CALCULUS II

Parametric Equations and Polar Coordinates

Paul Dawkins

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

i

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Table of Contents

Preface ............................................................................................................................................ ii

Parametric Equations and Polar Coordinates ............................................................................ 3

Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 3

Parametric Equations and Curves .............................................................................................................. 5

Tangents with Parametric Equations .........................................................................................................25

Area with Parametric Equations ................................................................................................................32

Arc Length with Parametric Equations .....................................................................................................35

Surface Area with Parametric Equations...................................................................................................39

Polar Coordinates ......................................................................................................................................41

Tangents with Polar Coordinates ..............................................................................................................51

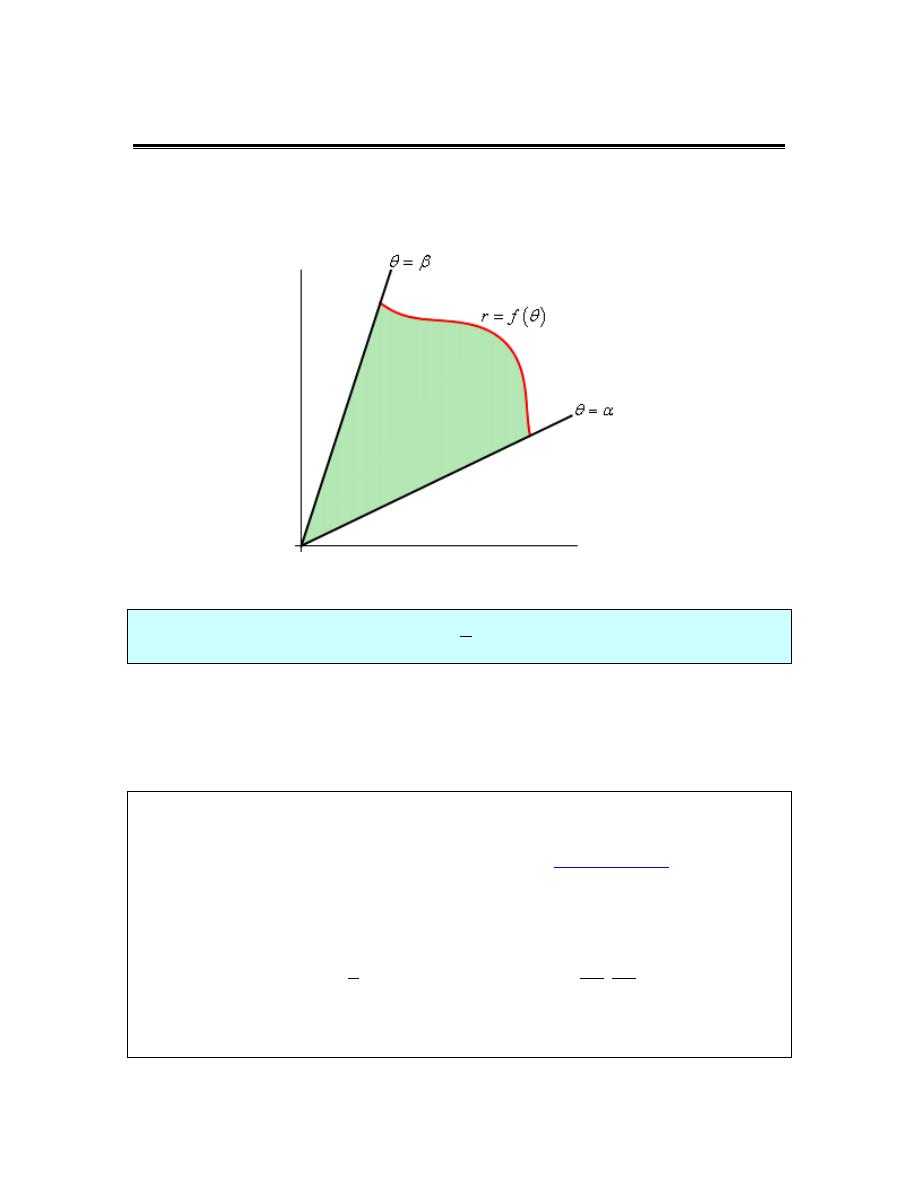

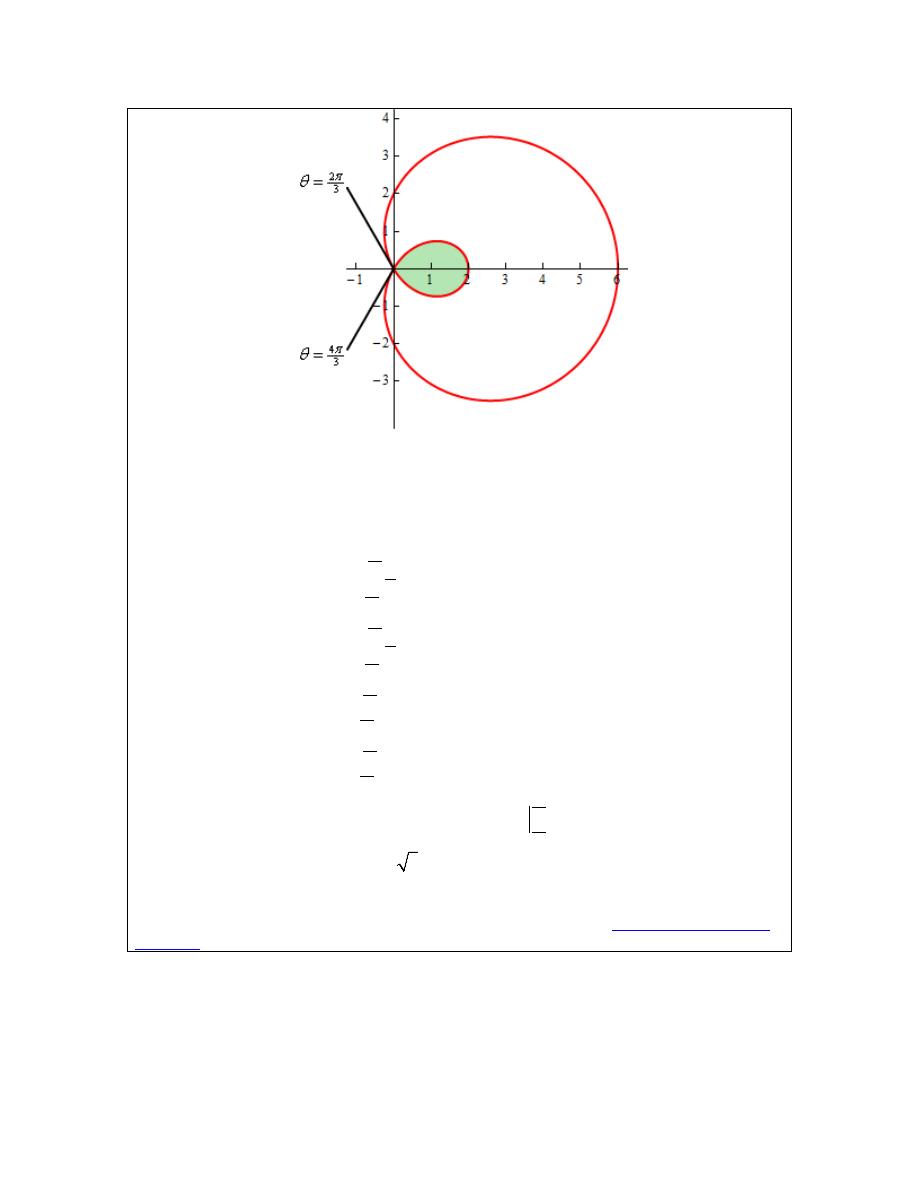

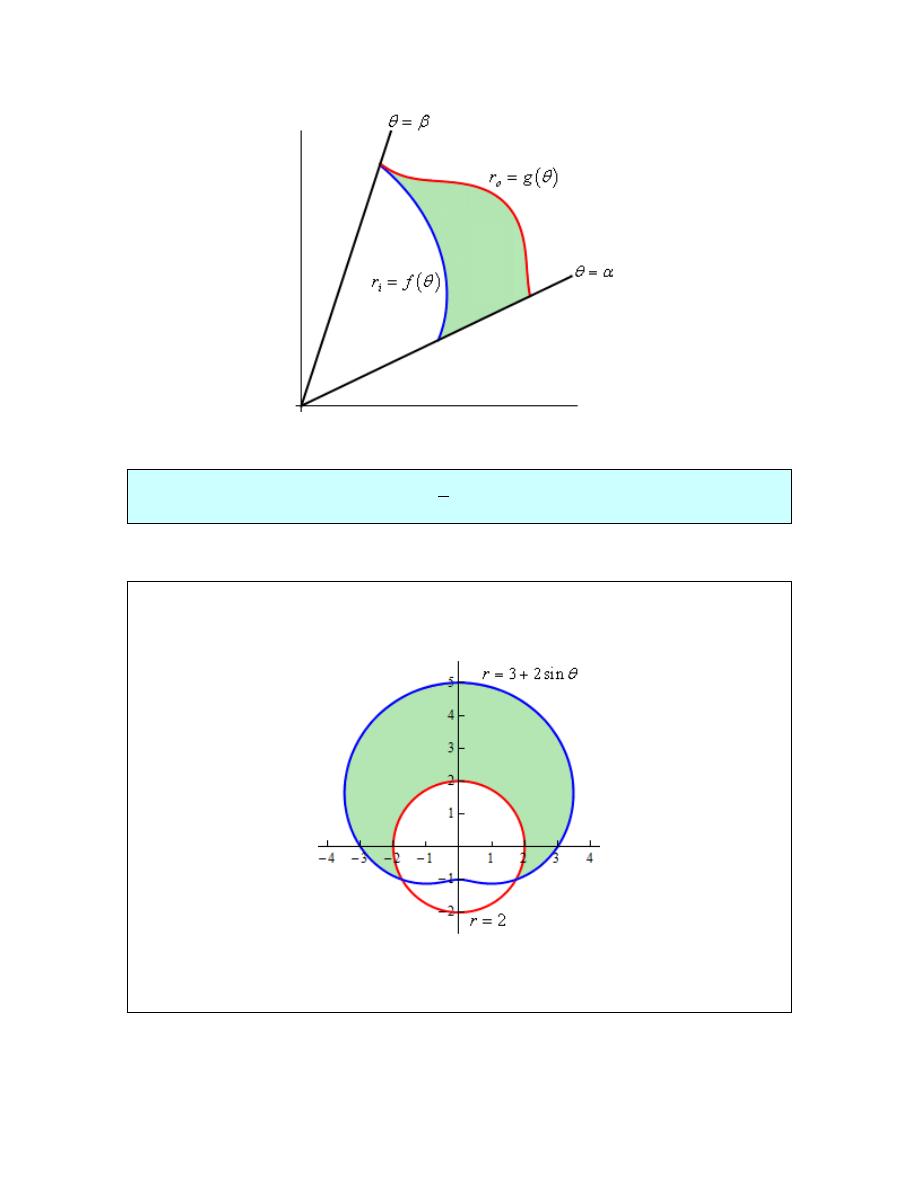

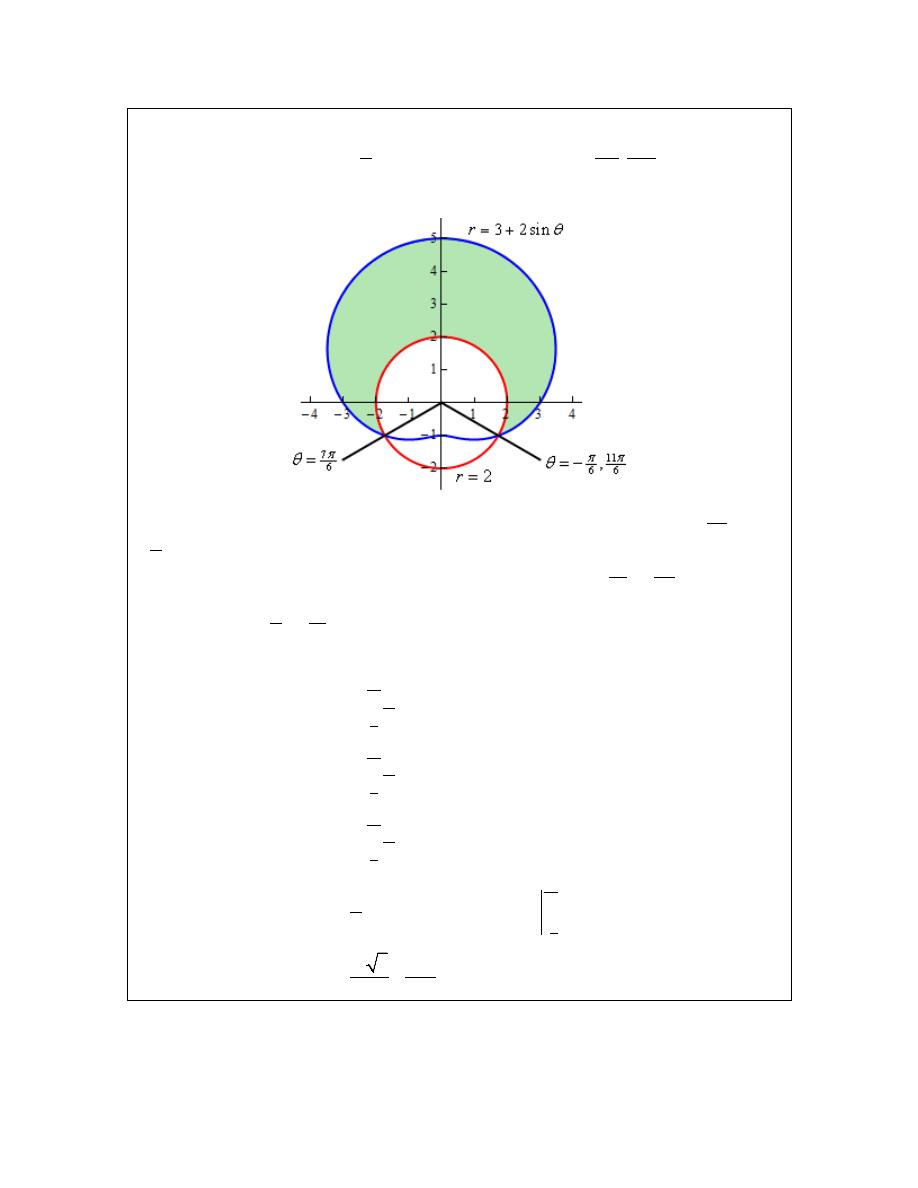

Area with Polar Coordinates .....................................................................................................................53

Arc Length with Polar Coordinates ...........................................................................................................60

Surface Area with Polar Coordinates ........................................................................................................62

Arc Length and Surface Area Revisited ....................................................................................................63

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

ii

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Preface

Here are my online notes for my Calculus II course that I teach here at Lamar University.

Despite the fact that these are my “class notes”, they should be accessible to anyone wanting to

learn Calculus II or needing a refresher in some of the topics from the class.

These notes do assume that the reader has a good working knowledge of Calculus I topics

including limits, derivatives and basic integration and integration by substitution.

Calculus II tends to be a very difficult course for many students. There are many reasons for this.

The first reason is that this course does require that you have a very good working knowledge of

Calculus I. The Calculus I portion of many of the problems tends to be skipped and left to the

student to verify or fill in the details. If you don’t have good Calculus I skills, and you are

constantly getting stuck on the Calculus I portion of the problem, you will find this course very

difficult to complete.

The second, and probably larger, reason many students have difficulty with Calculus II is that you

will be asked to truly think in this class. That is not meant to insult anyone; it is simply an

acknowledgment that you can’t just memorize a bunch of formulas and expect to pass the course

as you can do in many math classes. There are formulas in this class that you will need to know,

but they tend to be fairly general. You will need to understand them, how they work, and more

importantly whether they can be used or not. As an example, the first topic we will look at is

Integration by Parts. The integration by parts formula is very easy to remember. However, just

because you’ve got it memorized doesn’t mean that you can use it. You’ll need to be able to look

at an integral and realize that integration by parts can be used (which isn’t always obvious) and

then decide which portions of the integral correspond to the parts in the formula (again, not

always obvious).

Finally, many of the problems in this course will have multiple solution techniques and so you’ll

need to be able to identify all the possible techniques and then decide which will be the easiest

technique to use.

So, with all that out of the way let me also get a couple of warnings out of the way to my students

who may be here to get a copy of what happened on a day that you missed.

1. Because I wanted to make this a fairly complete set of notes for anyone wanting to learn

calculus I have included some material that I do not usually have time to cover in class

and because this changes from semester to semester it is not noted here. You will need to

find one of your fellow class mates to see if there is something in these notes that wasn’t

covered in class.

2. In general I try to work problems in class that are different from my notes. However,

with Calculus II many of the problems are difficult to make up on the spur of the moment

and so in this class my class work will follow these notes fairly close as far as worked

problems go. With that being said I will, on occasion, work problems off the top of my

head when I can to provide more examples than just those in my notes. Also, I often

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

iii

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

don’t have time in class to work all of the problems in the notes and so you will find that

some sections contain problems that weren’t worked in class due to time restrictions.

3. Sometimes questions in class will lead down paths that are not covered here. I try to

anticipate as many of the questions as possible in writing these up, but the reality is that I

can’t anticipate all the questions. Sometimes a very good question gets asked in class

that leads to insights that I’ve not included here. You should always talk to someone who

was in class on the day you missed and compare these notes to their notes and see what

the differences are.

4. This is somewhat related to the previous three items, but is important enough to merit its

own item. THESE NOTES ARE NOT A SUBSTITUTE FOR ATTENDING CLASS!!

Using these notes as a substitute for class is liable to get you in trouble. As already noted

not everything in these notes is covered in class and often material or insights not in these

notes is covered in class.

Parametric Equations and Polar Coordinates

Introduction

In this section we will be looking at parametric equations and polar coordinates. While the two

subjects don’t appear to have that much in common on the surface we will see that several of the

topics in polar coordinates can be done in terms of parametric equations and so in that sense they

make a good match in this chapter

We will also be looking at how to do many of the standard calculus topics such as tangents and

area in terms of parametric equations and polar coordinates.

Here is a list of topics that we’ll be covering in this chapter.

Parametric Equations and Curves

– An introduction to parametric equations and parametric

curves (i.e. graphs of parametric equations)

Tangents with Parametric Equations

– Finding tangent lines to parametric curves.

Area with Parametric Equations

– Finding the area under a parametric curve.

Arc Length with Parametric Equations

– Determining the length of a parametric curve.

Surface Area with Parametric Equations

– Here we will determine the surface area of a solid

obtained by rotating a parametric curve about an axis.

