بورد عراقي

(

دكتوراه

)

في الطب الباطني

بورد عربي

(

دكتوراه

)

في الطب الباطني

بورد عراقي

(

دكتوراه

)

تخصص دقيق في أمراض

وقسطرة القلب والشرايين

DEFINITION

Heart failure (HF) is a clinical syndrome that

occurs in patients who, because of an inherited

or acquired abnormality of cardiac structure

and/or function, develop a constellation of

clinical symptoms (dyspnea and fatigue) and

signs (edema and rales) that lead to frequent

hospitalizations, a poor quality of life, and a

shortened life expectancy.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The overall prevalence of HF in the adult population in developed countries

is 2%. rising with age, and affects 6–10% of people over age 65.

Although the relative incidence of HF is lower in women than in men, women

constitute at least one-half the cases of HF because of their longer life

expectancy.

The overall prevalence of HF is thought to be increasing, in part because

current therapies for cardiac disorders, such as myocardial infarction (MI),

valvular heart disease, and arrhythmias, are allowing patients to survive

longer.

Although HF once was thought to arise primarily in the setting of a

depressed left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF), epidemiologic studies

have shown that approximately one-half of patients who develop HF have a

normal or preserved EF (EF 40–50%).

Accordingly, HF patients are now broadly categorized into one of two groups:

(1) HF with a depressed EF (commonly referred to as systolic failure) or (2)

HF with a preserved EF (commonly referred to as diastolic failure).

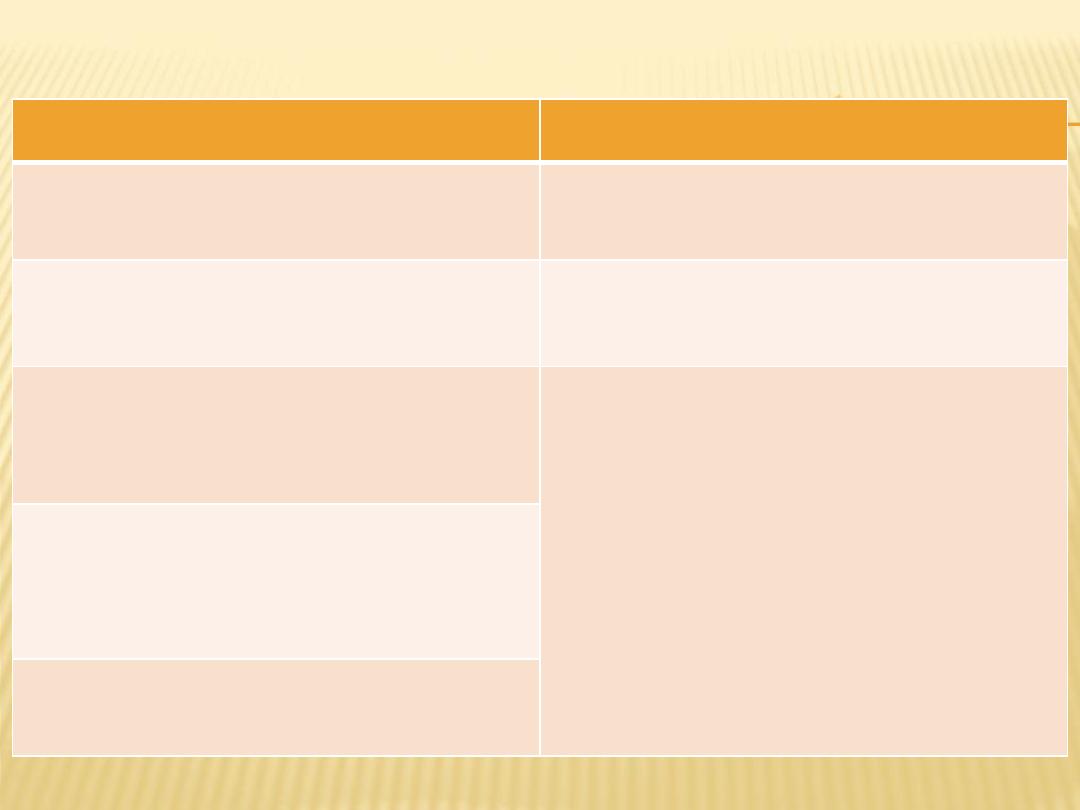

ETIOLOGY

Depressed Ejection Fraction (<40%)

Preserved Ejection Fraction (>40–50%)

Coronary artery disease

• Myocardial infarction

• Myocardial ischemia

Pathologic hypertrophy

• Primary (hypertrophic cardiomyopathies)

• Secondary (hypertension)

Chronic pressure overload

• Hypertension

• Obstructive valvular disease

Aging

Chronic volume overload

• Regurgitant valvular disease

• Intracardiac shunting (L to R)

• Extrracardiac shunting

Restrictive cardiomyopathy

• Infiltrative disorders (amyloidosis,

sarcoidosis)

• Storage diseases (hemochromatosis)

• Fibrosis

• Endomyocardial disorders

Nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy

• Familial or genetic disorders

• Toxic or drug-induced damage

• Metabolic disorder

• Viral or other infectious agents

Disorders of rate and rhythm

• Chronic bradyarrhythmias

• Chronic tachyarrhythmias

Pulmonary Heart Disease

High-Output States

Cor pulmonale

Metabolic disorders

• Thyrotoxicosis

• Nutritional disorders (beriberi)

Pulmonary vascular disorders

Excessive blood-flow requirements

• Systemic arteriovenous shunting

• Chronic anemia

• In 20–30% of the cases of HF with a depressed EF, the exact etiologic basis is not

