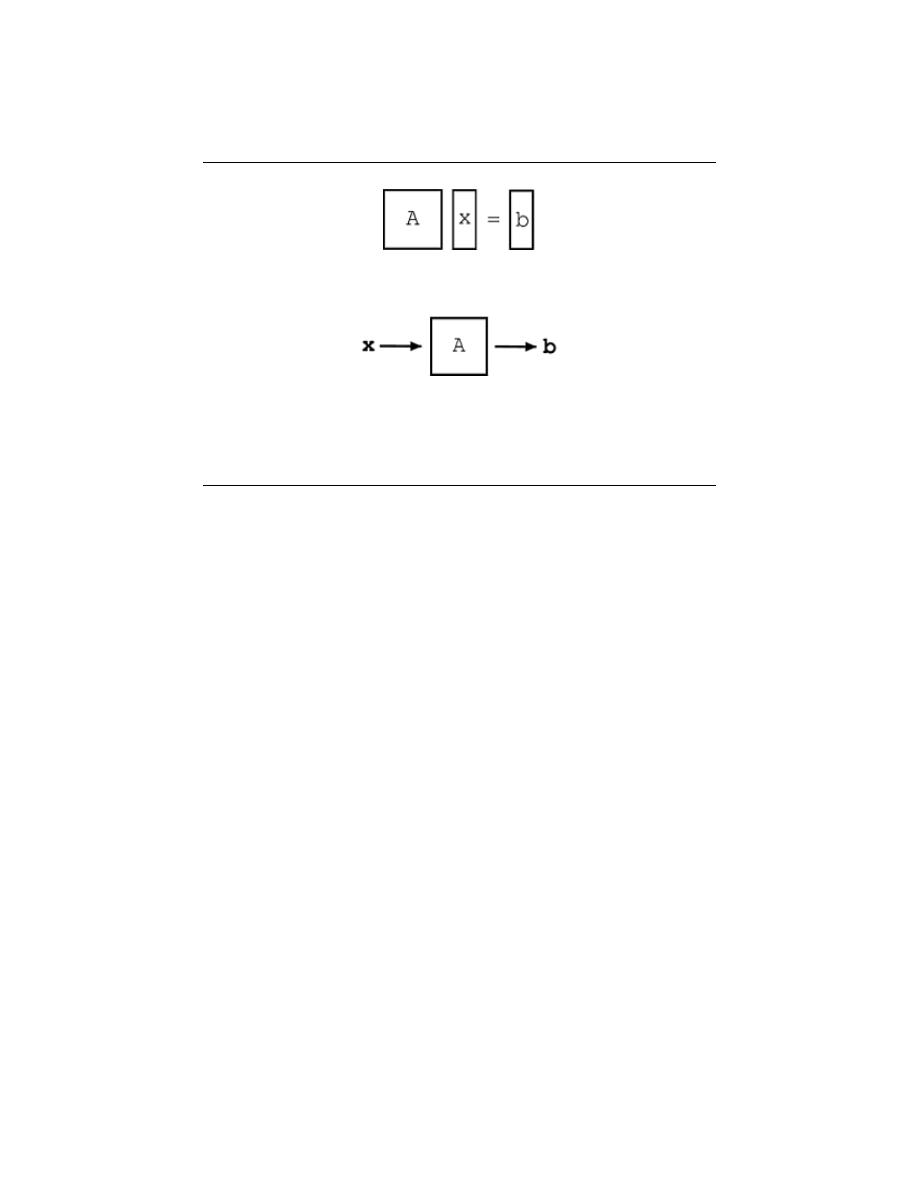

Figure 2.5

In part (a) of the figure above, an input x to the linear system L gives the output y If x

is scaled by a value α and passed through this same system, as in part (b), the output will

also be scaled by α.

A linear system also obeys the principle of superposition. This means that if two inputs

are added together and passed through a linear system, the output will be the sum of the

individual inputs’ outputs.

That is, if (a) is true, then (b) is also true for a linear system. The scaling property

mentioned above still holds in conjunction with the superposition principle. Therefore, if

the inputs x and y are scaled by factors α and β, respectively, then the sum of these scaled

inputs will give the sum of the individual scaled outputs:

2.2.2 ”Time-Invariant Systems”

A time-invariant system has the property that a certain input will always give the same

output, without regard to when the input was applied to the system.

In this figure, x (t) and x (t − t

0

) are passed through the system TI. Because the system

TI is time-invariant, the inputs x (t) and x (t − t

0

) produce the same output. The only

difference is that the output due to x (t − t

0

) is shifted by a time t

0

.

Whether a system is time-invariant or time-varying can be seen in the differential equa-

tion (or difference equation) describing it. Time-invariant systems are modeled with constant

coefficient equations. A constant coefficient differential (or difference) equation means that

the parameters of the system are not changing over time and an input now will give the

same result as the same input later.

2.2.3 ”Linear Time-Invariant (LTI) Systems”

Certain systems are both linear and time-invariant, and are thus referred to as LTI systems.

As LTI systems are a subset of linear systems, they obey the principle of superposition. In

the figure below, we see the effect of applying time-invariance to the superposition definition

in the linear systems section above.

12

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

Superposition Principle

Figure 2.6: If (a) is true, then the principle of superposition says that (b) is true as

well. This holds for linear systems.

Superposition Principle with Linear Scaling

Figure 2.7: Given (a) for a linear system, (b) holds as well.

13

Time-Invariant Systems

Figure 2.8: (a) shows an input at time t while (b) shows the same input t

0

seconds

later. In a time-invariant system both outputs would be identical except that the one in

(b) would be delayed by t

0

.

Linear Time-Invariant Systems

Figure 2.9: This is a combination of the two cases above. Since the input to (b) is a

scaled, time-shifted version of the input in (a), so is the output.

14

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

Superposition in Linear Time-Invariant Systems

Figure 2.10: The principle of superposition applied to LTI systems

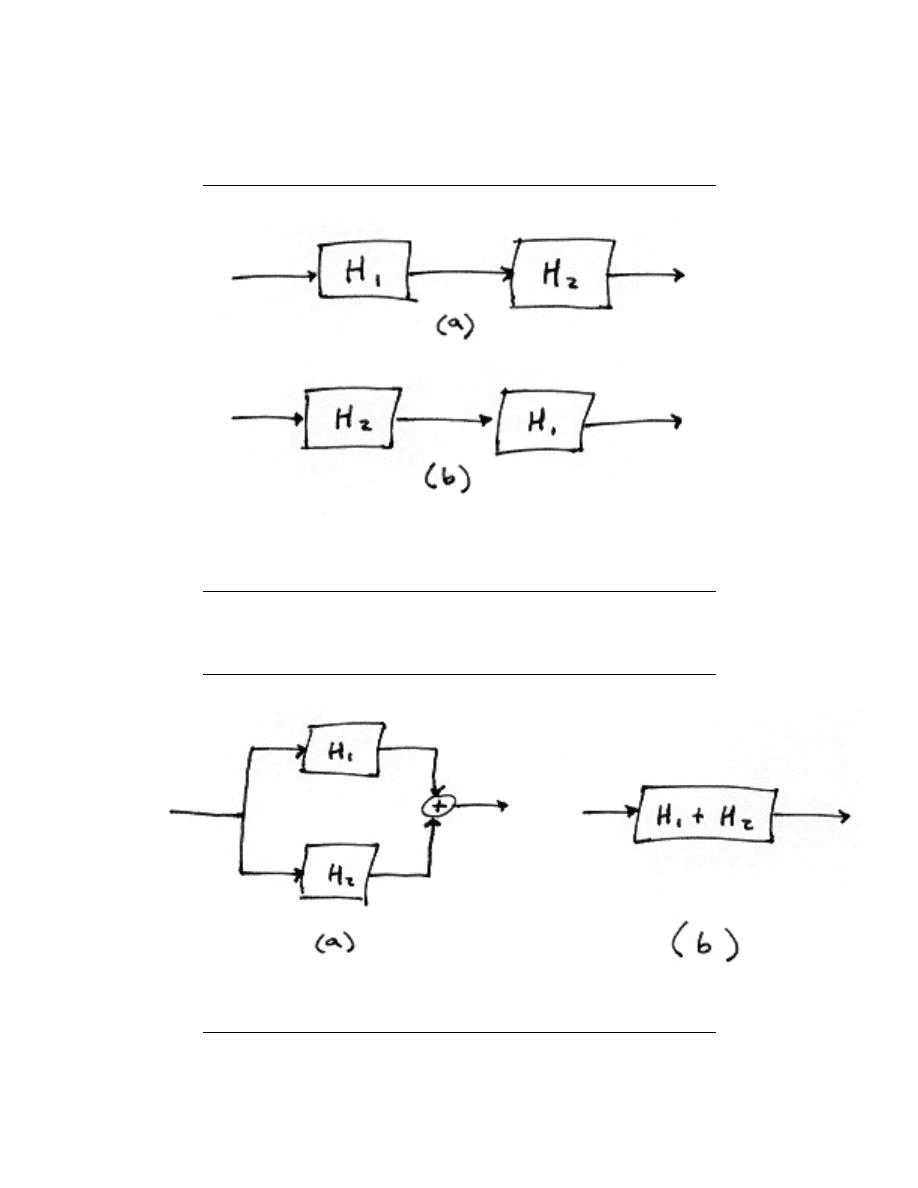

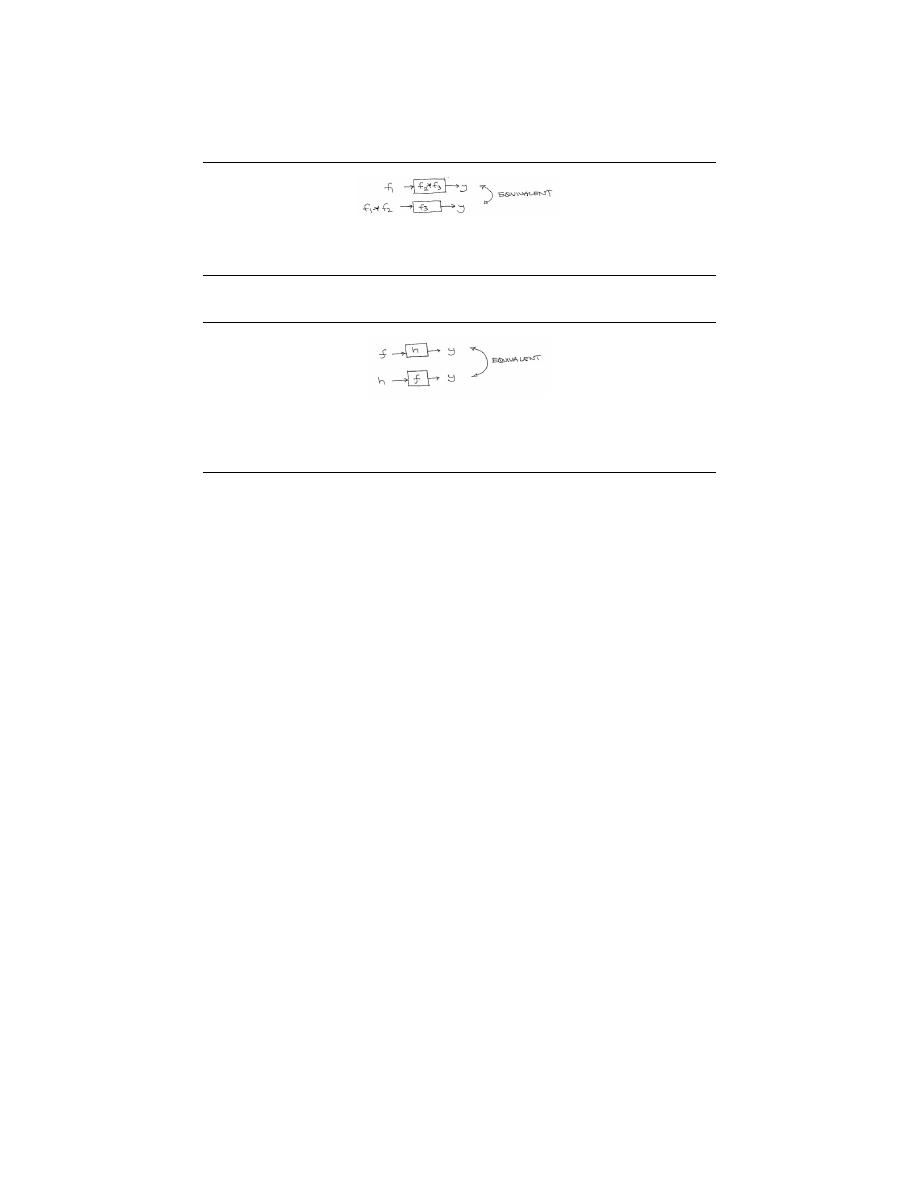

2.2.3.1 ”LTI Systems in Series”

If two or more LTI systems are in series with each other, their order can be interchanged

without affecting the overall output of the system. Systems in series are also called cascaded

systems.

2.2.3.2 ”LTI Systems in Parallel”

If two or more LTI systems are in parallel with one another, an equivalent system is one

that is defined as the sum of these individual systems.

2.2.4 ”Causality”

A system is causal if it does not depend on future values of the input to determine the

output. This means that if the first input to a system comes at time t

0

, then the system

should not give any output until that time. An example of a non-causal system would be

one that ”sensed” an input coming and gave an output before the input arrived:

A causal system is also characterized by an impulse response h(t) that is zero for t <0.

3.3 Signal Classifications and Properties

2.3.1 Introduction

This module will lay out some of the fundamentals of signal classification. This is basically

a list of definitions and properties that are fundamental to the discussion of signals and

systems. It should be noted that some discussions like energy signals vs. power signals have

been designated their own module for a more complete discussion, and will not be included

here.

15

Cascaded LTI Systems

Figure 2.11: The order of cascaded LTI systems can be interchanged without changing

the overall effect.

Parallel LTI Systems

Figure 2.12: Parallel systems can be condensed into the sum of systems.

16

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

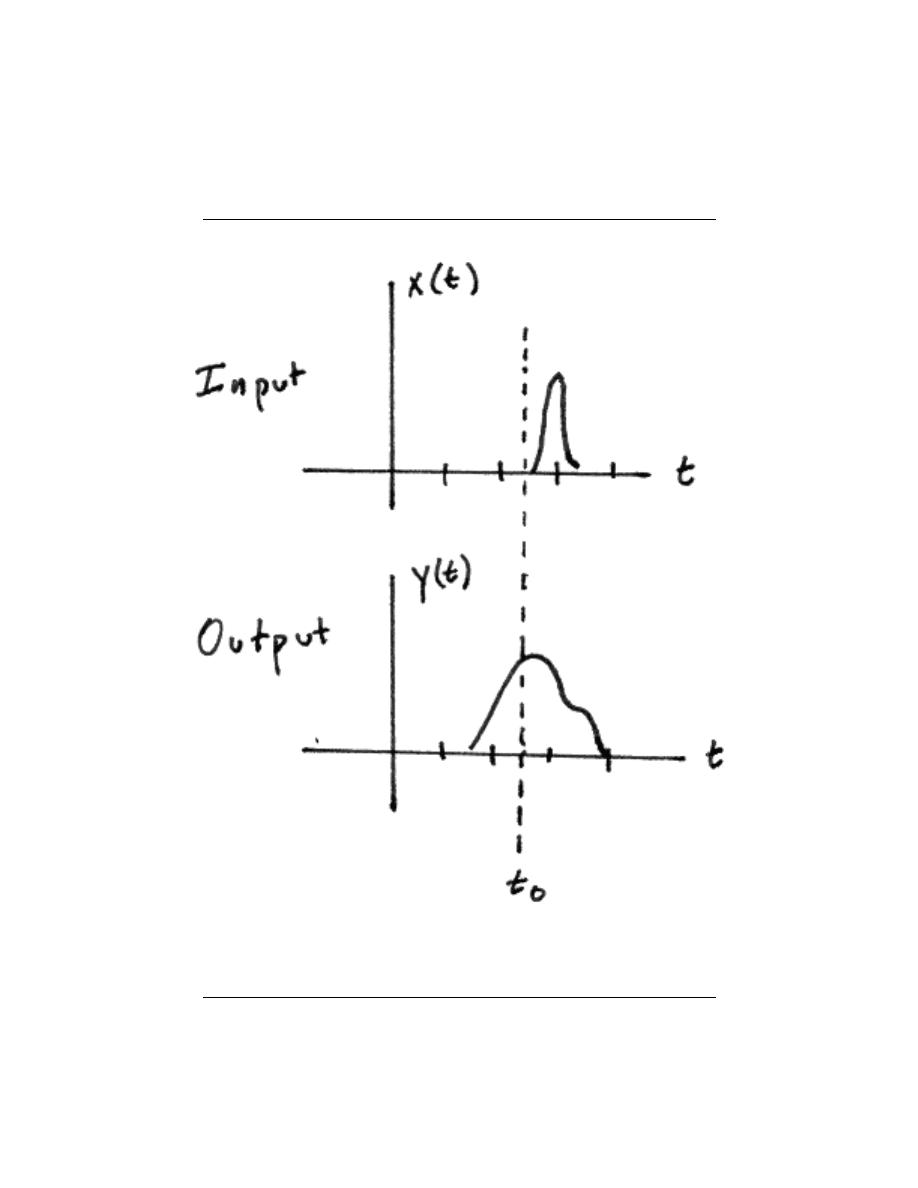

Non-causal System

Figure 2.13: In this non-causal system, an output is produced due to an input that

occurs later in time.

17

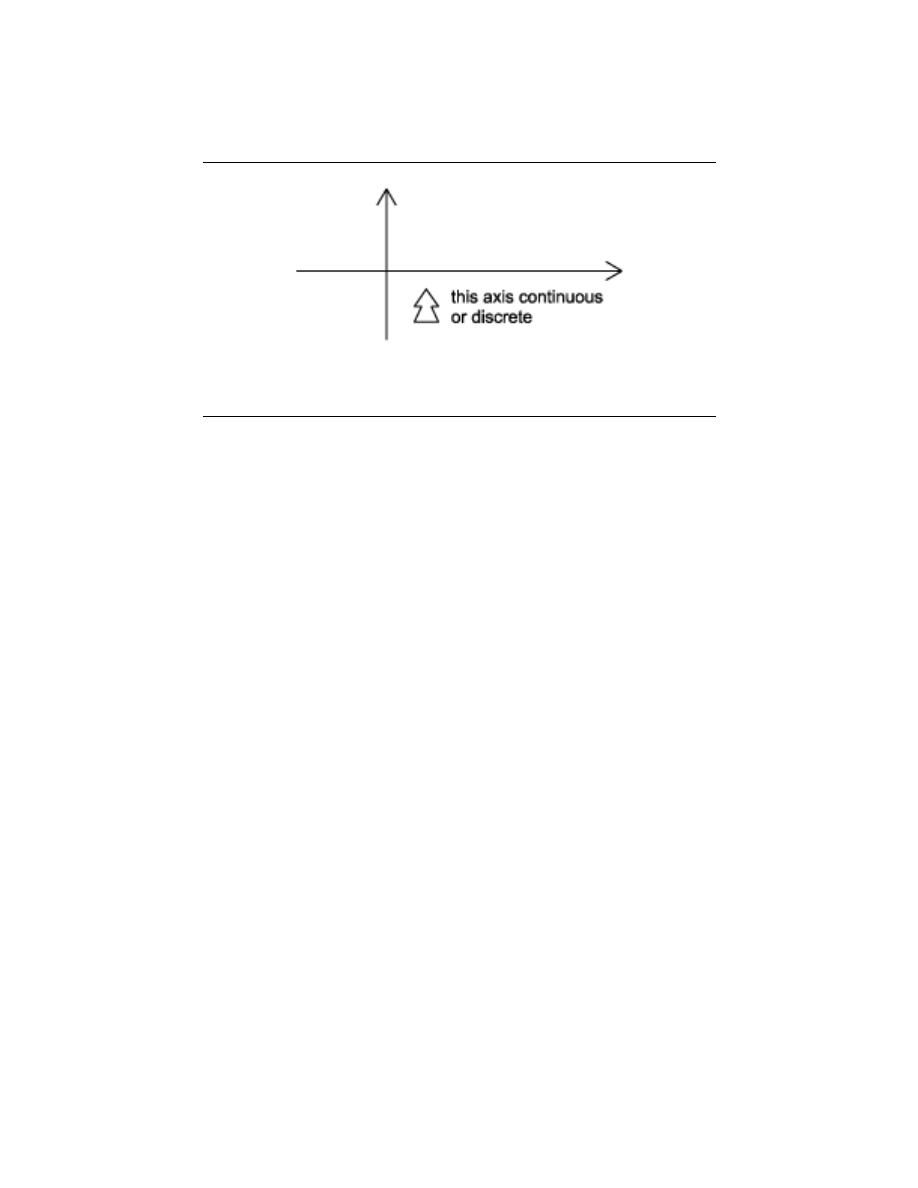

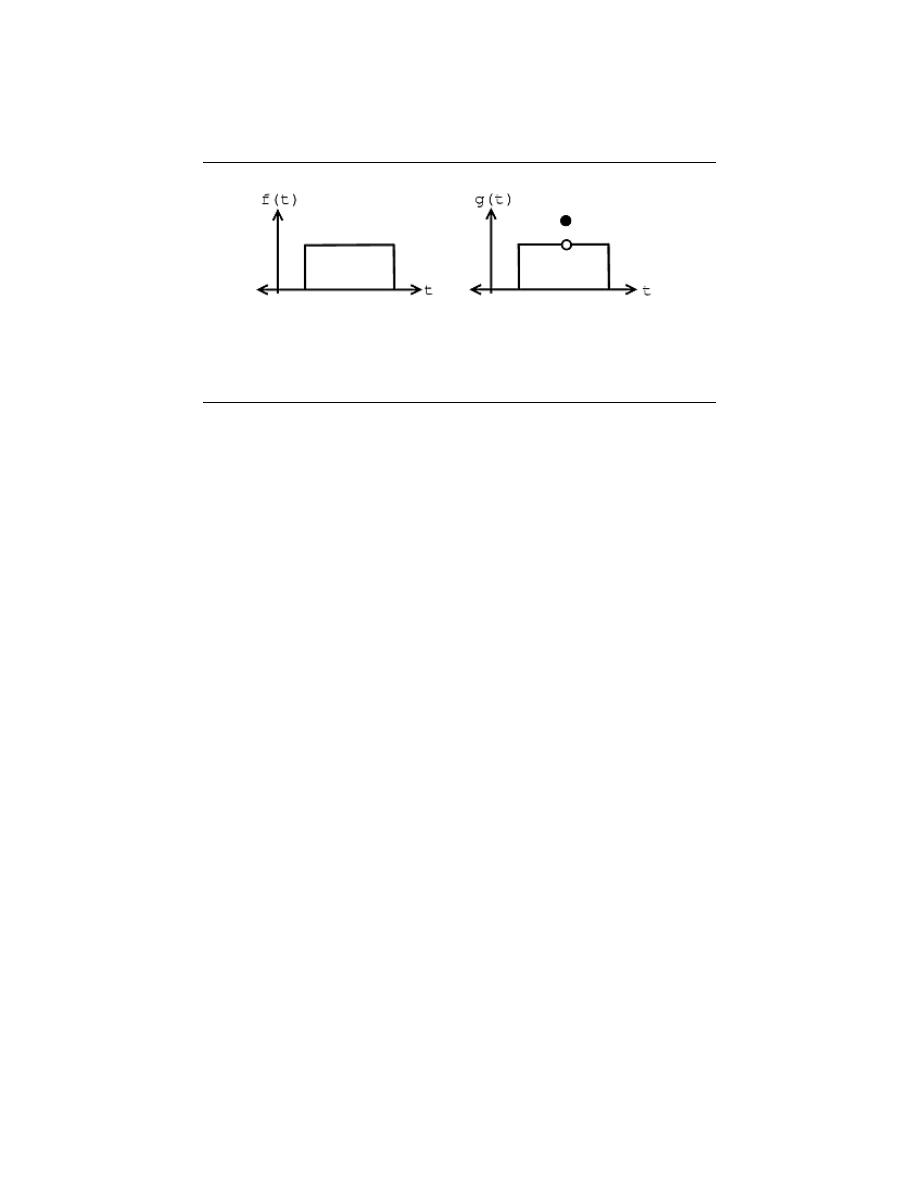

Figure 2.14

2.3.2 Classifications of Signals

Along with the classification of signals below, it is also important to understand the Clas-

sification of Systems.

2.3.2.1 Continuous-Time vs. Discrete-Time

As the names suggest, this classification is determined by whether or not the time axis

(x-axis) is discrete (countable) or continuous . A continuous-time signal will contain a

value for all real numbers along the time axis. In contrast to this, a discrete-time signal is

often created by using the sampling theorem to sample a continuous signal, so it will only

have values at equally spaced intervals along the time axis.

2.3.2.2 Analog vs. Digital

The difference between analog and digital is similar to the difference between continuous-

time and discrete-time. In this case, however, the difference is with respect to the value of

the function (y-axis). Analog corresponds to a continuous y-axis, while digital corresponds

to a discrete y-axis. An easy example of a digital signal is a binary sequence, where the

values of the function can only be one or zero.

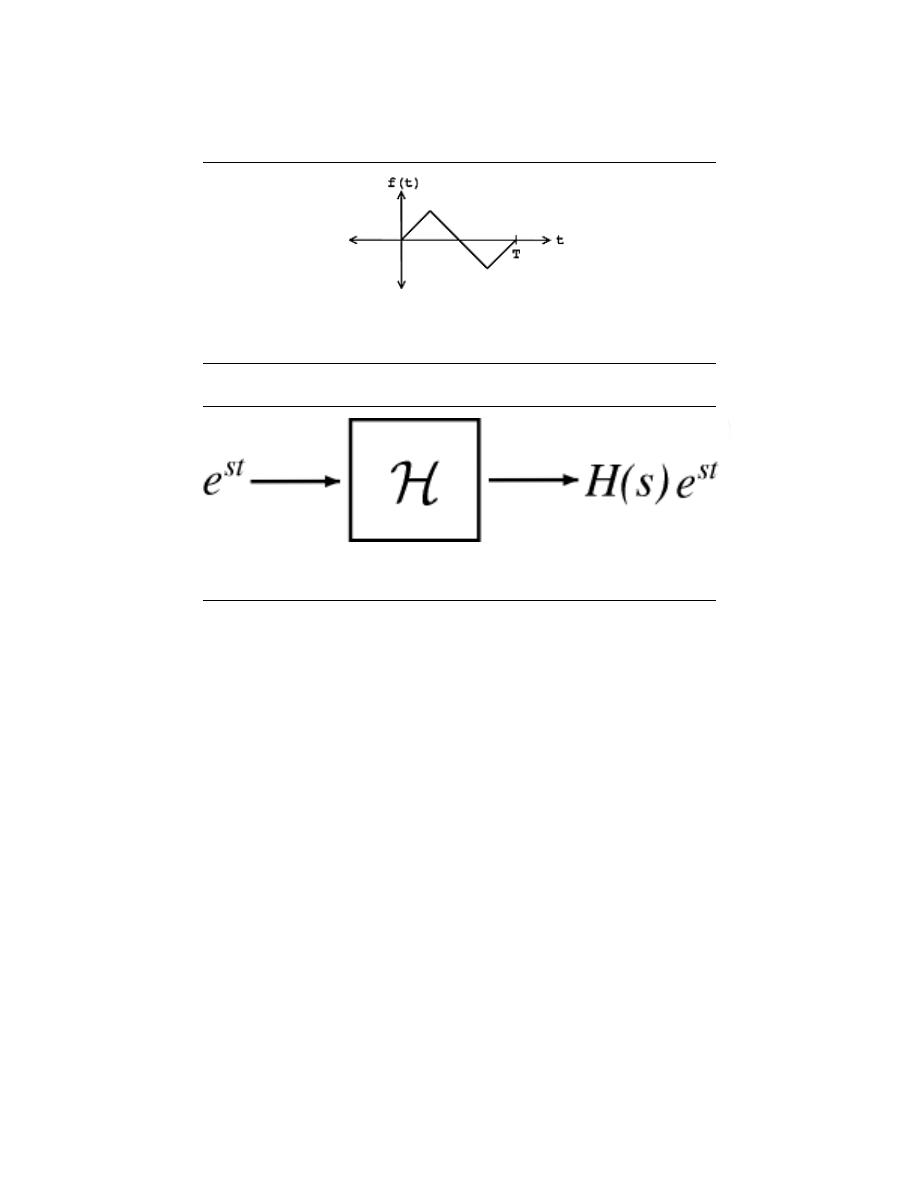

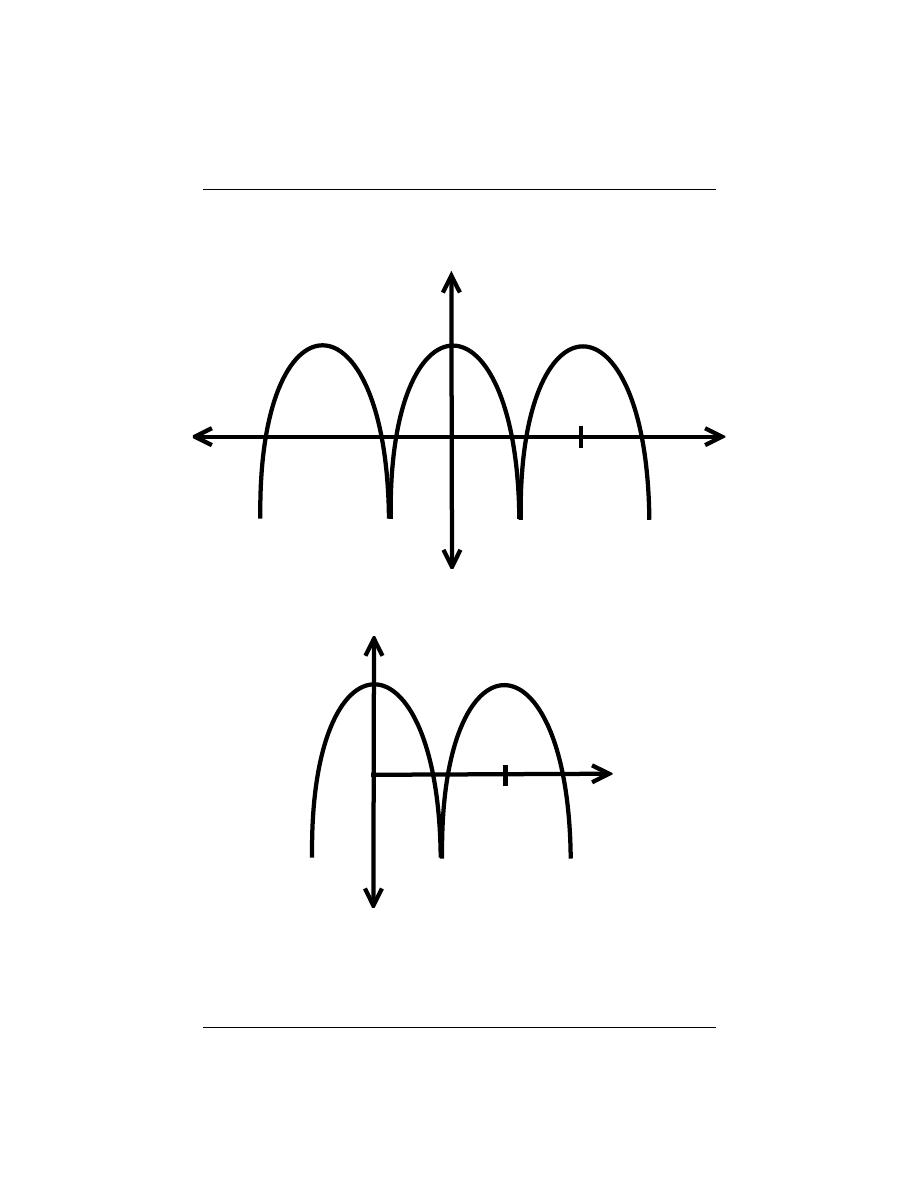

2.3.2.3 Periodic vs. Aperiodic

Periodic signals repeat with some period T, while aperiodic, or nonperiodic, signals do not.

We can define a periodic function through the following mathematical expression, where t

can be any number and T is a positive constant:

f (t) = f (T + t)

(2.7)

The fundamental period of our function, f (t), is the smallest value of T that the still

allows the above equation, Equation 2.7, to be true.

2.3.2.4 Causal vs. Anticausal vs. Noncausal

Causal signals are signals that are zero for all negative time, while anitcausal are signals

that are zero for all positive time. Noncausal signals are signals that have nonzero values

in both positive and negative time.

18

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

Figure 2.15

(a)

(b)

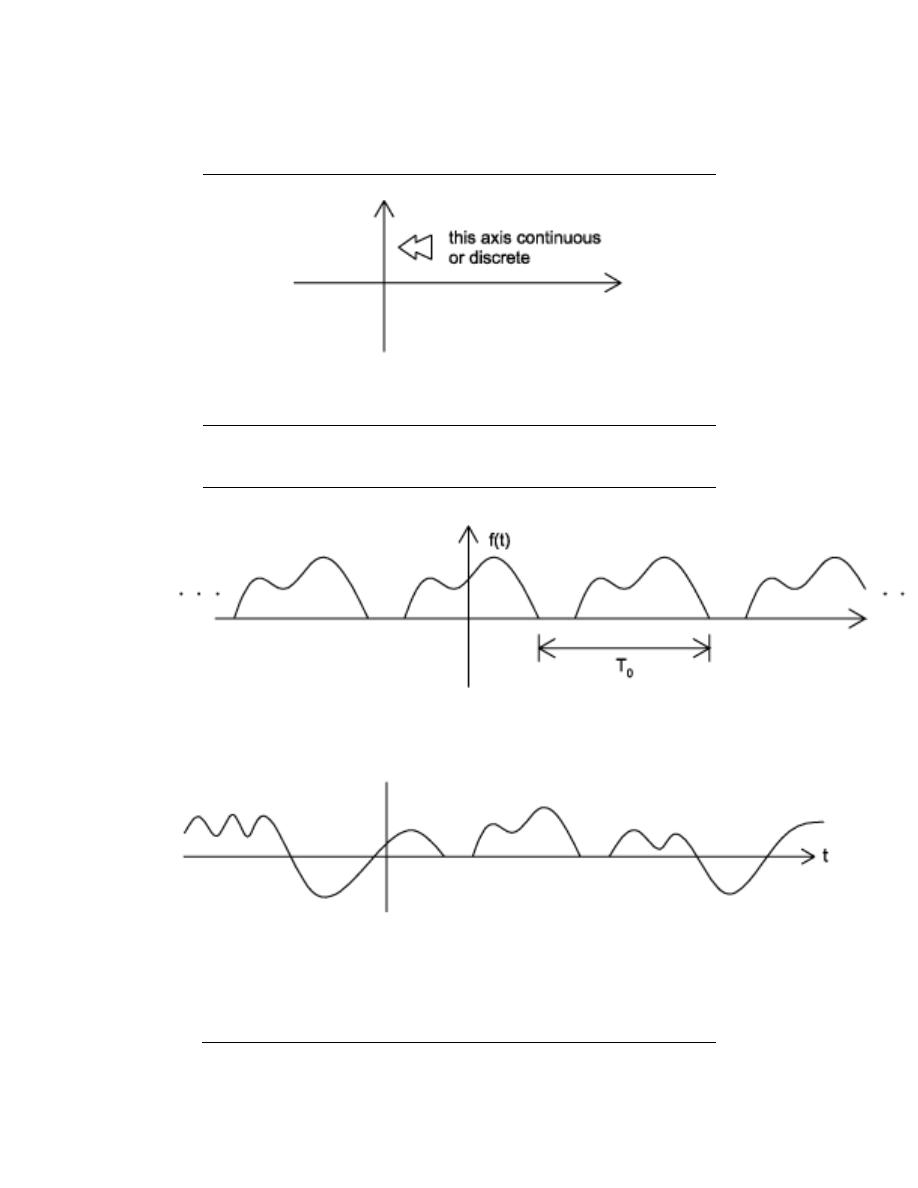

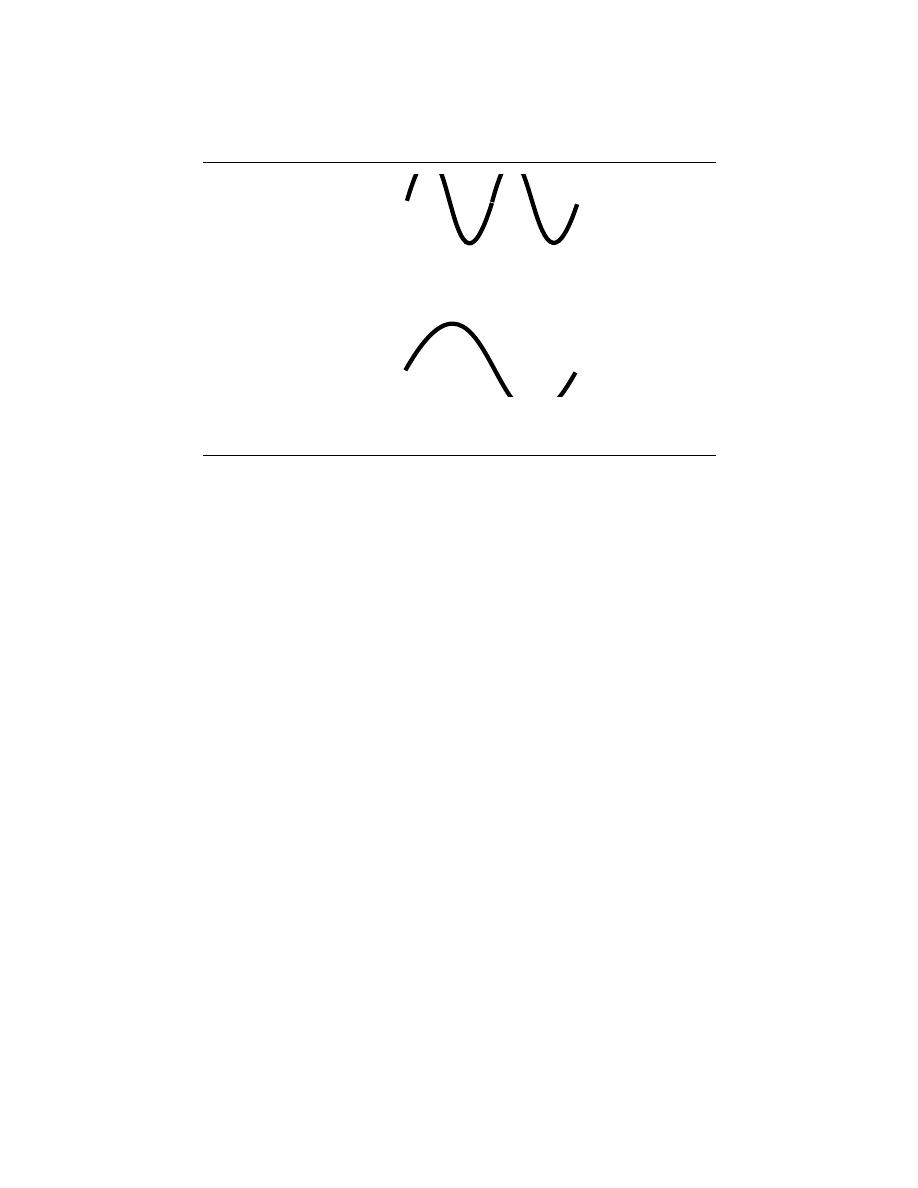

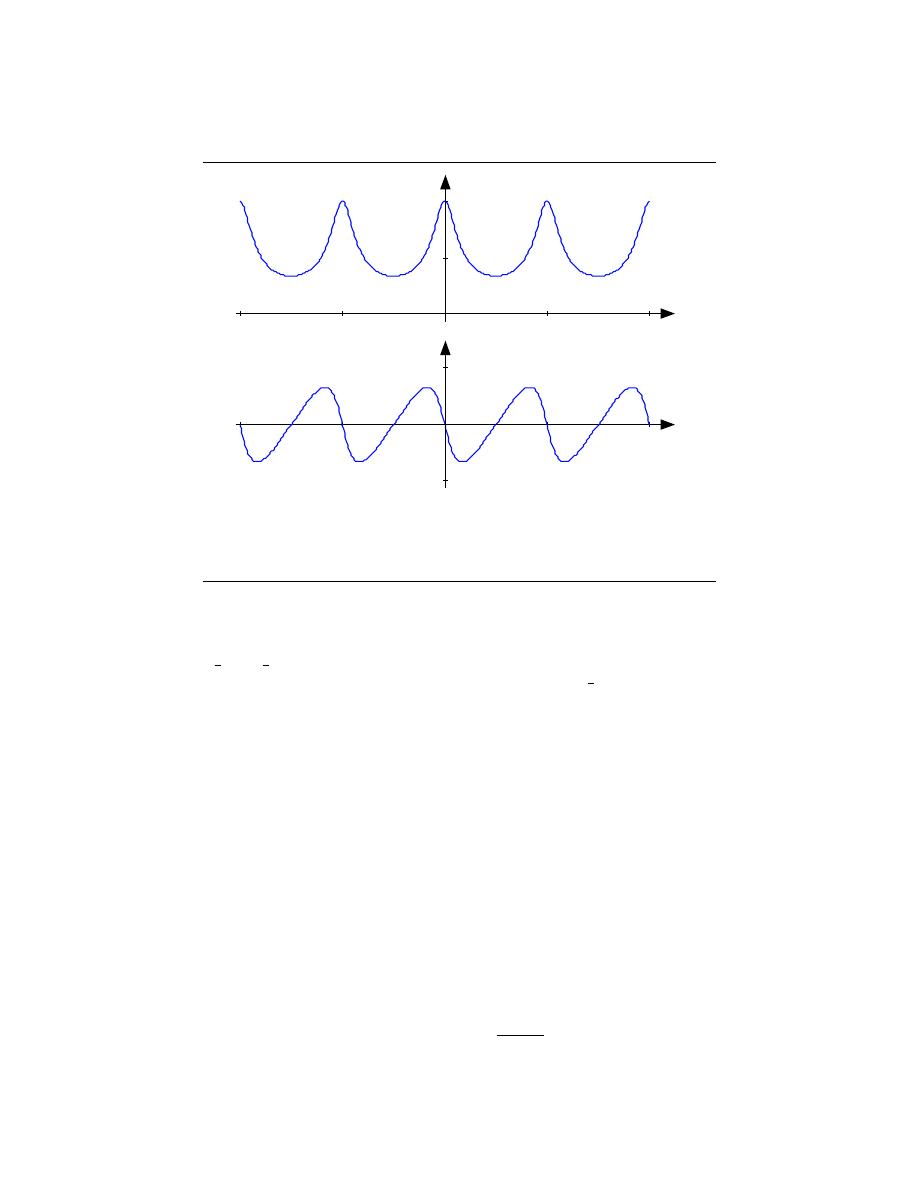

Figure 2.16:

(a) A periodic signal with period T

0

(b) An aperiodic signal

19

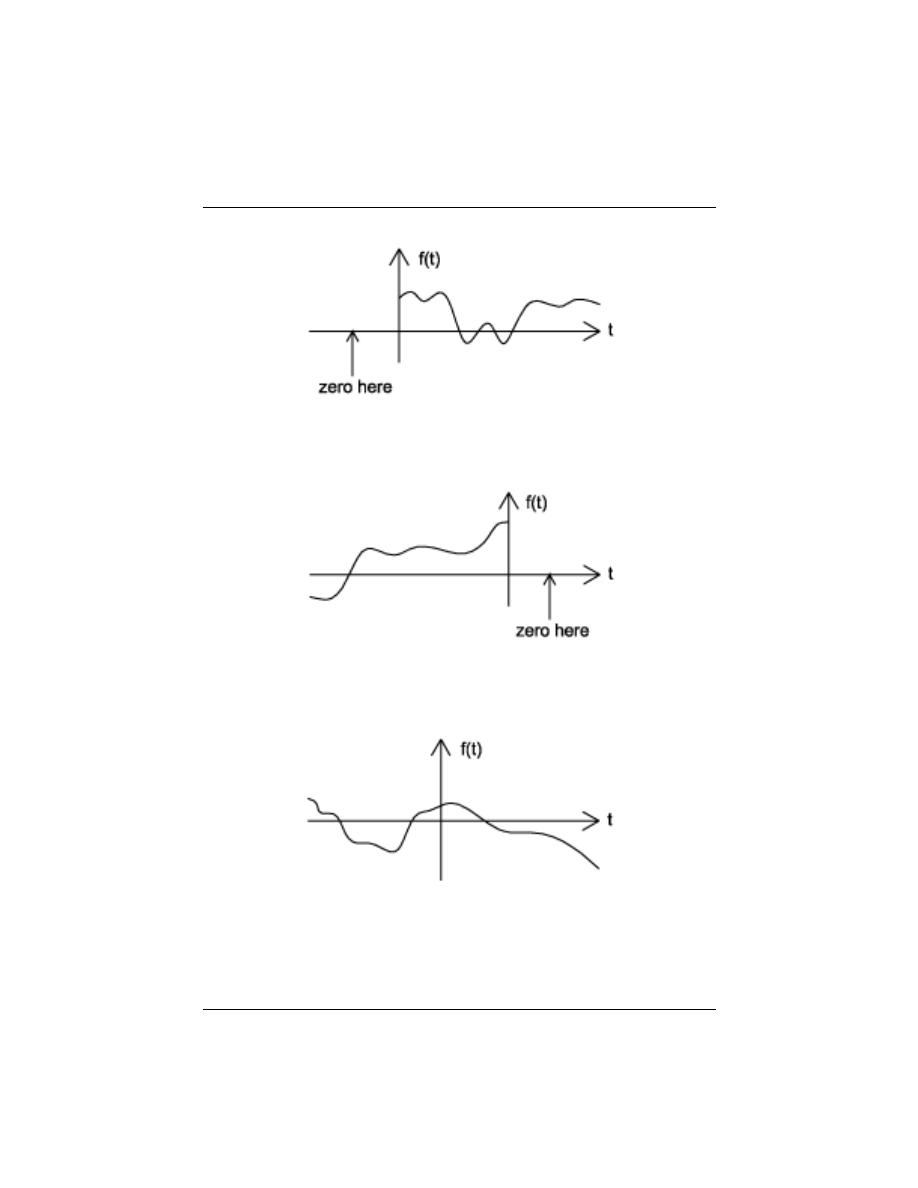

(a)

(b)

(c)

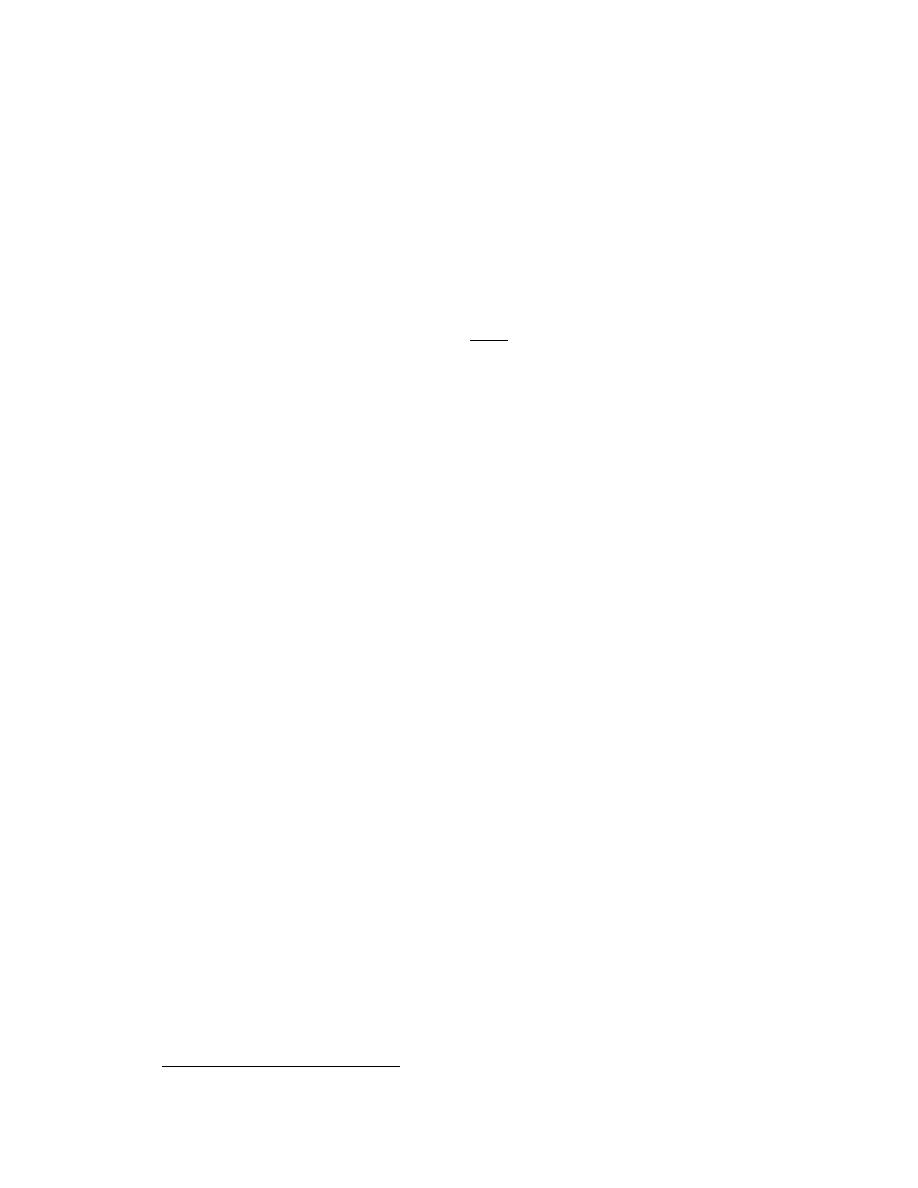

Figure 2.17:

(a) A causal signal (b) An anticausal signal (c) A noncausal signal

20

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

(a)

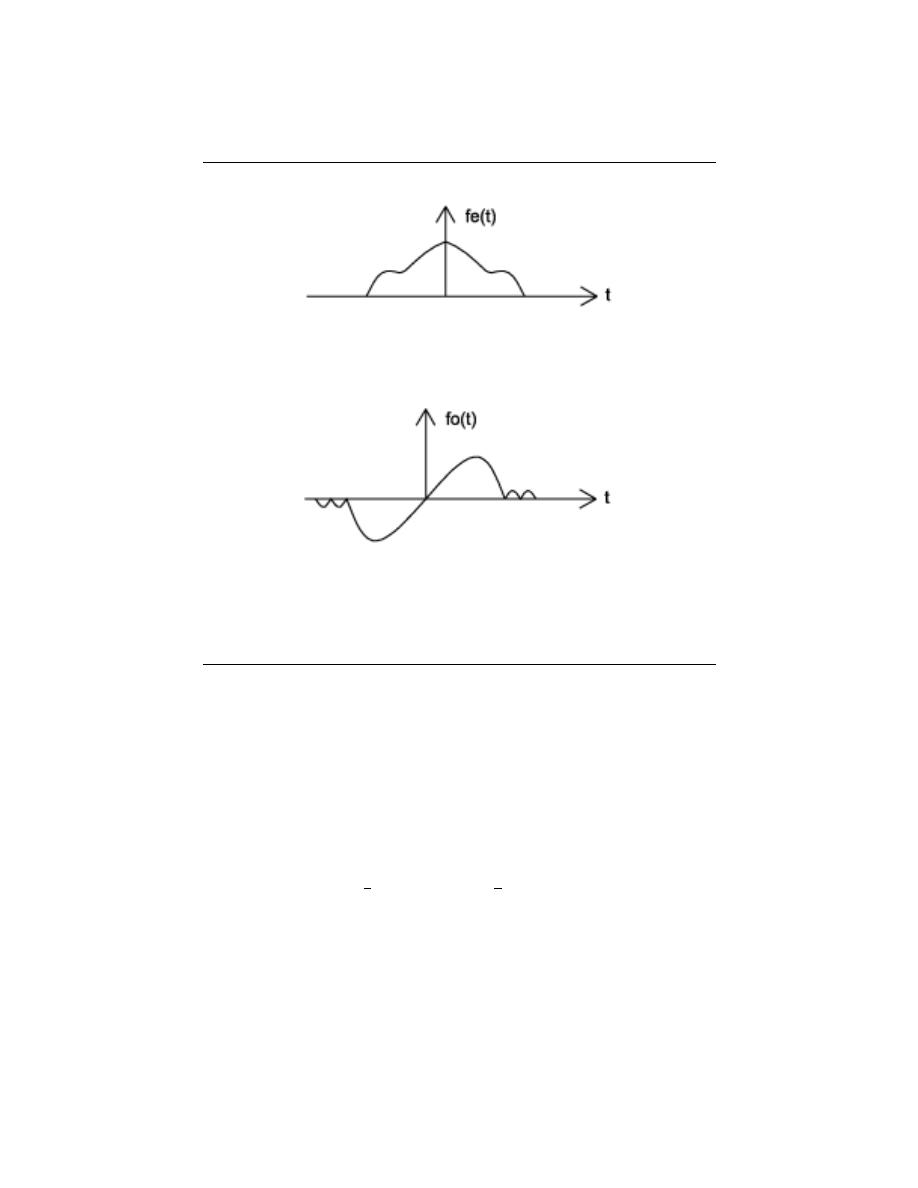

(b)

Figure 2.18:

(a) An even signal (b) An odd signal

2.3.2.5 Even vs. Odd

An even signal is any signal f such that f (t) = f (−t). Even signals can be easily spotted

as they are symmetric around the vertical axis. An odd signal , on the other hand, is a

signal f such that f (t) = − (f (−t)).

Using the definitions of even and odd signals, we can show that any signal can be

written as a combination of an even and odd signal. That is, every signal has an odd-even

decomposition. To demonstrate this, we have to look no further than a single equation.

f (t) =

1

2

(f (t) + f (−t)) +

1

2

(f (t) − f (−t))

(2.8)

By multiplying and adding this expression out, it can be shown to be true. Also, it can be

shown that f (t) + f (−t) fulfills the requirement of an even function, while f (t) − f (−t)

fulfills the requirement of an odd function.

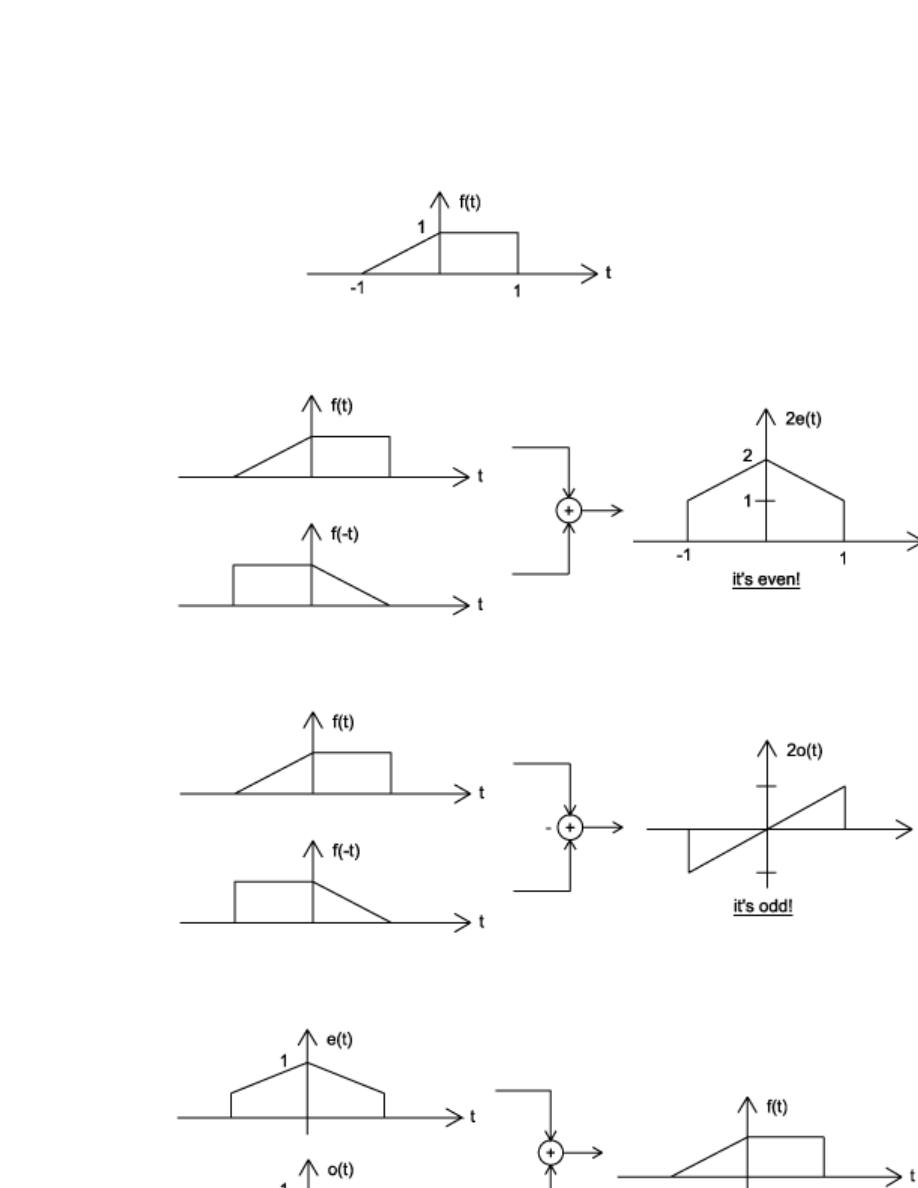

Example 2.1:

2.3.2.6 Deterministic vs. Random

A deterministic signal is a signal in which each value of the signal is fixed and can be

determined by a mathematical expression, rule, or table. Because of this the future values

21

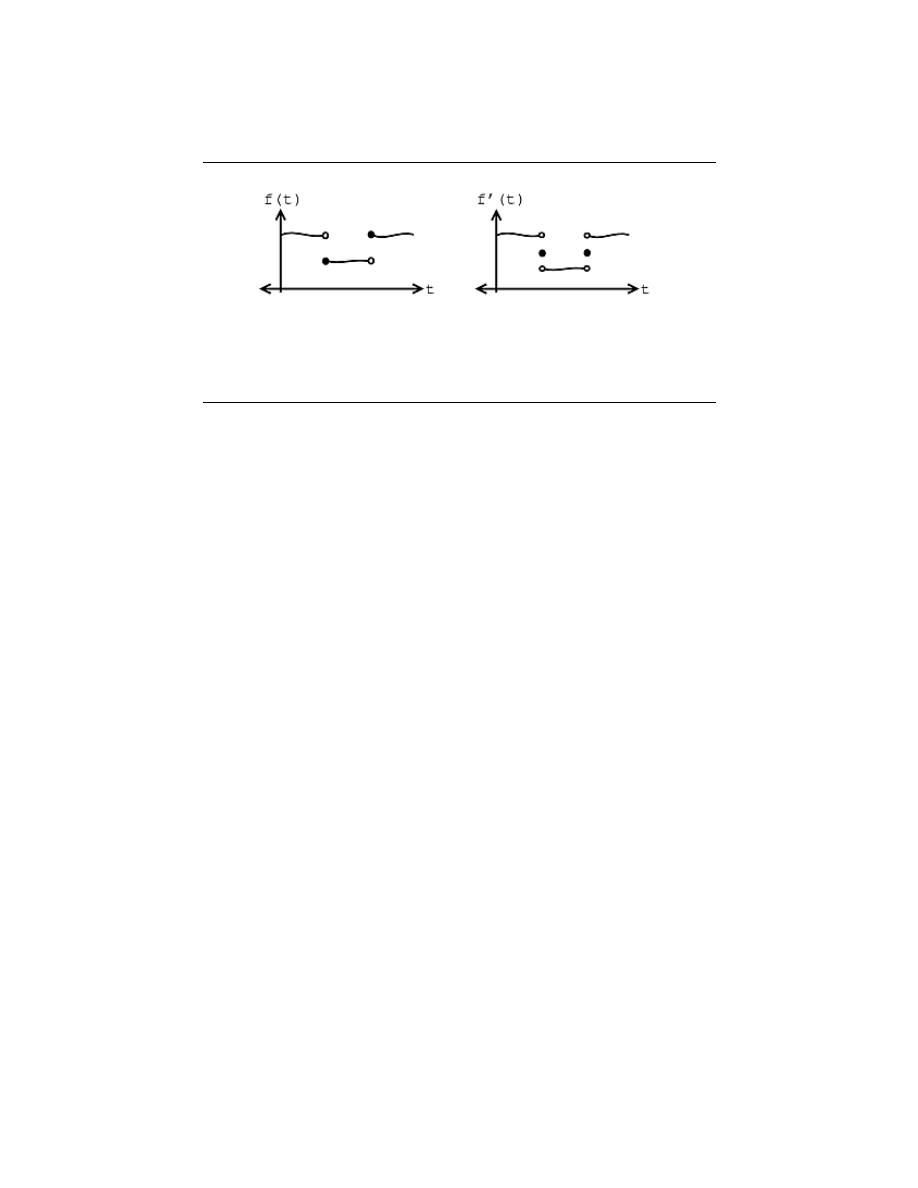

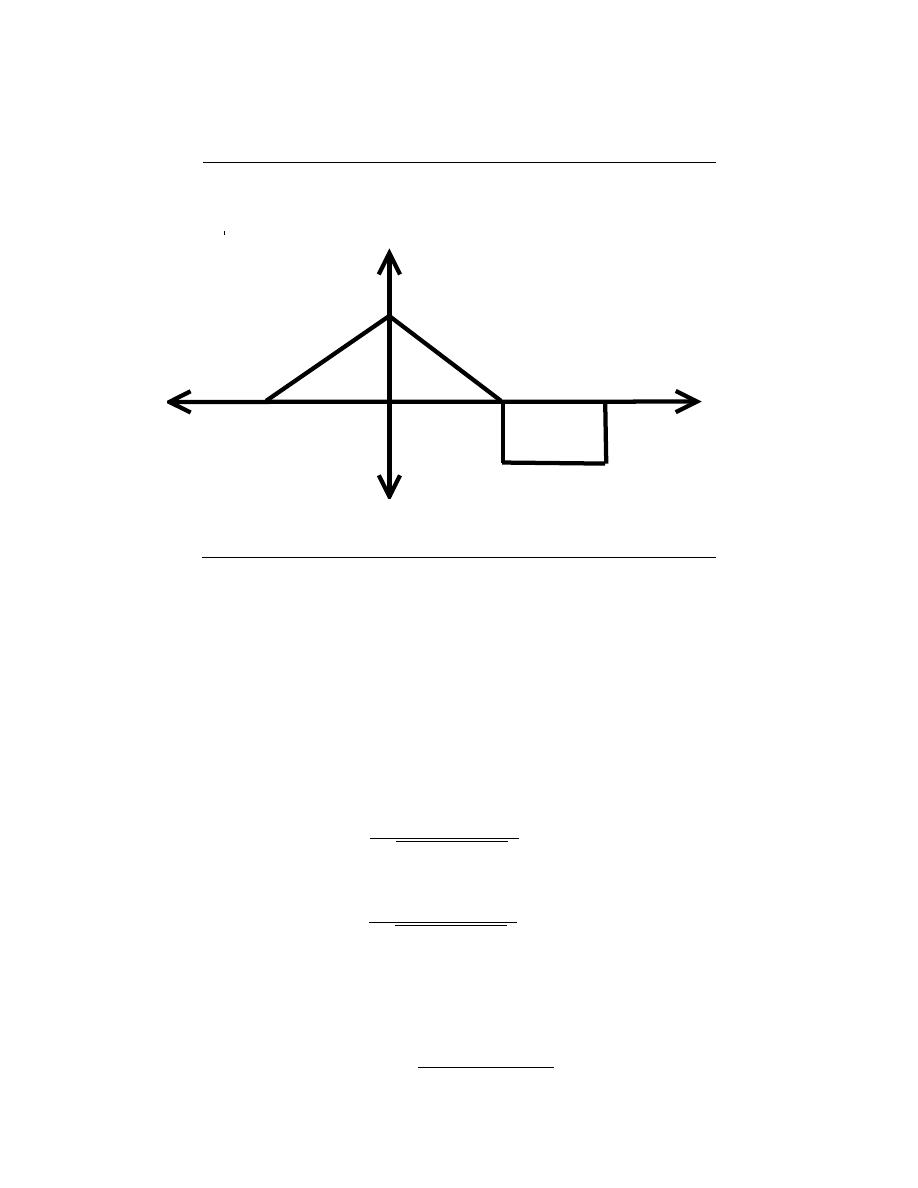

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

Figure 2.19:

(a) The signal we will decompose using odd-even decomposition (b)

Even part: e (t) =

1

2

(f (t) + f (−t)) (c) Odd part: o (t) =

1

2

(f (t) − f (−t)) (d) Check:

e (t) + o (t) = f (t)

22

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

(a)

(b)

Figure 2.20:

(a) Deterministic Signal (b) Random Signal

of the signal can be calculated from past values with complete confidence. On the other

hand, a random signal has a lot of uncertainty about its behavior. The future values of a

random signal cannot be acurately predicted and can usually only be guessed based on the

averages of sets of signals.

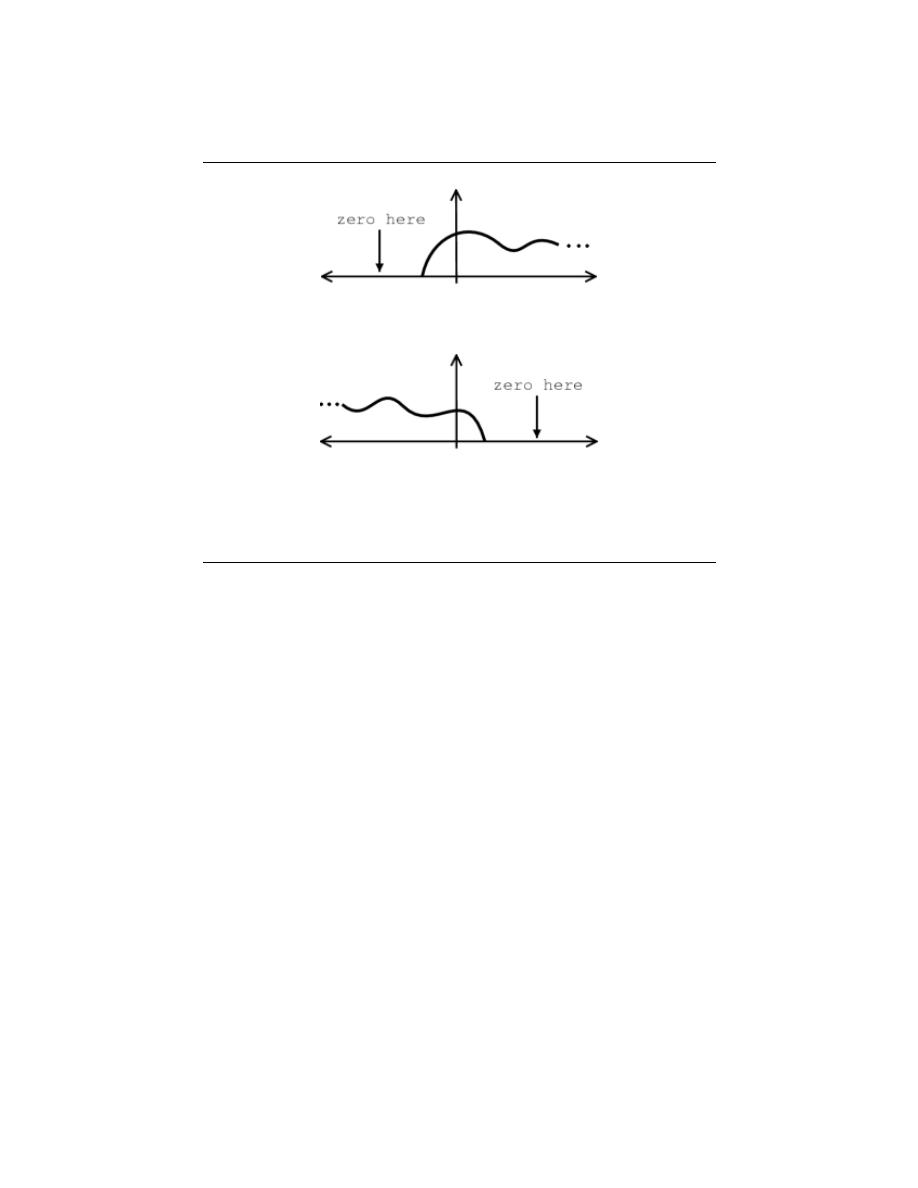

2.3.2.7 Right-Handed vs. Left-Handed

A right-handed signal and left-handed signal are those signals whose value is zero between

a given variable and positive or negative infinity. Mathematically speaking, a right-handed

signal is defined as any signal where f (t) = 0 for t < t

1

< ∞, and a left-handed signal

is defined as any signal where f (t) = 0 for t > t

1

> −∞. See the figures below for an

example. Both figures ”begin” at t

1

and then extends to positive or negative infinity with

mainly nonzero values.

2.3.2.8 Finite vs. Infinite Length

As the name applies, signals can be characterized as to whether they have a finite or infinite

length set of values. Most finite length signals are used when dealing with discrete-time

signals or a given sequence of values. Mathematically speaking, f (t) is a finite-length

signal if it is nonzero over a finite interval

t

1

< f (t) < t

2

where t

1

> −∞ and t

2

< ∞. An example can be seen in the below figure. Similarly, an

infinite-length signal , f (t), is defined as nonzero over all real numbers:

∞ ≤ f (t) ≤ −∞

23

(a)

(b)

Figure 2.21:

(a) Right-handed signal (b) Left-handed signal

3.4 Discrete-Time Signals

So far, we have treated what are known as analog signals and systems. Mathematically,

analog signals are functions having countinuous quantities as their independent variables,

such as space and time. Discrete-time signals are functions defined on the integers; they

are sequences. One of the fundamental results of signal theory will detail conditions under

which an analog signal can be converted into a discrete-time one and retrieved without

error. This result is important because discrete-time signals can be manipulated by systems

instantiated as computer programs. Subsequent modules describe how virtually all analog

signal processing can be performed with software.

As important as such results are, discrete-time signals are more general, encompassing

signals derived from analog ones and

signals that aren’t. For example, the characters

forming a text file form a sequence, which is also a discrete-time signal. We must deal with

such symbolic valued (pg ??) signals and systems as well.

As with analog signals, we seek ways of decomposing real-valued discrete-time signals

into simpler components. With this approach leading to a better understanding of signal

structure, we can exploit that structure to represent information (create ways of repre-

senting information with signals) and to extract information (retrieve the information thus

represented). For symbolic-valued signals, the approach is different: We develop a common

representation of all symbolic-valued signals so that we can embody the information they

contain in a unified way. From an information representation perspective, the most impor-

tant issue becomes, for both real-valued and symbolic-valued signals, efficiency; What is the

most parsimonious and compact way to represent information so that it can be extracted

24

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

Figure 2.22: Finite-Length Signal. Note that it only has nonzero values on a set, finite

interval.

later.

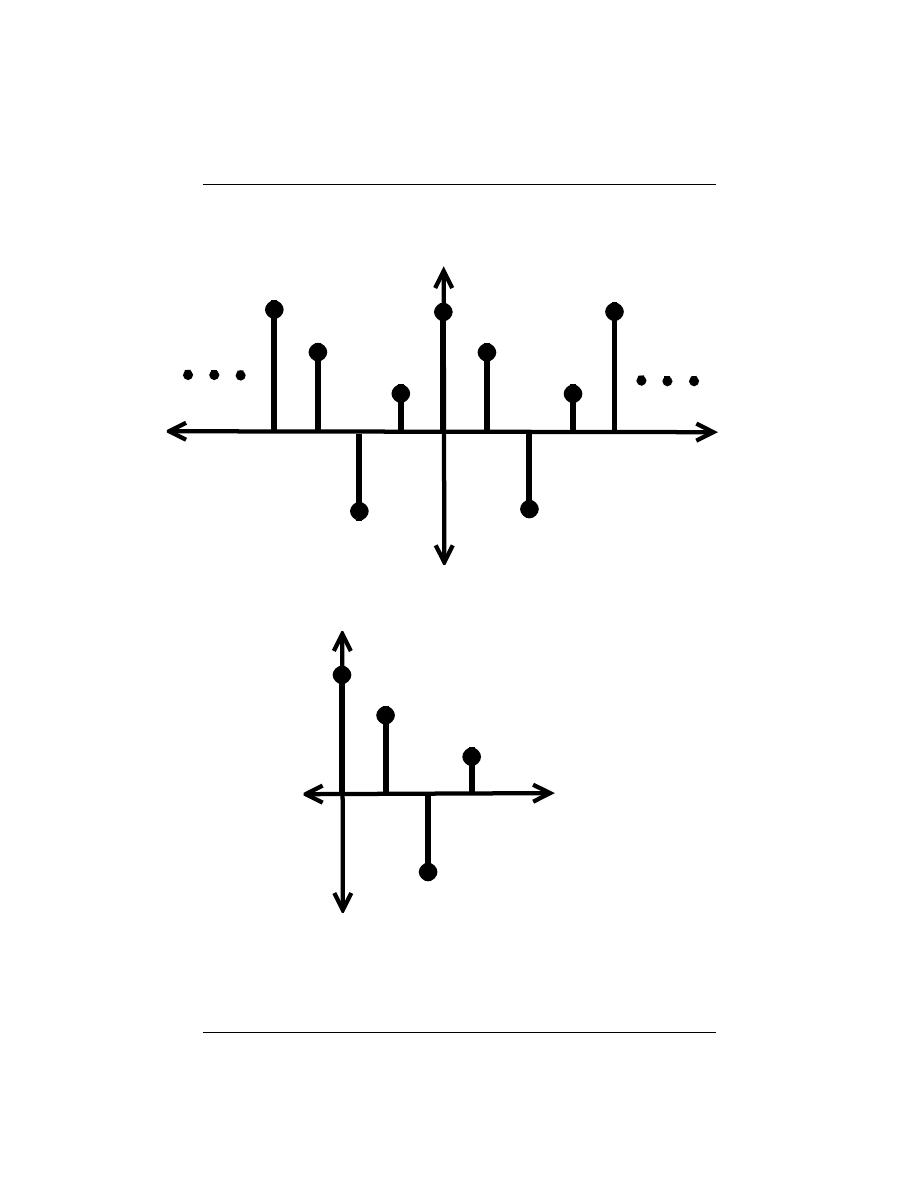

2.4.1 Real- and Complex-valued Signals

A discrete-time signal is represented symbolically as s (n), where n = {. . . , −1, 0, 1, . . . }.

We usually draw discrete-time signals as stem plots to emphasize the fact they are functions

defined only on the integers. We can delay a discrete-time signal by an integer just as with

analog ones. A delayed unit sample has the expression δ (n − m), and equals one when

n = m.