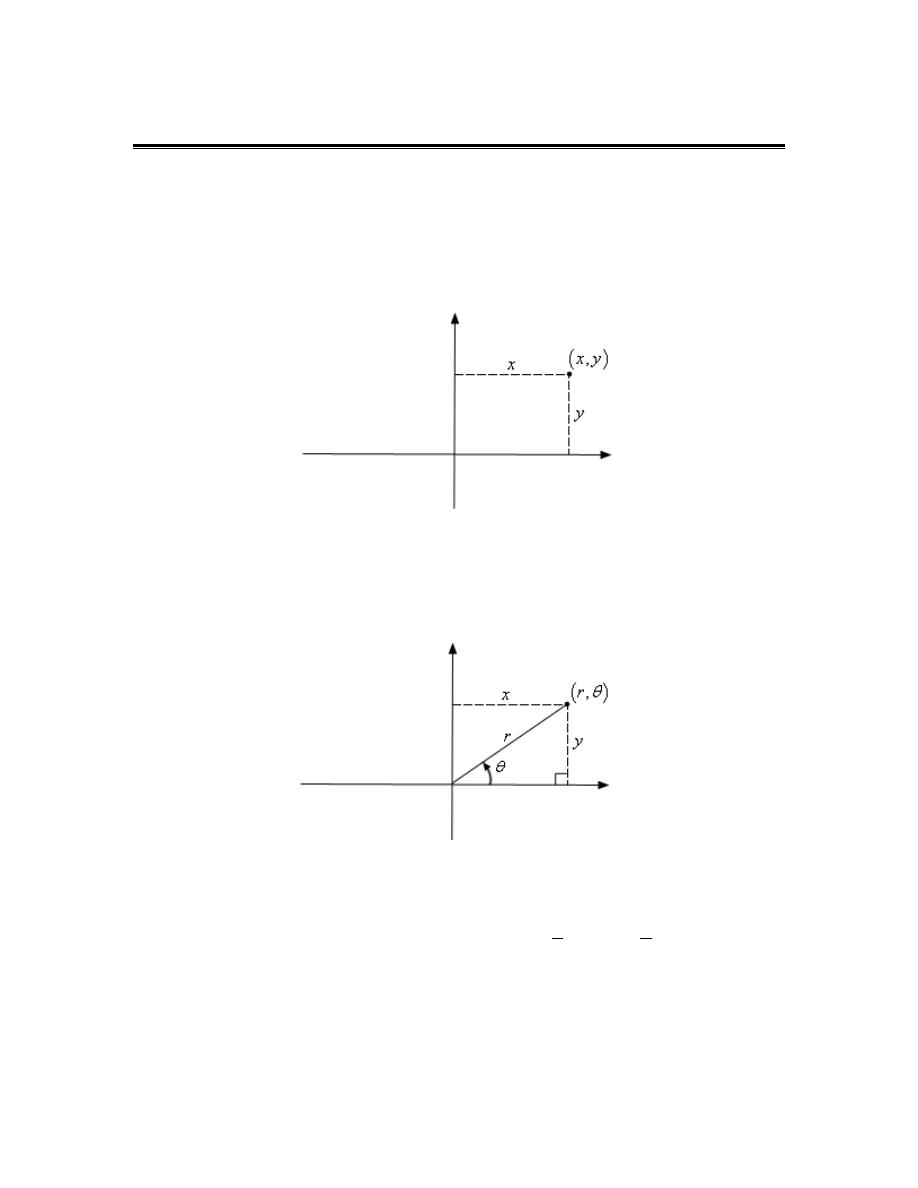

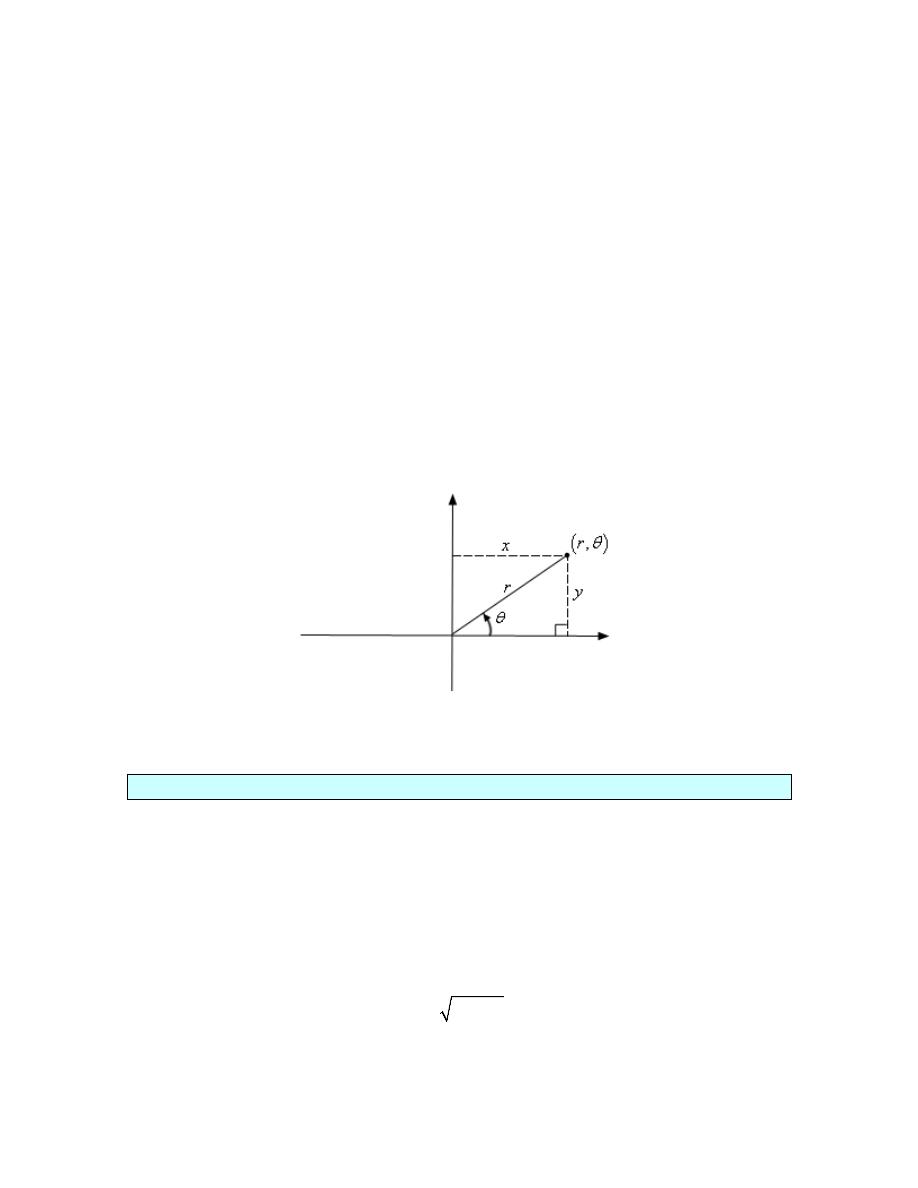

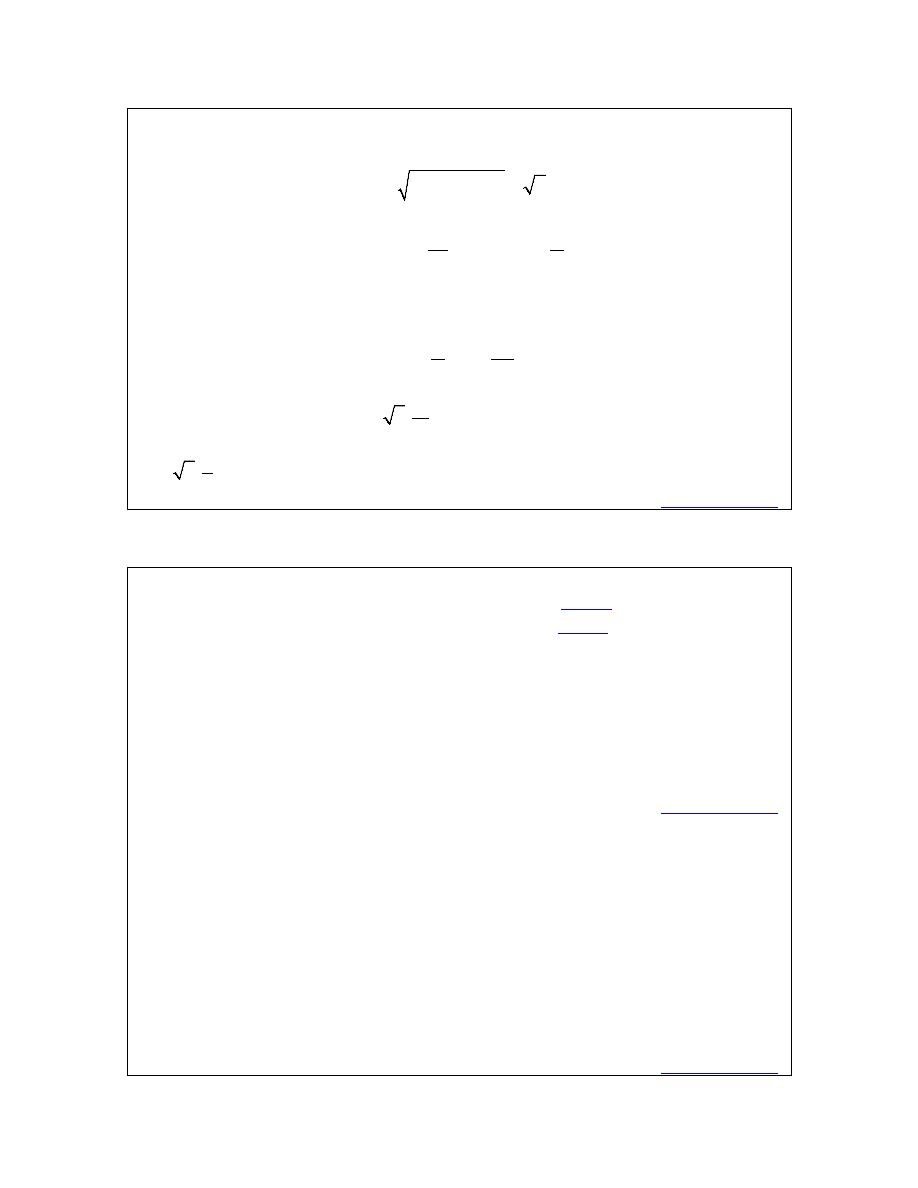

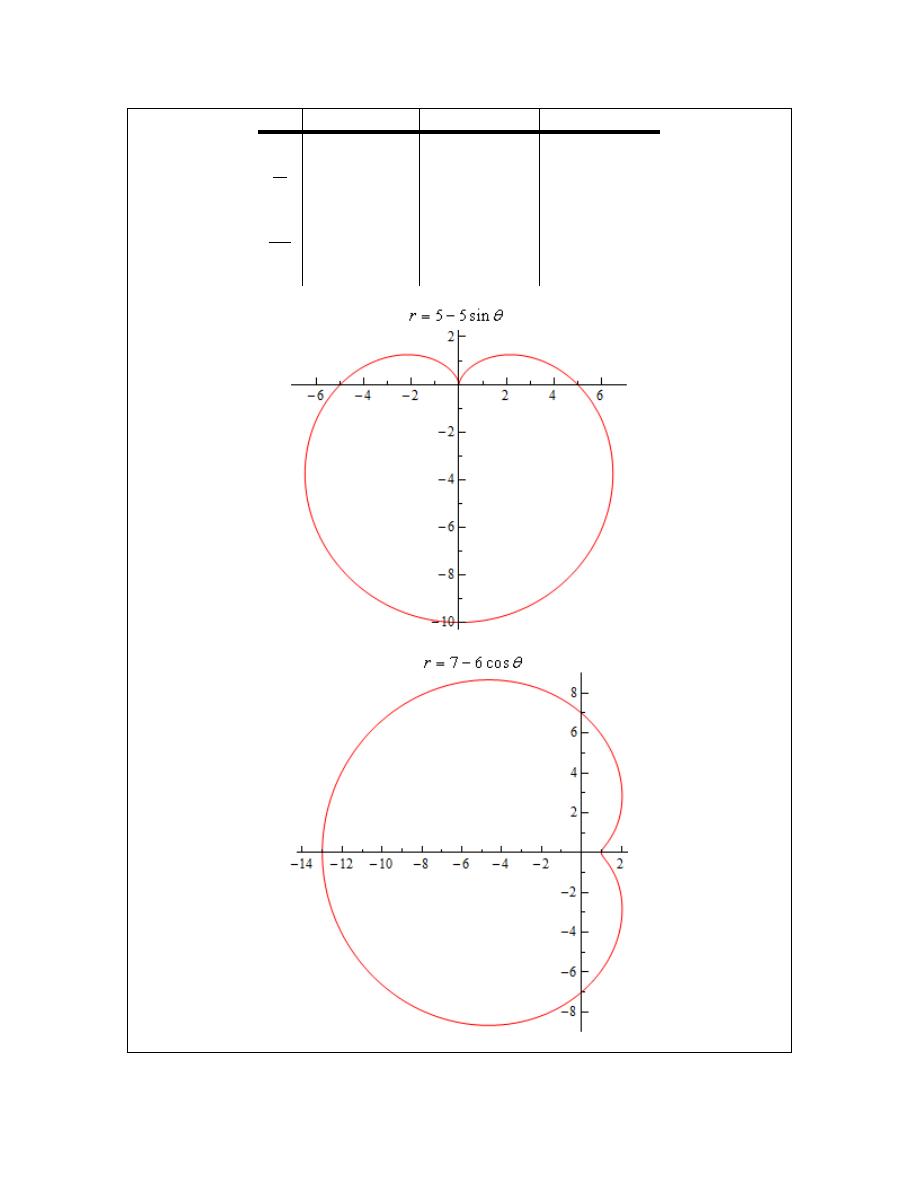

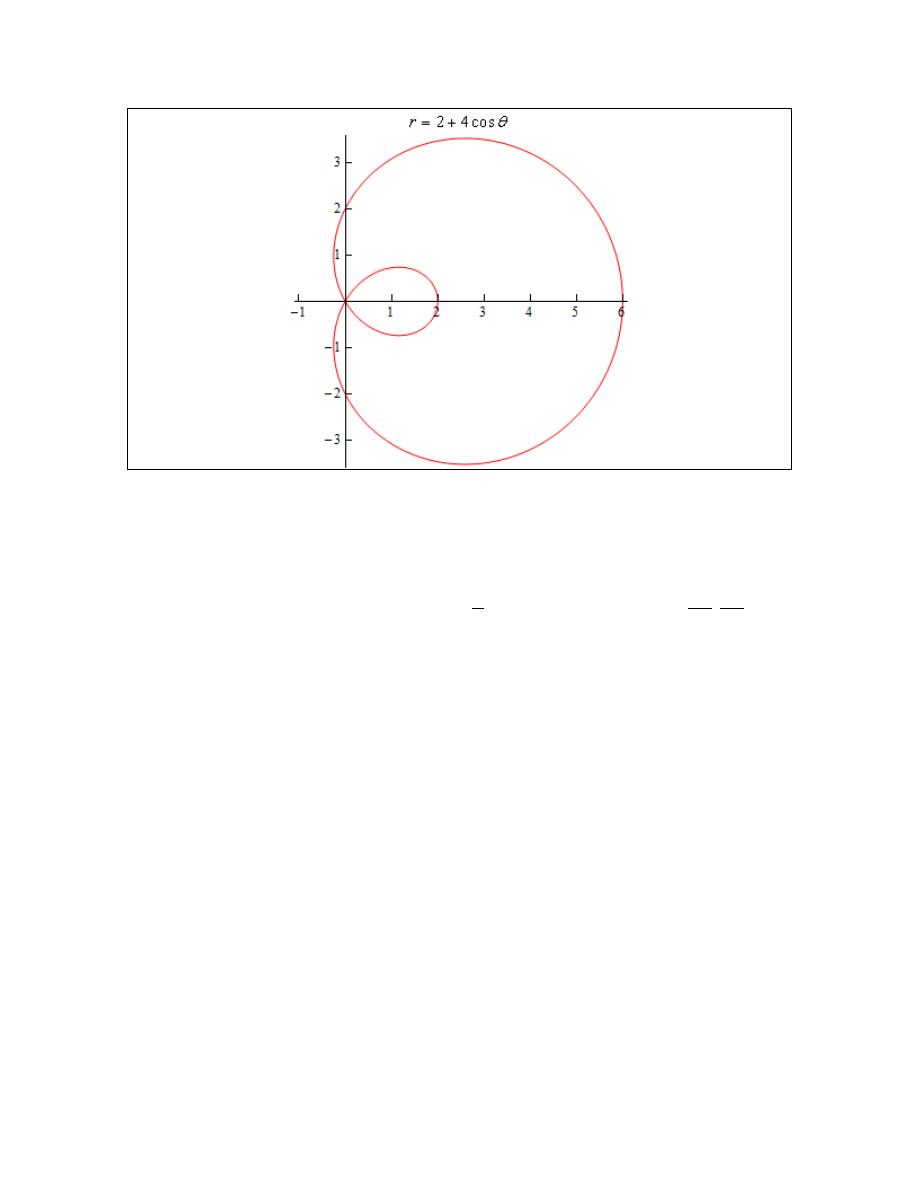

Polar Coordinates

– We’ll introduce polar coordinates in this section. We’ll look at converting

between polar coordinates and Cartesian coordinates as well as some basic graphs in polar

coordinates.

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

4

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

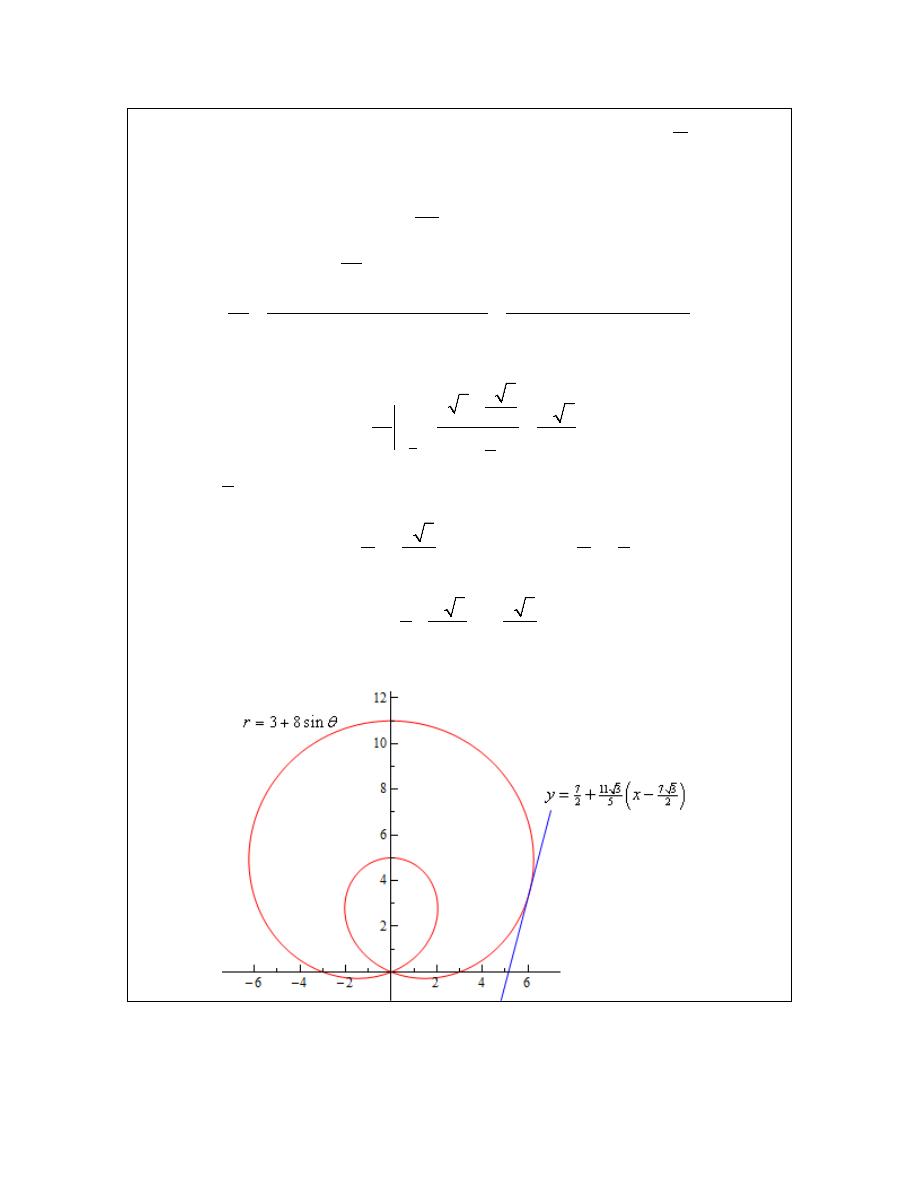

Tangents with Polar Coordinates

– Finding tangent lines of polar curves.

