1

Fifth stage

Surgery

Lec-2

.د

سيف

1/1/2014

Venous disorders

Deep vein thrombosis:

Etiology: exact cause is unknown but three factors contribute (Virchow's triad):

1- Changes in the vessel wall (endothelial damage)

2- Changes in the blood flow (stasis)

3- Changes in blood composition (hypercoagulation)

Clinical presentation:

1- Asymptomatic

2- Pain, redness, swelling with difficulty in walking

3- Features of pulmonary embolism may be the presenting feature in 30% of the

patients

On examination:

1. Pitting oedema of the ankle,

2. Dilated surface veins,

3. A stiff calf

4. Tenderness.

5. Homans’ sign – resistance (not pain) of the calf muscles to forcible dorsiflexion – is

not absolute and should be abandoned.

6. A low-grade pyrexia may be present

7. Signs of pulmonary embolism or pulmonary hypertension

Investigations:

1) D-dimer measurement: if levels are normal, there is no indication for further

investigations as the possibility of DVT is very remote.

2) Duplex ultrasound: loss of normal vein compressibility with filling defects in the flow

3) Ascending and descending venography; only indicated when surgical intervention is

needed.

Prophylaxis:

Patients who are being admitted for surgery can be graded as low, moderate or high risk.

Low-risk patients are young, with minor illnesses, who are to undergo operations lasting 30

min or less.

2

Moderate-risk patients are those over the age of 40 or those with a debilitating illness or

who are to undergo major surgery.

High-risk patients are those over the age of 40 who have serious accompanying medical

conditions, such as stroke or myocardial infarction, or who are undergoing major surgery

with an additional risk factor such as a past history of venous thromboembolism or known

malignant disease.

Mechanical prophylaxis include:

a. graduated elastic compression stockings

b. external pneumatic compression

c. passive foot movement (foot paddling machine)

d. simple limb elevation

Pharmaceutical prophylaxis:

a. low molecular weight heparin

b. unfractionated heparin

c. warfarin

Patients with low risk need no prophylaxis other than early postoperative mobilization.

Those with moderate risk need either pharmaceutical or mechanical prophylaxis while

those with high risk need both mechanical and pharmaceutical prophylaxis.

Medical treatment:

1) admission to hospital and bed rest

2) anticoagulant therapy (heparin and warfarin)

3) leg elevation

4) elastic compressive bandage from the toes to the upper thigh

5) patients with phlegmasia cerulea dolens need thrombolytic therapy

Surgical Treatment:

A- Venous thrombectomy: only indicated in patients with phlegmasia cerulea dolens

with contraindication to thrombolytic therapy

B- Inferior vena cava filter: indicated in patients with:

1. Recurrent thromboembolism despite adequate anticoagulation

2. Progressing thromboembolism despite adequate anticoagulation

3. Complication of anticoagulants

4. Contraindication to anticoagulants

Pulmonary embolism:

Pulmonary thromboembolism is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide

.

After an acute, major thromboembolic episode, approximately 15–20% of patients die

within 48 hours. So invasive therapy for acute pulmonary embolism should be considered in

those 15-20% of patients with fatal outcomes.

3

Pathophysiology of pulmonary embolism

The hemodynamic response to a large, sudden pulmonary embolus relates to a variety of

factors,

1. the size of the embolus,

2. the degree of obstruction that it produced in the pulmonary vascular bed,

3. the underlying function of the lung that remains perfused.

In addition to the mechanical factor of pulmonary artery obstruction, there are hormonal

factors that can increase pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) at the time of acute

pulmonary embolism due to products released from the platelets within the embolus, the

neutrophils and the blood vessel endothelial cells. Thus some patients with a relatively

small embolus may have an exaggerated response to the degree of pulmonary vascular

obstruction.

In patients without preexisting cardiac or pulmonary disease, only when the acute

pulmonary obstruction exceeds 50–60% of the pulmonary vascular bed that cardiac and

pulmonary compensatory mechanisms are overcome and cardiac output begins to fall.

With the sudden pulmonary artery obstruction, right ventricular failure occurs, which is

accompanied by systemic hypotension as the amount of blood reaching the left ventricle

decreases.