known. These patients are referred to as having

nonischemic, dilated, or idiopathic

cardiomyopathy

if the cause is unknown

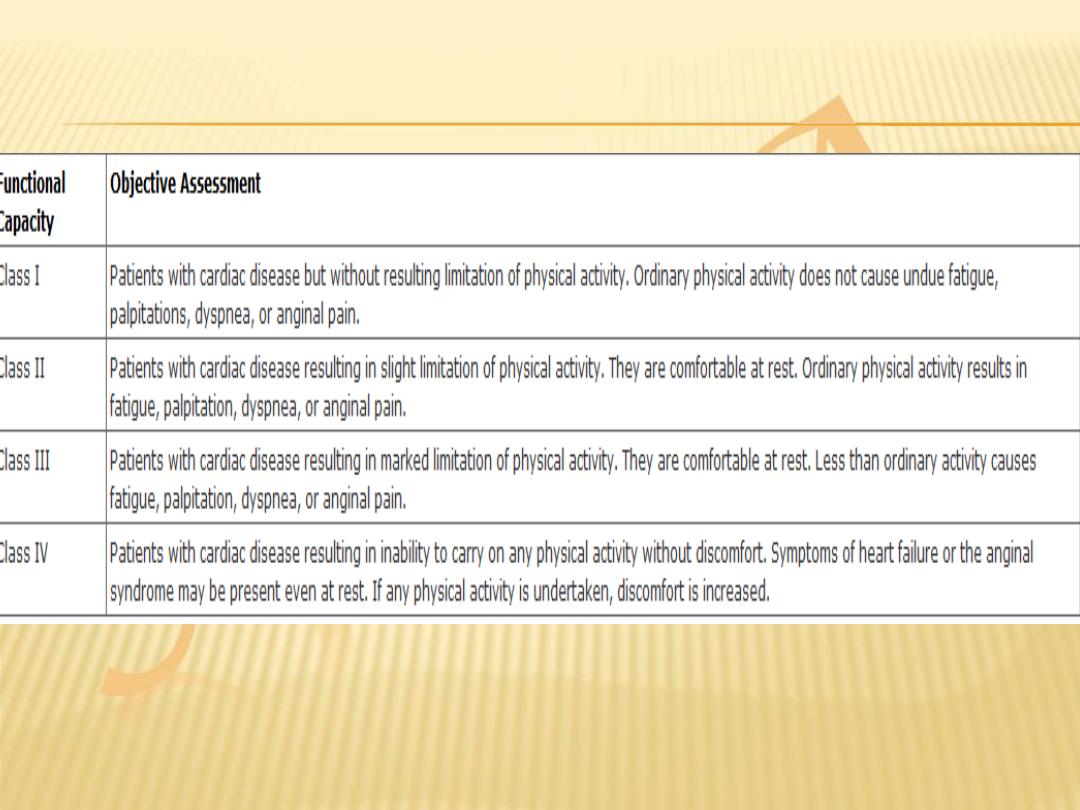

PROGNOSIS

Despite many recent advances in the evaluation

and management of HF, the development of

symptomatic HF still carries a poor prognosis.

Although it is difficult to predict prognosis in an

individual, patients with symptoms at rest [New

York Heart Association (NYHA) class IV] have a

30–70% annual mortality rate, whereas patients

with symptoms with moderate activity (NYHA class

II) have an annual mortality rate of 5–10%.

Thus, functional status is an important predictor

of patient outcome

NEW YORK HEART ASSOCIATION

CLASSIFICATION

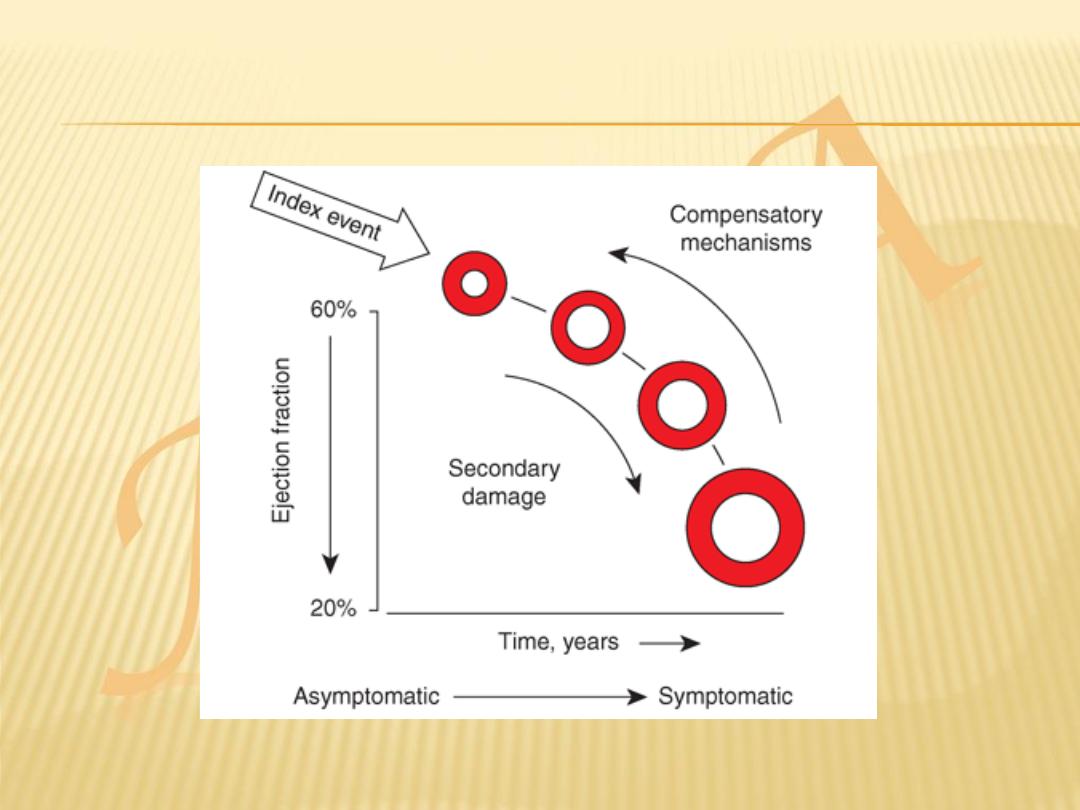

PATHOGENESIS

HF may be viewed as a progressive disorder that is

initiated after an

index event

either damages the heart

muscle, with a resultant loss of functioning cardiac

myocytes, or, alternatively, disrupts the ability of the

myocardium to generate force, thereby preventing the

heart from contracting normally.

This index event may have an

abrupt onset

, as in the

case of a myocardial infarction (MI); it may have a

gradual or insidious onset

, as in the case of

hemodynamic pressure or volume overloading; or it may

be hereditary, as in the case of many of the genetic

cardiomyopathies.

Regardless of the nature of the inciting event, the

feature that is common to each of these index events is

that they all in some manner produce

a decline in the

pumping capacity of the heart.

Although the precise reasons why patients with LV dysfunction may remain

asymptomatic is not certain, one potential explanation is that a number of

compensatory mechanisms

become activated in the presence of cardiac

injury and/or LV dysfunction allowing patients to sustain and modulate LV

function for a period of months to years.