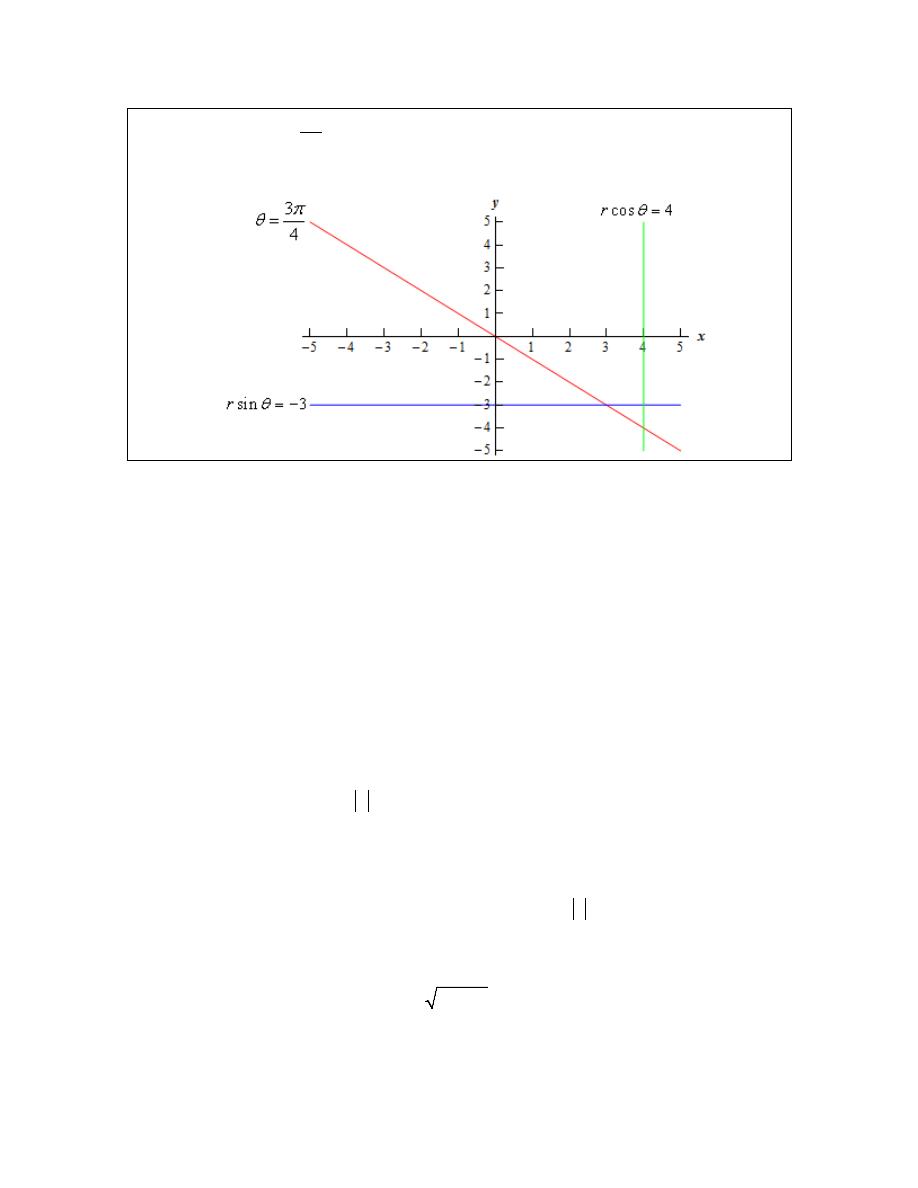

Area with Polar Coordinates

– Finding the area enclosed by a polar curve.

Arc Length with Polar Coordinates

– Determining the length of a polar curve.

Surface Area with Polar Coordinates

– Here we will determine the surface area of a solid

obtained by rotating a polar curve about an axis.

Arc Length and Surface Area Revisited

– In this section we will summarize all the arc length

and surface area formulas from the last two chapters.

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

5

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Parametric Equations and Curves

To this point (in both Calculus I and Calculus II) we’ve looked almost exclusively at functions in

the form

( )

y

f x

=

or

( )

x

h y

=

and almost all of the formulas that we’ve developed require

that functions be in one of these two forms. The problem is that not all curves or equations that

we’d like to look at fall easily into this form.

Take, for example, a circle. It is easy enough to write down the equation of a circle centered at

the origin with radius r.

2

2

2

x

y

r

+

=

However, we will never be able to write the equation of a circle down as a single equation in

either of the forms above. Sure we can solve for x or y as the following two formulas show

2

2

2

2

y

r

x

x

r

y

= ±

−

= ±

−

but there are in fact two functions in each of these. Each formula gives a portion of the circle.

( )

(

)

(

)

(

)

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

top

right side

bottom

left side

y

r

x

x

r

y

y

r

x

x

r

y

=

−

=

−

= −

−

= −

−

Unfortunately we usually are working on the whole circle, or simply can’t say that we’re going to

be working only on one portion of it. Even if we can narrow things down to only one of these

portions the function is still often fairly unpleasant to work with.

There are also a great many curves out there that we can’t even write down as a single equation in

terms of only x and y. So, to deal with some of these problems we introduce parametric

equations. Instead of defining y in terms of x (

( )

y

f x

=

) or x in terms of y (

( )

x

h y

=

) we

define both x and y in terms of a third variable called a parameter as follows,

( )

( )

x

f t

y

g t

=

=

This third variable is usually denoted by t (as we did here) but doesn’t have to be of course.

Sometimes we will restrict the values of t that we’ll use and at other times we won’t. This will

often be dependent on the problem and just what we are attempting to do.

Each value of t defines a point

( )

( ) ( )

(

)

,

,

x y

f t

g t

=

that we can plot. The collection of points

that we get by letting t be all possible values is the graph of the parametric equations and is called

the parametric curve.

To help visualize just what a parametric curve is pretend that we have a big tank of water that is

in constant motion and we drop a ping pong ball into the tank. The point

( )

( ) ( )

(

)

,

,

x y

f t

g t

=

will then represent the location of the ping pong ball in the tank at time t and the parametric curve

will be a trace of all the locations of the ping pong ball. Note that this is not always a correct

analogy but it is useful initially to help visualize just what a parametric curve is.

Sketching a parametric curve is not always an easy thing to do. Let’s take a look at an example to

see one way of sketching a parametric curve. This example will also illustrate why this method is

usually not the best.

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

6

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

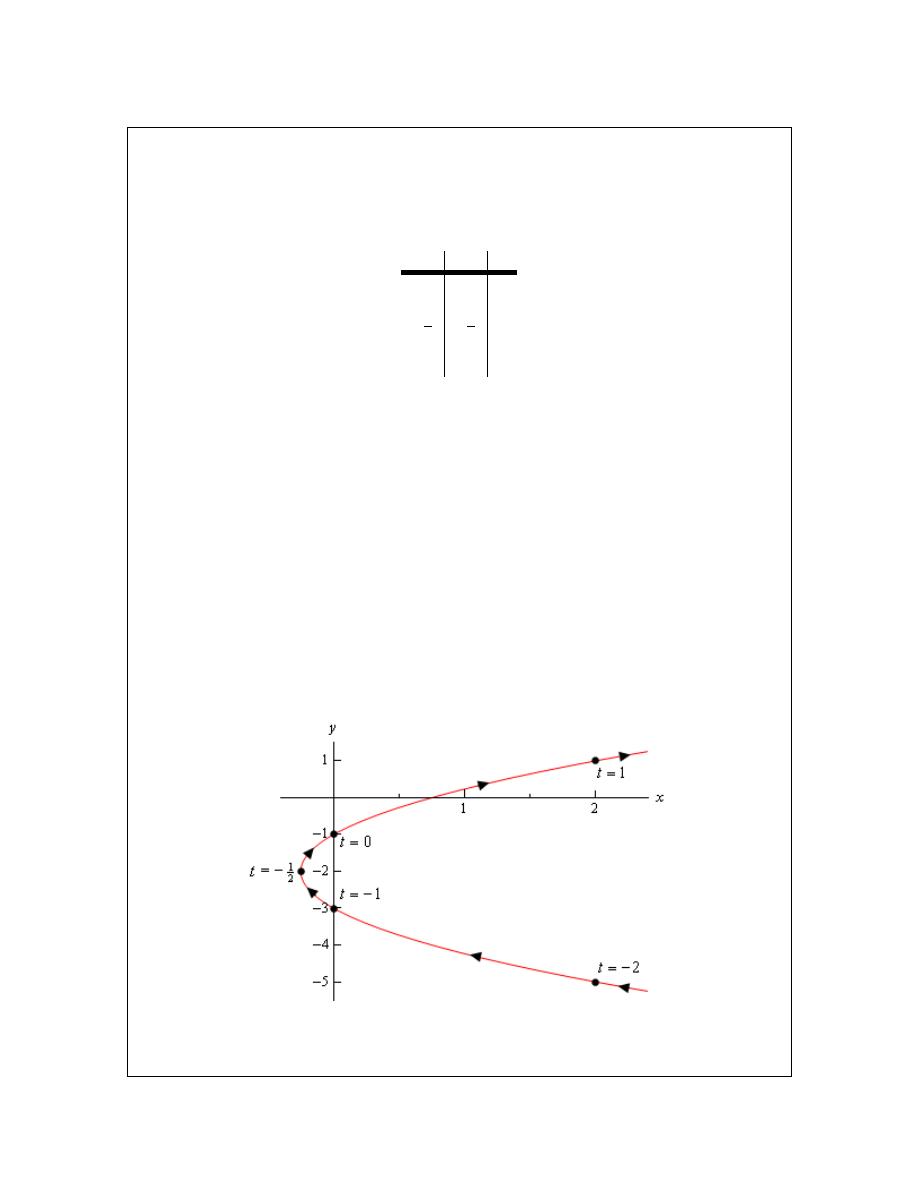

Example 1

Sketch the parametric curve for the following set of parametric equations.

2

2

1

x

t

t

y

t

= +

= −

Solution

At this point our only option for sketching a parametric curve is to pick values of t, plug them into

the parametric equations and then plot the points. So, let’s plug in some t’s.

t

x

y

-2

2

-5

-1

0

-3

1

2

−

1

4

−

-2

0

0

-1

1

2

1

The first question that should be asked at this point is, how did we know to use the values of t that

we did, especially the third choice? Unfortunately, there is no real answer to this question at this

point. We simply pick t’s until we are fairly confident that we’ve got a good idea of what the

curve looks like. It is this problem with picking “good” values of t that make this method of

sketching parametric curves one of the poorer choices. Sometimes we have no choice, but if we

do have a choice we should avoid it.

We’ll discuss an alternate graphing method in later examples that will help to explain how these

values of t were chosen.

We have one more idea to discuss before we actually sketch the curve. Parametric curves have a

direction of motion. The direction of motion is given by increasing t. So, when plotting

parametric curves, we also include arrows that show the direction of motion. We will often give

the value of t that gave specific points on the graph as well to make it clear the value of t that

gave that particular point.

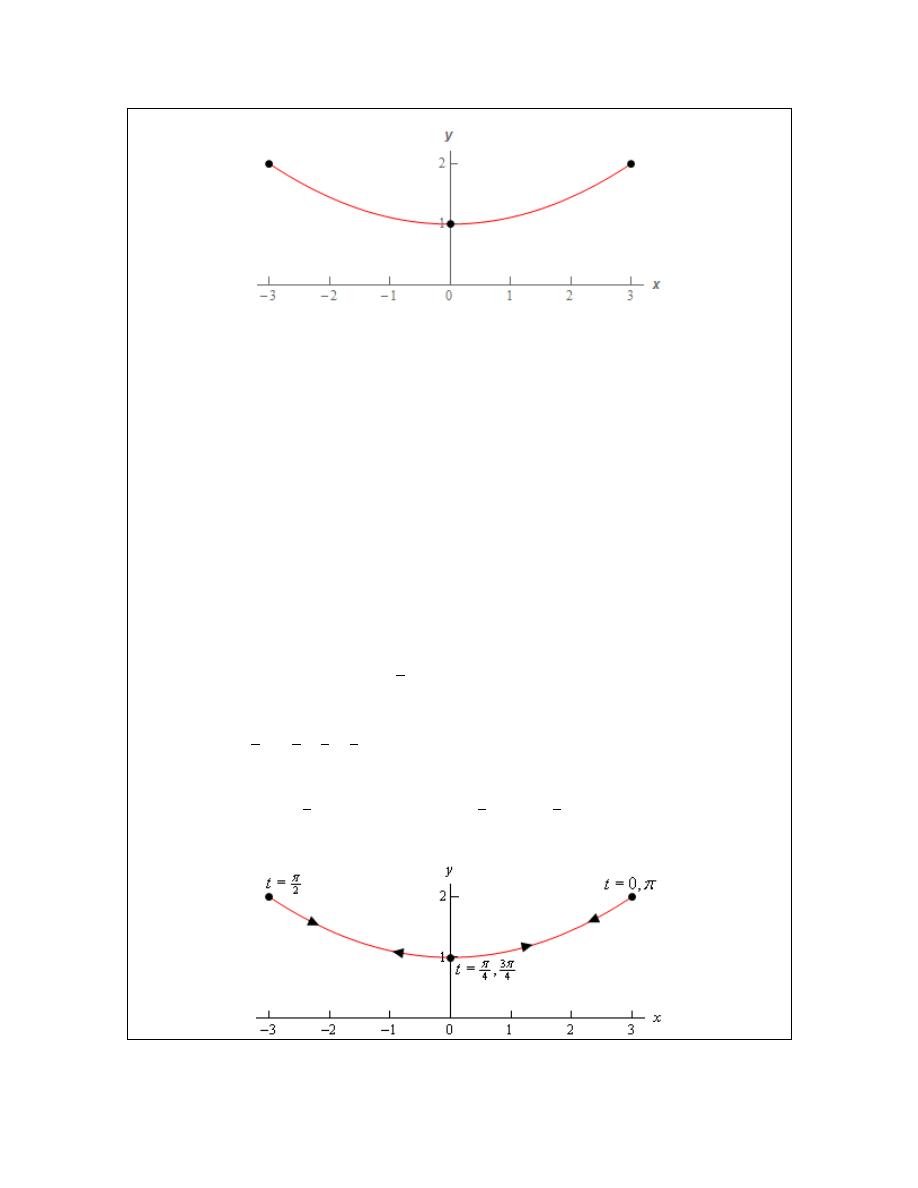

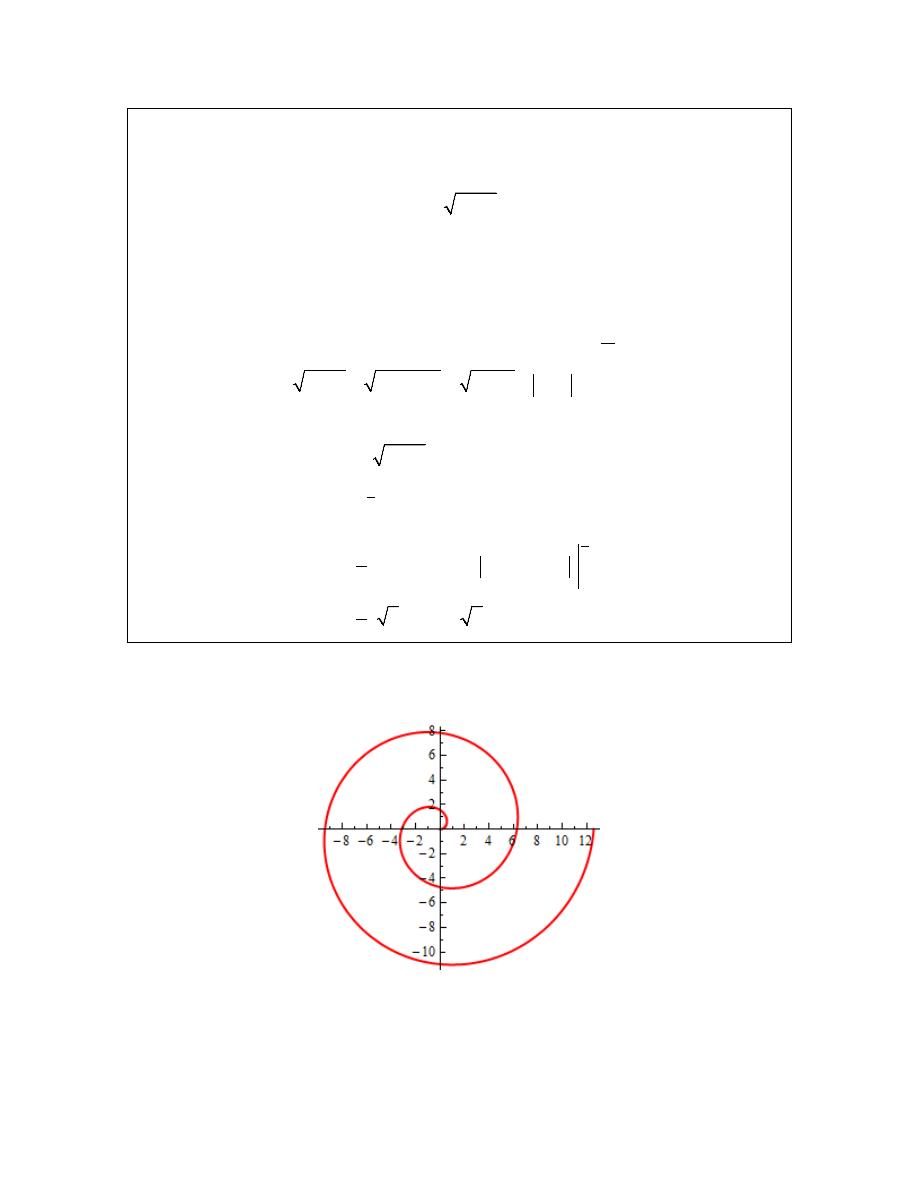

Here is the sketch of this parametric curve.

So, it looks like we have a parabola that opens to the right.

Before we end this example there is a somewhat important and subtle point that we need to

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

7

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

discuss first. Notice that we made sure to include a portion of the sketch to the right of the points

corresponding to

2

t

= −

and

1

t

=

to indicate that there are portions of the sketch there. Had we

simply stopped the sketch at those points we are indicating that there was no portion of the curve

to the right of those points and there clearly will be. We just didn’t compute any of those points.

This may seem like an unimportant point, but as we’ll see in the next example it’s more important

than we might think.

