1

Fifth stage

Pediatric

Lec-7

.د

أ

ثل

1/1/2016

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease GERD

Objective :

A/ Gastresophageal reflux

– To define GER

– To know its types & pathology.

– To diagnose a case.

– To manage it.

B/ Pyloric stenosis

– To know its pathology.

– To distinguish its manifestations

– To diagnose a case.

– To manage it.

C/ Intussusception

– To define it.

– To know its epidemiology.

– To know the etiology &pathogenesis.

– To distinguish its manifestations

– To diagnose a case.

– To manage it.

– What is the prognosis?

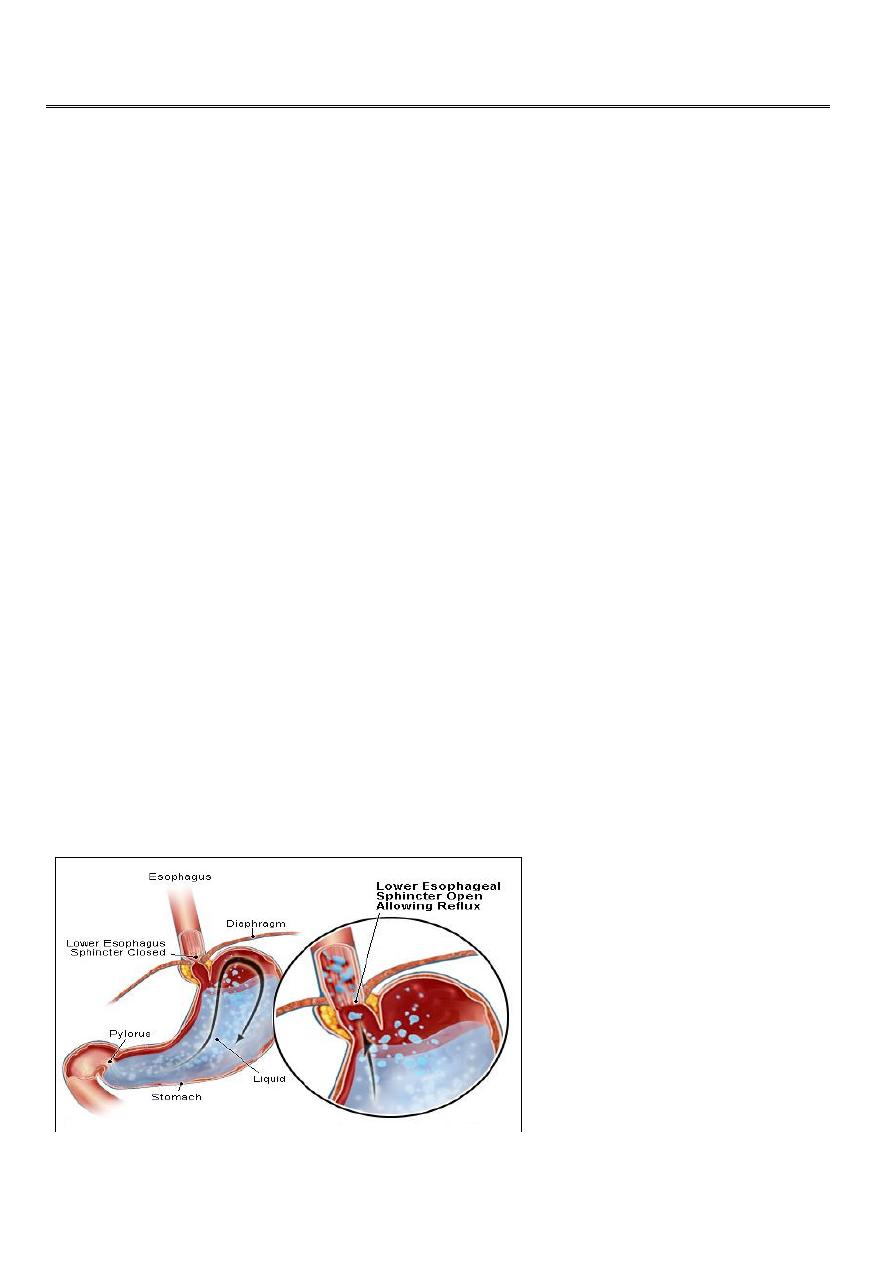

• GER is defined as the effortless retrograde movement of gastric contents upward into

the esophagus .

