1

4th stage

Medicine

Lec-3

Dr.Abdullah

4/02/2016

Ulcerative colitis

2

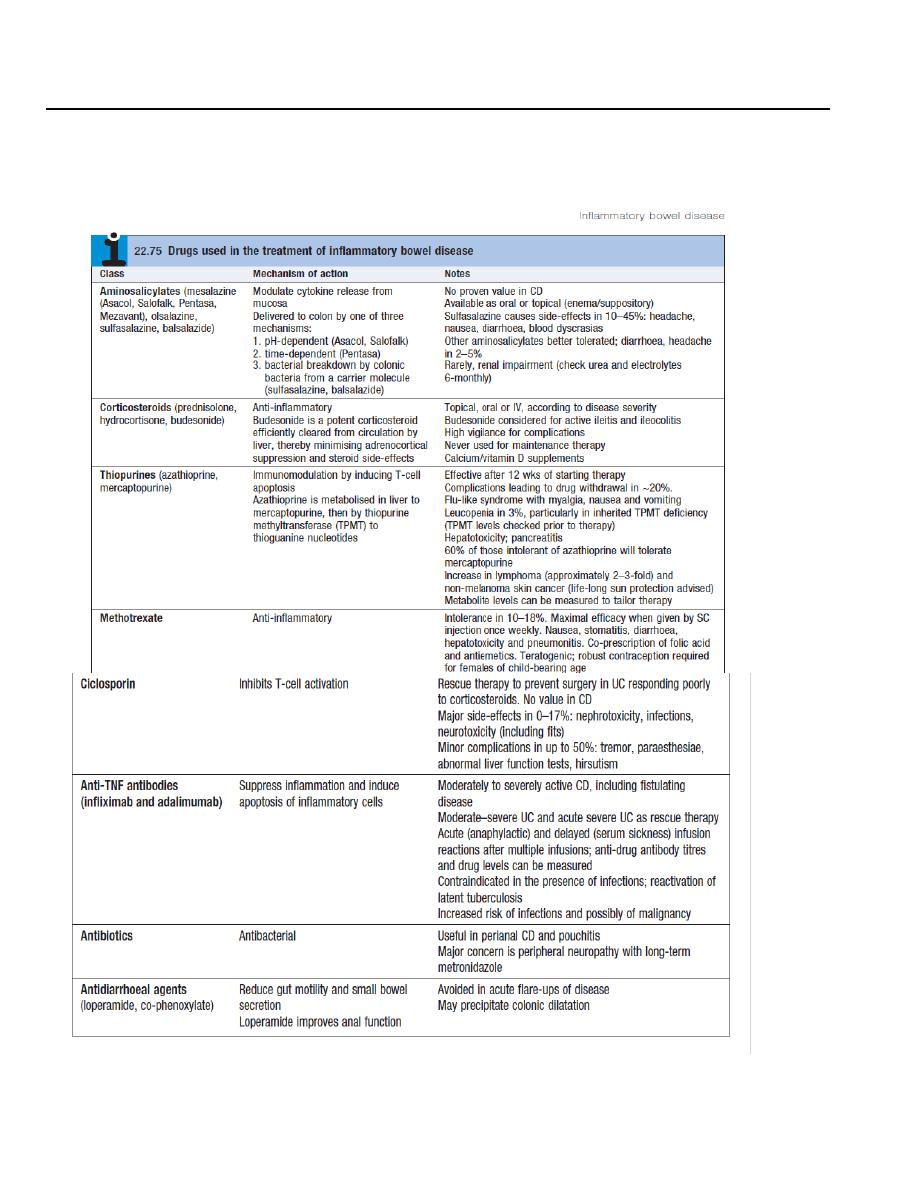

Ulcerative colitis: Active proctitis

Most patients with ulcerative proctitis respond to a 1 g mesalazine suppository but some

will additionally require oral 5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA) therapy.

Topical corticosteroids are less effective and are reserved for patients who are intolerant of

topical mesalazine.

Patients with resistant disease may require treatment with systemic corticosteroids and

immunosuppressants.