Before addressing a much easier way to sketch this graph let’s first address the issue of limits on

the parameter. In the previous example we didn’t have any limits on the parameter. Without

limits on the parameter the graph will continue in both directions as shown in the sketch above.

We will often have limits on the parameter however and this will affect the sketch of the

parametric equations. To see this effect let’s look a slight variation of the previous example.

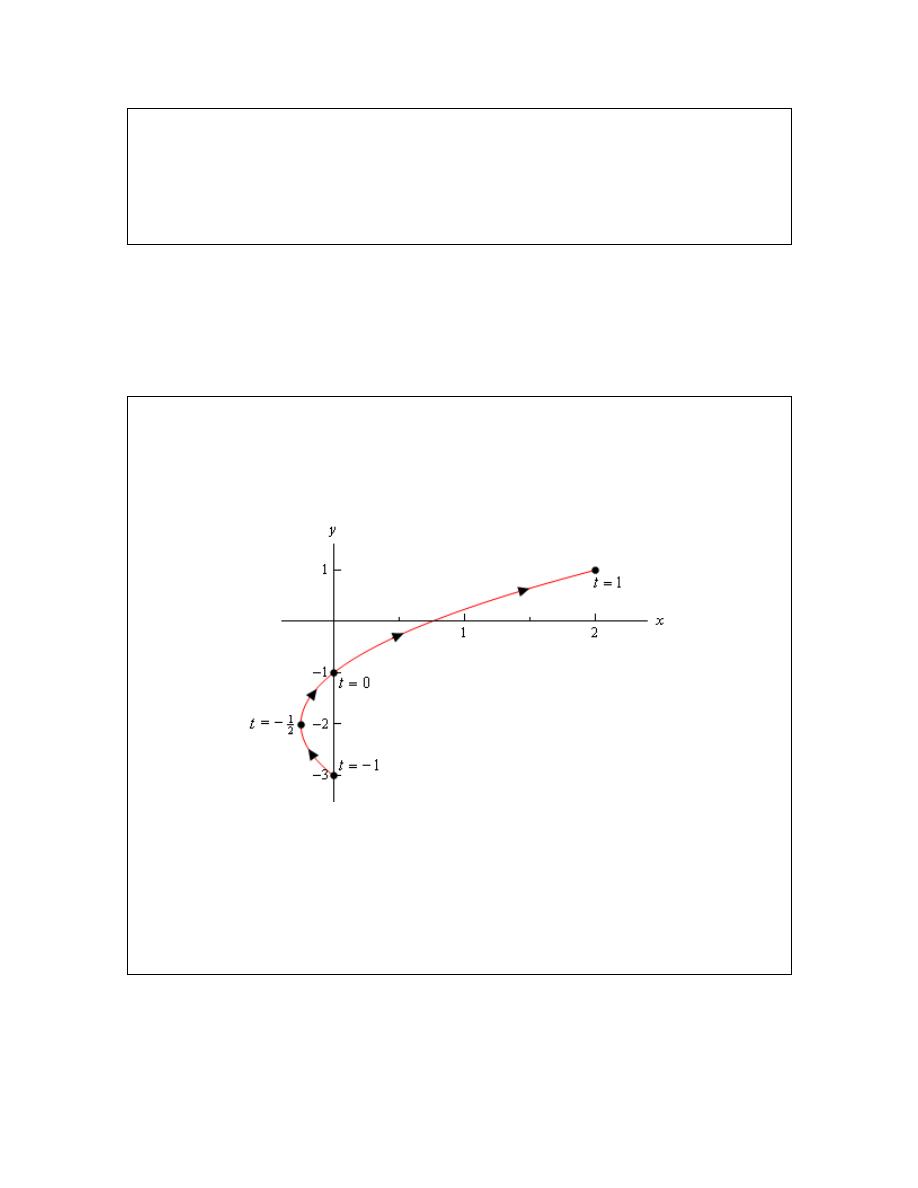

Example 2

Sketch the parametric curve for the following set of parametric equations.

2

2

1

1

1

x

t

t

y

t

t

= +

= −

− ≤ ≤

Solution

Note that the only difference here is the presence of the limits on t. All these limits do is tell us

that we can’t take any value of t outside of this range. Therefore, the parametric curve will only

be a portion of the curve above. Here is the parametric curve for this example.

Notice that with this sketch we started and stopped the sketch right on the points originating from

the end points of the range of t’s. Contrast this with the sketch in the previous example where we

had a portion of the sketch to the right of the “start” and “end” points that we computed.

In this case the curve starts at

1

t

= −

and ends at

1

t

=

, whereas in the previous example the

curve didn’t really start at the right most points that we computed. We need to be clear in our

sketches if the curve starts/ends right at a point, or if that point was simply the first/last one that

we computed.

It is now time to take a look at an easier method of sketching this parametric curve. This method

uses the fact that in many, but not all, cases we can actually eliminate the parameter from the

parametric equations and get a function involving only x and y. We will sometimes call this the

algebraic equation to differentiate it from the original parametric equations. There will be two

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

8

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

small problems with this method, but it will be easy to address those problems. It is important to

note however that we won’t always be able to do this.

Just how we eliminate the parameter will depend upon the parametric equations that we’ve got.

Let’s see how to eliminate the parameter for the set of parametric equations that we’ve been

working with to this point.

Example 3

Eliminate the parameter from the following set of parametric equations.

2

2

1

x

t

t

y

t

= +

= −

Solution

One of the easiest ways to eliminate the parameter is to simply solve one of the equations for the

parameter (t, in this case) and substitute that into the other equation. Note that while this may be

the easiest to eliminate the parameter, it’s usually not the best way as we’ll see soon enough.

In this case we can easily solve y for t.

(

)

1

1

2

t

y

=

+

Plugging this into the equation for x gives the following algebraic equation,

(

)

(

)

2

2

1

1

1

3

1

1

2

2

4

4

x

y

y

y

y

=

+

+

+ =

+ +

Sure enough from our Algebra knowledge we can see that this is a parabola that opens to the right

and will have a vertex at

(

)

1

4

, 2

− −

.

We won’t bother with a sketch for this one as we’ve already sketched this once and the point here

was more to eliminate the parameter anyway.

Before we leave this example let’s address one quick issue.

In the first example we just, seemingly randomly, picked values of t to use in our table, especially

the third value. There really was no apparent reason for choosing

1

2

t

= −

. It is however

probably the most important choice of t as it is the one that gives the vertex.

The reality is that when writing this material up we actually did this problem first then went back

and did the first problem. Plotting points is generally the way most people first learn how to

construct graphs and it does illustrate some important concepts, such as direction, so it made

sense to do that first in the notes. In practice however, this example is often done first.

So, how did we get those values of t? Well let’s start off with the vertex as that is probably the

most important point on the graph. We have the x and y coordinates of the vertex and we also

have x and y parametric equations for those coordinates. So, plug in the coordinates for the

vertex into the parametric equations and solve for t. Doing this gives,

(

)

2

1

1

2

4

1

2

double root

2

2

1

t

t

t

t

t

= −

− = +

⇒

= −

− = −

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

9

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

So, as we can see, the value of t that will give both of these coordinates is

1

2

t

= −

. Note that the

x parametric equation gave a double root and this will often not happen. Often we would have

gotten two distinct roots from that equation. In fact, it won’t be unusual to get multiple values of

t from each of the equations.

However, what we can say is that there will be a value(s) of t that occurs in both sets of solutions

and that is the t that we want for that point. We’ll eventually see an example where this happens

in a later section.

Now, from this work we can see that if we use

1

2

t

= −

we will get the vertex and so we included

that value of t in the table in Example 1. Once we had that value of t we chose two integer values

of t on either side to finish out the table.

As we will see in later examples in this section determining values of t that will give specific

points is something that we’ll need to do on a fairly regular basis. It is fairly simple however as

this example has shown. All we need to be able to do is solve a (usually) fairly basic equation

which by this point in time shouldn’t be too difficult.

Getting a sketch of the parametric curve once we’ve eliminated the parameter seems fairly

simple. All we need to do is graph the equation that we found by eliminating the parameter. As

noted already however, there are two small problems with this method. The first is direction of

motion. The equation involving only x and y will NOT give the direction of motion of the

parametric curve. This is generally an easy problem to fix however. Let’s take a quick look at

the derivatives of the parametric equations from the last example. They are,

2

1

2

dx

t

dt

dy

dt

= +

=

Now, all we need to do is recall our Calculus I knowledge. The derivative of y with respect to t is

clearly always positive. Recalling that one of the interpretations of the first derivative is rate of

change we now know that as t increases y must also increase. Therefore, we must be moving up

the curve from bottom to top as t increases as that is the only direction that will always give an

increasing y as t increases.

Note that the x derivative isn’t as useful for this analysis as it will be both positive and negative

and hence x will be both increasing and decreasing depending on the value of t. That doesn’t help

with direction much as following the curve in either direction will exhibit both increasing and

decreasing x.

In some cases, only one of the equations, such as this example, will give the direction while in

other cases either one could be used. It is also possible that, in some cases, both derivatives

would be needed to determine direction. It will always be dependent on the individual set of

parametric equations.

The second problem with eliminating the parameter is best illustrated in an example as we’ll be

running into this problem in the remaining examples.

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

10

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

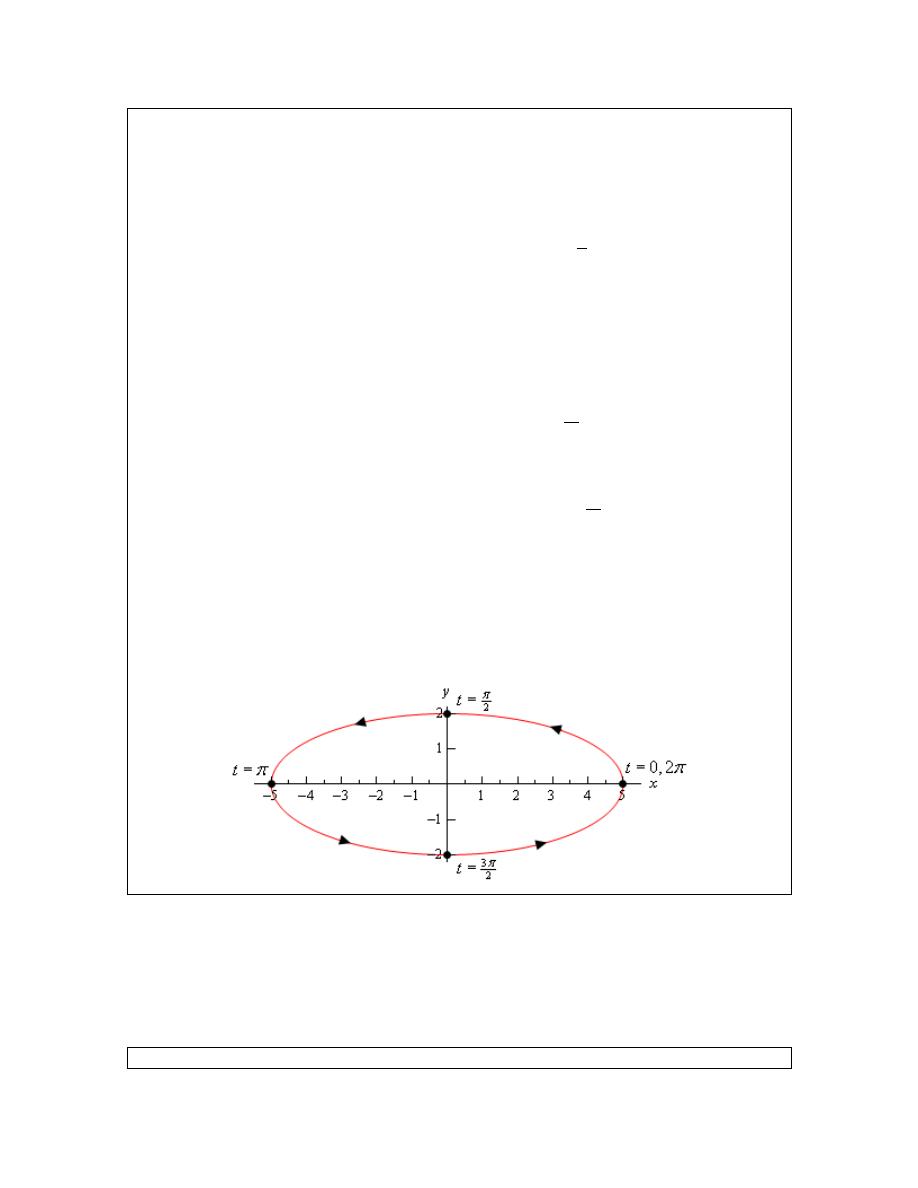

Example 4

Sketch the parametric curve for the following set of parametric equations. Clearly

indicate direction of motion.

5 cos

2 sin

0

2

x

t

y

t

t

π

=

=

≤ ≤

Solution

Before we proceed with eliminating the parameter for this problem let’s first address again why

just picking t’s and plotting points is not really a good idea.

Given the range of t’s in the problem statement let’s use the following set of t’s.

t

x

y

0

5

0

2

π

0

2

π

-5

0

3

2

π

0

-2

2

π

5

0

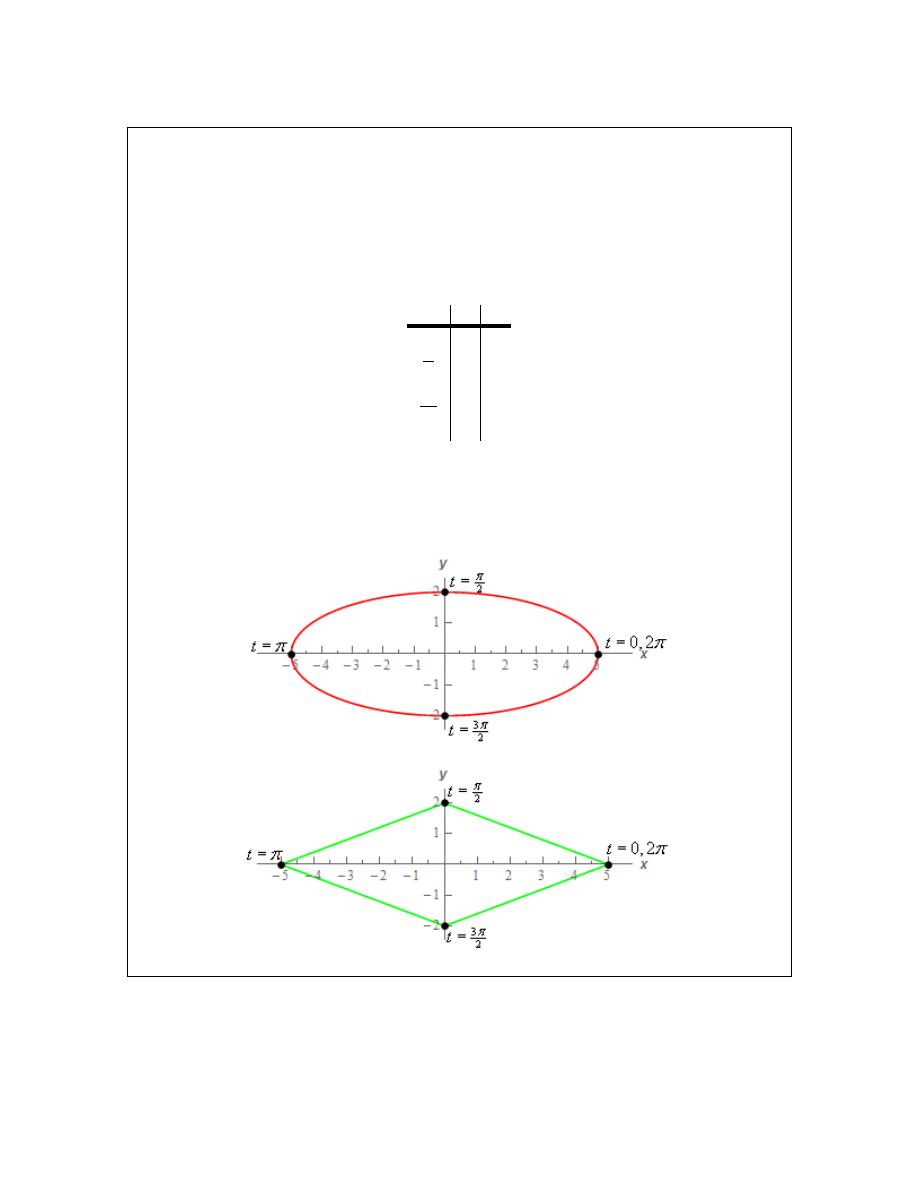

The question that we need to ask now is do we have enough points to accurately sketch the graph

of this set of parametric equations? Below are some sketches of some possible graphs of the

parametric equation based only on these five points.

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

11

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Given the nature of sine/cosine you might be able to eliminate the diamond and the square but

there is no denying that they are graphs that go through the given points. The last graph is also a

little silly but it does show a graph going through the given points.

Again, given the nature of sine/cosine you can probably guess that the correct graph is the ellipse.

However, that is all that would be at this point. A guess. Nothing actually says unequivocally

that the parametric curve is an ellipse just from those five points. That is the danger of sketching

parametric curves based on a handful of points. Unless we know what the graph will be ahead of

time we are really just making a guess.

So, in general, we should avoid plotting points to sketch parametric curves. The best method,

provided it can be done, is to eliminate the parameter. As noted just prior to starting this example

there is still a potential problem with eliminating the parameter that we’ll need to deal with. We

will eventually discuss this issue. For now, let’s just proceed with eliminating the parameter.

We’ll start by eliminating the parameter as we did in the previous section. We’ll solve one of the

of the equations for t and plug this into the other equation. For example, we could do the

following,

1

1

cos

2 sin cos

5

5

x

x

t

y

−

−

=

⇒

=

Can you see the problem with doing this? This is definitely easy to do but we have a greater

chance of correctly graphing the original parametric equations by plotting points than we do

graphing this!

There are many ways to eliminate the parameter from the parametric equations and solving for t

is usually not the best way to do it. While it is often easy to do we will, in most cases, end up

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

12

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

with an equation that is almost impossible to deal with.

So, how can we eliminate the parameter here? In this case all we need to do is recall a very nice

trig identity and the equation of an ellipse. Let’s notice that we could do the following here.

2

2

2

2

2

2

25 cos

4 sin

cos

sin

1

25

4

25

4

x

y

t

t

t

t

+

=

+

=

+

=

Eliminating the middle steps gives the following algebraic equation,

2

2

1

25

4

x

y

+

=

and so it looks like we’ve got an ellipse.

Before proceeding with this example it should be noted that what we did was probably not all that

obvious to most. However, once it’s been done it does clearly work and so it’s a nice idea that we

can use to eliminate the parameter from some parametric equations involving sines and cosines.

It won’t always work and sometimes it will take a lot more manipulation of things than we did

here.

An alternate method that we could have used here was to solve the two parametric equations for

sine and cosine as follows,

cos

sin

5

2

x

y

t

t

=

=

Then, recall the trig identity we used above and these new equations we get,

2

2

2

2

2

2

1

cos

sin

5

2

25

4

x

y

x

y

t

t

=

+

=

+

=

+

So, the same answer as the other method. Which method you use will probably depend on which

you find easier to use. Both are perfectly valid and will get the same result.

Now, let’s continue on with the example. We’ve identified that the parametric equations describe

an ellipse, but we can’t just sketch an ellipse and be done with it.