• GERD is the most common esophageal disorder in children of all ages.

• Although occasional episodes of reflux are physiologic, exemplified by the regurgitation

of normal infants, the phenomenon becomes pathologic (GERD) in children who have

episodes that are more frequent or persistent, and thus produce esophagitis or

esophageal symptoms, or in those who have respiratory sequelae.

Physiologic GER

• spitting up is normal in infants younger than 12 months old.

• NATURAL HISTORY :

2

– reflux becomes evident in the 1st few months of life, nearly half of all infants

are reported to spit up at 2 months of age.

– peaks at ≈4 mo

– resolves in most by 12 mo and nearly all by 24 mo.

Criteria for physiologic GER

• Normal weight gain

• Have no signs of respiratory or peptic complications.

• The absence of bloody or bilious vomiting

Factors involved in physiologic GER include

• Liquid diet

• Frequent, relatively large volume feedings

• Horizontal body position

• Short, narrow esophagus

• Immature LES.

• Small, noncompliant stomach

As infants grow:

– They spend more time upright

– Develop a longer and larger diameter esophagus

– Have a larger and more compliant stomach

– Eat more solid foods

– Experience lower caloric needs per unit of body weight

As a result, most infants stop spitting up by 9 to 12 months of age.

Pathologic GER

• After 18 months of age or

• If there are complications in younger infants such as

– Esophagitis,

• This may present clinically as blood in the vomit or

• More insidiously with the development of anemia or stricture.

• Older children may complain of heartburn with reflux

• While smaller infants may develop feeding difficulties due to esophageal

discomfort

– Respiratory symptoms :

wheezing, aspiration pneumonia, hoarse voice chronic cough, or apneic spells.

– Failure to thrive

Diagnosis:

• A clinical diagnosis is often sufficient in children with classic effortless regurgitation

and no complications.

• Diagnostic studies are indicated for pathological GER

– A barium upper GI series: to exclude obstruction such as pyloric stenosis,

hiatus hernia ,gastric antral web, duodenal stenosis, annular pancreas, and

3

malrotation. Because of the brief nature of the examination, a negative barium

study does not rule out GER.

– 24-hour esophageal probe : Data typically are gathered for 24 hours,

following which the number and temporal pattern of acid reflux events are

analyzed.

– Esophageal impedance monitoring, which records the migration of electrolyte

rich gastric fluid in the esophagus.

– Endoscopy is useful to rule out esophagitis, esophageal stricture, and anatomic

abnormalities. .

Treatment

A. Treatment of uncomplicated GER

In otherwise healthy young infants ("well-nourished, happy spitters"), The mother

should be reassured and advised of simple measures to help with the problem. such as:

• Positional therapy: supine upright in seat, elevate head of crib with head up is

helpful,

• Towel on caregiver's shoulder Cheap, effective. Useful only for physiologic reflux

• Thickened feedings :Reduces number of episodes, enhances nutrition,thickening of

formula with a tablespoon of rice cereal per ounce of formula results in fewer

regurgitation episodes, greater caloric density (30kcal/oz), and reduced crying time,

• Smaller, more frequent feedings :Can help some. Be careful not to underfeed child

• If there is a strong family history of atopy or signs of eczema the introduction of a

hypoallergenic feed may be indicated.

B. Treatment of complicated GER:

✎ Medical Therapy

– Proton-pump inhibitor (PPIs; omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole,

rabeprazole, and esomeprazole) , effective medical therapy for heartburn and

esophagitis

– H2 receptor antagonist(H2RAs :cimetidine, famotidine, nizatidine, and

ranitidine) reduces heartburn, less effective for healing esophagitis

– Metoclopramide, enhances stomach emptying and LES tone. Real benefit is

often minimal.