Active left-sided or extensive ulcerative colitis

In mild to moderately active cases, the combination of a oral and a topical 5-ASA

preparation.

The topical preparation is typically withdrawn after 1 month. The oral 5-ASA is continued

long-term to prevent relapse.

In patients who do not respond to this approach within 2–4 weeks, oral prednisolone (40

mg daily, tapered by 5 mg/week over an 8-week total course) is indicated. Corticosteroids

should never be used for maintenance therapy.

At the first signs of corticosteroid resistance or in patients who require high corticosteroid

doses to maintain control, immunosuppressive therapy with a thiopurine should be

introduced.

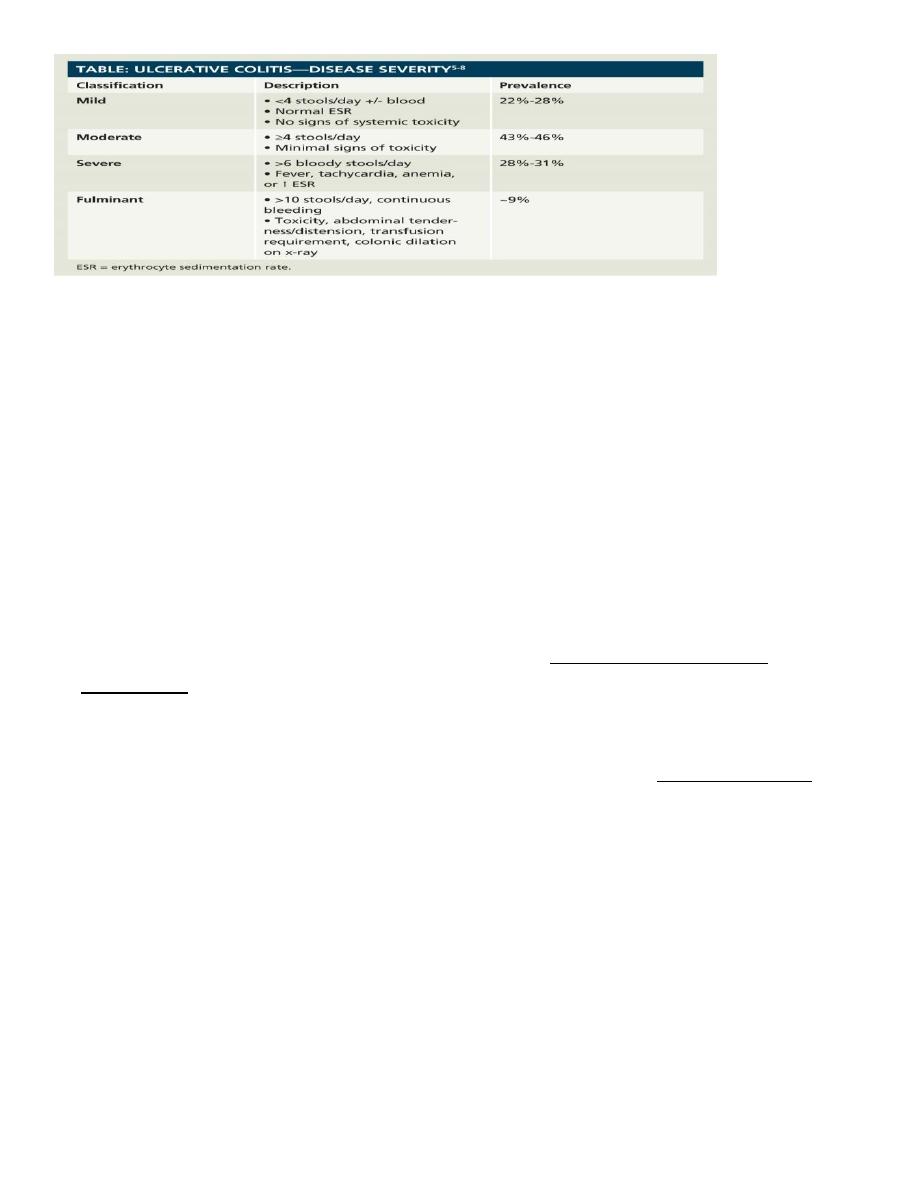

Severe ulcerative colitis

Patients who fail to respond to maximal oral therapy and those who present with acute

severe colitis are best managed in hospital and should be monitored jointly by a physician

and surgeon:

clinically: for the presence of abdominal pain,temperature, pulse rate, stool blood and

frequency.