First, just because the algebraic equation was an ellipse doesn’t actually mean that the parametric

curve is the full ellipse. It is always possible that the parametric curve is only a portion of the

ellipse. In order to identify just how much of the ellipse the parametric curve will cover let’s go

back to the parametric equations and see what they tell us about any limits on x and y. Based on

our knowledge of sine and cosine we have the following,

1 cos

1

5

5 cos

5

5

5

1 sin

1

2

2 sin

2

2

2

t

t

x

t

t

y

− ≤

≤

⇒

− ≤

≤

⇒

− ≤ ≤

− ≤

≤

⇒

− ≤

≤

⇒

− ≤ ≤

So, by starting with sine/cosine and “building up” the equation for x and y using basic algebraic

manipulations we get that the parametric equations enforce the above limits on x and y. In this

case, these also happen to be the full limits on x and y we get by graphing the full ellipse.

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

13

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

This is the second potential issue alluded to above. The parametric curve may not always trace

out the full graph of the algebraic curve. We should always find limits on x and y enforced upon

us by the parametric curve to determine just how much of the algebraic curve is actually sketched

out by the parametric equations.

Therefore, in this case, we now know that we get a full ellipse from the parametric equations.

Before we proceed with the rest of the example be careful to not always just assume we will get

the full graph of the algebraic equation. There are definitely times when we will not get the full

graph and we’ll need to do a similar analysis to determine just how much of the graph we actually

get. We’ll see an example of this later.

Note as well that any limits on t given in the problem statement can also affect how much of the

graph of the algebraic equation we get. In this case however, based on the table of values we

computed at the start of the problem we can see that we do indeed get the full ellipse in the range

0

2

t

π

≤ ≤

. That won’t always be the case however, so pay attention to any restrictions on t that

might exist!

Next, we need to determine a direction of motion for the parametric curve. Recall that all

parametric curves have a direction of motion and the equation of the ellipse simply tells us

nothing about the direction of motion.

To get the direction of motion it is tempting to just use the table of values we computed above to

get the direction of motion. In this case, we would guess (and yes that is all it is – a guess) that

the curve traces out in a counter-clockwise direction. We’d be correct. In this case, we’d be

correct! The problem is that tables of values can be misleading when determining a direction of

motion as we’ll see in the next example.

Therefore, it is best to not use a table of values to determine the direction of motion. To correctly

determine the direction of motion we’ll use the same method of determining the direction that we

discussed after Example 3. In other words, we’ll take the derivative of the parametric equations

and use our knowledge of Calculus I and trig to determine the direction of motion.

The derivatives of the parametric equations are,

5sin

2 cos

dx

dy

t

t

dt

dt

= −

=

Now, at

0

t

=

we are at the point

( )

5, 0

and let’s see what happens if we start increasing t. Let’s

increase t from

0

t

=

to

2

t

π

=

. In this range of t’s we know that sine is always positive and so

from the derivative of the x equation we can see that x must be decreasing in this range of t’s.

This, however, doesn’t really help us determine a direction for the parametric curve. Starting at

( )

5, 0

no matter if we move in a clockwise or counter-clockwise direction x will have to decrease

so we haven’t really learned anything from the x derivative.

The derivative from the y parametric equation on the other hand will help us. Again, as we

increase t from

0

t

=

to

2

t

π

=

we know that cosine will be positive and so y must be increasing

in this range. That however, can only happen if we are moving in a counter-clockwise direction.

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

14

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

If we were moving in a clockwise direction from the point

( )

5, 0

we can see that y would have to

decrease!

Therefore, in the first quadrant we must be moving in a counter-clockwise direction. Let’s move

on to the second quadrant.

So, we are now at the point

( )

0, 2

and we will increase t from

2

t

π

=

to

t

π

=

. In this range of t

we know that cosine will be negative and sine will be positive. Therefore, from the derivatives of

the parametric equations we can see that x is still decreasing and y will now be decreasing as well.

In this quadrant the y derivative tells us nothing as y simply must decrease to move from

( )

0, 2

.

However, in order for x to decrease, as we know it does in this quadrant, the direction must still

be moving a counter-clockwise rotation.

We are now at

(

)

5, 0

−

and we will increase t from

t

π

=

to

3

2

t

π

=

. In this range of t we know

that cosine is negative (and hence y will be decreasing) and sine is also negative (and hence x will

be increasing). Therefore, we will continue to move in a counter-clockwise motion.

For the 4

th

quadrant we will start at

(

)

0, 2

−

and increase t from

3

2

t

π

=

to

2

t

π

=

. In this range

of t we know that cosine is positive (and hence y will be increasing) and sine is negative (and

hence x will be increasing). So, as in the previous three quadrants, we continue to move in a

counter-clockwise motion.

At this point we covered the range of t’s we were given in the problem statement and during the

full range the motion was in a counter-clockwise direction.

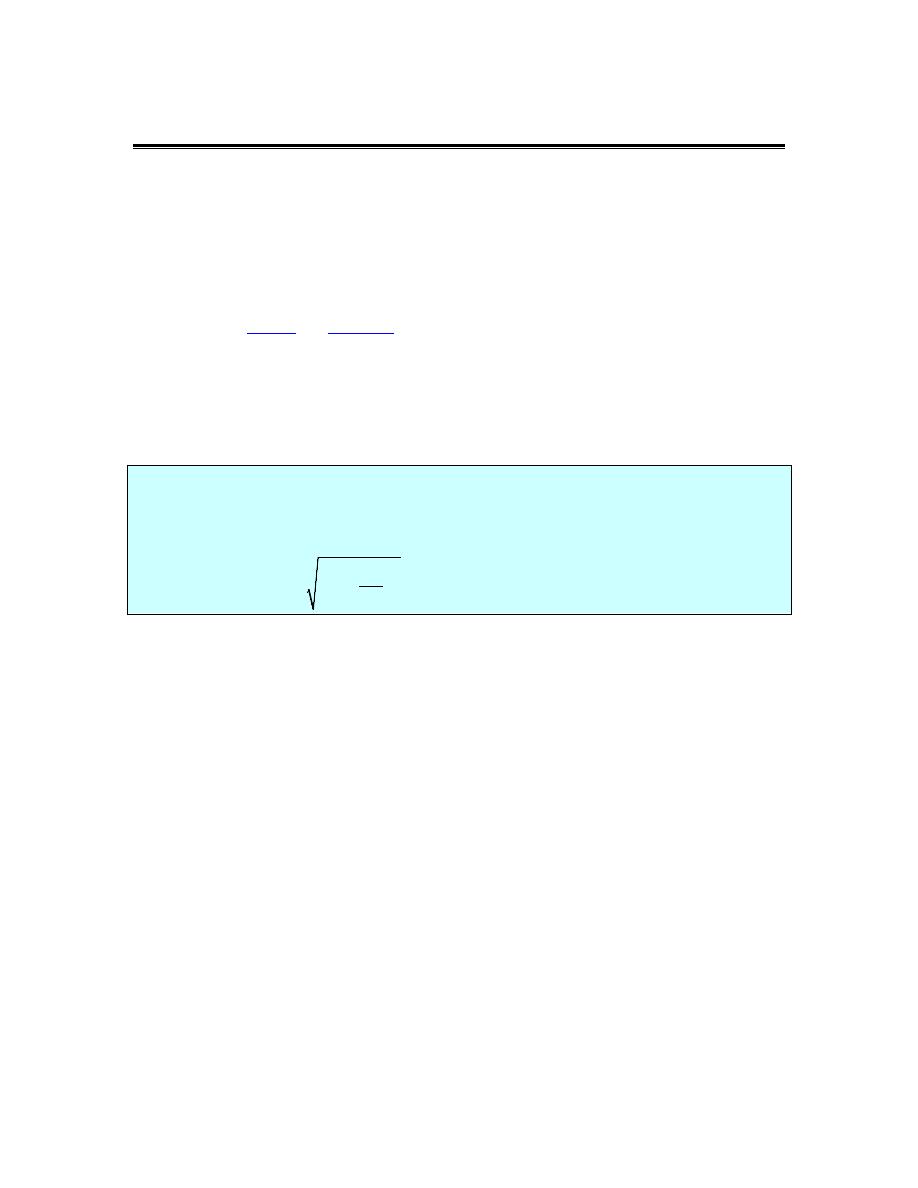

We can now fully sketch the parametric curve so, here is the sketch.

Okay, that was a really long example. Most of these types of problems aren’t as long. We just

had a lot to discuss in this one so we could get a couple of important ideas out of the way. The

rest of the examples in this section shouldn’t take as long to go through.

Now, let’s take a look at another example that will illustrate an important idea about parametric

equations.

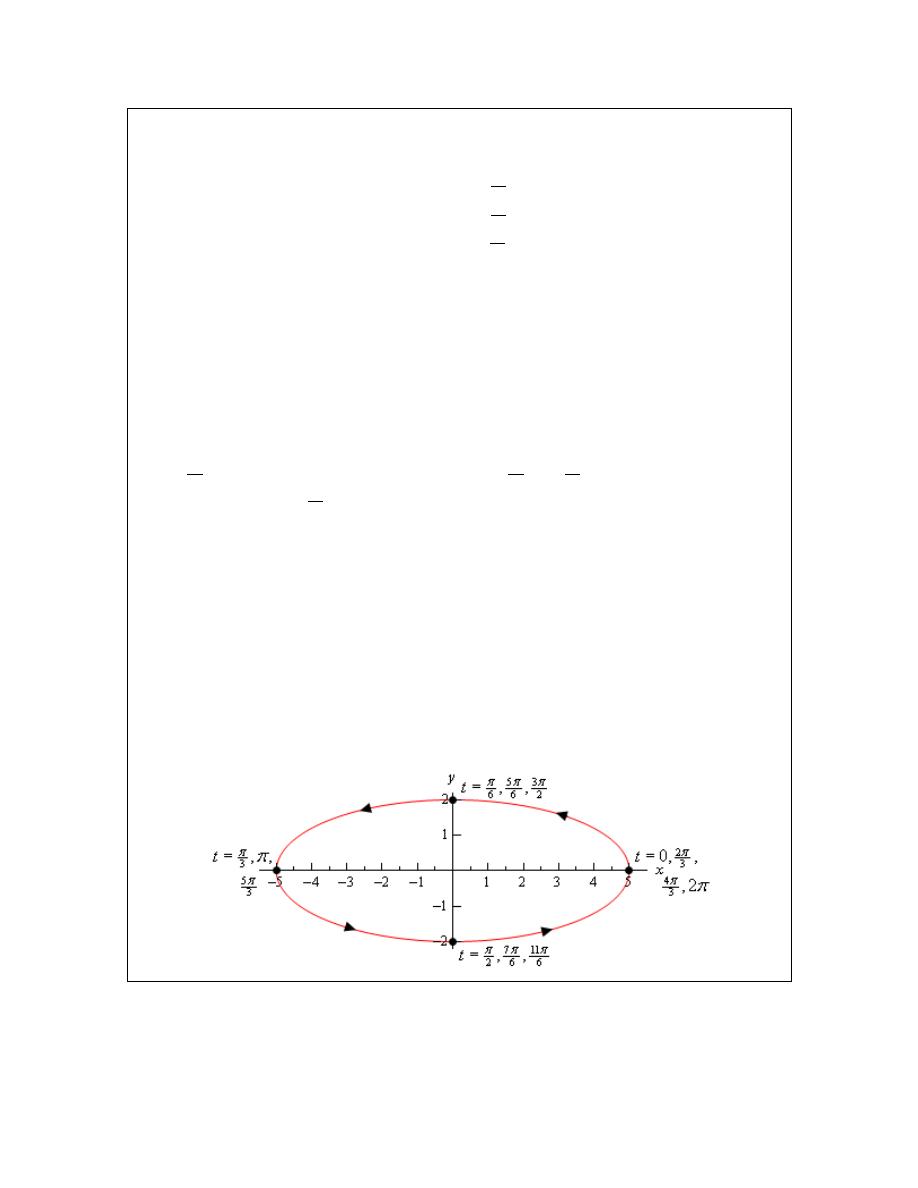

Example 5

Sketch the parametric curve for the following set of parametric equations. Clearly

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

15

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

indicate direction of motion.

( )

( )

5 cos 3

2 sin 3

0

2

x

t

y

t

t

π

=

=

≤ ≤

Solution

Note that the only difference in between these parametric equations and those in Example 4 is

that we replaced the t with 3t. We can eliminate the parameter here using either of the methods

we discussed in the previous example. In this case we’ll do the following,

( )

( )

( )

( )

2

2

2

2

2

2

25 cos

3

4 sin

3

cos

3

sin

3

1

25

4

25

4

t

t

x

y

t

t

+

=

+

=

+

=

So, we get the same ellipse that we did in the previous example. Also note that we can do the

same analysis on the parametric equations to determine that we have exactly the same limits on x

and y. Namely,

5

5

2

2

x

y

− ≤ ≤

− ≤ ≤

It’s starting to look like changing the t into a 3t in the trig equations will not change the

parametric curve in any way. That is not correct however. The curve does change in a small but

important way which we will be discussing shortly.

Before discussing that small change the 3t brings to the curve let’s discuss the direction of motion

for this curve. Despite the fact that we said in the last example that picking values of t and

plugging in to the equations to find points to plot is a bad idea let’s do it any way.

Given the range of t’s from the problem statement the following set looks like a good choice of

t’s to use.

t

x

y

0

5

0

2

π

0

-2

π

-5

0

3

2

π

0

2

2

π

5

0

So, the only change to this table of values/points from the last example is all the nonzero y values

changed sign. From a quick glance at the values in this table it would look like the curve, in this

case, is moving in a clockwise direction. But is that correct? Recall we said that these tables of

values can be misleading when used to determine direction and that’s why we don’t use them.

Let’s see if our first impression is correct. We can check our first impression by doing the

derivative work to get the correct direction. Let’s work with just the y parametric equation as the

x will have the same issue that it had in the previous example. The derivative of the y parametric

equation is,

( )

6 cos 3

dy

t

dt

=

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

16

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Now, if we start at

0

t

=

as we did in the previous example and start increasing t. At

0

t

=

the

derivative is clearly positive and so increasing t (at least initially) will force y to also be

increasing. The only way for this to happen is if the curve is in fact tracing out in a counter-

clockwise direction initially.

Now, we could continue to look at what happens as we further increase t, but when dealing with a

parametric curve that is a full ellipse (as this one is) and the argument of the trig functions is of

the form nt for any constant n the direction will not change so once we know the initial direction

we know that it will always move in that direction. Note that this is only true for parametric

equations in the form that we have here. We’ll see in later examples that for different kinds of

parametric equations this may no longer be true.

Okay, from this analysis we can see that the curve must be traced out in a counter-clockwise

direction. This is directly counter to our guess from the tables of values above and so we can see

that, in this case, the table would probably have led us to the wrong direction. So, once again,

tables are generally not very reliable for getting pretty much any real information about a

parametric curve other than a few points that must be on the curve. Outside of that the tables are

rarely useful and will generally not be dealt with in further examples.

So, why did our table give an incorrect impression about the direction? Well recall that we

mentioned earlier that the 3t will lead to a small but important change to the curve versus just a t?

Let’s take a look at just what that change is as it will also answer what “went wrong” with our

table of values.

Let’s start by look at

0

t

=

. At

0

t

=

we are at the point

( )

5, 0

and let’s ask ourselves what

values of t put us back at this point. We saw in Example 3 how to determine value(s) of t that put

us at certain points and the same process will work here with a minor modification.

Instead of looking at both the x and y equations as we did in that example let’s just look at the x

equation. The reason for this is that we’ll note that there are two points on the ellipse that will

have a y coordinate of zero,

( )

5, 0

and

(

)

5, 0

−

. If we set the y coordinate equal to zero we’ll

find all the t’s that are at both of these points when we only want the values of t that are at

( )

5, 0

.

So, because the x coordinate of five will only occur at this point we can simply use the x

parametric equation to determine the values of t that will put us at this point. Doing this gives the

following equation and solution,

( )

( )

1

2

3

5

5 cos 3

3

cos

1

0 2

0, 1, 2, 3,

t

t

n

t

n

n

π

π

−

=

=

= +

→

=

= ± ± ±

Don’t forget that when solving a trig equation we need to add on the “

2 n

π

+

” where n represents

the number of full revolutions in the counter-clockwise direction (positive n) and clockwise

direction (negative n) that we rotate from the first solution to get all possible solutions to the

equation.

Now, let’s plug in a few values of n starting at

0

n

=

. We don’t need negative n in this case

since all of those would result in negative t and those fall outside of the range of t’s we were

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

17

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

given in the problem statement. The first few values of t are then,

2

3

4

3

6

3

0

:

0

1

:

2

:

3

:

2

n

t

n

t

n

t

n

t

π

π

π

π

=

=

=

=

=

=

=

=

=

We can stop here as all further values of t will be outside the range of t’s given in this problem.

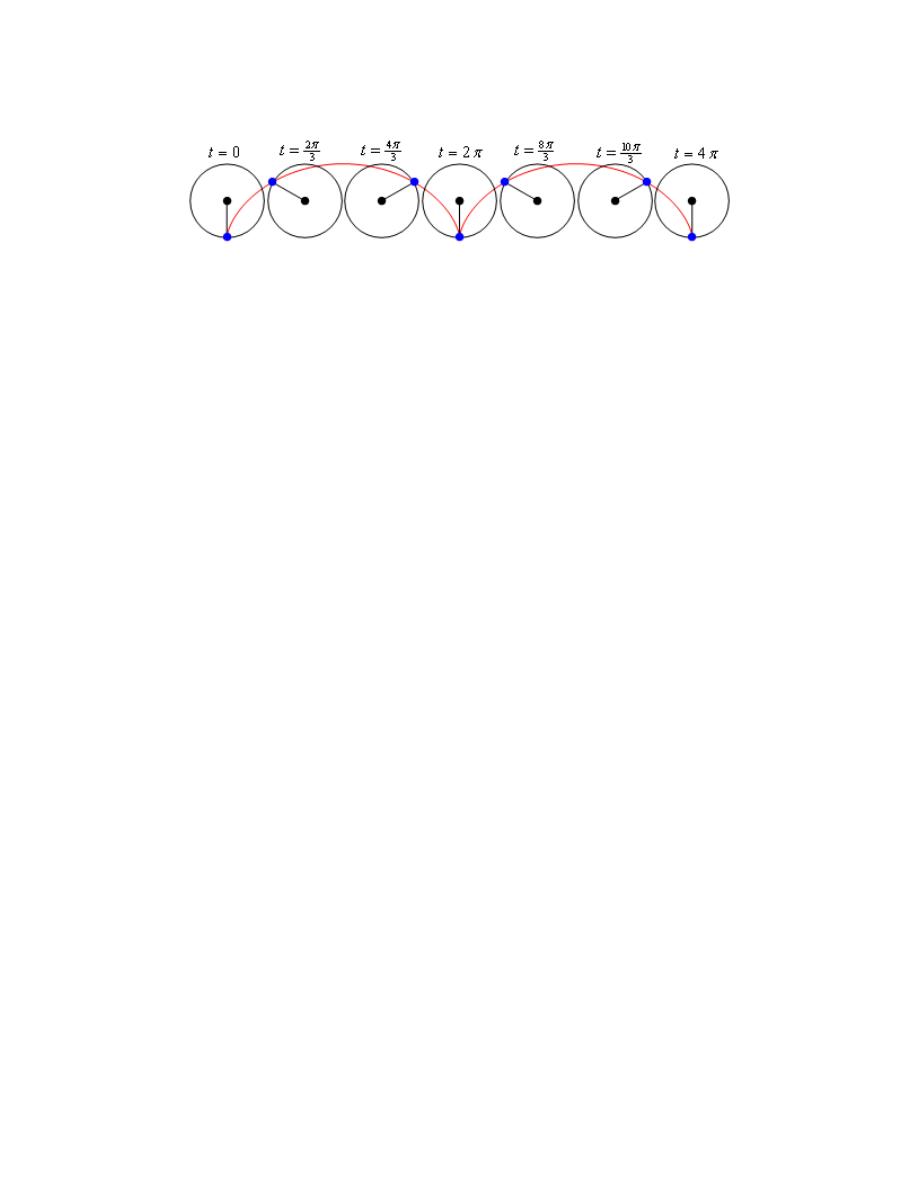

So, what is this telling us? Well back in Example 4 when the argument was just t the ellipse was

traced out exactly once in the range

0

2

t

π

≤ ≤

. However, when we change the argument to 3t

(and recalling that the curve will always be traced out in a counter-clockwise direction for this

problem) we are going through the “starting” point of

( )

5, 0

two more times than we did in the

previous example.