✎ Surgical Therapy: for

• Esophagitis unresponsive to medical therapy.

• Esophageal stricture

• Apneic spells or chronic pulmonary disease unresponsive to 2–3 months of medical

therapy.

• Feeding jejunostomy, useful in child requiring tube feeds. Delivering feeds

downstream eliminates GERD

• Nissen or other fundoplication procedure for life-threatening or medically

unresponsive cases. Fundoplication procedures may be performed as open

operations, by laparoscopy, or by endoluminal (gastroplication) techniques.

4

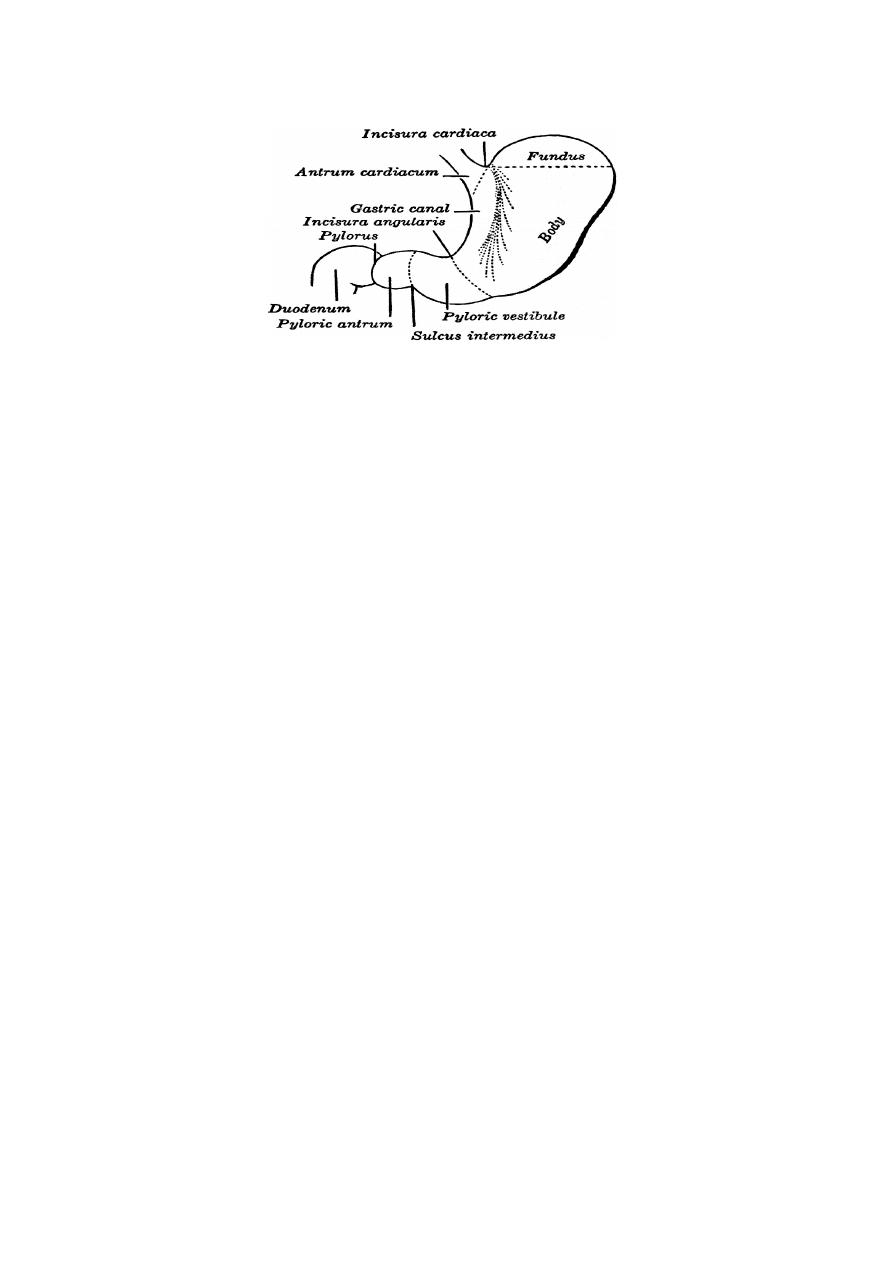

PYLORiC STENOSiS

• Pyloric stenosis is an acquired condition caused by hypertrophy and spasm of the

pyloric muscle, resulting in gastric outlet obstruction.