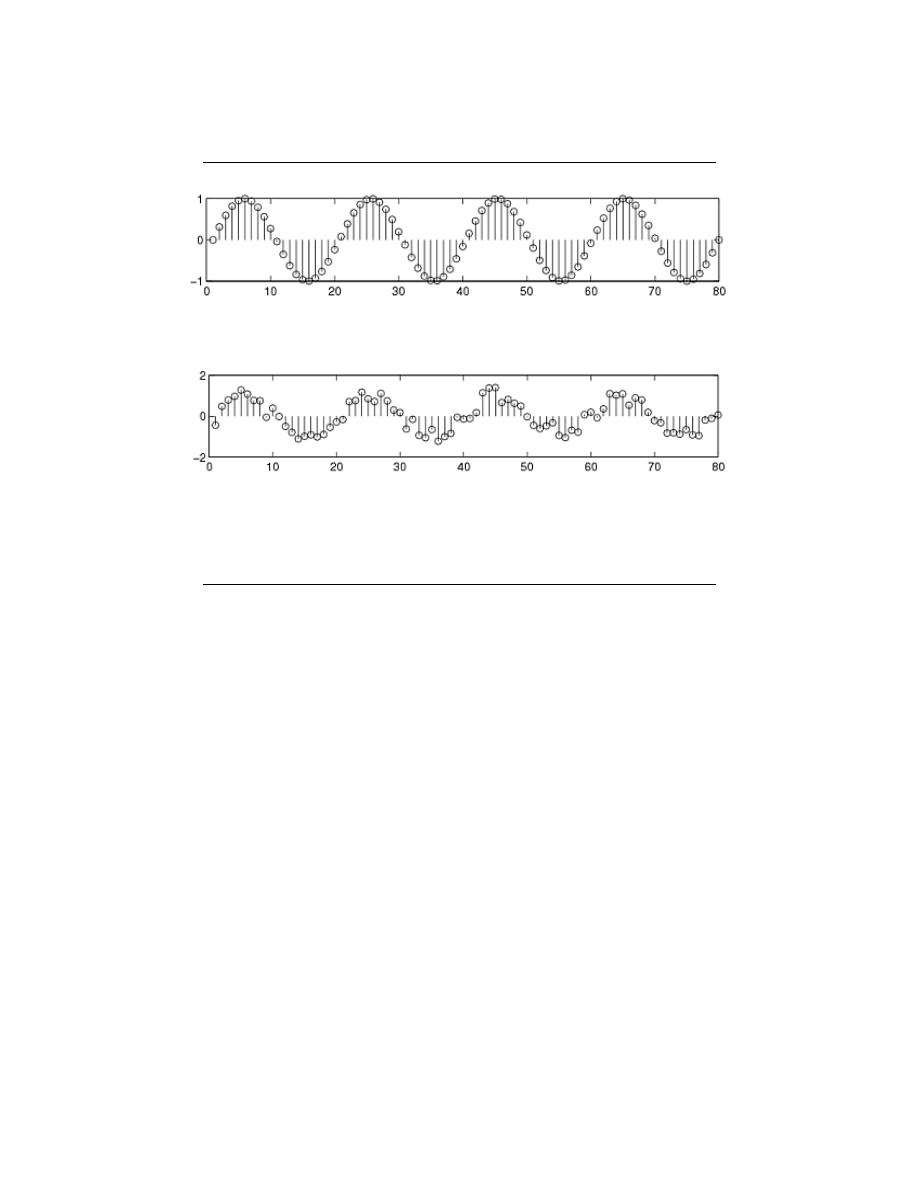

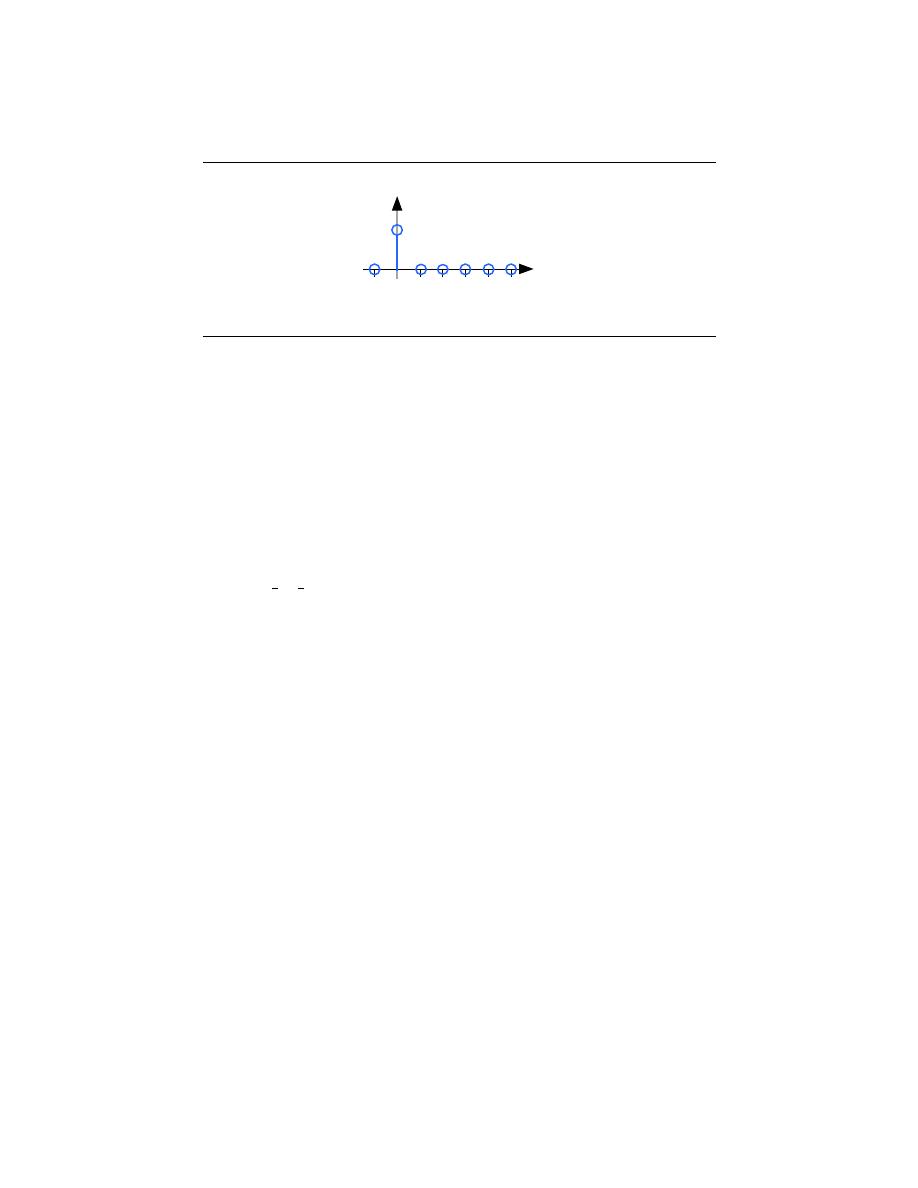

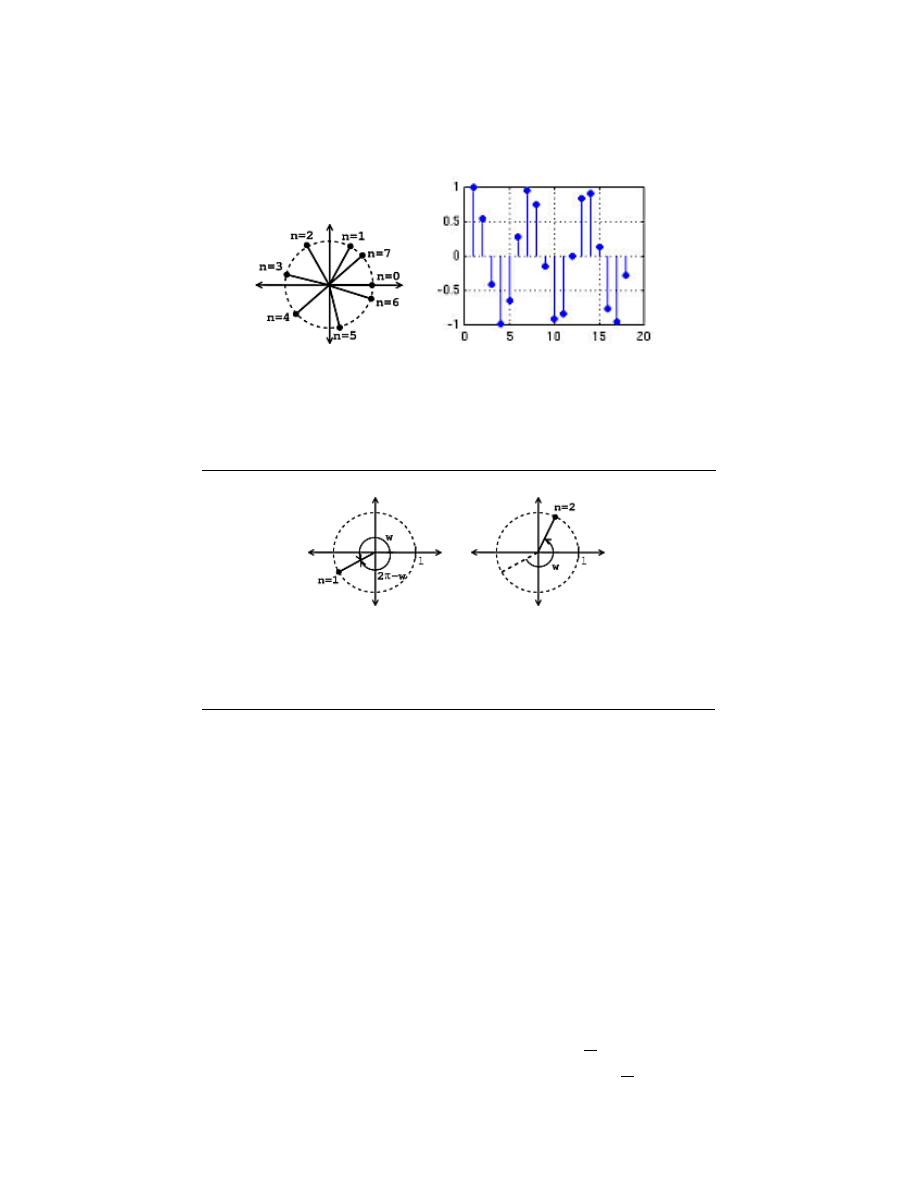

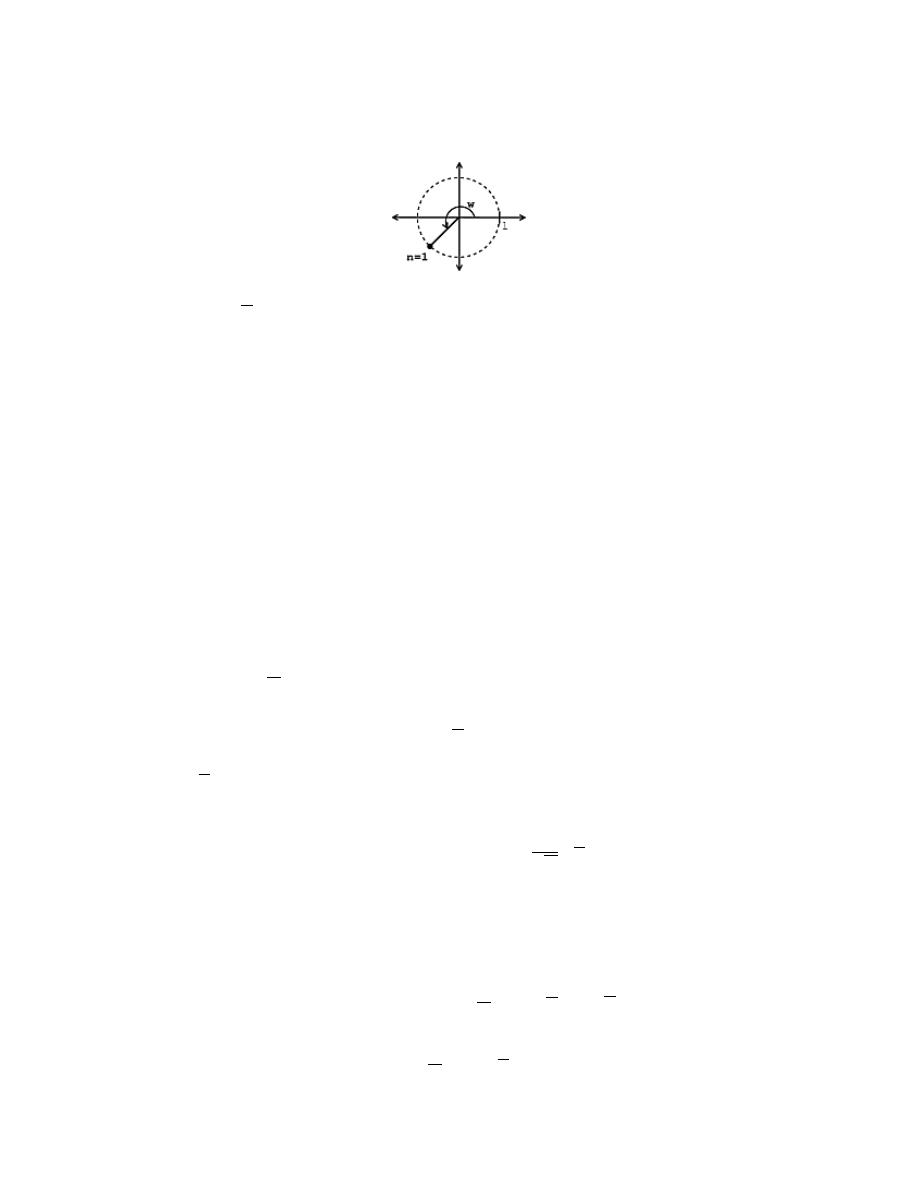

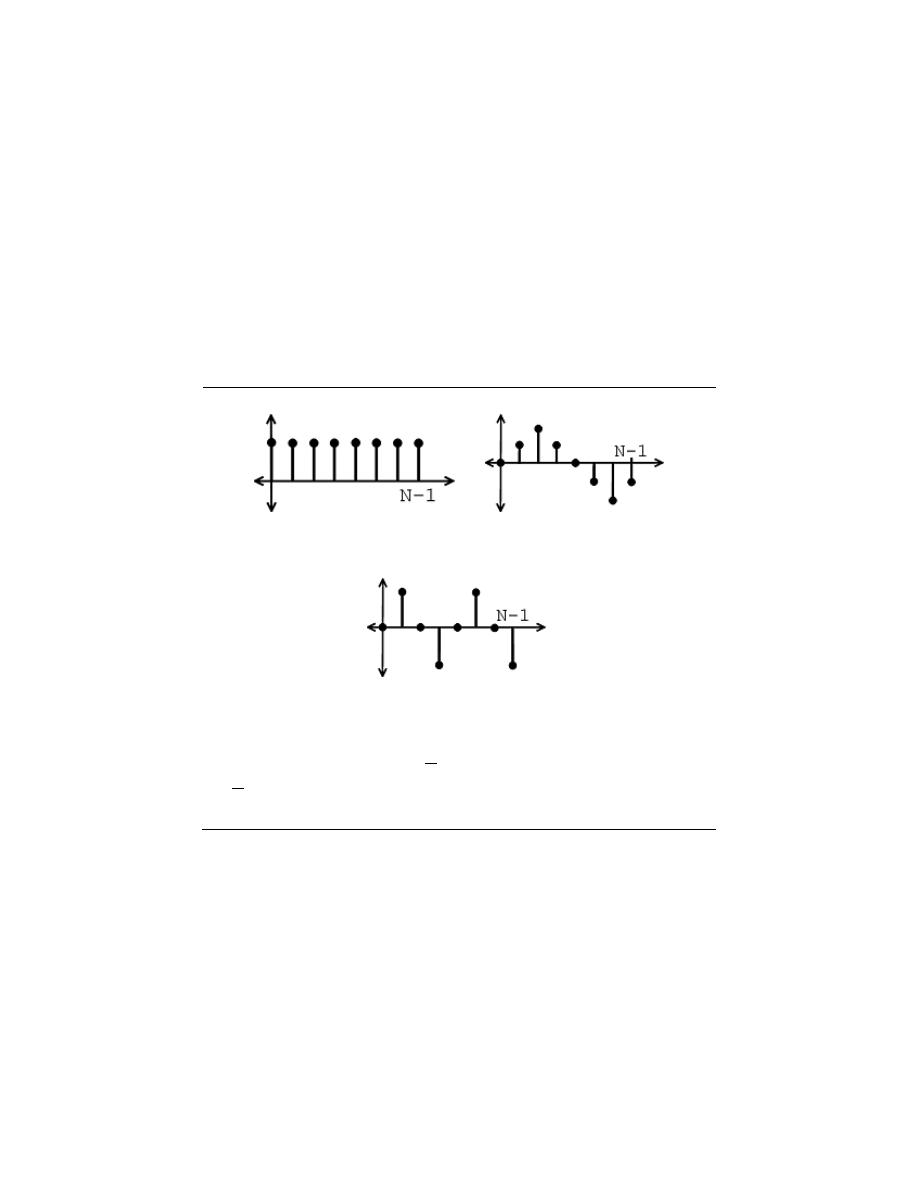

Discrete-Time Cosine Signal

n

sn

1

…

…

Figure 2.23:

The discrete-time cosine signal is plotted as a stem plot. Can you find

the formula for this signal?

25

Unit Sample

1

n

δ

n

Figure 2.24: The unit sample.

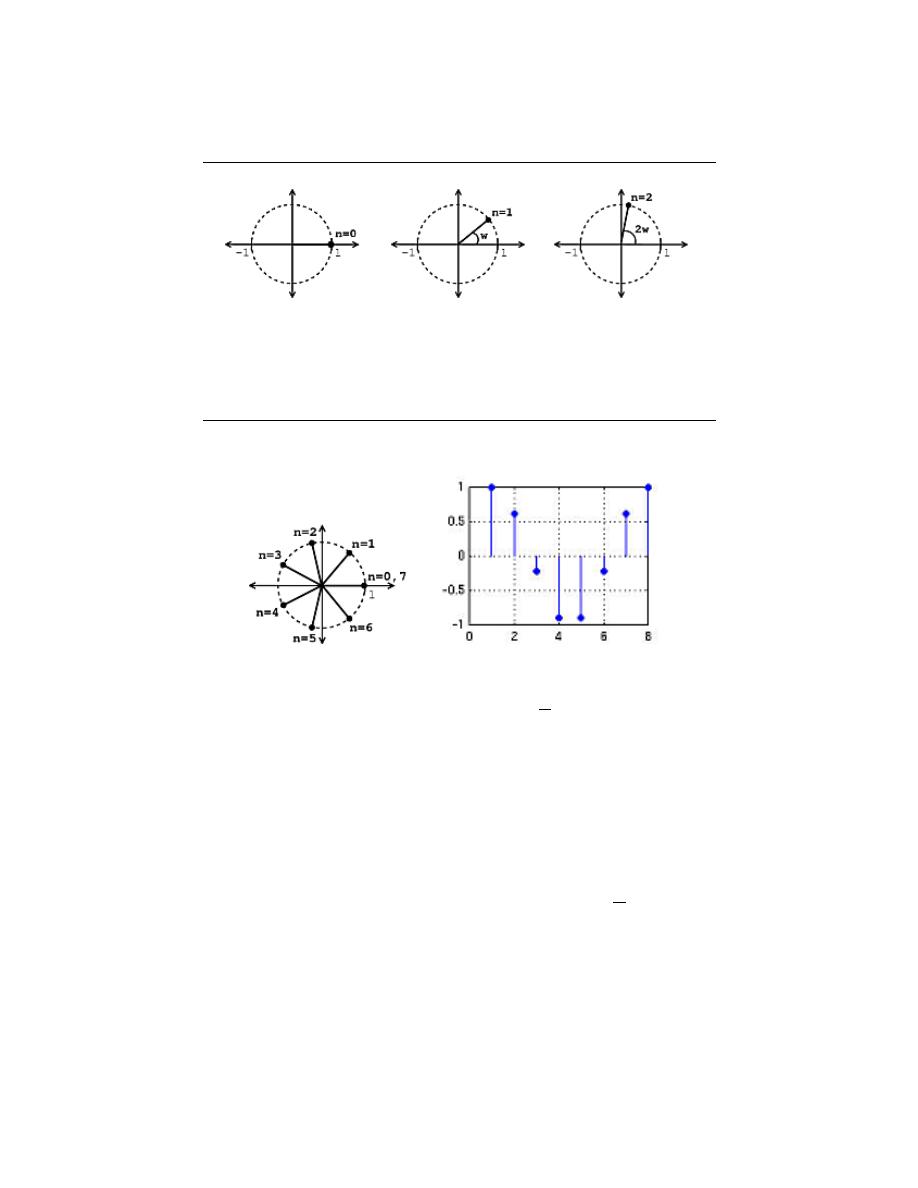

2.4.2 Complex Exponentials

The most important signal is, of course, the complex exponential sequence .

s (n) = e

j2πf n

(2.9)

2.4.3 Sinusoids

Discrete-time sinusoids have the obvious form s (n) = Acos (2πf n + φ). As opposed to

analog complex exponentials and sinusoids that can have their frequencies be any real value,

frequencies of their discrete-time counterparts yield unique waveforms only when f lies in

the interval −

1

2

,

1

2

. This property can be easily understood by noting that adding an

integer to the frequency of the discrete-time complex exponential has no effect on the signal’s

value.

e

j2π(f +m)n

=

e

j2πf n

e

j2πmn

=

e

j2πf n

(2.10)

This derivation follows because the complex exponential evaluated at an integer multiple of

2π equals one.

2.4.4 Unit Sample

The second-most important discrete-time signal is the unit sample , which is defined to

be

δ (n) =

1 if n = 0

0 otherwise

(2.11)

Examination of a discrete-time signal’s plot, like that of the cosine signal shown in this

figure (Figure 2.23), reveals that all signals consist of a sequence of delayed and scaled unit

samples. Because the value of a sequence at each integer m is denoted by s (m) and the

unit sample delayed to occur at m is written δ (n − m), we can decompose any signal as a

sum of unit samples delayed to the appropriate location and scaled by the signal value.

s (n) =

∞

X

m=−∞

(s (m) δ (n − m))

(2.12)

This kind of decomposition is unique to discrete-time signals, and will prove useful subse-

quently.

Discrete-time systems can act on discrete-time signals in ways similar to those found in

analog signals and systems. Because of the role of software in discrete-time systems, many

26

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

more different systems can be envisioned and “constructed” with programs than can be

with analog signals. In fact, a special class of analog signals can be converted into discrete-

time signals, processed with software, and converted back into an analog signal, all without

the incursion of error. For such signals, systems can be easily produced in software, with

equivalent analog realizations difficult, if not impossible, to design.

2.4.5 Symbolic-valued Signals

Another interesting aspect of discrete-time signals is that their values do not need to be

real numbers. We do have real-valued discrete-time signals like the sinusoid, but we also

have signals that denote the sequence of characters typed on the keyboard. Such characters

certainly aren’t real numbers, and as a collection of possible signal values, they have little

mathematical structure other than that they are members of a set. More formally, each

element of the symbolic-valued signal s (n) takes on one of the values {a

1

, . . . , a

K

} which

comprise the alphabet A. This technical terminology does not mean we restrict symbols

to being members of the English or Greek alphabet. They could represent keyboard char-

acters, bytes (8-bit quantities), integers that convey daily temperature. Whether controlled

by software or not, discrete-time systems are ultimately constructed from digital circuits,

which consist entirely of analog circuit elements. Furthermore, the transmission and recep-

tion of discrete-time signals, like e-mail, is accomplished with analog signals and systems.

Understanding how discrete-time and analog signals and systems intertwine is perhaps the

main goal of this course.

3.5 Useful Signals

Before looking at this module, hopefully you have some basic idea of what a signal is and

what basic classifications and properties a signal can have. To review, a signal is merely a

function defined with respect to an independent variable. This variable is often time but

could represent an index of a sequence or any number of things in any number of dimensions.

Most, if not all, signals that you will encounter in your studies and the real world will be

able to be created from the basic signals we discuss below. Because of this, these elementary

signals are often referred to as the building blocks for all other signals.

2.5.1 Sinusoids

Probably the most important elemental signal that you will deal with is the real-valued

sinusoid. In its continuous-time form, we write the general form as

x (t) = Acos (ωt + φ)

(2.13)

where A is the amplitude, ω is the frequency, and φ represents the phase. Note that it is

common to see ωt replaced with 2πf t. Since sinusoidal signals are periodic, we can express

the period of these, or any periodic signal, as

T =

2π

ω

(2.14)

2.5.2 Complex Exponential Function

Maybe as important as the general sinusoid, the complex exponential function will be-

come a critical part of your study of signals and systems. Its general form is written as

27

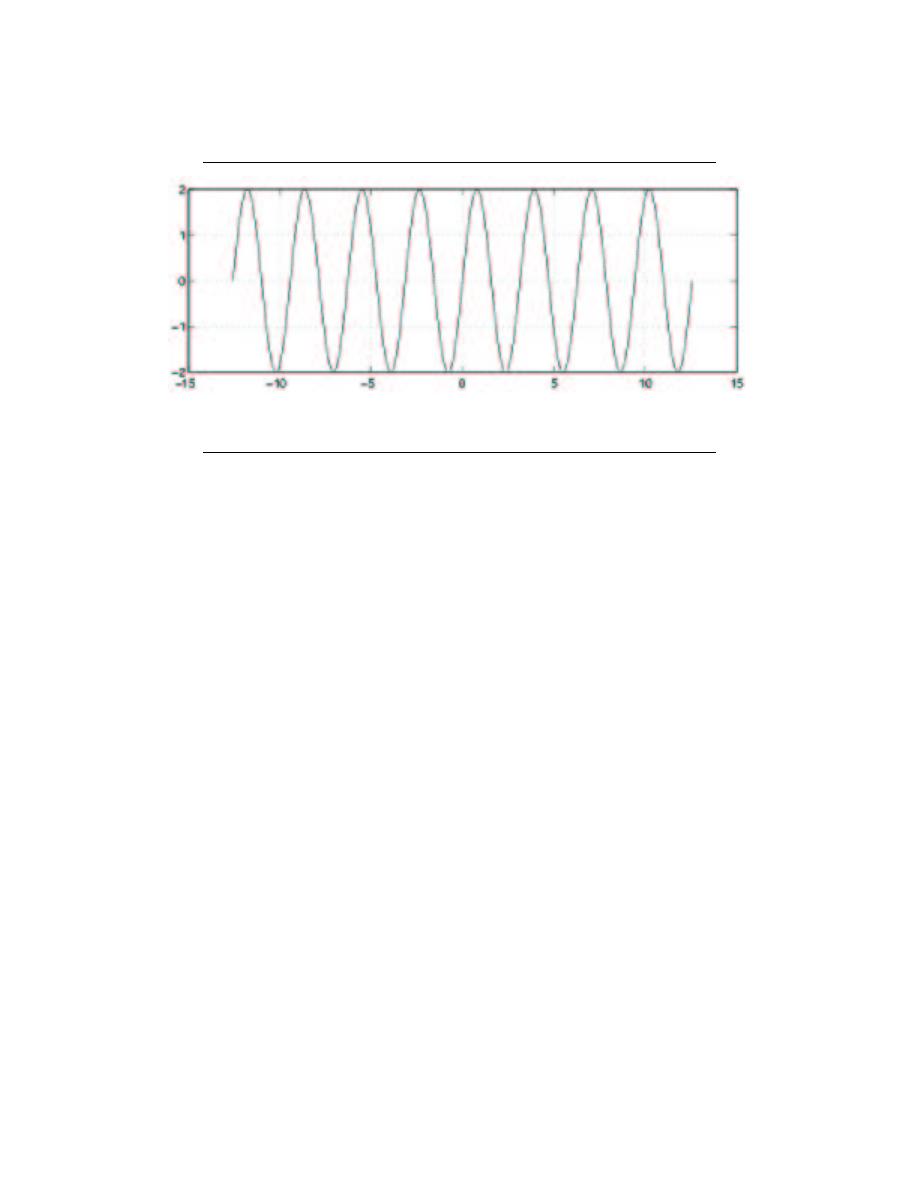

Figure 2.25:

Sinusoid with A = 2, w = 2, and φ = 0.

f (t) = Be

st

(2.15)

where s, shown below, is a complex number in terms of σ, the phase constant, and ω the

frequency:

s = σ + jω

Please look at the complex exponential module or the other elemental signals page (pg ??)

for a much more in depth look at this important signal.

2.5.3 Real Exponentials

Just as the name sounds, real exponentials contain no imaginary numbers and are expressed

simply as

f (t) = Be

αt

(2.16)

where both B and α are real parameters. Unlike the complex exponential that oscillates,

the real exponential either decays or grows depending on the value of α.

• - Decaying Exponential , when α < 0

• - Growing Exponential , when α > 0

2.5.4 Unit Impulse Function

The unit impulse ”function” (or Dirac delta function) is a signal that has infinite height

and infinitesimal width. However, because of the way it is defined, it actually integrates to

one. While in the engineering world, this signal is quite nice and aids in the understanding of

many concepts, some mathematicians have a problem with it being called a function, since

it is not defined at t = 0 . Engineers reconcile this problem by keeping it around integrals,

in order to keep it more nicely defined. The unit impulse is most commonly denoted as

δ (t)

28

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

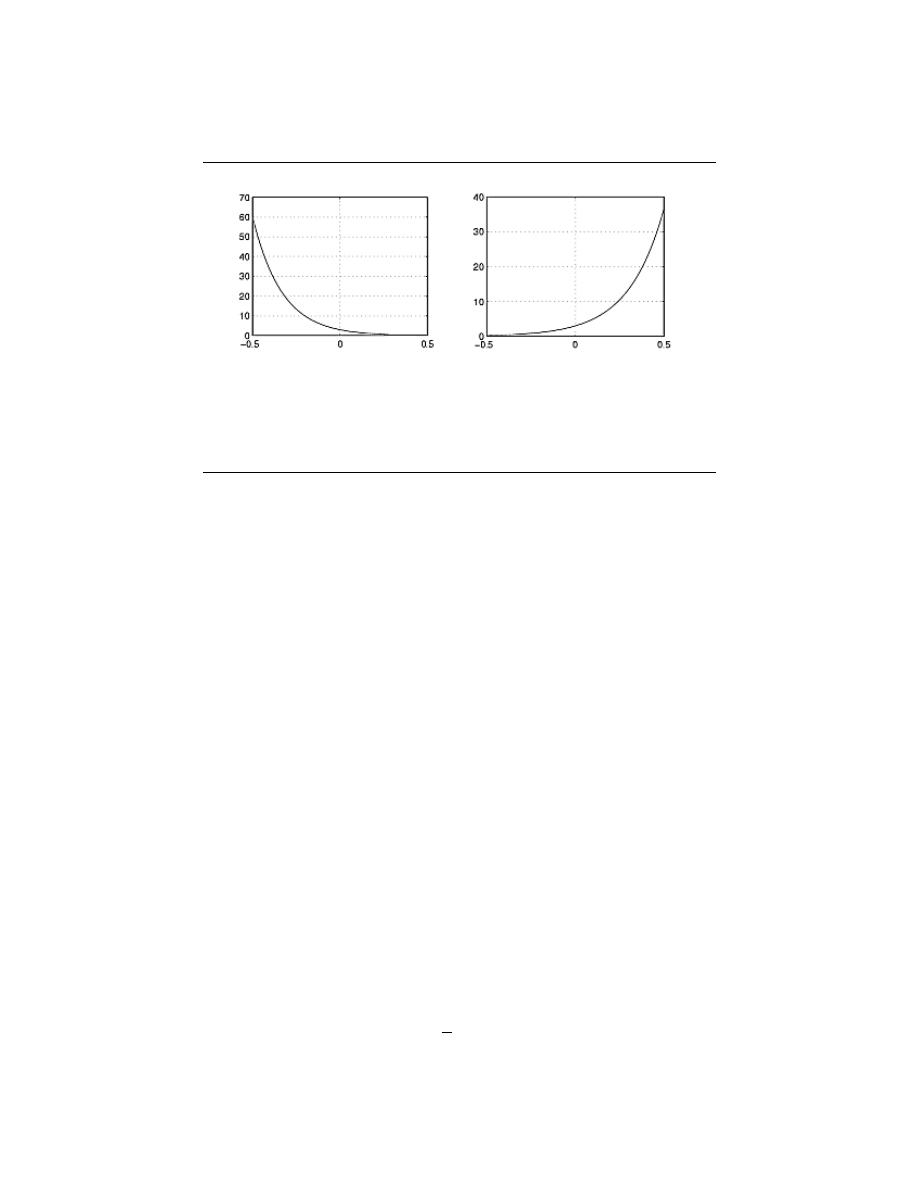

(a)

(b)

Figure 2.26:

Examples of Real Exponentials (a) Decaying Exponential (b) Growing

Exponential

The most important property of the unit-impulse is shown in the following integral:

Z

∞

−∞

δ (t) dt = 1

(2.17)

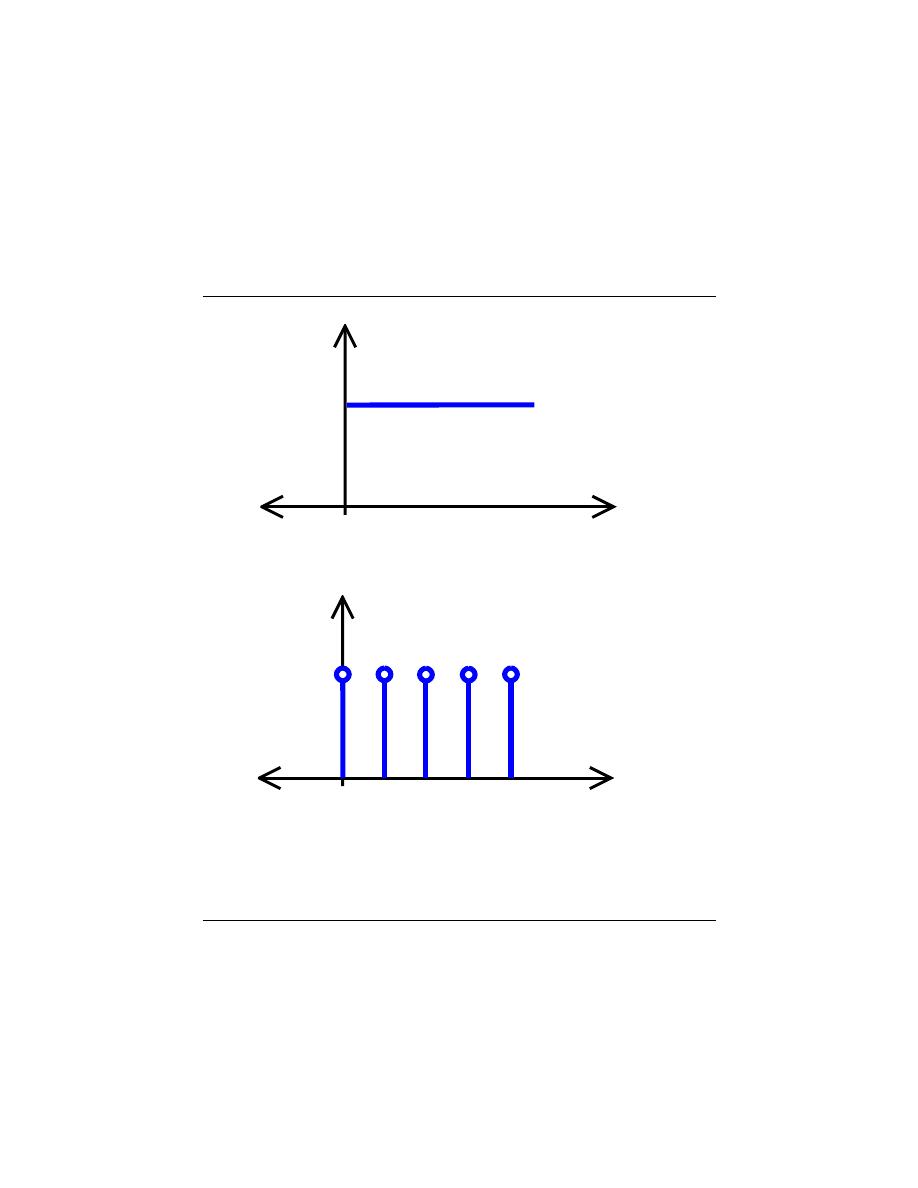

2.5.5 Unit-Step Function

Another very basic signal is the unit-step function that is defined as

u (t) =

1 if t < 0

0 if t ≥ 0

(2.18)

Note that the step function is discontinuous at the origin; however, it does not need to

be defined here as it does not matter in signal theory. The step function is a useful tool for

testing and for defining other signals. For example, when different shifted versions of the

step function are multiplied by other signals, one can select a certain portion of the signal

and zero out the rest.

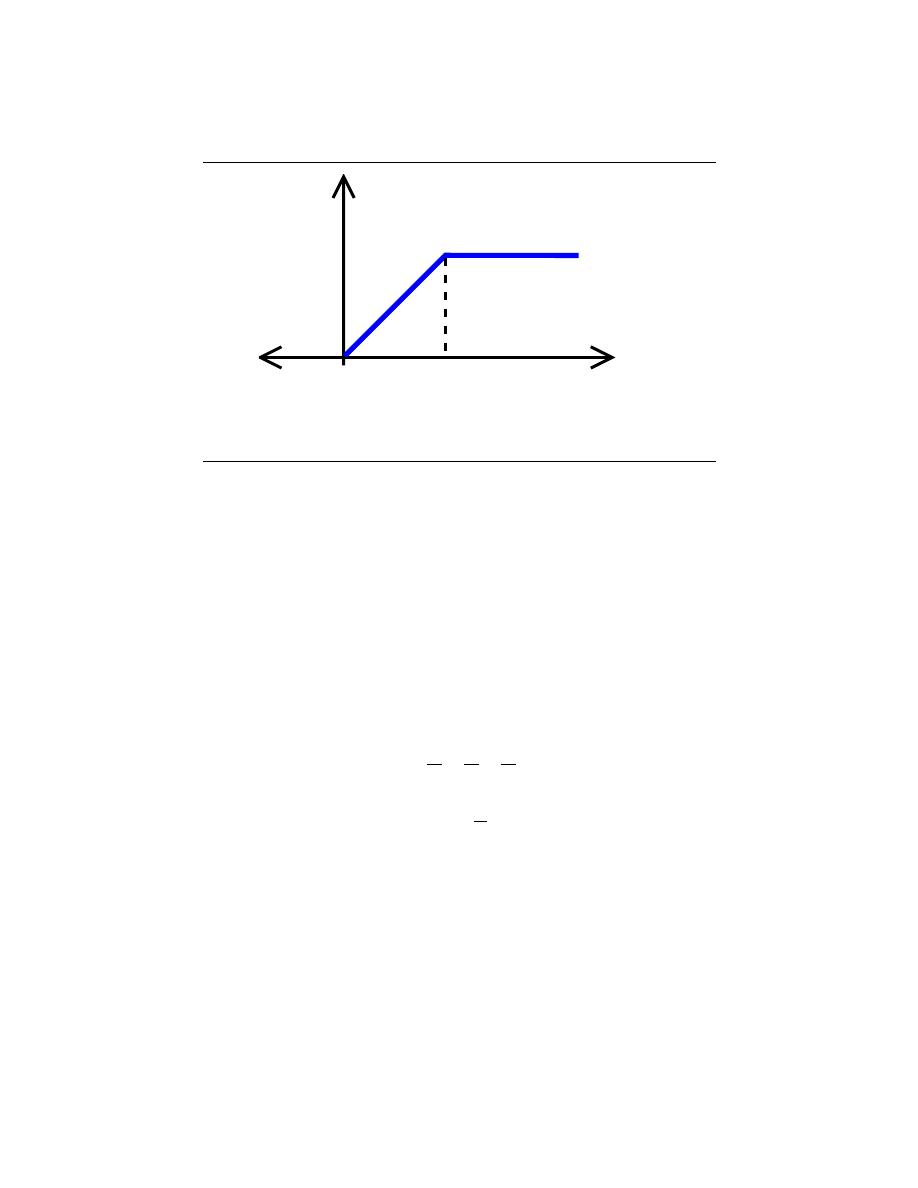

2.5.6 Ramp Function

The ramp function is closely related to the unit-step discussed above. Where the unit-

step goes from zero to one instantaneously, the ramp function better resembles a real-world

signal, where there is some time needed for the signal to increase from zero to its set value,

one in this case. We define a ramp function as follows

r (t) =

0 if t < 0

t

t

0

if 0 ≤ t ≤ t

0

1 if t > t

0

(2.19)

29

t

1

(a)

t

1

(b)

Figure 2.27:

Basic Step Functions (a) Continuous-Time Unit-Step Function (b)

Discrete-Time Unit-Step Function

30

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

t

1

t

0

Figure 2.28:

Ramp Function

3.6 The Complex Exponential

2.6.1 The Exponential Basics

The complex exponential is one of the most fundamental and important signal in signal

and system analysis. Its importance comes from its functions as a basis for periodic signals

as well as being able to characterize linear, time-invariant signals. Before proceeding, you

should be familiar with the ideas and functions of complex numbers.

2.6.1.1 Basic Exponential

For all numbers x, we easily derive and define the exponential function from the Taylor’s

series below:

e

x

= 1 +

x

1

1!

+

x

2

2!

+

x

3

3!

+ . . .

(2.20)

e

x

=

∞

X

k=0

1

k!

x

k

(2.21)

We can prove, using the ratio test, that this series does indeed converge. Therefore, we can

state that the exponential function shown above is continuous and easily defined.

From this definition, we can prove the following property for exponentials that will be

very useful, especially for the complex exponentials discussed in the next section.

e

x

1

+x

2

= (e

x

1

) (e

x

2

)

(2.22)

2.6.1.2 Complex Continuous-Time Exponential

Now for all complex numbers s, we can define the complex continuous-time exponential

signal as

f (t)

=

Ae

st

=

Ae

jωt

(2.23)

31

where A is a constant, t is our independent variable for time, and for s imaginary, s = jω.

Finally, from this equation we can reveal the ever important Euler’s Identity (for more

information on Euler read this short biography

1

):

Ae

jωt

= Acos (ωt) + j (Asin (ωt))

(2.24)

From Euler’s Identity we can easily break the signal down into its real and imaginary

components. Also we can see how exponentials can be combined to represet any real signal.

By modifying their frequency and phase, we can represent any signal through a superposity

of many signals - all capable of being represented by an exponential.