The list of

compensatory mechanisms

that have been described thus far

include:

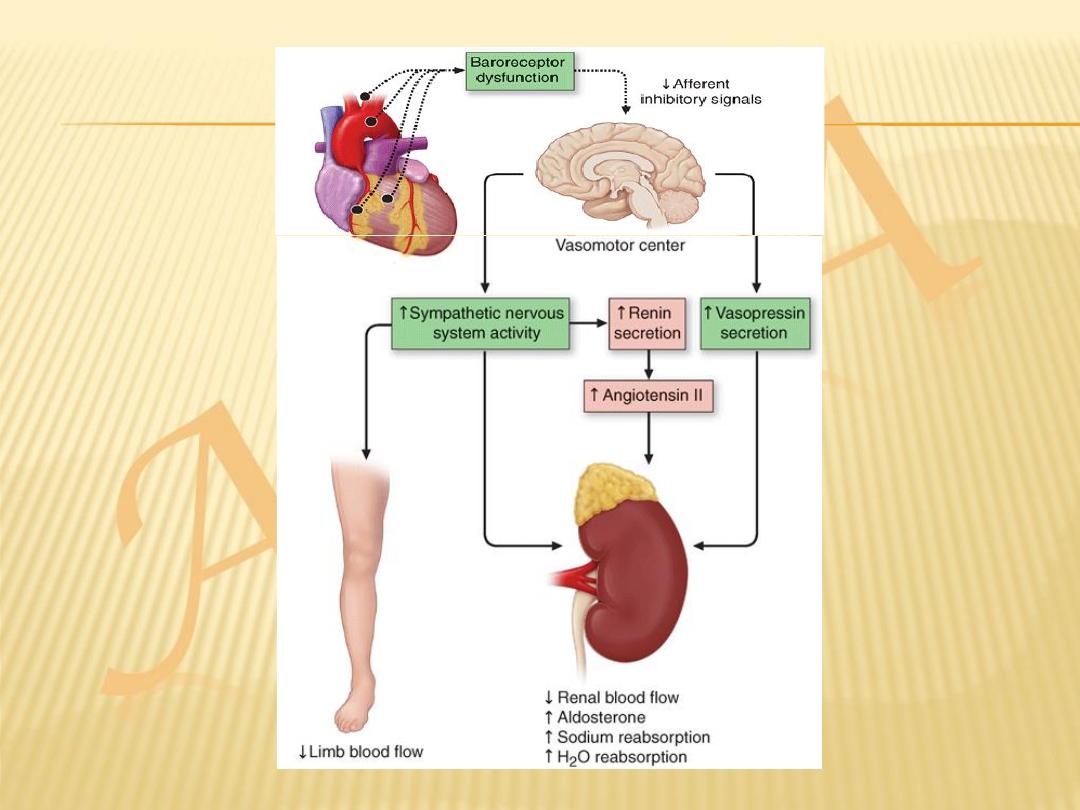

(1) activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAA) and adrenergic nervous

systems, which are responsible for maintaining cardiac output through

increased retention of salt and water

and (2) increased myocardial contractility.

In addition, there is activation of a family of countervailing vasodilatory

molecules, including the atrial and brain natriuretic peptides (ANP and

BNP), prostaglandins (PGE2 and PGI2), and nitric oxide (NO), that offsets

the excessive peripheral vascular vasoconstriction.

Thus, patients may remain asymptomatic or

minimally symptomatic for a period of years;

however, at some point patients become overtly

symptomatic, with a resultant striking increase in

morbidity and mortality rates.

the transition to symptomatic HF is accompanied

by increasing activation of neurohormonal,

adrenergic, and cytokine systems that lead to a

series of adaptive changes within the myocardium

collectively referred to as

LV remodeling

.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL CHANGES IN

HEART FAILURE

Ventricular dilatation

Myocyte hypertrophy

Increased collagen synthesis

Altered myosin gene expression

Altered sarcoplasmic Ca2+-ATPase density

Increased ANP secretion

Salt and water retention

Sympathetic stimulation

Peripheral vasoconstriction

TYPES OF HEART FAILURE

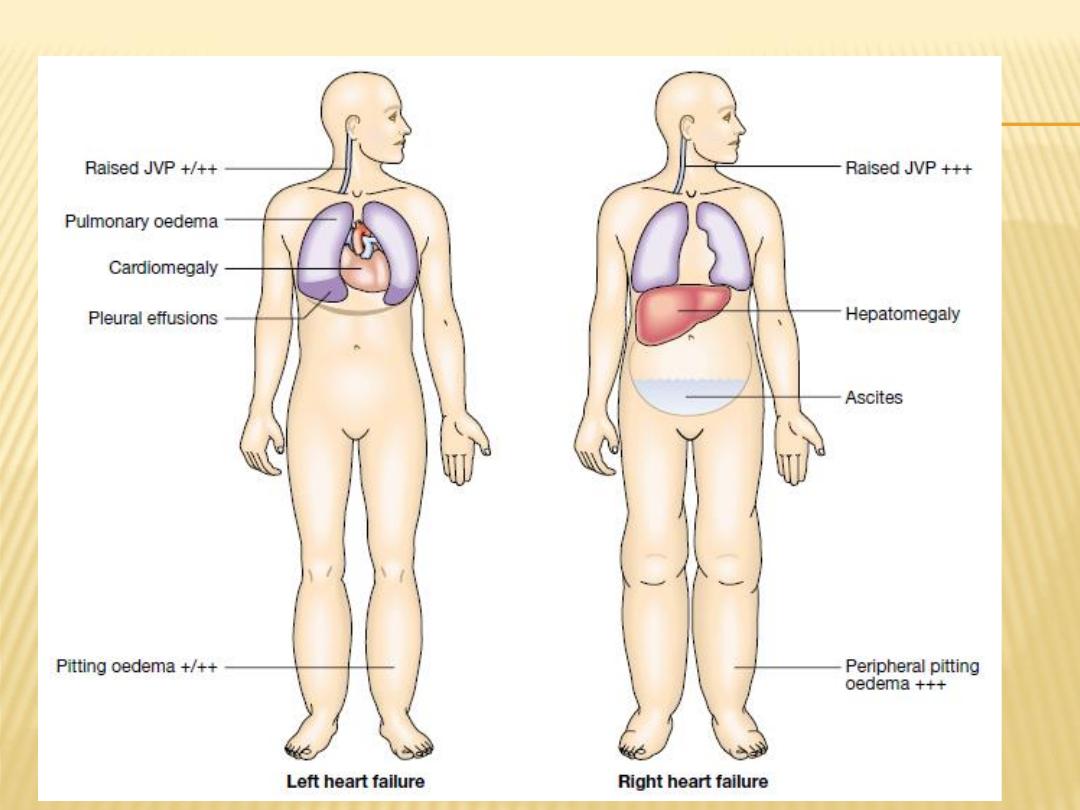

Left-sided heart failure

. There is a reduction in the

left ventricular output and an increase in the left

atrial or pulmonary venous pressure.

Right-sided heart failure

. There is a reduction in

right ventricular output for any given right atrial

pressure.

Causes of isolated right heart failure include chronic

lung disease (cor pulmonale), multiple pulmonary

emboli and pulmonary valvular stenosis.

Left, right and biventricular heart failure

Biventricular heart failure

. Failure of the left

and right heart may develop because

the disease process, such as dilated

cardiomyopathy or ischaemic heart disease, affects

both ventricles

or because disease of the left heart leads to

chronic elevation of the left atrial pressure,

pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure.

Diastolic and systolic dysfunction

Heart failure may develop as a result of

impaired myocardial contraction (systolic

dysfunction)

but can also be due to poor ventricular filling and

high filling pressures caused by abnormal

ventricular relaxation (diastolic dysfunction).

The latter is caused by a stiff non-compliant ventricle

and is commonly found in patients with left ventricular

hypertrophy.