• Epidemiology :

– It occurs in 6 to 8 per 1000 live births

– 5:1 male predominance

– more common in first-born children.

Clinical Manifestations

1. Vomiting:

Nonbilious vomiting usually begins between ages 2 and 4 weeks and rapidly

becomes projectile after every feeding; or it may be intermittent

Vomiting in pyloric stenosis differs from spitting up(gastroesophageal reflux)

because of its extremely forceful and often projectile nature.

The vomited material never contains bile because the gastric outlet obstruction is

proximal to the duodenum. This feature differentiates pyloric stenosis from most

other obstructive lesions of early childhood.

After vomiting, the infant is hungry and wants to feed again. Affected infants are

ravenously hungry early in the course of the illness, but become more lethargic

with increasing malnutrition and dehydration.

As vomiting continues, a progressive loss of fluid, hydrogen ion, and chloride

leads to hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis.

2. Constipation: usually occur.

3. Jaundice :

associated with a decreased level of glucuronyl transferase is seen in

approximately 5% of affected infants. The indirect hyperbilirubinemia usually

resolves promptly after relief of the obstruction.

5

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is established by

• palpating the pyloric mass:

– The mass is firm, movable, approximately 2 cm in length, olive shaped, hard,

best palpated from the left side, and located above and to the right of the

umbilicus in the mid epigastrium beneath the liver edge.

– After the infant vomits, the abdominal musculature is more relaxed and the

“olive” easier to palpate.

• peristaltic wave: after feeding, there may be a visible gastric peristaltic wave that

progresses across the abdomen .

The diagnosis can be established clinically 60–80% of the time by an experienced

examiner.

• Ultrasound examination: confirms the diagnosis in the majority of cases, allowing an

earlier diagnosis .pyloric thickness greater than 4 mm or an overall pyloric length

greater than 14 mm. Ultrasonography has a sensitivity of approximately 95%.

• Barium studies :

– Elongated pyloric channel

– A bulge of the pyloric muscle into the antrum (shoulder sign),

– Parallel streaks of barium seen in the narrowed channel, producing a (double

tract sign)

The preoperative treatment :

Before surgery, dehydration and hypochloremic alkalosis must be corrected, generally with

an initial normal saline fluid bolus followed by infusions of half-normal saline containing 5%

dextrose and potassium chloride when urine output is observed.

Fluid therapy should be continued until the infant is rehydrated and the serum bicarbonate

concentration is <30 mEq/dL, which implies that the alkalosis has been corrected.

Correction of the alkalosis is essential to prevent postoperative apnea, which may be

associated with anesthesia.

Surgical management:

The surgical procedure of choice is the ramstedt pyloromyotomy. The procedure is

performed through a short transverse incision or laparoscopically. The underlying pyloric

mass is split without cutting the mucosa, and the incision is closed

The surgical treatment of pyloric stenosis is curative, with an operative mortality of 0–

0.5%.

6

Intussusception

Intussusception is the "telescoping" of a segment of proximal bowel (the intussusceptum)

into downstream bowel (the intussuscipiens).

Epidemiology :

• It is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction between 3 mo and 6 yr of age.

Sixty percent of patients are younger than 1 yr, and 80% of the cases occur before 24

mo; it is rare in neonates.

• The incidence varies from 1– 4 in 1,000 live births.

• The male:female ratio is 4:1.

Etiology:

• Viral-induced lymphoid hyperplasia may produce a lead point in these children. In

infants the lead point is presumed to be an enlarged Peyer’s patch, the lymphoid

tissue presumably responding to a viral stimulant. This becomes the apex of the

intussusception which then proceeds for a variable distance into the colon

• Correlation with adenovirus infections has been noted, and the condition may

complicate otitis media, gastroenteritis, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, or upper

respiratory tract infections.