The above expressions do not include any information on phase however. We can further

generalize our above expressions for the exponential to generalize sinusoids with any phase

by making a final substitution for s, s = σ + jω, which leads us to

f (t)

=

Ae

st

=

Ae

(σ+jω)t

=

Ae

σt

e

jωt

(2.25)

where we define S as the complex amplitude , or phasor , from the first two terms of

the above equation as

S = Ae

σt

(2.26)

Going back to Euler’s Identity, we can rewrite the exponentials as sinusoids, where the phase

term becomes much more apparent.

f (t)

=

Ae

σt

(cos (ωt) + jsin (ωt))

=

Acos (σ + ωt) + jAsin (σ + ωt)

(2.27)

As stated above we can easily break this formula into its real and imaginary part as follows:

Re (f (t)) = Ae

σt

cos (ωt)

(2.28)

Im (f (t)) = Ae

σt

sin (ωt)

(2.29)

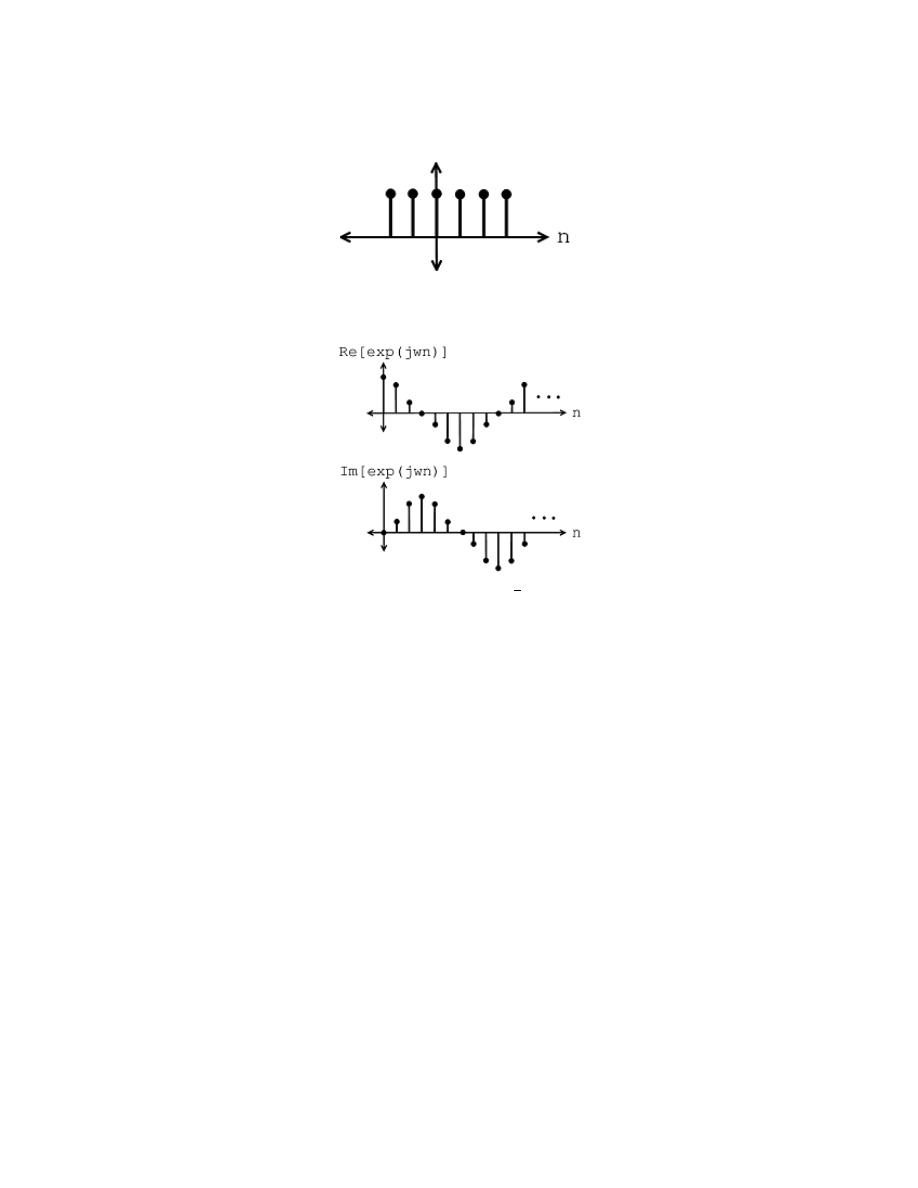

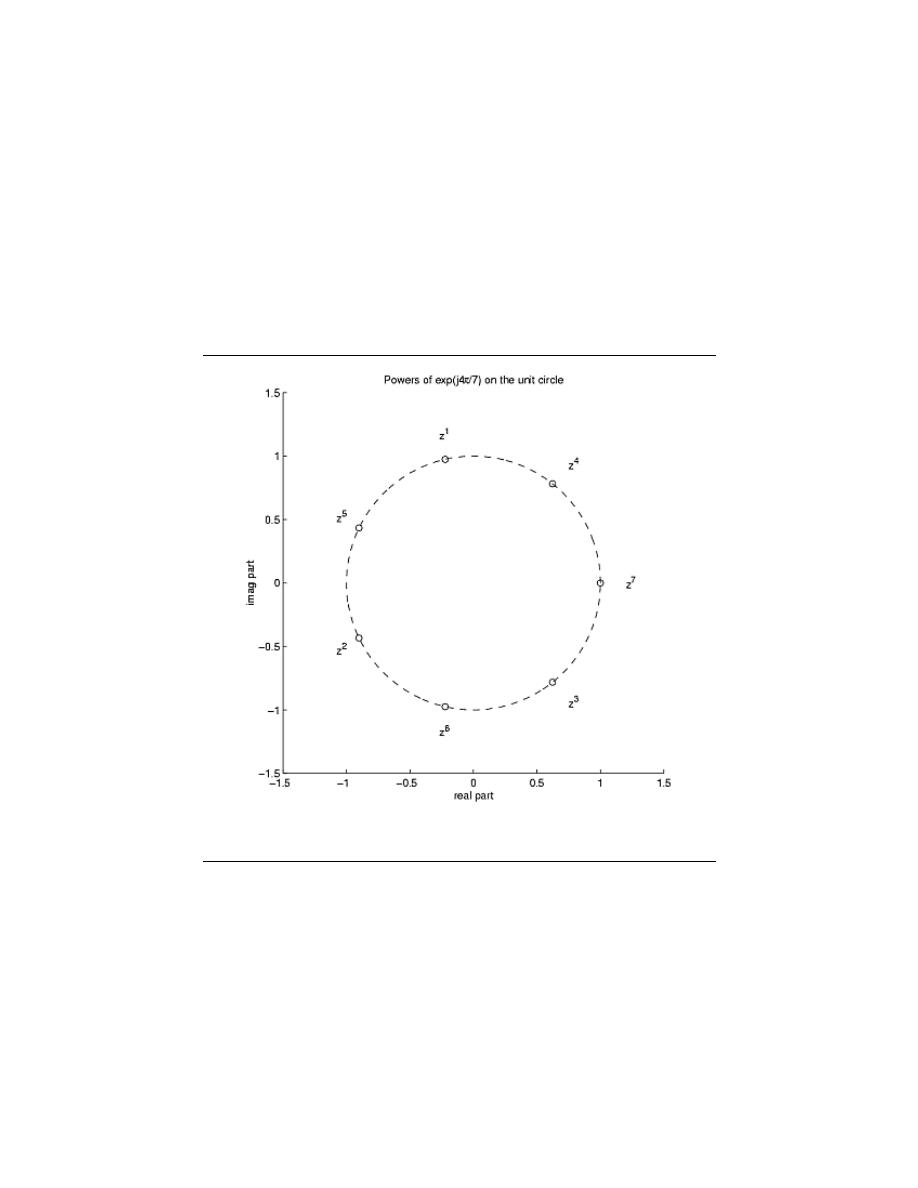

2.6.1.3 Complex Discrete-Time Exponential

Finally we have reached the last form of the exponential signal that we will be interested

in, the discrete-time exponential signal , which we will not give as much detail about

as we did for its continuous-time counterpart, because they both follow the same properties

and logic discussed above. Because it is discrete, there is only a slightly different notation

used to represents its discrete nature

f [n]

=

Be

snT

=

Be

jωnT

(2.30)

where nT represents the discrete-time instants of our signal.

2.6.2 Euler’s Relation

Along with Euler’s Identity, Euler also described a way to represent a complex exponential

signal in terms of its real and imaginary parts through Euler’s Relation :

cos (ωt) =

e

jwt

+ e

−(jwt)

2

(2.31)

1

http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/∼history/Mathematicians/Euler.html

32

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

(a)

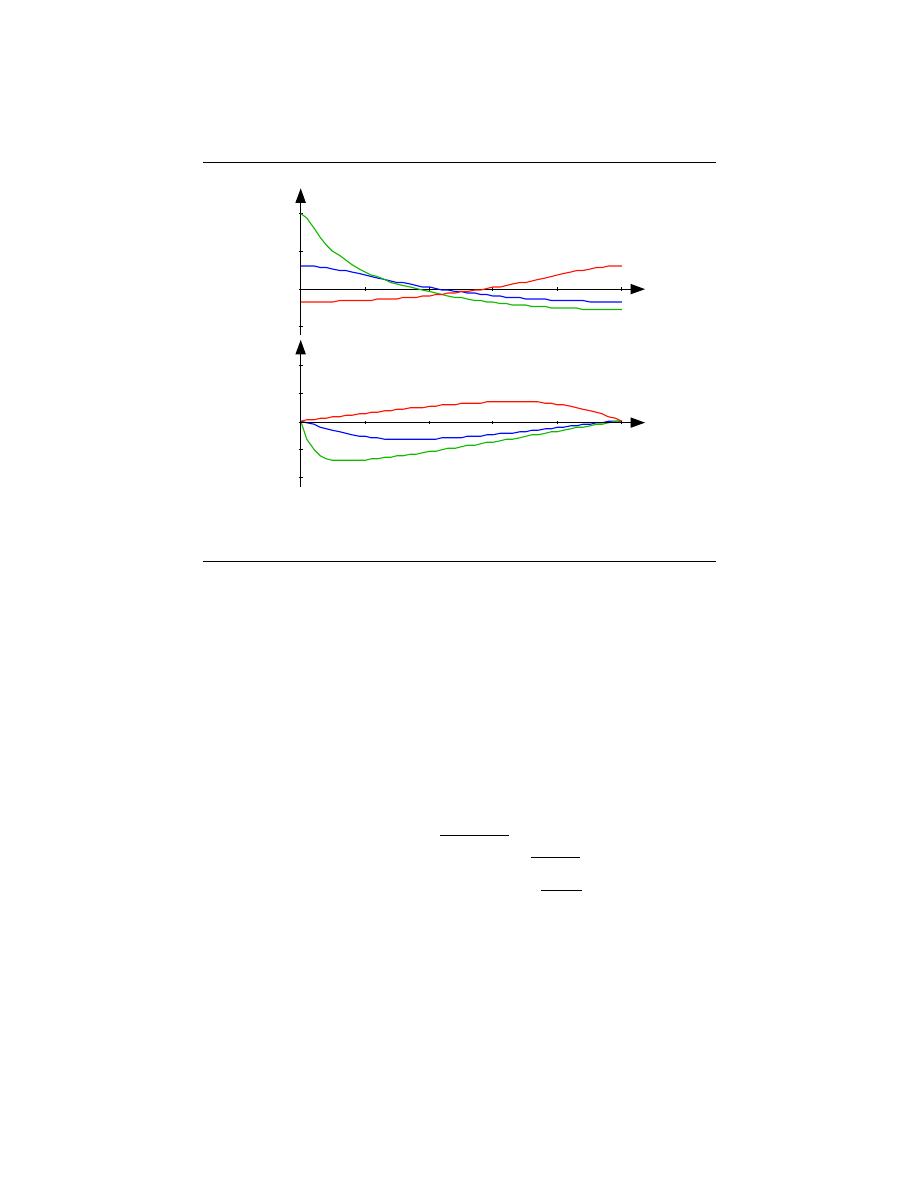

(b)

(c)

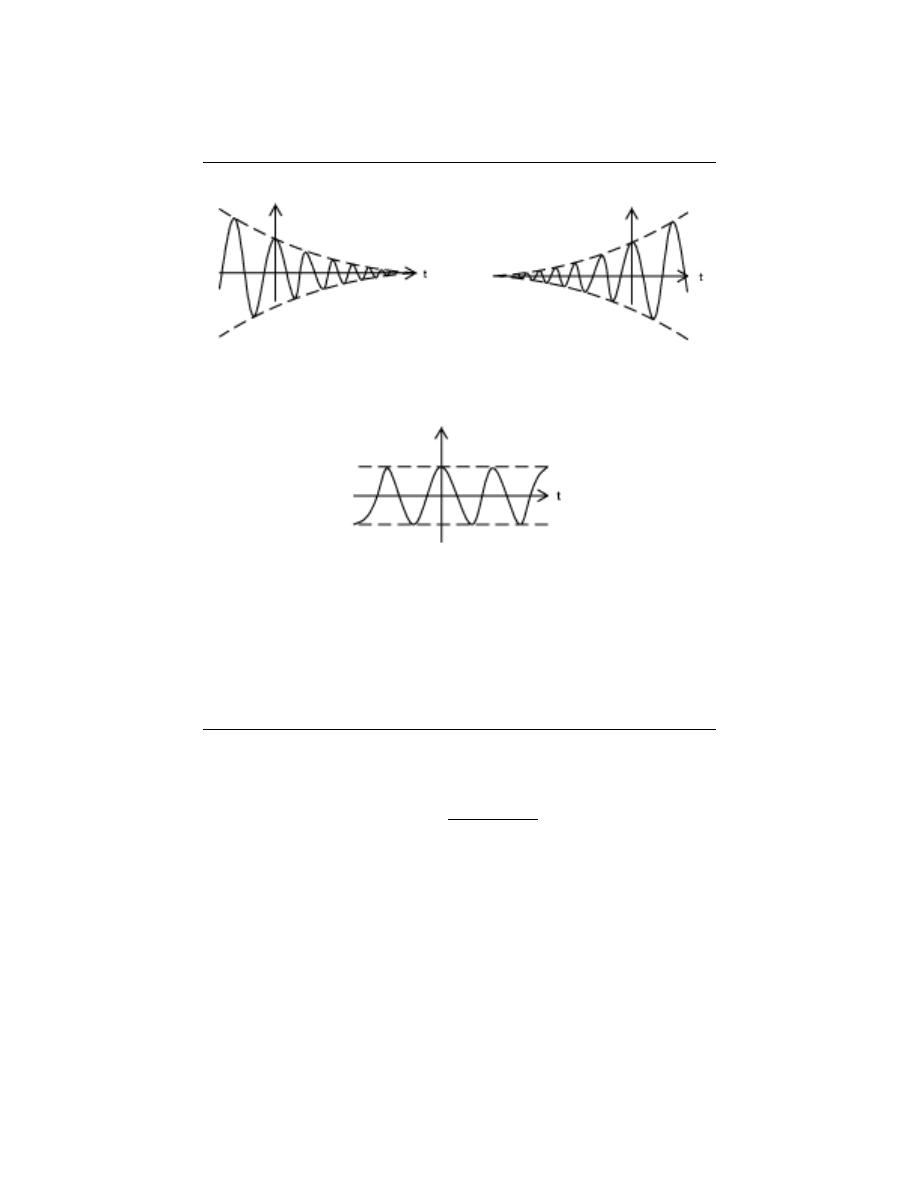

Figure 2.29:

The shapes possible for the real part of a complex exponential. Notice

that the oscillations are the result of a cosine, as there is a local maximum at t = 0. (a)

If σ is negative, we have the case of a decaying exponential window. (b) If σ is positive,

we have the case of a growing exponential window. (c) If σ is zero, we have the case of a

constant window.

sin (ωt) =

e

jwt

− e

−(jwt)

2j

(2.32)

e

jwt

= cos (ωt) + jsin (ωt)

(2.33)

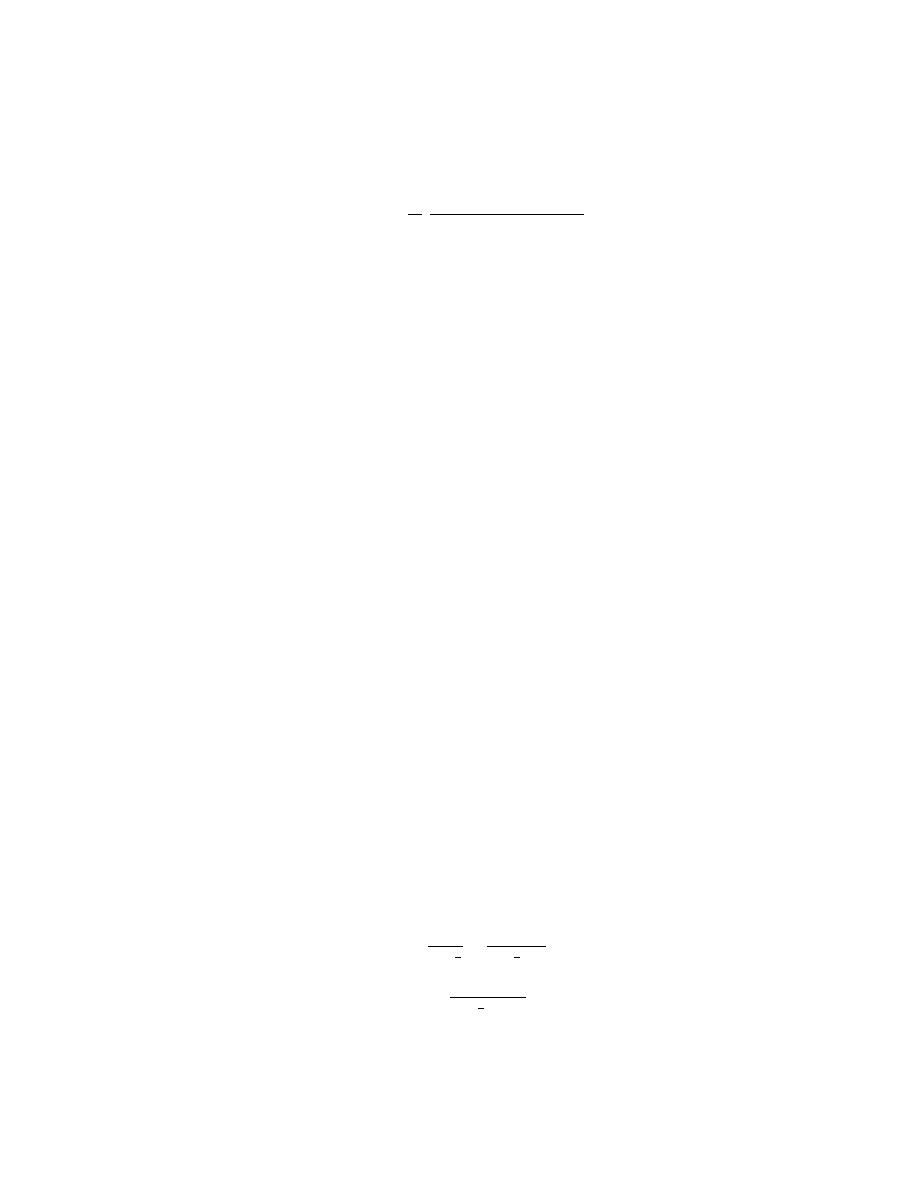

2.6.3 Drawing the Complex Exponential

At this point, we have shown how the complex exponential can be broken up into its real

part and its imaginary part. It is now worth looking at how we can draw each of these

parts. We can see that both the real part and the imaginay part have a sinusoid times a

real exponential. We also know that sinusoids oscillate between one and negative one. From

this it becomes apparent that the real and imaginary parts of the complex exponential will

each oscillate between a window defined by the real exponential part.

While the σ determines the rate of decay/growth, the ω part determines the rate of the

oscillations. This is apparent by noticing that the ω is part of the argument to the sinusoidal

part.

33

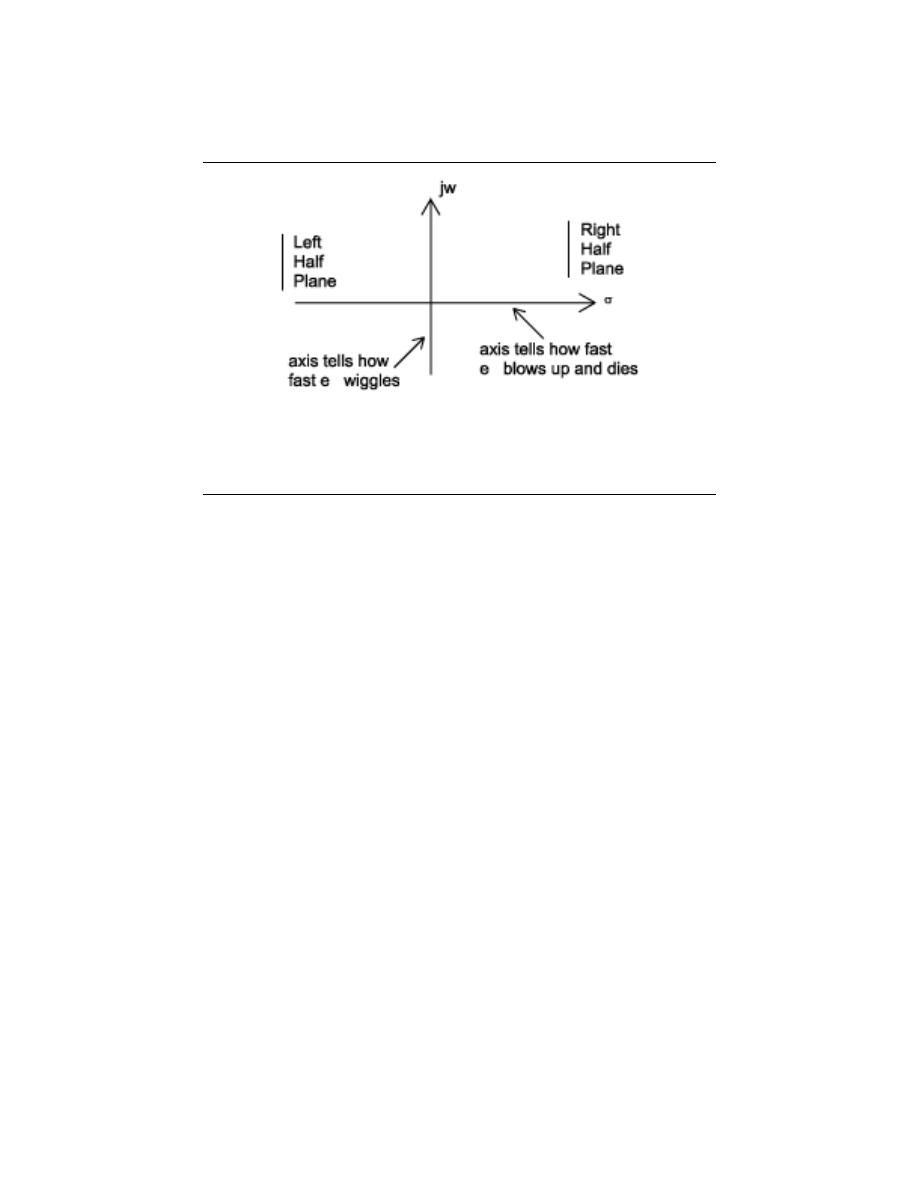

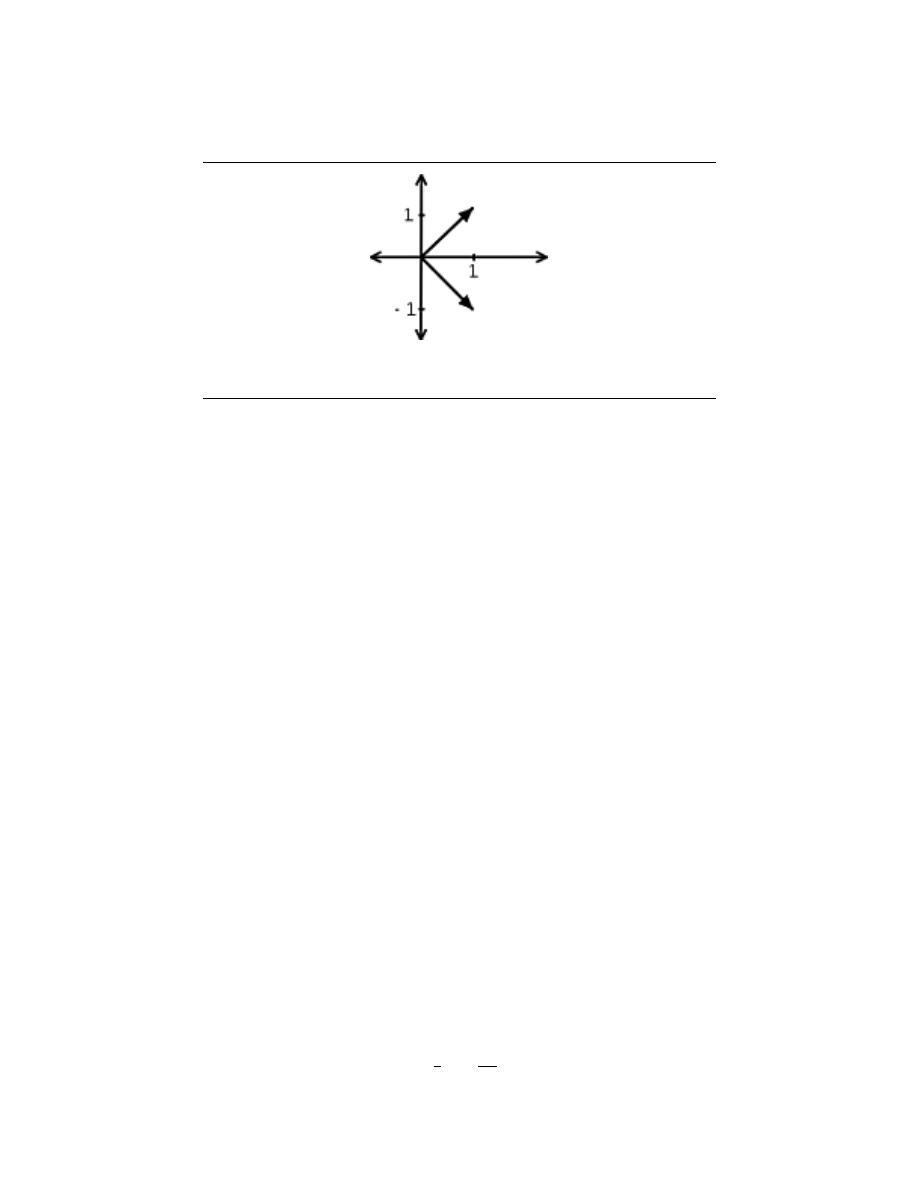

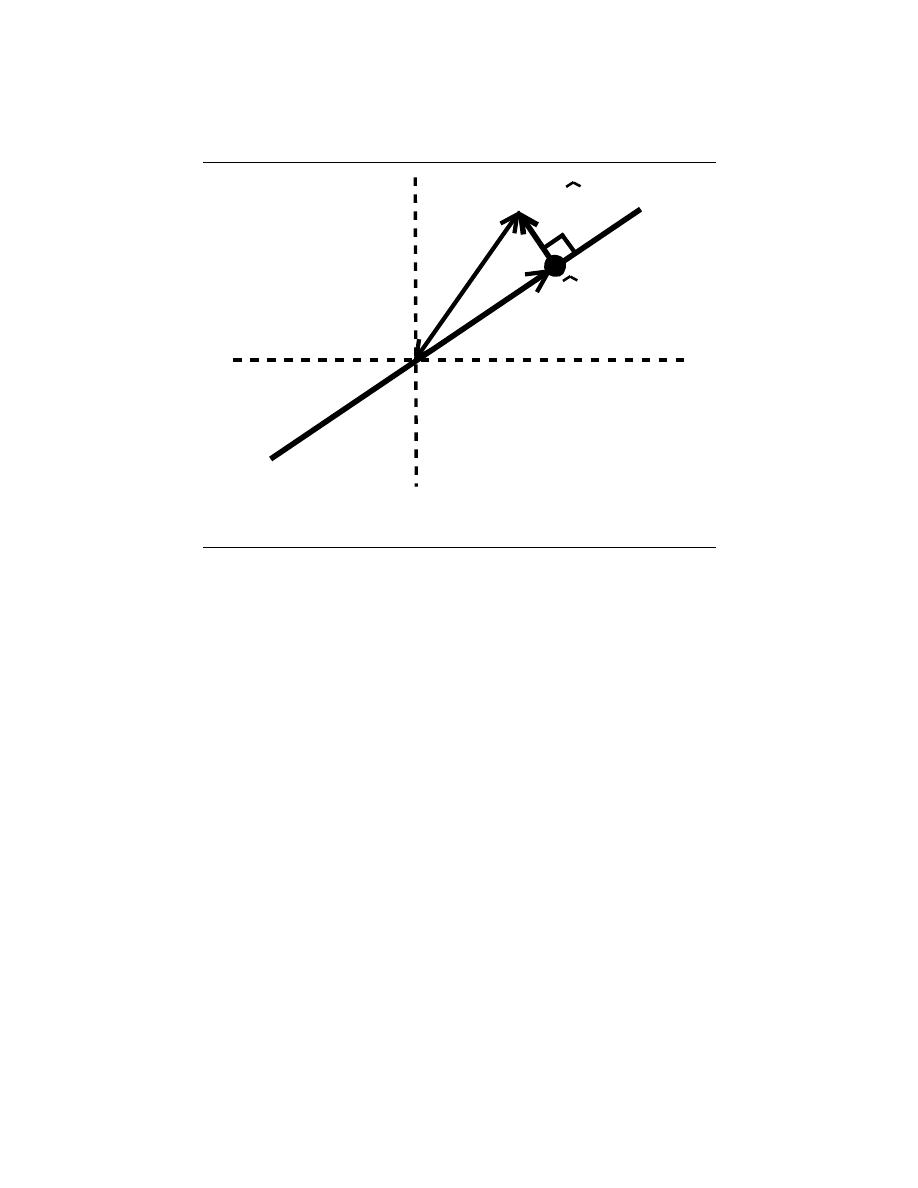

Figure 2.30:

This is the s-plane. Notice that any time s lies in the right half plane, the

complex exponential will grow through time, while any time it lies in the left half plane

it will decay.

Exercise 2.1:

What do the imaginary parts of the complex emponentials drawn above look like?

Solution:

They look the same except the oscillation is that of a sinusoid as opposed to a

cosinusoid (ie it passes through the origin rather than being a local maximum at

t = 0).

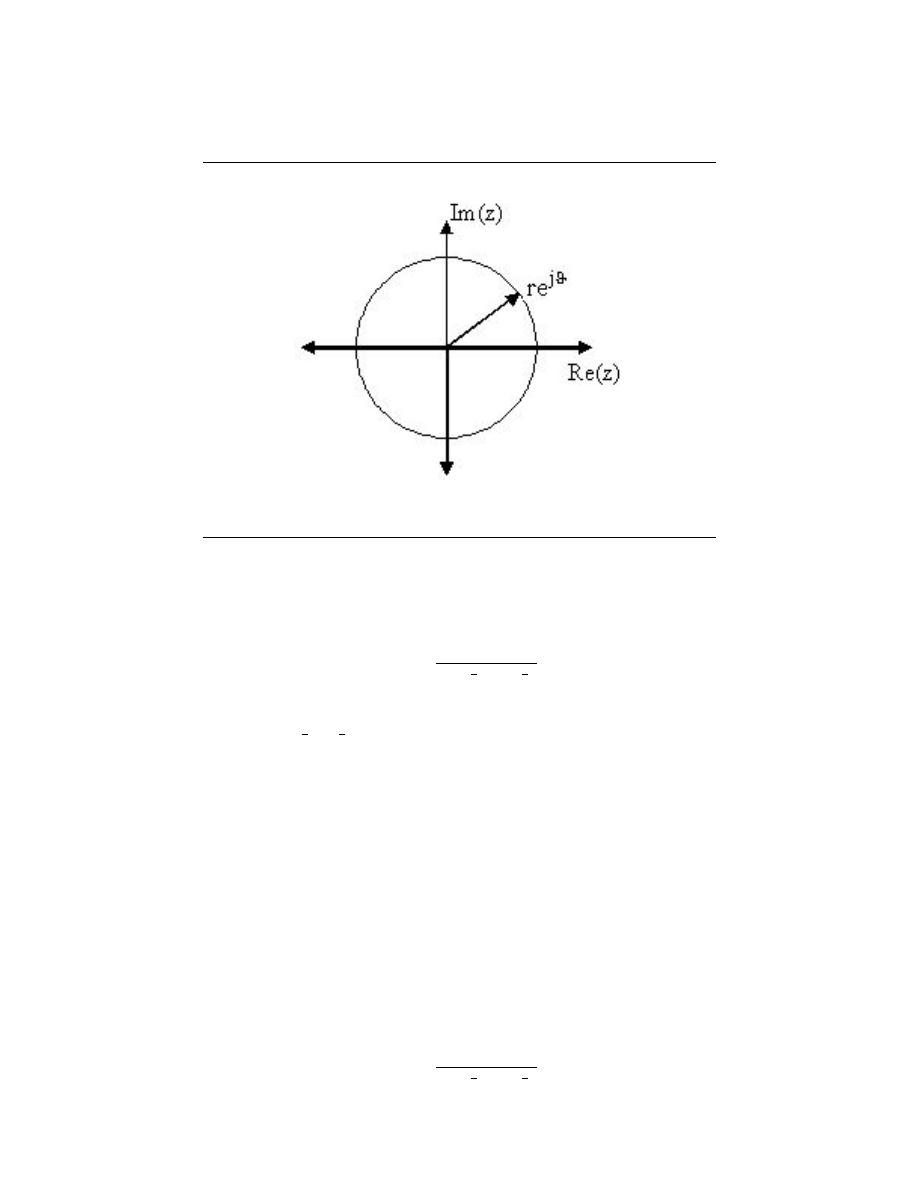

2.6.4 The Complex Plane

It becomes extremely useful to view the complex variable s as a point in the complex plane

(the s-plane ).

3.7 Discrete-Time Systems in the Time-Domain

A discrete-time signal s (n) is delayed by n

0

samples when we write s (n − n

0

), with n

0

> 0.

Choosing n

0

to be negative advances the signal along the integers. As opposed to analog

delays (pg ??), discrete-time delays can only be integer valued. In the frequency domain,

delaying a signal corresponds to a linear phase shift of the signal’s discrete-time Fourier

transform:

s (n − n

0

) ↔ e

−(j2πf n

0

)

S e

j2πf

.

Linear discrete-time systems have the superposition property.

S (a

1

x

1

(n) + a

2

x

2

(n)) = a

1

S (x

1

(n)) + a

2

S (x

2

(n))

(2.34)

A discrete-time system is called shift-invariant (analogous to time-invariant analog sys-

tems (pg ??)) if delaying the input delays the corresponding output.

If S (x (n)) = y (n), then

S (x (n − n

0

)) = y (n − n

0

)

(2.35)

34

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

We use the term shift-invariant to emphasize that delays can only have integer values in

discrete-time, while in analog signals, delays can be arbitrarily valued.

We want to concentrate on systems that are both linear and shift-invariant. It will

be these that allow us the full power of frequency-domain analysis and implementations.

Because we have no physical constraints in ”constructing” such systems, we need only a

mathematical specification. In analog systems, the differential equation specifies the input-

output relationship in the time-domain. The corresponding discrete-time specification is

the difference equation .

y (n) = a

1

y (n − 1) + · · · + a

p

y (n − p) + b

0

x (n) + b

1

x (n − 1) + · · · + b

q

x (n − q)

(2.36)

Here, the output signal y (n) is related to its past values y (n − l), l = {1, . . . , p}, and

to the current and past values of the input signal x (n). The system’s characteristics are

determined by the choices for the number of coefficients p and q and the coefficients’ values

{a

1

, . . . , a

p

} and {b

0

, b

1

, . . . , b

q

}.

aside:

There is an asymmetry in the coefficients: where is a

0

? This coefficient

would multiply the y(n) term in Equation 2.36. We have essentially divided the

equation by it, which does not change the input-output relationship. We have thus

created the convention that a

0

is always one.

As opposed to differential equations, which only provide an implicit description of a

system (we must somehow solve the differential equation), difference equations provide an

explicit way of computing the output for any input.

We simply express the difference

equation by a program that calculates each output from the previous output values, and

the current and previous inputs.

Difference equations are usually expressed in software with for loops.

A MATLAB

program that would compute the first 1000 values of the output has the form

for n=1:1000

y(n) = sum(a.*y(n-1:-1:n-p)) + sum(b.*x(n:-1:n-q));

end

An important detail emerges when we consider making this program work; in fact, as

written it has (at least) two bugs. What input and output values enter into the computation

of y(1)? We need values for y(0), y(-1), ..., values we have not yet computed. To compute

them, we would need more previous values of the output, which we have not yet computed.

To compute these values, we would need even earlier values, ad infinitum. The way out

of this predicament is to specify the system’s initial conditions : we must provide the p

output values that occurred before the input started. These values can be arbitrary, but

the choice does impact how the system responds to a given input. One choice gives rise to a

linear system: Make the initial conditions zero. The reason lies in the definition of a linear

system: The only way that the output to a sum of signals can be the sum of the individual

outputs occurs when the initial conditions in each case are zero.

Exercise 2.2:

The initial condition issue resolves making sense of the difference equation for

inputs that start at some index. However, the program will not work because of a

programming, not conceptual, error. What is it? How can it be ”fixed?”

Solution:

The indices can be negative, and this condition is not allowed in MATLAB. To fix

it, we must start the signals later in the array.