NB

: Systolic and diastolic dysfunction often coexist,

particularly in patients with coronary artery disease.

Heart failure may develop suddenly, as in MI, or

gradually, as in progressive valvular heart

disease.

When there is gradual impairment of cardiac

function, a variety of compensatory changes

may take place.

High-output failure

Conditions such as large arteriovenous shunt,

beri-beri , severe anaemia or thyrotoxicosis can

occasionally cause heart failure due to an

excessively high cardiac output.

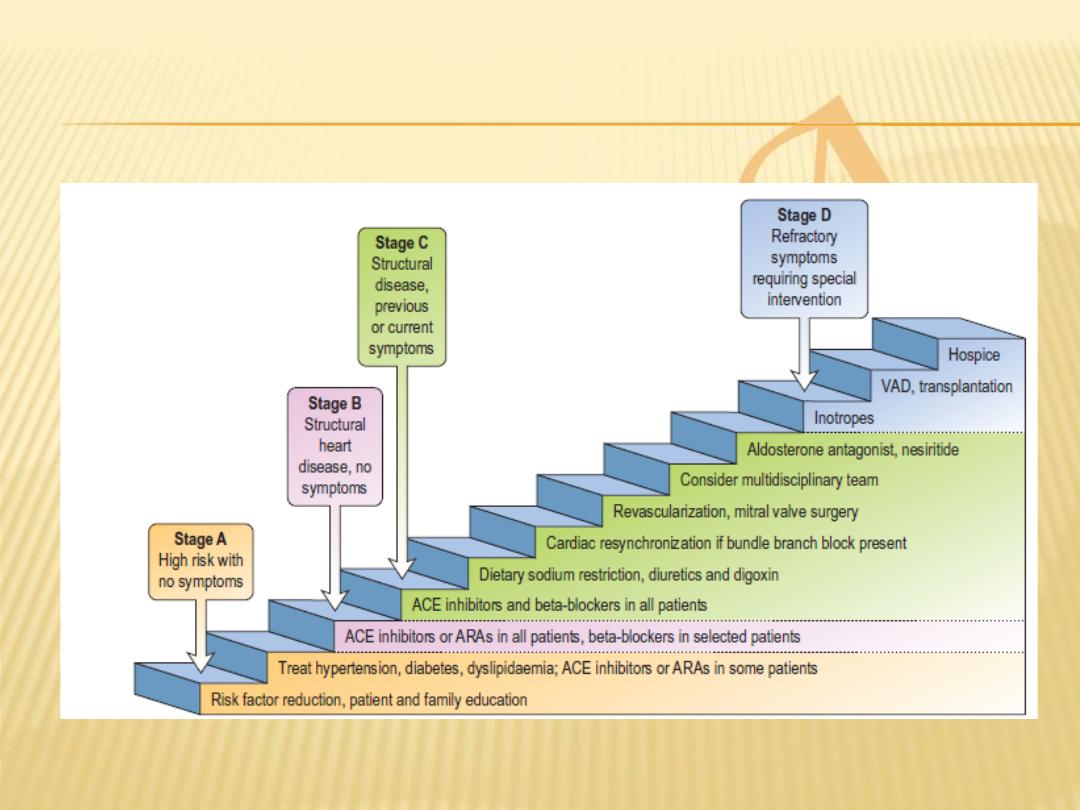

Stages of HF

Stage A

: patients at high risk for developing heart

failure but without structural disorders of the heart

Stage B

: patients with a structural disorder of the

heart but no symptoms of heart failure

Stage C

: patients with past or current symptoms of

heart failure associated with underlying structural

heart disease

Stage D

: patients with end-stage disease who

require specialized treatment strategies such as

mechanical circulatory support, continuous

inotropic infusions, cardiac transplantation, or

hospice care

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms

The cardinal symptoms of HF are

fatigue

and

shortness of breath

.

Although fatigue traditionally has been ascribed to the

low cardiac output in HF, it is likely that skeletal-muscle

abnormalities and other noncardiac comorbidities (e.g.,

anemia) also contribute to this symptom.

Orthopnea

, which is defined as dyspnea occurring

in the recumbent position, is usually a later

manifestation of HF than is exertional dyspnea.

It results from redistribution of fluid from the

splanchnic circulation and lower extremities into the

central circulation during recumbency, with a resultant

increase in pulmonary capillary pressure.

Paroxysmal Nocturnal Dyspnea

(PND): This term

refers to acute episodes of severe shortness of

breath and coughing that generally occur at night

and awaken the patient from sleep, usually 1–3

hours after the patient retires. PND may be

manifest by coughing or wheezing, possibly

because of increased pressure in the bronchial

arteries leading to airway compression, along with

interstitial pulmonary edema that leads to

increased airway resistance

Cheyne-Stokes Respiration

( 40%)

Acute Pulmonary Edema

OTHER SYMPTOMS

Gastrointestinal symptoms

. Anorexia, nausea, and early

satiety associated with abdominal pain and fullness are

common complaints and may be related to edema of

the bowel wall and/or a congested liver.

Cerebral symptoms

such as confusion, disorientation,

and sleep and mood disturbances may be observed in

patients with severe HF, particularly elderly patients with

cerebral arteriosclerosis and reduced cerebral

perfusion.

Nocturia

is common in HF and may contribute to

insomnia.

Physical Examination

In mild or moderately severe HF

, the patient appears to be in no

distress at rest except for feeling uncomfortable when lying flat for

more than a few minutes.

In more severe HF

, the patient must sit upright, may have labored

breathing, and may not be able to finish a sentence because of

shortness of breath.

Systolic blood pressure

may be normal or high in early HF, but

generally is reduced in advanced HF because of severe LV

dysfunction.

The pulse pressure

may be diminished, reflecting a reduction in

stroke volume.

Sinus tachycardia

is a nonspecific sign caused by increased

adrenergic activity.

Peripheral vasoconstriction

leading to cool peripheral extremities and

cyanosis of the lips and nail beds is also caused by excessive

adrenergic activity.

General Appearance and Vital Signs

JUGULAR VEINS

Elevated

PULMONARY EXAMINATION

Pulmonary crackles (rales or crepitations)

result from the transudation of fluid from the

intravascular space into the alveoli.

In patients with pulmonary edema, rales may be

heard widely over both lung fields and may be

accompanied by expiratory wheezing (

cardiac

asthma

).

Pleural effusions(unilateral on the right or

bilateral)

CARDIAC EXAMINATION

Cardiomegaly

, the point of maximal impulse (PMI)

usually is displaced below the fifth intercostal space

and/or lateral to the midclavicular line, and the impulse

is palpable over two interspaces.

In some patients, a

third heart sound

(S

3

) is audible and

palpable at the apex.

Patients with enlarged or hypertrophied right ventricles

may have a sustained and prolonged

left parasternal

impulse

extending throughout systole.