3

by laboratory testing: haemoglobin, white cell count, albumin, electrolytes, ESR and CRP

radiologically: for colonic dilatation on plain abdominal X-rays.

Medical management of fulminant ulcerative colitis :-

• Admit to hospital for intensive therapy and monitoring.

• Intravenous fluids and correction of electrolyte imbalance.

• Transfusion if haemoglobin< 100 g/L (< 10 g/dL).

• IV methylprednisolone (60 mg daily) or hydrocortisone (400 mg daily).

• Antibiotics until enteric infection excluded.

• Nutritional support.

• Subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin for prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism.

• Avoidance of opiates and anti diarrhoeal agents.

• Consider infliximab (5 mg/kg) or ciclosporin (2 mg/kg) in stable patients not responding to

3–5 days of corticosteroids.

• Patients who develop colonic dilatation (> 6 cm), those whose clinical and laboratory

measurements deteriorate and those who do not respond after 7–10 days’ maximal

medical treatment usually require urgent colectomy.

Maintenance of remission

• Life-long maintenance therapy is recommended for all patients with left-sided or extensive

disease but is not necessary in those with proctitis.

• Once-daily oral 5-aminosalicylates are the preferred first-line agents. Sulfasalazine can be

considered in patients with coexistent arthropathy.

• Patients who frequently relapse despite aminosalicylate drugs should be treated with

thiopurines.

Surgical treatment:

The choice of procedure is either panproctocolectomy with ileostomy, or proctocolectomy

with ileal–anal pouch anastomosis.

4

Crohn’s disease

Crohn’s disease is a progressive condition which may result in stricture or fistula formation if

suboptimally treated.

It is therefore important to agree long-term treatment goals with the patient; these are to

induce remission and then maintain corticosteroid-free remission with a normal quality of life.

Induction of remission

Corticosteroids remain the mainstay of treatment for active Crohn’s disease.

The drug of first choice in patients with ileal disease is budesonide, since it undergoes 90%

first-pass metabolism in the liver and has very little systemic toxicity. If there is no

response to budesonide within 2 weeks, the patient should be switched to prednisolone ,

which has greater potency.

As an alternative to corticosteroid therapy, enteral nutrition with either an elemental

(constituent amino acids) or polymeric (liquid protein) diet may induce remission.

Some patients with severe colonic disease require admission to hospital for intravenous

corticosteroids. In severe ileal or panenteric disease, induction therapy with an anti-TNF

agent is appropriate, provided that acute perforating complications, such as abscess, have

not occurred.

Randomised trials have demonstrated that combination therapy with an anti-TNF antibody

and a thiopurine is the most effective strategy for inducing and maintaining remission in

luminal Crohn’s patients.

Maintenance therapy

Immunosuppressive treatment with thiopurines (azathioprine and mercaptopurine) forms

the core of maintenance therapy, but methotrexate is also effective and can be given once

weekly, either orally or by subcutaneous injection.

Combination therapy with an immunosuppressant and an anti-TNF antibody is the most

effective strategy but costs are high and there is an increased risk of serious adverse

effects.

Cigarette smokers should be strongly counselled to stop smoking at every possible

opportunity. Those that do not manage to stop smoking fare much worse, with increased

rates of relapse and surgical intervention.

5

Surgical treatment:

• The indications for surgery are similar to those for ulcerative colitis. Operations are often

necessary to deal with fistulae, abscesses and perianal disease, and may also be required to

relieve small or large bowel obstruction. In contrast to ulcerative colitis, surgery is not

curative and disease recurrence is the rule.

• Surgery should be as conservative as possible in order to minimize loss of viable intestine

and to avoid creation of a short bowel syndrome.

Microscopic colitis

Microscopic colitis, which comprises two related conditions, lymphocytic colitis and

collagenous colitis, has no known cause.