In fact, this curve is tracing out three separate times. The first trace is completed in the range

2

3

0

t

π

≤ ≤

. The second trace is completed in the range

2

4

3

3

t

π

π

≤ ≤

and the third and final trace

is completed in the range

4

3

2

t

π

π

≤ ≤

. In other words, changing the argument from t to 3t

increase the speed of the trace and the curve will now trace out three times in the range

0

2

t

π

≤ ≤

!

This is why the table gives the wrong impression. The speed of the tracing has increased leading

to an incorrect impression from the points in the table. The table seems to suggest that between

each pair of values of t a quarter of the ellipse is traced out in the clockwise direction when in

reality it is tracing out three quarters of the ellipse in the counter-clockwise direction.

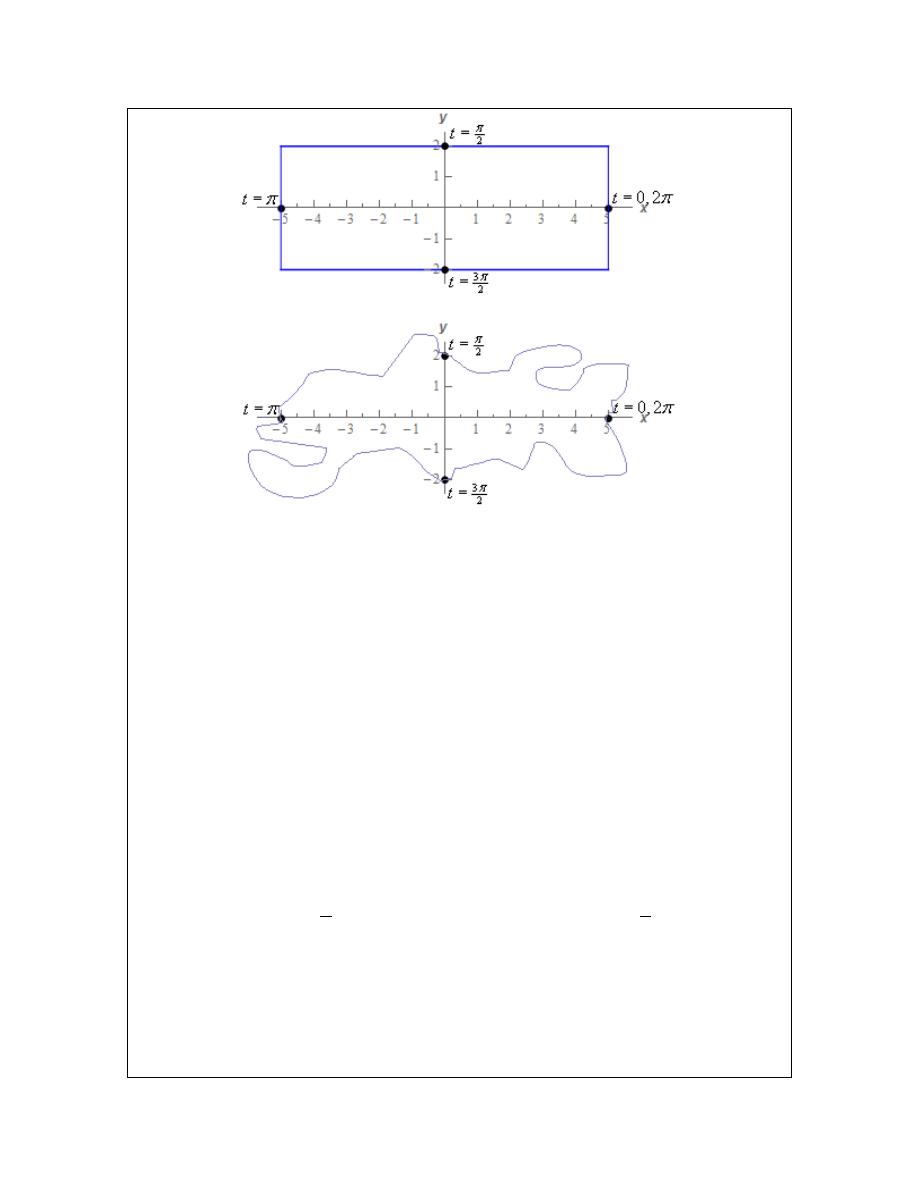

Here’s a final sketch of the curve and note that it really isn’t all that different from the previous

sketch. The only differences are the values of t and the various points we included. We did

include a few more values of t at various points just to illustrate where the curve is at for various

values of t but in general these really aren’t needed.

So, we saw in the last two examples two sets of parametric equations that in some way gave the

same graph. Yet, because they traced out the graph a different number of times we really do need

to think of them as different parametric curves at least in some manner. This may seem like a

difference that we don’t need to worry about, but as we will see in later sections this can be a very

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

18

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

important difference. In some of the later sections we are going to need a curve that is traced out

exactly once.

Before we move on to other problems let’s briefly acknowledge what happens by changing the t

to an nt in these kinds of parametric equations. When we are dealing with parametric equations

involving only sines and cosines and they both have the same argument if we change the

argument from t to nt we simply change the speed with which the curve is traced out. If

1

n

>

we

will increase the speed and if

1

n

<

we will decrease the speed.

Let’s take a look at a couple more examples.

Example 6

Sketch the parametric curve for the following set of parametric equations. Clearly

identify the direction of motion. If the curve is traced out more than once give a range of the

parameter for which the curve will trace out exactly once.

2

sin

2 cos

x

t

y

t

=

=

Solution

We can eliminate the parameter much as we did in the previous two examples. However, we’ll

need to note that the x already contains a

2

sin t

and so we won’t need to square the x. We will

however, need to square the y as we need in the previous two examples.

2

2

2

2

sin

cos

1

1

4

4

y

y

x

t

t

x

+

=

+

=

⇒

= −

In this case the algebraic equation is a parabola that opens to the left.

We will need to be very, very careful however in sketching this parametric curve. We will NOT

get the whole parabola. A sketch of the algebraic form parabola will exist for all possible values

of y. However, the parametric equations have defined both x and y in terms of sine and cosine

and we know that the ranges of these are limited and so we won’t get all possible values of x and

y here. So, first let’s get limits on x and y as we did in previous examples. Doing this gives,

2

1 sin

1

0

sin

1

0

1

1 cos

1

2

2 cos

2

2

2

t

t

x

t

t

y

− ≤

≤

⇒

≤

≤

⇒

≤ ≤

− ≤

≤

⇒

− ≤

≤

⇒

− ≤ ≤

So, it is clear from this that we will only get a portion of the parabola that is defined by the

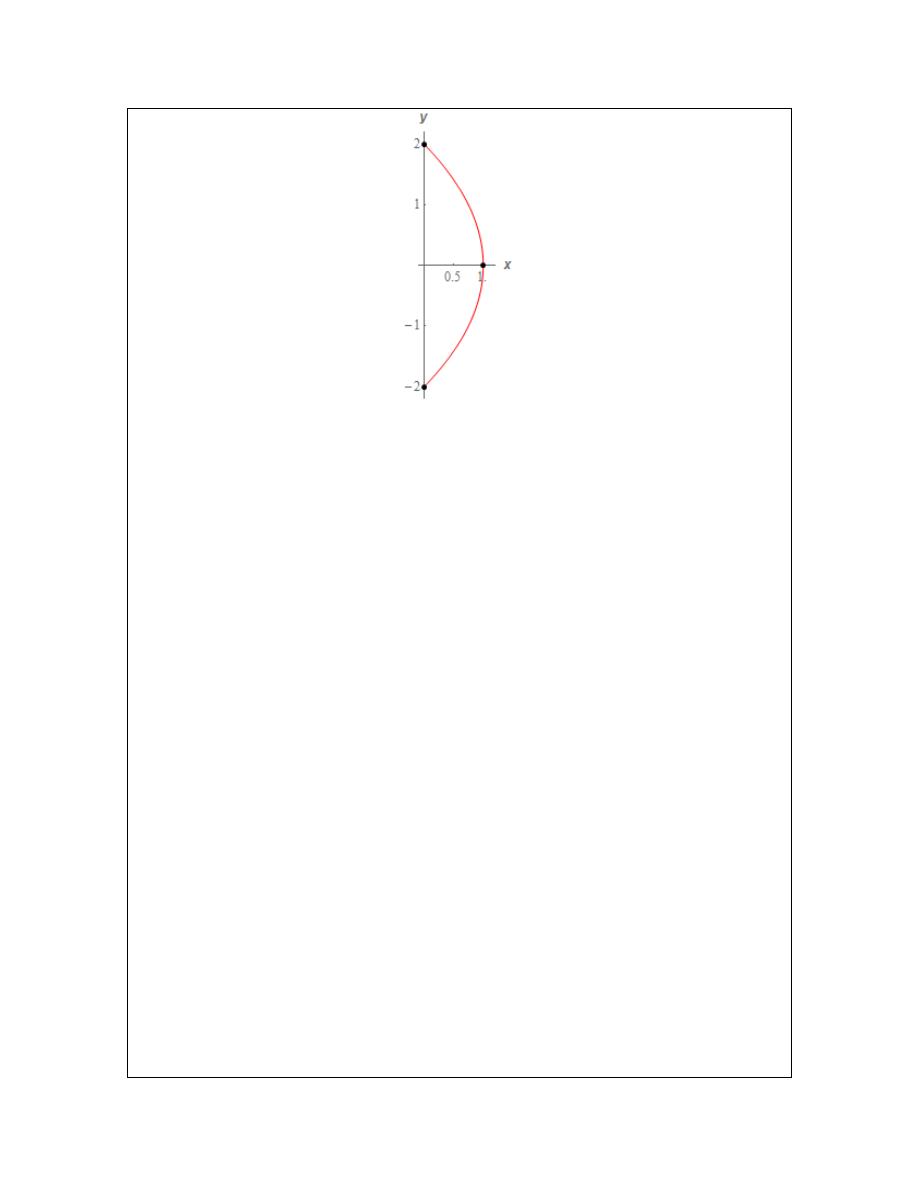

algebraic equation. Below is a quick sketch of the portion of the parabola that the parametric

curve will cover.

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

19

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

To finish the sketch of the parametric curve we also need the direction of motion for the curve.

Before we get to that however, let’s jump forward and determine the range of t’s for one trace.

To do this we’ll need to know the t’s that put us at each end point and we can follow the same

procedure we used in the previous example. The only difference is this time let’s use the y

parametric equation instead of the x because the y coordinates of the two end points of the curve

are different whereas the x coordinates are the same.

So, for the top point we have,

( )

1

2

2 cos

cos

1

0 2

2

,

0, 1, 2, 3,

t

t

n

n

n

π

π

−

=

=

= +

=

= ± ± ±

For, plugging in some values of n we get that the curve will be at the top point at,

, 4 , 2 , 0, 2 , 4 ,

t

π

π

π π

=

−

−

Similarly, for the bottom point we have,

( )

1

2

2 cos

cos

1

2

,

0, 1, 2, 3,

t

t

n

n

π

π

−

− =

=

− = +

= ± ± ±

So, we see that we will be at the bottom point at,

, 3 ,

, , 3 ,

t

π π π π

=

−

−

So, if we start at say,

0

t

=

, we are at the top point and we increase t we have to move along the

curve downwards until we reach

t

π

=

at which point we are now at the bottom point. This

means that we will trace out the curve exactly once in the range

0

t

π

≤ ≤

.

This is not the only range that will trace out the curve however. Note that if we further increase t

from

t

π

=

we will now have to travel back up the curve until we reach

2

t

π

=

and we are now

back at the top point. Increasing t again until we reach

3

t

π

=

will take us back down the curve

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

20

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

until we reach the bottom point again, etc. From this analysis we can get two more ranges of t for

one trace,

2

2

3

t

t

π

π

π

π

≤ ≤

≤ ≤

As you can probably see there are an infinite number of ranges of t we could use for one trace of

the curve. Any of them would be acceptable answers for this problem.

Note that in the process of determining a range of t’s for one trace we also managed to determine

the direction of motion for this curve. In the range

0

t

π

≤ ≤

we had to travel downwards along

the curve to get from the top point at

0

t

=

to the bottom point at

t

π

=

. However, at

2

t

π

=

we

are back at the top point on the curve and to get there we must travel along the path. We can’t

just jump back up to the top point or take a different path to get there. All travel must be done on

the path sketched out. This means that we had to go back up the path. Further increasing t takes

us back down the path, then up the path again etc.

In other words, this path is sketched out in both directions because we are not putting any

restrictions on the t’s and so we have to assume we are using all possible values of t. If we had

put restrictions on which t’s to use we might really have ended up only moving in one direction.

That however would be a result only of the range of t’s we are using and not the parametric

equations themselves.

Note that we didn’t really need to do the above work to determine that the curve traces out in both

directions.in this case. Both the x and y parametric equations involve sine or cosine and we know

both of those functions oscillate. This, in turn means that both x and y will oscillate as well. The

only way for that to happen on this particular this curve will be for the curve to be traced out in

both directions.

Be careful with the above reasoning that the oscillatory nature of sine/cosine forces the curve to

be traced out in both directions. It can only be used in this example because the “starting” point

and “ending” point of the curves are in different places. The only way to get from one of the

“end” points on the curve to the other is to travel back along the curve in the opposite direction.

Contrast this with the ellipse in Example 4. In that case we had sine/cosine in the parametric

equations as well. However, the curve only traced out in one direction, not in both directions. In

Example 4 we were graphing the full ellipse and so no matter where we start sketching the graph

we will eventually get back to the “starting” point without ever retracing any portion of the graph.

In Example 4 as we trace out the full ellipse both x and y do in fact oscillate between their two

“endpoints” but the curve itself does not trace out in both directions for this to happen.

Basically, we can only use the oscillatory nature of sine/cosine to determine that the curve traces

out in both directions if the curve starts and ends at different points. If the starting/ending point is

the same then we generally need to go through the full derivative argument to determine the

actual direction of motion.

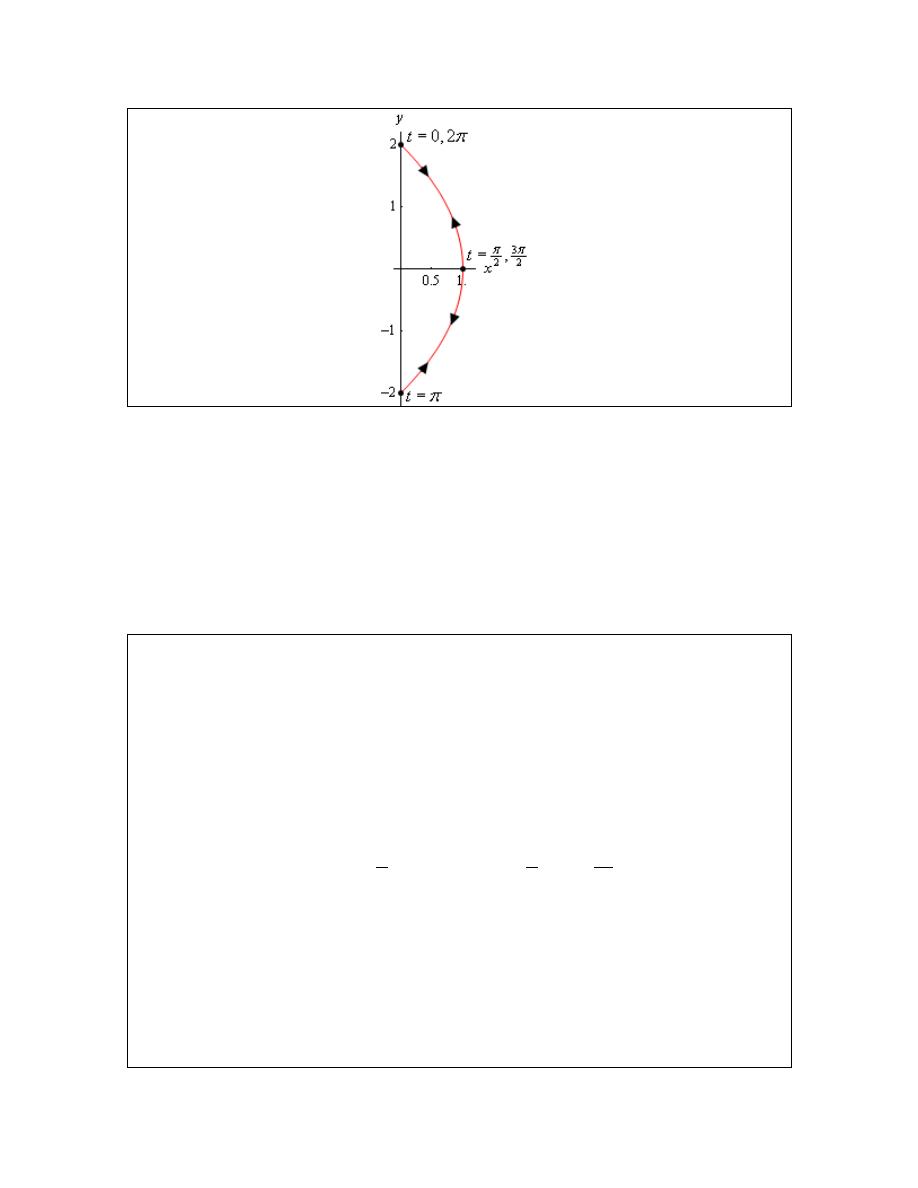

So, to finish this problem out, below is a sketch of the parametric curve. Note that we put

direction arrows in both directions to clearly indicate that it would be traced out in both

directions. We also put in a few values of t just to help illustrate the direction of motion.

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

21

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

To this point we’ve seen examples that would trace out the complete graph that we got by

eliminating the parameter if we took a large enough range of t’s. However, in the previous

example we’ve now seen that this will not always be the case. It is more than possible to have a

set of parametric equations which will continuously trace out just a portion of the curve. We can

usually determine if this will happen by looking for limits on x and y that are imposed up us by

the parametric equation.

We will often use parametric equations to describe the path of an object or particle. Let’s take a

look at an example of that.

Example 7

The path of a particle is given by the following set of parametric equations.