Clinical presentation:

Acute pulmonary embolism usually presents suddenly. Symptoms and signs vary with the

extent of blockage, the magnitude of humoral response, and the pre-embolus reserve of

the cardiac and pulmonary systems of the patient. The acute disease is conveniently

stratified into minor, major (submassive), or massive embolism.

For patients with minor pulmonary embolism, physical examination may reveal

tachycardia, rales, low-grade fever, and sometimes a pleural rub. Heart sounds and

systemic blood pressure are often normal. Arterial blood gases are normal. Pulmonary

angiograms typically show less than 30% occlusion of the pulmonary arterial vasculature.

Major pulmonary embolism is associated with dyspnea, tachypnea, dull chest pain,

syncope and some degree of cardiovascular changes manifested by tachycardia, mild to

moderate hypotension, and elevation of central venous pressure. In contrast to massive

pulmonary embolism, patients with major embolism are hemodynamically stable and have

adequate cardiac output. Blood gases reveal moderate hypoxia, and mild hypocarbia.

Echocardiograms may show right ventricular dilatation. Pulmonary angiograms indicate

that 30–50% of the pulmonary vasculature is blocked.

Massive pulmonary embolism is truly life-threatening and is defined as a pulmonary

embolism that causes hemodynamic instability. It is usually associated with occlusion of

more than 50% of the pulmonary vasculature, but may occur with much smaller occlusions,

particularly in patients with preexisting cardiac or pulmonary disease. Patients develop

acute dyspnea, tachypnea, tachycardia, and sweating and may lose consciousness. Both

hypotension and low cardiac output are present. Cardiac arrest may occur. Neck veins are

4

distended, and central venous pressure is elevated. Blood gases show severe hypoxia,

hypocarbia, and acidosis. Urine output falls, and peripheral pulses and perfusion are poor.

Investigations:

1) ECG: tachycardia and nonspecific changes. The major value of the electrocardiogram

is excluding a myocardial infarction.

2) X-ray may show oligemia or linear atelectasis, both of which are nonspecific findings.

3) Ventilation–perfusion (V/Q) scans may provide confirmatory evidence, but these

studies may be unreliable because pneumonia, atelectasis, previous pulmonary

emboli, and other conditions may cause a false positive result. But a negative V/Q

scan exclude the diagnosis of clinically significant pulmonary embolism.

4) Pulmonary angiograms (conventional angiography or CT angiography) provide the

most definitive diagnosis for acute pulmonary embolism as it appears as filling

defects or obstruction of pulmonary arterial branches.