A fourth heart sound

(S

4

) is not a specific indicator of HF

but is usually present in patients with diastolic

dysfunction.

The

murmurs of mitral and tricuspid regurgitation

are

frequently present in patients with advanced HF.

ABDOMEN AND EXTREMITIES

Hepatomegaly

is an important sign in patients with

HF. When it is present, the enlarged liver is

frequently tender and may pulsate during systole if

tricuspid regurgitation is present.

Ascites

, a late sign, occurs as a consequence of

increased pressure in the hepatic veins and the

veins draining the peritoneum.

Jaundice

, also a late finding in HF, results from

impairment of hepatic function secondary to

hepatic congestion and hepatocellular hypoxemia

and is associated with elevations of both direct

and indirect bilirubin.

Peripheral edema

is a cardinal manifestation of

HF, but it is nonspecific and usually is absent in

patients who have been treated adequately

with diuretics.

Long-standing edema may be associated with

indurated and pigmented skin.

Cardiac Cachexia

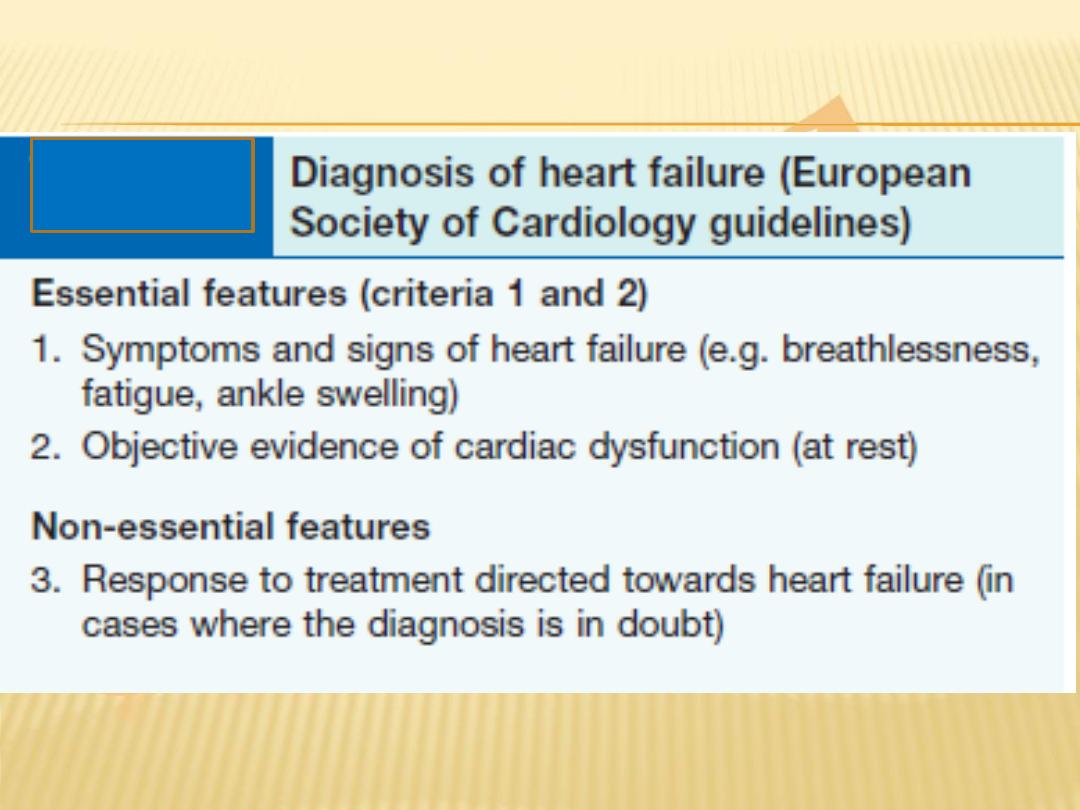

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of heart failure should not be

based on history and clinical findings; it

requires evidence of cardiac dysfunction with

appropriate investigation using objective

measures of left ventricular structure and

function (usually echocardiography).

INVESTIGATIONS IN HEART FAILURE

Blood tests

: complete blood count, a panel of

electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, serum

creatinine, hepatic enzymes, and a urinalysis.

Selected patients should have assessment for

diabetes mellitus

(fasting serum glucose or oral

glucose tolerance test),

dyslipidemia

(fasting lipid

panel), and

thyroid abnormalities

(thyroid-

stimulating hormone level).

BIOMARKERS

Circulating levels of natriuretic peptides are useful

adjunctive tools in the diagnosis of patients with HF.

Both B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal

pro-BNP, which are released from the failing heart, are

relatively sensitive markers for the presence of HF with

depressed EF;

they also are elevated in HF patients with a preserved EF,

albeit to a lesser degree.

However, it is important to recognize that natriuretic

peptide levels increase with

age

and

renal impairment

,

are more elevated in

women

, and can be elevated in

right HF

from any cause.

Levels can be falsely low in

obese patients

and may

normalize in some patients after appropriate treatment.

Chest X-ray.

Look for cardiomegaly, pulmonary

congestion with upper lobe diversion, fluid in

fissures, Kerley B lines, and pulmonary oedema.

Electrocardiogram

for ischaemia, chamber

enlargement or arrhythmia.

Echocardiography.

Cardiac chamber dimension,

systolic and diastolic function, regional wall motion

abnormalities, valvular heart disease,

cardiomyopathies.

Stress echocardiography.

Assessment of viability

in dysfunctional myocardium

Nuclear cardiology.

Radionucleotide angiography

(RNA) can quantify ventricular ejection fraction,

single photon-emission computed tomography (SPECT)

or

positron emission tomography (PET)

can

demonstrate myocardial ischaemia and viability in

dysfunctional myocardium.

CMR (cardiac MRI).

Assessment of viability in

dysfunctional myocardium with the use of

dobutamine for contractile reserve or with

gadolinium for delayed enhancement (‘infarct

imaging’).

Cardiac catheterization.

Diagnosis of ischaemic

heart failure (and suitability for revascularization),

Cardiac biopsy

.

Diagnosis of cardiomyopathies, e.g. amyloid,

follow-up of transplanted patients to assess rejection.

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

. Peak oxygen

consumption (VO2) is predictive of hospital

admission and death in heart failure.

A 6-minute exercise walk is an alternative.

Ambulatory ECG monitoring (Holter).

In patients

with suspected arrhythmia.

Complications

In advanced heart failure, the following may occur:

Renal failure

is caused by poor renal perfusion

due to a low cardiac output and may be

exacerbated by diuretic therapy, angiotensin-

converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and

angiotensin receptor blockers.

Hypokalaemia

may be the result of treatment with

potassium-losing diuretics or hyperaldosteronism

caused by activation of the renin–angiotensin

system and impaired aldosterone metabolism due

to hepatic congestion.

Hyperkalaemia

may be due to the effects of drug

treatment, particularly the combination of ACE inhibitors

and spironolactone (which both promote potassium

retention), and renal dysfunction.

