1

Forth stage

Medicine

Lec-9

.د

رامي

1/1/2014

Empyema

This is a collection of pus in the pleural space, which may be as thin as serous fluid or

so thick that it is impossible to aspirate, even through a wide-bore needle.

Microscopically, neutrophil leucocytes are present in large numbers. An empyema

may involve the whole pleural space or only part of it (‘loculated’ or ‘encysted’ empyema)

and is usually unilateral. It is always secondary to infection in a neighbouring structure,

usually the lung, most commonly due to the bacterial pneumonias and tuberculosis. Over

40% of patients with community acquired pneumonia develop an associated pleural

effusion (‘para-pneumonic’ effusion) and about 15% of these become secondarily

infected.

Other causes are infection of a haemothorax following trauma or surgery, oesophageal

rupture, and rupture of a subphrenic abscess through the diaphragm.

The pus in the pleural space is often under considerable pressure, and if the

condition is not adequately treated, pus may rupture into a bronchus, causing a

bronchopleural fistula and pyopneumothorax, or track through the chest wall with the

formation of a subcutaneous abscess or sinus, so-called empyema necessitans.

Clinical assessment:

An empyema should be suspected in patients with pulmonary infection if there is severe

pleuritic chest pain or persisting or recurrent pyrexia, despite appropriate antibiotic

treatment. In other cases, the primary infection may be so mild that it passes

unrecognised and the first definite clinical features are due to the empyema itself. Once an

empyema has developed, systemic features are Prominent.

2

Investigations:

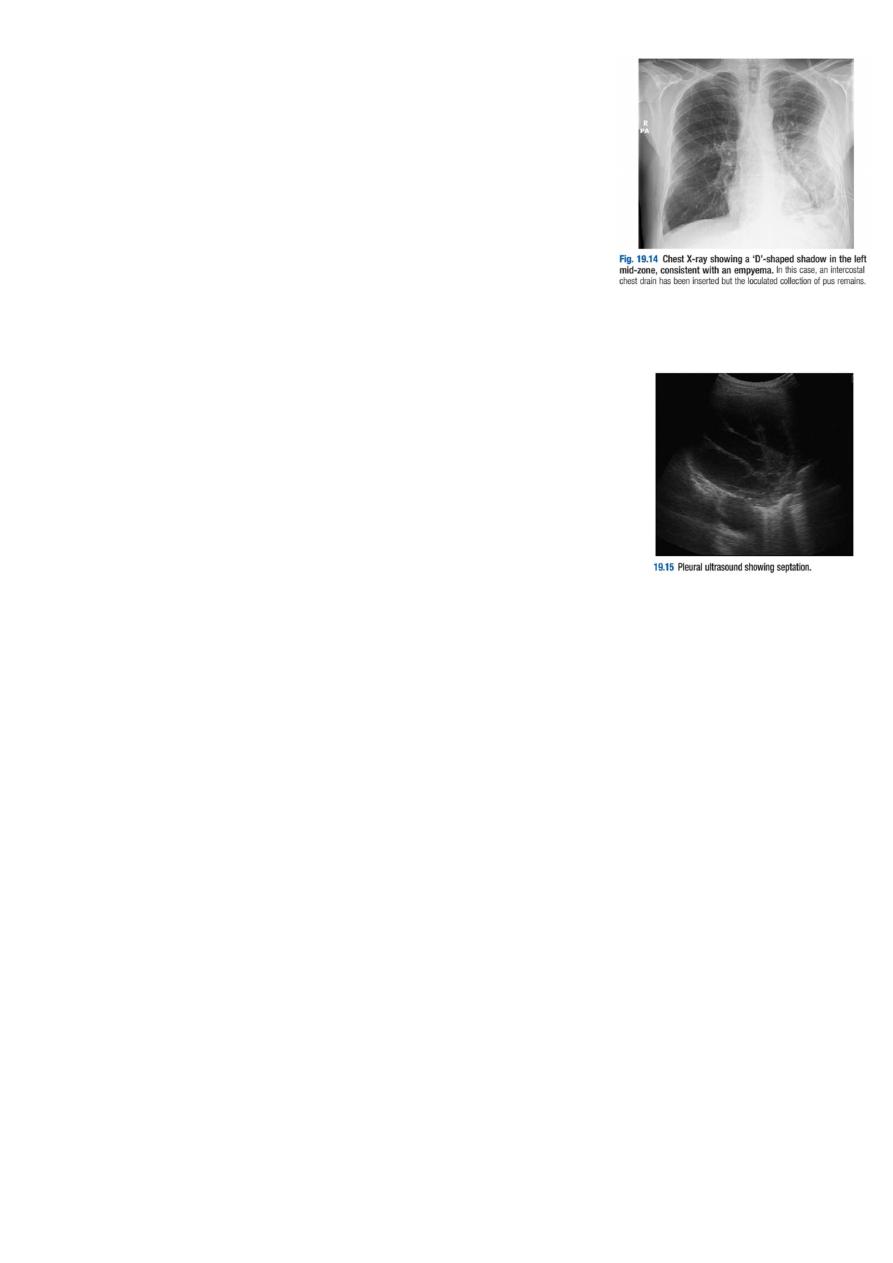

Chest X-ray appearances may be indistinguishable from those

of pleural effusion, although pleural adhesions may confine

the empyema to form a ‘D’-shaped shadow against the inside of

the chest wall .When air is present as well as pus

(pyopneumothorax), a horizontal ‘fluid level’ marks the

air/liquid interface.

Ultrasound shows the position of the fluid, the extent of pleural thickening and

whether fluid is in a single collection or multiloculated, containing

fibrin and debris .

CT provides information on the pleura, underlying lung parenchyma

and patency of the major bronchi.

Ultrasound or CT is used to identify the optimal site for aspiration, which is best

performed using a widebore needle. If the fluid is thick and turbid pus, empyema is

confirmed. Other features suggesting empyema are a fluid glucose of less than 3.3

mmol/L (60 mg/dL), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) of more than 1000 U/L, or a fluid pH

of less than 7.0 .

However, pH measurement should be avoided if pus is thick, as it damages blood gas

machines. The pus is frequently sterile on culture if antibiotics have already been given.

The distinction between tuberculous and non-tuberculous disease can be difficult and

often requires pleural biopsy, histology and culture.

Management:

An empyema will only heal if infection is eradicated and the empyema space is

obliterated, allowing apposition of the visceral and parietal pleural layers. This can only

occur if re-expansion of the compressed lung is secured at an early stage by removal of

all the pus from the pleural space. When the pus is sufficiently thin, this is most

easily achieved by the insertion of a wide-bore intercostal tube into the most dependent

part of the empyema space. If the initial aspirate reveals fluid or frank pus, or if

3

loculations are seen on ultrasound, the tube should be put on suction (−5 to -10 cm

H2O) and flushed regularly with 20 mL normal . If the organism causing the empyema

can be identified, the appropriate antibiotic should be given 2–4 weeks. Empirical

antibiotic treatment (e.g. intravenous co-amoxiclav or cefuroxime with metronidazole)

should be used if the organism is unknown.

Intrapleural fibrinolytic therapy is of no benefit.

An empyema can often be aborted if these measures are started early, but if the intercostal

tube is not providing adequate drainage – for example, when the pus is thick or

loculated, surgical intervention is required to clear the empyema cavity of pus and break

down any adhesions. Surgical ‘decortication’ of the lung may also be required if gross

thickening of the visceral pleura is preventing re-expansion of the lung. Surgery is also

necessary if a bronchopleural fistula develops.