35

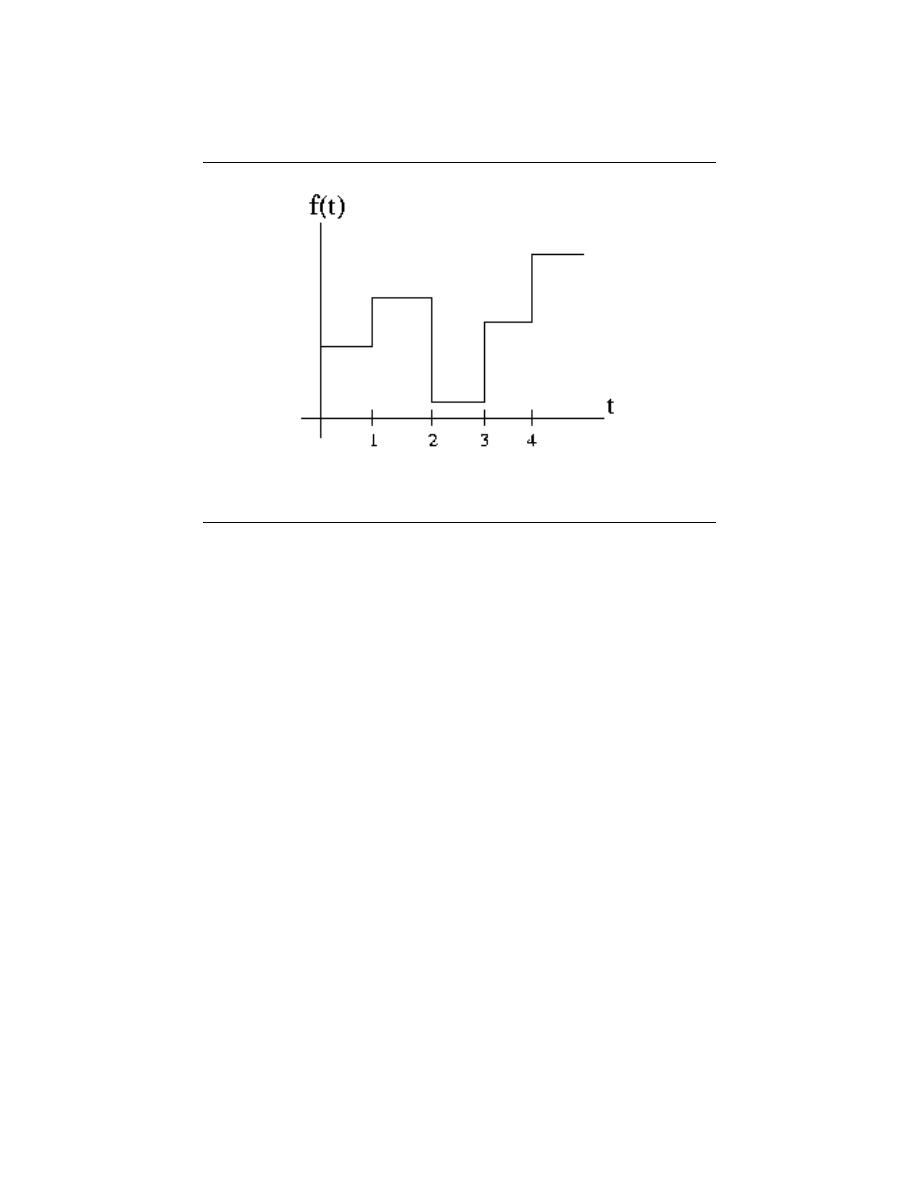

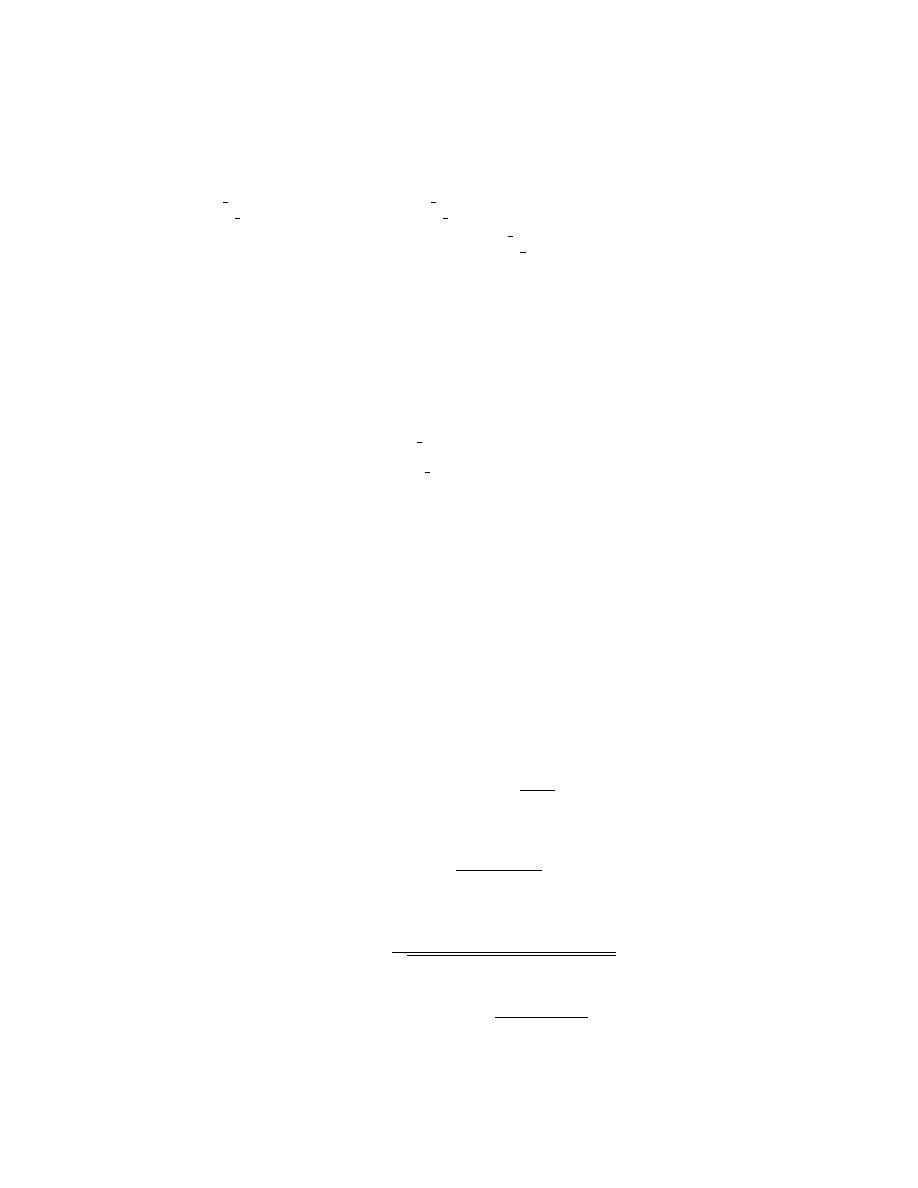

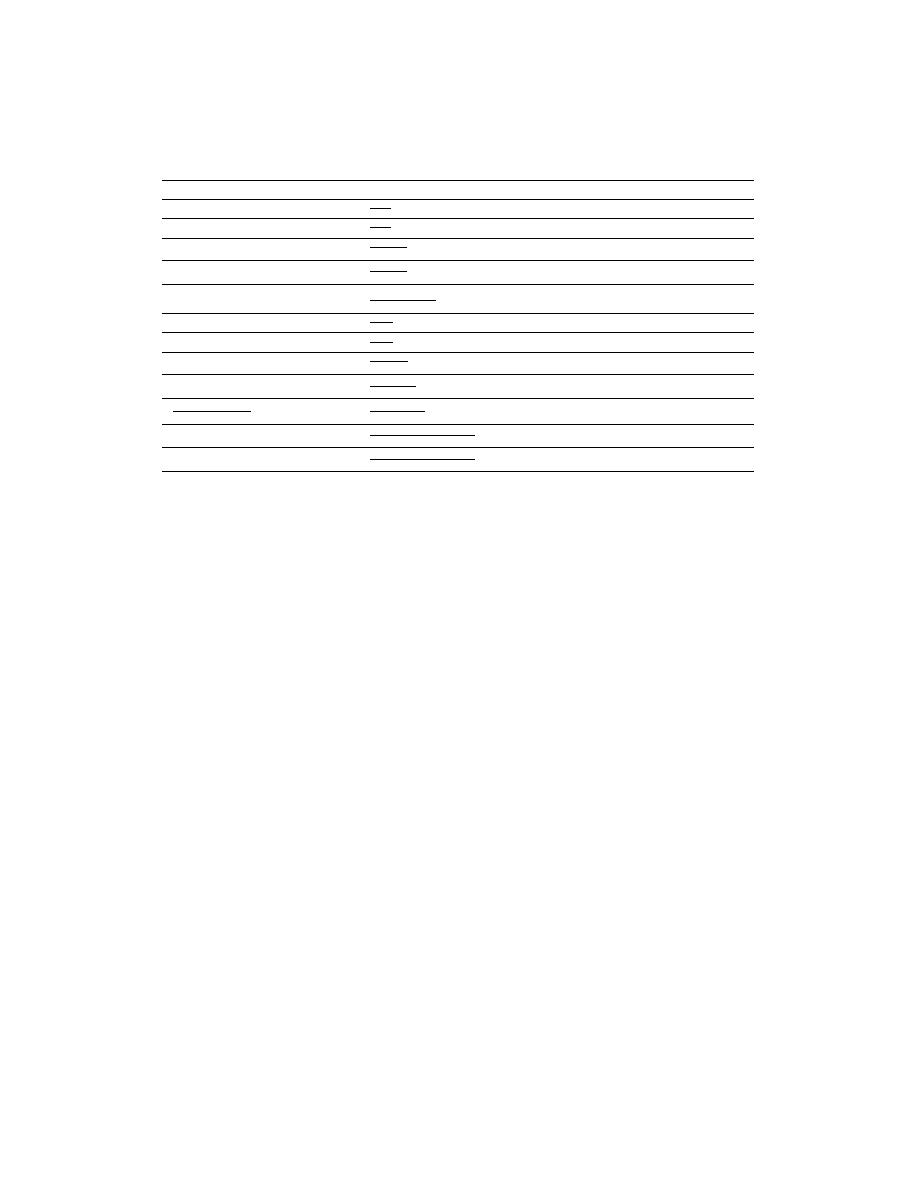

Table 1

n

x(n)

y(n)

-1

0

0

0

1

b

1

0

ba

2

0

ba

2

:

0

:

n

0

ba

n

Figure 2.31

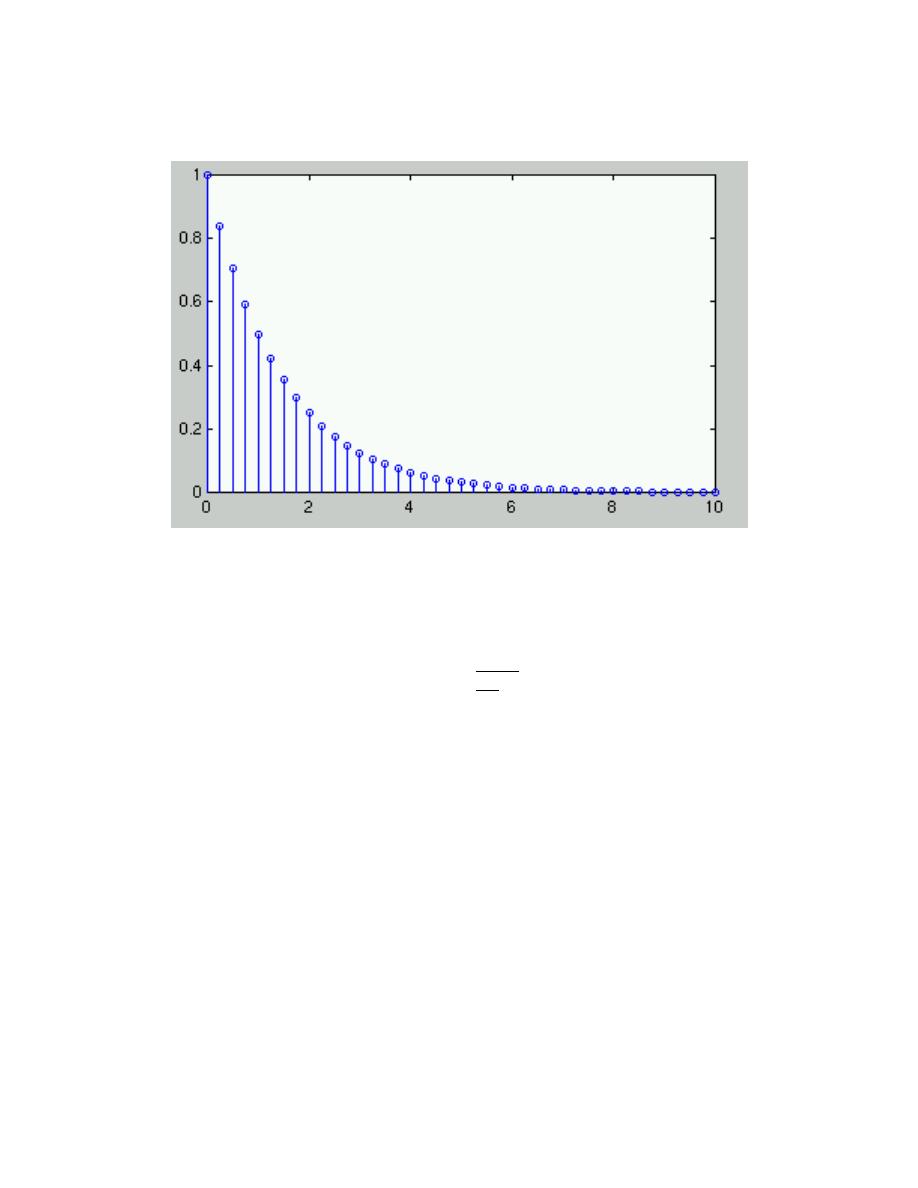

Example 2.2:

Let’s consider the simple system having p = 1 and q = 0.

y (n) = ay (n − 1) + bx (n)

(2.37)

To compute the output at some index, this difference equation says we need to know

what the previous output y (n − 1) and what the input signal is at that moment

of time. In more detail, let’s compute this system’s output to a unit-sample input:

x (n) = δ (n). Because the input is zero for negative indices, we start by trying to

compute the output at n = 0.

y (0) = ay (−1) + b

(2.38)

What is the value of y (−1)? Because we have used an input that is zero for all

negative indices, it is reasonable to assume that the output is also zero. Certainly,

the difference equation would not describe a linear system if the input that is zero

for all time did not produce a zero output. With this assumption, y (−1) = 0,

leaving y (0) = b. For n > 0, the input unit-sample is zero, which leaves us with

the difference equation ∀n, n > 0 : y (n) = ay (n − 1). We can envision how the

filter responds to this input by making a table.

y (n) = ay (n − 1) + bδ (n)

(2.39)

Coefficient values determine how the output behaves. The parameter b can be any

value, and serves as a gain. The effect of the parameter a is more complicated

(Figure 2.31). If it equals zero, the output simply equals the input times the gain

b. For all non-zero values of a, the output lasts forever; such systems are said to

be IIR ( I nfinite I mpulse Response). The reason for this terminology is that the

unit sample also known as the impulse (especially in analog situations), and the

system’s response to the ”impulse” lasts forever. If a is positive and less than one,

the output is a decaying exponential. When a = 1, the output is a unit step. If a is

negative and greater than −1, the output oscillates while decaying exponentially.

When a = 1, the output changes sign forever, alternating between b and −b. More

dramatic effects when |a| > 1; whether positive or negative, the output signal

becomes larger and larger, growing exponentially.

36

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

1

n

y(n)

a = 0.5, b = 1

n

-1

1

y(n)

a = –0.5, b = 1

n

0

2

4

y(n)

a = 1.1, b = 1

x(n)

n

n

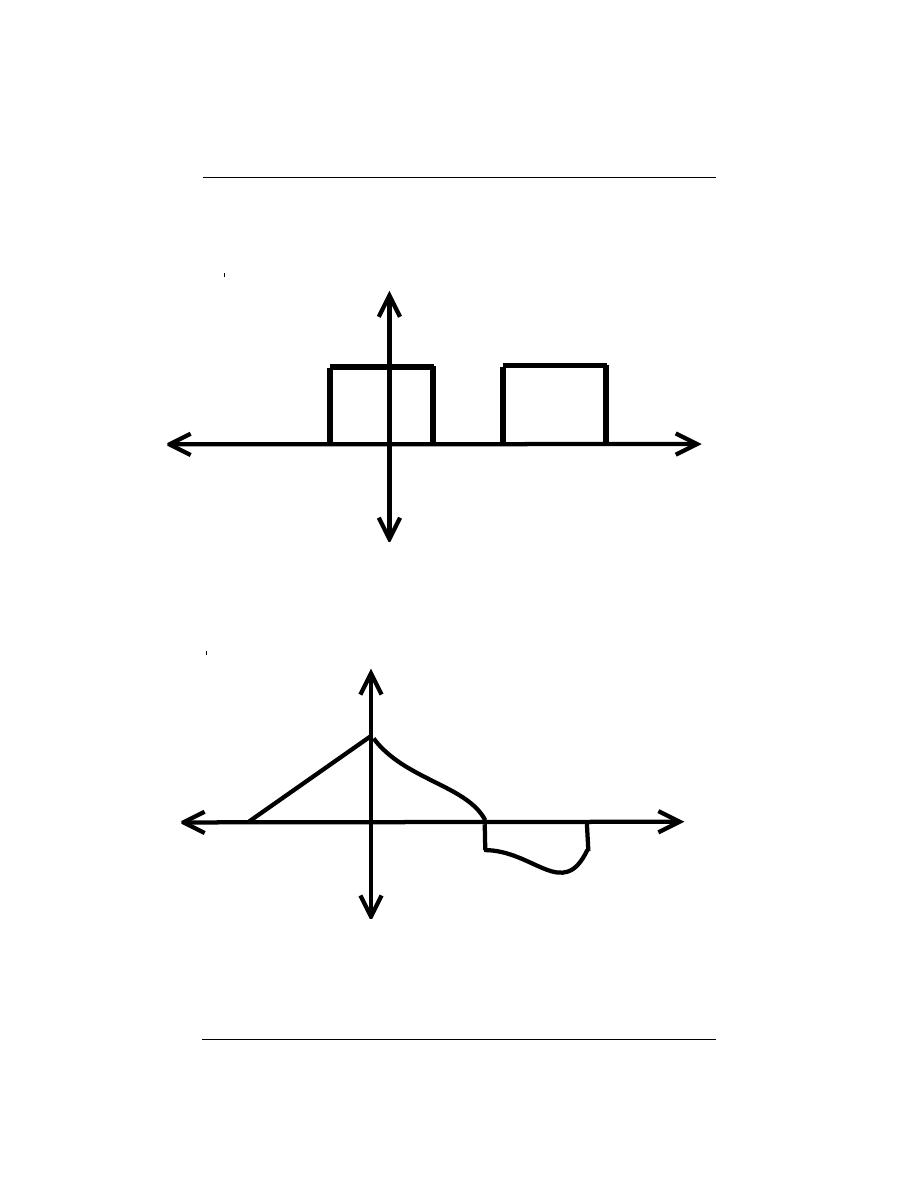

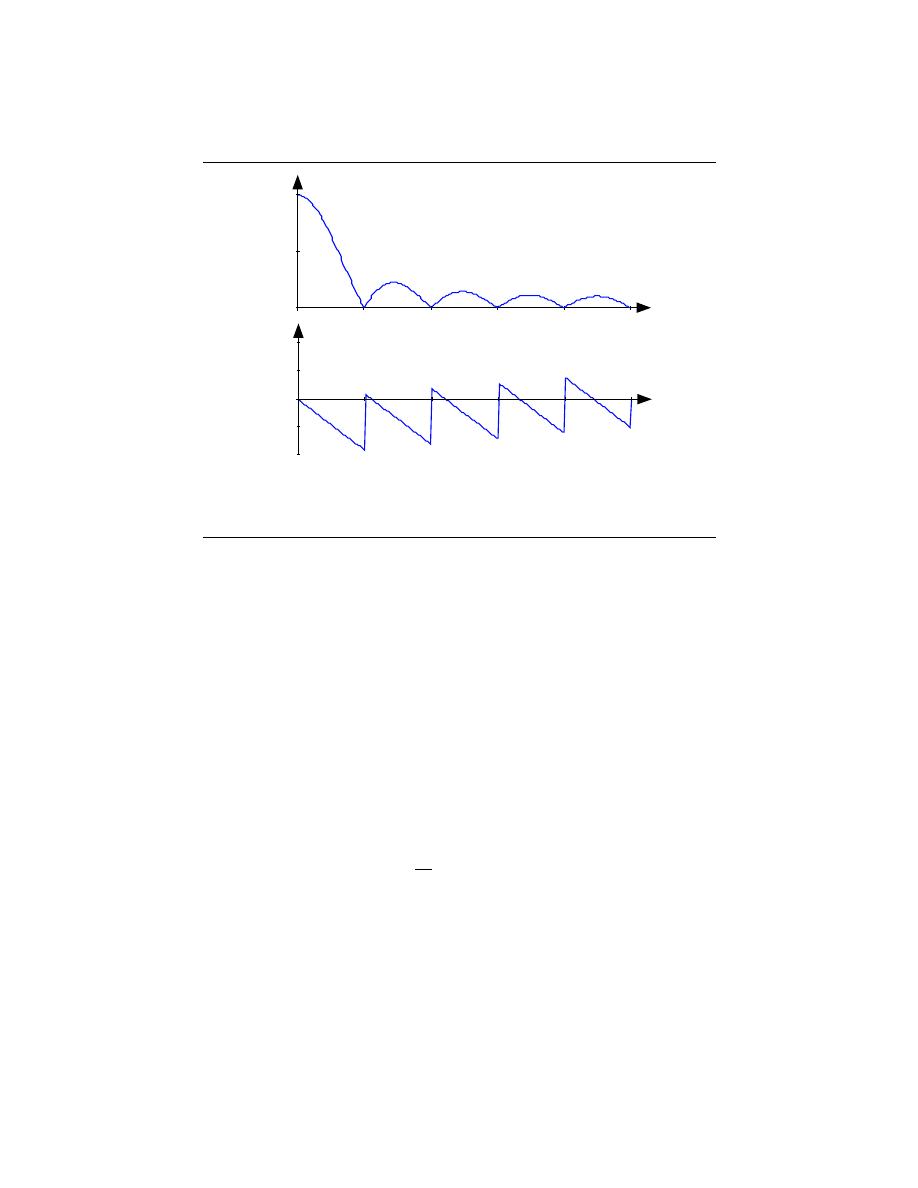

Figure 2.32:

The input to the simple example system, a unit sample, is shown at the

top, with the outputs for several system parameter values shown below.

Positive values of a are used in population models to describe how population size

increases over time. Here, n might correspond to generation. The difference equa-

tion says that the number in the next generation is some multiple of the previous

one. If this multiple is less than one, the population becomes extinct; if greater

than one, the population flourishes. The same difference equation also describes

the effect of compound interest on deposits. Here, n indexes the times at which

compounding occurs (daily, monthly, etc.), a equals the compound interest rate

plusone, and b = 1 (the bank provides no gain). In signal processing applications,

we typically require that the output remain bounded for any input. For our ex-

ample, that means that we restrict |a| = 1 and chose values for it and the gain

according to the application.

Exercise 2.3:

Note that the difference equation (Equation 2.36),

y (n) = a

1

y (n − 1) + · · · + a

p

y (n − p) + b

0

x (n) + b

1

x (n − 1) + · · · + b

q

x (n − q)

does not involve terms like y (n + 1) or x (n + 1) on the equation’s right side. Can

such terms also be included? Why or why not?

Solution:

Such terms would require the system to know what future input or output values

would be before the current value was computed. Thus, such terms can cause

difficulties.

Example 2.3:

A somewhat different system has no ”a” coefficients. Consider the difference equa-

tion

y (n) =

1

q

(x (n) + · · · + x (n − q + 1))

(2.40)

Because this system’s output depends only on current and previous input values, we

need not be concerned with initial conditions. When the input is a unit-sample,

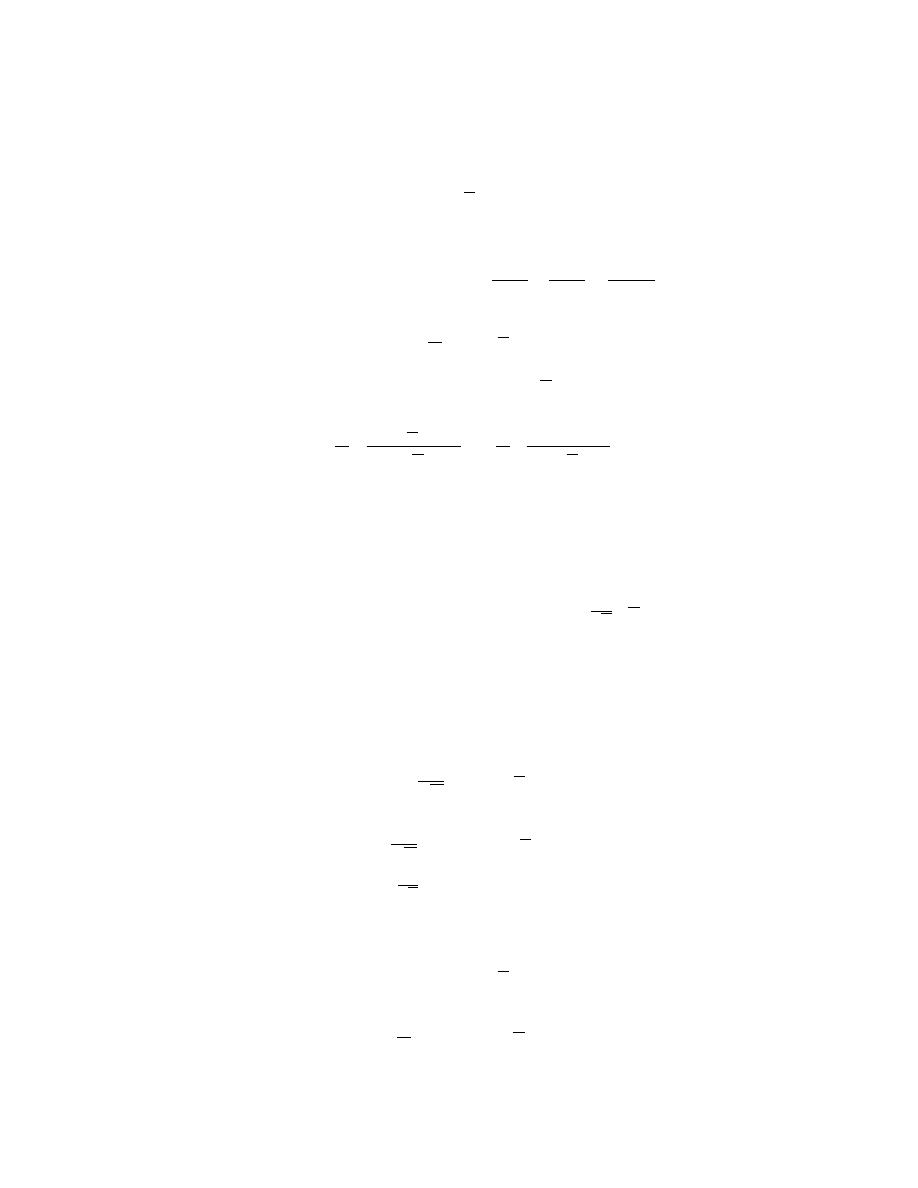

37

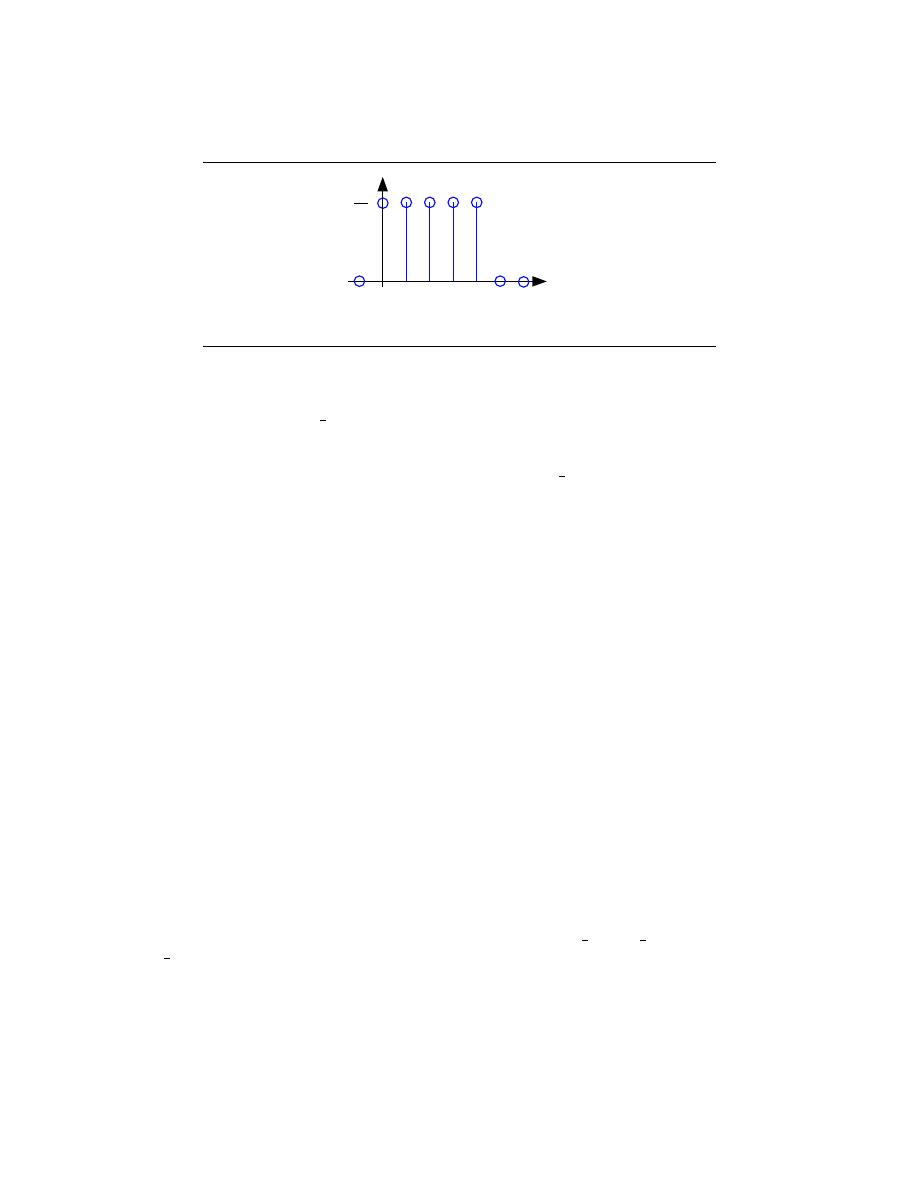

y(n)

n

1

5

Figure 2.33: The plot shows the unit-sample response of a length-5 boxcar filter.

the output equals

1

q

for n = {0, . . . , q − 1}, then equals zero thereafter. Such

systems are said to be FIR ( Finite I mpulse Response) because their unit sample

responses have finite duration. Plotting this response (Figure 2.33) shows that the

unit-sample response is a pulse of width q and height

1

q

. This waveform is also

known as a boxcar, hence the name boxcar filter given to this system. (We’ll

derive its frequency response and develop its filtering interpretation in the next

section.) For now, note that the difference equation says that each output value

equals the average of the input’s current and previous values. Thus, the output

equals the running average of input’s previous q values. Such a system could be

used to produce the average weekly temperature (q = 7) that could be updated

daily.

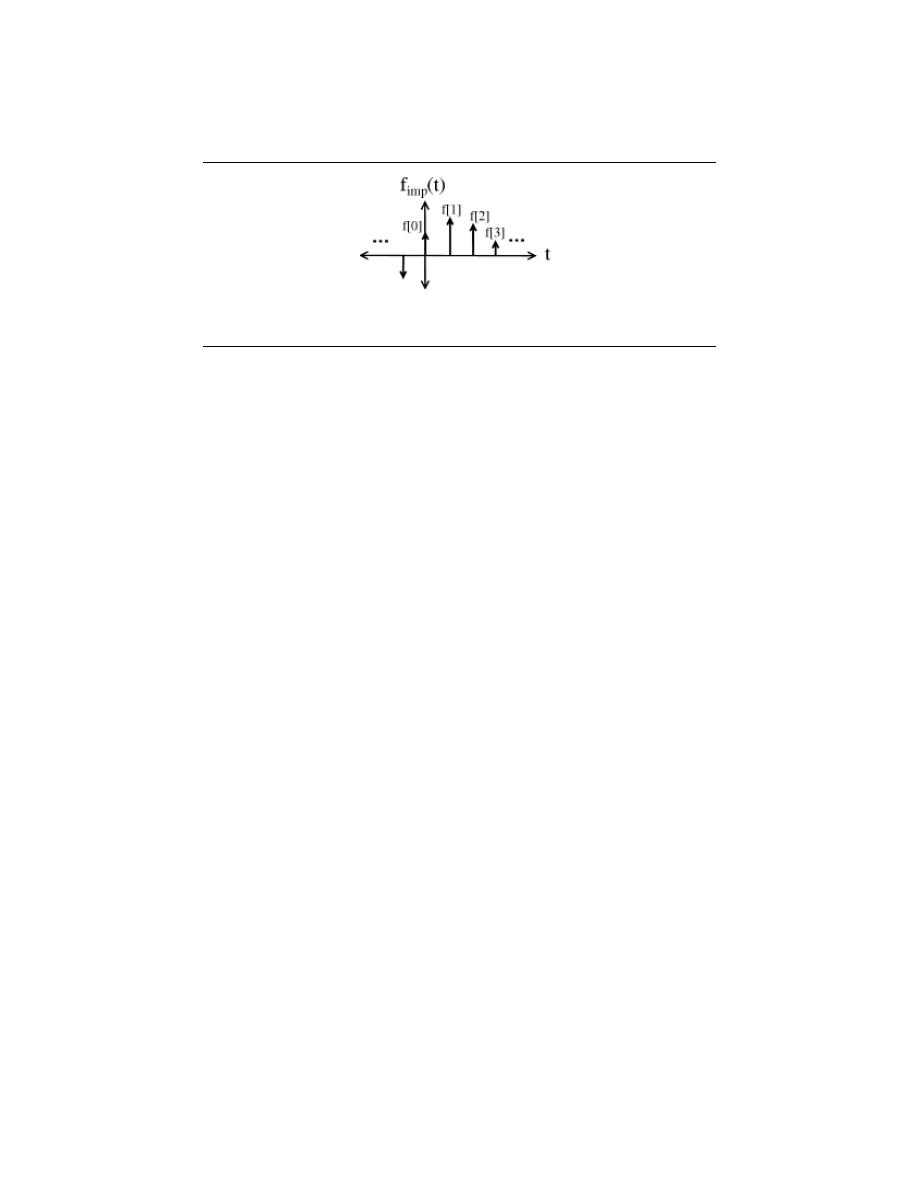

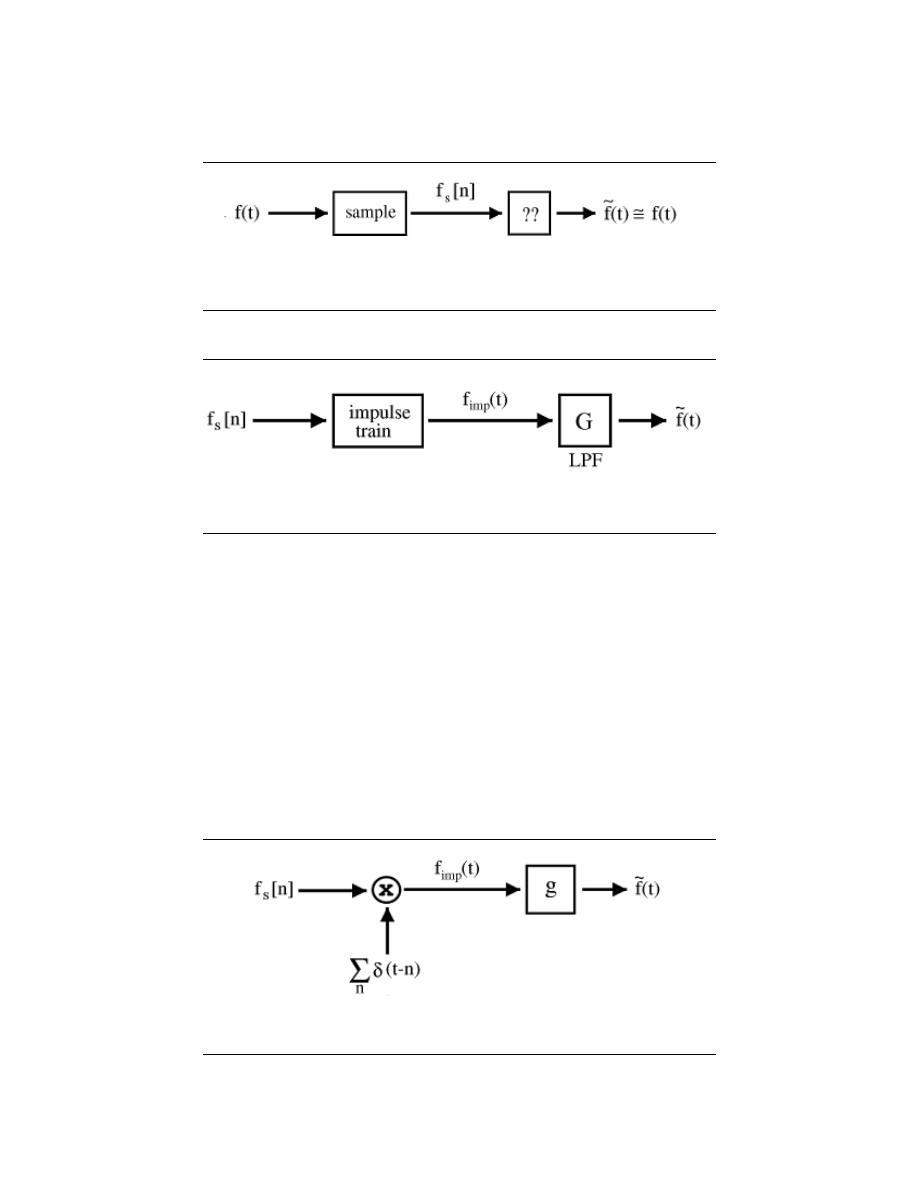

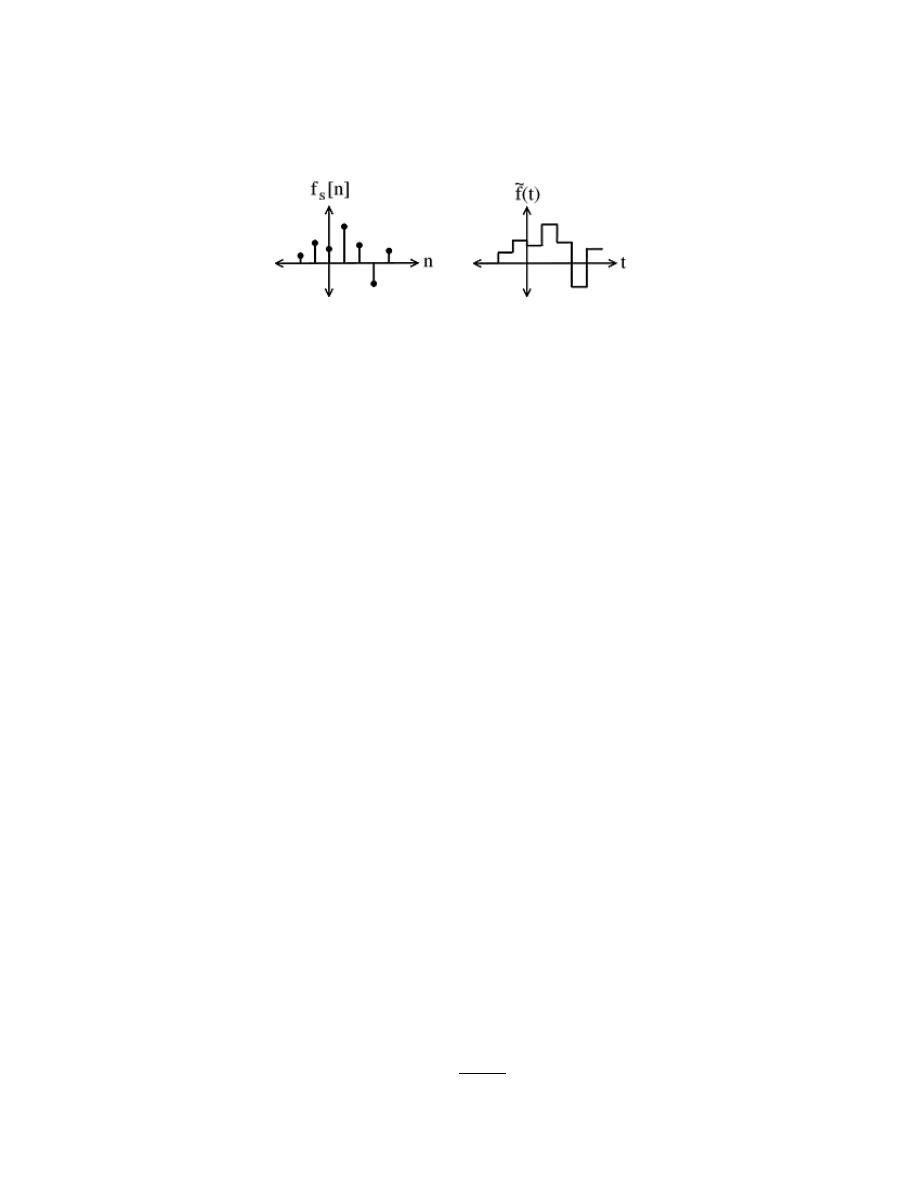

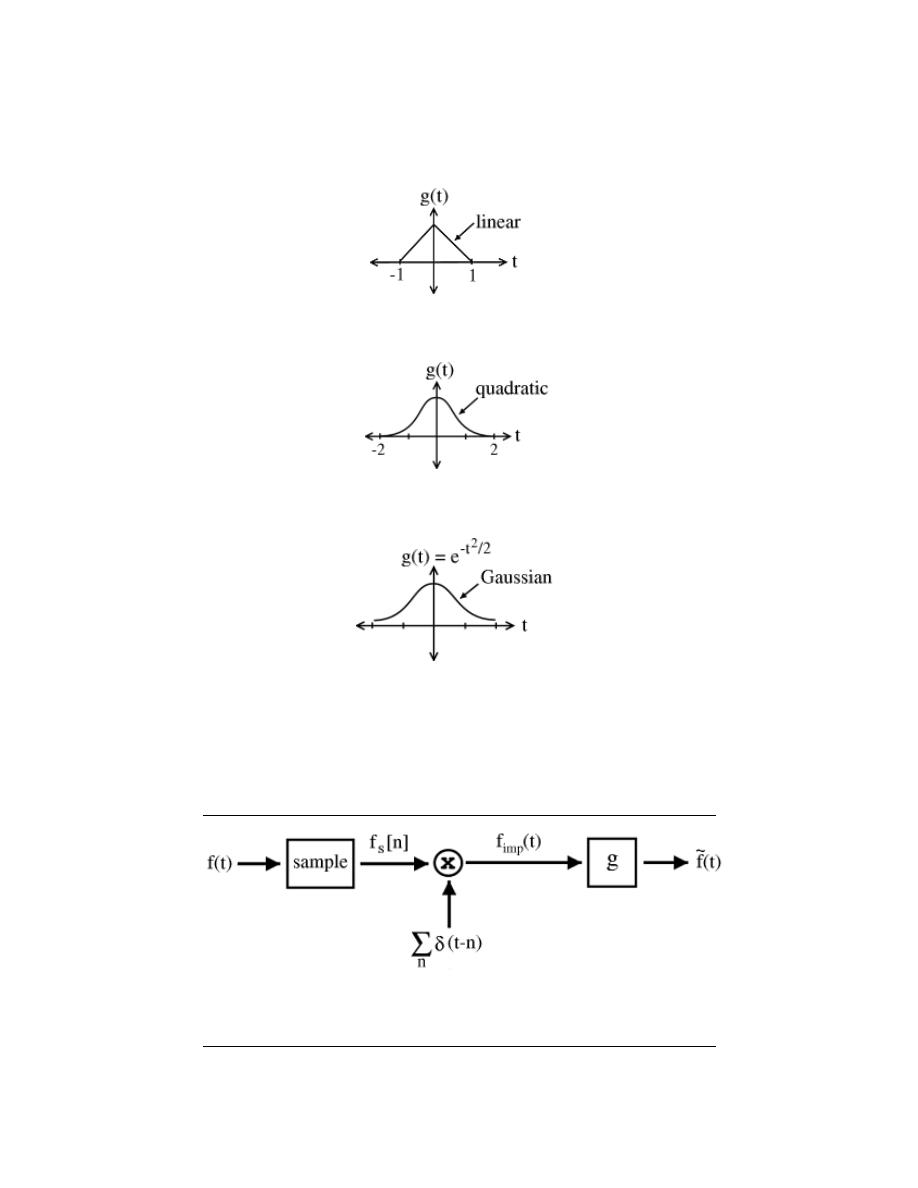

3.8 The Impulse Function

In engineering, we often deal with the idea of an action occuring at a point. Whether

it be a force at a point in space or a signal at a point in time, it becomes worth while to

develop some way of quantitatively defining this. This leads us to the idea of a unit impulse,

probably the second most important function, next to the complex exponential, in systems

and signals course.