( )

( )

2

3cos 2

1 cos

2

x

t

y

t

=

= +

Completely describe the path of this particle. Do this by sketching the path, determining limits on

x and y and giving a range of t’s for which the path will be traced out exactly once (provide it

traces out more than once of course).

Solution

Eliminating the parameter this time will be a little different. We only have cosines this time and

we’ll use that to our advantage. We can solve the x equation for cosine and plug that into the

equation for y. This gives,

( )

2

2

cos 2

1

1

3

3

9

x

x

x

t

y

=

= +

= +

This time the algebraic equation is a parabola that opens upward. We also have the following

limits on x and y.

( )

( )

( )

( )

2

2

1 cos 2

1

3

3cos 2

3

3

3

0

cos

2

1

1 1 cos

2

2

1

2

t

t

x

t

t

y

− ≤

≤

− ≤

≤

− ≤ ≤

≤

≤

≤ +

≤

≤ ≤

So, again we only trace out a portion of the curve. Here is a quick sketch of the portion of the

parabola that the parametric curve will cover.

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

22

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Now, as we discussed in the previous example because both the x and y parametric equations

involve cosine we know that both x and y must oscillate and because the “start” and “end” points

of the curve are not the same the only way x and y can oscillate is for the curve to trace out in

both directions.

To finish the problem then all we need to do is determine a range of t’s for one trace. Because the

“end” points on the curve have the same y value and different x values we can use the x

parametric equation to determine these values. Here is that work.

( )

( )

3 :

3

3cos 2

1

cos 2

2

0 2

0, 1, 2, 3,

x

t

t

t

n

t

n

n

π

π

=

=

=

= +

→

=

= ± ± ±

( )

( )

1

2

3 :

3

3cos 2

1

cos 2

2

2

0, 1, 2, 3,

x

t

t

t

n

t

n

n

π

π

π π

= −

− =

− =

= +

→

=

+

= ± ± ±

So, we will be at the right end point at

, 2 ,

, 0, , 2 ,

t

π π

π π

=

−

−

and we’ll be at the left end

point at

3

3

1

1

2

2

2

2

,

,

,

,

,

t

π

π π π

=

−

−

. So, in this case there are an infinite number of ranges of

t’s for one trace. Here are a few of them.

1

1

1

2

2

2

0

0

t

t

t

π

π

π

π

−

≤ ≤

≤ ≤

≤ ≤

Here is a final sketch of the particle’s path with a few value of t on it.

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

23

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

We should give a small warning at this point. Because of the ideas involved in them we

concentrated on parametric curves that retraced portions of the curve more than once. Do not,

however, get too locked into the idea that this will always happen. Many, if not most parametric

curves will only trace out once. The first one we looked at is a good example of this. That

parametric curve will never repeat any portion of itself.

There is one final topic to be discussed in this section before moving on. So far we’ve started

with parametric equations and eliminated the parameter to determine the parametric curve.

However, there are times in which we want to go the other way. Given a function or equation we

might want to write down a set of parametric equations for it. In these cases we say that we

parameterize the function.

If we take Examples 4 and 5 as examples we can do this for ellipses (and hence circles). Given

the ellipse

2

2

2

2

1

x

y

a

b

+

=

a set of parametric equations for it would be,

cos

sin

x

a

t

y

b

t

=

=

This set of parametric equations will trace out the ellipse starting at the point

( )

, 0

a

and will trace

in a counter-clockwise direction and will trace out exactly once in the range

0

2

t

π

≤ ≤

. This is

a fairly important set of parametric equations as it used continually in some subjects with dealing

with ellipses and/or circles.

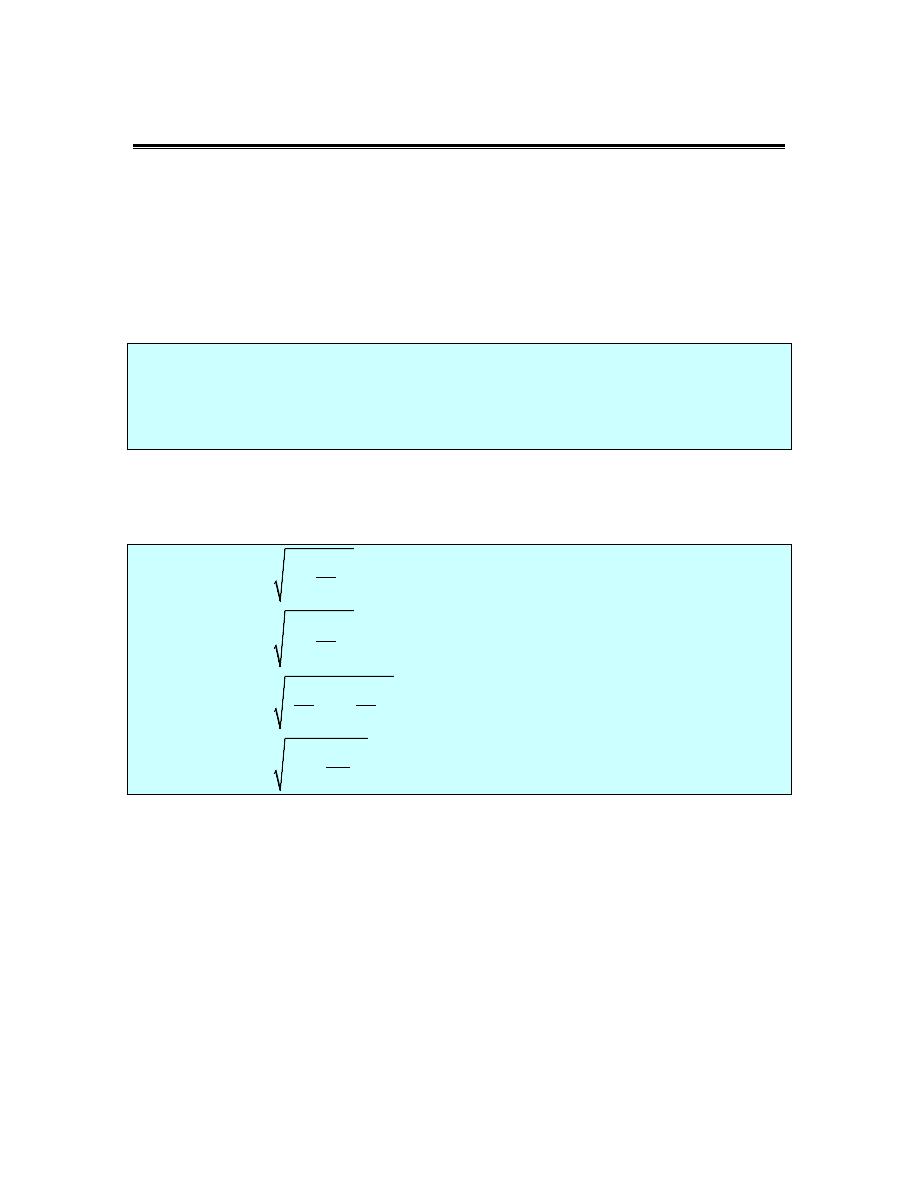

Every curve can be parameterized in more than one way. Any of the following will also

parameterize the same ellipse.

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

( )

cos

sin

sin

cos

cos

sin

x

a

t

y

b

t

x

a

t

y

b

t

x

a

t

y

b

t

ω

ω

ω

ω

ω

ω

=

=

=

=

=

= −

The presence of the

ω

will change the speed that the ellipse rotates as we saw in Example 5.

Note as well that the last two will trace out ellipses with a clockwise direction of motion (you

might want to verify this). Also note that they won’t all start at the same place (if we think of

0

t

=

as the starting point that is).

There are many more parameterizations of an ellipse of course, but you get the idea. It is

important to remember that each parameterization will trace out the curve once with a potentially

different range of t’s. Each parameterization may rotate with different directions of motion and

may start at different points.

You may find that you need a parameterization of an ellipse that starts at a particular place and

has a particular direction of motion and so you now know that with some work you can write

down a set of parametric equations that will give you the behavior that you’re after.

Now, let’s write down a couple of other important parameterizations and all the comments about

direction of motion, starting point, and range of t’s for one trace (if applicable) are still true.

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

24

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

First, because a circle is nothing more than a special case of an ellipse we can use the

parameterization of an ellipse to get the parametric equations for a circle centered at the origin of

radius r as well. One possible way to parameterize a circle is,

cos

sin

x

r

t

y

r

t

=

=

Finally, even though there may not seem to be any reason to, we can also parameterize functions

in the form

( )

y

f x

=

or

( )

x

h y

=

. In these cases we parameterize them in the following way,

( )

( )

x

t

x

h t

y

f t

y

t

=

=

=

=

At this point it may not seem all that useful to do a parameterization of a function like this, but

there are many instances where it will actually be easier, or it may even be required, to work with

the parameterization instead of the function itself. Unfortunately, almost all of these instances

occur in a Calculus III course.

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

25

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Tangents with Parametric Equations

In this section we want to find the tangent lines to the parametric equations given by,

( )

( )

x

f t

y

g t

=

=

To do this let’s first recall how to find the tangent line to

( )

y

F x

=

at

x

a

=

. Here the tangent

line is given by,

( )

(

)

( )

, where

x a

dy

y

F a

m x a

m

F a

dx

=

′

=

+

−

=

=

Now, notice that if we could figure out how to get the derivative

dy

dx

from the parametric

equations we could simply reuse this formula since we will be able to use the parametric

equations to find the x and y coordinates of the point.

So, just for a second let’s suppose that we were able to eliminate the parameter from the

parametric form and write the parametric equations in the form

( )

y

F x

=

. Now, plug the

parametric equations in for x and y. Yes, it seems silly to eliminate the parameter, then

immediately put it back in, but it’s what we need to do in order to get our hands on the derivative.

Doing this gives,

( )

( )

(

)

g t

F f t

=

Now, differentiate with respect to t and notice that we’ll need to use the Chain Rule on the right

hand side.

( )

( )

(

)

( )

g t

F

f t

f

t

′

′

′

=

Let’s do another change in notation. We need to be careful with our derivatives here.

Derivatives of the lower case function are with respect to t while derivatives of upper case

functions are with respect to x. So, to make sure that we keep this straight let’s rewrite things as

follows.

( )

dy

dx

F x

dt

dt

′

=

At this point we should remind ourselves just what we are after. We needed a formula for

dy

dx

or

( )

F x

′

that is in terms of the parametric formulas. Notice however that we can get that from the

above equation.

, provided

0

dy

dy

dx

dt

dx

dx

dt

dt

=

≠

Notice as well that this will be a function of t and not x.

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

26

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

As an aside, notice that we could also get the following formula with a similar derivation if we

needed to,

Derivative for Parametric E quations

, provided

0

dx

dx

dy

dt

dy

dy

dt

dt

=

≠

Why would we want to do this? Well, recall that in the

arc length

section of the Applications of

Integral section we actually needed this derivative on occasion.

So, let’s find a tangent line.

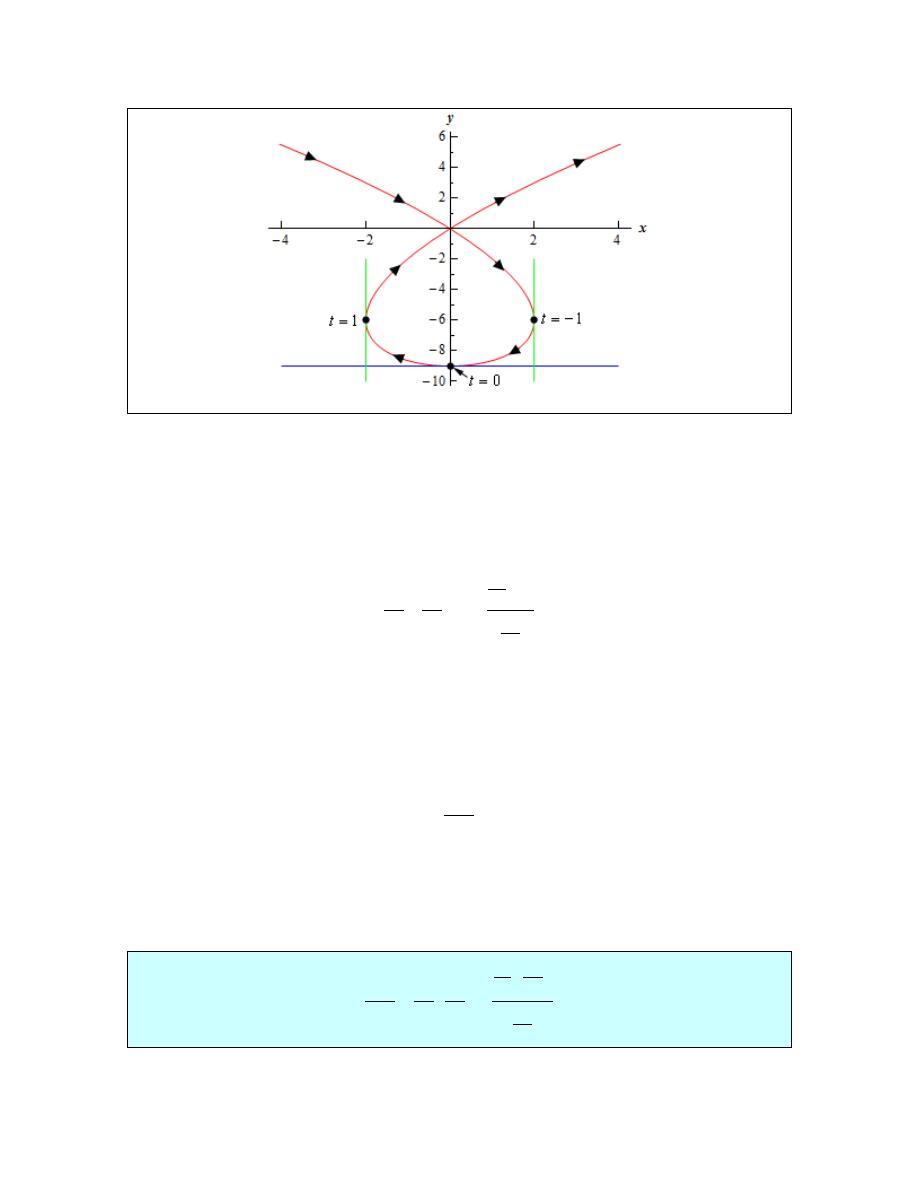

Example 1

Find the tangent line(s) to the parametric curve given by

5

3

2

4

x

t

t

y

t

= −

=

at (0,4).

Solution

Note that there is apparently the potential for more than one tangent line here! We will look into

this more after we’re done with the example.

The first thing that we should do is find the derivative so we can get the slope of the tangent line.

4

2

3

2

2

5

12

5

12

dy

dy

t

dt

dx

dx

t

t

t

t

dt

=

=

=

−

−

At this point we’ve got a small problem. The derivative is in terms of t and all we’ve got is an x-y

coordinate pair. The next step then is to determine the value(s) of t which will give this point.

We find these by plugging the x and y values into the parametric equations and solving for t.

(

)

5

3

3

2

2

0

4

4

0, 2

4

2

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

= −

=

−

⇒

= ±

=

⇒

= ±

Any value of t which appears in both lists will give the point. So, since there are two values of t

that give the point we will in fact get two tangent lines. That’s definitely not something that

happened back in Calculus I and we’re going to need to look into this a little more. However,

before we do that let’s actually get the tangent lines.

t = –2

Since we already know the x and y-coordinates of the point all that we need to do is find the slope

of the tangent line.

2

1

8

t

dy

m

dx

=−

=

= −

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

27

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

The tangent line (at t = –2) is then,

1

4

8

y

x

= −

t = 2

Again, all we need is the slope.

2

1

8

t

dy

m

dx

=

=

=

The tangent line (at t = 2) is then,

1

4

8

y

x

= +

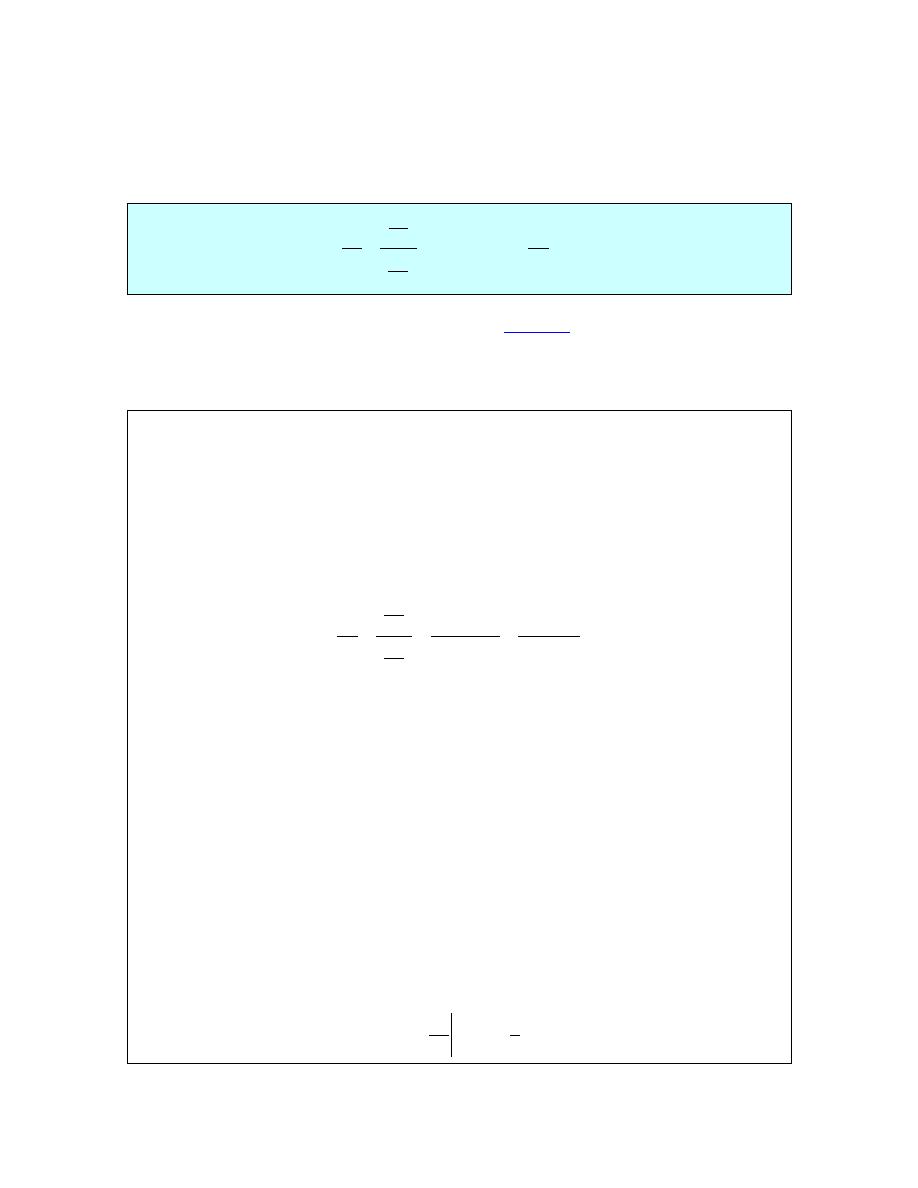

Now, let’s take a look at just how we could possibly get two tangents lines at a point. This was

definitely not possible back in Calculus I where we first ran across tangent lines.