The presentation is with watery diarrhoea. The colonoscopic appearances are normal but

histological examination of biopsies is abnormal.

Collagenous colitis is characterized by the presence of a submucosal band of collagen, often

with a chronic inflammatory infiltrate.

The disease is more common in women and may be may be associated with rheumatoid

arthritis, diabetes, coeliac disease and some drug therapies, such as NSAIDs or PPIs.

Treatment with budesonide is usually effective but the condition will recur in some patients

on discontinuation of therapy.

IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME(IBS)

• About 10–15% of the population are affected at some time but only 10% of these consult

their doctors .

• Young women are affected 2–3 times more often than men.

• Coexisting conditions, such as non-ulcer dyspepsia, chronic fatigue syndrome,

dysmenorrhoea and fibromyalgia, are common.

• Between 5 and 10% of patients have a history of physical or sexual abuse.

6

Pathophysiology of IBS

Behavioral and psychosocial factors:

About 50% of patients referred to hospital have a psychiatric illness, such as anxiety,

depression, somatisation and neurosis . Panic attacks are also common.

Acute psychological stress and overt psychiatric disease are known to alter visceral

perception and gastrointestinal motility.

These factors contribute to but do not cause IBS.

Physiological factors :

There is some evidence that IBS may be a serotoninergic (5-HT) disorder, as evidenced by

relatively excessive release of 5-HT in diarrhoea-predominant IBS (D-IBS) and relative

deficiency with constipation-predominant IBS (C-IBS). Accordingly, 5-HT3 receptor

antagonists are effective in D-IBS, while 5-HT4 agonists improve bowel function in C-IBS.

There is some evidence that IBS may represent a state of low-grade gut inflammation or

immune activation, not detectable by tests.

Immune activation may be associated with altered CNS processing of visceral pain signals.

This is more common in women and in D-IBS, and may be triggered by a prior episode of

gastroenteritis with Salmonella or Campylobacter species.

Luminal factors :

Both quantitative and qualitative alterations in intestinal bacterial contents (the gut

microbiota) have been reported. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) may be present

in some patients and lead to symptoms.

This ‘gut dysbiosis’ may explain the response to probiotics or the non-absorbable antibiotic

rifaximin.

Dietary factors are also important. Some patients have chemical food intolerances (not allergy)

to poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates (lactose, fructose and sorbitol, among others),

collectively known as FODMAPs (fermentable oligo-, di- and monosaccharides and polyols).

Their fermentation in the colon leads to bloating, pain, wind and altered bowel habit.

Non coeliac gluten sensitivity (negative coeliac serology and normal duodenal biopsies) seems

to be present in some IBS patients.

7

Clinical features of IBS

Rome III criteria for diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome:

Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least 3 days/month in the last 3 months,

associated with two or more of the following:

1. Improvement with defecation

2. Onset associated with a change in frequency of stool

3. Onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool

The most common presentation is recurrent abdominal discomfort . this is usually colicky

or cramping in nature, felt in the lower abdomen and relieved by defecation. Abdominal

bloating worsens throughout the day.

The bowel habit is variable , most patients alternate between episodes of diarrhea and

constipation, but it is useful to classify patients as having predominantly constipation or

predominantly diarrhoea.

Those with constipation tend to pass infrequent pellety stools, usually in association with

abdominal pain or proctalgia.

Those with diarrhoea have frequent defecation but produce low-volume stools and rarely

have nocturnal symptoms. Passage of mucus is common but rectal bleeding does not occur.

Patients do not lose weight and are constitutionally well.

Physical examination is generally unremarkable, with the exception of variable tenderness

to palpation.

Diagnosis of IBS

The diagnosis is clinical and can be made confidently in most patients using the Rome

criteria combined with the absence of alarm symptoms, without resorting to complicated

tests.

Alarm features:

• Age > 50 yrs; mainly male gender • Weight loss • Nocturnal symptoms • Family history of

colon cancer• Anaemia • Rectal bleeding.

Those who present atypically require investigations to exclude other gastrointestinal

diseases.