• In older children(> 2years) the proportion of cases of patients caused by a

pathologic lead point increases. the lead point may be

Intestinal polyp,

Meckel diverticulum,

Neurofibroma,

Hemangioma, or malignant conditions such as lymphoma.

Intussusception may complicate mucosal hemorrhage as in henoch-schönlein

purpura or hemophilia.

PATHOLOGY

• Intussusceptions are most often ileocolic, less commonly cecocolic, and rarely

exclusively ileal. Very rarely, the appendix forms the apex of an intussusception.

• The upper portion of bowel, the intussusceptum, invaginates into the lower, the

intussuscipiens, pulling its mesentery along with it into the enveloping loop.

• Constriction of the mesentery obstructs venous return; engorgement of the

intussusceptum follows, with edema, and bleeding from the mucosa leads to a

bloody stool, sometimes containing mucus.

7

• Most intussusceptions do not strangulate the bowel within the 1st 24 hr but may

later eventuate in intestinal gangrene and shock.

Clinical Manifestations

• In typical cases there is sudden onset, in a previously well child, of severe paroxysmal

colicky pain that recurs at frequent intervals ,with legs and knees flexed and loud

cries. pallor with a colicky pattern occurring every 15 to 20 minutes.

• The infant may initially be comfortable and play normally between the paroxysms of

pain; but if the intussusception is not reduced, the infant becomes progressively

weaker and lethargic.. Eventually a shocklike state may develop with fever.

• The pulse becomes weak and thready, the respirations become shallow and grunting,

and the pain may be manifested only by moaning sounds.

• Vomiting occurs in most cases and is usually more frequent early. In the later phase,

the vomitus becomes bile stained.

• Stools of normal appearance may be evacuated during the first few hours of

symptoms. After this time, fecal excretions are small or more often do not occur and

little or no flatus is passed. Blood generally is passed in the first 12hr but at times not

for 1–2 days and infrequently not at all; 60% of infants pass a stool containing red

blood and mucus, the currant jelly stool.

• Palpation of the abdomen usually reveals a slightly tender sausage-shaped mass,

sometimes ill defined, most often in the right upper abdomen,. About 30% of

patients do not have a palpable mass.

• P.R: The presence of bloody mucus on the finger as it is withdrawn after rectal

examination supports the diagnosis of intussusception.

• Abdominal distention and tenderness develop as intestinal obstruction becomes

more acute.

• On rare occasions, the advancing intestine prolapses through the anus.

Diagnosis:

• The clinical history and physical findings are usually sufficiently typical for diagnosis.

• Laboratory and Imaging Studies :

– Plain abdominal radiographs may show a density in the area of the intussusception.

– Ultrasonography is a sensitive diagnostic tool in the diagnosis of intussusception.

– A barium enema shows: coiled-spring sign

Treatment

• Admission:

8

• Therapy must begin with placement of an IV fluid and a nasogastric tube

• Surgical consultation should be obtained early .

Reduction of an acute intussusception is an emergency procedure and performed

immediately after diagnosis with preparation for possible surgery. Reduction in the theater

either by :

– Nonoperative reduction

• pneumatic reduction

• Hydrostatic reduction

If reduction is not complete, emergency surgery is required.

– Surgery

• The surgeon attempts gentle manual reduction,

• But may need to resect the involved bowel after failed reduction because of severe

edema, perforation, a pathologic lead point (polyp, Meckel diverticulum), or

necrosis

PROGNOSIS

Untreated intussusception in infants is almost always fatal; the chances of recovery are

directly related to the duration of intussusception before reduction.

Spontaneous reduction during preparation for operation is not uncommon.

The recurrence rate after reduction of intussusceptions is ≈10%, and after surgical

reduction it is 2–5%; none has recurred after surgical resection .Corticosteroids may reduce

the frequency of recurrent intussusception.