Hyponatraemia

is a feature of severe heart failure and

is a poor prognostic sign.

Impaired liver function

is caused by hepatic venous

congestion and poor arterial perfusion, which frequently

cause mild jaundice and abnormal liver function tests;

reduced synthesis of clotting factors can make

anticoagulant control difficult.

Thromboembolism

.

Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism may

occur due to the effects of a low cardiac output and

enforced immobility,

whereas systemic emboli may be related to

arrhythmias, atrial flutter or fibrillation, or intracardiac

thrombus complicating conditions such as mitral

stenosis, MI or left ventricular aneurysm.

Atrial and ventricular arrhythmias

are very

common and may be related to

electrolyte changes (e.g. hypokalaemia,

hypomagnesaemia),

the underlying structural heart disease,

and the pro-arrhythmic effects of increased circulating

catecholamines or drugs.

Management of HF with Depressed Ejection

Fraction (<40%)

Clinicians should aim to screen for and

treat comorbidities

such as

hypertension, CAD, diabetes mellitus, anemia, and sleep-disordered

breathing, as these conditions tend to exacerbate HF.

HF patients should be advised to

stop smoking

and to

limit alcohol

consumption

to two standard drinks per day in men or one per day in

women.

Patients suspected of having an alcohol-induced cardiomyopathy should be

urged to abstain from alcohol consumption indefinitely.

Extremes of temperature and heavy physical exertion

should be avoided.

Certain

drugs

are known to make HF worse and should be avoided .For

example, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including cyclooxygenase 2

inhibitors, are not recommended in patients with chronic HF because the

risk of renal failure and fluid retention is markedly increased in the

presence of reduced renal function or ACE inhibitor therapy.

Patients should

receive immunization

with influenza and pneumococcal

vaccines to prevent respiratory infections.

It is equally important to

educate

the patient and family about HF, the

importance of proper diet, and the importance of compliance with the

medical regimen.

General Measures

Diuretics

Many of the clinical manifestations of moderate to severe HF result

from excessive salt and water retention that leads to volume

expansion and congestive symptoms.

Diuretics are the only pharmacologic agents that can adequately

control fluid retention in advanced HF, and they should be used to

restore and maintain normal volume status in patients with

congestive symptoms (dyspnea, orthopnea, edema) or signs of

elevated filling pressures (rales, jugular venous distention, peripheral

edema).

Furosemide, torsemide, and bumetanide

act at the loop of Henle

(loop diuretics) by reversibly inhibiting the reabsorption of Na

+

, K

+

,

and Cl

–

in the thick ascending limb of Henle's loop;

thiazides and metolazone

reduce the reabsorption of Na

+

and Cl

–

in

the first half of the distal convoluted tubule;

and potassium-sparing diuretics

such as spironolactone act at the

level of the collecting duct.

Preventing Disease Progression

Drugs that interfere with excessive activation of

the RAA system and the adrenergic nervous

system can relieve the symptoms of HF with a

depressed EF by stabilizing and/or reversing

cardiac remodeling.

In this regard, ACE inhibitors and beta blockers

have emerged as the cornerstones of modern

therapy for HF with a depressed EF.

ACE INHIBITORS

There is overwhelming evidence that ACE inhibitors should

be used in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with a

depressed EF (<40%).

ACE inhibitors interfere with the renin-angiotensin system by

inhibiting the enzyme that is responsible for the conversion

of angiotensin I to angiotensin II.

ACE inhibitors stabilize

LV remodeling, improve symptoms,

reduce hospitalization, and prolong life.

Because fluid retention can attenuate the effects of ACE

inhibitors, it is preferable to optimize the dose of diuretic

before starting the ACE inhibitor.

ACE inhibitors should be initiated in low doses, followed by

gradual increments if the lower doses have been well

tolerated.

Higher doses are more effective than lower doses in

preventing hospitalization.

Angiotensin Receptor Blockers

These drugs are well tolerated in patients who are intolerant of ACE

inhibitors because of

cough, skin rash, and angioedema.

ARBs should be used in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients

with an EF <40% who are ACE-intolerant for reasons other than

hyperkalemia or renal insufficiency .

Although ACE inhibitors and ARBs inhibit the renin-angiotensin

system, they do so by different mechanisms. Whereas ACE inhibitors

block the enzyme responsible for converting angiotensin I to

angiotensin II, ARBs block the effects of angiotensin II on the

angiotensin type 1 receptor.

When given in concert with beta blockers, ARBs reverse the process

of LV remodeling, improve patient symptoms, prevent hospitalization,

and prolong life.

B-Adrenergic Receptor Blockers

Beta-blocker therapy represents a major advance in the

treatment of patients with a depressed EF.

These drugs interfere with the harmful effects of

sustained activation of the adrenergic nervous system

by competitively antagonizing one or more adrenergic

receptors (a

1

, B

1

, and B

2

).

When given in concert with ACE inhibitors, beta blockers

reverse the process of LV remodeling, improve patient

symptoms, prevent hospitalization, and prolong life.

Therefore, beta blockers are indicated for patients with

symptomatic or asymptomatic HF and a depressed EF

<40%.

Analogous to the use of ACE inhibitors, beta

blockers should be initiated in low doses , followed

by gradual increments in the dose if lower doses

have been well tolerated.

However, unlike ACE inhibitors, which may be

titrated upward relatively rapidly, the titration of

beta blockers should proceed no more rapidly than

at 2-week intervals, because the initiation and/or

increased dosing of these agents may lead to

worsening fluid retention consequent to the

withdrawal of adrenergic support to the heart and

the circulation.

ALDOSTERONE ANTAGONISTS

Although classified as potassium-sparing diuretics,

drugs that block the effects of aldosterone

(spironolactone or eplerenone) have beneficial effects

that are independent of the effects of these agents on

sodium balance.

Although ACE inhibition may transiently decrease

aldosterone secretion, with chronic therapy there is a

rapid return of aldosterone to levels similar to those

before ACE inhibition.

Accordingly, the administration of an aldosterone

antagonist is recommended for patients with NYHA

class II-IV HF who have a depressed EF (<35%) and are

receiving standard therapy, including diuretics, ACE

inhibitors, and beta blockers.

CARDIAC GLYCOSIDES

Digoxin is a cardiac glycoside that is indicated

in:

1.

Patients in atrial fibrillation with heart failure.

2.

It is used as add-on therapy in symptomatic

heart failure patients (in sinus rhythm) already

receiving ACEI and beta-blockers as it is

demonstrated that digoxin result in reduction

of hospital admissions in those patients .

VASODILATORS AND NITRATES

The combination of hydralazine and nitrates

reduces afterload and pre-load and is used in

patients intolerant of ACEI or ARB.

this combination improved survival in patients

with chronic heart failure.

INOTROPIC AND VASOPRESSOR AGENTS

Intravenous inotropes and vasopressor agents

are used in patients with chronic heart failure

who are not responding to oral medication.