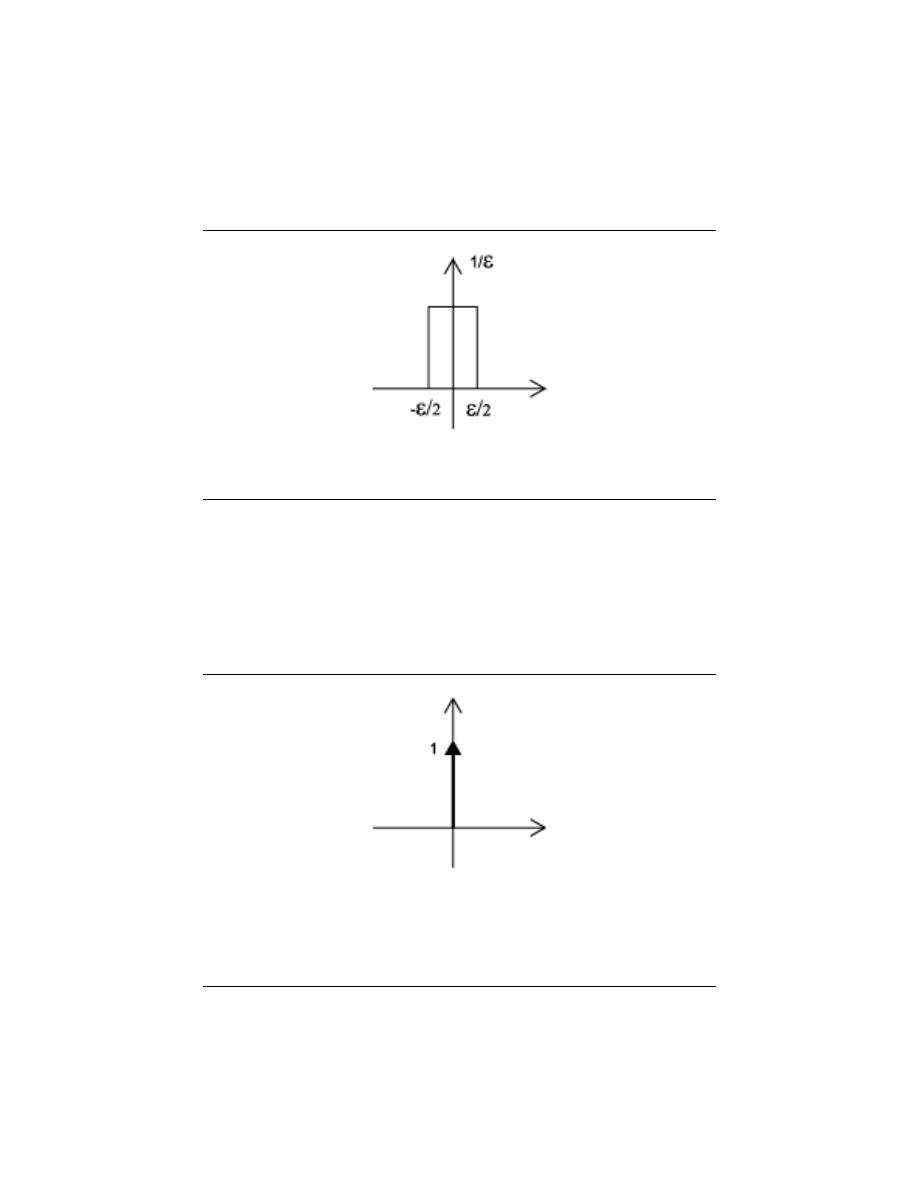

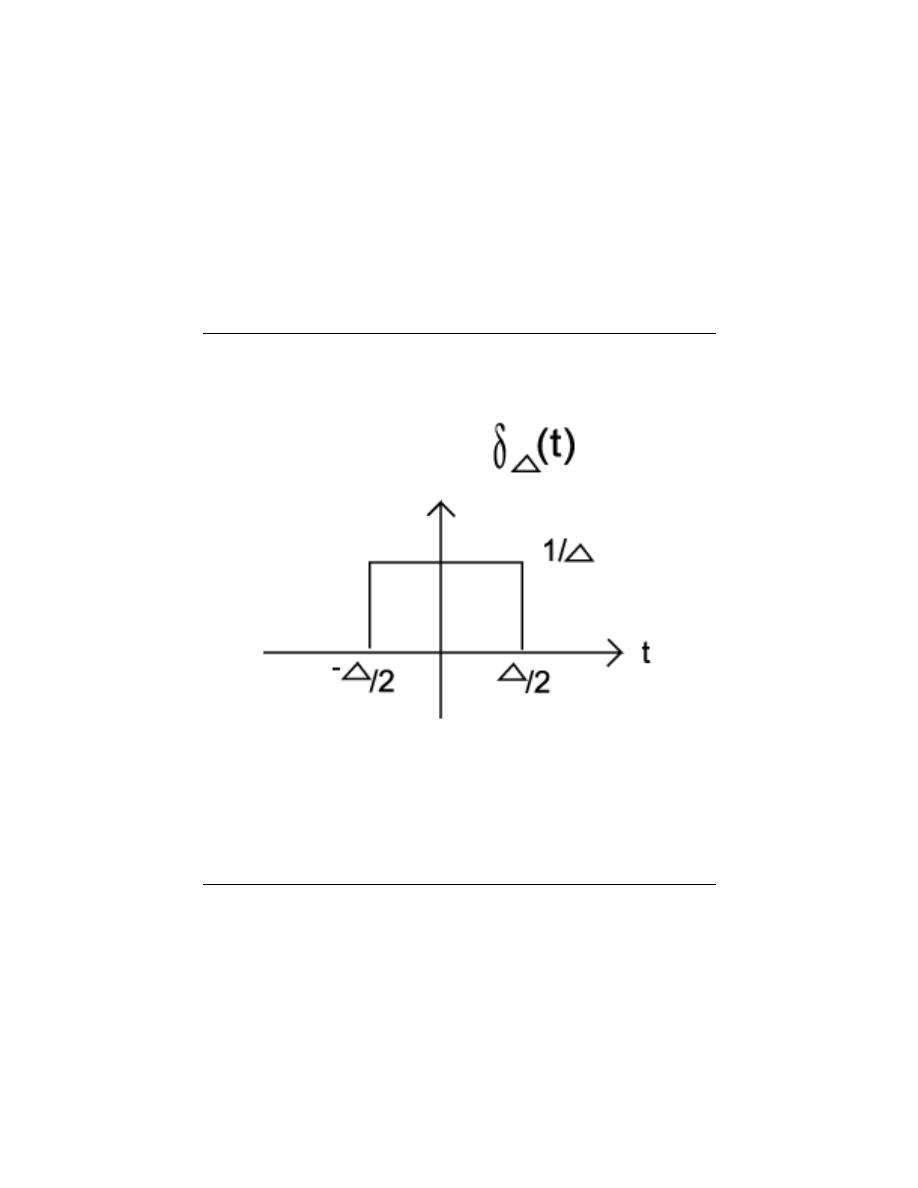

2.8.1 Dirac Delta Function

The Dirac Delta function , often referred to as the unit impulse or delta function, is the

function that defines the idea of a unit impulse. This function is one that is infinitesimally

narrow, infinitely tall, yet integrates to unity , one (see Equation 2.41 below). Perhaps the

simplest way to visualize this is as a rectangular pulse from a −

2

to a +

2

with a height of

1

. As we take the limit of this, lim

→0

0, we see that the width tends to zero and the height

tends to infinity as the total area remains constant at one. The impulse function is often

written as δ (t).

Z

∞

−∞

δ (t) dt = 1

(2.41)

38

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

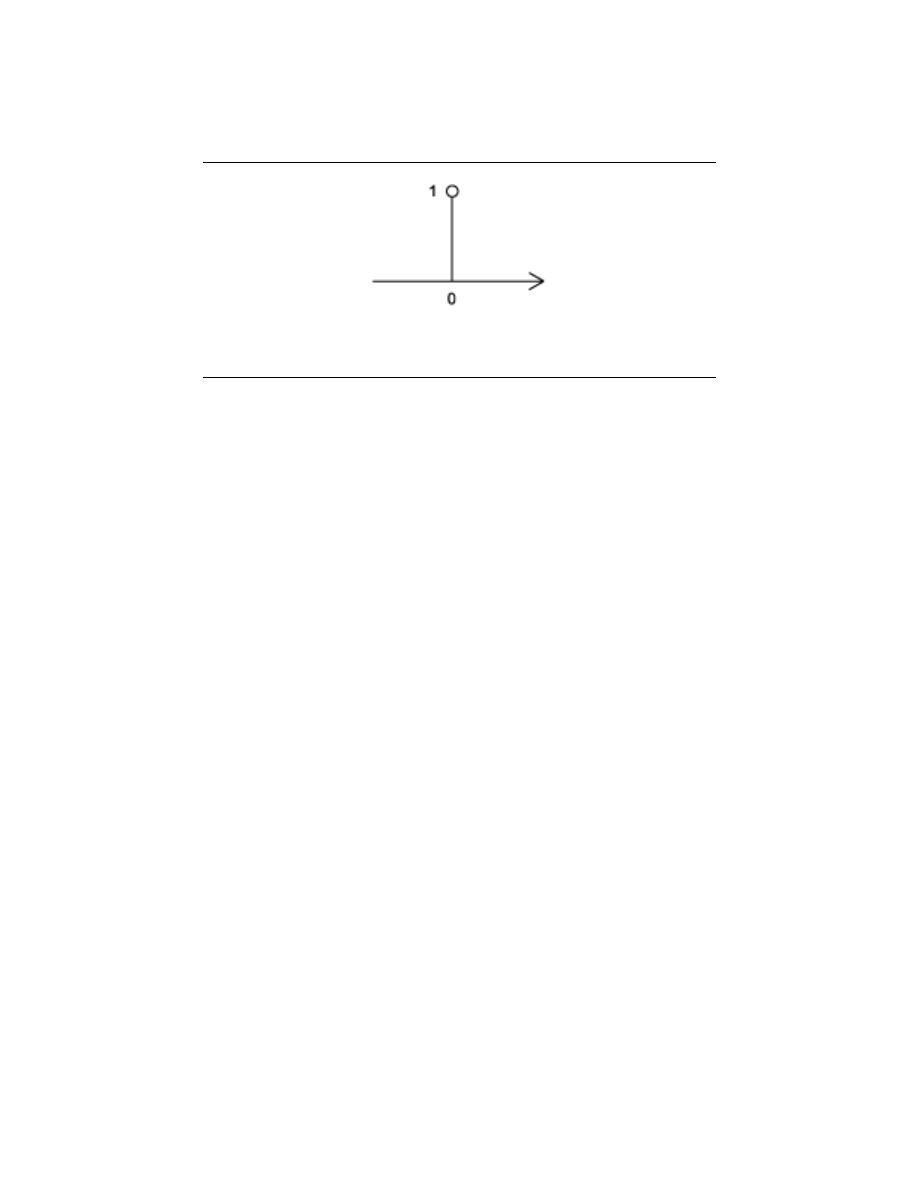

Figure 2.34:

This is one way to visualize the Dirac Delta Function.

Figure 2.35:

Since it is quite difficult to draw something that is infinitely tall, we

represent the Dirac with an arrow centered at the point it is applied. If we wish to scale

it, we may write the value it is scaled by next to the point of the arrow. This is a unit

impulse (no scaling).

39

2.8.1.1 The Sifting Property of the Impulse

The first step to understanding what this unit impulse function gives us is to examine what

happens when we multiply another function by it.

f (t) δ (t) = f (0) δ (t)

(2.42)

Since the impulse function is zero everywhere except the origin, we essentially just ”pick

off” the value of the function we are multiplying by evaluated at zero.

At first glance this may not appear to give use much, since we already know that the

impulse evaluated at zero is infinity, and anyhting times infinity is infinity. However, what

happens if we integrate this?

Sifting Property

R

∞

−∞

f (t) δ (t) dt

=

R

∞

−∞

f (0) δ (t) dt

=

f (0)

R

∞

−∞

δ (t) dt

=

f (0)

(2.43)

It quickly becomes apparent that what we end up with is simply the function evaluated at

zero. Had we used δ (t − T ) instead of δ (t), we could have ”sifted out” f (T ). This is what

we call the Sifting Property of the Dirac function, which is often used to define the unit

impulse.

The Sifting Property is very useful in developing the idea of convolution which is one

of the fundamental principles of signal processing. By using convolution and the sifting

property we can represent an approximation of any system’s output if we know the system’s

impulse response and input. Click on the convolution link above for more information on

this.

2.8.1.2 Other Impulse Properties

Below we will briefly list a few of the other properties of the unit impulse without going into

detail of their proofs - we will leave that up to you to verify as most are straightforward.

Note that these properties hold for continuous and discrete time.

Unit Impulse Properties

• - δ (αt) =

1

|α|

δ (t)

• - δ (t) = δ (−t)

• - δ (t) =

d

dt

u (t), where u (t) is the unit step.

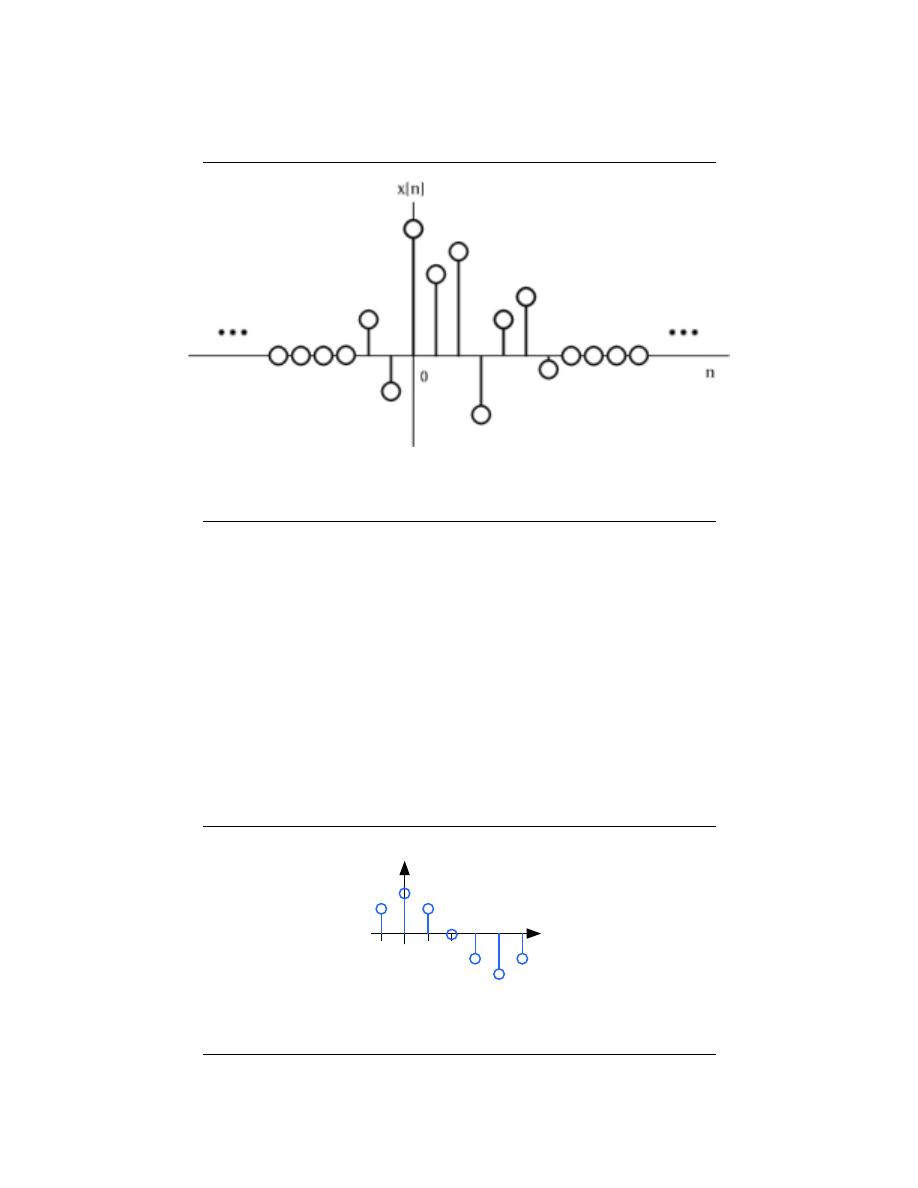

2.8.2 Discrete-Time Impulse (Unit Sample)

The extension of the Unit Impulse Function to discrete-time becomes quite trivial. All we

really need to realize is that integration in continuous-time equates to summation in discrete-

time. Therefore, we are looking for a signal that sums to zero and is zero everywhere except

at zero.

Discrete-Time Impulse

40

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

Figure 2.36: The graphical representation of the discrete-time impulse function

δ [n] =

1 if n = 0

0 otherwise

(2.44)

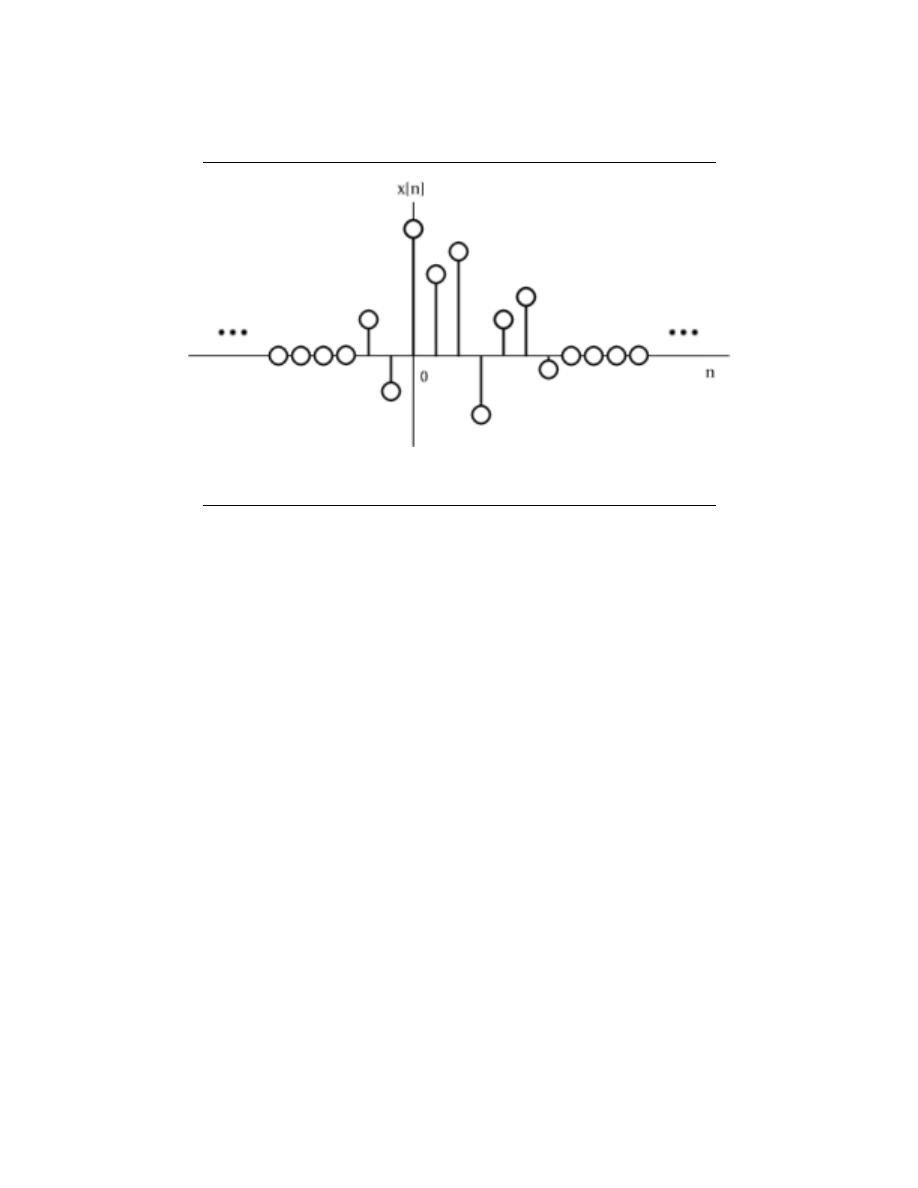

Looking at the discrete-time plot of any discrete signal one can notice that all discrete

signals are composed of a set of scaled, time-shifted unit samples. If we let the value of a

sequence at each integer k be denoted by s [k] and the unit sample delayed that occurs at k

to be written as δ [n − k], we can write any signal as the sum of delayed unit samples that

are scaled by the signal value, or weighted coefficients.

s [n] =

∞

X

k=−∞

(s [k] δ [n − k])

(2.45)

This decomposition is strictly a property of discrete-time signals and proves to be a very

useful property.

note:

Through the above reasoning, we have formed Equation 2.45, which is the

fundamental concept of discrete-time convolution.

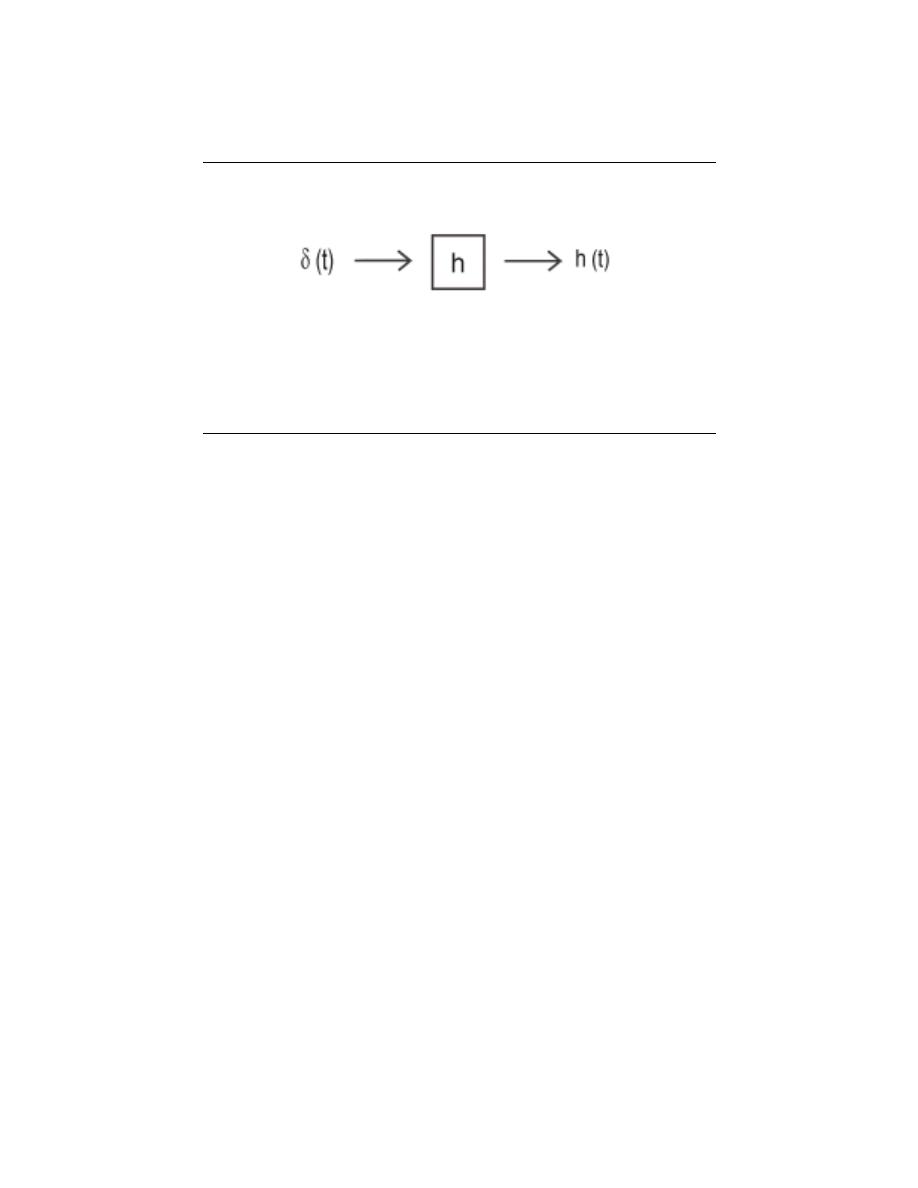

2.8.3 The Impulse Response

The impulse response is exactly what its name implies - the response of an LTI system,

such as a filter, when the system’s input is the unit impulse (or unit sample). A system

can be completed describe by its impulse response due to the idea mentioned above that

all signals can be represented by a superposition of signals. An impulse response gives an

equivalent description of a system as a transfer fucntion, since they are Laplace Transforms

of each other.

notation:

Most texts use δ (t) and δ [n] to denote the continuous-time and

discrte-time impulse response, respectively.

3.9 BIBO Stability

BIBO stands for bounded input, bounded output. BIBO stable is a condition such that any

bounded input yields a bounded output. This is to say that as long as we input a stable

signal, we are guaranteed to have a stable output.

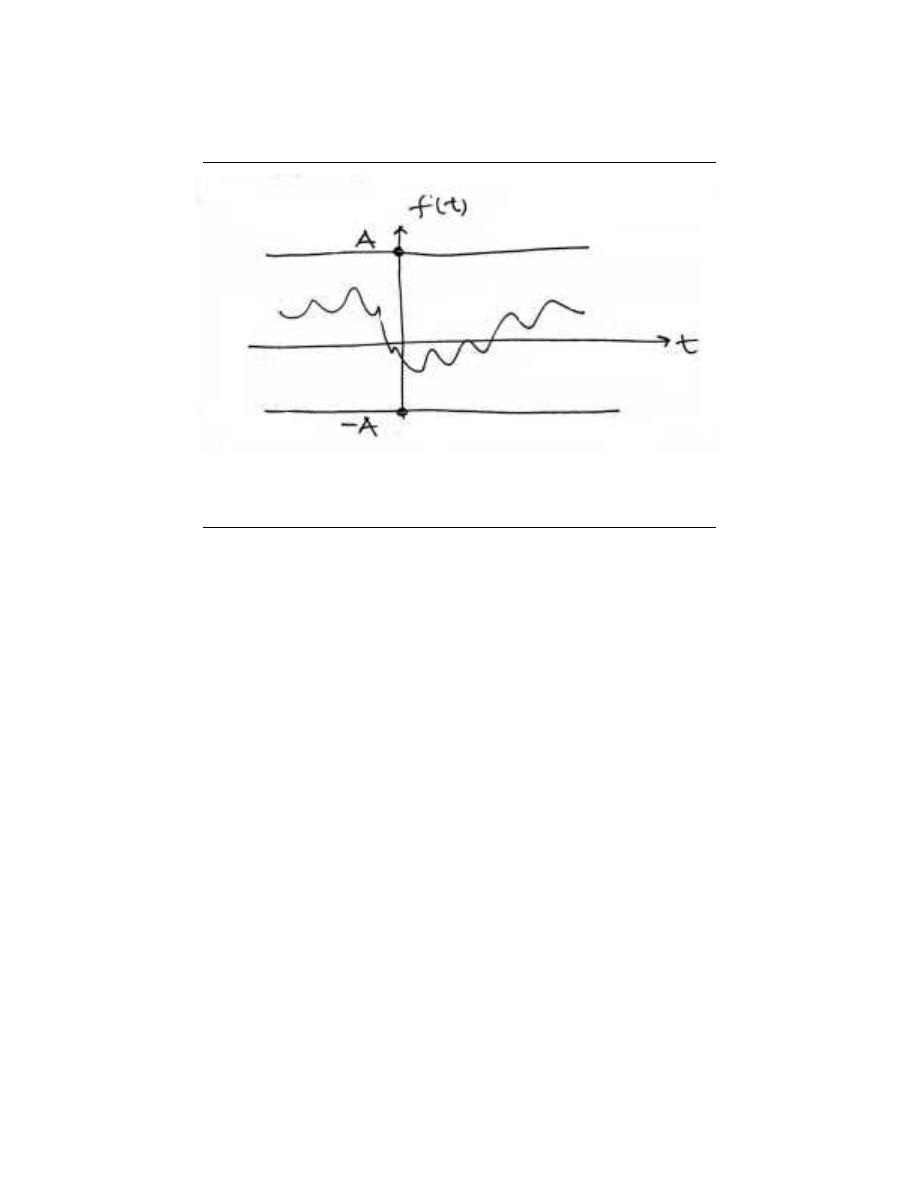

In order to understand this concept, we must first look more closely into exactly what

we mean by bounded. A bounded signal is any signal such that there exists a value such

41

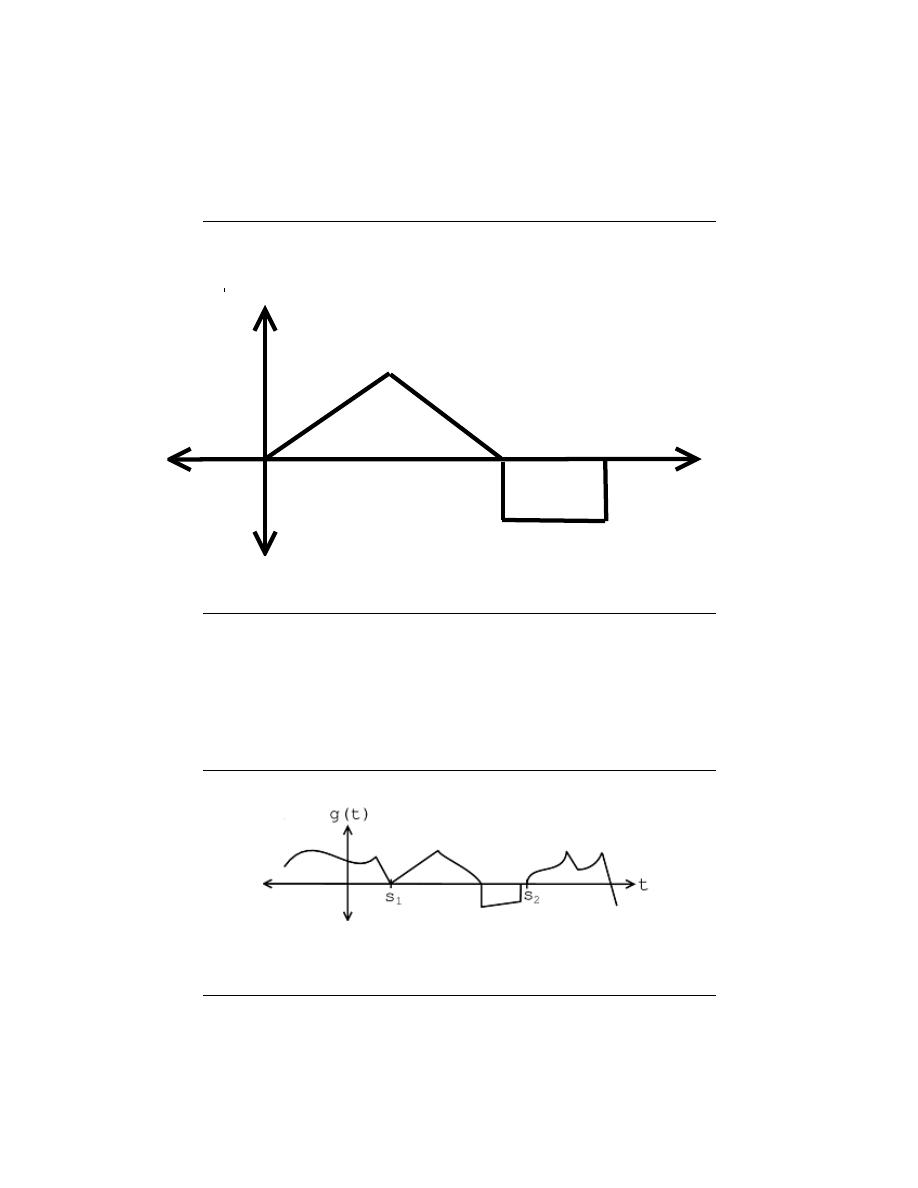

Figure 2.37:

A bounded signal is a signal for which there exists a constant A such that

∀t : |f (t) | < A

that the absolute value of the signal is never greater than some value. Since this value is

arbitrary, what we mean is that at no point can the signal tend to infinity.

Once we have identified what it means for a signal to be bounded, we must turn our

attention to the condition a system must posess in order to guarantee that if any bounded

signal is passed through the system, a bounded signal will arise on the output. It turns out

that a continuous-time LTI system with impulse response h (t) is BIBO stable if and only

if

Continuous-Time Condition for BIBO Stability

Z

∞

−∞

|h (t) |dt < ∞

(2.46)

This is to say that the transfer function is absolutely integrable.