Diarrhea predominant patients justify investigations to exclude coeliac disease ,microscopic

colitis ,lactose intolerance , bile acid malabsorption, thyrotoxicosis and, in developing

countries parasitic infection.

8

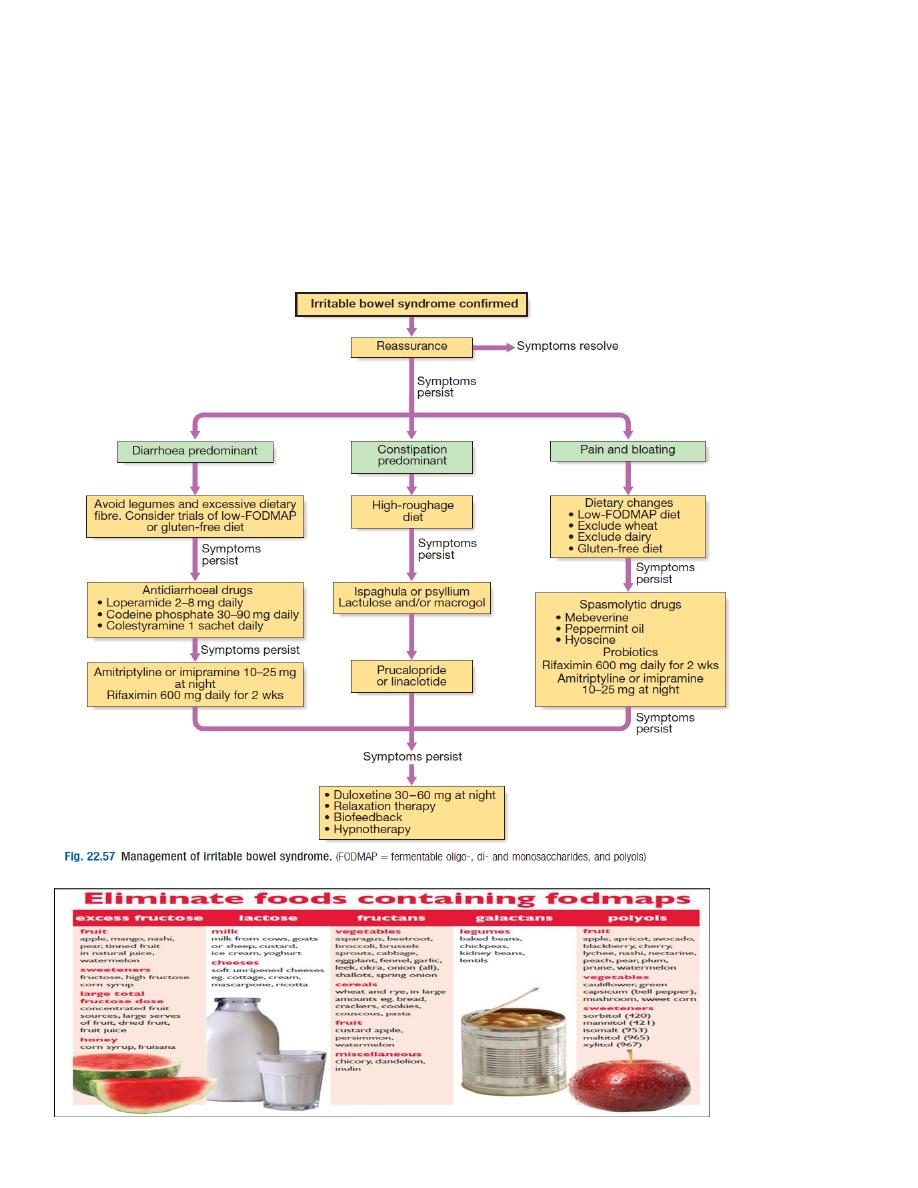

Management of IBS

The most important steps are to make a positive diagnosis and reassure the patient.

Many patients are concerned that they have developed cancer, and a cycle of anxiety leading

to colonic symptoms, which further heighten anxiety, can be broken by explanation that

symptoms are not due to a serious underlying disease but instead are the result of

behavioural, psychosocial, physiological and luminal factors described above.