5) Echocardiography both transthoracic or transesophageal may show an embolus

obstructing the main pulmonary artery but will not visualize the lobar pulmonary

arteries

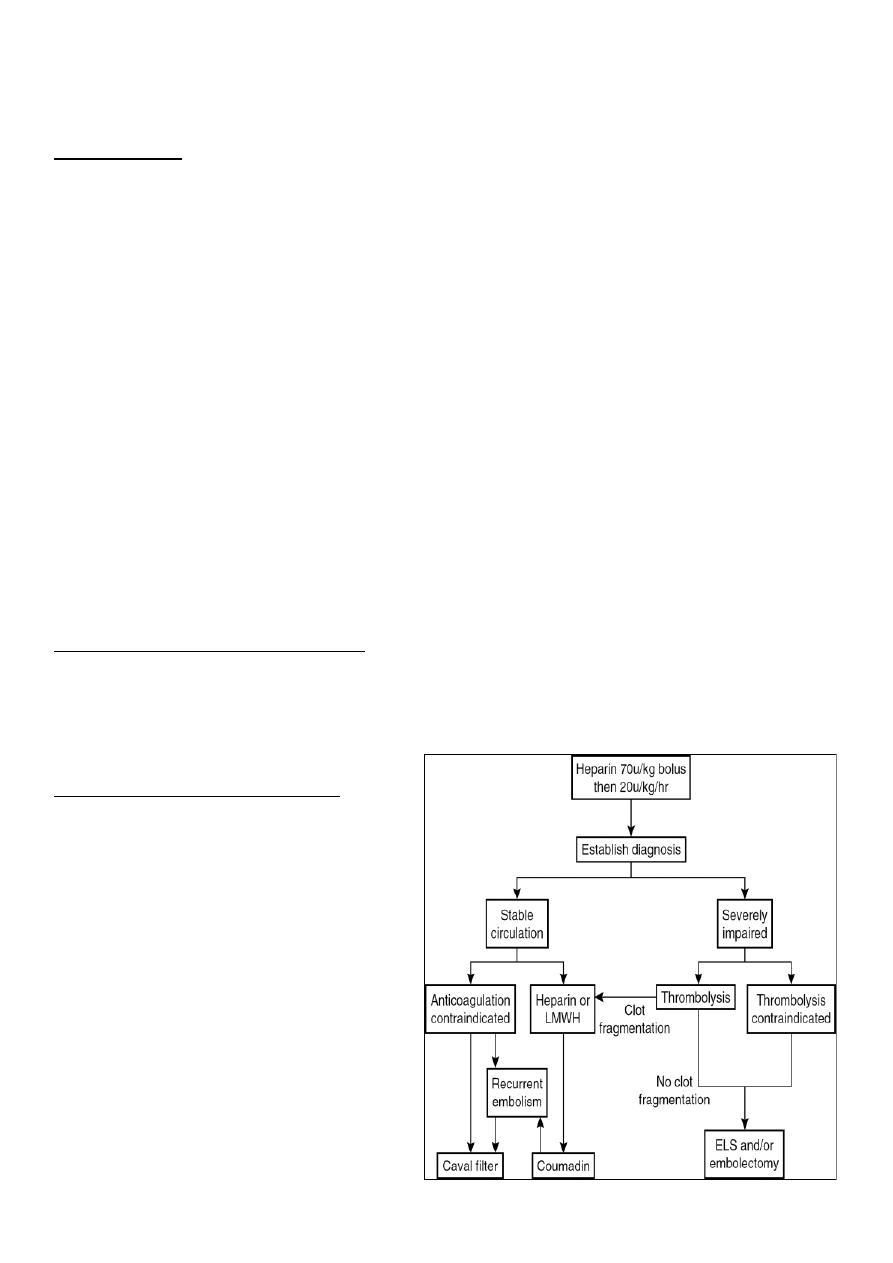

Treatment of pulmonary embolism:

The majority of patients who die of pulmonary embolism do so within 2 hours of the initial

acute event, before the diagnosis can be firmly established, and before effective therapy

can be instituted

.

Conservative medical treatment:

1)

Supplementary O

2

(usually

such patients are already in an

ICU, if not need to

immediately do so)

2)

Patients in respiratory distress

will need mechanical

ventilation

3)

Invasive cardiac monitoring

through both arterial line and

central venous line for

estimation of cardiac output

and serial arterial blood gas

measurement.

5

4)

Pharmaceutical myocardial support

(positive inotropic agents) and sometimes

even mechanical myocardial support (like

intra-aortic balloon pump).

5)

Immediate anticoagulation with i.v. heparin preferably by infusion technique.

6)

Consider thrombolysis in patients with major-to-massive pulmonary embolism. Still,

thrombolytic therapy is contraindicated in patients with fresh surgical wounds,

anemia, recent stroke, peptic ulcer, or bleeding dyscrasias.

Surgical treatment:

Emergency pulmonary embolectomy is indicated for suitable patients with life-threatening

circulatory insufficiency, where the diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism has been

established.

Indications for acute surgical intervention include the following:

(1)

Critical hemodynamic instability or severe pulmonary compromise

(2)

Patients in whom thrombolytic or anticoagulation therapy is absolutely

contraindicated,

(3)

The presence of a large clot trapped within the right atrium or ventricle

Pulmonary embolectomy is done through a median sternotomy with total anticoagulation, a

cardiopulmonary bypass machine, and mild to moderate hypothermia. The main pulmonary

artery is opened and the embolus with its propagating thrombus removed by forceps,

suction, and embolectomy catheter. After which the patient is weaned off the

cardiopulmonary machine and the chest is closed. Dramatic improvement in his

hemodynamics is noted immediately.