To extend this concept to discrete-time, we make the standard transition from integration

to summation and get that the transfer function, h (n), must be absolutely summable. That

is

Discrete-Time Condition for BIBO Stability

∞

X

n=−∞

(|h (n) |) < ∞

(2.47)

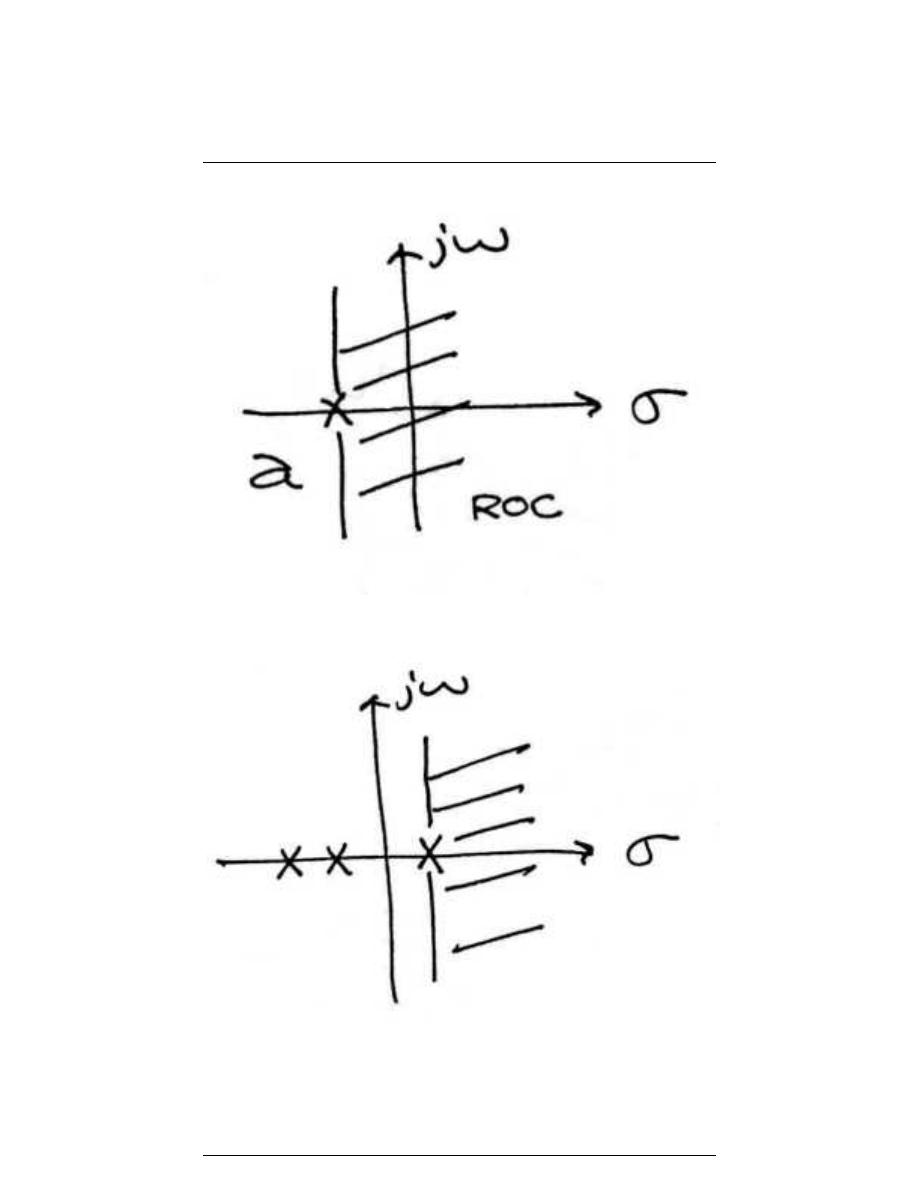

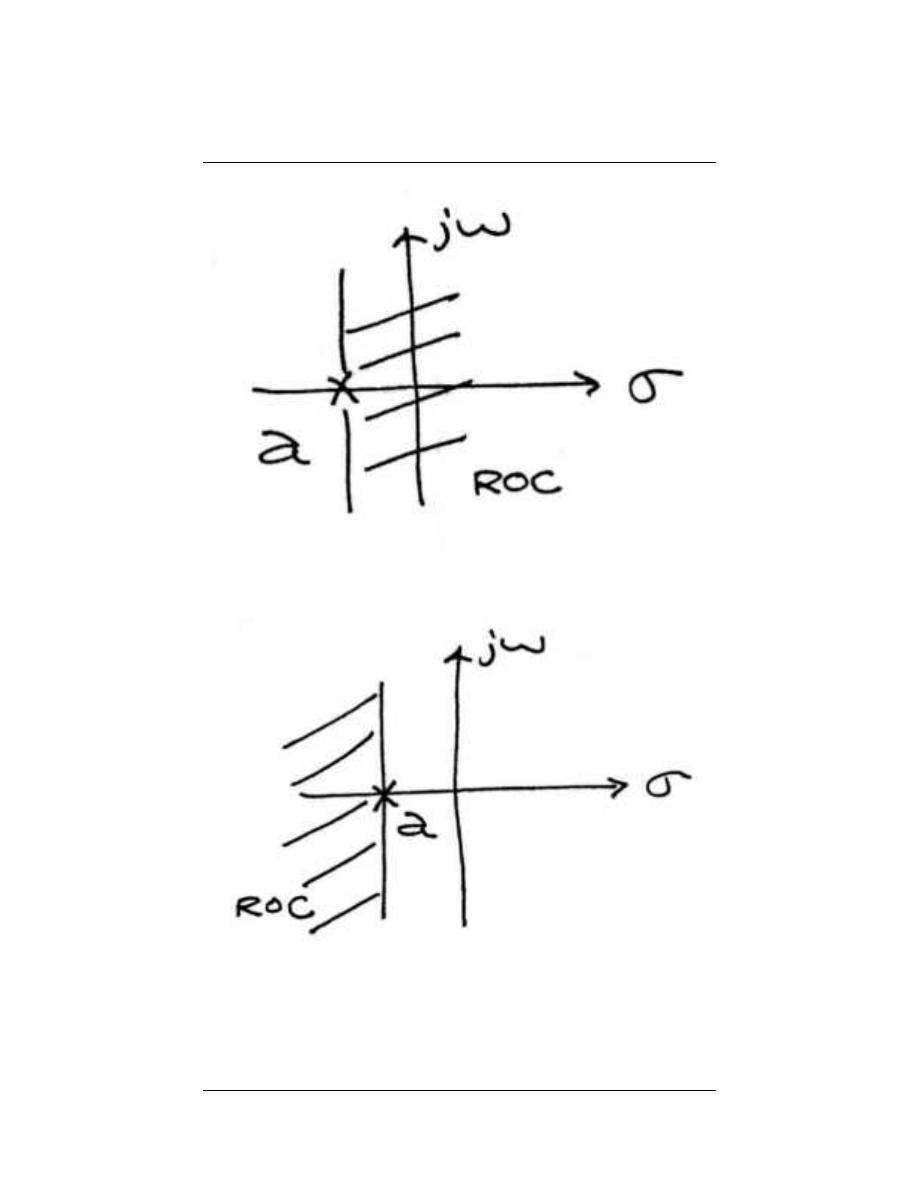

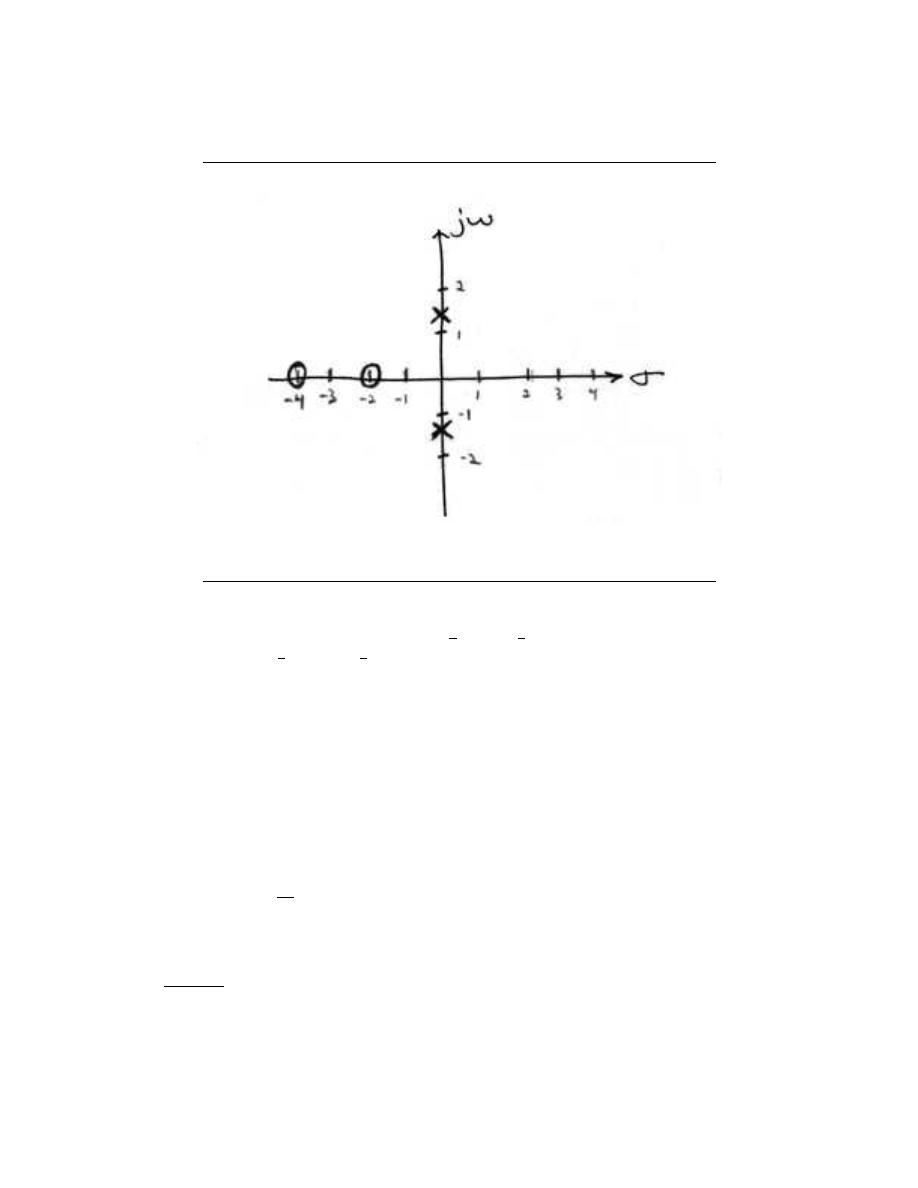

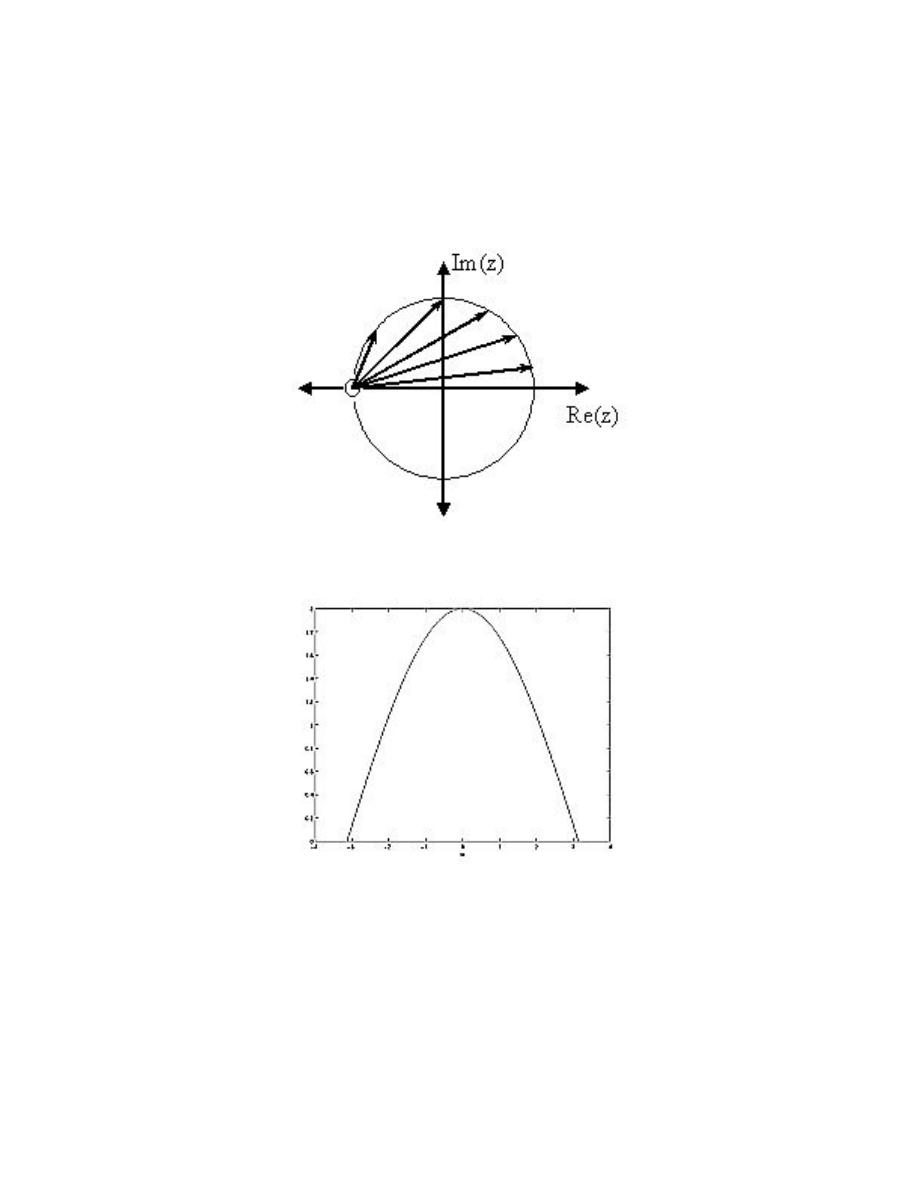

2.9.1 Stability and Laplace

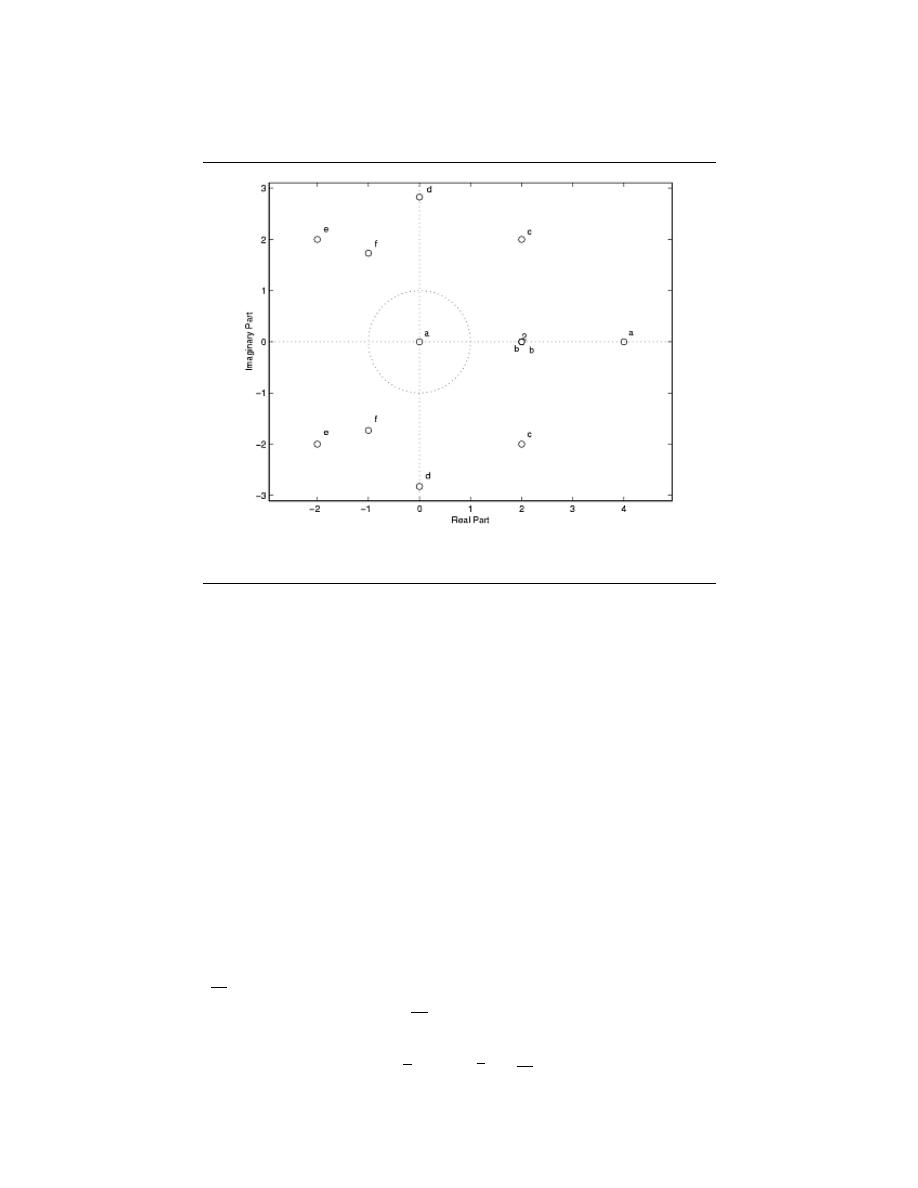

Stability is very easy to infer from the pole-zero plot of a transfer function. The only

condition necessary to demonstrate stability is to show that the jω-axis is in the region of

convergence.

42

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

(a)

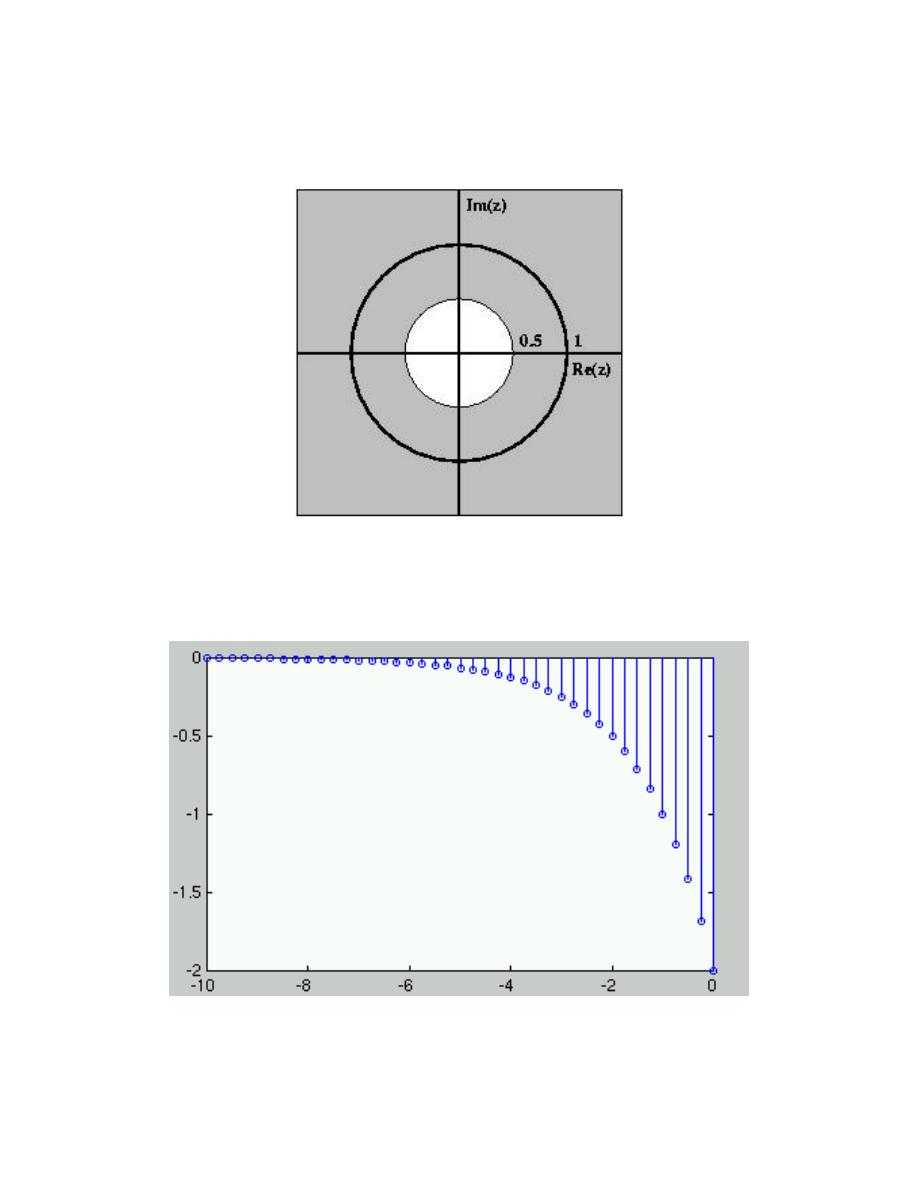

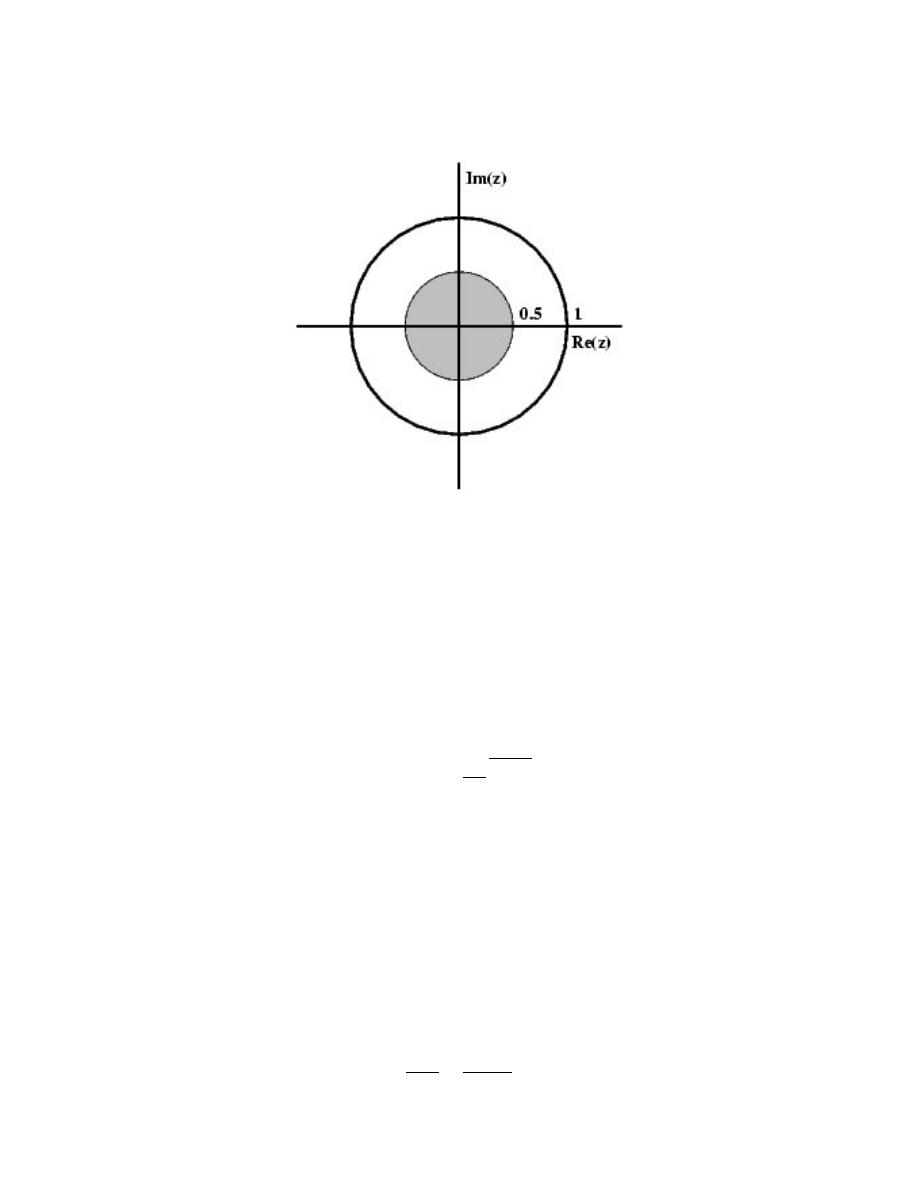

(b)

Figure 2.38:

(a) Example of a pole-zero plot for a stable continuous-time system. (b)

Example of a pole-zero plot for an unstable continuous-time system.