Although they produce haemodynamic

improvements they have not been shown to

improve long-term mortality when compared

with placebo.

Anticoagulation and Antiplatelet Therapy

Treatment with warfarin [goal international normalized

ratio (INR) 2–3] is recommended for patients with:

1.

HF and chronic or paroxysmal atrial fibrillation

2.

or with a history of systemic or pulmonary emboli,

including stroke or transient ischemic attack.

3.

Patients with recent MI & documented LV thrombus

should be treated with warfarin (goal INR 2–3) for the initial

3 months after the MI unless there are contraindications to

its use.

Aspirin is recommended in HF patients with

ischemic heart disease for the prevention of MI

and death.

However, lower doses of aspirin (100mg) may

be preferable because of the concern of

worsening of HF at higher doses.

Management of Cardiac Arrhythmias

Atrial fibrillation occurs in 15–30% of patients with HF and is a

common cause of cardiac decompensation.

Most antiarrhythmic agents, with the exception of amiodarone and

dofetilide, have negative inotropic effects and are proarrhythmic.

Amiodarone is a class III antiarrhythmic that has few or no negative

inotropic and/or proarrhythmic effects and is effective against most

supraventricular arrhythmias.

Amiodarone is the preferred drug for restoring and maintaining sinus

rhythm, and it may improve the success of electrical cardioversion in

patients with HF.

Amiodarone increases the level of phenytoin and digoxin and

prolongs the INR in patients taking warfarin.

Therefore, it is often necessary to reduce the dose of these drugs by as

much as 50% when initiating therapy with amiodarone.

The risk of adverse events such as hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism,

pulmonary fibrosis, and hepatitis is relatively low, particularly when

lower doses of amiodarone are used (100–200 mg/d).

Implantable cardiac defibrillators (ICDs)

are highly

effective in treating recurrences of sustained

ventricular tachycardia and/or ventricular

fibrillation in HF patients with recurrent

arrhythmias and/or cardiac syncope, and they may

be used as stand-alone therapy or in combination

with amiodarone and/or a beta blocker .

There is no role for treating ventricular arrhythmias

with an antiarrhythmic agent without an ICD.

NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL TREATMENT OF

HEART FAILURE

Coronary artery bypass surgery or

percutaneous coronary intervention may

improve function in areas of the myocardium

that are ‘hibernating’ because of inadequate

blood supply,

Revascularization

CARDIAC RESYNCHRONIZATION

Approximately one-third of patients with a depressed EF and symptomatic HF (NYHA

class III–IV) manifest a QRS duration >120 ms. (Bundle Branch Block, BBB)

This ECG finding of abnormal inter- or intraventricular conduction has been used to

identify patients with dyssynchronous ventricular contraction.

The mechanical consequences of ventricular dyssynchrony include suboptimal

ventricular filling, a reduction in LV contractility, prolonged duration (and therefore

greater severity) of mitral regurgitation, and paradoxical septal wall motion.

Biventricular pacing, also termed cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT),

stimulates both ventricles nearly simultaneously, thereby improving the coordination

of ventricular contraction and reducing the severity of mitral regurgitation.

When CRT is added to optimal medical therapy in patients in sinus rhythm,

there is a

significant decrease in patient mortality rates and hospitalization and a reversal of

LV remodeling, as well as improved quality of life and exercise capacity.

Accordingly, CRT is recommended for patients in sinus rhythm with an

1.

EF <35%

2.

a QRS >150 ms (with LBBB configuration)

3.

those who remain symptomatic (NYHA II–IV) despite optimal medical therapy.

IMPLANTABLE CARDIAC DEFIBRILLATORS

The prophylactic implantation of ICDs in patients

with mild to moderate HF (NYHA class II–III) has

been shown to reduce the incidence of sudden

cardiac death in patients with ischemic or

nonischemic cardiomyopathy.

Accordingly, implantation of an ICD should be

considered for patients in NYHA class II–III HF with

a depressed EF of <35% who are already on

optimal background therapy, including an ACE

inhibitor (or ARB), a beta blocker, and an

aldosterone antagonist.

CARDIAC TRANSPLANTATION

Cardiac transplantation has become the treatment

of choice for younger patients with severe

intractable heart failure, whose life-expectancy is

less than 6 months.

With careful recipient selection, the expected 1-

year survival for patients following transplantation

is over 90%, and is 75% at 5 years.

Irrespective of survival, quality of life is

dramatically improved for the majority of patients.

The availability of heart transplantation is limited.