A quick graph of the parametric curve will explain what is going on here.

So, the parametric curve crosses itself! That explains how there can be more than one tangent

line. There is one tangent line for each instance that the curve goes through the point.

The next topic that we need to discuss in this section is that of horizontal and vertical tangents.

We can easily identify where these will occur (or at least the t’s that will give them) by looking at

the derivative formula.

dy

dy

dt

dx

dx

dt

=

Horizontal tangents will occur where the derivative is zero and that means that we’ll get

horizontal tangent at values of t for which we have,

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

28

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Horizontal Tangent for Parametric Equations

0, provided

0

dy

dx

dt

dt

=

≠

Vertical tangents will occur where the derivative is not defined and so we’ll get vertical tangents

at values of t for which we have,

Vertical Tangent for Parametric Equations

0, provided

0

dx

dy

dt

dt

=

≠

Let’s take a quick look at an example of this.

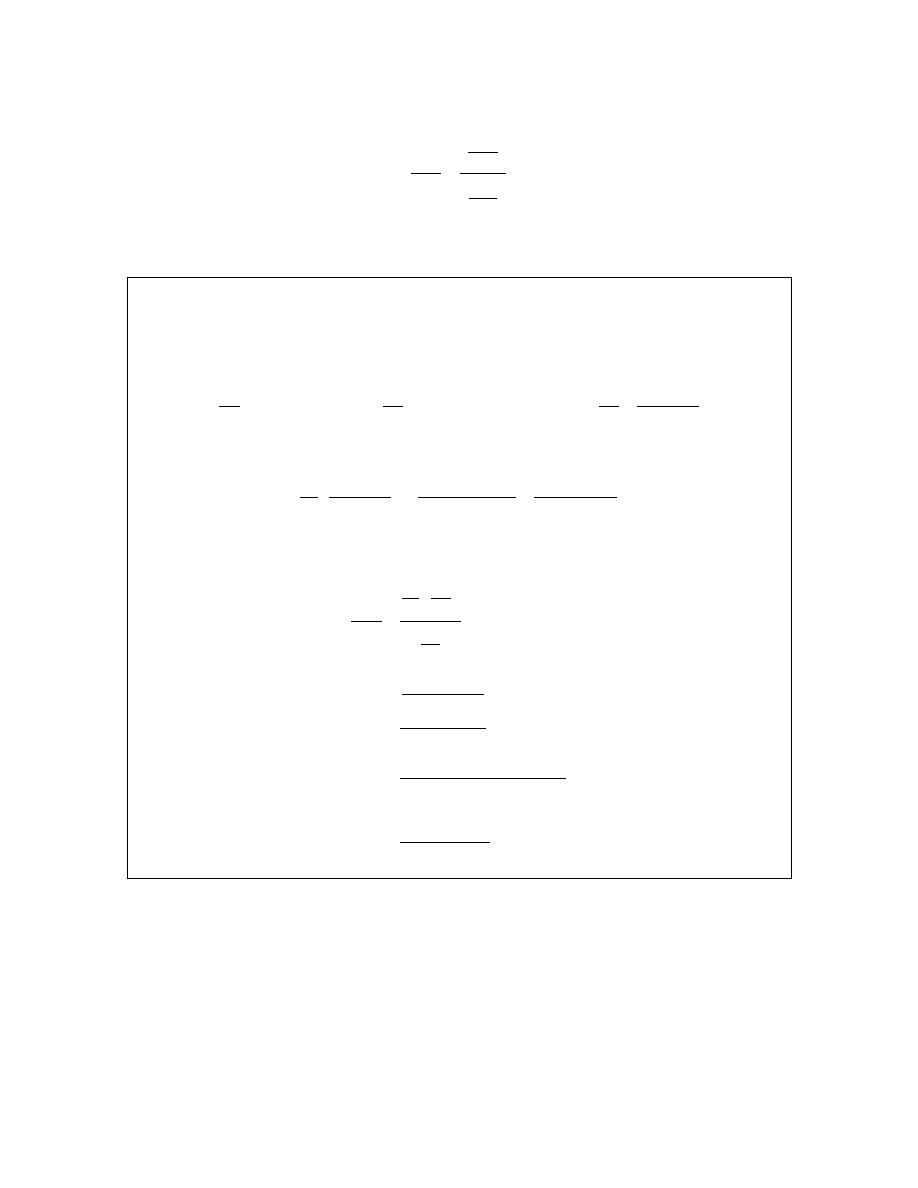

Example 2

Determine the x-y coordinates of the points where the following parametric

equations will have horizontal or vertical tangents.

3

2

3

3

9

x

t

t

y

t

= −

=

−

Solution

We’ll first need the derivatives of the parametric equations.

(

)

2

2

3

3

3

1

6

dx

dy

t

t

t

dt

dt

=

− =

−

=

Horizontal Tangents

We’ll have horizontal tangents where,

6

0

0

t

t

=

⇒

=

Now, this is the value of t which gives the horizontal tangents and we were asked to find the x-y

coordinates of the point. To get these we just need to plug t into the parametric equations.

Therefore, the only horizontal tangent will occur at the point (0,-9).

Vertical Tangents

In this case we need to solve,

(

)

2

3

1

0

1

t

t

− =

⇒

= ±

The two vertical tangents will occur at the points (2,-6) and (-2,-6).

For the sake of completeness and at least partial verification here is the sketch of the parametric

curve.

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

29

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

The final topic that we need to discuss in this section really isn’t related to tangent lines, but does

fit in nicely with the derivation of the derivative that we needed to get the slope of the tangent

line.

Before moving into the new topic let’s first remind ourselves of the formula for the first

derivative and in the process rewrite it slightly.

( )

( )

d

y

dy

d

dt

y

dx

dx

dx

dt

=

=

Written in this way we can see that the formula actually tells us how to differentiate a function y

(as a function of t) with respect to x (when x is also a function of t) when we are using parametric

equations.

Now let’s move onto the final topic of this section. We would also like to know how to get the

second derivative of y with respect to x.

2

2

d y

dx

Getting a formula for this is fairly simple if we remember the rewritten formula for the first

derivative above.

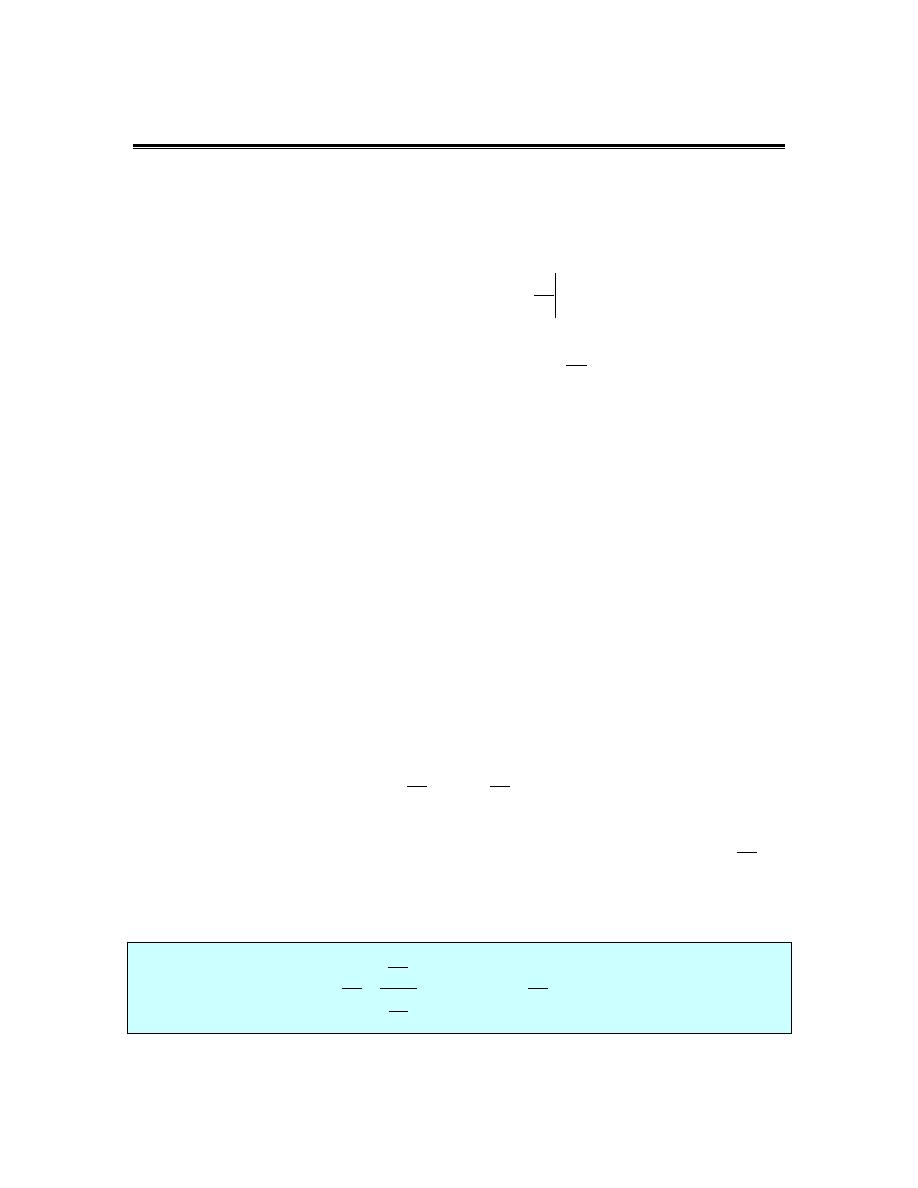

Second Derivative for Parametric Equations

2

2

d

dy

d y

d

dy

dt dx

dx

dx

dx dx

dt

=

=

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

30

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Note that,

2

2

2

2

2

2

d y

d y

dt

d x

dx

dt

≠

Let’s work a quick example.

Example 3

Find the second derivative for the following set of parametric equations.

5

3

2

4

x

t

t

y

t

= −

=

Solution

This is the set of parametric equations that we used in the first example and so we already have

the following computations completed.

4

2

3

2

2

5

12

5

12

dy

dx

dy

t

t

t

dt

dt

dx

t

t

=

=

−

=

−

We will first need the following,

(

)

(

)

(

)

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

2 15

12

2

24 30

5

12

5

12

5

12

t

d

t

dt

t

t

t

t

t

t

−

−

−

=

=

−

−

−

The second derivative is then,

(

)

(

)(

)

(

)

2

2

2

2

3

4

2

2

2

4

2

3

2

3

3

24 30

5

12

5

12

24 30

5

12

5

12

24 30

5

12

d

dy

d y

dt dx

dx

dx

dt

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

=

−

−

=

−

−

=

−

−

−

=

−

So, why would we want the second derivative? Well, recall from your Calculus I class that with

the second derivative we can determine where a curve is concave up and concave down. We

could do the same thing with parametric equations if we wanted to.

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

31

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

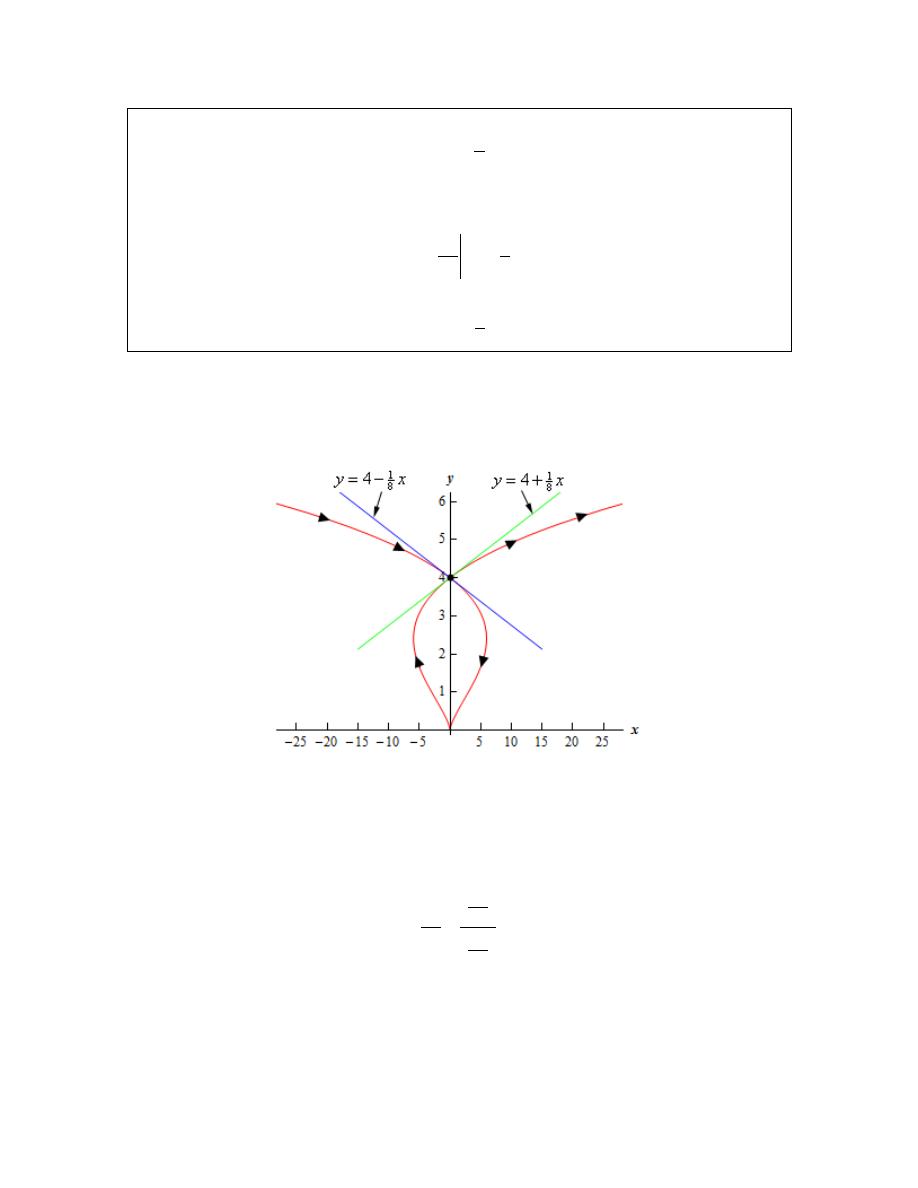

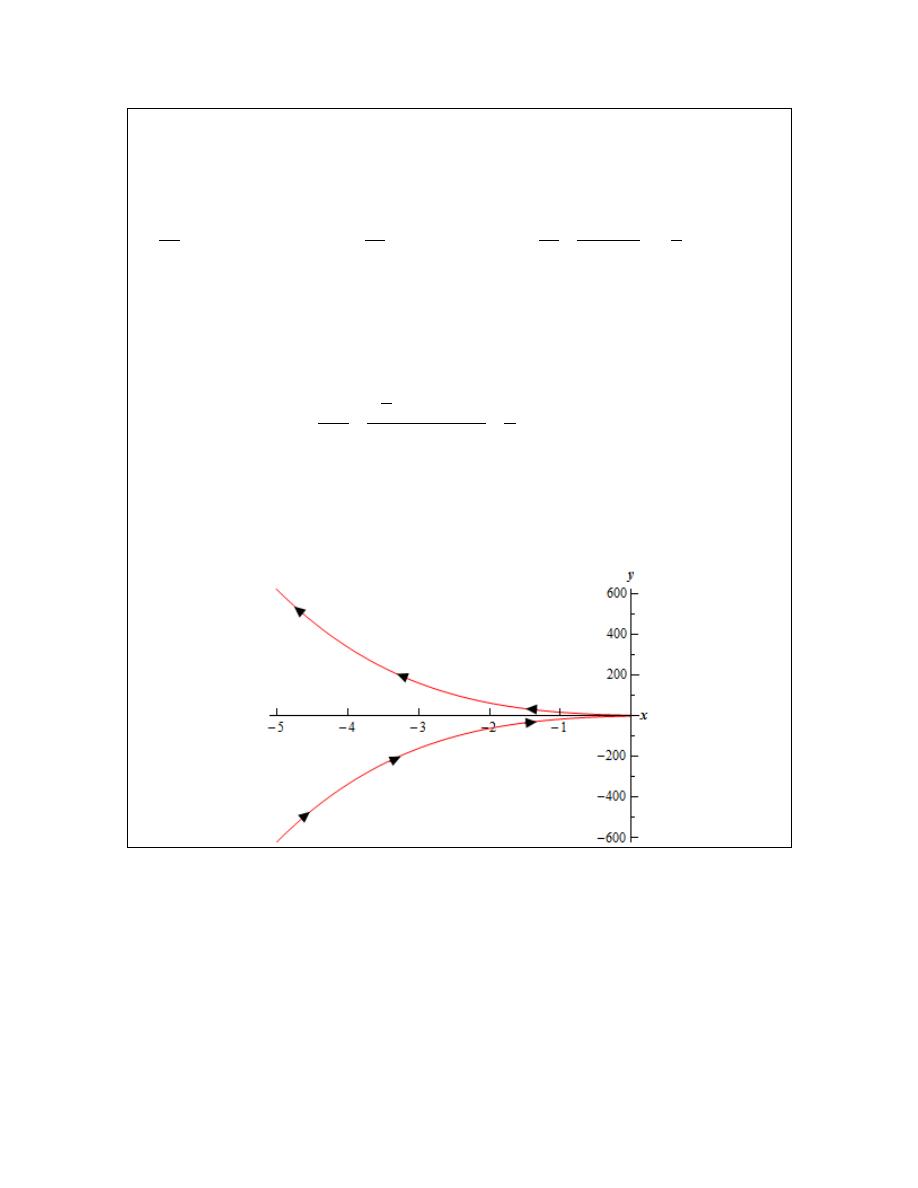

Example 4

Determine the values of t for which the parametric curve given by the following set

of parametric equations is concave up and concave down.

2

7

5

1

x

t

y

t

t

= −

= +

Solution

To compute the second derivative we’ll first need the following.

(

)

6

4

6

4

5

3

7

5

1

7

5

2

7

5

2

2

dy

dx

dy

t

t

t

t

t

t

t

dt

dt

dx

t

+

=

+

= −

=

= −

+

−

Note that we can also use the first derivative above to get some information about the

increasing/decreasing nature of the curve as well. In this case it looks like the parametric curve

will be increasing if

0

t

<

and decreasing if

0

t

>

.

Now let’s move on to the second derivative.

(

)

(

)

4

2

2

3

2

1

35

15

1

2

35

15

2

4

t

t

d y

t

t

dx

t

−

+

=

=

+

−

It’s clear, hopefully, that the second derivative will only be zero at

0

t

=

. Using this we can see

that the second derivative will be negative if

0

t

<

and positive if

0

t

>

. So the parametric curve

will be concave down for

0

t

<

and concave up for

0

t

>

.

Here is a sketch of the curve for completeness sake.

Calculus II

© 2007 Paul Dawkins

32

http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/terms.aspx

Area with Parametric Equations

In this section we will find a formula for determining the area under a parametric curve given by

the parametric equations,

( )

( )

x

f t

y

g t

=

=

We will also need to further add in the assumption that the curve is traced out exactly once as t

increases from

α

to

β

.

We will do this in much the same way that we found the first derivative in the previous section.

We will first recall how to find the area under

( )

y

F x

=

on

a

x

b

≤ ≤

.

( )

b

a

A

F x dx

=

∫

We will now think of the parametric equation

( )

x

f t

=