43

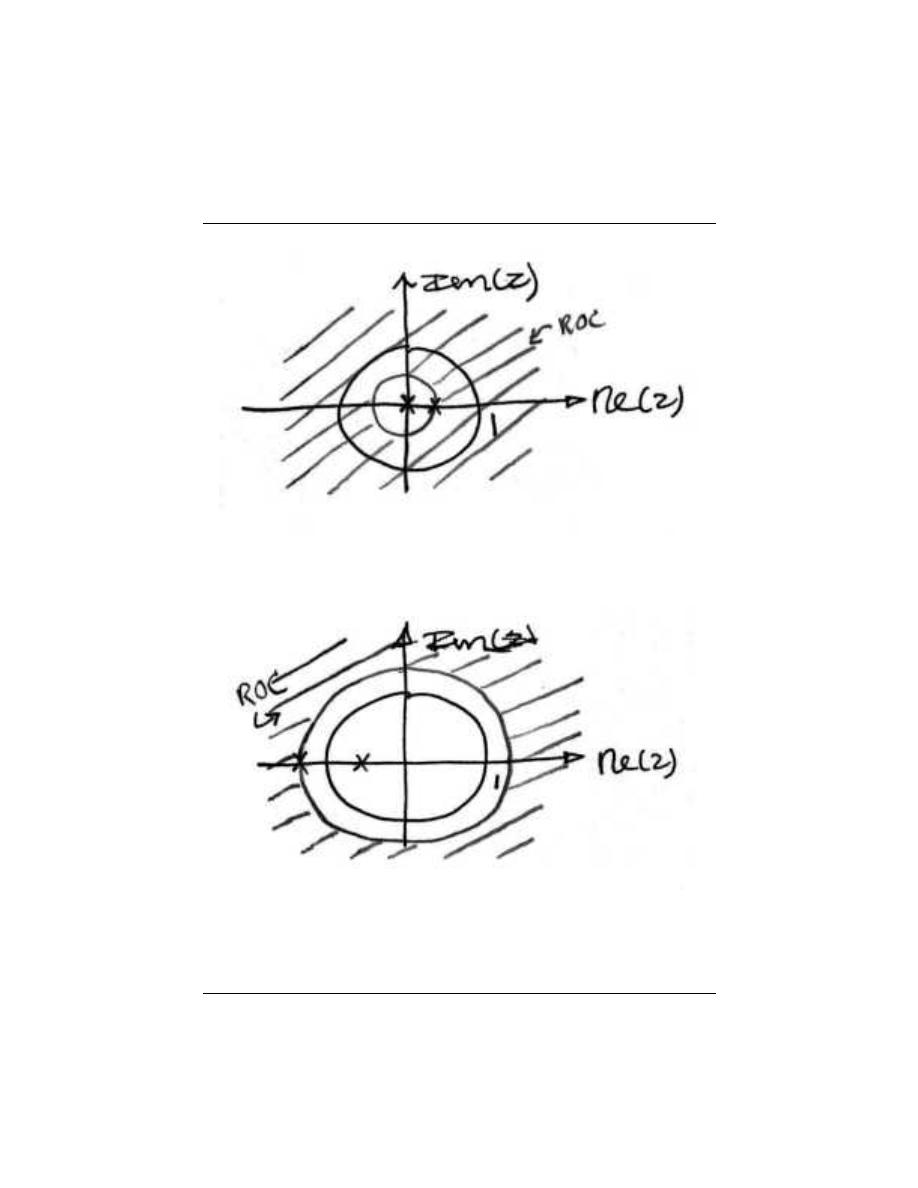

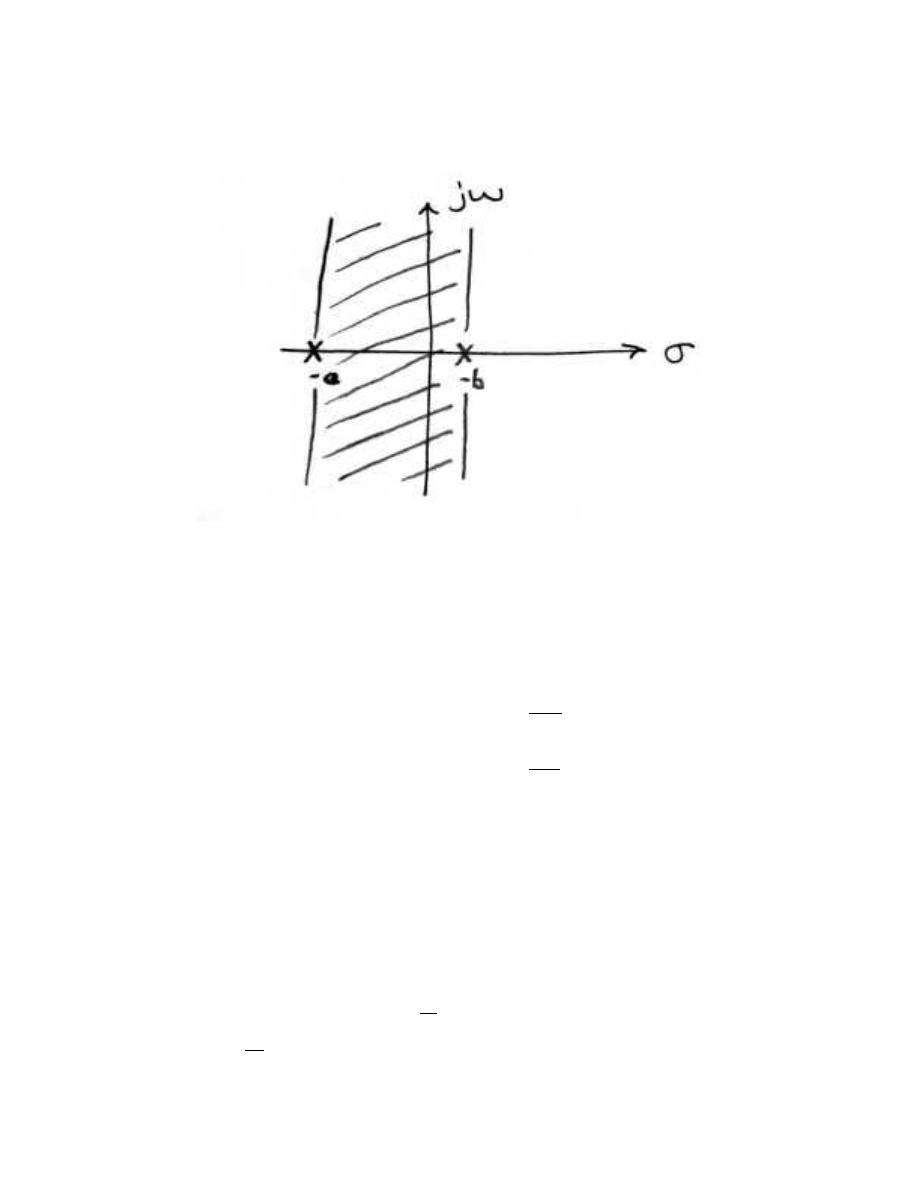

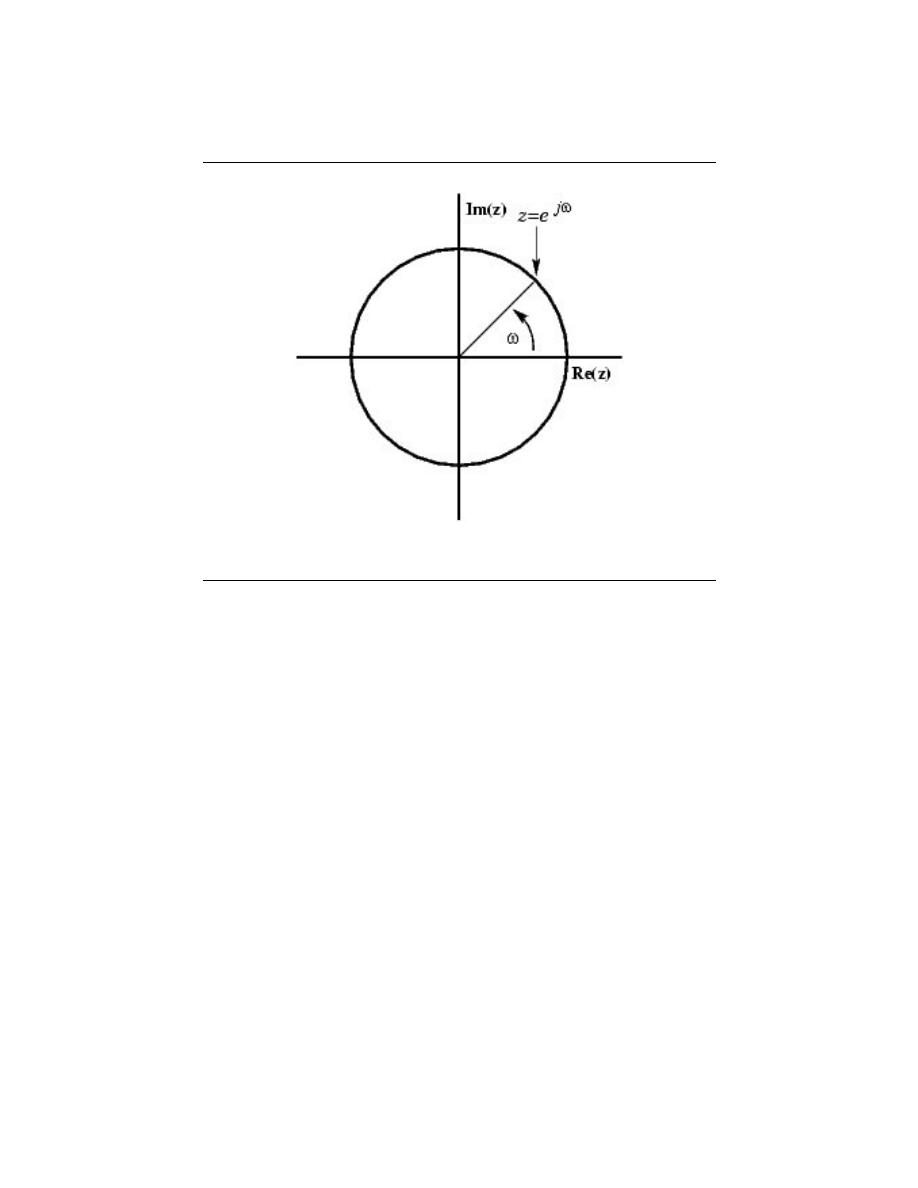

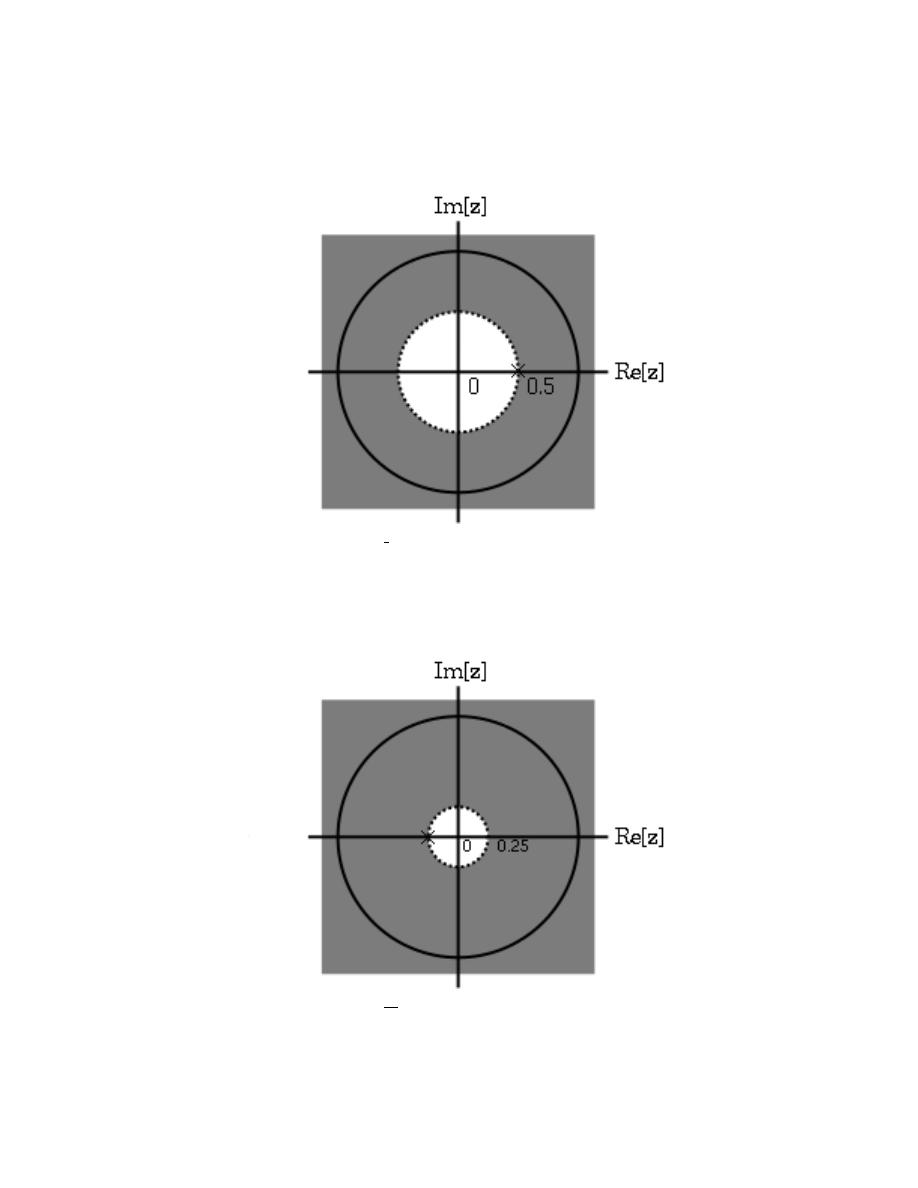

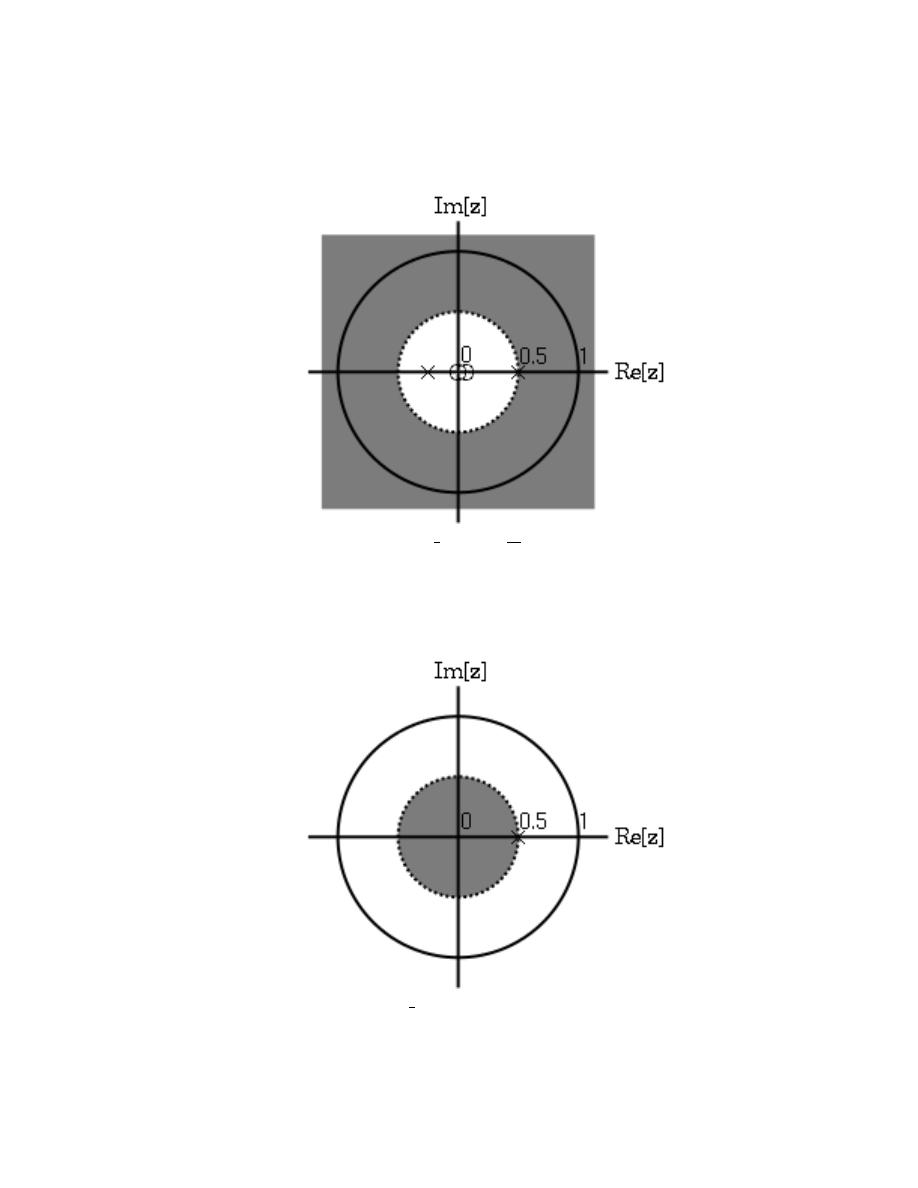

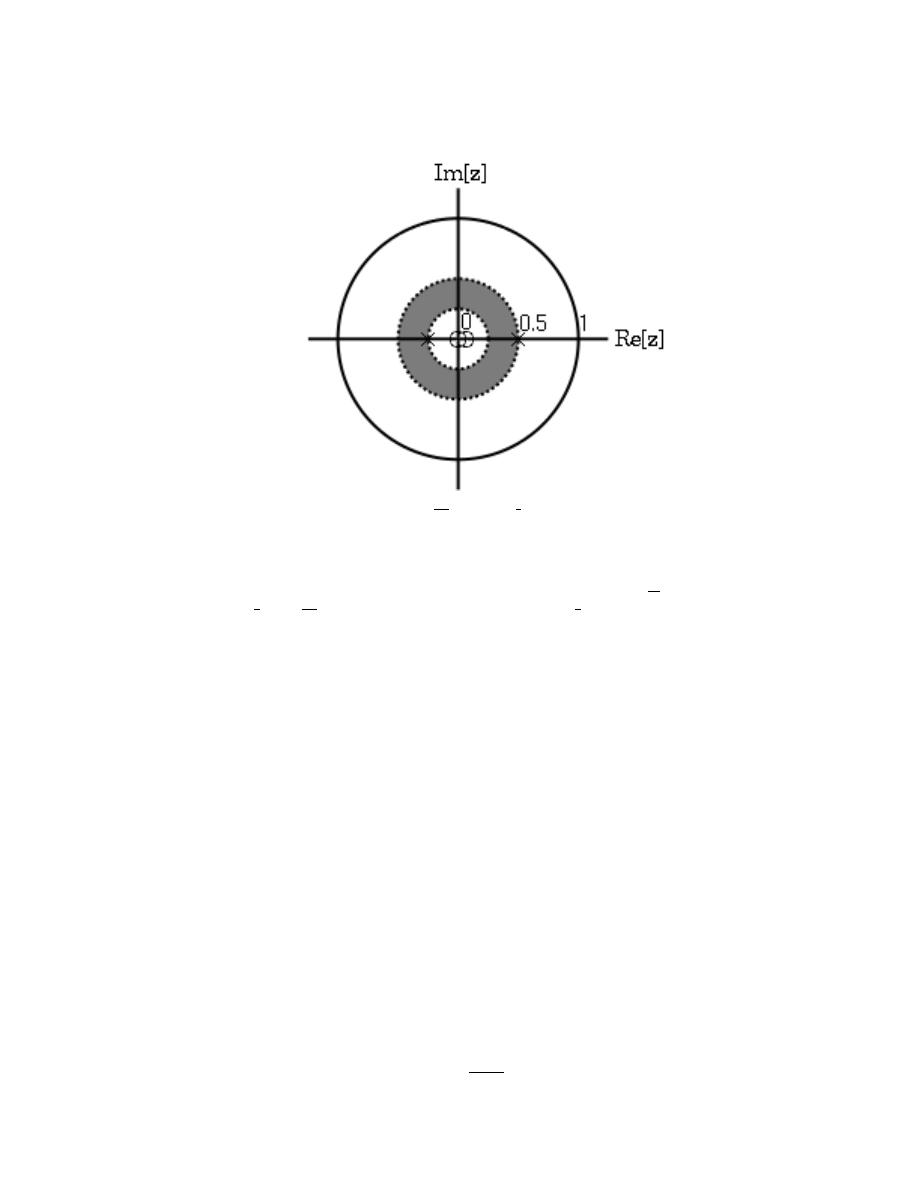

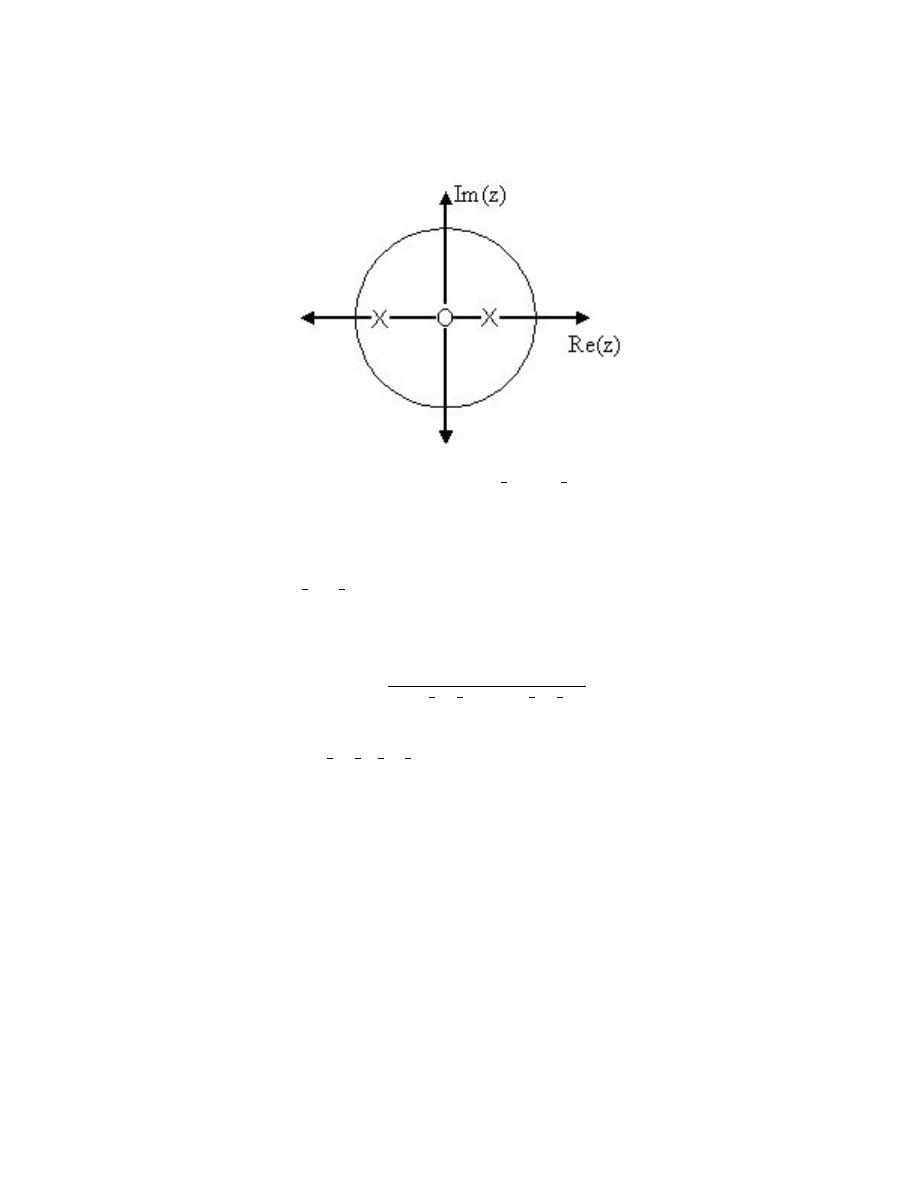

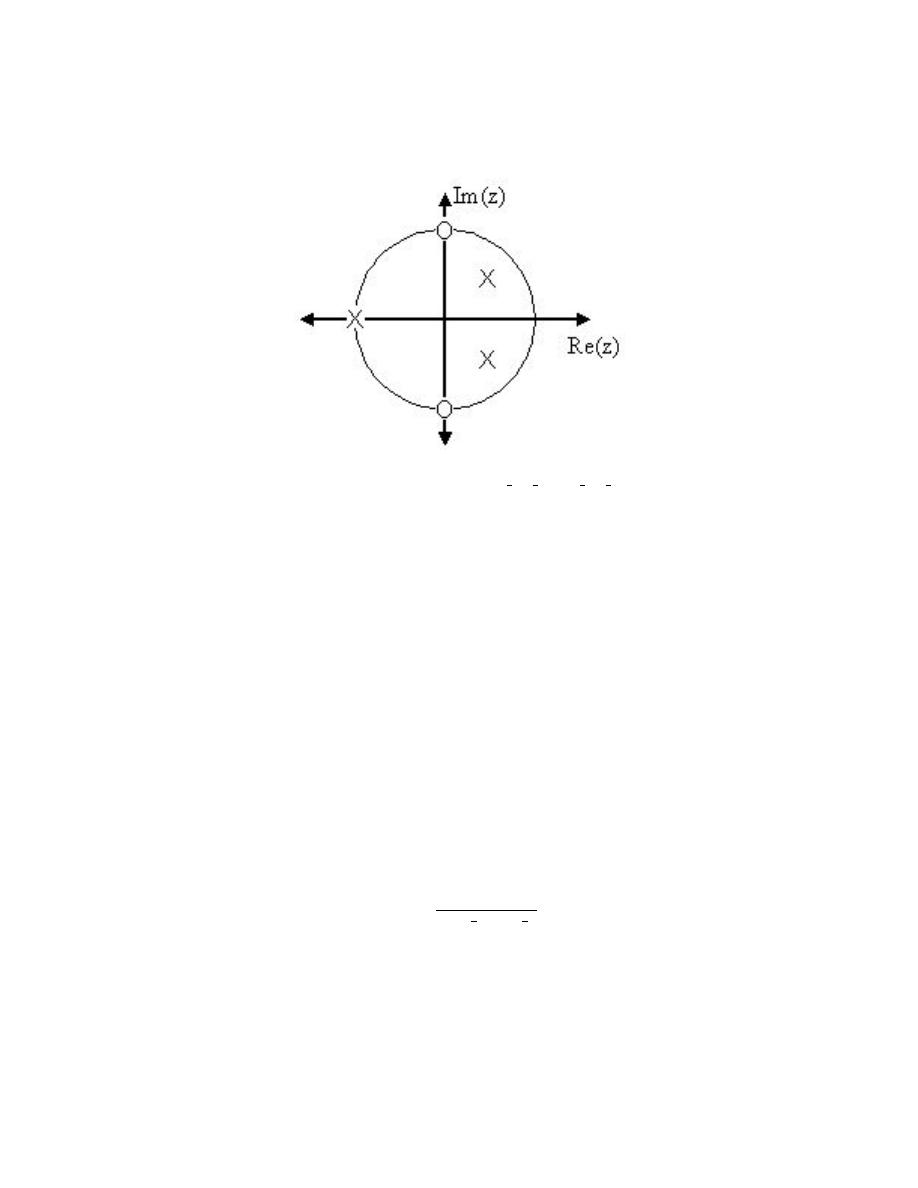

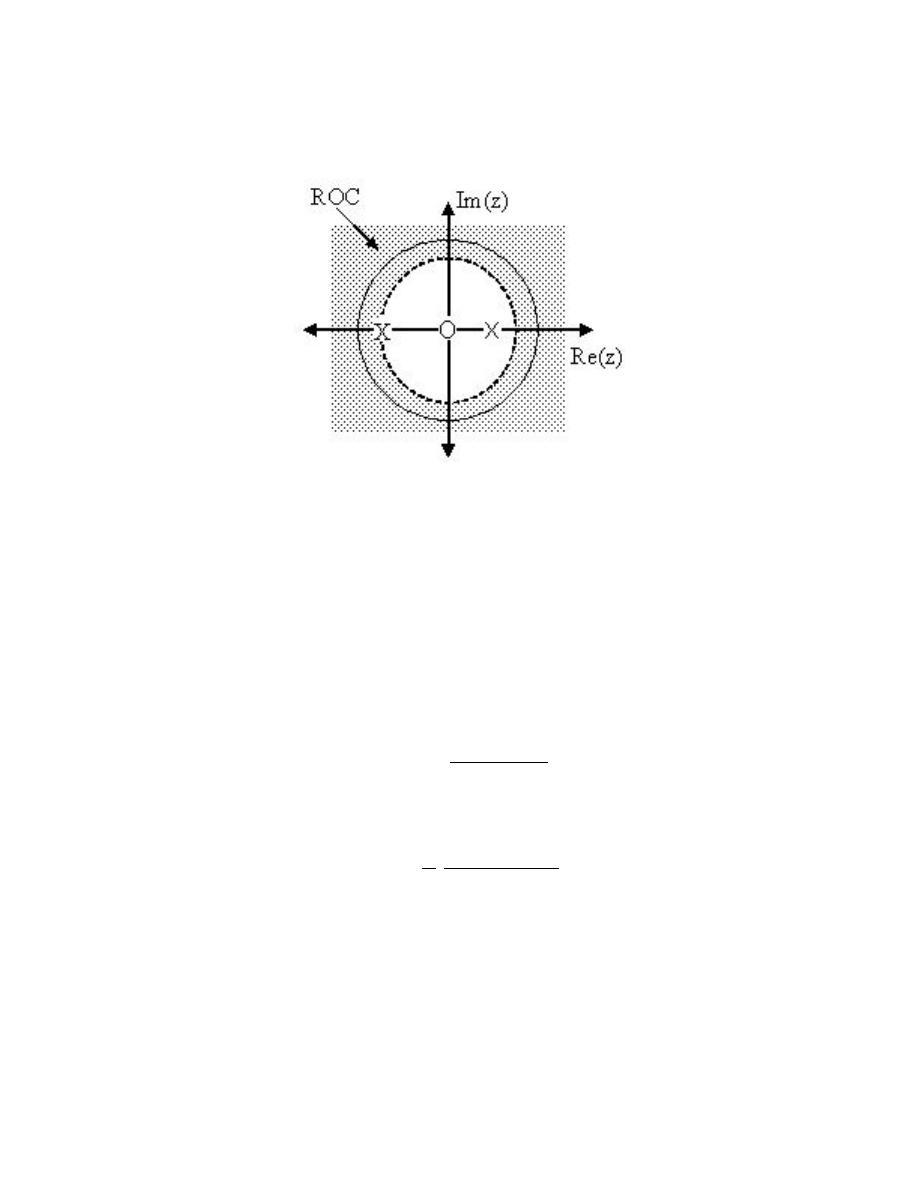

2.9.2 Stability and the Z-Transform

Stability for discrete-time signals in the z-domain is about as easy to demonstrate as it

is for continuous-time signals in the Laplace domain. However, instead of the region of

convergence needing to contain the jω-axis, the ROC must contain the unit circle.

44

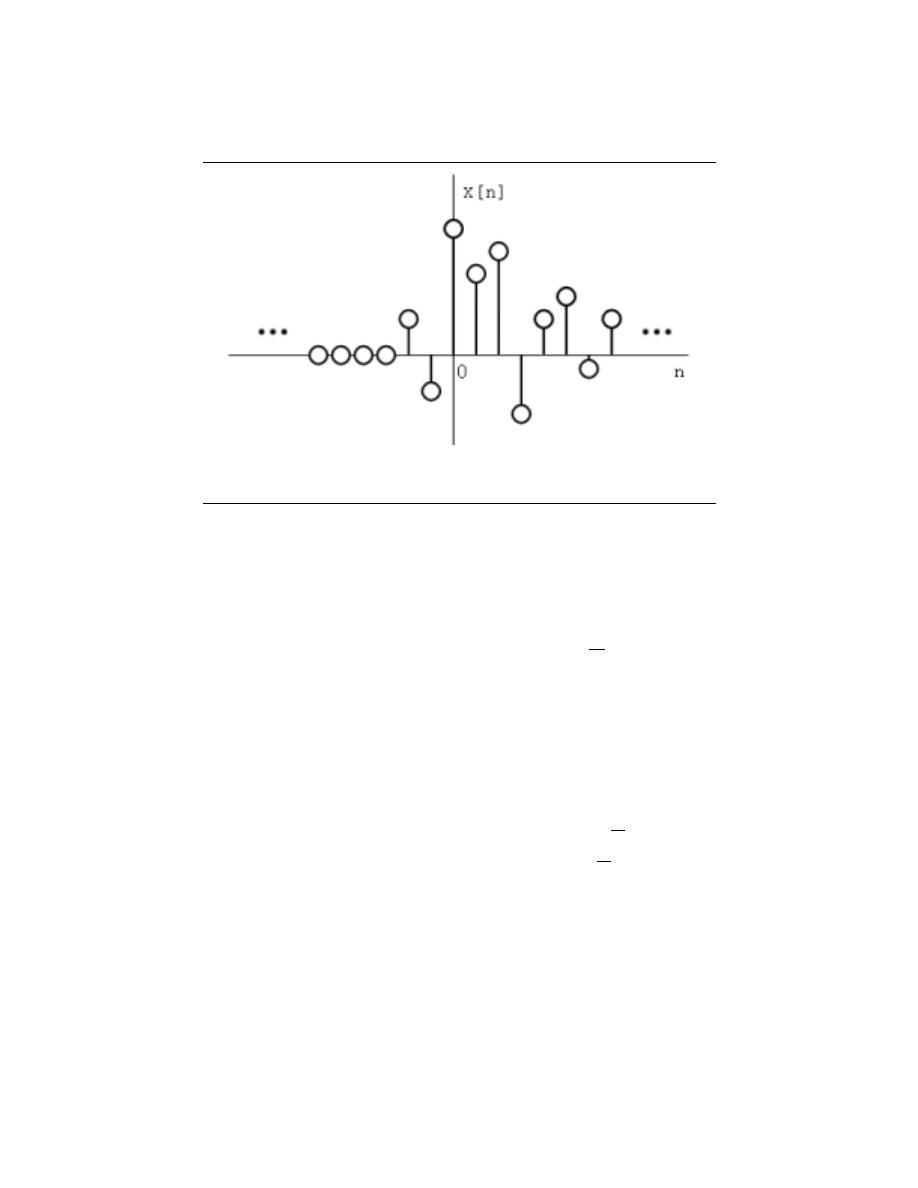

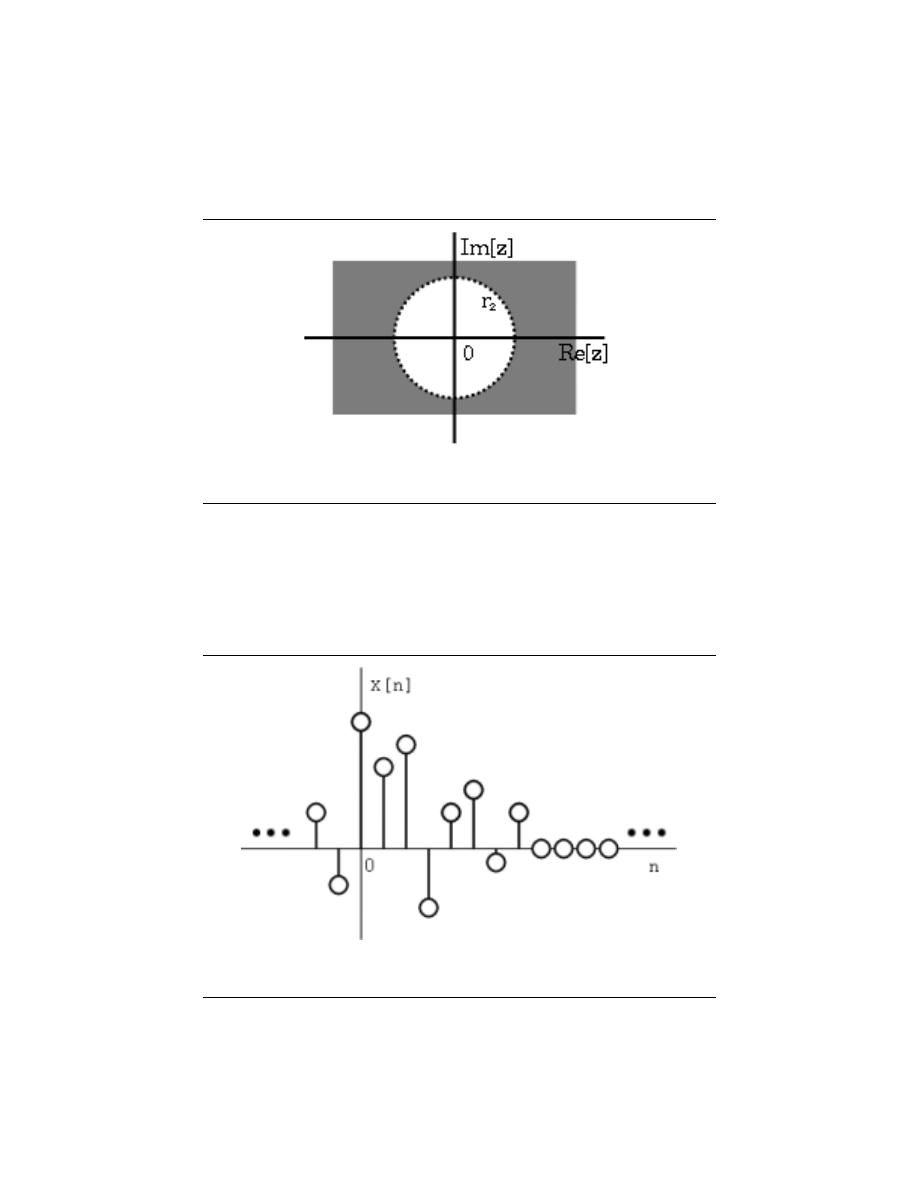

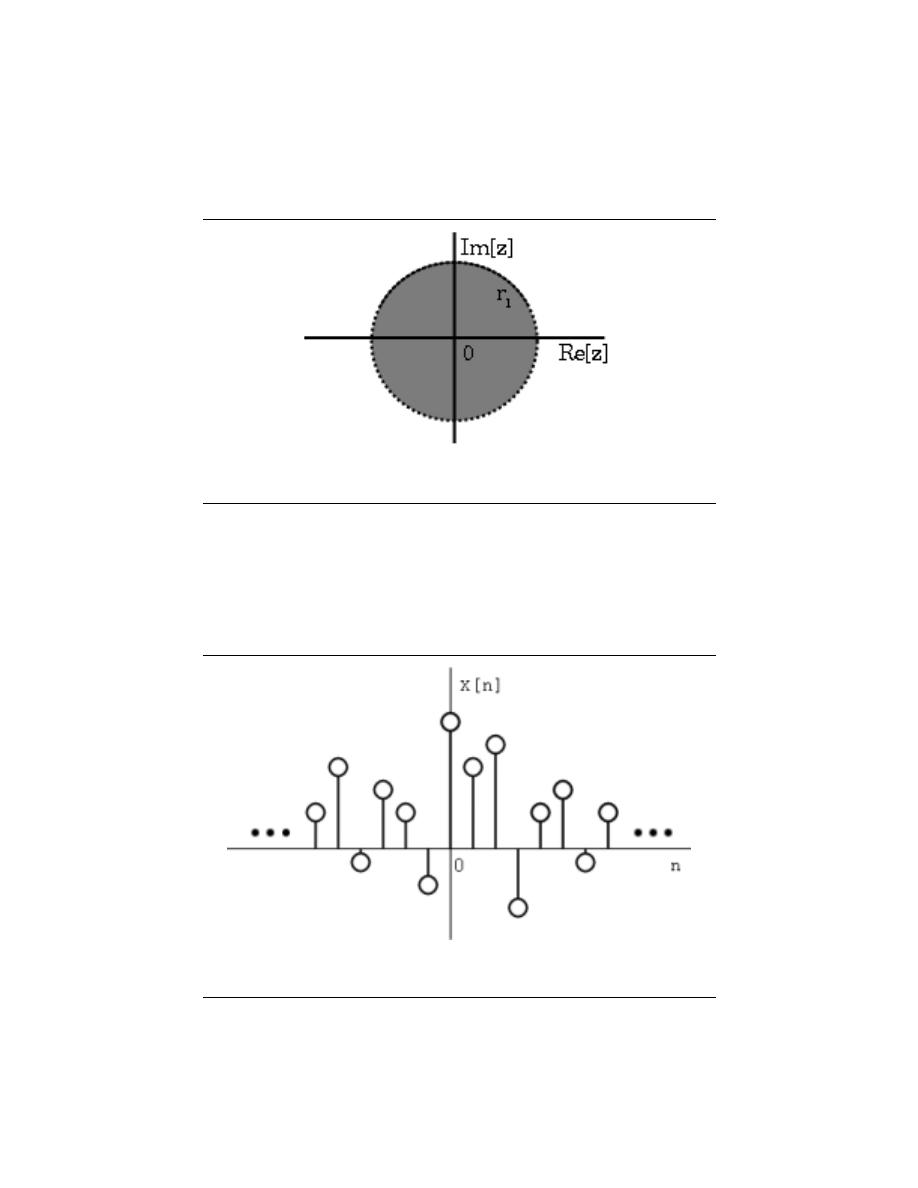

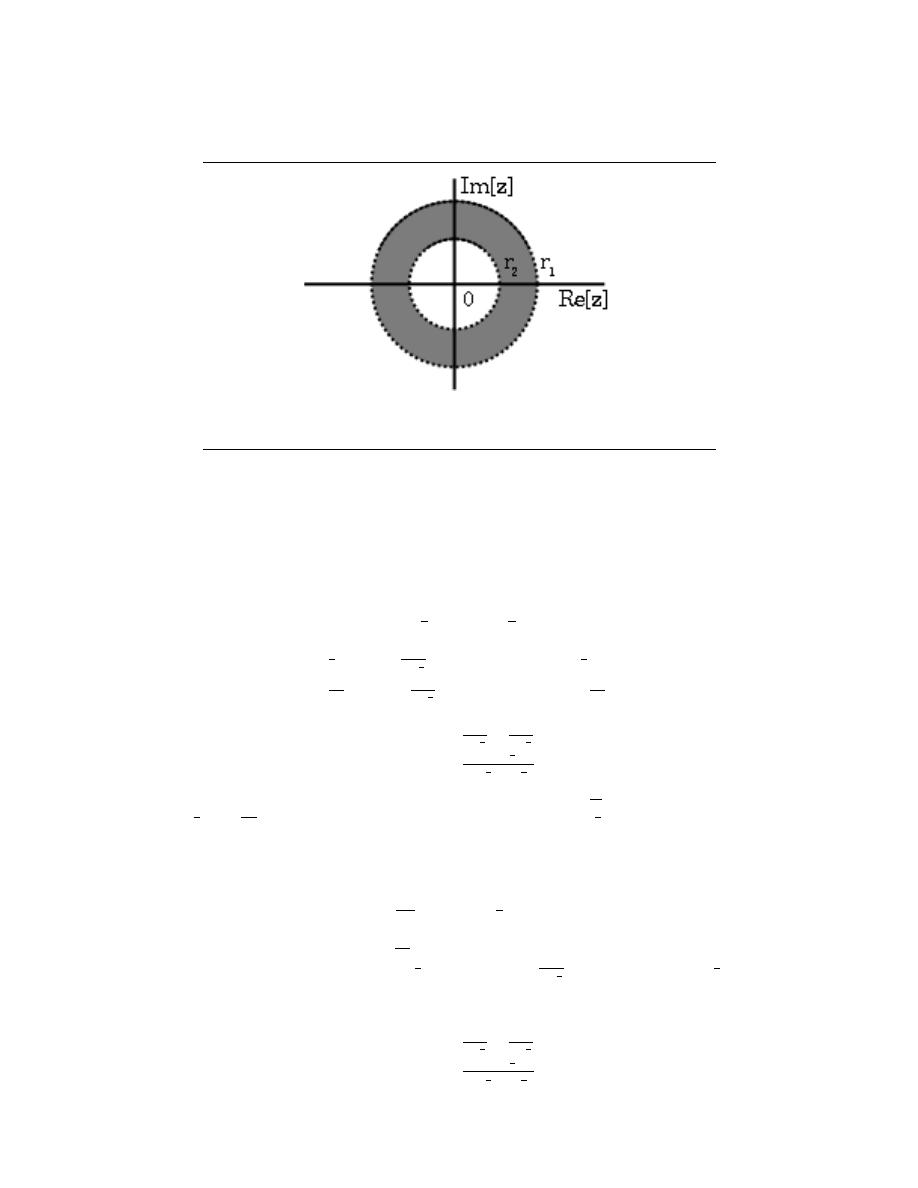

CHAPTER 2. SIGNALS AND SYSTEMS: A FIRST LOOK

(a)

(b)

Figure 2.39:

(a) A stable discrete-time system. (b) An unstable discrete-time system.

Chapter 3

Time-Domain Analysis of CT

Systems

4.1 Systems in the Time-Domain

A discrete-time signal s (n) is delayed by n

0

samples when we write s (n − n

0

), with n

0

> 0.

Choosing n

0

to be negative advances the signal along the integers. As opposed to analog

delays (pg ??), discrete-time delays can only be integer valued. In the frequency domain,

delaying a signal corresponds to a linear phase shift of the signal’s discrete-time Fourier

transform: s (n − n

0

) ↔ e

−(j2πf n

0

)

S e

j2πf

.

Linear discrete-time systems have the superposition property.

Superposition

S (a

1

x

1

(n) + a

2

x

2

(n)) = a

1

S (x

1

(n)) + a

2

S (x

2

(n))

(3.1)

A discrete-time system is called shift-invariant (analogous to time-invariant analog sys-

tems (pg ??)) if delaying the input delays the corresponding output.

Shift-Invariant

If S (x (n)) = y (n) , T henS (x (n − n

0

)) = y (n − n

0

)

(3.2)

We use the term shift-invariant to emphasize that delays can only have integer values in

discrete-time, while in analog signals, delays can be arbitrarily valued.

We want to concentrate on systems that are both linear and shift-invariant. It will

be these that allow us the full power of frequency-domain analysis and implementations.

Because we have no physical constraints in ”constructing” such systems, we need only a

mathematical specification. In analog systems, the differential equation specifies the input-

output relationship in the time-domain. The corresponding discrete-time specification is

the difference equation .

The Difference Equation

y (n) = a

1

y (n − 1) + ... + a

p

y (n − p) + b

0

x (n) + b

1

x (n − 1) + ... + b

q

x (n − q)

(3.3)

Here, the output signal y (n) is related to its past values y (n − l), l = {1, ..., p}, and to the

current and past values of the input signal x (n). The system’s characteristics are determined

by the choices for the number of coefficients p and q and the coefficients’ values {a

1

, ..., a

p

}

and {b

0

, b

1

, ..., b

q

}.

45

46

CHAPTER 3. TIME-DOMAIN ANALYSIS OF CT SYSTEMS

aside:

There is an asymmetry in the coefficients: where is a

0

? This coefficient

would multiply the y (n) term in the difference equation (Equation 3.3). We have

essentially divided the equation by it, which does not change the input-output

relationship. We have thus created the convention that a

0

is always one.

As opposed to differential equations, which only provide an implicit description of a

system (we must somehow solve the differential equation), difference equations provide an

explicit way of computing the output for any input.

We simply express the difference

equation by a program that calculates each output from the previous output values, and

the current and previous inputs.

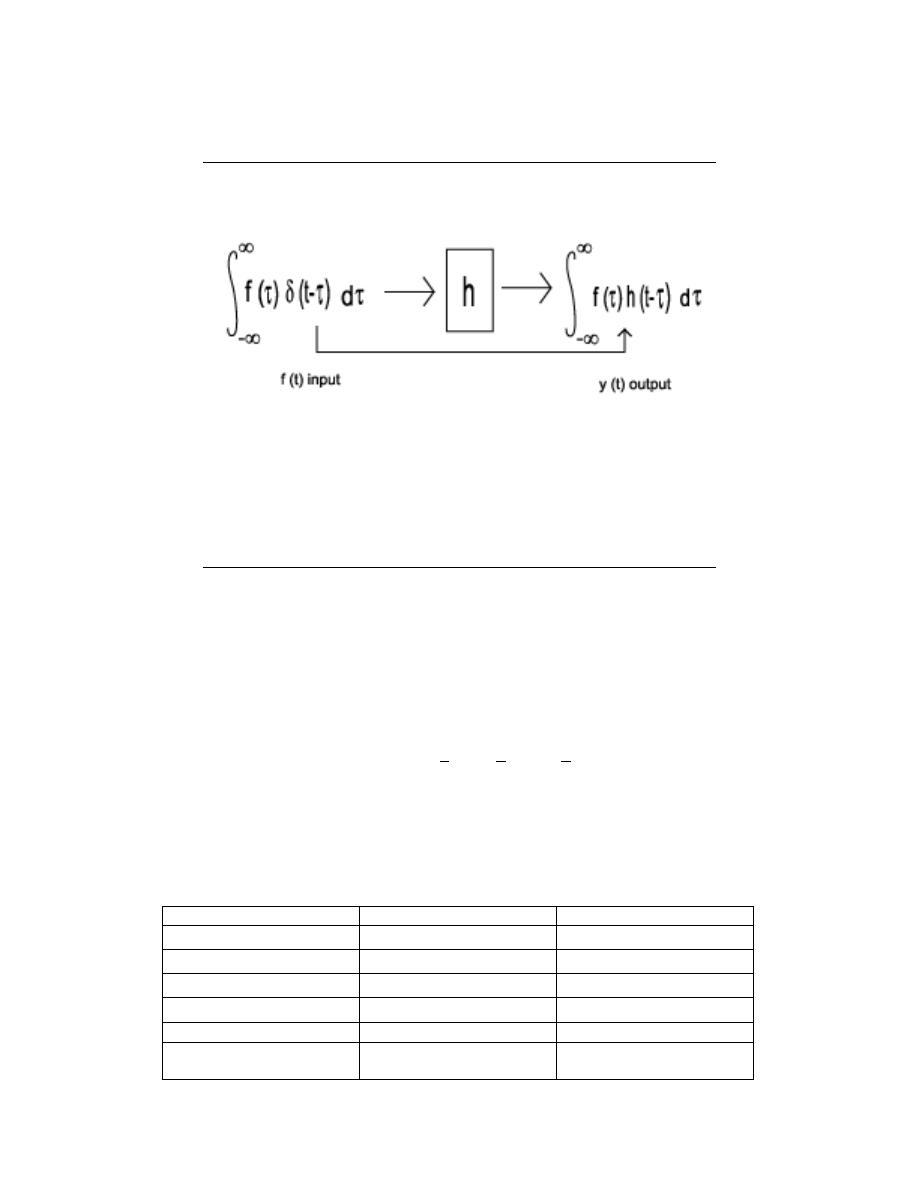

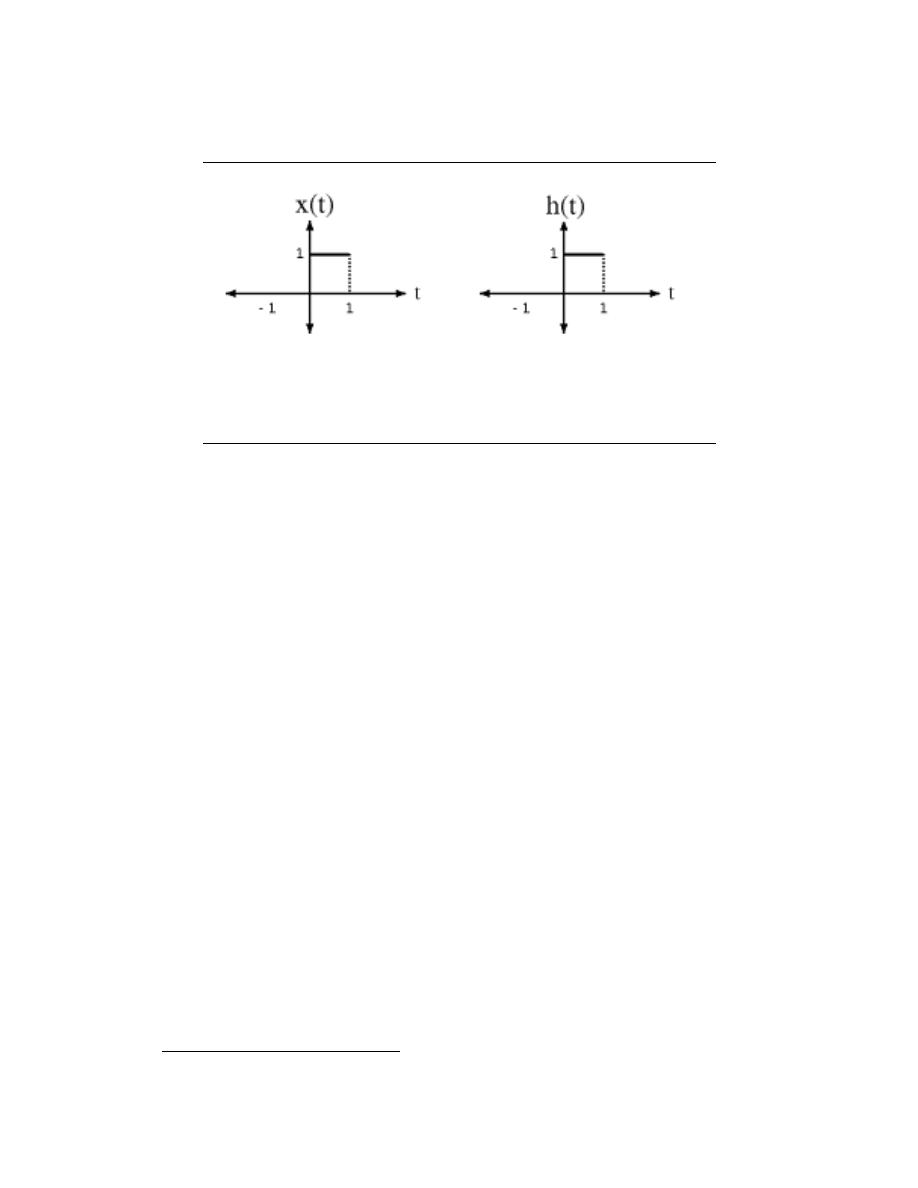

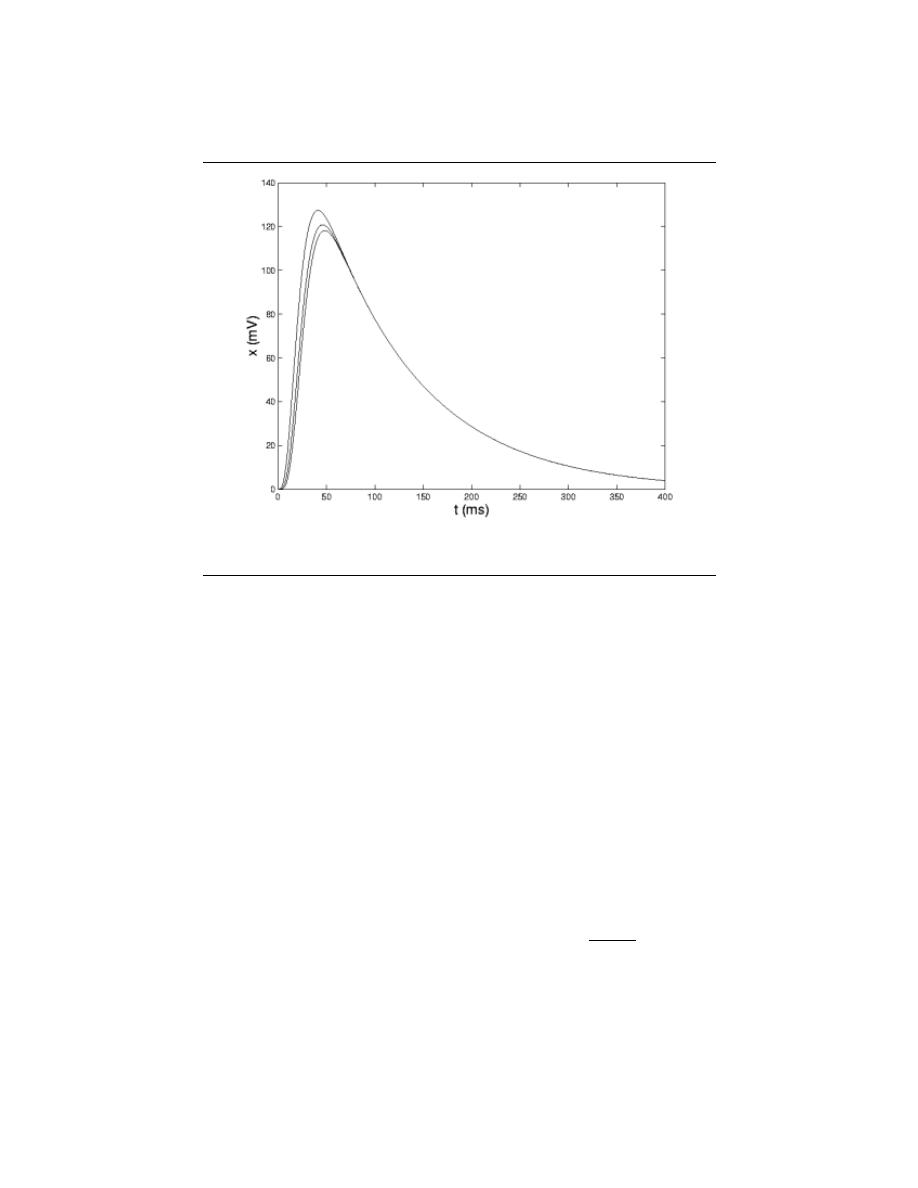

4.2 Continuous-Time Convolution

3.2.1 Motivation

Convolution helps to determine the effect a system has on an input signal. It can be shown

that a linear, time-invariant system is completely characterized by its impulse response.

At first glance, this may appear to be of little use, since impulse functions are not well

defnied in real applications. however, the sifting property of impulses (Section 2.8.1.1) tells

us that a signal can be decomposed into an infinite sum (integral) of scaled and shifted

impulses. By knowing how a system affects a single impulse, and by understanding the way

a signal is comprised of scaled and summed impulses, it seems reasonable that it should be

possible to scale and sum the impulse responses of a system in order to deteremine what

output signal will results from a particular input. This is precisely what convolution does -