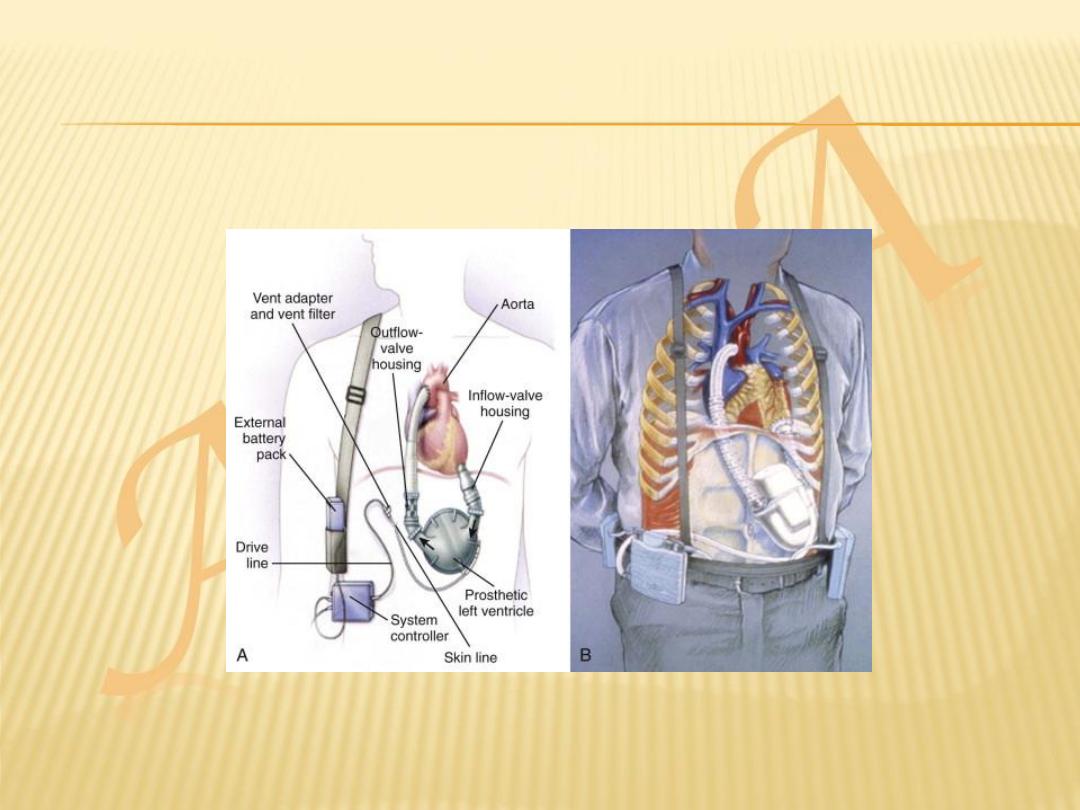

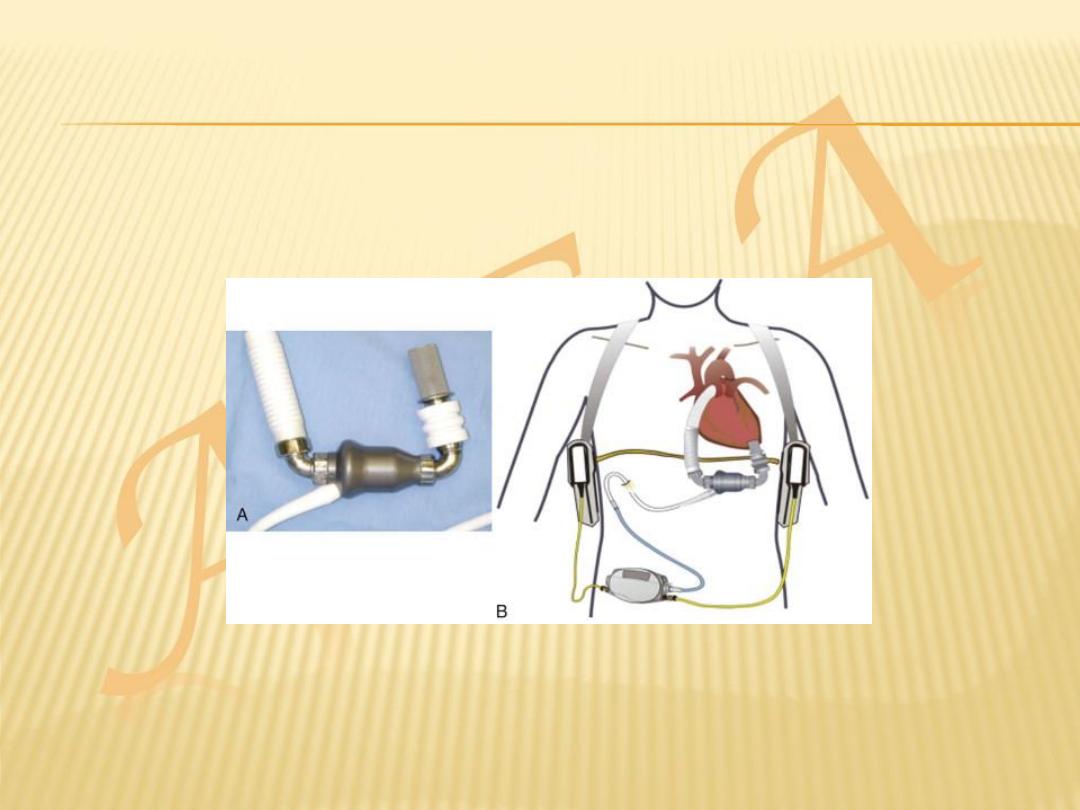

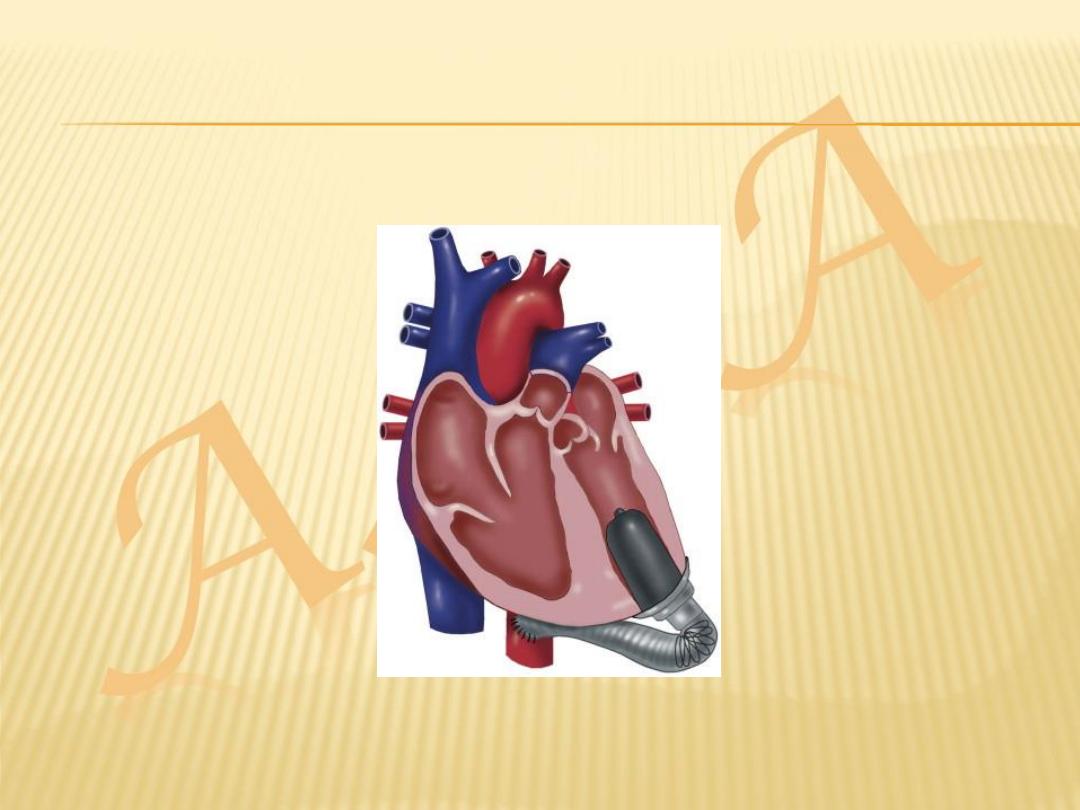

VENTRICULAR ASSIST DEVICES

Because of the limited supply of donor organs,

ventricular assist devices (VADs) have been

employed as:

a bridge to cardiac transplantation

potential long-term ‘destination’ therapy

short-term restoration therapy following a

potentially reversible insult such as viral

myocarditis.

MANAGEMENT OF HF WITH A PRESERVED

EJECTION FRACTION (>40–50%)

Despite the wealth of information with respect to the

evaluation and management of HF with a depressed EF,

there are no proven and/or approved pharmacologic or

device therapies for the management of patients with

HF and a preserved EF.

Therefore, it is recommended that :

1.

Control systolic and diastolic hypertension

2.

Control ventricular rate in patients with atrial fibrillation

3.

Diuretics to control pulmonary congestion and peripheral

edema

Thank you